4.1 Introduction

Compared to the other countries in our sample, Denmark has experienced a relatively low rate of policy accumulation. Triage activity should thus be a rather rare phenomenon in Denmark. Yet, this expectation does not consistently hold across all the sectors and implementation bodies under study. First, although both central and local implementation authorities must deal with more or less the same number of environmental policies, the municipal environmental administrations (MEAs) display stronger triage behavior than the central implementation bodies. Second, such differences between central and local bodies are less apparent in the social sector. While the overall level of policy accumulation in social policy remains relatively low, numerous implementation tasks have been transferred from central to local authorities, particularly in municipal job centers (MJCs), resulting in a de facto increase in the work burden at the municipal level. Despite these shifts, we observe that the local level does not engage in more triage activities compared to the central level. This stands in marked contrast to what we observe in environmental policy.

To account for this variation and general patterns of policy triage, this chapter takes a deeper look at how the different mechanisms of overload vulnerability and overload compensation affect triage dynamics in central and decentral implementation settings. The analysis shows that local implementation bodies generally display a higher overload vulnerability than their counterparts at the central level, both in terms of their juxtaposition to political blame-shifting and lower opportunities for mobilizing additional resources. At the same time, however, this higher baseline overload vulnerability unfolds its effects in terms of policy triage to a different extent across environmental and social implementation bodies. While MEAs and MJCs display comparable levels of organizational commitment to overload compensation, MJCs are in a better position to escape political blame-shifting and to mobilize additional resources.

The chapter provides a detailed account of the patterns and variation of policy triage in Danish environmental and social policy implementation. To do so, it proceeds in the following steps. Starting with a structural overview of the policy implementation responsibilities and competencies in the environmental and social sector, we characterize the accumulation-induced implementation burden for each implementation body under study and present the differences in patterns of policy triage that form the research puzzle of the chapter (Section 4.2). Section 4.3 then addresses policy triage for the environmental sector, putting particular emphasis on the differences in triage levels across central and local implementation bodies. In Section 4.4, by contrast, we study policy triage in the social sector and particularly concentrate on the question why local implementation bodies surprisingly display less triage than their environmental counterparts. The chapter concludes with a summary of the findings and the key insights on policy triage in Denmark.

4.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in Denmark

Both environmental and social implementation structures in Denmark are based on the principle of decentralization, which emphasizes that governmental actions should be taken as close as possible to citizens and other stakeholders involved. Following the principle of so-called communal anchoring (kommunale forankring), the central government is responsible for securing and supervising compliance with policy implementation standards to ensure the same level of public services throughout the country (Hemme, Reference Hemme, Sommermann, Krzywoń and Fraenkel-Haeberle2025). It sets the fundamental policy objectives and overall administrative frameworks of policy implementation. Therefore, national administrations do not get involved much in the implementation “on the ground” (T. M. Andersen, Reference Andersen2011; DMEA, 2014). Rather, central-level agencies directly implement only selected parts of social and environmental policy. They do however engage in monitoring, benchmarking, and – at times – also in supervising the decentralized administration of national policy via their regional agency offices in Denmark’s five administrative regions (OECD, 2010; Vrangbæk, Reference Vrangbæk2010).

The overwhelming proportion of implementation tasks is thus carried out by the public administrations of Denmark’s formally independent ninety-eight municipalities (European Commission, 2018; B. Greve, Reference Greve2018). Within this decentralized framework, the concrete distribution of implementation task and the degree of central-level involvement differ according to procedural prescriptions, funding schemes, and reporting stipulations (DMEA, 2014).

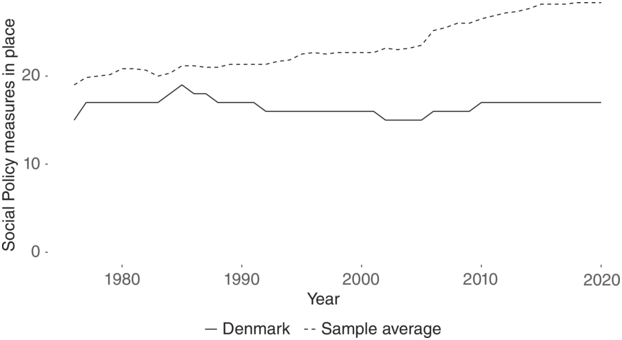

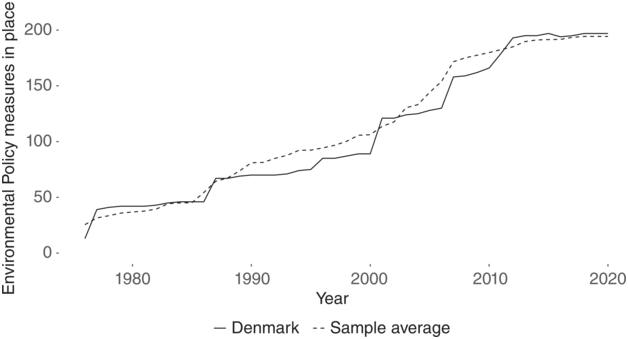

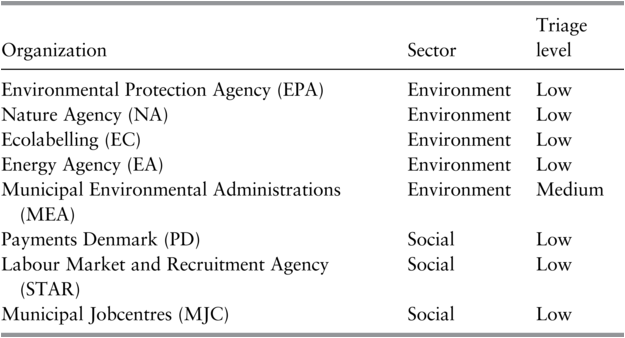

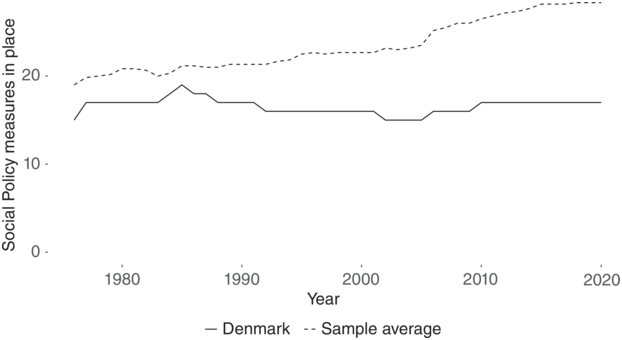

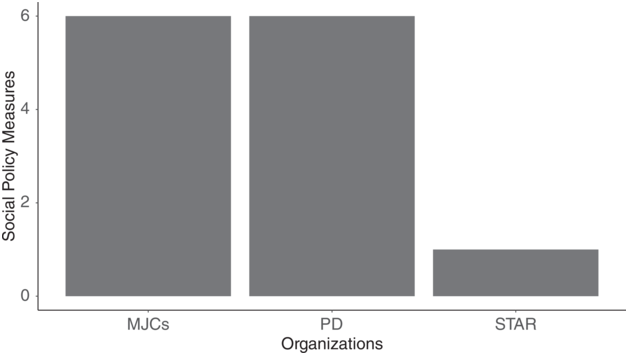

For both sectors under study, policy accumulation and hence the growth of the number of implementation tasks has remained at comparatively low levels (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2). In the social sector, de facto no policy growth dynamic is observable when taking the whole observation period into account: The social portfolio consisted of the same number of measures in 1977 as it did in 2020. While portfolio size fluctuations did take place, net growth is minimal. In contrast, the environmental sector experienced more dynamic portfolio growth, which largely corresponds to the average growth rate observed in the countries under analysis.

Figure 4.1 Social policy measures in Denmark.

Figure 4.2 Environmental policy measures in Denmark.

However, it must be noted that the changes in the respective sectors have not translated into an equal distribution of workload across the organizations involved. Rather, national agencies and local authorities have been impacted quite differently, as competences are unevenly distributed across implementing bodies. In the following, we thus take a closer look at the implementation arrangements of the two sectors under study and show how the growing implementation burdens associated with policy growth are allocated across these administrations.

4.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

In the environmental field, the decentralized nature of Denmark’s implementation structures is not as pronounced as in other policy areas due to the significance of national environmental agencies for municipal policy implementation (European Commission, 2019). While the overwhelming share of implementation tasks lies with the municipalities (May & Winter, Reference May and Winter2000), implementation arrangements differ depending on the respective central-level agency involved. Four characteristic task distributions can be identified.

First, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (Miljøstyrelsen; EPA) monitors and provides guidance for local implementation in the areas of water protection and nature and air quality control, based on the Environmental Protection Act, the Watercourse Act, and the Water Supply Act. Furthermore, the EPA conducts audits and on-site inspections of large industrial polluters. However, following a risk-based approach, the agency’s decentralized units in Slagelse and Aarhus only focus on “the most complex and potentially most environmentally harmful companies” (OECD, 2019: 99). Additionally, the EPA is responsible for the national licensing schemes for industrial and agricultural production processes and products as well as waste treatment activities (DEN07). It is also the “technical agency in charge of environmental policy implementation, monitoring, permitting and inspections” in relation to the Environmental Maritime Protection Act and the Coastal Protection Act (Basse, Reference Basse2020).

Second, selective cooperation between municipal environmental administrations and the Danish Nature Agency (Naturstyrelsen; NA) takes place regarding nature protection, conservation on state-owned land, as well as nature reserves such as Denmark’s six national parks. In parallel, the NA directly implements the Planning Act, the Act on Environmental Objectives, and several other laws regulating nature-related issues on public and private land (DEN09). Yet, for the most part, the agency “manages (…) forests and natural areas” in accordance with sustainable management objectives (OECD, 2019: 100). Concretely, the NA carries out national conservation planning and is responsible for flora and fauna monitoring, wildlife administration, control and licensing of hunting activities, as well as large-scale habitat preservation and restoration programs. The NA also registers the protected natural and wildlife areas to be developed, runs the National Forest Service, and supervises the national forest system with its twenty-five local forest districts (Basse, Reference Basse2020; OECD, 2019).

Third, there are local implementation arrangements coordinated centrally for national and municipal decarbonization projects led by the Danish Energy Agency (Energistyrelsen; EA). In addition to these coordination activities, the EA implements several air quality liability schemes and monitoring programs at large combustion plants directly. The Nordic Swan and EU Ecolabels are administered by Ecollabeling Denmark, a central-level agency (Sønderskov & Daugbjerg, Reference Sønderskov and Daugbjerg2011). In addition, a plethora of central–local partnership projects exist in areas of shared interests, usually involving additional public investments, European Union (EU) funding, or environmental planning and assessment (DEN07).

Fourth, as “public-private partnerships are not widely used by municipalities” (OECD, 2019: 100), the remaining practical environmental policy application processes for “specific tasks (…) and citizen-related tasks” are generally transferred into direct municipal responsibility and to a lesser degree devolved entirely (DMEA, 2014: 20). Particularly, the MEAs are solely in charge of administrating and enforcing municipal and local water basin and nature plans, control of air quality and waste treatment, as well as the related permit, audit, and inspection processes for small and medium-size enterprises. While these activities are formally based on EPA guidelines (OECD, 2019: 109), the agency’s actual implementation plans regularly require a lot of subsequent interpretation and adaption by municipal administrations. What is more, the local-level data required for central-level monitoring of municipal implementation efforts need to be compiled and fed into respective national databases by MEAs themselves (DEN02; DEN07; DEN08).

The distribution of implementation burdens mirrors this allocation of responsibilities. At the central level, the bulk of accumulation-induced implementation burdens remain with the EPA, whereas the NA and the EA focused more on economic issues related to environmental policy. Recently, however, this task distribution has changed tremendously as a move from “close to nature forestry to untouched forests” has affected the NA’s implementation tasks (DEN03). In addition, Denmark’s generally “huge political ambition on climate change” increased implementation burdens for the NA (DEN18). Equally, continuous expansion of information-based policy instruments translates into “a lot of workload” for Ecolabelling Denmark (DEN04).

In case of the EA, these new policy developments brought about by the Climate Act, the Energy Islands Project, and the New Energy Agreement, among others, exponentially increased legal and regulatory complexity (DEN12; DEN24). New tasks not only implied increases in workload but also entailed a “growing attention on delivering,” thereby increasing the “demands on what else (…) [EA staffers] are supposed to think of” when implementing (DEN18). What is more, new legislation initiated a fundamental reform of the EA’s traditional policy orientations: While implementation tasks tended to be straightforward “15 or 20 years ago,” the agency’s responsibility “triangle between energy, economics, and climate change” has been significantly altered since “climate change (…) [was set] as the overall framework” (DEN24). In addition to assigning a completely new range of tasks to the EA’s portfolio, this change in the policy framework also initiated a series of ongoing politicized efforts in administrative reform and organizational restructuring, placing additional stress on the EA. Although the importance and work intensity of some older implementation tasks decreased in the process, the EA’s absolute workload increased nonetheless (DEN24).

In case of the NA, in contrast, the net number of implementation tasks has not risen significantly in recent years despite new policy initiatives such as the Nature Package or the National Forest Programme being added to the agency’s portfolio. Yet, at the same time, the NA witnessed a pronounced shift in organizational priorities: The paradigmatic shift from an implementation focuses on “balancing forestry, recreation, and nature” toward “nature as the highest priority” massively increased the agency’s workload even though no significant amount of new legislation affected the agency’s implementation load (DEN03). “The yearly growth, on average, and the increase in complexity of the tasks we have to perform, has been more or less constant” (DEN10). However, beneath this picture of incremental expansion and overall continuity, a “massive revolution” has taken place. Even without “enormous changes in policies,” there have been “dramatic changes” regarding tasks to the extent that “you will find nothing of what (…) [the NA did] 30, 20 years ago that (…) [it] would [still] be doing today and those changes mean a lot of work” (DEN10).

Turning to the EPA, workload has already been high because of the tasks specified in the existing stock of ambitious environmental policies and burdensome implementation processes (DEN02). Adding to these implementation tasks, dating back to the establishment of Danish environmental policies and several “pioneering” action plans (Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2001; Kørnøv et al., Reference Kørnøv, Christensen and Nielsen2005; Liefferink & Wiering, Reference Liefferink and Wiering2011), two developments translate into a massive extension of implementation tasks. First, the “increase in the scientifically complex nature” of policy initiatives and regulatory processes requires “a new kind of very complex discussions” where implementation details have to be coordinated among three different actors, “the European and national level and within the agency” (DEN01). Second, “there is a procedural increase [in workloads], because the [ensuing] regulation is [still] very broad (…) [and] not detailed as such at the overall level” (DEN01). This leads to a significant proportion of EPA staff constantly “working on new guidance” on how to apply novel criteria and standards in practice. Ultimately, “more and more issues tend to end up at legal services” (DEN01), putting significant strain on parts of the organization. Because of these developments, the EPA now faces a situation in which “the complexity has just gone through the roof” (DEN01). Even supposed minor tasks such as a “renewal procedure of an approval to be conducted every five to ten years” were inflated to match or even exceed the workload of the original evaluation (DEN01).

However, despite these burden increases at the central level, the environmental departments of the ninety-eight municipal administrations cumulatively have been hit the hardest by environmental policy accumulation. Due to the decentralized nature of implementation in Denmark, local-level MEAs already carried the larger part of the historic implementation burden (DEN08; May & Winter, Reference May and Winter2000). In 2007, the Structural Reform (Strukturreformen) transferred administrative competences for river basin, groundwater, wastewater management plans, and all citizen-related environmental implementation duties into sole municipal responsibility (OECD, 2019). Policy implementation – previously often handled in tandem with the central-level agencies – fell exclusively upon the MEAs in the past ten to fifteen years (DEN08). Although reforms in 2013 and 2015, respectively, reduced the prescribed processing times for environmental permits and relieved MEAs of some minor responsibilities for landfill permits and raw material extraction (OECD, 2019: 26), all municipal interview partners stated that the administrative burdens did not decrease significantly (DEN07).

Rather, workloads seem to have expanded massively post 2007 (DEN11; DEN08). Especially regarding MEAs’ implementation tasks in the water and nature protection subsectors, implementation burdens are “growing year to year” as “layer after layer is added (…) and nothing goes away” (DEN06). Mirroring policy developments and challenges at the central level, municipal implementation processes in a similar vein have become “very complex” (DEN07) and “rigid with all the paperwork,” that MEA staffers describe their work situation as plagued by “doing bureaucracy down to everything” (DEN08).

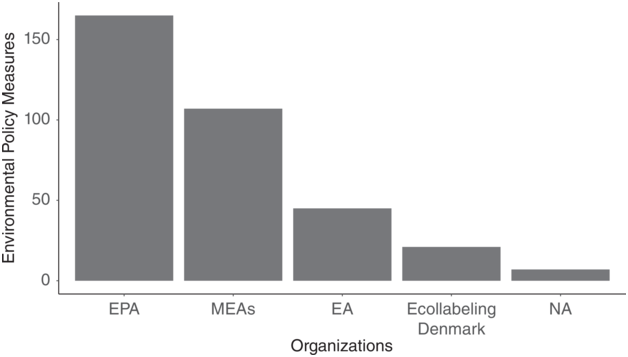

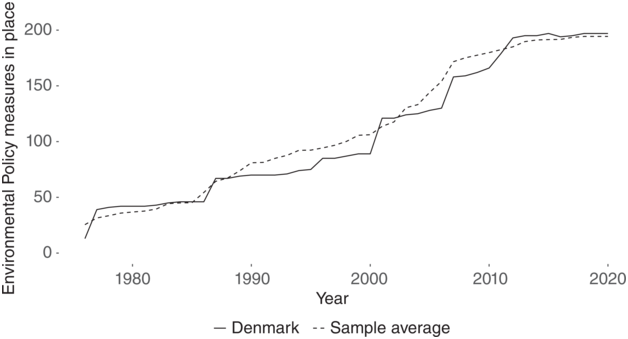

Figure 4.3 illustrates how the distribution of environmental implementation tasks across different administrations evolved over the past twenty years. It is clearly visible that national agencies and MEAs have both been affected by the increasing workload emerging from the accumulation of policies, with the latter municipal authorities bearing the brunt.

Figure 4.3 Distribution of implementation tasks in environmental policy.

4.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in Social Policy

Social policy implementation is also highly decentralized in Denmark. Built on the fundamental distinction between universal social services for eligible recipients and means-tested social assistance for special claimant groups, implementation arrangements follow two different task distributions (Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012; DMEA, 2014): On the one hand, there is the state system dealing with pensions and unemployment benefits for employed people that made prior payments to the twenty-four private and state-approved insured funds, called A-Kasser (Lind & Hornemann Møller, Reference Lind and Hornemann Møller2006: 9). The system is administered independently by Payments Denmark (Udbetalling Denmark; PD), the central-level agency responsible for handling “all transfer payments that are fully specified by legal regulation” (Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012: 60) as well as most cash benefits paid directly to Danish citizens. More precisely, PD pays out Danish “family subsidies [including child allowances], maternal benefits, [universal old age and disability] state pensions, early retirement benefits and [housing as well as] rent allowance” (DMEA, 2014: 23). It does so practically without any direct client interaction using a completely automatized IT system (Madsen, Reference Madsen2006; OECD, 2010; DEN05).

On the other hand, administration and payment of all means-tested social pensions and benefits, for example, for the uninsured and the (previously insured) long-term unemployed are executed by the social departments of municipal administrations without direct central-level involvement (Lind & Hornemann Møller, Reference Lind and Hornemann Møller2006). Accordingly, the municipal level is responsible for all tasks relating to social security, unemployment services and benefits, active labor market policy, and the additional social assistance funds for special claimants (Larsen & Wright, Reference Larsen and Wright2014; DEN17; DEN16). Most of these implementation tasks are performed by local “one-stop” job centers (Jobcentre; MJC). MJCs have full responsibility for “checking the eligibility for and paying social assistance, advising on job search, career and vocational guidance, checking availability for work, (…) placing unemployed clients into jobs (…) and employment promoting programs” (Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010; Winter et al., Reference Winter, Dinesen and May2007).

The Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment (Styrelsen for Arbejdsmarket og Rekruttering; STAR) monitors and supervises MJCs, placing particular emphasis on their two main functions: retaining workers in the labor market and the provision of a skilled workforce. STAR conducts a benchmarking process based on the data on local activation measures and job counseling as well as placement quotas gathered by MJCs for the national measurement system jobindstats.dk. In this context, the agency also carries out regular performance audits to evaluate MJC’s overall implementation efforts. In addition, it offers voluntary central–local partnership projects in areas of shared interest that include “separate earmarked state funding.” The agency also provides support and guidance to MJCs to locally improve “those areas where more efficient efforts are needed” (Hendeliowitz, Reference Hendeliowitz2008: 17). Should an MJC continuously miss performance targets on a large scale, STAR may send inspection teams or task forces. In the most severe cases, STAR can relieve the organization of its duty of implementing national employment policies and outsource it to private service providers instead (Bazzani, Reference Bazzani2017). Yet, this remains a hypothetical scenario as such severe modes of intervention have not been deemed necessary so far (Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010; DEN20; DEN15).

Historically, several reforms have placed a greater burden on the municipal level compared to the central level.Footnote 1 The decentralization of additional implementation responsibilities, initiated by the 2007 Structural Reform, once again significantly increased the burden on local implementers (cf. B. Greve, Reference Greve2012; Kananen, Reference Kananen2012). At that time, MJCs essentially were “invented in their current form” (DEN16). In 2009, the implementation of unemployment policy was transferred entirely to the local level, following the disbandment of the state employment service (DMEA, 2014). Ever since, MJC workloads are considered “too high” (DEN19) as increasing the number and complexity of implementation tasks is “an ongoing thing” (DEN20) “that (…) is getting worse (…) every year” complicating street-level implementation (DEN23). While no new social policies were actually adopted (see Figure 4.1), several changes within the existing set of policies implied a substantial increase in the implementers’ workload. Especially, the numerous “tiny” legal or administrative changes with “short deadlines for implementation” (DEN22), along with the practice of “dividing the unemployed into [up to 14] (…) subsections (…) with a separate registration process,” cumulatively placed immense pressure on MJC staff. This led to a situation where “enormous numbers of rules and procedures” had to be met for each individual process (DEN20; DEN19; DEN21) and the MJC “had to implement reforms all the time” (DEN19).

In response to these changes, the PD took over the administration of payments for all universal social services in 2013, relieving the MJCs of these duties. However, other labor-intensive tasks remained at the municipal level. These include client advisory services, decisions on early retirement benefits, health benefits, and other aspects of more individualized case handling that require personal assessments and involvement (DMEA, 2014). In fact, some interviewees argued that arriving at a more efficient distribution of responsibilities while “skipping quite a few [procedural] rules” (DEN19) proves to be merely another source of increased local complexity (DEN16): Now, there are very “different types of models that (…) [MJCs] are obliged to use” but “do not speak together” (DEN19). This, in turn, has created a significant amount of additional work for municipal administrations, requiring them to develop their own employment policies and compensate for the lack of a national framework (DEN21).

While implementation burdens and complexities are thus “not exponentially, but still (…) steadily growing” at the municipal level (DEN22), the central agencies experience a completely different workload development. Although increases in implementation burdens are “in general (…) a pattern” that PD staff “can recognize,” very incremental increases in the range of tasks have been accompanied by reductions in the general “complexity of administration” that have kept total workloads “pretty stable” (DEN05; J. G. Andersen & Carstensen, Reference Andersen, Carstensen, Golinowska, Hengstenberg and Zukowski2009; Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005). For instance, despite legislative changes in PD’s client interaction IT system creating “a lot of work,” the agency encounters none of the procedural and operational pressures reported on the municipal level (DEN14; DEN13). Essentially, central agencies profited far more from regulatory simplification and decentralization initiatives advanced since the mid-2000s (T. M. Andersen, Reference Andersen2011; Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010). In case of STAR, for example, support services to MJCs were largely replaced by comparably passive monitoring and surveillance tasks (DMEA, 2014). A recent “shift from legislative control to more economic management” (DEN15) led to additional reductions in the agency’s workload. By means of an elaborate automatized benchmarking process, for which MEAs provide data directly, municipal implementation of social policy for the most part are essentially monitored and supervised automatically (DEN15). Accordingly, STAR’s workload and tasks are “fluctuating, but on a steady level” (DEN15). Rather than trends of social policy accumulation, the central aspects determining overburdening lies with the changing tides of politics and the economy (DEN17).

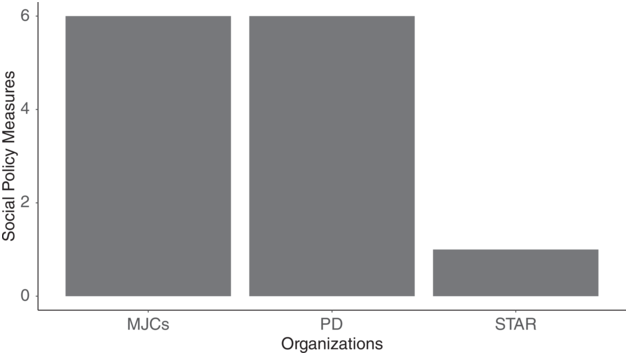

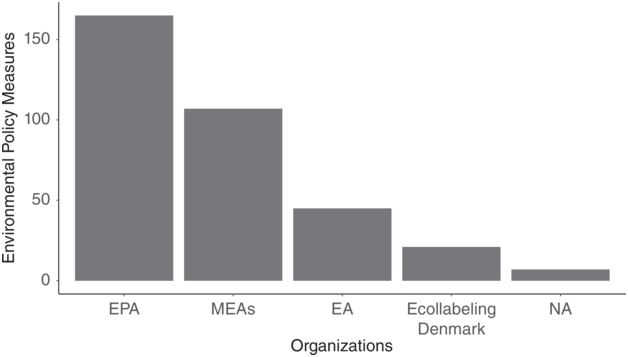

Figure 4.4 illustrates the distribution of social implementation tasks across different administrations. It is clearly visible that implementation burdens land predominantly on the municipal level and PD. In addition, the previous discussion has shown that some work burden increases that municipalities must deal with in social policy go unnoticed by our coding schemes, which focus on broader implementation tasks. However, several policy changes have made these tasks more difficult and burdensome, beyond merely increasing their number.

Figure 4.4 Distribution of implementation tasks in social policy.

4.2.3 Puzzling Variation of Policy Triage: Two Unexpected Differences

Summing up the findings of the two previous sections, one may conclude that growing policy complexity and accumulation have impacted different parts of the Danish administration in varying ways: Due to extensive decentralization efforts, municipal administrations are affected to a far greater extent than national ones. At the same time, overall workload and task complexity also have increased remarkably for the national environmental organizations – EPA, NA, and EA – notwithstanding the fact that central-level agencies usually do not play a major role in implementation on the ground. In addition to the increasing complexity of tasks, local organizations responsible for implementing environmental policies are also affected by decentralization as they are burdened with duties that formerly rested with the central agencies. Turning to social policy, the absence of policy accumulation suggests that central and local agencies in this realm should not be challenged by rising implementation burdens and consequently display little to no signs of policy triage. Yet, as decentralizations unburdened central agencies, more work fell to the municipal-level job centers. In addition, several adjustments within the setting of existing policy instruments have increased the workload for the social administration at the local level. STAR and PD, by contrast, are the main profiteers of regulatory simplification and the automatization of routine tasks.

In summary, the observed patterns of workload increases and their unequal distribution should result in pronounced differences in policy triage patterns across various institutional levels and policy sectors. First, when comparing policy sectors, policy triage should become more evident for environmental than for social policy, as policy accumulation has been much more pronounced in the environmental field. Second, given the fact that in both sectors local authorities must carry the larger part of implementation work, we should expect that triage is more likely to occur at the local level rather than at the level of central agencies. Third, following on from the previous point, one would expect both MJCs (local social) and MEAs (local environment) to display comparable levels of policy triage activity, given the observed workload increases.

Yet, as demonstrated later, none of these expected patterns can be observed empirically. Despite increases in workload, complexity, and task intensity in the environmental field, policy triage is largely nonexistent in all central-level agencies. At the same time, we find pronounced variation in triage patterns at the local level. MJCs do not engage in policy triage, whereas MEAs exhibit noticeable triage behavior. Policy triage at the local level is becoming more frequent and severe in environmental policy. Given that national agencies manage a smaller portion of the Danish social policy portfolio compared to local administrations, their solid performance is not particularly surprising. What stands out in the social policy sector, however, is the MJCs’ ability to avoid resorting to policy triage entirely, despite facing challenges from task decentralization and the increasing complexity of existing provisions.

This leads to two puzzling and unexpected differences in the Danish case: First, why is it that the national implementers – EPA, NA, and EA – do not engage in significant triage activity, while MEAs clearly display such behavior, even though both are burdened by a significant level of accumulation in environmental policy? Secondly, why are MJCs able to avoid the increasingly frequent and severe triage decisions faced by local implementers of social policy? In Sections 4.3 and 4.4 we address these questions in greater detail.

4.3 Good at the Top, Mixed at the Bottom: Variation of Policy Triage in the Environmental Sector

The implementation of environmental policy in Denmark is based on a division of tasks between central agencies and the municipalities. Although implementation burden grew for the relevant organizations at both institutional levels, problems of overload and resulting triage strongly vary between central and local bodies. In this section, we show that these differences not only result from different degrees of overload vulnerability of central and local organizations but also from differences in their commitment to overload compensation.

4.3.1 Policy Triage in Environmental Policy Implementation

As indicated, Danish central-level environmental agencies hardly display implementation deficits in terms of severe or frequent incidents of policy triage. While small-scale prioritizations and selective postponements happen from time to time, triage does not prevent central agencies from “figuring out how to solve everything in a satisfying way” (DEN18). Despite the rare emphasis on triage activities to “take away tasks that are not politically wished for or wanted” by the respective minister and top management (DEN10; DEN02), national implementers generally prioritize to fulfill what is considered to have the “most impact” for policy effectiveness in their area of competence (DEN12; DEN03; DEN18; DEN02; DEN04).

Triage decisions occur, if at all, in the context of selective incidents only. Trade-offs are made if the administrative “flexibility” to extend deadlines or delay tasks is already legally bestowed upon the implementing national agency and can therefore be attained easily, for example, simply by prolonging already verified and controlled prior certification and licensing processes (DEN04; DEN01). Second, triage occurs if implementation delays merely violate the “internal deadlines” (DEN02) for “extra things” that have not been previously specified in the legislation but were added during the implementation process and can easily be taken up again afterwards (DEN09). Finally, triage may be needed when conflicting goals within a single policy require prioritizing the most important parts by reducing efforts on less critical aspects (DEN12). However, even in these latter cases, triage decisions are made only for short periods following legal changes, shifts in responsibilities, or sudden external events (DEN10; DEN12; DEN02; DEN03; DEN04).

Consequently, in all central agencies, policy triage only relates to “very specific” (DEN04) implementation activities that are of little consequence to implementation processes (DEN02; DEN10; DEN12). Hence, what gets down-prioritized or postponed is usually only occasionally and temporarily reduced to very similar implementation tasks of a generally “adjuvant” nature, such as providing more sophisticated internal analysis to assess policy impacts (DEN04; DEN18); commenting on international policy developments (DEN02; DEN12); updating agency websites and informing citizens and stakeholders; or integrating technical expertise “on what might be a problem” and participating in debates on conflictual “offensive issues” (DEN02; DEN09). Overall, the need for triage activities in environmental policy implementation is generally low for central-level agencies.

Denmark’s MEAs, by contrast, display signs of frequent and increasingly severe triage activity in terms of the nature of neglected implementation tasks and the consequences associated with such behavior. Four implementation deficits are of particular significance.

First, MEAs on a very general level do no longer comply with many of the processual benchmarks that “typically [prescribe] the amount of time (…) to be spent on a certain subject” (DEN07). In effect, deadlines must be postponed “all the time” (DEN07). Yet, while deadlines can be delayed rather easily for most implementation targets, some of them such as the deadlines tied to EU policies, crucial national initiatives, or funding-related ones, cannot be (endlessly) postponed. Consequently, MEAs deal with an ever-growing pile of delayed implementation tasks and often find themselves in situations where they must tackle large, non-relocatable projects simultaneously with the implementation of other pressing, non-relocatable policies. “Facing the limit” of previous and current triage decisions, MEAs ultimately have no choice but to “end up not doing some things” after already handling other tasks more slowly (DEN06; DEN08).

Second, because of this “vicious cycle” (DEN08), there is an overall struggle of simultaneously fulfilling many administrative and procedural requirements prescribed by national and EU laws for municipal implementation plan interpretation, adaptation, and subsequent execution. This is getting especially rampant in areas of water protection and nature conservation, where MEAs face “very big challenge[s] (…) to finish (…) projects at the right time and deadlines,” which then leads to deteriorating performance of other adjoining mandatory implementation tasks (DEN06; DEN07). For instance, one MEA staffer elaborated that of almost 500 kilometers of river courses in their municipality, which would have to be controlled by walking along them twice a year, the unit responsible in fact only manages to do so once a year for “maybe five kilometers to check how much water is running” (DEN11). Such singular statements on “must-do-job[s], (…) that [MEAs] just do not do anymore” (DEN11) are corroborated by formal notices sent to Denmark for infringement of EU legislation due to several problems with important EU Directives, including those on drinking water, wildlife conservation, waste incineration, environmental assessment, and air pollution. Each of these problems can be attributed, at least partly, to an increasing reliance on policy triage (Liefferink & Wiering, Reference Liefferink and Wiering2011: 8; cf. OECD, 2019: 103).

Third, focusing implementers’ attention on whatever “has the main priority [right] now,” the EU Water Framework Directive, for example, immediately brings about diametrical “consequences (…) for other environmental tasks with lower priorities” (DEN06). While these trade-offs relate to MEAs’ “specific tasks” and decentralized national or EU projects, average processing times for municipalities’ citizen-related responsibilities have been affected as well. Implementation tasks that cannot be considered to be of a merely adjuvant nature at the municipal level, such as the communication with private landowners, handling citizens’ requests, or initiating cooperative projects are therefore increasingly neglected. Juggled alongside “hard” administrative and procedural requirements and adjoining mandatory implementation tasks, these “softer” activities now equally take “longer to be implemented,” meaning that “people (…) need to wait longer for decisions” (DEN06; DEN07). MEAs thus often find themselves unable to do more, as they need to first “finish something [in order not to become] totally overloaded” (DEN11) and – when in such situations – will always prioritize delayed tasks and such that cannot be delegated.

Finally, MEAs struggle to uphold previous procedural benchmarks for permitting, auditing, and inspection operations. In the words of a MEA staffer, “we would like to do it 100% correctly” but “nowadays, it may be [only] 70 or 80% [that we are able to do so] because” here, too, “we do not have the time to do it proper” anymore (DEN11). For instance, when it comes to on-site controls at the small and medium-size enterprises in one municipality, the MEA unit responsible “do[es] not even look at wastewater” anymore, because industrial sewage is carried to the municipal water treatment plant anyway, so pollutants can be detected there.

While none of these instances of triage constitute severe procedural violations, pertain to critical environmental tasks, or affect key policy design principles so far, they increasingly undermine the principles of decentralized implementation. Although MEAs’ triage activities so far predominantly involve significant prioritization, which often results in delaying actions that are not anticipated to become major environmental issues, the risks associated with potentially “prioritizing too much” are escalating, and consequences are starting to emerge (DEN08). Whether still manageable or not, the structural inability to comply with procedural benchmarks has developed a momentum of its own. Triage patterns are now affecting underlying decision-making routines, leading to attitudes and behaviors such as being “as gentle in enforcing […] [the law] as possible” (DEN07), navigating decisions based on potential repercussions – “if you do not do this, how much trouble do you get” (DEN11), and prioritizing tasks into “things […] you have to do […] and the other things that you can do if you have time” (DEN11). Additionally, there is a focus on maximizing efficiency, highlighted by efforts to get “the most environment for the money” (DEN08) and “the most value according to the overall goals of the legislation” (DEN07). In effect, MEAs prioritize efficiency over effectiveness in their decision-making processes (DEN06).

To summarize, environmental implementation deficit prevalence is rising even though MEAs continue to “do quite well overall” (DEN07) and feel, at least for the time being, “very much in control” (DEN11). However, what until recently were small-scale deficits that did not yet apply to overall processes or broad task dimensions of practical policy application (DEN06), must now be characterized as triage activity on a medium level. Local implementation deficit prevalence clearly risks developing into “a big problem,” if “things do not get better in five years” (DEN11). MEAs are increasingly “reaching the bottom, and now (…) start digging holes that (…) [they] cannot get up out of” (DEN08).

4.3.2 Different Overload Vulnerability of Central and Local Organizations

The described variation in triage patterns results from pronounced differences in the overload vulnerability of environmental implementation bodies at the central and local level. These differences become apparent not only in terms of political blame-shifting but also in opportunities for mobilizing external resources.

Blame Attribution for Implementation Failure

The strong constitutional rights of municipalities to handle their own affairs independently facilitate national policymakers to shift the blame for implementation failures to the local level. This may be exemplified best in the paradoxical allocation of fiscal responsibilities between central and local levels. Due to the pronounced financial autonomy of municipalities, the national level bears minimal cost for municipal environmental policy expenses but effectively defines the scope of measures. Even in cases of partial refunding, national policymakers have no control over either the allocation of indirect budget transfers or the distribution of municipal tax revenues. So national policymakers can blame MEAs’ triage activity on local cost-cutting measures, while effective political responsibility for fiscal relations and budget parameters firmly rests in national hands. These problems in accountability relations have been criticized as national policymakers appear to fulfill citizens’ demands, while irresponsibly “squeezing” less economically developed and peripheral municipalities (DEN08; cf. Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012).

The obscuring orientation of national–municipal delegation structures has been worsened by the 2007 Strukturreformen. As a result of devolving further uncompensated implementation tasks for which “municipalities were not (…) well equipped” (DEN07), well-established political–administrative arrangements marked by clearly demarcated or shared responsibilities were terminated (see also Pedersen & Löfgren, Reference Pedersen and Löfgren2012). In addition, the Structural Reform limited more informal involvements of national policymakers by abolishing environmental county administrations and by downsizing regional NA, EA, and EPA offices. The reform also further deflected national responsibilities for funding by shifting calculation bases of government block grants to apolitical “municipal expenditure needs” and brought less national involvement in the structure of oversight (DEN08; cf. Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012), implying that the EPA’s street-level presence is “very, very understaffed” up until today (DEN08; European Commission, 2019; Vrangbæk, Reference Vrangbæk2010).

Regarding national environmental agencies, political opportunities for blame-shifting are much more limited. Even though delegation to semiautonomous arms’ length agencies constitutes the predominant form of organization in Danish central government, it “does not affect the unitary principle of ministerial accountability” (OECD, 2010: 55). Political responsibility runs hierarchically from the EPA, EA, NA, and Ecolabelling Denmark to the policymakers in the line ministries. Consequently, it is difficult to credibly shift blame for (potential) implementation deficits to implementing agencies (DEN02; DEN03; DEN18; DEN04). Moreover, Danish ministers “have an extensive right to decide autonomously on how to implement (…) within their policy area.” They are “accountable to the cabinet’s Coordination Committee, which is chaired by the Prime Minister” (OECD, 2010: 102; DEN01).

As a result, national implementation tasks related to environmental issues – such as biocides (DEN01), biodiversity (DEN10), the Energy Islands (DEN12), watercourses (DEN02), and national parks (DEN03) – are “so much on top of the agenda” that there is now a significant “demand and growing attention on delivering” from which the policymakers can no longer hide (DEN12; DEN24). The soundness of limitations for blame-shifting is best exemplified by several high-profile resignations of prominent Danish ministers occurring in recent years. Each one happened after being blamed personally for neglecting minor ministerial duties in respective areas of competence (DEN24; DEN02). Although concrete delegation structures for each central-level agency may differ, national policymakers cannot deflect blame for environmental agency implementation (OECD, 2019).

Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

There is a second very pronounced difference between central- and local-level implementers when it comes to overload vulnerability, which results from different opportunities to mobilize additional resources. These opportunities are rather limited for MEAs compared to the extensive clout of the central-level agencies. Municipal implementers thus are left with far less opportunities to influence national environmental policies and resource allocations – despite overall high levels of articulation and formal and informal consultation in Denmark (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b).

While local implementation bodies might have marked abilities to form and articulate a unified opinion and convey their concerns to policymakers during the policymaking process (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b), a number of particularities undermine the impact of these overall opportunities regarding resource mobilization.

First, there are no sector-specific mechanisms of consultation allowing MEAs to present their concerns and positions to national policymakers directly (DEN06; DEN08). While direct interactions with central agencies exist, they usually unfold on either a special implementation plan or voluntary project basis (DEN02; DEN07; DEN08). Thus, although central agencies ask the local level for feedback on prospective policy, consultation is perceived as being “just pro forma” as street-level concerns are “not taken into account anymore” (DEN08). Especially after the 2007 structural reforms, it has become “quite difficult to be precise and to communicate precisely the difficulties between the municipality and governmental offices,” as “there is a lack of mutual understanding on both sides” (DEN07; European Commission, 2019; cf. May & Winter, Reference May and Winter2000: 152 ff.). Consequently, while consultations are taking place, they are not perceived as effective by local implementers due to a lack of mutual understanding (DEN11).

Second, to have their voices heard at the national level, MEAs must rely on sophisticated means and strategies for municipal interest representation. This involves convincing local councils and governments of their concerns and positions and then winning support from most municipalities across five administrative regions. Only then can they approach the national association of Danish municipalities, Local Government Denmark (Komkunernes Landsforening; KL), to raise their issues in the meetings on general municipal matters that KL regularly holds with national policy producers (DEN08). However, this endeavor is challenging for the ninety-eight MEAs, as it requires significant political effort from what are primarily administrative organizations (DEN07; DMEA, 2014: 18; B. Greve, Reference Greve2018). Despite the efforts of municipal politico-administrative leaders to protect and assist MEAs, they receive little support from the central level, as national policy formulators appear uninterested in the feedback gathered from the ground level (DEN08). They have different priorities, and the big picture tends to remain unchanged (DEN07). Successfully highlighting the local capacity problems of MEAs to the central level through municipal interest representation is not a common experience for MEA staffers (DEN06).

In summary, despite Denmark’s status as an archetypal consensus democracy that emphasizes coordination and integration, its environmental implementers appear to be caught between two contrasting tendencies: decentralization and centralization (C. Greve, Reference Greve2006: 162). Environmental policy formulation at the central level is strongly separated from policy implementation, where the large part of the burden is carried by the lower levels of government (Liefferink & Wiering, Reference Liefferink and Wiering2011). This implies that compared to central agencies, municipal implementers are put in a more vulnerable position by the restrained degree to which they can actively employ strategies to mobilize external resources (Blöndal & Ruffner, Reference Blöndal and Ruffner2004; OECD, 2019). While central agencies “have a good financial chance to achieve the goals that (…) [policy formulators] have put on the organization[s]” (DEN10), this cannot be asserted in case of the MEAs: they have trouble acquiring resources from both, the superior municipal councils and the central level. Although municipalities generally “play a major financial role,” as evidenced by their local government expenditure making up 37 percent of Danish state expenditure totals – more than three times the EU average (S. Bach & Bordogna, Reference Bach and Bordogna2013; Mailand, Reference Mailand2014) – this financial clout, along with their “extensive” tax rights and total budget autonomy, does not necessarily produce favorable conditions for MEAs (Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012; OECD, 2010: 126). Rather, “everybody is fighting for the money” (DEN11). What is more, the central-level policy producers do “not put the money into what (…) [implementation tasks have] been agreed on in the EU” as well as the national level (DEN08). MEAs therefore tend to merely get “what money is left” (DEN08) in local budgets after politically more salient areas of municipal competence have been provisioned.

This is reinforced by the fact that the municipalities’ vast fiscal powers of disposition entail three important downsides when it comes to funding environmental implementation tasks. First, MEAs compete for fiscal resources with local implementers from almost all other areas of municipal competence. However, as “the state (…) dictates how much money each municipality must spend on citizen services” (DEN08) but not for environmental issues, MEAs usually are disadvantaged in local budgets. Second, getting compensated for devolved implementation tasks proves equally challenging. Despite conducting the bulk of implementation on the ground, no formal funding arrangement exists that would allow MEAs to tap into the comparably vast central agency budgets directly (DEN08; DEN06). Third, additional government funding is only available to the MEAs in relation to national environmental initiatives, which, however, often come with further task responsibilities (DEN06; DEN11).

Acquiring funds indirectly by tapping into the general government transfer and equalization funds in turn is beset by the same local troubles of budget infighting and resource balancing ever since “the state financing has changed from activity-related subsidies or reimbursements to black grants the municipalities can distribute freely” (DMEA, 2014; OECD, 2010: 126). Besides, grant disbursement has been increasingly tightened and controlled in recent years with the introduction of binding financial agreements (Økonomiaftale) (Mailand, Reference Mailand2014; Niemann, Reference Niemann, Geißler, Hammerschmid and Raffer2019). One interviewee summarized the state of local budget allocations as follows: “politicians and top-level administration (…) seem to be aware [of] why environmental legislation is made, but when it comes to the enforcement of the laws, they become disinterested and allocate nothing to it. There is a gap between what they say and what they are doing (…) [at least] when it comes down to handling the policies locally” (DEN08). The MEAs get “more and more tasks, and fewer persons” and financial means to fund them (DEN08; DEN11).

In contrast, staffers from EPA, EA, NA, and Ecolabelling Denmark reported having consistently strong opportunities to mobilize external resources by influencing policy formulators throughout the policy and budgeting process. This formalized inclusive practice of intense internal communication is evident in the series of regular “small” meetings and quarterly “big” meetings focused on work programs, budget allocation, and task prioritization. These meetings occur on “a constant basis” both within each agency and in coordination with the ministries (DEN24). Following a “clear logic (…) to keep an eye on all costs and work problems” (DEN24), these meetings provide an “open situation” in which the agency staffers are explicitly asked by respective superiors whether they feel overloaded (DEN24); “if the answer is ‘yes’ (…) then there is a process to find out what is most important and everybody is participating in that and talk[s] about things in a creative manner” (DEN24; DEN02). The results of those internal consultations are then relayed to “inter-ministerial committees (…) made up of ministers and usually assisted by mirror committees of high-level officials” (OECD, 2010: 53). These committees then formally provide organizational feedback to the cabinet’s top Coordination Committee chaired by the Prime Minister (OECD, 2010: 54, f., 102).

Consequently, staff members of all central agencies noted that they “get quite a lot of backup” and experience “quite a lot of understanding and leniency” from superiors (DEN12) who tend to be “responsive” and “content that we tell them about (…) problems” (DEN02). Regarding political superiors, the “very good and close dialogue with the ministry,” too, “goes both ways” and “everybody is very much on the same planet” (DEN04). In sum, the dialogue between the central agencies and their line ministries does “not [unfold] top down,” but as “an open and fair discussion” (DEN10). National implementers can thus “definitively” point to capacity as well as financial and staff resource problems should they encounter any (DEN02; DEN18). Although the national agencies would strictly rely on “closed conversations” with their ministerial superiors rather than voicing political demands actively “to outsiders” in parliament or the media (DEN18; DEN02; DEN03), central agencies’ political voice can be considered exceptionally high (OECD, 2019).

Central implementation bodies are thus able to actively mobilize external resources in two ways (DEN01; DEN12; DEN03). The first is via the regular budgeting process, culminating in the “big financial bill” that is based on a budget proposal passed by parliament (European Commission, 2018). Central-level budgeting in Denmark generally follows a very orderly and regulated prioritization process. This is achieved by asking agencies where they need more resources and where there is a need for improvement (DEN18; DEN12). This process involves collaboration within the agency, exchange with and within its respective line ministry, and, finally, between that ministry and the Ministry of Finance (DEN18; DEN12; European Commission, 2018). The second way to offset for increased workload by mobilizing additional resources at the central level is a more top-down budgeting process used to finance new implementation tasks that are added to an organizational policy portfolio between fiscal years. This process typically involves the Ministry of Finance from the start, often based on an official cabinet decision or the political initiative of high-ranking members of government (DEN18).

In Denmark, there is a “general understanding that policies have costs” (DEN10) and that administrative costs as well as policy costs need to be covered by central-level policymakers, in particular for national agencies (DEN09). While agencies do not have unlimited resources at their disposal, there is a shared understanding that funding for “adequate implementation” (DEN24) is important and that increased resource demand due to policy accumulation and task intensification needs to be addressed. Even though the Ministry of Finance is “solely in charge” of the budgeting process for each agency (European Commission, 2018: 227), budget proposals are generated in a coordinated manner, involving “back and forth” discussions, and are presented to policymakers who usually agree on them (DEN12). As a result of the Finance Ministry’s “efficient budgetary mechanisms” (European Commission, 2018: 227), the environmental agencies “have a good chance to achieve the goals” that central-level policymakers set out for them (DEN10). Moreover, national budgeteers are increasingly aware that the maintenance of implementation tasks also requires resources (DEN03). In fact, “resources have followed complexity [increases] all the time” (DEN24).

In sum, Denmark’s central-level implementers find themselves in a rather comfortable position regarding resourcing. Interviewees noted that they would not find it “fair to complain about resources” as they had the “the right amount” at their disposal (DEN02). In any case, added implementation tasks typically also bring about “more money” (DEN02; DEN04). Central-level generosity is furthermore evidenced by the comparatively high level of Danish public sector expenditure covering administrative costs. Denmark ranks fourth among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in public sector spending as a percentage of GDP; central government employment, too, has “been fairly steady for the last ten years” (European Commission, 2018: 220).

4.3.3 Overload Compensation

In addition to higher overload vulnerability, policy triage on the local level also results from the limited ability of MEAs to compensate for overload, especially in comparison to the national agencies.

At the local level, organizational commitment toward implementation is well-developed in terms of overall organizational culture. For one, MEA staffs are homogeneous in terms of educational backgrounds, career paths, and administrative qualifications. Apart from MEAs’ top management, even unit and office heads are usually “hybrids” with university degrees in environmental science or related disciplines (DEN07); while most staffers have been trained as biologists, environmental technicians, foresters, engineers, and chemists are also common (DEN11; DEN08). Besides, employment relations are rather stable. Career durations of fifteen to twenty years in the same organizations are quite common in Denmark, with some careers lasting up to forty years.

Although job rotations occur often in Denmark, they typically happen horizontally – between different units and municipalities. Consequently, not only the work environments but also staff composition are very similar across MEAs. Furthermore, Danish public administration is generally known for tightly knit working relationships that create high levels of familiarity and interpersonal trust, characteristics that hold particularly true for municipal environmental inspectors who get “employed on the basis of (…) professional experience and trained through Local Government Denmark” (OECD, 2019: 109). MEAs are typically small organizations, rarely exceeding thirty employees, all of which “got into this [line of work] because they care about the environment” (DEN07). These small organizational sizes further foster strong organizational ties among MEA staff, creating a sense of working together for a common cause (DEN07). This results in a distinct and enduring municipal esprit de corps that permeates MEAs, with organizational routines focused on ensuring the quality, internal consistency, and effectiveness of environmental policies (DEN06).

In terms of perceived policy ownership, however, local-level commitment to compensate for overload is less developed. Although the MEA staffers are intrinsically motivated toward effective environmental implementation, largely perceive the impacts of their efforts, and firmly consider themselves responsible for managing additional workloads, they still often feel instrumentalized. This sentiment arises from having to cope with the implementation burdens imposed by the central level in a context of nonexistent consultation and inadequate resource provision (DEN07; DEN08; DEN06; DEN11). Despite pronounced efforts to improve efficiency by standardizing administrative procedures, pooling resources, and cooperating across MEAs to “create a synergy between projects and tasks” (DEN07; OECD, 2010: 127), staffers consider themselves unable to do so much further. Since municipal councils and local governments are usually also not involved in setting national policy goals and therefore harbor “problems with the political aspects of those goals” (DEN07), MEAs report to be in “a kind of dilemma” that results from trying to satisfy contradictory local and national policy preferences (DEN06). In sum, MEAs display “a lot of good will” – yet due to lack of support from the central level – perceptions of true policy ownership remain at a moderate level (DEN08).

In contrast, at the central level, there is a well-developed internal commitment to addressing and compensating for overload. In terms of organizational culture, the EPA, EA, NA, and Ecolabelling Denmark are altogether “scientifically based” (DEN04), “very professional” (DEN10), and “definitely (…) purpose-driven” (DEN18). The organizations are characterized by a joint esprit de corps among their staffs that is “mostly concerned with implementing policy and making it work” (DEN18) “with a high degree of effectiveness” (DEN10). The central-level agencies share an orientation toward the quality, internal consistency, and effectiveness of the policies they must implement. This organizational style is evidenced best by the rigorous “no mistake culture[s]” (DEN09) and “long education and (…) long working experience” (DEN09) – standards vigorously upheld by its staffers. Although staff composition is less homogeneous due to agencies’ size, functional assimilation clearly integrates different educational backgrounds, career paths, and administrative qualifications into the group of politico-administrative leaders or the group of technical specialists. Every organization cultivates a joint esprit de corps despite “people hav[ing] different roles in (…) [the] organization” (DEN03; Hansen, Reference Hansen2013). Sharing responsibilities creates a collaborative dependency (DEN01; DEN24). Rooted in vivid information exchange and a work environment that staffers unanimously describe as integrative, collegial, and open (DEN10; DEN04; DEN18), we observe high levels of policy advocacy in all agencies at the central level.

In a similar vein, perceived policy ownership also is strongly pronounced. Staffers generally appreciate the benefits of the policies they must implement and accept responsibility for them: Staff members show a pronounced sense of intrinsic motivation, taking great personal satisfaction, professional status, and pride in perceiving their impact on policy outcomes “every day” (DEN03; DEN04). In fact, the general feeling that it is upon individual staffers to improve and promote environmental issues is so prevalent that a large proportion of agency staffers “feel responsible (…) not only for doing a good job (…), but for coming up with something (…) that is considered world class” regarding implementation (DEN24; DEN02; DEN09; DEN04). Furthermore, efforts of organizational restructuring, and administrative resource reallocation show continuous engagement to “change up the ways” they function and “adapt” to future political developments, novel digitalization trends, and the recent state of effectivity-enhancing administrative reforms (DEN12; DEN09; DEN01; DEN04). Fundamentally, central-level agencies display “big awareness for the policies and how to fulfil the goals” as they are “quite aligned with the policy aims.” On the one hand, this is due to their involvement in policy development early on (DEN18), and, on the other, the “great deal of flexibility” and substantial discretion in implementation benefit high levels of ownership (DEN04). High levels of organizational slack grants agency staffers “quite a big possibility to find solutions” and “make decisions on the lowest possible level,” as they do not “have to ask about everything” or sit “on their hands waiting to get an order” (DEN10). Essential administrative responsibilities are thus “really pushed down to the managerial level or even lower” (DEN01), thereby creating a work environment of personal initiative and autonomy that in turn helps with internalization and endorsement of policy objectives.

4.4 Consistently Top, Mixed at the Bottom: Variation of Policy Triage Across Sectors

Having explained why local-level MEAs exhibit significant triage activity while none of the central-level environmental agencies do, we now turn to addressing the second puzzle, which unfolds inter-sectorally – that is, between the municipal administrations of the environmental and social realms. Why is it that MJCs, in contrast to their environmental counterparts, do not exhibit significant triage activity, even though the allocation of competences and decentralization efforts have left both sets of implementers challenged by increasing implementation burdens? To address this second puzzle of inter-sectoral variation, we will again turn to our three mechanisms relating to overload vulnerability and overload compensation. Beforehand, we will detail the specific triage situation in social policy implementation to highlight and illustrate the unexpected inter-sectoral differences among municipal implementers.

4.4.1 Policy Triage in Social Policy Implementation

Like their environmental policy counterparts, Danish central-level social agencies do not engage in significant triage activity. All interviewees from PD reported that the agency does not only “perform its tasks” but also that its entire “raison d’être” is to “deliver smoothly, effectively, and with a high degree of customer satisfaction.” When asked about incidents of even small-scale prioritization or delays in implementation, none of them could “come up with an example in which PD had asked the lawmakers to postpone implementation of regulations” (DEN05). While there certainly are minor “areas on which (…) [PD] does not have that much attention on” at a given point in time, these are rare “instances” (DEN05). However, those instances can hardly be classified as policy triage, as they occur only in times of high pressure to implement new legislation on a large scale and do not constitute implementation deficits of any kind. At the most, the agency “runs risks of defocusing its managers” since the gradually growing legal and administrative complexity in social policy may temporarily entail few “negative consequences on efficiency” (DEN05; DEN13; DEN14).

Tasks that are postponed are limited to three kinds of secondary implementation chores: first, adjusting “minor details after the implementation” in case PD’s software specialists “find out that the IT-system is not coping 100% with the new regulation and need to filter out some problems” (DEN05); second, optimizing the customer services and communications (DEN14; DEN13); third, improving the overall functioning and procedural integration of different social benefit branches within the IT system in order to weatherproof against potential increases of administrative complexity in the future (DEN13; DEN14). Evidently, none of PD’s very low-frequency and low-severity triage activities even remotely concern the “about 80%” of “mandatory stuff” the agency must process but relate strictly to the “maybe 20%” of issues placed in its “own capacity” (DEN13). If at all, PD staff would only ever “down-prioritize somewhat the things that we on the inside would benefit from.” So, “it is only the ‘more efficiency’ related tasks that would lose in the [triage] decisions” (DEN14; DEN13). In sum, PD is “a huge implementation house” and its “license to operate is that it is delivering” (DEN05).

In a similar vein, the STAR also fares exceptionally well. The agency’s decisions on what not to do, or not to do as intensely, are typically related to secondary policy application processes that can sustain a short period of relative inattention (DEN15). These triage decisions, such as temporarily closing initiatives or postponing implementation to the next month, are only made at a microlevel when the workload has been very high for an extended period, and when it has been checked and documented that the triaged tasks can be managed later without causing failure (DEN17). It is important to note that these triage activities never touch upon the core meaning of the legislation but focus on other less critical areas for individual unemployed and job placement services in general. Overall, despite occasional incidents where the agency may not be able to perform optimally, none of the interviewed PD staff members considered policy triage and implementation deficits caused by overload to be a significant problem (DEN15; DEN17).

At the local level, MJCs also fare well with implementing the “very structural, fundamental labor market policy” despite some “bottleneck problems” (DEN19). The only time policy triage may be observed to “some extent” and “in certain areas” is, again, for a short time after new laws and regulations have been added “on top” of existing ones. Only then may MJC staff find it “difficult to get a steady pace” as it is “extremely challenged” (DEN19) with keeping the “eyes on the ball.” Notwithstanding, MJCs still “secure implementation” of all tasks and objectives in their responsibility because the “changes (…) are actually just to refine or adjust prior legislation” and usually relate to the “tactical or operational level” only. In other words, there is “no thing, no regulation that MJCs cannot implement right now” (DEN23).

The only consequence of triage is the risk of being unable to ensure that some units work together “in an organized and meaningful way” (DEN20; DEN16) or that MJCs struggle for a short period with what is internally called “on the surface implementations” (DEN20); implying that MJCs might postpone the implementation of new procedures for very short periods. To “install a deeper understanding” about the new implementation tasks might take “sometimes a week, sometimes four or five months” (DEN20; DEN16). Yet, the “biggest problem” (DEN20) MJCs face right now seems to be a widely perceived conflict between the procedural requirements for documenting implementation and their primary objective of providing job placement services, both statutory tasks (DEN23; DEN21). Yet, in sum, the MJCs’ triage activity is almost nonexistent, enabling local social authorities to avoid implementation deficits altogether.

4.4.2 Differences in Overload Vulnerability at the Local Level: MEAs and MJCs

Having characterized each social sector organization’s specific triage situation, we now turn to explaining the puzzling disparity in inter-sectoral triage variation at the local level. Why is it that MJCs, in contrast to MEAs, do not display any triage activity, even though administrations face rising implementation burdens pushed downward from central agencies and an increasing level of complexity within existing provisions? In the following, we analyze to what extent these differences result from different degrees of overload vulnerability in terms of political blame-shifting and mobilization of external resources.

Blame Attribution for Implementation Failure

Compared to the environmental sector, politicians face much more limitations in attributing the blame for implementation failures to social implementers at the local level. The main reason for this lies in the nature of the policy field. For social policy, implementation failures directly affect many citizens, leading to higher politicization and political responsibility regarding implementation failures. For environmental policy, by contrast, implementation failures are less likely to receive similar levels of attention. At the same time, this constellation implies that policymakers strongly engage in supervising the implementation performance of MJCs.

The generally more favorable conditions within MJCs may best be accounted for by the “great interest in implementation” (DEN15) national policymakers have “always” (DEN13) shown for what happens to their policies when handled at the local level. In contrast to the local implementation of environmental policy, social policy is thoroughly “discussed in the public, on social media, in newspapers, and on television” (DEN23). Many political actors as well as the public are therefore strongly opinionated about it and, consequently, implementation easily turns into a “perfect battlefield for political competition at the national level” (DEN21). In effect, central-level policymakers have little choice but to “stand out” and take a more active stance vis-à-vis MJCs (DEN23), placing them under a “tight[er] scrutiny” than environmental counterparts (DEN21). Thus, MJCs are not only being actively “watched and controlled” by municipal councils and governments but also by national policymakers especially via STAR (DEN23; DEN20; Winter et al., Reference Winter, Dinesen and May2007).

Political stability in oversight relations for national pensions, labor market, and employment policies is made “sure” by two other limitations on central-level blame-shifting opportunities (DEN17; DEN05). First, a “very complex interactive system,” which combines procedural rules on implementation tasks, directly guides MJCs implementation efforts by top-down stipulations as well as economic incentives on government grants and refunds (DEN20; DEN21). It requires MJCs to document employment services provided, the scope of client interaction, and the unemployed persons’ job searching behavior in the national measurement system jobindstats.dk, thus providing “many checkpoints” for MJCs and national policymakers alike (DEN20). If an MJC “gets behind” on any of the “prescribed administrative things” to do (DEN23), it will “get bad marks from national authorities” that ultimately reflect poorly on the national level (DEN20; Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010). Second, STAR deploys a parallel benchmarking process that uses regular performance audits to evaluate whether MJCs “actually live up to those legislative standards” for which the central level is accountable (DEN21; DMEA, 2014).

Benchmarking arrangements entail a systematic monitoring process carried out by STAR, where data from jobindstats.dk regarding MJCs’ implementation efforts are measured against a set of numerical targets. These targets are derived from a statistical model that benchmarks the expected performance of an MJC based on the socioeconomic status of its municipality (Hendeliowitz, Reference Hendeliowitz2008; DEN17). If an MJC continually misses performance goals, STAR will join in, first, by requiring a detailed report on how the MJC intends to achieve the targets with future effort, and then by actively intervening “with the help of consultants” (DEN20). At this point, the municipal mayor would have to visit the Minister of Employment and would be “sent back to the MJC with a lifted finger” saying “you need to improve” (DEN20). In the highly unlikely case that “pressures from both state and municipal” levels do not render the underperforming MJC able to fulfill the procedural prescriptions on its implementation tasks (DEN16), STAR would finally intervene directly and contract out implementation to private service providers (Bazzani, Reference Bazzani2017; DEN16; DEN15). So, although national policymakers are not in direct control of all implementation aspects and may initially and selectively use MJCs “as a scapegoat” (DEN19; cf. Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010), factual policy responsibilities still rest firmly in national hands (Blom-Hansen, Reference Blom-Hansen and Moisio2012; cf. Thorgaard & Vinther, Reference Thorgaard and Vinther2007).

In sum, there is sound national responsibility to “fix municipal problems from state level” (DEN16), making practical application of social policy the “area of municipal competence with most restraints form central government” and a “poor platform for self-promotion at the local level” (DEN21). While central-level policymakers do no longer carry the full costs of implementation after the 2007 Structural Reform, combining an “economic regulatory system and a rule driven regulatory system” (DEN19) still makes political responsibilities duly attributable to them (Hendeliowitz, Reference Hendeliowitz2008; DEN17). To minimize blame-shifting in the implementation of MEAs, the 2007 policy that transferred these responsibilities from the national government to municipalities can be described as decentralized centralization. This term reflects the paradox where local authorities are given greater control over implementation while ensuring national standards and oversight are maintained (Knuth & Larsen, Reference Knuth and Larsen2010: 182; Lindsay & McQuaid, Reference Lindsay and McQuaid2009: 458, f.; DEN21). Essentially, “Danish municipalities are autonomous within the boundaries of law and administrative rules issued by the Ministry of Employment” (Winter et al., Reference Winter, Dinesen and May2007: 9), making MJCs “a very small wheel politically and a very big wheel [operationally] in the mechanics of the labor market” (DEN16).

Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

There is a second pronounced difference between the MEAs and MJCs when it comes to overload vulnerability. External resource mobilization is more likely to be successful for social implementers than for the environmental ones. On the one hand, MJCs are generally better able to articulate their positions in the policymaking process. On the other hand, budgetary frameworks provide them with more generous funding conditions as it is the case for their environmental counterparts.

Better opportunities for political articulation result from three factors. First, the Association of Danish Jobcentre Directors has a strong political voice in the Employment Ministry (DEN21), since high-level ministry officials – often including the minister – attend its annual great assembly (DEN21). Additionally, the association meets “throughout the year with ministry representatives” (DEN21).