Introduction

There is a significant gender gap in political careers across Western democracies, with women continuing to be systematically under‐represented. This relates not only to women in elected office but also to those working for parties as officials and advisors (Moens, Reference Moens2021; Yong & Hazell, Reference Yong and Hazell2014).Footnote 1 One of the main supply‐side explanations advanced for women's under‐representation is the gender gap in nascent political ambition, with research showing that, by the time they are young adults, women already express less interest in the idea of running for office one day (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2014). In this study, we investigate the degree to which differences in ambition are present among a distinct group of politically engaged women and men: those who participate in the youth wings of political parties.Footnote 2 Although youth wings remain an understudied element of party organizations, they are an important part of the pipeline for elected representatives in Western parliamentary democracies (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Nielsen, Pedersen and Tromborg2020; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Ohmura et al., Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018). As such, they offer a unique perspective on those young adults who may be among tomorrow's political elites. Using an original online survey fielded among almost 2,000 members of three centre‐left and three centre‐right party youth wings in Australia, Italy and Spain, we ask: Does nascent political ambition vary between women and men in youth wings?

Our focus on gender and nascent political ambition builds on the work of Fox and Lawless, who define the latter as ‘the embryonic or potential interest in office seeking that precedes the actual decision to enter a specific political contest’ (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005, p. 643). However, we examine not only the desire to stand as candidates for elected office but also aspirations to pursue non‐electoral political careers, such as working for party organizations and their representatives. These non‐electoral careers allow politically interested people to exert considerable influence on parties’ campaign strategies, decisions and policy development, thus playing a central role in the functioning of parties in contemporary democracies (Karlsen & Saglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017). Since we know that women and men engage in different types of political participation, with women being more involved in non‐electoral forms of activism (Coffé & Bolzendahl, Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010; Marien et al., Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010) and preferring less visible political roles to electoral ones (Bauer & Darkwah, Reference Bauer and Darkwah2020; Kolltveit, Reference Kolltveit2021), we contend it is important to look not just at the electoral arena but also to consider other types of party careers when investigating the gendered nature of political ambition. In addition, we study the interaction of gender and party ideology in shaping nascent political ambition. This is because left‐wing parties may offer better environments for the expression of ambition by women, given they have been more pro‐active than right‐wing ones in establishing gender quotas and tend to have a higher proportion of women among their elected representatives (Caul, Reference Caul1999; Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2006).

Consistent with the many existing studies reporting gender differences in candidate aspirations among senior party members (Davidson‐Schmich, Reference Davidson‐Schmich2008; Kjaer & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019), our survey results show that women in youth wings are less likely than men to want to stand as candidates one day. However, this gender gap narrows considerably – and, in some youth wings, disappears entirely – when we look at the desire to work for the party in the future. By examining both electoral and non‐electoral nascent political ambition, we arrive at a more nuanced view of women's desire to pursue political careers and show that the ambition gender gap applies more to public office than party positions. In short, it is not the case that women are necessarily less interested than men in all types of political careers. Moreover, and contrary to our expectations, we find that women in centre‐right parties are no less ambitious than their counterparts on the centre‐left. We thus caution against the conventional wisdom that left‐wing parties inherently provide better environments for women's political ambitions to flourish than right‐wing ones.

If our theoretical contributions derive from studying both electoral and non‐electoral nascent political ambition, and from our attention to the influence of party ideology on ambition, our empirical contribution stems from the object of our study, namely party youth wings in parliamentary democracies. Research on political ambition has overwhelmingly concentrated on the United States. While this has produced a rich body of knowledge about the gendered nature of political ambition, it is largely based on a system where the pipeline for political careers functions differently to most other Western democracies (Piscopo, Reference Piscopo2019). Notably, in parliamentary democracies, political parties play a far more central role than they do in the United States in the recruitment, training and selection of political candidates and operatives (Hazan & Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Karlsen & Saglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017). In particular, the preparation of future elites is a core mission of party youth wings in many democracies. As Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004, p. 196) observe, youth wings ‘function as a kind of learning school, where the members gradually grow acquainted with political and party life’. Moreover, they offer young people the possibility of taking on leadership positions, working on election campaigns, and developing their skills with a view to one day working for the party and/or standing as candidates. In our study, we are thus focusing on a key entry point of the political career pipeline in Western democracies.

In the next section, we discuss the theoretical background to our study and set out our hypotheses about women's and men's nascent political ambition in youth wings, and the interaction of gender with party ideology in shaping such ambitions. We then introduce our cases and the original online survey we used to test those hypotheses among centre‐left and centre‐right youth wing members in Australia, Italy and Spain. In our results section, we present the findings of our empirical analysis, showing that the gender gap in nascent political ambition is very much present as regards the desire to stand as a candidate, but largely disappears when we look at the aspiration to work for the party. We also observe that women in centre‐left youth wings are no more ambitious than those in centre‐right ones, both in electoral and non‐electoral terms. Finally, in the conclusion, we consider some of the implications of our study both for theories of political ambition and women's participation in politics.

The gender gap in nascent political ambition

Nascent political ambition has been conceptualized as a critical first step on the ladder leading to standing as a candidate and becoming a representative (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005). To date, scholars have investigated nascent political ambition, especially in the United States, by focusing on aspirations for elected positions (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005, Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006). However, there is also a wide range of non‐electoral political careers beyond the representative realm to which people may aspire. With the professionalization of parties over the last half‐century (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988) and the growth in numbers of staffers (Poguntke et al., Reference Poguntke, Scarrow, Webb, Allern, Aylott, Bardi, Costa‐Lobo, Cross, Deschouwer, Enyedi, Fabre, Farrell, Gauja, Kopecký, Koole, Verge, Müller, Pedersen, Rahat, Szczerbiak and van Haute2016), these non‐electoral political roles have become central to the functioning of parties, with Karlsen and Saglie (Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017, p. 1335) referring to those performing them as ‘unelected party politicians’. These can include party officials at various levels, advisors and campaign managers who, among other tasks, contribute to the development of party programmes and campaign strategies (Karlsen & Saglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017, p. 1341). In our study, we therefore analyse nascent political ambition among women and men in party youth wings by looking at both their desire to stand as candidates (electoral ambition) and their aspirations to work for the party in the future (non‐electoral ambition).

The scholarship to date on nascent political ambition has shown that women are less likely than men to want to pursue political careers. As noted above, this research has focused on aspirations for elected offices rather than party positions, and has been largely limited to the US context (e.g. Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005; Crowder‐Meyer, Reference Crowder‐Meyer2020). More recently, however, the electoral ambition gender gap among the public has been observed in other Western democracies. For example, in a survey of over 10,000 British citizens, Allen and Cutts (Reference Allen and Cutts2018, p. 74) find that men are twice as likely as women to say they have considered standing for elected office or are actively seeking a candidature. Echoing these results, in a survey of eligible voters in Canada, Pruysers and Blais (Reference Pruysers and Blais2019, p. 233) discovered that while one‐third of men in their sample had thought about running for public office, fewer than one‐fifth of women had done so.

The literature has pointed to a series of reasons for this gap. In particular, women perceive higher costs than men in pursuing a public political career (Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006; Bauer & Darkwah, Reference Bauer and Darkwah2020), are less likely to receive encouragement to run (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2004), tend to view themselves as less qualified (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2004) and are warier of the competitive context of election campaigns (Kanthak & Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015). Scholars also agree that differences in the way women and men are socialized from a young age – women being traditionally associated with the private realm and men with the public one – are crucial in explaining why women are less interested in pursuing elected office (Dassonneville & McAllister, Reference Dassonneville and McAllister2018; Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022). As a result, the gender gap in electoral ambition already materializes among young people. For example, a survey by Fox and Lawless (Reference Fox and Lawless2014) of nearly 4,000 US high school and college students showed that 35 per cent of women, compared to 48 per cent of men, had considered running for an elected position. Similarly, in their experiment with over 500 university students in Canada, Pruysers and Blais (Reference Pruysers and Blais2017) found that about 71 per cent of women had never thought about running for office compared to around 54 per cent of men.

Researchers have observed similar gender gaps in electoral ambition when they narrow their focus from the general public to party members, who constitute the main group of potential candidates in parliamentary democracies (Hazan & Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010). Drawing upon a survey of over 1,000 rank‐and‐file members of five German parties, Davidson‐Schmich (Reference Davidson‐Schmich2008, p. 17) discovered that while 27 per cent of men said they would accept their party's nomination to run for the federal elections, only 16 per cent of women reported likewise. Similarly, Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen (Reference Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019, p. 312) show that in Denmark – a supposedly more ‘women‐friendly context’ than most other Western countries – women in nine parties across the ideological spectrum were still less likely than men to consider standing, even when encouraged to do so by their party. In other words, not only women in general but also women party members express lower interest in seeking elected office compared to men.

Turning, finally, to gender differences in electoral ambition in youth wings, the only study directly relevant to our research question is that by Kolltveit (Reference Kolltveit2021). Although his focus is different from ours in that he surveys progressive political ambition among youth wing elites in Norway, rather than nascent electoral ambition among the wider youth wing membership, he finds that young men are more interested in occupying specific elected positions.Footnote 3 Based on the research discussed so far, both on the general public and on party members, we therefore hypothesize the following:

H1a: Men in youth wings will be more likely than women to want to stand as candidates in the future.

Our second type of nascent political ambition concerns the desire to pursue non‐electoral careers, working for the party. Webb and Keith (Reference Webb, Keith, Scarrow, Webb and Poguntke2017, p. 40) have rightly described political staff as ‘one of the most under‐researched fields in the study of political parties’, so we have few relevant insights to draw upon in formulating our hypotheses. What we do know is that, just like election candidates, in Europe these workers tend to come from the party grassroots (Karlsen & Saglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017; Moens, Reference Moens2021). Such positions should therefore appeal to youth wing members thinking of a career in politics. Differently from what we expected as regards the desire to stand as candidates, however, we hypothesize that there will be no gender differences in aspirations to pursue these non‐electoral roles. In fact, while women may be less inclined to run for elected office, it does not follow that they will have lower levels of interest in political careers generally. As Coffé and Bolzendahl (Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010) have illustrated, women tend to participate in politics differently, rather than less than men. Although men are more active in electoral forms of participation, women prefer to engage in less visible, non‐electoral types of political activism (Coffé & Bolzendahl, Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010; Marien et al., Reference Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier2010). This distinction holds also when we shift our focus from the public to members of political parties. For instance, in their study of party membership in Britain, Bale et al. (Reference Bale, Webb and Poletti2020) observed that women are more likely than men to get involved in activities that are private in nature.

Bauer and Darkwah (Reference Bauer and Darkwah2020) indicate a few reasons why women may be keener on a political career behind the scenes than in the spotlight. In their study, based on dozens of interviews with members of four parties in Ghana, they find that women would rather seek non‐elected party offices because of the financial costs of running a campaign and the gendered violence they may be subjected to, such as verbal harassment. It is possible that these beliefs are shared not only by members of senior parties but also by members of youth wings. Notably, Kolltveit (Reference Kolltveit2021) shows that, in contrast to his findings regarding elected positions, women leaders in Norwegian youth wings do not display lower levels of progressive ambition than men when asked about their desire to work in specific party organization roles. This evidence suggests that, when it comes to non‐electoral political careers, young women may be at least as ambitious as men. This leads us to our second hypothesis:

H1b: Women in youth wings will be as likely as men to want to work for the party in the future.

We also expect gender to interact with party ideology in fostering or hindering nascent political ambition, both as regards standing as candidates and working for the party. In addition to being more inclined to introduce candidate and intra‐party quotas for women, left‐wing parties elect and employ higher proportions of women than their right‐wing counterparts (Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2006; Yong & Hazell, Reference Yong and Hazell2014; Childs & Kittilson, Reference Childs and Caul Kittilson2016). This is relevant to nascent political ambition, since women in such positions may act as role models, encouraging other women to get involved (Wolbrecht & Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007; Ladam et al., Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018) and enhancing levels of activism among women party members (Ponce et al., Reference Ponce, Scarrow and Achury2020). Moreover, quotas give ambitious women more opportunities to fulfil their political aspirations (Piscopo, Reference Piscopo2019, p. 821). It is therefore plausible that women in centre‐left youth wings will be more ambitious than those in centre‐right ones. In fact, early studies in the United States indicated that while Democratic and Republican men activists were similarly ambitious, Democratic women were more interested in a political career than Republican ones (Sapiro & Farah, Reference Sapiro and Farah1980; Costantini, Reference Costantini1990). Similarly, Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen (Reference Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019, p, 11) find that the share of women members in Danish left‐wing parties aspiring to elected office is consistently higher than in right‐wing ones. We therefore propose the following two hypotheses concerning the interaction of gender and party ideology in shaping both types of political ambition:

H2a: Women in centre‐left youth wings will be more likely than women in centre‐right ones to want to stand as candidates in the future.

H2b: Women in centre‐left youth wings will be more likely than women in centre‐right ones to want to work for the party in the future.

Political party youth wings

In our study, we investigate whether gender differences in nascent political ambition are present among members of party youth wings. Despite the fact that many senior party grassroots members, officials and leaders are politically socialized in youth wings, these sub‐organizations have been largely ignored by scholars. A notable exception is the study conducted by Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009) of youth wing members in six European countries in the mid‐2000s.Footnote 4 As regards political ambition, they found that 26 per cent of youth wing members said they had joined to pursue a career in politics (Bruter & Harrison, Reference Bruter and Harrison2009, p. 32). The levels of political ambition observed by Bolin et al. (Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2022) among members of eight youth wings in Sweden are even higher, with 63 per cent reporting that they had joined because they were interested in working for the party, and 54 per cent indicating they did so because they were interested in running as candidates one day. The prospect of a political career is thus a far more significant driver of the decision to sign up for youth wing members than it is for senior party ones. In fact, across a range of European cases, the percentage of senior party members who report they have joined for career incentives never exceeds 5 per cent (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015; Heidar & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Heidar, Kosiara‐Pedersen, Demker, Heidar and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019). Moreover, whatever their reasons for joining, Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009, p. 221) observed that over half of youth wing members ‘either consider moving on to political leadership or are absolutely certain and positive that they will indeed seek positions of responsibility within their party or seek representative or executive positions through competitive elections’.

These high levels of ambition among youth wing members reflect the career pathways that have long been followed by elected representatives in many parliamentary democracies. For example, Recchi (Reference Recchi1996) showed that youth wings had functioned as an apprenticeship for more than 30 per cent of Italian MPs, while Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004) found that 41 per cent of all city councillors in Flanders had come through the youth wings of their parties. Similarly, Ohmura et al. (Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018, p. 178) documented how more than a quarter of German MPs over five legislatures (1998–2014) had a long pre‐parliamentary career occupying youth wing and party positions. Looking at youth wings thus provides a window on the political class of tomorrow. However, none of the studies to date have considered the differences in nascent political ambition among women and men in youth wings. Given the continuing underrepresentation of women among senior party candidates, representatives and officials (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005; Moens, Reference Moens2021), it is worth examining whether a gender gap in the desire to pursue electoral and non‐electoral careers is already present among this distinct group of politically engaged young people.

Cases

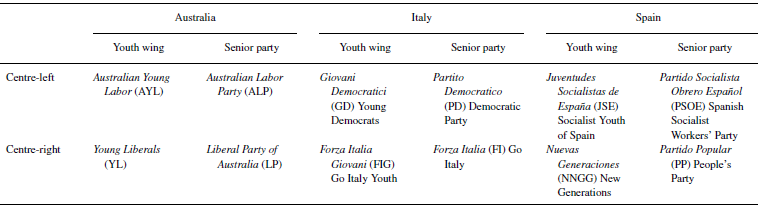

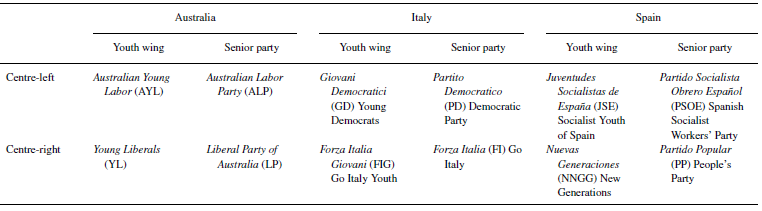

To investigate whether the two types of nascent political ambition vary among women and men in youth wings, we draw upon original survey data from 1,915 youth wing members of six parties in Australia, Italy and Spain (see Table 1). In each country, we look at the two main centre‐right and centre‐left parties since these are usually the traditional parties of government, with well‐established nationwide organizations.Footnote 5 These three countries have been chosen because they differ as regards two institutional factors which can influence the representation of women in politics, and can thus indirectly affect the political ambitions of young women: electoral systems and national gender quota laws (for a review, see Krook & Schwindt‐Bayer, Reference Krook, Schwindt‐Bayer, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Laurel Weldon2013). In terms of electoral systems, Australia has a majoritarian voting system, Italy a mixed‐member one, and Spain proportional representation. Furthermore, Australia is the only country among the three without a national law regulating electoral gender quotas, while Spain and Italy saw the introduction of legislative quotas in 2007 and 2017, respectively. In terms of representative trends, Spain in 2022 had the highest proportion of women members of the Lower House (43 per cent), followed by Italy (36 per cent) and Australia (31 per cent).Footnote 6 Accordingly, we would expect gender gaps in electoral ambition to be greatest in Australia and lowest in Spain, with Italy in between the two.

Table 1. Youth wings surveyed in Australia, Italy and Spain

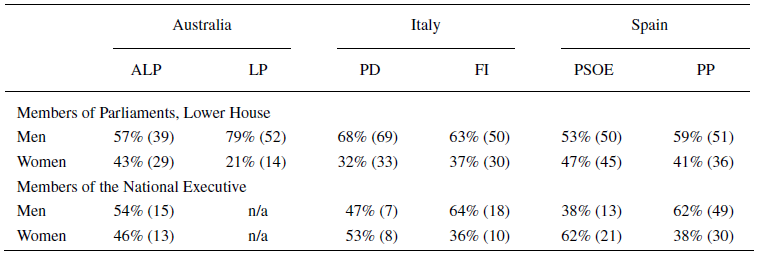

Youth wings are a key part of the pipeline for political elite careers in these three countries. For example, in early 2022, three of the party leaders of our six cases (ALP in Australia, PD in Italy, PP in Spain) had been leading figures in youth wings when they were young adults.Footnote 7 There is thus a clear political career pathway from youth wings in all three countries, as also occurs in other parliamentary democracies such as Germany (Ohmura et al., Reference Ohmura, Bailer, Meiβner and Selb2018) and Denmark (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Nielsen, Pedersen and Tromborg2020). While there are similarities across our six parties, there are also some relevant differences. In each country, the centre‐left has set higher quotas than the centre‐right for the proportion of women candidates at elections and in senior party organization roles.Footnote 8 Furthermore, as Table 2 shows, in both Australia and Spain, the centre‐left parties have higher percentages of women in the Lower Houses of parliament than their centre‐right counterparts. Similarly, if we look at the members of each party's national executive, we find that the centre‐left parties in Italy and Spain have a larger proportion of women than the centre‐right ones. The differences between the two party families, as regards the adoption of quotas and the presence of women in senior positions, reinforce our expectations that women in centre‐left youth wings will be more ambitious than those in centre‐right ones, both as regards the desire to stand as a candidate and the aspiration to work for the party.

Table 2. Gender distribution of MPs and members of party National Executives

Source: For the data on MPs, official websites of the House of Representatives (Australia), Camera dei Deputati (Italy), Congreso de los Diputados (Spain). For the data on the National Executive, official websites of the parties. The Liberal Party in Australia does not provide publicly accessible data about the composition of its executive.

Note: The absolute numbers of MPs and members of the National Executives are in brackets. Data was collected in January 2022.

Our selection of cases thus encompasses six parties that not only differ in their ideology, party quota provisions and levels of women's representation, but operate in three countries which vary according to electoral systems and national gender quota laws. By accounting for a variety of party‐level and country‐level factors which may influence the gendered nature of political ambition, we expect that our findings on the career aspirations of young women and men in youth wings can be generalized to youth wings of mainstream parties in parliamentary democracies more broadly.

Method and data

We conducted a survey with the six youth wings over the course of 3 years, between 2018 and 2021. Our questionnaire was available in English, Italian and Spanish on the online platform LimeSurvey. It was open only to people aged 18 and above. The Australian survey was launched in March 2018 and concluded in November that year, while the Spanish and Italian ones took place between March 2020 and April 2021. The long timeframe for each survey was due to the difficulties of securing distribution among the youth wing memberships. As party organization scholars have documented (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015; Gauja & Kosiara Pedersen, Reference Gauja and Kosiara‐Pedersen2021), political parties are often highly reluctant not only to release membership lists or details about their membership to researchers but also to distribute requests for participation in academic research to members.

In our research, we encountered many issues of data availability and cooperation across all six cases.Footnote 9 To begin with, in Australia, we had to ask the leaders of Young Labor and the Young Liberals in each of the country's six states and two territories to distribute the survey link to their members, since membership details are held at subnational level. By contrast, in Italy and Spain, the four youth wings kept a national membership list. We therefore first requested their national leaders to send the link to the membership.Footnote 10 However, this did not produce many responses from any of the Italian and Spanish parties. We then adopted the same strategy as we had used in Australia and directly asked the youth wing leaders of each party in all 20 Italian regions and 17 Spanish autonomous communities to distribute the link to their local members. On those occasions when young party leaders ignored our requests, we contacted the senior party leaders in their area, so that they could encourage participation. While ours is a non‐random sample, and we should therefore be careful when generalizing our findings, we were eventually able to secure good geographical coverage, with all four of Australia's largest states and three quarters of Italian regions and Spanish autonomous communities being represented across the six parties.Footnote 11 Since the youth wings, like most political parties, were extremely secretive about how many members they have, it is impossible for us to say what proportion of members responded to our survey.Footnote 12 In any case, even when parties do provide researchers with their membership numbers, these can be notoriously unreliable (Gauja & Kosiara Pedersen, Reference Gauja and Kosiara‐Pedersen2021, p. 9; Mair & van Biezen, Reference Mair and van Biezen2001, p. 7).Footnote 13

The survey first asked a series of demographic questions, followed by questions about the reasons why people had joined the youth wing. Subsequently, respondents had to indicate whether they had been in the youth wing for more than 12 months.Footnote 14 This was because we are interested in the political ambitions of those members who have demonstrated a basic level of commitment to party participation by renewing their annual membership at least once. Those that remained in the survey were then asked about the activities they performed as members, along with their future political ambitions. Specifically related to our research purposes, participants were asked to what extent they agreed with the following statements: ‘In the future, I would like to stand as a candidate for the senior party’ and ‘In the future, I would like to work for the senior party’. They could choose between answer options on a 5‐point Likert scale (‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘disagree’, ‘strongly disagree’, ‘don't know’). Given our focus on gender differences in nascent political ambition among youth wing party members, we created two binary dependent variables from the two survey questions reported above. The first dependent variable concerns whether the respondent agreed or disagreed with the idea that they would like to stand as a candidate in the future. We coded this as 0 if the respondent disagreed or strongly disagreed with that option and 1 if the respondent agreed or strongly agreed. We applied the same logic to our second dependent variable, which investigates whether they would like to work for the party in the future. In each case, we excluded from the analysis those individuals who chose the residual category ‘don't know’.Footnote 15

The main explanatory variable in our analysis is the respondent's gender. To test the hypotheses regarding the existence of a gender gap in electoral and non‐electoral ambition, we coded respondents according to their gender (0 = man; 1 = woman). Besides gender, there are other sociodemographic variables that may affect political ambition among youth wing party members. The first is the age of the respondent (measured in years), as we know that the incentives to seek elected office decrease as individuals get older (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005; Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006). The second concerns the educational status of the respondent. This is because individuals with higher levels of education may have better skills and stronger motivations to pursue a political career (Allen & Cutts, Reference Allen and Cutts2018). In this case, we assigned a code to respondents based on their educational status: 0 = secondary education or lower; 1 = tertiary education.Footnote 16 Finally, we also control for the role of family socialization, as this is likely to affect political ambition (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2014; Allen & Cutts, Reference Allen and Cutts2018). We investigate it with a question about whether anyone in the respondent's immediate family (parents and siblings) had ever been a member of any political party. We coded this as 0 if the respondent replied ‘No’ and 1 if they answered ‘Yes’.

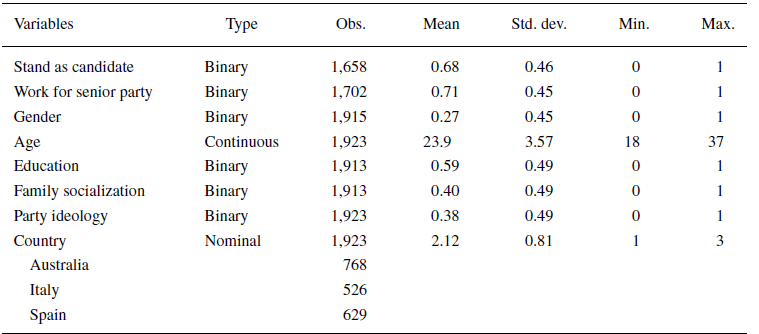

In addition to these sociodemographic variables, we included a variable which measures the party ideology of the youth wing organizations (0 = centre‐left, for AYL, GD, JSE; 1 = centre‐right, for YL, FIG, NNGG), to test the second part of our argument, namely that women in centre‐left youth wings will be more ambitious than those in centre‐right ones. Finally, we control also for the existence of country‐specific factors (with a categorical variable: 1 = Italy, 2 = Spain; 3 = Australia). The descriptive statistics of the variables employed in our analysis are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics

Gender and nascent political ambition in youth wings

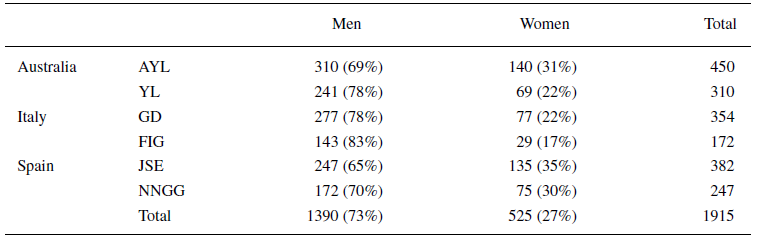

In this section, we present the results of our empirical analysis, beginning with the profiles of our respondents according to the variables listed in Table 3. As we can see from Table 4, men far outnumbered women among our respondents. While this is true of all six youth wings, there are country and party ideology differences. According to our survey, the Spanish and, to a lesser extent, the Australian youth wings have larger proportions of women members than the Italian ones. Within each country, we can see that the proportion of women from the centre‐right who responded to our survey was lower than that from the centre‐left, suggesting that the centre‐left youth wings may have higher percentages of women members than their centre‐right rivals. This would reflect what we know about the gender distribution of party members in senior parties, since left‐wing parties usually have higher proportions of women members than right‐wing ones do (van Haute & Gauja, Reference van Haute and Gauja2015). As regards other characteristics, we find that women and men in the six youth wings have a similar profile in terms of age, but they exhibit differences in the level of educational attainment (64.9 per cent of women and 57.1 per cent of men are university graduates) and family socialization (52.4 per cent of women compared to 35 per cent of men say someone in their immediate family either is, or has been, a member of a political party).Footnote 17

Table 4. Gender composition of survey participants

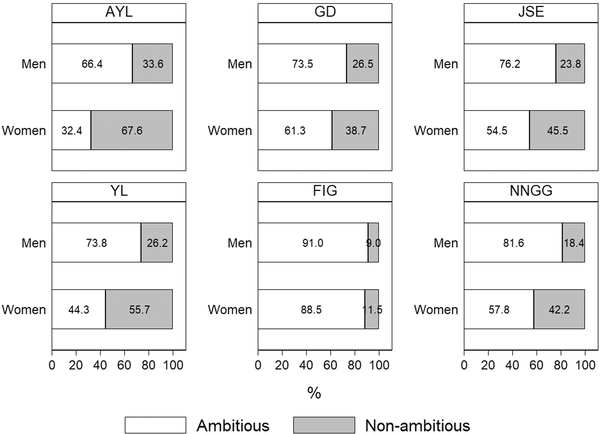

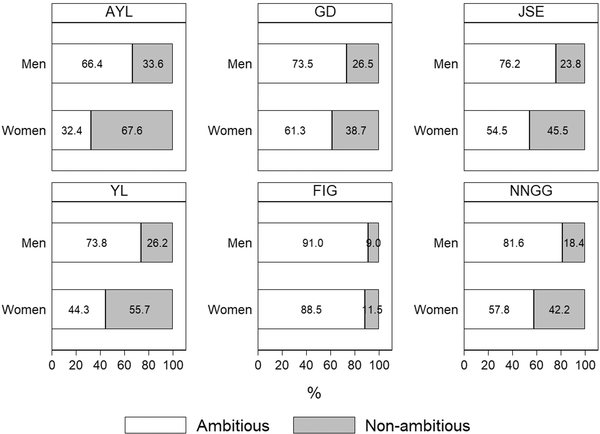

The first type of nascent political ambition we analyse is the desire to stand as a candidate in the future. Overall, 75.5 per cent of the men and 51.2 per cent of the women we surveyed are interested in standing for election one day. Figure 1 shows the proportions of electorally ambitious and non‐ambitious members by youth wing and gender. In all six youth wings, the proportion of women who say they would like to become candidates is lower than that of men. As we expected, Australia presents the largest gender gap, with the percentage of electorally ambitious women in both youth wings around 30 percentage points lower than that of electorally ambitious men. However, despite Spain's greater percentage of women MPs than Italy and its proportional electoral system compared to Italy's mixed one (two factors that are said to favour women's political engagement and aspirations), both the JSE and NNGG fare worse than their Italian counterparts. This speaks to research on the relative importance of the mere quantity of elected women in fostering political ambition among other women (Broockman, Reference Broockman2014; Gilardi, Reference Gilardi2015). Notwithstanding these country differences, it is worth noting that women and men in youth wings display high levels of electoral ambition generally, as other studies have shown (Bruter & Harrison, Reference Bruter and Harrison2009; Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2022). In particular, this is a feature of the centre‐right youth wings in our sample, with both women and men in those parties being more inclined than their counterparts in the centre‐left to say they would like to be candidates.

Figure 1. Desire of youth wing members to stand as candidates, by gender (in per cent).

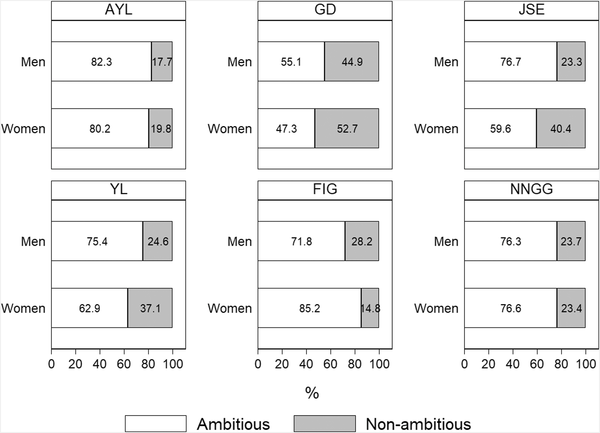

The second type of nascent political ambition we analyse is the desire to work for the party. Among our respondents, 72.5 per cent of men and 67.3 per cent of women were interested in a non‐electoral political career. As Figure 2 shows, in most of our youth wings, the gap between women and men which we had seen for electoral ambition either shrinks or is reversed when we examine non‐electoral ambition. For example, what had been a 32‐point gender gap for the centre‐left Australian AYL when we looked at the ambition to be a candidate becomes just a 2‐point one when we focus on the ambition to work for the party. Likewise, an almost 24‐point gap in the Spanish centre‐right NNGG regarding standing for election disappears, with a fractionally higher percentage of women than men saying they are interested in a party career. In terms of country differences, Italy runs contrary to Australian and Spanish trends. In all four Australian and Spanish cases, the share of women expressing the ambition to work for the party is higher than it was for standing as a candidate. By contrast, in Italy, working for the party is a less appealing career prospect for both women and men. Finally, the trends for party ideology are less uniform. In Australia, women and men in the centre‐left youth wing are more non‐electorally ambitious than their counterparts on the centre‐right. In Italy, we find the opposite, with women and men on the centre‐right more non‐electorally ambitious than those on the centre‐left, while in Spain the results are mixed.

Figure 2. Desire of youth wing members to work for the party, by gender (in per cent).

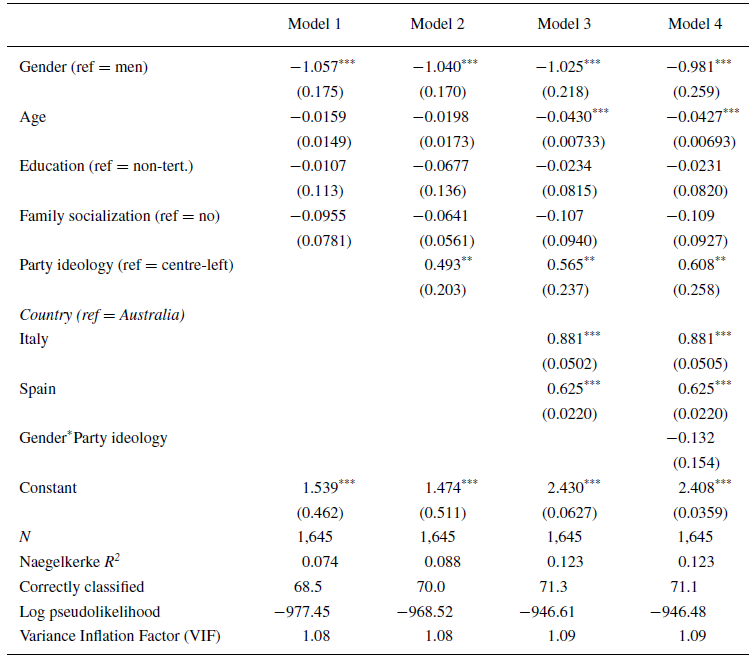

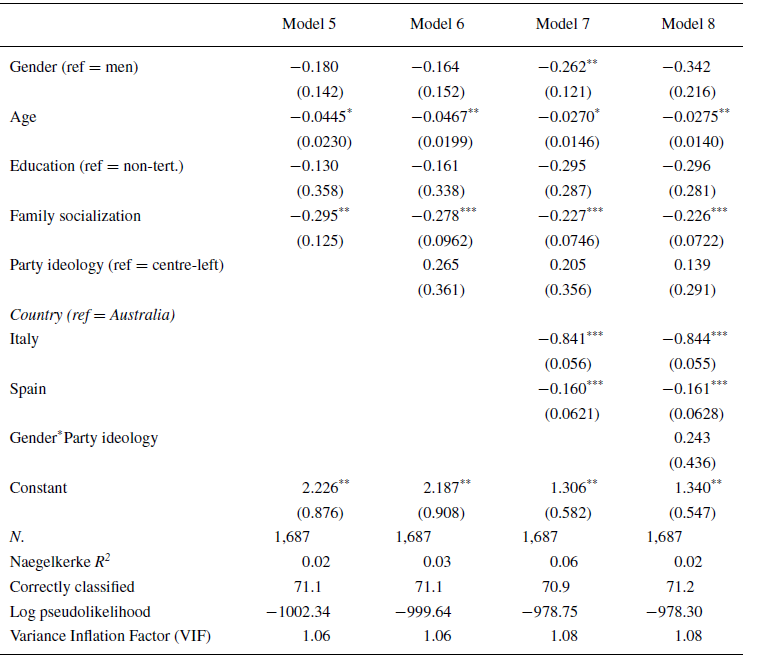

To obtain a more robust estimation of the association between our main explanatory variable (gender) and both electoral and non‐electoral nascent ambition, we ran a series of binomial logit regressions with the two ambition types as dependent variables.Footnote 18 We account for the non‐independence of observations within the same country by computing standard errors clustered at the country level (Steenbergen & Jones, Reference Steenbergen and Jones2002). Tables 5 and 6 report the results of two sets of regression models designed to test our hypotheses. Models 1–4 investigate the desire to stand as candidates, while Models 5–8 focus on the desire to work for the party. Both sets of regression models assess, first, the effect of sociodemographic factors (gender, age, education, family socialization: Models 1 and 5), and then progressively include ideological (party ideology: Models 2 and 6) and contextual factors (country: Models 3 and 7). Lastly, Models 4 and 8 investigate the effect of the interaction between gender and party ideology on the political ambitions of youth wing members.

Table 5. Correlates of electoral political ambition among youth wing members

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses:

*** p < 0.01,

** p < 0.05,

* p < 0.1.

Table 6. Correlates of non‐electoral political ambition among youth wing members

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses:

*** p < 0.01,

** p < 0.05,

* p < 0.1.

Model 1 provides support for our first hypothesis (H1a) that men in youth wings are more likely than women to want to stand as candidates in the future. A gender gap in electoral ambition thus exists among young party members, just as it does among more senior ones (Davidson‐Schmich, Reference Davidson‐Schmich2008; Kjaer & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019). After having controlled for other sociodemographic factors, the gender variable remains negatively associated with the desire to run for public office. More importantly, among other predictors included in the analysis, gender exerts a substantial effect under all model specifications (Models 1–4) and is the strongest factor explaining this type of nascent political ambition.

As regards other sociodemographic factors, age is negatively correlated with the desire to stand, as expected (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005, Allen & Cutts, Reference Allen and Cutts2018). In other words, younger youth wing members are more interested in running for elected office than older ones. Furthermore, education has no discernible effect on this type of career aspiration, despite studies suggesting the contrary (Allen & Cutts, Reference Allen and Cutts2018). This is likely to be because we are looking at a homogeneous sample of educated people, with 55 per cent of the respondents possessing (at least) a university degree. With regard to the final sociodemographic variable, our analysis reveals that family socialization does not foster electoral ambition. This finding runs contrary to the results of other studies, which have shown that having close relatives involved in politics has a positive impact on political career aspirations (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005; Allen & Cutts, Reference Allen and Cutts2018). It may therefore be the case that the political socialization experienced by children at early ages has a stronger and longer‐lasting effect than family socialization (Lawless & Fox, Reference Lawless and Fox2015; Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022).

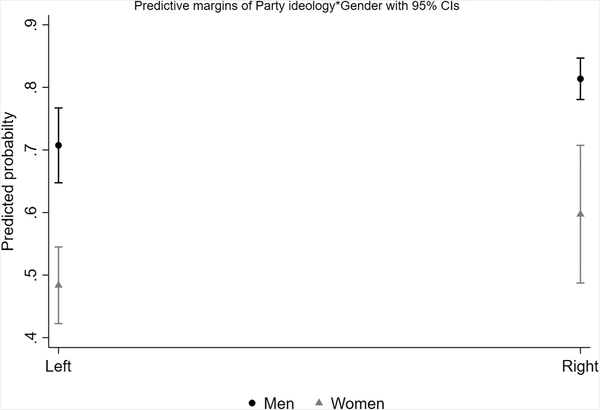

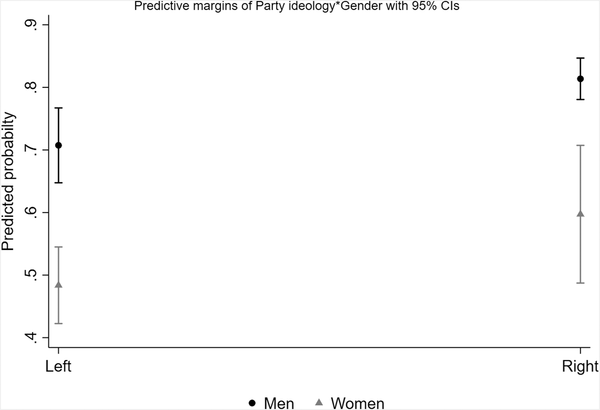

Our analysis also shows that members of centre‐right youth wings are more likely than those in centre‐left ones to express the desire to run for public office. Most importantly, and going against our expectation in Hypothesis H2a, the interaction term between gender and party ideology included in Model 4 shows that women in centre‐left youth wings are not more likely than women in centre‐right ones to want to stand as candidates in the future. If anything, as Figure 3 indicates, women in centre‐left youth wings are less electorally ambitious than women on the centre‐right, even though these differences are not statistically significant. Moreover, when we look at candidate aspirations among women members only, the results confirm that being in a centre‐right youth wing is a strong predictor of wanting to stand as a candidate (see Table D5 in Online Appendix D). These findings lead us to reject Hypothesis 2a.

Figure 3. Desire to stand as candidates: interaction of party ideology with gender.

Note: Based on the results of Model 4.

The results of the logistic regressions in Table 6 address H1b and H2b. The most significant finding from the four Models (5–8) is that the gap between women and men as regards non‐electoral ambition is considerably lower. In fact, with the sole exception of Model 7, the effect of gender on our second type of political ambition substantially weakens and loses statistical significance.Footnote 19 Accordingly, these findings provide support for H1b, and are in line with recent research suggesting that women may prefer less visible political careers over more public ones (Bauer & Darkwah, Reference Bauer and Darkwah2020; Kolltveit, Reference Kolltveit2021). As our study demonstrates, if we examine aspirations for non‐electoral roles such as party officials and advisors, young women members are almost as interested as men in pursuing a political career.

When looking at the sociodemographic variables, Table 6 shows that neither gender nor education has a significant impact on the desire to work for the party, while age and family socialization do. Firstly, younger members of youth wings are more likely to say they would like work for the party in the future. Secondly, having a close relative who has been a party member reduces the likelihood of wanting to work for a political party. While not the focus of our study, this finding points to the need for further research on the influence exerted by family ties on political participation.

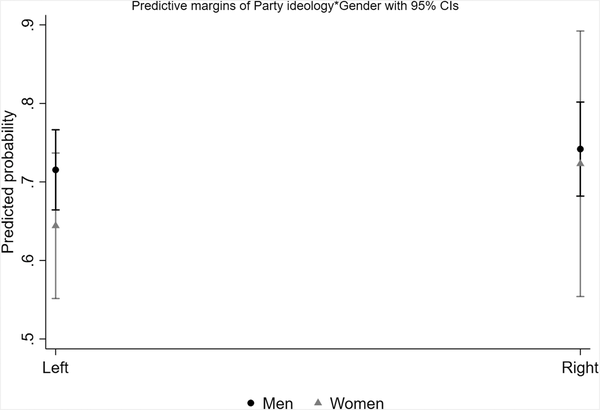

Moving on to party ideology, Model 6 shows that, contrary to what we have seen in relation to candidate aspirations, centre‐right and centre‐left youth wing members are similarly interested in a non‐electoral political career. Furthermore, although H2b predicted that women in centre‐left youth wings would be more likely than women in centre‐right ones to want to work for the party, the coefficient of the interaction term between gender and party ideology (Model 8) shows that this is not the case. In fact, both Figure 4 and supplementary analyses looking only at the women among our respondents (see Table D5 in Online Appendix D) indicate that there are no significant differences between centre‐right and centre‐left women in this sense. We therefore reject H2b.

Figure 4. Desire to work for the party: interaction of party ideology with gender.

Note: Based on the results of Model 8.

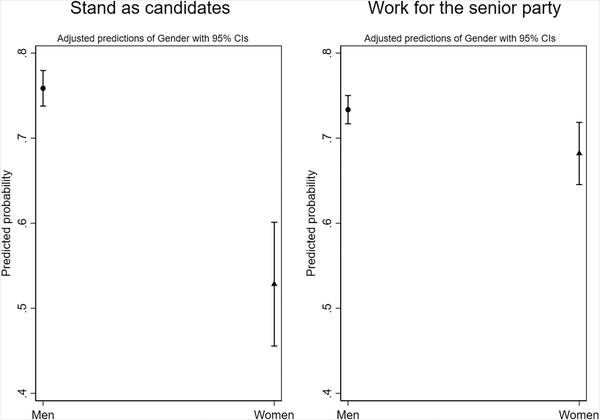

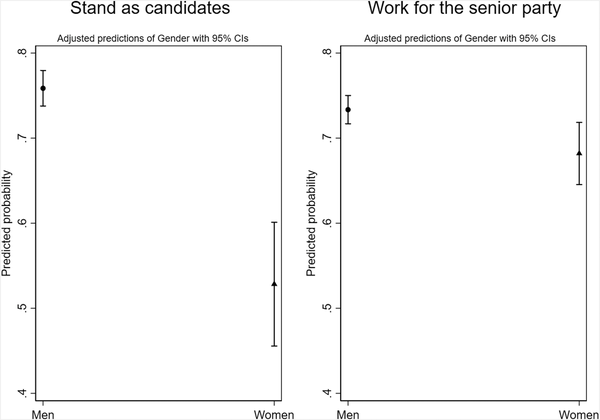

In sum, as Figure 5 clearly sets out, our study reveals that while women in youth wings are much less likely than men to want to stand as candidates, the same is not the case if we look at the desire to work for the party one day. In fact, the predicted gender gap for the electoral ambition to stand as candidates is almost five times larger than that concerning the non‐electoral ambition to work for the party (23 vs. 5 percentage points).

Figure 5. Effect of gender on the probability of being a politically ambitious youth wing member.

Note: Based on the results of Models 4 and 8.

To corroborate the robustness of our findings, all main regression models were re‐estimated under different specifications and separately for distinct subsets of the whole sample: for each youth wing (Models 9–20 in Tables D1 and D2 in Online Appendix D), for each country (Models 21–26 in Table D3), for each ideological orientation (Models 27–30 in Table D4), for only women (Models 31–32 in Table D5), excluding one country at a time (Models 33–38 in Table D6), and excluding one youth wing at a time (Models 39–50 in Tables D7 and D8). Moreover, we also ran models including those respondents who chose not to express a view within the category of the non‐ambitious (Models 51–58 in Tables D9 and D10) and using an inverse‐probability weighting method to control for differences in the numbers of respondents for each youth wing (Models 59–66 in Tables D11 and D12) and each party family (Models 67–74 in Tables D13 and D14). Finally, we re‐ran all our models with the original dependent variables with four categories (i.e. strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree) through ordered‐logistic regressions (Figures D1 and D2). Overall, our main findings are supported by these tests and indicate that the non‐electoral ambition gender gap is neither as strong nor as universal as the electoral ambition one.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the advances made in recent decades, there are still less women than men pursuing careers as parliamentarians and party officials in democracies around the world. While certainly not the only cause of underrepresentation, one important supply‐side factor is the gender gap in nascent political ambition. A rich body of literature, mostly based on the United States, has shown that women are less interested in standing as candidates than men (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005; Crowder‐Meyer, Reference Crowder‐Meyer2020), with studies revealing how gender disparities in political career aspirations already emerge by young adulthood (Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2014; Pruysers & Blais, Reference Pruysers and Blais2017). In this article, we set out to investigate whether the ambition gap also holds true among those young women and men who participate in a key entry point for political careers in parliamentary democracies: party youth wings. To do so, we looked at two types of political ambition: the aspiration to run for office (electoral ambition) and that to pursue careers within party organizations (non‐electoral ambition).

Between 2018 and 2021, we surveyed almost 2,000 members of three centre‐left and three centre‐right youth wings in Australia, Italy and Spain. We examined their nascent political ambition by asking those members who had been in the youth wings for at least a year, firstly, whether they would like to stand as a candidate one day, and, secondly, whether they would like to work for the party in the future. We found that youth wing members, in general, are an extremely politically ambitious group: 68.6 per cent of youth wing members expressed electoral ambition while 71 per cent of them displayed non‐electoral ambition. This underlines previous findings that youth wings are a great resource of potential candidates and personnel for political parties (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Bruter & Harrison, Reference Bruter and Harrison2009). Political ambitions are not evenly distributed among women and men, however. Instead, it depends on the type of political career. While women have a markedly lower interest in running for public office, they are almost as likely as men to aspire to a non‐electoral role working for the party. Furthermore, and contrary to our expectations, women in centre‐right youth wings are no less ambitious than women in centre‐left ones. These findings of course come with the caveat that – as is the norm in party membership research – ours is a non‐random sample. As such, a certain degree of caution should be applied when generalizing our findings. On the other hand, our approach of studying a very specific group of young people – members of youth wings – provides us with a unique perspective on the pipeline of the future political class.

Our results have several important implications. First, they reinforce previous research on the gender gap in electoral ambition, by showing that this gap is very much present even amongst politically interested young women who participate in party youth wings. At the same time, however, they indicate that these young women are not necessarily less interested than men in pursuing a political career. Rather, women are more likely to prefer one that does not involve standing for election, but still gives the opportunity to influence party policies, choices and strategies. There are many possible reasons for this, such as the fact that women candidates are subject to unique forms of abuse and harassment that men are not (Bauer & Darkwah, Reference Bauer and Darkwah2020; Krook & Restrepo Sanín, Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2020). Qualitative studies, for example involving focus groups, among youth wing members might help reveal more about the dynamics underpinning the differences we have found between women's electoral and non‐electoral nascent political ambition.

Second, while the absolute numbers of politically ambitious women in centre‐right youth wings appear lower than those in the centre‐left, and so the pipeline of the latter has more potential to improve women's representation (Thomsen & King, Reference Thomsen and King2020), our study indicates that the adoption of quotas and a greater presence of women in high‐ranking public and party positions do not necessarily translate into higher levels of political ambition among centre‐left young women at the grassroots. Further research could examine why this is the case, with one hypothesis being that, because centre‐left youth wings provide a more welcoming atmosphere for women, they attract women with a more diverse range of purposive and social motivations for joining, beyond the aim of pursuing a political career. Still, since our results about the relative ambitions of centre‐right and centre‐left women contrast with the findings of a study among senior party members in Denmark (Kjaer & Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Kjaer and Kosiara‐Pedersen2019, p. 11), we encourage scholars to investigate whether political career aspirations vary between women of different generations in right‐wing and left‐wing parties.

It is worth emphasizing at this point that, while studies on the gender gap in nascent political ambition are important for understanding women's underrepresentation in politics, we know this gap is not the only explanation. As Piscopo (Reference Piscopo2019, p. 825) has argued, ‘this frame overlooks the very systemic barriers it purports to identify, and fails to raise important questions about who bears responsibility for making politics more diverse, representative, and responsive’. Political parties, even when promoting quotas, place a series of institutional obstacles and gatekeeping practices which hinder women's participation in political life (Bjarnegård, Reference Bjarnegård2013, Verge & de la Fuente, Reference Verge and de la Fuente2014). In this context, a lack of expressed ambition may simply reflect ‘a rational decision to opt out of candidacy given a gendered political opportunity structure’ (Piscopo & Kenny Reference Piscopo and Kenny2020, p. 4). Women's underrepresentation in politics thus results from the constant interaction of supply‐side and demand‐side factors, as ‘gender differences in aspirations to compete for public office might well be shaped by gendered patterns of participation in the party organization’ (Verge Reference Verge2015, p. 755). In other words, the onus is squarely on party elites, of both left and right, to facilitate women's participation in political life.

To make political careers in parliamentary democracies more appealing to women involves, first and foremost, making joining a party more attractive. As the gender distribution of our respondents suggests, there is already a significant imbalance at the youth wings stage in the future candidate and party official pipeline. Given that, in parliamentary democracies, parties draw most of their candidates and officials from within their memberships (Hazan & Rahat, Reference Hazan and Rahat2010; Karlsen & Staglie, Reference Karlsen and Saglie2017), a key issue they need to address is recruiting higher numbers of women. Youth wings are a vital area on which to concentrate their efforts, especially since, as Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004, p. 207) argue, if such initiatives only begin in earnest when members are in the senior party, ‘patterns of inequality will already have been well established’. To conclude, we encourage scholars not only of gender and politics, but also of political parties, to study these key party sub‐organizations that have been largely overlooked. If we want to better understand the political class of tomorrow and the representation trends that will shape our democracies, we need to look at the youth wings of today.

Acknowledgements

Many colleagues provided useful feedback on earlier drafts of this study. In particular, we would like to thank Niklas Bolin, Caterina Froio, Max Grömping, Glenn Kefford, Ferran Martinez i Coma and Lee Morgenbesser.

Open access publishing facilitated by Griffith University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Griffith University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table B1. Australia.

Table B2. Italy.

Table C1. Correlation matrix.

Table C2. Crosstab of the two dependent variables, row percentages.

Table C3. Men and women youth wing members.

Table C4. Frequency table for the two dependent variables including the ‘don't know’ option.

Table D1. Desire to stand as candidates, by youth wing.

Table D2. Desire to work for the party, by youth wing.

Table D3. Desire to stand as candidates and work for the party, by country.

Table D4. Desire to stand as candidates and work for the party, by party ideology.

Table D5. Desire to stand as candidates and work for the party, only among women.

Table D6. Desire to stand as candidates and work for the party, excluding one country at a time.

Table D7. Desire to stand as candidates, excluding one youth wing at a time.

Table D8. Desire to work for the party, excluding one youth wing at a time.

Table D9. Desire to stand as candidates (with non‐ambitious including ‘don't know’ answers).

Table D10. Desire to work for the party (with non‐ambitious including ‘don't know’ answers).

Table D11. Desire to stand as candidates (sample weighted by frequency of youth wings).

Table D12. Desire to work for the party (sample weighted by frequency of youth wings).

Table D13. Desire to stand as candidates (sample weighted by ideological orientation)

Table D14. Desire to work for the party (sample weighted by ideological orientation).

Figure D1. Desire to stand as candidates: predicted probabilities from ordered logit regression.

Figure D2. Desire to work for the party: predicted probabilities from ordered logit regression.