Introduction

Banghui, literally meaning “gangs and societies,” was a unique form of resilient grassroots extralegal organization that proliferated in China between the eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries. Such organizations originated as institutions offering protection as fictive kinship groups for individuals who had been marginalized under China’s patriarchal Confucian order (Liu Reference Liu2002: 244–47). During a period of chaos around the beginning of the twentieth century, banghui rapidly penetrated every corner of urban society, from local police forces to the high society of politics and business (Martin Reference Martin1996: 35). In its transformative period at the turn of the twentieth century, banghui presented features both as a localized subset of traditional protection society and as a Chinese variant of a global phenomenon of organized crime. Understanding banghui could significantly improve understanding of the nature of Chinese society during the Republican era, a transitional period that critically defined the trajectories of the Chinese communist regime.

The Green Gang (also written as Qingbang, Qing Pang, or Green Pang in English-language historical documents) was one of the largest and most paradigmatic banghui organizations. In the 1920s, the Shanghai Green Gang had an estimated membership of 100,000 people, almost three percent of Shanghai’s urban population (Martin Reference Martin1996: 35). The gang appeared in numerous seminal works on Chinese politics during the Republican period (Marshall Reference Marshall1976; Perry Reference Perry1980; Coble Reference Coble1986; Honig Reference Honig1992; Wakeman Reference Wakeman1995; Hershatter Reference Hershatter1997; Lu Reference Lu1999; Zanasi Reference Zanasi2006; Yeh Reference Yeh2007). These historical studies consider the Green Gang as a Chinese group analogous to urban organized crime elsewhere and provide abundant information on how criminal enterprises – from narcotic trafficking to gambling houses and brothels to kidnapping and extortion to labor racketeering – financed the gang’s main activities. They generally attribute the success of the gang to a weak nationalist state and collusion between famous gang leaders, the Chinese Nationalist Party (GMD) and the Shanghai business world.

The analogy between banghui and urban crime syndicates applies not least in the fact that, much like in Italy, Japan, and the United States, alliances between extralegal organizations, political rightists, and business were and are common in China. The social and political instability of the nascent republic had created demands for criminal protection and bourgeoning unregulated markets, which nurtured rampant gang activities, a familiar pattern observed in organized crime worldwide.

Nonetheless, approaching Shanghai Green Gang primarily as a criminal enterprise does not fully explain why it expanded so widely and became so powerful. The republican state did not consider banghui as primarily “criminal” organizations, unlike their counterparts in other parts of the world and despite their deep involvement in illicit activities. Newspapers and official documents categorized the Green Gang as a “mass organization,” together with native-place associations, trade associations, religious organizations, and camaraderie groups.Footnote 1 Local society and multiple political authorities tolerated and even promoted the Green Gang over the first half of the twentieth century (Marshall Reference Marshall1976). While once-significant social organizations such as guild halls and trade associations gradually weakened or were replaced by officially sanctioned organizations with similar functions, the Green Gang grew rapidly (Goodman Reference Goodman1995). It and other banghui organizations soon became an indispensable part of the texture of republican society.

This article suggests that it was Shanghai Green Gang’s active cultural work that made possible the level of tolerance and interdependence that it obtained with the nationalist state and other political actors. Revisiting a variety of archival materials, this article brings different interpretations of the gang’s development in dialogue. Synthesizing two main camps of literature – the theses of market competition and of cultural continuity – I use Green Gang’s self-legitimation claims as a point of entry to understand the organization’s unique development. Publicly legitimizing its use of violence by articulating violence as disciplinary, redistributive, and nationalistic, this banghui organization successfully expanded and persisted through frequent regime changes during the first half of the twentieth century. Together with Green Gang’s involvement in state building and resource extraction, the cultural reframing of violence contributed to the organization’s prominence and led multiple political authorities to promote it to an exceptional degree.

This article proceeds as follows. First, it revisits the historical and sociological debates around the expansion of extralegal groups. Second, it provides a brief sketch of the organizational histories and characteristics of Chinese banghui and a sociopolitical background of the period. Then, using the Shanghai Green Gang as an exemplary case of banghui, it illustrates how the self-articulated culture of violence within and beyond the Green Gang reflected the nature of the organization itself and the relationship between state and society. It concludes by discussing the theoretical and empirical implications of the case of Green Gang.

Market, state, and culture: bridging the two images of Green Gang

Rationalist approaches to extralegal organizations understand their development as primarily driven by non-ideological instrumental interests in relation to the state and market. Under this framework, extralegal organizations are essentially economic enterprises. In some cases, they thrive as providers of illegal products, using violent means against or colluding with law enforcement to ensure they can facilitate gambling, prostitution, narcotics, and other illegal services and products. In other cases, these organizations promote and sell protection where the state has either failed to exercise its own monopoly over the use of violence or its service proves more expensive (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1996; Varese Reference Varese2001, Reference Varese2006, Reference Varese2011; Slade Reference Slade2012).

Extralegal organizations produce commodities – illegal products or private protection – through the use of violence. They therefore form, grow, or dissolve following market laws of supply and demand for the commodity they produce and/or distribute. This feature distinguishes them from traditional protection societies, which provided protection primarily for internal organizational members who were usually dislocated or marginalized populations and whose violence was considered defensive against abusive external forces. From the rationalist perspective, violence is either an important means that extralegal organizations use to protect their economic interests or it is a commodity for sale. These organizations “exploit and thrive on the absence of trust, by providing protection in the form of enforcing contracts, settling disputes, and deterring competition” (Gambetta Reference Gambetta2011). Conflicts between organizations to protect their monopolies on economic transactions are usually brutal and territorial (Varese Reference Varese2001).

Following the rationalist perspective, scholars study extralegal groups across the world as market-based, profit-oriented organizations (Milhaupt and West Reference Milhaupt and West2000; Chu Reference Chu2002; Frye Reference Frye2002; Hill Reference Hill2003; Tzvetkova Reference Tzvetkova2008). They see these organizations as a consequence of modern capitalist development, and their growth as dependent on their ability to adapt to specific market features. In the case of Shanghai Green Gang, historians have also attributed its rapid expansion both to freewheeling markets for opium, gambling, and prostitution and to lack of effective social control by the republican state when large numbers of rural migrants flooded into the city to escape natural disasters and civil dissonance at the turn of the century (Goodman Reference Goodman1995; Wakeman Reference Wakeman1995; Martin Reference Martin1996).

The market-centered approach to studying extralegal organizations is not wrong, but it is inadequate to explain the development of the Green Gang. The gang was actively involved in illicit businesses after the Revolution of 1911, but it was not primarily organized to enhance earnings or create a market for criminal protection. It had a long history as a protection society for marginalized populations, resisting military conscription, assisting with communal and religious services, mobilizing local rebellions against the imperialist government, and other activities for mutual aid.Footnote 2 Understanding the state and extralegal organizations as competitors in a market for protection might ignore the multiplicity and complexity of the relationships involved, which include interlocking criminal, legitimate, and personal networks (Briquet and Favarel-Garrigues Reference Briquet, Favarel-Garrigues, Briquet and Favarel-Garrigues2010; Smith and Papachristos Reference Smith and Papachristos2016).

In contrast to the rationalist approach, scholarship taking the culturalist approach has depicted Chinese banghui as an outgrowth of late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century secret societies (Cai Reference Cai1993, Reference Cai2009; Ownby Reference Ownby1996; Bai Reference Bai2002; Qin Reference Qin2004, Reference Qin2009, Reference Qin2011, Reference Qin2013).Footnote 3 This line of research argues that the Green Gang was an amalgam of secret societies and religious sects for mutual aid and mutual protection. It appreciates the historical legacy of the gang, emphasizing its culture of fraternity, loyalty, and ritualistic practices. One feature that distinguished Green Gang from other banghui organizations was its relational core of vertical master-disciple tie, while other banghui groups centered on horizontal brotherhoods (Cai Reference Cai1998: 219–21). In the Green Gang, the master-disciple relationship was regarded as tantamount to the relationship between father and son and strictly regulated by the codified principles of filial piety. The majority of the gang code was designed to regulate the master-disciple relationship much as Confucian ethics did, specifying relationships between prescribed roles (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1990).

Within the cultural camp, there are disagreements about the Green Gang’s relationship with larger society and the state. Viewing “secrecy” as a central mechanism to maintain group cohesion and solidarity, Cai (Reference Cai1993: 21) and Qin (Reference Qin2009: 3) depict banghui as “a social cancer,” an outlaw enclave that was isolated from mainstream society. In contrast, as Zhou and Xia (Reference Zhou, Xia and Cai1998: 221) suggest, banghui was culturally “symbiotic” to the mainstream society. Replicating the Confucian patriarchal hierarchy, these groups formed fictive kinships not designed to challenge existing cultural rules and norms, despite their antagonism toward the state (Ownby Reference Ownby1996). Overall, the cultural approach emphasized the meanings of the gang’s rituals and symbols in explaining the organization’s development and persistence for centuries.

The two portrayals of the Green Gang in historiography – a modern criminal syndicate that came out of an emerging capitalist economy versus a cultural succession of traditional secret society – are so distinct that their proponents often speak past each other. Revisiting the two camps of literature comparatively, this article intends to bridge them and provides a synthesized perspective for understanding the rampant expansion of the Shanghai Green Gang and its deep roots in republican politics. I focus in particular on the gang’s legitimation of its own use of violence based on internal and cultural-cognitive means (Deephouse et al. Reference Deephouse, Bundy, Tost, Suchman, Greenwood, Oliver, Lawrence and Meyer2017) – that is, on organization members’ strongly held perception that their behavior is appropriate. I call this self-legitimation. The degree of cultural alignment of an organization’s behavior with dominant social norms and values determines its internal legitimacy (Meyer and Scott Reference Meyer and Scott1983; Scott Reference Scott1995). Through self-legitimation, the power holder obtains a favorable view of its own use of force, whether the power holder is war-waging nation states (Schoon Reference Schoon2014), police (Bradford and Quinton Reference Bradford and Quinton2014), or extralegal groups (Siniawer Reference Siniawer2012).

Understanding Green Gang’s self-legitimation of violence is essential in coupling the rationalist and the culturalist perspectives. As a core concept in the rationalist perspective, violence sustains an extralegal group’s attempts to exert monopolistic control over the whole market for illegal products or criminal protection, in competition with the state and/or with other armed groups. For its violence to be commodified, transacted, or co-opted, however, an extralegal group must share some of the cultural expectations of the larger society (Gambetta Reference Gambetta and Gambetta1988; Armao Reference Armao, Allum and Siebert2003). If the prescribed scenarios of using violence by extralegal groups violate mainstream values too much, the state often had no choice but to suppress the violent actors to maintain its own legitimacy (Collins Reference Collins2011). In other words, for the state to tolerate and to collude with them, extralegal groups must gain certain types of consent from the public to infiltrate legitimate society. This is where the culturalist perspective can chime in and supplement the rationalist image of Chinese banghui in the early twentieth century.

The culturalist approach suggests that the banghui’s violence was a response to “violent attacks on the region by outside forces,” particularly from the imperial government (Ownby Reference Ownby1996: 15). When state penetration was relatively weak in late imperial China, officials sometimes tolerated violent actions that they interpreted as “normal” such as feuds between clans, while cracking down on forces outside “the known structures of rural society” (Ownby Reference Ownby1996: 27). In other words, as long as the banghui did not challenge the existing order and its violence did not get out of hand, the Qing government turned a blind eye to it.

The culturalist interpretation of violence was mainly built on evidence from the banghui’s rural development in late imperial era. After the 1911 Revolution the republican state tried to extend direct administrative apparatus into society, especially in urban centers. The coexistence of the state and extralegal organizations in urban centers such as Shanghai was unprecedented and became formalized. Relying on evidence from the twentieth century, I bring the culturalist approach in dialogue with the rationalist perspective here to understand how banghui violence was framed in the new era that made its commodification and possession by nonstate actors possible.

The Shanghai Green Gang underwent a messy process in the twentieth century as a traditional protection society for dislocated individuals that had become a modern urban extralegal organization bringing together disparate social worlds. As a protection society, the gang’s use of violence was considered defensive and operated territorially; when its violence became commodified like urban organized crime elsewhere, it became aggressive, pliable, and universal. It was during this transition that the gang engaged most actively in the cultural work of publicly justifying its use of violence. The ways in which gang members articulated the use of violence reflect their understanding of the mainstream cultural expectations, both as market players, criminal entrepreneurs, and political actors.

These articulations around violence are also important because they shed light on the enduring tension between Chinese orthodox culture that generally dishonors violence and various countercultures that “convey a different normative message about the desirability and appropriateness of violent behavior” (Lipman and Harrell Reference Lipman and Harrell1990: 12). As a result, examining the prescribed situations in which the use of violence was legitimized, encouraged, and even glorified by the twentieth century Shanghai Green Gang can provide a more comprehensive picture than the rationalist perspective provides, and further advance understanding of the continuity and changes of the moral underpinnings of the Republican society.

In the following sections, I will demonstrate that the values of discipline, knight-errant spirit of social justice, and protecting Chinese nation were the core of the Green Gang’s culture of violence and were essential in the gang’s negotiations of its position within mainstream society and with a variety of sovereign powers.

Materials and methods

Primary sources on historical gangs and secret societies are generally scarce and fragmented because of the secretive nature of these groups. For this reason, I use the “targeted primary investigation” strategy favored by historical sociologists to select and construct the narrative in this study (Skocpol Reference Skocpol and Skocpol1984; Mayrl and Wilson Reference Mayrl and Wilson2020). I first examined existing studies of Chinese political and urban history where the Shanghai Green Gang make an appearance and the primary evidence about the gang on which these studies have used (Marshall Reference Marshall1976; Perry Reference Perry1980; Coble Reference Coble1986; Honig Reference Honig1992; Cai Reference Cai1993, Reference Cai2009; Wakeman Reference Wakeman1995; Ownby Reference Ownby1996; Hershatter Reference Hershatter1997; Lu Reference Lu1999; Bai Reference Bai2002; Qin Reference Qin2004, Reference Qin2009, Reference Qin2011, Reference Qin2013; Zanasi Reference Zanasi2006; Yeh Reference Yeh2007; Clinton Reference Clinton2017). Then I reinvestigated all these primary materials previously used by other studies. I also conducted original archival research at the Shanghai Municipal Archives (SMA) and the online Shanghai Municipal Police Archive (SMPA). The targeted-primary strategy is particularly useful when primary sources are scarce, and it may “build new findings out of primary sources previously inadequately analyzed” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol and Skocpol1984: 383).

Information on the Green Gang is scattered around the massive SMA collections. Documents on government offices, banks, industries, universities, and civil society organizations during the Republican period (SMA-Q), trade associations (SMA-S), foreign settlements (SMA-U), and miscellaneous publications before 1949 (SMA-Y) provide information about the gang’s bosses and their enterprises. These documents are mostly in Chinese.

The SMPA contains administrative documents of the British-run police force based in the international settlement in Shanghai. Although police records are popular sources for the study of extralegal groups, I used the SMPA not because it tracked the gang as a criminal organization but because its records contain detailed observations and intelligence collected by the settlement police on Chinese notables through 1945, including intelligence on prominent Green Gang bosses such as Du Yuesheng, Zhang Xiaolin, and Huang Jinrong. These materials are in English. Therefore I kept any names that appeared in them transcribed from the Chinese in the format in which they appeared, generally Green Pang (Green Gang) and Tu Yueh Sung (Du Yuesheng).

Besides these two archives, supplementary materials include articles related to the Green Gang found in major newspapers such as Shen Bao (Shanghai Daily) and memoirs published in the 1970s in Taiwan by former gang members. Checking the accuracy of these memoirs with American intelligence reports (via the Hoover Institute collection) revealed only minor discrepancies. This paper also critically reinterprets some materials that have been used in previous studies, including Qing Men Kao Yuan (literally, Exploring the Origin of the Family of Purity, 1933), Jindai Jiali Zhiwen Lu (lit. On Recent Events of the Family, 1935), An Qing Shi Jian (lit. History of An Qing, 1934), and An Qing Xitong Lu (lit. Lineage of the An Qing Family, 1935). Historians treat these writings produced by Green Gang members in the 1930s as authoritative primary materials (Cai Reference Cai1993: 344). This study excludes contemporary biographies because of their anecdotal quality.

Legitimating violence in Republican Shanghai

The Republican era (1911–49) in China saw a swift and chaotic transition from the old dynastic order in search of a new form of governance (Spence Reference Spence1991; Lary Reference Lary2007). Two revolutions were fomented during this time: The Revolution of 1911, which ended the 2,200-year-long dynastic system, and the Communist Revolution, which overthrew the nascent Republican government in 1949. The period was also characterized by warlordism and civil wars, constant regime changes, and competing ideologies. China experienced a fundamental transformation of its prevailing economic, political, and cultural life in this period. This was especially true in Shanghai where the longtime presence and influence of European colonial powers led the city to develop three systems of jurisdiction – the Chinese government, the French Concession, and the International Settlement – each with its own regulations. The extraterritoriality in Treaty Ports compromised Chinese sovereignty and created opportunities for grassroots extralegal groups to act as intermediary between concession police and local Chinese residents (Wakeman Reference Wakeman1995).

As social norms and values were shaken in the early twentieth century, Green Gang members drew from their long traditions and rearticulated the organization’s cultural scripts, especially the meanings of violence, adjusting to its structural transformations (Marshall Reference Marshall1976; Qin Reference Qin2009). The interactions between the gang’s structural changes and their cultural reframing efforts were revealed most saliently in its self-legitimation claims. These claims featured Green Gang’s use of violence as disciplinary, redistributive, and nationalistic, as detailed below.

Disciplinary violence and organizational changes

The first characteristic of Green Gang’s self-legitimation claims is that they framed their use of violence as disciplinary. This extended both to the use of violence to discipline internal members and its use to avoid unnecessary conflicts with external forces. Responding to the rapidly changing social environment and organizational composition, Green Gang’s disciplinary violence was gradually linked to members of the lower classes as a control mechanism, while refraining from arbitrary exhibition of violence externally to gain public tolerance.

To sustain secret societies in perilous environments, having formal rules and severe punishment was essential to maintain internal organizational order (Cai Reference Cai1998: 11). Such violence is a radical means of enforcing organizational rules by punishing non-conformers. For instance, the Ten Commandments (shi jie) in a Green Gang members’ brochure (1932) defined members’ acceptable behavior and stated explicitly that members could enforce them by beating violators to death. Such articulation of violent practices was also commonly found in martial arts groups and religious movements during the Ming-Qing dynasties (Lipman and Harrell Reference Lipman and Harrell1990; DuBois Reference DuBois2005). Organizational discipline could be essential for the survival of these groups especially when they revolt against authorities.

Besides written rules that justified violent punishments for the sake of group solidarity, oath-making rituals played “a vital role in legitimation processes” in Chinese popular culture generally (Katz Reference Katz2009: 63) and the Green Gang in particular. For sworn brotherhoods in particular, blood oath enhanced “a sense of group identity” (ibid.: 66). According to Qin Baoqi (Qin and Tan Reference Qin and Tan2002), initiation ceremony, of which “blood oath and crossing swords” was a central element, was the most important ritual in any banghui organization. More importantly, the detailed procedures and symbols used in banghui’s oath-making ceremonies show that legitimate violence was internally directed. During initiation ceremonies, a man would crawl under two crossing swords pointing downward above his head (Qin and Tan Reference Qin and Tan2002: 57–59). This ritual symbolized that the penalty for betraying the organization or its members, who became the man’s “family” after it was complete, was death by sword. Similar practices were also found in the practices of Taiwanese Triad in the late eighteenth century (Katz Reference Katz2009: 75).

Within the Green Gang, each master’s household became a center of authority to execute non-conformers. Violence within the household was private, and public authorities largely tolerated these executions. For instance, Huang Jinrong, the infamous Green Gang boss of the early twentieth century, tortured a disciple for his betrayal and called the action “cleaning the house” (qingli menhu) (Qin Reference Qin2013: 81). Often the “closed door” punishments were more severe than violence between rival groups (Chen Reference Chen1967). A guilty member might be temporarily protected by his household from an external rival but would be punished more brutally by his own master, because his behavior had direct impact on the reputation of the master’s house.Footnote 4

In other words, banghui gangs’ disciplinary violence was directed inward for the purpose of maintaining trust and loyalty among members who were not bonded by primary social ties such as kinship, native-place, or occupation. Lacking these social ties that were the foundations of other mainstream voluntary groups, banghui organizations depended on the spectacle of crude punishments to constrain individual behaviors.

Disciplinary violence directed externally had strict limits. The Ten Taboos (1932) strictly prohibited arbitrary violence against “innocent people,” and actions that might cause unnecessary conflicts with other territorial groups or disrupt the dominant Confucian moral order. Often, violent actions against outsiders were framed as self-defensive and protective. From their origin, banghui were mutual aid groups for individuals “marginalized by violence, mobility, and socioeconomic changes” (Ownby Reference Ownby1996: 6). Violence often occurred in response to violence (ibid. 15), such as the Qing government’s brutal execution of banghui leaders and of any members who carried weapons publicly, even if they made no use of them, to exhibit state power against all unsanctioned grassroots organizing (Qin 2002: 140; 141–42). Members, at least, saw violent response to such abuse as justified (Ownby Reference Ownby1996: 20–21).

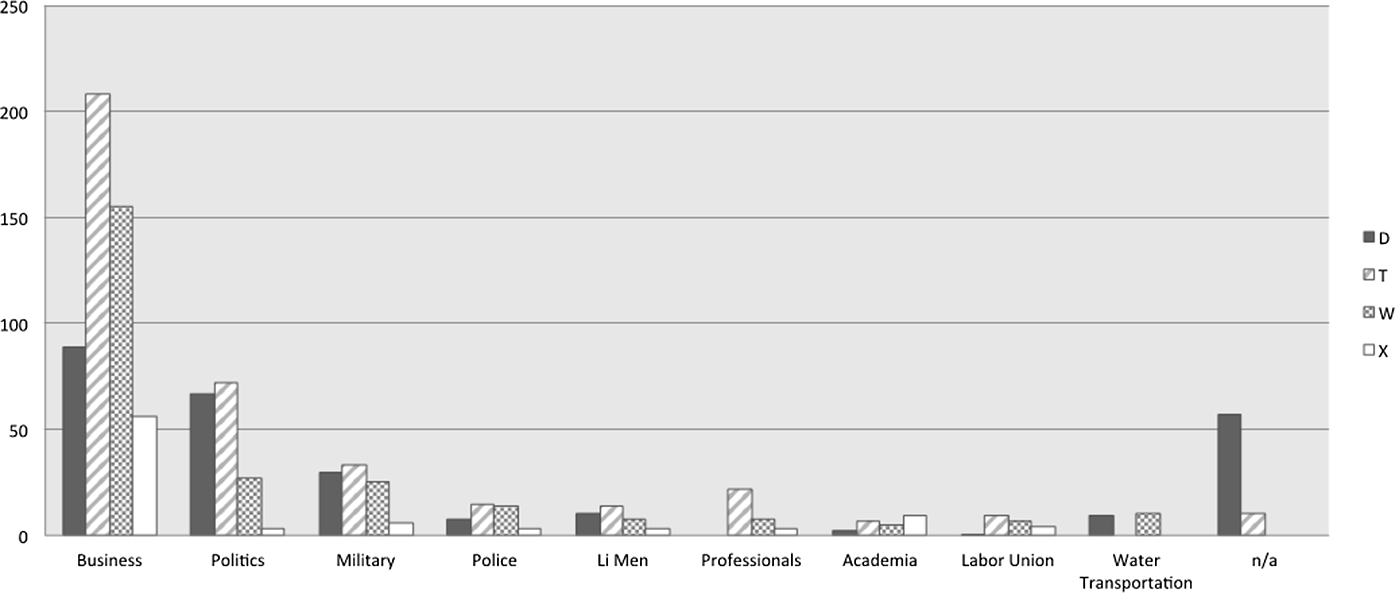

Even as the structure of disciplinary violence by the Shanghai Green Gang largely remained the same, the gang’s organizational structure and surrounding social environment changed drastically over the early decades of the twentieth century. In particular, the changing membership composition posed new challenges for the gang’s leadership. Figure 1 shows the diverse occupational backgrounds of Green Gang members,Footnote 5 including 1,057 persons who were formally acknowledged as active members with generational names and traceable fictive lineages. They were different from those self-proclaimed gang members who were never formally accepted by any master.Footnote 6 As shown in the graph, the occupational composition of gang’s membership shifted across generations. Many senior members did not belong to any modern category of occupation, and there were no professionals (e.g., doctors, lawyers, journalists) among them.Footnote 7 There was also, among the younger Tong generation (see fn.7), an increase in the number of members involved in business and a decrease in the number involved in politics. When the Green Gang loosened strict hierarchy by seniority post-1911, the generational title, or seniority, was no longer a mechanism regulating the organization, although members still used these titles to identify individuals.Footnote 8 For instance, the Ten Taboos (1932) explicitly prohibited a father and son from following the same master, because it would disturb the organization’s hierarchy to position a father and son in the same “generation.” In practice, however, it was common to see one disciple following several masters of different generations. In one well-documented case, former Shanghai mayor Wu Tiecheng had honored both a person of Da generation and of Tong generation as his Green Gang masters (Qin Reference Qin2011: 172).

Figure 1. Member’s occupation by generations.

Facing an increasingly diversified membership, the Green Gang leaders adopted a common way to incorporate members of different backgrounds and classes into their households. Disciples were separated into two groups: “mentu,” apprentices, were members of lower social backgrounds, who joined the organization through traditional rituals and strictly followed rules and principles and “mensheng,” students, were members from upper classes and new professions, who were introduced by local notables and not subject to private house rules (Qin Reference Qin2013: 191–93). Scholars argue that violence was an indispensable component of banghui organizations because of a bachelor subculture in which marginalized men of lower classes were prone to “use violent means to solve problems” (Qin Reference Qin2013: 81) or who had “rowdiness and readiness for violence” (Ownby Reference Ownby1996: 20–21). In the 1920s and 30s Green Gang, however, it was not that the lower classes were more accustomed to a violent culture, but that the use of force was intentionally restricted to this group of disciples who were separated from the more elite members (Chen Reference Chen1967: 81). The gang’s internal disciplinary violence was directed to members of the lower classes as a means of control.

In Huang Jinrong’s household, for example, the low-ranking runners had almost no chance to meet the master directly. They followed the master’s orders, sometimes required the use of force, and filed reports to him through mediators, who were typically the master’s trusted subordinates (Chen Reference Chen1967: 80). These mediators were also in charge of a variety of the master’s ventures. They handled accommodation for visitors from all over the country and from all social backgrounds. Masters usually worked with only a small circle of henchmen, and their activities included giving the final say in important decisions and participating in social events with other local notables (Chen Reference Chen1967: 81–82).

Externally, the gang continued to refrain from arbitrary and unnecessary demonstration of force to outsiders. Besides regulating members’ behavior within the organization, the disciplinary nature of violence was reflected in the relations between the Green Gang and other banghui organizations. Most of the time, different groups followed the principle of “no conflict, no cooperation.”Footnote 9 For instance, a member of the Green Gang recorded the prominent Green Gang boss Du Yuesheng’s first encounter with several Gelaohui leaders in Chongqing in his memoirFootnote 10 :

During this trip, Master Du was accompanied by Xiang Chunting, a Gelaohui leader and an old contact of his. He explained to Master Du that the Sichuan banghui rankings were very different from the Green Gang: “everyone here has people and guns; the more guns and more people they have, the more prestige they have in the local society.” Master Du was astonished by the fact and shocked to learn that one of the leaders was female.

Gelaohui (the Gowned Brothers) was the most powerful banghui organization in the southwest region and was considered a Sichuan version of the Green Gang with its high percentage of members among population and its deep embeddedness in local society and politics (Wang Reference Wang2018). When the two armed forces encountered each other, respecting one another’s gang codes became crucial to maintaining their harmonious coexistence:

Because of master Du’s great reputation as a pillar of society, he was warmly welcomed by various banghui leaders. They respected each other, but somehow remained as distant as possible. Master Du had no clue of other groups’ rules and norms, and thus he refused to take gifts from them. He said that it would “give them trouble.” (Wan, Reference Wan1977: 175)

As an exemplar of the rationalist perspective, Martin (Reference Martin1996) argues that Shanghai Green Gang in the twentieth century was a new type of organization, more formal and entrepreneurial, emerging in modernization processes, only loosely related to the traditional banghui forms. Although the culturalist approach generally emphasizes the persistence of traditions, Qin (Reference Qin2011: 77) also describes banghui’s structural changes in the Republican period as “evolving into a black society.” As he explains, black societies had more formal structures, more members, more stable leadership, and greater discipline than banghui organizations (Qin Reference Qin2013: 2–3). However, Qin overestimates the extent to which organizational discipline had increased. Discipline was always a critical feature of Green Gang’s framing of its violent culture, and discipline through violence was a critical feature of Gelaohui as well. The latter had committed public lynchings of members who had been disobedient and such public exhibition of violence was largely tolerated by the state and society (Wang Reference Wang2018). While criminal law promulgated by the Republican government ostensibly banned such violence, it continued. As Wang (Reference Wang2018) argues, disciplinary violence showcased banghui organizations’ tyrannical power and was perceived in local society as the legitimate public exhibition of banghui master’s authority and reputation, even if it meant people killing members of their own families.

In sum, the Green Gang articulated its use of violence as directed internally only towards non-conforming members and externally only towards hostile forces. Internal violence strengthened fictive kinship ties and maintained the reputation of gang master’s households. With the increase of elite members in the early twentieth century, the gang deliberately confined its violent culture within members of the lower classes. Externally, the gang strictly refrained from arbitrary use of force and depicted itself as protective and defensive. Such an image gave Green Gang a certain level of public legitimation such that the state and its competitors tolerated it as long as it is targeted and controlled.

Redistributive violence and guardian of nationalistic tradition

In addition to emphasizing the disciplinary nature of its use of force, the second feature of the Green Gang’s self-legitimation claims was its appropriation of the rhetoric of revolution and social justice. Members attempted to bond gang figures with the image of “xia” as protectors of urban poor and revolutionaries defending the Chinese nation. This self-legitimation effort, however, contained unresolvable cultural contradictions.

Situating the writings by Green Gang members during this time in a larger cultural context, I find that the gang showed a strong affinity to the re-emerging culture of “xia” – the knight-errant culture the rising book publishing industry inflated at the turn of the twentieth century. Members frequently used the language of “knight-errant,” accompanying the “martial art craze” in the late 1920s and early 1930s.Footnote 11 Members reframed their image of the marginalized outlaw through the figure of knight-errant, who realizes social justice through deployment of violence.

Extralegal organizations of many cultures have used the claim that gangs stood up for the weak against repression to legitimate practices of violence (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1996; Hill Reference Hill2003; Siniawer Reference Siniawer2011). This claim was prevalent and powerful in legitimating violence from below – on the one hand, it generated ambiguous legitimate status for certain “violence specialists” who were historically embedded in local impoverished communities providing protection; on the other hand, it often allowed competing authorities to legitimize their own actions of co-opting these armed forces to penetrate local society (Siniawer Reference Siniawer2011: 21). Famous Green Gang leaders were portrayed in public as protectors of urban poor neighborhoods and their participation in disaster and war relief was publicized to boost the gang’s public image.Footnote 12 The gang also recruited key figures in philanthropic organizations. For example Chinese Red Cross Secretary Guo Lanxin was a close Green Gang affiliate.Footnote 13

More importantly, Green Gang leaders were not simply acting as protectors and benevolent philanthropists for their communities, but they embraced the spirit of “xia,” meaning they identified as figures who achieved social justice through violence in a stateless environment. For example, a widely circulated Who’s Who of Chinese celebrities in the 1930s described gang masters Huang Jinrong and Du Yuesheng as “allegiant and gallant as knight-errants.”Footnote 14 In Chen Guoping’s recount of Green Gang history (1932), he also called a senior master “haoxia” (the great knight-errant) because he offered protection for his community against warlords. Sectarian groups and secret societies historically engaged in martial arts training, and it was an indispensable feature of “xia” (Lipman and Harrell Reference Lipman and Harrell1990). Members’ writings in the early twentieth century show intentional cultural work to depict their leaders as “xia” and framing of their biographies along the line of knight-errant adventures.

The central component in knight-errant culture was “a code of ethics centering on requiting favors and righting injustice, through the means of physical act” (Eisenman Reference Eisenman2016: 25). Zhang Binren, a contributor to Qing Men Kao Yuan, argued that the public confused the Green Gang and the Triads with gangs (bang), secret societies (hui), or even bandits (fei); “however, they did not know that the true principle of our organization was the cultivation of ethics and virtue (daoyi)” (Chen Reference Chen1932: 61). Former gang member Ren Nai also indicated that he intended to reclaim the gang’s history, rescuing its “authentic” principles from the widespread mistaken idea that it was iniquitous and backward. Supplementing his strong emphasis on Buddhist doctrines, Ren illuminated the relation between the literati (ru) and xia, both of which valued strong adherence to “the Way” of a moral society:

The literati (ru) usually criticized the knight-errant (xia) for his rebellious and heretical spirit that disrupted order and harmony. In fact, the reason for Xia’s rebellion was to restore “the Way” to a decadent society, to bring order out of chaos. The deviant behavior was framed as non-conforming and rebellious to the old order that lost the Way (Chen Reference Chen1932).

One reason that the spirit of knight-errantry regained traction at the dawn of the twentieth century was that revolutionaries redefined and promoted it to articulate the relationship between outlaws, state, and nation to advance their political agenda. Liang Qichao, the prominent reformist and scholar who lived during the late Qing and early republic, maintains that the Chinese spirit of “xia” entails a set of nationalistic and altruistic ideas:

The nation weighs more than life, friends more than life, responsibility more than life, promises more than life, gratitude and revenge more than life, honor more than life, and the Way more than life. (Liang Reference Liang1901)

Revolutionaries of 1911, many of whom were banghui members, found the image of knight-errant in historical documents an ideal model. They sought to practice his disregard of social norms to achieve public welfare in chaotic times. By making connections to xia, they conceived a model of “nonstatist political responsibility” when facing foreign imperialism (Liu Reference Liu2011: 3). This spirit spilled over to banghui organizations participating in the revolution, shifting “the arbiter of justice from the state to xia” (ibid.: 6), and accordingly justified its use of violence. In their writings, Green Gang members strived to highlight their organizational roots in the Nationalist Revolution and the “xia” stories of members (Chen Reference Chen1932). The story of Li Zhengwu, the leader of the Jiangnan revolutionary army, served in this capacity. Born in Shanghai to a rich family, Li poured his private family fortune into organizing local Green Gang forces in support of the 1911 Revolution and used his status in the Ningbo native-place association to mobilize resources (Shao Reference Shao2013: 75).

The Nationalist Revolution was not limited to the reconstruction of the Green Gang’s past as “revolutionary.” By making a strong assertion of the gang’s contribution in the Taiping Rebellion, in the Boxer Uprising, and in the Revolution of 1911 (all insurrections against Qing rule), members claimed that the Green Gang had made critical contributions to the founding legacy of the new republic representing the Chinese nation, echoing their claim for social justice through the knight-errant spirit which put the Chinese nation at its core (Chen Reference Chen1932). Chen Guoping even claims that the spread of founding father Sun Yat-sen’s idea of nationalist revolution benefited from “the seeds” banghui had scattered through their anti-Manchu insurgencies (ibid.: 66).

Another reason for the cultural hype of “xia” in the early twentieth was the new booming modern publishing industry that pumped out thousands of popular fictions. The key link that the Green Gang drew with “xia” was with “rivers and lakes,” an autonomous space free from state intervention that was created in the literary imagination of martial art fictions. In the first half of the twentieth century, martial arts fiction was the most popular literary genre and sold the most copies (Chen Reference Chen2010: 53–54). Against this cultural context, Chen Guoping’s writings frequently referred to the contested site of banghui activities as “rivers and lakes.” He stated that this popular literary construction was borrowed from the Green Gang slang because the gang originated as a group of boatmen on a river transportation route in the early Qing dynasty (Chen Reference Chen1932: 220). This connection was important because the discourse of “rivers and lakes” defines “a public sphere unconnected to the sovereign power of the state, a sphere that is historically related to the idea of ‘minjian’ (between the people) as opposed to the concept of ‘tianxia’ (all under heaven) in Chinese philosophy” (Liu Reference Liu2011: 6). In his writings, Chen echoed the emphasis on mutual responsibility and dependence of banghui members, downplaying state control and regulation. He justified the morally ambiguous banghui activities thus:

One day we jump over the dragon gate and the next day we crawl through dog holes. We do good things and terrible things. Benefits always accompanied sacrifices. As long as it is good for our group, we do it without hesitation. (Chen Reference Chen1932: 281)

The imagined sphere of “rivers and lakes” tolerated people from all social backgrounds and operated with its own code of ethics, outside the scrutiny of state sovereignty, and thus it furthered the self-legitimation discourses of the Green Gang. Through such references members articulated that the gang’s rules and norms were local rather than global.

Intellectuals of various periods, non-members, also referenced the cultural connection between the Green Gang and “xia.” For instance, Liang Shumin stated that banghui members had an imagined community like “rivers and lakes” that were built on voluntary association, differing from most of the common Chinese people of their times, who imagined society around the idea of family (Liu Reference Liu2002: 244). Leftist Mao Dun and liberal scholar Hu Shi both linked banghui to knights-errant, noting the tendency to “promote private violence,” although both described the connection in negative terms (Liu Reference Liu2011: 32). Contemporary historian Qin Baoqi titled one of his monographs about Chinese banghui Rivers and Lakes in Three Hundred Years, noting that the banghui world accommodated various “non-mainstream social groups” (Qin Reference Qin2013: 3).

The Green Gang’s self-legitimization through the rhetoric of revolution and “xia” during the early Republican period was, however, inherently contradictory. On the one hand, the gang promoted an image of a powerful insurgency representing the urban poor against various abusive oppressors; on the other hand, it aspired to restore traditional hierarchies and norms that the revolutions they intended to link to had destroyed. Having tried to co-opt banghui to its movement since the beginning, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) soon realized that banghui were “united in a common and inherited hatred for whatever dynasty, warlord, or party in power in their district. They are a natural corollary to the right of revolt which runs through the moral code of Confucius.”Footnote 15

In sum, the Green Gang of the twentieth century depicted its leaders as knights-errant protecting impoverished labor and celebrated the gang’s historical role in revolutions defending the Chinese nation. By making a strong connection to the xia culture, the gang achieved a public role in an imagined stateless sphere, where it had a unique code of ethics that suggested violence would reset social order and achieve social justice.

Violence for the Nation vs. Violence for the state

The above discussed features of Green Gang’s self-legitimation efforts – violence as disciplinary, redistributive, and guarding tradition – resonated with the ultra-nationalistic wing of the republican political world. This ideological affinity facilitated the interactions between gang members and GMD rightists. However, the two groups were also distinguished fundamentally in their understanding of violence in relation to the state. The Japanese military occupation of Shanghai exposed the cultural contradictions contained in Green Gang’s self-legitimation claims, and eventually led to the gang’s fragmentation.

During the Northern Expedition against the rule of warlords in 1924, GMD members of a secret organization in Shanghai requested the protection of gang master Du Yuesheng.Footnote 16 After that the Shanghai Green Gang established friendly relations with important veteran Nationalist leaders including Chiang Kai-shek. Their collusion in opium traffic has been well studied (Marshall Reference Marshall1976; Martin Reference Martin1995, Reference Martin1996; Slack Reference Slack2001); less well discussed were the tight organizational ties between the Green Gang and the Blue Shirt Society, an organization embodying a variant of fascist thinking that was spreading in the GMD and its military (Eastman Reference Eastman1972; Chang Reference Chang1985; Gregor Reference Gregor2018). The affinity between the two organizations reveals a parallel development of how high politics of violence were reflected and received in lower social groups and how extralegal forces shaped the course of high politics in return.

Besides the well-known fact that Blue Shirts and the Green Gang were two executioners at the forefront of the 1920s anti-Communist campaign, the two groups were connected through personnel and finances.Footnote 17 On the surface, the society and the gang were two extremes – the former comprised elitist militarists within the GMD, while the later were outlaws of the lower strata of society. In reality, the two groups overlapped in their composition. According to SMPA documents, Blue Shirt Society members were “mostly graduates of the Whampoa Military Academy and the members of the Green Pang.”Footnote 18 The Green Gang also had its own elite faction called the Endurance Club, which recruited professionals of all fields, including Nationalist army leaders.Footnote 19 Financially, both groups depended on the opium business. For example, Chiang Kai-shek authorized the Green Gang to establish a morphia refinement factory and converted the confiscated drugs during the opium suppression movement for medical use. The resulting profits were used to support the Blue Shirt Society.Footnote 20

But it was ideological affinities that fostered the alliance between the Green Gang and the Blue Shirt Society, representing the “violent nexus of revolutionary and counterrevolutionary politics” (Clinton Reference Clinton2017: 4). Both the gang and the society possessed a violent hatred of Communism. Building upon the foundation of Confucian patriarchy that emphasized classed and gendered social order, the Green Gang self-legitimized as a force of revolution of the whole Chinese nation, rather than any specific class. A similar ideology dominated the Blue Shirt Society. Controlling the GMD military in the 1930s, the Blue Shirt Society created “enduring legacies of their efforts to link Confucianism to an anti-liberal, anti-Communist program of state-led industrial development” (ibid.). Rather than the class struggle propagated by the Communists, the Blue Shirt Society and the Green Gang envisioned an ideal world characterized by “natural” social hierarchies and class harmony under the banner of the Chinese nation (ibid.: 3).

The languages the Blue Shirt Society employed to justify their use of violence were almost identical to that of the Green Gang, showing common elements in regulating the organization’s internal order by many social groups of the period. Members of the Blue Shirt Society “must be ready to sacrifice their freedom, their rights, and even their lives for the sake of the principles of the Society.”Footnote 21 Just as the bond of master and disciple in the Green Gang was perpetual, the Blue Shirt Society’s members were “not allowed to resign from the society” (ibid.) Albeit from different perspectives, the gang and the society saw violent oppression against those who dissented as not ideal but nonetheless necessary to achieve collective goals (Eastman Reference Eastman1972). For the Blue Shirt Society, this goal was to build national strength for unity and discipline. Therefore violence would be directed against “all persons who contributed to the moral and cultural decline” of society (ibid.: 9); for the Green Gang, the goal was to protect the old Way by reinforcing and expanding the power of its organization.

Many gang members found the anti-traditional values the communists had proposed appalling.Footnote 22 Banghui members of high and low ranks alike welcomed the GMD’s anti-Communist calls for the return to familiar moral doctrines and hierarchies. Despite the CCP’s repeated efforts to recruit from the top down and mobilize from the bottom up, the Green Gang showed a strong hatred of the party and its ideology, and it violently suppressed communists’ activities within its territory without hesitation. In April 1927, three Green Gang leaders assembled two thousand followers, who assisted with the GMD’s purge of communists in Shanghai’s labor organizations.Footnote 23 The GMD had planned the city-wide slaughter of communists, but the French Concession and the International Settlement, which had deeply involved the Green Gang in the local governance, had acquiesced to it. In Marshall’s (Reference Marshall1976) words, the Green Gang “broke the back of the communist strategy of winning the cities.”

However, the ultra-nationalistic rhetoric of the two groups also differed significantly in their understanding of state authority. The Blue Shirts endeavored to subject everything under a centralized state, whereas the Green Gang strove for a decentralized authority so that they had room to run illicit businesses (Eastman Reference Eastman1972). The society allowed only one paramount leader, whereas banghui members pledged loyalty to one master, but several masters could coexist as long as they honored the doctrines. In this sense, the alliances between the Green Gang and the GMD rightists were unstable in the long run and were sometimes opportunistic rather than committed. Low-ranking gang members, many of whom were shantytown dwellers in Shanghai, used the language of nationalism as a strategy to demand their inclusion (Chen Reference Chen2012: 127). Sometimes, the GMD enticed gang members in poverty to join the Blue Shirt Society with monetary incentives: “The Society will distribute grants from twenty to thirty yuan among members who are in the list of unemployed.”Footnote 24 In return, the gang turned a blind eye to the Blue Shirt Society’s abductions in the French Concession, though they had always received political protection from the French Concession authorities and had plenty of eyes and ears with which to monitor these activities.Footnote 25

The national crisis triggered by the Japanese assault on Shanghai had strongly challenged the Green Gang’s self-legitimized rhetoric of nationalistic violence, and subsequently severed the gang. Although the gang had long worked with foreign authorities in settlements, it was unable to work with the Japanese occupiers. The fall of Manchuria in 1931 and temporary occupation of Shanghai in 1932 created a surge of Chinese patriotism and mobilized the public to an unprecedented degree. The gang’s development during the Japanese occupation exposed its inherent cultural contradictions.

When the war broke out, both the GMD government and the Japanese army endeavored to subjugate the Green Gang to negate its power over urban labor and sojourner communities. This created inner strife among the gang’s top leaders because of their divergent altitudes towards the Japanese, which led to brutal conflicts between and within the gang branches. Some branches of the gang, especially those under the leadership of Du, formed guerrilla troops to facilitate the Nationalist government’s intelligence activities. They were particularly recognized for carrying out assassinations of Chinese collaborators.Footnote 26 These branches tightened their control over the motor car, bus, and tramcar drivers to prevent them from working for the Japanese.Footnote 27 However, Du’s sworn brothers, including Huang Jinrong and Zhang Xiaolin, had shown sympathy for Japan. Zhang ultimately collaborated with the Japanese and then turned his gang forces over to them (Wan Reference Wan1977: 109). Evidence also suggests Green Gang members, most of them once followers of Du, facilitated addition, the surrender of Chongming Island of Shanghai. SMPA recorded that the Green Gang had been paid off: “The Japanese army has resorted to the time-honored practice in China to fight with ‘silver bullets’ and has paid $500,000 for the bloodless surrender of the Chinese defenders on the island.”Footnote 28

The split and exile of several top leaders led to intense fighting over the control of the gang’s remaining forces in Shanghai. In addition to violent clashes between pro-Japanese and anti-Japanese camps, conflicts emerged within the resistance force. Assassinations were not always directed toward pro-Japanese individuals; rather, the use of violence became a statement of power within the remaining gang organizations. For instance, followers of Loh Lien-kwei, a superintendent with the Shanghai municipal police and an anti-Japanese leader of the Green Gang who stayed in the International Settlement after the occupation, assassinated him, probably at the impetus of Du himself, although Loh had once been a follower of Du.Footnote 29 After Du had left the mainland for Hong Kong, Loh began gradually expanding his influence, displaying contempt for Du, both of which probably factored into Du’s action against him.Footnote 30 Similar incidents included the death of a secretary of the Shanghai Women’s Club; the police believed Du Yuesheng’s wife was involved.Footnote 31

The arbitrary use of violence during this period challenged the hierarchical, disciplinary nature of the gang’s self-legitimation claims, and discontent spread among members. For this reason, thirteen important Green Gang leaders had secretly come to Shanghai from Hong Kong to reorganize the gang and organize their own national salvation movement.Footnote 32 Their activities included prevention of anti-Japanese terrorist attacks, refugee relief, and removing “undesirable persons” in the Japanese and the British settlements. However, attempts to organize new societies to assimilate former gang members were mostly unsuccessful.Footnote 33

During the Japanese occupation, most low-ranking members had been assimilated into various armed units in Shanghai. These include Shanghai city government police and reserves, Japanese gendarmerie, and available reserves (Japanese soldiers, Chinese police, self-defense corps, and plainclothes groups).Footnote 34 The most notorious among the armed units was “the Nationalist Army for Purging the CCP and Saving the Nation,” a plainclothes group controlled by Wang Jingwei for the Japanese puppet government, which aimed at eliminating Communist and anti-Japanese elements in the city. Their violent activities included shootings, murder, bombings, kidnapping, extortion, and collecting intelligence for the Japanese authorities. The group’s size was estimated at about 1,000 men, the majority of whom were recruited from the remaining gang forces. This recruitment was not always voluntary. The principal of a secret pro-Japanese organization had threatened the remaining Green Gang members to support Wang Jingwei’s polity by stating that any opposition “would result in serious consequences.”Footnote 35 Meanwhile, the Japanese military was press-ganging from rural areas around Shanghai for service in Qingdao. Among the forced labor were former banghui members who had become unemployed after major Green Gang bosses left the city.Footnote 36

In a speech after the Resistance War against Japan, Du told his remaining gang members and new recruits that the most pleasing thing for him was that “the name of our group remains pure.”Footnote 37 However this was wishful thinking. The gang had been scattered, and the Nationalist government, Japanese military, and local scoundrels were all attempting to control it for their own benefit. From the perspective of foreign authorities, both anti-Japanese and pro-Japanese violence were terrorist attacks if “they disturbed peace and order” in the Concessions.Footnote 38

Conclusion and discussion

Examining the self-legitimation claims of the Green Gang, this paper provides a synthesized view that combines the rationalist and culturalist perspectives to explain the rapid growth of the extralegal group and its unprecedented tolerance by the state and the public during the early twentieth century. In addition to the influence of a rampant opium market and a weak state that provided opportunities for the gang to thrive, the gang’s cultural work to self-legitimize its use of violence shaped its relationship with various regimes and with the larger society in early twentieth-century Shanghai.

The gang’s self-legitimation claims focus on articulating its use of violence as disciplinary, redistributive, and nationalistic. First, members’ writings suggest that the gang’s use of violence always aimed to discipline non-conformers within the organization and it strictly restricted arbitrary violence against external forces unless for defensive purposes. Responding to the changing membership composition in the early twentieth century, the gang continued to emphasize the disciplinary nature of its violence while confining the violent culture to members of the lower classes. Second, the gang highlighted its connection to the knight-errant spirit to striving for social justice for marginalized urban laborers and described it as rooted in the revolutions for national survival and for protection of the Chinese tradition against centuries-long internal and external threats. Third, the gang’s self-legitimation claims showed strong affinity to the ultranationalist wing of GMD, the Blue Shirt Society, with which it also shared organizational and financial ties. The nationalism and anti-communism that the gang exhibited was however different from the Blue Shirts in its pursuit of a decentralized authority to run illicit businesses.

As the rationalist perspective proposes, violence was crucial for an extralegal organization, both as a commodity itself and as a means to facilitate market competition for illegal products. The culturalist perspective complements this view by explaining what made extralegal violence open to exchange, sale, and co-opting. The Shanghai Green Gang’s framing of violence as disciplinary, embracing xia culture, and protecting the Chinese nation was what they perceived as the cultural expectations accepted by the mainstream society at the time. Countering the Chinese orthodox culture that condemned violence, the cultural work of gang members conveys positive normative messages about “the desirability and use of violent behavior…and prescribed certain real situations in which resort to violence was the only moral alternative” (Lipman and Harrell Reference Lipman and Harrell1990: 9). The cultural elements such as discipline, knight-errant spirit, and nationalism that Green Gang members picked up to describe their experiences echoed the powerful ideologies, which made coalition, collusion with, and tolerance by other political actors possible.

It would be an exaggeration to suggest that the Green Gang had a coherent system of thought, and there were many inherent contradictions contained in its self-legitimation claims, such as portraying itself simultaneously as a protector of traditional values and as a revolutionary force that destroyed such traditions, or anarchic heroism embraced in xia culture and nationalistic ideals promoted by the Blue Shirts. But the members’ cultural articulation should also not be understood as solely a signal of instrumental or material considerations as the rationalist perspective would suggest. The Green Gang members constantly endeavored to adjust their traditional values and norms to embrace new cultural trends in response to a rapidly changing society in the early twentieth-century urban Shanghai. To some extent, the Green Gang mediated between political-military elites and the masses around economic and ideological cleavages of the time. The malleability of its claim to violence reflects the ideological struggles on the ground, which were different from elite militants and intellectuals expressed. Eventually, the powerful external threat posed by imperial Japan easily exposed the cultural contradictions in the gang’s self-legitimation reframing, and the organization crumbled.

From the rationalist perspective, state and extralegal groups are ultimately enemies in the competition to provide protection. Extralegal groups flourish when weak or emerging states do not have the resources to protect their citizens. From the culturalist perspective, regimes tolerated – or at least turned a blind eye to – extralegal violence to the extent that the violence took place within existing social and cultural frameworks. The self-legitimation work of the Shanghai Green Gang brings the two perspectives together: it shows how gang members perceived and tinkered with cultural scripts of their past and present regarding violence and how they positioned themselves accordingly in competition or collusion with other forces. Their cultural work reflected not only the internal dynamics of banghui organization but also features of the Chinese state and society in general.

The significance of cultural work regarding violence is not unique to the Green Gang. Extralegal groups around the world engage in various types of cultural work to self-legitimize and challenge states’ definition of the nature of certain type of violence. For instance, yakuza groups in Japan proactively performed cultural work to create “ambiguous status and varied perceptions [that] would help them and their political violence endure” (Siniawer Reference Siniawer2011: 39). Familial loyalty and instrumental friendship – trust-based relationships that beget the fulfillment of reciprocal obligations – are eagerly promoted by mafia in Sicilian society (Catanzaro Reference Catanzaro1985). Despite their brutal and corrupting nature, American’s criminal syndicates also cultivate their iconic image as men of honor and tradition through rituals and myths in order to ensure the organizations’ continuity and public justification (Nicaso and Danesi Reference Nicaso and Danesi2013). Large-scale crime organizations, in particular, tend to be more disciplined and secretive in their use of violence, which is “orchestrated by deception and betrayal so as to be highly accurate at close range” (Collins Reference Collins2011: 26). Thinking through these cases alongside the history of the Shanghai Green Gang reveals the multiple mechanisms including state building, resource extraction, and cultural legitimation that act jointly to explain the rise and fall of extralegal organizations.