Introduction

Manufacturing firms are facing mounting pressure to revamp their operations as new digital technologies, changing regulatory demands, and shifting customer expectations reshape how value is created and delivered (Chakma, Paul, & Dhir, Reference Chakma, Paul and Dhir2024; Hashem, Reference Hashem2024; Nosella, Cantarello, & Filippini, Reference Nosella, Cantarello and Filippini2012; Shi, Reference Shi2024). This challenge is particularly acute for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): they are often resource-constrained, with limited slack to fund parallel initiatives, yet they must still improve efficiency, quality, and flexibility to remain viable in increasingly dynamic markets (Voss & Voss, Reference Voss and Voss2013; Wenke, Zapkau, & Schwens, Reference Wenke, Zapkau and Schwens2021; Zahoor, Al–Tabbaa, & Khan, Reference Zahoor, Al–Tabbaa and Khan2023). Because SMEs are central to employment, value creation, and regional development, their capacity to innovate has disproportionate consequences for economic growth and industrial competitiveness. For many SMEs, operational innovation therefore becomes a high-stakes balancing act, upgrading technologies and production systems while simultaneously developing the human capabilities needed to implement, adapt, and continuously improve those systems (Da Silva et al., Reference Da Silva, Soltovski, Pontes, Treinta, Leitão, Mosconi, De Resende and Yoshino2022; Harney & Collings, Reference Harney and Collings2021; Prajogo & Oke, Reference Prajogo and Oke2016).

This balancing act maps onto the exploration–exploitation paradox: firms must refine and scale what already works (exploitation) while also searching for new processes, practices, and solutions (exploration) to sustain competitiveness over time (Aslam, Blome, Roscoe, & Azhar, Reference Aslam, Blome, Roscoe and Azhar2018; Schad, Lewis, Raisch, & Smith, Reference Schad, Lewis, Raisch and Smith2016; Su, Cui, Samiee, & Zou, Reference Su, Cui, Samiee and Zou2022; Wang, van de Vrande, & Jansen, Reference Wang, van de Vrande and Jansen2017). Two dominant perspectives propose different ways of addressing this tension. Punctuated equilibrium theory emphasises temporal separation, suggesting firms alternate between periods of stability and episodes of change (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Benner, Brunner, MacDuffie, Osono, Staats, Takeuchi, Tushman and Winter2009). Ambidexterity research, by contrast, argues for the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation as a basis for sustained innovation performance (Foss & Kirkegaard, Reference Foss and Kirkegaard2020; O’Reilly, Tushman, & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly, Tushman and Tushman2013). Recent work further suggests that environmental dynamism shapes which approach is feasible: in high-velocity settings, temporal separation may be harder to maintain, potentially favouring ambidextrous approaches (Clercq, Thongpapanl, & Dimov, Reference Clercq, Thongpapanl and Dimov2014; Evers & Andersson, Reference Evers and Andersson2021; Fu, Qin, Li, & Li, Reference Fu, Qin, Li and Li2024; Yuan, Xue, & He, Reference Yuan, Xue and He2021). Yet for manufacturing SMEs, it remains unclear whether ambidexterity is realistically achievable or beneficial, given persistent resource constraints and limited structural capacity to support dual strategies (Voss & Voss, Reference Voss and Voss2013; Wenke et al., Reference Wenke, Zapkau and Schwens2021). While some studies imply that SMEs may need to innovate sequentially (Bierly & Daly, Reference Bierly and Daly2007; Wu, Liu, & Zhang, Reference Wu, Liu and Zhang2024), the empirical evidence on the ambidexterity–performance relationship in manufacturing SMEs is still mixed and inconclusive (Fan, Cheng, Chun, & Zhang, Reference Fan, Cheng, Chun and Zhang2024; Farzaneh, Wilden, Afshari, & Mehralian, Reference Farzaneh, Wilden, Afshari and Mehralian2022; Hu, Dou, & You, Reference Hu, Dou and You2023; Mathias, McKenny, & Crook, Reference Mathias, McKenny and Crook2018; Randhawa, Nikolova, Ahuja, & Schweitzer, Reference Randhawa, Nikolova, Ahuja and Schweitzer2021). This is a consequential gap: operational renewal increasingly requires firms to make difficult allocation decisions, especially between investing in technology (often linked to exploitation) and mobilising human resources for learning, adaptation, and creative problem solving (often related to exploration) (Voss & Voss, Reference Voss and Voss2013; Zimmermann, Raisch, & Cardinal, Reference Zimmermann, Raisch and Cardinal2018).

Without clearer evidence, managers in resource-constrained firms lack guidance on whether they should attempt to ‘do both’, or instead prioritise and sequence innovation efforts over time. Against this background, we ask whether ambidexterity remains a viable strategic orientation for resource-constrained firms, that is, SMEs, under innovation pressure, or whether sequential approaches, focused more narrowly on exploration or exploitation, offer superior outcomes. We address the following research questions: First, under innovation pressure, how does an ambidextrous orientation toward exploration and exploitation relate to operational performance in manufacturing firms? Second, how do human resource deployment and technological investment shape exploration–exploitation choices in operational innovation, and how do these mechanisms vary by firm size?

To answer these questions, we draw on both conditional process analysis (CPA) (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) and data from the European Commission’s Flash Eurobarometer No. 433, which surveys European businesses regarding their innovation-related activities and attitudes (European Commission, [2016]). The dataset comprises 14,117 firms, including 13,117 headquartered in the 28 EU member states and 500 firms each from Switzerland and the United States. To ensure comparability in operational processes, we restrict our analysis to 2,213 firms from European countries and Switzerland. Using this dataset, we examine how exploration and exploitation relate to operational performance under varying levels of innovation pressure, and we test whether these relationships differ systematically by firm size.

Our findings, in brief, show that firm size negatively moderates the performance implications of a technology-focused pathway, whereas the human-resource-focused pathway exhibits a positive size moderation effect. Innovation pressure positively predicts technology focus, but we do not find a statistically significant or substantively meaningful mediation effect via human-resource focus. These results contribute to ambidexterity research by clarifying when ‘doing both’ is viable in resource-constrained contexts (Iborra, Safón, & Dolz, Reference Iborra, Safón and Dolz2020; Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst, & Tushman, Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009), and to the operational innovation literature by foregrounding the joint role of people and technology in renewal efforts under pressure (Dieste, Sauer, & Orzes, Reference Dieste, Sauer and Orzes2022; Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Raisch and Cardinal2018). Practically, they offer decision-relevant guidance for SME managers: rather than defaulting to an ambidextrous ideal, firms can align exploration and exploitation choices with their resource profiles and the intensity of innovation pressure they face.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Technological investments, innovation pressure and operational innovation

Recent developments in organisational theory, particularly research on ambidexterity, emphasise firms’ need to address paradoxical demands simultaneously. Moving beyond conventional ‘either/or’ trade-offs, this work advances a ‘both/and’ logic, suggesting that sustained performance increasingly depends on the capacity to accommodate and balance competing imperatives (Lewis & Smith, Reference Lewis and Smith2022; Smith, Reference Smith2014; Visnjic, Jovanovic, & Raisch, Reference Visnjic, Jovanovic and Raisch2022; Weiser & Laamanen, Reference Weiser and Laamanen2022). Consistent with this view, innovation ambidexterity describes a firm’s ability to pursue incremental and radical innovation concurrently by orchestrating inherently conflicting structures, processes, and cultural elements (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009). In doing so, ambidexterity provides a mechanism through which contextual conditions translate into heterogeneous performance consequences across firms (Lin, McDonough, Lin, & Lin, Reference Lin, McDonough, Lin and Lin2013).

Innovation pressure arises from features of the competitive and institutional environment, including market structure, opportunity conditions, and regulatory regimes, that shape firms’ incentives and constraints (Porter, Reference Porter1980; Williamson, Reference Williamson1975). Such pressures may prompt substantive changes in operational and production systems (Ghosh & Shah, Reference Ghosh and Shah2015). Although classic contributions argue that competitive forces can stimulate innovation (Arrow, Reference Arrow and Nelson1962; Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1942), accumulated evidence remains equivocal. Empirical studies often link heightened competitive pressure to stronger innovation outcomes (Autor, Dorn, Hanson, Pisano, & Shu, Reference Autor, Dorn, Hanson, Pisano and Shu2020; Petit & Teece, Reference Petit and Teece2021; Porter, Reference Porter1990), yet theoretical accounts imply a more contingent relationship, in which the direction and magnitude of effects depend on boundary conditions and firm responses (Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Lahneman, Beukel, Cerrato, Minciullo, Spielmann and Discua Cruz2020; Vives, Reference Vives2008). This inconsistency points to the need for models that specify the intervening mechanisms connecting innovation pressure to innovation outcomes.

Mediating effects of ambidextrous strategies on operational innovation

Applying ambidexterity theory within operations management emphasises the simultaneous achievement of flexibility and efficiency (Aslam et al., Reference Aslam, Blome, Roscoe and Azhar2018). In contrast, punctuated equilibrium theory suggests firms may strategically prioritise either flexibility or efficiency (Porter, Reference Porter1980). Nonetheless, recent empirical studies increasingly validate the beneficial impacts of ambidextrous strategies across various operational domains, including governance structures (Blome, Schoenherr, & Kaesser, Reference Blome, Schoenherr and Kaesser2013), technology sourcing (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Del Giudice, Malik, Tarba, Temouri, Budhwar and Patnaik2021), supply chain configurations (Bettiol, Capestro, Di Maria, & Micelli, Reference Bettiol, Capestro, Di Maria and Micelli2023; Gualandris, Legenvre, & Kalchschmidt, Reference Gualandris, Legenvre and Kalchschmidt2018), and manufacturing systems (Lu, Zhou, & Dou, Reference Lu, Zhou and Dou2023; Roscoe & Blome, Reference Roscoe and Blome2019).

Successfully executing ambidextrous strategies in manufacturing contexts necessitates leveraging two primary organisational resources: technological assets and human capital (Boonman, Hagspiel, & Kort, Reference Boonman, Hagspiel and Kort2015; Pak, Heidarian Ghaleh, & Mehralian, Reference Pak, Heidarian Ghaleh and Mehralian2023; Varandas, Fernandes, & Veiga, Reference Varandas, Fernandes and Veiga2024). Accordingly, firms strategically invest in advanced technologies to exploit operational efficiencies or leverage human capital to explore novel operational approaches.

The mediating effect of technological investments

Investments in production technology typically reflect a strategic orientation toward exploiting available operational opportunities (Gaimon, Reference Gaimon2008). Ambidextrous exploitation encompasses activities such as refining processes, enhancing efficiency, and effectively executing production tasks (Luger, Raisch, & Schimmer, Reference Luger, Raisch and Schimmer2018; March, Reference March1991). Investment in advanced production technologies aims to align operational systems closely with evolving customer demands while simultaneously enhancing operational efficiency and effectiveness (Salvador, Chandrasekaran, & Sohail, Reference Salvador, Chandrasekaran and Sohail2014). Moreover, investments in technology under competitive innovation pressures facilitate firms’ ability to rapidly adapt, streamline operational routines, and achieve operational excellence, thereby creating sustainable competitive advantages (Helfat & Winter, Reference Helfat and Winter2011; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997).

However, successful technology exploitation necessitates flexible and adaptable organisational structures capable of managing incremental and occasionally disruptive changes within established routines (Loch, Reference Loch2017). Furthermore, the iterative process of technological innovation generates proprietary knowledge and capabilities, establishing path-dependent trajectories that are difficult for competitors to replicate, thereby enhancing long-term strategic advantage (Kogut & Zander, Reference Kogut and Zander1996; Mahmood & Mubarik, Reference Mahmood and Mubarik2020; Zakrzewska-Bielawska, Reference Zakrzewska-Bielawska2016). Additionally, technology investments foster intra-firm knowledge diffusion and learning mechanisms, enhancing both innovation absorptive capacity and adaptive capabilities (Cohen & Levinthal, Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Patel, Terjesen, & Li, Reference Patel, Terjesen and Li2012). These arguments collectively indicate that technology-driven exploitation is critical in transforming external innovation pressures into tangible operational innovations. Therefore, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 1: Technological investments mediate the relationship between innovation pressure and operational innovation.

The mediating effect of human capital utilization

Effectively addressing innovation pressure requires organisations not only to invest in tangible technological assets but also to leverage the creative and problem-solving capacities of their human capital (Raisch & Fomina, Reference Raisch and Fomina2025). Human capital, defined broadly as the aggregation of knowledge, skills, and cognitive capabilities possessed by employees (Becker, Reference Becker1964; Ployhart & Moliterno, Reference Ployhart and Moliterno2011), represents a vital resource enabling firms to navigate the uncertainties and complexities associated with innovation-driven market environments (Campbell, Coff, & Kryscynski, Reference Campbell, Coff and Kryscynski2012; Crook, Todd, Combs, Woehr, & Ketchen, Reference Crook, Todd, Combs, Woehr and Ketchen2011). Central to human capital theory is the premise that employees’ specialised skills, cognitive flexibility, and experiential knowledge fundamentally shape a firm’s ability to adapt, reorganise, and enhance its operational routines (Fonseca, Faria, & Lima, Reference Fonseca, Faria and Lima2019; Ployhart, Reference Ployhart2021).

Under conditions of substantial innovation pressure, the importance of human capital becomes particularly important, as employees are often required to depart from traditional and routine-based thinking to develop novel, unconventional approaches to existing operational challenges (Marvel, Davis, & Sproul, Reference Marvel, Davis and Sproul2016). Employees with well-developed capabilities for creativity and paradoxical thinking provide a cognitive advantage to firms, enabling the simultaneous exploration of new ideas and exploitation of established practices, characteristics central to ambidextrous organisational strategies (Raisch & Birkinshaw, Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008; Varandas et al., Reference Varandas, Fernandes and Veiga2024). Such cognitive agility allows firms not only to swiftly recognise emerging opportunities but also to recombine existing knowledge in innovative ways, thereby transforming operational pressures into opportunities for strategic renewal and continuous improvement (Kostopoulos, Bozionelos, & Syrigos, Reference Kostopoulos, Bozionelos and Syrigos2015).

Moreover, empirical research has underscored that leveraging human capital facilitates organisational learning, innovation diffusion, and the effective management of operational complexities (Fernández Campos, Trucco, & Huaccho Huatuco, Reference Fernández Campos, Trucco and Huaccho Huatuco2019; Jantunen, Tarkiainen, Chari, & Oghazi, Reference Jantunen, Tarkiainen, Chari and Oghazi2018). For instance, firms with strong human capital are better positioned to cultivate diverse mental models, enhancing their ability to perceive operational constraints not merely as limitations but as platforms for innovative problem-solving and opportunity development (Marvel et al., Reference Marvel, Davis and Sproul2016). Indeed, such cognitive diversity has consistently been linked to superior innovation performance due to enhanced organisational responsiveness, adaptability, and capability to address paradoxical operational challenges (Aggarwal & Woolley, Reference Aggarwal and Woolley2019; Lin, McDonough, Yang, & Wang, Reference Lin, McDonough, Yang and Wang2017).

However, it is important to recognise that the mere presence of skilled employees does not automatically translate into operational innovation. Rather, firms must actively facilitate human capital utilisation through structured knowledge-sharing practices, supportive organisational cultures, and leadership strategies designed explicitly to encourage exploration, experimentation, and creative risk-taking (Arts & Fleming, Reference Arts and Fleming2018; Jansen, van den Bosch, & Volberda, Reference Jansen, van den Bosch and Volberda2006; Lin et al., Reference Lin, McDonough, Yang and Wang2017). These supportive organisational mechanisms enable the full activation of employees’ innovative potential, converting latent cognitive capabilities into actionable operational improvements (Lee, Swink, & Pandejpong, Reference Lee, Swink and Pandejpong2011; Marvel et al., Reference Marvel, Davis and Sproul2016).

Collectively, these arguments establish the critical mediating role played by human capital utilisation in transforming external innovation pressures into tangible operational innovations. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Human capital utilization positively mediates the relationship between innovation pressure and operational innovation.

The moderated mediation of firm size

The capacity of firms to balance the operational trade-off between efficiency and flexibility is significantly influenced by their organisational scale and resource availability (Iborra et al., Reference Iborra, Safón and Dolz2020). Larger firms often have greater resource slack and structural flexibility, enabling them to more effectively manage competing operational demands through structurally differentiated units or distinct organisational processes that separately pursue exploitation and exploration (Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling, & Veiga, Reference Lubatkin, Simsek, Ling and Veiga2006; Simsek, Reference Simsek2009). In contrast, SMEs typically face pronounced resource constraints that limit their ability to simultaneously pursue ambidextrous strategies, as these strategies demand substantial managerial attention, administrative complexity, and dedicated resources for coordination and integration (Choi, Ha, & Kim, Reference Choi, Ha and Kim2022; Yang & Aldrich, Reference Yang and Aldrich2017).

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that SMEs are constrained not only by financial resources but also by limited managerial bandwidth, organisational structures, and specialised expertise necessary to manage the complexity inherent in ambidextrous strategies (Voss & Voss, Reference Voss and Voss2013; Wenke et al., Reference Wenke, Zapkau and Schwens2021). SMEs, due to their inherently lean organisational structures and resource bases, frequently face challenges in simultaneously maintaining dual innovation pathways, as the structural separation needed to effectively isolate these distinct strategies is often infeasible (Felício, Caldeirinha, & Dutra, Reference Felício, Caldeirinha and Dutra2019). Consequently, SMEs may either explicitly or implicitly prioritise one strategic orientation over another, thus limiting their potential benefits from ambidexterity.

Furthermore, SMEs typically operate within tightly integrated organisational systems, making the simultaneous pursuit of contradictory innovation goals, such as efficiency-driven technological exploitation versus human-capital-driven exploratory innovation, particularly challenging (Ebben & Johnson, Reference Ebben and Johnson2005; Heavey, Simsek, & Fox, Reference Heavey, Simsek and Fox2015; Simsek, Heavey, Veiga, & Souder, Reference Simsek, Heavey, Veiga and Souder2009). This integrated structure implies that investments in either technology or human capital are likely to consume a disproportionately large portion of the available organisational resources, leaving limited flexibility or capacity to pursue both simultaneously. Consequently, SMEs must carefully evaluate and selectively commit their resources toward either technology investments or human capital development based on specific contextual priorities and competitive pressures, rather than achieving a balanced pursuit of both strategies (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Dou and You2023; Iborra et al., Reference Iborra, Safón and Dolz2020).

However, despite these inherent limitations, SMEs may still effectively respond to innovation pressures by strategically concentrating resources on either technological advancements (exploitation) or enhancing human capital (exploration). SMEs can, thus, achieve substantial incremental innovation outcomes, although their gains from comprehensive ambidextrous strategies remain comparatively constrained (Felício et al., Reference Felício, Caldeirinha and Dutra2019). Prior studies have indeed shown that focused investment in either technology or human capital independently generates meaningful operational innovations even under conditions of constrained resources (Clercq et al., Reference Clercq, Thongpapanl and Dimov2014; Wenke et al., Reference Wenke, Zapkau and Schwens2021).

Considering the resource and structural constraints that disproportionately affect SMEs, it is reasonable to expect firm size to moderate the relationships between innovation pressures and strategic responses. Specifically, the effectiveness of strategic responses to innovation pressures through technology investment or human capital utilisation will vary depending on the size-related resource availability of firms. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: Firm size negatively moderates the relationships between innovation pressure and: (a) technological investment (exploitation), and (b) human capital utilization (exploration). Specifically, smaller firms experience greater constraints, reducing their ability to effectively leverage innovation pressure into operational innovations through simultaneous technology and human capital investments.

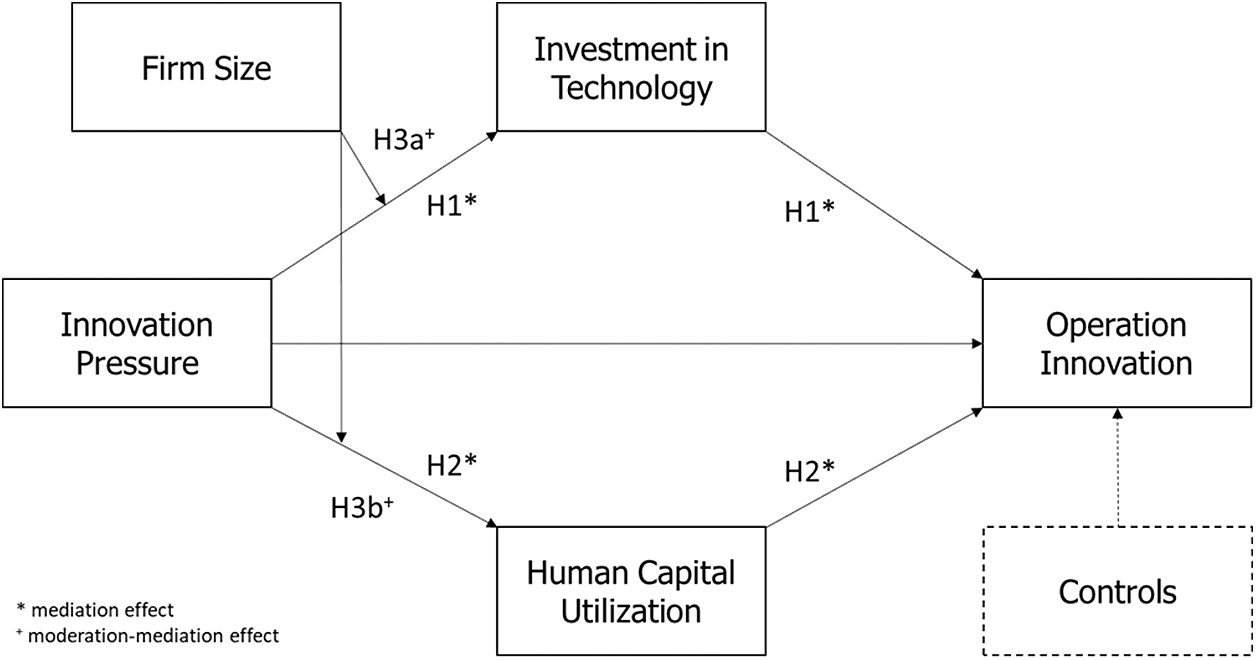

Building on this logic, we propose that innovation pressure has limited direct effects on operational innovation at he firm level and instead operates primarily through firms’ strategic responses, specifically, efforts to engage in exploration and exploitation. Figure 1 summarises this environment–action–performance model: pressures in the operating environment create the need for strategic action to sustain competitiveness, and firms may respond either through ambidextrous arrangements or by temporally separating conflicting activities (Roscoe & Blome, Reference Roscoe and Blome2019). Importantly, the viability of these responses is likely conditioned by organisational size and resource availability, which shape firms’ capacity to implement and sustain exploration and exploitation concurrently. The sections that follow develop the theoretical rationale and provide empirical tests of this mediated model.

Figure 1. Research model.

Method and analysis

Data, sampling strategy, and sample characteristics

Data and sampling strategy

We draw on data from the European Commission’s Flash Eurobarometer No. 433, which surveys European businesses regarding their innovation-related activities and attitudes (European Commission, [2016]). The 2016 cohort, our focal dataset, encompasses 14,117 firms, including 13,117 headquartered in the 28 EU member states and 500 each from Switzerland and the United States. To ensure comparability in operational processes, we restrict our analysis to 2,213 firms from European countries and Switzerland that are classified under NACE categories C (Manufacturing, n = 1,264), D (Electricity production, n = 61), E (Waste management and remediation, n = 101), and F (Construction, n = 787). The Flash Eurobarometer employs a standardised questionnaire designed to monitor yearly changes in how firms manage innovation, allocate investment for modernisation, and navigate barriers to commercialising innovation. Our sampling approach and operationalisation follow established procedures in prior studies that employ this dataset (Filippetti, Frenz, & Ietto-Gillies, Reference Filippetti, Frenz and Ietto-Gillies2011; Montresor & Vezzani, Reference Montresor and Vezzani2016), thereby ensuring both representativeness and comparability.

Sample characteristics

The resulting sample of 2,213 observations represents 16.3% of the 13,617 firms based in Europe and Switzerland. Consistent with the skewed size distribution of European firms towards SMEs, 39.0% of our sample reports between one and nine employees, while only 3.9% report more than 500 employees. At the time of data collection, 85.8% of firms had been in operation for more than 6 years; among the remainder, only 1.0% were in their first year of existence. In terms of 2015 turnover, 48.4% of firms reported revenues between €0.5 million and €10 million, whereas 19.4% reported revenues exceeding €10 million. Regarding recent growth dynamics (2013–2015), 11.9% of firms experienced revenue growth greater than 25%, 4.1% encountered a revenue decline exceeding 25%, and 31.4% maintained stable turnover. Geographically, 33.1% of firms operated solely in local markets, whereas 37.8% identified the EU as their primary trading arena. These distributions align closely with known EU-wide firm demographics in terms of size, age, turnover, and geographic orientation, indicating that our subsample remains broadly representative of the target population.

Method and research model

To evaluate the boundary conditions under which innovation pressure (‘PRESSURE’) stimulates operational innovation (‘OPERATION’), we employ a conditional process analysis (CPA) framework (Darlington & Hayes, Reference Darlington and Hayes2016; Hayes, Reference Hayes2018). CPA allows simultaneous estimation of mediation and moderation effects, capturing how PRESSURE influences OPERATION indirectly through two mediators, technological investments (‘TECHNOLOGY’) and human capital utilization (‘HUMAN’), and how these indirect pathways vary with firm size (‘SIZE’) as a moderator (Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020; Montoya & Hayes, Reference Montoya and Hayes2017; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007).

Specifically, we model OPERATION as a binary outcome (1 = successful introduction of operational innovation; 0 = otherwise) and therefore apply logistic regression for paths leading to OPERATION, while employing ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for paths from PRESSURE to each mediator. The direct effect of PRESSURE on OPERATION (path c′) is estimated via logistic regression. Then, we estimate two OLS equations for PRESSURE → TECHNOLOGY and PRESSURE → HUMAN (paths a₁ and a₂), followed by a logistic regression where TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN jointly predict OPERATION (paths b₁ and b₂). Firm size (SIZE) is included as a moderator on a₁ (PRESSURE → TECHNOLOGY) and a₂ (PRESSURE → HUMAN) paths to capture whether the firm’s scale strengthens or attenuates the extent to which pressure translates into resource commitments. We compute bootstrapped confidence intervals (10,000 resamples) for all indirect and conditional indirect effects. In line with prior research (Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020), CPA comprehensively captures the complex interplay of mediation and moderation, enabling us to quantify (1) the mediating roles of TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN, and (2) whether SIZE systematically alters these mediated pathways.

Measures and quality criteria

Operational innovation (dependent variable). OPERATION is constructed from the Flash Eurobarometer item asking whether the firm introduced ‘new or significantly improved processes’ over the period 2013–2016. The item explicitly covers production and distribution processes. OPERATION is coded 1 if the respondent answers affirmatively and 0 otherwise.

Innovation pressure (independent variable). PRESSURE is derived from the Flash Eurobarometer question in which respondents indicate motives for investing in innovation (multiple selections permitted). We retain two motives that capture market-based pressure: (a) ‘customer request’ and (b) ‘increased competition.’ Each motive is coded 1 if selected (0 otherwise). PRESSURE is coded 1 if at least one of the two motives is selected; otherwise, PRESSURE = 0.

Technology investment (mediator). TECHNOLOGY captures whether the firm reports using operationally relevant technologies in the survey. We code TECHNOLOGY = 1 if the firm selects one or more technology categories falling within: (a) sustainable production technologies, (b) IT-enabled intelligent manufacturing (e.g., big data, AI, blockchain), and/or (c) high-performance manufacturing systems. Firms that do not select any of these categories are coded TECHNOLOGY = 0.

Human Capital Utilisation (mediator). HUMAN captures whether the firm reports leveraging employee or managerial competencies for innovation. Based on Flash Eurobarometer items covering skill use, HUMAN is coded 1 if the firm indicates reliance on at least one of the following competency domains in its innovation activities: technical, organisational, creative, social, or marketing/finance. If none are indicated, HUMAN = 0.

Firm size (moderator). SIZE is measured as employee headcount (number of employees). For interaction analyses, SIZE is treated as a continuous variable and mean-centred before constructing the corresponding interaction terms.

Covariates

To isolate the effects of PRESSURE, TECHNOLOGY, HUMAN, and SIZE, we control for four clusters of covariates. Specifically, we include measures of perceived complexity (COMPLEXITY) and administrative constraints (ADMINISTRATION) involved in developing innovative solutions, as higher complexity can dampen ambidextrous efforts (Fernhaber & Patel, Reference Fernhaber and Patel2012). To capture resource availability, we control for access to external resources (RESOURCES) and investment capacity (INVESTMENT), acknowledging that financial and tangible resources facilitate or constrain innovation. We further include firm growth rate (GROWTH) and turnover (TURNOVER) to account for performance-related characteristics associated with firm size and structure that could influence innovation outcomes (Volery, Mueller, & Siemens, Reference Volery, Mueller and Siemens2015). Finally, we control for industry affiliation (INDUSTRY), recognizing industry-specific norms in ambidexterity, as well as firm formation history, whether the firm emerged via merger or acquisition (M&A), management buyout (BUYOUT), or belongs to a larger corporate group (GROUP), since past structural changes can shape current organizational capabilities (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009).

Construct reliability and validity

To establish measure validity and reliability, we conducted several assessment procedures. First, we performed exploratory factor analyses for items composing the composite indicators PRESSURE, TECHNOLOGY, and HUMAN. All items loaded above recommended thresholds, confirming unidimensionality. We then computed bias-corrected 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (10,000 resamples) for scale scores; results indicated stable estimates (see Table 1). At the construct level, we evaluated Cronbach’s alpha, examined multicollinearity (variance inflation factors, VIF), assessed composite reliability, and verified convergent validity (item loadings ≥ 0.70; average variance extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.50) (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt2015). The highest VIF observed was 1.71, well below the conventional cutoff of 10, indicating no multicollinearity concerns. All constructs achieved Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.70 and met the AVE criterion. Appendix A provides detailed correlations among constructs.

Table 1. Model fit criteria for market pressure, technology, and utilization of human capital

N = 2213; model fit (estimated model); max. iterations 300, stop criterion 7; weighting 1.0; χ2 = chi-square; NFI = Bentler-Bonett Index or Normed Fit Index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; Alpha = Cronbach’s alpha; AVE = average variance extracted; CR = composite reliability. Factor loadings and bootstrapped confidence intervals on the 95% level are: PRESSURE P1 (0.793a [0.062| 0.341]), P2 (0.761a [0.503| 0.691]), P3 (0.699b [0.154| 0.425]), P4 (0.831a [0.275| 0.534]), P5 (0.747a [–0.457|–0.170]); TECHNOLOGY T1 (0.733a [0.025|0.627]), T2 (0.678c [–0.638|–0.448]), T3 (0.801a [0.514 0.705]); HUMAN H1 (0.793a [0.611|0.765]), H2 (0.649c [0.046 |0.325]), H3 (0.676b [–0.020|0.670]), H4 (0.827a [0.518|0.710]), H5 (0.750a [0.618|0.773]), H6 (0.776a [0.610|0.769]), Marketing skills (0.682b [0.037|0.209]), H7 (0.711a [0.162|0.365]).

Finally, we tested the measurement models using chi-squared (χ2), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and normed fit index (NFI) (Cheung & Lau, Reference Cheung and Lau2017). Fit indices met recommended thresholds, confirming that our measurement models adequately represent the data.

Results

Direct effect

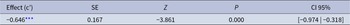

Our first analysis estimates the direct effect of PRESSURE on OPERATION (path c′). Table 2 reports path coefficients from logistic regression, alongside bootstrapped confidence intervals, standard errors, and z-statistics. Contrary to a straightforward ‘pressure yields innovation’ hypothesis, we find a significant negative direct effect (c′ = –0.646, SE = 0.167, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.974, –0.318]). Bootstrapping (10,000 resamples) confirms the robustness of this finding. This counterintuitive negative association suggests that, in isolation, increased innovation pressure may impede the successful introduction of operational innovations. Although our theoretical model does not posit this direct negative linkage, we note its potential importance for both scholars and managers and return to its implications in the Discussion.

Table 2. Direct effect of innovation pressure on operation innovation

N = 2,213.

*** indicates statistical significance at the 1%-level.

Number of bootstrap samples for bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was 10,000.

Mediating effects

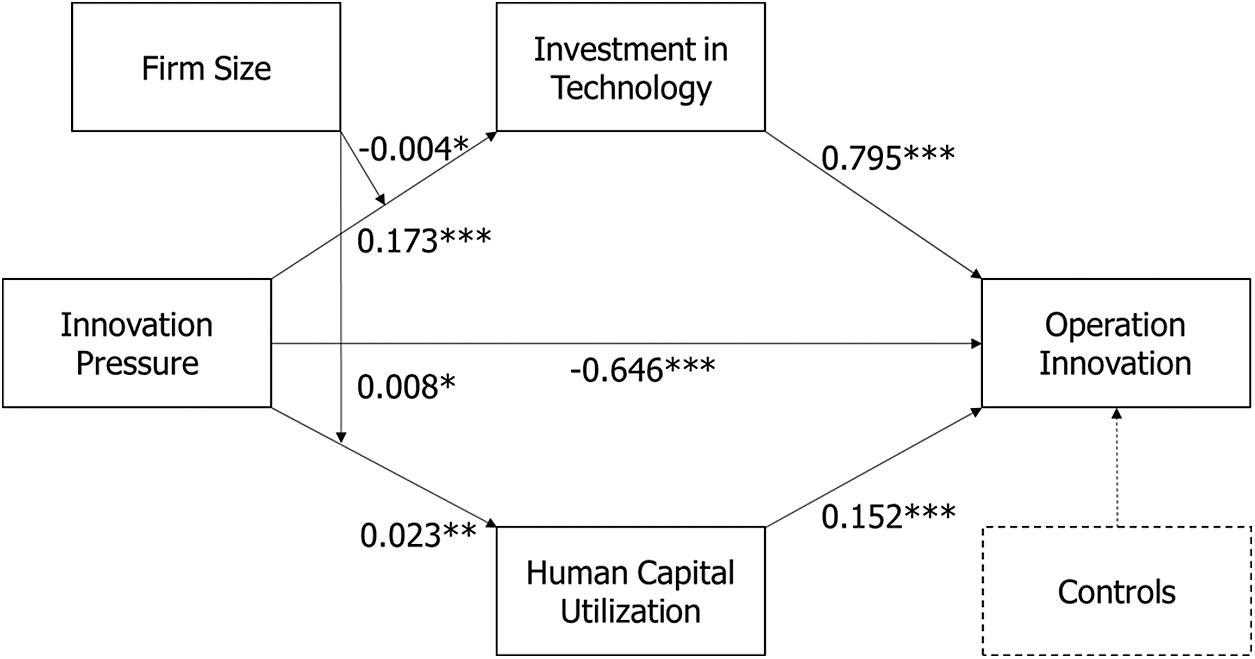

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, we implemented a simple mediation framework in which PRESSURE → TECHNOLOGY and PRESSURE → HUMAN are estimated via OLS, and TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN → OPERATION are jointly estimated via logistic regression. Table 3 presents R2 values, path coefficients, bootstrapped 95% CIs, standard errors, and t-statistics for the OLS models predicting TECHNOLOGY (R2 = 0.141) and HUMAN (R2 = 0.224). We observe that PRESSURE positively predicts TECHNOLOGY (β = 0.173, SE = 0.006, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.162, 0.184]) and HUMAN (β = 0.023, SE = 0.011, p < 0.005, 95% CI [0.002, 0.044]). Bootstrapped intervals confirm that these effects are both statistically significant and substantively meaningful, indicating that firms under competitive or customer-driven pressure increase investments in both technological solutions and human capital.

Table 3. Unstandardized OLS regression coefficients with confidence intervals estimating moderated mediation effects of INNOVATION PRESSURE on TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN

Notes:

***,**,* Indicates statistical significance at the 1%-, 5%-, 10%-level, respectively; n.s. indicates non-significant results.

SE = standard error.

Number of bootstrap samples for bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was 10,000.

Next, Table 4 reports the logistic regression for OPERATION (reported via –2 log-likelihood [–2LL], Cox & Snell R2, Nagelkerke R2, bootstrapped CIs, standard errors, and z-statistics). Both TECHNOLOGY (β = 0.795, SE = 0.208, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.203, 0.387]) and HUMAN (β = 0.152, SE = 0.320, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.529, 0.779]) positively and significantly predict OPERATION. Notably, the effect of TECHNOLOGY on OPERATION is substantially larger than that of HUMAN. Model fit improves significantly over the null model (Δ–2LL, p < 0.001), and both Cox & Snell R2 (0.076) and Nagelkerke R2 (0.094) indicate modest explanatory power. Together, these findings confirm that while both mediators transmit part of the effect of PRESSURE, technological investments exert a stronger influence on operational innovation outcomes than does human capital utilisation.

Table 4. Logistic regression coefficients with confidence intervals estimating effects from TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN on operation innovation

Notes:

***,**,* Indicates statistical significance at the 1%-, 5%-, 10%-level, respectively. n.s. indicates non-significant results.

SE = standard error. − 2LL = log likelihood. CoxSnel = Cox & Snell pseudo R2. Nagelkrk = Nagelkerke pseudo R2.

Number of bootstrap samples for bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was 10,000.

Conditional effects (moderated mediation)

We next examined whether SIZE moderates the a-paths (PRESSURE → TECHNOLOGY and PRESSURE → HUMAN), producing conditional indirect effects of PRESSURE on OPERATION via each mediator. Table 5 reports indices of moderated mediation: the TECHNOLOGY pathway is significantly moderated by SIZE (index = –0.014, boot SE = 0.011, 95% CI [–0.036, –0.006]), whereas the HUMAN pathway shows a positive moderation effect (index = 0.005, boot SE = 0.003, 95% CI [0.000, 0.013]). In other words, larger firms are more adept at translating pressure into technological investments that yield operational innovation, whereas smaller firms rely relatively more on human capital.

Table 5. Index of moderated mediation of structure

N = 2,213. Number of bootstrap samples for bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals was 10,000.

To probe these interactions further, we applied the ‘pick-a-point’ approach at ± 1 SD of SIZE (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018; Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020). Table 6 presents conditional indirect effects of PRESSURE on OPERATION via TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN at low (–1 SD), mean, and high (+1 SD) values of SIZE. For TECHNOLOGY, the indirect effect is negative at low SIZE, nonsignificant at mean SIZE, and positive at high SIZE, indicating that only larger firms effectively leverage technological investments in response to pressure. For HUMAN, the indirect effect is positive across all levels of SIZE and becomes stronger for smaller firms, confirming Hypothesis 2. Figure 2 graphically depicts these conditional indirect effects. Finally, Figure 3 illustrates our full moderated mediation model, annotating path coefficients and significance levels.

Figure 2. Conditional indirect effects of SIZE on TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN using a pick-a-point approach with ω +/ −1 S.D for the moderators.

Figure 3. Statistical model.

Table 6. Conditional indirect effects of SIZE on TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN at three values of the moderators

N = 2,213.

Values for quantitative moderators are the mean and plus/minus one standard deviation from the mean.

Discussion and contribution

Our findings offer three interconnected contributions to research on organisational ambidexterity, innovation pressure, and firm heterogeneity. First, we challenge the prevailing assumption that external pressure uniformly spurs innovation by revealing its potential ‘dark side.’ Second, using a mediated-moderation framework, we reconceptualise ambidexterity, showing how distinct pathways jointly shape outcomes under pressure. Third, we establish firm size as a boundary condition that governs the effectiveness of ambidextrous strategies.

The dark side of innovation pressure

Market pressure can depress, rather than catalyse, operational innovation because it fails to translate urgency into the slack, coordination, and prioritisation required for structured investment. Pressure compresses decision time, strains routines, and fuels priority churn, pushing organisations toward reactive fixes and local exploitation instead of deliberate capability building. This translation failure, heightened sensing without the means to seize and transform, explains the negative direct effect of pressure on operational innovation we theorise and observe. It is consistent with evidence that fear and urgency narrow managerial attention and distort decision processes (Vuori & Huy, Reference Vuori and Huy2016), resonates with accounts of unintended harms from innovation pressure (Heidenreich, Freisinger, & Landau, Reference Heidenreich, Freisinger and Landau2022; Peters & Buijs, Reference Peters and Buijs2022), and aligns with meta-analytic findings that high time pressure undermines complex work outcomes (Mazzola & Disselhorst, Reference Mazzola and Disselhorst2019).

The dark side effect is strongest when operational slack is low and portfolio governance is weak, conditions that make firefighting the default response. Resource buffers and governance discipline mitigate this damage by protecting improvement work from short-term disruptions and enabling preplanned, deliberate reallocations (Du, Kim, Fourné, & Wang, Reference Du, Kim, Fourné and Wang2022). Centring the translation problem shifts the debate from whether pressure spurs innovation to how it is metabolised inside the firm, and it identifies actionable levers, slack, governance, and deliberate resource shifts that prevent pressure from eroding operational innovation. In doing so, we extend the literature on the dark side of innovation pressure (Gabler, Ogilvie, Rapp, & Bachrach, Reference Gabler, Ogilvie, Rapp and Bachrach2017; Peters & Buijs, Reference Peters and Buijs2022) and refine dynamic capabilities theory: sensing competitive threats does not guarantee effective seizing and transforming unless firms possess the capacity to marshal resources deliberately (Randhawa, Wilden, & Gudergan, Reference Randhawa, Wilden and Gudergan2021).

A mediated–moderation framework

We further propose a mediated–moderation framework to refine ambidexterity theory by specifying divergent pathways, technological investments versus human capital utilisation, through which pressure translates into operational innovation. Although antecedent studies have posited that exploration and exploitation can coexist along a continuum (Voss & Voss, Reference Voss and Voss2013; Wenke et al., Reference Wenke, Zapkau and Schwens2021), our evidence reveals that these pathways operate as distinct mechanisms whose efficacy is contingent on firm size. Large firms, endowed with ample slack resources and organisational architectures, more effectively convert pressure into capital–intensive technological deployments that yield immediate operational improvements. In contrast, smaller firms rely disproportionately on human-centric routines, creative recombination of existing capabilities to achieve incremental operational gains (Bag et al., Reference Bag, Rahman, Sharma, Chiarini, Srivastava and Gupta2025). By disaggregating ambidexterity into discrete, size–dependent processes, our work extends the ‘contextual ambidexterity’ framework (Birkinshaw, Zimmermann, & Raisch, Reference Birkinshaw, Zimmermann and Raisch2016; Gibson & Birkinshaw, Reference Gibson and Birkinshaw2004) by illustrating that context not only moderates the degree of simultaneous alignment but also fundamentally alters the choice architecture of exploration versus exploitation. In doing so, we integrate literature on microfoundations of dynamic capabilities (Eisenhardt & Martin, Reference Eisenhardt and Martin2000; Helfat, Reference Helfat2022), showing that SMEs often circumvent structural impediments to ambidexterity via micro–level practices (e.g., cross–functional problem–solving, informal knowledge sharing) that large firms embed within formal R&D and IT systems (Volberda, Khanagha, Baden-Fuller, Mihalache, & Birkinshaw, Reference Volberda, Khanagha, Baden-Fuller, Mihalache and Birkinshaw2021).

Firm size as a boundary condition

Third, our demonstration that the conditional indirect effects vary by firm size contributes to resource–based and contingency theories by identifying firm size as a critical boundary condition shaping the fitness of ambidextrous strategies. Prior work has noted that liabilities of smallness (Lefebvre, Reference Lefebvre2022; Vakulenko, Reference Vakulenko2021) impede simultaneous exploration and exploitation, but few studies have empirically delineated how SMEs realign resource portfolios under innovation pressure. Our findings show that, because smaller firms lack the resource slack to pursue capital–intensive technological upgrades, they lean more heavily on human capital as a bridging mechanism, validating recent theorising on sequential ambidexterity (Evers & Andersson, Reference Evers and Andersson2021; Sun, Rong, Sun, & Zhu, Reference Sun, Rong, Sun and Zhu2023), where resource–constrained firms oscillate between exploration and exploitation in response to environmental jolts. By contrast, larger firms benefit from ‘structural ambidexterity’ (O’Reilly & Tushman, Reference O’Reilly and Tushman2008), as their scale enables parallel investments. In synthesising these perspectives, we propose a contingent ambidexterity model that unifies structural, contextual, and sequential approaches, contingent on firm size and resource endowments (Tarba, Jansen, Mom, Raisch, & Lawton, Reference Tarba, Jansen, Mom, Raisch and Lawton2020).

Limitations

Several limitations warrant attention. First, our temporal window (2013–2016) restricts insights into the long-term consequences of investing in operational technologies. Path dependencies introduced by early technology adoption may yield adverse outcomes beyond our study horizon (e.g., obsolescence or misalignment with evolving market trends). Second, our analyses draw on Eurobarometer data, which, like most large-scale surveys, rely on self-reported responses. Self-reports can be affected by social desirability, recall error, and transient response styles, introducing measurement noise and potential bias. This limitation is common in survey-based management research and, while generally accepted, warrants explicit recognition. Several features of our design mitigate these concerns: Eurobarometer employs standardised instruments with harmonised administration and nationally representative probability samples with weights; we align measures with established constructs; and our models include rich controls as well as country- and year-fixed effects. Importantly, any remaining idiosyncratic response error should tend to attenuate relationships rather than inflate them, rendering our estimates conservative. Third, our assumption of linear relationships among PRESSURE, TECHNOLOGY, HUMAN, and OPERATION may mask more complex, nonlinear dynamics. For instance, threshold effects may exist whereby only a critical mass of technological or human-capital investment yields discernible operational improvements. Fourth, although our binary coding of TECHNOLOGY and HUMAN simplifies analysis and interpretation, it cannot capture variation in investment intensity or the depth of capability development. Future research could (a) extend the temporal window to track persistence and decay of effects, (b) triangulate survey indicators with behavioural or administrative data and leverage multi-source or temporally separated measures, and (c) employ flexible functional forms and continuous or latent constructs to capture the richness of ambidextrous resource allocation.

Practical implications and further research

Future research should shift from asking whether market pressure stimulates innovation to examining how pressure is metabolised inside firms. Our evidence of a ‘dark side’ implies that compressed decision cycles, attentional narrowing, and firefighting can depress capability building even when external signals are strong. Scholars should unpack these micro–mechanisms and test whether modest ‘micro-slack’ and lightweight portfolio governance convert urgency into disciplined improvement. Process-oriented designs, experience sampling of managerial priorities, process mining of backlogs, and digital traces from workflow systems can identify mediators such as priority churn and routine strain.

Our mediated–moderation framework calls for head-to-head comparisons of technology-intensive deployment versus human-centric recombination as distinct pathways linking pressure to operations. Rather than treating exploration and exploitation as a continuum, future studies should estimate when the pathways substitute (under tight constraints) or complement (at scale). Panel/event-study designs can trace sequence payoffs (human-first vs. technology-first); measures of cross-functional problem-solving density and automation intensity can illuminate microfoundations.

Establishing firm size as a boundary condition opens a broader heterogeneity agenda. Work should examine how ownership, capital access, and internal labour markets shape the choice architecture of ambidexterity, and probe nonlinear thresholds where parallelism flips from duplication to increasing returns. Cross-industry comparisons can test whether clockspeed tilts firms toward sequencing or parallelism.

Stronger identification and richer measurement are essential: extend temporal windows to capture path dependence, move from binary indicators to intensity/depth, and triangulate surveys with administrative and behavioural data. Field experiments that vary slack, WIP limits, or governance cadence, and shock-based natural experiments, can reveal how organisational metabolism turns pressure into operational renewal. Finally, tractable interventions (freeze windows, micro-budgets, AI problem-solving tools) can distinguish when sequencing or parallelism creates the greatest, and most sustainable, innovation gains.

Finally, by capturing the interplay among pressure, resource allocation, and firm size within a single CPA framework, we advance methodological rigour in ambidexterity research. While prior studies have largely relied on cross–sectional designs or simplistic interaction models, our moderated–mediation approach quantifies how indirect effects morph across size strata, highlighting the multistage process through which pressure is internalised and translated into innovation outcomes (Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020; Montoya & Hayes, Reference Montoya and Hayes2017). This methodological precision uncovers paradoxical patterns, such as the negative direct relationship between innovation pressure and operational innovation, that would remain obscured under conventional regression analyses. We encourage future researchers to adopt similar process–oriented models when investigating ambidexterity and innovation contingencies, particularly in industry contexts characterised by rapid digitalisation and resource volatility.

Appendix A: Correlations among constructs

Note:

**,* indicates statistical significance at the 5%-, 10%-level.