I EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION AND JAPAN’S COMPANIES ACT: A RELATIONSHIP WORTH EXPLORING?

Executive compensation in corporate law is often defined as an agency problem between shareholders and executives.Footnote 1 Without adequate monitoring mechanisms, executives may either pay themselves too much or structure their pay in a way that is not adequately tied to their performance. In either situation the interests of the corporation and its shareholders may be adversely affected, creating a problem that corporate law and governance practice must deal with. In this respect, executive compensation in Japanese corporations has been described as a comparative puzzle.Footnote 2 Most of the corporate governance mechanisms meant to address these risks in the United States (US) – such as the use of compensation committees and independent directors – are not commonly found in Japanese corporations. At the same time, the compensation received by Japanese executives has until recently neither been strongly tied to performance nor particularly high.Footnote 3 This divergence has sparked interest in the determinants of how, and how much, executives in Japan are paid.

Recent studies suggest that social norms against greedFootnote 4 and corporate governance mechanisms specific to JapanFootnote 5 play important roles in the pay setting process and may help to explain the setting of executive compensation in Japan. One factor yet to be explored, however, is the role played by Japan’s Companies Act Footnote 6 provision governing director pay. Article 361 of the Act creates what, at risk of oversimplification,Footnote 7 can be described as a Japanese version of ‘say on pay’ (J-SOP) system of approving pay for corporate directors at most Japanese corporations. The rule (hereinafter the ‘J-SOP rule’), which has existed since the promulgation of the Commercial Code in 1898, requires that all compensation paid to directors must be approved either in the articles of incorporation or by a resolution of the shareholders meeting. Since the articles of incorporation must themselves be approved by the shareholders, the effect of this rule is to subject all changes in aggregateFootnote 8 director compensation to shareholder approval. While it only applies to directors and not to other executives,Footnote 9 in practice most senior executives serve as directors. The position of director is typically the highest on the internal promotion ladder for employees, and the president of a company normally holds the position of representative director.Footnote 10 While recent reforms since 2002 have sought to more clearly delineate the roles of directors and officers through the creation of executive officers who do not sit on the board, the vast majority of companies maintain the conventional system,Footnote 11 and thus the compensation of all but a small number of executives at Japanese companies is subject to the J-SOP rule.

The existence of this rule suggests an obvious explanation for the differing compensation Japanese executives receive compared to their American counterparts, whose pay is not subject to an equivalent rule.Footnote 12 If shareholders feel directors are asking for pay that does not reflect their preferences, be it because it is too high or not adequately tied to performance or for other reasons, they can simply vote it down, which has the effect of denying the directors any legal claim to that pay. In order to avoid this outcome, directors may keep their pay requests modest. This explanation would in fact be consistent with the view that Japanese courts have taken on the J-SOP rule’s purpose throughout the post-war period, which is to discourage directors from abusing their position to pay themselves excessively to the detriment of the company.Footnote 13

This simple hypothesis has likely gone unexamined thus farFootnote 14 for three reasons. The first is that, as shall be discussed further below, judicial decisions have placed limitations on the J-SOP rule which limit its effectiveness as a means for shareholders to police pay. The second is that the literature has viewed decisions on executive pay in Japan as the result of a process in which shareholders have played little role. The focus instead has been on the informal monitoring role played by other stakeholders, notably main banksFootnote 15 and company employees,Footnote 16 in checking pay levels. Systems of cross shareholdings among companies which developed in the 1950s as a way of preventing changes in corporate controlFootnote 17 may also have contributed to this by blunting the relevance of shareholder voting since a majority of the voting rights were kept in management-friendly hands. A third is that, as this study finds, shareholder voting is overwhelmingly positive, with shareholders routinely approving pay requests.

While the J-SOP rule has its limitations, however, its relevance cannot be discounted. The rule does require the board to commit itself to an absolute ceiling on its compensation and subject itself to scrutiny by the shareholders for any changes thereto. Moreover, rejection of a pay proposal is binding on the board, unlike recently introduced ‘say on pay’ provisions in some jurisdictions that merely require advisory votes. Despite the generally positive votes that proposals receive, the process of voting itself exposes pay to scrutiny it otherwise would not receive. Directors are exposed to potentially awkward questions at the shareholders meetings on pay proposals that they are legally required to address, and when significant blocks of shareholders dissent (as this study finds sometimes happens), this may act as a signal to the market. Moreover, changes to corporate governance in Japan since the 1990s raise the possibility that the simple hypothesis is worth investigating. One reason for this is the declining significance of the institutions that earlier literature identified as playing key roles in monitoring compensation – the main bank, lifetime employment and cross shareholding systems.Footnote 18 A second reason is that while the proportion of shares held in domestic cross shareholding relationships has decreased, the proportion owned by foreigners has increased.Footnote 19 Since foreign shareholders may hold different views on compensation from their domestic counterparts, they may also be more inclined to use their voting rights to challenge compensation related resolutions. Finally we have the fact that traditional Japanese norms on pay – often expressed as the idea that greed is badFootnote 20 – have become contested in some companies. Jackson and Milhaupt’s workFootnote 21 shows that a bifurcation of executive compensation levels and structure at different types of companies exists, which suggests that differing norms on what constitutes acceptable pay prevail at different companies. This is also evidenced in interviews with Japanese CEOs conducted by Olcott and Dore,Footnote 22 which indicate some feel pinched between competing views of employees and investors as to what constitutes an acceptable level of executive pay.

In order to determine the relevance of the J-SOP rule based on these observations this article examines the behavior of the two key players in the J-SOP voting process: directors and shareholders. Since 2010 publicly traded companies have been required to disclose the results of shareholder voting, including on J-SOP resolutions, which provides us with data not only on the content of resolutions but also on how shareholders voted on them. This article looks at the reported results of shareholder votes on J-SOP proposals relating to director pay at companies listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2014 to see what directors asked shareholders to approve and how shareholders reacted.

With respect to directors, since the rule only requires shareholder approval when changes to existing pay arrangements are sought they have a great deal of discretion in deciding not only what to ask for, but also when to ask for it. If the J-SOP rules act as an enforcement mechanism we would expect directors to tailor their requests accordingly based on the characteristics of the company and the preferences of their shareholders. Questions related to this include: do directors at companies which are performing well ask for raises? Does company size affect what directors ask for? Do directors at companies with a high proportion of foreign shareholders, who are less likely to ascribe to Japanese social norms on pay, ask for different pay from those with mainly domestic shareholders? On the shareholder side, we can look at how various factors, both exogenous and endogenous to them, affect their voting. Are they more likely to support certain types or amounts of pay over others? Does recent corporate performance influence their voting? Do foreign shareholders vote in different ways than domestic shareholders?

Our study finds that significant variation in both what directors ask for and how shareholders vote exists across companies and points to a divergence in the role that the J-SOP rule plays in compensation related decisions. We find that directors of larger companies with higher levels of foreign shareholdings ask their shareholders to approve generally higher levels of compensation with a greater component of incentive pay. Directors at smaller companies with less foreign shareholdings on the other hand are more likely to ask for lower levels of compensation with a larger component of stable base pay and a deferred component in the form of a retirement bonus. These generally reflect two different views on the function of director pay – the former seeking to tie it more closely to performance and the interests of shareholders, while the latter is less focused on immediate performance and more on ensuring long-term loyalty and stability, consistent with norms associated with more traditional institutions of Japanese corporate governance such as the lifetime employment system. While all of the J-SOP proposals examined in the study were approved, there was significant variation in levels of support associated with factors such as the type of compensation request being voted on, the size of the company and the proportion of foreign shareholders, who in general were much more likely than their domestic counterparts to vote against director pay requests.

This leads us to the conclusion that the simple explanation – that shareholder use of the J-SOP rule controls director compensation in Japan – remains too simple since the context in which it is used varies widely across companies. We do, however, argue that the changing corporate governance landscape in Japan has created a space for the J-SOP rule to have relevance, particularly in companies where owing to these changes the norms governing pay decisions are contested and the traditional informal mechanisms for dealing with them are inadequate. Any model for explaining executive compensation in Japan is thus incomplete without an understanding of the role played by the J-SOP rule.

This article proceeds as follows. In Part II, we review the previous literature on executive compensation in Japan. Part III provides an overview of the regulation of executive compensation under the Companies Act, its J-SOP provisions and the types of resolutions that these provisions require in practice. Part IV then presents the quantitative data gathered in this study. Part V discusses the results of the analysis and what it suggests about the role of the J-SOP rule. Conclusions follow.

II DETERMINANTS OF EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION IN JAPAN

The question of how executive pay is set in Japan has been examined by a number of studies that link it to broader questions of who monitors decision making by executives. This literature can generally be divided into two categories. The first consists of studies focusing on compensation in the 1990s when the ‘traditional’ institutions of Japanese corporate governance – lifetime employment, the main bank system and cross shareholdings – were dominant.Footnote 23 The second have looked at compensation in a corporate governance environment in which these traditional institutions have been weakened in the aftermath of Japan’s lost decade and reforms that have at times explicitly sought to move away from them.Footnote 24 All of these studies, as with this one, have been constrained by the limited disclosure requirements placed on companies with respect to individual compensation of executives. Thus, these studies relied on income tax dataFootnote 25 or aggregate data on overall board compensation.Footnote 26 The more recent studies conducted since 2010Footnote 27 have been able to make use of an additional data source provided by the requirement for companies to disclose individual compensation paid to executives earning in excess of 100 million yen per year, though few earn more than this,Footnote 28 and our knowledge of the amount actually paid to most directors remains limited.

Theories about which factors determine executive compensation at Japanese companies have generally evolved in tandem with changes in monitoring structures in corporate governance. In the 1990s, two related theories were put forward. The first posited that director compensation levels were closely linked with those of regular employees. Using aggregate director compensation data from 1995 and 1996, KuboFootnote 29 found a significant correlation between director and employee wages in large Japanese companies and concluded ‘…directors and employees have (the) same incentive structure, ie many directors consider themselves as a ‘promoted’ employee rather than as agents of the shareholders.’Footnote 30 This correlation fit well with the idea that employees formed the primary control group within Japanese corporate governance and the lifetime employment system that reinforced this by closely tying the interests of employees with the company.Footnote 31

A second, though not necessarily conflicting, view was that corporate group (keiretsu) affiliation and main bank monitoring played a key role in determining executive compensation.Footnote 32 Under the main bank system,Footnote 33 companies made heavy reliance on bank financing. Through lending relationships, cross-shareholdings and the provision of other services to client firms, main banks had access to information on company performance and an incentive to monitor management, including on compensation related matters. Cross shareholdings among companies within the same keiretsu groups of companies shielded management from the threat of an external market for corporate control, thus making the main bank the primary mechanism through which management was monitored. KatoFootnote 34 found that executive compensation was significantly less at keiretsu affiliated companies than at independent companies, suggesting that main banks played a role in controlling executive compensation at client firms. Kato further found that compensation at firms with main bank relationships was structured to reward capital investment and company growth, something which risk-averse banks favour more than shareholders. These characteristics also benefit employees since growth of the company better secures their jobs, thus the employee and main bank views on the determinants of executive compensation can be seen as complimentary rather than conflicting.

Two points should be stressed about these views. The first is that they provide explanations for the comparative puzzle regarding the lower levels of compensation in Japan despite the lack of US-style mechanisms for controlling such. The American model generally treats compensation as an agency issue between shareholders and managers and addresses it through mechanisms that give the former some ability to monitor the latter. In the Japanese system described above, however, compensation is treated as an issue between employees and banks on the one hand and directors on the other. Since these stakeholders had other monitoring mechanisms available, it is unsurprising that the use of US-style measures did not become commonplace.

The second point is that these studies are based on a model of corporate governance that has undergone significant changes since they were carried out, which brings us to the second more recent set of studies. In the intervening years, there has been a general decline in the role of these stakeholders (employees and main banks) in Japanese corporate governance, while the role of shareholders has come to greater prominence.Footnote 35 The system of lifetime employment has been weakened by increased reliance on temporary workers,Footnote 36 and there has been a growing trend towards the appointment of outside directors to the boards of large companies whose primary loyalty would not be to the employees.Footnote 37 The main bank system has likewise been reduced in significance, a process begun with changes to the financial system in the late 1990s with the express purpose of encouraging greater reliance on equity rather than bank finance.Footnote 38

The declining influence of these stakeholders has coincided with reforms specifically intended to foster greater reliance on capital markets.Footnote 39 These have generally focused on enhancing shareholder rights and introducing familiar mechanisms from American corporate law – notably through the introduction of the American style companies with committees system in 2002.Footnote 40 Among other changes, there has been a rapid rise in the use of shareholder litigation against directors, an increase in the appointment of outside directors, greater M&A activity, and a greater sensitivity to shareholder relations by Japanese executives in terms of share price and dividends.Footnote 41 While most of these changes do not directly relate to compensation, the point to be made is that the decline of traditional monitoring mechanisms has coincided with a greater focus on the agency relationship between shareholders and managers.

Reflecting these changes, more recent scholarship has produced new theories on what affects executive pay at Japanese companies. One view, which addresses not only the question of what affects executive compensation but also the question of why it is much lower in Japan than in the US, is that the traditional institutions of corporate governance produced strong norms against greed among managers that have survived their decline.Footnote 42 In this view, regardless of the rules applied and the actors tasked with oversight – be they shareholders or main banks – the internalized norms held by directors themselves may cause them to avoid acting opportunistically with respect to their own compensation.

Another view is that changes in corporate governance have mattered for executive pay. Using data obtained from disclosures of executives earning over 100 million yen, Jackson and MilhauptFootnote 43 examined how differences in corporate governance mechanisms at differing firms affect compensation. Their research revealed a number of distinctions in individual executive compensation – such as the fact that foreign executives drawn from the international market earned significantly more than Japanese ones – but more relevantly also between companies with differing corporate governance structures. Specifically, they found that bonuses and stock options constituted a larger portion of the pay packages at companies that had adopted the newer US-style companies with committees system than those which maintained the traditional companies with auditors system. This suggests a divergence in pay practices, with some companies following a more shareholder-centric approach based on the American model while others (in the majority) maintain elements of the traditional Japanese model.

The two sets of studies – the first based on the traditional institutions of corporate governance and the second based on a system in transition away from the same – provide us with models for understanding director compensation in Japan but lack a consideration of what role the J-SOP rule plays within them. Under the former this may have made sense given the marginalized role of shareholders and the alternative mechanisms used to control compensation. The more recent literature however suggests possible avenues by which the J-SOP rules may be gaining relevance. Shareholders may be making greater use of the rights granted to them by the J-SOP rule to police director pay requests. The decline of cross shareholdings that protected directors from adverse votes has to a certain extent removed an important obstacle to giving that right some meaning. In terms of norms, the increase in foreign shareholders and exposure by a limited number of companies to the international market for executive talent suggest that traditional views on pay may be increasingly coming into conflict with the (quite different) views that exist overseas. Voting is an obvious place where such disputes may play out, as the law gives shareholders a weapon to object to pay that can be quite powerful if they use it. We explore the extent to which this is actually happening in our review of the data in Part IV, but first it is necessary to lay out how Article 361 regulates shareholder voting and defines the rights of directors to their pay, which we turn to in Part III.

III THE REGULATION OF COMPENSATION UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT

The Companies Act provides a choice between three different governance structures which it is necessary to briefly review since different rules on director compensation apply to each. Prior to 2002, all joint stock companies (kabushiki kaisha) used more or less the same form currently known as the ‘Companies with auditors’ system. Reforms in 2002 and 2015 have added to this the ‘Companies with committees’ and ‘Companies with Audit and Supervisory Committee’ systems, which are alternative forms companies may adopt.Footnote 44 Companies with auditors trace their roots to the original Commercial Code.Footnote 45 Companies using this structure generally followed (and to varying degrees continue to follow) a managerial board model in which the board takes an active part in managing the company rather than simply overseeing its function.Footnote 46 They consist of a board of directors who (in theory at least) are monitored by a board of auditors tasked with ensuring the directors comply with their legal duties. For large companies, a separate position of accounting auditor must also be fulfilled. Such companies are not required by the Companies Act to appoint any outside directors.Footnote 47

Companies with committees on the other hand were introduced following reforms at Sony which attempted to more clearly delineate the function of the board as an oversight body.Footnote 48 Such companies do away with the board of auditors and instead require the formation of audit, nomination and compensation committees within the board of directors. The majority of each of these committees must be comprised of outside directors, whose numbers are on average much higher in companies with committees than at companies with auditors. The Act creates the position of executive officers to carry out the day to day management of the company under the board’s oversight. The third form, companies with audit and supervisory committees, was introduced with the most recent reform to the Companies Act which came into effect in 2015. It also does away with the board of auditors but only requires a single audit and supervisory committee to be formed within the board of directors. This represents a sort of mid-way compromise between the two other systems.Footnote 49

In terms of compensation the most important distinction between these three types is that under the company with committees system, decisions on the remuneration of directors and executive officers are made by the compensation committee and the J-SOP rule does not apply. For companies with boards of auditors and companies with supervisory and audit committees the J-SOP rule does apply. Since the companies with supervisory and audit committee system came into effect after our data was collected, and since companies with committees are not subject to the J-SOP rule, this study focuses exclusively on companies with auditors. The significance of this exclusion is minimized by the fact that the vast majority of companies, approximately 98.3 per cent of those listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, were organized as companies with auditors at the time our data was collected.Footnote 50 It is important to mention, however, that Jackson and Milhaupt’s recent studyFootnote 51 has found different pay practices at companies with committees, which generally pay their executives more and rely more on incentive based compensation. In terms of pay, in other words, companies which have adopted that system (and in so doing opted out of the J-SOP rule) are something of an outlier from the dominant trends found at the much more numerous companies using the traditional structure.

Having noted this distinction, we now turn to the substance of the J-SOP rule. The rule, which was enshrined in Article 269 of the Commercial Code until 2005, originally consisted of just one line: ‘[i]f the amount of remuneration to be received by the directors has not been fixed by the Articles of Incorporation, it shall be fixed by the resolution of a general meeting of shareholders.’Footnote 52

Article 280 applied the same provision to auditors. These provisions survived the post-war amendments to the Commercial Code and were further revised in 2002, when a number of sub-clauses were added to clarify that the rule applied to both fixed and non-fixed remuneration, as well as non-monetary compensation. In 2005, the Commercial Code provisions on corporate law matters were repealed and replaced with the Companies Act;Footnote 53 these rules were thus carried over into Articles 361 (for directors) and 387 (for auditors), which constitute the currently applicable rules.Footnote 54

The J-SOP rule requires that any ‘financial benefits’ which directors receive as consideration for the execution of their duties must be fixed either by a resolution of the shareholders meeting or by the articles of incorporation. Since any changes to the articles of incorporation must themselves be approved by the shareholders, this means that all changes in the compensation of directors must be approved by the shareholders meeting.

In comparison with ‘say on pay’ provisions elsewhere,Footnote 55 the Japanese version has its strengths and weaknesses. Foremost among the former is that the votes are binding, giving shareholders the power to deny a proposed change rather than merely expressing their disapproval of it. Moreover it covers all forms of remuneration a director can receive – including salary, bonuses, stock options, retirement benefits and other forms. A major weakness, however, is that the provisions have been held to require shareholder approval of the overall compensation limit for the board as a whole rather than for individual directors.Footnote 56 After approving a global amount the board then apportions it amongst individual directors without further shareholder approval. Yet another flaw is that courts have interpreted the provision as applying exclusively to compensation related to their duties as a director.Footnote 57 For directors holding other positions within the company, the portion of their salary related to that position is not subject to shareholder approval.

A third problem with Japan’s J-SOP rule is that unlike jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, where shareholders are asked to regularly approve a report on director remuneration which follows a set format, the Japanese version lends itself to irregular votes on isolated elements of director pay. Article 361 does not require annual shareholder approval, rather it simply requires that compensation paid be within limits that have been approved by the shareholders meeting. Provided that a company does not wish to change previously approved compensation limits in a given year, it is not required to put any such proposals to the shareholders meeting. Even if a company reduces its number of directors (thus increasing the amount of compensation potentially available per director under a previously established limit) it is not required to hold another vote on compensation. Approximately 70 per cent of the 1,834 companies examined in this study did not vote on compensation proposals in 2014. Practice varies significantly across companies, with some updating their compensation plans regularly while others go decades without doing so.Footnote 58 Additionally, when the board wishes to update part of its compensation package, it is only required to gain shareholder approval for that specific part and not for the package as a whole. So if it wishes to give a one-off performance bonus, it only has to put that change before the shareholders meeting while other elements of compensation (such as base salary) are left out.

The legal effects of a resolution passed pursuant to Article 361 and what rights or obligations it creates is not stated in the provision, but these can be inferred from other articles in the Act and from judicial decisions. The default position for directors is that they are not to receive any compensation since their contracts are subject to the Civil Code rules on mandates; Article 648(1) of the Civil Code states that absent special agreement to the contrary, a mandataryFootnote 59 may not claim remuneration. Courts have interpreted the contract between directors and the corporation as containing either an express or implied provision stating it was to be paid, but that approval of remuneration by the shareholders pursuant to the J-SOP rules was a precondition for any contractual claim to materialize.Footnote 60 The courts have only carved out one narrow exception to this which applies to closely held corporations where it can be shown that the shareholders, despite not adhering to the formalities required by the J-SOP rules, nonetheless unanimously consented to the compensation in question.Footnote 61

Of importance is the fact that this applies even where a director has been promised by the representative director of the company, who has the power to legally bind it to a contract, that certain compensation will be paid. Such promises only become enforceable once they have been approved by the shareholders. Thus if the board of directors fails (perhaps deliberately) to put a resolution to the shareholders approving compensation based on such promises the director has no claim against the corporation. This situation sometimes plays out in the context of a director who is forced to retire after an internal power struggle and the new directors do not ask the shareholders to approve his/her retirement benefits.Footnote 62

Once a resolution is approved by the shareholders, it becomes a part of the contract between the director and the corporation. Since many such resolutions, as shall be outlined below, delegate decisions on the details of distributing the approved pay to the board of directors, once such a resolution has passed the board is under a positive duty to implement it within a reasonable time.Footnote 63 This is generally most relevant with respect to retirement benefits approved for former directors, since resolutions approving such payments generally identify the retiring director and, no longer being a director, they are free to sue in the event that they are not paid. While most other resolutions do not name specific directors and thus do not create a right to a specific amount of pay, one way in which such resolutions nonetheless define the terms of the contract is that it protects individual directors from unilateral cuts to their pay by the board. Courts have held that where a director’s base pay has been set within a compensation limit defined by a previous J-SOP resolution, the board of directors cannot ask the shareholders to subsequently approve a lower limit in order to force the director to take a pay cut since this would violate the contractual rights of that director, which came into being when the first resolution was approved and implemented by the board.Footnote 64 In other words, such resolutions not only bind the directors, but also the corporation to the contractual terms they define. Conversely, when a director has already received compensation which was not approved by a J-SOP resolution, they may be subject to claims of unjust enrichment under Article 703 of the Civil Code.Footnote 65 In addition to directors who receive such payments, those directors which approved them may also be liable for having breached their duty of care.

While the provisions themselves are silent as to the format and content of resolutions, similarly phrased precedents are widely used based on criteria defined in Article 82 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Companies Act.Footnote 66 Since these vary significantly in content, and also because these form the basis of our empirical study, it is useful to set out a taxonomy of the types of resolutions which the J-SOP rule necessitates. It is important to note that the format of J-SOP resolutions is not strictly limited to these types and that variations exist. What follows is a general guide to the most common resolutions based on those reviewed in this study.

A Base Pay Compensation Limits

Director base pay is approved in a resolution asking the shareholders to approve a global limit on annual compensation for all directors, while delegating the amount for each individual director, and the timing and method of such payment, to the discretion of the board. The amount paid to inside and outside directors must be disclosed separately. It is not necessary to approve limits to base pay annually, but only when a raise in the previous limit is sought. While the wording of such resolutions seem to give complete discretion to the board and obscure the amount actually paid, judicial decisions have imposed certain constraints on the board. Many larger companies have their own internal rules set by the board which provide a formula for calculating pay for individual directors. While courts have held that these internal rules do not themselves require shareholder approval,Footnote 67 they are accessible on request from shareholders under Article 433(1) of the Companies Act, though this right is restricted to those holding at least 3 per cent of shares.

Since a 1982 revision to the Commercial Code, directors have also been under a duty to explain matters before a shareholders meeting and judicial precedent has defined this as including a duty, when asked, to inform shareholders of the existence of any internal rules that will be used to divide the pay and either explain the content of them or indicate how they may access them.Footnote 68 If the company does not have internal rules, courts have interpreted the directors as being under an implied duty to set pay based on reasonable standards having regard for the purpose of the J-SOP rule.

B Bonuses

Since bonuses are a one-off payment which are not normally included in base pay, they must also be approved of if their payment would exceed existing compensation limits. Like base pay compensation limits, these resolutions usually set a fixed amount for the whole board, distinguishing only the amount to be paid to outsiders apart from insiders, with the details left at the discretion of the board. The limitations placed on that discretion with regard to base pay compensation limits also apply to bonuses.Footnote 69

C Retirement Bonuses

Retirement bonus resolutions are different in a number of respects from others. Since they are approved based on the retirement of a director, they are the only type of resolution where the recipient is named. At the same time, they are also the only resolution that generally does not cite a specific amount in yen. Rather, such resolutions usually state that in recognition of their long service with the company a retirement bonus will be paid, the amount, method of payment and timing to be at the discretion of the board. These resolutions limit such discretion by requiring the amount be within reasonable limits established by the standards of the corporation. This can be either a reference to the company’s internal rules for calculating retirement bonuses or, where such rules are not established, to past practice at the company with similarly situated directors. Payments to the estate of deceased directors as condolence money also follow this pattern.

D Retirement Bonus Cash Outs

Some companies have been eliminating retirement bonuses and in compensation are making lump sum payments to directors affected, usually in the amount they would have accrued at the date of the resolution under the system being eliminated.Footnote 70 These generally ask for the approval of a global amount to be distributed at the discretion of the board.

Such resolutions illustrate one way directors are structuring their pay so as to avoid subjecting it to shareholder voting.Footnote 71 Having part of their lifetime pay tied up in a single payment at the end of their career carries some risk. It exposes that payment not only to potential rejection by shareholders, but also to internal disputes since the board of directors itself must submit a proposal seeking approval of an individual retiring director’s bonus. If the retirement is forced upon the director owing to a scandal, the board may be disinclined to do so. Converting the retirement bonus into an immediate claim for payment at a time chosen by the board removes this risk.Footnote 72

E Stock Options

While most Japanese companies rely on base pay, bonuses and retirement benefits to compensate their directors, an increasing number are also relying on stock options and other forms of incentive pay. The Companies Act establishes certain default features of stock optionsFootnote 73 and requires that the company prescribe certain matters such as the number of shares and their features, whether or not consideration will be given for them and their date of allotment.Footnote 74 Depending on whether or not the company is considered a public company, shareholder resolutions approving the granting of stock options to directors under Article 361 may also be accompanied by resolutions required under Articles 238(2) and 239, which in effect state that the subscription requirements must be determined by the shareholders meeting but may be delegated to the board of directors. For public companies the board of directors is delegated by default.Footnote 75 In either case, the subscription requirements must comply with the provisions of Articles 236 and 238, and shareholders must be notified of these if their determination has been delegated to the board. Thus most of the important information regarding the details of the stock options are conveyed to shareholders through these mechanisms rather than through resolutions required by the J-SOP rule.

IV HYPOTHESIS AND DATA

A Overview and Hypothesis

Part III described how Article 361 structures the approval of compensation for directors by shareholders and the types of resolutions it requires. We now turn to the question of how the existence of this process affects compensation and its relationship with social norms and corporate governance mechanisms that previous literature has examined. In particular, we are interested in whether or not the rule is playing an increased role as an enforcement mechanism at companies where changes to norms and corporate governance suggest disagreement in normative views on pay. Scholarship in the 1990s attributed prominent roles to main bank monitoring and internalized norms which bound the interests of directors to those of employees in the compensation setting process, with each serving to keep pay levels relatively moderate.Footnote 76 In such a system, the actors monitoring pay would have used other means to police director pay.Footnote 77

The decline of the main bank and lifetime employment systems, combined with the increased role envisaged for shareholders in recent corporate governance reforms and significant changes in the makeup of shareholders themselves raise the question of whether the role of the J-SOP rule has changed. In companies where norms on pay are shared and the traditional mechanisms of corporate governance remain strong, the role of the J-SOP rule may remain minimal. But for companies where these changes have been most pronounced – where normative disagreements among stakeholders (specifically directors and shareholders) exist and informal governance mechanisms are inadequate to address them, the question is less clear cut. We might expect the J-SOP rule to become relevant in such situations in two ways: shareholders using their votes to express disagreement with director compensation requests, and directors responding ex ante to the threat of shareholder rejection by tailoring their requests to what they think shareholders will react positively to.

In order to explore these questions, we have put together a set of data on all companies listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2014 whose shareholder meetings were asked to vote on J-SOP resolutions in that year. Our aim is to broadly test for factors that may influence what compensation directors ask for on the one hand, and voting results on the other. By a pooling of shareholder meeting data, along with several other data sources, we are able to obtain a substantial level of information regarding J-SOP votes in a variety of companies, including actual voting behavior, type of compensation being considered, proportion of board seats held by insiders and outsiders, estimates of inside and outside director base pay levels, as well as demographic factors such as company size, return on assets (ROA), and level of foreign shareholding.

The data in our study was gathered from a number of sources. Results from the 2014 shareholder meetings on 1,834 companies listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange were obtained from their filing documents (Rinjihōkokusho) sourced from the Financial Services Agency’s EDINET website.Footnote 78 In addition to identifying the content of all proposals voted on at each company’s shareholders meeting, these also provided the vote in favour to the nearest 1/100th of a percentage. These were then examined individually to determine if the company had put a J-SOP based resolution to their shareholders meeting. This revealed that 514 companies had voted on 649 separate J-SOP resolutions, including votes on pay for both directors (547 distinct votes) and auditors (102 votes). Since the position of auditor is less important than that of director,Footnote 79 and since unlike directors they have no role in setting proposals related to their own pay, we focus exclusively on voting on director pay proposals. Additional governance, ownership and performance information on these companies was obtained from their Tokyo Stock Exchange Corporate Governance Reports, Worldscope Company Reports and their own shareholder prospectus.Footnote 80

To explain the relevance of each factor, we start with the hypothesis that companies of different sizes face different market conditions that influence accepted norms on compensation. Company size is relevant since logically larger companies can be expected to provide more compensation and also because size may be relevant to the market and normative forces the company is exposed to. A small company is generally less likely to operate in foreign markets where different norms prevail or to provide enough of an incentive for an activist hedge fund to invest time and resources in challenging existing pay arrangements that it views as sub-optimal.

In addition to size, differing levels of recent performance may also be influential. ROA may be relevant since logically directors at companies which are doing well may be more likely to ask for a raise and shareholders more likely to grant it. Since ROA for a single year is a relatively short term and imperfect measure of director performance it may also be an area for normative divergence. Shareholders (and directors) who place value on long term considerations may ignore it completely while those with a short term perspective may consider it relevant to questions of compensation.

We further hypothesize that the proportion of foreign shareholdings at a company are relevant since foreign shareholders would not necessarily share the normative views on compensation that prevail among domestic shareholders. There is some evidence for this in the behaviour of foreign activist hedge fund investors who have used their position as shareholders at Japanese companies to challenge accepted norms on various corporate governance related issues.Footnote 81 In particular, foreign shareholders may be more likely to prefer compensation packages in line with American practice in which incentive pay makes up a larger proportion. Finally, the proportion of inside and outside directors may also be a signal of adherence to more traditional norms about corporate governance. Companies with boards dominated by inside directors may be more likely to adhere to norms associated with the lifetime employment system. A company with a high proportion of outside directors who are not the product of the company’s internal chain of promotion are less likely to be bound by such norms. Moreover, since outside directors are, theoretically at least, intended to better represent the interests of shareholders, their greater presence may indicate a compromise between the board and shareholders over contested issues of governance, potentially including compensation.

Given the limited data available, we test specifically for how these factors may influence the content of compensation resolutions and J-SOP voting. This analysis represents an exploratory study, where determinants of executive compensation in Japan, particularly in recent years, are not well understood. In this instance, we can observe whether directors at different types of companies, for example larger companies or those with higher levels of foreign shareholding, ask for certain types of compensation above others. Likewise, we are able to ascertain relative compensation levels based on company types and characteristics, and shareholder vote favourability through J-SOP provisions. Based on the preceding observations, we begin with the following contentions:

H1: Higher levels of ROA, foreign shareholdings and company size encourage directors to ask for higher levels of compensation and a compensation structure with a higher composition of incentive pay than those in firms with lower ROA, foreign shareholdings and size.

H2: Higher levels of ROA, requests for incentive pay schemes and company size result in positive J-SOP voting. Conversely, increased foreign ownership results in less positive voting.

Hypothesis 1 considers the issue of director compensation, and the factors that may influence what levels and types of pay directors ask for. Conventional wisdom would dictate that directors at more profitable or larger companies, for example, would be more likely to ask for higher compensation. We would expect directors at companies with larger foreign ownership to ask for higher levels of compensation with more incentive based pay in light of the fact that foreign, and particularly American, shareholders are more accustomed to the more generous pay schemes prevalent outside of Japan.

Hypothesis 2, on the other hand, considers the J-SOP voting issue. We look specifically at whether company size, level of foreign ownership or ROA affect overall favourability to changes in director compensation. If there have indeed been significant changes to the dominant norms and supporting governance mechanisms at some Japanese companies, or if firms have been more or less profitable, we would expect considerable variation in J-SOP voting patterns.

B Methodology

To test our two hypotheses, we first run simple descriptive statistics in order to gain a basic understanding of company demographics, executive pay and J-SOP voting. We then run a series of comparisons, looking at director compensation, votes in favour and their associations with foreign ownership, type of compensation and company size. Finally, we run a multiple regression analysis considering linear associations between our independent variables, director compensation levels and votes in favour.

Total sample size in this instance is 649 individual filings, which represent 514 distinct companies. While the percentage of votes in favour is available in all instances, listings are not uniform in the information provided. Director compensation limits, for example, were only voted on in about 40 per cent of the cases. However, we feel that in most instances the sample size is sufficiently large to produce viable results, keeping the caveat of inconsistent reporting in mind.

It should be noted that the sample in this instance may raise questions over its representativeness of larger Japanese companies. By limiting the analysis to a single year, the possibility of bias does exist in the breakdown of inside versus outside directors, the types of compensation requested, and the voting levels recorded. Although anomalous data for the year considered is possible, the authors contend that the sample size is sufficiently large to overcome issues of extreme outliers and sample bias. Given the exploratory nature of this study, this article provides a necessary and useful snapshot of votes on executive compensation in Japan. While we do not expect to answer unequivocally whether the existence of Article 361 explains Japanese executive compensation, we do expect to provide some evidence of a relationship, as well as an understanding of how other factors may influence executive compensation as well.

C Results

1 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 below provides the variables considered along with their definitions, while Table 2 lists the descriptive statistics. From the beginning, we can see that votes in favour of compensation changes are quite positive, with a mean value of 92.30 per cent. Even the lowest vote in favour (51.15 per cent) is high enough to obtain a majority. However, most votes are firmly in positive territory.

Table 1 Variable Definitions

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics

In this analysis our estimate of inside and outside director pay is obtained by dividing the compensation limit stated by the number of directors in the relevant category. There may be significant differentiation between actual pay levels and the average estimation here, as individual director compensation may differ widely within the overall compensation limit. Directors may in fact be paid below the compensation limit as well. However, the average compensation rate does provide a reasonably uniform picture of executive pay, particularly since the executive pay level was, by definition, voted on in that year. If compensation levels were far below the limit stated here, they would be unlikely to have held a vote in the first place. We find average inside director approved pay to be at 28.16 million yen per year, while average outside director approved pay is 12.27 million yen per year. In other words, inside directors are paid on average more than twice that of outside directors. This figure excludes bonuses, stock options and retirement cash outs.

Votes on inside and outside director compensation limits provide relatively large samples to work with, where inside director pay comprises the largest grouping (N=272). Outside director pay is a more modest sample (N=74), although it presents a large enough pool for the purpose of this study. Also included in the data, although excluded from the present analysis, were votes on auditor compensation limits. The auditor sample size was smaller than inside and outside director compensation limit votes (N=48), with an average auditor compensation rate calculated at 2.3 million yen per year and a standard deviation of 3.36 million yen. Although auditor pay certainly merits future consideration, due to the smaller sample size, general lack of variability, and in the interest of a more focused analysis, we opted to exclude it from the present discussion and focus on compensation issues relating exclusively to directors.

Another measure considered and ultimately excluded from this analysis was inside and outside director number and proportion as independent variables. While we used a company’s inside and outside director number to calculate their average approved pay rate, we also considered whether actual numbers of directors, as well as the proportion of inside versus outside directors as a means of controlling for company size, had any association with votes in favour of J-SOP provisions. Based on preliminary correlation and regression analysis, we found that director number and inside and outside director proportion have no significant association with J-SOP vote favourability. We consequently opted to exclude this factor from the present discussion as well.

A final factor excluded from the present analysis is the primary field of business each company was engaged in. Our review of filing data showed 20 distinct business categories, including a diverse array of areas such as banking, machinery, pharmaceuticals and a variety of others. Given the wide berth of business activities that defy simple categorization, we opted here to omit industrial sector for the sake of analytic simplicity.

For our measure of foreign shareholding, 38 per cent of the sample filings (N=244) have less than 10 per cent of their shares owned by a foreign person or entity, 29 per cent (184) have between 10-19 per cent foreign shareholders, 15 per cent (99) have 20-29 per cent foreign shareholding, and 18 per cent (113) have 30 per cent or more foreign shareholders, thus providing a good sample size in each category.

Company size is based on the company’s listing index, where ‘small companies’ are comprised of members of the TOPIX Small 1 index, ‘medium companies’ are listed on the TOPIX Mid-400 and Small 2 indexes, and ‘large companies’ include those on the TOPIX Core-30 and Large-70 indexes. 42 per cent (271) of the sample are small companies, 50 per cent (327) are medium-sized, and 7 per cent (45) are large companies. Note that while large companies encompass a comparatively smaller pool, our sample includes almost half of the companies in this category.

ROA is derived from each company’s Worldscope Company Report for the end of the fiscal year immediately preceding the shareholders meeting. We include it here as a measure of profitability, with average ROA at 4.74 per cent, although there is considerable variability as one might expect. Return on equity data was also available, although the sample size was somewhat smaller and results were highly similar to ROA data. Consequently, we opted to include ROA data in this instance.

Finally, we include a number of dummy variables considering the types of payment resolutions voted on. We consider the adoption of an ‘incentive pay’ scheme first, which include resolutions covering performance bonuses, other types of performance-based compensation, and stock options. This is contrasted with what we consider to be ‘standard pay’, including compensation limits, retirement pay, and a small grouping of other categories such as condolence pay in the event of a director’s death. We then classify the payment schemes into five broad categories: whether resolutions were considered for compensation limits, bonus pay, retirement bonuses, retirement cash out, and stock-based payment. Votes on compensation limit pay cover 18 per cent of the sample (119), bonus pay is 32 per cent (205), retirement bonus is 30 per cent (196), retirement cash out pay is 7 per cent (49), and stock-based pay is 12 per cent (80). Based on the size of these subsamples, we feel the results are suitable to provide a reasonable indication of their associations with director compensation and J-SOP voting.

2 Comparisons

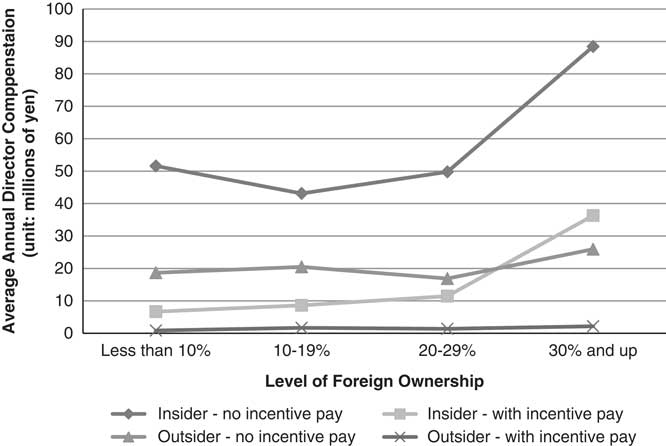

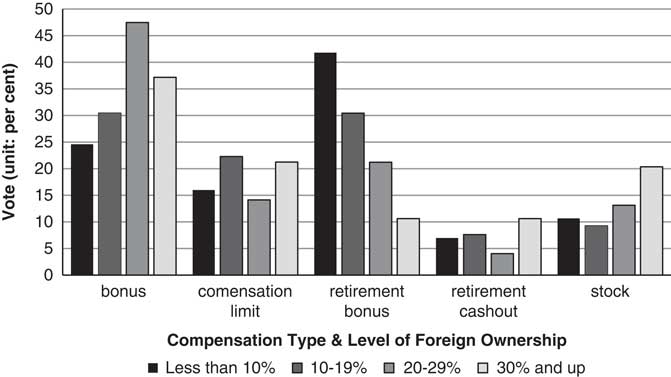

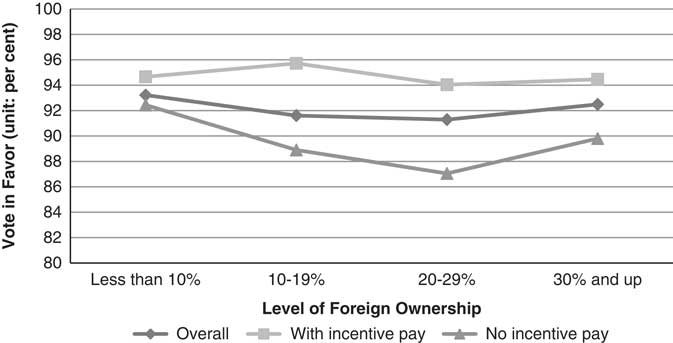

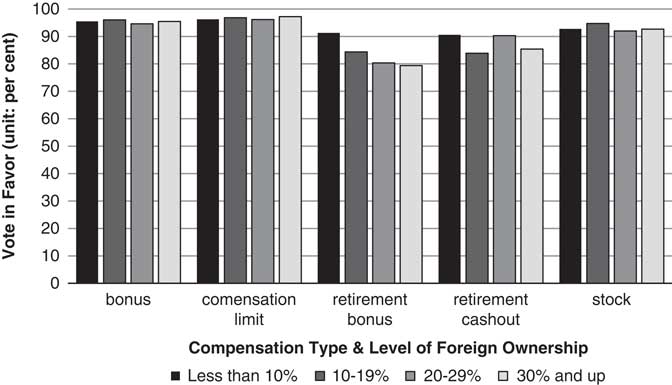

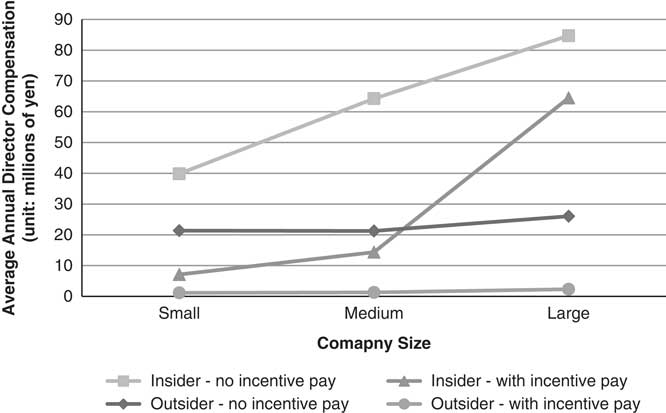

Next, we turn to more detailed comparisons, starting with how levels of foreign ownership associated with director compensation and votes in favour. Figure 1 below demonstrates levels of foreign ownership combined with average inside and outside director compensation. Figure 2 looks to types of voting according to foreign ownership level. Figure 3 illustrates levels of foreign ownership combined with incentive pay schemes and votes in favour, while Figure 4 considers overall votes in favour, divided according to foreign ownership and type of payment scheme being considered.

Figure 1 Executive Compensation by Level of Foreign Ownership

Figure 2 Vote on Compensation Type by Level of Foreign Ownership

Figure 3 Vote in Favour by Foreign Ownership and Incentive Pay

Figure 4 Vote in Favour by Level of Foreign Ownership and Compensation Type

The figures below reveal some obvious trends. Figure 1, for example, demonstrates a clear upward movement in executive compensation according to level of foreign ownership. Directors at companies with higher levels of foreign ownership appear to ask for higher average levels of compensation. Additionally, there is a strong difference in compensation levels for companies adopting incentive pay schemes compared to those with more traditional means of director compensation. Directors receiving incentive pay obtain substantially lower average compensation, although this discrepancy is presumably accounted for in bonus and/or stock pay.

Looking to types of compensation voting by foreign ownership in Figure 2, we can see that while the bonus and retirement bonus categories were the most commonly considered in this instance, there appears to be a distinct pattern in voting type according to level of foreign ownership. That is, firms with higher levels of foreign ownership look much more likely to vote on bonus pay, while firms with lower levels of foreign ownership appear more likely to consider retirement bonuses. Compensation limits appear to be relatively evenly split, although retirement cash outs and stock options in particular are also more common amongst firms with higher levels of foreign ownership. There consequently seems to be a reasonably strong association between foreign ownership and incentive pay schemes.

Moving to a consideration of ‘say on pay’ votes in favour, Figure 3 draws distinctions based on foreign ownership and incentive pay schemes. While voting is quite positive overall, there is a clear difference in level of positivity and whether or not an incentive pay scheme was being considered. Votes in favour appear much more positive when incentive pay is considered, with a marked difference based on foreign ownership. The difference in positivity between incentive pay voting and standard pay voting appears less pronounced for firms with lower levels of foreign ownership.

Figure 4 looks at the same votes in favour, broken down by compensation type. Once again, voting is uniformly positive, although there is some variation, particularly for retirement bonus payments. Companies with higher levels of foreign ownership appear to be somewhat less favourable to retirement bonus payments, although overall votes in favour still hover around the 80 per cent mark. Interestingly, companies with higher levels of foreign ownership appear less likely to consider retirement bonuses and are much less favourable toward them when they are considered.

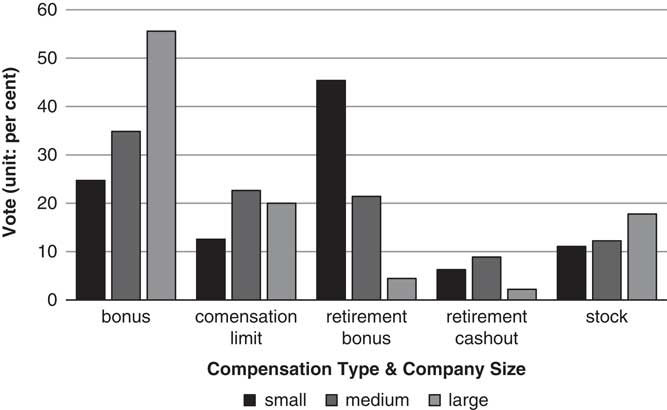

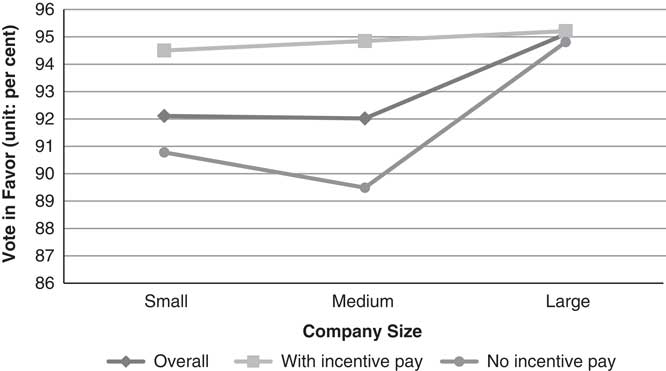

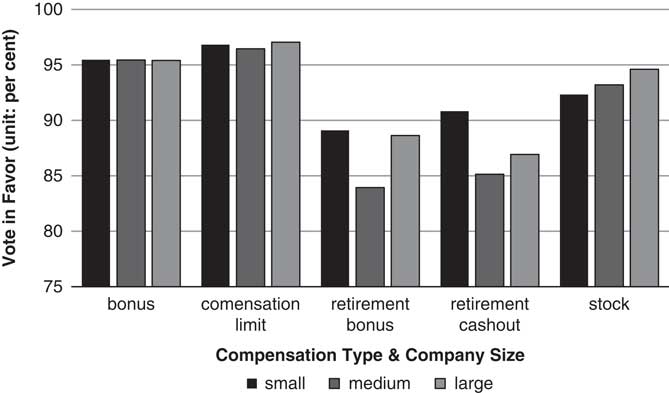

From a somewhat different perspective, Figures 5 through 8 examine the same factors of director compensation and votes in favour, but in this case through the lens of company size. It should be noted that there is substantial endogeneity between company size and foreign ownership, where 72 per cent (192 out of 266) of small company filings have less than 10 per cent foreign ownership, and 84 per cent (38 out of 45) of large company filings have 30 per cent foreign ownership or higher. However, the characteristics and dynamics of business size are distinct from levels of foreign ownership, and merit their own consideration. We are additionally able to control for both foreign ownership and company size when running the regression analyses. Figure 5 looks at average executive compensation levels by incentive pay and business size, Figure 6 considers the vote on compensation type by company size, while Figure 7 illustrates votes in favour by incentive pay and company size, and Figure 8 provides votes in favour according to compensation type and company size. In essence, Figures 5 through 8 look at the same issues as Figures 1 through 4, but divided according to company size rather than foreign ownership.

Figure 5 Executive Compensation by Company Size

Figure 6 Vote on Compensation Type by Company Size

Figure 7 Vote in Favour by Company Size and Incentive Pay

Figure 8 Vote in Favour by Company Size and Compensation Type

As with classification by foreign ownership, we can see in Figure 5 that there is a strong dichotomy between incentive and standard pay schemes, with directors at larger companies asking for substantially larger average compensation regardless of type. Higher average pay is also requested for outside directors in larger corporations, but only marginally. Type of compensation vote by company size, shown in Figure 6, paints a picture similar to Figure 2: that directors at larger companies are much more likely to favour incentive-based pay schemes, while directors at smaller companies favour more traditional means of compensation. Figure 7, considering votes in favour and incentive pay, illustrates a much stronger difference in favourability according to company size and pay scheme compared to Figure 3. While there is an obvious upward trajectory in voting when moving from small to large companies, small and medium-sized companies without incentive pay appear to be much less favourable (although still quite positive overall) on the votes in question. Finally, Figure 8 demonstrates clear differences in favourability for compensation type according to company size. Across the board, votes seem much more positive for bonus and compensation limit pay and somewhat less positive toward retirement bonuses and retirement cash outs. These votes do not follow clear trends based on company size, although stock options appear to be more favourable to larger companies according to this data.

While these comparisons provide reasonably straightforward evidence of trends in executive compensation and votes in favour based on J-SOP provisions, they do not demonstrate statistically significant associations. We next turn our attention to regression analyses, looking to the effect that foreign ownership, company size, and ROA may have on executive compensation and votes in favour of compensation change.

3 Regression Analysis

Moving onto significance testing, we start with a simplified linear regression model, shown below in Table 3. The regression includes three sub-models, looking at factors affecting inside and outside director compensation, as well as overall votes in favour of the compensation change. Independent variables include dummy variables for level of foreign ownership, with the lowest level as the baseline value, dummy variables for company size using medium company as the baseline, ROA, and a final dummy variable for adoption of an incentive pay scheme. Note that as Models 1 and 2 aim to find factors influencing average director pay, listings that did not include compensation limits for the relevant category were omitted from the analysis.

Table 3 Estimation Results

Standard errors are reported in parentheses. * p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01

Looking first to inside director compensation, we can see that the average rate of pay is 52.88 million yen according to this data, and is significantly higher at companies with the largest shares of foreign ownership. Large companies additionally have a significant and positive association with inside director compensation, while incentive pay schemes are significant and negatively associated with director compensation. In spite of removing some listings, sample size is reasonably large, and the R-squared value demonstrates reasonable explanatory power. Outside director compensation shows associations similar to inside director compensation, albeit with a lower general pay level. The R-squared value is deceptively high, owing to the relatively small sample size in this instance. It would appear, however, that outside director compensation seems to be influenced in the same relative ways as inside director pay.

Votes in favour are considered last in this model, attaining both the most significant associations and the lowest R-squared value. According to this model, most independent variables are in fact statistically significant, although the coefficients are in general fairly small. The baseline vote in favour is 92.38 per cent for a medium-sized company with little foreign ownership and no incentive pay. All higher levels of foreign ownership are in fact significantly less favourably disposed, but only between 2 and 4 per cent. Small companies show less favourability, while large companies appear more favourable. Incentive pay schemes in this instance bring the largest change, moving votes in favour up almost 5 per cent. It is additionally worth noting that ROA has no effect on favourability.

To check the robustness of these findings, we ran these same regression models making foreign shareholding and company size continuous rather than dichotomous variables, increasing in value for larger levels of foreign shareholding and company size. The results of this robustness check were largely in line with the regression results provided here.

While the preceding regression analysis provides some indication of factors that influence director compensation and J-SOP votes in favour, the data allow us to parse out the various types of payment schemes further. Where the previous regression model considers incentive pay broadly, here we expand the model to include dummy variables for each type of payment, using the compensation limit payment as the baseline value.

Expanded regression results in Table 4 provide an increase in R-squared values across the board, indicating that this combination of variables holds somewhat greater explanatory power. Interestingly, ROA fails to provide any significant association again in this instance, and all constant values retain their significance.

Table 4 Estimation Results – Expanded

Standard errors are reported in parentheses. * p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01

Looking first to inside director compensation, baseline pay is estimated at 53.66 million yen per year for a medium-sized company with little foreign ownership and considering adjustment to the compensation limit. Higher levels of foreign shareholding remain significant and positively associated, although in this case at the 90 per cent confidence level. Company size also retains significance, with small companies now demonstrating a negative association at the 90 per cent confidence level as well. Most interesting, perhaps, is the division of pay schemes. Both bonus pay and stock pay, the primary incentive pay schemes considered, have strong negative associations with inside director pay. As noted previously, directors asking for approval of incentive pay schemes appear to ask for lower compensation limits on average, although this has the potential to be made up for in bonus and/or stock payment.

Outside director pay shows the same basic trends, although this model has lower levels of significance throughout due again to the smaller sample size. Outside directors request considerably less pay on average than inside directors, and have a much lower average compensation level when receiving bonus pay.

Lastly, votes in favour retain the same generally high levels of significance, in some cases with stronger associations. In this instance, higher levels of foreign ownership are again negatively associated with favourability between 2 to 4 per cent. All types of compensation are also much less favourable compared to the compensation limit baseline, with retirement bonus pay and retirement cash out pay being almost 10 per cent less favourable and strongly significant. A robustness check collapsing foreign shareholding and company size into separate continuous variables again yields similar results.

It should be noted that the potential for multicollinearity between independent variables exists, particularly between company size and level of foreign shareholding, where larger companies in Japan tend to have greater numbers of foreign shareholders. While this may raise some questions about the effect individual predictors may have in a regression equation, tests omitting either the company size or foreign shareholding variables yield largely similar results. We include the full model here with the caveat that independent variable coefficients should be interpreted with some degree of caution, but that the overall associations hold true.

D Discussion

Where do these results leave our hypotheses, and more broadly what do we find influences the types of compensation requests directors make and how shareholders react to them? Looking back to hypothesis 1 (ie, that higher ROA, incentive pay, company size and foreign ownership results in higher executive pay), we find that higher levels of foreign ownership do tend to result in directors asking for higher compensation, as does larger company size. Incentive pay schemes are strongly associated with lower average base pay levels, while profitability shows no significant relationship. These factors hold true across inside and outside director compensation. Aside from incentive pay, the strongest influences on what compensation directors ask for appear to be company size and level of foreign ownership, although there is still a considerable amount of compensation that remains unexplained by the models considered. There are likely other factors influencing compensation decisions, although interestingly profit does not appear to be a significant issue.

We can discern a few points regarding director compensation requests from this data. For one, directors at larger companies, and by consequence companies with higher levels of foreign ownership, appear much more likely to ask shareholders to approve incentive pay schemes while those at smaller, more domestically-controlled companies, tend to favour conventional means of compensation. This provides further evidence of a divergence in norms on compensation in Japanese corporate governance between larger companies with greater exposure to foreign investors on the one hand and smaller, more domestically focused companies, on the other.

Looking to our second hypothesis (ie, that higher profitability, requests for incentive pay, and company size bring more favourable voting, while greater foreign ownership brings more negative voting), we find that larger company size does in fact influence more favourable voting, while greater foreign ownership and incentive pay bring less favourable voting when pay types are examined individually. Again, profit does not seem to be a factor.

As expected, higher levels of foreign ownership do introduce a more negative voting sentiment, which is consistent with the theory that foreign shareholders have views on compensation that diverge from both those of directors and of domestic shareholders, and this is reflected in their voting patterns. Even when controlling for company size, the negative sentiment introduced by higher foreign ownership more than compensates for the relatively higher levels of positivity larger companies may have.

What does all of this say about the significance of the J-SOP rule in determining compensation? Does it encourage the board to submit pay proposals in line with the expectations of its shareholders, as our data indicates generally happens? The data do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions on causation – it is equally plausible that the threat of a negative shareholder vote drives their decision making as it is that their own views on compensation formed owing to some other factor drives it. At the same time, however, based on the evidence it seems quite likely that the existence of the rule is one factor, and in some cases a major factor, in decision making the board carries out in making pay requests. The dissenting votes exhibited in some of the resolutions in this study carry a cost for directors. Such votes can act as signals to the broader market of problems at a company that invite greater levels of outside scrutiny. The need to put them to a vote in an open public forum like the shareholders meeting also gives shareholders the power to move potentially awkward questions on compensation to that forum where directors are legally required to provide informative answers.Footnote 82 Cases in which directors have sued the company after the board submitted resolutions for retirement bonuses that were lowered to reflect involvement in scandals or poor performance also indicate a sensitivity to sending potentially controversial pay requests to shareholders.Footnote 83

We also see certain signs of shifts in pay practice which are in line with shareholder voting required by the J-SOP rule. Retirement bonuses in particular attracted high levels of negative voting across companies of all sizes and the large number of votes held on cash outs associated with the abolishment of such bonuses indicate a growing trend away from them. The fact that the rule makes retirement bonuses contingent on future decisions by both the board and shareholders meeting, which makes them less certain to directors, is likely another way the rule is influencing this shift.

What we are left with is the picture that the J-SOP rule clearly does provide an avenue through which some shareholders can and do express dissent against director pay requests while directors structure their requests differently based on the characteristics of both. Where the model of pay sought by directors – either incentive based (ie, greater reliance on stock options and bonuses) or stable (ie, greater reliance on base salary and retirement bonus) – matches well with the preferences of its shareholders, as it appears to do at the vast majority of companies examined, voting on J-SOP resolutions is largely uncontroversial. But where these do not align well, the existence of the rule does give shareholders a feedback mechanism with which they can signal their discontent with how directors wish to be compensated, as evidenced for example by companies with higher proportions of foreign shareholders experiencing much higher dissenting votes against resolutions seeking approval of retirement bonuses. While these findings may be interesting in their own right, what is most striking about J-SOP vote results is their extreme positivity. Even at the lowest levels, average votes in favour rarely dip below 80 per cent. Firms with higher levels of foreign ownership may be somewhat more negative than Japanese-dominated companies, but such negativity is not enough to change the ultimate outcomes of votes on J-SOP resolutions.

V CONCLUSION

This article sought to fill a gap in the literature on executive compensation in Japan by examining the J-SOP rule contained in Article 361 of the Companies Act. Our main finding is that the simple explanation for its potential relevance – that shareholder use of the rule explains the level and structure of pay in Japan – is inadequate. All of the pay requests directors put to shareholders meetings examined herein were approved, a finding that would seem incompatible with the theory that the J-SOP rule is being used to effectively police pay. We do, however, find that such requests, and shareholder responses to them, vary considerably across companies. Directors at larger companies with greater proportions of foreign shareholders tend to ask for compensation with a greater component of incentive pay, while those at smaller companies with lower proportions of foreign shareholders tend to request pay in the form of base salary and retirement bonuses. While dissenting shareholders are unable to use the provision to defeat director pay requests they disagree with, significant minority blocks of shareholders do at times vote against them. The fact that a negative vote denies directors legal claims for the pay in question suggests that the existence of such a threat cannot be ignored, particularly in light of the increasingly international character of shareholders at some large companies, and may form part of the calculus directors consider when tailoring their pay requests.