Introduction

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous organisms occurring in drinking water and public water supply systems, which are often sources of contamination. Reference Phillips and von Reyn1 Of late, reports of NTM clusters in the nosocomial setting, especially hospitals in high-income countries, have been on the rise. Reference Baker, Nick and Jia2,Reference Klompas, Akusobi and Boyer3 NTM-related disease commonly present with pneumonia, a bloodstream infection or a skin infection. Reference Charles, Jonathan, Christoph, Emmanuelle, Richard and Claire4,Reference Griffith, Aksamit and Brown-Elliott5 While NTM-related disease is nosocomially transmitted, the difficulty of identifying the origin of outbreaks and the need for extensive environmental sample culturing and outbreak investigations frequently hamper their care and the management of infection clusters. Hospital water supply systems, heater-cooler devices, and climate control systems are known to be potential sources of nosocomial NTM outbreaks. Reference Phillips and von Reyn1,Reference Takajo, Iwao and Aratake6–Reference BaoYing, XiaoJun, HaiQun, Fan and LiuBo8 Moreover, patients with an active NTM-related disease originating within a hospital might have immunocompromised status or an underlying lung disease, which makes the choice of an appropriate antimicrobial agent challenging especially if the information needed to choose a combination regimen is unavailable because the pathogen’s antimicrobial susceptibility is unknown. Reference Loebinger, Quint and van der Laan9

We herein report a cluster of infections caused by Mycobacterium lentiflavum, a rare species of NTM, which was isolated from the sputum culture of inpatients at a Japanese tertiary care center. M. lentiflavum, a slow-growing pathogen first identified in 1996, is now widely recognized thanks to improvements in diagnostic methods. Reference Sood and Perl10,Reference Springer, Wu and Bodmer11 An outbreak investigation was undertaken at the study center to identify patients with M. lentiflavum colonization or infection and to locate the source of the pathogen. The present study also discusses infection prevention measures that were implemented to contain, then eradicate, the M. lentiflavum cluster.

Methods

Setting and microbiology laboratory

The present study investigated a cluster of infections by M. lentiflavum, which was isolated from sputum samples of inpatients at Tachikawa Sogo Hospital, a 287-bed acute care hospital with 32 subspecialties, located in Japan. The municipal water supply system supplies water to the hospital, which is stored in the hospital’s water tank for chlorination before distribution. The study center has eight hospital wards, including an intensive care unit (ICU) and an obstetrics/gynecology ward. As the hospital’s microbiological laboratory does not perform acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cultures or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium species (spp.), these tests were outsourced for further identification to a laboratory which performed PCR testing for M. tuberculosis and M. avium complex once a culture was found to have grown mycobacteria. Until March 2024, if PCR testing of a culture sample failed to identify M. tuberculosis or M. avium complex, the result was reported only as positivity for Mycobacterium spp. However, in April 2024, the laboratory introduced Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption / Ionization Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF: MALDI Bioptyper Bruker corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), which has enabled accurate identification of NTM species. Reference Toney, Zhu and Jensen12 The institutional review board at Tachikawa Sogo Hospital approved the present study (#24-006).

Definition of colonization and infection

One of the authors (S.O.) reviewed the electronic health records of patients with respiratory samples that were positive for M. lentiflavum to determine whether the patients had symptoms and radiographic findings indicating an NTM-related pulmonary disease. The present study used the microbiological, diagnostic criteria of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) / Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), which stipulate positivity for the same NTM species in a culture of at least two samples of expectorated sputum or at least one bronchial wash or lavage culture, or a transbronchial or other type of lung biopsy demonstrating mycobacterial, histopathological features. Reference Griffith, Aksamit and Brown-Elliott5 Patients fulfilling all the clinical, radiographical, and microbiological criteria received the diagnosis of an NTM-related pulmonary disease while those who did not fulfill the criteria were considered to have NTM colonization.

Additional microbiological analysis

After the M. lentiflavum cluster was identified at the study center, additional, microbiological analysis was performed at the Center for Infectious Disease Research at Fujita Health University. Unless otherwise noted, the M. lentiflavum isolates were grown aerobically at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (BD DifcoTM) supplemented with oleate-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC; 10 %, vol/vol), glycerol (0.2 %, vol/vol), and tyloxapol (0.05 %, vol/vol). Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described. Reference Osugi, Tamaru, Yoshiyama, Iwamoto, Mitarai and Murase13 To assess intraspecies variability, the following genetic markers were used: 16S rRNA, Reference Kirschner, Springer and Vogel14,Reference Edwards, Rogall, Blocker, Emde and Bottger15 RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB), Reference Kim, Lee and Lyu16 heat shock protein 65 (hsp65), Reference Telenti, Marchesi, Balz, Bally, Bottger and Bodmer17 and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Reference Richter, Niemann, Rusch-Gerdes and Hoffner18 PCR amplification was performed using the primer sets shown in Supplementary Table 1 with GoTaq Green Master Mix under the following conditions: 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 7 min. Amplicons were sequenced using ABI 3,500 for multi-locus sequencing typing (MLST). DNA sequences were aligned using MEGA 11 and Unipro UGENE v50.0. Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar19,Reference Okonechnikov, Golosova, Fursov and Team20

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 12 antimicrobial agents (streptomycin [SM], amikacin [AMK], kanamycin [KM], isoniazid [INH], rifampicin [RFP], levofloxacin [LVFX], clarithromycin [CAM], ethambutol [EB], and linezolid [LZD]) for the M. lentiflavum isolates were determined in the following manner. Each isolate was grown in 7H9 medium with OADC, glycerol, and tyloxapol to mid-log phase and then diluted in 200 µl of the same medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01 in each well of multiple, non-treated, flat-bottom 96-well plates. A twofold dilution series of each antimicrobial was prepared by dispensing the antimicrobial agents into each well using a digital dispenser (Multidrop pico8 digital dispenser; Thermo Fisher). After incubation at 37°C for 21 days, the plates were briefly mixed using a microplate shaker, and the OD600 was measured using BioTek Synergy HTX. The MIC of the drugs against each isolate was defined as the lowest concentration at which 90% inhibition based on the OD values compared to controls. The tests were repeated two times with two technical replicates.

Results

In February 2024, a hospital infection control nurse received a report that M. lentiflavum had been isolated from a sputum culture of four inpatients. The first patient was a 71-year-old, Japanese male with peptic ulcer diseases who had community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). A sputum culture for bacteria and AFB was ordered to determine the etiology of the CAP. His condition improved with ampicillin and sulbactam, and he was discharged after seven days. Sixty-three days later (in April 2024), the AFB culture was found to have grown M. lentiflavum. Sputum AFB cultures from the remaining, three patients during the same period also grew M. lentiflavum. Although some of the patients were symptomatic at the time of the sputum collection, the ATS / IDSA diagnostic criteria indicated that all four patients were colonized by M. lentiflavum.

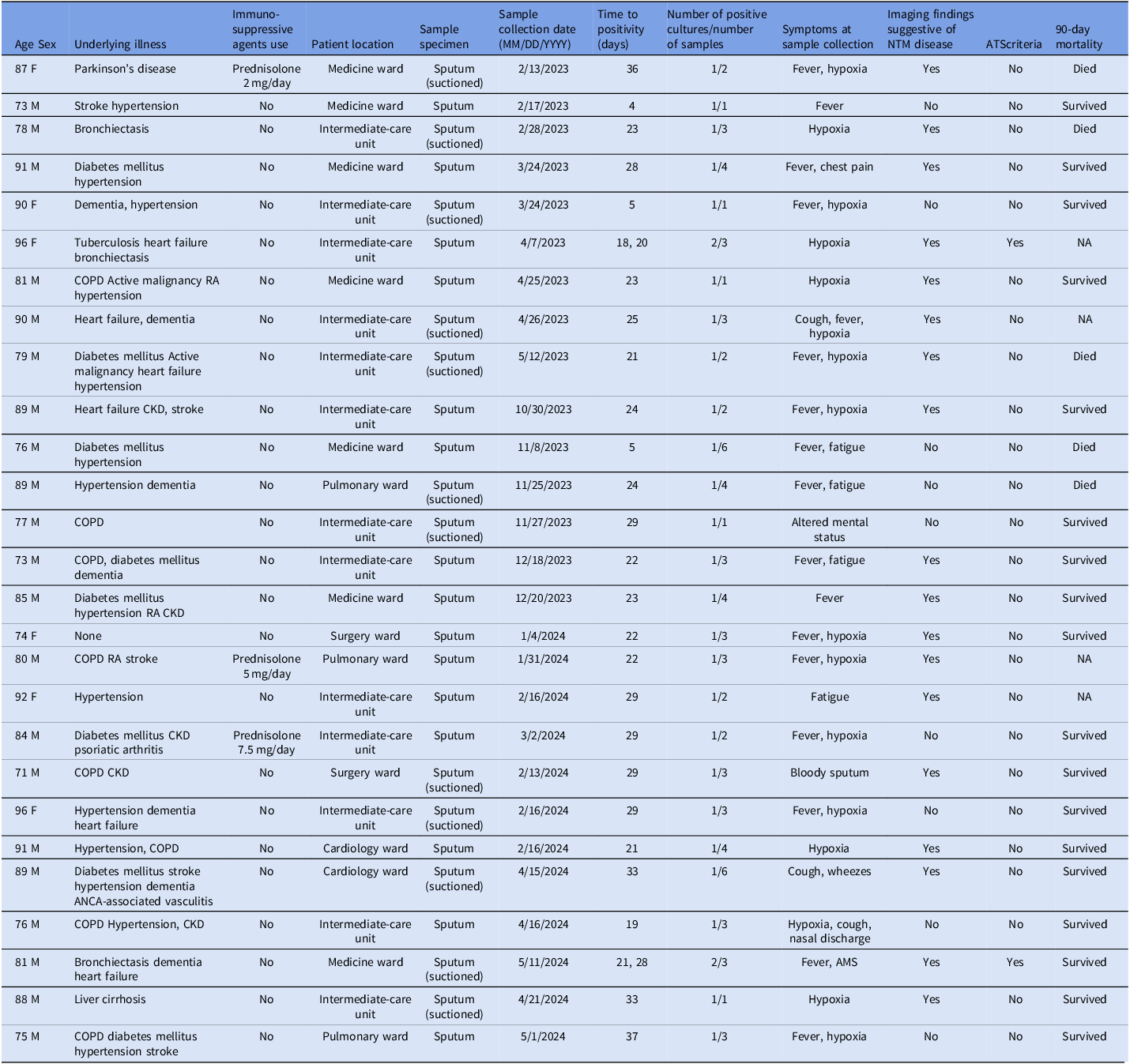

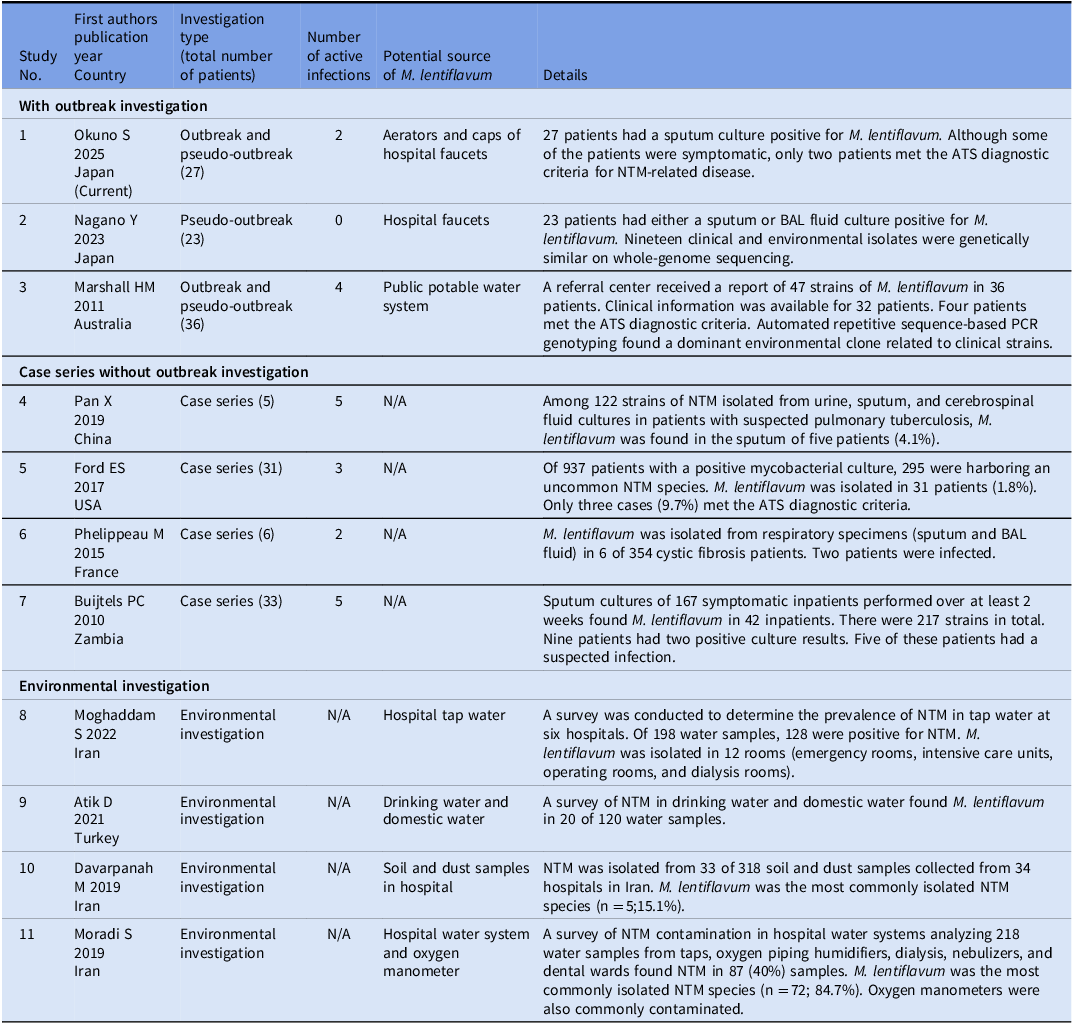

From February 2023 through April 2024, the department of infection prevention and control at the study center retrospectively investigated inpatients whose respiratory culture had revealed an unidentified species of NTM. As noted above, before April 2024 when MALDI-TOF was still unavailable at the hospital’s laboratory, any NTM species other than M. avium complex was reported only as Mycobacterium spp. For the present study, the laboratory re-cultured and analyzed the previous samples using MALDI-TOF to identify the pathogens definitively. As a result of this retrospective investigation, 27 patients with M. lentiflavum between February 2023 and the end of May 2024 were identified. Table 1 and Figure 1 show the demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients and the epidemiology curve, respectively. The median age was 84 years, and male patients comprised 78% of the cohort (21/27). Most of the patients (25/27; 93%) were considered to have been colonized by M. lentiflavum, and a large proportion of these had an underlying illness, such as diabetes mellitus or a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Although two patients met the ATS / IDSA criteria for the diagnosis of NTM-related pulmonary diseases, neither received antimicrobial therapy for their condition. Of the two patients, one survived beyond 90 days after the positive sputum collection date, while the other was discharged but could not be confirmed for 90-day mortality due to loss to follow-up. Table 2 shows past reports of clusters of M. lentiflavum infection and colonization, and environmental investigations. Reference Nagano, Kuronuma and Kitamura21–Reference Moradi, Nasiri, Pourahmad and Darban-Sarokhalil30 Only two hospital outbreak investigations have been published, the remaining articles describing M. lentiflavum being either case series or an outbreak or environmental investigation.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the patients with a culture positive for Mycobacterium lentiflavum (N = 27)

M, male; F, female; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; AMS, altered mental status.

Figure 1. Epidemiology curve for the cluster of mycobacterium lentiflavum infection and colonization at the study hospital.

Table 2. Previous studies of mycobacterium lentiflavum-related pulmonary infection and colonization clusters and environmental investigations

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; ATS, American Thoracic Society.

Environmental investigation

In total, 113 environmental water samples (200 ml each) were collected in a sterile 0.2 L container from six hospital wards or units, a nutritional department office, and hospital water tank. Various water sources, including the room faucets in four-bed rooms (n = 34) and private rooms (n = 35) and faucets in nursing stations and staff break rooms (n = 44) were examined. In addition, culture samples were obtained from air-conditioner vents. Extensive, environmental culturing subsequently identified M. lentiflavum in the water from ten faucets in the patient rooms in four wards or units. None of the samples from the water tank or the faucets in the nurses’ station or break rooms grew the pathogen.

Microbiological investigation

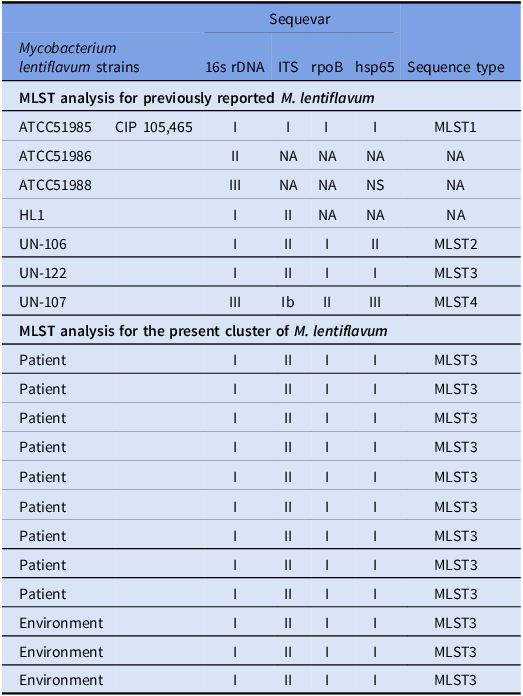

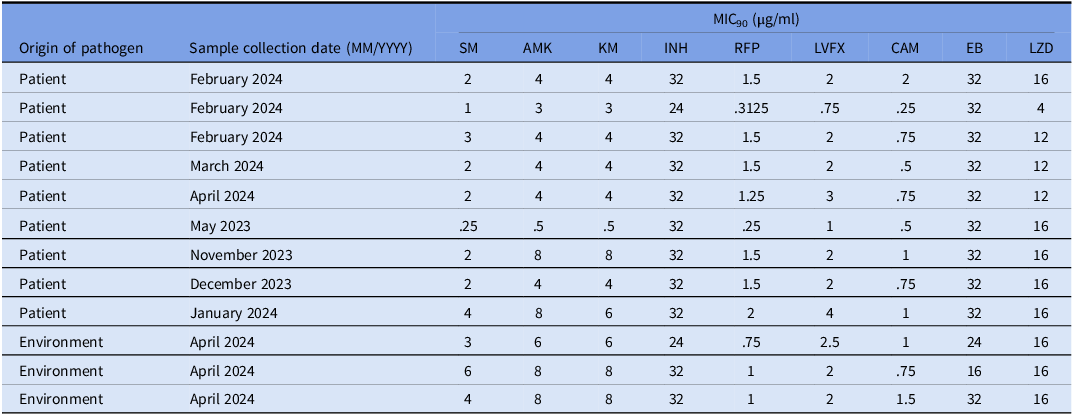

Twelve of the 27 isolates of M. lentiflavum (five isolates derived from patients during the current cluster [sampling clinical sputum specimens was performed from February 2024 to March 2024], four derived from patients during the previous, hypothetical cluster [sampling clinical sputum specimens was performed from February 2023 to January 2024], and three derived from environmental cultures in April 2024) were subjected to multi-locus sequence typing (MLST). The targeted genes in the twelve samples had no allelic variants and came from the identical strain. A comparison of each of the targeted fragment sequences with registry data found that the 16S rDNA and hsp65 genes were identical with those of M. lentiflavum ATCC51985. Furthermore, the 16S-23S rRNA gene’s ITS sequence and the rpoB gene matched perfectly with the sequence of M. lentiflavum KKC-1, which was isolated in Japan (Table 3). Iwamoto et al previously categorized the results of four-locus MLST of M. lentiflavum into four groups. Reference Iwamoto, Nakanaga, Ishii, Yoshida and Saito31 Table 3 shows the MLST profile shared by each of the nucleotide polymorphisms. The 12 clinical isolates in the present study were designated MLST 3. Table 4 shows the susceptibility of M. lentiflavum to twelve antimicrobials. While the MIC 90 of the antimicrobials varied, the MIC 90 for clarithromycin and levofloxacin were consistently lower than that for the other antimicrobials.

Table 3. Multi-locus sequence typing analysis for the classification of twelve isolates of mycobacterium lentiflavum with a comparison to previously reported M. lentiflavum

Note: The isolates are indicated as follows: light gray: isolates from patients in the current cluster; medium gray: isolates from patients in the previous, hypothetical cluster; dark gray: isolates from environmental samples in the present cluster.

Table 4. Antimicrobial susceptibility of mycobacterium lentiflavum isolated from patients and environment

MIC90, 90% minimal inhibitory concentration; SM, streptomycin; AMK, amikacin; KM, kanamycin; INH, isoniazid; RFP, rifampicin; LVFX, levofloxacin; CAM, clarithromycin; EB, ethambutol; LZD, linezolid.

The isolates are indicated as follows: light gray: isolates from patients in the current cluster; medium gray: isolates from patients in the previous, hypothetical cluster; dark gray: isolates from environmental samples in the present cluster.

Intervention

Because most of the positive culture results were of water samples from the faucets, the contamination was thought to extend to the equipment connected to the faucets, such as aerators and caps. In May 2024, the aerators and caps of all the hospital facets were manually cleansed, then disinfected using liquid sodium hypochlorite. Although the cultures of the water from the holding tank did not grow M. lentiflavum, the hospital management chlorinated the water again in June 2024 after the current cluster was detected. We obtained surveillance cultures from infected aerators 1 month and 3 months after identifying the cluster. No new M. lentiflavum infections or colonies have been detected in either clinical or surveillance cultures since September 2024.

Discussion

The present study examined a hospitalwide cluster of M. lentiflavum infections and colonizations at a tertiary care hospital in Japan. As Table 2 shows, only a few outbreaks or pseudo-outbreaks of M. lentiflavum were previously reported. Reference Nagano, Kuronuma and Kitamura21,Reference Marshall, Carter and Torbey22 Although most of the patients in the present study did not meet the diagnostic criteria of the ATS for NTM-related pulmonary diseases, an NTM-related pulmonary disease was suspected in two patients, suggesting that the nosocomial outbreak and an environment-oriented pseudo-outbreak had occurred concurrently. Moreover, the isolation of M. lentiflavum from cultures of water from the faucet aerators in the patient rooms indicated that the aerators were likely to be the source of the other instances of water contamination. The findings of the present, retrospective outbreak investigation using MLST typing suggested that the cluster had been present in the study center for about 16 months. Our outbreak investigation fortunately identified the source of the pathogen and led to the implementation of hospitalwide, infection control measures, which prevented further transmissions.

NTM, including M. lentiflavum, are widely distributed in the environment, including soil and dust. Reference Davarpanah, Azadi and Shojaei29 Previous, epidemiological studies of the healthcare setting found M. lentiflavum in hospital tap water, hemodialysis fluid, and oxygen manometers. Reference Moghaddam, Nojoomi and Moghaddam27,Reference Moradi, Nasiri, Pourahmad and Darban-Sarokhalil30,Reference Ghafari, Alavi and Khaghani32,Reference Scorzolini, Mengoni and Mastroianni33 As with NTM in general, M. lentiflavum has the potential to cause pulmonary disease. Nonetheless, as Table 2 shows very few studies have investigated M. lentiflavum outbreaks and pseudo-outbreaks.

In the present cluster, environmental cultures indicated that only the aerators and rectifiers were contaminated. However, contamination of the plumbing system could not be confirmed, as no biofilm samples were collected or cultured. In a previous study, biofilm accumulation in plumbing structures may contribute to persistent colonization of water supply systems. Reference Anaissie, Penzak and Dignani34 Poor plumbing design, aging and deteriorating plumbing infrastructure, and water stagnation create favorable conditions for colonization. Reference Nagano, Kuronuma and Kitamura21,Reference Williams, Armbruster and Arduino35 Moreover, decreased chlorine concentration and desuetude of specific faucets and drainage structures may also contribute to water contamination. Reference Gan, Kurisu and Simazaki36 Finally, biofilm formation in the mesh of aerators and rectifiers, which are installed on faucets to reduce splashing and are known to harbor NTM, can expose patients to the pathogen directly through the use of showers, drinking fountains, and contaminated medical devices.

In the present study, MLST suggested that the 12 isolates of M. lentiflavum from the clinical samples and environmental cultures were genetically identical. These isolates were derived from three inpatients in the same intermediate care unit at different times, from two patients in different wards, and from the environment (three samples) during the current cluster, and from four inpatients in different wards during the previous, hypothetical cluster. The genetic concordance of the isolates suggested that the M. lentiflavum cluster had existed since at least 2023; the identical strain might have spread nosocomially to the inpatients, who had a high risk of contamination by virtue of their continuous exposure in the hospital. A comprehensive environmental investigation following the implementation of the infection control measures found no M. lentiflavum in the hospital’s water storage tank or in the tap water in the staff facilities and break rooms, the pathogen being isolated only from tap water in multiple patient rooms. The present study also revealed that the M. lentiflavum cluster was eliminated after decontamination of the aerators. These findings suggested that the contamination of the hospital water supply likely occurred via the peripheral water supply system, which included the faucets and aerators. Despite the frequent association of contaminated water supplies with NTM outbreaks in the healthcare setting, the optimal method of decontaminating the water supply system, including faucets, sinks, etc., has yet to be established. Furthermore, a hospital’s water supply can serve as a transmission of drug-resistant pathogens that may cause healthcare-associated infections (HAI). Reference Kizny Gordon, Mathers and Cheong37 Although the decontamination process at the study center, which involved manual cleansing of the faucets followed by chlorination, successfully eliminated M. lentiflavum, a previously reported outbreak of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens originating in the hospital’s water supply system required the building’s contaminated reservoir to be replaced entirely. Reference Carroll, Michelin and Craig38 Given the potential for a hospital’s contaminated water supply system to transmit HAI, a standardized disinfection protocol focusing on preventing biofilm growth in water pipes, faucets, etc. is needed.

The present study also highlighted strategies for treating M. lentiflavum-related pulmonary diseases. In this study, two patients met the ATS criteria for the diagnosis of M. lentiflavum infection. Nevertheless, the treating physicians failed to administer antimicrobial therapy, possibly because of their lack of awareness about nosocomially transmitted, NTM-related pulmonary diseases, their failure to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility of the pathogen, the general rarity of M. lentiflavum or the inadequate frequency of mycobacterial cultures. Although not all patients with NTM who meet the ATS diagnostic criteria necessarily require antimicrobial therapy, a careful and informed discussion regarding the initiation of treatment should be undertaken.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of the 12 isolates indicated low MIC 90 for both levofloxacin and clarithromycin, suggesting that these agents may be administered as combination therapy. Because mycobacterial cultures and antimicrobial susceptibility testing are time-intensive, using a rapid method of identifying bacterial pathogens, such as the MALDI-TOF, should be encouraged. More importantly, previously reported information about the antimicrobial susceptibility of rare NTM species can help determine which antimicrobial regimen is the most effective.

The present study has several limitations. Since September 2024, there have been no follow-up investigations to confirm the elimination of M. lentiflavum at the study center. However, the pathogen has not been detected in any inpatients since then. While the present outbreak investigation used clinical culture samples obtained from symptomatic inpatients, it is possible that other patients with M. lentiflavum colonization were overlooked. Since some patients submitted only a single sputum sample for culturing, the number of cases of NTM-related pulmonary disease due to M. lentiflavum might have been underestimated. Last, contamination of the plumbing system was unable to be confirmed because no biofilm samples from the plumbing system were cultured.

The present study described a nosocomial cluster of M. lentiflavum colonization and infections at a Japanese tertiary care center. The hospital’s water supply system, especially the faucets, appeared to be the source of contamination, which led to the development of symptomatic, NTM-related pulmonary disease in two patients and colonization in the others. Despite there being several, previous studies of NTM clusters originating in a hospital’s contaminated water supply system, no standardized protocol for disinfecting a water supply system has been established; guidance on the appropriate maintenance of the hospital water supply system, including individual components, such as faucet aerators, is urgently needed. As various NTM species are associated with contamination of the water supply system, the accumulation of clinical and microbiological evidence of diseases caused by rare NTM species, including M. lentiflavum, will provide much-needed information on appropriate antimicrobial countermeasures.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2025.10250.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

H.H. designed the study. S.O. J.N. Y.N. and Y.T. obtained clinical data and collected culture samples. M.I. K.S. and Y.M. performed microbiological investigation. S.O, J.N, and H.H. analyzed and interpreted the data. S.O. and H.H. drafted the article. H.H. revised the manuscript. All the authors critically reviewed the text and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) [grant number JP23 gm1610013] and JSPS KAKENHI Grant (23H02634, 23H00451). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests

H.H. received honoraria from Shionogi, Moderna, bioMérieux, Pfizer, Takeda, and Pfizer and consulting fees from Solventum and Moderna, which were unrelated to the work. All the other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.