Most contemporary Colombian documentaries focus on war and peace. This is not surprising, because the defining moment in recent Colombian history is the 2016 peace agreement between the national government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The conflict between these two actors began in the mid-twentieth century, but over the course of roughly sixty years, the war evolved into a complex struggle between left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries, drug cartels, and the Colombian state.Footnote 1 While many recent documentaries focus on the shift from war to peace, this thematic unity contrasts with editorial and cinematographic diversity. For example, consider the difference between Relatos de reconciliación—an animated documentary about the wartime tragedies of landless peasants—and Las razones del lobo, which chronicles the wartime lethargy of country-club aristocrats.Footnote 2 Such examples highlight the diverse ways that filmmakers document the postconflict period that began in 2016. Despite this diversity, there is one conspicuous scene that appears across multiple documentaries: the Cartagena Convention, during which the former Colombian president (Juan Manuel Santos) and the former commander of the FARC (Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, alias Timoleón Jiménez) signed an agreement to end the war.

While most documentaries do not show the Cartagena Convention, this scene appears in more documentaries than any other scene. To offer a few examples, the Cartagena Convention appears in La niebla de la paz, Transfariana, La sinfónica de los Andes, La negociación, and El silencio de los fusiles.Footnote 3 This list is not exhaustive. But it shows that the Cartagena Convention is a potent symbol of peace in many documentaries. Although this convention had symbolic potency, it had no legal potency. In fact, it was a complete failure.

Less than a week after the convention, voters rejected the peace agreement in a referendum, shocking everyone. Considering this outcome, one would assume that a documentary about the postconflict period would mention the referendum. While many documentaries do, a surprising number do not. Instead, these films misrepresent the Cartagena Convention as the end of the war. This editorial move encourages us to read that convention symbolically rather than historically or literally. Such a reading is also encouraged by the symbolism of the convention itself. For example, everyone attending the event wore white; the Colombian flag (which is usually three stripes of yellow, blue, and red) appeared with a fourth stripe of white; and the politicians signed the peace agreement with a bullet that had been repurposed as a pen. Thus, the convention, along with the documentaries that misrepresent that convention, jointly encourage us to read that event as an abstract symbol.

Building on these observations, this essay examines how three documentaries relate the Cartagena Convention to Colombia’s postconflict practice of river symbolism. This symbolic practice appears in diverse contexts. For example, in the judicial world, a new paradigm—one that is rapidly spreading through Colombian courts—recognizes natural objects as legal subjects. Rivers make up more than half of the objects that have been recognized as subjects, and some rulings based on this “rights of nature” framework describe the relationship between a river’s rights and the challenges of building peace.Footnote 4 Strikingly, the first ruling that recognized the rights of a river was handed down during the same month in which Congress ratified the 2016 peace agreement.Footnote 5 Similarly, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace—which manages Colombia’s transitional justice process—recently started recognizing rivers as victims of war.Footnote 6 Thus, there is a conspicuous use of rivers as legal symbols in Colombian peace building.

These legal examples are echoed in the arts. For instance, Bogota’s Museum of Modern Art hosted two exhibits that reflected on the role of rivers in the Colombian conflict. Ríos y silencios, on the one hand, exhibited a series of paintings from ex-combatants that portrayed rivers as key characters in illustrated stories about war.Footnote 7 Río Abajo, on the other hand, exhibited photographs of clothes underwater. Each article of clothing belonged to a civilian who was murdered or disappeared during the war.Footnote 8 These artistic and legal examples show that watery symbols are not only anecdotal features of the documentaries reviewed in this essay; watery symbols are also part of the broader semiotic ideology of Colombian peace building.

Thus, rather than critiquing documentaries for misrepresenting the Cartagena Convention, this essay examines how each film engages rivers as symbolic lenses for interpreting that convention. In other words, this essay does not ask what the Cartagena scene does in each film, but rather what the Cartagena scene looks like when viewed through the lens of a river. This approach not only provides unexpected frames of reference for understanding the Cartagena Convention but also invites readers to appreciate the broader Colombian practice of postconflict river symbolism.

Cuando las aguas se juntan

Premiered in 2023, Cuando las aguas se juntan (When waters come together) is the most recent documentary directed by the Colombian journalist and filmmaker Margarita Martínez Escallón. Like many of Martínez’s eighteen documentaries, Cuando las aguas se juntan examines the Colombian conflict. For instance, her prior film, La negociación (2018), offers a behind-the-scenes look at the four-year negotiation that led to the 2016 peace agreement. Although Cuando las aguas se juntan sticks to the theme of conflict, it is uniquely feminist, highlighting war crimes against women and the role of women in peace building.

The documentary opens with a poetic link between women and water. The voice-over states: “Women, like waters, grow when they unite. When we are together, we grow. The Amazon River does not exist without tons of tiny rivers. It doesn’t exist. And a dignified life for women does not exist if we are not united.”Footnote 9

Such women-water metaphors resonate with the popular tradition of using waves to periodize feminism. That is, Cuando las aguas se juntan’s analogy between women and rivers resembles metaphors like second-wave feminism. Such wave-based metaphors have received a fair share of criticism. Garrison, for example, argues that the “primary problem with the oceanic metaphor is that it limits our ability to recognize difference” within the category “woman.”Footnote 10 Similarly, Wylie suggests that waves just “rise and fall again and again in the same place.”Footnote 11 Considering these critiques, rivers could offer a better alternative. Regarding Garrison’s critique of waves as homogeneous, rivers and their tributaries illustrate diverse water sources coalescing into a single stream. In this sense, rivers illustrate diversity better than waves. Regarding Wylie’s critique that waves rise and fall in the same place, rivers have a clear trajectory. They begin in the mountains and end in the ocean, where they are equalized with their surroundings. Thus, rivers are not only more diverse than waves; they are also directed toward an ultimate equality.

Thus, we can read Cuando las aguas se juntan’s opening voice-over as an intervention: River-based metaphors for feminism are superior to wave-based metaphors. The film reinforces this voice-over through a series of synchronic scenes that illustrate how rivers unite: The first image is a close-up of a single drop of water, dangling from the tip of a flower bud. This droplet of water falls and splashes into a puddle. These zoomed-in scenes cut to a horizontal pan of rivulets that trickle down the side of a moss-covered cliff. The screen shifts to an ascending angle of a highland stream that crashes down a boulder-filled rock face. This crescendo of aquatic coalescence continues with a perennial stream taking center stage. It carves a channel into the soil, exposing the boulders beneath and preventing plants from crowding its path. Then, through a meshwork of green leaves, we catch our first glimpse of a real river—sunbeams glinting off mimetic ripples. Finally, a mighty brown river of voluptuous major chords lumbers into the frame; a drone flying above captures the river’s smooth flow of muddy molasses, lazily passing through a canyon of mahogany rocks (Figure 1). The screen goes black, and a coda of harp music transports us to the title page of the film.

Figure 1. Dispersed waters unite into a single flow, creating a metaphor for women’s activism.

Although Cuando las aguas se juntan begins in this experimental space—intertwining image and text to propose a novel feminist poetics—it quickly shifts gears. The rest of the film uses the aesthetics of newsreel realism and straightforward narrativity. The interview format is paramount, providing space for women to recall their wartime encounters with sexual violence. Most interviewees are introduced by aerial shots of the regions where they live. Simultaneously, text appears on screen, naming where the shots were captured. This technique of geographic contextualization depicts Colombia as a landscape of sexual violence. However, the film also suggests that Colombia is a landscape of activism: Every interviewee in the film works for women’s rights, and the specific organization with which they are affiliated appears on the screen beneath their names.

Toward the latter half of the film, the discussion turns to the 2016 peace agreement. Sticking to gendered thematics and interviewing techniques, this section of the film focuses on the women who were involved in the negotiation. These female interviewees highlight the importance of UN Resolution 1325, which expressly calls for women’s participation in peacemaking.Footnote 12 While the Colombian peace accords began as a discussion among men, women from both sides of the debate used Resolution 1325 to push for the formation of a subcommittee on gender. This subcommittee not only brought female representatives to the negotiation table but also incorporated women’s issues into the text of the legal document. Such efforts inaugurated the final draft of that document as the first peace agreement in the world to incorporate an explicitly gendered perspective.

This subsection of the film culminates with scenes from the Cartagena Convention. Similar to the other films described in this essay, Cuando las aguas se juntan uses those scenes to symbolize the end of the Colombian conflict, even though they are not. Although scenes from the Cartagena Convention account for only fifteen seconds of the entire documentary, they nonetheless offer an interesting counterpoint to the rest of the film: Cuando las aguas se juntan is a film about women, but these scenes from Cartagena focus on men.

At first, Cuando las aguas se juntan shows an entourage of state negotiators sitting on the left side of the stage. Next, it cuts to an entourage of FARC negotiators sitting on the right side of the stage (Figure 2). There are twenty negotiators in total, ten on each side, and each group is arranged into two rows of five. On both sides of the stage, there is one woman in the front row and two women in the back row. These details might seem extraneous. However, in such a high-stakes and meticulously planned event as the Cartagena Convention—which was specifically designed to convince the public to vote in favor of the peace accords—it is striking to note the symmetrical organization of gendered bodies on either side of the stage.

Figure 2. FARC negotiators arranged in two rows of five, with one woman in the front row and two women in the back row.

After showing both teams of negotiators, Cuando las aguas se juntan then shows the former Colombian president shaking hands with the former FARC commander in chief. Within the context of a film about women, this scene runs counter to the broader narrative, as it portrays the end of the war as two men shaking hands. In these scenes, Cuando las aguas se juntan encourages us to notice the gendered aspects of the Cartagena Convention.

In the same way that we can read the opening simile of Cuando las aguas se juntan as an intervention that offers a river-based alternative to the tradition of wave-based metaphors for feminism, we can also read Cuando las aguas se juntan’s emphasis on women within the Cartagena Convention as an intervention that offers new readings of that potent scene. In other words, if we use this film’s river symbols as a guide to interpreting its representation of the Cartagena Convention, then Cuando las aguas se juntan shows us that water coalescing into a river is a symbol for women’s empowerment; subsequently, we can use that lesson on river symbolism to notice the symmetrical organization of women’s bodies on stage at the Cartagena Convention.

Cantos que inundan el río

Cantos que inundan el río (Songs that flood the river, 2022) is Luckas Perro’s first feature-length film. Trained as a visual anthropologist, Perro’s prior work includes more than a dozen shorter-length fiction and nonfiction films. But Cantos que inundan el río is his defining ethnographic statement, having won best feature at the Society for Visual Anthropology’s 2022 Film and Media Festival. Perro’s ethnographic approach shines through in the film’s aesthetic of sensory immersion, distinguishing it from the realist aesthetics of more conventional documentaries like Cuando las aguas se juntan.

Cantos que inundan el río focuses on an Afro-Colombian woman named Ana Oneida Orejuela Barco. Orejuela lives in the village of Pogue located along the Bojayá River in the Colombian Pacific. She is renowned for her ability to compose alabao—a genre of call-and-response songs that mourn the dead and guide souls through the afterlife. Drawing on this otherworldly theme, the film develops an aesthetic that slips into and out of reality and surreality. The film moves between ordinary depictions of Orejuela’s life in Pogue and immersive dreamscapes of riverside vibrations. Such juxtapositions highlight the dual ontology of the alabao genre, which creates musical bridges between materiality and spirituality.

These juxtapositions also allow the film to experiment with sensorial immersion. Commenting on these immersive dreamscapes, the director describes the film as a “sensory journey.” Viewers are able “to immerse themselves in the jungle, to sense themselves inside the banana plots, navigating the river or feeling the breeze vibrate with the leaves that fall from the trees.”Footnote 13 In this sense, Perro’s film is less of a documentary about Afro-Colombian music and more of a submersion into the socio-ecological worlds of that music.

Orejuela’s compositional practice is a key throughline that ties this film together. In one of the film’s earliest scenes, Orejuela is sitting down with pencil and paper, composing the libretto for her latest song. Lines of text about a river accumulate on the page. Then Orejuela starts singing, teasing out the synchronies between melody and text. The film cuts, and Orejuela is back to writing, tweaking lyrics and adding lines. An intermission of riverside scenes intercedes. But this intermission is integral to Orejuela’s music, as it illustrates the socio-aquatic contexts of alabao songs. When we return to the music, Orejuela is teaching a different song to one of her neighbors. This new song is also about a river. The scene cuts: Orejuela and her neighbor appear in a circle of Afro-Colombian women. They are teaching these women the same song they had been practicing as a duet. The recital ends and we return to scenes of riverside life.

About halfway through the film, there is an abrupt shift to low-grade archival footage: military helicopters, artillery shells, gun turrets, camouflaged jungle boats, and former Colombian president Andrés Pastrana shaking hands with the residents of a village known as Bellavista. Only at this point in the film do we realize that Orejuela’s village, Pogue, is a few kilometers upstream from Bellavista, the site of the infamous 2002 Bojayá massacre, in which a bomb killed more than one hundred civilians hiding inside a church. We also learn that the massacre prompted Orejuela to start composing alabao songs.

We see Orejuela standing inside the vine-covered ruins of the bombed-out Bellavista church. Speaking in voice-over, she says: “I spoke with them during the night. I asked them to give me the strength and opportunity to tell others … about what had happened to them.” The film cuts to a close-up of Orejuela’s face. She is singing a verse about the Bojayá massacre. As a chorus repeats Orejuela’s lines, the camera cuts to an aerial shot of the Cartagena Convention. From this angle, we see that Orejuela is on stage with her neighbors singing alabao songs at the Cartagena Convention. This angle also shows that the Cartagena Convention took place on a pier. A wide-angle shot returns to Orejuela and her neighbors singing on stage, the Caribbean Sea rippling over their shoulders (Figure 3). Another close-up of Orejuela’s face slowly zooms out. This zoom-out foregrounds Orejuela against the oceanic background. When the singing subsides, the former president and former rebel leader sign the peace agreement. The final scene of the Cartagena Convention is a close-up of their signatures. Then the film abruptly cuts back to ordinary scenes of riverside life, as if to say, “Despite the fanfare in Cartagena, nothing changed in Pogue.”

Figure 3. Orejuela and her neighbors sing alabao songs in the foreground while the Caribbean Sea ripples in the background at the Cartagena Convention.

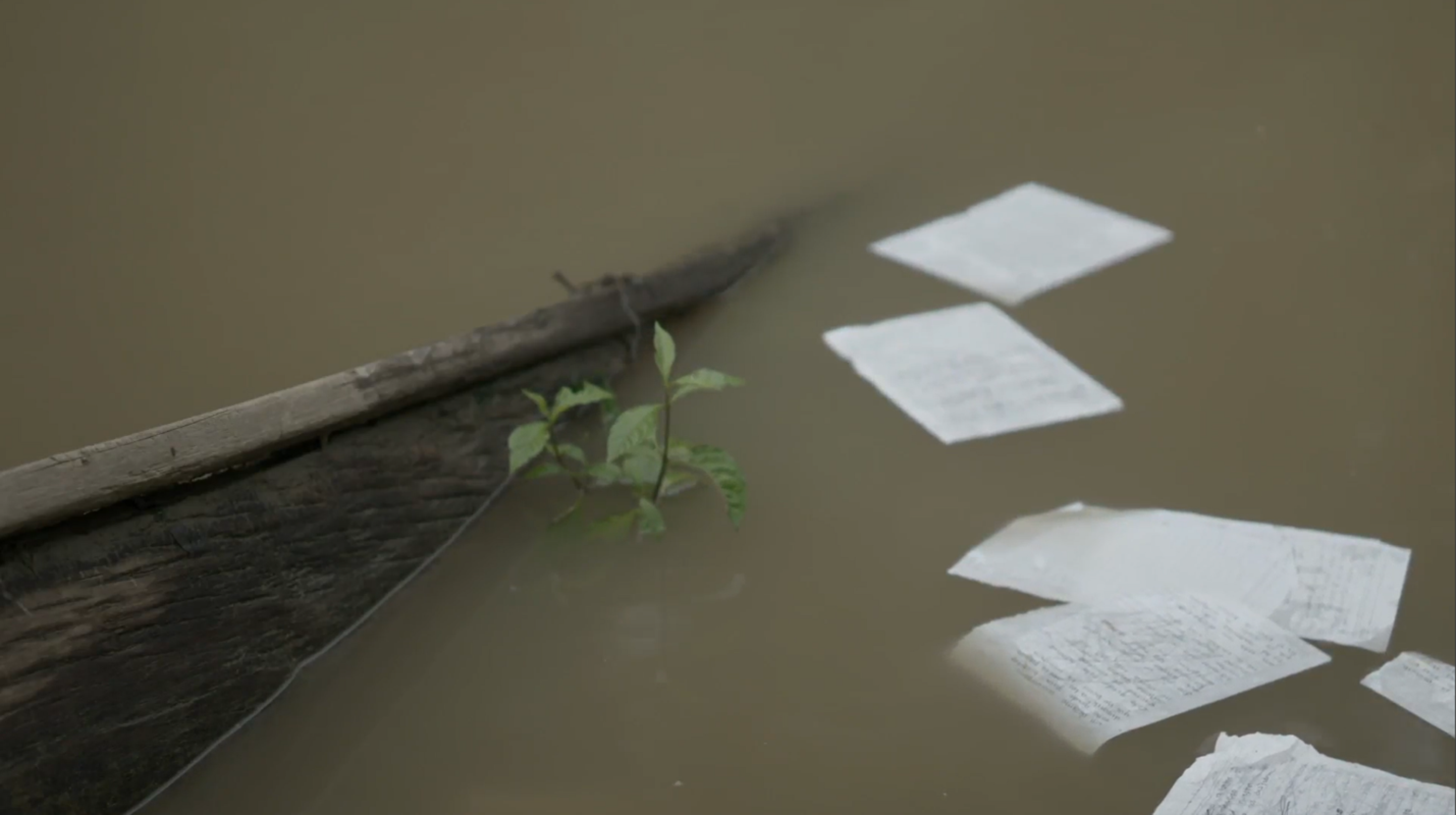

Later on, the film returns to juxtapositional aesthetics. Orejuela is lying down on her couch for a midday nap. Repetitive crescendos create a dreamy soundscape. Visually mimicking this auditory surrealism, the camera cuts to a close-up of the notebook where Orejuela writes alabao lyrics. Her hands are frantically flipping through the notebook, striking out words and ripping off pages. A boom brings the nightmare to an end. Orejuela is sitting on the couch where she was previously lying down. We are back in reality. But then the film slips into surrealism again, showing torn pages of crossed-out song lyrics from Orejuela’s notebook floating downriver (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Ripped-off pages of scribbled-out song lyrics drift downstream, creating a metaphor for the referendum that rejected the peace agreement signed in Cartagena.

These juxtapositional aesthetics (which combine reality with surreality) and the film’s thematic focus on the alabao genre (which combines songwriting with rivers) encourage a particular reading of the Cartagena Convention. Specifically, the film’s juxtapositional aesthetic asks us to compare, placing things side-by-side and observing how they relate. On the other hand, the film’s thematic focus on alabao calls our attention to songwriting and the riverine contexts of that songwriting. Thus, we can use the film’s side-by-side aesthetics and river-songwriting thematics to guide our interpretation of the Cartagena Convention. Such an interpretation juxtaposes the symbol of the convention to the alabao genre to observe how writing and water inform both.

Water provides the background for both the alabao genre and the convention. Not only do Afro-Colombian musicians who sing alabao live beside rivers; every song in the film mentions a river.Footnote 14 Thus, the film’s thematic focus on the alabao genre draws the viewer’s attention to water, while its juxtapositional aesthetic invites comparisons with other watery contexts, such as Cartagena. Recall that the convention took place on a pier, that the film’s cinematography foregrounded the Caribbean Sea, and that the convention itself was a high-stakes, meticulously staged ceremony. Based on these recollections, we could hypothesize that the organizers of the convention deliberately chose a watery site for the ceremony. We could justify that hypothesis by considering what other options the organizers had. For example, it would be hard to argue that Cartagena was the most politically compelling site for the convention. There are other Colombian cities that are more obviously related to the conflict. Thus, there was probably another reason for selecting Cartagena. Using this film’s watery thematics as a guide, we could infer that the signing ceremony took place in Cartagena because the Caribbean Sea offered a peaceful setting.

Just as Cantos que inundan el río encourages us to compare water across contexts, this film also encourages us to compare writing across contexts. As described earlier, the documentary first introduces the alabao genre by showing Orejuela writing lyrics, which precedes and enables the performance of song. Similarly, in Cartagena, it was writing (the word-by-word negotiation of a legal document) that ultimately brought an end to the war. The climax of that convention was the act of signing: two signatures sealed the agreement. Here, as with alabao, the writing and signing of the peace agreement precede the implementation of the written word. Yet what is written is not always enacted. Indeed, the dream sequence in which Orejuela scribbles over lyrics, rips out pages, and throws them into the river is a symbol of what transpired during the referendum that rejected the peace agreement. In this way, Cantos que inundan el río’s juxtapositional aesthetics and thematic concerns suggest that writing and water are foundational elements in the symbolic language of both the alabao genre and the Cartagena Convention.

Del otro lado

Iván Guarnizo’s award-winning documentary Del otro lado (On the other side, 2021) marks his debut as a feature-length director. Although Guarnizo has contributed to nearly a dozen documentaries, his most notable work has been as an editor. Trained in both film and anthropology, he approaches Del otro lado as a form of visual auto-ethnography. Unlike many directors of postconflict Colombian documentaries who leave their urban homes to document the lives of the rural poor, Guarnizo departs from his urban home to document his personal history. The film follows the director and his brother as they retrace the events of their mother’s kidnapping and seek dialogue with her former captors. Their mother, Beatriz Echeverry, was kidnapped and held hostage by FARC revolutionaries for 603 days before being released. Although the experience was traumatic, Echeverry formed bonds with some of her captors. She even became a “maternal figure” to one of her wardens, a young man named Güerima.Footnote 15 Yet Guarnizo did not fully grasp how important Güerima had been to his mother until after he read her diary. It was Guarnizo’s act of reading that sparked his desire to find Güerima.

However, before Del otro lado introduces us to these protagonists, the film offers an early articulation of its topographic approach to the symbolism of water and the Cartagena Convention. Notably, Del otro lado begins—rather than ends—with the Cartagena Convention, moving in opposite chronological direction to the other two films. In this way, just as maps orient travelers before a journey, the film’s decision to foreground the peace-building convention serves to topographically orient viewers before embarking on an audiovisual exploration of postconflict reconciliation.

This topographic aesthetic is reinforced by a poem about scuba diving, which appears on screen before any other images. Its third line reads “The words are maps.”Footnote 16 Thus, within the film’s opening frames, a semiotics of mapping is already in place. Following this poem, most of Del otro lado’s water symbols appear as representations of rivers on maps.

Del otro lado’s first river scene shows thick blue lines and thin black lines on a map. These lines, representing rivers and tributaries, are overshadowed by the scene’s centerpiece: Echeverry’s diary. Captured in close-up, the director’s hands flip through his mother’s diary. These “close-ups of the mother’s diary … present the pages like a map.”Footnote 17 Thus, the first river scene builds out Del otro lado’s topographic aesthetics.

The second river scene kicks off with the director’s finger tracing the contours of a mapped river. His finger halts. He draws an X, beside which he writes a word, but it is too blurry to discern its meaning. His finger continues following the river before halting again, where he draws a second X. Beside this X, he writes: “1st night?” This question illustrates Guarnizo’s confusion in attempting to map out his mother’s kidnapping. Then, his hand dives back into Echeverry’s diary, scouring its pages for more topographically transcribable text. This back-and-forth between map and diary frames rivers as textual and topographic tools for orienting Guarnizo.

The third river scene is a single panning shot. It follows a topographic representation of the Inírida River. The scene opens with an X and the word abduction written beside the river. Then, the word mavicure comes into the frame. The director’s voice-over recounts that his mother was visiting the Mavicure Hills when she was kidnapped. The voice-over pauses as two familiar etchings come into focus: X and 1st night? When these etchings pass into the periphery, the voice-over resumes: “The diary entries mention the places where [Echeverry] spent the first five days. After that, her tracks are lost in the jungle.” The camera halts on two final inscriptions: X and last trace. These inscriptions show the last point at which Echeverry still had her geographic wits about her. After that, Echeverry did not know where she was. In other words, without rivers, she was lost.

The final river scene shows the Guarnizo brothers talking with Güerima—the ex-guerrilla who held their mother hostage (Figure 5). Güerima uses a map to narrate Echeverry’s captivity. Here, Güerima says, is where we beached the boats. There, he gestures, is where we crossed from the Inírida River to the Guaviare River. Once we got to the Guaviare, we set up camp. Guarnizo is surprised, explaining that his mother’s diary said she was always camping along smaller creeks, never along major rivers like the Guaviare. This disorientation reinforces the orientational role of rivers: the Inírida and Guaviare Rivers topographically orient these men as they map out Echeverry’s captivity; simultaneously, these rivers narratively orient Güerima’s oral history (in conversation) and Echeverry’s written history (in her diary). Therefore, rivers appear as tools of topographical, conversational, and textual orientation.

Figure 5. The director and his brother talk with the man who held their mother captive, while topographic representations of rivers orient their conversation.

These river scenes, along with the introductory poem and the foregrounding of the Cartagena Convention, encourage us to interpret that convention topographically. Del otro lado’s topographic take on that convention is seen most clearly through the film’s emphasis on the audience. Alternatively, the other two films in this review focus on the protagonists at that convention. Although Cantos que inundan el río includes a few scenes of the audience, those scenes are typically shot from far away, anonymizing the spectators. Comparatively, Del otro lado spends more time on spectators’ faces. Thus, by zooming out a bit—but not so far that the onlookers become anonymous—Del otro lado offers a less protagonistic view of the Cartagena Convention and a more contoured view of that convention’s facial landscape (Figure 6). Just as a map is a slightly zoomed-out illustration of reality—but not so zoomed-out that the contours lose their meaning—so, too, is Del otro lado’s portrayal of the convention a slightly zoomed-out overview of the facial landscape. This cinematography proposes a topographic reading of the convention.

Figure 6. A topographic representation of the audience at the Cartagena Convention.

The film’s audio also frames the convention topographically. When Del otro lado shows the faces of the spectators, the following voice-over ensues: “My brother and I could never understand [our mother’s] affection for many of the guerrilla fighters who held her captive, and who might be [at the Cartagena Convention] dressed in white.” This paranoid voice-over creates a phantom audience member: Echeverry’s kidnapper, who might be lurking in the crowd. After creating this phantom, the film follows the Guarnizo brothers on their adventure to reconcile with that phantom. In other words, the voice-over encourages us to study the convention as if it were a facial map of postconflict phantoms; subsequently, the film zooms in on the Guarnizo brothers’ adventure as they seek out the phantom face of Echeverry’s kidnapper. Such audiovisual techniques portray the Cartagena Convention as a topography of postconflict hauntology. Situating this idea as an analogy, we could say: Just as a map is a zoomed-out overview while an adventure is a zoomed-in experience, so, too, is Del otro lado’s depiction of the Cartagena Convention a zoomed-out overview of postconflict phantoms while the film itself is a zoomed-in adventure that comes face-to-face with one particular phantom: Güerima.Footnote 18

In summary, Del otro lado’s engagement with the Cartagena Convention is topographic because its foregrounding orients the film’s journey, because its cinematography offers a landscape view of spectators’ faces, and because its audio asks the viewers to study this facial landscape before zooming in on one particular face.

Conclusion

The Cartagena Convention is the most commonly depicted scene in Colombian postconflict documentaries. Many films situate that scene in its historical reality, highlighting the failed referendum shortly after the convention. However, a surprising number of documentaries do not mention the referendum. Instead, these films use the convention as a symbol for the end of the war. This symbolic rather than literal treatment of the convention creates an opportunity to explore how that convention relates to other symbols. As the films reviewed here also engage rivers, this essay asks how the Cartagena Convention relates to the broader practice of postconflict river symbolism. Specifically, this essay uses each documentary’s river semiotics as an interpretive guide for understanding that documentary’s representation of the convention. This approach depicts the convention as a gendered performance, a juxtaposition of water to writing, and a topographic map. Such readings offer unexpected vistas for viewing the convention as well as partial glimpses into the semiotic ideology of river symbols that is emerging in postconflict Colombia.