What a number of Novels are continually poured from the prolific press …!

Never, surely, was there an age in which novels were more generally read than the present.

[I]t is apparent, that novel reading, under proper restrictions, is not injurious to the morals; on the contrary, both amusing and instructive: the only danger is that of running into excess.

In a letter to the editor of the Universal Magazine in 1793, the pseudonymous ‘Lucius’ held forth on novels at some length.4 Bemoaning the fact that ‘a taste for reading the most superficial novels is … on the increase’, he specifically decried ‘that collection of trash incessantly poured out from our professed manufactories, where fresh novels are advertised for in quantities!’5 While Lucius is considerably more alarmist about the dangers of novel-reading than the author of my final epigraph, his preoccupation with volume, (im)moderation, popularity, and prolificity is shared by all of the epigraph writers and, indeed, echoes across countless other discussions of novels and novel-reading in the Romantic period. As this book demonstrates, the belief that there were simply too many novels, that their proliferation was threatening (economically, morally, physically), and that their numbers necessitated an ongoing process of categorizing, managing, and evaluating them pervaded the Romantic period. To understand the development of the novel around the turn of the nineteenth century, I will argue in these pages, thus requires us both to acknowledge and to resist the centrality of this discourse, understanding how it shaped the period’s fiction and how it still urges us, so often successfully, to replicate its historical hierarchies and structures of value.

Discussions of fiction from this period almost invariably describe it in terms that emphasize its sheer quantity. Romantic novels, in such accounts, aren’t written or crafted, they are churned out, poured forth in torrents or mass-produced; they don’t simply appear but swarm and deluge, springing up like mushrooms or many-headed hydras.6 Both novelists and presses are described as prolific in a way that interferes alarmingly with readerly agency: readers, we are told, do not seek out these novels of their own volition, but are flooded with them, addicted to them, or bewildered by them. ‘[T]he larger our libraries are the greater the impossibility of knowing what they consist of’, as another contributor to the Lady’s Magazine declared in 1789.7 While the long novel was certainly nothing new in England by the end of the eighteenth century, now critics complained that every novel, however thin the plot, ran into three, five, or even seven thick volumes, sometimes because of the author’s ‘superfluous garrulity’,8 sometimes through the use of deplorable stratagems such as page layouts with ‘tremendous breadth of margin’,9 which helped to populate those increasingly large libraries by spreading a small number of words into a great number of volumes. As the range of descriptions listed here suggests, anxiety about literary overproduction may begin with complaints about the numbers of books published, but it rapidly extends into discussions of narrative length, readerly attention span, the appetite of the reading public for new fiction, and even the motivations of book publishers. Both the material characteristics of book production and the emotional implications of widespread reading are portrayed as underlying reasons for, but also inevitable outcomes of, rising numbers of novels on the market.

A sense of literary overload is obviously neither unique to Romantic-era England nor inspired exclusively by novels. It has always been possible for an individual reader to feel overwhelmed (or for undesirable authors to seem too numerous), and the advent of early modern printing technologies made such feelings all the more frequent. The seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, in particular, saw an increase in printed material – and complaints about its volume – that in many ways foreshadow the end-of-century characterizations I document here.10 Alexander Pope’s satirical poem The Dunciad, for instance, famously mocks the age’s ‘groaning shelves’ and skewers both authorial prolixity and the sheer mass of printed matter with references to ‘whole pile[s]’ of books and volumes ‘of amplest size’.11 Throughout the poem, Pope returns to some recurrent themes: the overproduction of printed material, the poor quality of much literary work, and the grossly commercial motivations of authors, concerns echoed by other writers and critics of the 1720s and 1730s. These refrains continued into the mid-eighteenth century, as scholars including Christina Lupton have documented.12 But the later eighteenth century, particularly the years after 1780, saw a surge in printed material that outpaced all previous growth, and the complaints about excess that accompanied this change both intensified and multiplied.13 By the end of the eighteenth century, a contemporary writer could describe books with reasonable justification as ‘heaped upon the world, not in small quantities, but in multitudes’.14 David Higgins pithily describes this period as ‘an era marked by an exponential increase in the availability of printed matter’; as Andrew Piper has argued, this shift is fundamental to the literary and philosophical developments of the early nineteenth century: ‘Romanticism is what happens when there are suddenly a great deal more books to read, when indeed there are too many books to read.’15

Though all sorts of printed materials were available in newly overwhelming quantities during this time, in this book I explore the ways that the novel was specifically susceptible to critique on these grounds.16 As a relatively new genre, a seemingly extraneous and unnecessary genre (always at risk of being perceived as shameful entertainer rather than beneficial educator), and a genre strongly associated with ‘undesirable’ literary developments including professional women authors and working-class literacy, it was the novel, as scholars including Melissa Sodeman, Ina Ferris, and Emma Clery have suggested, that was seen as both a primary symptom and a cause of this new age of overwhelming abundance.17 And while Romantic critiques of the novel on these grounds often take the form of vague and rhetorically loaded complaints, like Lucius’s, they do have a clear bibliographical basis: as the data in The English Novel (2000) so compellingly demonstrates, even as rates of literacy among English readers increased at the end of the eighteenth century, so too – dramatically – did the number of novels on the market.18 The story of this rise is inseparable from the history of one publishing house, the Minerva Press, which operated in London between 1790 and 1820.

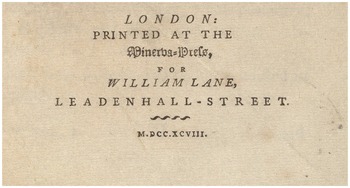

The Minerva Press has a complicated relationship to the Romantic era’s perceptions of fictional overproduction. The Minerva’s founder, William Lane, entered the London book trade in the 1770s, selling books from his father’s poultry shop before starting his own business.19 In 1790, he founded the Minerva Press, quickly adopting a distinctive black-letter imprint that distinguished his title pages from those of other publishers (see Figure 1).20

Figure 1 Detail, title page, Phedora, vol. I, *EC8 C3818 798p.

Located in the commercial environs of Leadenhall Street (also home to the East India Company) rather than the more traditional book-selling locations around St Paul’s Churchyard and the West End,21 the Press invited mockery for both its literary pretensions and its orientation towards profit, a conjunction epitomized by the infamous golden statue of Minerva that Lane hung over the door of his premises.22 There is a strong air of snobbery around much of the criticism directed at the Minerva Press: Lane’s humble beginnings were a target of derision, as were the untalented women said to read and write the Press’s novels.23 Writing in 1815, W. H. Ireland managed to mock both Lane’s working-class past and the intellect of his present readers with the quip: ‘instead of Minerva, a goose should have been the designation of its far-famed press’.24 With its dual implications of an ungentlemanly proximity to poultry shops and the unearned wealth produced by the goose that laid the golden egg, the insult simultaneously brings to mind familiar descriptions of young women readers as ‘silly geese’ – certainly not the images Lane’s ambitious imprint hoped to evoke.

The press also attracted attention for another reason: within a few years, it was producing more novels than any other publisher in England. In part this success was due to Lane’s savvy business model, which combined a publishing house with multiple in-house printing presses and a large and famous circulating library, not to mention a newspaper and a thriving mail-order business for ready-made small libraries.25 The Minerva Press published six novels in its first year, and twenty-two the year after, rapidly picking up momentum over the course of the decade.26 By 1800, it was clear that the Minerva Press was out-producing every other source of novels in the market, a dominance that would characterize its thirty-year lifespan, although the Press’s actual output rose and fell substantially in different years during this period.27 Bibliographic research tells us that Lane, his successor A. K. Newman, and the Minerva Press published around 600 novels between 1790 and 1820, amounting to more than a quarter of all the new novels in England, and more than five times as many as any other single publisher during that time period.28 This feat is remarkable both for being unprecedented in the history of the English novel and for the rapidity with which the Press increased its production and relative market share. While in the entirety of the 1770s barely 300 novels were published in England, by the 1790s that number had more than doubled, and much of that growth is attributable to the Minerva.29 It is unsurprising, then, that the Minerva Press should have been strongly associated with the Romantic age’s fictional excesses: in many ways, it produced them.

The connection between the Minerva Press and Romantic views on novels and novel-reading is, however, more complicated than a simple numerical statement of the press’s vast output can explain. Even as the Minerva increased the sheer number of new novels, both through its own publications and by spurring competition in other publishers, it also came to be associated with everything about novels that society most feared and rejected. Its novels were characterized, variously, as lurid, boring, and derivative; sensational, unoriginal, and mass-produced; addictive, poorly written, and corrupting. The enormous Minerva library, similarly, served as a focal point for societal anxieties about circulating libraries (and their patrons) in general. All the fears about fiction outlined above, in other words, attached in particular to the infamous Minerva novel; indeed, Michael Gamer has argued that the Minerva ‘functioned at the turn of the nineteenth century as a synecdoche, as a way for critical writers to embody and isolate undesirable changes throughout the publishing industry’.30

The centrality of the rhetoric of fictional overload to this historical moment, and its ties to the Minerva Press, has been documented by many scholars of the period, particularly those working on issues of gender and literary genre. Ina Ferris, for instance, has explored how metaphors of multiplication and growth were used to condemn popular fiction by women.31 Citing the critic John Wilson Croker’s derisive reference to ‘the thousand-and-one volumes with which the Minerva press inundates the shelves of circulating libraries’, Ferris argues that ‘over and over again, the … novel is depicted as stamped out by machines, produced not by authors but by printing presses’.32 She continues, ‘Ordinary novels appear in “hordes”, “swarms”, and “shoals” – always plural and undifferentiated’, pointing out that ‘critical discourse responded to the ordinary novel as a signifier of potentially uncontrollable, destructive energy’.33 The threat posed to society by the Minerva Press novel and its ilk is at once immediate and vague; these are novels that crash upon the public like a wave, exceeding demand and resisting categorization. The increasing number of women writers in the late eighteenth century, and the association between certain literary genres and women readers, plays an important role in the era’s discourses of excess, as Ferris demonstrates, and as studies of reviewing – an occupation that often pitted male critics against women novelists – have shown.34 However, concerns about literary excess and growth were by no means limited to literary pursuits perceived as ‘feminine’. Novels of all types and by many different authors were characterized in this way, a conceptual approach that perpetuated the adversarial relationship between authors and reviewers, but also set the stage for later critical approaches to the novel. ‘Uncontrollable’ novels seem to justify ongoing attempts to control them; moreover, though, this way of thinking about fiction is often in fact a way to avoid thinking about (certain kinds of) fiction. Both the discourse of literary excess and its realities are in part responsible for the body of Romantic texts that, in Lee Erickson’s memorable formulation, ‘no one has been willing to read for a long time and … only a few scholars today are even willing to read about’.35 Excess offers critics a way to describe without describing and to dismiss without reading; conversely, however, as I show in this book, the dominance of the narrative that novels were self-propagating and numerous has specific effects on the ways that novels were written and received.

Inevitably, perceived problems with the Romantic novel were seen as both a product of and a threat to the habits of Romantic readers. As David Higgins argues, ‘Pope’s [early eighteenth-century] concern with the multiplication of bad writers became in the nineteenth century a concern with the multiplication of bad readers.’36 It was, thus, not only the novels themselves that were conceptualized as a terrifyingly large and unruly group. Describing the expanding demand for popular fiction in this period, Emma Clery writes, ‘With the tentacles of the bookselling industry now reaching into the previously untouched fastnesses of the provinces, the market for novels was made strange. Was there any limit to its appetite? How could the wishes of this prodigy be anticipated?’37 The mutually reinforcing relationship between seemingly self-reproducing texts and uncontrollably ravenous readers – and the prodigious market created by this relationship – has long been understood as a crucial context for Gothic fiction in particular. James Watt suggests that ‘the “Gothic” romances published by a press such as William Lane’s generated anxiety primarily because of their quantity, their self-proclaimed commodity status, and – ultimately – their popularity’.38 And Gamer argues that gothic writing, including that published by the Minerva Press, was ‘blamed for various changes in literary production and consumption: perceived shifts from quality to quantity; originality to mass-production; and the text-as-work to the text-as-commodity’.39

The commercial nature of the Minerva novel was clearly an important part of the equation; in addition to offering a convenient way to deny it any artistic merit, conceiving of the novel as a ‘commodity’ explains how it could be understood as at once overproduced and ungovernably desired. These characterizations had broad ramifications, as Melissa Sodeman, drawing attention to the frequent unflattering comparisons between popular novels and ‘mechanically produced goods’, points out. She argues that quantity negatively affected the way many people thought about the novel genre itself: ‘For many eighteenth-century commentators … the sheer number of new novels – most of which were unabashedly sentimental, gothic, or some amalgamation of the two – seemed to have depleted the genre’s possibilities.’40 These perceptions have had lasting critical effects; as Deidre Lynch puts it, this is a ‘literary period frequently dismissed’ as a time ‘when novels’ numerical increase led to their qualitative decline’.41 The inverse relationship between numbers and status is self-perpetuating: the commodified novel must be bad, because it is mass-produced; the numerous novel must be a commodity, because it is written to meet overwhelming demand. Ideas about fictional production and reception are entangled with qualitative judgements about the novel, with fundamental concerns about oversupply and uncontrollability underpinning them all.

If Romantic novels are frequently described in terms of their proliferation, the contents of these numerous volumes have similarly been characterized as undesirably multiplicative. Edward Jacobs has suggested, in a discussion of the ways that circulating library conventions contributed to the development of the gothic genre, that ‘the commonplace complaint of eighteenth-century critics that Gothics were mere “manufacture” underscores the fact that Gothics reproduced an unusually stable set of conventions in an unprecedented number of texts’.42 Accusations of unoriginality, derivative plots, and downright plagiarism abound in the period’s criticism.43 Elizabeth Neiman ties these critiques to the novel’s proliferation, pointing to ‘the idea that because they are formulaic, circulating-library novels practically self-reproduce’.44 As Jacobs’s discussion of ‘manufacture’, Ferris’s reference to novels ‘stamped out by machines’, and Sodeman’s ‘mechanically produced goods’ suggest, these claims are often governed by metaphors of automated production, which deny either talent or authorial volition to novel-writers. Aesthetic standards are subordinated in such accounts to the demands of novel-production on a massive scale.

All these discussions, in different ways, show the Romantic period’s preoccupation with literary quantity, and the power the many metaphors used to characterize the age’s fiction had (and indeed, still have) to diminish and dismiss the works to which they are applied. They reveal how common anxieties about reading and literature have been mapped onto ideas about growth, volume, and scale, and hint at the clear rhetorical connections between literary production and other kinds of industrial production in flux at the turn of the nineteenth century.45 Moreover, as the examples above suggest, all novels in such a crowded and newly industrial milieu might potentially be deemed dangerous or superfluous, but some are much more likely to be the targets of such accusations than others. Concerns about overproduction of fiction thus often turn out, upon closer inspection, to be concerns about gender, ethics, or prestige; conversely, discussions about the aesthetic qualities or moral dangers of the Romantic novel frequently shade into debates about such works’ length, size, or print run.

***

This book is an attempt to grapple seriously with the widespread, stereotypical, even formulaic critiques of the novel in the years around 1800, to understand the basis for these negative views, but also, more crucially, to explore the underlying beliefs about the novel they reveal. These shifting beliefs, as these pages demonstrate, generated new ways of writing and thinking about fiction. Rather than accepting dismissive complaints about poorly written popular fiction, women’s fiction, gothic fiction, or sentimental fiction at face value, or attempting to recuperate individual works or genres through extended close reading, I develop a critical framework that re-evaluates the undesirable multiplicity and largeness of the Romantic novel. I examine how pervasive ideas about overflowing shelves and overextended plot lines – not to mention the real (albeit often exaggerated) presence of these phenomena in readers’ lives – influence the style of novels written during this period, inspire new ways of imagining the novel’s temporality, and lead to an increased emphasis on the novel’s physical qualities and material presence. This account does not necessarily seek to challenge the stereotype that many popular novelists of this period were at least as motivated by commercial success as by artistic idealism, but it demonstrates that the conditions in which these novels were written, published, and read did have real effects on their aesthetic qualities.

The starting point for the particular negotiations I outline is the widespread claim by contemporaries that the field of fiction is too large and that parameters must be set to exclude some parts of it from view.46 But, as I also show, this persistent assertion is inseparable from a whole cluster of other debates about fiction, its value, and its legacies. To disentangle and trace these varied threads, I begin with a consideration of one key term, frequently used in contemporary discussions of fiction: excess. As I will suggest here, this term not only highlights the interrelatedness of physical and emotional, qualitative and quantitative assessments of the novel that I have outlined above, but also calls attention to the overlapping language found in both discussions of fiction and debates surrounding other economic and cultural controversies of the period. Excess, in its simplest sense, marks the fluid boundary between just enough and too much, between abundance and overload. Like the words ‘trash’ and ‘waste’ (with which it is sometimes used interchangeably), excess can be used to signal worthlessness, disposability, or repugnance, and, like these terms, it can be highly subjective.47 Unlike these related concepts, however, excess is strongly tied to both volume and value: while trash can often be identified as such even in isolation, and waste implies a discarded by-product, ‘excess’ indicates that some part of the thing being discussed is admirable or desirable, and only the amount that exceeds desire or necessity is unwanted. In other words, the negative concept – excess – implies, even requires, the existence of a positive sufficiency. While some commentators, like Lucius from the Universal Magazine, were ready to relegate novels en masse to the category of ‘trash’, most argued that some, even many, novels were valuable and worthwhile; thus, handling their numbers was merely a matter of identifying where that line between enough and too much might fall. It is this fragile boundary that critics and supporters of the novel alike exploit, whether by identifying entire groups of novels as superfluous or consciously reframing excess as plenitude.

Outside the realm of fiction, Romantic commentators frequently used terms like ‘excess’ or ‘excessive’ in the context of ongoing debates about scarcity and worth. Thomas Malthus’s 1798 treatise An Essay on the Principle of Population, perhaps most alarmingly, outlined the catastrophic future in store for a world in which the population outpaced global resources.48 For Malthus, distinguishing between a sustainable sufficiency and a dangerous ‘excess of population’ was quite literally a matter of life and death.49 Crucially, an overgrowth of population was portrayed as something that would gather its own momentum, reproducing out of control as soon as it passed the tipping point. The Monthly Review, looking back at two decades of Malthus’s influence, summed up his argument: ‘population ha[s] a tendency to increase much more rapidly than the means of subsistence’, and ‘powerful checks’ are thus required to maintain equilibrium, lest more drastic measures be required.50 The threat of unstoppable and dangerous proliferation resembles that so often invoked in contemporary discussions of novels, with critics assuming the burden of warning against and averting such growth. As we will see, fears about both self-perpetuating reproduction and competition for scarce resources were mobilized in discussions of fiction as a means of warning against fictional overproduction and justifying the necessity of measures to ‘check’ this growth. There are obvious limitations to the metaphorical comparison between Malthusian excess and that to be found between book covers: the life-or-death consequences of a scarcity of natural resources have no real parallel in the publishing world. Yet the hyperbole such a metaphor invited – and, as I discuss below, there was no shortage of apocalyptic metaphors when it came to novels – was clearly convenient to the commentators who warned of dangerously teetering stacks of novels, bewailed the scarcity of their limited reading time, or worried that the oversupply of novels would endanger their authorial survival by increasing the competition for increasingly scarce publishing resources. Romantic authors from William Godwin to Lord Byron (themselves both frequent commentators on the current state of publishing) engaged with and satirically cited Malthusian ideas, but the connection between his work and the literary scene is perhaps most explicitly articulated by a later scholar, P. P. Howe, who, in a 1912 English Review essay on ‘Malthus and the Publishing Trade,’ declared: ‘In the present over-populated state of the book-world – which none can be found to deny and few not to deplore – it is surprising that … no one should have suggested that simple remedy, a repression of the natural increase of literary population.’51 Indeed, the Romantic Age abounds with numerous examples of attempts at such ‘repression’, enacted most famously by reviewers but also by publishers and would-be authors themselves.

The late 1790s also saw ‘excess’ invoked in the financial arena, with the institution of the Bank Restriction Act in 1797.52 Decoupling paper currency from gold and silver coinage, this measure, designed to address the financial crises brought on by the ongoing conflicts with France, raised fears about unchecked proliferation of paper banknotes, and the proportionate decrease in their value. As the Analytical Review wrote in September of that year, as the ‘quantity of money [is] thus increased, it’s [sic] value is diminished’.53 Indeed, the article warns, the overproduction of banknotes risks their worth ‘sinking almost to no value at all’.54 As in Malthus’s strictures on population, critics of this system proposed various means of restricting the growth of paper currency; checking volume is portrayed as a direct means of preserving value. The Analytical Review cites a proposal to ‘limit the existence and circulation of this government paper’ if its ‘quantity became excessive’55 and notes that paper’s functionality as currency is entirely dependent on ‘if it’s [sic] quantity could be limited’. ‘This, however’, the author continues, ‘appears to us to be absolutely impossible.’56 As with discussions of novels, debates like these fail to clarify how a determination of ‘excessive quantity’ could be made, and by whom.

Fiction too is often described in terms of an inversely proportional relationship between volume and value, with control over the former – however impossible this may be – necessary to secure the latter. Paper itself provides a symbolic link between these two debates: books and banknotes are both physically made of paper, and this specific materiality, in both realms, becomes a way of ascribing or denying value. Paper can be imbued with the ideas in a book or the worth of a banknote; as soon as belief in either system is withdrawn, however, paper abruptly transforms back into its flimsy and transient self. An accusation of superfluity or oversupply, in other words, reduces book and bill alike to their physical form, withdrawing them from the symbolic systems that grant their legitimacy.

What makes ‘excess’ an especially resonant term for thinking about Romantic fiction, finally, is the way that contemporary use of the word slides so easily between material and emotional meanings, between physical presence and personal behaviour. In his dictionary, Samuel Johnson’s first definition for ‘excess’ is relatively concrete: ‘more than enough; superfluity’.57 Such a description could be, and was, used to describe sheer numbers of authors, readers, and novels, as when a writer in the Metropolitan magazine, reflecting on the first decades of the nineteenth century, complained that its ‘literature … is overladen with books and with authors to a singular excess’.58 Johnson’s list of meanings for the word, however, rapidly moves to a series of definitions that concern feelings and actions rather than numbers: ‘exuberance’, ‘intemperance’, ‘violence of passion’, and ‘transgression of due limits’. Contemporary accounts of fiction and fiction-reading reveal a similar slippage of meanings – novels aren’t just physically numerous, but emotionally over-the-top; reading and writing aren’t neutral processes but passionate, intemperate, and even transgressive behaviours. Novels are portrayed as emotionally overheated, overflowing with dangerous sensibility, and their physical proliferation is thus rhetorically tied to a rise in these kinds of feelings and behaviours, particularly in women.59

Numerous publications from this time joined the Lady’s Monthly Museum in warning women against ‘an excess of sensibility’, relating cautionary examples of tragedies resulting from ‘excessive sorrow’ or overweening passion.60 These dangerous emotions were often explicitly blamed on fiction; in a particularly dramatic example from 1793, the Weekly Entertainer argued that ‘The pernicious tendency of [novels and romances] cannot, I am afraid, be doubted.… [I]n certain situations of despair and agony, if a man or woman of sensibility, were to meet with the pathetic descriptions of fictitious writing, it might have a tendency to heighten the despair and drive them on to self-slaughter.’61 Priscilla Wakefield, in her popular didactic text Mental Improvement (1794), put it clearly: condemning over-emotional language, she declared, ‘Such excess of speech is to be expected from novel and romance readers, but are ill suited to a woman of good sense and propriety of manners.’62 Gothic and sentimental novels, in particular, were associated with this kind of extreme affective response – in Stephen Ahern’s phrase, ‘distinguished by a penchant for emotional and rhetorical excess’ – even as they were simultaneously portrayed as physically multiplicative.63

Emotional extremes were not limited to sentimental women, either: in the 1790s the term surfaces with alarming frequency in descriptions of the French Revolution, with the behaviour of enraged mobs described in lurid terms – ‘the excesses of the most sanguinary people on earth’ – by conservative commentators.64 While these mobs, for obvious reasons, were not generally described as reading novels while engaged in violence, the perceived link between fiction and the spread of dangerous, revolutionary ideas has been amply established in scholarship on British responses to the French Revolution.65 Novels spread ideas, and ideas spread feelings; if those ideas were dangerous, then towering stacks of undesirable novels easily might become crowds of ungovernable citizens, in the popular imagination at least. Novels, in other words, were not only produced in excess; they produced excess (of speech, of emotion, of behaviour) in others. This rhetorical slippage between physical and emotional connotations makes ‘excess’ an unstable critical term, but its very instability usefully reveals the conveniently overlapping accusations directed against popular fiction and those who read, wrote, and published it.

A central aim of this book, then, is to explore what happens to our picture of the Romantic novel when we focus directly on the idea of excess – or, more specifically, on the novels, genres, and publishers that this concept was so frequently used to dismiss. We can refuse, in other words, both the easy repudiation and the unexamined slippage of terms that ‘excess’ invites, instead considering how the material circumstances of book production in this era, and ongoing concerns about uncontrolled and uncontrollable fictions, shaped the development of fiction itself. Looking closely at the specific motivations and characteristics of many Minerva Press novels, I argue here, reveals that many, perhaps all, Romantic novels engage with similar questions of relevance and self-differentiation. Centring those novels generally accused of superfluity, instead of relegating them to the margins or the background of an argument, reveals their importance: if the period’s ‘innumerable’ novels form a vast and overwhelming body, this body exerts a quasi-gravitational pull on everything around it – even novels that resist assimilation follow orbits shaped by the mass of their forgotten brethren.66 In Elizabeth Neiman’s new work on the Minerva Press, she explores one way this shaping process occurred, illuminating not only the ‘actively collaborative model of authorship’ practiced by Minerva novelists but, crucially, the influence this model had on Romantic theories of poetic genius.67 Romantic Fiction and Literary Excess in the Minerva Press Era traces the press’s influence in a different direction, but I am no less committed to the argument that the many, many novels associated with the Minerva Press and other popular publishers exert a powerful force on other literary works of the age.

To identify excess, as a critic, is to dismiss and to disengage. The designation itself justifies, even requires, a disdainful refusal to spend further time engaging with the details of the superfluous text. But the excesses of the Romantic novel are not so easily banished. The maligned or banished novel has a metaphorical presence, but also an actual weight and heft; those hordes and swarms threaten, I argue, because they are tied, however hyperbolically, to the actual material presence of books in the world. This exploration of overproduction and its literary repercussions is, then, ultimately an account of the ties between metaphor and material reality, between bibliographic and narrative growth, between a book-historical understanding of print production and the varied ways that authors conceptualized their place within the print marketplace. All the authors in this book, whether they wrote for Lane or a more prestigious publisher like Longman, sold well or poorly, or are now canonical or forgotten, engaged with changing beliefs about fiction through acts of resistance, re-orientation and, ultimately, acknowledgement of the political, literary, and financial possibilities presented by the novel’s new prominence. It is in this sense that I think we can justifiably call the years around the turn of the nineteenth century the ‘Minerva Press Era’: the Minerva was far from the only publisher operational during this time, but the literary pressures and problems to which it contributed, and which it symbolically exemplified, affected all novel-writers and their works.

In the chapters that follow, I trace the literary effects of the novel’s seemingly uncontrollable growth and influence across three main registers: materiality, temporality, and style. The novel’s proliferation, clearly, is entangled with considerations about its physical form. The relationship can be seen quite literally in the development of new packaging and sales strategies designed to distinguish one text from another – or to remind a reader of the connections between one novel and its many fellows – but also can be seen metaphorically, in the way that the novel’s materiality was conceived of in relationship to other material objects. The novel’s symbolic place within the changing consumer landscape evolved in tandem with its increasing availability from circulating libraries and shops, raising questions about both the labour required to produce novels and the likely fate of the piles of volumes thus created. Questions about the novel’s future lead directly to the temporal dimension of fictional development I explore in this book. A sense of large or even unlimited supply and endless competition meant that the time it took to read (or write) a novel needed to be conceptualized differently, an issue complicated by multi-volume novels that circulated different parts of a single story separately. Moreover, large numbers brought questions of ongoing relevance to the fore. How long was a novel interesting or important? Ought it to be fleeting or persistent, ephemeral or eternal? Novelists, their readers, and their critics debated whether fiction was best understood in terms of its relationship to changing fashions, or whether its status, either as art or as a source of moral education, required a more timeless and enduring standard of evaluation. A sense of fictional multiplicity, finally, drove authorial experimentation with new narrative perspectives and stylistic similarities, deliberately rippling across numerous volumes, and coalescing into recognizable genres designed to appeal to broad-based readerships.

In tracing the complicated ramifications of (over)abundance in each of these three registers, I also show how interconnected they are. To take just two examples, it is impossible to understand the gothic genre – most often discussed in terms of narrative, plot, or style – or A. K. Newman’s new Minerva bindings, a more strictly material or bibliographical concern, without also considering closely related issues including the timing and duration of new literary fashions and the relationship between literary genre and literary advertising. While research on Romantic novels often focuses either on their internal qualities (genre, narrative, or the development of free indirect discourse, for instance) or on their bibliographical characteristics, my analysis of fictional growth and metaphors of excess clearly shows that for contemporary commentators, production, reception, and style were crucially entwined.

***

Christina Lupton has argued compellingly that British authors of the mid-eighteenth century show ‘a reiterative brand of self-consciousness for their work that points with remarkable candor to the actual conditions and materials of their writing’.68 She offers as one example an excerpt from the preface to a 1779 novel, Columella; or, The Distressed Anchoret, which runs in much the same vein as my epigraphs at this introduction’s beginning: ‘The Public is overwhelmed already with books of every kind, but especially with tales and novels.’69 As this quotation continues, however, it takes a more unexpected turn: ‘I begin to think, that in time the world, in a literal sense, will not be able to contain the books that shall be written.’70 Both the self-consciousness and the links between materiality and textual mediation that Lupton documents at mid-century continue to be evident in many novels well into the nineteenth century. What resonates most with my own discussion of the Romantic novel is Columella’s insistence on the ‘overwhelm[ing]’ presence of fiction in the public sphere and the characterization of this presence in a specifically material, if highly exaggerated, way. After speculating that the number of novels will soon exceed the globe’s available space for them, the novelist suggests an even more apocalyptic scenario:

a droll friend of mine imagines, that one reason why this terrestrial globe will be destroyed by fire, is, that a general conflagration will more effectually consume the infinite heaps of learned lumber (with which it was foreseen our libraries would be stored after the invention of printing) than any inundation, earthquake, or partial volcano whatsoever, could possibly do.71

There is a characteristic insouciance to this passage, which – even as it appears in the pages of a novel – invites the reader to envision the world burning, more thoroughly destroyed by ‘infinite heaps’ of highly flammable novels than by flood or volcano. Novels are a force to be reckoned with here; add a single match and even earthquakes and burning lava pale in comparison. (Apocalyptic visions of death-by-novel, however hyperbolic they may seem, were rather standard fare; in 1790 a reviewer claimed that novels ‘cover the shelves of our circulating libraries, as locusts crowd the fields of Asia’,72 adding ‘plague of locusts’ to the biblically torrential or conflagratory dangers posed by the unchecked proliferation of novels.) Not all such invocations of materiality are so impressive, however, as returning to ‘Lucius’, the Universal Magazine’s correspondent from my opening paragraph, demonstrates. After complaining about the ‘quantities’ of ‘fresh novels’, he goes on:

To produce such a number as the press every winter teems with, the principles of mechanics seem to have been resorted to, and a certain quantity of paper is filled up with as much ease, as a labourer will plough a certain number of acres, or a painter cover a certain number of square feet; with this difference, indeed, that the ground must be well opened, and the paint substantially laid on; considerations which never enter into the heads of our manufacturers of novels, to whom quantity and expedition are the only objects.73

Lucius’s description of the press as ‘teem[ing]’, and his emphasis on ‘quantity and expedition’ over quality, are representative of the contemporary obsession with overproduction of novels, as we have seen. His criticism, however, also turns the reader’s focus away from novels as vehicles of ideas or emotions and towards the novel as a physical object, produced by labour to take up space in the world. While in the first example the physical presence of novels (‘learned lumber’) was evoked in terms of fuel for a deadly fire, here attention to the novel’s materiality (‘a certain quantity of paper’) embeds it in a larger system of labour and commerce. Whereas Columella’s novels become a firetrap, Lucius uses attention to the press, the paper, and the process of manufacture to recast the novel as a product. Both transformations, importantly, move authorial agency and artistic accomplishment out of the frame, a point that Lucius makes quite explicit in his next reflection:

From the workman-like facility, with which modern novels are composed, and from their increasing number, it is not, perhaps, too ridiculous to suppose that … the operation might be performed by a machine. In our days, labour has been wonderfully abridged by the invention of an Arkwright; and … it is not unreasonable to foresee the time when some ingenious gentleman will apply for a patent, … [for] ‘a Machine for making Novels, which will save the future labours of industry, and furnish the public with an article equally good, and executed in a tenth part of the time’.74

This argument is very much a continuation of the critical habit of characterizing popular novels as ‘manufactured’ or ‘commodities’, albeit rather more literal than most. I quote it here not simply to showcase an extreme example of this line of thinking but to call attention to Lucius’s dramatic reimagining of the novel’s conditions of production. As I suggest throughout this book, one perhaps unexpected outcome of the insistence that novels may be superfluous or oversupplied is the possibility such claims offer for transformation, thinking about new possibilities for understanding the novel’s capacities, whether in terms of physical pages or means of sale. The assertion that novels are ubiquitous, in other words, not only continually reminds readers of how and why this seeming ubiquity occurred – presses, advertising, reviews, fashions – but easily slides into reflection on how the novel, already having saturated the market, moves forward.

While authors and reviewers often treat the qualities of literary works as self-evident – a novel is a novel and is evaluated as such – the novel in a state of over-abundance is always at risk of becoming something else: kindling or toilet paper, speaking pejoratively; a museum exhibit or treasured artifact, more optimistically. The more abstract transfigurations of the novel are even more dramatic: in these accounts, it becomes an irresistible food, an addictive drug, a fashion, a flood. A novel sold over the counter might be rhetorically indistinguishable from a bar of soap; a novel produced by a ‘Spinning Jenny of Sentiment’, as Lucius calls his novel-writing machine, is a workaday textile.75 Lucius is clearly interested in transforming the novel into a machine-made product in order to denigrate it and devalue the work of authors. But many authors, as I hope my list of transformations above will suggest, see a different value in these metamorphoses. With numbers comes power, these authors argue; with efficient mass-production comes timeliness and desirability; with wide reproduction comes increased chance of survival. Columella’s author frames fiction’s collective energies as potentially destructive, but epically massive in scope; other authors assert the novel’s force in more modest ways, through claims about the breadth of their audience or the fashionable demand for their work. A novel cannot come into the world without the labour of numerous people, from author to typesetter to reader, and the metaphors of production and reproduction many authors embrace reinscribe this work, resisting and overturning the narratives of authorless books and ravenous readers levied by critics like Lucius.

***

This book traces the interlocking relationship between materiality, temporality, and style in the Romantic novel along a roughly chronological arc. Chapter 1, ‘Minerva’s Writers and Reviewers’, lays the groundwork for the rest of the argument, tracking descriptions of and responses to literary overproduction through the two groups of people most implicated in the Romantic period’s perceptions of it: reviewers and novelists themselves. Starting with the bibliographical commonplace that the end of the eighteenth century was the moment at which the number of novels published first began to exceed the annual reviewing capability of eighteenth-century reviewers, I follow the fate of the Minerva Press’s novels in the pages of major and minor reviews, demonstrating how the rhetoric of excess employed by professional reviewers not only established popular beliefs about which novels were worthwhile, but actively marginalized (or identified as superfluous or dangerous) certain categories of fiction.

Authors, naturally, responded to these attacks, and I examine a range of characteristic approaches from authors in the 1780s and 1790s. In particular, Chapter 1 shows how, through paratextual materials and narrative interpolations, Minerva authors explicitly present each novel as an entrant in a crowded market, potentially overwhelmed by the competition and inevitably compared to the other works with which it appears. Some authors pre-emptively defend their works against competitors or hostile reviewers, but many humorously embrace their relative anonymity, potential unpopularity, or ephemeral success, transforming these seemingly negative attributes into selling points. Authors frequently imagine their future readers in these passages, attempting to define their audience within their fiction even as they were less and less able to control the audiences of their fiction. Through these analyses, I trace the development of several distinctive ideas about scarcity and abundance that run through the rest of the book: debates about responsibility for the age’s glut of fiction; theories about the specific ties between the current crowded market and the novel form; and, finally, the relationship between excess, in its varied meanings, and literary taste.

Beginning with the Minerva novels on which so much of this discourse focused allows the subsequent chapters to expand to consider how these ideas applied to Romantic fiction more broadly. Chapter 2, ‘Godwin, Bage, Parsons, and Novels as They Are’, shows how the new demands of the marketplace shaped the development of 1790s political fiction. In the wake of the French revolution, the proliferation of English fiction began to strike more observers as particularly dangerous – critics feared that novels might be the vehicle of threateningly radical and immoral ideas, while many authors expressed anxieties about where and by whom their works would be read. Examining novels by writers including Eliza Parsons, William Godwin, and Robert Bage, this chapter begins to break down the divide between Minerva and non-Minerva authors, arguing that political ideas across the spectrum were often conceived and expressed as functions of multiplicity: How many readers, how many epistolary voices, how many viewpoints, how many ideological challenges could one novel handle? Focusing first on the proliferation of voices that a long novel allows, and then on concerns about the alarmingly wide and indiscriminate spread of fiction to its readers, I consider how these two ways of thinking about fiction’s function tie narrative style to the decade’s radical political debates. Reading across an entwined group of novels that purport to describe ‘things as they are’ (Godwin’s Caleb Williams, while the most famous of the group, postdates some others by several years), I show how authors directly tie their political arguments to marketplace realities and generic constraints.

Chapter 3, ‘Imitating Ann Radcliffe’, maintains the focus on literary style, through a discussion of the genre most often associated with the Minerva Press: the gothic. Indeed, if the Minerva Press is the publisher most strongly associated with fictional excess, then the gothic, as so many of the scholars I have quoted above suggest, is surely excess’s most representative genre. Readers decried the great length of these novels, their numerousness, their unoriginality, and the over-the-top emotions they depicted (and, it was feared, inspired in weak-minded readers). This chapter tracks the phenomenon of ‘imitation’ in the late eighteenth-century heyday of the gothic, first in its role as a convenient denunciation hurled at new gothic novels, and then as a broad and flexible authorial practice that, I suggest, allowed gothic novelists to capitalize on their strength in numbers and their dedicated readerships. It traces how successful Minerva Gothic novelists like Regina Maria Roche and Eliza Parsons (both of whose works famously feature in Northanger Abbey’s list of ‘horrid novels’), as well as many others, used imitation to define and expand the norms of their genre, particularly in relation to Radcliffe, often cast as the originary gothic genius. Ultimately, I suggest, imitation allows authors to resist unsympathetic critiques by harnessing the mass energies of a newly industrial book culture.

Moving towards 1810, I trace the novel’s increasing self-conceptualization as ephemeral, as fashionable, and as commercial, showing how these metaphors aligned fiction-writing with industrial production. While the physical qualities (size, appearance, accompanying ads) of novels are important to the works discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, in the second half of the book I focus in even more detail on the increasingly material characterizations of popular fiction, and particularly on the intersection of materiality and temporality. In Chapter 4, ‘Hannah More’s Cœlebs and the Novel of the Moment’, I take the 1808 publication of More’s unlikely best-seller, the evangelical, didactic novel Cœlebs in Search of a Wife, as a case study to explore the ways that authors responded to new market conditions by writing deliberately ephemeral novels – works intended not for posterity but to be read and relevant only in their contemporary moment. Within two years of Cœlebs’ publication, other authors had produced at least six full-length response novels, which imitated, continued, parodied, or mocked the original work. For these Romantic authors, the (very) short term was far more important than any imagined future. Indeed, the potentially fleeting nature of literary relevance and success is framed, in this context, as a positive attribute, rather than an evil to be avoided: it transforms overproduction into increased opportunity. The authors of these works, I argue, embrace the idea of literary production as time-sensitive and transient: rather than fearing or fighting the phenomenon, they capitalize on the fast-paced literary culture of the time to emphasize their own works’ timeliness and contemporary relevance. If there are too many books, one must read and write faster; by the same token, however, the less time on the public stage each individual book demands, the more the field is opened for even greater numbers of novels.

While Chapter 4 considers how Romantic novelists embraced speed and ephemerality as a defence against a crowded marketplace, Chapter 5, ‘Fiction as Fashion from Belinda to Miss Byron’, examines a different way that novels were envisioned as in – or out of – fashion. As industrial production ramped up in the early nineteenth century, supplying consumers with mass-produced products from Wedgewood china to pocket-watches, so too, this chapter argues, was the popular novel conceptualized as a consumer good, as an object to buy and display as much as a text to read. I begin with Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801) to explore how this work takes fashion as a topic within the novel as well as, potentially, a way to measure the novel itself. The chapter then moves forward to the 1810s, examining several novels by Minerva author ‘Miss Byron’, among others, to demonstrate how this discussion of novel-as-luxury could at once be used as a way to valorize the novel and to make visible the often-ignored labour of its authors. The moral and material excesses of overspending consumers become a metaphor for the glut of the literary market, while the notion of luxury as always created by someone’s work – but also as essentially commodified and interchangeable – implicates the novel in a commercial system that challenges the hierarchies of strictly literary valuations.

In Chapter 6, ‘Walter Scott’s Industrial Antiques’, I show how these increasingly material ways of valuing the novel were mobilized in the decade after 1814, as the popular novel’s very ubiquity began to be portrayed as a potential justification for future literary worth. The luxuries of Chapter 5 are luxurious precisely because they are both rare (few can afford them) and numerous (in the nineteenth century’s new commodity culture, there are enough quizzing-glasses and gold pocket-watches for all who can buy them). Chapter 6 shows how Walter Scott, ultimately the age’s most prolific and best-selling novelist, successfully turned the era’s rhetorical attacks on fiction to his own commercial ends, though not without considerable risk to his literary reputation. I begin by showing how directly and frequently Scott’s novels were compared with those published by the Minerva Press in the previous two decades: Scott’s defenders marked the 1814 publication of Waverley as the death knell of Minerva, while his detractors habitually remarked upon the parallels between his numerous, voluminous novels and those produced in equally large quantities by the Press. In readings of Scott’s early novels and his self-conscious paratexts, I show how he ties the seeming historical veracity of his fiction to its market value. Scott’s novels explore an antiquarian system of valuation in which even the most uninteresting document becomes valuable to posterity as soon as it is rare. In so doing, they offer a unique defence of those ‘innumerable’ popular novels that, as his narrators point out, churn from ‘The Author of Waverley’s’ pen just as quickly as they had been rolling from the Minerva’s in-house printing presses. The more works one produces, Scott hints, the more likely it is that least a few of them will survive to be the treasures of another age. Scott and many of the other popular novelists who wrote alongside him suggest that being truly prolific may ultimately lead to literary prestige rather than undermine it.

***

From the lofty perch of 1820, a literary commentator in The Port-Folio looked back on the literary developments of the previous decades, noting the novel’s ubiquity, but also invoking the materiality of the circulating library and the supposed class affiliations of its patrons and contributors. The ‘deluge’ of novels described here is voluminous, promiscuously circulated, and produced by scorned scribblers:

The path of novel-writing once laid open was imagined easy by all, and for about forty years the press was deluged with works to which we believe the literary history of no other country could produce a parallel. The milliner’s prentices who had expended their furtive hours, and drenched their maudlin fancies with tales of kneeling lords and ranting baronets at the feet of fair seamstresses … soon found it easy to stain the well-thumbed pages of a circulating library book with flimsy sentiments, and loose descriptions of their own.76

The portrait painted by this passage highlights problems of several different kinds, with its evocation of stereotypical plots, emotional authors, and library shelves groaning with grubby volumes. Also apparent is an obvious attempt to relegate these unpleasantries to the past, suggesting that both literature and the reading public have advanced and improved. Literary history itself is portrayed in this quotation as a kind of superfluity, consigned wholesale to a best-forgotten closed chapter. But for all this critic’s efforts, it is plain that England’s age of fictional excess did not end with the fall of the Minerva Press. Burlesquing Lord Byron’s burlesque Don Juan in 1830, a writer in Fraser’s Magazine was still denouncing novelists as much for their sheer numerousness as for their lack of literary talent: ‘But of all the classes of mediocre writers, the class of novelists beats the others hollow. They actually swarm in this department – they are like heroes, – “Every year and month sends forth a new one.”’77

If many onlookers earlier in the eighteenth century had identified new growth across all of print culture, after the Minerva Press Era, as this satirical jab suggests, the novel retained a distinctive place as a site of specific anxieties about literary development. It is no accident that when the Victorian novelist George Eliot imagined herself as an eighteenth-century reader predicting the future of this new literary genre, it was the Minerva she saw – as she wrote in the Westminster Magazine in 1853, ‘the Minerva press looms heavily in the distance’. The formulation is striking for the vast scale and physical size the metaphor implies, but also for the remarkable fact that Eliot viewed a single publishing house, one that had been defunct for more than thirty years at the time she wrote, as centrally significant to the novel’s past and future. Amid the ‘loose and baggy monsters’ and ever-expanding serials of the Victorian period, the Minerva Press remained a symbol of its age, the simplest way to evoke the literary excesses of the past. To describe the Romantic period as the Minerva Press Era is a deliberately provocative re-visioning of this literary moment, a re-orientation that directs our attention to the collective rather than the singular.