Introduction

Structural economic change resulting from globalisation, deindustrialisation and technological change, further to their consequences for labour markets and political behaviour, have received significant scholarly attention in recent years. More specifically, there has been a lot of research on how the losers of the aforementioned transformations tend to turn towards populist and extremist parties, as going hand in hand with a decline in support for mainstream parties (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Dorn, Hanson and Majlesi2020; Baccini & Weymouth, Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021; Broz et al., Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021; Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018a; Gallego & Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018; Walter, Reference Walter2021). A large part of the literature attributes this political backlash to the absence of targeted and effective government compensation for those negatively affected by globalisation and technological change as well as to the failure to include the interests of affected groups in both the negotiation and policy‐making process (Broz et al., Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021; Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018a; Gallego & Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018). The implication hereof is that the existence of such compensation schemes might help mitigate any such political backlash.

However, despite its envisaged relevance over the upcoming decades, only a few contributions have analysed the empirical effectiveness of compensation in light of structural economic change and even less so due to the green transition. While some research on the losers of globalisation finds that compensation is effective in attenuating electoral backlash (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b; Margalit, Reference Margalit2011; Rickard, Reference Rickard2023), this has not been corroborated for the case of workers at risk of automation, where such compensation does not seem to have a moderating effect (Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019). In the context of the green transition, there have been some studies using aggregate data on the electoral consequences of the decline of the coal industry in the United States, documenting a conservative backlash there in the absence of government compensation (Egli et al., Reference Egli, Schmid and Schmidt2022; Gazmararian, Reference Gazmararian2024), and in Spain, where a just transition agreement led to electoral gains for the incumbent party in the subsequent election (Bolet et al., Reference Bolet, Green and González‐Eguino2024).

Adding to this growing literature on the electoral effects of coal phase‐outs, I argue that the reasons for political backlash to structural economic change go beyond factors such as the presence of compensation schemes or the involvement of affected groups in the policy‐making process. Instead, I posit that even in the presence of compensation mechanisms, affected communities still perceive themselves to suffer a loss of income and that these harboured economic grievances fuel their political disengagement and protest voting in the form of higher abstention rates. Moreover, I contend that these grievances lead affected communities to asymmetrically punish those parties with close ties to unions and workers in the affected industries – namely, the ones whom they identify as the issue owners vis‐à‐vis the policy causing said decline.

I test my argument with the case of the government‐induced phasing out of coal in Germany after 2007. Following the literature on political backlash due to structural economic change, Germany is a useful case to study this as the existence of compensation schemes and interest‐group representation makes it a least‐likely case to observe an electoral backlash to the decline of the coal industry (Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg, Denzin and Lincoln2011; Levy, Reference Levy2008). First, the German coal phase‐out has been accompanied by targeted compensation for affected workers (in the form of early‐retirement and retraining opportunities) as well as support schemes for affected regions (Diluiso et al., Reference Diluiso, Walk, Manych, Cerutti, Chipiga, Workman and Ayas2021), ones more generous than those in other countries phasing out coal (Gürtler & Herberg, Reference Gürtler and Herberg2023). Second, Germany is characterised by a corporatist system of interest group intermediation, in which carbon‐polluting economic factors such as carbon business interests are strongly involved in the policy‐making process (Jahn, Reference Jahn2016; Mildenberger, Reference Mildenberger2020). In contrast to pluralist systems reliant on coal, such as the United Kingdom or the United States, an electoral backlash should be less likely to occur as reform proponents need to collaborate with the losers of policy change, which favours the latter's eventual compensation (Finnegan, Reference Finnegan2022; Mildenberger, Reference Mildenberger2020). This corporatist element to the German political economy is clearly visible in the 2007 phase‐out law, given the generally high involvement of coal workers in the decision‐making of coal operating companies.

In addition to these factors potentially attenuating electoral backlash, another distinct feature of the German case is that its largest far‐right party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany), was only founded in 2013. Thus, the regional elections of 2017 were the first in which it competed. The German case also allows us to test, then, what form of protest voting might occur in the absence of a strong far‐right party.

For my empirical analysis, I use an own original dataset which contains information on the location and date of coal closures, that is, the closure of coal‐fired power plants (CFPPs) and coal mines, between 2007 and 2022. It also encompasses municipal (Gemeinde)‐level data on regional, federal and local election results in North Rhine‐Westphalia (NRW) between 2000 and 2022. I estimate the effect of the first coal closure per municipality on voting behaviour using staggered difference‐in‐differences (DiD) models. I find strong support for an association of coal closures between 2007 and 2022 with asymmetric backlash: concretely, via a negative effect on vote shares for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and a positive effect on abstention rates in affected municipalities. Moreover, I provide indicative evidence for the underlying mechanisms at work here and show that the results are robust to different sample specifications and the testing of alternative explanations.

Providing the first empirical analysis of electoral backlash to a green transition policy in an explicitly least‐likely context, these findings suggest that the typical prescriptions of large parts of the literature may not be sufficient to prevent negative political consequences in the face of structural economic change. Instead, my findings point to an asymmetric punishment of the party regarded as the issue owner as well as to the importance of factors such as perceived material deprivation and disappointment. With the high salience and politicisation of and around the issue of fossil fuel‐based energy generation, these findings have important implications for pending coal phase‐outs worldwide.

Theoretical discussion

Despite its certain relevance over the upcoming decades, the green transition as a source of structural economic transformation in advanced capitalist economies has only received limited scholarly attention so far. A first cluster of contributions has examined the link between climate policy outcomes, such as wind turbine construction, and electoral behaviour in different countries, with mixed findings to date (Otteni & Weisskircher, Reference Otteni and Weisskircher2022; Stokes, Reference Stokes2015; Urpelainen & Zhang, Reference Urpelainen and Zhang2022). Second, a nascent strand of the literature has examined the electoral consequences of the decline of the coal industry in the United States – therewith documenting how job losses in the coal sector led to an increase in the vote share of the Republican Party (Egli et al., Reference Egli, Schmid and Schmidt2022; Gazmararian, Reference Gazmararian2024) – and in Spain – where the adoption of a just transition agreement on phasing out coal led to electoral gains for the incumbent party in the subsequent election (Bolet et al., Reference Bolet, Green and González‐Eguino2024).

However, whether the presence and the design of compensation measures for groups negatively affected by structural economic change have the potential to attenuate possible electoral backlash remains a somewhat open question. Some studies point to such an effect when it comes to compensating the losers of globalisation (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b; Margalit, Reference Margalit2011) and individuals negatively affected by a ban on high‐polluting cars (Colantone et al., Reference Colantone, Di Lonardo, Margalit and Percoco2024). However, in the context of workers subject to the risk of automation, Gingrich (Reference Gingrich2019) paints a more pessimistic picture by providing evidence that compensation does not reduce ballots cast for populist parties. Finally, only the two contributions authored by Gaikwad et al. (Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022) and Bolet et al. (Reference Bolet, Green and González‐Eguino2024), respectively, have touched on the role of compensation in the context of the green transition, with the former only capturing preferences rather than actual policies and the latter only analysing the effect of the announcement and not the actual implementation of a green transition policy.

Before delving into the article's theoretical expectations, it is necessary to clarify the level of analysis: namely, that of the municipal level. The theoretical mechanism underpinning my argument operates on the individual level, as this is the level of analysis that the literature which informs these theoretical priors is based on. However, I expect coal closures to yield an impact particularly on the aggregate, municipal level. This is because such closures not only influence the behaviour of immediately affected persons (such as those working in mines, plants and coal‐reliant industries) but are also likely to spill over to individuals in their wider communities. This is in line with previous research highlighting that coal industries serve as the basis for a shared identity among communities situated in coal‐producing areas (Bell & Braun, Reference Bell and Braun2010; Carley et al., Reference Carley, Evans and Konisky2018; Mayer, Reference Mayer2018). As such, the ‘community‐level is essential’ (Gazmararian, Reference Gazmararian2024, p. 1) when analysing the electoral repercussions of coal closures. This is further corroborated by survey evidence collected by Gaikwad et al. (Reference Gaikwad, Genovese and Tingley2022) in India and the United States showing that individuals in coal‐producing areas have a strong preference for community‐level over individual‐level compensation, which the authors link back to a shared identity.

Returning to the main research question: How should coal closures affect voting behaviour? First of all, the above‐mentioned literature on political backlash induced by structural economic change would expect that individuals in municipalities affected by a coal closure voice their discontent by turning to a far‐right party (Autor et al., Reference Autor, Dorn, Hanson and Majlesi2020; Baccini & Weymouth, Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021; Broz et al., Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021; Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018a; Gallego & Kurer, Reference Gallego and Kurer2022; Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2019; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2018; Walter, Reference Walter2021). Despite the existence of government compensation in the form of early‐retirement benefits for those employed in the mines and plants as well as investment in regional infrastructure, coal closures arguably still represent a net loss of income for workers. Moreover, those in downstream industries dependent on coal, such as iron and steel, are indirectly affected by this economic shock without benefiting from targeted compensation. Overall, coal closures are thus expected to still trigger economic grievances among individuals in affected municipalities compared to peers in unaffected municipalities, even in the presence of compensation schemes.

Past research has linked relative economic grievances to support for populist and extremist parties (Burgoon et al., Reference Burgoon, Noort, Rooduijn and Underhill2019; Engler & Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021). This is corroborated by Gidron & Hall (Reference Gidron and Hall2020), who show that feelings of social marginalisation are associated with greater support for radical parties. In addition, there is a growing literature focussing on place‐based explanations of support for the far right, such as declining regions, urban development and local rent levels, which also centre around the theme of relative local deprivation (Bolet, Reference Bolet2021; Held & Patana, Reference Held and Patana2023; Patana, Reference Patana2022). This arguably applies to the case of coal municipalities, where impacted individuals are very likely to experience positional deprivation or social marginalisation due to relative economic grievances.

Moreover, recent contributions to the literature have linked feelings of a loss of social status to far‐right voting (Engler & Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021; Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017), potentially applying to coal communities as well. Over the course of many years, coal workers became endowed with high social status and a distinct community identity would form in related areas (Carley et al., Reference Carley, Evans and Konisky2018; Diluiso et al., Reference Diluiso, Walk, Manych, Cerutti, Chipiga, Workman and Ayas2021; Mayer, Reference Mayer2022). This was especially the case in Germany, where the historical strength of the coal industry can be seen as the starting point for European integration after the Second World War and the foundation of the country's current prosperity (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018). The loss of this social status induced by coal closures is expected, then, to contribute to feelings of status decline.

Regarding the losers of structural change in the labour market, the link between relative status anxiety and voting for populist far‐right parties has already been established for workers threatened by automation (Kurer, Reference Kurer2020). Yet, this is even more plausible for those employed in the coal sector due to the aforementioned high social status with which the industry had long been associated. This might make municipalities which experienced coal closures more receptive to the AfD's populist appeals and to its socially conservative and nostalgic propositions. Moreover, the AfD is the only party to still campaign against the phasing out of coal in Germany, both at the state level in NRW as well as federally (AfD, 2021; AfD NRW, 2022). This gives disappointed communities, especially those fearing that the coal phase‐out will trigger a loss of social status, not only a symbolic but also substantive reason to vote for the AfD to voice their discontent with the coal closures.

Hypothesis 1: A coal closure is associated with a higher vote share for the far‐right AfD in the affected municipality.

Another channel through which one's perceived structural economic disadvantage relative to other people's has been shown to affect voting behaviour is by undermining political participation, in particular among those from disadvantaged social groups (Kurer et al., Reference Kurer, Häusermann, Wüest and Enggist2019; Schwander et al., Reference Schwander, Gohla and Schäfer2020; Solt, Reference Solt2008). This has indeed been found to be the case in Germany (Schäfer & Schwander, Reference Schäfer and Schwander2019; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Schwander, Manow, Schoen and Weßels2016). While other scholars highlight that economic hardship can also lead to increased political participation (Margalit, Reference Margalit2019; Pontusson & Rueda, Reference Pontusson and Rueda2010), Kurer's (Reference Kurer2020) findings regarding the effect of routinisation on political participation rather speak in favour of the political demobilisation of those negatively affected by structural economic change; specifically, he comes to the conclusion that people exiting the labour market due to structural economic change tend to subsequently abstain from voting. Even though not directly testable due to a lack of individual‐level data, it thus seems plausible that those heading into early retirement because of the managed decline of the coal industry should, in consequence, exhibit lower levels of political engagement in the form of reduced electoral turnout (Solt, Reference Solt2008). For these reasons, I expect coal closures to lead to higher abstention rates in affected municipalities compared to those not seeing such closures.

Moreover, abstaining from voting has also been linked to ‘send[ing] a signal of disapproval with a party, government or institution’ (Hobolt & Spoon, Reference Hobolt and Spoon2012, p. 2). Therefore, voting for the AfD or similar aside, I expect communities affected by coal closures to voice their grievances through political disengagement in the form of abstention. While the 2017 regional elections were, as noted, the first in which the newly formed AfD competed, I assume abstention and voting for this party to stem from dynamics not wholly dependent on each other. In other words, I do not expect individuals harbouring economic grievances to immediately switch from abstaining to voting for a far‐right party on its creation. For NRW, existing studies have found that in the 2017 regional elections, the AfD attracted voters mainly from other parties and not primarily non‐voters (Haußner & Leininger, Reference Haußner and Leininger2018); the picture was reversed in 2022 meanwhile, with a large number of its erstwhile voters now choosing to abstain (Bajohr, Reference Bajohr2022). Therefore, I rather expect the two channels to operate independently from one another time‐wise.

Hypothesis 2: A coal closure is associated with a higher abstention rate in the affected municipality.

Apart from these two general hypotheses on electoral backlash in the face of coal closures, a third hypothesis more specific to the German case is that such events might lead to affected communities punishing the SPD, which was not only the issue owner of the topic of coal‐fired energy politics but also a long‐standing political ally of coal workers. In line with the conceptualisation of an ‘issue owner’ as the party associated with a specific topic (Budge, Reference Budge2015; Budge & Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983), the SPD can be regarded as the party which had always represented the interests of coal workers. Not only were many of the latter party members, but also the influential trade union IG BCE, which represented coal workers, had close ties to the SPD, allowing these individuals to wield considerable political influence (Renn & Marshall, Reference Renn and Marshall2016). For instance, ‘[German mineworkers’ leaders] regularly became members of the Federal and State parliaments, even as energy spokesmen for the SPD’ (Rentier et al., Reference Rentier, Lelieveldt and Kramer2019, p. 624). However, because of these strong ties historically between coal workers and the SPD, it was the latter's base which lost out most from this policy in terms of both income and social status. Thus, as the SPD in NRW was not successful in averting the phasing out of coal (which it advocated for together with the IG BCE and the main coal operator) (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009), the actual closures might arguably have triggered feelings of betrayal and disappointment with the Social Democrats among those living in affected municipalities due to their disapproval of the policy.

This specific disillusionment with the issue‐owning party regarding the coal phase‐out ties in with a general trend of social‐democratic parties in Europe having become alienated from their erstwhile core constituency, the working class, in favour of a more educated middle class (Abou‐Chadi & Wagner, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Wagner2020; Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). This is also the case in Germany (Schwander & Manow, Reference Schwander and Manow2017; Schwander et al., Reference Schwander, Gohla and Schäfer2020): coal workers were the prototype of the traditional working class whose interests the SPD represented for so long. Since NRW was for decades the latter party's stronghold – between 1966 and 2005, the NRW government was led without interruption by the SPD – (Neumann, Reference Neumann and Neumann2012), this alienation should especially be felt among its traditional supporters in the region. Namely, because a high share of the SPD's historic electoral base, the working class, was employed in the coal industry. Therefore, the closure of the coal industry, with its high economic and status importance, should result in alienation especially among the core constituency of the Social Democrats. This might translate into coal communities feeling like their voices have not been heard by their long‐term political ally both regarding the specific topic of the coal phase‐out and matters of politics more generally.

Next to specific disapproval of the 2007 phase‐out law leading to disappointment with the issue‐owning party among affected communities, this more general alienation vis‐à‐vis the SPD is expected to constitute a second possible source of disappointment in response to coal closures. Both factors should lead to impacted municipalities – and, more specifically, working‐class individuals with direct or indirect ties to the coal industry – punishing the SPD by withdrawing their electoral support for the party.

Hypothesis 3: A coal closure is associated with a lower vote share for the SPD in the affected municipality.

The decline of the German coal industry and the 2007 phase‐out law

The German coal industry experienced a long and gradual decline in employment numbers, which started in the 1950s. Originally, this was mainly for economic reasons as domestic hard coal became less competitive compared to imported hard coal and other forms of energy generation (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018).Footnote 1 However, extensive subsidies from the national government kept the uneconomical German coal sector alive (Brauers et al., Reference Brauers, Oei and Walk2020). This was driven by the key influence of the coal and steel industries, which formed an alliance with politicians – among which, as noted, especially the SPD had strong ties to coal –, as well as with the unions representing coal workers (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018). Moreover, the coal industry had served as the backbone of the German economy for decades and the motor of integration into the European Community, which tied local identities and economic dependence to this vital sector (Kalt, Reference Kalt2021).

The year 2007, however, would arguably mark the point at which environmental concerns first came to the fore as a contributing factor to the decline of the German coal industry. This is reflected in the debates occurring within the Bundestag, in which, after 2007, environmental issues superseded economic topics as the dominant frame associated with the coal industry (Müller‐Hansen et al., Reference Müller‐Hansen, Callaghan, Lee, Leipprand, Flachsland and Minx2021). With the launching of the Emissions Trading Scheme by the European Union in 2005, which included emissions from CFPPs, the burning of coal became more expensive (Commission, 2022). Moreover, the EU changed its state‐aid regulations, which effectively prohibited subsidies being paid to the German coal sector after 2018 (Schulz & Schwartzkopff, Reference Schulz and Schwartzkopff2016). This pushed the German government, which at that time was led by a grand coalition of Conservatives and Social Democrats, to adopt a law in 2007 mandating the phasing out of hard‐coal mining by 2018 (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018; Steinkohlefinanzierungsgesetz, 2007).Footnote 2

The hard‐coal phase‐out law of 2007 was adopted following an agreement between the federal government, the state governments of NRW and Saarland (the only two states with active hard‐coal mines at that time), the union of mining workers, IG BCE (closely affiliated with the SPD) and the mining company Ruhrkohle AG (Schulz & Schwartzkopff, Reference Schulz and Schwartzkopff2016). On the federal government's side, negotiations were led by the minister for the economy (Conservative) as well as the finance minister (Social Democrat) and the head of the chancellery (Conservative). The government of NRW, composed of the Conservative Party and Liberal Party, had a de facto blocking minority during these year‐long negotiations in representing the country's biggest coal‐producing state (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009).

In terms of party positions towards the coal industry, the 2007 phase‐out law was preceded by a gradual rejection of the continuation of the hard‐coal industry by all parties except the SPD, which still supported a prolongation of the subsidies and business as usual for hard‐coal mining (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009). Although the Conservatives had supported the coal industry for decades, this position would shift after the adoption of the EU's new state‐aid regulations. In 2005, with both federal and regional elections then taking place in NRW, the state's Conservative‐Liberal government adopted a coalition agreement which, for the first time in German history, included a call for a clear ending of hard‐coal subsidies. A few months later, the federal coalition of Conservatives and Social Democrats adopted a more moderate proposition on hard coal (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009). During the negotiations, the Conservatives, the Liberals as well as the Greens advocated for an earlier phase‐out by 2012, while an alliance of the mining company, unions (both IG BCE and the service‐sector union ver.di, which represents coal‐plant employees) and the Social Democrats, successfully pushed for a phase‐out by 2018. Their overall aim was a ‘socially compatible’ phase‐out given that, as of 2007, some 5 to 10 per cent of the workforce in the Ruhr area still worked in the mining sector (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018).

In terms of compensation and labour market policy, the agreement included the guarantee that every coal‐mine employee aged 37 (for those working below ground) or 42 (for those working above) or older was protected against unemployment via an early‐retirement programme. The cost of the latter to the government would be approximately 2 billion euros (IG Metall, 2021; Oei et al., Reference Oei, Brauers and Herpich2020). Representing 80 per cent of the worker's last net salary, these early‐retirement benefits were thus higher than standard German unemployment benefits and more generous than the compensation paid to coal‐mine workers in other European countries (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009; Furnaro et al., Reference Furnaro, Herpich, Brauers, Oei, Kemfert and Look2021). Moreover, as part of the agreement, coal‐mining companies would also pay for training for workers wishing to switch jobs (Furnaro et al., Reference Furnaro, Herpich, Brauers, Oei, Kemfert and Look2021). In addition to this compensation scheme for affected workers, the phase‐out was accompanied by the introduction of new structural and economic policies such as investment in the transport infrastructure and in higher education (Herpich et al., Reference Herpich, Brauers and Oei2018; Oei et al., Reference Oei, Brauers and Herpich2020). Overall, the phase‐out cost an estimated 14.8 billion euros, borne by the national government, the state governments and the EU, respectively.

The SPD's stance aside, the phase‐out's emphasis on social compatibility for affected workers can also be partially accredited to the specific system of co‐determination existing as part of the corporatist nature of interest‐group representation in Germany. Due to a specific law promulgated in 1952, German companies in the coal, iron and steel industries with more than 1000 workers must ensure the equal representation of shareholders and employees within each's supervisory board. Thus companies need approval from their employees to enact any changes to working conditions, making coal workers an essential part of the decision‐making process here (Furnaro et al., Reference Furnaro, Herpich, Brauers, Oei, Kemfert and Look2021; IG Metall, 2021). Taken together, these two circumstances – the involvement of unions and workers in the policy‐making process and the comparatively generous compensation scheme offered – make Germany a least‐likely case to observe political backlash to coal closures.

Methods and data

I use a series of staggered (DiD) models to estimate the effect of the first coal closure in a municipality on electoral results. More specifically, I zoom in on the case of NRW to analyse how vote shares for all parties represented in the regional parliament changed after the first coal closure in a municipality occurred. The focus on NRW is motivated by the fact that the majority of German coal closures after 2007 occurred in this state.Footnote 3 Although in recent decades they certainly took place in other regions too, such as East Germany, the timing and the context of those closures, occurring in the wake of German reunification, were very different to the closures following the 2007 coal phase‐out law. This would confound comparisons of coal closures in different regions of Germany. Moreover, NRW was one of the two federal states whose regional governments were actively involved in the policy‐making process vis‐à‐vis the 2007 phase‐out law, which arguably increased the salience of the coal industry's decline in this state. For these reasons, my empirical analysis focuses solely on this state.

Data and operationalisation

In this article, I use data on the location and date of closure of coal mines and CFPPs between 2007 and 2022, as well as municipal‐level data on election results (primarily regional but also federal and local elections) in NRW between 1990 and 2022.

To test the effect of coal closures on voting behaviour, data on the precise point in time at which the closures happened as well as on the geographical location of the coal plants and mines in question is needed. For the closed coal plants, the data used here stems mainly from the German Federal Network Agency (2024), which has kept a list of closed lignite and hard‐coal plants since 2011. I obtained data on the closures of coal plants between 2007 and 2011 from the websites of the specific coal plants affected or of their operators. For the closure of coal mines, I relied on information provided by the organisation Statistik der Kohlenwirtschaft (2019) (Statistics of the Coal Industry). I then cross‐checked this against the obtained data from the websites of the impacted coal mines or of their operators.

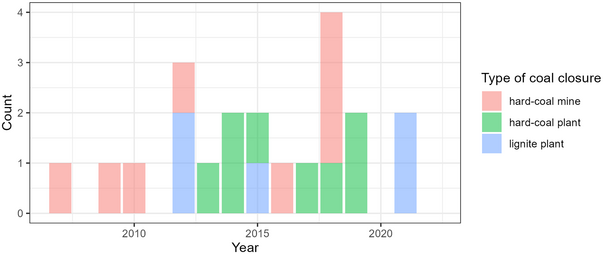

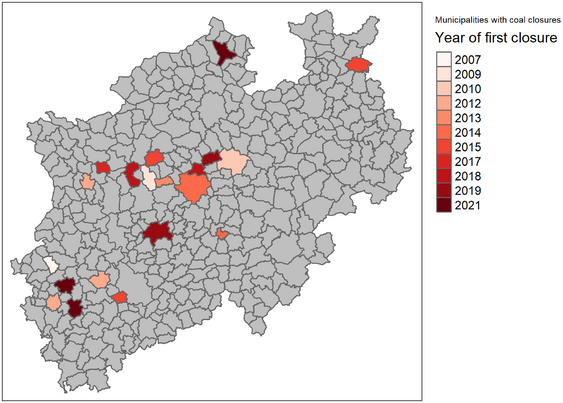

This data‐collection process resulted in an overall sample of 65 coal closures in 24 municipalities between the adoption of the phase‐out law in 2007 and the regional elections held in NRW in May 2022. However, in three municipalities which experienced coal closures and one without such an outcome, additional CFPPs during the same time period.Footnote 4 As this analysis focuses only on the electoral implications of the closure of coal plants and mines and not those associated with their construction, these four municipalities were excluded from the analysis so as to not bias the estimates.Footnote 5 Moreover, empirically examined is only the first coal closure per municipality because only eight out of the remaining 21 municipalities experienced more than one coal closure, which makes the sample too small to perform meaningful analyses of multiple closures within the same municipality. Figure 1 shows the distribution of these closures disaggregated by type of coal closure over time, while Figure 2 depicts the spatial distribution of municipalities with at least one coal closure during the observation period. For my empirical analysis, the independent variable of interest, namely the closure of coal plants and mines, is operationalised as the year a municipality was treated, meaning the one in which it experienced its first coal closure.

Figure 1. Temporal distribution of the first coal closure per municipality in NRW, 2007–2022.

Figure 2. Map of municipalities in NRW experiencing at least one coal closure between 2007 and 2022.

The main dependent variables for the main analyses are the election results of all parties currently represented in NRW's regional parliament as well as the turnout rate between 1990 and 2022, for which I collected data from the regional statistical office (Landesdatenbank NRW, 2024) (Appendix A in the Supporting Information contains details on the data and its collection for the national and local election results).Footnote 6 This results in four election years before the first possible treatment in 2007 (1990, 1995, 2000 and 2005) and four election years after 2007 (2010, 2012, 2017 and 2022).Footnote 7 While the Social Democrats, Greens, Christian Democrats and Liberals existed during the whole period under observation, this is not the case for The Left (Die Linke) and the AfD (in NRW). Founded in 2007, the Left Party competed in the regional elections from 2010 onwards, while the AfD, founded in 2013, only participated in the elections in 2017 and 2022.

Empirical strategy

To identify the effect of the first coal closure on voting behaviour at the municipal level, I rely on staggered DiD models using the estimator developed by Callaway & Sant'Anna (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021). In contrast to two‐way fixed‐effects models, staggered DiD ones are able to take into account potentially heterogeneous treatment effects and use a clearly defined control group (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Sant'Anna, Bilinski and Poe2023). This makes them better suited than two‐way fixed‐effects models in the event of staggered treatment rollout.

For the first coal closure per municipality, the staggered DiD estimator by Callaway & Sant'Anna (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021) calculates average treatment effects for groups of municipalities which first become treated in the same year, so‐called group‐years. The baseline model is specified as follows:

where VoteSharemt identifies a municipality m’s vote share for the specific party in group‐year g and β identifies the effect of the treatment indicator (First.Treatmg) – operationalised as the year in which the first closure occurred for a given municipality – on vote shares. ϵmt identifies the error term. To aid interpretation, these coefficients are then aggregated into group‐specific average treatment effects for treated municipalities across all lengths of exposure, which provides the ‘average effect of participating in the treatment experienced by all units that ever participated in the treatment’ (Callaway & Sant'Anna, Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021: 12). Thus, the effect is an average across all election periods equivalent to the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) in the standard DiD set‐up consisting of two groups and two periods. For the estimations at hand, I rely on bootstrapped standard errors clustered at the municipal level and use only those municipalities which never experienced a coal closure – that is, the never‐treated – as the control group.

Identification of the staggered DiD estimates relies on the assumption of parallel trends of average vote shares in untreated and treated municipalities had they not received the treatment (Angrist & Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). Due to the counterfactual nature of this assumption, it is not directly testable. However, in a first step, I analyse the balance between treated and control municipalities in the year before the earliest possible treatment, 2006, which can indicate whether there are structural differences between treated and control municipalities prior to the treatment. Table B.1 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information shows the pre‐treatment balance on several variables related to population and employment characteristics, ones potentially tying into both the treatment assignment and the dependent variables (Appendix B of the Supporting Information contains details on the data collection for these variables). It can be seen that treated municipalities are significantly more likely to have at least one operational coal plant or mine before treatment, are more urban and have a higher population density. To mitigate for these variables’ influence on results, I conduct coarsened exact matching (CEM) to identify a set of control municipalities which are as similar as possible in nature to those municipalities to be treated (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007; Iacus et al., Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012). Since the number of treated municipalities differs between regional, national and local elections, I performed separate matching processes for the three levels. Table B.2 and Figures B.1 to B.3 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information show that CEM considerably improves balance among treated and control units. I then perform all staggered DiD estimations with both the full and the matched datasets. Second, event study plots allow for a more direct way to assess whether there are significant pre‐treatment differences in the outcome variable between treated and control units. Therefore, I plot event study estimates using Callaway & Sant'Anna's (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021) estimator in Figures C.4 to C.9 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for the full and the matched samples for all three levels of elections. They show that for all models, the assumption of common pre‐trends seems to hold.Footnote 8

The level of analysis in this article is, as noted, the municipality, of which there are 396 in NRW. In addition to the theoretical considerations informing this choice, as detailed earlier, methodological ones also support this zooming in on the municipality. Following Toshkov (Reference Toshkov2016), the level of analysis should be chosen according to the level at which the treatment in question can be isolated. In the case of coal closures, the most fine‐grained administrative level at which this effect can be isolated is the municipal one, as representative data on voting behaviour at the individual level for the period of observation is not available for NRW. In addition to this practical reason, some substantive considerations also speak in favour of using aggregate data instead of individual‐level survey data on voting behaviour given that the latter suffers from issues of representativeness. First of all, marginalised social groups tend to be underrepresented in survey data because they have a lower probability of participating therein, which might arguably be the case for disappointed voters. Second, survey responses regarding one choosing to vote for an extremist party or to abstain might be biased as people tend to under‐report these kinds of behaviour to save face. Taken together, this makes data in the form of actual election results at the municipal level the preferred source here.

Results

First coal closure and voting behaviour

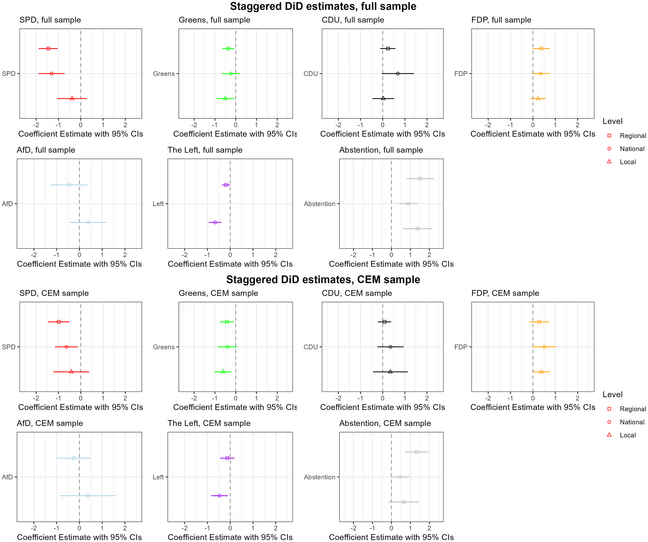

Figure 3 presents coefficient plots of the results from the staggered DiD models for the full and the matched samples for all three levels of elections (see Tables D.3 to D.8 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for the corresponding regression tables). Generally, the results for each party all head in the same direction regardless of the level of elections and remain very similar when comparing the results using the full and the matched samples. Both the full sample and the matched sample analysis show that the first coal closure in a municipality is significantly associated with a decrease in the vote share for the SPD in the subsequent regional and federal elections. For the local elections, the negative effect is not significant. Moreover, the first coal closure increases the abstention rate in the affected municipality for all three levels of elections (this effect is not significant for the matched sample for federal and local elections). Regarding the results for the AfD, the first coal closure has no significant effect on vote shares for both regional and federal elections.

Figure 3. Staggered DiD estimates (overall ATT) of first coal closure on vote shares for different levels of elections.

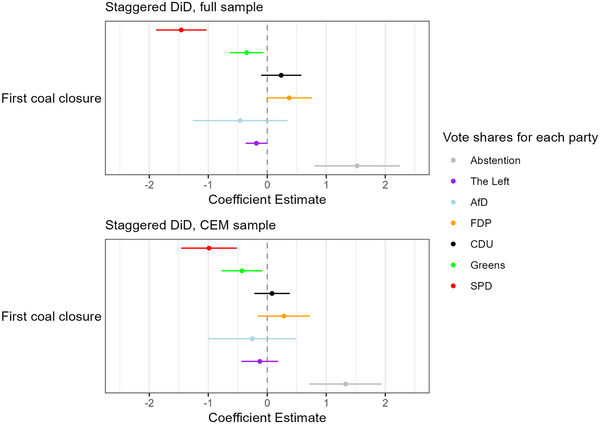

Moreover, these results show that the effects seem strongest for regional elections. Even though the phase‐out policy was adopted at the federal level, this is plausible given that it only affected NRW and one other state and that their state‐level governments also participated in its negotiations. Therefore, Figure 4 zooms in on the regional election results, facilitating a comparison of the results for the different parties. It shows that the first coal closure has the largest effects on SPD vote shares (–1.46 percentage points with the full sample and –0.99 percentage points with the matched sample) and abstention rates (+1.52 percentage points with the full sample and +1.33 percentage points with the matched sample). In substantive terms, the effect sizes for both abstention and SPD vote‐share losses correspond to around one quarter of the standard deviation of the two variables between 2010 and 2022. These effects are comparable to – or even larger than – those found in existing studies on the electoral consequences of coal closures (Bolet et al., Reference Bolet, Green and González‐Eguino2024; Egli et al., Reference Egli, Schmid and Schmidt2022; Gazmararian, Reference Gazmararian2024) and of offshoring (Margalit, Reference Margalit2011; Rickard, Reference Rickard2022).

Figure 4. Staggered DiD estimates (overall ATT) of first coal closure on vote shares, regional elections.

To assess the temporal dynamic of the effect on abstention rates in regional elections, Figures D.10 and D.11 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information show event study plots based on two‐way fixed‐effects models allowing assessment of whether the effects on abstention rates occur in the election period immediately after the coal closure or in subsequent election periods.Footnote 9 However, these event study plots have to be interpreted with caution as the sample size of treated municipalities disaggregated by the election period during which they were treated is small, which is why the overall ATT is a more reliable measure of the effect of coal closures on voting behaviour (Callaway & Sant'Anna, Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2022). Nevertheless, these figures offer some preliminary insights into how persistent the effects on abstention rates are and whether they faded after the AfD's founding in 2013. The patterns in both figures suggest that the positive effect of a coal closure on abstention rates in the respective municipality occurs mainly in the subsequent election periods. For example, municipalities treated between 2007 and 2010 or between 2012 and 2017 experienced a positive effect on abstention rates even in the 2022 election. This goes against the notion that disappointed voters switch from abstaining to voting for a far‐right party as soon as the latter has entered the fray. Instead, as expected, it suggests that abstaining as a reaction to coal closures occurs independently of the presence of a far‐right party courting followers.

I perform additional analyses to assess whether my main findings are robust to different sample specifications. More specifically, I conduct the main analyses using regional election results with the complete sample of NRW's 396 municipalities, which also includes the four in which additional CFPPs were constructed during the period of observation (see Figure E.12 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for an assessment of post‐matching balance and Tables E.9 and E.10 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for the regression tables). These estimations support my main findings, which are consistently robust to this alternative specification of the sample.

Overall, this suggests that even relatively generous compensation for the losers of structural economic change and the involvement of unions in the policy‐making process cannot mitigate political backlash. Tying these results back to the three formulated hypotheses, the analysis of the first coal closure for a municipality reveals strong support for a positive effect here on abstention rates (H2) and for a negative one on SPD vote shares (H3). However, these findings do not support the hypothesis that coal closures lead to higher vote shares for the far‐right AfD (H1). This is, however, expected as the AfD was, as noted, only founded in 2013 and competed for its first regional elections in 2017, making it difficult to detect significant effects thus far.

Indicative evidence for mechanisms

Having established a negative effect of coal closures on vote shares for the SPD and a positive effect on abstention rates, this section now provides indicative evidence for potential mechanisms at work here by centring the investigation on the theoretical expectations formulated earlier. Exploring such mechanisms is complicated by the fact that most of the data for the main analysis is not sufficiently fine‐grained. Moreover, high‐quality panel data such as the German Socio‐Economic Panel cannot be used because the sample size in the treated municipalities is too small. However, a few alternative data sources exist which allow for some descriptive statistics on potential mechanisms.

First, I leverage municipal‐level data on economic indicators from Wegweiser Kommune (2024) (available for the years 2006–2021). Moreover, I use data from the 2020 and 2022 waves of the Inequality Barometer, a repeated cross‐sectional survey (Bellani et al., Reference Bellani, Bledow, Busemeyer and Schwerdt2021; Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Schönhage, Baute, Bellani and Schwerdt2023). Finally, I use data from multiple waves of the Politbarometer (a cross‐sectional monthly election survey) (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, Mannheim, 2019; Jung et al., Reference Jung, Schroth and Wolf2008). All surveys are representative of the German population. As these surveys are not panels, they cannot be used to estimate the effect of coal closures on perceptions as part of a staggered DiD design but rather offer insights into changes in perceptions continuing to persist even a few years after the coal closure in question. Bearing in mind that the sample size is rather small, the survey data are nevertheless informative by revealing some descriptive patterns which can be cautiously interpreted as indicative of possible effects.

I begin by testing the hypothesised link between coal closures and economic grievances regarding individuals living in affected municipalities, which the existing literature has linked to political disengagement (Kurer, Reference Kurer2020; Solt, Reference Solt2008). Especially for coal workers, experiencing a decline in their economic standing seems plausible given that the early‐retirement payments which most of them received after the coal closure represented 80 per cent of their income (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009). Moreover, negative spillover effects on the economic well‐being of the wider community seem likely, as coal closures also had repercussions for downstream industries. To test whether a coal closure results in negative economic implications for affected municipalities, I use municipal‐level data on the local employment rate and per capita purchasing power from Wegweiser Kommune as dependent variables (2024).Footnote 10 I then estimate staggered DiD regressions based on Callaway & Sant'Anna's (Reference Callaway and Sant'Anna2021) approach, both with the full and matched samples.

Tables F.11 and F.12 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information present the coefficients of the overall ATT of first coal closures on the employment rate and on purchasing power (see Figures F.13 and F.14 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for an assessment of pre‐trends), showing that while coal closures have a significant negative effect on both, these repercussions disappear for the matched sample. Thus, when comparing treated municipalities to their most‐similar control ones, there does not seem to be a negative effect on the community's economic well‐being. This supports the notion that the compensation programme accompanying the hard‐coal phase‐out was at least to some extent successful: taking this pathway did not lead to increased unemployment or lower purchasing power in affected municipalities. These findings are in line with a 2021 study commissioned by the German Environmental Agency, which found that the policy successfully avoided redundancies (Reitzenstein et al., Reference Reitzenstein, Popp, Oei, Brauers, Stognief, Kemfert, Kurwan and Wehnert2021). Political backlash to coal closures thus does not seem to be driven by material considerations.

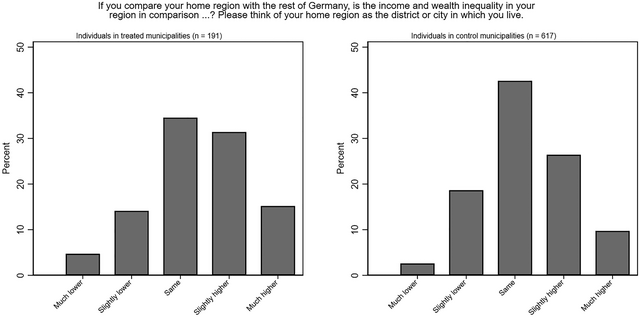

However, even if there are no objective negative effects on the economic situation in treated municipalities, individuals’ perceptions might still differ. Thus, those living in treated municipalities might still deem their communities to have been subject to economic deprivation. Using data from the Inequality Barometer survey from 2022, I descriptively analyse how individuals in treated and control municipalities perceive the economic situation in the form of economic inequality in their home region compared to in Germany at large. I use the same control group based on CEM as for the main analyses. Figure 5 shows that, in 2022, individuals in treated municipalities rated economic inequality in their home region compared to the rest of Germany significantly higher than those living in control municipalities did.Footnote 11

Figure 5. Perception of economic inequality in home region compared to in Germany at large. Author's own compilation based on Inequality Barometer 2022 survey (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Schönhage, Baute, Bellani and Schwerdt2023).

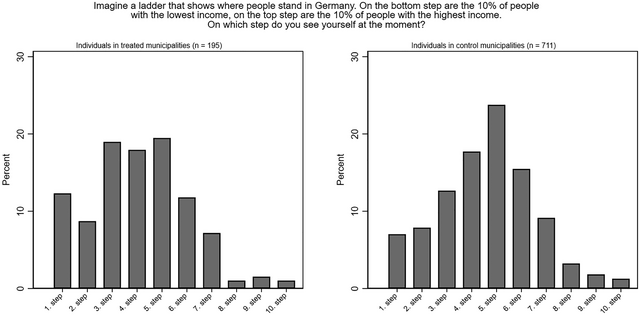

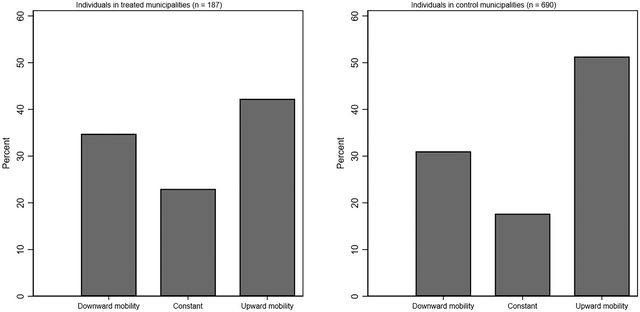

In addition to material concerns about their community, individuals might also perceive personal material grievances in comparison to others, as well as status concerns. The expectation of coal closures triggering feelings of relative economic deprivation and economic‐status concern is supported by data from the 2020 Inequality Barometer. Figure 6 shows that individuals in treated municipalities perceive their position in the income distribution to be significantly lower than individuals in control municipalities. This pattern of perceived relative economic deprivation is further supported by Figure 7, which demonstrates that among individuals in treated municipalities, the perception of downward mobility, that is, a decline in their own income position compared to their parents’ income position, is more prevalent.

Figure 6. Perception of individuals’ position in the income distribution. Author's own compilation based on Inequality Barometer 2020 survey (Bellani et al., Reference Bellani, Bledow, Busemeyer and Schwerdt2021).

Figure 7. Perception of individual intergenerational income mobility. Author's own compilation based on Inequality Barometer 2020 survey (Bellani et al., Reference Bellani, Bledow, Busemeyer and Schwerdt2021).

In the absence of survey data on social‐status perceptions, it is not possible to directly assess whether individuals who experienced a coal closure in their municipality deem there to have been a decline or threat to their social standing beyond materially speaking. However, evidence from other studies supports the notion that this mechanism might also be at play here, including studies commissioned by the blue‐collar union IG Metall (which is close to the coal workers’ union IG BCE) as well as carried out by Hennicke & Noll (Reference Hennicke and Noll2020). Herein, many of the jobs which former coal workers were transferred to were in lower‐paid service‐sector employment, resulting in experiences of status decline, frustration and dissatisfaction (IG Metall, 2021).

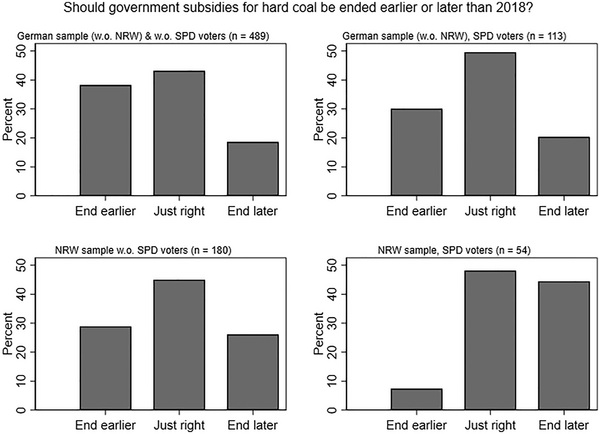

Finally, I argued that the impact of coal closures on SPD vote shares is driven by disappointment with the Social Democrats as the long‐term political ally of coal workers. I use Politbarometer data to analyse whether those frustrated over coal closures punish the issue‐owning party. However, since this survey does not contain any geographical identifier apart from the state in which respondents live, assigning respondents to treated municipalities is impossible. Instead, I compare respondents living in NRW to those living in another German state as well as respondents who stated that they would vote for the SPD in the next election to those who would vote for any other party. As the SPD has very close ties to the coal community, the group of SPD voters in NRW is the closest approximation to individuals who are directly affected by coal closures. Figure 8 demonstrates that, in 2007, individuals living in NRW who stated that they would vote for the SPD in the next election had a clear preference for ending the government subsidies for hard coal later than 2018, while all other groups would choose to do so earlier. It thus seems plausible that those directly affected by the policy are those least satisfied with the policy of phasing out coal until 2018 and that they subsequently turn their back to the issue‐owning party. This dissatisfaction is further exemplified by the large demonstrations by coal workers occurring during the final stages of negotiations, with close to 10,000 people taking to the street against the planned closures (Frigelj, Reference Frigelj2009).

Figure 8. Preferences regarding the ending of hard‐coal subsidies by 2018. Author's own compilation based on Politbarometer data (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Schroth and Wolf2008).

This pattern is corroborated by Figure F.15 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information, showing that in the years 2003–2005 – even before the hard‐coal phase‐out law was first discussed –, SPD voters in NRW were least in favour of cuts to hard‐coal subsidies compared to SPD voters in other federal states as well as to those casting their ballot for any other party in NRW, too. Finally, Figure F.16 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information demonstrates that, in 2007, SPD voters in NRW attached the highest importance to future hard‐coal mining compared to all other electoral groups. These descriptive patterns support the notion that the 2007 hard‐coal phase‐out law was very unpopular among those in NRW closely affiliated with the Social Democrats compared to peers who voted for any other party as well as those elsewhere in Germany. Therefore, it seems very likely that this group subsequently punished their former political ally at the ballot box.

All in all, this section has shown that, on the one hand, coal closures have not led to an objective decline in community‐wide economic well‐being in affected municipalities. However, on the other, the descriptive patterns presented here also paint a picture of perceived economic deprivation and widespread disappointment with the introduced phase‐out policy among those living in affected communities, as leading to higher abstention rates and lower vote shares for the Social Democrats.

Alternative explanations

So far, I have argued that the effects on vote shares in treated municipalities after 2007 have been caused by coal closures and that they are mainly driven by individual factors such as perceptions of material decline and disappointment with the issue‐owning party. In this section, I now discuss two other explanations potentially driving these effects.

First, whether individuals punish or reward certain parties for coal closures could depend on which ones were in government at the time. Existing research has highlighted how, in some contexts, electoral behaviour can be explained by individuals punishing incumbents, such as for the construction of wind turbines (Stokes, Reference Stokes2015), trade‐related job losses (Margalit, Reference Margalit2011) and offshoring (Rickard, Reference Rickard2022). Alternatively, they may also reward those in power, such as in the case of the Spanish coal phase‐out (Bolet et al., Reference Bolet, Green and González‐Eguino2024).

To assess the validity of this first alternative explanation, Tables G.13 to G.15 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information indicate which parties were in government during the period of observation at the regional, national and local levels.Footnote 12 Based on this, I quantitatively investigate whether there is an association between a party being part of a government coalition and its amassed vote shares in the election immediately following a coal closure (see Section G in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for details on the estimation strategy).

The results of these regressions are presented in Figures G.17 to G.20 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information, with black bars indicating that a particular party was part of the governing coalition during a certain election period and grey bars denoting it was part of the opposition. These figures reveal no consistent pattern as to whether parties experience a decline or an increase in their vote shares due to coal closures when they are incumbents. However, as the number of affected municipalities was small when disaggregating the coal closures for each election period, these results need to be interpreted with caution and can only serve as suggestive evidence. Nevertheless, they do not support the notion of a backlash against the incumbent as a reaction to coal closures.

An additional way to analyse whether incumbency plays a role in shaping how a coal closure affects voting behaviour is to assess the temporal dynamic of the effect on SPD and CDU vote shares. If incumbency affected the relationship, we should expect to see an effect only in the period when a party was part of the governing coalition. Similar to Figures D.10 and D.11 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information, where I look at abstention, Figures G.21 to G.24 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information show event study plots based on two‐way fixed‐effects models. First of all, the effects in period 1 correspond to those displayed in Figures G.17 to G.20 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information. Moreover, the figures suggest that the effect of a coal closure on vote shares for the SPD and the CDU occurs mainly in subsequent election periods and periods in which the party is not part of the governing coalition. This further suggests that the results are not driven by an incumbency effect.

A second alternative explanation could be that it was not the closures themselves but rather their announcement in the context of the 2007 hard‐coal phase‐out law's adoption subsequently influencing voting behaviour in municipalities operating CFPPs or coal mines in that year and which then experienced a closure later. If true, this might be driven by fears of economic hardship or status decline rather than by the actual experiencing thereof (Kurer, Reference Kurer2020). I estimate 2‐year DiD models to test this possible announcement effect (see section H in the Appendix of the Supporting Information for details on the estimation strategy). As The Left and the AfD were, as noted, only founded in 2007 and 2013, respectively, this analysis cannot be performed for these two parties here. The results of the DiD regressions are displayed in Tables H.16 to H.19 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information. In contrast to the effect of coal closures, the adoption of the phase‐out policy seems to have created a backlash against the two parties in government pursuing it: the Conservatives and the Liberals. On the other hand, their embracing of this policy also seems to have increased voter abstention, similar to with the closure of CFPPs and coal mines. Here, the effect is not limited to municipalities eventually seeing a coal closure but also those with operating CFPPs set to remain open until 2022. Yet, the event study plots in Figures B.2 and B.3 in the Appendix of the Supporting Information show that among municipalities subject to a coal closure, the assumption of parallel trends seems to hold. Thus, there appears to be no anticipation effect in comparison to control municipalities. These findings allow me to rule out the possibility that the results pertaining to my three hypotheses are driven by an immediate reaction to the entering into force of the hard‐coal phase‐out law in 2007 and not the coal closures themselves.

Conclusion

I have provided evidence for an asymmetric backlash to the closure of German coal plants and mines since 2007, as expressing itself through a significantly negative effect on vote shares for the Social Democrats and a positive effect on abstention rates in treated municipalities compared to control municipalities. Additionally, I did not find any support for a positive effect of coal closures on vote shares for the AfD; however, this might also be due to the only short period of time in which the party has been competing in elections to date. Moreover, I have shown that these results are not driven by an incumbency effect or an immediate reaction to the announcement and entry into force of the 2007 phase‐out law but rather by the coal closures themselves. This represents the first empirical analysis of electoral backlash to structural economic change despite the presence of compensation schemes for those negatively affected and the involvement of coal workers in political decision‐making. Even though the German corporatist system of interest‐group representation foresees the active participation of unions in the policy‐making process, being also the case for the coal phase‐out, and even though there was targeted compensation for affected workers to alleviate economic grievances, these circumstances did not succeed in preventing an electoral backlash locally. Instead, the reasons for this seem to go beyond factors such as the existence of compensation schemes or labour representation. More precisely, I provide indicative evidence for possible underlying mechanisms supporting the notion that, instead of actual economic repercussions, coal closures seem to trigger the perception of having been subject to material deprivation as well as disappointment with the issue‐owning party among affected individuals.

Regarding the potential effect of coal closures on AfD vote shares, empirical analysis is constrained by the fact that the latter was founded in 2013, thus participating only in the last two elections in NRW. Therefore, this article can only offer first insights on the specific relationship between coal closures and far‐right voting patterns. Replicating this study for upcoming elections would represent a meaningful avenue by which to explore this link in more detail.

Especially, the role of social‐status loss in influencing subsequent voting behaviour among communities with formerly high standing in the public eye merits further close investigation. Given the lack of representative time‐series data available at the individual level in NRW, focus‐group interviews in coal‐producing regions might be a promising pathway for future scholarship to disentangle the specific roles which social status and compensation play in influencing voter choices. This might yield interesting insights concerning the conditions under which electoral backlash against coal closures can potentially be attenuated.

All in all, the findings provide evidence for the electoral implications of a transformation still ongoing in Germany and yet to be faced by many other countries worldwide. In NRW alone, as of 2024, 38 CFPPs as well as three lignite open‐cast mines still remain in operation, all of which will be shut down by 2038 at the latest (German Federal Network Agency, 2024). With the significant politicisation around coal phase‐outs and the high salience of fossil fuel‐based power generation, the asymmetric backlash to coal closures in NRW increases the importance of understanding the conditions under which such a response can be mitigated if other countries are to adopt sound policies going forwards.

Acknowledgements

I thank Diane Bolet, Brian Burgoon, Marius Busemeyer, Søren Frank Etzerodt, Alexander Gazmararian, Roman Krtsch, David Rueda, Gabriele Spilker, Alexander Trubowitz, Nadja Wehl, Theresa Wieland, Felix Wortmann‐Callejón, the reviewers and editors at EJPR, members of the Working Group on Comparative Political Economy at the University of Konstanz and the participants at the Summer Academy ‘Challenging Inequalities’ at the University of Duisburg‐Essen 2022, the ESPAnet Italy Conference 2022, the Workshop ‘The Politics of Climate Change: Current Issues and Challenges’ at the University of Lucerne 2022, the GSBS Brown Bag Seminar at the University of Konstanz 2023, the EPG Online Seminar 2023 and the EPG Graduate Workshop 2023 for very helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials and code have been published at the GESIS data repository (https://doi.org/10.7802/2831).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting information