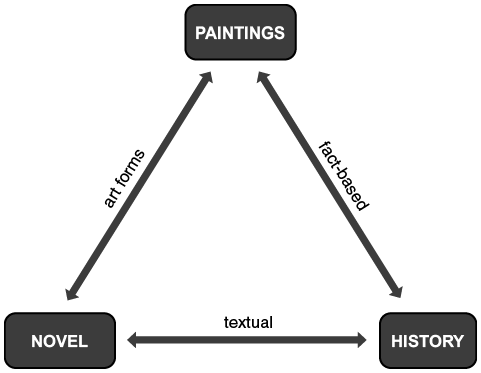

At the Dawn of History: Original Genius

At the core of the Enlightenment, with its firm belief in the steady, progressive rationalization of human affairs, we also encounter a new preoccupation with the past. What was it that, at the dawn of history, had sparked human civilization, or human civilizations, and launched them on their course of historical progress? Critics such as William Duff (An Essay on Original Geniuses, 1767) and Robert Wood (An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer, 1776) began to re-read Homer in search of clues, and instead found a conundrum. How could it be that, out of nothing, and without the benefit of having examples to emulate, Homer, primordial poet, could have achieved such an immediate benchmark status from which all classical standards were derived? Where did his ‘original genius’ come from, from whom had he learned his craft? What was there before this literary Big Bang?

In 1720s Naples, an as yet obscure Giambattista Vico had developed a model suggesting that each civilization originated with its own separate ‘Big Bang’. His treatise Scienza nuova argued that, in a concentrated act of self-articulation, societies would burst upon the scene of world history and become civilizations by formulating, all at once, their mythology, legal system and foundational epic texts. The Scienza nuova was an intellectual time bomb: scarcely noticed through most of the eighteenth century, it would became all-important fifty to a hundred years after its appearance. In Vico’s view, the gods of the original mythological pantheon were interchangeable with the mythologized early monarchs of those ancient epics that celebrated their heroic acts at the dawn of recorded history. The idea caught on. In Denmark, for example, the historiographer royal Peter Frederik Suhm approached early Scandinavian history in this way, tracing the descent of medieval rulers from a patriarchal ancestor Odin, raised by his descendants to the ranks of the gods; Suhm saw the Edda (and the sagas of the Edda’s continuation) as the early historical documentation of the Nordic peoples.1

People began to realize, also, that history shows more than one ‘original genius’. After Homer, there were, in modern times, Dante and Shakespeare. This emerging theory of original geniuses, readers will recognize, was a run-up to Hegel’s and Carlyle’s identification of the cultural hero-figure (Chapter 1). But the most important original genius to come to Europe’s attention was discredited by 1800 and is now somewhat obscure: Ossian. It was Ossian who helped detonate Vico’s time bomb. And it was Ossian who allowed every nation in Europe, even peripheral ones, to identify themselves as ancient civilizations, in terms of their own vernacular roots and their own ethnocultural origins.2

An Apparition from the Past

Around 1760, the literate public was dazzled by the rediscovery of Ossian, an original genius now retrieved from oblivion. Ossian, a fourth-century bard who had been active in Caledonia (Scotland) in the darkest Middle Ages, had remembranced the decline of his native heroic society in elegiac dirges in Gaelic (the Celtic language of the Scottish Highlands). These elegies were now scattered across dispersed manuscripts or else remembered orally, as ballads. At the behest of the Edinburgh literati, a fieldworker, James Macpherson, had gathered these scattered oral and manuscript sources and published them in English as Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the Highlands of Scotland (1760). The impact was sensational. Macpherson was charged to inquire further, and in the course of the 1760s he offered his readers the epic cantos he had reconstructed from the fragments into which they had been broken up. The titles were Fingal and Temora. They soon came under a cloud of suspicion and were later dismissed as forgeries; but not until they had enjoyed immense fame for a while as the Northern European counterparts to the Iliad and the Odyssey and had profoundly and lastingly shaken the poetic, the aesthetic and the cultural-historical outlook of literate Europeans.

Ossian was from the outset presented to the reading public as an original genius. The classical mottos on the title pages of the 1760 collection of Fragments of Ancient Poetry and of the 1762 Fingal both highlight the role of the ‘bard’ as the chronicler of the heroic deeds of the nation’s patriarchal ancestors, in the ‘primitive’ Homeric mode.Footnote * Hugh Blair’s Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian, the Son of Fingal (1763) made this the dominant frame in which Ossian was read: Ossian was a voice from the ‘infancy of societies’, like the skaldic bards investigated by Nordic antiquaries. Blair accordingly places him in a northern Celtic/‘Gothic’ tradition. Thenceforth, as Blair’s dissertation was prefixed to every subsequent Ossian edition, Ossian became, proverbially, the ‘Homer of the North’.

This in turn led to a great fission in the self-image of European literature. Madame de Staël’s summation, in her seminal On Literature in its Relations to Social Institutions (1800), is typical: it sees European literature as a dual tradition. One is Mediterranean, classical, rooted in ancient Greece and in the Roman empire; its mainspring is Homer. The other is northern, Romantic, rooted in Ossian. And she extends the dualism further: literature in the Mediterranean–classical tradition is temperamentally sanguine, realistically descriptive, and suited to societies with strong social conventions; whereas literature in the northern–Romantic mode is temperamentally melancholic, metaphysically contemplative, and suited to societies with a strong tradition of individualism. We seen the germ here of that temperamental dualism that later informed Thomas Mann’s ethnotypes, discussed in Chapter 1: the opposition between the superficial French and the contemplative Germans. Ossian is more, then, than a literary curiosity; as a northern Homer, and as figurehead and fountainhead of a non-classical, north European tradition, he triggered a veritable paradigm shift in Europe’s literary and cultural self-awareness.

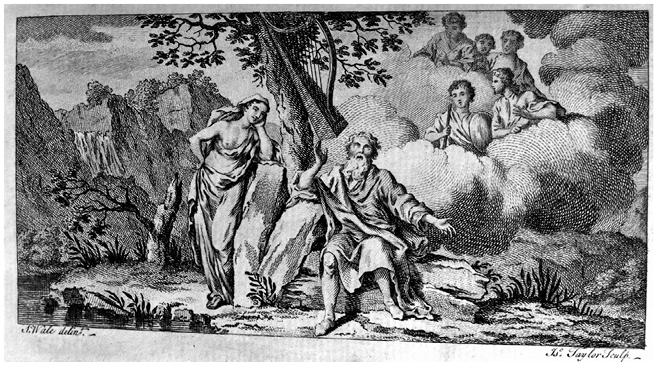

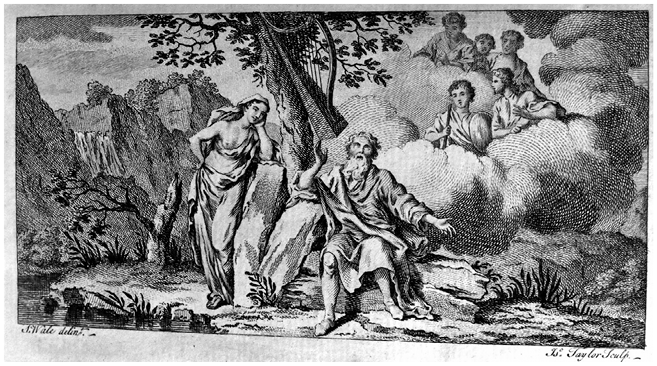

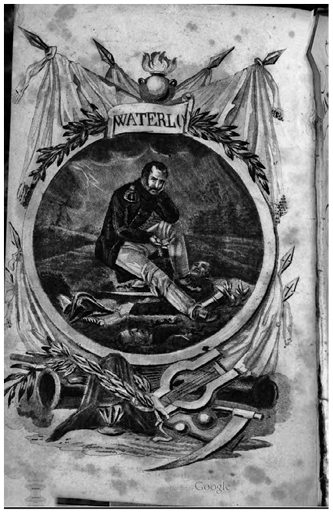

Ossian is even made to look like Homer (or like an Old Testament prophet), in line with his status as a primordial poet-chronicler of the epic Olden Days. His garb from the outset is represented as a crossover between a classical toga and a biblical cloak. His long flowing beard also fits this ‘hoary sage’ role pattern. Indeed, Ossian’s dress code has been iconographically fixed in dozens of paintings and has since then influenced the standard of how we see bards, druids and even wizards: from Merlin to Getafix, Gandalf and Professor Dumbledore. The ‘original genius’ iconography appears as early as the engravings that were used as vignettes for the title page of Fingal (Figure 3.1) and for Melchiorre Cesarotti’s Italian edition of the Poesie di Ossian (1763), itself the source for many other European translations.3

Figure 3.1 Title-page vignette for James Macpherson’s Fingal (2nd ed., 1762, engraving by Wale and Taylor).

What is depicted in Figure 3.1 is the scene of Ossian’s last elegy, the mournful culmination of a doleful series. The ageing bard, close to death, is alone on a windswept heath, with craggy mountains in the background. His harp, hung in a tree in an overt echo of Psalm 137, is set humming by the wind blowing through it. In a reverie he senses the presence of the ghosts of the past playing upon its strings with invisible fingers. He beholds the fair Malvina, daughter of Toscar, and Toscar himself, and all the other dead heroes of the past in a spectral apparition. Ossian addresses them:

I am alone at Lutha: my voice is like the last sound of the wind, when it forsakes the woods. But Ossian shall not be long alone, he sees the mist that shall receive his ghost. He beholds the mist that shall form his robe, when he appears on his hills. … The dark wave of the lake resounds. Bends there not a tree from Mora with its branches bare? It bends, son of Alpin, in the rustling blast. My harp hangs on a blasted branch. The sound of its firings is mournful. – Does the wind touch thee, O harp, or is it some passing ghost! – It is the hand of Malvina! … The aged oak bends over the stream. It sighs with all its moss. The withered fern whistles near, and mixes, as it waves, with Ossian’s hair. … The blast of the north opens thy gates, O king, and I behold thee sitting on mist, dimly gleaming in all thine arms. Thy form now is not the terror of the valiant: but like a watery cloud; when we see the stars behind it with their weeping eyes. … Beside the stone of Mora I shall fall asleep. The winds whistling in my grey hair, shall not waken me. – Depart on thy wings, O wind: thou canst not disturb the rest of the bard. The night is long, but his eyes are heavy; depart, thou rustling blast.4

This fey, spooky scene strongly affected the wig-wearing literati of the 1760s. Goethe translated this piece to include it in his Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), the book that is said to have triggered a wave of copycat suicides; and there are good reasons why this of all scenes was chosen to be the title-page vignette and ‘brand image’ for the entire work.

It is no exaggeration to say that in this fragment, we see the germ of what was to explode across Europe as the Romantic movement. The main effects of Ossian, which we will survey in what follows, were twofold: the idea of visionary inspiration; and the turn towards vernacular, nativist historicism in cultural and national consciousness. As we shall see, both of these made themselves felt, not only in literary culture (‘Romanticism’) and in scholarship, but also in public opinion (‘Romantic nationalism’).

Sublime Liminality and Visionary Inspiration

Ossian’s awesome and oppressive setting is one of the strongest manifestations of a new aesthetic that had been developing in the preceding decades. People no longer appreciated only the Beautiful, the locus amoenus, the park-like landscapes of Tuscany with their gentle, pleasurable aspect; what was now beginning to emerge was an alternative mode of appreciating the world, one well outside the comfort zone of the Beautiful. Austere mountain ranges, thunderstorms at night, battlefields, stormy seas, dark forests and craggy coastlines – places that would be the opposite of pleasant or pleasurable, that impress and awe onlookers with their unforgiving grandeur and render them aware of their vulnerability and mortality. This ‘pleasure mixed with horror’ was now identified as (a neologism) the Sublime. Edmund Burke had juxtaposed the two, the Sublime and the Beautiful, in a youthful essay in 1745, and Ossian – as we can see from the fragment quoted here – laid it on with a trowel.5 The Sublime, thus turbocharged, would dominate the aesthetics of Romanticism and would also inform the nascent genre of the Gothic. When we shiver pleasurably in our cinema seats or on our sofa at the sight of Dracula’s bat-circled castle in the eerie moonlight, we are following a tradition that started in 1760.

It was not just the external setting that proved influential: it was the way in which the setting sets the scene. The sublime landscape is also liminal – by which I mean that we are in a shadow zone between two worlds, a threshold (for that is the Latin root meaning of limen) full of ambiguities both spatial and ontological. The liminality effect, too, is used unstintingly. In space, the setting is between light and darkness (moonlight at night) and between heaven and earth (a mountain top under a lowering sky). Ontologically, we are between the embodied, material world of the living and the ghostly, spectral world of the dead. And it is in this liminal situation that Ossian, himself scarcely alive any more and aware of his impending death, and in a dreamlike reverie between consciousness and unconsciousness, summons from the spirit world the presence of the dead, passing on their memories to future generations who might otherwise forget. The strongest manifestation of that communication between the living and the dead is the ghostly sound of the harp, set vibrating either by the wind or by the spectral fingers of dead heroes.

This, too, was to be a seminal influence on the slowly forming poetics of Romanticism. The Romantic poets saw themselves as highly sensitive souls, attuned to the unspoken emotive charge of the situation, intuiting it and being able to express this intuition and inspiration in words. They saw themselves, their own souls, as Aeolian harps. Hence the constantly reoccurring theme of the breeze or wind that touches the poet or is perceived through waving grass or swaying tree-boughs, and that communicates a sense of transcendence to the sympathetic poet. The word ‘inspiration’ is central to Romanticism, and central to that word is its Latin root, in-spiro, ‘breathing into’, a spir-it infused by blowing air; much as God did when breathing life and a soul into Adam shaped out of clay (Gen. 2:7). And that breeze-borne inspiration would reach the poet very often in liminal situations: on beaches, in moonlight, in mist or fog, at dusk. All that is Ossianic.6

Channelling the Nation

Romantic poets see themselves surrounded by mystery and darkness and use their creative intuition to ‘tune in’ to that. ‘Humanity is surrounded by infinity, by the mystery of divinity and of the world’ – that is how Ludwig Uhland begins his 1807 essay ‘On the Romantic’. This tension-filled juxtaposition of the mundane and the transcendent is one of the most salient and all-pervasive characteristics of the Romantic generation of lyrical poets. Novalis had metaphorically phrased the Romantic oscillation between the humdrum and the sublime as a mathematical operation, analogous to raising a figure’s exponent to a higher power by squaring it (in German: potenzieren, so that 4 becomes 16) or logarithmically bringing it down to its root integer (in German: logarithmisieren, so that 25 becomes 5). As Novalis wrote,

Romanticizing something is to raise it to a higher power. The lower self becomes its higher self, much as we ourselves are such an exponential succession. … If I give the everyday a higher sense, give the well-known a mysterious aspect, vest the familiar with the dignity of the unfamiliar, then I romanticize it; and conversely so, when I logarithmically bring down the higher, unknown, mystical and infinite into a common expression.

The poetics of ‘inspiration’, both in Wordsworth’s Preface to the Lyrical Ballads and among his German contemporaries, are well known as one of the salient features of Romanticism. Poetry (and art in general) can, in this romantic view, electrify the world, potenzieren; enchanting and enrapturing it, as poetry itself results from enchantment and rapturous inspiration.7

This constant habit of potenzieren is the hallmark of Romantic idealism, its tendency towards epiphany: seeing reality in terms of its underlying essential principles, its Platonic ideas. The skylark apostrophized by Shelley is not an actual bird but a manifestation of the spirit of soaring creativity: ‘Hail to thee, blithe spirit! Bird thou never wert.’ When Wordsworth hears a Highland reaping-woman sing, or Keats a nightingale, those songs immediately become transcendent, generalized into a spirit of enchantment far beyond the time and place of the specific setting.

Ossianic manticism feeds into a Romantic revival of Platonic idealism, manifested also in the philosophy of Hegel, which loomed large over the entire following century. Hegel’s influence has been seen as politically pernicious by thinkers as different as Karl Popper (who aligns Plato, Hegel and Marx in his The Open Society and its Enemies, 1945) and Peter Viereck (Metapolitics, 1941). That alignment, while suggestive, is not unproblematic, and in any case it cannot be wholly derived from the after-effects of Ossianic poetics. Nonetheless, Ossian’s poetics of visionary inspiration did leave a specific political legacy. The power Ossian ascribed, in the teeth of Enlightenment rationalism, to poetic intuition and to non-cerebral rapture survived into the nineteenth century.

The poetics of visionary and creative power gave a new collective, ‘national’ authority to poets, artists and those who created from visionary inspiration. Their public personas developed from what Shelley called ‘the unacknowledged legislators of mankind’ into figures who, having the power of being inspired, also had the power to inspire others: the prophetic voices of the nation’s needs and aspirations. Victor Hugo would proclaim ‘The Poet’s Function’ in 1840:

The power to intuit the deeper meaning of things behind their appearance became a Romantic habit of epiphany. Michelet and Carlyle use it constantly. At every turn, concrete historical events or occurrences would be represented in terms of what they really stood for: the spirit of France, the principle of Liberty or Chaos. Michelet defines the French Revolution as ‘the advent of Law, the resurrection of Right, the response of Justice’ (‘l’avènement de la Loi, la résurrection du Droit, la réaction de la Justice’). Carlyle sees ‘The Great Man [as] a Force of Nature’. We also see it applied to the way people begin to see the relationship between state and nation. The state is the material expression, the nation its informing, essential quiddity.

The French Revolution had unleashed a torrent of turgid, swollen political rhetoric and grandstanding upon the world – all the new politicians grandiosely modelling themselves upon the orators and heroes of ancient history; and Napoleon himself, notoriously, carried a pocket edition of Ossian with him on his campaigns. (He also carried a lot of other stuff around with him, including a zinc bathtub, and Ossian’s sonorous dirges may have been used as a night-time soporific.) When Prussia had been reduced to a French puppet state, it was the intellectuals and poets (Arndt, Fichte, the Grimm brothers, Görres) who campaigned for a national resurrection. Typically, the resurrection was initially spiritual (cultural, literary, philosophical, moral: unpolitical) and was only in the second instance state-oriented. Finally, general Gneisenau urged king Friedrich Wilhelm III him to arm his subjects, form militias, and harness the force of public opinion. Friedrich Wilhelm dismissed this as a fictitious pipe dream, ‘mere poetry’, at which Gneisenau retorted that poetry was an indispensable and underrated force in social relations; ‘the future of the throne is based upon poetry’.9

That, in the event, was what ensued. In March 1813 Friedrich Wilhelm issued his manifesto An mein Volk, militias were formed in which the ageing philosopher Fichte and the young poet Theodor Körner volunteered, and at Leipzig in October that year the earlier defeats of Jena and Austerlitz were reversed. Napoleon, weakened by his Russian campaign, was vanquished and sent to Elba. Napoleon himself had intuited something like this, sensing the power of literature, when in 1807 he kept his implacable critic Madame de Staël banned from Paris, telling her to stick to her knitting; because in her salon, she could ‘make politics by talking literature, morality, arts, anything’.10

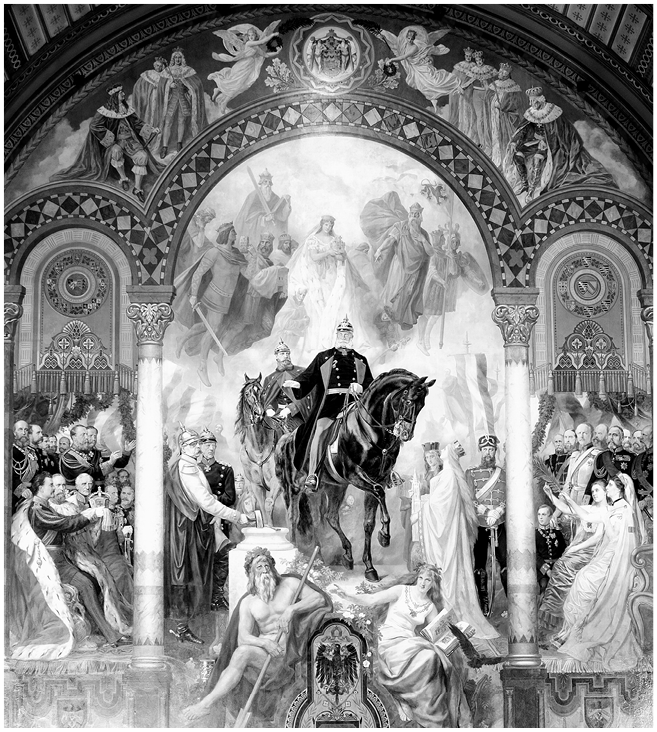

Prussia’s national mobilization of 1813, driven by poets and literati and accompanied by a great deal of patriotic verse, left its own ‘long tail’ of cultural memory.11 It was celebrated for the next 150 years as the glorious moment of national harmony between intellectuals, monarchs and generals and the active involvement of the Volk in the destiny of the state. Young Theodor Körner died of his wounds; as a martyr-poet, he became a role model for all young poets who would become the saviours of their nation henceforth. A line from his poem was so memorable that it was quoted in Berlin’s sports palace in 1943 when Goebbels declared total war: ‘Then, Volk, arise, and storm, break loose!’12

Pre-1914, Körner had inspired poets everywhere in Europe. His biography, written by his father, was translated into many European languages; the English one (1827, dedicated to Prince Albert) was noticed especially in Ireland. Alessandro Manzoni dedicated an ode to him; Irish Romantics translated him, and Lydia Koidula adapted a play by him into Estonian. The type of the ‘national poet’ emerged in his wake. Many of these are now cherished canonical figures: Petőfi, Mickiewicz, Thomas Davis, even (in the European colonies of Cuba and Bengal) José Martí and Rabindranath Tagore. Poets, dealing lyrically with intimate affects, now became public figures. When Ireland’s poet-critic Thomas Davis died at a young age in 1846, his fellow poet Samuel Ferguson wrote a ‘Lament for Thomas Davis’ (1847) that glorified him as nation-builder, sowing the seeds of a future harvest, and as the nation’s prophet (foreteller, forerunner):

The Voice of the Nation

Lyrical poetry (i.e. emotion-centred and driven by visionary inspiration) became a prominent vehicle for the expression and propagation of national ideals after 1800. The new lyricism was more direct and homelier in its diction than its stately eighteenth-century forerunners: Wordsworth had propagated the use of ‘language really used by men’ as the proper way to express a ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling’ and had turned to the simple, oral-performative metre of the ballad (rum te-tum te-tum te-tum) much as the German poets after Goethe had discovered the simplicity of the Lied. This had the added advantage that such verse could be easily set to music and performed as, indeed, a ballad or a song. Many Romantic ballads and verses in fact owe their popularity not to to the printed page but to vocal performance – as we shall discuss in Chapter 9. Sentimental lyricism became chamber music for domestic use (the Lieder of Schubert, often setting verse by Goethe, or Thomas Moore’s ‘Last Rose of Summer’); while patriotic verse such as Die Wacht am Rhein was performed by choirs as public proclamation.

The long-standing affect of ‘love of the fatherland’ was a popular theme for this generation of poets. Initially it was sentimental, referring merely to the attachment to one’s native place, the pangs of homesickness (or exile, or emigration), and the joy of returning after an absence. Walter Scott’s ‘Breathes There the Man’ set the tone and became a household invocation in the course of the century.

The idea that homesickness is a universal human affect, and that it comes naturally to people to spontaneously love their homeland, meant that an important political conclusion was being drawn from an intimate emotion. In the climate of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars it gained a fresh political edge. Love of the fatherland, from being a general moral virtue, a type of social altruism, now became the stalwart defence of one’s own nation against foreign threats. The poem ‘England and Spain; or, Valour and Patriotism’ (1808) by the seventeen-year-old Felicia Hemans is a case in point, celebrating the two anti-Napoleonic allies and the campaign in which her brother was serving. At the same time, the Romantic climate also meant that poets began to thematize the vernacular diversity of Europe’s cultural geography; ‘national’ in this sense could refer to the local colour specific to different countries. This ‘national’ taste fed the success of Robert Burns in Scotland and inspired the Irish melodies of Thomas Moore. Again, the work of Felicia Hemans, dating largely from the period 1810–1835, is a good example. While some of it is English-patriotic, sometimes in the militaristic and sometimes in the moral mode, her work is equally preoccupied with evocations of the culture of her adopted fatherland of Wales, with Walter-Scott-inspired scenes from Scottish history, with philhellenic celebrations of Greece, and with appreciative solidarity poems about the admirable medieval and modern champions defending the national liberties of Switzerland, Spain and Italy. If a common denominator is to be found here, it lies in the climate of the anti-Napoleonic wars and the post-Napoleonic restoration, linking poetic feeling to the local colour of scenery and historical memories and to the liberation of the nation from tyrants (especially foreign ones). She also wrote verse in praise of Körner; and in her collected works all this was grouped together under the rubric ‘national’.14

In Germany, Ernst Moritz Arndt used the form of the Lied for anti-French propagandistic purposes, militaristic rather than lyrical. Arndt was particularly successful with his song ‘What is the German’s Fatherland?’, which in stanza after stanza asks, rhetorically, whether the German’s fatherland is located here (along the Rhine), there (near the Alps), or somewhere else (the coast). The refrain answers: ‘Nay! That it cannot be, the German’s fatherland is greater than this.’ Finally, the answer is given: it is ‘wherever the German language is spoken. That is must be! That, bold German, you may call yours! That is the German’s fatherland!’ It became Germany’s answer to ‘La Marseillaise’ for a while, and it was particularly popular as a choral anthem; we shall encounter it again in Chapter 6.

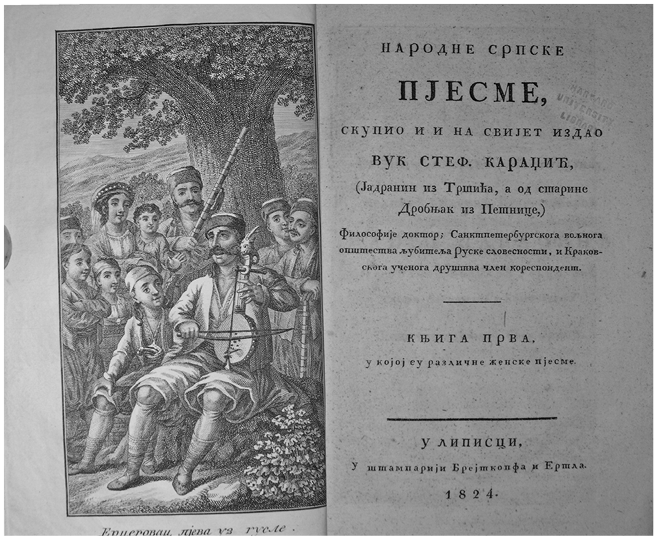

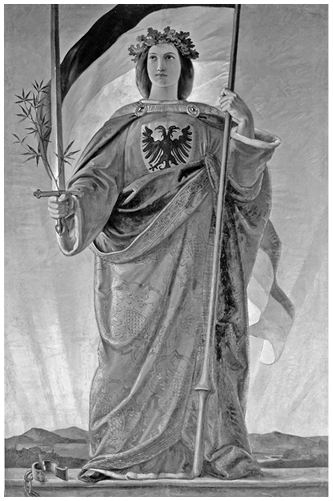

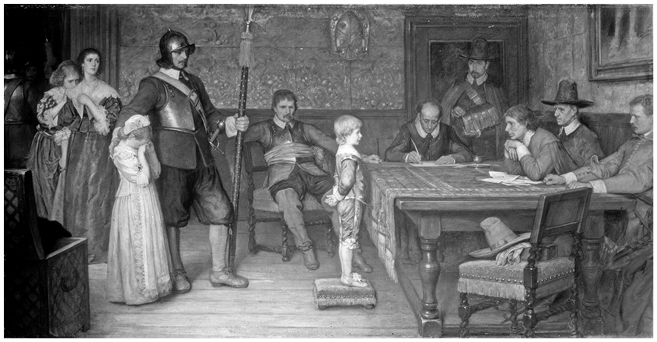

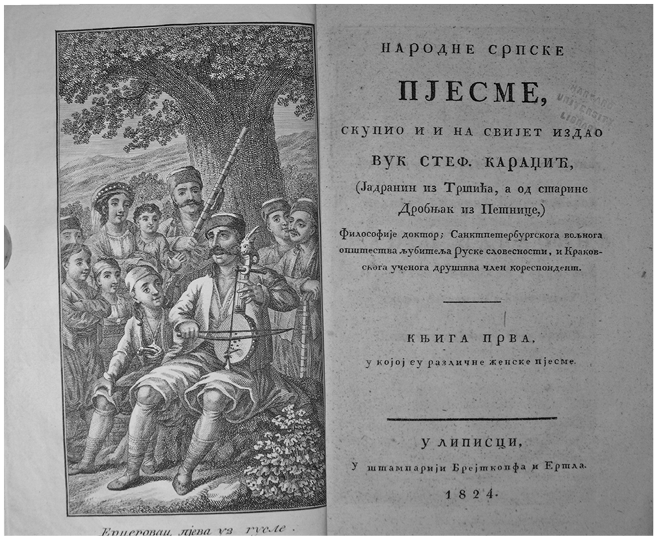

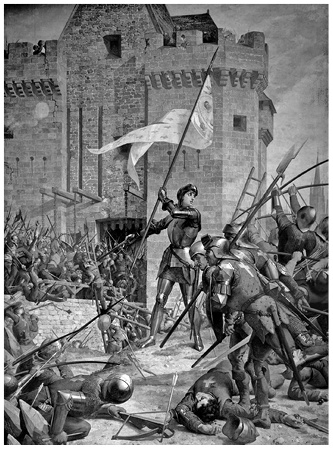

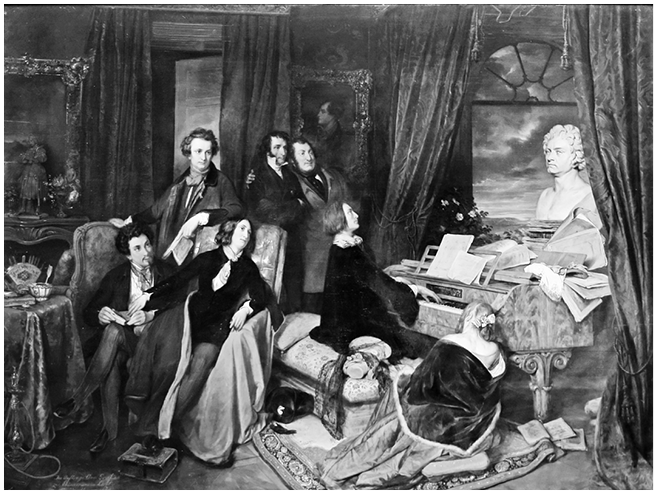

No less inspiring across Europe were the songs of Pierre Béranger, who in the restoration climate of the post-Waterloo decades kept a more populist nationalism alive in France. Like the goguettier Émile Debraux, his songs would recall the glorious memories of Napoleon’s great victories, the moments when France stood proud and tall (Figure 3.2). These songs were written in opposition to the oppressive restoration regime of the Bourbons, which demonized the very memory of Napoleon, and both poets spent time in prison over their songs of former national glory. Arndt, too, fell under a political cloud after 1818 as the Metternich regime tightened its censorship and mistrust of ‘demagogues’ grew. But this only enhanced the reputation of Arndt and Béranger as stalwart and courageous defenders of their national glories against the dynastic power of autocratic monarchs.

Figure 3.2 Frontispiece to Emile Debraux’s Chansons nationales (1822).

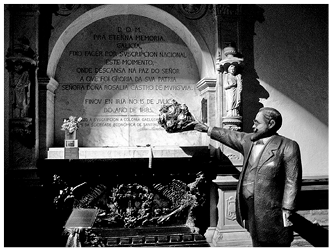

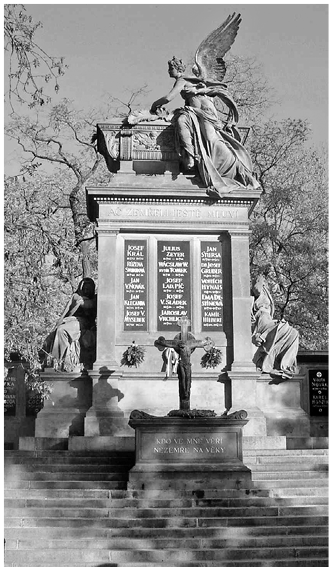

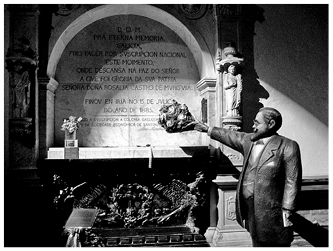

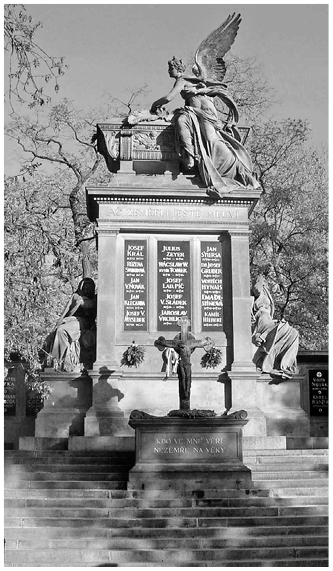

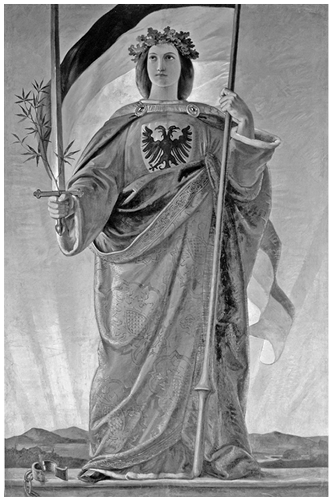

And so the public status of poets could be semi-clandestine, rebellious or state-endorsed (establishment poets such as Tollens in Holland or Oehlenschläger in Denmark). The most ‘Romantic’ ones were those who were persecuted or insurrectionary activists such as the Hungarian Petőfi, the Pole Mickiewicz, the Bulgarian Hristo Botev and the Ukrainian Taras Shevchenko. An in-between category included Felicia Hemans in England, Thomas Davis in Ireland, France Prešeren in Slovenia, Karel Hynek Mácha, Jan Kollár and Ľudovit Štúr in the Czech and Slovak lands, Almeida Garrett in Portugal, Jacint Verdaguer in Catalonia, Guido Gezelle in Flanders, Henrik Wergeland in Norway, Johan Ludvig Runeberg in Finland, Lydia Koidula in Estonia. The topics of their verse could range from the overtly nationalistic, with a deliberate propagandistic intent, to more lyrical effusions whose main nationalistic effect lay in their demonstration that the vernacular language could be used for serious, ambitious literary purposes. Cases in point are the long dramatic poem in Occitan, Mirèio, which earned its author, Frédéric Mistral, the 1904 Nobel Prize (the event depicted in Figure 10.3); and the Galician verse of Rosalía de Castro, whose tomb is shown in Figure 3.3.15

Figure 3.3 Tomb of Rosalía de Castro in the Pantheon of Illustrious Galicians, Santiago de Compostela (sculpture by Jesús Landeira, 1891). The figure offering a bouquet represents her husband, the historian Manuel Murguía.

The Poet as Role Model

Poets themselves adopted a Romantic self-image and became Romantic-nationalist role models. Körner as a soldier-poet was celebrated as a martyr to the national cause both inside and outside Germany, but his type of role model is in fact one of several templates. Three other ‘poetic stances’ besides the soldier-hero-martyr poet (Petőfi, Botev) can be seen, and these may be linked to Byron, Wordsworth and Scott respectively.

Byronism was one of the most pervasive and enduring repercussions of the Romantic movement for European (and indeed global) culture. It was inspired less by Byron’s actual poetry (which is often glibly satirical and if anything classicist in its orientation) than by his poems’ protagonists and indeed his own self-dramatization. The Byronic hero (and Byron himself in his Byronic pose) is a solitary, morose, brooding character, virile but misanthropic, whose capacity for tender feeling has been scarred by bitter experiences. Rick, he of the eponymous café in Casablanca as played by Humphrey Bogart, is probably the most powerful twentieth-century embodiment of a Byronic hero. Haughtily averse to social niceties, he leads a wandering existence and stands apart from the crowd because his ideals are too lofty, his passions too intense and his manners too rough-hewn to fit into modern conventions. Heroes such as Manfred and Childe Harold are of this type, and Byron’s own restless, scandal-ridden wanderings were seen as expressions of this passionate, intriguing (‘Romantic’) character. What appealed especially was that in his anti-bourgeois nonconformism, Byron evinced sympathy for the outlaws and warlords of harsher, non-civic societies and adhered to an honour-and-shame ethos that was disappearing in the modernization process. Thus Byronism glorified the lawless peripheries of Europe, from the Balkans to the Andalusia of Mérimée’s Carmen, and his poetry became the great beacon for a solidarity between the ethos of the cynically Romantic rebel-poet (emulated by the likes of Pushkin, Heine and Prešeren) and the emerging national cultures in Europe’s late-imperial borderlands with their outlaws and brigands (‘klephts’ in Greek, ‘hajduks’ in the Slavic languages). This function was hugely strengthened, of course, by Byron’s active philhellenism and his death in Greece (1824) as a supporter of the anti-Ottoman insurrection there.16

The Wordsworthian stance is that of the inspirational retreat into the idyll of the countryside and proximity to nature. This idyllic lyricism gives a voice to the rural peasantry and creates a conduit from spontaneous folk art into high literature. In national movements whose language was just emerging from the stigmatized register of mere peasant patois into the ambitions of a literate, public-sphere status, such poetry could be a nationalist inspiration (e.g. the Galician verse of Rosalía de Castro or, in the Catalan language, verse by Verdaguer and Teodor Llorente). One lyrical trope that is common to a number of Romantic poets from subaltern cultural communities is that the lost beloved is deified (‘potenziert’) into an inspiring muse-figure or even into a personification of the yearned-for nation: thus with Nikoloz Baratashvili’s conflation of Princess Dadiani and his subjected Georgian homeland, or with Jan Kollár’s Slavy Dcera (‘Daughter of Slava’, 1824), Auguste Brizeux’s Breton Marie (1832) and (through the Kathleen Ní Houlihan trope) W. B. Yeats’s idolatry of the unattainable Maud Gonne.

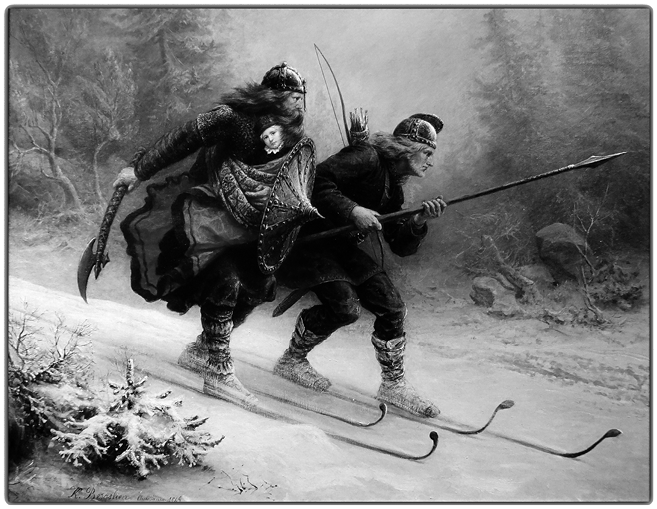

Walter Scott brought into circulation the role model of the wandering minstrel voicing cultural memories, especially through his popular poem ‘Lay of the Last Minstrel’. It appeared in 1805, just when the cult of Ossian as a ‘bard’ had died out, and provided an alternative Romantic model in its stead (see Chapter 7). It presents an emotional, incident-rich (‘Romantic’) tale of olden days; the frame-setting, however, is that of an Ossianic poet who has outlived the glories of his former days but who can awaken old tales through his rapt inspiration, taking his audience into the fictional world of long-vanished deeds and passions. This, too, was a role model; and the verse of Adam Oehlenschläger and Esaias Tegnér (in Denmark and Sweden) and the cult of ‘troubadours’ and ‘bards’ singing of the nation’s glorious, colourful past cannot be understood without Scott’s post-Ossianic prototype. It also explains why the historical narrative poem maintained great popularity alongside the new genre of the historical novel.17

Thus the register of the Romantic poet is situated between the soldier and the outlaw (Körner and Byron), between the aristocratic past and the contemporary peasant (Scott and Wordsworth). In all cases, the poet enjoys a privileged status as the voice of their nation (or of that nation’s aspirations) and as having, through the power of inspiration, an intuitive understanding of the transcendent principles informing contemporary affairs.

Imagined, Embodied and Affective Communities

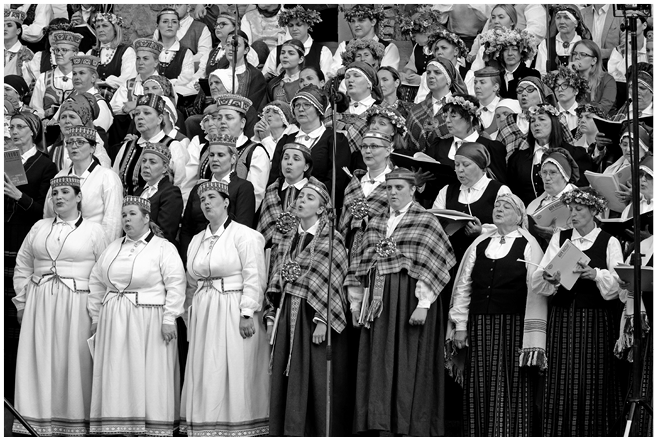

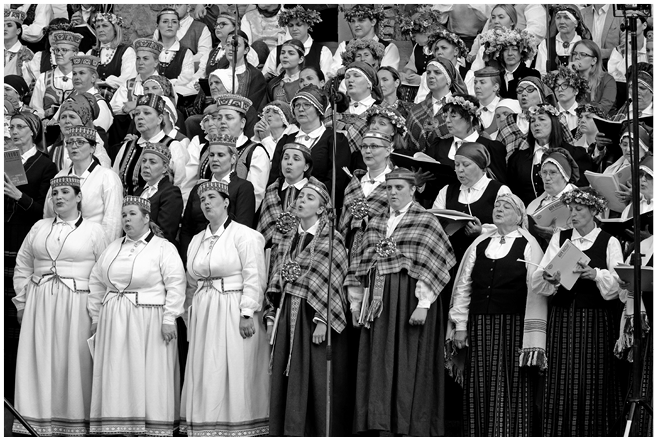

Benedict Anderson’s classic Imagined Communities (1983) has given us a powerful template aligning the rise of nationalism (or rather, of the ‘imagined community’ self-defining as a nation) with that of ‘print capitalism’: individuals would, thanks to modern mass-distributed novels and periodicals, become amalgamated into a readership, all readers at the same moment experiencing and being involved in events and narratives that lay far outside their domestic ken. The point stands, but we can add to it. Ann Rigney has shown how mass festivities in numerous Scottish towns around the centenary of Robert Burns (1859) created a sense of national cohesion that was not mediated over long distances by the distribution of printed matter but was experienced in a direct physical co-presence of people: alongside the ‘imagined community’ there was also the ‘embodied community’, and other studies of the festive culture of the nineteenth-century confirm this sense that ‘embodied’ togetherness was as important as its virtual, imagined counterpart. This embodied co-presence specifically appears to have involved the oral or choral performance of lyrical poetry, and often celebrated poets as the common focus of the crowd. The poet could be a cherished historical one, as in the commemorative festivals celebrating Shakespeare, Camões, Dante, Pushkin, Petrarch – the ‘original geniuses’ of their countries’ literary tradition. Or else, specifically in subaltern nations, much more recent memories could be evoked of recent champions of their nation’s literacy and literature: Conscience in Flanders, Mickiewicz in Poland (the statues erected in his honour were torn down by the Nazis and re-erected after the war), Mácha in Prague, Prešeren in Slovenia, Wergeland in Norway, Moore in Ireland, and Schiller in nineteenth-century Germany. In each case, the statues rendered the revered poet a firm presence in the city’s streetscape; but the statue was also a venue for commemorative gatherings, proclamations, cantatas, wreath-layings. That praxis of embodied community-gathering still continues: I saw in pre-COVID Rome how the many Filipino and Filipina domestic workers in that city would gather convivially, on their free Saturday evenings, around the statue of the national hero José Rizal on Piazza Manila, often placing flowers there as a sign of affection and connection. And in the nineteenth century, when freedom of association was not yet the self-evident civil right it is nowadays, the funerals of poets would provide a legitimate occasion for mass demonstrations asserting the nation’s common identity around a shared lyrical core. Such occasions were often redolent with allegorical pathos. At the funeral of the Czech activist writer Karel Havliček Borovský, the poet Božena Němcová laid a wreath in (or on) his coffin; in popular retellings of this event, that wreath was soon mythologized into a crown of thorns, as a mute protest at the dead poet’s prosecution by the Habsburg authorities.18

Such gatherings, and the singing of cherished songs and anthems on public occasions, were a powerful manifestation of a type of literature that did not owe its social outreach to ‘print capitalism’ but that, as Romantic lyric, spoke directly, without mediation, from heart to heart and was performatively reactivated from generation to generation. ‘La Marseillaise’ and ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ were the tips not of an iceberg but of a sea of heaving and crunching pack ice.

Antiquaries and the Literary Past

Ossian’s appeal to the late-Enlightenment reading public lay not only in his uncanny settings and spooky scenes but also in the remarkable tale of his retrieval: snatched from oblivion in a remote corner of the Old World, where his memory lingered among balladeering Highlanders in desolate mountain ranges and in almost-illegible manuscripts. The mission of James Macpherson seems almost like an Indiana-Jones-style quest for lost treasures. A difference between the two is that the fictitious Indiana Jones is an archaeologist, a scholarly specialism that did not yet exist in Macpherson’s day. Those who investigated antiquities were called antiquaries, and they had a wide remit: ‘antiquities’ included material remains (be they from the medieval, the classical or the prehistoric past) and whatever could be found in ancient manuscripts, be they ballads, genealogies, law texts or chronicles. Macpherson was an innovator in that he searched for antique remains in living oral poetry.1

Another difference is that antiquaries had no academic or professional standards to go by. They were learned, dedicated amateurs, usually with a steady independent income, and although there were some fledgling associations (a Society of Antiquaries was established in London in 1707 and another one in Edinburgh in 1780) they worked largely on their own and on whatever material they happened to come across. They were also often carried away by their enthusiasm: their interpretations of the past were, more often than not, over the top, unchecked by sceptical reservations or by factual background knowledge. They had no qualms about tracing the origin of the Irish and Scottish Celts back to Carthaginians or Phoenicians. In the eighteenth century, before solid comparative linguistics, antiquaries frantically tried to read Gaelic with the help of Greek and Hebrew dictionaries. In his novel The Antiquary (1816) Walter Scott drew the portrait of such an amateur scholar of the Macpherson generation with affectionate irony; fondly, because Scott was himself an antiquary at one remove. He worked on ancient ballads and minstrelsy, on Scottish legal and social history, on the country’s ancient manners and customs, and he hoarded material remains of the past at his museum-mansion at Abbotsford. And he was a proud, card-carrying member of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries. But Scott’s Antiquary also signalled that this type of antiquarianism was a thing of the past. In the next century, the investigation of the past would split up into the scholarly disciplines of archaeology, philology, and the studies of folklore and mythology. The undisciplined imagination with which antiquaries had approached the past was no longer suitable to these new, respectably academic offshoots, and it became the characteristic feature of a Romantic literary genre of which Scott was the first and foremost practitioner: the historical novel (on which, see Chapter 7).2

Cesarotti’s Italian edition of Ossian carried, besides the frontispiece that we have seen in the previous chapter (Figure 3.1), another vignette on its title page (Figure 4.1). It shows a dapper man, obviously an ‘amateur gentleman’ rather than a menial, wearing a hat – probably against the sun, because the surroundings look more Italian than Highland Scottish. He is digging with a spade around some half-buried objects; a marble slab next to him carries a quotation from Horace (Epistles I.6:24–25), ‘Whatever lies buried below ground, time will bring to light’. The gentleman is clearly an archaeologist, and his work is to unearth the remains of the past. That is what was famously going on in Cesarotti’s Italy at the time: the ruins of Pompeii were being uncovered in these very decades, and caused a sensation. Word had spread to Germany as a result of J. J. Winckelmann’s letters ‘on the discoveries at Herculaneum’ published in 1762 and 1764.Footnote * This is an altogether different frame for reading Ossian from the ‘ghosts on a moonlit mountain top’. Ossian was an antiquarian sensation.

Figure 4.1 Title-page vignette for Melchiorre Cesarotti’s Italian version of Ossian (1763).

The juxtaposition of Ossian with Homer, which we noticed in Chapter 3, is not just a typological one (both were sublime original geniuses relating the heroism of the ancestors in epic form) but also a historical one. With Ossian, Scotland (and, by extension, Northern Europe in general) is rediscovering its ancestral antiquity. Until then, classical and biblical antiquity had held the monopoly on Europe’s most ancient cultural memories; that monopoly was now broken. The impact of Ossian was that Northern Europe could opt out of this Mediterranean, biblical/classical ancestral antiquity and look back on its own cultural roots. That pattern was reinforced by the fact that at the same time Nordic antiquities, rooted in the Edda and the Heimskringla, were being reactivated by Scandinavian antiquaries. The result was that for a while, the ‘Gothic’ (Scandinavian) and ‘Celtic’ antiquities of Northern Europe were being lumped together; the trend had been set by Paul-Henri Mallet’s Monuments de la mythologie et de la poésie des Celtes, et particulièrement des anciens Scandinaves (1756). By that time, the Swiss antiquaries Bodmer and Breitinger had also retrieved a manuscript of the Nibelungenlied, which they presented to the reading public as ‘Chriemhild’s Revenge’ (Chriemhilden Rache), commenting that, although it fell short of the Aristotelian rules for tragedy, it could stand, as an epic poem, beside the pre-Aristotelian epic poet Homer.3

All this dealt a huge blow to the still prevalent classicism of the time. Until then, the cultural rearview mirror had reached back to the periods of humanism and the Renaissance and then, bypassing the dark and scantily known Middle Ages, had focused on the biblical and classical periods – the recourse to which had allowed those humanists and their Renaissance successors to emerge from Europe’s medieval benightedness. Now, however, Northern Europe’s vernacular, non-classical ancestry could be traced back further along native lines towards an origin, and an original genius, of their own. And the Middle Ages themselves became something more than a centuries-long night-time of impenetrable barbarism: the Middle Ages now became a literary Pompeii, a continuum for the nation’s buried cultural heritage, with chivalric and epic heroes such as King Arthur and Siegfried the Dragon-Slayer appearing in a favourable, prestigious light. These philological discoveries not only inspired the medievalism of the Romantic century but also necessitated a new, national form of literary history writing. Literary history had to be rewritten and to accommodate in its opening chapters these newly discovered materials: ancient, heroic, vernacular.4

Cesarotti himself was quite sensitive to this ‘shock of the old’. In his annotations to Ossian and his Homer translations, he instilled a great many of Vico’s theories of cultural history, notably that each civilization articulates its cultural self-awareness, and marks its emergence into history, in a primordial Big Bang where laws, epic-heroic poems and religious myths are almost undifferentiated. These notions in turn found their way into the German translation of Ossian (which followed the Italian version rather than Macpherson’s English one). We may even surmise that it is through the intermediary stepping-stone of Cesarotti’s Ossian that Vico’s ideas began to spread in the Republic of Learning.5

Cesarotti’s Ossian presentation triggered a veritable paradigm shift in European literary history, which outlasted the brief fame of Ossian himself. It triggered a form of literary archaeology (digging around to see what submerged things could be brought to the light of day). The treasures found by Macpherson led to a gold rush; and the Klondike of that literary gold rush were libraries and archives – which, as it happened, were now beginning to make their riches publicly available.

Archaeology in the Archives

Libraries are like sponges: they soak up available books and texts circulating in the marketplace, and that ingestion is by and large a one-way process. Libraries siphon off the marketplace: they are predicated on acquiring and keeping stuff. Over the decades and centuries – as institutions, libraries can be very long-lived – dispersed materials drift from private ownership into library collections. The oldest of these are monastic libraries and court libraries, with college/university and municipal libraries following in the later Middle Ages. The public had only limited access to these.

But periodically, sponges get squeezed, and then their accumulated storage either trickles out or gushes out profusely. Sometimes, libraries are opened to the public: Florence’s Biblioteca Laurentina was opened to scholars in 1571, and Louis XIV opened the Bibliothèque du roi to the public in 1692. A major squeeze occurred with Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. The monastic libraries of medieval England were plundered by the king’s officials, and a great number of ancient manuscripts circulated among private owners (John Leland, William Camden, Matthew Parker, Lawrence Nowell, Robert Cotton) before finally settling down, once again, in other libraries: Matthew Parker’s books became the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and Robert Cotton’s library, donated to the nation in 1700, was merged with the Sloane, Harley and Royal libraries to form the British Museum’s library in 1757. It was here that an inquisitive Danish scholar, Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin, located the sole surviving copy of the Beowulf epic in 1786–1787. A first edition was published in Copenhagen in 1815. Literary archaeology was beginning to bring long-lost manuscripts back to the light of day.

At precisely this time, a great library squeeze was underway in Europe. As in Henry VIII’s day, it targeted, at least initially, monastic libraries. The process began with the suspension of the Jesuit order in the 1770s. In Lisbon, this meant that the Jesuitical Ajuda library was transferred to a new, state-run teaching institution; and it was here that the oldest surviving medieval manuscript of vernacular love songs came to light: the Cancioneiro da Ajuda. A first edition was published in Paris in 1823.

After the Jesuits, under Emperor Joseph II, the libraries of contemplative orders such as the Benedictines were targeted; then came the nationalization, by the authorities of the French Republic, of monastic and noble libraries in France; and then came the libraries, in the German lands, of those church establishments that were annexed by Napoleon or (in the great Reich reshuffle of 1803) were placed under the control of temporal lords.Footnote * In France, the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal was formed in Paris, incorporating many former monastic libraries from the metropolitan area, and the former Bibliothèque du roi and Bibliothèque mazarine became public research institutes. In Germany, the huge libraries and archives of formerly self-governing ecclesiastical establishments were transferred to the court libraries of Vienna, Munich and Stuttgart, and as part of that transfer they were inventorized and recatalogued. The Munich court library swelled to become one of the largest in Europe, a process mirrored at slightly smaller scale at the Württemberg Library in Stuttgart. Finally, when Napoleon annexed the Papal States in 1808, even the mother of all libraries at the Vatican was placed under the bureaucratic management of French civil servants. And men of letters descended in great numbers on these newly accessible hoards, made many discoveries and laid the basis for many a scholarly career. In Munich, soon to become the capital of a Napoleon-created kingdom, the court librarian Johann Christoph von Aretin encountered, with some wistfulness, an old document about Charlemagne in the mediatized library of Freising Abbey. He published it in 1803 with a nostalgic preface linking, quite aptly, the simultaneous overhaul of ancient libraries and overthrowing of ancient monarchies.

It is now a thousand years ago that Charlemagne founded the German empire. I alert my readers to this fact, not to draw their attention to the remarkable changeability of things during that timespan, or to make them ponder the recent events which have appeared to threaten that very empire with an overthrow after its millennial existence; rather, I would mark a literary jubilee of that great occurrence, and an occasion presented itself when I could consult a remarkable ancient German manuscript in the most ancient abbey of Weihenstephan near Freising, and which with all the literary treasures of the Bavarian monasteries has been lodged in the Munich court library.6

One of the biggest finds was in Rome. The Vatican library, now under Napoleonic administration, was inventorized by a librarian called Gloeckle – notorious for his drunkenness and known in Rome as il porco tedesco – together with the literary historian J. J. Görres; what they found was the old collection of the Palatinate counts on the Rhine, which had been taken from Heidelberg in 1622 as war booty and presented to the pope. This ‘Biblioteca palatina’ turned out to be packed with long-lost classics from medieval German literature: chivalric romances, Tristan, Reynard the Fox, Lohengrin (of which Görres himself would bring out an edition in 1813) and much besides. Görres sent an open letter to the Heidelbergische Jahrbücher der Literatur in 1812, hoping to raise subscriptions for a printed edition of all these classics. Two centuries later we can still sense the breathless excitement of these thrilled bookworms.7

The European Republic of Philology

When we look at the text editions that came out between 1800 and 1840, we see that they include practically all the ‘classics’ that now feature in the opening chapters of literary history books. Besides the Portuguese cancioneiros, Reynard, Beowulf, the Nibelungenlied and Lohengrin, the list includes the French Chanson de Roland (discovered in the mid-1830s in the Bodleian library by Francisque Michel), the Russian/Ukrainian Lay of Prince Igor’s Campaign, the Dutch Legend of Saint Servatius, the Irish Annals of the Four Masters and Deirdre/Cuchulain tales, and many others. Literary histories were, quite literally, being rewritten and traced back to their vernacular and tribal origins rather than to classical antiquity.

Friedrich Schlegel gave a name to the scholars who were doing this work. Rejecting the speculative waywardness of the old-school antiquaries, he called for a systematic comparative-historical method, and in his diaries began to call this line of work philology. In doing so he revived an old Latin word for ‘erudite bookworm’, which, however, had been given a trenchant new importance in Vico’s Scienza nuova. There, Vico had compared two forms of knowledge production, one dealing with the nature of things and the other with the meaning of things. The former Vico called philosophy, the latter philologia. The underlying meaning of that term was a preoccupation with logos, the language-empowered faculty of human cogitation. Schlegel applied this in his Viennese lectures on ancient and modern literature (1812, published 1815). What makes humans different from animals, Schlegel argues, is language (with each human society developing their own language: see Chapter 6). The primary function of language, besides communication, is commemoration: the articulation of memories and their formulation into something that is more than a fleeting state of mind. Once these memories take the form of crystallized narratives recalling important events and figures from a past that is longer than a human lifespan ago, such a society has a culture: it is no longer a band of grunting cavepeople but on its way to becoming a civilization. The primal role of literature, for Schlegel, is to encapsulate collective (he calls them ‘national’) memories.

What appears important above all else for a nation’s development and indeed its spiritual existence is that a people should have great national memories, which mostly reach back into the dark times of its first origins, and which it is the great task of literature to maintain and to celebrate. Such national memories, the finest inheritance that a people can boast, offer advantages that cannot be matched by anything else. When a people finds itself exalted and ennobled in their feelings by their possession of such a great past, of such memories from ancient days, in short: of such a poetry, we must admit their higher standing in our esteem. … Remarkable deeds, great and fateful events do not suffice in themselves to gain our admiration and to sway the judgement of posterity. A nation’s value depends on its clear awareness of its deeds and destinies. This self-awareness of a nation, as articulated in contemplative and descriptive works, is its history.8

Schlegel in fact updates Vico for the new century. He combines the textual investigation of ancient literary history with a sense of comparative historical linguistics and with what he calls ‘Völkergeschichte’; as such, he is also one of the great harbingers of a new philology, which takes over from the antiquaries of the preceding generations.9

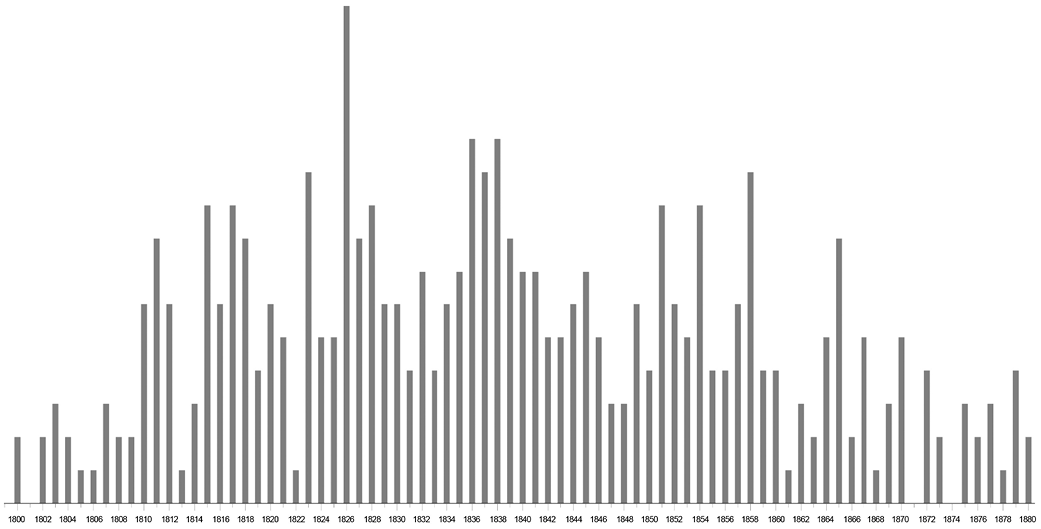

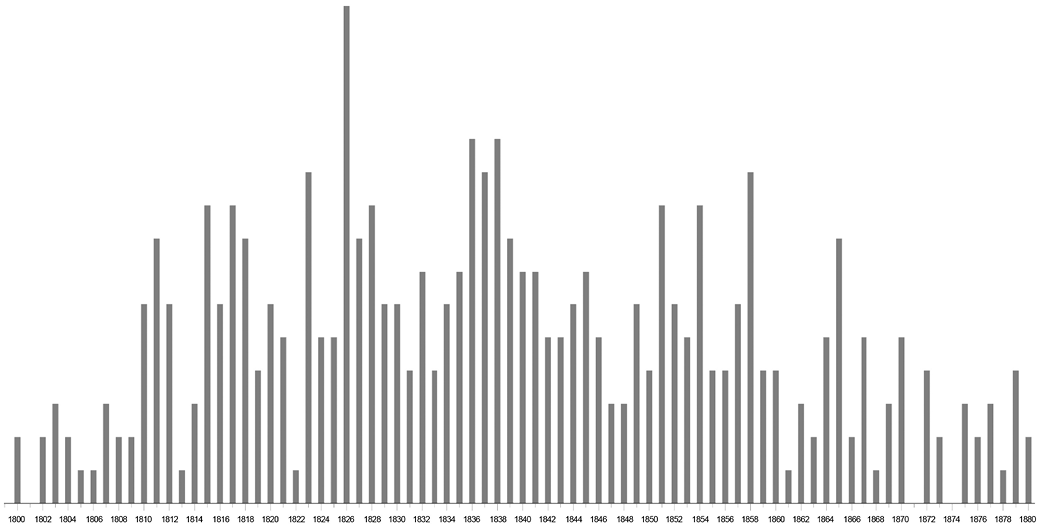

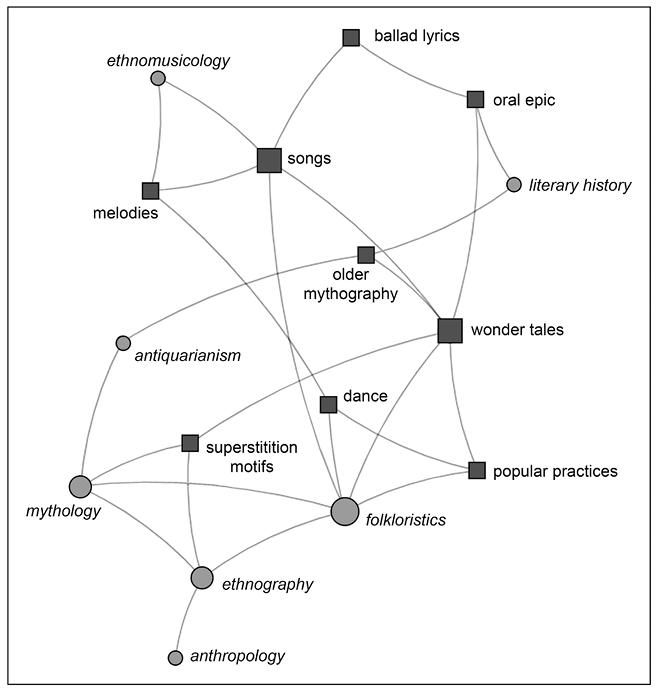

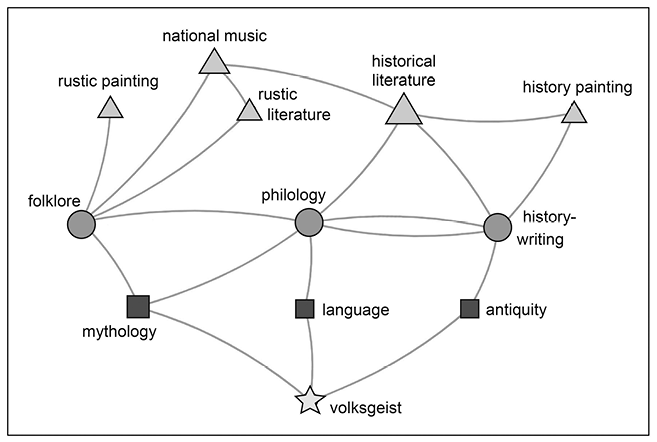

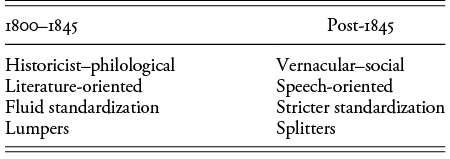

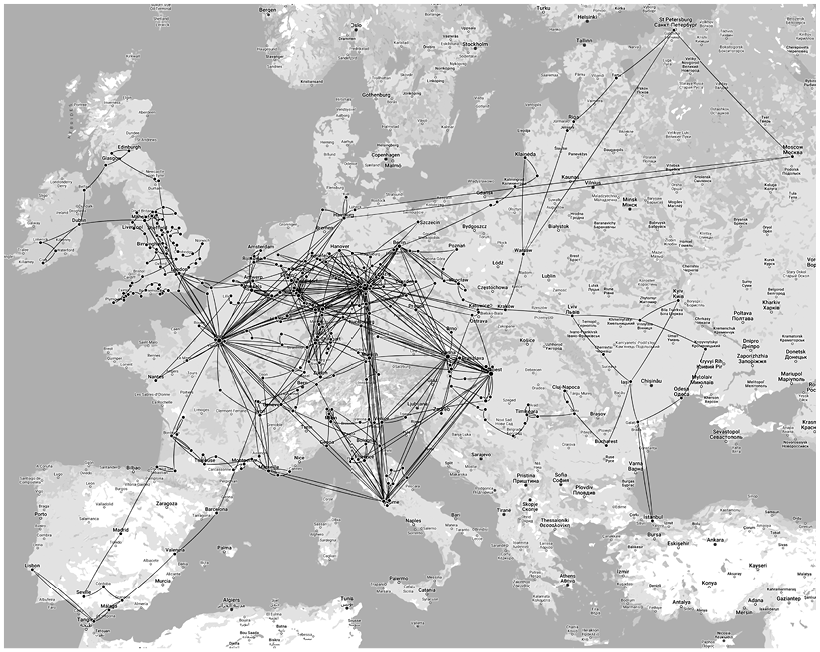

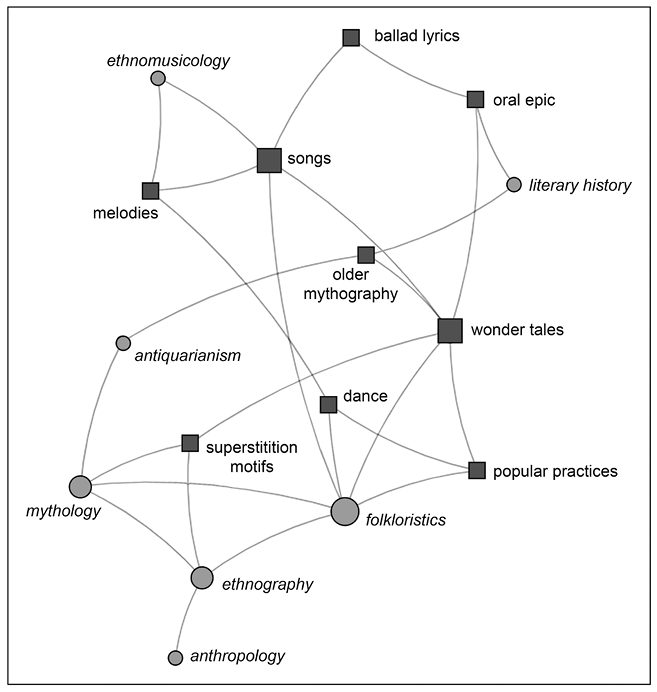

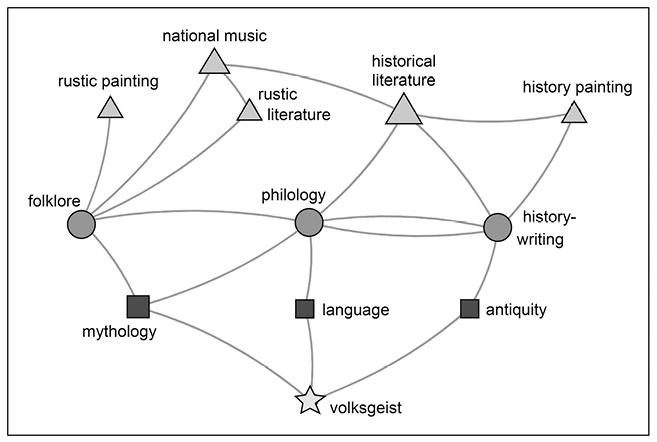

The takeover was effected by a wave of re-editions of vernacular classics. The Encyclopedia of Romantic Nationalism in Europe lists some 500 editions of ancient texts over the century,Footnote * with productivity peaks in the 1820s, the late 1830s and the 1850s (Figure 4.2). Productivity after 1860 consists mainly of re-editions of the initial harvest and of belated text discoveries in comparatively poorly archived cultural communities.

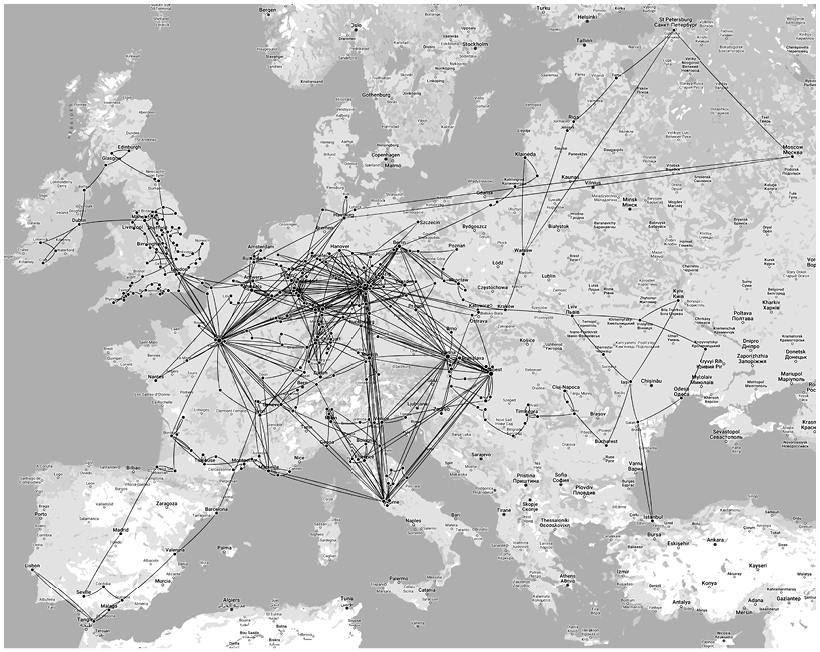

The striking thing about this rediscovery of nations’ vernacular roots was that, while it served to set off these nations against each other as each having their own, distinct cultural mainsprings, it was an almost pan-European enterprise. It was not just that German libraries yielded medieval texts to local (German) philologists, while French and Portuguese ones proved, in separate but parallel developments, fertile working grounds for their local users; far from it. Those users travelled to libraries outside their own countries (as we have encountered, or will in the following pages: Thorkelin in the British Museum, Michel in the Bodleian, Grimm in Paris, Görres in Rome, and Hoffmann von Fallersleben in Vienna and Valenciennes). Their rediscoveries were part of a development that all of them in their different countries recognized as a joint, multinational concern. The contacts between them, whether amicable or competitive, were intense, and they were keenly aware of each other’s work. The epistolary network of Jacob Grimm (13,000 letters, Figure 4.3) casts a dense, far-flung web over all of Europe; it can be confidently said that it enmeshes everyone involved in such enterprises, if not directly, then at most at two degrees of separation. Anyone who was active in philology in the nineteenth century exchanged letters with Grimm or, failing that, with someone else who did.10

The intensity and spread of this network is deeply meaningful for our understanding of Europe as a unified intellectual space. The philologists were the last representatives of the old Europe-wide Republic of Learning. The modernization of the university system, with humanities faculties and historical and philological departments, was a development that took place all over Europe; so was the establishment of national academies, libraries and archives, along with the professionalization of whose who worked in all those new types of institutions. And while those working environments might be compartmentalized by state, the people working in them were in mutual contact, constantly exchanging information, aware of each other’s work. The fact that so many agents in a ‘cultivation of culture’ crop up in parallel forms in different countries is, then, not a matter of happenstance or parallel responses to similar circumstances: they are the systemic, Europe-wide manifestation of a transnational communicative network and a homogeneous intellectual space. Different though Europe’s states were in their governance and in their socio-economic states of development, the philologists and scholars, from Anders Sjögren in St Petersburg to Alexandre Herculano in Lisbon, were part of a single intellectual continuum.

The ‘cultivation of culture’, of which this new type of knowledge production forms part, is itself an important aspect of ‘Phase A’ of national movements as theorized by Miroslav Hroch: the phase of national consciousness-raising. The later phases (B and C) of those national movements – social demands and political activism – may pan out differently according to the local conditions of the various European societies, regions and countries. But unlike those later phases, Phase A is very strongly transnational. Musical, literary and artistic fashions spread, and so does scholarship and knowledge production. Ossian, Herder, Byron, Scott, Grimm: the influence of these names reaches far beyond their country of origin or their place of work. Nothing in this cultivation of culture takes place in national isolation.11

Literary Histories, National Identity

Ironically, the editions of national classics, supported though they were by a pan-European intellectual vogue, had a deeply nationalizing effect on their readership. Culture and literature were now seen as historical traditions carried, specifically, by the nation over the centuries. In some instances the nation-building effect was announced in so many words as a deliberate intent at the forefront of the philologists’ mind. The most famous example is the preface given by Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen to his edition of the Nibelungenlied (Reference Hagen1807). Von der Hagen was evidently trying to come to terms with a crisis: the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire and the Napoleonic hegemony over the German lands.

[I]n present-day Germany, torn by destructive tempests, the love of the language and literature of our virtuous ancestors is alive and active, and it seems as if people seek in the past and in its poetry what is so grievously declining today. And this need for comfort is the last remaining sign of the imperishable German character, which, raised above all servility, will sooner or later always break foreign bonds and, wiser and chastened, will retrieve its inherited nature and liberty.

…Nothing can afford a German heart more comfort and true edification than the most immortal of all heroic lays, which from long oblivion re-emerges in vital and rejuvenated form: the song of the Nibelungs, undoubtedly one of the greatest and most admirable works of all periods and nations, grown and matured wholly from German life and sensibility, and pre-eminent for its sublime perfection among the admirable remains of our long-forgotten national poetry – comparable to the colossal edifice of Erwin von Steinach [i.e. Strasbourg Cathedral]. No other lay can so move and grip a patriotic heart, delight and fortify it.

Twenty-five years later, the preface of Jan Frans Willems’s edition of the Flemish Reynard tale used the occasion to upbraid his countrymen for their adoption of French culture:

Our Flemish Reynard surpasses all other poems on that theme. … in a word, it is by far the best poem (Dante’s Divina commedia excepted) which has come down to us from the Middle Ages. And it is a Belgian one! And the Belgians know it not! And the editing of it was left to Germans! … May this, my edition of the more ancient part of Reynard the Fox, contribute to the revival of our once-cherished language, at a time when our country is being inundated by French trash!12

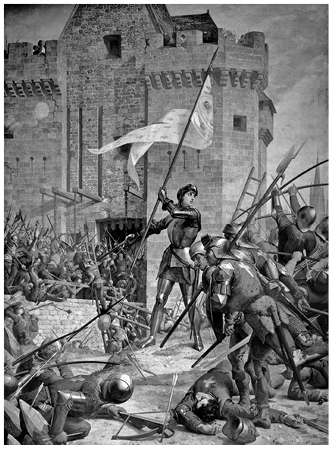

Ancient literature is now becoming a national heirloom, and an argument in the imperative to maintain the nation’s cultural continuity. France, in its ‘culture of defeat’ after 1871, gives the most heightened examples of this nationalization of the literary heritage. The Chanson de Roland, first published in the 1830s, gained fresh national symbolism in the traumatic events of 1870–1871. Much as Von der Hagen in 1807 had taken comfort from the death-defying heroism of the Nibelungen heroes, so too in 1870 Léon Gautier turned to the stalwart Roland, killed on the medieval battlefield of Roncesvalles while covering the army’s retreat to his ‘douce France’. Gautier wrote his preface

wrapped up in sadness and with tears in my eyes, during the siege of Paris, in those lugubrious hours when we might have thought that France was in its death-throes. And so what is the Roland? It is the tale of a great defeat for France, from which France has risen gloriously and which has been fully atoned for. What could be more topical? The defeat so far is the only part we have lived through, but this Roncesvalles of the nineteenth century has its own glory … It cannot be, really, that she should die, that France of the Chanson de Roland, which is still our France … where were they, those boastful invaders, when our Chanson was written? They roamed in savage bands through the gloom of nameless forests; all they knew was how to plunder and kill.

As Gautier wrote his preface, and during the siege of Paris, Charles Lenient taught a lecture course at the Sorbonne on ‘La poésie patriotique en France’, and Gaston Paris lectured at the Collège de France on ‘La Chanson de Roland et la nationalité française’.13 When in 1875 Gaston Paris and his father Paulin Paris founded the Ancient French Texts Society, its philological aims were also presented as a ‘national enterprise’:

The Société des anciens textes français is a national enterprise … it needs the support of all those who understand the importance of tradition, all those who realize that the strongest bond keeping a nation together is piety towards our ancestors, all those who are vigilant about the intellectual and scientific standing of our country amidst other peoples; all those who love, throughout all the centuries of its history, that douce France for which one could already die such a good death at Roncesvalles.14

‘Roncesvalles’ echoes through the period of French revanchism, 1871–1914, much as Nibelungentreue would haunt German history in the twentieth century. If we want to understand what made Churchill and Stalin commission cinematic recalls of Henry V and Alexander Nevsky, here are the origins of that national historicism.

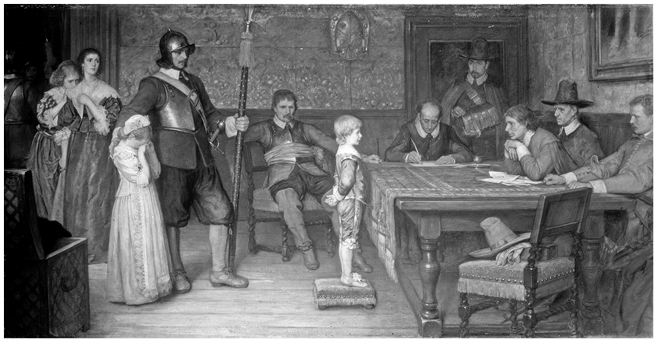

Entangled Roots

As the new philologists gradually professionalized into state-salaried archivists, librarians and professors (of history, philology, archaeology), they became civil servants of the state. The antiquaries had been gentlemen of leisure; the new professionals acquired not only a professional, academic work ethos but also a sense that their knowledge production was a service to the nation. When, in 1846 and 1847, Jacob Grimm called together two countrywide congresses of Germanisten (German philologists, including legal and cultural historians), the gathering showed how the new post-antiquarian university disciplines were now positioning themselves as a useful helpmeet to the nation’s identity. They manifested this with the same patriotic arguments that we have encountered in the later manifesto of the Society of Ancient French Texts: the importance of tradition and of ancestral piety, and the vigilant safeguarding of one’s country’s intellectual and scientific standing amidst other peoples. Concretely, the Germanisten proceedings revolved around an assertion that Schleswig-Holstein had always been, and should once again become, German; a call for the ancient Germanic liberty of trial by jury (an oblique dig at arbitrary monarchical government); and the need for a proper German dictionary. The 1846 meeting was held in St Paul’s church, Frankfurt; two years later, no fewer than thirty-one of the participating Germanisten would meet again in the same spot, this time as delegates of the 1848 Frankfurt National Assembly.15

Germany was in the forefront of the new philology, establishing benchmarks for all of Europe in many fields. The presiding genius was Jacob Grimm, together with his (slightly more withdrawn and amiable) brother Wilhelm. Nowadays known mainly as the collectors of fairy tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen, literally ‘Wonder Tales for Children and the Household’, 1812–1815), the Grimms were also the instigators of the huge lexicographical enterprise of the ‘German Dictionary’ (Deutsches Wörterbuch, 1852–1961) and collectors of German legends (Deutsche Sagen, 1816–1818). Jacob himself edited ancient German texts and legal customs, extrapolating from the latter a generalized ethnography of public mores and their enforcement (‘German Legal Antiquities’, Deutsche Rechtsaltertümer, 1828); we will encounter, further on, his German mythology and his history of the German language and its dialects (Geschichte der deutschen Sprache, 1848). The breadth of these interests recalls the antiquarians of yore, and indeed Grimm could be prone to flights of fancy in interpreting his material; but his data management was thorough and rigidly systematic. No amateur he: he was a legal scholar by training and had been a librarian in his first employment. That he was firmly part of the new comparative-historical paradigm is manifested triumphantly in his comparative grammar of the Germanic languages, the Deutsche Grammatik (1824–1836), in which he went as far as formulating linguistic ‘laws’ (regularities in historical consonantal shiftsFootnote *). It was the first time such ‘laws’/regularities had been observed in human culture rather than inanimate nature. Among fellow philologists, this gave Grimm a scientific stature comparable only to that of Newton. In addition, he was involved in momentous political crisis moments. When Jacob and Wilhelm were dismissed as professors at Göttingen University in 1837 for refusing to acquiesce in the arbitrary autocracy of the incoming King of Hanover, they became martyrs to the cause of academic freedom, and Jacob was a delegate in the Frankfurt National Assembly of 1848.16

The Grimm-style German ‘new philology’ inspired scholars in Spain and Portugal (Hermann Böhl de Faber and Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcellos). At Oxford, the Anglo-Saxonist Kemble and the Sanskritist Max Müller were Grimm adepts. Even French philology in France was inspired deeply by Grimm’s pupil Friedrich Diez, to the point that the manifesto of the Ancient French Texts Society complained of ‘Germany being the European country where ancient French texts are printed most’.17

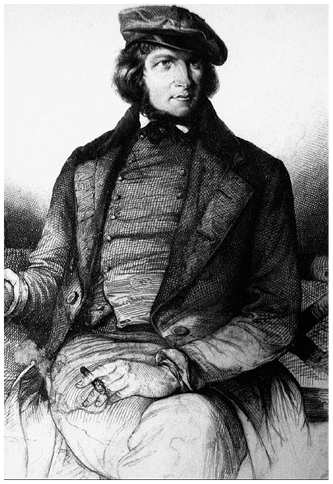

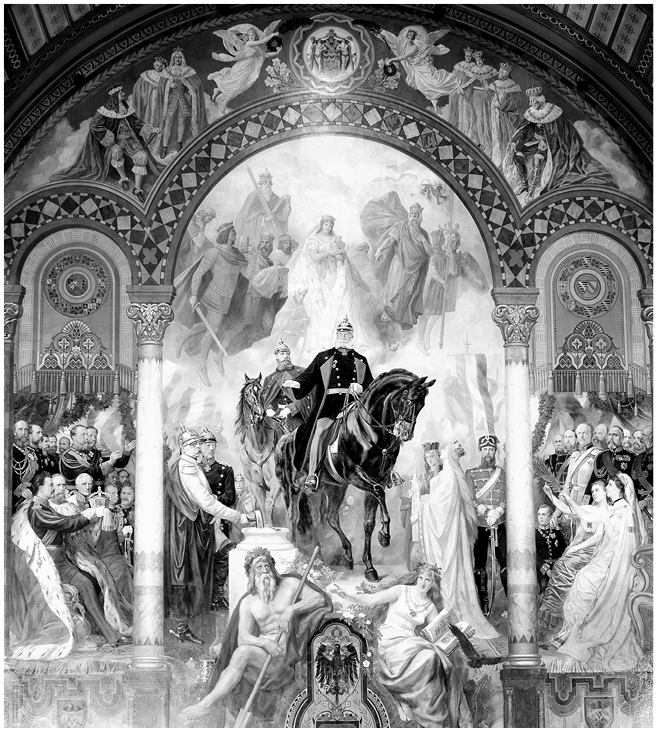

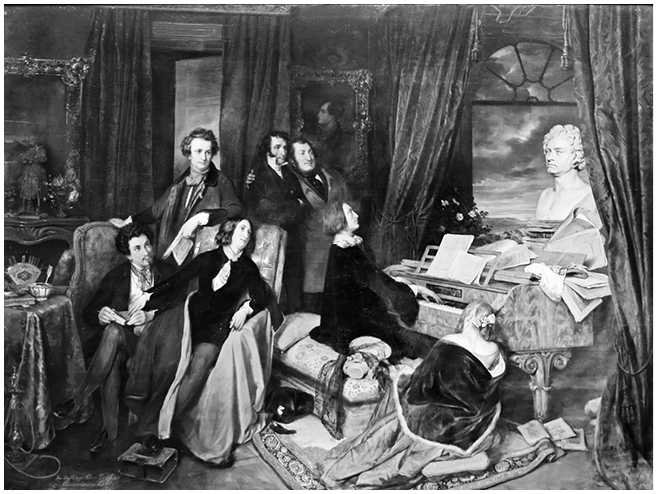

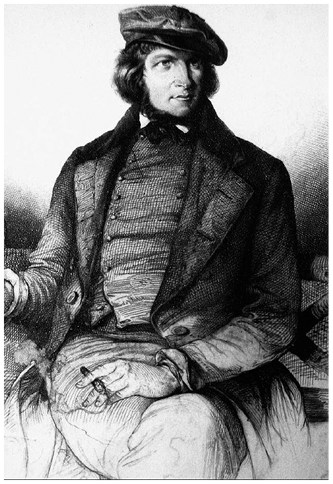

Also, Jan Frans Willems invoked Grimm when he chided Belgium for its neglect of its Flemish-language roots. Indeed, the ‘Flemish Movement’ – one of Europe’s best-documented national movements – leaned heavily on German intellectual aid in its cultural insurgency against the dominance of French. A stalwart supporter of the Flemish cause was the poet-philologist and political activist August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, a larger-than-life figure mainly known as the author of the ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ anthem (Figure 4.4).18 Hoffmann was a fervent adherent of the Grimm school of philology and made a name for himself as a canny investigator of archives and libraries (he edited two volumes of ancient German ‘treasure troves’, Fundgruben, published in 1830 and 1837). In the many places he visited on his philological quests, he invariably sought out kindred spirits who, like him, were inspired by the glories of the vernacular literary tradition. This made him a ‘networking’ mediator among the various national revival movements that these kindred spirits were involved in. A hub of these was formed around the Vienna librarian and philologist Jernej Kopitar. While on a visit there, Hoffmann joined the Stammtisch or regulars’ table at the inn where the Slovenian Kopitar gathered intellectuals from the Slavic minority populations of the Habsburg Empire – a typical instance of the intensive private and convivial networking among these Romantic scholars.19 While in Vienna, Hoffmann also got wind of the possible whereabouts of a long-lost medieval German manuscript – somewhere near Ghent, in Flanders, where Jan Frans Willems had edited the Flemish Reynard.

Figure 4.4 August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben in the garb of a nationally minded wandering student: Dürer-inspired hairstyle, beret, unstarched collar, tight waistcoat. The full portrait also shows a walking stick and a drinking gourd.

Hoffmann immediately hastened from Vienna to Ghent, in the process boarding one of the very first steam trains to run on the newly opened railroad north from Brussels. He and Willems then travelled from Ghent to the public library of Valenciennes, where the French authorities, who had closed down the ancient monastery of St Amand des Eaux, were rumoured to have lodged its collection of books and manuscripts. They hit the jackpot: what they retrieved was the long-lost ninth-century Ludwigslied, one of the most ancient poetic texts in vernacular German. Only a few months later, their edition of the manuscript appeared in print (Elnonensia, 1838).

Hoffmann was familiar with Flanders and its literary history; he had been editing ancient Flemish texts since 1833 in a series called Horae Belgicae. Indeed, it is to this German’s editorial work that Dutch and Flemish literature owe many of the first printed versions of their medieval heritage. But by 1838, when Hoffmann visited Ghent, the climate was shifting. We have seen how Jan Frans Willems in 1835 was already chafing at the pronounced francophilia of the newly independent Belgian state and the marginalization of Flemish culture in that state. Hoffmann was fêted by Willems in a convivial club of Flemish-minded intellectuals called, tellingly, De taal is gansch het volk – ‘The language is, entirely, the nation’ – and Hoffmann, impressionable and enthusiastic as ever, now started to support the Flemish emancipation cause with his accustomed fervour. That same year, he wrote a firebrand introduction to yet another text edition (Altniederländische Schaubühne, 1838), in which he vehemently denounced the fact that on his railway journey from Brussels, passing through Flemish territory, he had heard announcements only in French. His denunciation of the general retreat of Flemish before the hegemonic French language was a fervent endorsement for the emerging Flemish movement; though possibly it was also somewhat embarrassing.20

Hoffmann did not only feel solidarity with a marginalized language; as a nationalistic German, he felt a proprietorial paternalism towards it and wanted to place the small sister language under the protection and tutelage of the older brother. If Belgium wanted to have a bilingual regime with a metropolitan language alongside the local Flemish, he asked, why then should that metropolitan language be the alien French? Why should it not be, rather, the more closely related and more easily understood German? And he continues, in a remarkable mash-up of different variants of ‘German’ and Netherlandic:

Fleminglandish is a Niederdeutsch language and conveys just like Plattdeutsch a familiarity and understanding of High German (Hochdeutsch). If German Belgium were to give up its own language and literature, then the High German language would have a more natural, and therefore more justified claim than that non-German, French language. If at some future date the educated classes of German Belgium were to speak and write High German, and to that extent take part in the German-language literary production, then this would not be a great marvel, any more than that ever since the sixteenth century the Nether-Germans in Germany’s northern lands (the lower Rhine, Westphalia, Lower Saxony and on the hither shores of the Baltic Sea) speak and write High German, and add their intellectual cooperation to German literature as much as the inhabitants of the regions where Upland-German (Oberdeutsch) is spoken, even though Niederdeutsch has remained their native tongue.21

This tendency to fold the Low Countries into a greater German whole played itself out in other fields than mere linguistic confusion. Hoffmann had, indeed, looked on the Low Countries with an acquisitively greater-German eye since 1820; and he was the poet who in his ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ had proclaimed that his aspirational, beloved Germany should stretch ‘from the Meuse [i.e. Namur-Liège] to the Niemen [Königsberg], from the Belt [Kiel, Schleswig] to the Adige [southern Tyrol]’. That was put forward as a programme of popular unification and emancipation; but it also implied territorial expansionism at the cost of neighbouring states and linguistically mixed populations. In the event, the association with greater-German nationalism was to prove a mixed blessing for the Flemish movement. German nationalists supported Flanders as a bulwark against encroaching French culture and repeatedly (in 1848, and fatally in 1914 and 1940) made the Flemish cause their own. This meant that after 1918, Flemish activism was tainted with the notion of uncivically betraying, with the aid of the German military occupiers, their country, Belgium; and ever since 1944, the Flemish movement has carried the guilty burden of its wartime sympathy, and widespread collaboration, with the Nazis.22

There was one great irony in this. What Willems and Hoffman found in the Elnon manuscript in Valenciennes was not just the most ancient contemporary copy of a vernacular German poem but also the most ancient contemporary copy of a vernacular French poem: on the same page as the ‘Ludwigslied’, and written in the same hand, is the ancient French ‘Hymn to Saint Eulalie’. The nearby monastery of St Amand, where the manuscript was produced and was kept until the French Revolution, had been founded in Merovingian times in the transition zone between the German-speaking and the Latinizing branches of the Frankish tribes. At that period and in that area, proto-German and proto-French coexisted and intermingled. Their peaceful literary coexistence in this ninth-century manuscript is a quiet reproach to the growing national chauvinism of the nineteenth-century philologists. A century after the manuscript’s discovery, its home region, between Ghent and Valenciennes, was torn up by the French–German gash of the Western Front.

Contested Heritage

In providing the modern nation with its ‘own’ cultural heritage, the past was not so much rediscovered as reappropriated. That reappropriation was to a large extent anachronistic, since the materials claimed as a national heritage themselves dated from a prenational (feudal or even tribal) past. That one should feel proprietorial towards one’s heritage is to a certain extent understandable. Modern countries such as England and Egypt may cherish and feel stakeholders in the ancient monuments located on their soil, such as Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Giza; in that privileged sense of being uniquely associated with them it matters little that the builders of those monuments had no familiarity with the country’s modern inhabitants. But the literary heritage presented a problem. Manuscripts as ‘portable monuments’ were transnationally dispersed across libraries and discovered by a roaming band of philologists; and they were written in idioms that were the forerunners of a palette of various modern languages current in different countries.23 As a result, they could become contested among different appropriations. The successor traditions to these medieval texts had fanned out into groups of different nationalities, each of which felt that they, and they more than any other, were the true heirs.

Thus Thorkelin thought that the Beowulf text he had discovered was a Danish poem, for the action is located along the Saxon coastlands that were Danish territory around 1800; nearby coastal tribes that the poem mentions are the Frisians, Angles and Geats, all of them known to Danish antiquarians. Small wonder that Thorkelin presented Beowulf as ‘a Danish poem in the Anglo-Saxon dialect’. Beowulf was thereby placed under a double mortgage: a scholarly one (since Thorkelin’s version was error-ridden) and a political one (in that the text was claimed by German, Danish and English scholars as culturally theirs). It took decades of debate for the English view to become dominant: that the Angles and Saxons, having migrated across the North Sea, had become the tribal ancestors of England, and that Beowulf was an Old English poem recalling events from before the Anglo-Saxon migration. That debate was further muddied by German philologists who argued that, since the Saxons were a German tribe, this was in fact a German poem casting light on the mores of the Saxon contemporaries of Charlemagne. In 1839 and 1859, editions appeared calling Beowulf Das älteste deutsche, in angelsächsischer Mundart erhaltene Heldengedicht and Das älteste deutsche Epos. The subtitle of the 1839 edition (by Heinrich Leo) offers full disclosure as to its approach: ‘The most ancient German heroic poem, in the Anglo-Saxon dialect, considered in its contents and in its relations to history and mythology: A contribution to the history of the ancient German mentality’. The preface to the 1859 edition (by Karl Simrock, a Grimm adept) voiced sentiments such as this: ‘As has already been pointed out, the Beowulf, though handed down in Anglo-Saxon, is in its foundations a German poem. In addition, the following comments clarify that its plot-line (Mythus) is a German one, which has left many traces amongst us. All this increased my wish to reappropriate this poem into our language.’ Simrock hopes ‘to bridge a thousand-year old division and to renew for this poem, that emigrated away along with the Angles and Saxons, its native domicile [Heimatrecht] amongst us.’ It is no coincidence that these editions appeared at a time when a strenuous German–Danish struggle was underway over ownership of Schleswig-Holstein – including precisely the coastlands where Beowulf was set.24

Within England, the assertion of Beowulf’s Englishness did much to strengthen a sense of Anglo-Saxon roots, rejecting the country’s other cultural source traditions – Celtic and Norman French. The marriage of Victoria, from the Hanover dynasty, to Albert, Prince of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, symbolically enshrined this sense of Saxon–Germanic affinity at the apex of society. Intellectuals such as Carlyle vociferously expressed a ‘Saxonism’ that dominated the mid-century. It was even projected across the Atlantic Ocean, where the ideal type of the WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) shored up the ideology of manifest destiny and a sense of a westward-expanding Anglo-Saxon world empire. The echoes of that ideology would inform Winston Churchill’s notion of the north Atlantic community of ‘English-speaking peoples’.25