Introduction

Interest groups spend a lot of moneyFootnote 1 on outside lobbying, such as media campaigns, to influence decision-makers indirectly by building public pressure.Footnote 2 Interest groups also regularly make efforts to overcome collective action problemsFootnote 3 to join other groups and organize broad coalitions to publicly advocate for specific policies.Footnote 4 However, it is unclear to what extent these costly public lobbying strategies can change public opinion. This is an important question because outside lobbying could have either positive or negative effects on politics and society. On the one hand, outside lobbying could provide difficult to access policy knowledge, and thus improve the quality of information that citizens receive about policy issues.Footnote 5 On the other hand, if interest groups are able to systematically influence public opinion in their favor, this might lead to biased policy outcomes that only reflect narrow and well-resourced interests.Footnote 6

Yet, the existing experimental work on the topic comes to mixed conclusions regarding the effect of outside lobbying on public opinion. While some studies find a positive effect of interest group messages on individual attitudes,Footnote 7 others find mostly null effects,Footnote 8 or mixed results, depending on the policy context studied.Footnote 9 Moreover, it remains unclear why some studies find positive effects, and which precise mechanisms drive these results. Lastly, few studies investigate the effect of outside lobbying strategies across different geographical and cultural contexts.

We integrate existing approaches into one factorial design within a well-powered cross-country survey experiment. We argue that outside lobbying strategies are effective instruments to sway public opinion, but that the effect is conditional on the strength of the message, the messenger and the policy type. First, we posit that outside lobbying is more effective when interest groups use more costly media strategies to signal to citizens. Second, we suggest that outside lobbying has larger effects when a coalition of diverse interest groups comes together to conduct information campaigns or launch public protests instead of just a single interest group.

Finally, we expect that the policy type matters. More specifically, we suggest that outside lobbying is more successful in influencing public opinion on subsidy policies than on taxation policies. While subsidies are a distributive policy which yields a direct and certain benefit to citizens without necessarily being associated with costs, we expect less support of higher taxation which imposes direct and certain costs on citizens, with more uncertainty about the potential benefits.

We conduct a preregistered cross-country survey experiment among 9,000 respondents in Germany and the United Kingdom. More specifically, we administered a 3 by 5 factorial design embedded in nationally representative surveys in which we randomly vary the interest group messenger (single interest group vs. interest group coalition) and the medium of public messages (video, flyer, information) in support of two widely-discussed policies tackling climate change: electric-vehicle subsidies or carbon taxation (subsidy vs. taxation policy).

Our results show that outside lobbying can have a short-term effect on public opinion. However, the effects are not different for generic policy messages without interest groups, and there are no significant differences between messages involving single groups or broad, cross-cutting interest group coalitions. Moreover, while more costly media usage like promotional videos increase policy support among respondents, they do so only for electric-vehicle subsidies. In contrast, we find no effect for support for carbon taxation, suggesting that outside messages are more effective for distributional policies with clear private benefits, but not for redistributive policies with private costs for respondents.

To test mechanisms linking outside lobbying and public opinion, we use an intermediate outcome test (IOT).Footnote 10 We find tentative evidence that outside lobbying affects respondent preferences primarily through signaling higher public support to respondents, with effects being more pronounced for perceived public support in the general population than in respondents’ immediate environments. We find close to no evidence for an effect of outside strategies on making policies more salient in respondent’s minds.

Our results have implications for the effectiveness of interest group’s public endorsement strategies. First, the fact that we find no difference between media usage and types of coalitions is at odds with the amounts of money groups spend on outside strategiesFootnote 11 and on organizing policy coalitions.Footnote 12 Hence, it might indicate that outside campaigns are not the most efficient use of resources for interest groups in all circumstances and raises the question under which circumstances interest groups engage in outside strategies in the first place. Our findings also emphasize that signals of interest group coalitions might work differently vis-a-vis the public, compared to policymakers. While we find that public signals of larger coalitions do little to change public opinion, observational studies show consistently that forming large and diverse coalitions is associated with more interest group success in terms of actual policy outcomes.Footnote 13 In contrast, our results are in line with experimental results on interest group public messages from other policy areas.Footnote 14 Second, the limited effects on salience challenge earlier ideas that one of the main goals behind public lobbying messages is to raise attention to policies in citizens’ minds.Footnote 15 Finally, the limited effects of outside lobbying on public opinion raises the question which other goals interest groups pursue with these strategies. Depending on the group and policy area interest groups might just want to signal to policymakers,Footnote 16 set the agenda on specific policies by putting out the range of possible arguments in favor or against, or raise funding from members and other potential donors.

The paper is structured as follows. We first review the existing experimental evidence on outside lobbying and identify gaps in the literature. Next, we theoretically motivate our study and derive hypotheses regarding outside lobbying strategies, mode of transmission of outside messages, and policies. Third, we describe our research design, sampling and case selection, and estimation strategy. We then present our results in pooled form, across countries, and for different mechanisms linking outside lobbying and public opinion, and discuss implications and limitations of our findings. We close by describing avenues for future research.

Existing evidence & related literature

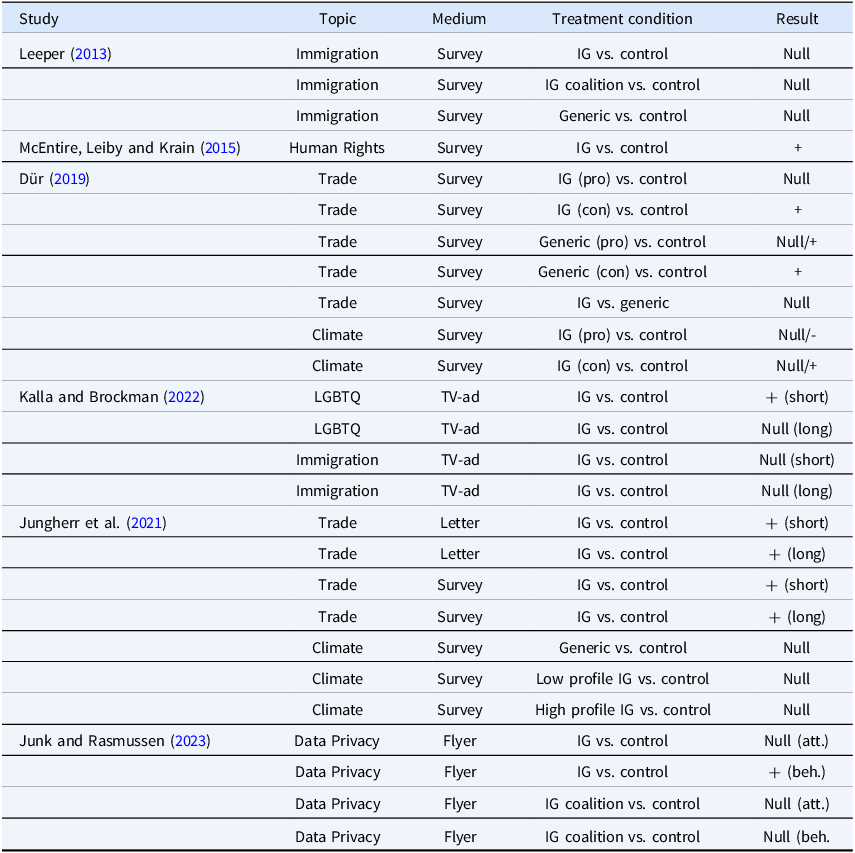

A few studies have explored whether the messages of the interest groups (IG) influence public opinion. Overall, these studies have come to mixed results regarding the effectiveness of interest group messages. The findings can be summarized along topics studied, the medium used to communicate messages, treatment conditions, and the effects. Table 1 summarizes the findings from the experimental literature on outside lobbying.

Table 1. Summary of experimental studies on interest groups’ influence on attitudes. “IG” refers to interest groups. The phrase “generic” refers to arguments in favor or in opposition of a policy but does not include a sender such as interest group. We report positive effects (

![]() $ + $

) when the attitudes of the respondents align with the argument. For Dür’s study, we sometimes report two signs because the study tested the campaign of multiple interest groups and present weak and strong arguments, sometimes reaching different conclusions

$ + $

) when the attitudes of the respondents align with the argument. For Dür’s study, we sometimes report two signs because the study tested the campaign of multiple interest groups and present weak and strong arguments, sometimes reaching different conclusions

Leeper investigated a pro-immigration campaign in the United States using a factorial survey experiment.Footnote 17 Participants received one or three pro-immigration arguments from various sources, including interest groups and political parties. The study found mainly null effects, indicating that neither the presence of an interest group nor multiple groups increased message effectiveness. McEntire, Leiby and Krain conducted a survey experiment in the United States with a fictional human rights group that campaigned against sleep deprivation as an interrogation method.Footnote 18 They found largely positive short-term effects, except for the motivational message, which did not show any impact. Similarly, Kalla and Brockman found that repeated TV ads from an interest group on transgender nondiscrimination had a small positive effect on policy attitudes, although this did not replicate for immigration TV ads.Footnote 19

In Germany, Jungherr and colleaguesFootnote 20 conducted two experiments. The first distributed policy messages about a trade agreement via mail and survey from a low-profile interest group, finding small effects for mailed letters and larger effects for survey treatments. The second survey experiment, supporting an environmental policy, showed no significant effects regardless of whether the message came from a low-profile or high-profile interest group, or was generic. Dür studied public support for a trade agreement through a vignette experiment in Western Europe, finding significant effects only for arguments against the agreement.Footnote 21 A second experiment on the Paris climate agreement showed significant effects for only one out of three groups against the agreement, with null or modest backlash for those in favor. Finally, Junk and Rasmussen conducted a field experiment in Denmark with a high-profile interest group, using online flyers about smart TV privacy and security concerns.Footnote 22 They found null effects across different framing conditions and interest group coalitions for attitudes (“att.” in Table 1), but positive and significant effects for the single interest groups treatment and different measures of individual consumer behavior (“beh.” in Table 1).

Taken together, successful campaigns tend to highlight immediate personal risks, such as human rights abuses,Footnote 23 and personal benefits, such as from trade agreements.Footnote 24 Null effects appear in climate policy and data privacy campaigns.Footnote 25 Contrary to some theoretical expectations, larger coalitions of interest groups are not more persuasive.Footnote 26 Additionally, a high profile interest group seems not be a necessary condition for success.Footnote 27 Finally, generic policy arguments seem as effective or ineffective as arguments presented by interest groups.

We contribute to the existing experimental research on outside lobbying and public policy endorsements in several ways.Footnote 28 First, while previous studies used varied mediums (survey vignettes, TV ads, flyers), there is a lack of direct comparison across these mediums in a single study. Therefore, we randomly vary the three media strategies. We show that outside lobbying is indeed an effective strategy through which interest groups can influence public opinion, but that the effect strongly varies across strength of the message. Because we identified the framing around personal costs and benefits as a decisive factor, we choose two policy proposals from the same policy area (climate change) that vary personal costs to participants. By focusing on two very prominent climate-related policies, we also contribute the ongoing research on the formation of public opinion on climate policiesFootnote 29 and the political consequences thereof.Footnote 30 Second, existing work does not investigate the mechanism linking outside strategies and public opinion. We evaluate potential mechanisms (learning, salience, and norms) and how material- and non-material individual level factors moderate the causal relationship between interest group messages and attitudes. Third, the effectiveness of generic messages versus interest groups remains under-explored. Accordingly, we include a factor with generic policy arguments and the same arguments made by a single high-profile interest group (Greenpeace) or interest group coalition. Finally, there are few studies across different geographical and cultural contexts. Therefore, we test the same campaign messages across two countries (UK and Germany).

Theory: The effect of outside lobbying on public opinion

Rather than directly approaching policymakers through meetings or in official consultations or hearings, interest groups relying on outside lobbying seek to influence decision-makers indirectly by building up public pressure and thereby altering the decision calculus of policymakers. Groups spend abundant resources on achieving media visibility,Footnote 31 be it through press briefings and contacts to reporters or via public protests Footnote 32,Footnote 33

Outside lobbying can thus attempt to alter the perception of policymakers about salience or popularity of a policy, or it can be directed at citizens and seek to affect public opinion directly.Footnote 34 We focus on whether and under which conditions outside lobbying can shape public opinion. We theorize that costlier strategies and mobilization patterns signaling broader public support for a policy will be more effective in raising salience and influencing stated preferences, compared to the less costly alternatives. Footnote 35,Footnote 36 We detail our specific hypotheses below.

Hypotheses

We argue that outside lobbying strategies are effective instruments to sway public opinion, but that the effect is conditional on three characteristics of the message: the medium in which the message is transmitted (H1a, H1b), the messenger (H2a, H2b) and the policy type (H3). First, we argue that the message needs to be very visible to attract attention. Citizens are overwhelmed with information and messages that they have to process every day and interest groups have to fight to get their attention. The attention of citizens to extraordinary, large or spectacular events is much higher than for regular day-to-day events. Since spectacular events cannot be staged all the time, the question is, what can be done. Communication research established that the mode of conveying a message is important for the amount of attention and retention, a message gets.Footnote 37 We therefore expect that the mode of the transmission of a message is a key factor explaining the success of outside lobbying tactics. Showing pictures of a deforested Amazon delta, after all, is much more convincing, than reading a press release with the dry numbers of square miles deforested.

H1a (Strategy): Video and flyer strategies have a positive marginal effect on the outcomes compared to the pure information condition.

H1b (Strategy): Video and flyer strategies have a positive marginal effect on the outcomes compared to the pure control condition.

Second, we suggest that outside lobbying has larger effects when a coalition of diverse interest groups comes together to conduct information campaigns or launch public protests instead of just a single interest group due to the credibility that is associated with a broader alliance of interest groups.Footnote 38 If citizens are exposed to outside lobbying by similar interest groups such as Greenpeace, World Wide Fund of Nature and Friends of the Earth, the arguments made by these NGOs will not catch as much attention as a diverse alliance that e.g. brings together Greenpeace, the National Association of Car Manufacturers and the National Trade Union Confederation. In fact, research has documented how less well-resourced non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have tried to compensate for their lack of resources by teaming up with more diverse coalitions to push for policy reform.Footnote 39 Organizing these diverse interests in one coalition is costly, but it can pay off. Recent observational studies provide some evidence that more diverse interest group coalitions is associated with higher preference attainment across issues,Footnote 40 agenda setting in U.S. Congressional committees,Footnote 41 or more aligned recommendations for regulatory rule making accepted by U.S. federal agencies.Footnote 42 In addition to participation in coalitions, some interest groups like NGOs or trade unions often actively participate in and organize protests—a strategy typically not open to business interest groups. Like the formation of coalition, organizing protests is a costly political signalFootnote 43 that signals to other citizens and policymakers a broader societal support for a given policy position.Footnote 44 Since protests are such a widely used strategy of NGOs, we include them in addition to formation of diverse interest group coalitions. As a baseline hypothesis, we expect that coalition and protests have a positive impact on stated policy support.

H2a (Messenger): Coalition and protest appeals have a positive effect on the outcomes compared to the no messenger condition.

In addition, if a diverse alliance of societal interests can unite behind a common cause, this is a much more credible and convincing signal than a message sent by a single interest group.Footnote 45 Hence, we hypothesize that protests and diverse coalitions will increase stated policy support, compared to single interest group endorsements:

H2b (Coalition): Coalition and protest appeals have a positive effect on the outcomes compared to appeals from single interest groups.

Finally, we expect that the effect of outside lobbying on public opinion varies by policy type. Prior work on public policy and political economyFootnote 46 has stressed that policy issues vary with regard to distributional consequences, which has consequences for preferences formation. Building on this work, we argue that the effectiveness of protests, demonstrations and other publicly visible activities varies with the distributional consequences of the policy issues at question. We expect that it is much easier to affect public opinion when it comes to benefits for citizens as compared to policies on which citizens have to bear additional costs. For example, direct costs of climate policies such as banning of polluting cars have been shown to affect voting behavior for individuals who bear the direct costs of these policies. Differences in the design of carbon taxation have also been shown to affect public opinion on these policiesFootnote 47 . Previous research also posits that salience of the policy moderates interest group policy influence. While some researchers find that under certain circumstances, low salience makes interest group influence easier,Footnote 48 while it increases chances of lobbying success in other casesFootnote 49 In this paper, we sidestep policy salience by focusing on two policies that are both very salient. We therefore posit that outside lobbying is more successful in influencing public opinion on subsidy policies than on taxation policies, given that the former is associated with directly tangible benefits, whereas citizens associate the latter with costs.

H3 (Policy): Baseline support for subsidy policies is higher compared to support for taxation policies.

Mechanisms

We propose that there are three mechanisms linking outside lobbying, attitudes and behavior which we want to investigate. First, respondents might generally update their beliefs and attitudes via learning after being exposed to outside lobbying due to exposure to novel arguments.Footnote 50 Second, respondents might update their attitudes on policy issues simply because outside lobbying on these issues raised salience of these issues in the minds of citizensFootnote 51 . Third, outside lobbying can also influence public opinion by shaping respondents’ perception of social norms. Drawing on a large literature in social psychology, we distinguish between descriptive norms and injunctive normsFootnote 52 and apply these concepts to policy approval. Descriptive norms refer to citizens’ perceptions of what others do in a particular situation. For example, how many people actually comply with a certain policy, such as using electric vehicles or reducing CO2 emissions. Injunctive norms, by contrast, describe citizens’ perceptions of what others approve of or believe one ought to do in a given situation. In the context of policy approval, this includes perceptions of whether others support a certain policy. For simplicity, we refer to these two concepts as perceived public compliance (descriptive norms) and public support (injunctive norms) of a policy.Footnote 53

Research design

To investigate the effect of interest group messages on public opinion, we run two survey experiments, one in Germany and one in the United Kingdom. To field the surveys, we rely on the online access panel by the survey company Respondi/Bilendi. The survey experiments obtained IRB approval at Humboldt-Unviversität zu Berlin (HU-KSBF-EK

![]() $\_$

2022

$\_$

2022

![]() $\_$

0004) and were preregistered.Footnote

54

$\_$

0004) and were preregistered.Footnote

54

Sampling

We recruited a total of

![]() $N = 9,000$

respondents in Germany and the United Kingdom (each

$N = 9,000$

respondents in Germany and the United Kingdom (each

![]() $N = 4,500$

). The surveys are nationally representative, based on age, gender, and region, and were fielded in May and June 2022. We conduct the survey experiment across Germany and the UK to bolster the external validity of our findings across two comparable countries that differ along a range of characteristics. Both countries are Western democracies that are similar with regard to economic performance and size. However, they differ with regard to the role of interest groups in society. Germany is often depicted as a country with corporatist interest intermediation with many industry-wide trade associations and collective bargaining, while the UK is considered a typical example of a pluralist interest group system.Footnote

55

While the two countries differ on some dimensions, we have no a priori expectations or pre-registered hypotheses about differences in effects across countries.

$N = 4,500$

). The surveys are nationally representative, based on age, gender, and region, and were fielded in May and June 2022. We conduct the survey experiment across Germany and the UK to bolster the external validity of our findings across two comparable countries that differ along a range of characteristics. Both countries are Western democracies that are similar with regard to economic performance and size. However, they differ with regard to the role of interest groups in society. Germany is often depicted as a country with corporatist interest intermediation with many industry-wide trade associations and collective bargaining, while the UK is considered a typical example of a pluralist interest group system.Footnote

55

While the two countries differ on some dimensions, we have no a priori expectations or pre-registered hypotheses about differences in effects across countries.

An important question is how comparable Germany and the United Kingdom are regarding the policies studied here, as well as the state of public opinion. According to Kollman,Footnote 56 the stage of legislation, and the status quo relative to the policy preferences of the public are important determinants for whether interest groups decide to use outside lobbying. Outside lobbying will be more effective in early stages of the legislative process, when salience of policies is still low and the goal is to put a policy on the agenda to begin with.Footnote 57 If the interest group supports a policy that is more popular than the status quo among the public (as could be plausibly the case for some environmental policies), then incentives to use outside lobbying are larger.

Both Germany and the United Kingdom had carbon taxation and electric-vehicle purchase subsidies in place at the time of the survey.Footnote 58 Since 2021, the UK uses the UK Emissions Trading System (UK ETS), while Germany is part of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) since 2021, though CO2 pricing is higher expensive under the EU ETS, compared to the UK ETS.Footnote 59 Moreover, both countries had purchase incentive for electric vehicles at the time of the survey,Footnote 60 which was more generous in Germany (EUR 5,625 to EUR 9,000, depending on type of vehicle), compared to the UK (approx. GBP 2,500).Footnote 61 In terms of public opinion, a vast majority of citizens in both countries believes that climate change is a serious threat to humanity and thinks that their government should do more do address climate change. However, there is more public support for policies to tackle climate change in the UK, compared to Germany.Footnote 62

Treatments

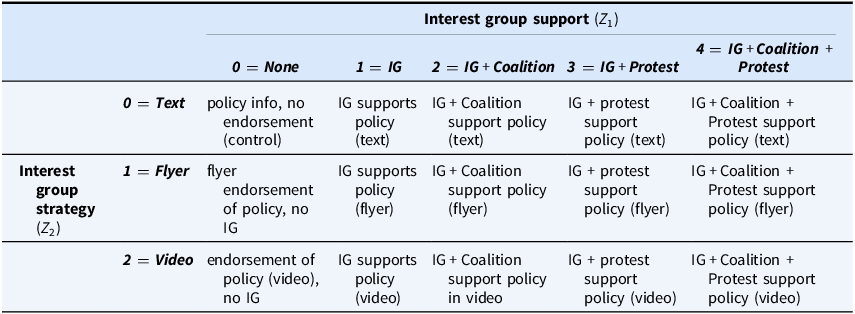

We use a

![]() $3 \times 5$

factorial design which is summarized in Table 2. In each experiment, we present the subjects with a vignette describing an environmental policy proposal. We investigate two proposals: one distributive policy (electric-vehicle purchase subsidy) and one redistributive policy (CO2 taxation). We vary two Dimensions in the experiment. First, we vary the interest group support. We expect larger and more diverse alliances of societal interests to be a more credible and convincing signal than a message send by a single interest group. Hence, we randomly exposed respondents to different interest group supports: (1) as control, no interest group appeared, (2) Greenpeace alone supported the policy, (3) Greenpeace supported the policy together with a coalition of interest groups, (4) Greenpeace supported the policy and organized a public protest, and, (5) Greenpeace supported the policy together with an interest group coalition and organized a public protest. We choose Greenpeace as one of the largest environmental NGOs since Greenpeace is widely known in both Germany and the UK.Footnote

63

For the coalition groups, we choose a combination of well-known and broadly comparable business, trade union, and societal interest groups in GermanyFootnote

64

and the United Kingdom.Footnote

65

We include protests as part of two treatment conditions, since environmental interest groups regularly join or organize protests to demonstrate broad public support for their demands.Footnote

66

Second, we vary the interest group strategy. We expect more costly modes of messaging to be more effective, compared to purely informational strategies.Footnote

67

Thus, we randomly assign whether respondents see (1) a text, as control condition, (2) an informational flyer, or, (3) whether respondents receive an informational video. Importantly, in the [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Flyer] condition, respondents get information about the policy issue and arguments endorsing a policy with no reference to an author. The combination [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] constitutes our control condition. Here, respondents only get information about the policy issue, but no endorsement.

$3 \times 5$

factorial design which is summarized in Table 2. In each experiment, we present the subjects with a vignette describing an environmental policy proposal. We investigate two proposals: one distributive policy (electric-vehicle purchase subsidy) and one redistributive policy (CO2 taxation). We vary two Dimensions in the experiment. First, we vary the interest group support. We expect larger and more diverse alliances of societal interests to be a more credible and convincing signal than a message send by a single interest group. Hence, we randomly exposed respondents to different interest group supports: (1) as control, no interest group appeared, (2) Greenpeace alone supported the policy, (3) Greenpeace supported the policy together with a coalition of interest groups, (4) Greenpeace supported the policy and organized a public protest, and, (5) Greenpeace supported the policy together with an interest group coalition and organized a public protest. We choose Greenpeace as one of the largest environmental NGOs since Greenpeace is widely known in both Germany and the UK.Footnote

63

For the coalition groups, we choose a combination of well-known and broadly comparable business, trade union, and societal interest groups in GermanyFootnote

64

and the United Kingdom.Footnote

65

We include protests as part of two treatment conditions, since environmental interest groups regularly join or organize protests to demonstrate broad public support for their demands.Footnote

66

Second, we vary the interest group strategy. We expect more costly modes of messaging to be more effective, compared to purely informational strategies.Footnote

67

Thus, we randomly assign whether respondents see (1) a text, as control condition, (2) an informational flyer, or, (3) whether respondents receive an informational video. Importantly, in the [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Flyer] condition, respondents get information about the policy issue and arguments endorsing a policy with no reference to an author. The combination [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] constitutes our control condition. Here, respondents only get information about the policy issue, but no endorsement.

Table 2. Experimental design: Interest group (IG) support and strategy, factors and levels

Outcomes

We investigate two main types of outcomes: (1) stated preferences for each policy and (2) actual behavior in support of (or opposition to) the policy. For both the carbon-tax referendum and the electric-car subsidy referendum, we record respondents’ intended vote on a binary scale:

![]() $1 = $

vote in favor,

$1 = $

vote in favor,

![]() $0 = $

vote against. Each referendum question yields its own binary outcome variable. To measure behavior, respondents can choose whether to co-sign a pre-written letter about the policy. This decision is captured on a three-point scale:

$0 = $

vote against. Each referendum question yields its own binary outcome variable. To measure behavior, respondents can choose whether to co-sign a pre-written letter about the policy. This decision is captured on a three-point scale:

![]() $1 = $

send supportive letter,

$1 = $

send supportive letter,

![]() $0 = $

send no letter,

$0 = $

send no letter,

![]() $ - 1 = $

send opposing letter. The letters are forwarded to the relevant minister—either the German Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action or the British Minister of State for Business, Energy and Clean Growth—so the action carries real political weight. In terms of mechanisms, we measure (1) policy salience, (2) learning about policy arguments, and (3) social norms regarding the support of the policies in society and the personal environment of respondents, where we also differentiate between perceived support for norms (descriptive norms), and perceived compliance regarding the norms (injunctive norms).Footnote

68

$ - 1 = $

send opposing letter. The letters are forwarded to the relevant minister—either the German Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action or the British Minister of State for Business, Energy and Clean Growth—so the action carries real political weight. In terms of mechanisms, we measure (1) policy salience, (2) learning about policy arguments, and (3) social norms regarding the support of the policies in society and the personal environment of respondents, where we also differentiate between perceived support for norms (descriptive norms), and perceived compliance regarding the norms (injunctive norms).Footnote

68

Estimation and analysis

Our analysis focuses on the marginal causal effect of each treatment level of each factor,

![]() ${Z_1}$

and

${Z_1}$

and

![]() ${Z_2}$

, on our outcome

${Z_2}$

, on our outcome

![]() ${Y_i}$

(policy support). We recode

${Y_i}$

(policy support). We recode

![]() ${Z_1}$

(no support/ support interest group/ +coalition/ +protest) and

${Z_1}$

(no support/ support interest group/ +coalition/ +protest) and

![]() ${Z_2}$

(strategy text/flyer/video) as factors. Therefore, potential outcomes

${Z_2}$

(strategy text/flyer/video) as factors. Therefore, potential outcomes

![]() ${Y_{z1,z2}}$

are indexed by both factors

${Y_{z1,z2}}$

are indexed by both factors

![]() $Z1 = zi$

and

$Z1 = zi$

and

![]() $Z2 = zi$

, where

$Z2 = zi$

, where

![]() $zi$

refers to the particular factor level. We estimate the treatment effects using pre-registered fully saturated model including all interactions for each factor level of

$zi$

refers to the particular factor level. We estimate the treatment effects using pre-registered fully saturated model including all interactions for each factor level of

![]() ${Z_1}$

and

${Z_1}$

and

![]() ${Z_2}$

:

${Z_2}$

:

estimated with lm_robust and HC2 (“stata”) standard errors. The coefficients for the levels of

![]() ${Z_1}$

capture the difference in the outcome between each level and the reference level (

${Z_1}$

capture the difference in the outcome between each level and the reference level (

![]() ${Z_1} = 0$

,—information about policy issues, no support), holding

${Z_1} = 0$

,—information about policy issues, no support), holding

![]() ${Z_2}$

at its reference category (control–text) (

${Z_2}$

at its reference category (control–text) (

![]() $E\left( {{Y_{i,0}} - {Y_{0,0}}} \right)$

). Likewise the coefficient

$E\left( {{Y_{i,0}} - {Y_{0,0}}} \right)$

). Likewise the coefficient

![]() ${Z_2}$

shows the difference in the outcome variable between the levels of

${Z_2}$

shows the difference in the outcome variable between the levels of

![]() ${Z_2}$

, holding

${Z_2}$

, holding

![]() ${Z_1}$

at its reference category (

${Z_1}$

at its reference category (

![]() $E({Y_{0,i}} - {Y_{0,0}}$

)). Coefficients of interaction terms (

$E({Y_{0,i}} - {Y_{0,0}}$

)). Coefficients of interaction terms (

![]() ${Z_1} \times {Z_2}$

) show how the effect (slope) of

${Z_1} \times {Z_2}$

) show how the effect (slope) of

![]() ${Z_2}$

differ for different levels of

${Z_2}$

differ for different levels of

![]() ${Z_1}$

. Because every possible messenger–strategy combination appears in the design, the fully saturated model recovers all

${Z_1}$

. Because every possible messenger–strategy combination appears in the design, the fully saturated model recovers all

![]() $5 \times 3 = 15$

cell means

$5 \times 3 = 15$

cell means

![]() ${\mu _{i,j}}$

.

${\mu _{i,j}}$

.

Estimands and Hypothesis Tests

Equation (1) is parameterized so that the Control × Text cell is the intercept. Therefore, each strategy main-effect coefficient (

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{Flyer}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{Video}}}}$

) measures

${\beta _{{\rm{Flyer}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{Video}}}}$

) measures

and each messenger main-effect coefficient (

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}}$

) measures

${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}},{\rm{\;\;}}{\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}}$

) measures

First, we plot all 15 cell means and their corresponding confidence intervals to visually inspect the results. More formally, to test whether presenting the same campaign message as a Video or a Flyer is more persuasive than presenting it as plain Text (H1a), we keep the fully saturated model and use emmeans to compute strategy means averaged over the four messenger rows that contain a cue (IG, IG

![]() $ + $

Coalition, IG

$ + $

Coalition, IG

![]() $ + $

Protest, IG

$ + $

Protest, IG

![]() $ + $

Coalition

$ + $

Coalition

![]() $ + $

Protest), thereby omitting the single Control × Text cell. Because the design has no Text-only cell without a messenger, this is the closest feasible comparison. We then test the two contrasts

$ + $

Protest), thereby omitting the single Control × Text cell. Because the design has no Text-only cell without a messenger, this is the closest feasible comparison. We then test the two contrasts

![]() ${{\rm{\Delta }}_{{\rm{Video}} - {\rm{Text}}}} = 0$

and

${{\rm{\Delta }}_{{\rm{Video}} - {\rm{Text}}}} = 0$

and

![]() ${{\rm{\Delta }}_{{\rm{Flyer}} - {\rm{Text}}}} = 0$

with the robust

${{\rm{\Delta }}_{{\rm{Flyer}} - {\rm{Text}}}} = 0$

with the robust

![]() $t$

-statistics returned by emmeans. To test whether using a Flyer or a Video is more effective than the pure-control message (H1b), we examine whether the corresponding strategy coefficients differ from zero:

$t$

-statistics returned by emmeans. To test whether using a Flyer or a Video is more effective than the pure-control message (H1b), we examine whether the corresponding strategy coefficients differ from zero:

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{Flyer}}}} = 0$

and

${\beta _{{\rm{Flyer}}}} = 0$

and

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{Video}}}} = 0$

. To test whether mentioning a Coalition or a Protest group is more effective than naming no messenger at all (H2a), we check whether their messenger coefficients differ from zero:

${\beta _{{\rm{Video}}}} = 0$

. To test whether mentioning a Coalition or a Protest group is more effective than naming no messenger at all (H2a), we check whether their messenger coefficients differ from zero:

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}} = 0$

and

${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}} = 0$

and

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}} = 0$

. To test whether a Coalition or a Protest messenger is more effective than a single interest-group messenger (H2b), we compare each of their coefficients to the single-IG coefficient:

${\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}} = 0$

. To test whether a Coalition or a Protest messenger is more effective than a single interest-group messenger (H2b), we compare each of their coefficients to the single-IG coefficient:

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}} = {\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}}$

and

${\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}} = {\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Coalition}}}}$

and

![]() ${\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}} = {\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}}$

. Because the restrictions involve only main-effect coefficients, each test compares messenger or strategy treatments holding the other factor at its reference level (Text). To test H3, we keep only the pure-control cells (Control × Text) for the CO

${\beta _{{\rm{IG}}}} = {\beta _{{\rm{IG}} + {\rm{Protest}}}}$

. Because the restrictions involve only main-effect coefficients, each test compares messenger or strategy treatments holding the other factor at its reference level (Text). To test H3, we keep only the pure-control cells (Control × Text) for the CO

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}_2}$

and E-car policies, fit a two-cell model, and use lh_robust to test the single restriction

${{\rm{\;}}_2}$

and E-car policies, fit a two-cell model, and use lh_robust to test the single restriction

![]() ${\gamma _{{\rm{CO}}2}} = {\gamma _{{\rm{Ecar}}}}$

.

${\gamma _{{\rm{CO}}2}} = {\gamma _{{\rm{Ecar}}}}$

.

Results

First, in Figure 1, we report the main effects of each factor level on the policy support for E-car subsidies (left) and CO2 taxation (right). The upper panel presents the results for the stated preferences (choice), and the lower panel shows the results for the behavioral outcome (sending a letter). The x-axis presents the different levels of policy support from interest groups and interest group support (

![]() ${Z_1}$

). The different colors for point estimates and lines correspond to the different strategies (

${Z_1}$

). The different colors for point estimates and lines correspond to the different strategies (

![]() ${Z_2}$

). The combination [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] constitutes the pure control with no endorsement.Footnote

69

${Z_2}$

). The combination [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] constitutes the pure control with no endorsement.Footnote

69

Figure 1. Effect of interest group support (

![]() ${Z_1}$

) and strategy (

${Z_1}$

) and strategy (

![]() ${Z_2}$

) on policy support. Points in the figure present group means and lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for each group mean. The condition [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] is the control condition. Here, respondents only see an introduction to the policy issue, but no endorsement.

${Z_2}$

) on policy support. Points in the figure present group means and lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for each group mean. The condition [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text] is the control condition. Here, respondents only see an introduction to the policy issue, but no endorsement.

We first examine the results for E-car subsidies. Compared to the pure control condition, all strategies are effective in raising policy support and have similar effect sizes. Most strikingly, policy support flyers with no interest group support ([Supporter = Control, Strategy = Flyer]) increases stated support similarly to messages from interest groups, coalitions, or protests, irrespective of the medium ([Supporter = IG, Strategy = Text/Flyer/Video]). The results suggest that respondents are persuaded equally well by pure support messages as by messages from individual interest groups, protests, or coalitions. For E-car subsidies, the medium has also no influence on the effectiveness of the message. In the case of CO2 taxation, we find that only the video treatment has significant positive effect. Again, there are surprisingly little differences between the different types of interest group support. The figure also reveals that policy support is, on average, larger for E-car subsidies than for CO2 taxation, highlighting differences in popularity between distributive policies (subsidy) and policies imposing private costs (tax). Also, while policy endorsements increase support irrespective of interest group involvement for E-car subsidies, they have no discernibly effect on support for CO2 taxes. See sections D2 and D3 in the appendix for the formal tests comparing the different coefficients.

Taken together, we find little evidence for Hypothesis 1a. We find evidence supporting Hypotheses 1b and 2a. However, these effects hold only for the subsidy policy. We find no evidence supporting Hypothesis 2b. Interest-group coalitions did not persuade respondents more than single interest groups or policy campaigns with a single sender.

We next examine the behavioral outcome–respondents’ decision to co-sign a letter (lower panel of Figure 1). For E-car subsidies, every treatment raises behavioral support relative to the pure control, and the effects are remarkably similar. Most notably, a simple flyer with no interest-group endorsement ([Supporter = Control, Strategy = Flyer]) encourages sending a letter as effectively as messages backed by individual interest groups, coalitions, or protests, irrespective of the medium. Hence, respondents are moved to act by a plain appeal just as much as by endorsements from organized interests.

For the CO2 taxation, the pattern differs. Flyers, protests, and coalition messages leave behavior essentially unchanged. However, a message endorsed by a single interest group ([Supporter = IG]) produces a positive and statistically significant increase in the probability of sending a supportive letter compared to the control condition. All other point estimates hover around zero with confidence intervals that overlap the baseline. Thus, for a policy that imposes private costs, mobilization appears to hinge on the added credibility supplied by an interest-group endorsement, whereas purely informational cues are insufficient.

Taken together, the behavioral patterns broadly mirror the choice results for the subsidy but diverge for the tax. For E-car subsidies, persuasive messages increase both stated support and concrete action, and overall levels of support are consistently higher than for the tax. For CO2 taxation, by contrast, the results are inconsistent: the video treatment increases stated support regardless of interest group support but does not move behavior, whereas the interest-group endorsement raises behavior without changing stated preferences. This asymmetry suggests that distributive policies offering visible private benefits elicit stronger persuasion and mobilization, while tax policies that impose costs are less likely to changes preferences nor actions.

The findings are corroborated by the evidence in Table D1 and Table D2 in the appendix that include the main effects and interactions. One finding stands out: The negative coefficients on the interactions between support flyer and interest group support indicates that the positive effects of flyers and videos vanishes for respondent who receive the interest group support treatment. This highlights the main findings from Figure 1 of no differences between types of interest group support.Footnote

70

Next, we show the results for interest group endorsements on policy support for CO2 taxation in Table D2. Across the board, effect sizes for the treatments are much smaller, and in almost all cases, fail to reach conventional levels of significance (

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

). Only the interest group endorsement and the video treatment have modest effects on stated support and a letter to the minister, respectively.

$p \lt 0.05$

). Only the interest group endorsement and the video treatment have modest effects on stated support and a letter to the minister, respectively.

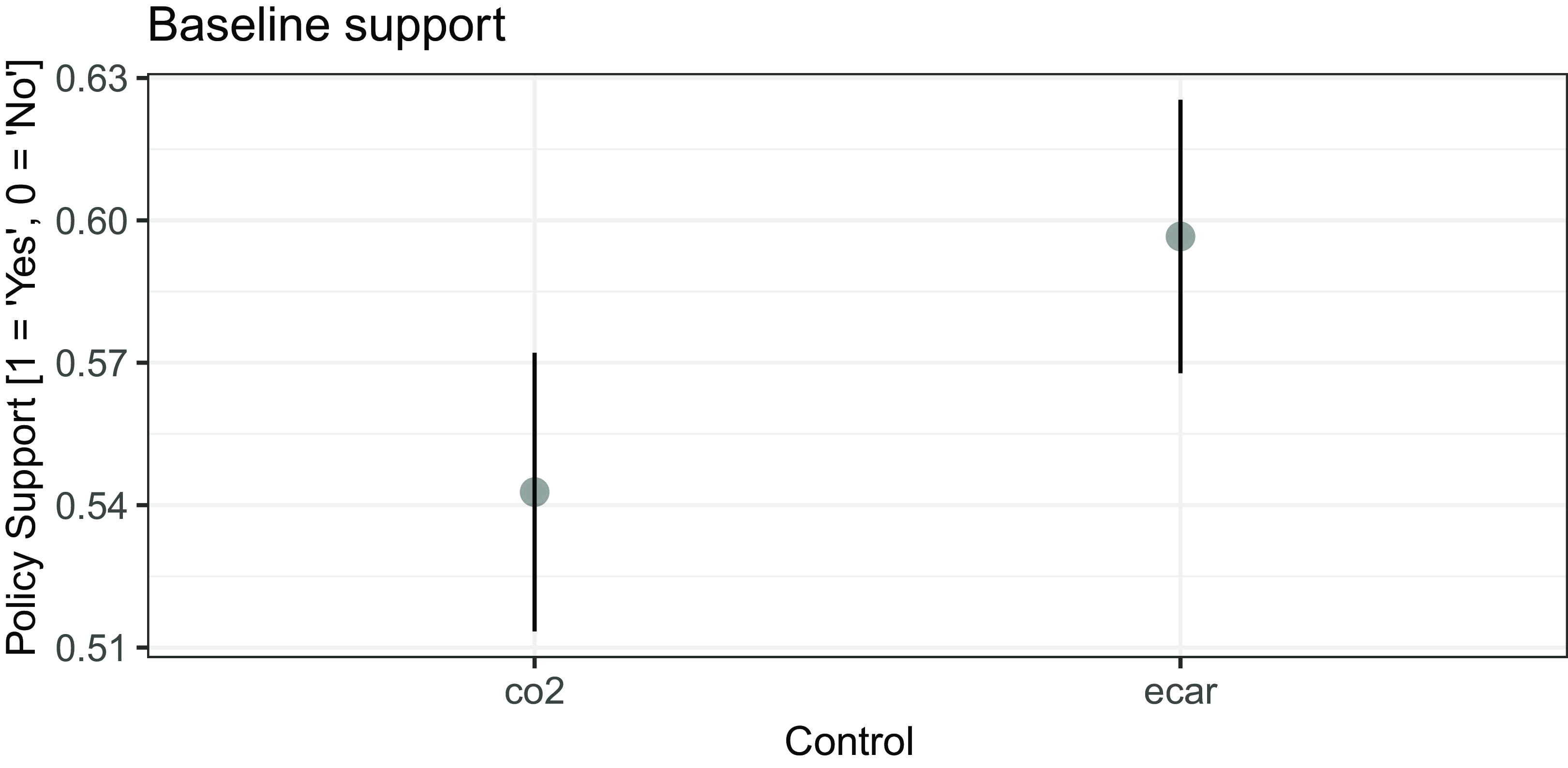

Baseline support policies

Next, we investigate if respondents have differences in baseline support for the two policies (Hypothesis H3). To compare the baseline support for each policy, we compare the stated support for each policy under the control condition that only informs respondents about the policy at hand. To test the hypothesis, we merge the data from the two baseline condition and ran a linear hypothesis test. Figure 2 shows the means and confidence intervals of support for the

![]() ${\rm{C}}{{\rm{O}}_2}$

tax and the E-car subsidy under their respective control conditions. We observe that support for the subsidy is higher than for the tax. Appendix D4 presents the results from linear hypothesis test and also finds a significant difference between the two. The corresponding

${\rm{C}}{{\rm{O}}_2}$

tax and the E-car subsidy under their respective control conditions. We observe that support for the subsidy is higher than for the tax. Appendix D4 presents the results from linear hypothesis test and also finds a significant difference between the two. The corresponding

![]() $p$

-value indicates that we can reject the null hypothesis that the two coefficients are equal at conventional levels of statistical significance.

$p$

-value indicates that we can reject the null hypothesis that the two coefficients are equal at conventional levels of statistical significance.

Figure 2. Baseline support (combination [Supporter = Control, Strategy = Text]) by policy. Point Estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

Results by country

In addition to our pre-registered analyses, we also show the main results separated by country in Figure 3. For better comparability, all graphs are shown with the same y-axis range. There are three main conclusions from this comparison across countries. First, support for each policy across conditions is typically larger in the UK than in Germany. This confirms existing evidence that on most dimensions of support for climate-related policies, public support in the UK is either larger or as large as in Germany.Footnote 71 Second, the effects of different messengers vary across countries. For the e-car subsidy policy, the treatment effects are stronger in Germany compared to the UK, while most point estimates are still positive and significantly different from the control condition in the UK. Meanwhile, in both the UK and Germany, the differences between different types of messengers are not significantly different from zero. Hence, our finding of no differences between single interest groups and coalitions or protests is not driven by one country. Finally, the larger effect of the video treatments shows across all countries and policies, but mostly in the control condition with no interest group, coalition, or protest. Across the other messenger conditions, we find very little differences in support across texts, videos, and flyers in both countries. Overall, the results by countries mostly confirms the main conclusions of the pooled results above. While interest group messages boost support for policies in the case of electric-vehicle subsidies, we find no differences between narrow groups and broad interest group coalitions or protests.

Figure 3. Effect of interest group support (

![]() ${Z_1}$

) and strategy (

${Z_1}$

) and strategy (

![]() ${Z_2}$

) on policy support by policy and country. Points in the figure present group means and lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for each group mean.

${Z_2}$

) on policy support by policy and country. Points in the figure present group means and lines are 95 percent confidence intervals for each group mean.

Mechanisms

To understand how outside lobbying efforts influence voters’ policy attitudes and behavior, we use an intermediate outcome test (IOT). In particular, to assess whether a mediator could potentially explain the effect of our treatment (interest group lobbying) on our outcome (changes in attitudes), we investigate whether the treatment has an effect on the mediator.Footnote

72

To do so, we estimate average treatment effect on the mediator (ATM) as: + = E[M_i(T = 1)−M_i(T = 0)] + where

![]() $M$

is the mediator and

$M$

is the mediator and

![]() $T$

is the treatment. We investigate four pre-registered mechanisms: argument learning, issue salience, changes in descriptive norms, and changes in injunctive norms. First, we assess whether the lobbying campaign influenced beliefs about policy arguments by comparing responses before and after treatment. Specifically, we ask respondents to evaluate five arguments supporting electric-vehicle subsidies: reducing CO

$T$

is the treatment. We investigate four pre-registered mechanisms: argument learning, issue salience, changes in descriptive norms, and changes in injunctive norms. First, we assess whether the lobbying campaign influenced beliefs about policy arguments by comparing responses before and after treatment. Specifically, we ask respondents to evaluate five arguments supporting electric-vehicle subsidies: reducing CO

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}_2}$

emissions and environmental burdens, decreasing traffic noise, promoting international cooperation on climate protection, reducing driving costs through maintenance savings and lower fuel prices, and serving as an effective measure against climate change. Responses are aggregated into a single index using factor loadings. Second, we measure perceived policy salience on a scale from 0 (“not important at all”) to 10 (“very important”), recorded both pre- and post-treatment. Third, we analyze social norms through two dimensions. The first captures perceived public compliance, defined as the percentage of people in the respondent’s country or personal environment who comply with the policy (e.g., buying electric vehicles). The second measures perceived public support, assessing respondents’ perceptions of the percentage of people who support the policy. Given the significant effect of the campaign on respondents’ attributes, the mechanism analysis focuses on electric-vehicle subsidies.Footnote

73

${{\rm{\;}}_2}$

emissions and environmental burdens, decreasing traffic noise, promoting international cooperation on climate protection, reducing driving costs through maintenance savings and lower fuel prices, and serving as an effective measure against climate change. Responses are aggregated into a single index using factor loadings. Second, we measure perceived policy salience on a scale from 0 (“not important at all”) to 10 (“very important”), recorded both pre- and post-treatment. Third, we analyze social norms through two dimensions. The first captures perceived public compliance, defined as the percentage of people in the respondent’s country or personal environment who comply with the policy (e.g., buying electric vehicles). The second measures perceived public support, assessing respondents’ perceptions of the percentage of people who support the policy. Given the significant effect of the campaign on respondents’ attributes, the mechanism analysis focuses on electric-vehicle subsidies.Footnote

73

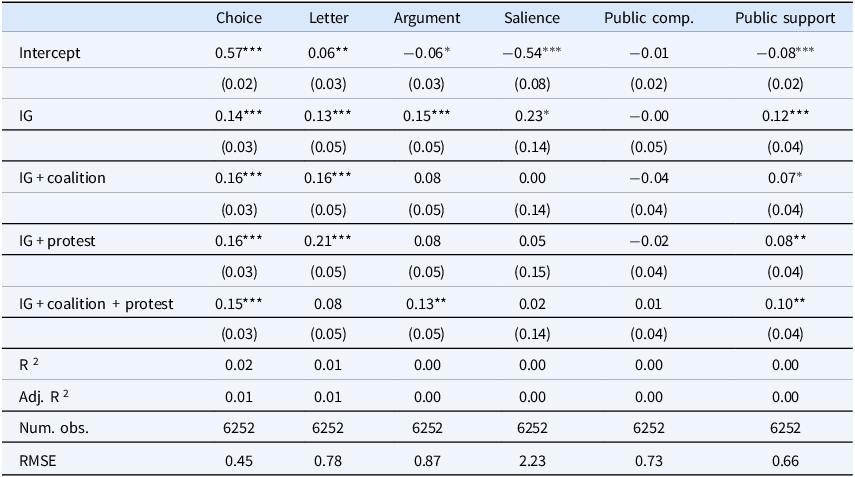

We summarize the results for the ATMs in Table 3. The analysis is conducted on a sample with complete covariate information in order to check a central assumption of mediation analysis that we discuss below. In brief, we find positive and fairly uniform effects of every interest-group cue on perceived public support for the electric-vehicle norm. Each of the four messenger variants raises support by roughly 7–12 percentage points, and three of the four reach conventional significance. The learning outcomes tell a more uneven story: interest-group messages do improve respondents’ recall of policy arguments, but the size of that gain ranges from about 8 to 15 percentage points, and is significant only for the IG-only and IG + Protest treatments. We detect no shifts in issue salience or in perceptions of public compliance. A plausible interpretation is that messenger cues readily move people’s sense of “what others think” but do less to deepen factual understanding, which typically requires more sustained attention than a single, brief exposure can offer.

Table 3. E-car policy, based on fully saturated models. Results for interest group strategy are not displayed. Sample consists of data with complete set of covariates also used for causal forests

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.01$

;

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.01$

;

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.05$

;

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.05$

;

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.1$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.1$

.

While these findings provide suggestive evidence, they are insufficient to establish the presence or absence of causal mechanisms. As Blackwell, Ma and Opacic demonstrate, a significant treatment effect on the mediator constitutes evidence for a causal mechanism only under the strong assumption of full monotonicity.Footnote 74 Full monotonicity requires three conditions: (1) the treatment weakly increases the outcome regardless of the mediator’s value, (2) the treatment weakly increases the mediator, and (3) the mediator weakly increases the outcome regardless of treatment. For the argument learning and perceived public support mechanisms, monotonicity is plausible but remains subject to certain challenges, particularly heterogeneity in direct and indirect effects. For instance, individuals with pre-existing opposition to electric-vehicle subsidies or aversion to outside lobbying may respond negatively to the treatment, which could counteract the positive effects on both the mediator and outcome.

To explore the plausibility of monotonicity, we test one of its key implications. Specifically, monotonicity implies that individual treatment effects are weakly greater than zero, which in turn suggests that conditional average treatment effects (CATEs) must also be non-negative.Footnote

75

Therefore, we estimate the distribution of CATEs for

![]() $T \to Y$

and

$T \to Y$

and

![]() $T \to M$

using causal forests.Footnote

76

This approach leverages machine learning to flexibly capture heterogeneous treatment effects across our covariate space of 85 variables.Footnote

77

Unfortunately, we are unable to provide evidence for the third component of the full monotonicity assumption (

$T \to M$

using causal forests.Footnote

76

This approach leverages machine learning to flexibly capture heterogeneous treatment effects across our covariate space of 85 variables.Footnote

77

Unfortunately, we are unable to provide evidence for the third component of the full monotonicity assumption (

![]() $M \to Y$

), which states that the mediator weakly increases the outcome regardless of the treatment. This is because we lack variation in the mediator that is independent of the treatment. See Appendix D5 for the complete analysis and description.

$M \to Y$

), which states that the mediator weakly increases the outcome regardless of the treatment. This is because we lack variation in the mediator that is independent of the treatment. See Appendix D5 for the complete analysis and description.

We find evidence that two out of the three monotonicity assumptions seem to hold for the public support mechanism, providing suggestive—albeit tentative—evidence for causal mediation. For the argument learning mechanism, the results remain inconclusive, as our falsification test does not rule out potential violations of monotonicity. Regarding the salience mechanism, we observe that the monotonic mediator response assumption holds for at least a subset of treatment conditions. This suggests that, for those conditions, there is likely no average indirect effect of the treatment on the outcome through this mediator.

Discussion and conclusion

Limitations and external validity

One possible explanation for the null difference between the treatment condition with and without the interest group cue is that respondents already knew Greenpeace would support a pro-climate policy. If the interest groups’ position was fully anticipated, the cue did not provide new information and any source-cue effect would be attenuated.Footnote 78 We cannot rule out this concern completely because the questionnaire did not ask for respondents’ prior knowledge of Greenpeace’s position. However, three considerations suggest that pre-treatment expectations are unlikely to be the only reason that the source cue fails to change attitudes. First, the experiment includes several variables that should correlate with prior knowledge about the policy position of the interest group: trust in specific interest-groups, formal group membership, and self-reported alignment with the interest group’s position. If pre-existing expectations were driving the null effect, treatment effects ought to vary across these dimensions. Appendix D6 implements a causal forest analysis across 85 covariates. We find that none of these variables are strong predictors of heterogeneous treatment effects. Second, the same null effect appears in the coalition treatment, where Greenpeace is embedded in a broad alliance. It is less likely that respondents held precise priors about the joint position of this eclectic group or each member, yet the coalition cue has no effect here either. The results also hold across countries and priors likely differ across countries. This pattern weakens the claim that cue predictability alone explains the results. Third, our design choice intentionally maximized external validity. In most real campaigns Greenpeace does adopt a pro-climate policy position. By positioning Greenpeace in its usual pro-climate role, we mirror the common real-world setting and maintain continuity with earlier studies,Footnote 79 even though it limits what we can say about informational mechanism. However, future experiments should address the issue more directly by (i) measuring priors at baseline and re-estimating effects among the truly “surprised” respondents using an instrumental variable approach, (ii) introducing counter-stereotypical yet plausible cues—such as an automobile association endorsing a carbon tax—following Dür (Reference Dür2019), and (iii) manipulating uncertainty about the senders’ stance, for example, by informing some respondents that Greenpeace has recently reversed its position.

Another concern could be that respondents view the broad coalition between Greenpeace and large business associations as not credible. This could explain why we do not find differences between single interest groups and the coalition treatment. While we cannot rule out this possibility, we think there are good reasons to believe that the treatment conditions are credible. First, Greenpeace has in the past formed coalitions with business actors, such as Co-op Food in the UK (see Figure A3 in the appendix).Footnote 80 Second, an increase in the e-car subsidy would benefit parts of German and British industry, such as large car manufacturers based in both countries, by stimulating demand for their products. Thus, a coalition between Greenpeace and industry groups regarding this industrial subsidy should seem reasonably credible to respondents. Still, respondents might be familiar with the business groups’ positions and find it at odds with Greenpeace, at least for the carbon taxation policy. While we did not record how familiar respondents are with the respective interest groups, related work investigate to what extent regular citizens can provide credible assessments of the positions of interest groups in Germany.Footnote 81 They find that citizens have less clear ideas of the positions of interest groups and business associations, compared to political parties, reflecting the lower public profile of most interest groups.Footnote 82 Third, while we did not record how familiar respondents were with the respective interest groups, we did ask related questions on trust in specific interest-groups, formal group membership, and self-reported alignment with the interest group’s position. We find in Appendix D5 that none of these variables related to familiarity with group positions drive heterogeneous treatment effects. Finally, while we find that the coalition treatment is not more effective in swaying public opinion than the single interest group treatment, it is also not less effective. The fact that the effect does not drop for the coalition treatment and that is generally indistinguishable from the Greenpeace only treatment in both countries, and for both policies investigated here, provides some evidence that, at the very least, the coalition treatment did not result in a loss of credibility among respondents.

Moreover, it could be that the number of groups within the coalition treatment is too large and cognitively demanding for respondents. However, the goal of our coalition treatments is not to assess the contribution of each single group, but to signal size and diversity of the coalition, in line with previous work.Footnote 83 Moreover, coalitions consisting of seven or more interest groups are not uncommon. In Table A1 in the appendix, we show the example of the “Climate Coalition,” which shows 18 different groups on the front page presenting the coalition members, in addition to consisting of more than 100 organizations in total. Thus, we think that our treatment has external validity regarding the size of the coalition.

Finally, an important limitation of our study is that we only vary the sender and the medium of the interest group message. In reality, interest groups often tailor their arguments to fit the intended audience. Hence, a rich literature varies appeals across different policy areas, such as human rights,Footnote 84 international trade,Footnote 85 data privacy,Footnote 86 or transgender rights.Footnote 87 A consistent finding is that different appeals and frames matter for changing attitudes, sometimes more than source cues.Footnote 88 In contrast to this work, we have held constant the content of the messages in order to limit complexity and to guarantee that we have enough statistical power to detect relatively small effects. Moreover, we intentionally provided multiple argument to avoid relying only specific types of arguments. While this provides some benefits in terms of internal validity and statistical power, our findings have only limited relevance for advocacy groups who wish to know which types of messaging strategies maximize impact on public opinion.

Conclusion

Our results have implications for the study of interest groups. First, we find that outside lobbying efforts have a significant short-term effect on public attitudes but only for policies that deliver clear, direct benefits to citizens, such as electric-vehicle subsidies. By contrast, for redistributive policies like CO

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^2}$

taxation, which impose direct costs on citizens, outside lobbying has little to no effect. This finding aligns with prior research on public policy preferences which suggests that citizens are more receptive to distributive policies when associated personal costs are lower

Footnote 89,Footnote 90

While policy salience could also explain part of the difference in effects,Footnote

91

we find little evidence that lobbying increases the salience of the policy issue.Footnote

92

Future work could systematically vary salience or manipulate costs and benefits of a policy. While on salient policies, individual preferences are likely informed by partisanship, especially in highly polarized contexts, preferences are probably more easily shaped via outside lobbying on low salience topics.Footnote

93

Another avenue could be to investigate how individuals trade-off personal and societal costs and benefits of different policies.

${{\rm{\;}}^2}$

taxation, which impose direct costs on citizens, outside lobbying has little to no effect. This finding aligns with prior research on public policy preferences which suggests that citizens are more receptive to distributive policies when associated personal costs are lower

Footnote 89,Footnote 90

While policy salience could also explain part of the difference in effects,Footnote

91

we find little evidence that lobbying increases the salience of the policy issue.Footnote

92

Future work could systematically vary salience or manipulate costs and benefits of a policy. While on salient policies, individual preferences are likely informed by partisanship, especially in highly polarized contexts, preferences are probably more easily shaped via outside lobbying on low salience topics.Footnote

93

Another avenue could be to investigate how individuals trade-off personal and societal costs and benefits of different policies.

Second, the differences in effectiveness of outside interest group messages across policy areas also raise the question which policies interest groups choose to become active on in the first placeFootnote 94 and which goals they aim to achieve via these public messages. According to our results, interest groups likely face trade-offs regarding the potential pay-offs from policies and the extent to which public opinion can be moved at all using outside lobbying strategies. Expectations regarding this trade-off likely informs their public strategies, as highlighted by existing work. While some research shows that interest groups that are highly affected by specific policies are likely to move first, as a means to increase chances of survival,Footnote 95 other groups might prioritize catering to the interests of their group members.Footnote 96 Other work based on interviews finds that interest groups might try to avoid trade-offs between policy-oriented and membership-motivated activities altogether and choose issues that aim to maximize payoffs along both dimensions.Footnote 97 Future work could leverage large data on outside strategies, such as social media campaigns, as well as data on membership activities, such as fundraising via public tenders or donations. In combination with available data on inside lobbying,Footnote 98 one could then investigate the timing of these activities around policy changes and investigate the extent to which these activities vary along policy dimensions such as salience, vulnerability, or popularity among group members. Thus, one could provide new answers to the old question of which interest groups become politically active, on which issues, and which strategy they choose.Footnote 99

Third, contrary to theoretical expectations, we find no evidence that broad coalitions of interest groups or costly signals, such as public protests, are more persuasive than messages from individual groups. Yet, observational studies show consistently that larger and more diverse interest group coalitions are associated with interest groups having more success in setting the agenda, attaining preferences in legislation, and in influencing regulatory rule making.Footnote 100 This could mean that interest group coalition signals affect policymakers and the public through different mechanisms, or that interest groups form coalitions primarily to affect policymakers, rather than the public. Similarly, the findings raise questions about the efficiency of costly outside lobbying strategies, given that generic messages without interest group endorsements perform just as well. Though empirically challenging, future work could further investigate these differences with parallel surveys of politicians and the public, to investigate how each group perceives and evaluates broad-based coalitions.

Finally, we provide tentative evidence for learning and social norms as mechanisms linking interest group’s outside messages and individual policy preferences using an IOT framework.Footnote 101 Future research could use different research designs to test these causal mechanisms, by directly including realistic treatments corresponding to these mechanisms. For example, one way to test the role of social norms could be to include a treatment factor with information about a public opinion poll with varying levels of public support for a policy in the population or the extent to which people in a country comply with the associated social norm. This would allow scholars to more directly which mechanisms interest groups need to tap in order to conduct successful outside campaigns.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2025.10018.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding statement

Jan Stuckatz—Funding from the European Commission under the Horizon Europe programme (Grant ID: 101105126) is gratefully acknowledged.

Heike Kluver—Funding from the German Research Foundation (Project no. 455518367) is gratefully acknowledged.

Kai Uwe Schnapp—Funding from the German Research Foundation (Project no. 455518367) is gratefully acknowledged