Introduction

Substance use among military veterans in the United States is a significant public health concern, with these individuals showing higher rates of substance use disorders than the general public. Approximately 11% of veterans who seek help through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) qualify for a substance use disorder diagnosis, notably above the roughly 7–8% observed in the general adult population (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Fletcher, Frost, Harris, Washington and Hoggatt2022). This is likely due to experiences such as combat stress, trauma, and the shift back to civilian routines (Teeters et al., Reference Teeters, Lancaster, Brown and Back2017). Such transitions to civilian life can involve multiple stressors, ranging from difficulty finding employment to reduced social support that may exacerbate substance use (Sayer et al., Reference Sayer, Carlson and Frazier2014). Alcohol consumption is particularly a problematic issue, with 65% of veterans starting treatment for alcohol as their main struggle, a rate almost twice that of people outside the military (Golub et al., Reference Golub, Vazan, Bennett and Liberty2013). In addition, leaving the armed forces often intensifies substance use habits, with studies noting more marijuana and illicit drug use after discharge, while alcohol and prescription drug misuse remain consistently used (Derefinko et al., Reference Derefinko, Hallsell, Isaacs, Salgado Garcia, Colvin, Bursac, McDevitt-Murphy, Murphy, Little, Talcott and Klesges2018).

Recent VHA and national analyses show that sexual-minority veterans shoulder a disproportionate behavioral-health burden. LGB veterans have higher alcohol-attributable mortality and years of potential life lost than non-LGB veterans, pointing to both acute and chronic alcohol-related harms (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Gatsby, Shipherd and Lynch2023). A multi-state assessment likewise documents poorer outcomes across multiple domains for LGBTQ+ veterans relative to heterosexual/cisgender peers, including worse mental health and higher smoking (Schuler et al., Reference Schuler, Dunbar, Roth and Breslau2024). Within VHA care, sexual-minority veterans report less positive patient-centred experiences (e.g., feeling listened to/respected), and in a recent national VHA primary-care sample, they also endorsed greater needs for support with discrimination and housing – two minority-stress–linked social needs (Lamba et al., Reference Lamba, Jones, Grozdanic and Moy2024; Lamba et al., Reference Lamba, Frank, McCoy, Purkayastha, Leder, Russell, Gordon, Procario, Moy and Hausmann2025). VHA policy now mandates affirming environments and maintains LGBTQ+ Veteran Care Coordinators (VCCs) at every facility to improve linkage and navigation (VHA Directive 1340, 2002). Engagement, however, remains heterogeneous.

This study is situated in a biosocial/biocultural perspective, which treats substance use as emerging from the interplay between bodies and social worlds – i.e., how structural conditions (e.g., stigma, discrimination, economic insecurity, and service-related trauma) become embodied via stress biology, coping behaviours, and care access (Harris and McDade, Reference Harris and McDade2018). This lens complements minority-stress theory by specifying pathways through which social adversity shapes depression and substance-use risk among sexual-minority veterans (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003; Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009). Within this framework, bisexual individuals may encounter distinct biographical stressors (e.g., biphobia, erasure within multiple communities) that shape exposures, coping repertoires, and treatment engagement differently than for gay/lesbian peers (Feinstein and Dyar, Reference Feinstein and Dyar2017). Therefore, a biosocial/biocultural lens was paired with a minority-stress account to interpret subgroup differences and potential buffering by depression-related contact (DRC) and medication use.

In population surveys such as NSDUH, depression-related clinical engagement is captured coarsely as any past-year visit or conversation with a health professional about depressive feelings (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2023). Because these items do not capture psychotherapy modality, dose, frequency, duration, or provider discipline, the measure was conceptualized as DRC, a pragmatic marker of clinical engagement, not a psychotherapy indicator. Such contact plausibly intersects with substance-use risk pathways by prompting diagnostic assessment and safety planning; providing brief counselling or psychoeducation; triggering referrals to evidence-based care (including psychotherapy or medications); and facilitating linkage to social or peer supports. For sexual-minority veterans in particular, a single affirming clinical touchpoint may also confer identity validation and reduce stigma-related distress, mechanisms central to minority-stress models (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Berke, Ruben, Matza and Shipherd2019; APA Task Force on Psychological Practice with Sexual Minority Persons, 2021; Hilgeman et al., Reference Hilgeman, Cramer, Kaniuka, Robertson, Bishop, Wilson, Sperry and Lange2024).

Little work has assessed whether DRC is differentially associated with substance use among sexual-minority veterans with depression. Minority-stress processes can shape both the likelihood and the content of clinical encounters (e.g., disclosure comfort, provider responsiveness, identity affirmation). Accordingly, even low-intensity contact could buffer risk if it is affirming and leads to continued care, whereas non-affirming encounters could yield associations consistent with confounding by indication. The aim, therefore, is not to evaluate the efficacy of CBT, MI, or any standardized “talk therapy,” but to test whether this broader marker of contact – and, separately, past-year use of prescription medication for depressive feelings – is associated with attenuation of sexual-identity disparities among veterans experiencing a past-year major depressive episode (MDE).

Consequently, two questions were examined using nationally representative NSDUH data: (1) the extent of sexual-identity disparities in substance use and mental health among U.S. veterans; and (2) among veterans with a past-year MDE, whether past-year DRC (any visit or conversation with a health professional about depressive feelings) and past-year use of prescription medication for depressive feelings are associated with lower risk of substance use. The efficacy of specific psychotherapies (e.g., CBT/MI) was not evaluated; instead, these broader markers of clinical engagement were analysed to determine whether they moderate sexual-identity disparities, as available in a large, national dataset.

Methods

Study design and participants

Pooled data were analysed from the 2021–2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), focusing exclusively on respondents who reported having served in the U.S. Armed Forces (hereafter “veterans”) (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2023). After applying necessary exclusions and recodes (removing respondents with uncertain identity or missing design variables), the analytic sample constituted a weighted representation of veteran participants from the broader dataset. Survey weights, primary sampling units, and strata variables from the parent study were preserved to yield nationally representative estimates for the U.S. veteran population. All analyses were conducted in R using the survey package to account for the complex survey design (R Core Team, 2023; Lumley, 2024).

This study analysed the de-identified, publicly available NSDUH Public Use Files (PUFs) from 2021–2023; PUFs exclude direct identifiers and coarsen selected variables. Consistent with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR 46), this secondary analysis of de-identified public-use data was deemed exempt from additional institutional review board review.

Outcome variables

Two domains of outcomes were analysed: mental health and substance use.

For mental health-related variables, last-year MDE was defined as a binary NSDUH indicator (0 = no MDE, 1 = MDE) derived from the survey’s standardized depression module. Severe psychological distress (SPD) was defined using the Kessler-6 (K6) scale; per NSDUH convention, respondents with a K6 score ≥13 in the past 30 days were coded SPD = 1 (serious distress) and those with scores <13 were coded SPD = 0. DRC was defined as a binary NSDUH indicator (1 = any past-year visit or conversation with a health professional about depressive feelings; 0 = none). The item captures occurrence only; NSDUH does not standardize or record psychotherapy modality, number of sessions, duration, frequency, provider discipline, or fidelity. Therefore, this was treated as a marker of depression-related clinical engagement.

Prescription medication use for depressive feelings was defined as a binary indicator (1 = respondent reported any past-year use of prescription medication for depressive feelings; 0 = no). NSDUH does not capture specific drug, dose, duration, or adherence. Suicidal ideation was measured with the NSDUH adult mental health item, “At any time in the past 12 months, did you seriously think about trying to kill yourself?” Respondents answering “Yes” were coded 1 and those answering “No” were coded 0; “Don’t know/Refused” were treated as missing.

For substance use variables, nicotine use and marijuana use were defined as binary indicators where 1 = any tobacco/nicotine product use in the past 30 days; 0 = none. Binge drinking was also a binary indicator where 1 = any past-month binge episode per NSDUH’s definition; 0 = none. Prescription drug misuse was defined as a separate indicator for misuse of pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and/or sedatives. Because treatment/MDE reflect past-year status while substance outcomes are past-30-day, temporal ordering cannot be inferred.

For polysubstance use, past-30-day indicators were summed across nicotine, marijuana, binge drinking, and the four prescription-misuse classes. A three-level variable was then created: No use (0 classes), Single-substance (1 class), and Polysubstance (≥2 classes). For logistic models, a binary version was utilized: polysubstance = 1 versus no/single = 0.

Exposure variables

The primary exposure was sexual identity (Heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual).

Covariates

Covariates were selected for theoretical and empirical relevance to substance use and mental health. These included survey year, age category (18–25, 26–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65+), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic Native American, Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander [NH/OPI], Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic multiple races, Hispanic), sex (Male, female), education (Less than high school, high school graduate, some college/associate, college graduate), metropolitan status (Large metro, small metro, nonmetro), insurance status (Insured, not insured), marital status (Married, widowed, divorced/separated, never married), employment status (Full-time, part-time, unemployed, other/NILF), and annual household income (< $20 000 vs ≥ $20 000).

Statistical and missing data analysis

All analyses were restricted to the subsample of veterans who provided a valid sexual identity response, resulting in a primary analytic sample of N = 7,212 (unweighted). This sample was composed of heterosexual (n = 6,782), bisexual (n = 275), and gay/lesbian (n = 155) veterans. It is important to note that the smaller sample sizes for the sexual minority veterans, particularly for gay/lesbian veterans, can lead to wider confidence intervals (i.e., reduced precision) and may limit the statistical power to detect smaller effects. Within this sample, preliminary analysis revealed missing data across several outcomes (e.g., substance use) and covariates (e.g., income, treatment receipt).

To address potential bias and loss of statistical power from complete-case analysis, multiple imputation was utilized by chained equations (MICE), implemented with the mice R package (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011). Imputed datasets (m = 20) were generated with a reproducible seed (set.seed(123)). The imputation model included all outcome variables, predictor variables (sexident, talk_doc, used_meds), and all covariates listed above. This ensures the relationships between all analysis variables are preserved during imputation. Predictive mean matching (pmm) was used as the imputation method (Morris et al., Reference Morris, White and Royston2014).

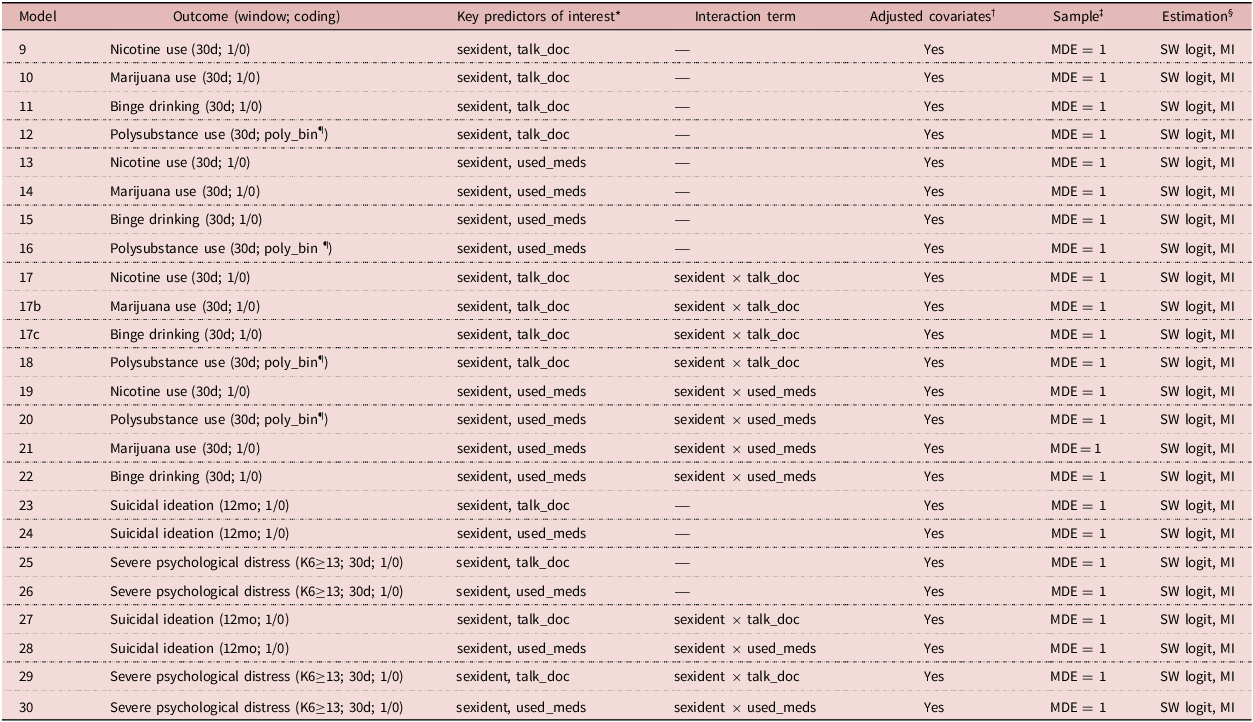

All later analyses were performed on the 20 imputed datasets, accounting for the NSDUH’s complex survey design (weighting, stratification, and clustering) in each step. For multivariable modelling, survey-weighted logistic regression models (svyglm function; family = quasibinomial) were fitted to each of the 20 datasets. The results (coefficients and standard errors) were then pooled into a single final estimate using Rubin’s Rules via the pool() function (Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011). Among respondents with MDE, separate models were fit to test for moderation by DRC or medication use, using interaction terms. Model specifications are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Multivariable survey-weighted logistic regression model specifications (NSDUH 2021–2023 veterans with past-year MDE)

* sexident = sexual identity (Heterosexual [reference], Gay/Lesbian, Bisexual). talk_doc = any past-year talk with a health professional about depressive feelings; no data on modality, session count/length/frequency, provider type, or fidelity (1 = yes, 0 = no [reference]). used_meds = any past-year prescription medication for depressive feelings no data on modality, length/frequency, provider type, or fidelity (1 = yes, 0 = no [reference]).

† Adjusted covariates in all models: age_cat, year, race, sex, edu, metro, insur, marital, emp, income_20k.

‡ Sample: All models restricted to veterans with past-year MDE (mde_yr = 1).

§ Estimation: Survey-weighted logistic regression (svyglm, family = quasibinomial, logit link) with complex design (PSU = verep, strata = vestr_c, weights = analwt2_c, nest=TRUE), run within each of m = 20 imputed datasets (MICE), pooled with Rubin’s Rules.

¶ Polysubstance use (poly_bin): 1 = ≥2 substance classes in past 30 days (from nicotine, marijuana, binge drinking, and prescription-misuse classes); 0 = none or single-substance.

Descriptive statistics (e.g., weighted proportions and confidence intervals) were also generated using the pooled imputed datasets. P-values reflect pairwise, survey-weighted logistic regressions (binary outcome ∼ sexual identity) fit separately within each of m = 20 imputed datasets; estimates were pooled using Rubin’s Rules (mice:pool) to obtain two-sided Wald tests with MI-adjusted degrees of freedom (Lumley, Reference Lumley2019).

Results

Of the total unweighted veteran sample with complete sexual identity data (N = 7,212), an estimated 95.7% identified as heterosexual, 1.8% as gay/lesbian, and 2.5% as bisexual when weighted. The sample was predominantly Non-Hispanic White (74.2%), male (89.0%), and over the age of 50 (75.3%). A majority of veterans were married (58.9%), had at least some college education (68.1%), and had health insurance (96.6%).

As shown in Figure 1, the pooled descriptive data revealed significant disparities in behavioural health outcomes by sexual identity. Marijuana use was reported by 33.5% of bisexual veterans (95% CI: [21.3%, 45.7%]) and 24.0% of gay/lesbian veterans (95% CI: [12.1%, 35.9%]), rates substantially higher than the 11.8% among heterosexual veterans (95% CI: [10.2%, 13.4%]). A similar pattern emerged for polysubstance use, with a prevalence of 30.6% for bisexual veterans (95% CI: [19.7%, 41.5%]) compared to 18.8% for gay/lesbian (95% CI: [8.6%, 29.1%]) and 14.9% for heterosexual veterans (95% CI: [13.4%, 16.4%]). Disparities were also pronounced for mental health outcomes. The prevalence of a past-year MDE was highest among bisexual veterans at 17.7% (95% CI: [9.4%, 26.1%]), compared to 6.6% for heterosexual (95% CI: [5.7%, 7.5%]) and 5.7% for gay/lesbian veterans (95% CI: [2.7%, 8.7%]). Likewise, rates of suicidal ideation and severe psychological distress were highest among bisexual veterans (10.4% and 15.1%, respectively), followed by gay/lesbian veterans (7.8% and 8.3%), and heterosexual veterans (3.2% and 5.2%). Prevalence of nicotine use was elevated for both gay/lesbian (35.8%) and bisexual (32.3%) veterans relative to their heterosexual peers (27.0%), while the difference was not statistically significant. Binge drinking rates were comparable across the three groups (19.7%–22.1%).

Figure 1. Weighted prevalence of behavioural health outcomes among U.S. Veterans by sexual identity, 2021–2023. The figure displays the survey-weighted, pooled prevalence of four substance use outcomes (top row) and three mental health outcomes (bottom row), stratified by sexual identity. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Brackets indicate statistically significant pairwise differences (p < .05) from pooled, survey-weighted models.

Main effects of sexual identity and treatment on behavioural health outcomes

In multivariable logistic regression models conducted on veterans with a past-year MDE, the main effects of sexual identity and treatment receipt were examined on substance use and mental health outcomes, controlling for all covariates. Bisexual identity was associated with significantly higher odds of past-30-day marijuana use compared to heterosexual identity (aOR = 3.32, 95% CI [1.43, 7.69], p = .008). In a separate model, receiving DRC was associated with a nearly threefold increase in the odds of severe psychological distress (aOR = 2.88, 95% CI [1.36, 6.09], p = .008), likely reflecting confounding by indication where those with more severe symptoms are more likely to seek treatment.

Moderating association of depression-related clinical contact (DRC)

The protective effect of mental health treatment was tested by introducing interaction terms between sexual identity and treatment receipt (Figure 2). Among veterans with MDE, DRC significantly moderated the association between sexual identity and several key outcomes. A significant interaction was found between gay/lesbian identity and DRC for binge drinking (p = .026). The risk of binge drinking was significantly elevated for gay/lesbian veterans who did not receive DRC, but this risk was substantially and significantly reduced for those who did (Interaction B = −3.44). A similar and even stronger protective pattern was observed for polysubstance use (p = .003), where DRC was associated with a pronounced reduction in risk specifically for gay/lesbian veterans (Interaction B = −4.13).

Figure 2. Moderating associations of depression-related contact (DRC) on predicted probability of adverse outcomes among veterans with past-year major depressive episode. The figure illustrates the interaction between sexual identity and DRC on the predicted probability of binge drinking, polysubstance use, and severe psychological distress. Points represent the pooled, survey-weighted predicted probabilities derived from logistic regression models adjusted for all covariates. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. The top row compares bisexual to heterosexual veterans, while the bottom row compares gay/lesbian to heterosexual veterans.

The models revealed a more complex pattern for other outcomes. For suicidal ideation, a strong interaction (p < .001) suggested that ideation was exceedingly rare among gay/lesbian veterans who did not receive DRC but significantly more prevalent among those receiving DRC, again likely reflecting that those with the most severe symptoms seek care. For severe psychological distress, a significant interaction (p = .018) indicated that among those receiving DRC, bisexual veterans had significantly higher odds of distress compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Moderating association of prescription medication use

A parallel set of interaction models examined the role of using prescription medication for depression (Figure 3). Medication use demonstrated a significant protective effect for gay/lesbian veterans for both nicotine use (p = .031) and polysubstance use (p = .005). In both models, the analysis revealed that the odds of these outcomes were significantly lower for gay/lesbian veterans using medication compared to their counterparts not using medication (Interaction B = −4.05 and B = −4.61, respectively).

Figure 3. Moderating associations of medication use on predicted probability of substance use outcomes among veterans with past-year major depressive episode. The figure illustrates the interaction between sexual identity and using prescription medication on the predicted probability of nicotine use and polysubstance use. Points represent the pooled, survey-weighted predicted probabilities derived from logistic regression models adjusted for all covariates. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. The top row compares bisexual to heterosexual veterans, while the bottom row compares gay/lesbian to heterosexual veterans.

The model for suicidal ideation revealed a highly significant interaction (p < .001) between gay/lesbian identity and medication use. This result indicated that while gay/lesbian veterans not on medication had significantly lower odds of suicidal ideation than heterosexual veterans, this protective association was not present for gay/lesbian veterans who were using medication. No other interactions with medication use were statistically significant.

Across nearly all models, being aged 65 or older was associated with lower odds of substance use and mental distress, while identifying as Non-Hispanic NH/OPI was associated with exceptionally high odds ratios, suggesting caution is needed in interpreting results for this subgroup due to potential model instability from small sample sizes.

Discussion

These results highlight meaningful disparities in substance use and mental health outcomes among U.S. veterans, emphasizing how sexual identity, demographic factors, and treatment engagement intertwine. Descriptively, bisexual veterans consistently showed higher prevalence of marijuana and polysubstance involvement, aligning with prior evidence that bisexual individuals experience unique stressors and stigma contributing to adverse outcomes. This may be attributable to bisexual-specific minority stressors, such as experiencing “double discrimination” or exclusion from both heterosexual and gay/lesbian communities, which can compound feelings of isolation and impede access to affirming support networks (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Operario and Mak2020). Gay/lesbian veterans, though less numerous in the analytic sample, also faced elevated risks for certain substances when suffering from depressive symptoms, underscoring the importance of targeted interventions for sexual minority veterans.

Interpreting these findings through a biosocial/biocultural lens clarifies why sexual-identity differences emerge and how treatment may buffer risk. This perspective links upstream social conditions (stigma in military/civilian contexts, differential social support, and geographic/economic constraints) to downstream embodiment (heightened distress, substance-use coping) and modifiable touchpoints (affirming psychotherapy, access to medications, integrated care). Consistent with minority stress theory (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003), sexual minority veterans face discrimination, stigma, and internalized homophobia that elevate depressive symptoms and substance use; these processes can be amplified among those with multiple marginalized identities (e.g., bisexual veterans with low income; lesbian veterans of colour), reflecting intersectional stress accumulation (Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009). This framing yields testable mechanisms for longitudinal work, for example, whether reduced stigma exposure, improved identity affirmation, or more continuous affirming care mediate the observed moderation by DRC and medications.

Among veterans with an MDE, the interaction models reveal that both DRC and prescription medication use can mitigate some of the heightened substance-use likelihood for sexual minority veterans. The notably large, negative interaction coefficients for gay/lesbian veterans suggest that mental health services are especially protective for this population, potentially lowering risks for binge drinking, nicotine use, and polysubstance behaviours. Because these exposures capture DRC, not structured psychotherapy, the moderation can be interpreted as consistent with the benefits of clinical engagement/affirming contact, not as causal effects of a particular therapy modality. These findings support the hypothesis that treatment can serve as a powerful buffer against minority stress (Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Rodriguez-Seijas, Jackson, Branstrom, Harkness, Safren, Hatzenbuehler and Pachankis2023). For gay/lesbian veterans, the significant reduction in binge drinking and polysubstance use among those with DRC is consistent with the hypothesis that affirming clinical contact helps manage stigma-related distress (APA Task Force on Psychological Practice with Sexual Minority Persons, 2021). Affirming therapeutic environments, in particular, can offer identity validation and a safe space to process experiences of discrimination, directly counteracting the core psychological mechanisms of minority stress (Kuo et al., Reference Kuo, Hashtpari, Chea and Tao2022). This finding underscores the salience of culturally competent, affirming mental health care, particularly given that stigma often hinders sexual minority veterans from seeking treatment (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Demographic characteristics also shape substance use risk. Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (NH/OPI) veterans consistently demonstrated strong positive associations across multiple substance-use models, warranting more nuanced investigation into the social and structural factors affecting this group. In contrast, college graduation, female sex, and residing in nonmetropolitan areas emerged as protective factors for certain outcomes, suggesting that both socioeconomic status and community context modulate substance-use vulnerability (Manietta et al., Reference Manietta, McLaughlin, MacArthur, Landmann, Kumbalatara, Love and McDaniel2024). Meanwhile, advanced age (65+) often correlated with reduced risk of binge drinking, highlighting a potential life-course effect that merits further exploration. However, research has indicated that the prevalence of binge drinking within the general population above the age of 65 is increasing (White et al., Reference White, Orosz, Powell and Koob2023). Future research could also explore whether strong social ties or close-knit community dynamics in certain nonmetro regions confer protective benefits, or if selection factors (e.g., veterans with lower risk profiles choosing to reside in rural areas) drive these observed differences.

From a clinical and policy perspective, these results underscore the value of inclusive, integrated approaches to veteran care and the importance of sustaining policies that enable them. Integrated care models (PCP–MH–SUD teams) remain central, but system-level levers matter too: fully resourcing VA’s LGBTQ+ Veteran Care Coordinator infrastructure and standardized SOGI data collection to ensure identification and linkage to affirming services (Kearney et al., Reference Kearney, Post, Pomerantz and Zeiss2014; Peter et al., Reference Peter, Halverson, Blakey, Pugh, Beckham, Calhoun and Kimbrel2023). Recent policy developments point both ways: the Bostock employment-non-discrimination ruling was associated with reductions in poor mental health among sexual minority adults, suggesting that inclusive policy can shift population risk (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Patel, Sandhu, Wadhera and Keuroghlian2025), while the Pentagon’s 2025 settlement to correct discriminatory discharge records for tens of thousands of gay and lesbian veterans may expand eligibility for benefits and care (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2025). At the same time, policy volatility (e.g., recent federal actions that scale back LGBTQ+ health-data collection and other protections) can heighten minority-stress exposures and deter care (AHCJ Staff, 2025). Accordingly, safeguarding and implementing inclusive policies within VA (routine SOGI capture, robust LGBTQ+ coordinators, settlement follow-through) is recommended, while monitoring external policy shifts that may influence sexual minority veterans’ access, stigma, and help-seeking.

Expanding access to evidence-based mental health interventions, particularly in a manner affirming of varying sexual identities, could reduce the disproportionate substance-use burdens observed here. Affirming care serves as a direct buffer to minority stress by providing crucial psychological resources. These include identity validation, which counteracts stigma; the development of emotion regulation strategies to manage the distress of discrimination; and the social support inherent in a trusting therapeutic relationship (Lattanner et al., Reference Lattanner, Pachankis and Hatzenbuehler2022; Seager van Dyk et al., Reference Seager van Dyk, Aldao and Pachankis2022). In practice, culturally competent care within the VA context entails specific actions, such as implementing inclusive practices for different sexual identities like using correct names and pronouns, offering trauma-informed therapy that acknowledges the history of discrimination, and providing ongoing training for providers on minority stress (Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Kauth, Shipherd and Street2014).

Finally, it is critical to recognize that these clinical interventions operate within a broader policy context that can either buffer or exacerbate minority stress. Policies that are exclusionary, such as past bans on military service for gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals or more recent restrictions on transgender service members, function as structural sources of stigma that directly impact the health of the populations examined in this analysis. Therefore, clinical progress must be supported by inclusive system-level policies. Key recommendations include the routine and standardized collection of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data in electronic health records to better monitor disparities and inform resource allocation, alongside the expansion and protection of LGBTQ+ specific programmes within veteran health systems. Future longitudinal research is essential to evaluate the impact of such policy changes and to allow for a more robust examination of how treatment influences substance use trajectories over time. By combining targeted outreach and culturally responsive care with advocacy for inclusive, evidence-based policies, veteran health systems can better mitigate substance-use risks and promote well-being for the diverse veteran population.

Several limitations temper these findings. First, the cross-sectional NSDUH design precludes causal inference and prevents establishing temporal ordering. Second, recall windows are not aligned; mental health and treatment variables are past-year, while substance outcomes are past 30 days, so reverse causation cannot be ruled out. Third, all measures are self-reported and thus susceptible to recall and social-desirability bias, particularly for sensitive behaviours (substance use, suicidal ideation) and sexual identity. Fourth, NSDUH treatment items capture occurrence only (any past-year talk with a professional about depressive feelings; any past-year use of prescription medication for depressive feelings) and do not assess modality, dose, duration, adherence, or whether care targeted SUDs versus depression; this increases the risk of residual confounding. Findings for severe psychological distress and suicidal ideation were mixed and are consistent with confounding by indication (i.e., those with greater distress are more likely to seek treatment). Fifth, sexual-minority subgroups were small, yielding wide confidence intervals and limited power for interactions; sparse cells in some race/ethnicity strata (e.g., NH/OPI) may produce unstable coefficients and constrain generalizability. Sixth, NSDUH samples the non-institutionalized civilian household population and excludes active-duty personnel, institutionalized individuals, and many veterans experiencing homelessness, so estimates may not generalize to all veterans or VA users. Seventh, although multiple imputation was used to address missingness, MI assumes data are missing at random; violations could bias estimates. Finally, multiple pairwise comparisons were conducted in descriptive analyses without formal multiplicity correction; accordingly, the effect sizes and confidence intervals were emphasized alongside p-values.

Conclusion

In this nationally representative, survey-weighted, multiply imputed analysis of 2021–2023 NSDUH veterans, sexual identity was a salient determinant of behavioural health. Bisexual veterans consistently exhibited the highest prevalence of marijuana and polysubstance use, while gay/lesbian veterans showed elevated substance involvement in the context of past-year depression. Among veterans with a MDE, engagement in DRC and use of prescription medication were associated with lower odds of key substance outcomes for gay/lesbian veterans, particularly binge drinking and polysubstance use, supporting the hypothesis that affirming mental health care can buffer minority stress. These inferences should be interpreted cautiously, given the cross-sectional design, reliance on self-reported measures, and non-aligned recall windows (past-year mental health/treatment vs past-30-day substance use), which preclude causal inference. Precision and generalizability are further constrained by small sexual-minority subgroups (including sparse cells within some race/ethnicity strata) and by the NSDUH household sampling frame, which excludes institutionalized and many unhoused veterans.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to thank the faculty at the College of Health and Human Sciences at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale and their unwavering support and mentorship.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organizations.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.