Introduction

Although penicillin allergy is frequently reported in about 10% in the general population, 90% of these reported allergies are not true allergies based on penicillin skin testing. Reference Luintel, Healy, Blank, Luintel, Dryden and Das1–Reference Trubiano, Adkinson and Phillips5 Many of these allergies are misinterpreted as they typically originate from childhood, persist and remain unverified, and may be the result of side effects or infectious symptoms as opposed to true allergic reactions. Reference Blumenthal, Peter, Trubiano and Phillips6 Moreover, true IgE-mediated penicillin allergies can often diminish over time. Reference Blanca, Torres, García, Romano, Mayorga and de Ramon7 Mislabeled penicillin allergies contribute to longer hospital stays, increased adverse effects and increased infection rates with alternative antibiotics (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridioides difficile), and greater healthcare costs. Reference Macy and Contreras8–Reference Blumenthal, Lu, Zhang, Li, Walensky and Choi13 These outcomes are particularly concerning for the elderly, whom up to 16% have penicillin allergies and are more vulnerable to infections and adverse drug reactions. Reference Gillespie, Sitter, McConeghy, Strymish, Gupta and Hartmann14–Reference Walker and Wynne17

To mitigate the negative impact of erroneous penicillin allergy labels, initiatives are needed to assess and de-label these allergies. The PEN-FAST tool, a validated scoring system, can stratify adult patients by penicillin allergy risk (ie, the risk of having a positive penicillin allergy test). Reference Trubiano, Vogrin, Chua, Bourke, Yun and Douglas18 Patients deemed “low-risk” may safely undergo a direct oral penicillin challenge without resource-intensive skin testing. Reference Copaescu, Vogrin, James, Chua, Rose and De Luca19 While this approach has been implemented in various settings such as emergency departments, allergy clinics, preoperative clinics, intensive care units, and Veteran Affairs populations, this approach remains underutilized in hospitalized older adults. Reference Gillespie, Sitter, McConeghy, Strymish, Gupta and Hartmann14,Reference Mill, Primeau, Medoff, Lejtenyi, O’Keefe and Netchiporouk20–Reference Accarino, Ramsey, Samarakoon, Phillips, Gonzalez-Estrada and Otani27

In Spring 2024, Burnaby Hospital launched a pharmacy-driven interdisciplinary penicillin allergy de-labeling quality improvement initiative in the Acute Care for Elderly (ACE) Unit. The ACE unit primarily provides care to older adults with multiple medical conditions. 28 Prior to this initiative, there was no formal penicillin allergy assessment program in place. We conducted a quality improvement study to assess the feasibility, safety, and challenges of implementing this initiative in the ACE Unit.

Methods

Allergy screening and de-labeling initiative

This pilot initiative was conducted at a large community university-affiliated hospital with around 300 beds in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. 29,30 The hospital has infectious diseases physician and antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) teams working on site. The hospital does not have access to on-site allergy and immunology staff.

The penicillin allergy assessment process begins with the clinical pharmacy support technician (CPST) using electronic medical record (EMR) on weekdays to identify patients with a documented penicillin allergy. The CPST collaborated with ward and AMS clinical pharmacists to interview patients and gather detailed allergy histories using a locally developed standardized work-up form (Supplementary Material 1). Clinical pharmacists reviewed these patients. Piperacillin-tazobactam allergy patients were excluded from the de-labelling initiative.

If information gathering alone was sufficient for de-labeling (ie, reaction was intolerance, or low-risk patient had PEN-FAST score of 0 or 1 with subsequent penicillin tolerance history (not based on piperacillin-tazobactam tolerance alone)), the patient was de-labeled, educated, and allergy records were updated accordingly.

For patients with a PEN-FAST score of 0 or 1 and no contraindications to oral penicillin challenge (Supplementary Material 1), the patient’s medical and pharmacy team offered a single 500 mg dose of oral amoxicillin. Oral penicillin challenge was not pursued for patients with poor prognosis or if it did not align with their goals of care. Patients with higher-risk histories who did not qualify for de-labeling (eg, multiple or recurrent allergic reactions) were referred to an allergist for outpatient follow-up. Prior to each penicillin challenge procedure, patient consent was obtained and the health authority protocol was used. If patients had received antihistamines in the last 5 days, or beta-blockers on the morning of challenge, oral penicillin challenge was rescheduled. Vital signs were monitored by nursing staff pre-challenge and every 30 minutes for at least 1 hour after oral challenge. If no reaction occurred, patients were de-labeled, counseled, and their allergy records were updated as having tolerated the penicillin challenge. After 4 weeks, the pharmacist followed up with the patient to check for any delayed reactions and to inquire about any antimicrobial use. Any new reactions deemed to be an allergic reaction led to reclassification of the allergy records.

Study design, approval and eligibility criteria

This quality improvement study involved a retrospective chart review of patients assessed during the penicillin allergy de-labeling pilot initiative, and a post-implementation staff survey. The quality improvement study was granted research ethics board review exemption and survey review from the health authority research ethics board. Patients aged 65 years and older and admitted to the ACE Unit between March 25, 2024 and April 17, 2025 were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had been discharged prior to full allergy assessment or had piperacillin-tazobactam allergy.

Survey

A post-implementation survey, adapted from the Theoretical Domains Framework, was distributed by the ward pharmacist to ACE Unit staff including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, nurses, and physicians from December 2024 to January 2025. Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie31–Reference Atkins, Francis, Islam, O’Connor, Patey and Ivers35 Paper and electronic forms were made available for staff to complete anonymously. Survey items included themes consistent with previously identified barriers to practice change in healthcare such as knowledge, skills, social and professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, motivation, and environmental context and resources. Demographic questions, Likert scale, multiple choice, and open-ended question formats were utilized (Supplementary Material 2).

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the proportion of eligible patients whose penicillin allergies were de-labeled. We also investigated the following secondary outcomes: method of de-labeling (ie, information gathering alone or oral penicillin challenge), immediate and delayed reactions, beta-lactam use within 4 weeks, guideline-discordant broad-spectrum antibiotic use within 4 weeks, allergy record updates, and healthcare staff reported barriers to this initiative.

Data collection

To collect data, we used the EMR and pharmacy penicillin allergy work-up form (Supplementary Material 1). Characteristics include age, sex, comorbidities, length of hospital stay, whether they had an infection during admission, and pertinent details of their index penicillin reaction or drug allergy history. Penicillin allergy history details include the type of penicillin antibiotic the patient experienced a reaction to, how long ago the reaction occurred, signs and symptoms experienced, time to reaction following administration, whether the penicillin was stopped, whether treatment was required, whether the patient tried the same or another penicillin antibiotic after the reaction, and whether they had previous penicillin skin testing done. PEN-FAST scores were also calculated. Baseline characteristics of survey respondents including profession, years of practice, and reported barriers to implementation were collected (Supplementary Material 2).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel (Version 2402). Frequencies were reported for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated for continuous variables.

Results

From March 25, 2024 to April 17, 2025, a total of 1,394 patients were admitted to the ACE Unit. Of these, 121 patients (8.7%) had a penicillin allergy. Out of 105 patients screened during weekday working hours, a total of 87 patients met study inclusion. Reasons for exclusion included early discharge, age less than 65 years, and piperacillin-tazobactam allergy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients included in the study. aAccording to PEN-FAST score of 0 or 1, predefined criteria, and providers’ clinical judgment. bPatient tolerated oral amoxicillin challenge and was subsequently transitioned to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate but experienced a delayed reaction (rib cage tightness, pain upon breathing, coughing, itchy rash on back) after 7 days of treatment. Rib cage tightness/pain resolved after 2 doses of antihistamine and itchy rash on back resolved after 1 week of antihistamines.

Characteristics of included patients

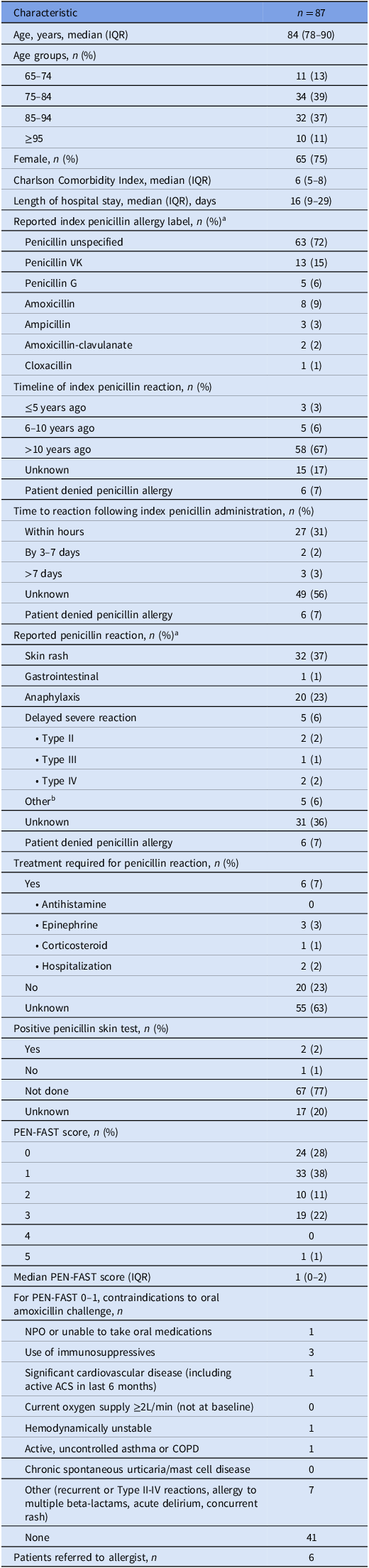

Baseline patient demographics are outlined in Table 1. The median age was 84 years (IQR 78–90) with the majority being female (75%). The median Charlson Comorbidity Index was 6 (IQR 5–8). Unspecified penicillin allergies (72%) accounted for most reported penicillin allergies, followed by penicillin VK (15%) and amoxicillin (9%). The most frequently reported reaction to penicillin was rash (37%). Most reactions were reported to have occurred greater than 10 years ago (67%). The median PEN-FAST score for these patients was 1 (IQR 0–2), with 34% of study patients having a PEN-FAST score of 2 or more.

Table 1. Patient baseline characteristics

See (Supplementary Material 3) for additional baseline characteristics

NPO - nothing by mouth; ACS—acute coronary syndrome; COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

a Percentages may add up to greater than 100% as patients may have had more than one allergy or reaction listed.

b Reported reactions: “fainting”, “tingling, cold feeling”, and “high fever up to 42°C with hallucinations”.

Penicillin allergy de-labeling

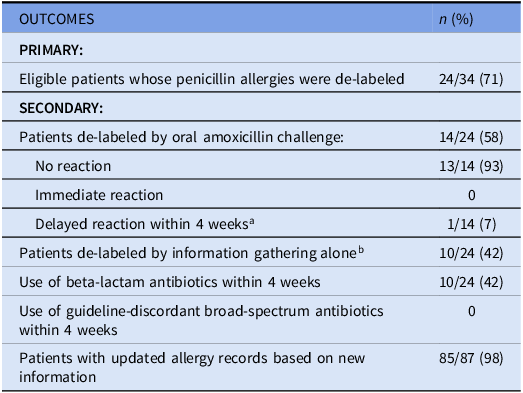

Thirty-four of the 87 included study patients (39%) were deemed eligible for penicillin allergy de-labeling based on PEN-FAST score, clinical judgment, and without contraindications to oral challenge (Figure 1). Of the eligible patients, five patients declined consent and five patients were discharged prior to obtaining consent. The remaining patients were de-labeled (24 of 34, 71%) (Table 2).

Of the 24 eligible patients who were de-labeled, the de-labeling method was based on history (n = 10; 42%) or oral amoxicillin challenge (n = 14; 58%). No immediate reactions were reported post-challenge. One patient reported developing a delayed reaction after 7 days. The patient had rib cage tightness, pain upon breathing, and coughing without shortness of breath which led to discontinuation of the antibiotic. On the eighth day, the patient developed an extensive itchy rash on their back. The rib cage tightness and pain resolved after 2 doses of diphenhydramine and the itchy rash on the back resolved after 1 week of diphenhydramine. The patient’s family physician and community pharmacy were notified, and the patient’s allergy records were reverted to having a penicillin allergy with reaction details.

Among the patients who received de-labeling, 42% of patients received beta-lactam antibiotics within 4 weeks. No patients received guideline-discordant broad-spectrum antibiotics within 4 weeks.

Allergy record updates

Eighty-five of 87 patients (98%) had their local health authority allergy records updated during this initiative, while 2 patients did not have any new information to add to their existing record. When applicable, requests were submitted to update provincial, outpatient pharmacy, and family physician clinic allergy records.

Survey to ACE unit staff

For the post-implementation survey, there were a total of 20 respondents consisting of clinical pharmacists (n = 5), pharmacy technicians (n = 3), physicians (n = 5), and nurses (n = 7). 65% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that lack of time was a barrier to implementation. Similarly, 60% and 50% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that patient-related factors such as clinical status/prognosis and staffing constraints, respectively, were other barriers (Figure 2). Fear of harm to patient, technological barriers, and insufficient training or education as barriers were less frequently reported (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Survey results: ACE unit staff-reported barriers to penicillin allergy de-labeling (n = 20 respondents).

Table 2. Outcomes

a Skin reaction with rib cage tightness and coughing after 7 days.

b Prior penicillin tolerance or reaction was intolerance (e.g. nausea, vomiting, etc.).

Discussion

While penicillin allergy de-labeling has been done in various settings, data on elderly populations remain limited. Our pilot quality improvement study contributes to this gap in literature by specifically focusing on hospitalized elderly patients, who often have complex medical histories and a higher burden of antibiotic use. Our study population had a median age of 84 years, with a median Charlson Comorbidity Index of 6, indicating a high burden of chronic disease. In contrast, a number of previous de-labeling studies have either excluded patients aged 70 and older or included younger cohorts with lower comorbidity burdens. Reference Gillespie, Sitter, McConeghy, Strymish, Gupta and Hartmann14,Reference Copaescu, Vogrin, James, Chua, Rose and De Luca19,Reference Chua, Vogrin, Bury, Douglas, Holmes and Tan22,Reference Arasaratnam, Guastadisegni, Kouma, Maxwell, Yang and Storey24,Reference Du Plessis, Walls, Jordan and Holland25,Reference Accarino, Ramsey, Samarakoon, Phillips, Gonzalez-Estrada and Otani27,Reference Alagoz, Saucke, Balasubramanian, Lata, Liebenstein and Kakumanu36 Furthermore, previous studies have not fully implemented comprehensive allergy assessments in a comorbid inpatient elderly population. Reference Gillespie, Sitter, McConeghy, Strymish, Gupta and Hartmann14,Reference Du Plessis, Walls, Jordan and Holland25,Reference Accarino, Ramsey, Samarakoon, Phillips, Gonzalez-Estrada and Otani27,Reference Alagoz, Saucke, Balasubramanian, Lata, Liebenstein and Kakumanu36 A penicillin allergy de-labeling program implemented in Australia reported a 62% de-labeling rate for patients with a low-risk penicillin allergy, though this cohort had a lower median Charlson Comorbidity Index of 4 and a median age of 66. Reference Chua, Vogrin, Bury, Douglas, Holmes and Tan22 Similarly, the Veterans Affairs study population had a median age of 67 and a median Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 4. Reference Arasaratnam, Guastadisegni, Kouma, Maxwell, Yang and Storey24 One study from the United States Drug Allergy Registry (USDAR) did apply allergy assessments to adults aged 65 years and up, but they report a mean age of 72, and the population in this registry was relatively healthy, without significant need for antibiotics. Reference Accarino, Ramsey, Samarakoon, Phillips, Gonzalez-Estrada and Otani27 Similarly, the PALACE trial demonstrated the feasibility of direct oral amoxicillin challenge in low-risk adult patients who were relatively younger than our study population. Reference Copaescu, Vogrin, James, Chua, Rose and De Luca19

Our initiative determined eligibility based on available clinical data and guidelines, and incorporated the PEN-FAST tool. Reference Trubiano, Vogrin, Chua, Bourke, Yun and Douglas18,Reference Copaescu, Vogrin, James, Chua, Rose and De Luca19,37,38 While past research has characterized patients with a PEN-FAST score of ≤2 as low-risk in a large international randomized clinical trial, most penicillin challenge patients in the cohort had lower PEN-FAST scores of 0 or 1. Reference Copaescu, Vogrin, James, Chua, Rose and De Luca19 As such, we opted for a more cautious de-labeling approach using a cut-off PEN-FAST score of 0–1 to balance safety for our elderly study population. In terms of outcomes, our de-labeling rate of 71% is comparable to previous studies, though our strict eligibility criteria may have contributed to a slightly lower de-labeling rate than some published reports. Reference Du Plessis, Walls, Jordan and Holland25 Ineligibilities to penicillin challenge included severe, recurrent, or multiple beta-lactam allergic reactions, unstable or poor clinical status, and concomitant use of immunosuppressive medications. Despite this, the safety of our approach was reinforced by the absence of immediate reactions and only one transient case of delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

It is important to note that piperacillin-tazobactam may express a distinct allergic phenotype compared to other penicillin or beta-lactam antibiotics. Reference Gallardo, Moreno, Laffond, Muñoz-Bellido, Gracia-Bara and Macias39,Reference Casimir-Brown, Kennard, Kayode, Siew, Makris and Tsilochristou40 In some cases, individuals exhibit selective hypersensitivity reactions to piperacillin-tazobactam despite tolerating other penicillins. Given the limited evidence on penicillin allergy de-labeling in the elderly population, we excluded those with a documented piperacillin-tazobactam allergy from our study. Future studies may further explore piperacillin-tazobactam allergy phenotypes and cross-reactivity potential with other penicillins.

Our de-labeling efforts had positive implications for antimicrobial stewardship efforts, as 42% of de-labeled patients subsequently received beta-lactams, reducing reliance on guideline-discordant broad-spectrum antibiotics. These findings further support the integration of penicillin allergy assessments and de-labeling into routine care, especially in elderly patients who may have more frequent and prolonged hospitalization and infection risk.

The most frequently reported barriers by healthcare staff to implementation of this initiative were lack of time, patient complexity, and staffing constraints. Using our approach, standardized allergy assessment and oral challenge protocols may help with implementation efficiency. Further work is needed to address these concerns to ensure sustainability of penicillin allergy assessment and de-labeling programs.

Limitations of this study include its single-unit design, retrospective chart review, potential survey response bias. Additionally, we had limited access to outpatient antibiotic records for some patients after de-labeling. However, this likely would have been mitigated by the fact that all patients who were de-labeled with oral challenge were followed up by the clinical pharmacist after 4 weeks and were asked about any antibiotic use. Also, many de-labeled patients were still admitted in hospital 4 weeks following de-labeling so access to medication records would not have been a concern. Despite these limitations, our study was based on a comprehensive initiative utilizing information from patients, outpatient providers, health authority medical records, along with sufficient follow-up.

In summary, our quality improvement study highlights an effective and safe method to de-labeling penicillin allergies in a highly comorbid, elderly, inpatient population. By incorporating appropriate patient selection criteria (including PEN-FAST 0–1) and a structured approach, we provide a foundation for expanding penicillin allergy de-labeling protocols for older adults in similar hospital settings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2025.10279.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Burnaby Hospital Pharmacy Team (including CPSTs: Cheryl Wong, Evelyn Tien, Andrea Shimizu, Mahima Saini), Infectious Diseases Physicians (including Dr. Jennifer Losie), Hospitalist Physicians, Nursing Staff, and Pharmacy Information Systems team for their support in this quality improvement initiative.

Financial support

None reported.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.