Introduction

Empathy grants designers access to a fine-grained understanding of user needs (Giacomin, Reference Giacomin2014). Within design, empathy is defined as “the intuitive ability to identify with other people’s thoughts and feelings – their motivations, emotional and mental models, values, priorities, preferences, and inner conflicts” (McDonagh, Reference McDonagh2006). Empathy’s dimensions comprise affective empathy, which concerns emotional resonance with others’ feelings, and cognitive empathy, which is the ability to understand their perspective (Duan and Hill, Reference Duan and Hill1996). Within design, empathy has bridged knowledge gaps between designers and users with unrelatable characteristics (Gray et al., Reference Gray, McKilligan, Daly, Seifert and Gonzalez2015), frequently applied through a range of empathic design methods. These include observing users in their contexts (Patnaik, Reference Patnaik2009) and simulation-based techniques, such as empathic modeling, to simulate users’ physical or cognitive conditions (Nicolle and Maguire, Reference Nicolle, Maguire and Stephanidis2003; Moore, Reference Moore2012).

The inherent ability or capacity to empathize, known as dispositional or trait empathy, suggests that empathy is a stable concept (Cuff et al., Reference Cuff, Brown, Taylor and Howat2016). Empathic concern and perspective-taking dispositional tendencies were found to positively influence creative concept generation and selection among designers and design teams (Alzayed et al., Reference Alzayed, Miller and McComb2021, Reference Alzayed, Miller, Menold, Huff and McComb2023). However, empathy has also led to designers fixating on user responses (Mattelmäki et al., Reference Mattelmäki, Vaajakallio and Koskinen2014), limiting the creativity needed in developing innovative human-centered solutions (Crilly and Cardoso, Reference Crilly and Cardoso2017). Designers’ intrinsic ability to empathize is bounded by their unique life experiences (Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser, Reference Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser2009), making it challenging for designers to empathize with user experiences that are unrelatable and unfamiliar to designers (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, De Sainz Molestina, Galluzzo, Rizzo and Spallazzo2023). Interpersonal similarities between designers and users, such as shared culture, gender, or prior visits to the user’s country, can improve empathic accuracy by providing common ground for interpreting users’ thoughts and feelings, although they are context-dependent and may diminish when designers and users already share the same environment (Li and Hölttä-Otto, Reference Li and Hölttä-Otto2023). However, designers also need to be aware of their similarities with users, necessitating them to be mindful of cognitive biases such as projection and egocentric biases (Yadav, Reference Yadav2020). This, in turn, requires designers to detach from their users’ experience to analyze any similarities and differences (Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser, Reference Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser2009). De Vignemont and Singer (Reference De Vignemont and Singer2006) argue that empathic responses are shaped by mental evaluations that consider factors such as the nature of the emotional stimulus, traits of the person empathizing, and their relationship with the target. This aligns with design research claiming that empathic understanding, which concerns a detailed understanding of user experiences, is hypothesized to be situated, which is affected by external factors, such as empathic design action and research, and internal factors, including dispositional empathy and underlying mental processes (Surma-Aho and Hölttä-Otto, Reference Surma-Aho and Hölttä-Otto2022). Situational, or state empathy, refers to an individual’s response to a situation, stimuli, or context (Decety and Ickes, Reference Decety and Ickes2011), and therefore, this research applies this notion of situational empathy to represent the resulting empathic outcome. Further research is needed to understand how dispositional empathy influences creative conceptualization and various stages of the design process (Alzayed et al., Reference Alzayed, Miller and McComb2021) and the causality of empathy on design outcomes (Chang-Arana et al., Reference Chang-Arana, Surma-Aho, Hölttä-Otto and Sams2022). This research addresses this need by investigating the human influence of dispositional empathy on situational empathic responses. The research findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the nature of empathy, thereby informing design practices. Additionally, the approach to obtaining situated empathy outcomes creates the opportunity to increase the traceability of empathy in subsequent design activities, representing a first step toward a deeper understanding of how empathy is translated into design solutions.

The relationship between dispositional and situational empathy is analyzed through an immersive experience in virtual reality (VR). Besides the VR’s successful application in eliciting empathy (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Bailenson, Weisz, Ogle and Zaki2018; Han et al., Reference Han, Shin, Ko and Shin2022), even in the design field (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Dong, Bai, Lindeman, He and Piumsomboon2022; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Casakin, Georgiev and Otto2023), VR offers consistency for multiple viewers (Neo et al., Reference Neo, Won and Shepley2021), offering enhanced environmental control to analyze interactions compared to physical settings. Spek et al. (Reference Spek, Sleeswijk Visser, Smeenk, Gray, Ciliotta Chehade, Hekkert, Forlano, Ciuccarelli and Lloyd2024) also highlight the importance of empathic interventions in design processes through VR to target prosocial behavior and promote sustained change. Additionally, several studies demonstrate the powerful influence of empathy when taking the first-person perspective of the target in VR (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Bailenson, Weisz, Ogle and Zaki2018; Seinfeld et al., Reference Seinfeld, Arroyo-Palacios, Iruretagoyena, Hortensius, Zapata, Borland, de Gelder, Slater and Sanchez-Vives2018; Han et al., Reference Han, Shin, Ko and Shin2022). This article presents findings from empirical research that immersed participants in the first-person perspective of a user living with vision impairment in VR to establish the influence of dispositional empathy on the situated outcome. The situational empathic responses were obtained through a self-reflection activity in which participants were invited to recall their thoughts and emotions following the VR experience. The reflections were examined through a qualitative evaluation system for analyzing situated empathy experienced from a first-person perspective, entitled the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024). Results demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between dispositional empathic concern and situational affective empathy, and between situational cognitive and situational affective empathy, emphasizing how situational emotional responses are closely tied to inherent empathic tendencies, the importance of context in eliciting cognitive empathy, and how emotional responses can prompt additional cognitive thinking. This research proposes a system of methods and tools to elicit and measure situated empathy when experienced from a first-person perspective. The outcomes of this research form part of broader research that provides the opportunity to facilitate the next generation of human-oriented design innovation.

Empathy’s dimensions and constructs

Empathy’s cognitive and emotional dimensions (Duan and Hill, Reference Duan and Hill1996) align with neuroscience, describing empathy as the balance between knowing and feeling, which is reflected in our brain’s innate functional dynamics that influence the empathic interaction (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Uddin, Di Martino, Castellanos, Milham and Kelly2012). This is mirrored in the design field, in which Hess and Fila (Reference Hess and Fila2016) argue that both affective and cognitive empathy components are required for designers to deeply understand user experiences, achieved by balancing empathy with analysis of its nature (Battarbee et al., Reference Battarbee, Suri and Howard2015). When analyzing designers’ dispositional empathy, research argues the criticality to encompass both cognitive and affective dimensions (Surma-Aho and Hölttä-Otto, Reference Surma-Aho and Hölttä-Otto2022).

Empathy’s cognitive and affective dimensions are encompassed within dispositional and situational empathy constructs. However, dispositional and situational empathy may not always align (Seo et al., Reference Seo, Geiskkovitch, Nakane, King and Young2015). An individual with low dispositional empathy might still display strong situational empathy in certain contexts, and vice versa. The higher the level of dispositional empathy in individuals, the greater the potential for situational empathy to occur toward people in unfortunate circumstances (Konrath et al., Reference Konrath, Meier and Bushman2018). However, divergences may occur through other factors, including the context and level of arousal, which could affect the resulting situational empathy (Decety and Ickes, Reference Decety and Ickes2011). This highlights a need to determine the extent of the relationship between dispositional empathy and situational empathy in a contextual scenario, which aligns with this research’s aim. Figure 1 visually presents an example of the divergences in cognitive and affective empathy linked to dispositional and situational constructs.

Figure 1. Dispositional and situational cognitive and affective empathy. Generated using Icograms® (Decety and Ickes, Reference Decety and Ickes2011; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Geiskkovitch, Nakane, King and Young2015).

Measuring dispositional empathy

Approaches to obtaining a measure of dispositional empathy rely heavily on self-report tools (GenÇ and Verma, Reference GenÇ and Verma2024), and this includes studies involving measuring empathy in VR (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024). The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI), developed by Davis (Reference Davis1980), is one of the most widely used measures of assessment in psychological literature (Fultz and Bernieri, Reference Fultz and Bernieri2022) and the most widely applied tool for measuring empathy in VR research (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024), and was therefore applied in this research to measure dispositional empathy. Challenges associated with the IRI, which are also linked to self-reported measures, include subjectivity, response biases, and self-presentation motives (Van de Mortel, Reference Van de Mortel2008; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Fraley and Krueger2009); however, its validity, including test–retest reliability, was demonstrated across research (De Corte et al., Reference De Corte, Buysse, Verhofstadt, Roeyers, Ponnet and Davis2007; Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Dufey and Kramp2011; Gilet et al., Reference Gilet, Mella, Studer, Grühn and Labouvie-Vief2013). The IRI is based on the empathy-altruism hypothesis (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Ahmad, Lishner, Tsang, Snyder and Lopez2002), which was developed to theoretically predict prosocial behavior. It advanced empathy measurement by assessing four different components or subscales, which align with empathy’s cognitive and affective dimensions, making it advantageous for this research to obtain a measure of an individual’s cognitive and affective tendencies. The four subscales of the IRI are described in Table 1, and are incorporated in 28 questions assessed on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 1. IRI subscales descriptions (Davis, Reference Davis1980)

Research associates the Fantasy Scale (FS) and Perspective Taking (PT) subscales with cognitive empathy, while Empathic Concern (EC) and Personal Distress (PD) with affective empathy (Harari et al., Reference Harari, Shamay-Tsoory, Ravid and Levkovitz2010; Maurage et al., Reference Maurage, Grynberg, Noël, Joassin, Philippot, Hanak, Verbanck, Luminet, de Timary and Campanella2011; Hengartner et al., Reference Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Müller, Haker and Rössler2014). Such associations were therefore adopted in this research. Intercorrelations between subscales have also been demonstrated, for instance, EC was significantly positively correlated with FS and PT (Hawk et al., Reference Hawk, Keijsers, Branje, Graaff, Md and Meeus2013; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Minote, Sekiya and Watanuki2016; Fultz and Bernieri, Reference Fultz and Bernieri2022).

Measuring situational empathy

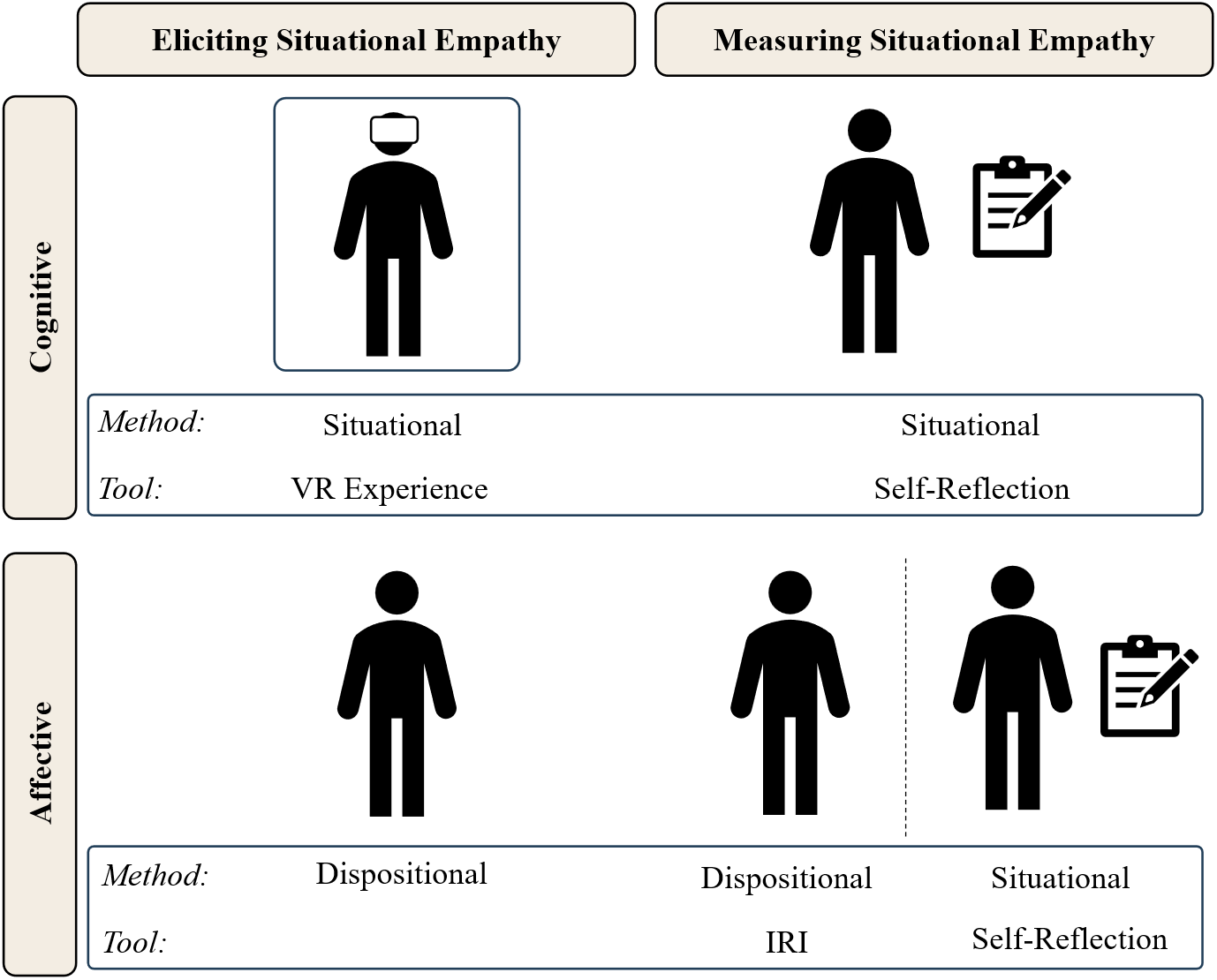

Several approaches have been applied to measure situational empathy, including interviews with participants about their experiences immediately after the empathic interaction (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Aiello, Scepanovic, Quercia and Konrath2021; GenÇ and Verma, Reference GenÇ and Verma2024), physiological measures such as heart rate and skin conductance, and computational models (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Imel, Georgiou, Atkins and Narayanan2016; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Aiello, Scepanovic, Quercia and Konrath2021). Shen (Reference Shen2010) developed a 12-item scale to measure situational empathy experienced by participants perceiving public service announcements. However, this measure was applied when empathizing from a second-person perspective, questioning its relevance to the first-person perspective applied in this research. Design research investigated the influence of dispositional empathy on design outcomes and innovation attitudes. Although Alzayed et al.’s (Reference Alzayed, Miller and McComb2021) study presented positive relationships between dispositional empathy and creative conceptualization, Apfelbaum et al.’s (Reference Apfelbaum, Sharp and Dong2021) study highlighted a weak relationship when evaluating behavioral expressions of empathy in students’ assignments and presentations through the Empathy in Design Scale. Instead of analyzing the translation of dispositional empathy into design activities, this research focuses on the experience of empathy itself. Empathy is characterized as an interactive and reflective process (Chang-Arana et al., Reference Chang-Arana, Surma-Aho, Hölttä-Otto and Sams2022), representing a dynamic interplay that allows designers to shift between immersing themselves in someone else’s experience and stepping back to analyze it critically (Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser, Reference Kouprie and Sleeswijk Visser2009), highlighting the crucial role of reflection in the empathy experience. Therefore, this research applied self-reflection to measure situational empathy when experienced from a first-person perspective in VR, which involved recalling thoughts and emotions that mirror empathy’s cognitive and affective dimensions.

Alongside reflection, the authors developed the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) to validate an evaluation system for analyzing situational empathy reflections, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of empathy’s nature. Therefore, the reflections provide insights into individual empathy experiences, which are analyzed through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024). Before applying the evaluation system for this research, the authors tested it through a pre-study conducted in a physical setting. The pre-study consisted of workshops held with design students involving an empathic interaction in which students simulated the first-person perspective of the user. Besides validating an evaluation system for empathy, the purpose of the pre-study was to prototype the VR experience in a physical setting, thereby confirming the methodological feasibility of conducting VR experiences within a design setting. The students’ empathy responses were captured through self-reflection following the interaction, inviting them to recall their thoughts and emotions. The reflections gathered insights into the students’ individual experience, which were subsequently analyzed through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024). Results highlighted powerful situated cognitive and affective empathy responses; therefore, this approach to capturing and analyzing situational responses was applied to this research. Figure 2 summarizes the dispositional and situational empathy constructs, according to their respective dimensionality and methods of measurement. The following sections delve into the design and development of the virtual experience, including further detail on analyzing situational empathy responses.

Figure 2. Dispositional and situational empathy constructs defined according to their dimensionality and measurement method (Davis, Reference Davis1980; Duan and Hill, Reference Duan and Hill1996; Shen, Reference Shen2010; Decety and Ickes, Reference Decety and Ickes2011; Cuff et al., Reference Cuff, Brown, Taylor and Howat2016; GenÇ and Verma, Reference GenÇ and Verma2024; Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024).

VR experience design and development

Vision impairment is an unrelatable condition to most designers. Designers have simulated impaired vision through wearable blindfolds and goggles to empathize with this user group (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Yoo and Parker2021). Raviselvam et al. (Reference Raviselvam, Hwang, Camburn, Sng, Hölttä-Otto and Wood2022) facilitated empathy through simulated scenarios in which participants assisted individuals with vision impairment with everyday tasks. Despite the robustness of current tools (Shah and Robinson, Reference Shah and Robinson2007), designers face challenges in understanding the lived experience and, consequently, in gaining a holistic understanding of how users navigate their mental, emotional, sensory, and life experiences, beyond their physical condition (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, De Sainz Molestina, Galluzzo, Rizzo and Spallazzo2023). Besides VR’s capacity for first-person perspective-taking (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Bailenson, Weisz, Ogle and Zaki2018; Seinfeld et al., Reference Seinfeld, Arroyo-Palacios, Iruretagoyena, Hortensius, Zapata, Borland, de Gelder, Slater and Sanchez-Vives2018; Han et al., Reference Han, Shin, Ko and Shin2022), research exploring empathy in VR highlights that empathic engagement is also enhanced when VR environments contain rich contextual detail (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Casakin, Georgiev and Otto2023). In Georgiev et al.’s (Reference Georgiev, Nanjappan, Georgieva, Gong, Holloway-Attaway and Murray2023) study, participants developed empathy when immersed in the experiences of individuals with color-vision deficiency through interactive, narrative-driven experiences depicting vision impairment. These findings suggest that immersive narratives and contextually rich scenarios play a vital role in strengthening empathic understanding in VR. Therefore, a contextual surrounding drawn from a habitual experience of this user group was chosen to be represented in the VR environment from a first-person perspective.

The act of ordering food and drink items from a menu in a restaurant environment was chosen for this research as it represents a familiar setting for most designers and presents multiple challenges for people living with vision impairment. The authors of this research conducted a diary study with nine users living with vision impairment to understand their life experiences, including their lived experiences, and to reveal challenges that they encounter in the restaurant context. The sample was diverse and incorporated varied age groups and vision impairment conditions. The users were invited to document a digital diary, taking ~10 min per day for each user over a 6-day period. They were invited to reflect on their experiences with vision impairment in the restaurant scenario, capturing users’ cognitive and affective engagement with lived realities. After completing the diary, a semi-structured interview was held with each user to discuss their diary entries. Results revealed multiple challenges related to their lived experiences and the restaurant context were integrated into the VR experience, as detailed in the following sections.

Pre-VR experience

The users’ lived experiences were represented in the pre-VR experiences through a narrative brief (Table 2), presented to the participants before immersing in the VR environment. The brief introduced the participants to a user persona, designed to balance sufficient detail to elicit empathy, but also allowing varying interpretations (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Chandrasegaran and Lloyd2025). This was achieved by providing participants with the persona’s background, including long-term social and financial challenges, and their objective in the VR experience, which was to order a meal with the support of a server.

Table 2. Narrative brief presented to participants pre-VR experience

VR environment

The user experience related to their restaurant experience, as revealed by the diary study, was translated into elements incorporated in the VR environment, as illustrated in Figure 3. The elements in the VR environment reflect tasks that the participants have to navigate, which can be challenging. These include having participants sit alone at the table, an inaccessible menu with items that were complex to understand, and noisy diegetic audio of a busy restaurant. The users’ vision condition was communicated through severely blurred vision, ensuring that the elements incorporated in VR are conveyed.

Figure 3. (a) Virtual restaurant highlighting participant location. (b) Perspective taken by the participant with embodied hands, overlooking the dining table. (c) On the left, the viewer’s perspective is observed without the blurred vision applied using the Bokeh blur effect. On the right, the blurred vision is implemented. Developed using Unity Game Engine 2022.3.5.

The participant is positioned in the center of the virtual restaurant, as highlighted in Figure 3a. Figure 3b displays the perspective taken by the participant with embodied hands, overlooking the dining table with the relevant tableware and the same menu used in the physical prototype testing. Through head and hand tracking, the participant can interact with objects on the table and with the surrounding environment. The experience is designed to be standalone, with the dining table and chair matched to a physical table and chair. The participant remains seated throughout the experience and enters the environment seated at the restaurant table with blurred vision, as shown in Figure 3c. The blur effect was created using Bokeh quality mode, a blurring system that applies to both near and far fields, making it relevant for this context.

The outline of surrounding virtual agents representing people dining and the waiters at the restaurant was recognizable, although details related to facial expressions and gestures were challenging to grasp. The VR experience involved a social interaction with one of the waiters, who approached the participant to take their order. The waiter’s dialogue was programmed through Artificial Intelligence-generated voice prompts that were triggered in real-time by the author of this research. During the conversation, the waiter applied gestures, programmed through animations, to incorporate the user challenge in interpreting nonverbal communication. The activity was time-bound to 5 min; however, the waiter did not approach the participant until three and a half minutes into the experience. This allowed sufficient time for the participants to familiarize themselves with their surroundings, attempt to read the menu, and request support to take their order. Table 3 presents a storyboard, describing each stage of the VR experience along with the rationale behind each stage.

Table 3. Storyboard incorporating designed actions and reasoning behind them (generated using ShapesXR® and Icograms®)

Research methodology

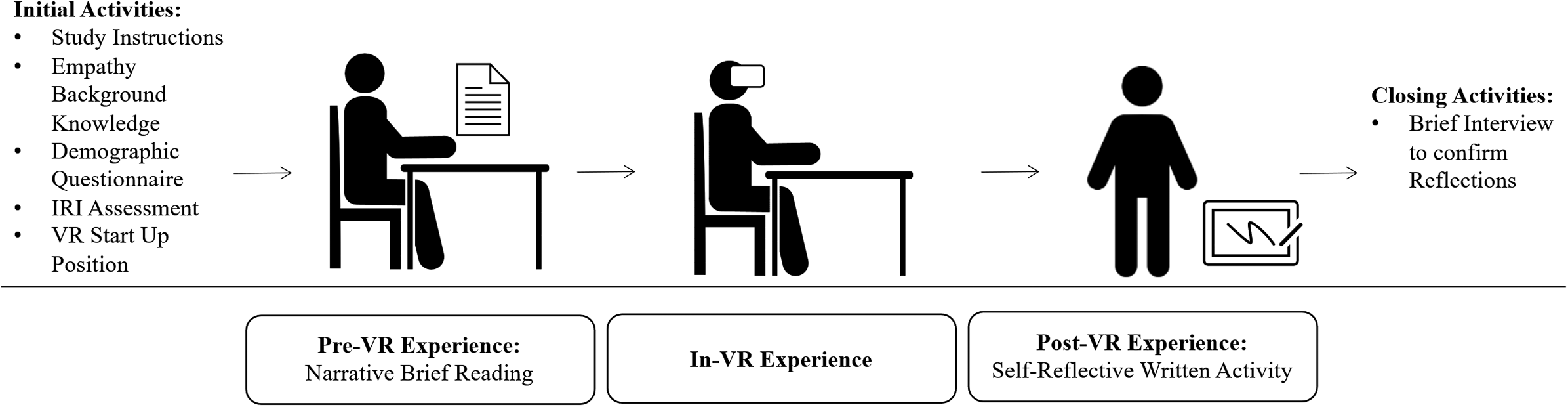

The research was conducted over 10 weeks, with a maximum of four sessions per day and one participant per session. Each session lasted a maximum of 60 min and consisted of seven parts, described in the list below. The experimental setup for the VR experience consisted of a chair and table physically aligned with the participants’ starting position in VR to ensure seamless integration between the physical and virtual experience. The session consisted of the following experimental stages and is further described in Figure 4:

-

(1) a brief introduction to the research with clear written instructions provided on the structure of the session,

-

(2) a background on what empathy is and its dimensions,

-

(3) participant completing a demographic questionnaire followed by the IRI self-assessment,

-

(4) positioning the participant to the viewer’s starting position of the VR experience, hence seated on a pre-positioned, physically present chair with a table,

-

(5) participants reading the narrative brief out loud and spending time to reflect on the user and their objective,

-

(6) wearing the head mounted display and performing the VR experience,

-

(7) post-VR experience reflection activity comprising self-written reflections and

-

(8) a brief interview to ensure that the reflections were understood by the author.

Figure 4. Experimental setup highlighting the stages of the VR experience, including initial and closing activities.

Participants recruited

A sample of 58 participants over 18 years of age was recruited. The IRI (Davis, Reference Davis1980) was applied to obtain a self-reported measure of dispositional cognitive and affective empathy. From the 58 participants, results from six participants were omitted due to incomplete results from the IRI, resulting in 52 participants being considered for analysis. Most participants (62%) were in the 25–34 age bracket, 20% were in the 18–24, 15% were in the 35–49, while 3% were over 49 years of age. The sample is predominantly male (76%), the rest being female (22%), and 2% did not disclose their gender. The sample was also culturally diverse, with participants identifying with European, Asian, and African countries.

The participants were from computer science and engineering backgrounds. Although the sample was not primarily from a design background, the research’s aim of deepening current understanding of empathy’s nature, including determining the statistical correlation between dispositional and situational empathy, does not necessitate participants to be designers. The scenario’s context of understanding the participant’s challenges in a restaurant focuses on human responses rather than design-related ones. This is also because the responses need to be aligned with the real-life experiences of the vision-impaired users, who were non-designers. A substantial portion of participants (60%) did not have previous knowledge about vision impairment, 44% of whom expressed their willingness to know more. The rest of the sample (40%) was sensitive toward the user group; however, none of the participants had first-hand experience with severe blurred vision.

Situational empathy analysis

The approach applied in the pre-study was employed after the VR experience to obtain a measure of participants’ situational empathy through self-reflection. The reflections were analyzed using the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024), presented in Table 4, which contains four levels of numerical ranking. The unit of analysis represents a thought or emotion that participants expressed during the post-VR reflective activity. The results were assigned a level of ranking according to their intensity, described in the column “Criteria.” Results stemming from basic or known challenges from the narrative brief, for example, those directly related to blurred vision, were given a ranking of 1. Results attributed to a deeper level of understanding gained from the environment, for example, the challenge of not being able to interact with the cutlery, were assigned a ranking of 2. Cognitive and affective processes related to internal representations of the surroundings, for instance, the discomfort due to noise, were given a ranking of 3. More profound psychological reflections were assigned a ranking of 4. This ranking involves a greater reflection of the participant in the experience, shaped by their individual personal reactions and influences, which include references to their traits and past life experiences. A cognitive (C) or affective (A) empathy dimension was applied to each numerical ranking based on whether the response resulted from a thought or emotion, respectively. The rankings applied to each thought and emotion were summed for each participant to obtain an overall score of their respective situational cognitive and affective empathy outcome. To ensure the inter-rater reliability of the applied ranking, two reviewers assessed 10% of the dataset (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pedersen2013; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Hay, Duffy, Lyall, McTeague, Vuletic, Grealy and Gero2022). Reviewers were trained on the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) application and applied it independently. Agreement was assessed through discussion of discrepancies, which were resolved collaboratively. This process was used to ensure consistency in the final ranking of the full dataset.

Table 4. Empathic Empowerment Scale applied to analyze situational empathy (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024). Adapted from Apfelbaum et al. (Reference Apfelbaum, Sharp and Dong2021)

Results

Situational empathy results

All participants completed the goal of their task by ordering at least one food or drink item and expressed a diverse range of thoughts and emotions directed toward the vision-impaired user, whom they embodied. The participants’ empathy reflections, analyzed through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024), are presented in Table 5. Due to the extensive nature of the dataset, Table 5 presents a selection of results from each level of ranking that are representative of the broader findings. The number in brackets () that follows each ranking depicts the number of participants who expressed that result.

Table 5. Self-expressed reflections of participants applied to measure situational empathy

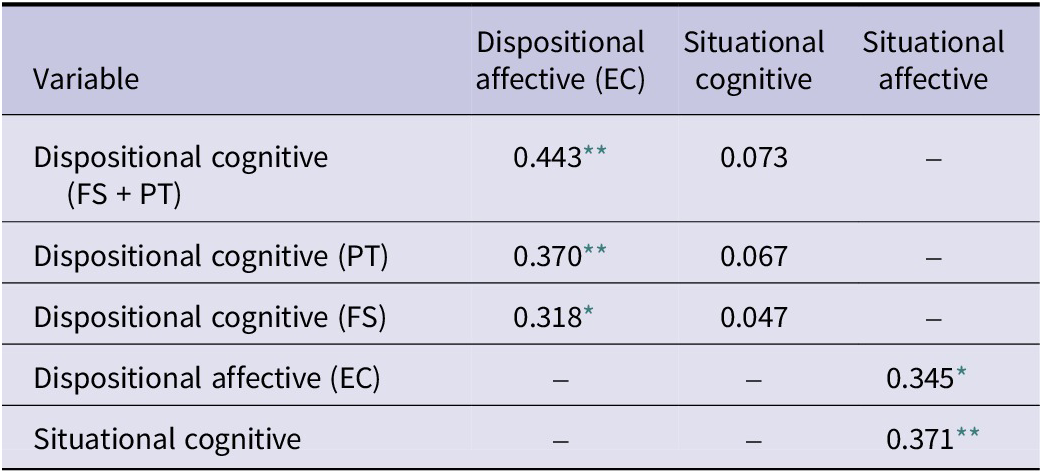

Correlating dispositional and situational empathy

Multiple Pearson bivariate correlations were conducted to assess the relationships between dispositional empathy measured using the IRI and situational empathy evaluated using the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) for both cognitive and affective dimensions. Since the research concerns the analysis of human behavior and emotions, a square root transformation was applied to all situational cognitive and affective responses for normality (Carrera et al., Reference Carrera, Oceja, Caballero, Muñoz, López-Pérez and Ambrona2013; Hurter et al., Reference Hurter, Paloyelis, Williams and Fotopoulou2014). The PD subscale deals with self-oriented feelings of anxiety and discomfort, while other subscales are other-oriented (Davis, Reference Davis1983). Since the situational results examined through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) in this research are oriented toward the vision-impaired user, the PD subscale was omitted in this analysis. Therefore, the measures of the FS, the PT, and their summation (FS + PT) were considered for the dispositional cognitive empathy, while the EC subscale was associated with the dispositional affective empathy as per research (Hawk et al., Reference Hawk, Keijsers, Branje, Graaff, Md and Meeus2013; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Minote, Sekiya and Watanuki2016; Fultz and Bernieri, Reference Fultz and Bernieri2022). Table 6 presents the results of Pearson’s correlation coefficients, r, for each correlation.

Table 6. Summary of Pearson’s correlation results

* Statistically significant at p < .05 level.

** Statistically significant at p < .01 level.

Pearson’s product–moment correlations were run to assess the relationship between dispositional cognitive empathy and dispositional affective empathy. Preliminary analysis showed the relationship to be linear with both variables normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p > .05), and there were no outliers. There was a statistically significant, moderate positive correlation between the dispositional cognitive (FS + PT) empathy and the dispositional affective (EC) empathy, r(52) = .44, p < .001, with dispositional (FS + PT) empathy explaining 20% of the variation in dispositional affective (EC) empathy. There was a statistically significant, moderate positive correlation between the dispositional cognitive (PT) empathy and the dispositional affective (EC) empathy, r(52) = .37, p < .007, with dispositional (PT) empathy explaining 14% of the variation in dispositional affective (EC) empathy. There was also a statistically significant, moderate positive correlation between the dispositional cognitive (FS) empathy and the dispositional affective (EC) empathy, r(52) = .32, p < .02, with dispositional (FS) empathy explaining 10% of the variation in dispositional affective (EC) empathy. Other Pearson’s product–moment correlations were run to assess the relationship between dispositional cognitive empathy and situational cognitive empathy. There was no statistically significant relationship between the dispositional cognitive (FS + PT) empathy and the situational cognitive empathy, r(52) = .07, p < .61, between dispositional cognitive (PT) empathy and situational cognitive empathy, r(52) = .07, p < .64, and between the dispositional cognitive (FS) empathy and the situational cognitive empathy, r(52) = .05, p < .02. Pearson’s product–moment correlation was run to assess the relationship between dispositional affective empathy and situational affective empathy. Preliminary analysis showed the relationship to be linear with both variables normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p > .05), and there were no outliers. There was a statistically significant, moderate positive correlation between dispositional affective (EC) empathy and situational affective empathy, r(52) = .35, p < .01, with dispositional affective (EC) empathy explaining 12% of the variation in situational affective empathy. Another Pearson’s product–moment correlation was run to assess the relationship between situational cognitive and situational affective empathy. Preliminary analysis showed the relationship to be linear with both variables normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk’s test (p > .05), and there were no outliers. There was a statistically significant, moderate positive correlation between situational cognitive and situational affective empathy, r(52) = .37, p < .007, with dispositional affective (EC) empathy explaining 14% of the variation in situational affective empathy.

Discussion

Dispositional cognitive and dispositional affective empathy

The statistically significant intercorrelations (Table 6) between the IRI subscales for all the different combinations tested were expected (Hawk et al., Reference Hawk, Keijsers, Branje, Graaff, Md and Meeus2013; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Minote, Sekiya and Watanuki2016; Fultz and Bernieri, Reference Fultz and Bernieri2022). The moderate strength value was also expected as per research, further indicating that the IRI subscale represents different facets of empathy that contribute toward an individual’s profile (Fultz and Bernieri, Reference Fultz and Bernieri2022). This confirms that the empathic disposition of a human is formed from a combination of elements that contribute to the overall experience, constructed by the distinct IRI subscales (Rankin et al., Reference Rankin, Kramer and Miller2005; Chrysikou and Thompson, Reference Chrysikou and Thompson2016). The strongest correlation was obtained through the FS + PT with EC combination, followed by PT and FS, respectively. This suggests that the combination of FS and PT has a significant positive influence on EC, while PT has a stronger relationship with EC compared to FS. Therefore, this result indicates that the stronger the ability to understand the perspective of someone else, the better the chance of experiencing empathic concern toward that person.

Dispositional affective and situational affective empathy

Table 6 highlights a statistically significant correlation between dispositional affective (EC), measured through the IRI, and situational affective empathy, whereas this was not the case between dispositional and situational cognitive empathy. In a study analyzing the environmental and genetic influences of cognitive and affective empathy (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Uzefovsky, Toccaceli and Knafo-Noam2020), affective empathy was found to be more heritable than cognitive empathy, making cognitive empathy more affected by environmental factors. Neuroscience research supports the differing nature of eliciting cognitive and affective responses through distinct brain activation areas of both cognitive and affective empathy (Stevens and Taber, Reference Stevens and Taber2021). The theory of constructed emotion (Barrett, Reference Barrett2017) proposes that emotions are not immediate responses to what an individual experiences, but begin in the body through sensory input, and the brain subconsciously predicts what is happening based on the individual’s past experiences involving a similar sensory state. Such claims strongly support the high influence of participants’ emotional disposition on their situational emotional responses experienced in this research.

Since cognitive empathy is claimed to be affected more by environmental factors (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Uzefovsky, Toccaceli and Knafo-Noam2020), as demonstrated by the weak relationship between dispositional and situational cognitive empathy produced in this research, cognitive empathic outcomes are therefore more likely to be shaped by contextual elements stemming from the VR experience. This presents an opportunity to apply VR to elicit cognitive empathy and to design VR experiences that stimulate thinking. Additionally, the process of eliciting cognitive empathy through situational methods presents an opportunity for its development and corroborates the potential for VR experiences to develop cognitive empathy. This aligns with empathy in VR research, indicating that cognitive empathy significantly improves after a period of exposure to VR experiences, whereas affective empathy is claimed to revert to its original state (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024), further indicating that affective empathy is inherently linked to disposition.

Situational cognitive empathy and situational affective empathy

This significant relationship between situational cognitive empathy and situational affective empathy indicates that affective responses motivate further thinking, supporting cognitive empathy. This aligns with reflective level emotional responses (Norman and Ortony, Reference Norman and Ortony2003), representing feelings arising in combination with their conscious interpretation. This level is the highest in emotional processing through which humans examine their understanding and actions. Such emotional responses, which can also be generated through subconscious visceral and behavioral level responses (Norman and Ortony, Reference Norman and Ortony2003), highlight their criticality beyond eliciting affective empathy, but also in driving further cognitive responses. This significant relationship between situational cognitive and affective empathy has implications for designing VR experiences that elicit emotional responses and validates the effectiveness of applying the method of self-reflection to confirm this relationship, alongside the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) to analyze the reflections.

The timeframe in which situational affective responses are captured can play an influential role in the outcome. Although affective empathy effects return to their original level over time (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024), further research is required to establish this period. Therefore, in this research, recording affective responses within a certain timeframe was critical to obtaining situational empathy results and determining the user’s situated emotions in that circumstance. In this research, situational empathy was recorded immediately following the experience through participants’ reflections within a timeframe of 5–10 minutes. The significant relationship between dispositional and situational affective empathy demonstrates the effectiveness of the applied timeframe in capturing situated affective responses for this research. In the framework for designing empathic journeys with VR in societal challenges proposed by Spek et al. (Reference Spek, Sleeswijk Visser, Smeenk, Gray, Ciliotta Chehade, Hekkert, Forlano, Ciuccarelli and Lloyd2024), although reflecting on the empathy experience immediately afterwards can be helpful in gathering actionable insights for designers, repeated experiences and reflection in VR are necessary to internalize and sustain behavioral changes in the long term. This suggests that repeating such experiences can serve as a tool for developing habitual change, and further research is required to ascertain whether both cognitive and affective empathy can be improved through repeated exposure (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024).

Methods of capturing and analyzing empathy

Responses obtained through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) (Table 5) resulted in a combination of powerful situational cognitive and affective responses across all levels of ranking, accentuating VR’s capability to elicit situational empathy. This supports empathy in VR research, highlighting first-person perceptive taking (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Bailenson, Weisz, Ogle and Zaki2018; Seinfeld et al., Reference Seinfeld, Arroyo-Palacios, Iruretagoyena, Hortensius, Zapata, Borland, de Gelder, Slater and Sanchez-Vives2018; Han et al., Reference Han, Shin, Ko and Shin2022) in combination with immersive narratives and contextual detail as positive influences on the resulting empathy (Georgiev et al., Reference Georgiev, Nanjappan, Georgieva, Gong, Holloway-Attaway and Murray2023; Hu et al., Reference Hu, Casakin, Georgiev and Otto2023). The results discussed in Sections “Dispositional affective and situational affective empathy” and “Situational cognitive empathy and situational affective empathy” highlight that although the VR experience facilitated both cognitive and affective empathy, the method of eliciting both dimensions differs, reflecting empathy’s nuanced nature. Figure 5 summarizes the primary method of eliciting and measuring situational cognitive and affective empathy and the respective tools applied in this research. Future work is encouraged to further empirically establish their validity and assess their representation across broader design contexts. Since cognitive empathy is predominantly elicited by environmental factors (Abramson et al., Reference Abramson, Uzefovsky, Toccaceli and Knafo-Noam2020), it is primarily elicited through situational means, in this case, the VR experience. Analyzing cognitive empathy is respectively effective through situational methods and tools, in this case captured by self-reflection post-VR, and subsequently evaluated through the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024). Since situated affective empathy is predominantly linked to humans’ empathic tendencies, the IRI can be used to measure and predict situated affective empathy outcomes. Additionally, in this research, the self-reflection method was effective in obtaining a measure of situational affective responses within the post-VR experience timeframe and in gathering insights into participants’ emotional experiences. Therefore, both dispositional and situational means were listed as methods for measuring situational affective empathy.

Figure 5. Methods and tools for eliciting and measuring situational cognitive and affective empathy.

The outcomes of this research demonstrate multiple benefits and implications of VR experiences in augmenting designers’ empathic design practices. Most of the challenges documented in the diary study (Section “VR experience design and development”) were also experienced by participants in both the pre-study (Section “Measuring situational empathy”) and the VR setting. Examples of such challenges include difficulties reading the menu, memorizing menu items, and calling the waiter. This indicates that both physical and virtual simulations effectively represented real-world experiences. Additionally, participants’ reflections in the VR study, such as “I was spending my birthday alone,” reveal emotional resonance with the users’ lived experience. Similarly, the quote “I have been having all these problems all these years, and I still have problems,” reflects perspective-taking and the ability to extend understanding beyond the brief duration of the simulation. Participants who were sensitive to the user group did not exhibit more varied empathy reflections than those without prior exposure. The VR experience retained a degree of novelty, even for those with a personal connection to vision impairment, because the VR experience extended beyond the physical aspects of vision loss, encompassing a holistic and situated experience of the persona being embodied, including emotional, cognitive, and social dimensions. Therefore, the VR experience effectively communicated users’ lived experiences, including emotional and temporal elements, highlighting its potential as an effective tool for fostering empathy that authentically represents user experiences.

Establishing empathy’s dimensional nature in VR and primary methods for capturing and measuring created opportunities for empathy development. Future work is encouraged to explore the potential of longitudinal cognitive and affective empathy development using the tools applied in this research. The statistically significant relationship between dispositional and situational affective empathy demonstrates the effectiveness of the self-reflection approach alongside the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) in obtaining an accurate measure of situational empathy, highlighting its potential value and applicability in post-analyzing empathy interactions in design research and practice. The findings also corroborate VR’s potential to facilitate powerful empathy responses through brief interventions, offering time efficiency. Additionally, dispositional empathic concern was linked to idea generation among engineering design students (Alzayed et al., Reference Alzayed, Miller and McComb2021), linking empathy to design creativity that is essential to design innovation. The advanced communication abilities offered by VR foster designer creativity (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Mehnen and Wodehouse2023a), creating potential for empathic outcomes from VR experiences to serve as a visualization tool for designers beyond that of deeply understanding their users’ needs and requirements, but also in catalyzing creative thinking. Through a shared database of empathic outcomes, designers’ responses can be translated into knowledge that is relevant for conducting subsequent human-centered design activities, such as defining design requirements and user needs. This approach contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how dispositional empathy correlates with situated outcomes by analyzing how its cognitive and affective components shape them. Furthermore, it offers an initial step toward improving the traceability of empathy in the design process, addressing the current need to determine its causal influence on design outcomes (Alzayed et al., Reference Alzayed, Miller and McComb2021; Chang-Arana et al., Reference Chang-Arana, Surma-Aho, Hölttä-Otto and Sams2022).

Limitations

Pretrials and prototyping are recommended to determine the right balance between what the contextual elements communicated to the participants in VR and their level of agency over the outcome of the virtual scenario. Limitations of the research include biases from participants related to self-reported measures (Van de Mortel, Reference Van de Mortel2008; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Fraley and Krueger2009) of dispositional and situational empathy. The self-assessment nature of measuring empathy may be susceptible to a degree of social desirability bias, highlighting the need to complement self-report measures with other methods, such as physiological measures. Although design research shows that shared interpersonal characteristics between designers and users can improve empathic accuracy, including gender and culture (Li and Hölttä-Otto, Reference Li and Hölttä-Otto2023), this research applies a first-person perspective approach, which seeks to foster empathic understanding through direct, embodied experience of the user’s experience. Therefore, immersing participants in simulated scenarios that replicate the user’s perspective suggests a closer prediction of the cognitive and emotional state of the vision-impaired client the participants were embodying, thereby providing a more accurate representation of the mental state of the vision-impaired client the participants were embodying. This bypasses demographic and cultural influences, grounding empathy through lived, situational engagement. Research also claims women have higher dispositional empathy scores than men (Gilet et al., Reference Gilet, Mella, Studer, Grühn and Labouvie-Vief2013); however, research analyzing empathy in VR contains uneven gender ratios, with more experiments having a higher percentage of female participants (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Gil2024). Nevertheless, it remains uncertain how such experiences, including gender influences, manifest when the self is involved through first-person perspective-taking, requiring further investigation. Although the sample was culturally diverse, this could be enhanced further by recruiting participants from multiple institutions and cultures. Future work of this research also requires enlarging the sample size, involving a gender-balanced ratio, to identify differences between genders. While the co-authors reviewed the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) results to ensure strong reliability, the interpretation of responses is still subject to a degree of subjectivity. Future research is encouraged to investigate the approach involving self-reflection and the Empathic Empowerment Scale (Grech et al., Reference Grech, Wodehouse, Brisco, Štorga, Škec, Martinec, Marjanović, Pavković and Škec2024) for other populations, including professional designers working in industry.

Conclusion

For the first time, this research provides a step forward toward determining the influence of humans’ innate cognitive and affective dispositional empathy and the empathic outcome derived from a contextual VR experience. This led to a deepened understanding of empathy’s nature and established methods and tools to capture and measure the resulting situational empathy. Through empirical research, participants were invited to take the virtual perspective of a user with severely blurred vision in a restaurant environment using VR. Their dispositional empathy was measured using the IRI (Davis, Reference Davis1980) before the VR experience, and self-reflection captured insights into their situated cognitive and emotional experiences after the VR experience. Through the participants’ reflections, a statistically significant relationship was obtained between dispositional empathic concern and situational affective responses, whereas dispositional cognitive empathy was not strongly linked to dispositional tendencies. This highlights how emotions are closely connected to humans’ inherent empathic disposition and the criticality of contextual elements, communicated through the VR experience in this research, in eliciting cognitive responses. Therefore, this research argues for VR’s potential in facilitating empathy development through repeated exposure to VR experiences. Findings also reveal a statistically significant relationship between situational cognitive and affective empathy, highlighting how internally generated emotional responses can drive further cognitive responses. The research findings provide several implications for design practice, concerning the structured methodological approach to experiencing and analyzing empathy that emphasizes self-reflection, time efficiency in eliciting powerful and holistic empathic engagement, and opportunities to develop empathy as a skill. Future work of this research aims to conduct a longitudinal analysis of dispositional and situational outcomes for long-term empathy training through VR interventions. Furthermore, this research informs the construction of VR experiences that evoke empathy through a blend of cognitive and emotional engagement. Future opportunities lie in determining the impact of virtual experiences for empathy within industrial and pedagogical design workflows and exploring diverse user experiences. Ultimately, this research lays the groundwork for understanding how empathy outcomes evolve into tangible empathy-driven, human-centered solutions that foster inclusivity and social value.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this research are openly available in Strathprints at https://doi.org/10.15129/e2e1ddb4-e26d-428e-9681-ce41e6ec5c2b

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This work acknowledges the support of the National Manufacturing Institute of Scotland (NMIS) and the Mac Robertson Travel Scholarship.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Amy Grech is a PhD candidate in the Department of Design, Manufacturing and Engineering Management (DMEM) at the University of Strathclyde. Her research interests include human-centered design, empathic design, and extended reality technologies. In her PhD research, Amy is pioneering new ways to enhance designers’ empathy toward their users through Virtual Reality (VR) experiences to support better product, service, and system design. Amy also has extensive experience working as a product development engineer in the automotive industry and has worked as a researcher with the National Manufacturing Institute Scotland (NMIS) Digital Factory.

Professor Georgi V. Georgiev is leading the Design Creativity group at the Centre for Ubiquitous Computing (UBICOMP), University of Oulu, Finland. His experience comes from institutions in Finland, Japan, and Bulgaria, with a PhD in Knowledge Science from the Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. His recent research focused on empowerment through digital materialization, digital technology-empowered design creativity, digital experiences enabling rehabilitation, AI in creative ideation, and neurocognition of design creativity. Georgi’s work bridges the gap between technology and human-centered design. His works include awards for contributions to empathic design and creativity research.

Dr Ross Brisco is a Lecturer at the Department of Design, Manufacturing and Engineering Management, University of Strathclyde, UK. Dr Brisco’s research interests include: Computer-Supported Collaborative Design; Design engineering education; Novel collaborative technologies, including AI and VR; Strategic technology selection; and Product design, development, and realization.

Dr Brisco joined the Design Society in 2015 and was elected to the advisory board in 2023. He is the early-career chair of the Design Education and Collaborative Design Special Interest Group. He joined the IED as a member in 2025, and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy – Advance HE in 2021.

Dr Andrew Wodehouse is a Reader in the Department of Design, Manufacturing and Engineering Management (DMEM) at the University of Strathclyde. He leads the department’s Design Research Group and is Theme Leader for Engineering Design undergraduate and postgraduate courses. His research addresses the creative design process, blending human-centered and computational approaches to realize holistic product experiences, interfaces, and geometries. He has led a range of UK Research and Innovation and EU-funded projects, is Co-chair of the Design Society’s Special Interest Group in Design Creativity, and is a Chartered Technological Product Designer.