Since its inception in the 1960s, bi-musicality has become a standard fieldwork method for ethnomusicologists who study musical traditions outside their own cultural area. Broadly speaking, it consists of the process of acquiring sufficient musicality in the musical tradition of inquiry to foster deeper engagement and understanding in support of scholarly outcomes. The assumption is that the embodied experience of performing music cannot be replaced with intellectual knowledge and that experiential knowledge can provide valuable insight into the complexities of a foreign music tradition. Although this idea, inspired by the ethnographic method of participant observation of cultural anthropology, has been accepted and practiced by most ethnomusicologists in North America and beyond since Mantle Hood first proposed it in 1960, approaches to acquire bi-musicality, the extent to which it is pursued, and ideas of what one can gain from it, vary. For Hood, becoming bi-musical meant to overcome the biases of one’s own musical culture by readjusting our senses to hear new melodic intervals and to play new rhythms and instrumental/vocal techniques using traditional oral learning methods. He claimed that,

The crowning achievement in the study of OrientalFootnote 1 music is fluency in the art of improvisation. This is only possible after the student has become proficient in the technical demands of the art, so that he [sic] is free to follow the musical inventions of his own imagination. Needless to say, his inventions must be guided through the maze of traditional rules that govern improvisation (Hood Reference Hood1960: 58).

Idiomatic improvisation was thus the ultimate signature of Hood’s bi-musicality, something that required both technical and cultural knowledge. Other influential ethnomusicologists from the United States have added nuances and even expanded Hood’s formulation. Tim Rice, for instance, advocates for a form of bi-musicality combining the traditional learning methods advocated by Hood with disciplined, solitary study. He claims that studying and playing musical materials before engaging interlocutors in the field is advantageous for our bi-musicality aspirations because we gain crucial preunderstandings of the music. He asserts that the most valuable thing we learn from bi-musicality is “the experience and self-knowledge gained through a hermeneutic arc that transforms the self in moments of self-understanding” (Rice Reference Rice1995: 272). Yet for Jeff Todd Titon, bi-musicality “Can induce moments of … subject shift, when one acquires knowledge by figuratively stepping outside oneself to view the world with oneself in it, thereby becoming both subject and object simultaneously. Bi-musicality in this way becomes a figure for a path toward understanding” (Titon Reference Titon1995: 288). These scholars pose bi-musicality as a method for understanding the Other through self-understanding.

Although the most widespread path to bi-musicality has been learning to perform music at an acceptable level within the standards of the targeted tradition, some researchers have pointed out that there is a lot to gain from other forms of musical engagement, such as composition. Steven Feld, for instance, wrote that composing a song and sharing it with his informants was the only vehicle that allowed him to feel the most important issues of Kaluli ideals of sound expression and to inhabit their aesthetic reality in the Bosavi forest of Papua New Guinea (Feld Reference Feld2012 [1982]: 236–37). Michael Tenzer devised a method to discover the defining properties of a Balinese melody by playing to his informants a sample of variants that included existing versions and his own compositions (Tenzer Reference Tenzer2000, and personal communication June 2011). Thus, composition in the context of ethnographic research is not necessarily an end in itself, but rather “a frozen moment from an ongoing cross-cultural encounter, one in which the knowledge of the Other is always in process of formation” (Adler Reference Adler and Zorn2007: 10). In other words, it can be a means to develop, test, and question one’s bi-musicality. The utility of compositional bi-musicality combined with extensive research was well understood by renowned post-romantic nationalist composers from both sides of the Atlantic such as Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodáli, and Heitor Villa-Lobos since the turn of the twentieth century, and by early ethnomusicologists such as Charles Seeger and Kwabena Nketia, although most of these individuals did not use the term bi-musicality per se. A group of researcher-composers from Sub-Saharan Africa who have focused on the creative rather than the scholarly output of ethnomusicological research has called this method creative musicology (Ozah Reference Ozah2013; Lwuanga Reference Lwanga2013; Euba Reference Euba2014).

Like any ethnographic venture, composition as research runs the risks of cultural appropriation and misrepresentation. Ethnomusicologists such as Rice and Titon proactively address these concerns in their bi-musical models. In their view, the researcher is no longer a mere collector of information or the “objective” interpreter of cultures, but one who is engaged with the informants “in the intersubjective and dialogical coproduction of texts, contexts, processes, performances, interpretations, and understandings” (Titon Reference Titon1995: 290).

This article adds a voice to this group of scholars who approach bi-musicality through composition. I contend that, compared to the performance-centred approach, compositional bi-musicality deepens researcher self-reflexivity and facilitates dialogue with interlocutors in related yet distinct ways. Because the products of composition in this context are both works in process and highly revelatory of the researcher’s biases, they can function as a springboard for productive conversations with interlocutors in the field as well as academic colleagues. As will be discussed, the opportunities for feedback multiply when these compositions are rehearsed, performed, listened to, and analysed. I am therefore interested in composition as a creative activity that manifests and reflects the transformative experience of the researcher’s musical self as they explore one or more musical traditions. To intensify this transformational experience, I explore how compositional hybridity increases the possible combinations of musical materials and accentuates intersections and divergencies between genres.

The proposed approach joins a growing body of scholarship that problematizes the traditional divide between research and practice—particularly between research and artistic creation—in the social sciences, humanities, and the arts. Communication scholars Owen Chapman and Kim Sawchuk (Reference Chapman and Sawchuk2012) identify four modes through which research and creation intersect. Research-for-creation refers to the systematic gathering of materials intended to inform the creation of a new artistic work, whether or not that work is final (Reference Chapman and Sawchuk2012: 15–16). The above-mentioned nationalist composers and creative musicologists exemplify this mode. Creative presentations of research involve using artistic means such as a documentary film (e.g., Baily Reference Baily2003) or a music album (Carson Reference Carson2024) for the presentation and dissemination of traditional academic research. In research-from-creation, research may help developing “art projects that then stand on their own” or, more importantly, performances, experiences, and interactive art works that generate new research questions and data (Chapman and Sawchuk Reference Chapman and Sawchuk2012: 16). In the latter case, “there is a form of iterative design or testing that involves the participation of individuals or groups who may be an intended audience” (ibid.). Finally, creation-as-research “involves the elaboration of projects where creation is required in order for research to emerge” (ibid.: 19). This way of academic inquiry through practical action is also called practice-as-research (widely employed in Performance Studies) or action research. Bruce Archer (Reference Archer1995: 11) articulates its rationale: “There are circumstances where the best or only way to shed light on a proposition, a principle, a material, a process or a function is to attempt to construct something, or to enact something, calculated to explore, embody or test it.”

My own composition-as-research approach draws primarily from Chapman and Sawchuk’s latter two categories. In line with research-from-creation, I use the compositional process as a form of preparatory work before engaging in traditional fieldwork in Brazil. This creative work helped shape the focus of my research agenda, serving as a kind of embodied “literature review.”Footnote 2 In line with research-as-creation, I will show how the composing and rehearsal processes yielded insights that would not have emerged through conventional (i.e., performance-based) bi-musicality alone. While the resulting artistic product could stand on its own—as in research-for-creation—the ethnomusicological contribution that I want to highlight here is how composition led to critical moments of learning, understanding, and knowledge-making that shaped the direction and development of my investigation.

The role of composition within ethnomusicology is not unprecedented. For instance, the Society for Ethnomusicology’s Robert M. Stevenson Prize, established in 2003, “Honor(s) ethnomusicologists who are also composers by awarding a prize for a single composition, broadly defined as an original musical work created by the applicant.”Footnote 3 This recognition, along with numerous publications exploring the intersection between composition and research in ethnomusicology (e.g., Tenzer Reference Tenzer2003; Lechner Reference Lechner2009; Biró Reference Biró2013), reflects a well-established practice of composing among many ethnomusicologists.Footnote 4 My goal is to demonstrate how this compositional practice holds the potential to extend and enrich Hood’s concept of bi-musicality, pushing the field toward more integrative and practice-based methodologies that bridge the gap between theory and practice.

In this discussion, I analyse interactions of my fieldwork in Bahia, Brazil, with my experience composing the Suite Afrobrasileira to carry Rice’s and Titon’s conceptions of bi-musicality into the compositional domain. In doing so, I offer poly-musical composition as an efficacious modality for postmodern ethnography while examining the issues that such an endeavour presents. The Suíte Afrobrasileira is a five-movement suite that I composed between August 2010 and January 2011, inspired by various Afro-Brazilian genres (capoeira, Candomblé, and samba-reggae), funk, and jazz (see basic information of each movement in Appendix 1). It was rehearsed from January to April of 2011 and performed on 5 April 2011, at the Roy Barnet Recital Hall of the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) School of Music, in Vancouver, BC.Footnote 5 In my analysis, I explain how the process of creation, rehearsal, revision, performance, and post-performance analysis has contributed to intensifying my musicality in each of these genres in the manner proposed by Rice and Titon. To this end, I outline the conception of the project and the consequences of embracing hybridity; my attempts to distil defining features of certain genres and how I dealt with my lack of first-hand experiential knowledge; how I developed a concept for the work and my compositional method; the negotiations between my experience, the constraints of tradition, and the challenges of innovation; and how my conversations with musicians during rehearsal reshaped aspects of the piece, contributed to the co-production of texts, and furthered my understanding of myself and the music.

Conception of the project

The idea for the Suíte Afrobrasileira emerged from my desire to merge the jazz arranging techniques I learned from UBC Professor Fred Stride during a year-long course I took with him with my ongoing interest in studying the aesthetics of certain Afro-Brazilian genres in as much detail as I could. From the outset, I heard in my mind the horns of a big band combined with the rhythms of berimbaus (musical bows used in capoeira), atabaques (Afro-Brazilian sacred drums), surdos (carnival bass drums), agogôs (double-pronged bells), and vocals in a type of Brazilian Latin jazz setting. Hybridity was thus baked into my project from conception. As it turns out, the aesthetics of hybridity and fusion are widely embraced throughout Brazil, Latin America, and the African diaspora. In his influential Manifesto Canibalista (Canibalist Manifest), Brazilian modernist poet Oswald de Andrade suggested that Brazilians would discover their unique artistic voice by “cannibalizing” and assimilating both foreign and domestic cultural materials (Andrade Reference Andrade1928). This idea has influenced generations of Brazilian musicians, from Heitor Villa-Lobos to the participants of the Tropicália Movement in the late 1960s, and beyond. In a broader context, Paul Gilroy (Reference Gilroy1993) and Lorand Matory (Reference Matory2005) conceptualize the Black Atlantic as a place of cultural crossroads—a space of constant reinvention where African and diasporic influences intersect through ongoing processes of hybridity. Just as Gilroy identifies hybridity as a central force shaping the socio-political, cultural, and aesthetic dimensions of modernity in the Black Atlantic, Néstor García Canclini (Reference García Canclini2005) extends a similar argument to the Latin American context.

However, adopting hybridity as a guiding principle meant that I had to confront technical and ethical issues associated with cross-cultural composition. US composer Christopher Adler (Reference Adler and Zorn2007) notes the risks of using musical materials from a specific tradition without appropriate awareness of the contexts and cultural associations of those materials. Such practices are easily interpreted as cultural appropriation, a taking from, rather than a balanced encounter between musical traditions. In his hybrid compositions, Adler avoided the taking from problem by composing original melodies that invoke the aesthetics of the tradition rather than directly quoting or superimposing traditional material.

My choice of melodies, lyrics, rhythms, and instruments from traditional Afro-Brazilian genres for the suite was based on cultural associations I learned during my time of fieldwork in Brazil in 2006 and 2009, as well as the twelve years of dedicated capoeira practice that I had at the time of the composition. I used the metaphor of a roda de capoeira for the organization of the suite. A roda de capoeira (lit. capoeira circle) refers both to the circle formed by practitioners during performance and to the performance itself. Drawing on the latter meaning, I respectively based the first and the last movements on types of songs typically used to open and close capoeira performances. The berimbau, a recognized emblem of Afro-Brazilian culture, is prominently featured in these two crucial moments of the suite (beginning and ending) in accordance with the suite’s title.

I also used Adler’s solution of creating new melodies, rhythms, and songs to avoid the risks of cultural misinterpretation. In the fourth movement, “Caboclagem,” I employ Adler’s new-material approach to navigate my compositional interaction with the Afro-religious music of Candomblé it is inspired by. Practitioners believe that Orixás (African deities worshipped in Yoruba ceremonies across the Black Atlantic) and other superhuman entities can be summoned through codified rhythms—deities respond to properly executed grooves by possessing initiated dancers. As I have written elsewhere (Díaz Reference Díaz2016), it is understood that these grooves are meant to be played only under the controlled conditions of a worship house, not outside, where dancers may become possessed without the support they need. Likewise, Candomblé songs in African languages are considered sacred, powerful, and belong to ritual settings. Although devotees appreciate certain recontextualizations of Candomblé music in public settings, they are critical of any attempt to transfer drum patterns and songs in African languages. This scepticism is part of a history of secretiveness in Candomblé associated with its religious nature and waves of persecution (Johnson Reference Johnson2002). I thus created grooves based on those that I had learned from my teacher Macambira during my 2009 visit to Salvador, but with key deviations and, more importantly, using non-consecrated drums. With these adjustments, I imbued my work with the sonic influences of Candomblé without setting sacred material in what would be considered inappropriate contexts. Because Candomblé audiences are less concerned about melodic borrowing than with song language, for the songs of “Caboclagem” I rephrased melodies of various ritual songs and, in one instance, collated them together in a kind of potpourri. I wrote my own lyrics, using sacred words such as “Saravá”Footnote 6 and names of some Orixás, but making sure not to reproduce full sentences. My song melodies thus emerged from my experience attending Candomblé ceremonies in Salvador, taking lessons with Macambira and other teachers, and intensive listening sessions of commercial and field recordings. It is important to point out that Candomblé is considered by many Brazilians and scholars as the practice where African retentions have been kept at the highest degree, and this makes it instrumental for those like me, who are interested in exploring Afro-Brazilian sounds. These considerations were less important while conceiving the movements inspired by capoeira and samba-reggae because practitioners of these genres tend to be less concerned with public representations of their music.

Developing a set of tools: looking for “essentials”

In this cross-cultural project, my main concern was to find a common ground where the languages and instruments of capoeira, samba-reggae, Candomblé, funk, and jazz could converse fluently while maintaining their individual identities. To this end, I felt the need to identify a defining set of characteristics for each genre. My reasoning was that having these elements available in my palette would help me make the presence of specific genres felt at different moments of the composition. This was the first moment when my varying degrees of musicality in each of these music traditions was tested. By the time of the composition, I had practiced capoeira angola for more than a decade and felt confident musically in it. But I could not say the same about the other genres: I had been exposed to samba-reggae and Candomblé during my visits to Salvador in 2006 and 2009 through drumming lessons and attendance at performances and I also read some of the scholarly literature. Regarding jazz, I have been an avid jazz listener since 2008, took theory and practical private lessons in Managua in 2008, and took a year-long course on jazz theory and arranging at UBC in 2009–2010, in which I wrote a big band arrangement for a jazz standard that was performed twice. Despite its conspicuous presence in the global popular culture and in Brazil itself, funk was perhaps the least familiar genre for me.

My varied familiarity with these genres was a challenge that propelled me towards my first goal: forcing myself to study the aesthetics of these genres to advance my musicality in each. In the case of samba-reggae, I replayed, studied, and transcribed field recordings from my 2009 trip to Salvador of my carnival percussion lessons with Renato Kalile and of performances of two renowned carnival ensembles from Salvador: Olodum and Bloco Ivan Santana. As in any carnival ensemble in Brazil, instruments in blocos afro (the name of the ensembles playing samba-reggae) have normative roles, each adding a layer to the polyrhythmic texture. There are introductory phrases (convenções), closing cadences, and various types of breaks (paradinhas) that interrupt the flow of the groove, adding interest and contrast to the music. In my study of the transcribed materials, I focused on the characteristic patterns of each part (four surdo parts, the snare drum, the repique, and the timbal), and the most typical breaks used to open or punctuate sectional changes. I elaborated on what I found in this process and used it in the second and third movements of the suite. My first-hand experience with Macambira and Kalile in 2009 helped me identify the normative roles of the bloco afro, to feel the grooves in my body, to think about them while playing them, to give and receive cues for the convenções and paradinhas, as well as to appreciate the importance of community in music making. I tried to integrate all these aspects into the suite.

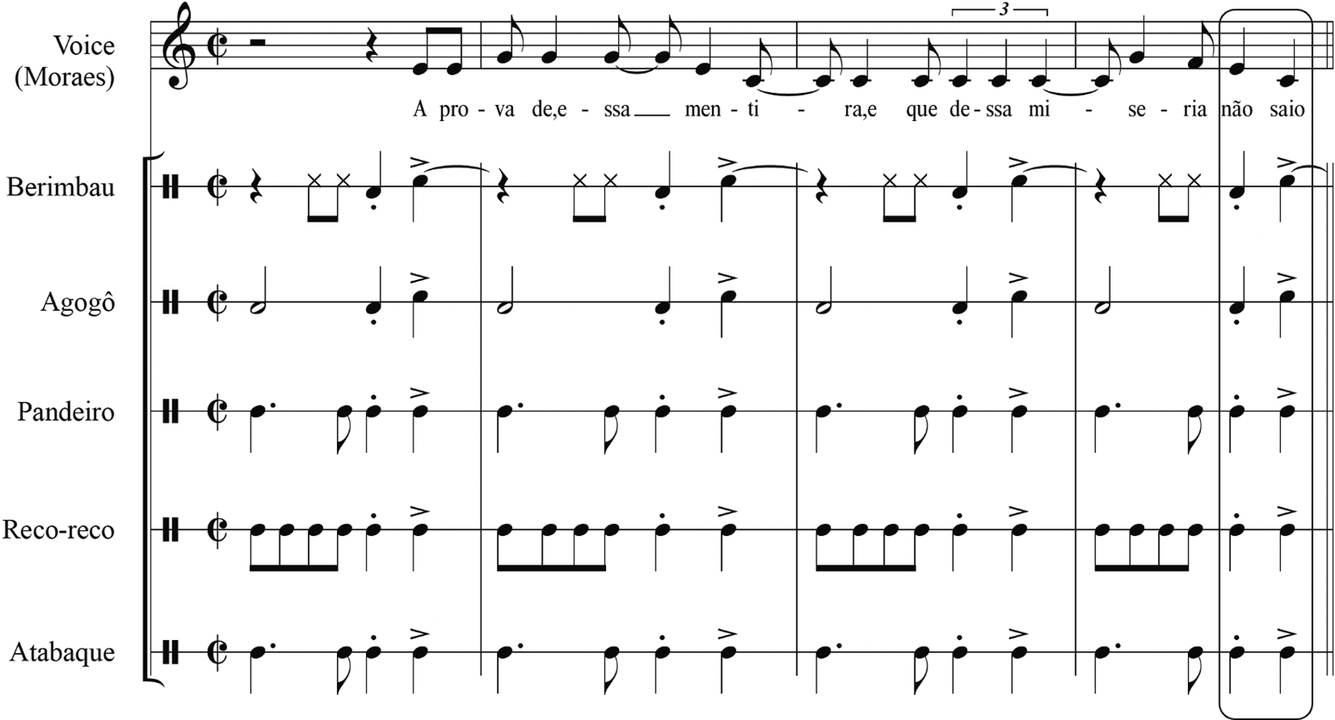

For Candomblé, I did something similar. I studied and transcribed the recordings from lessons with my teacher, Macambira, and a commercial video that he prepared for study. I chose the toques of Oxossi and Ogum because I spent more time studying them and because they have contrasting metric structures (respectively 4/4 and 6/8), convenient to add rhythmic variety to my piece. In Candomblé ceremonies, responsorial songs are accompanied by grooves played by three conga-like drums of different sizes called atabaques and a bell (agogô). Instruments and singers play normative roles as in many West African drumming traditions: the bell plays a timeline ostinato and the atabaques play contrasting patterns contributing to a polyrhythmic texture. The largest atabaque (called rum in the Yoruba-derived Candomblé tradition) leads the ensemble and uses variations to converse with musicians, dancers, and singers. I used these normative roles to organize the rhythmic structure of “Caboclagem,” but I transferred the leading role of rum to the conductor for two reasons: First, I did not have an available seasoned rum player who could assume that role; and second, the Candomblé ensemble was paired with a big band which had no experience interacting with master drummers but was rather accustomed to rely on scores and a conductor. During performance, I conducted the Candomblé ensemble and interacted with a second conductor, who led the big band (Stride). While the former group memorized the music and relied entirely on memory and my gestures, the latter read the parts from the scores I provided and followed the cues from Stride. By taking away the leading role from rum and reducing it to playing fixed patterns, one of the core features of Candomblé music was compromised. This compromise, however, allowed me to put in conversation two musical traditions that greatly differ in their performance practices. On the one hand, jazz big bands rely heavily on notation and a conductor; on the other, Candomblé music is not notated, is led by one of the drummers, and needs to be more flexible because it is at the service of ritual. That flexibility is crucial within the ceremonial context, but not in the performance of the Suíte Afrobrasileira.

My approach to funk was different. Funk and soul, perceived in Brazil as a modern musical product of the African diaspora, reached Brazil at the beginning of the 1970s. A decade later, they became popular among black working-class youths in large cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and Salvador (Sansone Reference Sansone2004: 171–74). They inspired local styles of funk that ended up being produced electronically (funky) and were almost always associated with a form of dance known in Brazil as baile funk. Footnote 7 They also inspired some blocos afro from Salvador to create purely percussive funk grooves for carnival and other street celebrations (ibid.: 175). Despite the important role that funk music and dance have played in the construction of Afro-Brazilian identities for some black youths, my exposure to Brazilian funk was meager. This is basically why, for the third movement of the suite, “Funky Capenga,” I decided not to use Brazilian funk as an inspiration, but rather the Bahian bloco afro funk grooves and the brass-heavy tradition of US funk. From the beginning, I conceived this movement as more experimental than the others (e.g., the grooves are in 5/4 as opposed to the conventional 4/4) and knew that this could be interpreted as a drastic departure from Afro-Brazilian aesthetics. I strategically placed it in the middle of the suite.

Experimentation was not a renunciation of core characteristics. I listened to many commercial recordings, especially those by James Brown (who was a great influence for Afro-Brazilians during the 1970s and 1980s), to get a general taste of US funk. I noticed that the music is groove-driven with simple quaternary metric structures emphasizing beats 2 and 4, based on repeating music figures or vamps played over fairly stable harmonies, and that the rhythm section improvises the accompaniment while assorted horns are responsible for the vamps and for melodic improvisation. Basslines tend to be syncopated, driving the groove forward and giving it a “cool” feeling. I transcribed some funk grooves that I recorded in the field from the bloco afro Olodum in 2009 and found out that the roles of all the instruments tend to be separated into only 2 or 3 parts, as opposed to the 6 or 7 that appear when they play samba-reggae. For instance, instead of playing four contrasting patterns as in samba-reggae, surdos in funk articulated in unison the first beat and the second offbeat in a simple quaternary metric framework. The high-pitched drum section (snare drums and repique) filled the empty spaces in different ways. Convenções and paradinhas functioned similarly as in samba-reggae. A common feature between US and Bahian funk is that they often alternate two or three distinct grooves (called vamps in North American funk or toques in bloco afro) in the same piece. This helped me to give form to “Funky Capenga.”

In contrast with the rest of the genres I was dealing with, the big band jazz tradition draws upon a substantial body of theoretical literature on composing and arranging. Access to this body of work, along with what I learned from Stride in 2009 and 2010, allowed me to maintain the overt presence of jazz throughout the suite. I used typical harmonic progressions of the swing and bebop eras (the focus of Stride’s course) and rephrased melodies, often avoiding downbeats to give them the propelling sense that characterizes the genre. I used the four sections of the band (saxophones, trombones, trumpets, and rhythm section) idiomatically: the rhythm section mostly improvised an accompanying groove; melodies within a section were in unison, octaves or voiced; sometimes one (or two) sections carried the main melody while the remaining were silent, played pads, or played counter melodies; and sometimes all the horns would play homophonically. However, I departed from the typical chorus big band arrangement form (e.g., intro, melody chorus, various choruses for improvisers, a chorus for a soli, a chorus for a shout, out chorus, and ending) and explored different structures in each movement, trying to incorporate formal aspects of the other genres. While there are recognizable features of jazz, it is a genre with decades of experimentation and innovation, making claims of definitive characteristics contentious. For the suite, I chose the language and instrumentation of two early styles of jazz: 1940s swing and bebop.

Developing a compositional method

I already discussed how I adopted hybridity as a central concept for the Suíte Afrobrasileira and some of the implications of this decision. This concept emerged from my desire to explore the sonic characteristics and the cultural associations of four sets of instruments (a jazz big band, a capoeira ensemble, a Candomblé ensemble, and a bloco afro) and vocals. According to Adler, developing a central concept for the work “motivates a compositional method and the particular ‘set of tools,’ familiar or newly created, from which the work will be built” (Adler Reference Adler and Zorn2007: 21). In my case, the compositional method revolved around the idea of pairing, in each movement, the jazz big band with one of the other three ensembles and creating something that would sound like capoeira, samba-reggae, funk, or Candomblé to enculturated listeners. Although the characteristic timbres of each Afro-Brazilian ensemble helped identify these genres in each movement, I worked hard to ensure that the instruments played idiomatic passages in key moments. For instance, in the introduction of “Ladainha” (Mov. I), the capoeira ensemble exchanges phrases in call-and-response with the big band in a way that is uncharacteristic of capoeira performance. However, those phrases are evocative of capoeira aesthetics in two ways: first, their rhythms are elaborations of typical patterns played by the berimbaus, specifically of a pattern known by practitioners as toque de angola; second, because berimbau patterns alternate two pitches separated by an interval between a minor and a major second, when I voiced these phrases for the big band, I made sure that the top notes were only separated by a second, either minor or major.Footnote 8 Furthermore, as toque de angola and many of its variations tend to start and stay on the low berimbau pitch and cadence on the raised pitch, I voiced the big band phrases in this section in such a way that the top notes followed this melodic movement. The section that follows the introduction is more explicitly evocative of capoeira aesthetics as it features a sung solo ladainha (an introductory song in capoeira performance) in Portuguese composed by me with a melody recognizable by practitioners and accompanied by an ensemble of five berimbaus (the iconic instrument of capoeira), five hand drums, two pandeiros (tambourines), one double-pronged bell called agogô, and a scrapper known as reco-reco. Although this ensemble is an extension of the typical capoeira angola ensemble that I wanted to evoke (the traditional ensemble would feature three berimbaus rather than five, and one hand drum called atabaque rather than the five conga drums I used), these instruments played normative roles within capoeira aesthetics, creating a familiar texture and timbre to any capoeira practitioner.Footnote 9

The big band was my laboratory to conceptually test the set of core characteristics I researched for each genre. This is why I decided to use the big band in every movement. The very exercise of trying to translate features of each Afro-Brazilian genre to the big band gave me the opportunity to experience the transformation that self-understanding offers (Rice Reference Rice1995). For instance, in a passage of “Samba Estrela” (Mov. II), I tried to transfer the polyrhythmic texture of the bloco afro to the three horn sections of the big band. Of course, the big band has its own sonic constraints, and this limited my choices. One of my solutions was to write a modified version of the caixa (snare drum) part at two different rates for the trombones and saxophones, while the trumpets carried the main melodic idea. It may not have been the best sonic solution or stylistically sound, but the process of integrating these concepts compositionally deepened my jazz and samba-reggae musicalities. I internalized a set of stylistic features not by memorizing and reproducing them but by manipulating and stretching them, sometimes trying to find their limits, ultimately discovering the underlying concepts that govern them. In other words, I made the knowledge mine as I tried to apply it to a hybrid setting. Following a different path, I became bi-musical in the ways Rice described in his 1995 essay.

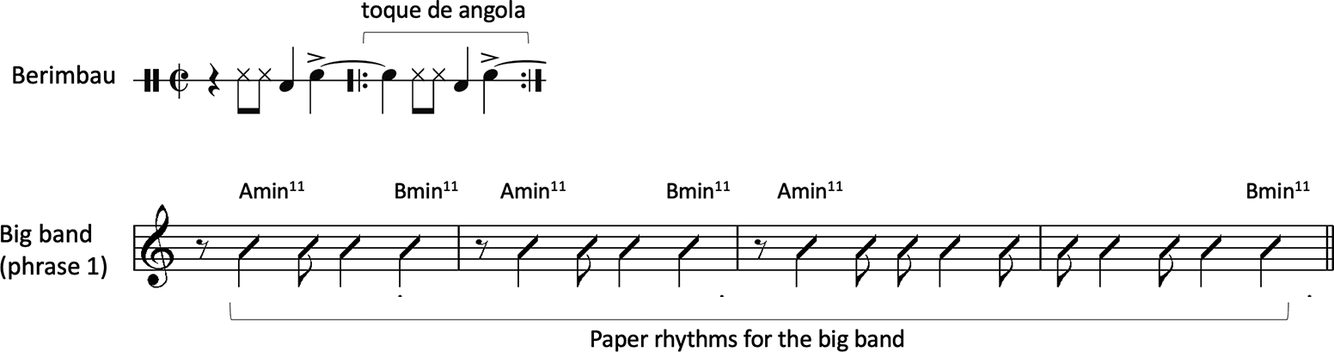

However, transferring patterns and concepts from Afro-Brazilian genres directly to the big band format was not always possible, appropriate, or fully satisfying. Ethnomusicologists such as Bruno Nettl (Reference Nettl2015: 294–301) have documented the tensions that arise in the interaction between aural and written traditions—particularly the ways oral patterns and melodies are often standardized and westernized when transcribed into staff notation. These issues are especially relevant to compositional projects like mine, which engage with oral genres, multiple notational systems, and the transcription of recorded music. Kofi Agawu points out that creating “paper rhythms,” those transferred from oral to written musical cultures for analytical (in my case, also for compositional) purposes, allows for a series of abstract operations that may have no resonance with the host cultural mode of expression (Agawu Reference Agawu2006: 36–37). The rhythms I discuss in the introduction to “Ladainha” may be regarded as “paper rhythms” because they stretch rhythms and add harmonies and timbres foreign to the capoeira tradition. Figure 1, for instance, shows how I created a non-idiomatic phrase based on a traditional berimbau pattern (toque de angola). But as I have explained, this phrase bears some resemblance to variations of toque de angola played by berimbau players in capoeira. I found that loosening strict adherence to the capoeira toque opened the harmonic potential of the big band. In this way, I found that achieving hybridity in “Ladainha” required me to be attentive to capoeira aesthetics yet flexible enough to experiment so that the character of other influences could co-exist.

Figure 1. Toque de angola and associated paper rhythms for the big band in the opening of “Ladainha” (Mov. I).Footnote 10

Roughly speaking, my method consisted in:

-

1. Choosing one Afro-Brazilian ensemble to be paired with the big band for each movement. These ensemble configurations were joined by a choir in Movements I, II, III, and V.

-

2. Looking for a set of defining characteristics of the Afro-Brazilian genre of each movement and generating a set of associated “paper rhythms” to be used across the movement.

-

3. Composing (or adapting from traditional repertoires) one or various melodic themes for each movement.

-

4. Making a sketch of the piece’s form

-

5. Writing the different sections and transitions for both ensembles

-

6. Trying to create some kind of synergy between both ensembles by transferring some of the defining characteristics of the Afro-Brazilian genre in question to the big band—e.g., creating textures resulting from idiomatic normative roles.

“Fechando a Roda” (Mov. V), inspired by three responsorial capoeira songs typically used to end performances (“Eu já vou Beleza,” “Adeus Corina,” and “Adeus, Adeus”), and by a set of berimbau toques, is a good example of how this compositional method works. Being the closing movement, I planned to make it sound like a grand finale by using three instrumental ensembles (the big band, the capoeira ensemble, and the bloco afro) plus a choir. I wrote materials for each, but soon after rehearsals started, I realized that this combination oversaturated the texture and decided to rule out the bloco afro. I used three corridos (responsorial songs used to accompany physical games) from the traditional repertoire of capoeira as central themes. The form of the movement is articulated by several passages I wrote based on elaborations of these three corridos, and an original samba-like theme to close. I also revisited materials from the second and third movements and wrote various grooves for the capoeira ensemble, some traditional, others original. Table 1 shows a detailed sketch of this piece’s form.

Table 1. Layout of sections of “Fechando a Roda” (Mov. V) a

a Listen to “Fechando a roda” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LjzHvRcIHMg.

b Orquestra de berimbau is a relatively new kind of ensemble created by capoeira practitioners focusing on purely musical arrangements for the berimbau. Pieces by these ensembles typically feature a sequence of grooves separated by homophonic breaks, in the fashion of Brazilian carnival ensembles (see Díaz Reference Díaz2021, Chapters 6 and 7).

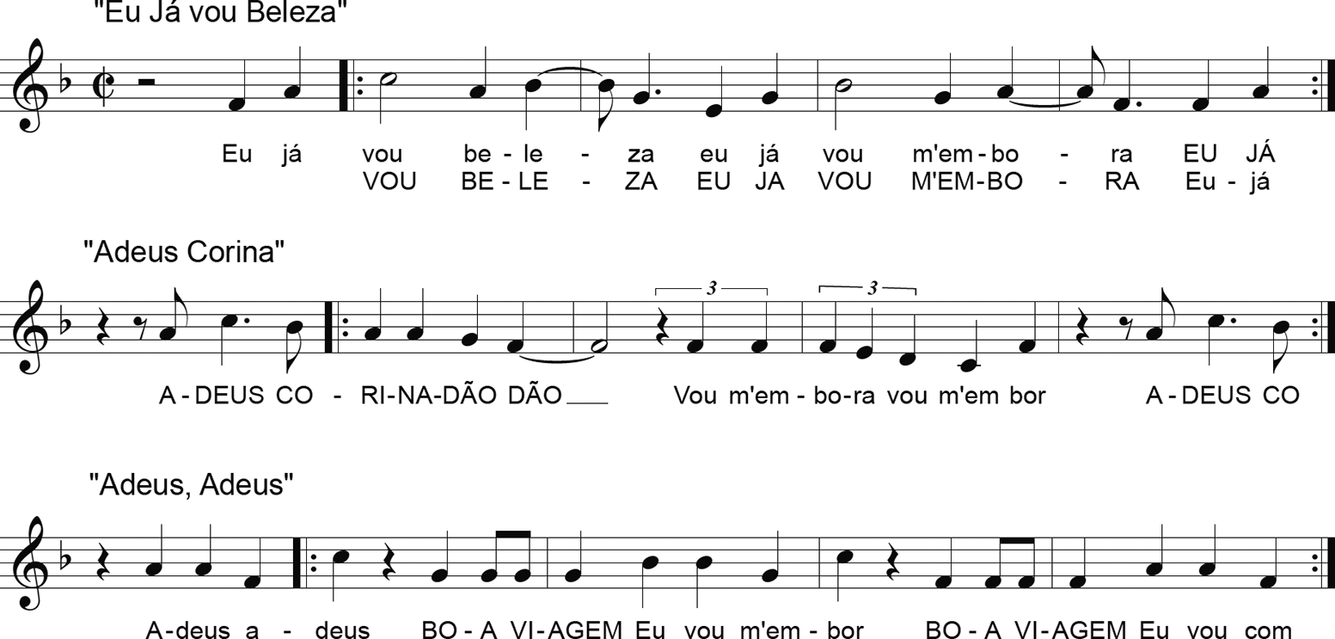

In this last movement, I was more open to sacrifice clarity for the sake of experimentation. In section E, for instance, I tweaked the melodies of “Eu Já vou Beleza,” “Adeus Corina,” and “Adeus, Adeus” to combine them in a thick counterpoint (see Table 1). In my final solution, I gave each of these melodies to each of the three horn sections (saxophones, trumpets, and trombones), and the result was an obscure texture where “Adeus, Adeus” got drawn and where many melodic and rhythmic clashes happened. I tried several eclectic versions of these corridos, always attempting to keep their identity by maintaining certain key notes in their place. For this section I was partly inspired by what Michael Tenzer (Reference Tenzer2000) did with the melody of a well-known Balinese piece called “Baris.” During the writing process, I sent a MIDI sequence containing the D section to the capoeiristas who were familiar with these corridos. However, no one recognized them. Only John Kastelic (a music composition major at the time) said that he could feel something from capoeira, but he was not sure what it was exactly.Footnote 11 In this case, I made no changes based on their feedback.

My melodic manipulations included rephrasing and transposing known capoeira melodies. For instance, the trombone version of “Adeus Corina” in Figure 3 (mm. 145 to 148) is a rephrased version of the recognizable capoeira melody shown in Figure 2, but a third down. After that, I roughly kept the same melodic contour but experimented more with the pitches, mostly to avoid melodic clashes with the top voices of the other two sections. For instance, in mm. 153–160 I transposed the melodic idea of the previous eight bars a fourth up (to Bb major) keeping the original chord progression. As most capoeiristas in a roda would not sing “Adeus Corina” or other corridos against an implied harmonic background, they could interpret my transpositions of the song’s melody as being out of tune.Footnote 12 Furthermore, the mere idea of hearing these three corridos simultaneously is foreign to capoeira aesthetics and may be acceptable only to a few.

Figure 2. Traditional versions of capoeira songs “Eu Já vou Beleza,” “Adeus Corina,” and “Adeus, Adeus” heard at Fundação Internacional de Capoeira Angola (FICA), Salvador (July 2009).

Figure 3. “Fechando a Roda,” section E.Footnote 13

In sum, developing and using a compositional method in “Fechando a Roda” allowed me to earn experiential knowledge by assessing the recognizability of a melody at various degrees of alteration. Paper rhythms allowed me to experiment with song melodies and advance my capoeira musicality.

Negotiating among experience, tradition, and innovation

The act of writing a cross-cultural piece like the Suíte Afrobrasileira is the result of multiple negotiations between the composer’s experiences (musical and otherwise), the constraints of various music traditions, and the challenges of innovation (Adler Reference Adler and Zorn2007: 31–32). I have presented my credentials in each genre involved in the suite and I only must add that my experience composing cross-culturally was minimal. Thus, I did not have a specific voice formulated through years of composition, a reputation to keep, or high expectations on the quality of the final product. Understanding that my compositional method could only reflect my own cross-cultural experiences, as Adler (Reference Adler and Zorn2007: 31) puts it, gave me the freedom to focus on my agenda: advancing my musicalities through study and experimentation with the materials and symbolism of various genres.

I used the big band jazz music tradition as a common ground to put the languages and instruments of capoeira, samba-reggae, Candomblé, funk, and jazz in conversation. But I was also concerned with keeping certain aspects of each musical tradition. My challenges were thus varied: Where does one look for tradition? Who are the bearers of tradition? Is it possible to characterize it and delineate boundaries around it? If so, how? Postmodern discourse in ethnography-based disciplines such as anthropology and ethnomusicology sheds light on these important questions (Clifford Reference Clifford1988:15). This discourse emphasizes the emergent, contingent, and pluralistic nature of traditions and the positionality of the participants and observers. All this resonates with the fast changes that many Afro-Brazilian music traditions have experienced in Bahia since the 1970s, driven by processes of African revival and adaptation to a growing tourism industry eager to consume “authentic” Afro-diasporic culture (Sansone Reference Sansone2004; Pinho Reference Pinho2018). Musical instruments, techniques, rhythms, songs, and concepts have circulated fluidly among Afro-Bahian genres, blurring the boundaries that separate them and characterizing them stylistically. Many authors have studied the complexities resulting from these flows (e.g., Diniz Reference Diniz2010; Henry Reference Henry2008). When taken literally, the postmodern approach propels us to look for tradition everywhere, thus challenging the validity of my search for emblematic or defining features. However, it is also important to recognize that despite the multiple overlaps of traditions, practitioners of these genres make conscious efforts to give distinctive sounds to their musics. Some of these efforts produce palpable results. For instance, Mestre Moraes (Pedro Moraes Trindade) and his capoeira students at the Pelourinho Capoeira Angola Group (GCAP for its initials in Portuguese) have worked consistently in Bahia since the 1980s to preserve and develop a particular style of capoeira angola that has become the most influential among the global capoeira angola community. This style, known as capoeira angola pastiniana (purported to follow the teachings of a seminal mestre from Bahia called Pastinha and his two main students, João Grande and João Pequeno), has been followed and expanded by many of Moraes’s students, including mestres Cobra Mansa (my own mestre), Valmir, Jurandir, Neco, Braga, Zé Carlos, Boca do Rio, Janja, Paulinha, Poloca, and others. Although each mestre has his or her own particularities and views, it is possible to find a set of commonalities that define their style, their tradition. Such shared features include aspects of instrumentation (e.g., the use of three berimbaus playing complementary patterns), song repertoire (e.g., the use of the ladainha—chulas—corridos sequence), attire (e.g., uniforms with black pants and yellow T-shirts), and musical content (e.g., the use of toque de angola played at moderate tempo).

Innovation may be interpreted as the freedom to stretch the boundaries that practitioners set around tradition. However, how does one responsibly and effectively use that freedom in a hybrid composition that aspires to have an Afro-Brazilian identity? To illustrate the ways in which I faced this question, I will refer to the process of learning physical movements in capoeira. Anthropologist Greg Downey explains that while learning capoeira at GCAP in Salvador, his instructors discouraged him from repeating movements too literally: “Far from being regarded as skilful, too faithful repetition was considered dreadfully boring, counterproductive for learning, and anathema to a cunning game” (Downey Reference Downey2005: 28). He then elaborates by writing that learning a specific movement “actually requires being able to produce an infinite number of variations, appropriate in different situations.” The ability to execute the right variation in the right circumstance “demands the acuity of a virtuoso” (ibid.: 28–29). Therefore, tradition in capoeira is not to be equated with the constraints of faithful repetition of physical movements. It rather entails the challenges of internalizing countless variations of those movements and choosing the “right” one for a specific situation. The physical performance of capoeira is therefore an exercise of creative and spontaneous recombination of internalized material. The same applies to the practice of berimbau improvisation, where players recombine, expand, or truncate a finite number of known patterns. These forms of variation (i.e., innovation) are thus baked into capoeira tradition.

For the Suíte Afrobrasileira I operationalized these ideas about capoeira tradition, limiting the scope of innovation to the generation of a set of possibilities from which one can appropriately choose. I thus produced a set of idiomatic variations out of the core characteristics of each genre that I identified through study, and decided, by trial and error, what variation suited a specific situation. For the big band, I relied on the jazz arranging techniques I learned from Stride—rephrasing and reharmonizing melodies, melodic augmentation and diminution, voicing in various ways, etc. For samba-reggae, I composed a theme song following the aesthetics of other samba songs I’ve heard from emblematic groups such as Ilê Aiyê and Olodum. I created grooves and breaks following normative roles of this genre, following what my Bahian teachers taught me and what I had witnessed during my visits to Bahia. For Candomblé, I created two theme songs, collating and rephrasing melodic fragments of traditional songs, and wrote my own lyrics emphasizing references understood by locals as symbols of Afro-religious hybridity (e.g., the Caboclô deity). I also used the normative roles of the Candomblé percussion ensemble, where the agogô bell provides a temporal framework for the polyrhythms played by three drums. Finally, for capoeira, the genre I had more experience with, I composed a theme song based on the aesthetics of the ladainha and used the normative roles of the capoeira ensemble that accompanies it. I also rephrased, transposed, and overlaid variations of three responsorial songs used to close the capoeira performance. Finally, I used berimbau patterns and elaborated them using similar techniques that practitioners use when they improvise.

The first movement is a good example of how I conjugated my experience with this understanding of tradition and innovation. The central theme of the movement is a ladainha I wrote in a class I took with my mestre, Cobra Mansa, during my first visit to Salvador in 2006. The practice of composing or improvising ladainhas is common among senior practitioners but less so among younger students, who are thought not to have internalized the stylistic fundamentals of these important kinds of songs. In the lesson, when I composed my ladainha, mestre Cobra Mansa created a rare learning opportunity for his students to explore ladainhas, focusing on text setting. We were asked to write our own lyrics, structure them in quartets or sextets following a simple four-line or six-line rhyme scheme (i.e., ABCB or ABCBDB), and to sing each of those stanzas conforming to a few well-known rhythmic-melodic formulas that we all have heard on seminal recordings and on performances.Footnote 14 Those formulas are part of what I call the defining features. I used them for my ladainha back in 2006 and for the first movement of the suite in 2010.

As mentioned, the movement starts off with an introduction in call-and-response between the capoeira ensemble and the big band. Subsequently, the ladainha is sung by a solo singer to the accompaniment of the capoeira group, as it is done in traditional capoeira performance. The difference is that I added harmonic accompaniment by the piano and double bass. As in conventional capoeira performance, I followed the ladainha with short responsorial songs called chulas (or louvações) led by the same singer of the ladainha and responded by the rest of the participants. Next, and without the capoeira ensemble, the big band plays a stylized version of the ladainha, and the melodies progressively depart from capoeira aesthetics. This is followed by a responsorial section where a single tenor saxophone takes on the role of the chula caller and the rest of the horns stand for the choir. Although the first exchanges between these two parts resembled capoeira chulas melodically and rhythmically, the last of those exchanges departed from normative practice with a longer solo section for the saxophone, which the big band eventually responds to. While this extended improvised solo has no equivalent with chula singers in capoeira, I inserted the solo to represent the agency that singers are given to add lyrics and modify the melodic framework. In my arrangement, this freedom was externalized through the aesthetics of jazz melodic improvisation. After this chula section I included a restatement of two ladainha stanzas, but at half speed, further departing from conventional practice. Following conventions of big band arrangement, I also introduced harmonic modulations. For instance, the ladainha modulates from C major to A major and returns to C major for the chulas. Modulations as such are not part of capoeira performances since the lead singer of a given piece sets the range and usually stays in a fixed tonality. However, in an environment where singers take turns leading corridos, the tonality may shift between corridos per the vocal range of each leader. Thus, the harmonic modulations in this movement are conceptually linked to the tonal shifts that incidentally occur throughout capoeira performances, but sonically rooted in the big band jazz tradition that unifies the whole work. Because the capoeira groove consistently accentuates the fourth beat of each 4/4 measure, I decided to emphasize this metric position both dynamically and harmonically by placing chord changes on this point rather than on the downbeat. The melodies and their variations were inspired by the singing style of my capoeira mestre (Cobra Mansa), and of his mestre (Moraes), an influential figure in this art. For me, these compositional decisions based on insights I have gained through years of immersion as a capoeirista define and shape the identity of the piece.

These staggered departures from conventional ladainha melodies created opportunities to test the limits of variation and to assess the essential factors and features necessary for practitioners to recognize them as such. After rehearsals of “Ladainha” with the big band, I had many informal conversations with the capoeiristas who participated in this piece, where we spoke about the capoeira-inspired melodies I wrote for the big band. While listening together to recordings of the rehearsal, I learned that they could easily recognize the ladainha’s melody in the first stanza I wrote for the horns (see Figure 4, mm. 133-140) but not in the other three stanzas (see Figure 4, mm. 141-176) or in the version which is played at half speed. There were, however, familiar elements that evoked the aesthetics of capoeira ladainhas, chief among them, the cadential gesture in certain stanzas, which emphasizes beats three and four of the 4/4 measure (see Figure 4, mm. 148 and 163). Although seasoned singers phrase ladainhas in highly individualized styles, most customarily align with the basic percussion accompaniment, which emphasizes what I have notated as beats 3 and 4 to mark the end of each stanza. Figure 5, for instance, shows the last two verses of the second stanza of “Rei Rumbi dos Palmares,” recorded by Mestre Moraes, one of the most influential singers of the capoeira angola style (Moraes and GCAP Reference Moraes1996). In it, we can see some of his rhythmic idiosyncrasies (e.g., the triplets in m. 3) and his closing gesture that lines up with the percussion in the boxed section of Figure 5. In rehearsals, the capoeiristas did not seem to find the additional eighth note on the upbeat of beat 3 in the closing rhythm of the first stanza (m. 40) awkward or strange, implying that this rhythm departs from the norm within the acceptable limits of the tradition. As shown in Figure 4, the melody passes between different sets of instruments and appears in various textures. Both techniques further remove the melody from its capoeira context, likely diminishing its recognizability to the practitioners. Unlike the latter stanzas, I refrained from employing chromaticism in the first stanza so that I could test how this element affected the identity of ladainhas to the capoeiristas. In this way, I composed various gradients of departure from convention to bake ethnographic questions of melodic recognition into the piece.

Figure 4. Melody of ladainha (mm. 133–176) and first chula (mm. 177–180) played by the big band in “Ladainha” (Mov. I). Only the top voice is shown.Footnote 15

Figure 5. Basic capoeira groove accompanying cadential gesture (boxed) in the second stanza of ladainha “Zumbi Rei dos Palmares” (Moraes, track 1, 0:37-0:44). Actual pitches are about a semitone higher than notated.

Finally, while transferring stylistic concepts from capoeira to the big band, I explored and discarded several possibilities, such as assigning rhythmic figures resembling berimbau toques to the saxophones or to the trombones to function as background riffs. Coincidentally, Orkestra Rumpilezz, the orchestra that eventually became the main case study of my dissertation, successfully implemented this technique for their arrangements, especially transferring parts from the Candomblé percussion ensemble to the various big band sections (Díaz Reference Díaz2014). I became acquainted with them—and decided to study them—a year after completing the Suite Afrobrasileira. My various attempts at this orchestration technique uniquely prepared me to study, understand, and appreciate Rumpilezz’s music. Though not every sketch made it to the final suite, the process developed a kind of analytical musicality and comprehension (an embodied “literature review”) that strongly supported my future ethnomusicological research.

Conversations during rehearsal

The Suíte Afrobrasileira was written largely in solitary with the mentorship of Fred Stride. Based on my experiences studying performance practices of these genres, I was aware that I would need to be flexible in writing for the Afro-Brazilian ensembles and leave room to receive input and collaborate with the musicians during rehearsals. Indeed, rehearsals gave me a unique opportunity to engage in productive dialogue with performers. From this exchange emerged useful insights that I used to reshape the piece and, more relevant for this essay, to deepen my understanding of the music. Considering the composer as researcher, the rehearsal phase is analogous to the final phases in the ethnographic process, for instance, cross-checking whether the research results resonate with and accurately portray the views of interlocutors. The rehearsal process also presents the ideal setting for realizing the kind of horizontal and collaborative relationships that postmodern ethnography encourages between researchers and interlocutors. Specifically, rehearsal exchanges can result in the co-production of texts, a central focus of this project/paper. My focus is precisely on these co-produced texts.

Since the big band was present in every movement of the suite, I scored the five movements using jazz standard notation as shown in Figure 3. This allowed me to manage the orchestration of the different ensembles involved and to have a textual reference to facilitate communication throughout rehearsals. Being oral traditions, capoeira, blocos afro, and Candomblé practitioners need not be familiar with staff notation and often are not. I therefore designed the parts for these ensembles to be memorized during rehearsals, not read from scores as the big band musicians did. I assumed the role of conductor of the Afro-Brazilian ensembles and, supported by score reductions, proceeded to teach the music through demonstration and repetition. Jointly, we adapted from the tradition of samba schools a system of visual cues to mark the precise moments of the transitions or breaks between grooves and to signal changes in tempo and dynamics.

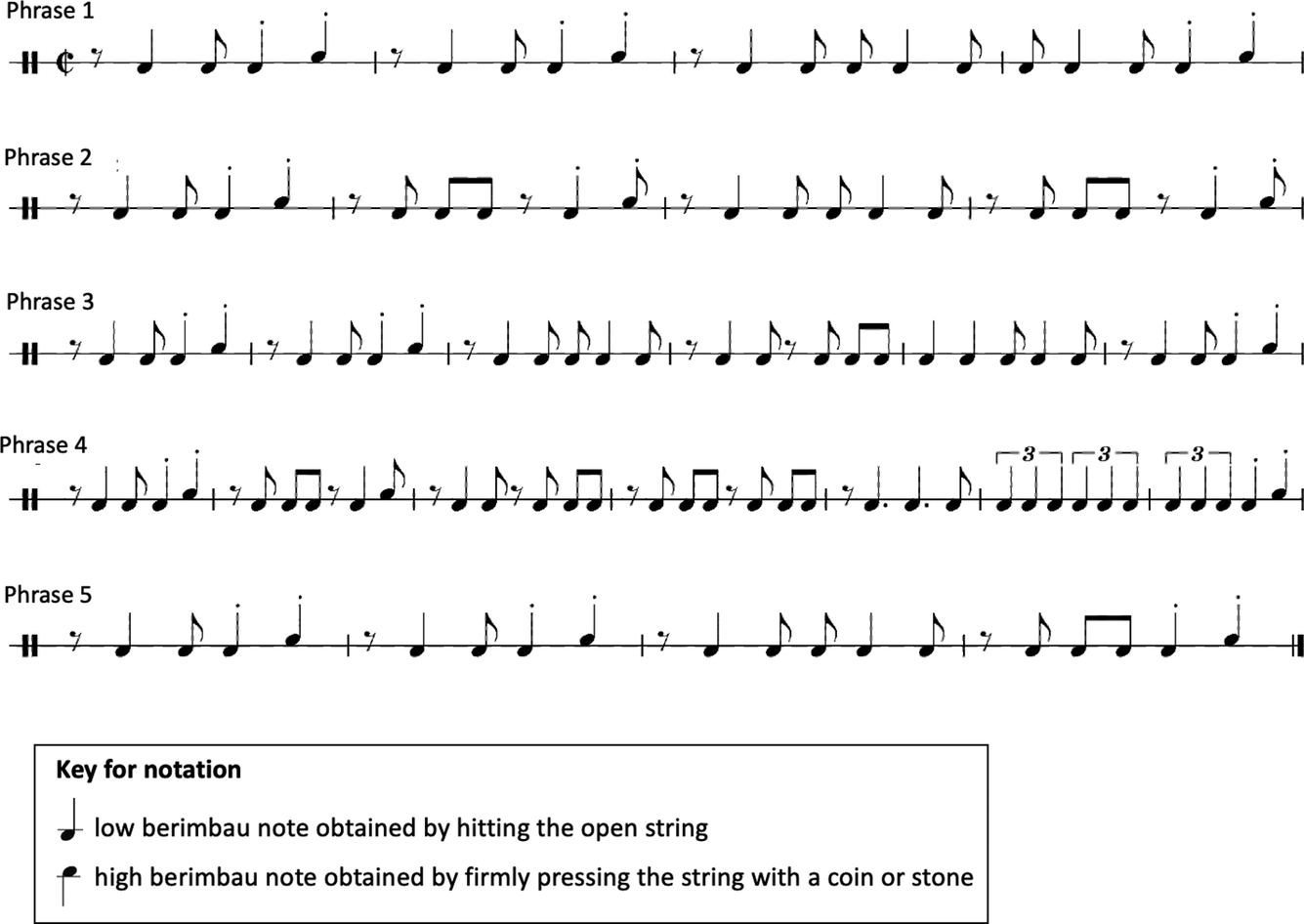

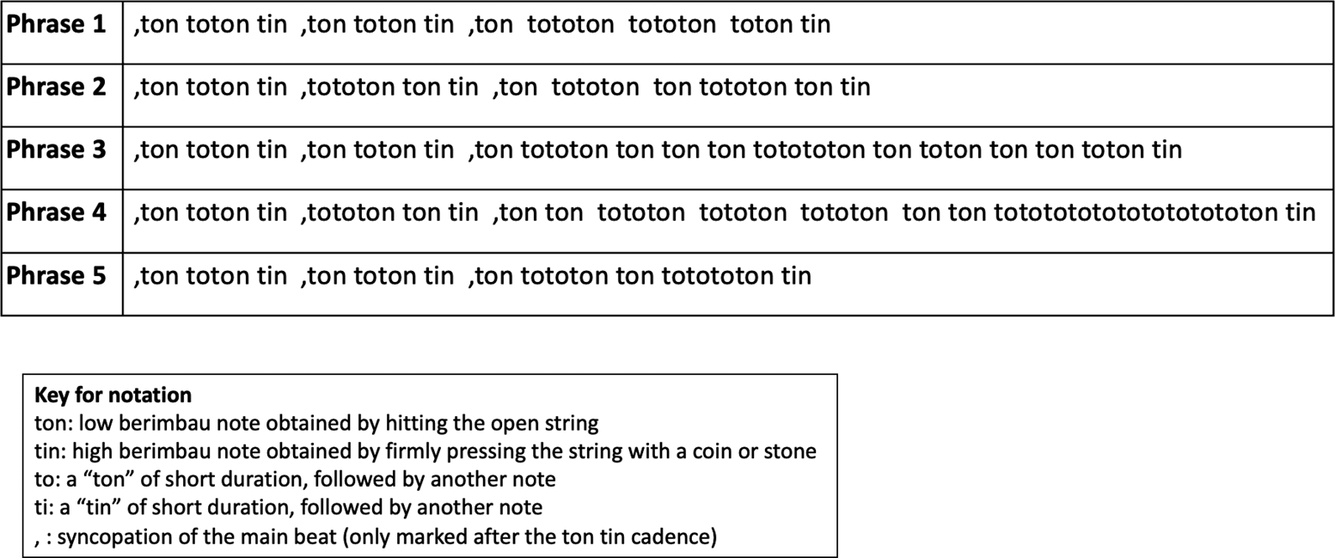

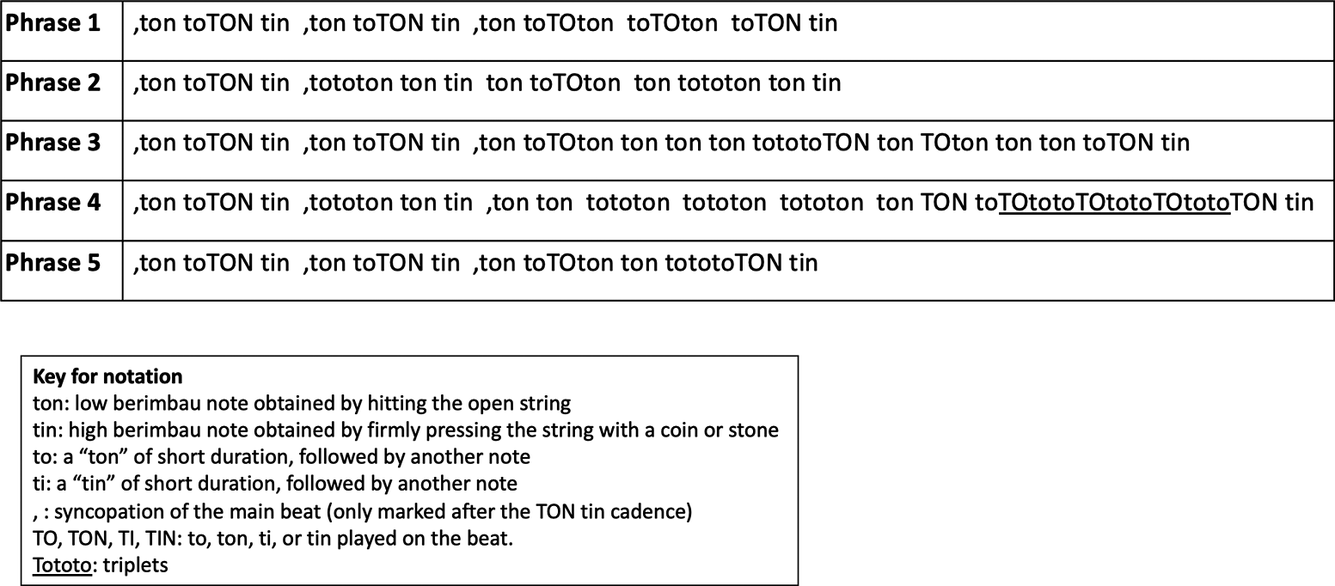

Since the musical passages I wrote for the Afro-Brazilian ensembles were often longer than what many were used to memorizing during rehearsal, I provided audio recordings or MIDI sequences for individual study. Some of the performers used the materials I provided to develop alternative texts to study individually or collectively. Antonia Isa, a member of the capoeira ensemble who had some five years of capoeira experience outside of Brazil, for instance, made a syllabic transcription of the five berimbau phrases in the introduction of “Ladainha.” (For reference, Figure 6 shows this passage as I originally scored it.) In the transcription she showed me first (see Figure 7), Antonia used the syllables “ton” and “tin” to respectively represent the low and high pitches of the berimbau, a comma to indicate certain instances of syncopation, and spaces to group or separate notes according to their duration. Additionally, she dropped the “n” of either “ton” and “tin” when the duration was shorter (e.g., eighth notes). When she tried to perform these phrases from her transcription, I noticed that she struggled to align these rhythms with the underlying pulse and to distinguish between quadruple and triple beat subdivision. Together, we revised her notational system and decided to use capital letters for the notes that fall on the beat and to underline the triplets (see Figure 8). Afterwards, she circulated this transcription among other members of the capoeira ensemble. I cannot say whether this visual aid facilitated memorization or helped the group to understand the rhythms I composed. However, this co-produced text did facilitate conversations with Antonia regarding musical nuance, provide me with insight as to how she (and likely others) understood the music, and gave me tools to help transmit the (paper) rhythms I had composed them for the piece. While some of these phrases were difficult to memorize and perform for the capoeiristas (especially phrases 3 and 4), my consistent inclusion of the customary cadential pattern (emphasizing beats 3 and 4), helped facilitate this process by organizationally clarifying rhythms that they were familiar with.Footnote 16

Figure 6. Five opening phrases of “Ladainha” for berimbau (original score).Footnote 17

Figure 7. Five opening phrases of “Ladainha” (Antonia Isa’s transcription using syllabic notation).

Figure 8. Five opening phrases of “Ladainha” (transcription using a syllabic notation co-created by Antonia Isa and the author).

“Ladainha” rehearsals also presented collaborative opportunities with the choir. Due to difficulties of capturing the timbral and micro-rhythmic nuances of capoeira, samba-reggae, and Candomblé singing in staff notation, I supplemented the scores with recordings of myself singing all the parts accompanied by the guitar (my main instrument), when appropriate. The need to model these stylistic aspects of the singers, many of whom had limited exposure to Afro-Brazilian music and culture, prompted me to implement bi-musicality in the standard sense that ethnomusicologists do: performing the music that we are researching. In this process, I realized that, Footnote to make the songs accessible to these performers, I needed to simplify the phrasing, pitch content, and even rhythms. This could be seen as a process of translation of Afro-Brazilian aesthetics to performers in Vancouver who had varying levels of experience and familiarity with Brazilian music. Significantly, this form of embodied translation affected the final product and helped me understand plausible ways to distil the defining features of these genres.

Finally, rehearsals allowed me to understand the difficulties of playing cross-culturally with varying swing feels. It is a well-known fact that every groove is played with its own microrhythmic particularities (Keil Reference Keil1995; Danielsen Reference Danielsen2010). For instance, the group of UBC students who played in the jazz big band swung the eighth notes to various degrees, at times approximating a 2:1 ratio between the duration of the first and second eighth notes. Conversely, Sambata, the samba group/bloco afro that played in the suite, had developed its own ways of swinging the four subdivisions of the beat, often approximating a long-short medium-long pattern. Due to a lack of time to develop these subtle but complex ways of playing, the capoeira and Candomblé ensembles that I directed and trained tended to play more straight, that is, approximating isochronous beat subdivision. I approached the rehearsal phase knowing these differences and therefore prescribed (both in the score and verbally) degrees of swing, depending on the ensemble pairings. For instance, in “Ladainha,” I wrote “medium swing” or “light swing” when the big band played alone and switched to “straight” when they played with the capoeira ensemble. I did not anticipate how difficult it was for these ensembles to play together. During the first rehearsals, the two groups would invariably get out of sync, with the big band often accelerating and the capoeira group lagging. Things improved when we decided to have two concurrent conductors: Stride led the big band, and I led the capoeira ensemble, following him. Although the problems of micro-rhythm adjustment persisted, we could at least maintain general beat alignment.Footnote 18 This was not the case in “Fechando a roda,” where, despite much rehearsal, the same two ensembles got out of sync at various moments during the premiere.Footnote 19 These issues were equally present in “Samba Estrela” where the big band and bloco afro played together.Footnote 20 Although the final product had many issues, the composition and rehearsal of the suite contributed to my musicality by making me acutely aware of these difficulties in combining ensembles with different swings. Once again, the year after the performance of the suite, I was able to witness how Orkestra Rumpilezz dealt with these same challenges. Having tried and failed with my ensemble not only gave me appreciation for the work of these orchestras but also allowed me to better understand the solutions that director Letieres Leite implemented.

In sum, the rehearsals of the Suíte Afrobrasileira helped me acquire knowledge through what Titon (Reference Titon1995) calls subject shift. My participation in rehearsals was dual: on the one hand, I was able to take some distance as a listener and make assessments as a composer. On the other hand, as a conductor, I was also participating in the creation of the sound by interacting with the musicians. For Titon, in these “moments of transcendental relativity when we become aware of and view ourselves as actors in the world […] we attain a small and momentary degree of objectivity, perhaps the most that our world permits. In those moments, particularly, we learn something valuable about our informant and about ourselves that goes beyond the production of texts and toward understanding” (Titon Reference Titon1995). I am not sure that my subject shift experience gave me the objectivity that Titon wrote about, but it certainly revealed core stylistic features of samba-reggae, capoeira, and Candomblé music. I learned that the governing principle in these genres is to maintain a groove collectively by listening to each other. Repetition of idiomatic patterns is stretched with equally prescribed forms of variation. The grooves are occasionally interrupted by breaks to add variety, interest, and contrast. It is possible but relatively difficult to make subtle changes in dynamics and or tempo because many of these genres are meant to be played outdoors and accompany collective dance. Finally, I learned (the hard way) that combining the swing feel of these genres can be challenging.

Concluding remarks

When I started thinking about composing a suite for big band and Afro-Brazilian music, my goal was to force myself to learn the defining structural elements of the Afro-Bahian genres I wanted to study for my doctoral dissertation in ethnomusicology. In this regard, this composition project exceeded my expectations. Arriving in Bahia in January 2012, I attended a recital by Orkestra Rumpilezz at Teatro Vila Velha in Campo Grande, Salvador. I had already heard about this orchestra on my first 2006 visit to El Salvador, but I still hadn’t had the opportunity to listen to them live. It is difficult to put the experience into words. Apart from the beauty I saw and heard, this orchestra revealed precisely what I was trying to do with the Suíte Afrobrasileira. Maestro Letieres Leite and his musicians had solved many of the issues I had encountered, including a successful micro-rhythmic combination of the big band with Candomblé and carnival percussion, and expanding traditional materials in ways that made them challenging but recognizable to musicians and their audiences. I immediately decided that this was the group I wanted to study for my dissertation. At the end of that concert, I introduced myself to Leite and to Gabriel Guedes (the lead percussionist of the orchestra) and expressed my intention to work with them. They listened to me with curiosity and agreed. During the following six months, I attended all their weekly rehearsals at the Xisto Bahia cultural space in Salvador, five concerts in various parts of the city, and had several conversations with Leite about his compositional method, his motivations, and Afro-Bahian musical aesthetics. With Guedes, I engaged in more typical ethnomusicological work, including weekly lessons in Candomblé music at his house in the Gantois neighbourhood. Rather than the conventional method of taking lessons with Rumpilezz musicians to perform with them,Footnote 21 I intuitively followed Rice’s (Reference Rice1995) approach to bi-musicality of studying and playing with musical materials before engaging interlocutors in the field. The composition, rehearsal, and performance of the suite thoroughly served that purpose—they gave me a pre-understanding of the music that I could not have acquired otherwise. Additionally, by simultaneously observing and conducting during rehearsal, I acquired knowledge through what Titon calls moments of subject shift that intensified my experience and led me to new understandings of the music and its new contexts. In sum, the suite project encouraged me to work with an orchestra performing at a level that felt beyond my technical and analytical abilities and primed me to witness the dense networks of hybridity and identity construction that they mobilized.

According to the late ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl (Reference Nettl2015: 13), doing fieldwork and taking a cross-cultural perspective are two of the markers of ethnomusicology. The Suíte Afrobrasileira is an ethnomusicological document that involved aspects of conventional bi-musicality acquired through fieldwork (the lessons in capoeira, samba-reggae, and Candomblé music I took in Bahia and in other countries before the composition) and, of course, the cross-cultural mixture of musical aesthetics. I have argued that the suite deepened my bi-musicality, not only because of the multiple opportunities it gave me to experiment with musical materials, but also because it forced me into dialogue with performers with diverse levels of familiarity with the genres involved. This challenged me to rethink how I could best transmit my compositional materials, and in the process, better understand the perspectives I was composing from and “translating” to. I believe that these kinds of translations are comparable to those that we do in our academic publications for our non-specialist readers.

Composers who engage in cross-cultural composition are surely aware of and have experienced much of what I have described. My hope with the suite and with this essay is to advocate cross-cultural composition as a tool for ethnomusicological research, specifically as an elaboration on the fieldwork technique of bi-musicality. With its implication of acquiring a second musicality beyond the researcher’s putative musicality, the term bi-musicality clearly falls short in describing the many musicalities that I was able to develop with the suite—musicalities in capoeira, samba-reggae, Candomblé, funk, and jazz. Admittedly clunky, the expression compositional poly-musicality may more appropriately describe the approach I am proposing here. Finally, I hope that the Suíte Afrobrasileira, as an ethnographic text, enters into productive dialogue with scholars, listeners, musicians—Brazilians, or otherwise—and with cross-cultural musical projects involving Afro-Brazilian musics such as Abigail Moura’s Orquestra Afrobrasileira, Bira Marques’ Orquestra Afrosinfônica, Gabi Guedes’s Pradarrum, and many others.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Fred Stride and all the musicians who participated in the rehearsal and performance of the Suíte Afrobrasileira at UBC in 2011—including the UBC Jazz ensemble, the UBC Capoeira Angola Study Group, and Sambata. I also thank Paul Engle for copy-editing this essay and the two peer reviewers for their insightful feedback.

Appendix 1: Basic information of the Suíte Afrobrasileira (composed in 2010, premiered in 2011)