1 Introduction

Investigating causal relationships among variables is a fundamental goal of psychological research. By establishing causality, researchers can uncover the mechanisms that govern human behavior and design effective interventions to change it (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025). When variable

![]() $X$

is the cause and variable

$X$

is the cause and variable

![]() $Y$

the effect, we denote this causal relation as

$Y$

the effect, we denote this causal relation as

![]() $X\to Y$

. For decades, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been regarded as the gold standard for causal inference because they systematically manipulate the putative cause and observe subsequent changes in the outcome. However, ethical constraints and practical costs often render RCTs infeasible, making the extraction of causal information from nonexperimental data a pressing issue across economics (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2010), sociology (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Zhou and Xie2023), education (Cordero et al., Reference Cordero, Cristóbal and Santín2018), computer science (Pearl, Reference Pearl2009), and psychology (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025). Current observational approaches fall into two broad categories: causal inference and causal discovery. Causal inference prespecifies the cause–effect pair and then estimates the true causal effect while adjusting for confounders (Schafer & Kang, Reference Schafer and Kang2008). Causal discovery, by contrast, leverages distributional properties to uncover the directionality of causal links directly from observational data (Glymour et al., Reference Glymour, Zhang and Spirtes2019; Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022), thereby offering an exploratory tool for theory construction (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025).

$X\to Y$

. For decades, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been regarded as the gold standard for causal inference because they systematically manipulate the putative cause and observe subsequent changes in the outcome. However, ethical constraints and practical costs often render RCTs infeasible, making the extraction of causal information from nonexperimental data a pressing issue across economics (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2010), sociology (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Zhou and Xie2023), education (Cordero et al., Reference Cordero, Cristóbal and Santín2018), computer science (Pearl, Reference Pearl2009), and psychology (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025). Current observational approaches fall into two broad categories: causal inference and causal discovery. Causal inference prespecifies the cause–effect pair and then estimates the true causal effect while adjusting for confounders (Schafer & Kang, Reference Schafer and Kang2008). Causal discovery, by contrast, leverages distributional properties to uncover the directionality of causal links directly from observational data (Glymour et al., Reference Glymour, Zhang and Spirtes2019; Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022), thereby offering an exploratory tool for theory construction (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025).

However, the causal relationships between psychological variables often exhibit a “chicken or egg” relationship in which the causal direction is ambiguous, such as pride and social rank (Witkower et al., Reference Witkower, Mercadante and Tracy2022), work–family conflict and strain (Nohe et al., Reference Nohe, Meier, Sonntag, Michel and Chen2015), and job insecurity and mental health complaints (Griep et al., Reference Griep, Lukic, Kraak, Bohle, Jiang, Vander Elst and De Witte2021). Some researchers treat these patterns as reciprocal relationships and analyze them with cross-lagged panel models (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Vaulont and Zhang2025). Recent work, however, suggests that the underlying causal direction may be unidirectional but heterogeneous across individuals that only

![]() $X\to Y$

or

$X\to Y$

or

![]() $Y\to X$

within any given subgroup (Zhang & Wiedermann, Reference Zhang and Wiedermann2024). Apparent reciprocity then arises from aggregating subpopulations with opposite directions—what we term heterogeneous causal directions. For example,

$Y\to X$

within any given subgroup (Zhang & Wiedermann, Reference Zhang and Wiedermann2024). Apparent reciprocity then arises from aggregating subpopulations with opposite directions—what we term heterogeneous causal directions. For example,

![]() $X\to Y$

may hold when

$X\to Y$

may hold when

![]() $Z\le 0$

multivariable contexts (e.g., De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Galand and Frenay2013; Sheu et al., Reference Sheu, Chong, Dawes and Kivlighan2022), but tools that are simultaneously multivariate and interpretable remain scarce.

$Z\le 0$

multivariable contexts (e.g., De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Galand and Frenay2013; Sheu et al., Reference Sheu, Chong, Dawes and Kivlighan2022), but tools that are simultaneously multivariate and interpretable remain scarce.

As many psychological theories posit unidirectional links (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Vaulont and Zhang2025), providing quantitative evidence for a specific causal direction—even through exploratory methods—can advance theory development. Although most causal-discovery algorithms assume data homogeneity, interest in heterogeneous causal directions is growing. Early investigations appeared in genomics, where the causal order among genes varies across samples (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Müller, Zhu and Ji2018; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). Social-science researchers have recently followed suit: Wiedermann and colleagues examined bidirectional heterogeneity between two variables (e.g., Li & Wiedermann, Reference Li and Wiedermann2020; van Wie et al., Reference van Wie, Li and Wiedermann2019; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024), and neural-network approaches have uncovered multivariate heterogeneity under different conditions (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024). These models, however, are largely black boxes; they describe what heterogeneous patterns emerge but not why. Such opacity hampers psychological theory, which prizes interpretability.

Recursive partitioning offers a promising alternative. By recursively splitting data according to if-then rules, tree-based models capture how covariates modulate variable relationships, yielding transparent, rule-based subgroups (Strobl et al., Reference Strobl, Malley and Tutz2009; Zeileis et al., Reference Zeileis, Hothorn and Hornik2008). Recursive partitioning has been integrated with numerous psychometric models to explore heterogeneous correlational patterns (Brandmaier et al., Reference Brandmaier, von Oertzen, McArdle and Lindenberger2013; Fokkema et al., Reference Fokkema, Smits, Zeileis, Hothorn and Kelderman2018; Fokkema & Zeileis, Reference Fokkema and Zeileis2024; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020; Kiefer et al., Reference Kiefer, Lemmerich, Langenberg, Mayer and Steinley2024). In causal inference, Bayesian additive regression trees (Chipman et al., Reference Chipman, George and McCulloch2010; Hill, Reference Hill2011) and causal trees (Athey & Imbens, Reference Athey and Imbens2016) successfully detect heterogeneous treatment effects. In causal discovery, recursive partitioning has also recently been used to identify heterogeneous causal directions between two variables (Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). Yet its application to multivariate heterogeneous causal directions remains largely unexplored.

The present study bridges this gap by combining causal-discovery techniques with tree-based recursive partitioning to identify and interpret multivariate heterogeneous causal directions. Specifically, we employ conditional inference trees (CTree; Hothorn, Hornik, & Zeileis, Reference Hothorn, Hornik and Zeileis2006)—a nonparametric tree algorithm—to partition participants into homogeneous subgroups defined by covariates. Within each subgroup, we apply the Structural Equation Likelihood Function (SELF; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018), a state-of-the-art causal-discovery method, to determine the causal ordering of multiple variables. We call this integrated approach the SELF-Tree method. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to introduce recursive partitioning into the discovery of multivariate heterogeneous causal directions.

We first review relevant literature on causal discovery, heterogeneous causal directions, and recursive partitioning. We then formalize the SELF-Tree framework and evaluate its performance under various conditions via simulation. Finally, we provide an empirical illustration to demonstrate its practical utility. Through these steps, we highlight how marrying causal discovery with tree-based partitioning can yield an interpretable, exploratory tool for uncovering multivariate heterogeneous causal structures, and we document the effectiveness of the SELF-Tree method.

2 Literature review

2.1 Causal discovery

In the causal-discovery framework, causal relationships are represented as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs; Greenland et al., Reference Greenland, Pearl and Robins1999; Morgan & Winship, Reference Morgan and Winship2014), also termed causal graphs. Let

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}={\left({X}_1,\dots, {X}_p\right)}^T$

denote the

$\boldsymbol{X}={\left({X}_1,\dots, {X}_p\right)}^T$

denote the

![]() $p$

random variables. The DAG encoding their causal relationships is

$p$

random variables. The DAG encoding their causal relationships is

![]() $\mathcal{G}=\left(V,E\right)$

, where

$\mathcal{G}=\left(V,E\right)$

, where

![]() $V=\left\{1,\dots, p\right\}$

indexes the nodes and node and

$V=\left\{1,\dots, p\right\}$

indexes the nodes and node and

![]() $i$

corresponds one-to-one of variable

$i$

corresponds one-to-one of variable

![]() ${X}_i\;\left(1\le i\le p\right)$

; in what follows, we sometimes refer to variable

${X}_i\;\left(1\le i\le p\right)$

; in what follows, we sometimes refer to variable

![]() ${X}_i$

and its corresponding node

${X}_i$

and its corresponding node

![]() $i$

interchangeably.

$i$

interchangeably.

![]() $E$

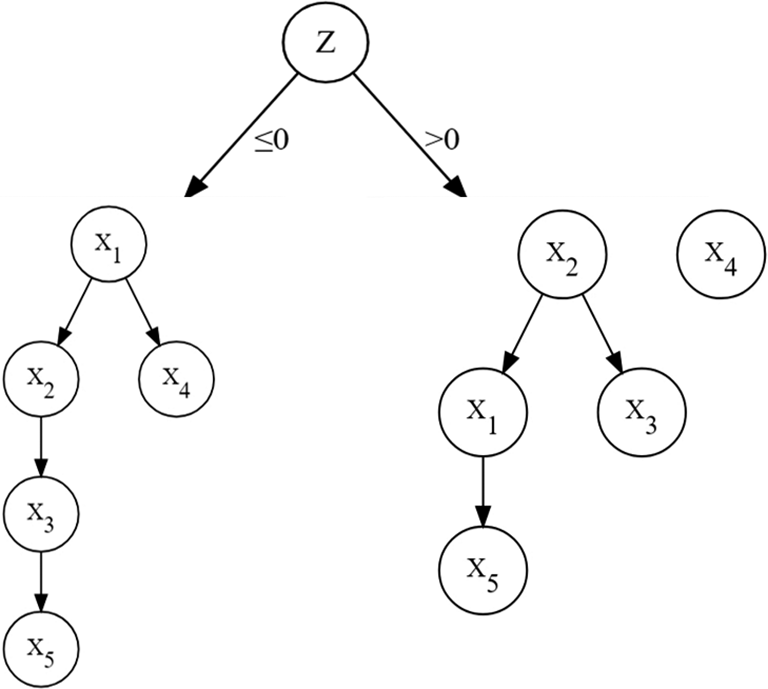

denotes the directed edges, which reflect the causal–effect relationships between variables. The nodes and directed edges are the two fundamental components of a DAG. Figure 1 provides an example:

$E$

denotes the directed edges, which reflect the causal–effect relationships between variables. The nodes and directed edges are the two fundamental components of a DAG. Figure 1 provides an example:

![]() ${X}_1\to {X}_2$

indicates that

${X}_1\to {X}_2$

indicates that

![]() ${X}_1$

exerts a direct causal influence on

${X}_1$

exerts a direct causal influence on

![]() ${X}_2$

, whereas the absence of the directed edge between

${X}_2$

, whereas the absence of the directed edge between

![]() ${X}_3$

and

${X}_3$

and

![]() ${X}_4$

implies no direct causal link. DAGs forbid simultaneous causation; only unidirectional edges are permitted, ruling out bidirected edges (e.g.,

${X}_4$

implies no direct causal link. DAGs forbid simultaneous causation; only unidirectional edges are permitted, ruling out bidirected edges (e.g.,

![]() ${X}_1\to {X}_2\to {X}_1$

) or cycles (e.g.,

${X}_1\to {X}_2\to {X}_1$

) or cycles (e.g.,

![]() ${X}_1\to {X}_2\to {X}_3\to {X}_1$

).

${X}_1\to {X}_2\to {X}_3\to {X}_1$

).

Figure 1 An example of a directed acyclic graph.

A DAG describes the data-generating process. For any

![]() $i\ne j\in V$

,

$i\ne j\in V$

,

![]() $i$

is the parent node of

$i$

is the parent node of

![]() $j$

if and only if

$j$

if and only if

![]() ${X}_i\to {X}_j$

, and

${X}_i\to {X}_j$

, and

![]() $P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

represents the set of all parent nodes of

$P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

represents the set of all parent nodes of

![]() ${X}_j$

in

${X}_j$

in

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

. The causal-discovery algorithms infer the true causal graph

$\mathcal{G}$

. The causal-discovery algorithms infer the true causal graph

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

from an observed dataset

$\mathcal{G}$

from an observed dataset

![]() $D$

. Two variables are connected by a path if they are linked through a sequence of nodes and directed edges. The path does not require the directed edges with the same direction. For instance, in Figure 1,

$D$

. Two variables are connected by a path if they are linked through a sequence of nodes and directed edges. The path does not require the directed edges with the same direction. For instance, in Figure 1,

![]() ${X}_3\leftarrow {X}_2\leftarrow {X}_1\to {X}_4$

constitutes a path between

${X}_3\leftarrow {X}_2\leftarrow {X}_1\to {X}_4$

constitutes a path between

![]() ${X}_3$

and

${X}_3$

and

![]() ${X}_4$

.

${X}_4$

.

To recover causal relations from data, three standard assumptions are usually invoked: causal sufficiency, the causal Markov property, and causal faithfulness (Glymour et al., Reference Glymour, Zhang and Spirtes2019; Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). The causal sufficiency states that every common cause of variables in the graph has been measured. The causal Markov property and causal faithfulness are complementary. The causal Markov property states that conditional independences in the joint probability distribution of the variables can be inferred from the d-separation in the causal graph

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

, whereas causal faithfulness asserts that every conditional independence found in the distribution corresponds to a d-separation in the graph (Pearl, Reference Pearl2009). Under these two assumptions, d-separations in

$\mathcal{G}$

, whereas causal faithfulness asserts that every conditional independence found in the distribution corresponds to a d-separation in the graph (Pearl, Reference Pearl2009). Under these two assumptions, d-separations in

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

are in one-to-one correspondence with conditional independencies in the joint probability distribution. When the assumptions hold, the joint distribution of the variables in

$\mathcal{G}$

are in one-to-one correspondence with conditional independencies in the joint probability distribution. When the assumptions hold, the joint distribution of the variables in

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

factorizes as follows:

$\mathcal{G}$

factorizes as follows:

$$\begin{align}\mathit{\Pr}\left(\boldsymbol{X}\right)=\prod \limits_{j=1}^p\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right\}\right)\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathit{\Pr}\left(\boldsymbol{X}\right)=\prod \limits_{j=1}^p\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right\}\right)\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_i\right)\right\}\right)$

denotes the conditional probability distribution of

$\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_i\right)\right\}\right)$

denotes the conditional probability distribution of

![]() ${X}_j$

given its parent nodes. Combining with the structure of

${X}_j$

given its parent nodes. Combining with the structure of

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

, it yields the corresponding joint probability distribution of variables, which is symbolled as

$\mathcal{G}$

, it yields the corresponding joint probability distribution of variables, which is symbolled as

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

(Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). Two DAGs,

$\mathcal{F}$

(Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). Two DAGs,

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

and

$\mathcal{G}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{G}^{\prime }$

, are said to belong to the same Markov equivalence class (MEC), if they generate probability distributions,

$\mathcal{G}^{\prime }$

, are said to belong to the same Markov equivalence class (MEC), if they generate probability distributions,

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

and

$\mathcal{F}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{F}^{\prime }$

, admit identical factorizations (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Madigan and Perlman1997). For example, both

$\mathcal{F}^{\prime }$

, admit identical factorizations (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Madigan and Perlman1997). For example, both

![]() ${X}_i\leftarrow {X}_j\to {X}_k$

and

${X}_i\leftarrow {X}_j\to {X}_k$

and

![]() ${X}_i\to {X}_j\to {X}_k$

imply the same factorization

${X}_i\to {X}_j\to {X}_k$

imply the same factorization

![]() $\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_i,{X}_j,{X}_k\right)=\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j\right)\times \mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_i\right|{X}_j\left)\times \mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_k\right|{X}_j\right)$

, even though the causal relationships between

$\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_i,{X}_j,{X}_k\right)=\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j\right)\times \mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_i\right|{X}_j\left)\times \mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_k\right|{X}_j\right)$

, even though the causal relationships between

![]() ${X}_i$

and

${X}_i$

and

![]() ${X}_k$

are totally different in the two graphsFootnote 1

.

${X}_k$

are totally different in the two graphsFootnote 1

.

Current causal-discovery methods fall into three broad classes: constraint-based, score-based, and distributional-asymmetry-based (Vowels, Reference Vowels2025). Constraint- and score-based methods, often referred to collectively as global view methods (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018), focus primarily on settings with more than two variables. Constraint-based approaches identify causal relations by testing conditional independencies; under the faithfulness assumption, these independencies are mapped onto graphical properties to yield an estimated

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

. Representative algorithms include the Peter–Clark algorithm (Spirtes et al., Reference Spirtes, Glymour and Scheines2000) and inductive causation (Pearl & Verma, Reference Pearl and Verma1995). Score-based methods search for the DAG that maximizes a scoring function

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

. Representative algorithms include the Peter–Clark algorithm (Spirtes et al., Reference Spirtes, Glymour and Scheines2000) and inductive causation (Pearl & Verma, Reference Pearl and Verma1995). Score-based methods search for the DAG that maximizes a scoring function

![]() $S\left(\mathcal{G},D\right)$

, i.e.,

$S\left(\mathcal{G},D\right)$

, i.e.,

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}={argmax}_{\mathcal{G}\in \mathbb{G}}S\left(\mathcal{G},D\right)$

, where

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}={argmax}_{\mathcal{G}\in \mathbb{G}}S\left(\mathcal{G},D\right)$

, where

![]() $\mathbb{G}$

is the set of all possible DAGs over the given nodes; the greedy equivalence search (Alonso-Barba et al., Reference Alonso-Barba, de la Ossa, Gámez and Puerta2013) is a well-known example. A key limitation of global-view methods is that they typically recover only a completed partially directed acyclic graph (CPDAG; Chickering, Reference Chickering2003) rather than a unique DAG, because they cannot fully resolve the Markov equivalence classes.

$\mathbb{G}$

is the set of all possible DAGs over the given nodes; the greedy equivalence search (Alonso-Barba et al., Reference Alonso-Barba, de la Ossa, Gámez and Puerta2013) is a well-known example. A key limitation of global-view methods is that they typically recover only a completed partially directed acyclic graph (CPDAG; Chickering, Reference Chickering2003) rather than a unique DAG, because they cannot fully resolve the Markov equivalence classes.

Distributional-asymmetry-based methods, also called local view methods (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018), focus on bivariate settings. They exploit nonlinearity or non-Gaussianity—features that produce structural asymmetries—to determine causal direction. Representative techniques include the linear non-Gaussian acyclic model (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Hoyer, Hyvärimen and Kerminen2006, Reference Shimizu, Inazumi, Sogawa, Hyvärinen, Kawahara, Washio, Hoyer and Bollen2011), additive noise models (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Mooij, Janzing and Schölkopf2014), post-nonlinear models (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Zhang and Schölkopf2016), information geometric models (Janzing et al., Reference Janzing, Mooij, Zhang, Lemeire, Zscheischler, Daniušis, Steudel and Schölkopf2012), and direction dependence analysis (DDA; Wiedermann, Reference Wiedermann2022).

Recognizing that each class of methods has distinct strengths and weaknesses, researchers have begun to combine them. The max-min hill-climbing (MMHC) algorithm (Tsamardinos et al., Reference Tsamardinos, Brown and Aliferis2006) first uses a constraint-based step to learn the skeleton of the graph and then employs a score-based step to orient the edges. Similar mixed-method approaches include the greedy fast causal inference method (Ogarrio et al., Reference Ogarrio, Spirtes and Ramsey2016) and the scalable causation discovery algorithm (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Zhang and Hao2013). A more recent example is the SELF algorithm (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018), which integrates score-based global optimization with distributional-asymmetry-based local decisions to yield a globally coherent DAG (rather than a CPDAG) while retaining the statistical rigor of local view methods (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Du, Yang and Li2022). The local view methods provide sharper insight into the causal direction between variable pairs, thereby avoiding the MEC in which the orientation can no longer be determined, whereas global view methods assemble local information to select the most plausible overall causal-graph structure and correct possible errors committed at the local level. The SELF algorithm yields a globally optimized model that retains local statistical significance and delivers a deterministic, theoretically robust decision on causal direction by integrating these two ideas (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018). The further algorithmic details of SELF are given in Section 3.2.

2.2 Identification for heterogeneous causal directionality

In traditional causal-discovery analysis, the data is often assumed to be independent and identically distributed (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018; Pearl, Reference Pearl2009). However, the real-world samples may not meet this assumption (Ickstadt et al., Reference Ickstadt, Bornkamp, Grzegorczyk, Wieczorek, Sheriff, Grecco, Zamir, Bernardo, Bayarri, Berger, Dawid, Heckerman, Smith and West2011; Oates et al., Reference Oates, Smith, Mukherjee and Cussens2016). If ignored, the overall model’s causal directions may greatly differ from the true ones (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024). Researchers commonly use the term heterogeneous causal structure learning to capture the possibility that complex data sets exhibit causal relationships that differ across subpopulations (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Bai, Xie, He, Zhao and Chen2025). Because participants may be drawn from distinct contexts—such as different geographic regions or time periods—their lifestyles often vary substantially. Such contextual differences can induce data heterogeneity: across subgroups, the distribution of noise variables, the magnitude of causal effects, and even the direction of causal relationships may all change (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Bai, Xie, He, Zhao and Chen2025).

Consequently, researchers have developed new causal-discovery methods to identify heterogeneous causal directions and obtain heterogeneous DAGs. These DAGs involve the same variables but different causal directions (i.e., directed edges). Early researchers focused on identifying heterogeneous DAGs directly from variables when the number of heterogeneous DAGs was known (e.g., Oates et al., Reference Oates, Smith, Mukherjee and Cussens2016; Yajima et al., Reference Yajima, Telesca, Ji and Müller2015) or unknown (e.g., Ickstadt et al., Reference Ickstadt, Bornkamp, Grzegorczyk, Wieczorek, Sheriff, Grecco, Zamir, Bernardo, Bayarri, Berger, Dawid, Heckerman, Smith and West2011). The heterogeneous reciprocal graphical models (hRGMs) offer a unified framework for analyzing heterogeneous DAGs, covering both known and unknown situations (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Müller, Zhu and Ji2018). Löwe et al. (Reference Löwe, Madras, Zemel and Welling2022) introduced an amortized causal-discovery framework that leverages neural-network models and temporal information to identify distinct causal graphs.

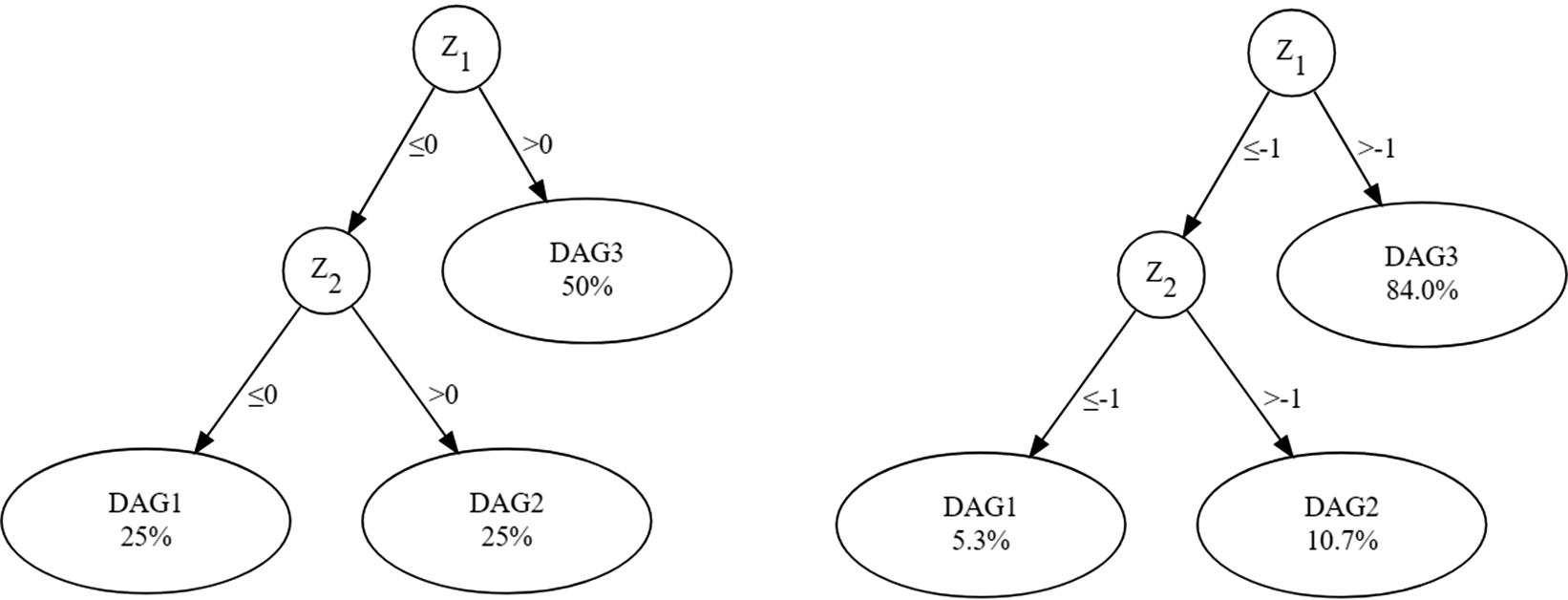

Recent studies have focused on how exogenous covariates affect causal directions (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). Figure 2 shows causal direction heterogeneity under different values of covariate

![]() $Z$

. Researchers proposed to incorporate covariates into the heterogeneous DAGs identification. For instance, Ni et al. (Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019) developed the Bayesian graphical regression (BGR) method, which allows the directed graph to change with multiple covariates, whether continuous, discrete, or a mix. BGR captures nonlinear relationships between DAGs and covariates using smooth and thresholding functions, enabling smooth DAG structure changes with covariate values. To ensure the effective identification of heterogeneous DAGs, BGR imposes sparsity constraints on directed edges based on a unified DAG.

$Z$

. Researchers proposed to incorporate covariates into the heterogeneous DAGs identification. For instance, Ni et al. (Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019) developed the Bayesian graphical regression (BGR) method, which allows the directed graph to change with multiple covariates, whether continuous, discrete, or a mix. BGR captures nonlinear relationships between DAGs and covariates using smooth and thresholding functions, enabling smooth DAG structure changes with covariate values. To ensure the effective identification of heterogeneous DAGs, BGR imposes sparsity constraints on directed edges based on a unified DAG.

Figure 2 Causal direction heterogeneity of variables under different covariate values.

A similar Bayesian approach for heterogeneous causal direction identification is the latent trajectory embedded Bayesian network (BN-LTE) method (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, He and Ni2023). It aggregates multiple covariates into a continuous latent variable (referred to as the pseudotime variable) and identifies heterogeneous causal directions based on the covariation between the latent variable and the DAG structure. The latent variable can be seen as a reordering of all covariates, enabling the DAG structure to change smoothly with it. Additionally, based on the latent variable, the BN-LTE method can identify certain Markov equivalence classes, aiding in clarifying the causal directions among variables.

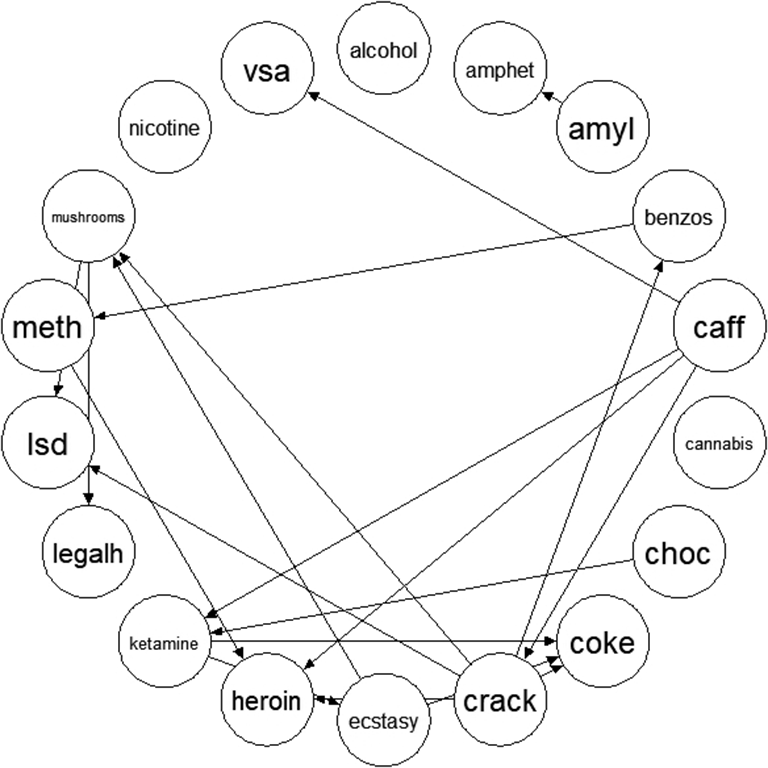

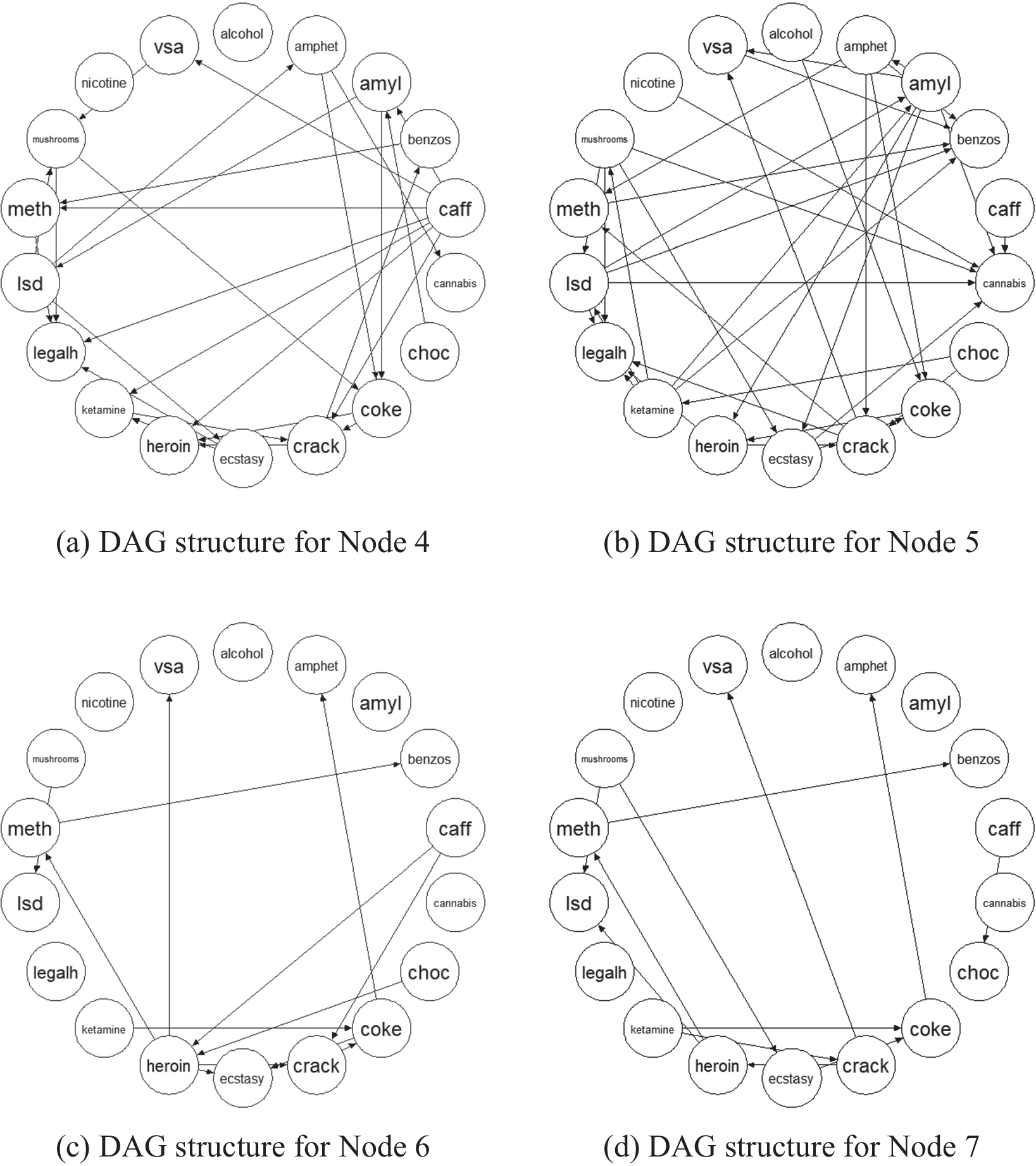

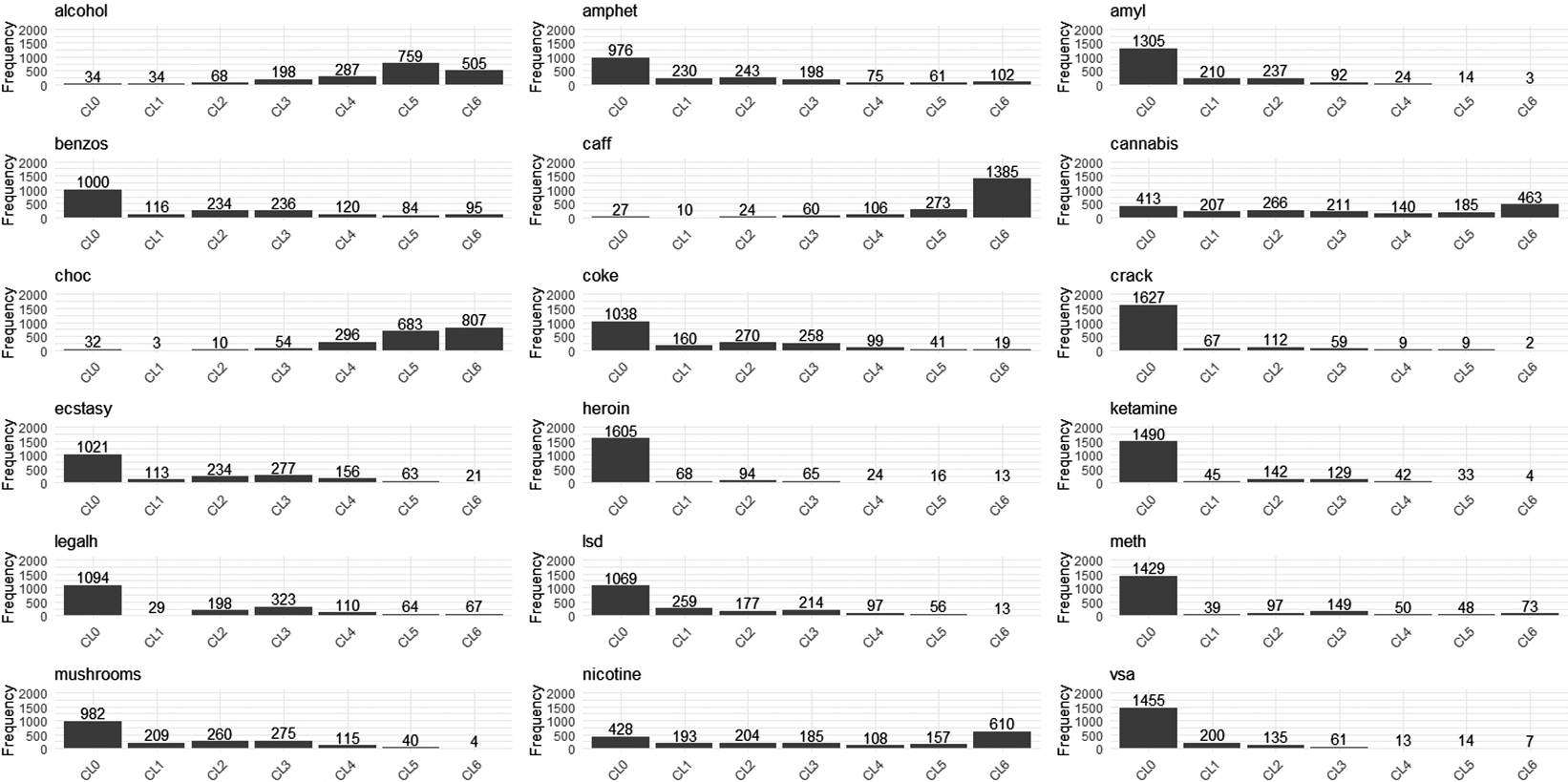

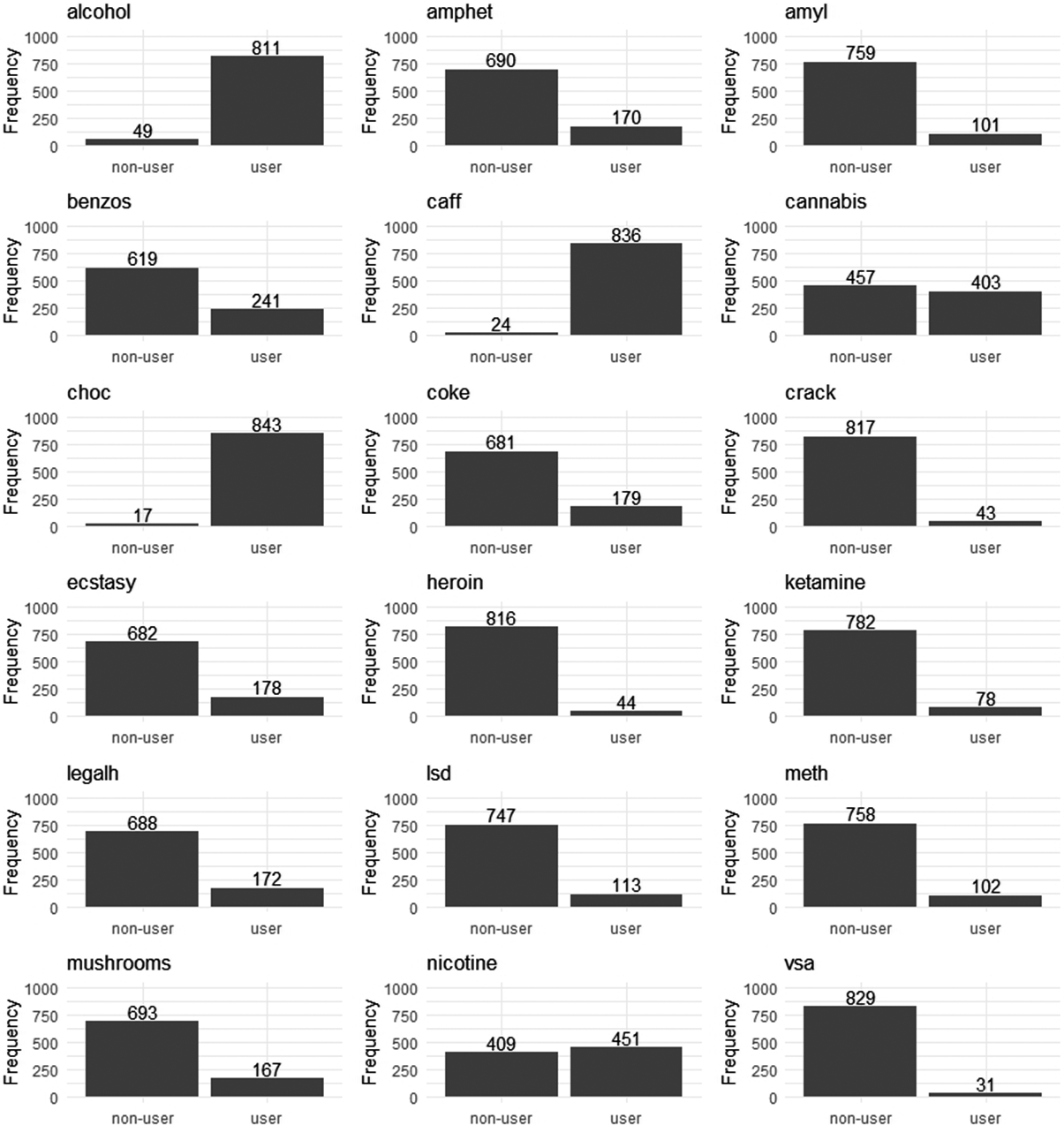

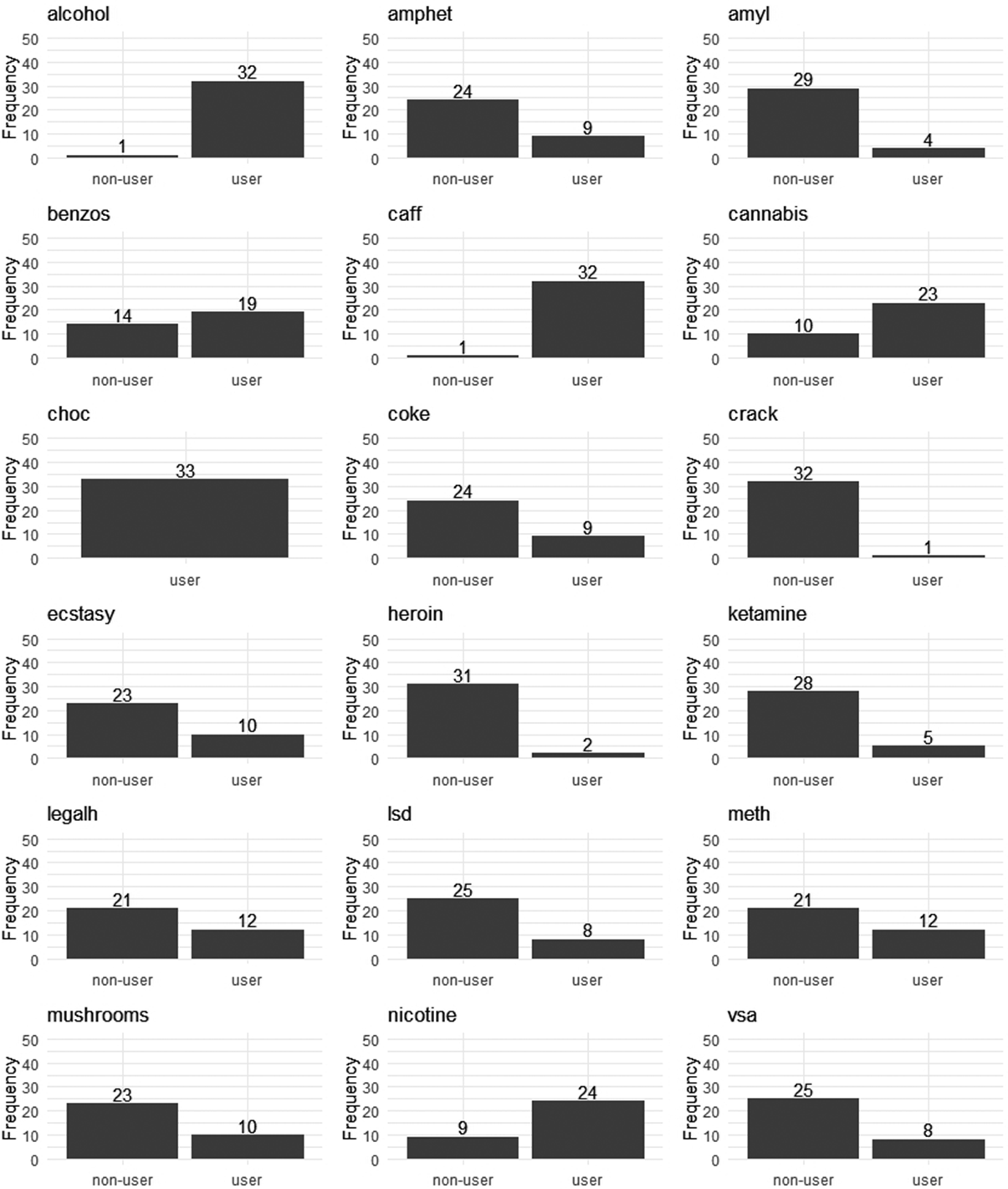

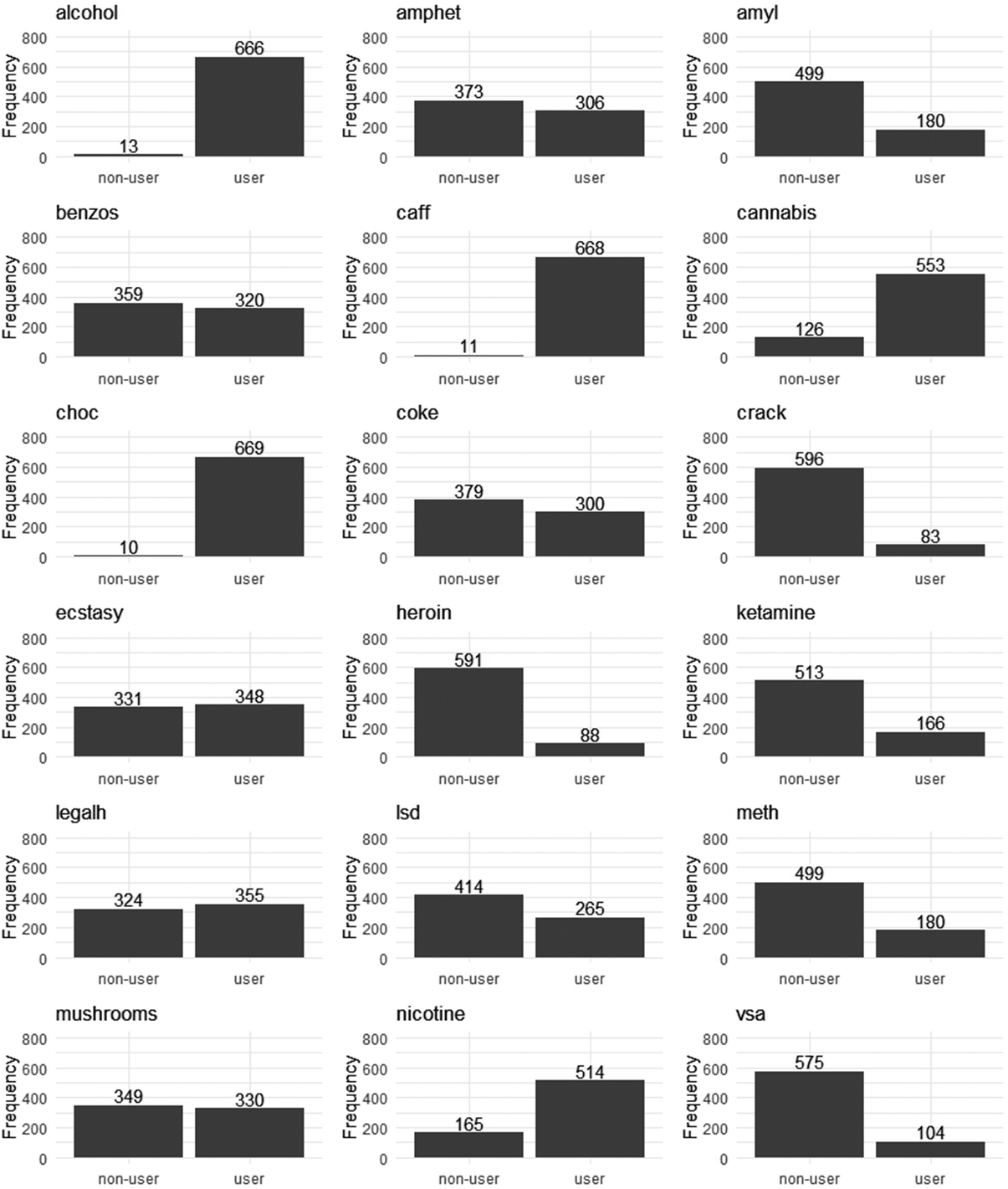

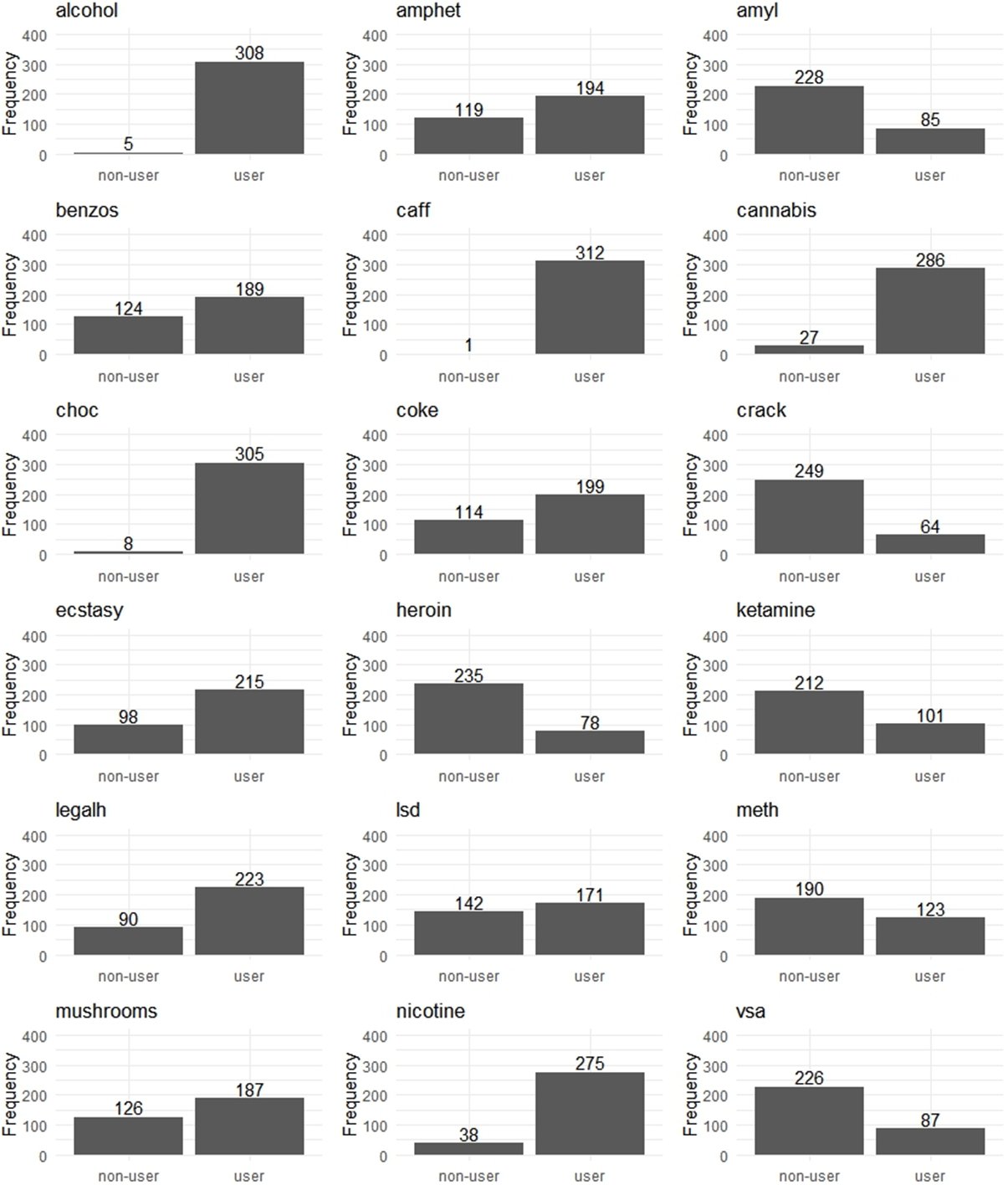

Recently, the neural network algorithm has been used to identify the heterogeneous causal directions. Thompson et al. (Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024) built a covariate-based feature space into a neural network to recognize heterogeneous DAGs with reframing the DAG structure learning problem as a continuous optimization problem. They added a projection layer to ensure the acyclic characterization of the causal graph structure (Bello et al., Reference Bello, Aragam and Ravikumar2022). Unlike Ni et al. (Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019), the neural network algorithm can directly learn node order from data, needing no prior assumptions. Using the neural network algorithm, Thompson et al. (Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024) studied the DAG differences of 18 recreational drug use scenarios under low- and high-scoring conditions of neuroticism and sensation-seeking.

2.3 Recursive Partitioning Method

The recursive partitioning method, also known as the tree model, is a data-driven tool for identifying differential variable relationships and how covariates influence them (Strobl et al., Reference Strobl, Malley and Tutz2009). These differential relationships include heterogeneous causal relationships (e.g., Athey & Imbens, Reference Athey and Imbens2016; Hill, Reference Hill2011) and broader variable correlations differing under various covariates, i.e., the interaction terms of variables and covariates (Zeileis et al., Reference Zeileis, Hothorn and Hornik2008). The recursive partitioning method used hierarchical if-then rules to partition samples into categories, forming a tree structure

![]() $\mathcal{T}$

(Breiman et al., Reference Breiman, Friedman, Olshen and Stone1984). These rules are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, automatically generated by learning algorithms. In practice, researchers form the if-then rules based on their optimization procedure to split the values of covariates.

$\mathcal{T}$

(Breiman et al., Reference Breiman, Friedman, Olshen and Stone1984). These rules are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, automatically generated by learning algorithms. In practice, researchers form the if-then rules based on their optimization procedure to split the values of covariates.

The tree-nodes Footnote 2 are employed for representing heterogeneous variable relationships in the recursive partitioning method, including the root-node, internal-nodes, and leaf-nodes. The if-then rules form paths from the root-node to leaf-nodes, with internal-nodes representing rule conditions and leaf nodes indicating classification results. It allows for rich variable information visualization. Figure 2 illustrates how the recursive partitioning method shows the impact of covariates on causal directions between variables. A key focus in tree model construction is selecting covariates and split points at specific tree-nodes. Current approaches include model-based partitioning (MOB; Zeileis et al., Reference Zeileis, Hothorn and Hornik2008) and CTree (Hothorn, Hornik, & Zeileis, Reference Hothorn, Hornik and Zeileis2006). MOB, a semiparametric method, assumes variables follow different probability distributions (often Gaussian) under different covariate conditions and uses log-likelihood functions to determine split points. CTree, a nonparametric recursive partitioning method, employs permutation test (Hothorn, Hornik, van de Wiel, et al., Reference Hothorn, Hornik, van de Wiel and Zeileis2006; Strasser & Weber, Reference Strasser and Weber1999) to catch the statistics capturing relationships between variables and covariates.

The recursive partitioning method has been utilized for identifying heterogeneous variable relationships. These models are applied to explore and explain the parameterization differences with the combination of some psychological statistics and measurement models, such as structural equation model (Brandmaier et al., Reference Brandmaier, von Oertzen, McArdle and Lindenberger2013; Kiefer et al., Reference Kiefer, Lemmerich, Langenberg, Mayer and Steinley2024), network analysis model (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020), and generalized linear mixed model (Fokkema et al., Reference Fokkema, Smits, Zeileis, Hothorn and Kelderman2018; Fokkema & Zeileis, Reference Fokkema and Zeileis2024). In causal inference research, methods like Bayesian additive regression trees (BART, Chipman et al., Reference Chipman, George and McCulloch2010; Hill, Reference Hill2011) and causal trees (Athey & Imbens, Reference Athey and Imbens2016) also highlight the importance of recursive partitioning method in calculating heterogeneous treatment effects.

To get more interpretable heterogeneous causal direction identification results, some researchers have applied the recursive partitioning method to identify causal direction heterogeneity in two variable cases (Li & Wiedermann, Reference Li and Wiedermann2020; van Wie et al., Reference van Wie, Li and Wiedermann2019; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). These studies mainly use the DDA to identify causal directions between variables. The DDA approach identifies the causal direction between two non-Gaussian variables by exploiting the higher-order moments of the predictor and the residuals of the causally competing models (Chen & Chan, Reference Chen and Chan2013; Wiedermann, Reference Wiedermann2018, Reference Wiedermann2022), or the independence properties between predictor and residual (Shi et al., Reference Shi, Fairchild and Wiedermann2023; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). When combined with recursive partitioning, DDA can leverage covariate information to distinguish a direct causal link (

![]() $X\to Y$

) from an unmeasured-confounder structure (

$X\to Y$

) from an unmeasured-confounder structure (

![]() $X\leftarrow Confounders\to Y$

) (van Wie et al., Reference van Wie, Li and Wiedermann2019), or to pinpoint the specific causal direction in heterogeneous subgroups (

$X\leftarrow Confounders\to Y$

) (van Wie et al., Reference van Wie, Li and Wiedermann2019), or to pinpoint the specific causal direction in heterogeneous subgroups (

![]() $X\to Y$

vs.

$X\to Y$

vs.

![]() $X\leftarrow Y$

) (Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). Using tree-based models, Wiedermann and colleagues further examined the heterogeneous causal directions between analog magnitude code and auditory verbal code.

$X\leftarrow Y$

) (Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). Using tree-based models, Wiedermann and colleagues further examined the heterogeneous causal directions between analog magnitude code and auditory verbal code.

2.4 Summary

The use of causal-discovery methods to explore and identify causal relationships—especially causal direction—has attracted growing attention (Glymour et al., Reference Glymour, Zhang and Spirtes2019; Vowels, Reference Vowels2025; Zanga et al., Reference Zanga, Ozkirimli and Stella2022). Recent studies increasingly emphasize heterogeneous causal directions and examine how covariate values shape these directions, leading to a family of methods that account for such heterogeneity. Yet these approaches suffer from two major limitations. First, although they can detect heterogeneous causal directions, they rarely scrutinize how participants are partitioned; this oversight can foster misinterpretation. As illustrated in Figure 2, the causal direction between two variables may conflict across conditions. Pooling participants without acknowledging these differences risks implying a cyclic relationship, thereby violating the acyclicity assumption of DAGs. Second, most existing methods focus solely on identifying causal directions and provide little insight into why heterogeneity arises—that is, under which covariate configurations a specific causal direction emerges. For example, the BGR requires a general directed acyclic graph to identify the influence of covariates on causal relationships, and its predictive effectiveness largely depends on whether the general DAG can reflect all possible variable relationships. The BN-LTE method needs to aggregate information from multiple covariates to identify heterogeneous DAGs and has difficulty isolating the impact of an individual covariate. Neural network methods can effectively identify changes in DAGs with multiple covariates but still rely on researchers’ subjective judgment to determine the heterogeneity of causal directions. Nowadays, the recursive partitioning method offers an effective way to identify the influence of covariates on heterogeneous causal directions (Li & Wiedermann, Reference Li and Wiedermann2020; van Wie et al., Reference van Wie, Li and Wiedermann2019; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024); however, it has not been applied to the identification and explanation of heterogeneous DAGs among multiple variables.

3 Linking causal discovery with recursive partitioning

In this section, we elaborate our conceptualization of heterogeneous causal directions and present a corresponding solution. Considering the SELF’s demonstrated capacity to integrate global- and local-view perspectives into a deterministic and statistically robust causal-discovery result (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018), we adopt it as a benchmark causal-discovery method and embed it within a recursive partitioning framework to produce an interpretable model of heterogeneous causal directions. As SELF is a nonparametric method, we specifically employ the conditional inference tree (Hothorn, Hornik, & Zeileis, Reference Hothorn, Hornik and Zeileis2006) to couple causal discovery with recursive partitioning, thereby explaining how to identify heterogeneous DAGs and, crucially, how to interpret their origins. Our exposition proceeds in two stages. First, we outline the theoretical underpinnings of heterogeneous causal directions by focusing on what we term the “bidirectional relationship” among variables, thereby clarifying how such heterogeneity can be understood at an aggregate level. Second, we detail the construction of the SELF-Tree model—an integrative framework that combines SELF with CTree—to operationalize our approach to detecting and explaining heterogeneous causal directions.

3.1 Conceptual illustration

Our understanding of heterogeneous causal directions is rooted in an explanation of the “chicken-or-egg” relationship—also framed as bidirectional or seemingly cyclical causation—of variables. In the formal frameworks of causal inference and causal discovery, acyclicity is a cornerstone assumption that guarantees model identifiability. Empirical reality, however, abounds with examples of mutual reinforcement between two constructs (e.g., Lu et al., Reference Lu, Liu, Liao and Wang2020; Nohe et al., Reference Nohe, Meier, Sonntag, Michel and Chen2015). In large-scale cross-sectional surveys, the likelihood that any variable pair exhibits a chicken-or-egg pattern increases rapidly as more variables are included. Traditional causal-discovery algorithms, designed for strictly unidirectional and acyclic relations, struggle to accommodate such reciprocity.

Time-series designs can disentangle reciprocal effects:

![]() $X$

at

$X$

at

![]() $time=t$

may influence

$time=t$

may influence

![]() $Y$

at

$Y$

at

![]() $time=t+1$

, while

$time=t+1$

, while

![]() $Y$

at

$Y$

at

![]() $time=t$

simultaneously influences

$time=t$

simultaneously influences

![]() $X$

at

$X$

at

![]() $time=t+1$

(Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Madras, Zemel and Welling2022). Yet most current causal-discovery techniques remain focused on cross-sectional data (e.g., Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018; Janzing et al., Reference Janzing, Mooij, Zhang, Lemeire, Zscheischler, Daniušis, Steudel and Schölkopf2012; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Hoyer, Hyvärimen and Kerminen2006; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). We therefore propose an alternative lens: any single time-point data set is a mixture of distinct participant subpopulations, each characterized by its own causal direction between the variables. When these subgroup differences are ignored, the aggregate pattern misleadingly appears as a chicken-or-egg loop.

$time=t+1$

(Löwe et al., Reference Löwe, Madras, Zemel and Welling2022). Yet most current causal-discovery techniques remain focused on cross-sectional data (e.g., Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018; Janzing et al., Reference Janzing, Mooij, Zhang, Lemeire, Zscheischler, Daniušis, Steudel and Schölkopf2012; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Hoyer, Hyvärimen and Kerminen2006; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024). We therefore propose an alternative lens: any single time-point data set is a mixture of distinct participant subpopulations, each characterized by its own causal direction between the variables. When these subgroup differences are ignored, the aggregate pattern misleadingly appears as a chicken-or-egg loop.

Viewing the problem through heterogeneous causal directions can resolve this paradox, even if the conclusion is counter-intuitive. Consider the relationship between social reality and stereotypes. Early work argued that stereotypes arise endogenously from people’s perceptions of real group characteristics (Ford & Stangor, Reference Ford and Stangor1992). Conversely, stereotypes can also be shaped by exogenous cues such as social categorization and meaning categories, subsequently creating a discriminatory social reality. Leveraging the recent popularity of Western astrological signs in China, Lu et al. (Reference Lu, Liu, Liao and Wang2020) showed that the stereotype “Virgos are disagreeable—compulsive and nit-picking” generated a real social pattern of avoiding Virgos as colleagues or friends. In other words, the causal arrow between social reality and stereotypes flips depending on contextual covariates such as geographic origin, sampling time, or community setting. Where stereotypes originate, social reality → stereotypes; where they merely spread, social categories → stereotypes → social reality.

We regard this perspective not as a refutation but as a complement to the concept of reciprocal causation. Reciprocal accounts posit that

![]() $X$

influences

$X$

influences

![]() $Y$

and

$Y$

and

![]() $Y$

subsequently influences

$Y$

subsequently influences

![]() $X$

, a sequence that can be traced across multiple time points. We concur, with one caveat: at any single moment, the causal relation is unidirectional: either

$X$

, a sequence that can be traced across multiple time points. We concur, with one caveat: at any single moment, the causal relation is unidirectional: either

![]() $X\to Y$

or

$X\to Y$

or

![]() $Y\to X$

, never both simultaneously. As Morgan and Winship (Reference Morgan and Winship2014) emphasize, reciprocity does not imply simultaneous cause and effect; rather, the data at hand lack the temporal resolution to disentangle the sequence. Participants in a cross-sectional sample may be distributed across different stages of the same process. Whether they currently occupy the path social reality → stereotypes or stereotypes → social reality depends on covariate-defined subgroups.

$Y\to X$

, never both simultaneously. As Morgan and Winship (Reference Morgan and Winship2014) emphasize, reciprocity does not imply simultaneous cause and effect; rather, the data at hand lack the temporal resolution to disentangle the sequence. Participants in a cross-sectional sample may be distributed across different stages of the same process. Whether they currently occupy the path social reality → stereotypes or stereotypes → social reality depends on covariate-defined subgroups.

Moreover, ignoring this heterogeneity compromises accuracy. Ni et al. (Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019) demonstrated that a single DAG fitted to the full sample failed to capture subgroup-specific causal directions. Representing all subpopulations with one graph is therefore inadequate. Although longitudinal data would provide the clearest temporal ordering, cross-sectional data can still be salvaged: by partitioning participants on key covariates and estimating separate causal directions within each subgroup, we can both identify and explain heterogeneous causal structures. This insight reframes every cross-sectional causal-discovery study: whenever chicken-or-egg ambiguity arises, incorporating covariate information to delineate subpopulations offers a viable route to valid and interpretable causal inference.

3.2 The SELF-Tree model

We propose SELF-Tree, an interpretable algorithm for identifying heterogeneous causal directions. By integrating the strengths of the structural equation likelihood function—which accurately determines causal directions among multiple variables—and the CTree model. SELF-Tree both detects and explains multivariate causal heterogeneity. SELF incorporates noise-term information, thereby circumventing the MEC indeterminacy common to traditional approaches (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Du, Yang and Li2022). Because SELF is nonparametric, we pair it with the nonparametric CTree model in the partitioning stage (Hothorn, Hornik, van de Wiel, et al., Reference Hothorn, Hornik, van de Wiel and Zeileis2006; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020).

Let

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $q$

be the number of variables that constitute the causal DAG and covariates that may produce heterogeneous causal directions, respectively, denoted as

$q$

be the number of variables that constitute the causal DAG and covariates that may produce heterogeneous causal directions, respectively, denoted as

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}={\left({X}_1,\dots, {X}_p\right)}^T$

and

$\boldsymbol{X}={\left({X}_1,\dots, {X}_p\right)}^T$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{Z}={\left({Z}_1,\dots, {Z}_q\right)}^T$

. The study proposes a “two-step” approach for SELF-Tree.

$\boldsymbol{Z}={\left({Z}_1,\dots, {Z}_q\right)}^T$

. The study proposes a “two-step” approach for SELF-Tree.

Step 1: Using the CTree method to determine the tree structure

![]() $\mathcal{T}$

;

$\mathcal{T}$

;

Step 2: Constructs the SELF models for each leaf-node data to identify the causal direction among multiple variables, yielding a covariate-specific DAG

![]() $\mathcal{G}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}\right)$

together with its corresponding structure function

$\mathcal{G}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}\right)$

together with its corresponding structure function

![]() $\mathcal{F}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}\right)$

.

$\mathcal{F}\left(\boldsymbol{Z}\right)$

.

Following the above steps, the final output is a tuple

![]() $\left\langle \mathcal{T},\mathcal{G},\mathcal{F}\right\rangle$

. In our design, the variables

$\left\langle \mathcal{T},\mathcal{G},\mathcal{F}\right\rangle$

. In our design, the variables

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

and covariates

$\boldsymbol{X}$

and covariates

![]() $\boldsymbol{Z}$

are prespecified by the researcher. Crucially, the covariates

$\boldsymbol{Z}$

are prespecified by the researcher. Crucially, the covariates

![]() $\boldsymbol{Z}$

are used solely for partitioning via CTree and never appear as nodes in the DAG; conversely, the variables

$\boldsymbol{Z}$

are used solely for partitioning via CTree and never appear as nodes in the DAG; conversely, the variables

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

are employed exclusively to construct the DAG and play no role in the partitioning step. There is a detailed exposition of the CTree and SELF algorithms respectively at the following parts.

$\boldsymbol{X}$

are employed exclusively to construct the DAG and play no role in the partitioning step. There is a detailed exposition of the CTree and SELF algorithms respectively at the following parts.

The CTree method employs permutation test to select the covariate

![]() ${Z}_j\;\left(1\le j\le q\right)$

at each tree-node that best explains heterogeneity. Following the network-tree framework proposed by Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020), we choose one covariate

${Z}_j\;\left(1\le j\le q\right)$

at each tree-node that best explains heterogeneity. Following the network-tree framework proposed by Jones et al. (Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020), we choose one covariate

![]() ${Z}_j$

at the current node and determine its optimal split point. Once the candidate covariate

${Z}_j$

at the current node and determine its optimal split point. Once the candidate covariate

![]() ${Z}_j$

is fixed for a given node, we construct a test statistic that quantifies the association between the variables

${Z}_j$

is fixed for a given node, we construct a test statistic that quantifies the association between the variables

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

and the covariate

$\boldsymbol{X}$

and the covariate

![]() ${Z}_j$

as follows:

${Z}_j$

as follows:

$$\begin{align}{\mathbf{T}}_j=\mathrm{vec}\left(\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n^{\ast }}g\left({Z}_{ij}\right)h{\left({\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}\right)}^T\right)\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\mathbf{T}}_j=\mathrm{vec}\left(\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n^{\ast }}g\left({Z}_{ij}\right)h{\left({\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}\right)}^T\right)\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${n}^{\ast }$

is the number of participants in the tree-node,

${n}^{\ast }$

is the number of participants in the tree-node,

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

refers to the

${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

refers to the

![]() $p$

-dimensional vector of standardized observations for

$p$

-dimensional vector of standardized observations for

![]() $i$

th participant at the current tree-node, the

$i$

th participant at the current tree-node, the

![]() $g\left(\cdotp \right)$

and

$g\left(\cdotp \right)$

and

![]() $h\left(\cdotp \right)$

are the transformation function for the covariate

$h\left(\cdotp \right)$

are the transformation function for the covariate

![]() ${Z}_j$

and

${Z}_j$

and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

respectively. The transformation functions capture how

${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

respectively. The transformation functions capture how

![]() ${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

changes with

${\boldsymbol{X}}_{\boldsymbol{i}\cdotp}^{\ast}$

changes with

![]() ${Z}_j$

. If

${Z}_j$

. If

![]() ${Z}_j$

is numeric or ordinal, the

${Z}_j$

is numeric or ordinal, the

![]() $g\left(\cdotp \right)$

is simply a scalar function; if

$g\left(\cdotp \right)$

is simply a scalar function; if

![]() ${Z}_j$

is nominal, a dummy covariate is created for each category, yielding a vector-valued

${Z}_j$

is nominal, a dummy covariate is created for each category, yielding a vector-valued

![]() $g\left({Z}_j\right)$

. The

$g\left({Z}_j\right)$

. The

![]() $h\left(\cdotp \right)$

is also called the influence function, which indicates the contribution of individual observations to the correlation between two variables. It can be expressed as

$h\left(\cdotp \right)$

is also called the influence function, which indicates the contribution of individual observations to the correlation between two variables. It can be expressed as

which only include the cross-products of the correlation. The means

![]() ${X}_{i1}^{\ast },\dots, {X}_{ip}^{\ast }$

and the squared standardized elements

${X}_{i1}^{\ast },\dots, {X}_{ip}^{\ast }$

and the squared standardized elements

![]() ${X_{i1}^{\ast}}^2,\dots, {X_{ip}^{\ast}}^2$

can also be added in the influence function (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020).

${X_{i1}^{\ast}}^2,\dots, {X_{ip}^{\ast}}^2$

can also be added in the influence function (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mair, Simon and Zeileis2020).

We apply the SELF model within each leaf-node to determine the causal directions among the variables. SELF assumes an additive-noise representation of the causal structure (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018):

where

![]() $P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

denotes the parent set of

$P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

denotes the parent set of

![]() ${X}_j$

in

${X}_j$

in

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

,

$\mathcal{G}$

,

![]() ${F}_j\left(\cdotp \right)$

represents the structural equation, and

${F}_j\left(\cdotp \right)$

represents the structural equation, and

![]() ${E}_j$

represents the random noise term independent of

${E}_j$

represents the random noise term independent of

![]() $P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. The error term

$P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. The error term

![]() ${E}_j$

is statistically independent of all variables

${E}_j$

is statistically independent of all variables

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

and other noise component. SELF requires that at least one of

$\boldsymbol{X}$

and other noise component. SELF requires that at least one of

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

or the noise vector

$\boldsymbol{X}$

or the noise vector

![]() $E={\left({E}_1,\dots, {E}_p\right)}^T$

exhibits distributional asymmetry (Janzing et al., Reference Janzing, Mooij, Zhang, Lemeire, Zscheischler, Daniušis, Steudel and Schölkopf2012; Li & Wiedermann, Reference Li and Wiedermann2020; Vowels, Reference Vowels2025; Wiedermann, Reference Wiedermann2022; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024), i.e., the relations among variables are nonlinear or the variables and the errors follow non-Gaussian distributions. Under linearity, the model simplifies to

$E={\left({E}_1,\dots, {E}_p\right)}^T$

exhibits distributional asymmetry (Janzing et al., Reference Janzing, Mooij, Zhang, Lemeire, Zscheischler, Daniušis, Steudel and Schölkopf2012; Li & Wiedermann, Reference Li and Wiedermann2020; Vowels, Reference Vowels2025; Wiedermann, Reference Wiedermann2022; Wiedermann et al., Reference Wiedermann, Zhang and Shi2024), i.e., the relations among variables are nonlinear or the variables and the errors follow non-Gaussian distributions. Under linearity, the model simplifies to

$$\begin{align}{X}_j=\sum \limits_{i=1}^p{b}_{ij}{X}_i+{E}_j\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{X}_j=\sum \limits_{i=1}^p{b}_{ij}{X}_i+{E}_j\end{align}$$

with

![]() ${b}_{ij}$

representing the causal effect of

${b}_{ij}$

representing the causal effect of

![]() ${X}_i$

on

${X}_i$

on

![]() ${X}_j$

,

${X}_j$

,

![]() ${b}_{ij}=0$

when

${b}_{ij}=0$

when

![]() $i\notin P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. Note that under linearity and additive noise condition, at least one variable or error term must follow a non-Gaussian distribution. Let

$i\notin P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. Note that under linearity and additive noise condition, at least one variable or error term must follow a non-Gaussian distribution. Let

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

collect all

$\mathcal{F}$

collect all

![]() ${F}_j\left(\cdotp \right)$

, and write

${F}_j\left(\cdotp \right)$

, and write

![]() $\mathcal{S}=<\mathcal{G},\mathcal{F}>.$

Then the likelihood function over the variables by Equation (1) is

$\mathcal{S}=<\mathcal{G},\mathcal{F}>.$

Then the likelihood function over the variables by Equation (1) is

$$\begin{align}\mathcal{L}(S)&=\sum \limits_{j=1}^p\log \left(\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j=x|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right\}\right)\right)\nonumber\\& =\sum \limits_{j=1}^p\sum \limits_{n=1}^N\log \left(\Pr \left({E}_j=x-{F}_j\left(P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right)\right)\right)\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\mathcal{L}(S)&=\sum \limits_{j=1}^p\log \left(\mathit{\Pr}\left({X}_j=x|\left\{{X}_i:i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right\}\right)\right)\nonumber\\& =\sum \limits_{j=1}^p\sum \limits_{n=1}^N\log \left(\Pr \left({E}_j=x-{F}_j\left(P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)\right)\right)\right)\end{align}$$

The SELF model maximizes a likelihood function constructed over the noise terms to obtain a globally optimal DAG while simultaneously ensuring the local statistical independence between the noise and the observed variables (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018). The model places no restrictions on the data type—continuous or discrete—or on the functional form—linear or nonlinear—of the causal relationships. The DAG structure itself is estimated via a hill-climbing–based causal-structure search algorithm (Tsamardinos et al., Reference Tsamardinos, Brown and Aliferis2006). The following theorems about the SELF model are established (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018):

-

1. For observed data of

$\boldsymbol{X}$

generated by causal structure

$\boldsymbol{X}$

generated by causal structure

$S$

, the likelihood function satisfies

$S$

, the likelihood function satisfies

$\mathcal{L}(S)\ge \mathcal{L}\left(S^{\prime}\right)$

for any other causal structure

$\mathcal{L}(S)\ge \mathcal{L}\left(S^{\prime}\right)$

for any other causal structure

$S^{\prime }$

.

$S^{\prime }$

. -

2. Under the assumption of independent and identically distributed observations, maximizing

$\mathcal{L}(S)$

is equivalent to minimizing the sum of entropies

$\mathcal{L}(S)$

is equivalent to minimizing the sum of entropies

${\sum}_{j=1}^pH\left({E}_j|S\right)$

, where

${\sum}_{j=1}^pH\left({E}_j|S\right)$

, where

$H\left(\cdotp \right)$

denotes entropy. And if the correct parent nodes reduce entropy more than nonparental nodes, then the causal structure

$H\left(\cdotp \right)$

denotes entropy. And if the correct parent nodes reduce entropy more than nonparental nodes, then the causal structure

$S$

that minimizes the entropy is the correct one.

$S$

that minimizes the entropy is the correct one.

By integrating the CTree and SELF frameworks, we obtain a procedure that identifies multivariate heterogeneous causal directions while explicitly accounting for covariate influences. For the SELF-Tree model to be valid, the following assumptions must hold:

Assumption 1. There exist distinct subpopulations whose causal directions among the variables are heterogeneous, and these subpopulations can be distinguished by the available covariates.

Assumption 2. The set of covariates is complete—i.e., all sources of heterogeneity are captured by the observed covariates.

Assumption 3. The covariates influence only the direction of the causal relations among the variables, not the variables’ values; thus, the DAG itself contains only the variables of interest.

Assumption 4. The variables and error terms exhibit distributional asymmetry, i.e., either nonlinear relationships among variables or non-Gaussian distributions of variables and noise.

Assumption 5. Within each leaf node obtained after conditioning on covariates, the data satisfy the causal sufficiency, the causal Markov property, and causal faithfulness; consequently, all observations in the same leaf share an identical causal direction, and the data are independent identically distributed. Across leaves, the estimated DAG structures may differ markedly.

In addition to the core assumptions outlined above, several auxiliary conditions are imposed to safeguard the validity of the SELF-Tree procedure: (i) all variables and covariates are free of measurement error (Gische & Voelkle, Reference Gische and Voelkle2022; Wiedermann, Reference Wiedermann2022); (ii) no interference, i.e., the response of any unit is unaffected by the treatment assignment of other units (Rubin, Reference Rubin2005; Shin, Reference Shin2012); and (iii) the covariates are mutually independent (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Stingo and Baladandayuthapani2019; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Bonilla and Kohn2024). These restrictions preclude extraneous sources of bias and ensure that the identification performance of the SELF-Tree model is not confounded by additional error structures.

4 Simulation

4.1 Settings

We first evaluate the performance of SELF-Tree via simulation, focusing on (a) its ability to select relevant covariates and (b) its accuracy in recovering heterogeneous DAGs. Five factors are systematically manipulated:

1. Number of variables (

![]() $p$

) in the true DAG.

$p$

) in the true DAG.

2. Sample size (

![]() $N$

).

$N$

).

3. Strength of causal relations, indexed by average indegree.

4. Mode of heterogeneity—i.e., how covariates shift causal directions.

5. Presence of spurious covariates.

For the first three factors, we set

![]() $N\in \left\{500,1000,2000,4000\right\}$

and

$N\in \left\{500,1000,2000,4000\right\}$

and

![]() $p\in \left\{6,10,15\right\}$

following Cai et al. (Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018). The average indegree (AvgInd)—the mean number of incoming edges per node—captures inter-variable connectivity (Bloznelis, Reference Bloznelis2010). We vary

$p\in \left\{6,10,15\right\}$

following Cai et al. (Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018). The average indegree (AvgInd)—the mean number of incoming edges per node—captures inter-variable connectivity (Bloznelis, Reference Bloznelis2010). We vary

![]() $\mathrm{AvgInd}\in \left\{0.5,1.0,1.5,2.0,2.5\right\}$

; the lower bound

$\mathrm{AvgInd}\in \left\{0.5,1.0,1.5,2.0,2.5\right\}$

; the lower bound

![]() $p$

= 6 is chosen because 6 is the smallest number of variables that still permits a DAG when

$p$

= 6 is chosen because 6 is the smallest number of variables that still permits a DAG when

![]() $\mathrm{AvgInd}$

= 2.5. Two covariates drive heterogeneity with

$\mathrm{AvgInd}$

= 2.5. Two covariates drive heterogeneity with

![]() ${Z}_1\sim N\left(0,1\right)$

and

${Z}_1\sim N\left(0,1\right)$

and

![]() ${Z}_2\sim U\left(-3,3\right)$

. Both symmetric around 0. Two tree structures are examined as Figure 3 shows. The Moderate structure means that causal directions switch sharply at

${Z}_2\sim U\left(-3,3\right)$

. Both symmetric around 0. Two tree structures are examined as Figure 3 shows. The Moderate structure means that causal directions switch sharply at

![]() $Z=0$

, yielding balanced successor nodes. And the Extreme structure yielding the critical cut-point is at −1, producing highly unbalanced subsamples. Finally, two spurious covariates— and —are added to test whether redundant predictors degrade selection accuracy. All four covariates are mutually independent.

$Z=0$

, yielding balanced successor nodes. And the Extreme structure yielding the critical cut-point is at −1, producing highly unbalanced subsamples. Finally, two spurious covariates— and —are added to test whether redundant predictors degrade selection accuracy. All four covariates are mutually independent.

Figure 3 The tree structure in the simulation study. Note that the left is the Moderate structure, and the right is the Extreme structure. The percentage in each leaf node indicates the theoretical proportion of samples among all participants. The DAG1, DAG2, and DAG3 are used to label the causal graph structures under different conditions.

We use the SELF package (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018) to generate the true causal graph and its corresponding data. In code, a directed graph is encoded as an adjacency matrix of size

![]() $p\times p$

. The element

$p\times p$

. The element

![]() $\left(i,j\right)$

equals 1 if the edge

$\left(i,j\right)$

equals 1 if the edge

![]() ${X}_i\to {X}_j$

exists and 0 otherwise. The diagonal is necessarily 0. Owing to acyclicity, the matrix can always be written as an upper-triangular matrix. We therefore draw

${X}_i\to {X}_j$

exists and 0 otherwise. The diagonal is necessarily 0. Owing to acyclicity, the matrix can always be written as an upper-triangular matrix. We therefore draw

![]() $\left(p^{2}-p\right)/2$

independent Bernoulli variables to fill the strictly upper-triangular positions with success probability

$\left(p^{2}-p\right)/2$

independent Bernoulli variables to fill the strictly upper-triangular positions with success probability

![]() $2\times \mathrm{AvgInd}/\left(p-1\right)$

, which guarantees that the realized graph has an average indegree very close to the target value. A candidate matrix is accepted only if the total number of 1 s differs from

$2\times \mathrm{AvgInd}/\left(p-1\right)$

, which guarantees that the realized graph has an average indegree very close to the target value. A candidate matrix is accepted only if the total number of 1 s differs from

![]() $p\times AvgInd$

by no more than ±0.05. The accepted 1 s are then placed row-wise into the upper triangle to yield the true adjacency matrix. For data generation, we focus on linear non-Gaussian models, that is, the

$p\times AvgInd$

by no more than ±0.05. The accepted 1 s are then placed row-wise into the upper triangle to yield the true adjacency matrix. For data generation, we focus on linear non-Gaussian models, that is, the

![]() ${X}_j={\sum}_{i=1}^p{b}_{ij}{X}_i+{E}_j$

, the

${X}_j={\sum}_{i=1}^p{b}_{ij}{X}_i+{E}_j$

, the

![]() ${b}_{ij}=0$

when

${b}_{ij}=0$

when

![]() ${X}_i\notin P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. If the

${X}_i\notin P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

. If the

![]() $P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

is empty, we set

$P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

is empty, we set

![]() ${E}_j\sim N\left(0,1\right)$

. Otherwise, for every parent

${E}_j\sim N\left(0,1\right)$

. Otherwise, for every parent

![]() ${X}_i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

, we draw

${X}_i\in P{A}_{\mathcal{G}}\left({X}_j\right)$

, we draw

![]() ${b}_{ij}\sim U\left(-1,-0.5\right)\cup U\left(0.5,1\right)$

and

${b}_{ij}\sim U\left(-1,-0.5\right)\cup U\left(0.5,1\right)$

and

![]() ${E}_j$

to be a zero-mean noise with heavy tails and heteroskedastic variance Footnote 3

.

${E}_j$

to be a zero-mean noise with heavy tails and heteroskedastic variance Footnote 3

.

4.2 Evaluation methods

The evaluation of the SELF-Tree model is divided into two parts: the recognition result of the tree structure and evaluation effect of the heterogeneous DAGs. The tree structure recognition includes the identification of the tree-nodes, that is, whether the positions of

![]() ${Z}_1$

and

${Z}_1$

and

![]() ${Z}_2$

align with those in Figure 3 specifically using the CTree model, and the accuracy of the split point estimation about every covariate using

${Z}_2$

align with those in Figure 3 specifically using the CTree model, and the accuracy of the split point estimation about every covariate using

![]() $Bias=1/n\;{\sum}_i\left|{\widehat{z}}_i-{z}_i\right|$

, where

$Bias=1/n\;{\sum}_i\left|{\widehat{z}}_i-{z}_i\right|$

, where

![]() $n$

is the number of repetitions,

$n$

is the number of repetitions,

![]() ${z}_i$

is the true value of the split point in the simulation, and

${z}_i$

is the true value of the split point in the simulation, and

![]() ${\widehat{z}}_i$

is the estimated split point using the CTree method. A smaller bias value indicates a better estimation effect of the split point.

${\widehat{z}}_i$

is the estimated split point using the CTree method. A smaller bias value indicates a better estimation effect of the split point.

The evaluation of heterogeneous DAGs involves two aspects: the accuracy of the overall DAGs and the accuracy of directed edges in the DAGs. The overall accuracy of the DAGs is assessed using the structural Hamming distance (SHD) and the Frobenius norm (FNorm). SHD is the number of extra, missing, and reversed edges of the predicted directed acyclic graph

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

compared to the true graph

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

compared to the true graph

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

(Tsamardinos et al., Reference Tsamardinos, Brown and Aliferis2006). FNorm measures the difference between the adjacency matrices of

$\mathcal{G}$

(Tsamardinos et al., Reference Tsamardinos, Brown and Aliferis2006). FNorm measures the difference between the adjacency matrices of

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

and

$\mathcal{G}$

and

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

(Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Inazumi, Sogawa, Hyvärinen, Kawahara, Washio, Hoyer and Bollen2011). Smaller SHD and FNorm values indicate higher similarity between

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

(Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Inazumi, Sogawa, Hyvärinen, Kawahara, Washio, Hoyer and Bollen2011). Smaller SHD and FNorm values indicate higher similarity between

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

and

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

. The accuracy of directed edge identification is evaluated using the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Guo, Moraffah, Sheth, Candan and Liu2022). Let

$\mathcal{G}$

. The accuracy of directed edge identification is evaluated using the true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Guo, Moraffah, Sheth, Candan and Liu2022). Let

![]() ${E}_{\mathcal{G}}$

be the edges in

${E}_{\mathcal{G}}$

be the edges in

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

and

$\mathcal{G}$

and

![]() ${E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}$

be the edges predicted by

${E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}$

be the edges predicted by

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

, we have

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

, we have

$$\begin{align*}TPR=\sum \limits_i\frac{\#\left\{{e}_i|i\in {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\cap {E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}\right\}}{\#\left\{{E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}, FRP=\sum \limits_i\frac{\#\left\{{e}_i|i\in {E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}\backslash {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}{\#\left\{E\backslash {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}TPR=\sum \limits_i\frac{\#\left\{{e}_i|i\in {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\cap {E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}\right\}}{\#\left\{{E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}, FRP=\sum \limits_i\frac{\#\left\{{e}_i|i\in {E}_{\widehat{\mathcal{G}}}\backslash {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}{\#\left\{E\backslash {E}_{\mathcal{G}}\right\}}.\end{align*}$$

where

![]() $E$

represents all possible edges in the directed acyclic graph, and

$E$

represents all possible edges in the directed acyclic graph, and

![]() $\#\left\{\cdotp \right\}$

counts the nonzero elements. The TPR measures the proportion of correctly identified edges, while FPR measures the proportion of incorrectly identified edges. Higher TPR and lower FPR values indicate better alignment between

$\#\left\{\cdotp \right\}$

counts the nonzero elements. The TPR measures the proportion of correctly identified edges, while FPR measures the proportion of incorrectly identified edges. Higher TPR and lower FPR values indicate better alignment between

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

and

$\mathcal{G}$

and

![]() $\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

. All these heterogeneous DAGs evaluation methods are based on the correct tree-node identification result.

$\widehat{\mathcal{G}}$

. All these heterogeneous DAGs evaluation methods are based on the correct tree-node identification result.

4.3 Analysis procedure

This study uses the partykit package (Hothorn & Zeileis, Reference Hothorn and Zeileis2015) in R language 4.4.2 (R Core Team, 2024) for nonparametric recursive partitioning with CTree models. It enhances the SELF package (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Qiao, Zhang and Hao2018) for the structural equation likelihood framework method. The linear estimators and log-likelihood functions are employed to fit the SELF model.

4.4 Results

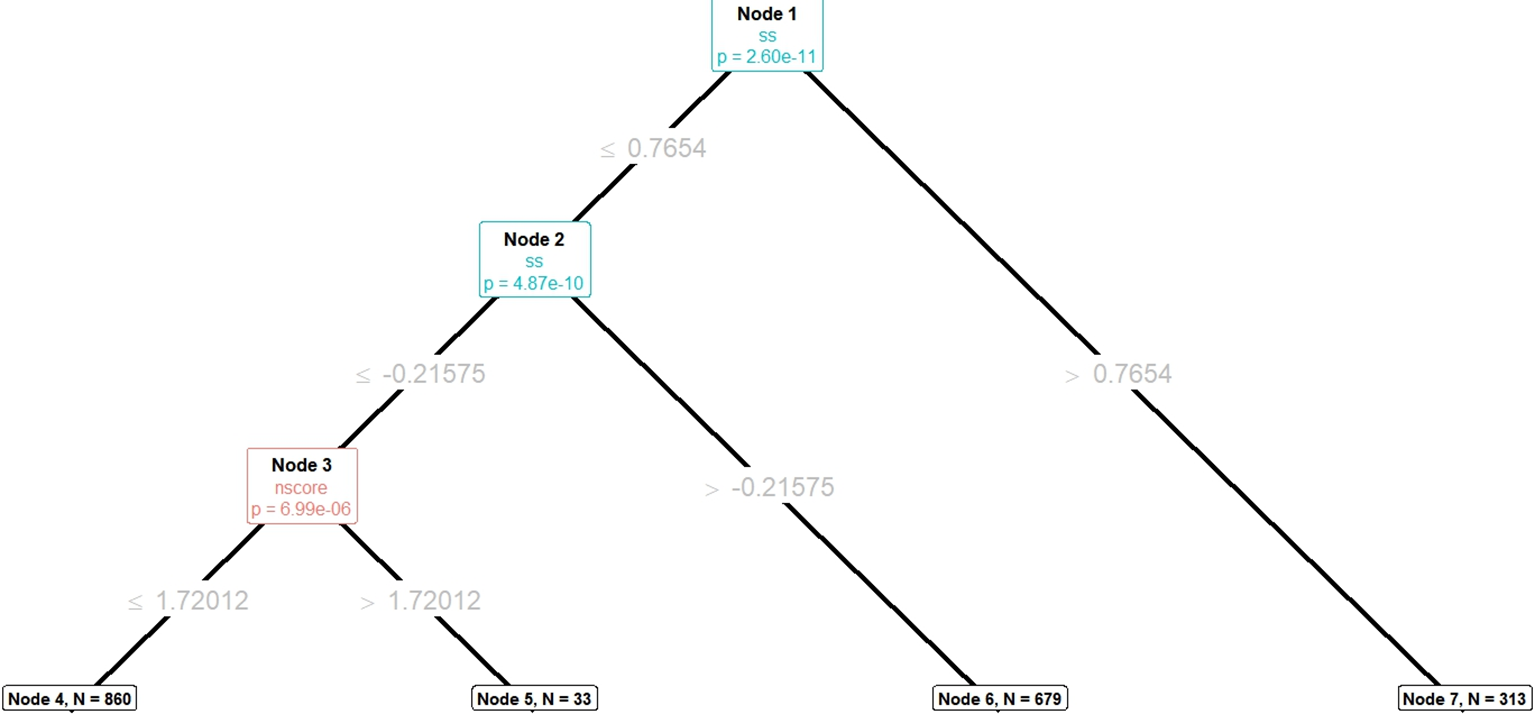

4.4.1 The identification result of tree structure

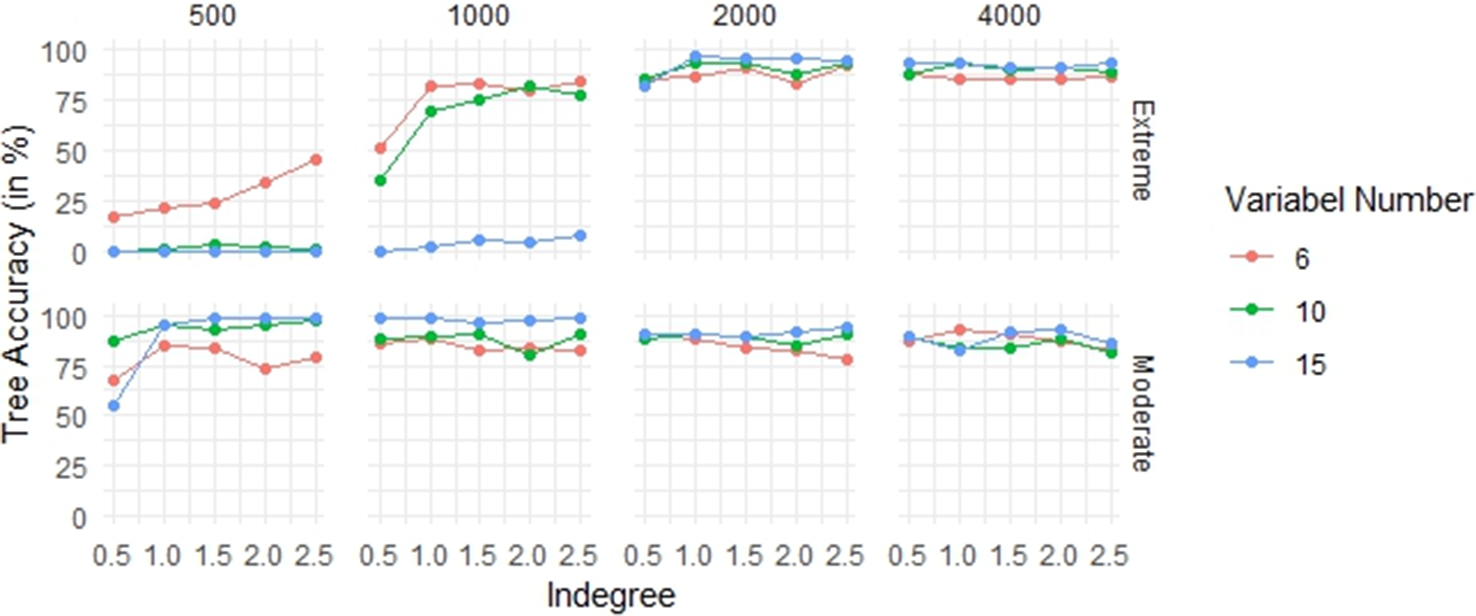

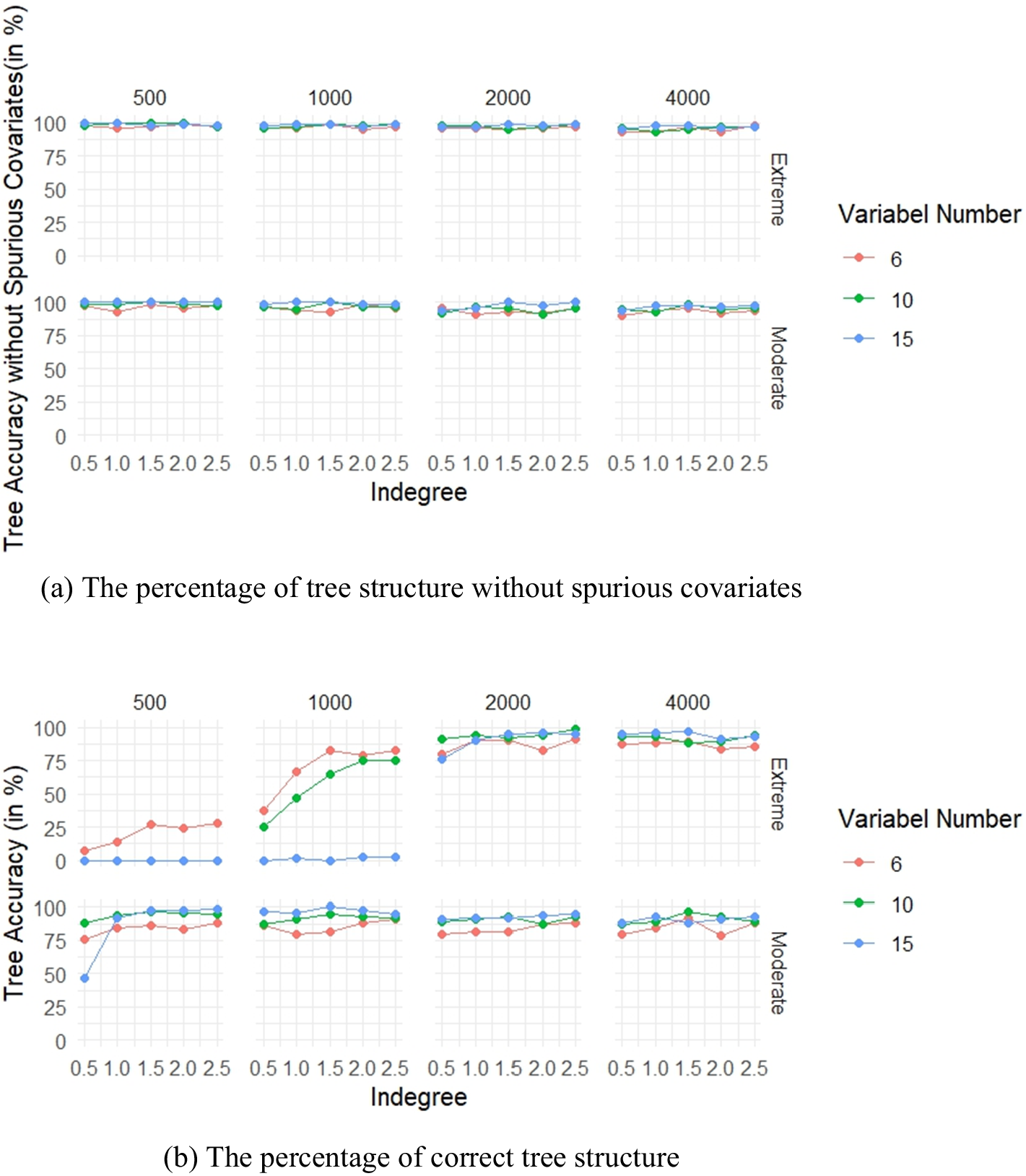

Figure 4 shows the accuracy of the tree-node identification under different conditions. In the Extreme structure, a sample size of over 2,000 can ensure a recognition accuracy of over 75%. The higher the indegree centrality of the DAGs, the better the accuracy of the tree-node identification. The impact of variables numbers on tree-node identification accuracy depends on the sample size: when the sample size is over 2,000, more variables can lead to better recognition, while fewer variables yield a better effect when the sample size is below 1,000. Notably, with a sample size of 500 and 15 variables (regardless of indegree centrality), and with a sample size of 1,000, an indegree centrality of 0.5, and 15 variables, the tree-nodes cannot be accurately identified with an Extreme tree structure. In the Moderate structure, except for a few cases, a recognition rate of over 80% can be generally ensured. Regardless of other conditions, an increase in the number of variables can improve the accuracy of tree-node identification.

Figure 4 The identification result of tree structure.

The relationship between sample size, indegree centrality, and tree structure recognition accuracy is more complex: when the number of variables is 6, increasing the sample size can improve the tree-node identification accuracy, while increasing the indegree centrality reduces it; while when the number of variables is more than 10, increasing the sample size worsens the identification result, and the impact of indegree centrality becomes more complicated.

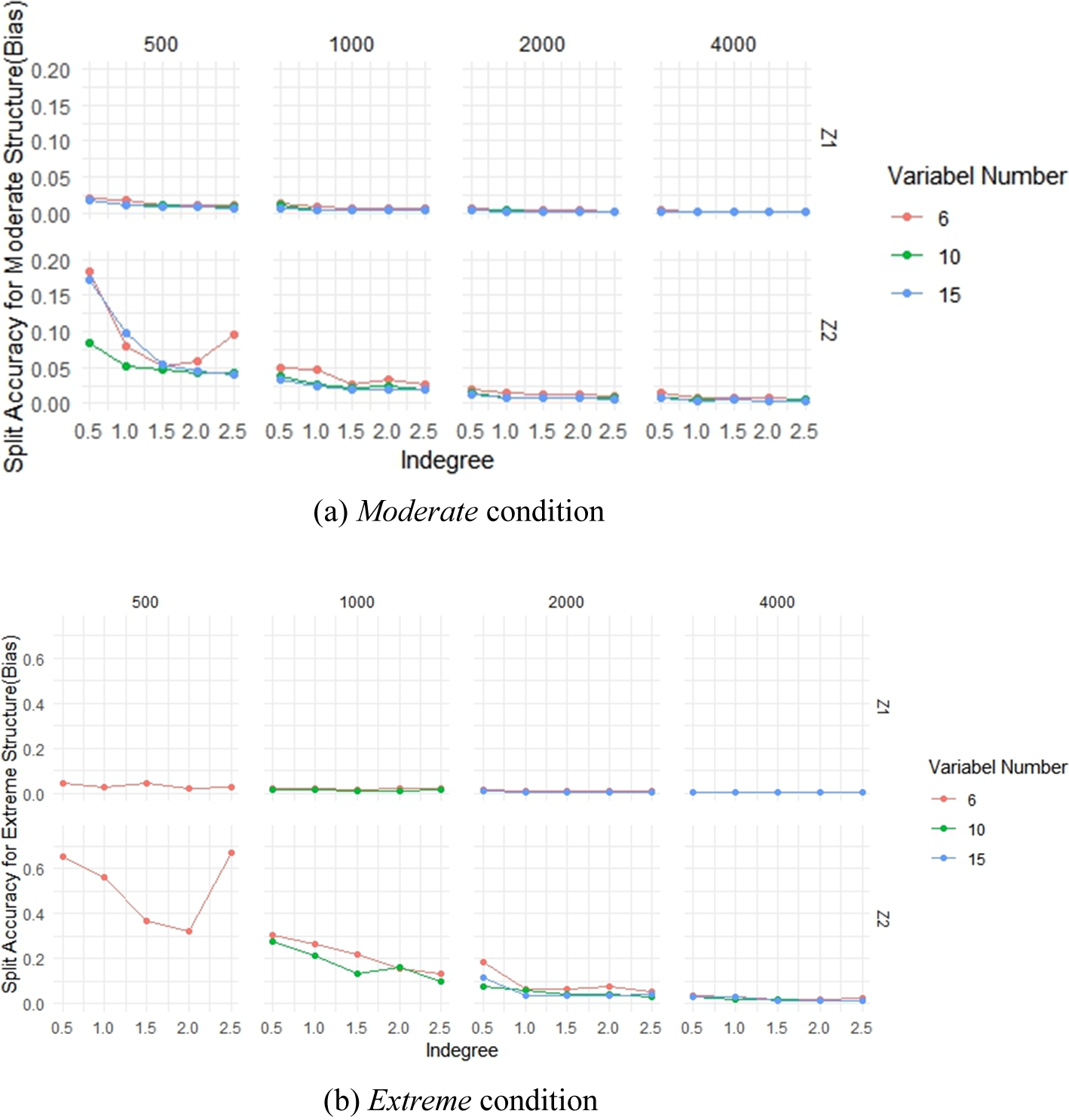

The results for the split point estimation of covariates are shown in Figure 5. The accuracy under the Moderate condition is significantly higher than the Extreme condition. The identification accuracy improves with increasing sample size and the number of variables. When the sample size is large (over 2,000), changes in indegree centrality do not significantly affect the split point identification accuracy. We also find that the identification accuracy for

![]() ${Z}_1$

(the covariate at the root node) is better than

${Z}_1$

(the covariate at the root node) is better than

![]() ${Z}_2$

, no matter what the tree structure is.

${Z}_2$

, no matter what the tree structure is.

Figure 5 The identification result of the split point of the covariates. Note that under the Extreme condition, the tree model structure may not be accurately identified when the sample size is 500 with 10 or 15 variables, or when the sample size is 1,000 with 15 variables. Therefore, the split point identification result under these conditions is not presented in this figure.

4.4.2 The identification result of heterogeneous DAGs

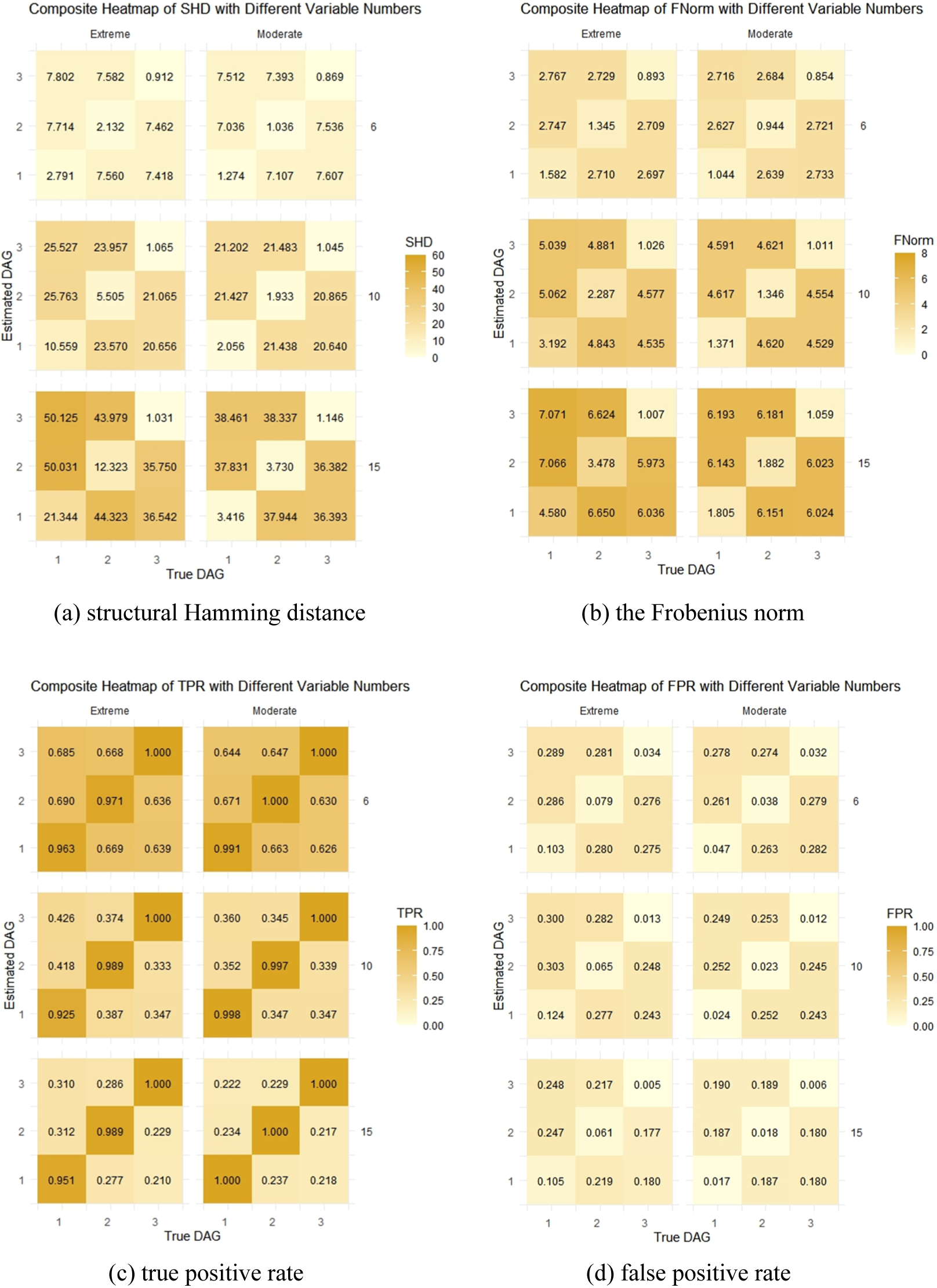

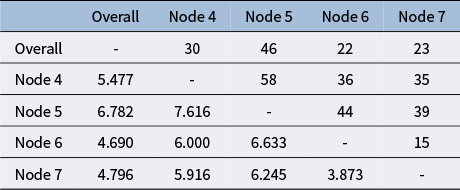

With the fixed sample size of 2,000 and the indegree centrality of DAG at 1.5, we evaluated the impact of the number of variables on the heterogeneous DAGs identification. The results are presented in Figure 6. Overall, the recognition effect of heterogeneous causal directions with Moderate structure is much better than the Extreme condition. Moreover, the DAG obtained by SELF-Tree is closer to the true causal directions at the leaf nodes with higher proportion. Similar conclusions were also drawn in the subsequent discussions on indegree centrality and sample size. Each index clearly distinguishes the performance of SELF-Tree model on correct DAGs (at the diagonal of heatmap) versus incorrect ones (at the off-diagonal of heatmap). As the number of variables increases, differences in SHD, FNorm, and TPR between correct and incorrect DAGs become more pronounced, while FPR better distinguishes DAGs with fewer variables.

Figure 6 The impact of the number of variables on the identification of heterogeneous DAGs. Each 3 × 3 heatmap’s number label

![]() $i$

corresponds to the DAG structure simulation scenario in Figure 3. The columns represent true DAGs, and rows represent the obtained DAGs based on the SELF-Tree model. Greater color contrast between the diagonal and off-diagonal areas of the heatmap indicates better recognition of heterogeneous causal directions.

$i$

corresponds to the DAG structure simulation scenario in Figure 3. The columns represent true DAGs, and rows represent the obtained DAGs based on the SELF-Tree model. Greater color contrast between the diagonal and off-diagonal areas of the heatmap indicates better recognition of heterogeneous causal directions.

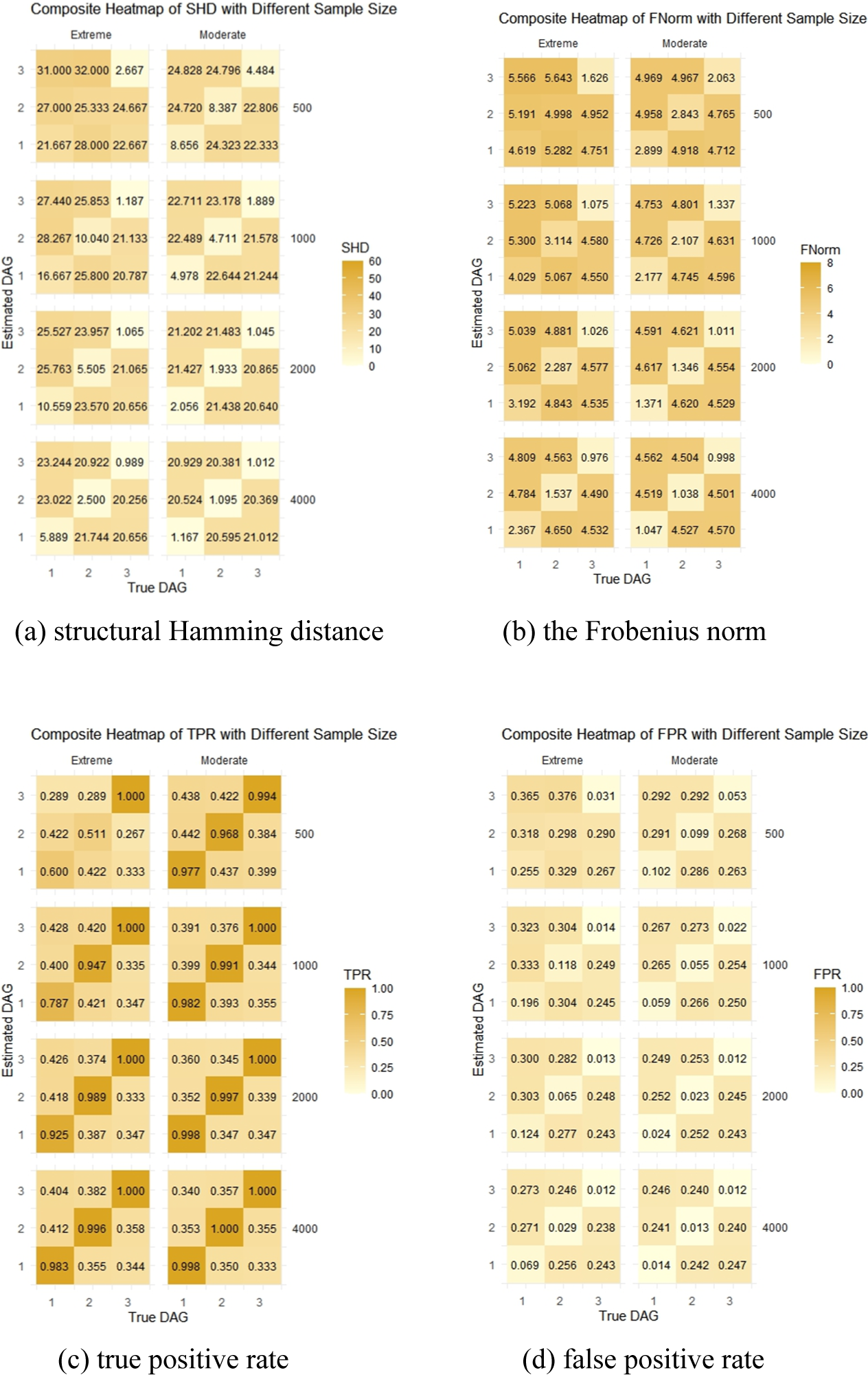

Figure 7 shows the impact of indegree centrality on heterogenous DAGs recognition when the sample size is fixed at 2,000 and the number of variables is 10. For SHD, FNorm, and FPR, correct and incorrect DAGs cannot be distinguished under Extreme conditions with low indegree centrality. When indegree centrality exceeds 1.0, changes in it do not significantly affect these three indicators. The TPR index can effectively distinguish correct and incorrect DAGs under all conditions, but higher indegree centrality leads to a worse performance on the incorrect DAGs identification.

Figure 7 The impact of indegree centrality on the identification of heterogeneous DAGs.