In February 1816, Louis Victoire Papillon de la Ferté (1784–1847),Footnote 1 intendant of the Menus-Plaisirs (Royal Entertainments) and director of the Paris Opéra,Footnote 2 sent a report to his superior Jules Jean-Baptiste François de Chardebœuf (1779–1857), the Count of Pradel and Minister of the King’s Household, advising against reviving the opera Fernand Cortez ou La conquête du Méxique (1809).Footnote 3 Composed to glorify Napoleon and justify the French invasion of Spain in 1808, the opera narrated the Spanish conquest of the Mexica Empire (1521) by portraying the sixteenth-century conquistadors and Aztecs as stand-ins for the nineteenth-century French troops and Spaniards, with the character Fernand Cortez – based on the historical figure Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) – symbolizing the emperor himself. The opera enjoyed some success after its world premiere in November 1809, but was withdrawn from the programme three years later due to a propagandistic message which, in stark contrast to the reality of war, had apparently become counterproductive.Footnote 4 However, in 1816 Papillon de la Ferté seemed unconcerned by the imperial connotations of the opera. With Napoleon defeated and the House of Bourbon restored, he did not cite political reasons for dismissing the revival. On the contrary, he argued that staging it would cost as much effort and time as producing a new opera. He also claimed that the opera’s characteristics posed supplementary difficulties, as it included three acts, multiple ballet sequences, a cavalry charge with real horses, and lavish sets and costumes. Relying on the judgement of the Opéra’s technical directors, he was informed that the sets would need to be completely rebuilt and that the chorus and dancers would have to relearn the entire work, rehearsing it thoroughly before each performance.Footnote 5 He even mentioned financial concerns, estimating that the total cost – over 100,000 francs – would jeopardize the institution’s finances.Footnote 6 But after some negotiation, and with a new libretto, the Count of Pradel ordered the opera to be revived ‘without any delay’.Footnote 7 Ironically, despite its original ties to imperial propaganda, Fernand Cortez enjoyed artistic and commercial success after 1817, running continuously throughout the entire Bourbon Restoration and most of the July Monarchy.

As this apparent paradox suggests, the reception of an opera can depend on multiple factors governed by unpredictable contingencies. The shifting trajectory of Fernand Cortez, with its multiple versions (1809, 1817, 1824 and 1832),Footnote 8 was closely tied to the erratic path of its composer, the Italian Gaspare Spontini (1774–1851), who lived in Italy, Paris, and Berlin in a constant pursuit of status and recognition.Footnote 9 And it was also shaped by the lives and literary careers of its librettists: Joseph-Alphonse Esménard (1770–1811), a poet and imperial censor associated with the empire’s ‘literary cohort’,Footnote 10 and the writer Etienne de Jouy (1764–1846), known for his remarkable political adaptability.Footnote 11 Their personal itineraries, traced by their skill in navigating the ‘contingency of the moment’,Footnote 12 offer a vivid example of the variable forces that defined the French cultural and political landscape of the early nineteenth century, famously described as a société des girouettes (‘society of weathervanes’) in a scathing publication shortly after Napoleon’s fall in 1815.Footnote 13 However, they also symbolize the flexibility of the frameworks of representing and interpreting an opera that, though rarely performed today, has garnered attention in musicology and remains a valuable subject for historical critique.

Fernand Cortez has often been examined as an aesthetic bridge from classical to romantic opera (or even to French grand opéra genre) and, most notably, as a reflection of Napoleonic imperialist discourse.Footnote 14 However, concentrating mostly on the original 1809 version, historiography has to date regarded Fernand Cortez as a propagandistic artefact, prompting a reductionist vision of the opera itself and its performing history, linked inextricably to imperial narratives and Napoleon’s fate.Footnote 15 Although Fernand Cortez was motivated by the regime’s propagandistic interests, it was also connected to personal agendas that extended beyond the directives of authorities. Rather than interpreting it solely as a unidirectional tool of state power, this study situates the opera within a dynamic field, influenced by individual agency and pragmatic considerations.Footnote 16 In fact, the political crisis of 1814–1815, marked by three regime changes in just over a year, obliged many artists (most notably Spontini and Jouy, as Esménard had died in 1811) to adapt their loyalties in order to preserve or restore their status – along with the associated material advantages – turning opera into a symbolic battleground in that effort. In this sense, historiography has overlooked the financial complexities of Fernand Cortez, limiting itself – somewhat anecdotally – to mentioning the high cost of the original production. As implied by Papillon de la Ferté’s carefree attitude toward the Napoleonic connotations of the opera, an examination of the economic dimension of Fernand Cortez, including its box office performance, broadens the scope of study, particularly when these data are compared with prevailing narratives concerning the political significance of the work.Footnote 17 As will be argued in this article, it is necessary to approach Fernand Cortez as a symbolic device that, between the premieres of the first and second versions (1809–1817), offered a multiplicity of meanings and ambivalent uses to the musical, literary and institutional actors directly involved in its production and exploitation.

This methodological programme connects with another dimension that scholarship on Fernand Cortez has already explored, but which still requires further insight. The historical imagination, used as a framework for explaining the present (evident in the historicism of the libretto and the couleur locale of the score), was achieved through a transposition that was chronological, symbolic and even national, as the political reality of contemporary France was projected onto the Spanish conquest of the Mexica Empire.Footnote 18 Yet, it could be argued that this historical reimagining, as seen in certain comparable operas,Footnote 19 also created a symbolic space to stage the hegemonic aspirations of either the empire or the monarchy. In this context, theatrical representation of historical narratives required the imaginary construction of models of reference and otherness to frame the propagandistic message.Footnote 20 It is therefore relevant to ask what symbolic role a declining Spanish Empire played in the political legitimation of the empire and the monarchy in France.Footnote 21 The choice of an episode from Spanish imperial history in Fernand Cortez invites reflection on Spain’s position as a mirror or a floating signifier of French politics.Footnote 22 But this becomes more compelling when the 1809 and 1817 versions of the opera are considered alongside the premiere of Pélage, ou le Roi et la paix (1814), composed by Spontini and Jouy during Napoleon’s exile on Elba – a pièce de circonstance that celebrated Louis XVIII by invoking the medievalist myth of the King of Asturias, Pelayo.Footnote 23 Pélage, not widely explored in the historiography and often dismissed as mere propaganda, deserves reconsideration. Evaluated so far through the same reductionist perspective used for Fernand Cortez, it raises valuable points of discussion regarding the influence of the authors’ personal agency in the self-interested instrumentalization of the historical plot and the opera itself. Hence, both works may encourage deeper reflection on Hispanic–French cultural transfers, particularly in relation to the development of narratives about collective identities aimed at fostering internal social consensus in France.Footnote 24 In short, this study proposes an investigation grounded in political and material issues, which considers Fernand Cortez and Pélage both as reflections of the political evolution from the First Empire to the Restoration, and as spaces of symbolic conflict where individual struggles (concerning status, reputation, positions, and artistic survival) were also played out.Footnote 25

In what follows I examine the ambivalent uses of Fernand Cortez and Pélage within a Spanish imaginary mediated by French politics, focusing on their role in legitimating both the French Empire and the Bourbon monarchy, and how these political objectives intersected with professional interests. This paper is organized into three sections, which follow the timespan of the staged versions of Fernand Cortez in Paris.Footnote 26 Building on existing literature, the first part briefly explores the relationship between the opera’s plot and the historical context of 1809–1812. However, it also considers how the economic performance determined its place in the Opéra’s repertoire – thereby offering a more nuanced argument to the often-repeated but underexamined view that its 1812 withdrawal was solely due to an inconvenient political message. The second section considers Pélage as a lens to analyze the convergence of political and material interests that shaped the artistic development of Spontini and Jouy, whose ability to exploit imperial and royal needs between 1814 and 1815 provided them with opportunities for distinction and reputational redefinition.Footnote 27 The final section investigates how the fall of Napoleon, along with financial impositions, affected the 1817 revival of Fernand Cortez. In doing so, the study brings to light the connections between French operatic representations of Spanish history and the political challenges of rival regimes in France at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Beyond the Political: The Economic Burdens of Fernand Cortez (1809–1812)

Papillon de la Ferté’s reports on the viability of Fernand Cortez made no mention of its connection to imperial legitimation discourses, although this point was evident when the opera premiered on 28 November 1809. As previous studies have shown, the creation of Fernand Cortez responded to the political needs of the time – namely, the need to shape favourable public opinion toward the military campaign in Spain, within the context of the Peninsular Wars (1808–1812).Footnote 28 Divided into three acts, the opera may be interpreted as an imperial narrative which, by displaying and using a wide variety of historical sources and references (musical local colour and historiographical sources, among others), attempted to show an apparent historical authenticity in order to strengthen the French imperial and expansionist objectives.Footnote 29

In Act 1, set in the Spanish camp by the sea, Cortez stops a mutiny by promising his soldiers, eager to sail home, a glorious victory. Beyond this promise of glory, Cortez is also pursuing other, more immediate goals. On the one hand, he seeks to save his brother Alvar, held captive along with other Spanish soldiers by the Aztecs. On the other, to remain at the side of his lover Amazily, the niece of Montézuma, who has abandoned her people and converted to the Christian religion. Télasco, Amazily’s brother, arrives at the camp to propose a peace truce and prevent the conquest, offering valuable gifts to the Spaniards, who seem inclined to accept this generosity. Concerned about the attitude of his soldiers, Cortez orders a cavalry charge as a show of strength and authority. Determined to achieve his aims, he refuses Télasco’s offer; the latter, in turn, demands that the Spaniards leave the country. In the midst of this growing rivalry, Cortez decides to set fire to the Spanish ships, demonstrating his resolve to fulfil his objectives and prevent a retreat back to Spain. Act 2, set in the mountains near Tenochtitlán, shows the Spanish troops advancing toward the capital to free Alvar and the soldiers. Meanwhile, the conflict between Télasco and Amazily intensifies. She is accused of treason and realizes that her people will not willingly release Cortez’s brother; indeed, the High Priest demands that either Amazily or Alvar to be executed. As Cortez prepares to attack, Amazily escapes to the city, intending to sacrifice herself. Act 3 opens with the Spanish soldiers and Alvar being carried to be sacrificed. Amazily suddenly appears, offering her own life in order to save the Spaniards. The High Priest accepts her proposal, but the Spanish offensive succeeds and prevents the execution: Amazily is saved, the prisoners are rescued, and the Aztec priesthood is destroyed. Everyone, including Télasco, acknowledges the superiority of the conqueror, who, in a display of magnanimity, chooses not to subjugate the defeated. The opera ends with a celebration of the union of the ‘two nations’.Footnote 30

The opera functioned as a historical mirror for contemporary reality. Several authors have extensively discussed on how argumentative strategies drew parallels between fictional and real individuals or institutions – Cortez symbolizing Napoleon, the High Priest representing the Inquisition, the Mexica evoking the Spanish people, and the Spanish soldiers mirroring French troops – in order to facilitate comprehension and popular support for the military intervention.Footnote 31 In fact, it has been argued that the reenactment of an alleged historical truth served as a political argument to justify the French invasion, since allusions to historical sources and the staging of non-European musical elements (for example, a traditional Aztec instrument and conventional musical expressions associated with exotic locales) could increase the audience’s distancing from the Mexica and promote their identification with the conquerors.Footnote 32 Early reception seems to confirm this point. The opera was praised in newspapers such as the state-controlled Gazette de France, or even in less pro-Napoleonic journals such as the Journal de l’Empire. Commentators applauded the spectacularity of the opera, along with the dramatic contrast between the Spanish and the Mexica, and the political relevance of the plot. Unlike other literary works with a similar theme, such as Voltaire’s Alzire ou les Américains (1736), which condemned the violence of the Spanish conquest of Peru, the Journal de l’Empire argued that Fernand Cortez emphasized the savage and uncivilized nature of the American peoples. According to this reading, Cortez was exalted as the leader who liberated the Mexica from barbarism. This view corresponded with contemporary perceptions of reality. The ‘cruelty of the Mexicans’ was equated with the ‘abominable sacrifices’ committed by the Inquisition in Spain, and the French troops in the peninsula were praised as ‘heroes of humanity’, who ‘had just destroyed this horrible sacrilege in Spain’.Footnote 33 The Gazette de France reaffirmed this interpretation, as it described the conquest of Mexico as an event comparable to ‘the prodigies we are currently witnessing’, establishing a parallelism between the sixteenth-century Spanish imperialism and the ongoing French military campaign abroad.Footnote 34

The connection between the narrative of Fernand Cortez and its context indicates the opportunism of political authorities and artistic agents.Footnote 35 Conceived in the summer of 1808 and set to music over the following months, Fernand Cortez benefited from imperial support, as evidenced by correspondence between Opéra director Louis-Benoît Picard (1769–1828) and Imperial Theatres superintendent Auguste-Laurent de Rémusat (1762–1823). In expectation of significant financial gains,Footnote 36 no expense was spared on special effects, including 14 horses on stage by the Franconi brothers, regardless of their high financial demands.Footnote 37 Actually, an exceptional budget of 180,000 francs was approved – about a quarter of the Opéra’s annual state grant.Footnote 38 But political urgencies also favoured the production. The invasion of Spain in early 1808 was motivated by internal conflicts within the Spanish royal family, coupled with the monarchy’s inability to secure sustained and safe commercial routes with the colonies, faced with increasing British pressure – which also went against French interests in the Spanish America. Considered a key geopolitical piece for France, imperial authorities sought to turn Spain into a ‘vassal monarchy’, one that would place the country within their sphere of influence.Footnote 39 Nonetheless, the Spanish campaign soon proved to be harsher than expected, as French troops and the new King Joseph I (1768–1844), Napoleon’s brother, faced a fierce and continuous internal opposition. The situation was further complicated in April 1809 by the opening of a new military front on the continent against the Fifth Coalition. Therefore, as Maximilien Novak has stressed, control over the flow of information, particularly concerning military interests, gained significant importance for national cohesion.Footnote 40 If managing public opinion was crucial for consolidating the legitimacy of imperial power within France, such control also extended to the Opéra, an institution Napoleon considered key in shaping the public image of the regime. Censorship, widespread in the press and cultural institutions, was systematically applied to the Opéra’s repertoire, with particular preferences for certain artists and composers.Footnote 41

Arguably, the selection of artists for Fernand Cortez did not appear to be coincidental. According to David Chaillou, Esménard is primarily remembered for his role as a theatre censor from 1806 until his death in 1811, although his political involvement was more complex in previous years. He defended the royalist cause during the Revolution, as evidenced by his connection to the future King Louis XVIII and his imprisonment after the Coup of 18 Fructidor (1797). Despite this, he ultimately rose to prominence during the Consulate (1800–1804). Connected to the emperor, he obtained public recognition in the following years, and entered the Académie Française in 1810.Footnote 42 His colleague, the military officer and writer Jouy, was better known for being a political chameleon. After being posted to French Guiana and the East Indies before the Revolution, he was persecuted during the Terror. His literary career as a writer, playwright and librettist blossomed at the end of the eighteenth century. He then supported Napoleon’s rise to power and was appointed censor of the Gazette de France.Footnote 43 A friend of Rémusat, Jouy achieved great success alongside Spontini with La Vestale (1807), one of the most performed operas during the imperial era and the first half of the nineteenth century, which brought both of them recognition and financial reward from the emperor.Footnote 44 Spontini’s career was also tied to the empire. Since his arrival in Paris in 1803, he integrated into bourgeois circles and became close to Sébastien Erard (1752–1831), an influential and renowned piano maker, marrying his niece, Céleste (born 1790), in 1811. He was also familiar with Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais (1763–1814), who appointed him as her personal chamber composer.Footnote 45 In gratitude, he, along with Jouy, wrote a small vaudeville which celebrated the French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz and praised the emperor.Footnote 46 Actually, the association proved remarkably beneficial for Spontini. Amid growing xenophobic criticism against foreign musicians in Paris, the empress supported the premiere of La Vestale,Footnote 47 which Spontini later dedicated to her.Footnote 48 By 1808–1809, the three authors of Fernand Cortez were thus clearly on the rise within the artistic system of the empire.

As a matter of fact, neither they nor the opera’s plot seemed to raise any concerns for the censors. According to the censorship report, it was believed that, if the authors’ instructions were followed, the opera would achieve unprecedented success. Furthermore, the jury considered ‘superfluous’ to examine the opera in detail.Footnote 49 That confidence may also have stemmed from the fame Esménard had achieved few years earlier, as he wrote the libretto for Le triomphe de Trajan, one of the most successful operas during the empire.Footnote 50 Premiered in 1807, the opera depicted the Roman emperor Trajan (53–117) and his entry into Rome following his military triumph in Dacia; a representation that symbolically alluded to the French victory over the Fourth Coalition in 1807 and Napoleon’s subsequent return to Paris.Footnote 51 Fernand Cortez articulated a similar narrative by glorifying a leader who confronted a distant and regressive territory with the purpose of liberating and claiming it; as Cortez declares in Act 1, ‘America belongs to those who know how to guide it’.Footnote 52 According to Esménard and Jouy, the opera portrayed a historical episode that ‘inspires the greatest amazement and admiration, and which brilliantly demonstrates what courage, perseverance, and the unyielding will of a great man can achieve’.Footnote 53 In sum, considering the opera’s thematic content and historical context, alongside the alignment of its creators with the imperial regime, Fernand Cortez in 1809 was intimately connected to the figure of Napoleon and his expansionist ambitions.

Nevertheless, as noted by Andries, Fernand Cortez was affected by a ‘problem of historical contingency’.Footnote 54 Conceived for a specific political moment, the opera – if contemporary press is to be credited – could prove effective in fulfilling the political objectives envisioned by its promoters. Transposed into a different political climate, however, the nexus between the opera and its instrumentalization exposed vulnerabilities. Put differently, the Fernand Cortez of 1809 risked becoming counterproductive if the political framework shifted unfavourably. By 1812, as the war in Spain turned against France,Footnote 55 the portrayal of Cortez and the sixteenth-century Spanish conquistadors as benevolent, civilizing liberators came increasingly to appear contradictory.Footnote 56 Actually, multiple scholarly studies agree that this disjunction was the principal factor in its removal from the repertoire in 1812.Footnote 57 Additional explanations, including unexpected incidents with the troupe and musical misinterpretations, have also been mentioned as potential factors in the decline of Fernand Cortez.Footnote 58 However, there are scarcely any studies so far that have analysed the opera’s box office evolution, not even as supplementary evidence to the recurring political argument explaining the decline of Fernand Cortez.

It is necessary to revisit again Papillon de la Ferté’s report from February 1816, since, as noted previously, the director of the Opéra did not invoke political arguments to advise against the revival of Fernand Cortez – his objections being exclusively logistical and economic in nature. The opera demanded a complex coordination between multiple operatic agents, from singers to decorators, choreographers and costume designers.Footnote 59 But these difficulties were also coupled with outstanding financial requirements – further exacerbated by inconsistent commercial performance. A quantitative analysis, considering both the number of performances and relative financial outcomes, offers a nuanced perspective on Fernand Cortez’s presence at the Opéra, as well as its success in terms of programming and profitability.

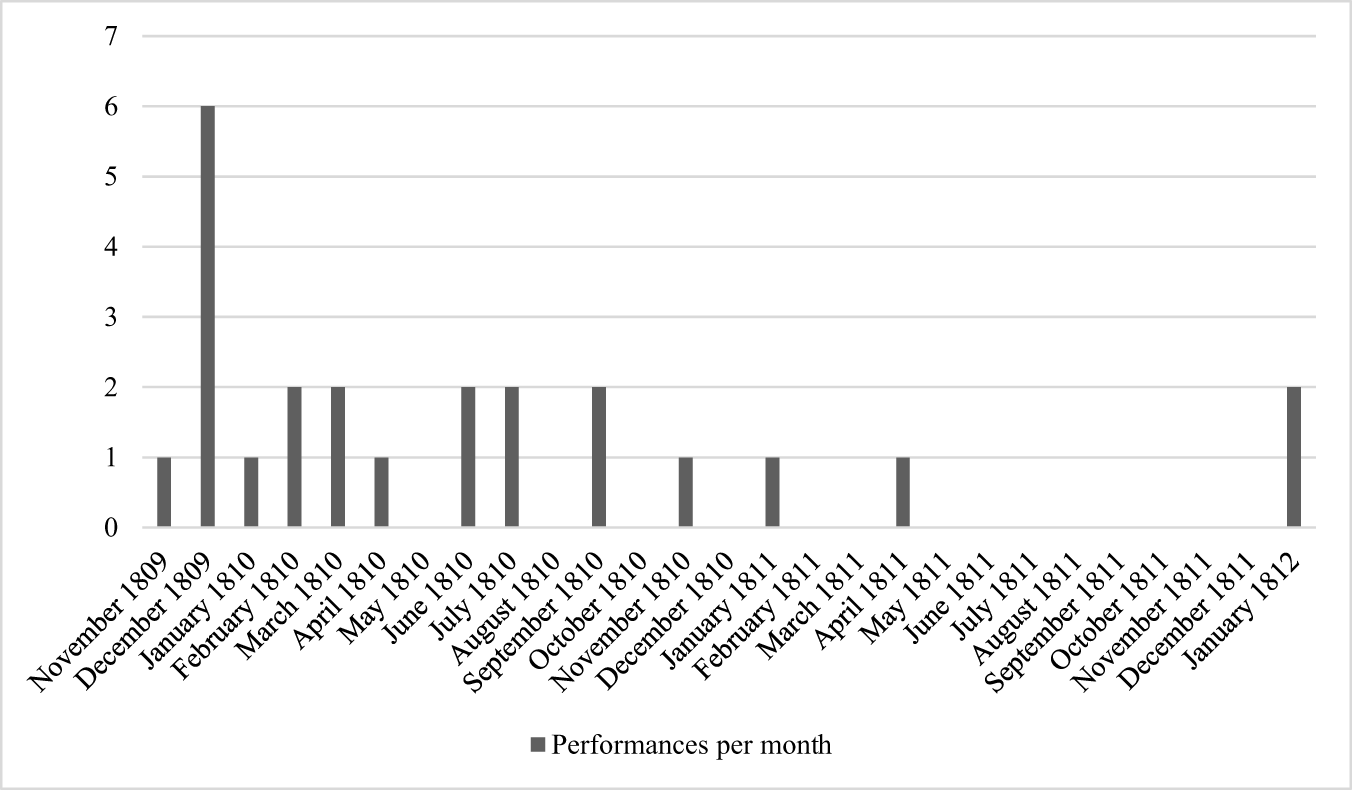

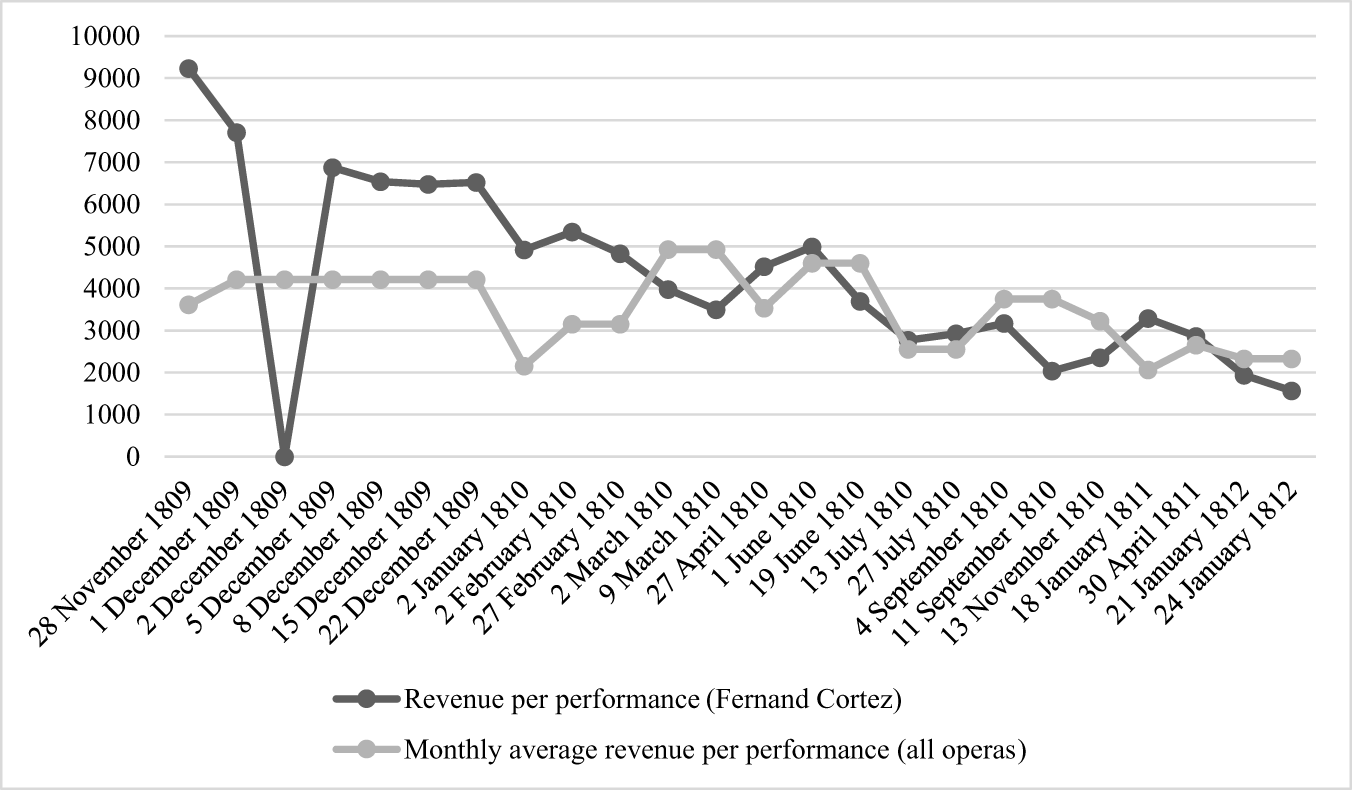

The total number of performances and the revenue data between 28 November 1809 and 24 January 1812 (the first and last performances dates) showed an irregular trend (see Figures 1 and 2). The evolution was erratic, with an initial three-month period (November 1809 to February 1810) accounting for nearly half of the performances and generating the highest revenues, consistently surpassing the average income per opera. Nonetheless, a downward trajectory became later apparent, which, despite occasional rebounds, characterized the subsequent evolution of Fernand Cortez. By March 1810, revenues fell below the average and, although they stabilized and aligned with the customary levels in the following months, there was no sustained indication of recovery. Actually, from April 1810 onward, performances became more sporadic, with no more than two shows per month. Even though this can also be explained by the absence of certain artists during this period,Footnote 60 it must be noted that revenues, at best, only slightly exceeded the average – while the 11 September 1810 performance yielded the poorest financial balance in the entire run. The years 1811 and 1812 confirmed this irregularity. In fact, it could be said that the trend worsened, with scarcely four performances in two years. Although revenue improved in 1811, a year later Fernand Cortez recorded its lowest revenue figures.

Figure 1. Number of performances of Fernand Cortez at the Opéra per month between 1809 and 1812 (Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF), Archives de l’Opéra, Journal de l’Opéra, 1809–1812).

Figure 2. Financial progress of Fernand Cortez (1809–1812) in French francs, showing revenue from each performance compared with the average income per staging for all operas running at the time. The third performance was free of charge. (Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Archives de l’Opéra, Journal de l’Opéra, November 1809–January 1812).

Papillon de la Ferté himself did not overlook this fact in his report. As he informed the Count of Pradel, the suspension of Fernand Cortez did not occur in January 1812 but the previous year, after the twenty-second performance, in April 1811. The last two performances, in January 1812, were held ‘after the pressing solicitations of the author, with great difficulty, and expenses’,Footnote 61 resulting in a ‘very costly outcome for the administration’.Footnote 62 He was well aware of the opera’s financial progress, having enclosed in his report a detailed breakdown of total income – 102,008.07 francs – well short of the 180,000 francs spent on its production.Footnote 63 Ironically, he even came to ‘acknowledge the wisdom of the former administration’ for its decision to withdraw the opera.Footnote 64

When examined together with the existing literature, it can be argued that economic considerations constituted a pivotal factor in Fernand Cortez’s removal in 1812. It might be difficult to prioritize one factor over another, particularly as the opera’s thematic pertinence waned in tandem with the empire’s political decline. Nonetheless, a close examination of performance and financial data, alongside Papillon de la Ferté’s letters, reveals a complexity that adds a further analytical dimension to the existing bibliography, indicating a productive and reception framework marked not only by artistic concerns, but also by administrative rationality.Footnote 65 Similarly, the analysis of economic aspects also brings to light another ambivalence of Fernand Cortez. The negative balance of Fernand Cortez contrasts with the benefits that the opera brought to its authors. According to the theatre’s accounting, Esménard and Jouy earned around 400 francs per performance in copyright fees.Footnote 66 Additionally, Spontini enjoyed a period of artistic and professional success after the premiere. In September 1810, he was appointed musical director of the Théâtre-Italien, a lucrative position in one of the most prestigious theatres in Paris.Footnote 67 And shortly after, La Vestale was nominated by the Institut de France to receive the Prix Décennal for the best opera – a decision not without controversy, to the point that it was eventually not granted, as will be discussed later.Footnote 68 Interestingly, Fernand Cortez turned out to be more beneficial for Esménard, Jouy and Spontini than for the institutions that promoted it. This divergent capitalization of Fernand Cortez points to the existence of distinct interests surrounding the opera, alongside a degree of opportunism in the appropriation and portrayal of Spanish history by both musical and political actors – albeit with differing intentions and outcomes.

Adaptive Narratives and Loyalties (1812–1816)

Engagement with Spanish history extended beyond the colonial period, with the Middle Ages also drawing French literary and musical interest. This was partly due to alleged parallels between the past Muslim–Christian conflicts in Spain and contemporary political tensions in France. As discussed in the previous section, the connection between historical context and dramatic content continued to be evident in some operas that premiered in the following years. For instance, operas like Les Abencérages, ou L’étendard de Grenade (1813) by the Italian Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842), and with a libretto by Jouy himself, were inherently associated with the imperial agenda.Footnote 69 In fact, Jouy’s libretto, initially accepted in 1811, had to be modified one year later so that it would have ‘no allusion to current events in Spain’.Footnote 70 During both the First Empire and the Restoration, operatic repertoire largely depended on extra-theatrical events, although history remained a symbolic battleground for political representation. In 1814, the collapse of the empire disrupted longstanding loyalties and expanded the scope for manoeuvre, forcing many artists to reposition themselves within a new political order; as was common during the Revolutionary period, the so-called girouettes were very frequent.Footnote 71 Jouy’s and Spontini’s actions between 1812 and 1816 (Esménard having died in 1811) offer valuable insights into the interests that influenced their creative work. Significantly, they also shed light on how personal agendas, along with the institutional priorities, affected the representation of Spanish history.

In the final years of the empire, Jouy remained an active figure. His plays continued to be performed, he premiered Les Abencérages and, writing under the pseudonym L’Hermite de la Chaussée-d’Antin, he regularly contributed articles on Parisian daily life to the Gazette de France.Footnote 72 Conversely, the decline of Fernand Cortez marked the beginning of a professional crisis for Spontini.Footnote 73 His management at the Théâtre-Italien was turbulent: clashes with members of the troupe and with the administrator Dominique-François Gobert, who resigned, left him alone in charge of the institution. In July 1812, overwhelmed by the administration of the theatre, he was dismissed and replaced by his rival, the Italian composer Ferdinando Paër (1771–1839).Footnote 74 Even though he did not disappear from Parisian musical life (as La Vestale was still successful, and he retained his position on the musical jury of the Opéra), his attitude and movements immediately after Napoleon’s fall in April 1814 suggest that Spontini’s reputation and professional situation had been called into question.Footnote 75 His inclusion in the Dictionnaire des girouettes in 1815 is significant in this context. In his corresponding entry, the composer’s change of allegiance was underlined: he had moved from being associated with the former Empress Joséphine to paying homage to the Bourbon dynasty with the premiere of a new opera – Pélage.Footnote 76 Jouy was also singled out by the same satiric dictionary. Despite his privileged position in the literary circles of the empire, Jouy did not take long to celebrate the return of the monarchy in April 1814. Leaving the Gazette de France to work for the royalist Journal général de France can be seen as a sign of his adaptability.Footnote 77 His collaboration with Spontini in Pélage, which premiered in August of that same year, further supports this point, as the opera was described by both authors as their contribution to ‘the majestic celebration that all of France is preparing to celebrate’.Footnote 78

Like Fernand Cortez, Pélage drew a historically motivated parallel between past and present, though with different intentions. After the restoration of the monarchy, several theatres in Paris premiered numerous pièces de circonstance that exalted the new sovereign. Moreover, there were public celebrations emphasizing the kinship of Louis XVIII with Henry IV (1553–1610), the founder of the Bourbon dynasty in France, and with Louis XIV (1638–1715), in order to reinforce the legitimacy of the monarchy by highlighting the idea of historical continuity after more than 20 years of republican and imperial interregnum.Footnote 79 These discourses linked the restoration of the monarchy with the restitution of peace, a return that brought comfort to a people exhausted by war and was understood as a kind of expiation of the revolutionary sins.Footnote 80 The imagination of Louis XVIII as a saviour, associated with religious virtues and classical mythological figures, almost baroque in style, permeated various visual discourses (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Emile Rouargue (illustrator) and Moret (engraver), Avénement de Louis XVIII au trône de France (1815), Musée Carnavalet, Paris, G.34327. Allegorical illustration celebrating the accession to the throne of Louis XVIII. The caption reads: ‘Minerva, goddess of wisdom, moved by the secret wishes of the unfortunate French people suffering under the warlike fury of a Usurper who had made himself their Master, guides Louis XVIII toward France, shielding him with her aegis. Afflicted France takes him by the hand and leads him to the throne of his ancestors. Religion, holding the Sacred Book of Tolerance, follows him. At this scene, Painting and Sculpture, Mothers of all the Arts, rise up once more and give thanks to Divine Providence for such a joyful Event. Children, representing the new generation, topple and mutilate the statue of Mars, the cruel god of war, which in turn reveals and allows to spread the benevolent branches of the Olive Tree, symbol of Peace. From all sides, the People express their joy and hope with the repeated cries of LONG LIVE THE KING… and Justice presides over this moving Painting’. Public Domain.

But alongside the references to Henry IV, the legitimacy of Louis XVIII as the new king was also justified by his association with other heroic figures. In this sense, the connection with Pelayo (died 737), along with the myth of the Spanish Reconquista, served as legitimizing tools in Bourbon propaganda during the 1814 celebrations. It is no coincidence that the opera, originally titled Pélage, ou le Retour d’un bon Roi, was written and composed swiftly: started in April 1814, authorized by censorship in May, and premiered on 23 August, two weeks before the festivities to celebrate the king’s reception at the Paris City Hall on 29 August. The evocation of the historical figure of Pelayo served as a political argument. Historiographical tradition regards Pelayo as the first King of Asturias and a figure of resistance who, from Covadonga (a mountainous sanctuary in the present-day Picos de Europa National Park, in northern Spain), began in the eighth century what came to be known as the Reconquista against the Muslims. Both he and the Reconquista would go on to serve as foundational myths for Spanish nationalist discourse throughout the nineteenth century, but they also had repercussions beyond Spain.Footnote 81 In early nineteenth-century France, for instance, his legend catalysed feelings of loyalty to the monarchy by symbolizing the restoration of a sacred political order through the recovery or liberation of a territory.Footnote 82

The opera’s plot, set in Asturias in the eighth century, depicted a fictional episode in which Pélage (the operatic representation of the historical Pelayo), after 20 years in Covadonga, gathered his people and entered the Asturian capital Oviedo after defeating a Muslim army. In Act 1, set in the rocky landscape where Covadonga is located, Pélage is presented as the legitimate king after the death of his brother Rodrigue during the Battle of Guadalete (711), due to the treason committed by a fellow Christian – the Count Julien. Accompanied by Rodrigue’s daughter, Favila, Pélage is convinced that, despite the precariousness of his situation while in hiding, the union of neighbouring Christian lords and kings will lead them to victory against the Moors. The arrival of Alphonse’s troops – Alphonse being Favila’s husband – brings joy to the Asturians: the soldiers have defeated the Moors and opened the road to Oviedo for Pélage. The celebration fills the entire Act 2, set in the Asturian capital. The people rejoice in the peace and hope Pélage has brought them, and he is praised as a king they had long desired. The opera concludes with a divertissement allégorique in which multiple figures representing the Nation, Hope, and Glory defeat Madness and the Furies (Discord, Hatred, and Vengeance) with the help of Abundance and the Arts.

Pélage, along with its protagonist and the Reconquista, seemed to function as a historical mirror, providing an appropriate framework to explain recent events in France by narrating ‘the story of the present time under the veil of the past’.Footnote 83 The press claimed that the plot offered a ‘multitude of historical comparisons’ between the restoration of the Spanish monarchy in the past and the French monarchy in the present, with the return of the Bourbon dynasty.Footnote 84 For example, the analogy between the historical Pelayo and Louis XVIII was established by the libretto, based on similar genealogy and historical circumstances; not only was Pélage described as the victim of an ‘usurper’, but also as the ‘heir of an immortal name’.Footnote 85 He was perceived as the ‘successor of a brother, victim of the most execrable crime’, and who had been ‘forced to leave a land profaned by crime’, in clear symbolic allusion to the guillotined Louis XVI and the subsequent exile of his brother, Louis XVIII.Footnote 86 The parallelisms also encompassed the historical contribution of both monarchs. As the libretto’s preamble stated, the historical Pelayo had been a ‘worthy prince’ who, ‘through his virtues, his greatness of soul, and his courage’, had managed to maintain the hope of ‘liberating his country and restoring the Christian throne, to which his birth and the love of an impatient people called him’.Footnote 87 The operatic representation reflected the historiographic significance and conveyed it through the character Pélage, symbolising Louis XVIII as a king who pacified the country and promised a future of hope.Footnote 88 In Act 2, while Pélage and Favila are on their way to Oviedo, the soldiers sing:

O king! Our dearest hope,

source of love and tears;

The gift of your presence

is no longer a dream of our hearts.

Even in the heart of our fears

a day so sweet now dawns;

No more war, no more tears:

Pélage stands with us.Footnote 89

The press insisted on this idea. ‘Peace, this daughter of heaven’, read a review, ‘has descended upon the earth on the same day that Louis the Desired has returned to his states’.Footnote 90 Pélage thus became part of the Restoration’s imaginary, portraying an image of the monarchy sensitive to the recent sufferings of the people and whose return was symbolized as the arrival of a future of peace and order.Footnote 91

Although the opera only had four performances and poor box-office results (only one show exceeded the monthly average income per performance),Footnote 92 it proved symbolically useful. Despite the fact that the censorship report had acknowledged that the dramatic action was ‘almost non-existent’, the jury argued that, due to the values it portrayed, the opera deserved to be staged at the Opéra as a ‘public celebration’ – even recommending that the king attend the performances.Footnote 93 Louis XVIII did not follow the advice; his nephew Charles Ferdinand (1778–1820), the Duke of Berry, was the most prominent member of the royal family to be present at the premiere. Nonetheless, the king accepted the dedication of Pélage from Spontini,Footnote 94 whom he received in an audience to thank for his opera.Footnote 95 In fact, Pélage was strategically used by Jouy and Spontini to secure the support of the royal family and the press, who applauded the authors for their ‘great services’.Footnote 96 In January 1815, Jouy entered the Académie Française.Footnote 97 Meanwhile, Spontini sought to restore his professional position at the Théâtre-Italien, trying to recover the prestige he had enjoyed during the empire. To this end, as will be discussed below, Spontini moved to reclaim the directorship of the theatre and reposition himself within the monarchy’s musical establishment shortly after the Treaty of Fontainebleau in April 1814, where Napoleon was obliged to resign.

As Castellani points out, in April 1814, Ferdinando Paër was still directing the Théâtre-Italien, following the polemical departure of Spontini in September 1812.Footnote 98 However, Paër’s position became increasingly precarious due to his ties to the empire (he had been appointed court composer to Napoleon in 1807) and the theatre’s economic difficulties resulting from the political instability after the emperor’s fall.Footnote 99 Taking advantage of the situation, Spontini petitioned the Duke of Berry for his former position, as well as for the role of director of the king’s private music. Spontini argued that his previous musical trajectory and experience at the Théâtre-Italien made him a suitable candidate, yet his argument obscured the conflicts of his management at the theatre, as well as the dispute over the Prix Décennaux of 1810.

As noted several pages earlier, Spontini’s La Vestale was nominated in the category of best opera, on the proposal of the Institut de France. This decision, however, ran counter to Napoleon’s preference for Ossian, ou les Bardes (1804) by Jean-François Lesueur (1760–1837), as was the case in other categories where the artistic judgements of the academicians clashed with the emperor’s determination to subordinate the arts to his regime.Footnote 100 Eventually, the prizes were never awarded, but Spontini made no mention of this. On the contrary, he stated that the award was in fact ‘granted’.Footnote 101 In fact, he reiterated these points in no less than four letters, all of them probably written in August 1814, while Pélage was about to be premiered or was already on the bill.Footnote 102 Yet in these messages – practically identical in style and content – he not only repeated the justifications mentioned above, but also introduced new ones. For instance, in the last and longest letter, addressed now to Pierre-Louis de Blacas (1771–1839), the Duke of Blacas and Minister of the King’s Household, he emphasized his connection to France, mentioning his marriage to Céleste Erard, a member of ‘a very respectable French family’.Footnote 103 But his argument went further still. He accused Paër of having obtained his position illegitimately and of being a disastrous manager. And he even went so far as to call him a political enemy, pointing to his involvement in L’Oriflamme, a pièce de circonstance that premiered in February 1814 – a few weeks before Napoleon’s forced abdication. The opera, centred on the confrontation between the Saracens and the French in the Battle of Poitiers (732), symbolically evoked loyalty to the emperor before the imminent battle for Paris against the Sixth Coalition (1814).Footnote 104 In Spontini’s words, it was an opera composed to ‘raise the French, in the past months of February and March, against Louis XVIII’.Footnote 105 In contrast, Spontini presented himself as a defender of the monarchy, using a new argument in his letters: Pélage. He stated that his opera commemorated ‘the universal joy for the long-awaited return of the esteemed head of the august House of Bourbon’.Footnote 106 Pélage thus appeared to serve pragmatic ends. In Spontini’s argument, it became a political weapon against Paër, whom he sought to discredit in the eyes of the new regime, positioning himself as a more suitable and loyal candidate. By this time, Spontini was connected to several social and political figures loyal to Louis XVIII. His friendship with Louis-Marie-Céleste d’Aumont (1762–1831), the Duke of Aumont, and Louise de Montmorency (1763–1833), the Princess of Vaudémont, was eventually of particular value, as they supported his requests to Blacas. Perhaps this is why, in September 1814, shortly after the end of Pélage’s performances, Blacas consented to Spontini’s return to the Théâtre-Italien and granted him the position of director of the king’s private music. But to Spontini’s dismay, an administrative reform, Napoleon’s return, and the definitive appointment of soprano Angelica Catalani (1780–1849) as director in 1815 ultimately deprived him of the opportunity to hold the position.Footnote 107 However, the Théâtre-Italien affair underscores one of the practical uses that an opera like Pélage could have, despite its ‘lukewarm’ success.Footnote 108

Indeed, in November 1815, Spontini found himself once again compelled to petition the new minister, Pradel (who had replaced Blacas), for the position of royal dramatic composer, as well as his reinstatement to the musical jury of the Opéra. As usual, he invoked his artistic and familial reputation, reminding him that he was the composer of Pélage.Footnote 109 As a matter of fact, Spontini’s commitment during the Hundred Days (March–July 1815) also worked to his advantage. Unlike Jouy, who was marked by his sensitivity to the ‘shift in the political winds’,Footnote 110 Spontini did not side with the emperor when he escaped from Elba. The librettist once again changed his loyalty, returning to the Gazette de France and taking up the position of imperial commissioner at the Théâtre Feydeau. But the second Bourbon Restoration put Jouy in a more precarious position, as several of his plays were banned by the censors, pushing him closer to the liberal opposition.Footnote 111 Conversely, the composer remained committed to the monarchy. His friend, the Duke of Aumont interceded on his behalf, assuring Pradel that Spontini’s ‘attitude’ during the ‘interregnum’ had been ‘frank and loyal’.Footnote 112 Pradel consented finally to the request. Once the position was granted, Spontini used his new status to settle his finances, regain prominence in the musical scene and consolidate his prestige. For instance, he requested 6,000 francs to cover the expenses of Pélage (he had personally funded the printing of the score to present it to the king), as well as various fees owed to him from his work at court since 1814.Footnote 113 He also urged the Opéra administration to assign him new operas, including the opera-ballet Les Dieux rivaux (1816), which was composed to celebrate the marriage of the Duke of Berry.Footnote 114 And soon after, Spontini petitioned for the Légion d’honneur. Once more, he justified his request by emphasizing his connection to a respected French family, his loyalty to the monarchy during the interregnum when he had the ‘happy opportunity to demonstrate my full devotion to the Holy Cause of the King’ and recalling his artistic merits such as the unawarded Prix Décennal and the composition of Pélage – the petition included a copy of the score.Footnote 115

The use of Pélage as symbolic capital to rehabilitate a contested reputation reflects a musical culture – particularly in the realm of prestigious forms such as opera – that was deeply intertwined with institutions of power. Networks of influence were essential for obtaining commissions and appointments, as exemplified by the disputes for the directorship of the Théâtre-Italien. Spontini and Jouy’s adaptable rhetoric appears to have arisen less from ideological conviction than from the necessity of navigating an unstable political landscape. In this context, Spanish history reappeared as a symbolic battleground and a rhetorical scenario for adapting individual reputations to changing institutional demands. Both the authors and the monarchy saw in Pélage an opportunity to consolidate their respective positions, regardless of its commercial success.

Operatic Economies (1816–1817)

Ironically, none of the numerous letters Spontini addressed to the king’s ministers between 1816 and 1817 made any mention of his authorship of Fernand Cortez. The selective presentation of his achievements to the new monarchical administration – stressing his role in Pélage while omitting Fernand Cortez – may be interpreted as a cautious strategy vis-à-vis an unpredictable political arena, particularly given that his position as royal dramatic composer had not yet been secured. Shortly after his nomination, he approached the Count of Pradel to propose the revival of the opera. In response, Pradel wrote to Papillon de la Ferté, the director of the institution, asking him to prepare a report on the feasibility of the request.Footnote 116 As mentioned earlier in the introduction of this article, Papillon de la Ferté expressed little confidence in the proposal’s prospects, based on technical and economic considerations. His reports invite a reconsideration of the motivations behind Fernand Cortez’s withdrawal in 1812, which has traditionally been attributed to political reasons by historians. Additionally, there is a need to revise the transformation of Fernand Cortez’s plot in 1816, which impacted the representation of the Spanish conquest of Mexico. As will be explained below, although the 1817 libretto suggests a dramatic adaptation motivated by Jouy’s and Spontini’s opportunism in currying favour with the new regime, the political factor does not appear to have been decisive for the final approval of Fernand Cortez. Other, more prosaic elements must be taken into consideration.

Certainly, the budgetary factor seemed to take precedence in determining the opera’s feasibility. Papillon de la Ferté’s refusal was based on the technical reports from the chorus and ballet directors, but also on the recognition of the high costs that the operation would require. Actually, he set the total cost at more than 100,000 francs. Therefore, he assured Pradel that Fernand Cortez ‘would never remain in the repertoire’ and included a breakdown of the estimated expenses in his letter.Footnote 117 This budget, dated 11 October 1816, referred to a proposal based on the 1809 libretto, as it included details about the arrangement of the acts and the list of characters from the original Fernand Cortez. In other words, it seems that Spontini and Jouy had requested the opera’s revival without any changes. However, two weeks later, the composer and librettist put forward a new version with a different story and a series of suggestions to save money.

Regarding the plot, they proposed reversing the order of the first and second acts, and adapting or redistributing several scenes, as well as introducing a new character: Montézuma. The new storyline does not begin in the Spanish camp with the soldiers’ mutiny and the subsequent burning of the fleet (now shifted to Act 2); rather, it starts in the Mexica temple. Alvar and the Spanish soldiers are about to be executed, but Amazily convinces Montézuma to spare their lives. Her timely intervention already reveals the new dramatic weight the princess has acquired. She is presented as an intermediary between the Spaniards and the Aztecs, despite being disregarded as a traitor by Télasco and the High Priest. Even so, she succeeds in securing Montézuma’s consent to mediate with Cortez and thereby prevent a confrontation. In the following Act 2, which broadly follows the structure of former Act 1, Cortez quells the mutiny of his troops before Amazily and Télasco arrive to offer a truce. However, this does not prevent an ambitious Cortez from pursuing his plans; he orders the burning of the fleet and to march towards Tenochtitlán. Act 3, set in the vicinity of a mortuary temple in Tenochtitlán, reprises certain scenes from the 1809 Act 2 while introducing new ones that grant Montézuma a more prominent role. He is depicted as a respectable king who, before being conquered, releases the Spanish captives and is prepared to die and to see the city destroyed. Torn between her love for Cortez and loyalty to her people, Amazily intervenes to seek peace and convinces both leaders to lay down their arms. The opera concludes with the ‘general feast of both nations’ to celebrate ‘the union of the two Worlds’.Footnote 118

Economically, Jouy and Spontini recommended retouching ‘old decorations’, ‘washing and refreshing’ what was left of the original costumes from Fernand Cortez and reusing ‘all the Spanish costumes from the opera Pélage’, as well as ‘the American and Spanish outfits’ from similar operas, such as Les Abencérages. Furthermore, the proposal outlined the specific types of sets required for the new arrangement of the scenes, clearly identifying which could be reused from existing materials – largely from the original Acts 1 and 2 – and which would need to be newly created. This indicates that Spontini and Jouy were actively seeking to reduce production costs, in order to ensure that the overall budget would ‘not exceed’ the 15,000-franc limit previously set by Pradel.Footnote 119 In fact, their interest in reviving the opera extended to taking personal financial risks; just weeks later, they explicitly stated their willingness to ‘jointly’ cover any unexpected costs surpassing the agreed amount.Footnote 120 Although Pradel rejected the authors’ economic proposal – considering it ‘unacceptable’ for them to meddle in the internal affairs of the Opéra – he ultimately authorized the revival, pressed by the urgency of finalizing the 1817 repertoire and on the condition that the budget cap be respected.Footnote 121 Preparations for the new Fernand Cortez began immediately afterward,Footnote 122 and the opera returned to the stage on 28 May 1817, though not without exceeding the agreed expenditure ceiling. Adjustments to sets and costumes amounted to 22,865.95 francs,Footnote 123 not including the substantial fees paid once again to the Franconi brothers, much to the irritation of Papillon de la Ferté.Footnote 124

However, the 1817 version of the opera also appeared to be associated with political references. The libretto underwent a significant transformation, particularly in the dramatic importance of certain characters and the political message of the opera (a shift already observed in the intermediate version of Fernand Cortez, allegedly written in 1814–15).Footnote 125 On the one hand, Princess Amazily was given more prominence; according to the authors, this was to better align her role with the ‘habits of the theatre’, even at the cost of sacrificing the ‘historical truth’ that had been claimed in the first libretto.Footnote 126 Her role as an intermediary between the two peoples was reinforced and she gained more agency with her pacifying initiative. In fact, the censorship viewed this positively. As the report acknowledged, the general plot had not undergone many changes, except for a new sequence of scenes that helped ‘integrate Mexican character Amazily into the main action’ and ‘increase the interest’ of the opera.Footnote 127 On the other hand, the incorporation of Montézuma, which the censors neither objected to nor commented on, rebalanced the opera’s political dimension. With Montézuma on stage, not only was the original prominence of Cortez reduced,Footnote 128 but Fernand Cortez also moved closer to a courtly model, typical of baroque opera, which praised the qualities of a virtuous monarch.Footnote 129 Specifically, Montézuma was portrayed as a wise and magnanimous king whose willingness to sacrifice himself for his people took on a paternal and exemplary appearance. ‘It is time to be a king/under the ruins of the throne/to Montézuma, ready to perish/there remains nothing but the example he gives/the example of dying well’, sang the Mexica King upon realizing the Spanish victory.Footnote 130 This attitude was similarly appreciated and acknowledged by his rival, who with equal benevolence, recognized it to seal peace: ‘Montézuma, forgive me my glory/it is only your friendship that I wish to conquer/The most beautiful price of my victory/is the peace that I come to offer you’.Footnote 131 The echoes of conformity and pacification, present in restorationist discourse, also resonated in the new version of the opera.

According to the press, this may have been further facilitated by the omission of certain verses from the 1809 libretto that had previously glorified Napoleon. In the first libretto, Act 1 ended with a choral scene featuring the Spanish soldiers and Cortez, which exalted the conquistador. The press attributed those verses to the late Esménard, and noticed that the final line (‘Et l’univers appartient aux héros’) was modified in the new libretto. In the 1817 version, this scene – now moved to the end of Act 2 – also celebrated Cortez, but without emphasizing his universal heroism (Figure 4). Critics praised Jouy for having had ‘a memory fortunate enough and a conscience delicate enough’ to ‘make disappear’ the references to ‘a certain idol not too demanding regarding the quality of the incense burned before him’.Footnote 132

Figure 4. Fernand Cortez 1809 and 1817 libretti comparison. (Source: Etienne de Jouy and Joseph-Alphonse Esménard, Fernand Cortez ou La conquête du Méxique. Opéra en trois actes (Paris: Imbault, 1809), 19; Etienne de Jouy, Fernand Cortez ou La conquête du Méxique (Paris: Roullet, 1817), 40).

Amazily’s new prominence and the inclusion of Montézuma also reinforced the perceived improvement in the artistic quality of the storyline. In fact, critics believed that the dramatic interest of the original production would have been greater had the acts been arranged as in the new version, and had the ‘powerful King of Mexico, this proud Montézuma, so great in his misfortune, so moving in his resignation, and who knew, even in his downfall, how to earn the respect of the Spaniards’, been part of the first cast.Footnote 133 The narrative optimization and artistic enhancement of Fernand Cortez thus paralleled a perception of Montézuma – or more broadly, the figure of the monarch – as fitting for the new political era.

A few special performances of Fernand Cortez in the summer of 1817 seemed to confirm the opera’s renewed significance and usefulness by sealing its association with the monarchy. The celebration of the feast of Saint Louis of France on 25 August, in honour of the canonized King Louis IX (1214–1270), was marked by a free performance of Fernand Cortez at the Opéra.Footnote 134 Several days later, on 5 September, the entire royal family attended another performance, which turned out to be one of the most profitable evenings of Fernand Cortez at the Opéra – 9,881.40 francs in revenue.Footnote 135 The performance was interrupted several times by enthusiastic applause and cheers for the king and the House of Bourbon, and at the end, the orchestra and singers performed several monarchical anthems, including Vive Henri IV.Footnote 136 Present in the audience, Spontini was received by the king, who personally congratulated him.Footnote 137

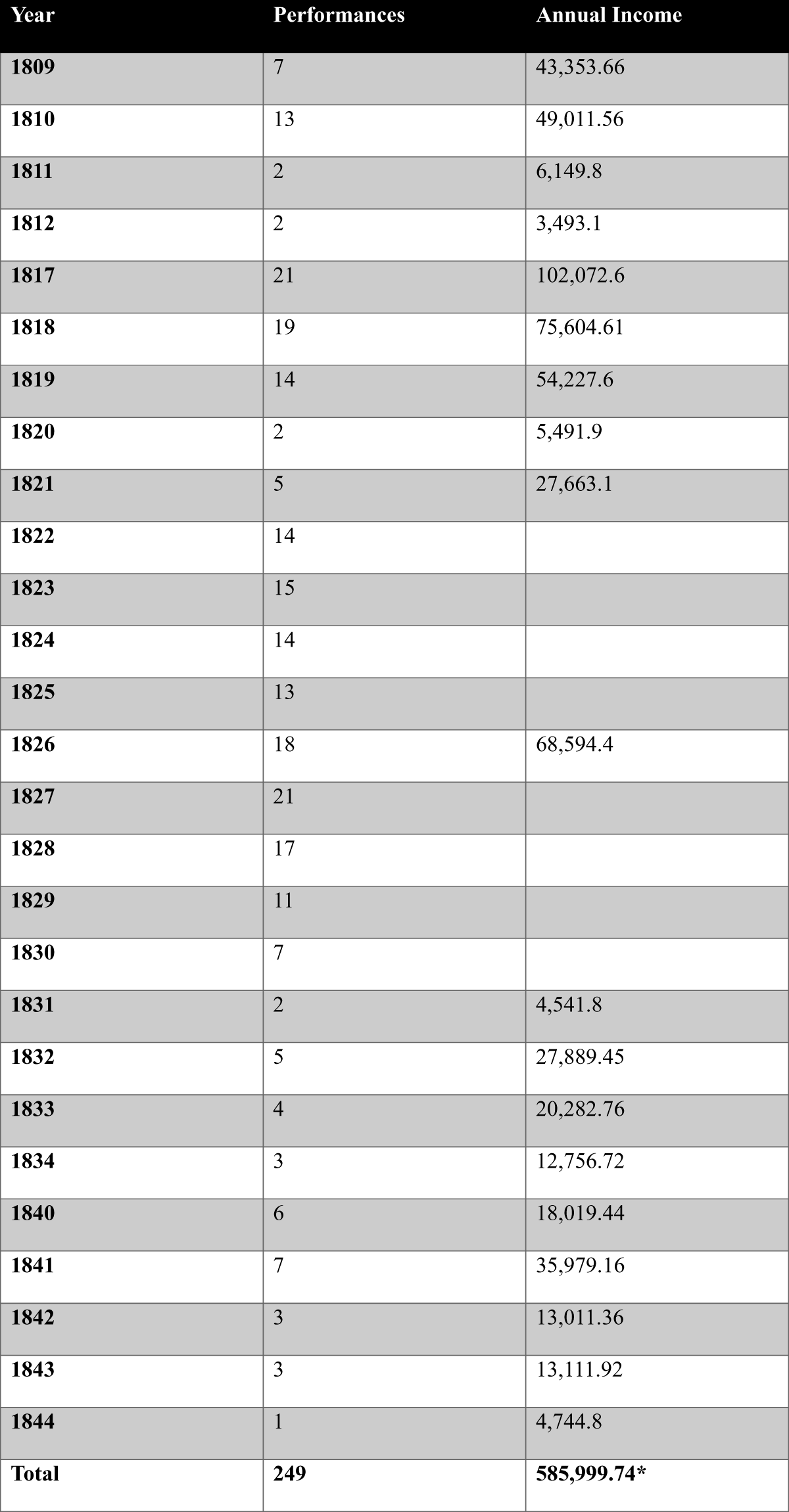

But the revival also marked a new economic chapter for the opera. In retrospect, and judging by its continued presence in the repertoire over the following years, Fernand Cortez became a regular fixture. Despite some fluctuations in popularity, it was one of the most frequently performed operas during the Bourbon Restoration, particularly throughout the 1820s (Figure 5). It remained in continuous rotation from 1817 to 1834 and, after a six-year hiatus, returned to the stage until 1844. In total, Fernand Cortez was performed 249 times at the Opéra. Interestingly, only about 10 per cent of those performances (24 out of 249) took place during the imperial period. One could say that, despite his initial reservations and the eventual cost overruns, Papillon de la Ferté may have felt reassured in approving the revival.

Figure 5. Fernand Cortez’s annual performances and box-office income between 1809 and 1844, in French francs. (*): since box-office data from 1822 to 1830 (except 1826) is unavailable, total income is based on 137 performances. (Source: BnF, Archives de l’Opéra de Paris, Journal de l’Opéra, 1809–1844).

Epilogue

After the revival of Fernand Cortez, Spontini enjoyed a brief period of success and recognition. In 1818, he was finally named a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, and he also obtained French citizenship. But his new opera, Olympie (1819), was a failure.Footnote 138 In 1820, he decided to leave Paris and settle in Berlin under the patronage of King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia (1770–1840).Footnote 139 He took on the role of Generalmusikdirektor at the Royal Opera, where he once again adapted Fernand Cortez in 1824 and 1832 according to local dramaturgical and political conventions.Footnote 140 Meanwhile, Jouy remained in Paris, where he wrote the librettos for Gioachino Rossini’s (1792–1868) well-known operas Moïse et Pharaon (1827) and Guillaume Tell (1829). A member of the liberal opposition, he supported Louis-Philippe of Orléans (1773–1850) during the July Revolution of 1830.Footnote 141

The trajectory of Fernand Cortez, with its transformations and multiple uses, reflects the presence of a complex web of institutional and individual agendas that shaped its creation and development. On the one hand, the political references confirm the interest of authorities in producing or performing the opera. Its imperialist use in 1809 seems beyond doubt, and likewise, the successful 1817 revival provided the monarchy with an opportunity to exploit the opera to bolster the legitimacy of Louis XVIII. On the other, the pursuit of public recognition and artistic-political survival – especially in the case of Jouy and Spontini – demonstrates how Fernand Cortez was also influenced by personal interests. Together with Pélage, Fernand Cortez reveals that opera could serve as a practical mechanism for readjusting one’s reputation, thereby securing recognition and professional standing. Symbolic and material interests, including economic rewards, were thus a priority for artists, as shown by Jouy’s manoeuvres and Spontini’s courtly intrigues. But authorities did also worry about monetary issues. In fact, as this article has stressed, there was a tension between political interests and economic management. It was a delicate balance that, depending on the context, tipped in favour of one priority or the other, and ultimately determined the fate of Fernand Cortez at the Opéra. One might assume that Jouy and Spontini sought to ingratiate themselves with the monarchy in 1817, with Pélage serving as earlier evidence of such political adaptability. However, internal reports between the Count of Pradel and Papillon de la Ferté also unearth a pragmatic and dispassionate stance: the latter’s anxieties about logistical and financial matters imply that the withdrawal of Fernand Cortez in 1812 and its revival in 1817 were decided on the basis of commercial performance and budgetary constraints. Between 1809 and 1817, Fernand Cortez’s symbolic capital was never neglected either by the empire or the monarchy as a tool for legitimation, but only insofar as there was willingness to fund it or if the investment was compatible with financial possibilities – or ideally profitable.

These dynamics also unfolded in a politically unstable context, in which artists such as Jouy and Spontini, without forgetting Esménard, turned to history to make sense of the present. As this investigation contends, representations of Spanish history functioned as a rhetorical device and displaced metaphor that encoded the ambitions and necessities of the French Empire, as well as the Bourbon monarchy’s urgency to reestablish itself after nearly two decades out of power. In 1809, a manipulated narrative of the Spanish conquest of Mexico served as symbolic justification for the French invasion of Spain. Five years later, in Pélage, the reimagining of the myth of Pelayo and the Reconquista drew a historicist parallel that reframed recent events, restoring both the king’s image as an exemplary political figure and the monarchy’s prestige as a legitimate form of government. And in 1817, Fernand Cortez was restaged and adjusted to a revised historical narrative reflective of the new political context. The glorification of the king through a favourable portrayal of the character Montézuma went hand-in-hand with a historical exposition of the Spanish conquest of Mexico reframed to conform to the official discourse of peace and reconciliation. In short, these historical representations can be seen as echo chamber of the tensions that provoked a crisis of legitimacy in France and which, in their various processes of reconfiguring authority, rhetorically incorporated Spanish history into their narratives of power.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was made possible by a postdoctoral fellowship granted by Hezkuntza, Hizkuntza Politika eta Kultura Saila, Eusko Jaurlaritza (POS-2022-1-0003). It contributes to the project ‘Desimperialización y procesos de construcción nacional en el Atlántico hispano’ of the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments.