Introduction

Hyperparasitism is a type of symbiotic, interspecific relationship involving parasites that act in a host role (Rohde Reference Rohde2002). This phenomenon has been reported only occasionally between two metazoan parasite taxa, with the first comprehensive review concerning mainly mycoparasites dating back to 1964 (Boosalis Reference Boosalis1964). In helminths, two-way hyperparasitic relationships have been observed. For example, as a hyperparasite, the polyopisthocotylan flatworm Cyclocotyla bellones Otto, 1823, infects the parasitic fish-infecting copepod Ceratothoa parallela (Otto, 1828) (Bouguerche et al. Reference Bouguerche, Tazerouti, Gey and Lou2021). In turn, helminths can be hosts for other parasite groups (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Kang, Le, Kwon, Jang and Choi2020; Cort et al. Reference Cort, Hussey and Ameel1960) including myxozoans (Dugarov et al. Reference Dugarov, Batueva and Pronina2011; Freeman and Shinn Reference Freeman and Shinn2011).

Myxozoans are a group of microscopic, obligate parasites consisting of over 3000 species, representing about 15% of cnidarian biodiversity (Whipps et al. Reference Whipps, Atkinson and Hoeksema2025). They have complex life cycles, with only some 2% demonstrated or inferred from molecular evidence, and these show alternation in spore stages between vertebrate and invertebrate hosts. Myxozoans are most frequently reported as myxospores from their intermediate fish hosts and rarely in other vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, waterfowl, and mammals (Bartholomew et al. Reference Bartholomew, Atkinson, Hallett, Lowenstine, Garner, Gardiner, Rideout, Keel and Brown2008; Dyková et al. Reference Dyková, Tyml, Fiala and Lom2007; Eiras Reference Eiras2005; Friedrich et al. Reference Friedrich, Ingolic, Freitag, Kastberger, Hohmann, Skofitsch, Neumeister and Kepka2000). Relatively few records exist for myxosporean infections as actinospores in their definitive invertebrate hosts – primarily annelids – where infection prevalence is typically <2% (Rangel et al. Reference Rangel, Castro, Rocha, Severino, Casal, Azevedo, Cavaleiro and Santos2016). To date, there are at least 14 marine actinospores, of which the myxospore phase remains unknown and the species is not formally described (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019; Yokoyama et al. Reference Yokoyama, Grabner and Shirakashi2012).

Hyperparasitism involving myxozoan-helminth interactions has been observed haphazardly and rarely. To date, myxozoan hyperparasitism accounts for five myxozoan-helminth combinations including two species of Fabespora Naidenova and Zaika, 1969 infecting different digenean flatworm species (Overstreet Reference Overstreet1976; Siau et al. Reference Siau, Gasc and Maillard1981); Myxidium giardi (Cépède, 1906) infecting the monopisthocotylan Pseudodactylogyrus bini (Kikuchi, 1929), a parasite of European eel (Anguilla anguilla L.) (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Aragort, Álvarez, Leiro and Sanmartín2004); and two species of Monomyxum Freeman et Shinn, 2011 infecting different monopisthocotylans (Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Yoshinaga, Ogawa and Lim2009; Freeman and Shinn, Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). Monomyxum incomptavermi (Freeman and Shinn, Reference Freeman and Shinn2011) infects Diplectanocotyla gracilis Yamaguti, 1953, a diplectanid parasite of Indo-Pacific tarpon (Megalops cyprinoides [Broussonet, 1782]) and an undescribed Monomyxum sp. infects Haliotrema sp., a dactylogyrid parasite of flathead (Platycephalus sp.) (as reviewed in Freeman and Shinn, Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). Two families were erected to accommodate lineages of Myxidium-like morphotype, which form distinct clades basal to the highly speciose lineage Kudoa Meglitsch, 1947, including Monomyxidae with Monomyxum as the type genus (Freeman and Kristmundsson Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015).

On the occasion of a ParasiteBlitz (de Buron et al. Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025), taxonomists with specializations across multiple parasite groups provide a comprehensive overview of the parasite diversity in a target ecosystem. As both invertebrates and vertebrates are screened, the likelihood of elucidating complex parasite life cycles increases dramatically. Parasites have been suggested previously as tags for trophic relationships (Lafferty et al. Reference Lafferty, Dobson and Kuris2006) and ecosystem function. Thus the ParasiteBlitz initiative not only increases the chances of elucidating life cycles in heteroxenous parasites but it indirectly provides insights into trophic relationships in ecosystems.

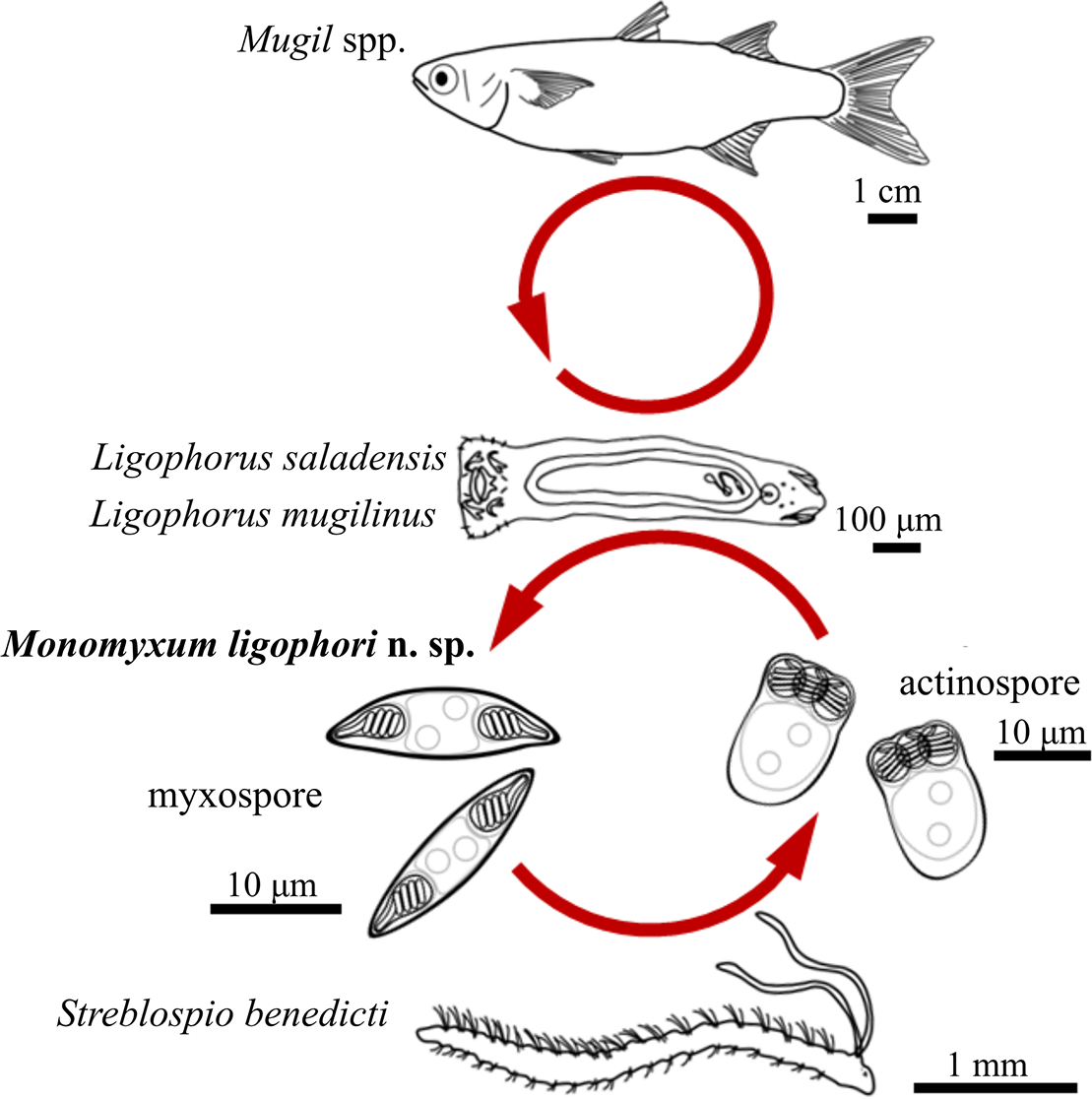

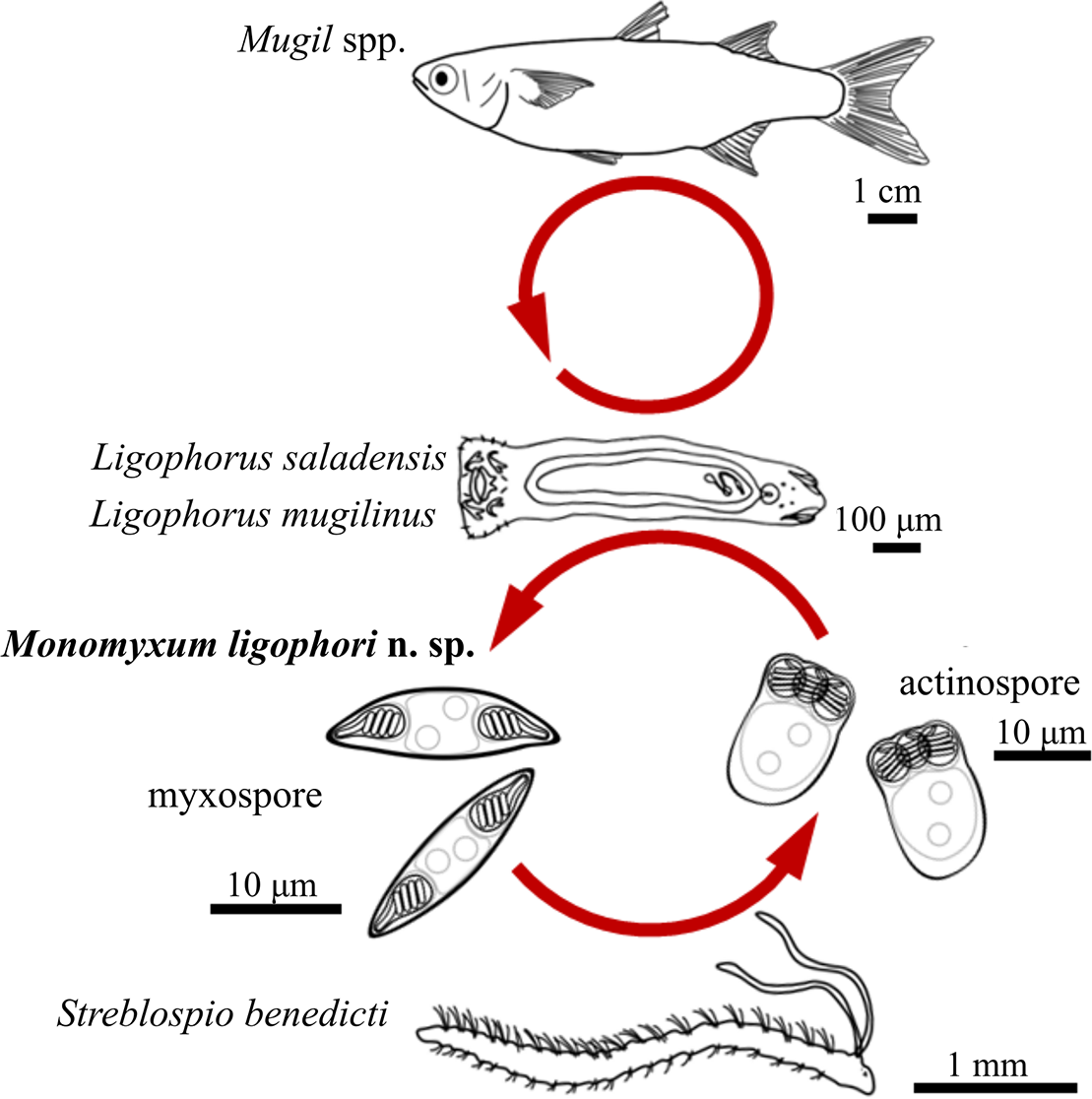

In the present study, we report the infection of a myxozoan as a hyperparasite of Ligophorus saladensis Marcotegui and Martorelli, 2009, and Ligophorus mugilinus (Hargis, 1955), monopisthocotylan flatworm intermediate hosts, together with proximal identification of its actinospore stage in a spionid annelid, Streblospio benedicti Webster, 1879. The life cycle connection is inferred from small subunit ribosomal DNA sequence identity and supported by physical proximity of both hosts in the tidal creek, thus most likely representing discovery of the first myxozoan life cycle that does not include a vertebrate host. Molecular data enabled us to test the hypothesis of a single evolutionary transition towards a hyperparasitic lifestyle of monopisthocotylan-infecting myxozoans.

Material and methods

Sample retrieval

Fish and annelids were collected as part of the ParasiteBlitz event at Stono Preserve, South Carolina, USA (see de Buron et al. Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025). Briefly, fish were collected in a tidal creek by net, and annelids were collected with their mud substrate from intertidal Spartina grass flats adjacent to the creek. Fish species of Mugilidae, Mugil cephalus Linnaeus, 1758 (n = 1 from impoundment and n = 4 from creek) and Mugil curema Valenciennes, 1836 (n = 8 from creek), were dissected and examined for external and internal parasites including squash preparation of different organ tissues. Annelids were sieved from the mud and examined whole in squash preparations. Monopisthocotylan individuals of L. mugilinus (n = 47), L. saladensis (n = 13), Ligophorus uruguayensis Siquier and Ostrowski de Núñez, 2009 (sensu WoRMS 2025) (n = 11) (Monopisthocotyla, Dactylogyridae), and Metamicrocotyla macracantha (Alexander, 1954) (n = 1) (Polyopisthocotyla, Microcotylidae) were bisected: with the anterior including the species-level diagnostic copulatory organs mounted in GAP (n = 62) on a slide for morphological evaluation, and the posterior part with attachment organs being stored in absolute ethanol for downstream molecular work (n = 19). Monopisthocotylan species identification was based on Sarabeev and Desdevises (Reference Sarabeev and Desdevises2014) and Marchiori et al. (Reference Marchiori, Pariselle, Pereira, Agnèse, Durand and Vanhove2015). Comprehensive survey results for major parasite groups will be presented in their respective ParasiteBlitz special collection papers. Monopisthocotylan specimens and annelids (n = 345) were checked for the presence of myxozoan infections using an Olympus BX51 microscope at 400–1000× magnification and digital images captured with an attached Canon DSLR of fresh material (where possible) otherwise from fixed specimens. Myxospores were described following Lom and Arthur (Reference Lom and Arthur1989) with minor terminological variation noted, and saccimyxon actinospores following Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019). To comply with the regulations set out in Article 8.5 of the amended 2012 version of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) (ICZN 2012), details of the species have been submitted to ZooBank. The Life Science Identifier (LSID) of the article is urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DC2B07B9-7F8C-4945-A28E-C818961A61FC

Molecular characterisation

Molecular characterisation targeted the small subunit ribosomal rDNA allowing comparison with previously described myxozoans. DNA extraction from monopisthocotylans followed the protocol described in Kmentová et al. (Reference Kmentová, Hahn, Koblmüller, Zimmermann, Vorel, Artois, Gelnar and Vanhove2021) with a final elution volume of 30 μL. DNA was extracted from the annelid host with a QIAGEN DNeasy kit using the Animal Tissue protocol, using half volumes of the digestion buffers ATL and AL, and a final elution volume of 60 μL. The 18S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers ERIB1 (forward; 5′−GTTCCGCAGGTTCACCTACGG−3′) and ERIB10 (reverse; 5′−CTTCCGCAGGTTCACCTACGG−3′) (Barta et al. Reference Barta, Martin, Liberator, Dashkevicz, Anderson, Feighner, Elbrecht, Perkins-Barrow, Jenkins, Danforth, Ruff and Profous-Juchelka1997) then each paired with internal primers ACT1r (reverse; 5′−AATTTCACCTCTCGCTGCCA−3′) (Hallett and Diamant Reference Hallett and Diamant2001), MYXGEN4F (forward; 5′−GTGCCTTGAATAAATCAGAG−3′) (Diamant et al. Reference Diamant, Whipps and Kent2004) to generate overlapping fragments.

The PCR for the amplification of myxozoan DNA sequences used 2xMangoMix (12.5 μL), 0.5 μL of the forward and reverse primers (0.2 μM), and 9.5 μL ddH2O with 2 μL of DNA extract, for a total of 25 μL per reaction. PCR cycling conditions: initial denaturation 2 min at 94°C, 30 cycles of 20 sec at 94°C, 30 sec at 53°C, and 1 min 30 sec at 72°C, final elongation of 7 min at 72°C, and cooling to 4°C. The amplified products were purified using the GeneJet Gel extraction kit and sequenced using the same primers as for the PCR reaction by Macrogen Europe. PCR for the myxozoan infection in the annelid sample was performed according to Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019), with PCR products sequenced at Oregon State University’s Center for Quantitative Life Sciences.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

We augmented the 18S rDNA alignment of myxozoan sequences from Freeman and Kristmundsson (Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015) and included our novel sequence data on Monomyxum and the saccimyxon data (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019) (see Table 1). Sequences were aligned using Muscle v5.1 under the Parallel Perturbed Probcons algorithm and with four threads (Edgar Reference Edgar2004) in Geneious v2025.0.2. Poorly aligned positions and divergent regions were removed with trimAl v.1.3 using the automated 1 option. The final alignment constituted of 1561 bp including gaps. The optimal substitution model was selected according to the Bayesian information criterion as implemented in ModelFinder in IQ-Tree (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. Reference Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, Von Haeseler and Jermiin2017). Tree topologies were estimated through Bayesian Inference (BI) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods using, respectively, MrBayes v3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Hohna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012) on the CIPRES Science Gateway online server (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010) and IQ-Tree v1.6.12 (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, Von Haeseler and Minh2015). Ceratonova shasta (GQ358729) and Myxidium gadi (GQ890673) were selected as outgroups due to their documented close relationship with histozoic marine myxozoans (Fiala and Bartošová Reference Fiala and Bartošová2010). BI used two parallel runs and four chains of Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations, run for 100 million generations with a burnin fraction of 0.25, sampling trees every 1000th generation. Convergence was assessed by the average standard deviation of split frequencies (<0.01 in all datasets) and the effective sample size (>200) using Tracer v1.7 for BI analyses (Rambaut et al. Reference Rambaut, Drummond, Xie, Baele and Suchard2018). Branch support values for the ML analysis were estimated using ultrafast bootstrap approximation (Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Chernomor, Von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2018) and Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio tests (SH-aLRT) (Guindon et al. Reference Guindon, Dufayard, Lefort, Anisimova, Hordijk and Gascuel2010) with 10,000 replicates (as recommended in the IQ-Tree manual). The resulting tree topologies were visualised in FigTree v1.4.4 (Rambaut Reference Rambaut2018).

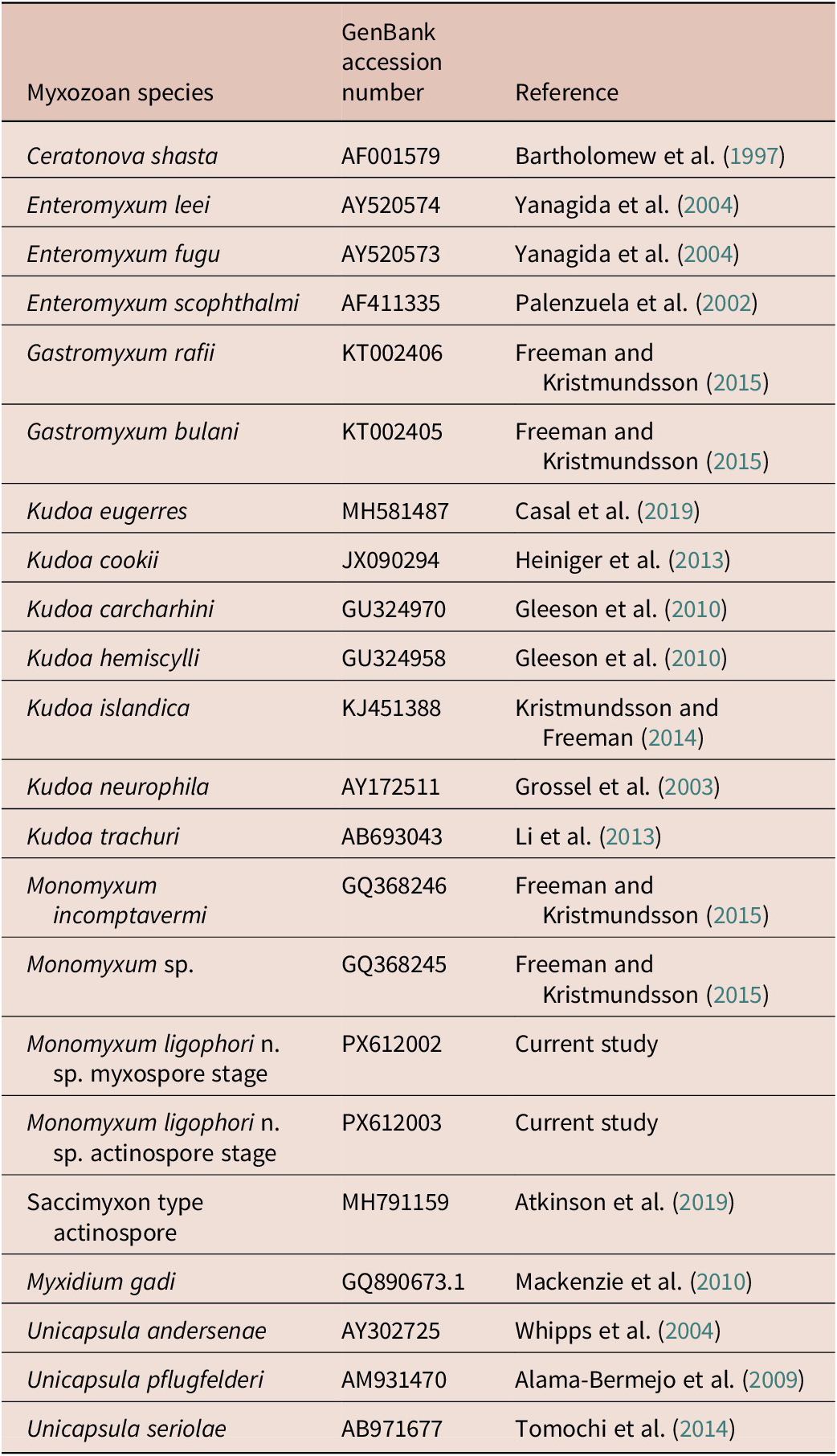

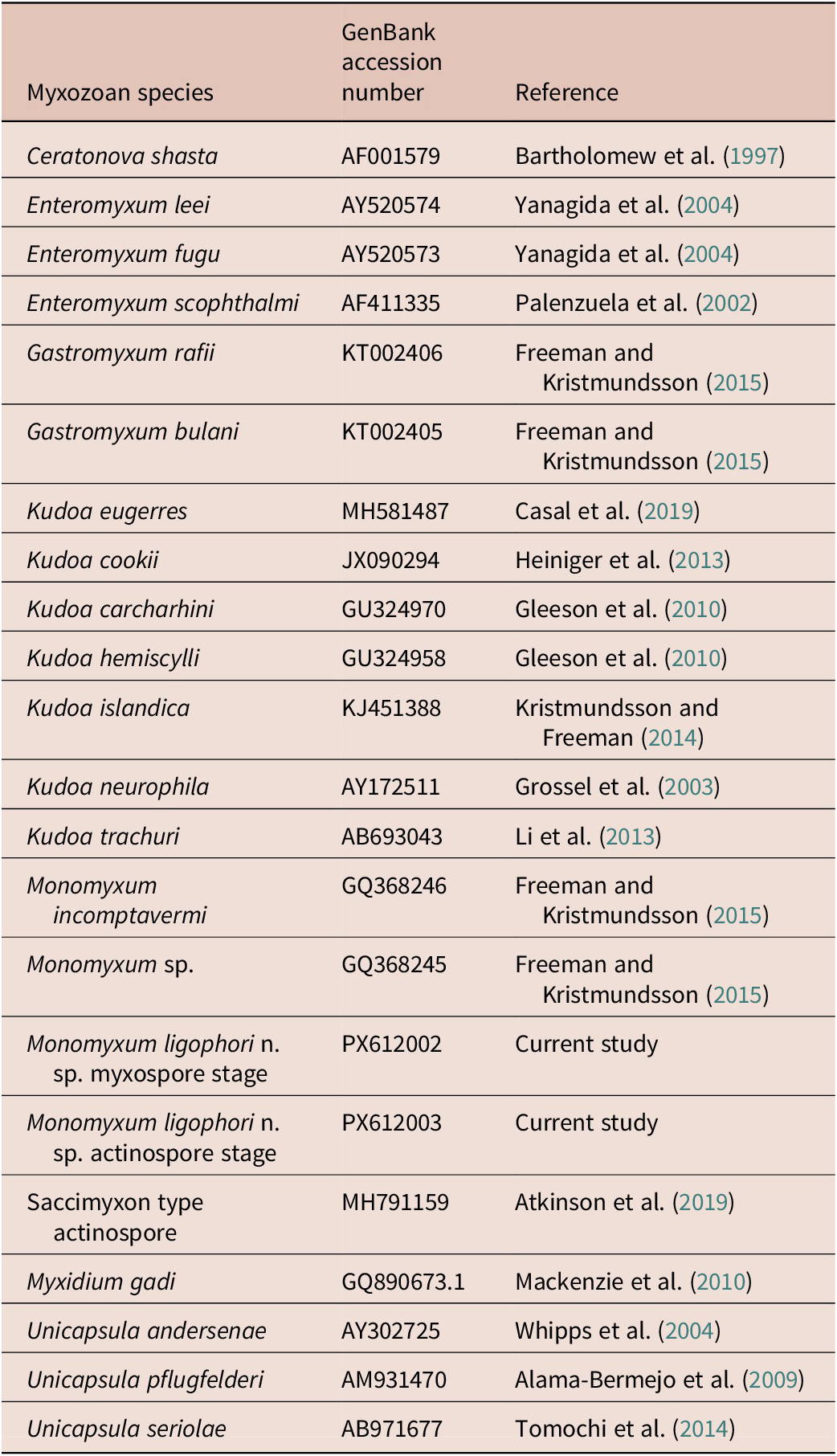

Table 1. GenBank accession numbers of 18S rDNA sequences used for the phylogenetic reconstruction in the present study

Results

Infection parameters

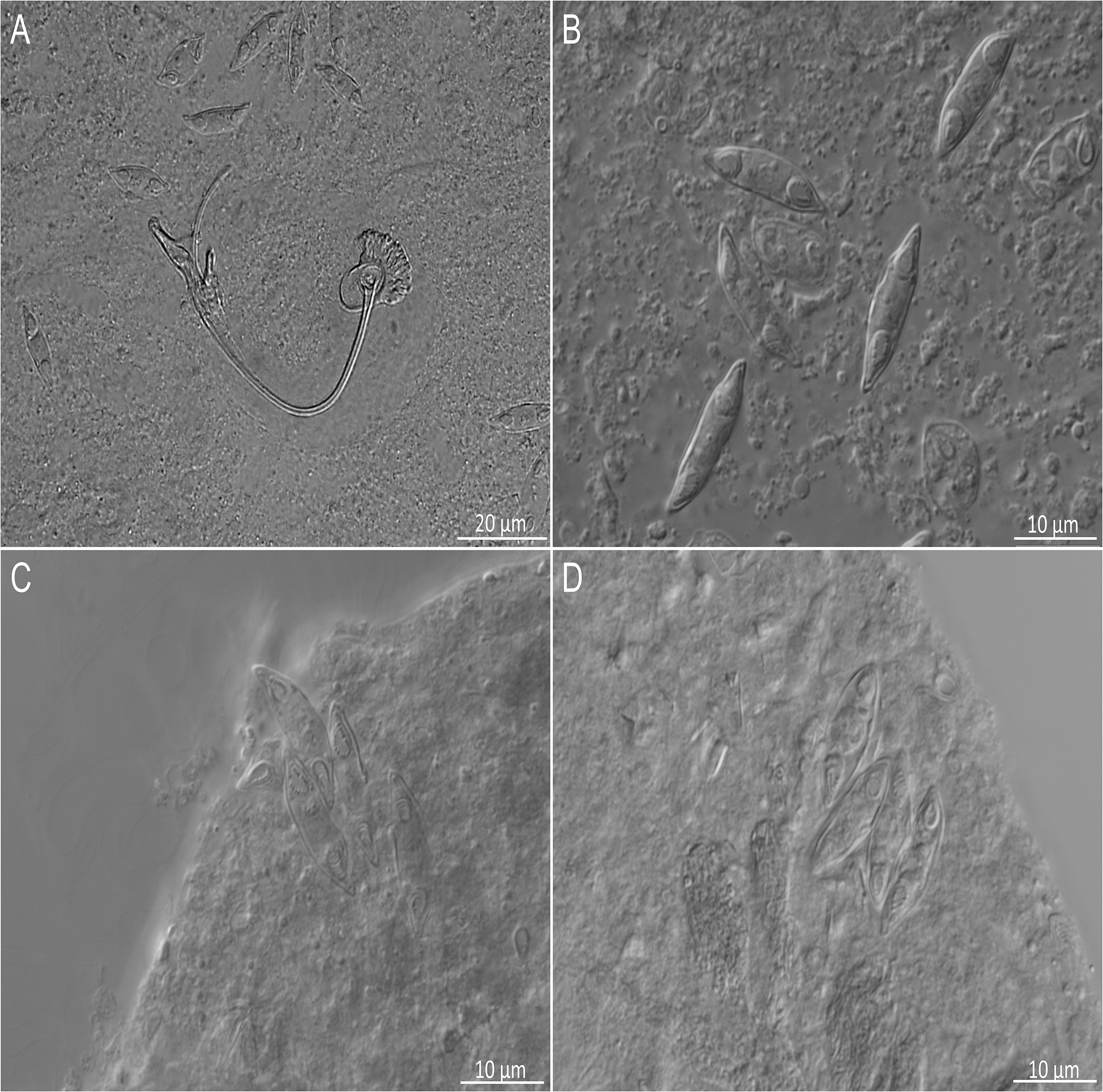

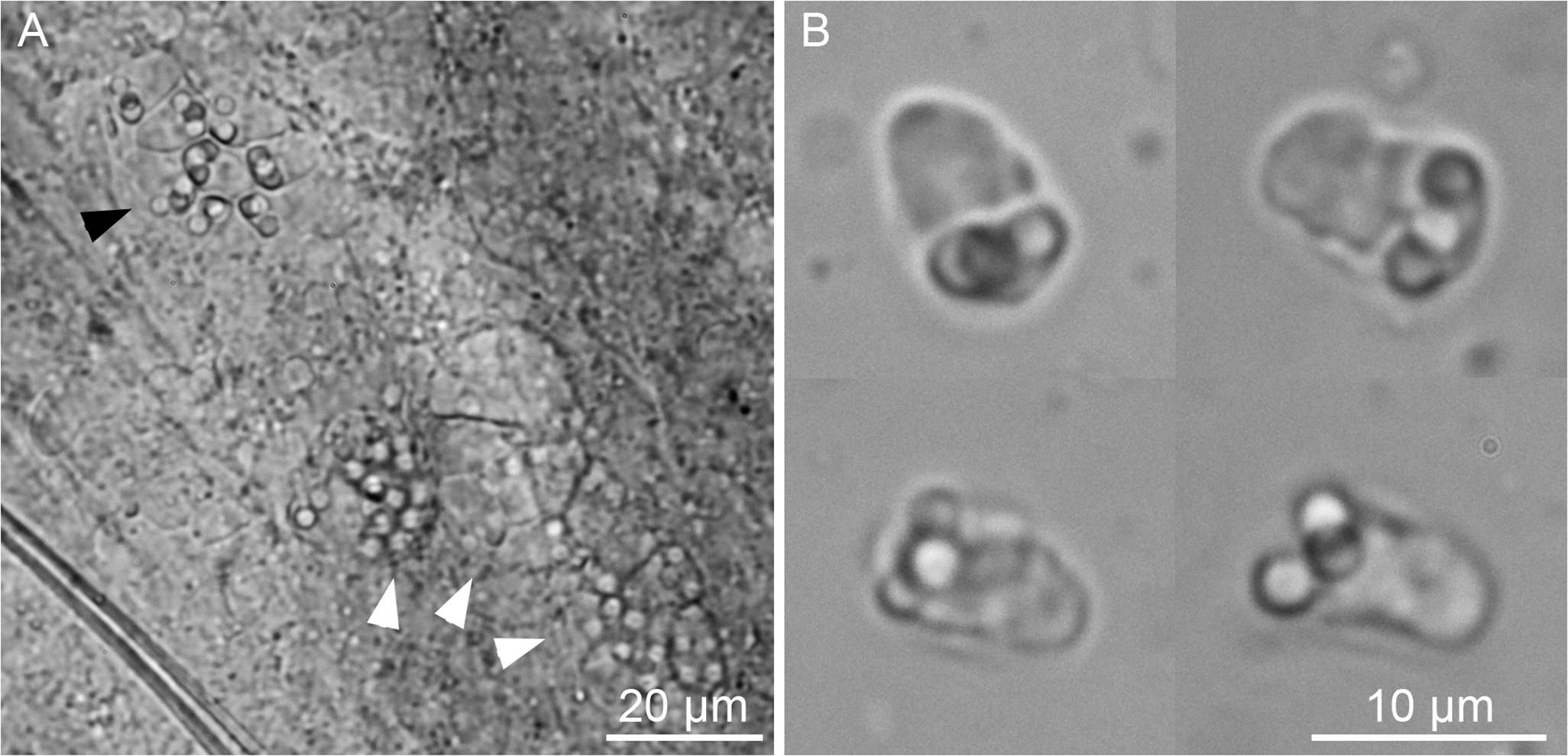

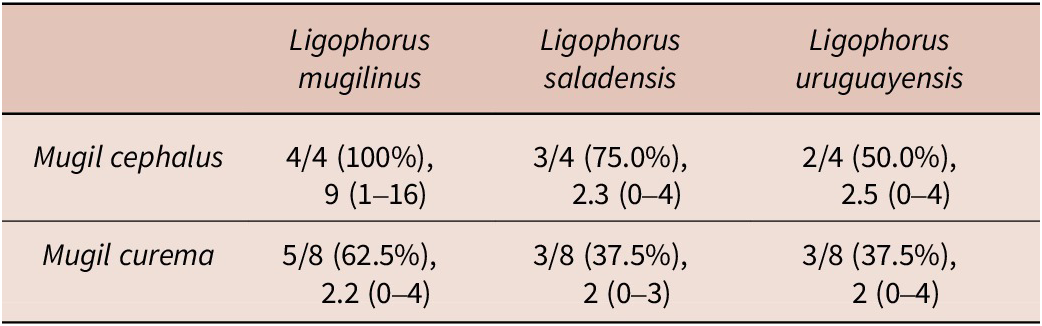

Four species of parasitic flatworms were found on the gills of mugilid fishes: monopisthocotylan individuals of Ligophorus mugilinus, L. saladensis, L. uruguayensis (Monopisthocotyla, Dactylogyridae), and a polyopisthocotylan, Metamicrocotyla macracantha (Alexander, 1954) (Polyopisthocotyla, Microcotylidae). Morphological examination revealed the presence of myxozoan hyperparasitism in two monopisthocotylan species: mature myxospores were observed in three monogenean-host species combinations, being L. mugilinus ex M. cephalus with a prevalence of 2.8%, L. saladensis ex M. cephalus with a prevalence of 14.3%, and L. saladensis ex M. curema with a prevalence of 16.7%, respectively, all recorded from a single locality. At the infrapopulation level of the monopisthocotylan host (per infected fish host individual), the prevalence of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. was 7.7% from L. mugilinus ex M. cephalus, 50.0% from L. saladensis ex M. cephalus, and 50.0% from L. saladensis ex M. curema. The prevalence of hyperparasitic infection was 12.5% ex M. curema and 40.0% ex M. cephalus across sampling sites. The overall prevalence of the myxozoan hyperparasite across different fish host species and sampling sites was 23.1%. The infection parameters of the monopisthocotylan hosts are summarized in Table 2. Additional visually negative specimens of Ligophorus spp., for which a DNA sample is available (n = 16), were Monomyxum-negative by PCR. All specimens of L. uruguayensis (n = 11) and M. macracantha (n = 1) were negative for myxozoan infection visually and by PCR (n = 5). No myxospores of Monomyxum were observed in any of the fish hosts or invertebrates by visual screening, in the broader ParasiteBlitz (de Buron et al. Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025). The myxozoan infection consisted of myxospores found throughout the body of all three infected specimens of Ligophorus spp. (Figure 1); while some paired spores were evident, no earlier developmental stages were observed. Measurements of myxospores of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. from each infected monopisthocotylan individual and from Monomyxum incomptavermi, the only other species of Monomyxum for which measurements are available, are presented in Table 3.

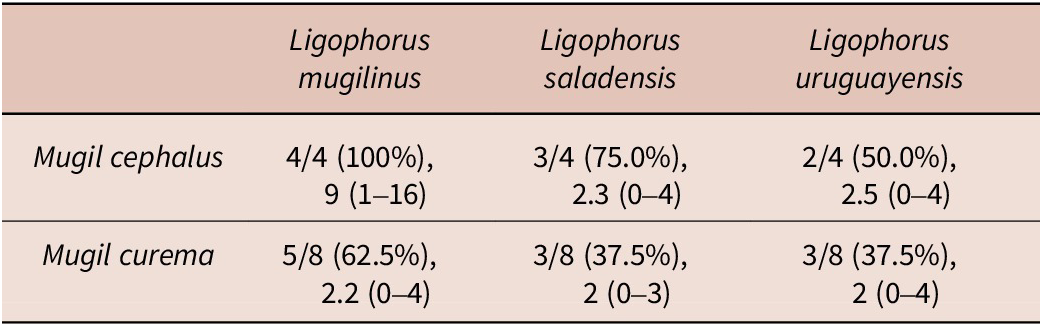

Table 2. Infection parameters of the monopisthocotylan species across different fish host species including number of screened/infected host individuals, intensity of infection, and range from creek locality (a single specimen of Mugil cephalus screened from the impoundment was not infected by monopisthocotylans). More information on the sampled localities are available in de Buron et al. (Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025)

Figure 1. Microphotographs of myxospores of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. scattered within the parenchym of A) Ligophorus saladensis ex Mugil curema with sclerotized parts of the male copulatory organ of the monopisthocotylan, B) Ligophorus saladensis ex Mugil curema, C) spores released from ruptured parenchymal tissues of Ligophorus saladensis ex Mugil cephalus, D) Ligophorus mugilinus ex Mugil cephalus.

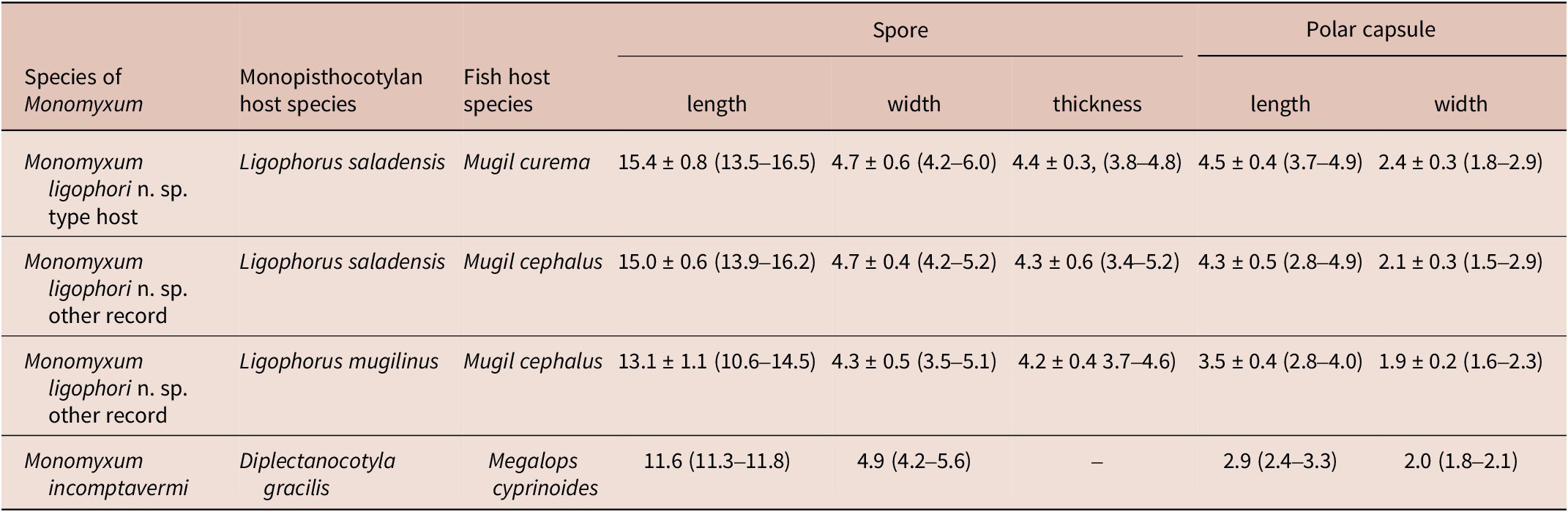

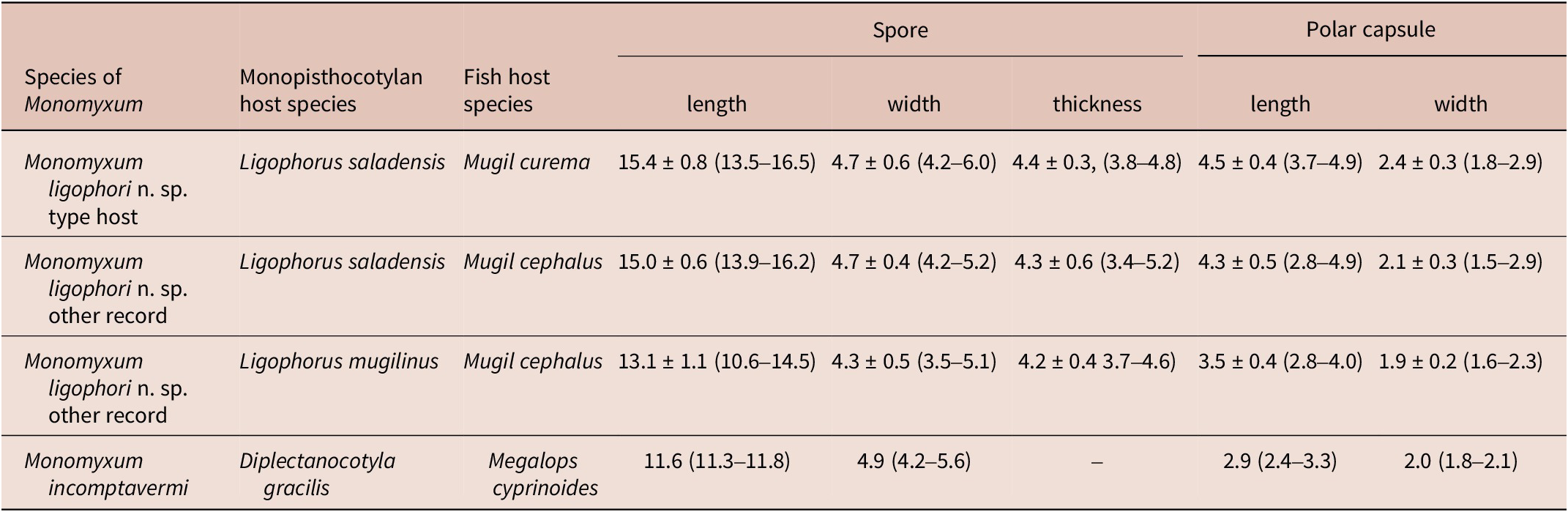

Table 3. Morphometric characterisation of myxospores infecting Ligophorus saladensis ex Mugil curema and ex Mugil cephalus, and Ligophorus mugilinus ex Mugil cephalus in the present study, and of the previously reported Monomyxum incomptavermi infecting Diplectanocotyla gracilis ex Megalops cyprinoides as published in Freeman and Shinn (Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). All measurements are presented in micrometres, as average, standard deviation, and range where available

We examined 345 annelids (128 Streblospio benedicti, 103 Manayunkia aestuarina, and 214 of undetermined species) and found only one overt myxozoan infection, which presented as saccimyxon actinospores and pansporocyst developmental stages in the tegument of S. benedicti (Figure 2). Measurements of fresh actinospores (in microns: average ± standard deviation, range, number measured): spore length 8.7 ± 0.5, 8.0–9.6, n = 10; spore width/thickness 5.8 ± 0.4, 5.1–6.7, n = 10; and polar capsules (nematocysts) spherical, diameter 2.1 ± 0.2, 1.8–2.4, n = 29. Morphology, morphometrics, annelid host, and DNA sequence data (see below) were consistent with the saccimyxon type of Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019).

Figure 2. Microphotographs of saccimyxon-type actinospores of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. within the tegument of the annelid Streblospio benedicti: A) 8-spore pansporocyst (dark arrowhead) and other less developed stages (light arrowheads). B) composite image showing four actinospores after release from host.

Taxonomic summary and type material

Class Myxosporea Bütschli, 1881

Order Bivalvulida Shulman, 1959

Suborder Variisporina Lom and Noble, 1984

Family Monomyxidae Freeman and Kristmundsson, Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015

Genus Monomyxum Freeman and Kristmundsson, Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015

Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. (with morphological characters of the genus)

Type (intermediate) host: Ligophorus saladensis (Monopisthocotyla, Dactylogyridae) (symbiotype parasitizing Mugil curema, symbio-paratype infecting Mugil cephalus (Actinopterygii, Mugilidae))

Additional host: Ligophorus mugilinus (Monopisthocotyla, Dactylogyridae) parasitizing Mugil cephalus (Actinopterygii, Mugilidae)

Definitive host: Streblospio benedicti Webster, 1879 (Polychaeta, Spionidae)

Type locality: Stono Preserve, South Carolina, USA (32.733475 N, –80.177849 W)

Localisation of myxospores: Parenchymal tissues of monopisthocotylan hosts.

Localisation of actinospores: Tegument of middle to posterior segments of annelid host.

Prevalence of myxospores: 16.7% of L. saladensis ex M. curema, 14.3% of L. saladensis ex M. cephalus, 2.8% of L. mugilinus ex M. cephalus

Prevalence of actinospores: 0.8% (1/128) of S. benedicti; 0.2% (1/345) of all polychaetes examined.

Etymology: The species epithet ‘ligophori’ refers to the genus name of the monopisthocotylan host species.

Zoobank registration number: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DC2B07B9-7F8C-4945-A28E-C818961A61FC

Type material, myxospores: A single specimen, mounted in glycerine ammonium picrate, of L. saladensis ex Mugil curema infected by Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. serves as holotype. A hologenophore (HU 1095) corresponding to a DNA voucher (GenBank accession number PX612002) and two other specimens of L. saladensis ex M. cephalus (HU 1096) and L. mugilinus ex M. cephalus (HU 1097) infected by Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. are assigned as paratypes. All types are deposited at the institutional collection of the Research Group Zoology: Biodiversity and Toxicology of Hasselt University (Diepenbeek, Belgium).

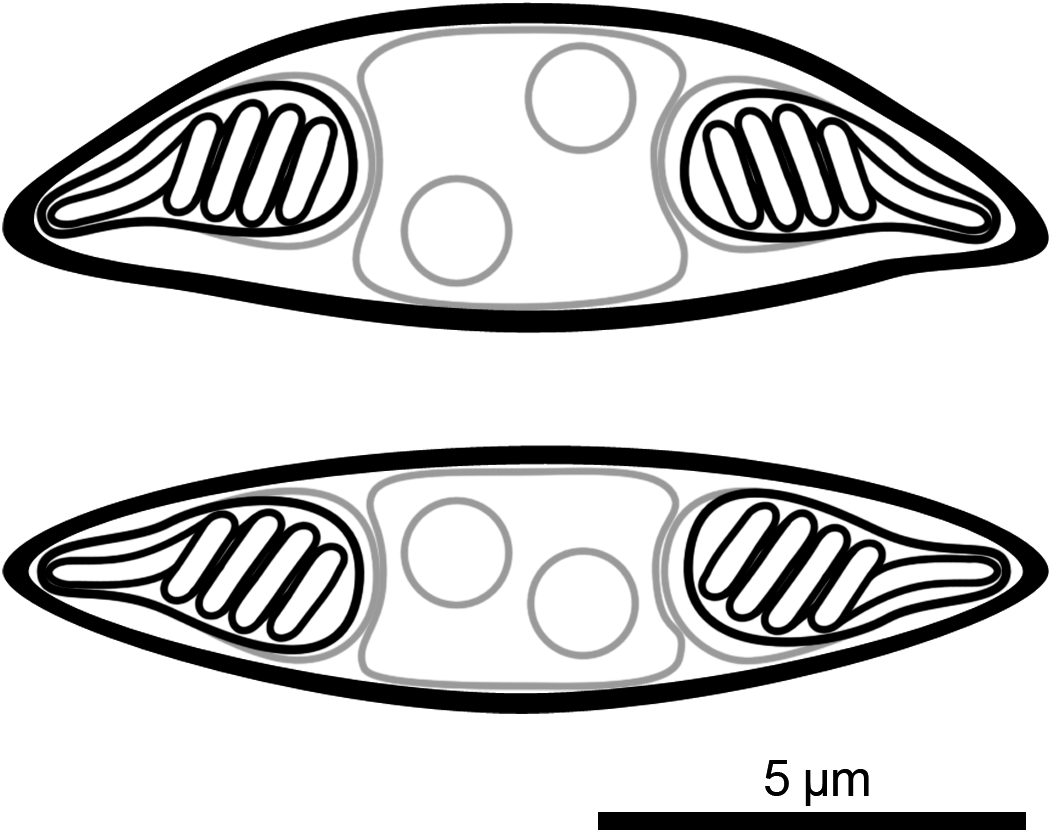

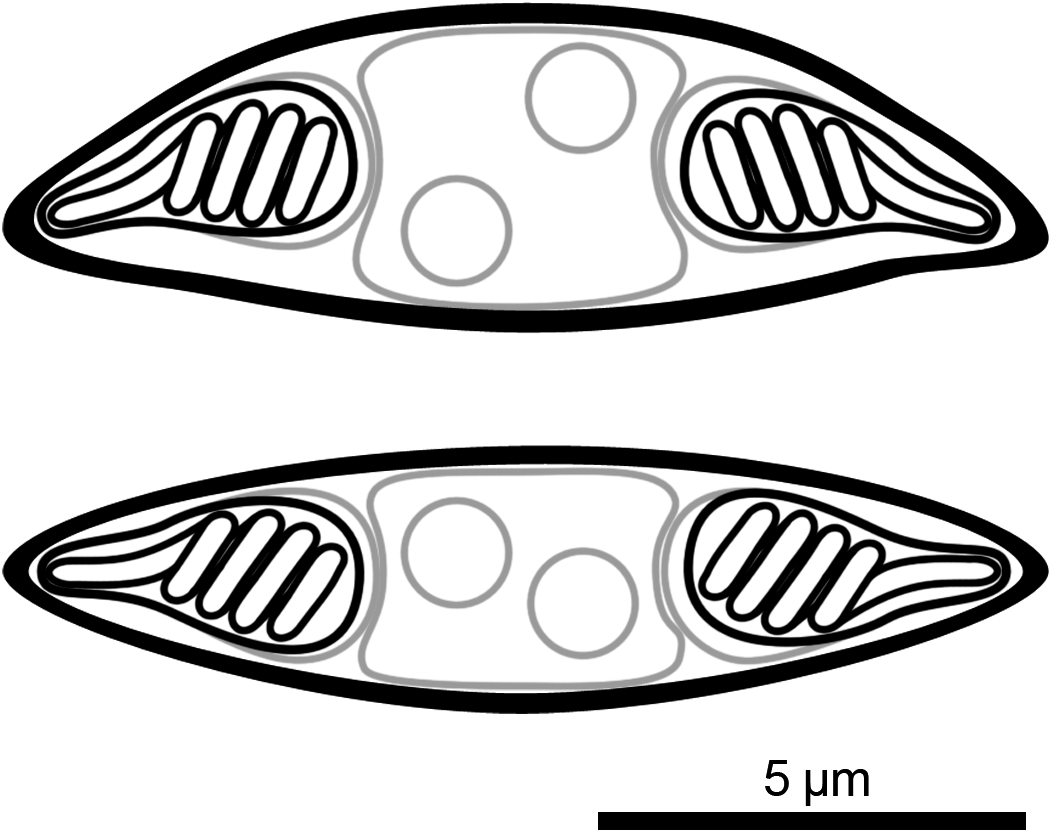

Description of myxospores: Spore fusiform, with binucleate sporoplasm, two equal pyriform polar capsules (nematocysts) located at ends of spore, polar tubules with four coils, spore valves smooth with suture line inconspicuous; morphometrics are presented in Table 3. Line drawings are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Line drawing of myxospores of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. in frontal/valvular view (top) and side/sutural view (bottom).

Description of actinospores consistent with that provided in Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019).

Differential diagnosis: Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. shows similar morphology of the myxospores as the only other described congener, M. incomptavermi with a fusiform shape. The species differ in number of coils in the polar tubules: Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. (n = 4) compared to M. incomptavermi (n = 3). The binucleate sporoplasm of M. ligophori n. sp. is in contrast with a single nucleus observed in M. incomptavermi. Myxozoan spores of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. are longer (>12 μm; fixed) compared to M. incomptavermi (<12 μm; fresh) while having similar width. The size variation in the length of spores reported from individuals infecting L. saladensis and L. mugilinus, respectively, are of a similar magnitude as the difference between M. ligophori n. sp. and M. incomptavermi but with overlapping ranges is noted and should be further investigated from additional fresh material if possible.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

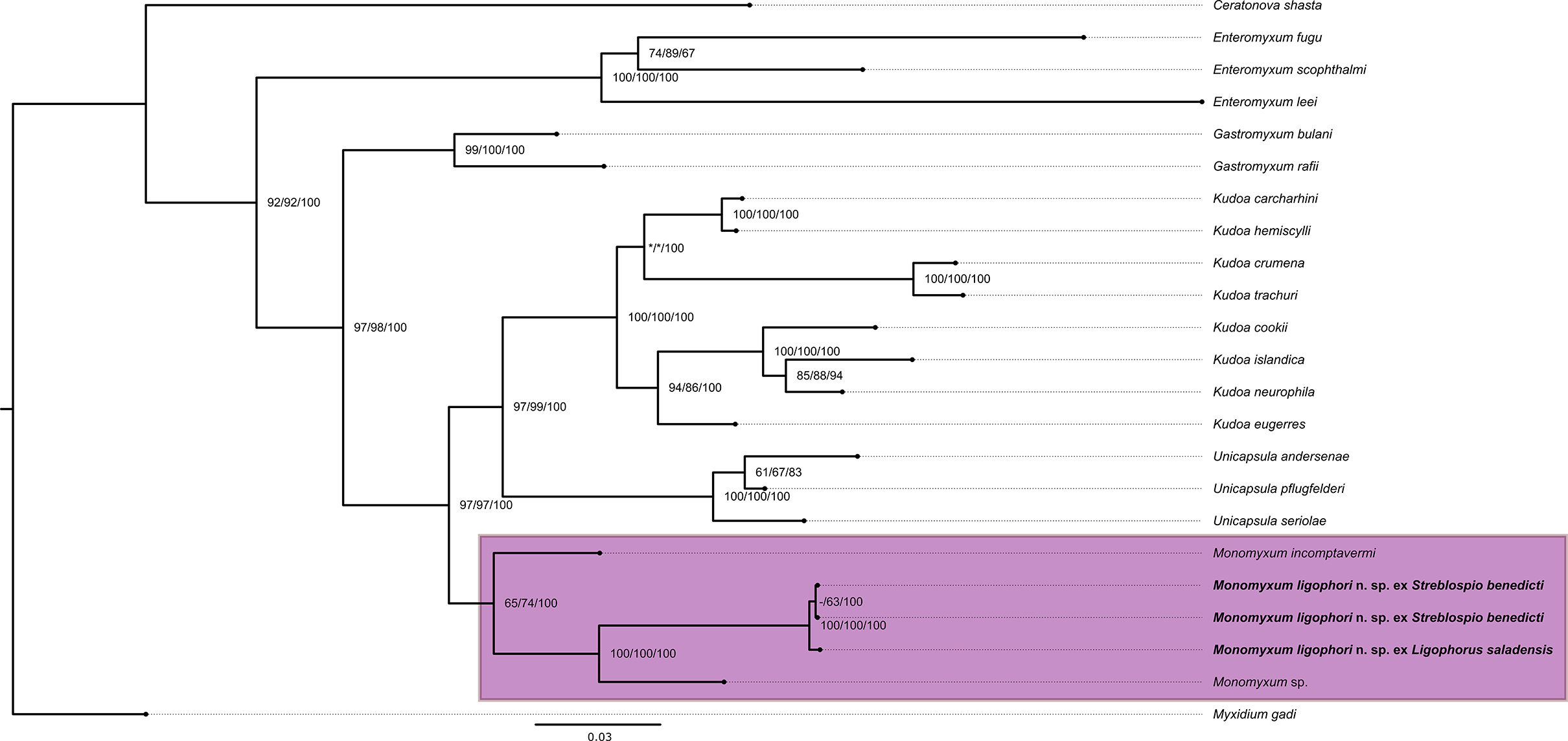

Molecular characterisation of the SSU rDNA of the myxospore type infection in the monopisthocotylan yielded 870 bp, and from the actinospores in the annelid host yielded 1686 bp. Sequences were almost identical to each other (a difference of two base pairs over the entire length of the fragment [0.2%]) and to the previously published sequence (MH791159) of the saccimyxon type described by Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019) from the polychaete host S. benedicti. Further, M. ligophori n. sp. differed 9.3% with M. incomptavermi (GQ368246) and 6.3% with Monomyxum sp. (GQ368245). Phylogenetic reconstruction revealed the position of M. ligophori n. sp. as part of a clade including the other Monomyxum species hyperparasitic in monopisthocotylan flatworms (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Phylogenetic reconstruction of the histozoic marine myxosporean lineages based on a portion of 18S rDNA region (1561 bp including gaps). The clade of hyperparasites of monopisthocotylan flatworms is highlighted. Support values are presented as Ultrafast bootstrap values/SH-aLRT/Bayesian posterior probabilities. The scale bar represents the estimated number of substitutions per site.

Discussion

In the present study, Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. is described from hyperparasitic myxozoan infections observed in two monopisthocotylan species infecting Mugil spp. collected from the ParasiteBlitz organized at the Stono Preserve, South Carolina (de Buron et al. Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025). Furthermore, we inferred the complex life cycle of the myxozoan by matching molecular identities of the hyperparasitic myxospore stage with an actinospore stage in a benthic spionid polychaete collected also during the ParasiteBlitz, and described previously from the same area (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019). Our study therefore provides evidence for a polychaete annelid host being part of the life cycle of a myxozoan hyperparasite of a fish-infecting monopisthocotylan flatworm, the first elucidated life cycle of a myxozoan that does not involve a vertebrate host (Figure 5). The branchial co-infection of myxozoan parasites in dactylogyrid monopisthocotylans showed no proliferation of the myxozoan in the fish host itself, as observed for other Monomyxum spp. (Freeman and Shinn Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). However, given the limited sample size of potential fish hosts, the hypothesis of a non-fish myxosporean life cycle could be tested in future studies by screening a broader range of fish hosts in the area.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of the life cycle of Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. including the host species involved and line drawings of parasite myxospore and actinospore stages.

Myxozoan hyperparasites of fish-infecting parasitic flatworms, trematodes or monopisthocotylans, have been reported in coastal habitats of Peninsular Malaysia (M. incomptavermi), Lake Hamana in Japan (Monomyxum sp.), a river in North-West Spain (M. giardi), estuarine areas on the east coast of the USA (Fabeospora vermicola Overstreet, Reference Overstreet1976), and a brackish lagoon at the Mediterranean coast (Fabeospora sp.) (summarized in Freeman and Shinn [Reference Freeman and Shinn2011]). Of these, four monopisthocotylan-myxozoan relationships have been described involving three species of monopisthocotylans. It is noteworthy that the above-mentioned reports stem mainly from coastal environments and euryhaline fishes. Our study at the Stono Preserve adds the first report of a hyperparasitic monomyxid myxozoan lineage from a coastal environment of the western Atlantic.

Reported prevalence of fish with myxozoan-infected monopisthocotylans varies among myxozoan species from 0.3% (M. giardi infecting P. bini ex A. anguilla, see Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Aragort, Álvarez, Leiro and Sanmartín2004) up to 50% (M. incomptavermi infecting D. gracilis ex M. cyprinoides, Freeman and Shinn Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). In the present study, the prevalence of hyperparasitic infection was 12.5% ex M. curema and 40% ex M. cephalus. The reported prevalence in the infrapopulation of the infected monopisthocotylan flatworms seems to vary between 30% in case of M. giardi infecting P. bini (Aguilar et al. Reference Aguilar, Aragort, Álvarez, Leiro and Sanmartín2004) and in M. ligophori n. sp., with 5% infecting L. mugilinus ex M. cephalus, 50% from L. saladensis ex M. cephalus, and 50% from L. saladensis ex M. curema, respectively. Unlike the apparent parasitic castration of their polychaete hosts (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019), development of monopisthocotylan hosts seems not to be affected, as we observed copulatory organs in all individuals with overt M. ligophori n. sp. infections. However, that is not the case of M. incomptavermi as poor integrity of parenchym and lack of copulatory organs were reported (Freeman and Shinn Reference Freeman and Shinn2011). In general, the sporadic nature of reports of myxozoan hyperparasitism in monopisthocotylan flatworms hinders any general conclusions on the frequency of this interparasitic type of relationship, and thus the degree of any pathogenic effect on the monopisthocotylan remains an open question.

Seasonal variations in infection by myxosporean stages have been reported across other marine histozoic myxozoan species including Kudoa inornata Dyková, de Buron, Fiala, and Roumillat, 2009, a species infecting seatrout Cynoscion nebulosus (Cuvier 1830), an economically and ecologically important fish in estuaries and harbours in southeastern North America (De Buron et al. Reference De Buron, Hill-Spanik, Haselden, Atkinson, Hallett and Arnott2017). The actinospore stages of M. ligophori n. sp. have been detected in the area of Charleston Harbour over the summer period (between May and July) and fall (November) (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019). The peak of myxosporean infection of K. inornata, a species found in the same locality as M. ligophori n. sp., correlated positively with temperature and fish densities (De Buron et al. Reference De Buron, Hill-Spanik, Haselden, Atkinson, Hallett and Arnott2017), a pattern detected for other histozoic myxozoan species (Henning et al. Reference Henning, Krügel and Manley2019). Other studies reported the infection patterns of Kudoa spp., being influenced by salinity levels (Dos Santos et al. Reference Dos Santos, Abrunhosa, Sindeaux-Neto, Monteiro and Matos2019; Jones and Long Reference Jones and Long2022). As reports on the myxosporean life stage of monomyxid myxozoans have all been one-time observations, including our study, seasonal patterns of the infection and the relation to seasonal peaks observed in other histozoic marine species hosts need to be verified.

Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. was the only myxozoan species found to infect polychaetes in the area, despite the presence of multiple other “marine clade” (likely polychaete hosted; Fiala et al. Reference Fiala, Hlavničková, Kodádková, Freeman, Bartošová-Sojková and Atkinson2015) myxozoan genera (i.e. Kudoa, Myxidium) encountered in fish sampled during the ParasiteBlitz (de Buron et al. Reference de Buron, Hill-Spanik, Atkinson, Vanhove, Kmentová, Georgieva, Díaz-Morales, Kendrick, Roumillat and Rothman2025). Specifically, the actinospore stage of M. ligophori n. sp. was encountered once, at a prevalence of 0.8% (1/128) in S. benedicti and 0.2% (1/345) in all marine annelids examined. This is an almost identical prevalence to that observed previously: 0.8% (6/734) of S. benedicti; 0.2% of 3,214 polychaetes examined (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Hallett, Díaz-Morales, Bartholomew and de Buron2019). The difficulty of discovering the annelid hosts of marine fish myxosporeans is well established (e.g. Hallett et al. Reference Hallett, Erseus and Lester1999, Reference Hallett and Diamant2001; Rocha et al. Reference Rocha, Alves, Antunes, Fernandes, Azevedo and Casal2020) and due to inherently low infection prevalence in the vast and diverse annelid biota in estuarine ecosystems.

As early phases of myxosporean infection are easily missed using visual examination alone, molecular methods have been developed for species of aquaculture or zoonotic importance (Funk et al. Reference Funk, Raap, Sojonky, Jones, Robinson, Falkenberg and Miller2007; Grabner et al. Reference Grabner, Yokoyama, Shirakashi and Kinami2012). This is exemplified in monopisthocotylans, where systematic barcoding revealed many morphologically cryptic infections compared with those monopisthocotylan individuals having fully developed myxospores (Morris and Freeman Reference Morris and Freeman2010). In the present study, we used molecular screening to confirm the absence of M. ligophori n. sp. in two other species of parasitic flatworms, L. uruguayensis and M. macracantha, co-infecting the fish hosts, thereby suggesting a certain level of host-specificity of M. ligophori n. sp. towards its monopisthocotylan host species even in the presence of a sympatric congener. However, given the relatively limited sample size of both fish and monopisthocotylan hosts, results on the host-specificity towards monopisthocotylans and absence in the vertebrate hosts should be further checked in the light of previously reported variable prevalences (Jones et al. Reference Jones and Long2019; MacKenzie et al. Reference MacKenzie, Kalavati, Gaard and Hemmingsen2005) and seasonality (Alama-Bermejo et al. Reference Alama-Bermejo, Šíma, Raga and Holzer2013) of myxosporean infections. The low prevalence of the M. ligophori n. sp. actinospore stage (a single infected individual out of 345 annelids examined) restricts any conclusions on its host-specificity towards the annelid host.

Our phylogenetic reconstruction shows the presence of three major myxosporean clades, corresponding with the results of previous studies (Fiala et al. Reference Fiala, Hlavničková, Kodádková, Freeman, Bartošová-Sojková and Atkinson2015; Fiala and Bartošová Reference Fiala and Bartošová2010; Kodádková et al. Reference Kodádková, Bartošová-Sojková, Holzer and Fiala2015). Monomyxum ligophori n. sp. is part of a moderately supported clade of monomyxid histozoic myxozoans that infect monopisthocotylan flatworms (Figure 3).

According to the WoRMS database (Whipps et al. Reference Whipps, Atkinson and Hoeksema2025), >3000 described myxozoan species exist whereas life cycles of only some 50 species have been resolved (Eszterbauer et al. Reference Eszterbauer, Atkinson, Diamant, Morris, El-Matbouli Mansour, Hartikainen, Okamura, Gruhl and Bartholomew2015). Most myxozoans are highly specific with regard to their vertebrate hosts (Molnár and Eszterbauer Reference Molnár, Eszterbauer, Okamura, Gruhl and Bartholomew2015). It has been suggested that trophic relationships and relative abundance of alternative hosts drive these associations between parasites, including myxozoans, and their hosts (Lootvoet et al. Reference Lootvoet, Blanchet, Gevrey, Buisson, Tudesque and Loot2013). The scarcity of known life cycles and corresponding unknown identity of non-fish hosts combined with the lack of genetic resources hindered tests on the origin of the hyperparasitic myxozoan lineages. Despite the close molecular similarity of species of Monomyxum and other marine histozoic lineages including Kudoa and Gastromyxum, our results confirm the previously suggested common origin of Monomyxum species infecting monopisthocotylan flatworms (Freeman and Kristmundsson Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015). In the present study, the first life cycle of any hyperparasitic myxozoan species is presented, supporting the previous suggestions on the involvement of additional invertebrate hosts in monomyxids as an alternative to teleosts (Freeman and Kristmundsson Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015). However, as infections of other fish hosts have been detected by molecular methods (Freeman and Kristmundsson Reference Freeman and Kristmundsson2015), the strict affinity of monomyxids towards monopisthocotylan hosts is supported only by a few taxa.

Acknowledgements

Fellow parasitologists and team members of the ParasiteBlitz namely I. de Buron (College of Charleston), K.M. Hill-Spanik (College of Charleston), S. Georgieva (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences), D.M. Díaz-Morales (University of Duisburg-Essen and Centre for Water and Environmental Research, Essen), M.R. Kendrick (South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Charleston), W.A. Roumillat (College of Charleston), and G.K. Rothman (College of Charleston and South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Charleston) are acknowledged for their crucial support in retrieval and screening of fish host specimens. The College of Charleston Foundation allowed usage of Stono Preserve. Dr. Matt Rutter (Academic Director of the Stono Preserve Field Station) is thanked for logistical support of the ParasiteBlitz event. We would like to thank all the people from the College of Charleston involved in the administrative and field support including Dr. Seth Pritchard, Dr. Eric McElroy, Dr. Courtney Murren, Pete Meier, Greg Townsley, Josie Shostak, Reagan Fauser, Maya Mylott, and Haley Anderson. Michelle Taliercio, Graham Wagner, Jordan Parish, Grace Lewis, and Kevin Spanik from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources in Charleston helped with collection of fish.

Financial support

This work was supported by a DIOS Incentive Fund Project, Hasselt University (M.P.M.V. and N.K., grant number DIOS/OEYLRODE/2022/001, contract number R-12947); the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Hasselt University (M.P.M.V., grant number BOF20TT06, M.T, grant number 23KP05VHOM and N.K., grant number BOF21PD01); the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (4255-FED-tWIN-G3 program, Prf-2022-049); a Department of Commerce NOAA Federal Award (grant number NA22OAR4170114); a Brain Pool programme for outstanding overseas researchers of the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant number 2021H1D3A2A02081767); a Tartar Research Fund, Department of Microbiology, Oregon State University (S.D.A.); and a USFWS award (grant number F22AP01952); infrastructure was funded by EMBRC Belgium – FWO project GOH3817N.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.