Introduction

On December 7, 2022, President Pedro Castillo declared the dissolution of the Peruvian Congress while facing his second impeachment proceeding in less than two years. Within hours of his decision, he was ousted, and Vice-President Dina Boluarte took his place. This event marked Castillo as the second Peruvian president to dissolve Congress within two years. With the impeachment of President Dina Boluarte in October of 2025, Peru’s record included four presidential impeachments and two attempts to dissolve Congress in seven years. Five months earlier, on May 17, 2023, less than 1,200 miles north of Lima, President Guillermo Lasso of Ecuador used his constitutional prerogative to invoke the country’s “mutual death” rule. By doing so, he dissolved Congress and called for new general elections. Like Pedro Castillo, Guillermo Lasso was in the middle of impeachment proceedings for the second time in less than two years. Legal or illegal, the attacks on Congress and the presidency were interpreted differently by supporters of the incumbent presidents and the opposition. In highly polarized political environments, legally suspect or legally sound strategies often split partisans based on their political preferences rather than the merits of the case.

The examples of Castillo in Peru and Lasso in Ecuador are not isolated events. Indeed, they exemplify a broader trend of assaults on opponents controlling democratic institutions by out-group partisans across Latin America. While presidential impeachment is sometimes warranted (as in the case of Castillo) and the dissolution of Congress might be a legal prerogative of the president (as in the case of Lasso), there is little doubt that voters’ interpretations of these events—and their willingness to transgress democratic institutions—are shaped by partisan self-interest.

Unlike the authoritarian reversals of the twentieth century in Latin America, today’s democratic recession is increasingly driven by partisan attacks on the institutions of the presidency and Congress (Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007, Reference Pérez-Liñán2018). Affective polarization among elites and voters, fueled by in-group loyalty and out-group hostility, intensifies uncivil political aggression (Reiljan et al. Reference Reiljan, Garzia, Da Silva and Trechsel.2024; Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne.2023; Mason Reference Mason2018). This trend is not unique to Latin America. Public assaults on democratically elected executives and legislatures have been documented globally (Svolik Reference Svolik2019; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik.2020; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021). In the United States, opposition legislators have repeatedly initiated impeachment resolutions or inquiries against presidents, and the House of Representatives has formally voted on articles of impeachment three times—once for Bill Clinton and twice for Donald Trump. As Jacobson shows, public opinion consistently treated impeachment as a partisan wedge issue dividing Democrats and Republicans (Jacobson Reference Jacobson2020).

A growing body of research shows that affective polarization has also become an increasingly salient feature of Latin American politics, reshaping how citizens evaluate parties, leaders, and institutional conflict (McCoy Reference McCoy2024). Regional analyses document a clear upward trend: affective and ideological divides widened across many countries in the region over the past two decades, even if the overall levels remain below those observed in some European or North American cases (Bergman and Fernández Reference Bergman and Fernández.2025; Moraes and Béjar Reference Moraes, Torcal and Harteveld2025; McCoy Reference McCoy2024). Country-specific studies reinforce this regional pattern. Brazil experienced a marked escalation in partisan hostility from the early 2000s through the Bolsonaro era (Orhan Reference Orhan2022), while Chile has seen deepening affective distance between left- and right-identifying citizens (Comellas and Torcal Reference Comellas and Torcal.2023). This literature indicates that Latin America is undergoing meaningful and sustained increases in affective polarization, with sharper in-group favoritism and out-group animus. These are precisely the conditions under which citizens become more willing to justify hardball tactics against their “enemies,” reinterpret institutional rules to favor their preferred actors, and excuse democratic transgressions when they benefit their own side.

At the same time, scholars debate whether affective polarization in the region is primarily partisan or instead organized around charismatic, polarizing leaders. Evidence from Brazil suggests that political animus is often anchored in attitudes toward individual figures such as Lula or Bolsonaro rather than in enduring party identities alone (Areal Reference Areal2022). In Chile, affective polarization persists even among non-partisans, indicating that strong emotional divides can flourish despite weaker party attachments (Segovia Reference Segovia2022). This pattern contrasts with established party systems, where affective polarization typically tracks partisan identification (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018; Lupu Reference Lupu2016; Luna et al. Reference Luna, Rodríguez, Rosenblatt and Vommaro.2021). These dynamics make Latin America an especially important setting for studying how citizens interpret confrontations between the presidency and Congress. Our study builds directly on this debate by testing the effect of partisan preferences on transgressing against democratic institutions.

This article outlines three survey experiments in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia designed to assess partisan divides in support for either presidential impeachment or the dissolution of Congress. This contrast between president versus Congress is especially salient because in all three cases the presidents governed without secure legislative majorities. As a result, government and opposition partisans may view the aligned institution as a protection against the out-group. Making this background clear from the outset helps situate why impeachment and dissolution are perceived as credible—and politically charged—possibilities by respondents. We focus on the interaction between affective polarization, exposure to partisan social media messages, and support for transgressions against core democratic institutions. Prior work shows that polarization can reduce citizens’ ability to hold leaders accountable for illiberal or undemocratic actions (Svolik Reference Svolik2019; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik.2020; Roberts Reference Roberts2014; Corrales and Penfold-Becerra Reference Corrales and Penfold-Becerra.2007; McCoy and Somer Reference McCoy and Somer.2019). Such dynamics often manifest in diminished support for political tolerance and constitutional safeguards (Mason Reference Mason2018; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood.2015; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt.2018; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021). Yet it remains unclear whether short-term spikes in affective polarization—triggered by partisan messaging—are sufficient to heighten support for key markers of democratic erosion, including uncivil discourse, political intolerance, and endorsement of institutional transgressions (Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Carreras and Merolla.2022; Broockman and Kalla Reference Broockman and Kalla.2022; Broockman et al. Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood.2023).

We examine the impact of partisan messages on citizens’ support for democratic institutions of the presidency and Congress. Specifically, we investigate whether those in opposition are more inclined to resist undemocratic intrusions on Congress while endorsing undemocratic transgressions against the executive. Similarly, we test whether supporters of the government resist calls to impeach the president but accept the dissolution of Congress. Footnote 1 Therefore, our research explores how citizens react to partisan content and whether they are willing (or not) to encroach on democratic institutions (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2011).

To this end, we conducted survey experiments in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia between November 2022 and March 2023. Respondents were randomly assigned to a treatment or control group. In the treatment condition (two-thirds of respondents), participants viewed Facebook-style posts attributed to government officials addressing salient political issues such as voting, inflation, abortion, crime, unemployment, and protests. They then answered questions about presidential impeachment and congressional dissolution. In the control (one-third of respondents), participants answered the same questions before being exposed to the posts. This design allows us to assess the impact of partisan social media messages on willingness to engage with such content (e.g., sharing, liking) as well as on illiberal attitudes toward democratic institutions. All hypotheses were preregistered in country-specific plans deposited at https://osf.io/ and are reproduced in the Supplemental Information File (SIF). The analyses presented here follow those pre-registered plans.

The results confirm the expected partisan divide in baseline attitudes: opposition voters were more likely to support presidential impeachment, while government supporters favored dissolving Congress. Yet exposure to partisan social media messages produced no consistent effects. Both incumbent and opposition voters expressed illiberal preferences aligned with their partisan orientation, but these attitudes did not significantly increase following treatment. These null results contribute to a growing body of persuasion research showing that partisan messages often fail to shift political attitudes, even in polarized contexts (Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman.2018; Guess and Coppock Reference Guess and Coppock.2020). Our study extends this literature by showing that short-term partisan cues do not easily erode or reinforce citizens’ willingness to endorse democratic transgressions.

Partisan Messages and Support for Democratic Institutions

In recent years, signs of democratic recession have been widespread, sparking concerns about possible autocratic reversals (Diamond Reference Diamond2021; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt.2018). Democratic recession refers to the gradual decline in the quality of democratic institutions, often involving media censorship and harassment, curtailing civil liberties and party competition, and undermining the independence and autonomy of election management bodies (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg.2019).

The public willigness to accept transgressions on the institutions controlled by outgroup members is key to democratic recession. To gain public support, populist leaders often engage in uncivil discourse, portray out-group officers and candidates as corrupt and disloyal, and vilify media organizations as propagators of ”fake news” (Waisbord Reference Waisbord2018; Diamond Reference Diamond2021). Voters may internalize and propagate these messages, perceiving out-party members as extreme, prejudiced, and undemocratic (Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood.2015). Therefore, understanding how citizens respond to partisan content and their willingness to transgress democratic institutions has become central to recent research efforts (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2011).

Scholars have long recognized that deep social divisions, or polarization, pose significant risks to democracy. Dahl (Reference Dahl1971) warned of the dangers arising from a polarized society, and Linz (Reference Linz1978) argued that deep social cleavages could lead to the collapse of democratic regimes. Richardson (Reference Richardson1991) highlighted that stable partisan ties and hostilities toward opposing parties reinforce polarization, while Kelly (Reference Kelly1993) warned about the risks of strong in-group identification. In multiparty systems, Comellas and Torcal (Reference Comellas and Torcal.2023) found that identity-based ideology increases the emotional distance between ideological blocs more than issue extremity or consistency, ultimately leading to affective polarization. Survey data also shows that affectively polarized voters often compromise their democratic principles to ensure in-group partisan outcomes (Svolik Reference Svolik2019; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik.2020; Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021). Indeed, voters often condone the illiberal tendencies of in-group politicians, reducing their support for the principles, norms, and institutions that are the essence of democratic life.

Three approaches are most prominent when measuring democratic recession. Taken together, these approaches suggest that partisan attachments condition how citizens evaluate democratic institutions. When partisan identity and affective polarization are activated by social media cues, opposition voters may become more likely to endorse impeachment, while government supporters may become more accepting of dissolving Congress. Our hypotheses, therefore, build directly from this logic. Three different sets of theories have sought to explain how polarized partisan messages affect trust in democracy, respect for democratic norms, and tolerance towards out-group elected officials. All three theories suggest that activating partisan identities is likely to increase the odds of impeachment by affecting the trustworthiness of out-group leaders, lowering respect for democratic institutions and norms, and hightening the dislike for members of out-group parties.

How Uncivil Content Lowers Trust in Democracy

The first one relies on measuring citizens’ satisfaction with democracy. Norris (Reference Norris2011) explains a rising democratic deficit resulting from increased skepticism toward the political system. Using survey data from the fifth wave of the World Values Survey (2005–7), Norris (Reference Norris2011) finds support for the existence of a gap between expectations and satisfaction with liberal democracies worldwide. Related research in Latin America highlights the role of regime performance and political culture in shaping satisfaction and legitimacy (Booth and Seligson Reference Booth and Seligson.2009; Carlin and Singer Reference Carlin and Singer.2011). While expectations about democratic systems continue to grow, satisfaction has, at best, remained stable (Norris Reference Norris2011).

How Uncivil Content Increases Support for Transgressing Democratic Norms

A second approach emphasizes citizens’ adherence to and commitment toward democratic norms and principles (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik.2020; Svolik Reference Svolik2019). Scholars infer commitment to democratic principles based on respondents’ choices in hypothetical election scenarios. Svolik (Reference Svolik2019), for example, shows that voters are partisans first and democrats second, prioritizing partisan interests in more polarized electoral scenarios. Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik.2020) extend this line of research, finding that in polarized elections, only a small fraction of US citizens prioritize democratic principles. Similarly, comparative analyses underscore how partisan and ideological attachments condition democratic commitments, as Singer (Reference Singer2018) shows that citizens who feel well represented by an ideologically sympathetic executive are more willing to delegate additional authority to the president, even at the expense of institutional checks.

How Uncivil Content Heightens the Dislike for the Out-party

The third and final approach focuses on citizens’ support for constitutional protections and political tolerance. Kingzette et al. (Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021) examined how affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms in the United States within the context of the 2019 and 2012 elections. They posited that affectively polarized voters compromise their support for democracy through two distinct mechanisms: (i) following cues from elites in power about which norms to oppose, thereby becoming less inclined to support constitutional protections, and (ii) they are likely to perceive out-party politicians as adversaries, thus becoming less inclined to support political tolerance (Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021). Cross-national evidence also shows how identity, polarization, and partisan incentives affect willingness to tolerate opposition and preserve institutions (Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Popa, Hobolt and Schmitt.2021; Jacob Reference Jacob2025). Broader structural work similarly highlights the role of inequality and elite strategies in conditioning democratic legitimacy (Albertus Reference Albertus2023).

Taken together, these literatures suggest that a combination of trust, principled commitments to norms, and tolerance for members of the out-party shapes support for democratic institutions. We test the third mechanism most directly in this article, while acknowledging that our contribution complements these broader perspectives by examining whether short-term exposure to partisan messages on social media increases negative emotions towards the out-party and increases citizens’ willingness to transgress democratic institutions for partisan gain.

It is important to note that while impeachment may be legally contested and sometimes warranted, the dissolution of Congress is unequivocally unconstitutional in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. We therefore analyze them separately, focusing on how activating partisan identities increases (or not) support for each. Moreover, while impeachment is, in principle, a democratic mechanism, our study captures its undemocratic use—that is, support for removal based solely on disagreement with presidential policies, rather than on legal or constitutional grounds. In the countries analyzed in this article, such a policy mismatch would not constitute grounds for impeachment, as in Brazil, Colombia, and Chile; impeachment is prescribed in the constitution and requires serious misconduct or violation of the constitution.

Hypotheses

We designed our experiments to measure support for impeachment and for the dissolution of Congress on a five-point scale. Our central interest is whether exposure to partisan social media posts generates a wedge response that divides pro-incumbent and opposition supporters. Following the partisan responses discussed in the previous section, and building on the partisan cue-taking theory by Kingzette et al. (Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021), we examine citizens’ support for dissolving Congress or impeaching the president in response to explicit policy disagreements, rather than ”crimes or misdemeanors.”

We hypothesize that supporters of the incumbent president will be more willing to act against Congress, whereas supporters of the opposition will exhibit a greater inclination to impeach the president. This pattern is consistent with research in the United States, which shows that impeachment has become a partisan wedge issue that divides Democrats and Republicans (Jacobson Reference Jacobson2020). The wording of our impeachment item reads: “If the President’s policy does not align with the preferences of [Chileans/Brazilians/Colombians], Congress should remove the President from office.” This phrasing suggests impeachment is considered solely on the basis of policy congruence, without any implication of legal wrongdoing. In all three countries, impeachment on these grounds would be unwarranted and illegal.

For Congress, respondents were asked: “When the country faces serious difficulties, it is justifiable for the president to dissolve Congress.” The rationale provided is vague and attributes the decision solely to the president. In Brazil, Chile, and Colombia, however, dissolution of Congress is unequivocally unconstitutional, and no legal provisions give such prerogatives to the executive. We therefore analyze impeachment and dissolution as distinct outcomes, while presenting parallel hypotheses for each.

The first set of hypotheses evaluates baseline partisan divides in attitudes toward democratic institutions. Prior work on satisfaction with democracy and principled commitments shows that support for institutions is strongly conditioned by partisan attachments: voters tend to be partisans first and democrats second (Svolik Reference Svolik2019; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik.2020). This implies that citizens are more tolerant of undemocratic actions that disadvantage out-partisans, while opposing those that hurt their own side. In Brazil, Chile, and Colombia, presidents governed without a majority of legislative seats, creating opportunities for partisan confrontation. In Colombia, while President Gustavo Petro’s party (Pacto Histórico) lacked a majority on its own, he initially secured support from a broad coalition that gave him effective majorities until mid-2023. Only after this coalition fractured did the country move closer to a scenario of divided government. Accordingly, our first set of hypotheses reads:

HT1a: Opposition voters will be more likely to report a preference to impeach the incumbent president than government supporters.

HT1b: Government supporters will be more likely to report a preference to dissolve Congress than opposition voters.

The second set of hypotheses considers the causal effect of partisan social media posts. Building on research showing that affective polarization erodes democratic commitments (Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan.2021; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Popa, Hobolt and Schmitt.2021; Albertus Reference Albertus2023; Jacob Reference Jacob2025), we test whether short-term exposure to partisan messages in the form of Facebook-style posts activates negative emotions—especially anger—reinforces partisan predispositions, and increases willingness to endorse impeachment or dissolution. While these cues may heighten partisan hostility, prior persuasion experiments often report null results (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron.2018; Guess and Coppock Reference Guess and Coppock.2020), raising the possibility that even strong partisan messages may fail to shift institutional attitudes. Our second set of hypotheses reads:

HT2a: Opposition voters will report a higher willingness to impeach the president after exposure to partisan messages.

HT2b: Government supporters will report a higher willingness to dissolve Congress after exposure to partisan messages.

It is important to note that our hypotheses are grounded in literature documenting rising levels of affective polarization in Latin America, even if the region is not as severely polarized as some European or other global contexts (Bergman and Fernández Reference Bergman and Fernández.2025). For instance, Moraes and Béjar (Reference Moraes, Torcal and Harteveld2025) find that political polarization in the region increased between 2000 and 2021. McCoy (Reference McCoy2024) highlights the growth of both identity-based and issue-based polarization across Latin American countries using descriptive statsitics. Country-specific studies also illustrate this trend: Orhan (Reference Orhan2022) shows that Brazil experienced rising polarization between 2002 and 2018, while Comellas and Torcal (Reference Comellas and Torcal.2023) document increasing affective polarization between left- and right-leaning citizens in Chile. These findings suggest that although Latin America may not yet exhibit the extreme levels of polarization observed elsewhere, the region is experiencing a meaningful upward trend that provides a relevant context for examining citizen responses to political crises, such as impeachment and the dissolution of Congress.

While the literature documents rising affective polarization in Latin America, there is an ongoing debate about whether this polarization is primarily partisan or more personalistic, centered on individual leaders. In Brazil, for example, Areal (Reference Areal2022) finds that polarization is largely driven by negative political identities associated with figures like Lula and Bolsonaro, although the PT as a party still contributes. In Chile, Segovia (Reference Segovia2022) documents high affective polarization even among non-partisan citizens, while partisans themselves remain highly polarized. This contrasts with contexts with strongly institutionalized party systems, where affective polarization tends to align closely with party identification (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018; Lupu Reference Lupu2016; Luna et al. Reference Luna, Rodríguez, Rosenblatt and Vommaro.2021). Our article contributes to this debate by examining how citizens’ attitudes toward the presidency and Congress interact with these different forms of polarization. By testing treatments that vary partisan cues, we aim to provide evidence on whether Latin American affective polarization operates primarily through partisan channels or if leader-focused dynamics are more salient.

In the next section, we describe the treatments, which are factually accurate public statements by government officials, lightly edited for clarity. The Facebook-style posts were approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board (IRB) and included both widely supported policy stances (e.g., compulsory voting, unemployment benefits, anti-crime measures) and wedge issues that divided government and opposition supporters (e.g., protests, tax reform, inflation).

Survey Implementation, Treatments, and Estimation

To test our theory, we collected data from three nationally representative surveys conducted in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. The surveys implement a two-branch, two-stage design (see Figure 1). Respondents first answered socio-demographic questions, such as their gender, partisan affiliation, and age. Then, we randomly assigned one-third of the respondents to the control group (about 800 respondents) and two-thirds to the treatment group (about 1,600 respondents). Both groups answered the same questions, albeit in a different sequence. The control group answered questions about democratic institutions and was then presented with social media posts describing public officials’ statements. The treated group, on the other hand, was presented with the public statements first and then answered questions on democratic institutions.

Figure 1. Survey Flow.

In each country, we considered five different treatments, including non-partisan, partisan, and wedge issues. Attention and validation checks measured the behavioral response to the treatment—such as the willingness to “like,” “share,” and “comment” on social media posts—and the self-reported affective response, using Ekman’s six basic emotion categories (Ekman and Friesen Reference Ekman and Friesen.1971) (fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, and surprise). Multiple responses were permitted, except for “indifferent,” which was exclusive if selected. We describe the full set of experiments in the SIF file to this article.

Therefore, the only difference between the treatment and control groups is that the treated respondents observed the government messages before answering the democratic recession questions. In contrast, the control group observed the government messages only after they answered the democratic recession questions. We expect to distinguish whether voters’ willingness to transgress democratic institutions and support democracy results from the mechanisms proposed in our treatment.

Treatments

The treatments were all framed as Facebook posts. We included two alternative but semantically equivalent frames for each treatment: one as a confirmation (“It is TRUE that p”) and the second one as a refutation (“It is FALSE that not p”). Each survey featured five treatments tailored to address issues relevant to their respective countries. Treatments were selected based on whether the issue was likely to be contentious or broadly consensual in each country, with the goal of activating partisan identities and eliciting differentiated responses. Consensual issues were expected to produce similar reactions across respondents, while contentious issues were designed to generate partisan splits. Examples of these treatment sets are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sample of Brazilian, Chilean, and Colombian Treatments.

Note: A sample of nine treatments in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. All 15 treatments are described in greater detail in the Supplemental File to this article. Approximately 480 respondents were exposed to each treatment. We register exposure time, behavioral response (“like,” “share,” “comment”), and six self-reported affective responses.

The three cases were selected because they had competitive and polarized elections won by leftist presidents (Lula da Silva, Gabriel Boric, and Gustavo Petro) against conservative candidates (Jair Bolsonaro, José Antonio Kast, and Rodolfo Hernández) Footnote 2 in runoff elections. Further, in all three cases, the opposition candidates received more legislative votes and a larger share of seats in Congress. Therefore, all three countries have divided governments controlled by intense partisans.

The Brazilian survey was conducted from December 5 to December 15, 2022, with 2,426 respondents participating. A third of the respondents (801) were randomly assigned to the control group and the remaining two-thirds (1,625) to the treatment group. Three of the five treatments are shown in Figure 2, and the remaining two are in the appendix. The first treatment states that white people are significantly less affected by violence and represent only 16% of the victims (Crime16). The second treatment reports that black people are more affected by violence and represent 84.1% of all victims (Crime84). The third treatment indicates that over 90% of Brazilians have altered their consumption habits due to inflation (Inflacion90). The fourth treatment states that under 10% of Brazilians have kept their consumption habits unchanged amid inflation (Inflacion10). The fifth treatment states that the current Brazilian tax system favors the wealthy and that Lula seeks to introduce a new tax on dividends (LulaTax).

The Chilean survey was conducted from October 19 to November 7, 2022, with 2,772 respondents. We assigned 961 respondents to the control group. The remaining 1,811 were assigned to the treatment group. Figure 2 displays three of the five treatments in the Chilean study. The first treatment reports the commitment by the current administration of Boric to maintaining compulsory voting, a policy favored by a majority of voters in Chile (Voto Obligatorio). The second treatment reports on the Chilean government’s commitment to reducing expenditure and inflation (Inflacion). The third treatment states that the administration supports existing pro-abortion reforms (Aborto). The fourth treatment reports that the administration will not violently suppress social protests, primed with an image of the Minister of the Interior giving a speech (ProtestaMinistra). Finally, the fifth treatment is identical to treatment number four, committed not to suppress protests but is primed with a picture of protesters banging pots and pans (ProtestaMarcha).

The Colombian survey was conducted from February 2 to 27, 2023, involving 2,449 respondents. We assigned 859 respondents to the control group and 1,590 to the treatment group. Figure 2 displays three of the five treatments in the Colombia study. The first two treatments state that the proposed tax reform will not levy taxes on pensions or modify duties on oil and carbon (Impuesto). The second treatment reports that unemployment is largest among Afro-descendent women, 20%, compared with other Colombian women, 14%, and Colombian men, 8.9% (Desempleo). The third treatment reports that inflation affects higher-income individuals less (InflaciónMas). The fourth treatment reports that inflation affects lower-income individuals more (InflaciónMenos). Lastly, the fifth treatment reports that Vice-President Francia Márquez publicly denounced that she was the target of a terrorist attack (AtentadoMárquez).

All treatment messages were drawn from real, contemporaneous news coverage of government actions and politically salient events during our fieldwork period. The selected frames were chosen because they were significant at the time and collectively represent a range of expected partisan intensity. This range goes from more polarizing content, such as protest repression and clashes with Congress, to routine policy reporting, like inflation and unemployment figures. We did not insert explicit partisan labels or elite cues (e.g., party or leader names) to maintain realism and assess whether news about government performance activates partisanship even in the absence of overt partisan signals. This design captures how voters interpret ordinary political information in high-stakes contexts, but it also introduces treatment heterogeneity that can dampen pooled average effects.

Variables

We estimate models for two main dependent variables. The first measure is the respondents’ willingness to transgress democratic institutions to favor Congress instead od the president. The variable is measured based on a 5-point agreement scale with the question: “If the president’s policy does not match the preferences of [Chileans, Brazilians, Colombians], Congress should remove the president from office.” The 5-point scale ranges from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Our second dependent variable measures respondents’ willingness to dissolve Congress using the same 5-point agreement scale: “When the country faces serious difficulties, it is justifiable for the President to dissolve Congress.”

Note: In the above equation, Y i is either (i) agreement that Congress should remove the president or (ii) agreement that dissolving Congress is justifiable (5-point scales). We estimate OLS and Ordered Probit versions. Oppi and Blank i are vote dummies for the opposition and blank vote, holding incumbent as the omitted category. T i ∈ {0, 1} is the treatment indicator. X i includes models with and without socio-demographic controls. Given that the experiment is fully randomized, the main document presents models without controls. Results do not change if we add socio-demographic controls, although differences among groups in mean support for impeachment and/or dissolving Congress are substantively interesting.

We measure respondents’ undemocratic attitudes as a function of vote choice and exposure to social media treatments. Vote choice measures the preferred presidential candidate “if the presidential election runoff was set to take place next week.” Footnote 3 The three alternatives were to vote for the incumbent president, to vote for the leading opposition candidate of the last runoff election, or to cast a blank vote. We replicated the ballot format from the previous election. In all models, we set the base category to the incumbent president and create dummy variables for the opposition and blank vote choice. The treatment variable is coded as 0 for control group respondents and 1 for those in the treated group. The comprehensive models incorporate the two primary independent variables—vote choice and treatment interaction—along with other socio-demographic controls. Finally, we created dummy variables for the five distinct political messages to measure the effectiveness of widely accepted and more partisan messages.

Results

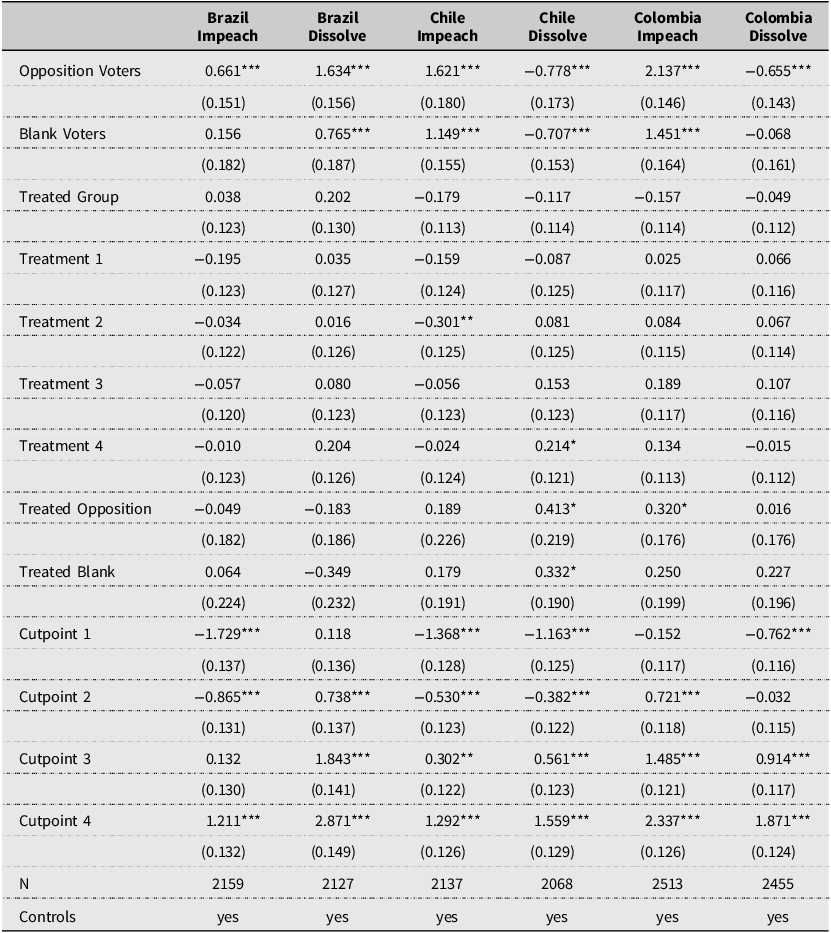

We estimate both OLS and ordered logit specifications of our models, given the 5-point scale of our dependent variables. Figure 3 and Table 1 present the OLS and ordered logit results, respectively. In our model specifications, which include controls, the left-leaning incumbent president serves as the baseline in each country. Models include a variable for the treated group and separate dummies for each treatment category. To facilitate the interpretation of our results, Figure 3 presents the OLS predicted probabilities, organized by country—Brazil, Chile, and Colombia—and by candidate type, from left to right: left-leaning, blank voters, and right-leaning.

Table 1. Support for Impeachment and Dissolution of Congress in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia

*** p<.01; **p<.05; *p<.1

Notes: The model baseline is set to voters for the incumbent presidents in each country, Lula Da Silva (president-elect) in Brazil, Gustavo Petro in Colombia, and Gabriel Boric in Chile. The baseline treatments are Crime16 in Brazil, votoObligatorio in Chile, and Impuesto in Colombia. The baseline treatment is Inflacion10 in Brazil, Aborto in Chile, and AtentadoMarquez in Colombia. Treatment 2 is Inflacion90 in Brazil, Inflacion in Chile, and Inflacion in Colombia. Treatment 3 is Crime84 in Brazil, ProtestaMinistra in Chile, and Inflacion+ in Colombia. Treatment 4 is LulaTax in Brazil, ProtestaMarcha in Chile, and Desempleo in Colombia. Cut points of the ordered logit can be used to retrieve the probability that respondents will select a rank ordered category.

Figure 3. Impeachment and Dissolution of Congress by Party and Country, Treatment and Control, OLS Models Reported in the SIF to this Article.

Let us begin by describing the overall model results shown in Figure 3. The first set of hypotheses predicts that opposition voters will show higher support for impeaching the president, while government voters will be more inclined to support dissolving Congress. As expected, opposition voters reported support for impeachment between half a point (Brazil) and two points higher (Chile). Differences were statistically significant at the p<.01 level in all three countries.

There are also significant differences in the support for impeachment across countries. In Brazil, the mean support for impeachment is very high across the board, including among supporters of the Workers’ Party president Lula da Silva. This is not surprising given the high frequency of impeachment proceedings and the removal of Collor de Mello and, more recently, Dilma Rousseff. While the decision to remove Collor de Mello took place amid a corruption scandal, Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment is widely considered partisan and politically motivated (Nunes and Melo Reference Nunes and Melo.2017; Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk2017). Interestingly, while progressive and leftist Members of Congress (MCs) proposed bills (2019) and initiated impeachment procedures (2022) against Sebastian Pinera, support for impeachment among supporters of Gabriel Boric in Chile is well below the support for impeachment among Lula da Silva voters. Our results also show that Chile has the widest differences in support for impeachment between government supporters and opposition.

Finally, Colombia, a country that has not sought to impeach a president since the proceedings against Ernesto Samper in 1996 and has never successfully impeached a president (Buitrago Rojas et al. Reference Buitrago Rojas, Miranda Corzo and López López.2020), displays remarkably high levels of support for impeaching the President.

Opposition voters reported lower support for dissolving Congress in Colombia and Chile, as expected. However, and to some extent surprisingly, Bolsonaro’s voters supported dissolving Congress, reporting a 3.27/5 score on the “agree” side of the scale. Differences between the left and the right were large and statistically significant at the p<.01 level in all three countries, but, as indicated, of the opposite sign in Brazil. The fact that Lula da Silva was president-elect and that Bolsonaristas expressed significant anger regarding the result of the 2022 election may partly explain these results. However, the Liberal Party of Jair Bolsonaro has the largest delegation to the Brazilian Congress (99 seats), and the Conservatives hold 233 seats compared to 223 of the governing coalition. Therefore, on purely instrumental grounds, it is unexpected that Bolsonaro voters displayed the highest support for dissolving Congress.

In all three countries, the overall support for dissolving Congress was lower than the support for impeachment. It is only among the supporters of Gabriel Boric in Chile that support for impeachment was below the support expressed for dissolving Congress. Despite the unexpectedly high support for dissolving Congress among Bolsonaro’s supporters, the evidence generally supports hypotheses 1a and 1b.

Still, baseline levels of support for democratic breakdown are striking. According to the 2021 Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) Pulse of Democracy, 25% of Brazilians, 20% of Chileans, and 34% of Colombians believe it is justifiable for a president to close Congress during difficult times. Moreover, 38% of Brazilians would justify a military coup if corruption were high (Lupu et al. Reference Lupu, Rodríguez and Zechmeister2021). These figures mirror our findings and suggest a broader regional pattern in which democratic erosion is increasingly normalized—not just among ideological opponents or partisan groups, but across the political spectrum.

Treatment-Specific Effects

The results do not support hypotheses 2a and 2b, as outlined in the previous sections and our pre-registered plans. First, results in Figure 3 show minimal differences between the mean support for impeachment among those respondents treated to social media posts by the government and those in the control group. Among the nine comparisons between the treated and control groups in Figure 3, only one estimate behaves as expected according to our experimental design (i.e., the decline in the preference for impeachment among Gabriel Boric supporters). By contrast, results are not statistically significant for all other groups of voters in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia.

Similarly, the treatments had an insignificant effect on preferences for dissolving Congress.

The results are null, and the relatively tight confidence intervals for the treated and control groups indicate that this is not a measurement problem. Further tests of the mechanisms in the last section of this article indicate that the respondents properly understood the treatments. Validation and attention checks confirm that the lack of effect is not due to a failure to elicit the intended treatment response.

A more detailed look at the treatment-specific effects is shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6, which plot the predicted probabilities by treatment type against the control group for all three countries. Although we reported the treatments’ null effects, some political messages seem to affect support for undemocratic practices. In Brazil, blank voters exposed to the treatment Crime16 were less likely to back the dissolution of Congress, as reported in the bottom middle graph in Figure 4. In Chile, blank voters exposed to the abortion treatment were more likely to report a preference for impeachment, as we can see from the top middle graph in Figure 5. In Colombia, exposure to the treatment of inflation decreased incumbent voters’ willingness to constrain the authority of Congress, as shown in the bottom left graph in Figure 6. Additionally, opposition voters exposed to the tax reform treatment were more likely to favor the dissolution of Congress, as shown in the bottom right graph in Figure 6.

Figure 4. Impeachment and Dissolution of Congress by Party and Treatment in Brazil, OLS Models Reported in the SIF to this Article.

Figure 5. Impeachment and Dissolution of Congress by Party and Treatment in Chile, OLS Models Reported in the SIF to this Article.

Figure 6. Impeachment and Dissolution of Congress by Party and Treatment in Colombia, OLS Models Reported in the SIF to this Article.

Although some results suggest that priming with wedge and partisan issues might increase support for impeachment, as seen with Kast’s supporters reading the protest post in Chile, these findings generally lead to rejecting the second set of hypotheses. While it is possible that negative and highly toxic messages will produce the desired effect, that would only be possible if we sacrifice external validity. We consider our choice of treatments as carefully curated to describe typical messages observed in all three countries and, within those parameters, the results should be considered globally as null and a rejection of the stated hypotheses.

Why “Null Findings”? An Autopsy of Our Experiment

Results in this article describe affectively polarized voters who support undemocratic policies when doing so advances in-group goals. However, our experimental design does not show that brief partisan messages increase support for undemocratic practices. Across most treatments, outcomes for treated respondents are statistically indistinguishable from those in the control group; only a few highly partisan messages on wedge issues yield suggestive patterns. In this section, we conduct an autopsy of these results to assess whether the nulls are credible signals of respondents’ underlying attitudes or artifacts of design, measurement, or power.

Our sample size is large and comfortably exceeds power requirements, including for partisan and blank-vote subsamples. Footnote 4 Anticipating null results, we built multiple validation checks into the instrument: we verify that respondents understood the treatments, that the messages elicited the expected affective responses, and—conditioning on those responses—test the hypothesized mechanisms linking exposure to partisan content with (un)democratic attitudes.

It is worth noting the broader value of reporting well-powered null results in political persuasion research. Recent changes to pre-register experiments and a new impetus to publish null findings emerged from the need to reduce positive-finding (publication) bias, which can overstate causal effects. However, we consider that it is critical not only to minimize positive-finding bias but also test if such null findings are truly testing our theory of interest. By documenting theoretically motivated and empirically supported nulls, published research should not only counter the file-drawer problem, where null findings are not published, but also provide a more accurate account of the sources of different types of nulls. In our case, it is important to describe both how often partisan messages fail to move attitudes but also the likely reason for minimal effects, thereby strengthening cumulative knowledge about the reach and limits of partisan cues.

Therefore, in this article we explicitly test why results are null rather than treating them as uninterpreted failures. We probe treatment strength, baseline ceilings, and emotional activation, and show that although respondents engaged with partisan-consistent messages, these cues did not translate into greater support for institutional transgressions. This pattern aligns with prior work: Kalla and Broockman (Reference Kalla and Broockman.2018) show that campaign persuasion effects are typically small and short-lived, and Guess and Coppock (Reference Guess and Coppock.2020) find limited influence of online political adverts on voter attitudes and behavior. Our diagnostic approach demonstrates that when the experiment elicited the expected affective responses, there were minimal and inconsistent changes on institutional attitudes, turning an absence of average treatment effects into an informative contribution about the boundary conditions of partisan persuasion.

What Could Have Failed … or Not?

Null findings are significant when they disprove theories, but less so if they result from poor design choices (Calvo and Ventura Reference Calvo and Ventura.2021). Therefore, let us describe three distinct problems that could affect our experiment. First, (1) respondents could have failed to interpret the social media treatments. In that case, the null findings would not disprove the hypotheses, given that partisanship was not properly primed. To ensure that treatments were understood correctly, we asked respondents whether they would “like,” “share,”“comment,” or ignore the Facebook posts. Therefore, we can assess if partisans’ interpretation of the treatment aligns with our experimental design.

Second, findings may be weak because frames did not produce the expected emotional response, with negative or positive partisan messages failing to elicit in-group or out-group affective reactions. Following Banks et al. (Reference Banks, Calvo, Karol and Telhami, S.2021), we expect self-reported affective responses such as“anger,”“joy,” or “disgust” to activate partisan identities and increase the perceptions of threat to the in-group. However, if the affective responses do not correspond with the expectations, then the (un)democratic response would not materialize.

Finally, it is possible that the treatment frames are appropriately interpreted by the respondents and that they elicit the expected affective responses. In this case, we assume that the null results are an appropriate description that the mechanism is not producing the expected results. The hypotheses would then be rejected.

In summary, if the treatments fail to elicit the expected partisan response, it would indicate a problem with the experimental design. In contrast, eliciting the proper behavioral and affective response would suggest that the hypotheses are not supported. Footnote 5

Autopsy of Problem 1: Did the Respondents Properly Interpret the Treatments?

To evaluate if there is a failure to communicate the partisan content of the frames, we can take advantage of one of the survey questions that asked respondents whether they would “like,” “share,” “comment,” or “ignore” the treatments. Descriptive information in Figure 7 shows that, as expected, decisions to “like” follow clear partisan lines, with voters supporting the government considerably more likely to “share” the treatments than supporters of the opposition.

Figure 7. Respondents’ “Like” Rate by Country, Party, and Treatment.

Interestingly, some of the results we previously described as suggestive also elicit a wider inter-party difference in “likes,” such as the treatments “marcha protesta” and “aborto” in Chile. However, while supporters of the government “liked” and “shared” the different treatments, it did not translate into more (un)democratic attitudes.

Overall, the “like” and“share” behavior indicates that respondents correctly interpreted

the treatments. Results rule out that the source of the null findings is an improper design or a failure to understand the treatments. Footnote 6

Autopsy of Problem 2: Did Treatments Elicit the Expected Affective Response?

Results in Figure 8 show that self-reported anger is higher among partisans and for partisan treatments. In Brazil, 23% of Lula voters reported “anger” after being exposed to the Crime16 and Crime84 posts, while 29% of Bolsonaro supporters reported “anger” after reading LulaTax. However, neither Lula nor Bolsonaro voters increased their support for dissolving Congress or impeachment. There is no increase in (un)democratic attitudes when considering those treatments that elicit the strongest negative responses. The effect of the treatments is null when we add the emotional responses as controls for the models.

Figure 8. Respondents’ Self-reported “Anger” by Country, Party, and Treatment.

In the case of Chile, the abortion and two protest treatments elicited angry responses of 24%, 47%, and 49% among Kast voters, respectively. Although ProtestaMarcha and ProtestaMinistra have almost identical “angry” rates, only ProtestaMarcha is associated with a statistically significant agreement with impeachment at p<.05, while the effect of the abortion treatment is insignificant, and the direction of the effect is contrary to expectations.

In Colombia, the three treatments that elicited the highest “angry” rates were unemployment and the two inflation treatments. Although the rate was well above 30% of the sample, there was no statistical difference compared to the control group.

Overall, there is no evidence that high self-reported rates of anger following exposure to the treatments had any measurable effect on support for impeachment or for dissolving Congress. Nonetheless, the autopsy indicates that respondents properly understood the treatments and exhibited the expected behavioral and emotional responses, which helps explain the null nature of our findings. It also rules out the concern that the treatments were too familiar to respondents, since they still behaved as anticipated.

Discussion and Limitations

This multi-country, pre-registered study aimed to test for the impact of partisan social media messages on two undemocratic practices: the politically motivated impeachment of the president and the illegal dissolution of Congress. Our survey recruited 7,500 respondents in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia, covering 15 treatments that ranged from non-partisan government statements to contentious issues such as protests, taxes, and abortion. The two-branch and two-stage design included validation checks to evaluate the behavioral and affective reactions to the treatments, allowing us to verify that respondents understood the messages and that partisans’ “likes” and their affective responses met the design expectations.

The results of this study confirm that opposition voters express higher support for impeaching the president, and government voters express higher support for dissolving Congress. As expected, opposition voters reported support for impeachment between half a point (Brazil) and two points higher (Chile) on a 5-point scale. Differences were statistically significant at the p<.01 level in all three countries.

While partisan differences in attitudes towards impeachment and dissolving Congress align with expectations, the results of the different treatments did not consistently increase or decrease undemocratic attitudes. The narrow confidence intervals around the treatment and control groups indicate that attitude differences across partisans are robust and that the treatments had no measurable effects.

Results in Figure 7 and Figure 8 provide consistent evidence that supporters of the different candidates “liked” the treatments as per the design and that these treatments activated the expected emotional responses. However, liking the treatments and angry self-reported emotions do not increase support for impeachment or dissolving Congress. We consider our findings as “evidence of absence,” an investigate possible sources of the null finding to rule out that our results merely reflect the “absence of evidence.” In doing so, we add to a growing body of research showing minimal effects for social media posts on democratic recession (Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman.2018; Guess and Coppock Reference Guess and Coppock.2020).

Our diagnostic evidence suggests that partisan activation is most visible for frames that are simultaneously contentious and cue partisanship clearly, whereas more consensual or weak-cue frames elicit smaller alignment differences. This helps explain why our average attitudinal effects on institutional transgression are null despite observable engagement skews: with a valid mix of topics, strongly polarizing messages are pooled with broadly non-divisive ones, likely diluting average impacts. Therefore, we expect larger attitudinal effects in settings saturated with explicit partisan signals and high-salience conflicts (e.g., elite accusations, leader-named appeals or election proxy messaging), and smaller effects for factual or widely supported policy frames; our study’s topic mix and news-style presentation bring it closer to the latter.

Despite these null findings, our results highlight worrisome levels of support for undemocratic attitudes in the region. Data from the LAPOP show that a substantial share of citizens in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia consider it justifiable for a president to close Congress or, in extreme cases, for a military coup (Lupu and Zechmeister Reference Lupu and Zechmeister.2021). Data from reports produced by National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago indicate that the cluster of authoritarian-leaning citizens in Brazil has grown over the past decade, while in Colombia, support for executive aggrandizement is rising (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Fuks and Ribeiro.2023a,b). Although comparable longitudinal data for Chile are unavailable, these patterns suggest that democratic attitudes in the region may be deteriorating, underscoring the urgency of understanding and addressing these trends.

The study presents valuable insights into partisan attitudes towards impeachment and dissolving Congress, yet it also reveals limitations. One notable shortcoming is the possibility that the interventions failed to elicit genuine responses from participants. This could be attributed to various factors, such as respondents discerning the artificial nature of the interventions, leading to insincere or biased responses. Additionally, utilizing Facebook as the intervention platform may have influenced how participants engaged with the content, potentially affecting their responses. Moreover, the choice of treatment issues may not have been perceived as sufficiently contentious or “wedgy” by participants, which could have influenced their reactions. Future research should address these limitations by employing more immersive and realistic interventions that better simulate real-world scenarios, using diverse platforms beyond social media, and selecting issues that resonate more deeply with participants’ political beliefs and concerns. By addressing these limitations, future studies can enhance the validity and generalizability of findings related to partisan attitudes and democratic processes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2026.10045.

Data availability statement

Data for this study can be accessed via the following URL: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/K9DHYI.

Completing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Use of AI

ChatGPT-5 was used to assist with R code troubleshooting and document proofreading. No large language model (LLM) was used to generate the substantive content of this article.