Manos and metates were fundamentally important tools to all ancient Maya households as key processing equipment for their most important staple crop—corn—as well as other plants, seeds, and tubers. Because of this, every ancient Maya household needed them. Across the Maya Lowlands, manos and metates were made from locally available sources of coarse stone such as basalt, sandstone, slate, quartzite, rhyolite, and granite. In northern and central Belize, by far the most abundantly used source for manos and metates was the Mountain Pine Ridge granite. Recent investigations in the periphery of the ancient Maya site of Pacbitun in Belize have produced evidence for the large-scale production of manos and metates using those Mountain Pine Ridge sources, which are just 8 km away (Figure 1). In this article we review the results of our efforts to explore granite ground stone tool production on Pacbitun’s western periphery and ultimately argue that some social segments living at Pacbitun used granite tool production to negotiate the city’s place on an increasingly dynamic Late Classic period (a.d. 600–800) landscape.

Figure 1. Location of Pacbitun in the Belize River Valley. Redrawn by Sheldon Skaggs and Nicaela Cartagena October 2018.

Pacbitun in the Belize river valley

Pacbitun is a medium-sized Maya center located on a limestone outcrop above the Belize River Valley of west-central Belize (Figure 2, Powis et al. Reference Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti (editors)2020). The site was continuously occupied for at least 1,800 years from the Middle Preclassic (900 b.c.) to Terminal Late Classic (a.d. 900) periods. During that time, 40 masonry structures, an E-Group, and a 16.5 m tall temple pyramid were built around five major plazas. Since 2008 investigations have been conducted by the Pacbitun Regional Archaeological Project (PRAP) under the direction of Terry Powis of Kennesaw State University.

Figure 2. Plan map of Pacbitun’s core. Redrawn from Healy Reference Healy1990 by Sheldon Skaggs and Nicaela Cartagena.

Producing manos and metates

Ethnographic and archaeological studies of mano and metate production provide a context for understanding grinding-tool production at Pacbitun. Ethnographic studies (Hayden Reference Hayden and Hayden1987; also Cook Reference Cook1982; Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Searcy Reference Searcy2011; and Scholes and Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1968) show that tools are made close to the source, and made either to serve nearby markets or for individual household consumption. Archaeological studies suggest general similarities in grinding-tool production deeper into the past. In the Bladen region southeast of the Maya Mountains, Abramiuk and Meurer (Reference Abramiuk and Meurer2006) concluded that people of the Late Classic/Terminal Classic periods in the Toledo District of Belize used local sources, exchanged tools with other communities in the region, but also introduced some into the wider Maya Lowlands. Similarly, Tibbits (Reference Tibbits, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) found that Mountain Pine Ridge granite was widely used throughout central and northern Belize but also made its way further afield into the Maya Lowlands.

Fewer studies have focused on the scale and organization of grinding-tool production. Biskowski’s (Reference Biskowski2017) study of the distribution of mano and metate fragments across the great city of Teotihuacan suggests that grinding tools were likely produced by specialists living in specific neighborhoods or specialized settings. However, outside of very urbanized settings, ethnographic and archaeological studies generally support the idea that most manos and metates were produced in relatively small numbers by individual producers likely specializing part-time. This may be because manos and metates have long use lives, up to 30 years if used for food processing (Hayden Reference Hayden and Hayden1987:15; Hayden and Cannon Reference Hayden and Cannon1984:70), meaning individual households only needed to replace grinding tools every few decades.

Given the scale at which we see granite tool production at Pacbitun, the organization of production is an important issue to explore. We offer our ideas here but acknowledge more work needs to be done to explore this issue fully. On the periphery of the Maya Mountains in Belize, we hypothesize that people living in smaller communities were likely independent specialists as described by Brumfiel and Earle (Reference Brumfiel, Earle, Brumfiel and Earle1987) and Costin (Reference Costin1991). These producers worked part-time for an unspecified or unrestricted demand, often in dispersed settings. At Teotihuacan at least some ground stone crafters were likely what Brumfiel and Earle (Reference Brumfiel, Earle, Brumfiel and Earle1987) called attached specialists, meaning they worked for a patron or governmental organization within the confines of a household or workshop and were provided the means of production. We follow Costin (Reference Costin1991) and Arnold and Munns (Reference Arnold and Munns1994) in suspecting that not all crafters who were expected to produce a quota for a patron worked in settings attached to an elite household or the government. They instead worked in a variety of different physical and social settings. As we will discuss further, the data we currently have from the periphery of Pacbitun suggest granite tool production took place at ad hoc production locales adjacent to domestic residences within a defined community.

Producing manos and metates at Pacbitun

The possibility that large-scale granite tool production took place at Pacbitun was first revealed through excavations at a small mound measuring 2 m tall and covering an area of 5 by 7 m located on a hillside located about 650 m northwest of the site core (Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020; Ward Reference Ward2013). Because this was the first feature discovered with evidence of granite tool working, we have designated it as Granite Production Mound 1 or GPM 1. Excavations at GPM 1 from 2012 to 2015 revealed a core comprised mainly of granite sands interspersed with some flaking debris. Around the periphery of the mound excavators encountered a concentration of larger flaking debris, chert cobbles, and failed granite tools (see Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020:Figures 14.6, 14.7, and 14.9). As Skaggs et al. (Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) observe, this matches favorably the by-products of granite tool making as described ethnographically. Those descriptions outline a three-stage process (see Cook Reference Cook1982; Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Searcy Reference Searcy2011). The first stage consists of roughing out granite blocks, the second involves forming blanks through percussion flaking, and the final stage consists of abrading to create the final shape. In GPM 1, the thick layer of granite sand was produced by the final stage of tool production, while the granite flakes were the result of shaping through percussion flaking using the chert cobbles as hammerstones.

Additional testing in the immediate vicinity of GPM 1 revealed at least two other small mounds that were similar in composition. In 2018, PRAP staff and crew conducted a pedestrian survey in an area 500 m northwest of GPM 1, identifying another cluster of production-debris mounds. Subsequent examination of existing LiDAR data from Pacbitun’s western periphery suggests similar debris mounds may be distributed over a much larger area, hinting at granite tool production on a massive scale. To more fully explore these tool-making activities, we conducted additional survey and testing to determine the overall extent of the granite working, begin to understand the production process represented by granite debris mounds, and explore the social context of granite tool production from household to polity.

Extent of granite working at Pacbitun

The original work focusing on granite production mounds from 2012 to 2018 demonstrated that the heart of the suspected granite-producing community was centered in an area to the northwest of Pacbitun’s core (Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020; Ward Reference Ward2013). To begin to understand the overall extent of Pacbitun’s granite working, we conducted a pedestrian survey consisting of 200 m wide transects oriented at the cardinal directions starting at the center of known granite working (Figure 3). The granite debris mounds and their scatter of associated tools and debitage are substantial enough to be visible without systematic testing, so the survey consisted of full-coverage walk-over inspection of all areas not covered by dense vegetation (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Terry G.2023). This effort resulted in the identification of 22 granite debris mounds in an area approximately 1 km2 in extent some 500 m northwest of Pacbitun’s epicenter (Figure 4). As will become important later, we do not see evidence of a similar scale of granite tool production anywhere else at Pacbitun or on its peripheries.

Figure 3. Survey transects. Green circles are previously confirmed granite debris mounds (GPM = Granite Production Mound) and blue squares are three-mound groups tested in 2012–2021. Pabitun’s site core is located in the bottom right.

Figure 4. Areas surveyed in 2022 showing granite debris mounds.

The production process

The original excavations at GPM 1 provide insight into the granite tool production process represented by at least one mound on Pacbitun’s periphery. That mound is an accumulation of granite sands from final tool shaping, ringed by flaking debris and tools representing intermediate tool shaping. Extrapolating from the weight of granite sand and debitage encountered in their excavations, Skaggs et al. (Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) estimate as many as 1,285 metates and 2,600 manos were made during the life of GPM 1. In order to further explore the activities represented by these granite debris mounds, PRAP staff and crews conducted investigations at three additional granite debris mounds (Figures 3 and 5) near the center of the suspected granite tool working area in the summer of 2021 (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Powis2022).

Figure 5. Plan maps of GPM 5 (a), GPM 6 (b), and GPM 7 (c). GPM = granite production mound.

Based on the original testing of GPM 1, we knew that Pacbitun’s granite debris mounds were comprised of accumulations of flakes and granite sand from making manos and metates. However, it was unclear whether these represented ad hoc production surfaces or intentionally created working areas. The more intensive testing done in 2021 produced evidence to support the latter. This is most convincingly demonstrated by the presence of short walls recorded just off the downslope side of the summits of two debris mounds (Figures 6 and 7, see also King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Terry G.2023). Each was initiated using a single course of very large, unworked pieces of limestone. As tool-making debris accumulated, smaller limestone fragments, spent chert hammerstones, and failed mano fragments were piled on top and on both sides to increase their height.

Figure 6. South profile of Unit 2, GPM 7 (top); Photo of rock wall facing east at base of Level 2, Unit 2, GPM 7 (Bottom, courtesy of Adam KIng. GPM = granite production mound.

Figure 7. North profile of Unit 1, GPM 6 (top); photo of rock wall at base of Level 3, Unit 1, GPM 6 (bottom, courtesy of Adam King). GPM = granite production mound.

The presence of the walls, their apparent growth, and the accumulation of fill and granite debris outside of them all suggest that these mounds were used over a period of time, possibly used seasonally for years. This is supported most clearly by the excavations on each summit where lenses of granite sand or even compact granite sand surfaces were recorded, often separated by general accumulations of granite sand and other soils (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Terry G.2023).

These excavations, when combined with the results of previous work at other granite debris mounds on Pacbitun’s periphery, reveal a general pattern to their structure and use. It appears some, maybe not all, were positioned on flat surfaces created by existing agricultural terraces. Those surfaces were likely cleared and possibly leveled, and a retaining wall was built at the edge of the terrace slope. On the summits, relatively low frequencies of granite flakes were recovered while the fills were comprised mainly of granite sand produced from the final production stages. This suggests that the debris created by the initial reduction of the granite blanks was cleared from the working area on the summit. In the initial debris mound tested, Skaggs et al. (Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) found that the larger flakes were deposited in a ring around the base of the mound, as if the summit was kept clear of those materials. Once created, these platforms were repeatedly used and, as granite sand built up on the summit, the walls were raised.

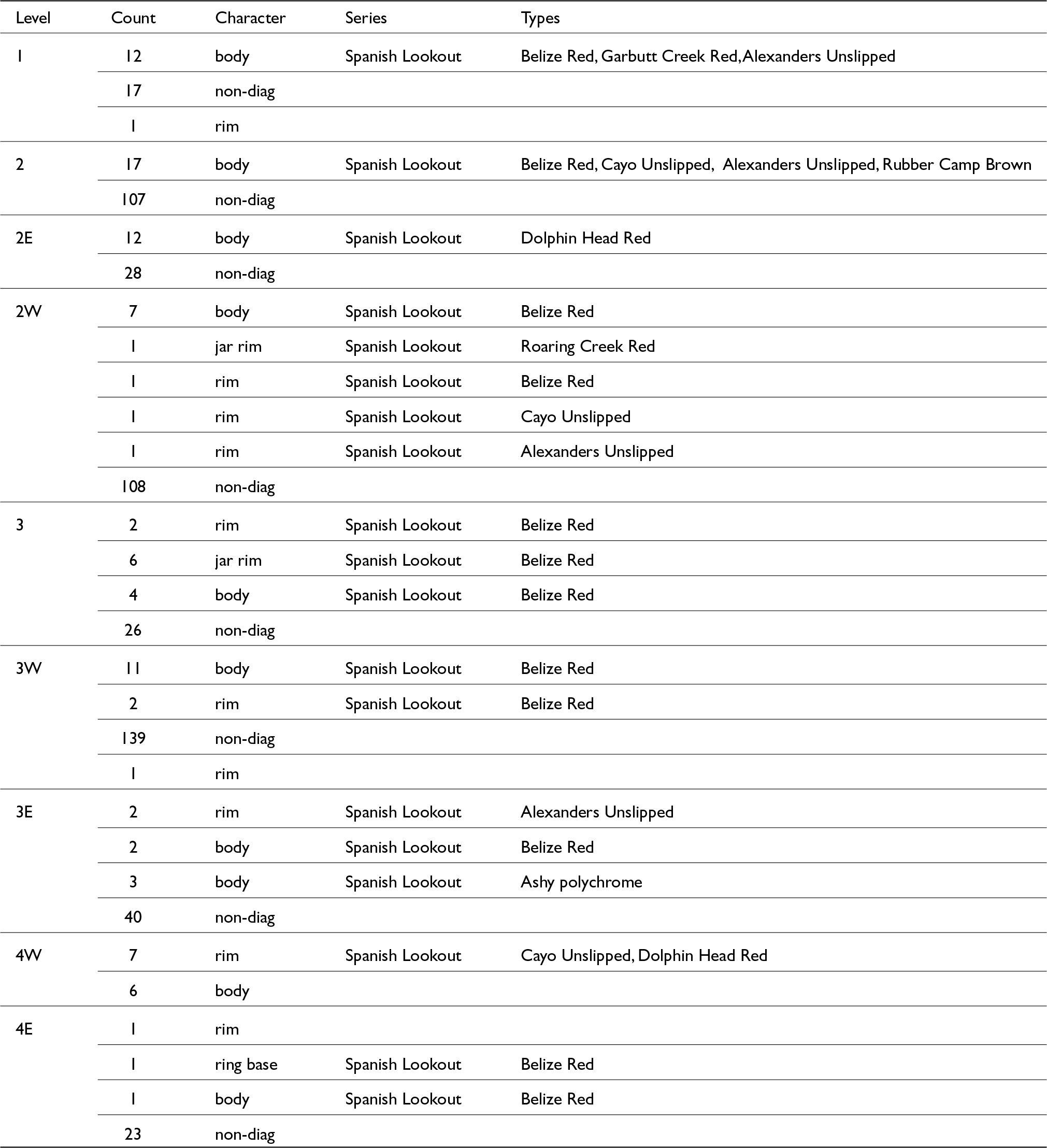

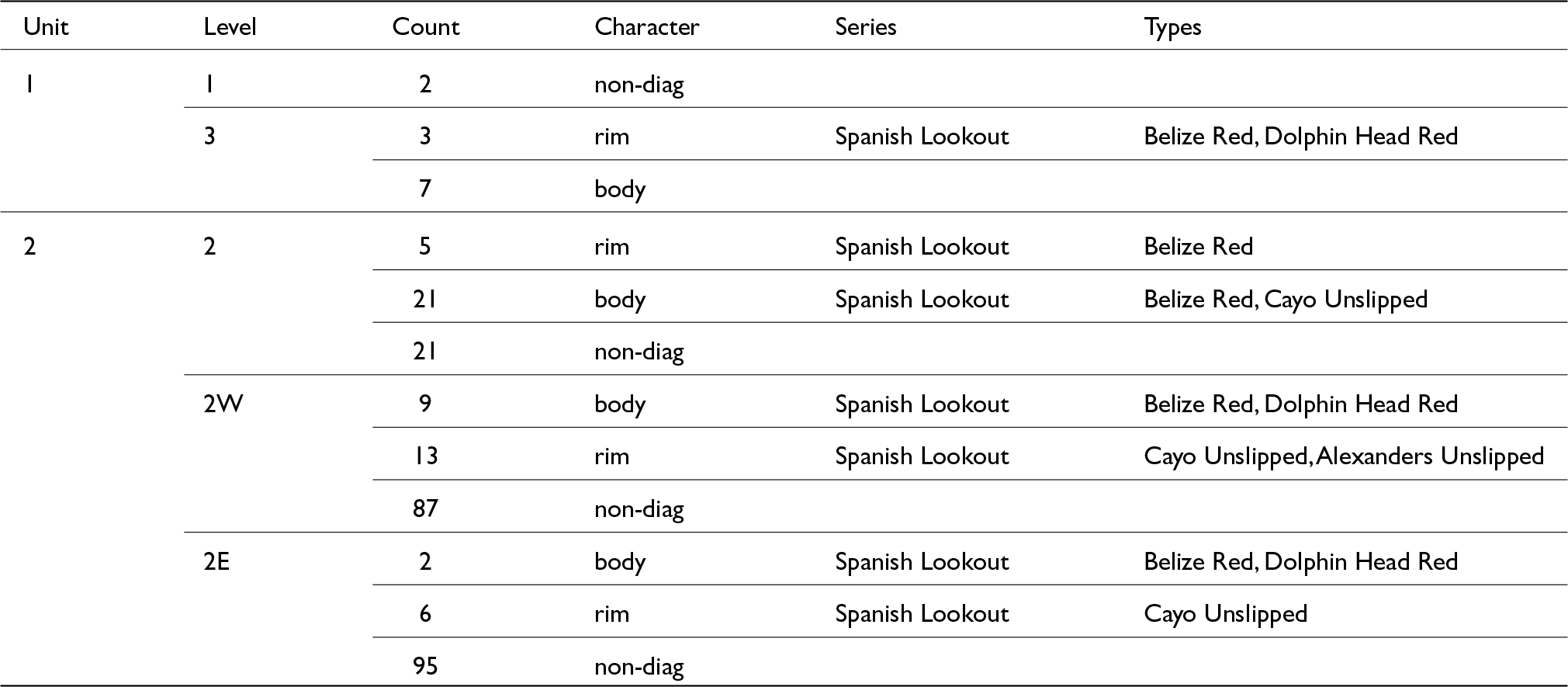

Dating the granite debris mounds on Pacbitun’s periphery has been complicated by a lack of carbonized material; however, in the summer of 2021 two samples were collected and dated using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) by the Center for Applied Isotope Studies (CAIS) at the University of Georgia in Athens. One sample (UGAMS #68587) was obtained from charred material found in Level 6 of Unit 1 in GPM 1 and is AMS dated to cal a.d. 654–773 (95.4 percent [2 sigma]; mean cal a.d. 699). The other sample (UGAMS #68588) was derived from charred material found in Level 3E of Unit 1 in GPM 6 and is AMS dated to cal a.d. 668–821 (95.4 percent [2 sigma]; mean cal a.d. 725). Both AMS dates fit very well with the ceramic assemblages coming from GPM 1 and GPM 6. At these two mounds, as well as at all others tested, the sherd material is predominantly Late Classic in date (see Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020 and Tables 1–3). Diagnostic sherds belong to the Alexanders, Belize, Cayo, Dolphin Head, and Garbutt Creek ceramic groups of the Spanish Lookout Phase. Taken together, a clear pattern emerges. Ceramic and AMS dating strongly indicate that the production of manos and metates in the western periphery of Pacbitun was occurring during the eighth century, at the height of the site’s political and economic prosperity.

Table 1. Ceramics recovered in GPM 5 Test Unit 1

Note: GPM = granite production mound; non-diag = non-diagnostic.

Table 2. Ceramics recovered from GPM 6 Unit 1

Note: GPM = granite production mound; non-diag = non-diagnostic.

Table 3. Ceramics recovered from GPM 7 Test Units 1 and 2

Note: GPM = granite production mound; non-diag = non-diagnostic.

Exploring the social context of granite working

Given the apparently large numbers of granite tools made over a relatively short period of time (200 years at most), we have hypothesized that granite working was not performed by independent specialists producing only for Pacbitun households. Instead, we suspect granite tool working generally fits what Brumfiel and Earle (Reference Brumfiel, Earle, Brumfiel and Earle1987) call attached specialization where individual crafters produce for a patron or the government, are required to produce a quota, and in return receive access to the means of production (land and tools). Production is not concentrated in an elite household or workshop at Pacbitun’s core but is instead spread out over an area of about 1 km2. As a result, we hypothesize that Pacbitun’s granite working likely fits what Costin (Reference Costin1991) calls dispersed corvee specialization, which is a kind of attached specialization where production is not confined to a formal workshop or elite household.

If this is the case, then we expect production to have taken place at the household level, but its organization and the mobilization of finished tools to have taken place at higher social levels, whether the government or a wealthy landowner on Pacbitun’s periphery. To evaluate this idea, we tested isolated residential mounds near debris mounds and also small multiple-mound groups within the presumed production community to see if they contained evidence of connections to granite tool production.

Isolated house mound testing

Each of the debris mounds tested in 2021 was located on an agricultural terrace with an isolated house mound within 30 to 35 m. These were easily distinguishable from the granite debris mounds by the presence of worked and unworked limestone used in platform and wall construction. In each case, we observed some granite flaking debris along with mano blanks in various stages of finishing on the summits and lower flanks of each mound.

To explore the connection between these households and the nearby granite debris mounds, Skaggs and crew (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Powis2022) tested a house mound located between two debris mounds tested in 2021 (GPM 5 and GPM 6 in Figure 5). Almost 30 years ago, Sunahara (Reference Sunahara1995) excavated a 1 m test into its flank, encountering Late Classic diagnostic pottery. Skaggs and colleagues excavated 5 m2 on the summit and at the base of the flank of the mound, recording a single-phase domestic structure containing a small number of Late Classic pottery diagnostics (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Powis2022). Although granite flaking debris, chert hammerstones, and mano blanks were visible on the surface of the flanks of the structure, crews found little evidence of granite working within it. The presence of these materials and Late Classic diagnostics suggests that this household, and likely those near the other debris mounds tested, were the domiciles of granite tool producers.

Small group testing

In addition to finding connections between granite debris mounds and isolated households, we also wanted to explore the possibility that larger architectural groups also were connected to granite working—our hypothesis being that these larger architectural groupings represented the possible households and facilities of granite-working managers and finished-product mobilizers. Toward that end, during the summer of 2022 season, a PRAP crew tested two three-mound groups (Figure 3) located near debris mounds and associated house mounds (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Terry G.2023). In both groups, the crew excavated a 1 m test unit into the northern or western platform and another 1 m test unit into the plaza, searching for evidence of connections to the production process through storage of raw materials, granite-working tools, and finished products. Crews did not recover granite flaking debris, tools, or granite raw materials suggestive of involvement in granite tool making at either group.

It is important to note that our testing was very limited, with only 2 m2 investigated in each group. As a result, the likelihood of encountering evidence for provisioning tool makers with chert hammerstones or raw materials as well as finished tool storage was limited. In the summer of 2023 King returned to one of these groups (Group 22-R8-1). It had recently been burned in preparation for field planting, creating excellent surface visibility. On that newly exposed surface we found an abundance of evidence demonstrating a connection to granite working in the form of flaking debris, mano blanks in various stages of production, failed manos, and clusters of chert hammerstones. This suggests that at least some of the smaller multiple-mound groups were occupied by people involved in granite working. However, further work is needed at these groups and other larger groups within the proposed production community to fully understand their place in the organization of granite tool making.

A summary of the Pacbitun granite tool production project

To date, PRAP staff and crews have identified 22 granite debris mounds in an area approximately 1 km2 in extent some 500 m northwest of Pacbitun’s epicenter. All confirmed debris mounds share the same stratigraphic characteristics, which were identified previously (Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020), and are consistent with ethnographic descriptions of the remains of granite tool production (see Cook Reference Cook1982; Hayden Reference Hayden and Hayden1987; Jaime-Riveron Reference Jaime-Riveron2016; Searcy Reference Searcy2011). Each debris mound consisted of up to 75 cm of granite sand, produced during the final shaping stages of tool production, along with an assemblage of small- to medium-sized (2–5 cm in range) granite flakes. Around the periphery, tool makers deposited larger flaking debris, broken mano blanks and chert hammerstones and debitage (see Skaggs et al. Reference Skaggs, Micheletti, Lawrence, Cartagena, Terry G., Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020:167–171 for descriptions and Figures 14.6 and 14.10 for photos).

Two additional mounds tested were located on agricultural terraces and had small retaining walls constructed on the downslope side (King et al. Reference King, Skaggs and Powis2022). These were constructed and increased in height as tool production continued and granite sand and flaking debris piled up. A comparison of the artifact assemblages recovered in mound-summit test units with those from flank excavations reveals that large flakes (˃5 cm in size) from early stages of tool shaping were cleared from the mound summits and deposited over the flank (SI Tables 1–3). This suggests these debris mounds were prepared and maintained platforms representing multiple episodes of tool production activities, possibly over several seasons.

Despite the great abundance of granite sand and debitage, datable materials such as ceramics were comparatively scarce. All of the mounds tested produced pottery assemblages consistent with only a Late Classic period occupation. This fits well with Sunahara’s (Reference Sunahara1995) observation, based on survey and testing in Pacbitun’s periphery, that most of the house mounds and small groups were occupied primarily during the Late Classic period.

The results generated so far lead us to argue that intensive granite tool production took place exclusively during the Late Classic period in a single community located on the northwestern periphery of Pacbitun. The interspersing of isolated houses among debris mounds suggests that production may have been conducted at the household level. If each granite debris mound represents the creation of as many as several thousand grinding tools, then it should be clear that production was at a scale that transcended the needs of individual households within the Pacbitun polity. This suggests to us that production was not simply for household use but was mobilized for wider distribution. Under these circumstances, we expect granite working and finished tool distribution were managed at multiple levels above the household. While there is still more to learn about production at this level, we have recovered some evidence indicating that larger architectural groupings also were involved in some way with granite working. We assume that involvement included facilitating individual household production and the mobilization of finished tools to serve trade networks reaching far beyond Pacbitun.

Granite tool working in the history of Pacbitun

The Late Classic period is an interesting time on the wider landscape of the ancient Maya and at Pacbitun. During the Early Classic period (a.d. 300–600), Pacbitun was a provincial polity in the political sphere of the city of Tikal. During the Early Classic period, competition between Tikal and its rivals increased, eventually leading to Tikal’s defeat near the end of the period. No longer under the control of Tikal, by the Late Classic period Pacbitun became more autonomous and more aligned with local powerful centers in the Belize River Valley. Like other centers in the valley, Pacbitun experienced increased prosperity as its inhabitants reoriented and expanded both ritual and public architecture (Micheletti et al. Reference Micheletti, Helmke, Healy, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020).

It is within this context that a segment of Pacbitun’s population undertook the large-scale production of granite manos and metates—something that every Maya household needed. In doing so, people at Pacbitun, whether it be leading families on the periphery or its ruling line, chose to take advantage of their proximity to Mountain Pine Ridge granite sources. The chemical sourcing work by Tibbits (Reference Tibbits, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) shows that this was the primary source of granite used to make grinding tools across much of northern Belize and into other parts of the Maya Lowlands. While Tibbits (Reference Tibbits, Powis, Skaggs and Micheletti2020) was not able to date all of the tools she sourced, it is worth considering that Pacbitun was at least in part responsible for the wide distribution of Mountain Pine Ridge grinding tools.

We posit that people at Pacbitun took up the large-scale production of grinding tools out of some necessity or opportunity created by the politically dynamic landscape of the Late Classic period. For us the fact that at least some of the production-debris mounds and associated households were located on agricultural terraces speaks to the significance of the work. At some level, making manos and metates was deemed more important than growing food on those agricultural terraces.

Smaller centers like Pacbitun were forced to make their way in a landscape where the political influence of regional centers waxed and waned amid the political contractions, social restructuring, and population relocation of the Late Classic period. Perhaps leaders at Pacbitun used their proximity to Mountain Pine Ridge granite sources to negotiate favorable relationships with more powerful centers. Alternatively, dominant centers may have exploited Pacbitun’s location and reoriented at least parts of its economy as part of hegemonic relations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536125100771.

Acknowledgements

This project could not have been completed without the generous support of the Alphawood Foundation, the American Philosophical Society’s Franklin Research Grant, the Rust Foundation, and the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology’s R. L. Stephenson Fund. We would also like to thank the Archaeology Institute of Belize for allowing us to conduct archaeological investigations at Pacbitun. Finally, we appreciate the support of landowners Gabino Canto, Samuel Galdemez, Phillip Mai, Charlie Tzib, Danilo Tzib, Ebelio Tzib, and Joe Tzul.