-

Women using drospirenone and ethinyl oestradiol oral contraceptives were associated with lower performance in verbal memory and visuospatial tasks compared to naturally cycling women.

-

Higher performance in cognitive inhibition was observed in anti-androgenic combined oral contraceptive users, suggesting a potential differential association in executive control processes under endogenous hormonal suppression.

-

The findings contribute to a growing body of evidence indicating that combined oral contraceptive use may differentially affect specific cognitive domains in women of reproductive age.

-

The study did not include direct neurobiological measures or hormone level assays, which limits the ability to establish causal neural mechanisms. Similarly, other non-hormonal variables that influence cognitive performance, such as cognitive strategies, mood, intelligence, personality or culture, were not assessed.

-

The sample size, while adequate for detecting large effects, may not capture more subtle cognitive differences or interactions.

Introduction

According to the United Nations, hormonal oral contraception is one of the most widely used contraceptive methods, with approximately 151 million women of reproductive age using it worldwide (United Nations, 2019). Within this category, the combined oral contraceptives (COC) represent a major formulation. COC typically consist of a synthetic progestogen (progestin), such as drospirenone (DRSP), combined with a synthetic oestrogen, specifically ethinylestradiol (EE). They are prescribed not only for birth control but also for managing menstrual or menopausal symptoms and for treating conditions like acne (Davison et al., Reference Davison, Bell, Robinson, Jane, Leech, Maruff, Egan and Davis2013; Brynhildsen, Reference Brynhildsen2014). The contraceptive action of DRSP/EE is achieved by suppressing gonadotropin release from the hypothalamus, thereby inhibiting ovarian stimulation and follicular maturation, and maintaining low levels of endogenous oestradiol and progesterone (Bachmann & Kopacz, Reference Bachmann and Kopacz2009; Duffy & Archer, Reference Duffy, Archer and Skinner2018). Synthetic progesterone and synthetic oestrogen exhibit biological effects similar to their natural counterparts by binding to and activating intracellular progesterone and oestrogen receptors. These receptors are widely expressed in key brain regions, including the hippocampus, frontal cortex and hypothalamus, and in major endocrine glands such as the pituitary gland and adrenal glands – areas whose hormonal output further influences brain function (Brinton et al., Reference Brinton, Thompson, Foy, Baudry, Wang, Finch, Morgan, Pike, Mack, Stanczyk and Nilsen2008; Weiser et al., Reference Weiser, Foradori and Handa2008; Lagunas et al., Reference Lagunas, Fernandez-Garcia, Blanco, Ballesta, Carrillo, Arevalo, Collado, Pinos and Grassi2022; Pletzer et al., Reference Pletzer, Winkler-Crepaz and Maria Hillerer2023). A crucial factor in the brain and cognitive impact of COC stems from the pharmacological diversity among progestins, which differ in their interactions with neuronal receptors and neurotransmitter systems, potentially leading to distinct emotional and cognitive outcomes (Griksiene et al., Reference Griksiene, Monciunskaite and Ruksenas2022; Pletzer et al., Reference Pletzer, Winkler-Crepaz and Maria Hillerer2023; Bencker et al., Reference Bencker, Gschwandtner, Nayman, Grikšienė, Nguyen, Nater, Guennoun, Sundström-Poromaa, Pletzer, Bixo and Comasco2025). In that regard, preclinical data in animal models, showed that medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethindrone acetate (NETA) and segesterone-acetate (SGA) impair spatial learning and memory, while levonorgestrel (LEVO) enhances performance (Braden et al., Reference Braden, Andrews, Acosta, Mennenga, Lavery and Bimonte-Nelson2017; Bernaud et al., Reference Bernaud, Koebele, Northup-Smith, Willeman, Barker, Schatzki-Lumpkin, Sanchez and Bimonte-Nelson2023). Furthermore, neurogenesis and neuroprotection are increased by LEVO treatment, whereas MPA decreases both (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhao, She, Chen, Wang, Wong, McClure, Sitruk-Ware and Brinton2010; Jayaraman & Pike, Reference Jayaraman and Pike2014). Evidence regarding the cognitive associations of EE alone is limited and inconclusive with outcomes potentially mediated by dose and hormonal status. For instance, high-dose EE treatment has been shown to impair spatial memory in female ovariectomized rats, possibly by reducing basal forebrain cholinergic cells (Mennenga et al., Reference Mennenga, Gerson, Koebele, Kingston, Tsang, Engler-Chiurazzi, Baxter and Bimonte-Nelson2015). Conversely, high-dose EE increased performance in novel object recognition tasks in intact female rats, and low-dose of EE reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus (Simone et al., Reference Simone, Bogue, Bhatti, Day, Farr, Grossman and Holmes2015). There are currently no studies in human females evaluating the isolated cognitive associations of DRSP or EE; their associations have only been measured in COC formulations. Regardless, the overall cognitive associations of COC remain unclear, with studies reporting positive, negative, or neutral outcomes depending on factors such as progestin type, dosage, age and the specific cognitive tasks assessed (Gurvich et al., Reference Gurvich, Nicholls, Lavale and Kulkarni2023). Specifically in human females, an early study found no differences in domains like memory, attention, visuospatial ability or language between COC users and naturally cycling women assessed in the mid-luteal phase (LP) (Gogos, Reference Gogos2013); but this study did not account for the crucial pharmacological differences among progestins. However, subsequent research has suggested this distinction is critical: when COC users were separated by progestin type, users of androgenic COC (e.g., LEVO) exhibited higher performance in visuospatial ability compared to users of anti-androgenic COC (e.g., DRSP) (Gurvich et al., Reference Gurvich, Warren, Worsley, Hudaib, Thomas and Kulkarni2020). Preclinical evidence on DRSP further highlights the complexity of the combined formulation. In ovariectomized rats, DRSP administered alone (at low, medium and high doses) increased performance in working memory tasks compared with controls. Furthermore, a moderate, dose-dependent improvement was observed in spatial memory tasks following treatment with medium and high doses (Koebele et al., Reference Koebele, Poisson, Palmer, Berns-Leone, Northup-Smith, Pena, Strouse, Bulen, Patel, Croft and Bimonte-Nelson2022). However, this beneficial effect on spatial memory was reversed when DRSP was co-administered with EE, an outcome potentially linked to the increased expression of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) observed in the perirhinal cortex following EE administration (Koebele et al., Reference Koebele, Poisson, Palmer, Berns-Leone, Northup-Smith, Pena, Strouse, Bulen, Patel, Croft and Bimonte-Nelson2022).

Given that DRSP/EE is one of the most frequently prescribed progestin combinations in COC (Boehnke et al., Reference Boehnke, Franke, Bauerfeind, Heinemann, Kolberg-Liedtke and Koelkebeck2024), and that the current evidence suggests an association between COC use and hippocampus-related tasks contingent on progestin type and dose, a critical knowledge gap remains. To date, few studies have specifically focused on the cognitive associations of DRSP/EE in women of reproductive age, often grouping this formulation with other COC. This study aims to contribute to the existing evidence by evaluating four cognitive domains – verbal memory, language fluency, visuospatial ability and cognitive inhibition – in women using DRSP/EE compared to naturally cycling assessed during the LP, when endogenous ovarian hormone levels are at their natural peak. Verbal memory and visuospatial abilities have been linked to hippocampus function (Bonner-Jackson et al., Reference Bonner-Jackson, Mahmoud, Miller and Banks2015; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Dong and Zhou2016); cognitive inhibition has been associated with the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and right cerebellum activity (Okayasu et al., Reference Okayasu, Inukai, Tanaka, Tsumura, Shintaki, Takeda, Nakahara and Jimura2023); and language fluency with activity in frontal and temporal lobes (Birn et al., Reference Birn, Kenworthy, Case, Caravella, Jones, Bandettini and Martin2010). Based on preclinical and clinical evidence suggesting a differential association for anti-androgenic progestins and potential negative outcomes for hippocampus-related function, we hypothesised that DRSP/EE use would be associated with significantly lower performance on hippocampus-dependent tasks (verbal memory and visuospatial ability), but would show no significant differences in performance on non-hippocampus-dependent tasks (cognitive inhibition and language fluency) compared to the naturally cycling group.

Material and methods

Participants

The study initially evaluated 60 women aged between 18 and 35 years, all fluent in Spanish. All participants met the following general exclusion criteria: a history of neuropsychiatric, neurological or endocrine disorders; sensory impairments; current pregnancy or breastfeeding within the past 12 months and the use of any non-contraceptive medication. Inclusion criteria for the naturally cycling group required regular menstrual cycles (average length of 28–32 days). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final sample comprised 48 participants: 23 using COC and 25 naturally cycling women. These naturally cycling women were evaluated during LP (menstrual cycle days 18 to 28), which was individually determined based on the forward and backward counts from the start days of both the preceding and subsequent menstrual cycles (Schmalenberger et al., Reference Schmalenberger, Tauseef, Barone, Owens, Lieberman, Jarczok, Girdler, Kiesner, Ditzen and Eisenlohr-Moul2021). This procedure resulted in the majority of participants being assessed during the mid-LP (n = 22, 88%, defined as day −9 to −5 before menstrual onset) and a smaller proportion during the late-LP (n = 3, 12%, defined as day -2 to -4 before menstrual onset). Participants in the COC group were assessed during the active pill intake phase (cycle days 5 to 21). COC users were required to have been consistently using a COC containing 3 mg of DRSP and either 20 micrograms of EE (69.6% of the group) or 30 micrograms of EE (30.4% of the group) for a minimum of three consecutive months. The exact duration of treatment was not further quantified. There were no significant differences found between groups regarding key demographic variables: age (COC = 21.7 ± 3.1; LP = 23.2 ± 3.5), years of education (COC = 15.6 ± 1.5; LP = 15.6 ± 1.2) or socioeconomic status (COC = 4 ± 1; LP = 4.2 ± 1.3). A sensitivity power analysis was performed using G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) to determine the minimum effect size the study was adequately powered to detect. For a two-tailed independent-samples t-test with an α of 0.0125 and a desired power of 0.80, our sample sizes (COC = 23 and LP = 25) were sufficient to detect a minimum effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.9, indicating the study was designed to reliably detect effects in the large range (Cohen, Reference Cohen1992).

Cognitive assessment

Verbal memory: The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) is a validated measure of verbal learning and memory. Participants are read a list of 12 words (4 words from 3 semantic categories) across three acquisition trials. Primary outcome measures include total recall across the three trials, delayed recall (administered 20–25 minutes post-acquisition) and a Recognition Discrimination Index (Arango-Lasprilla et al., Reference Arango-Lasprilla, Rivera, Garza, Saracho, Rodríguez, Rodríguez-Agudelo, Aguayo, Schebela, Luna, Longoni, Martínez, Doyle, Ocampo-Barba, Galarza-del-Angel, Aliaga, Bringas, Esenarro, García-Egan, Perrin and Arango-Lasprilla2015). This domain is generally recognised as sensitive to gonadal hormone levels (Sultana et al., Reference Sultana, Islam and Davis2025).

Visuospatial ability: Non-verbal reasoning, mental rotation and visuospatial processing were assessed using the Visual Puzzles Subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV (WAIS-IV). This task requires participants to mentally manipulate and select the three pieces (from six response options) that correctly form a given target image; that requires to mentally rotate the candidate pieces to see if they fit and how they fit into the final figure. Scoring is based on both accuracy and time to completion (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2012). Performance on similar visuospatial tasks has been linked to circulating levels of testosterone and oestrogen (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Parekh and Hardiman2013).

Cognitive inhibition: The Stroop Colour and Word Test (SCWT) assesses processing speed, reading automation, inhibitory control and executive functioning. The SCWT involves three main conditions: (1) Word reading (reading colour names), (2) Colour naming (naming the ink colour), and (3) Interference (naming the ink colour when the word itself names a different colour). The interference coefficient derived from this test is a primary measure of cognitive flexibility and inhibition (Rodríguez Barreto et al., Reference Rodríguez Barreto, Pineda Roa and Pulido2016). The interference score (calculated from time and errors) has been specifically reported as susceptible to changes related to both exogenous oestrogen administration and endogenous progesterone levels (Krug et al., Reference Krug, Born and Rasch2006; Hidalgo-Lopez & Pletzer, Reference Hidalgo-Lopez and Pletzer2017).

Language fluency: The verbal fluency test requires participants to produce the maximum number of non-proper or non-derived words within a limited time, using either a pre-established letter (phonological fluency) or a specific category (semantic fluency) (Borkowski et al., Reference Borkowski, Benton and Spreen1967). For the present study, the phoneme ‘S’ and the category ‘fruits’ were administered. The internal reliability for the letter ‘S’ is robust (Cronbach’s α = 0.83) (Tombaugh, Reference Tombaugh1999). Differences in phonological fluency have previously been reported in relation to menstrual cycle phase and COC use (Griksiene and Ruksenas, Reference Griksiene and Ruksenas2011; Simić & Santini, Reference Simić and Santini2012).

General procedure

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. To ensure consistency in testing conditions, all participants were assessed using a standardised, fixed battery approach (Casaletto & Heaton, Reference Casaletto and Heaton2017), with standardised administration procedures applied across test order, session duration and time of day. Each participant was assessed in a single session, lasting at most 90 minutes, and administered by the same examiner. All assessments were conducted in the afternoon (between 2:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m.) in the following fixed sequence: (1) HVLT-R Trials 1–3; (2) Visual Puzzles Subtest of WAIS-IV; (3) SCWT; (4) HVLT-R - Delayed Recall and Recognition and (5) VFT. The entire battery was administered using validated, standardised versions.

Statistics

Shapiro–Wilk’s test was performed to evaluate normality and Levene’s test was used to assess the homogeneity of variances. Group differences were analysed using independent-samples t-tests, for those variables that met the normality principle and for those that did not meet this assumption the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used. The magnitude of differences was reported using Cohen’s d for the parametric tests (t-test), and the non-parametric effect size r (calculated as Z/N) for the rank-based tests (Mann–Whitney U test). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 30 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Significance levels are reported as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). To control for the Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) due to multiple comparisons across the three dependent variables, the Bonferroni correction was applied. The nominal alpha level was adjusted to α adj = 0.0125 (calculated as 0.05/4). P-values below this adjusted threshold were considered statistically significant. Data visualisation was performed using OriginPro 2023b (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Data in figures are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for parametric data, and median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data.

Results

COC use is associated with lower scores in verbal memory and visuospatial ability

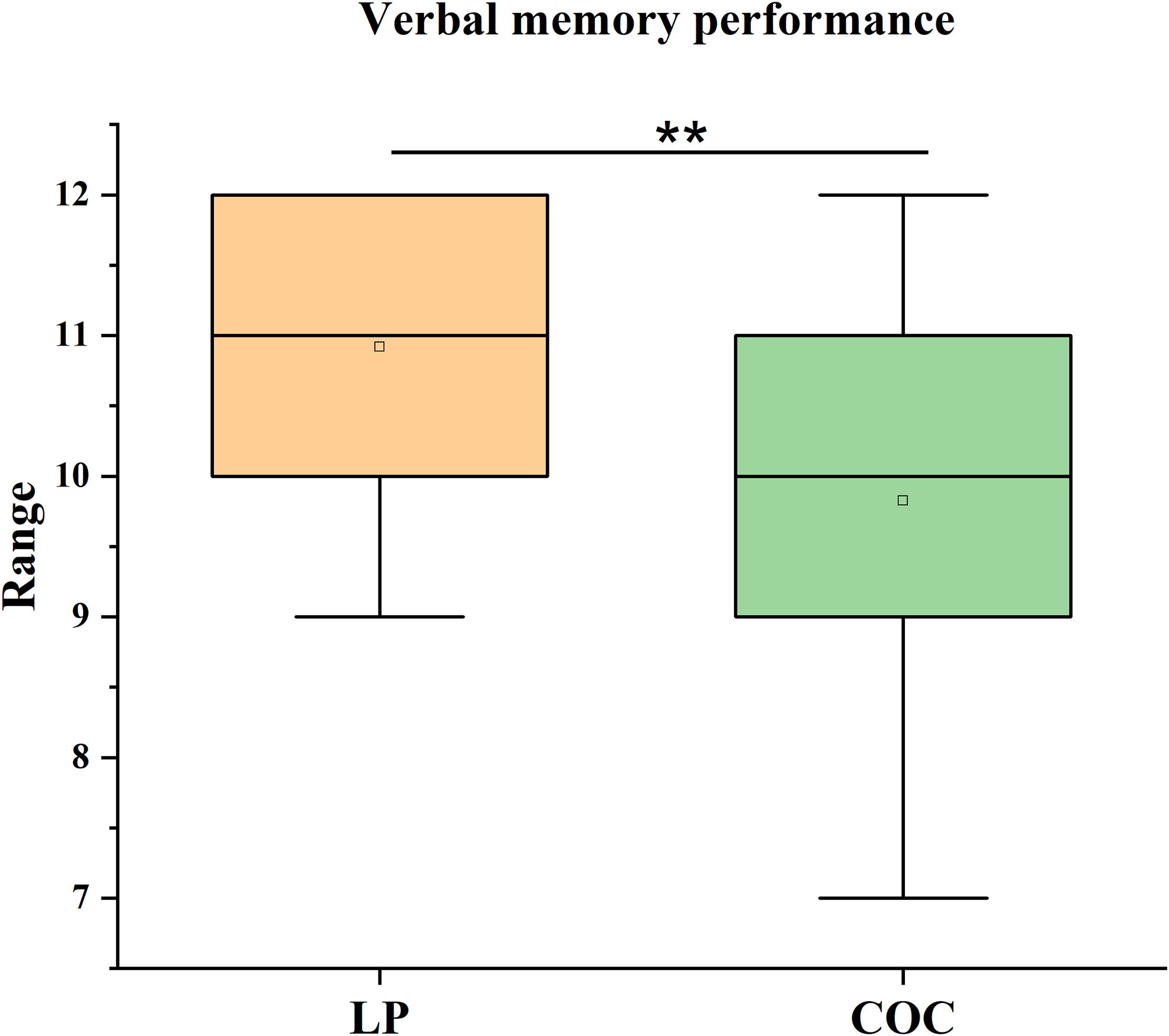

Statistical analysis revealed significant group differences in verbal memory performance, even after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (α adj = 0.0125). Specifically, LP group performed significantly higher on the recall condition of the HVLT-R than the COC group (U = 165, p = 0.009, r = 0.38). The effect size was medium. The LP group showed a median score of 11 (IQR = 2), compared to a median score of 10 (IQR = 2) in the COC group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Verbal memory performance. Median scores (IQR) on the recall condition of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R) in the luteal phase (LP) group and the combined oral contraceptive (COC) group. The difference was analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. **p < 0.01, COC vs. LP.

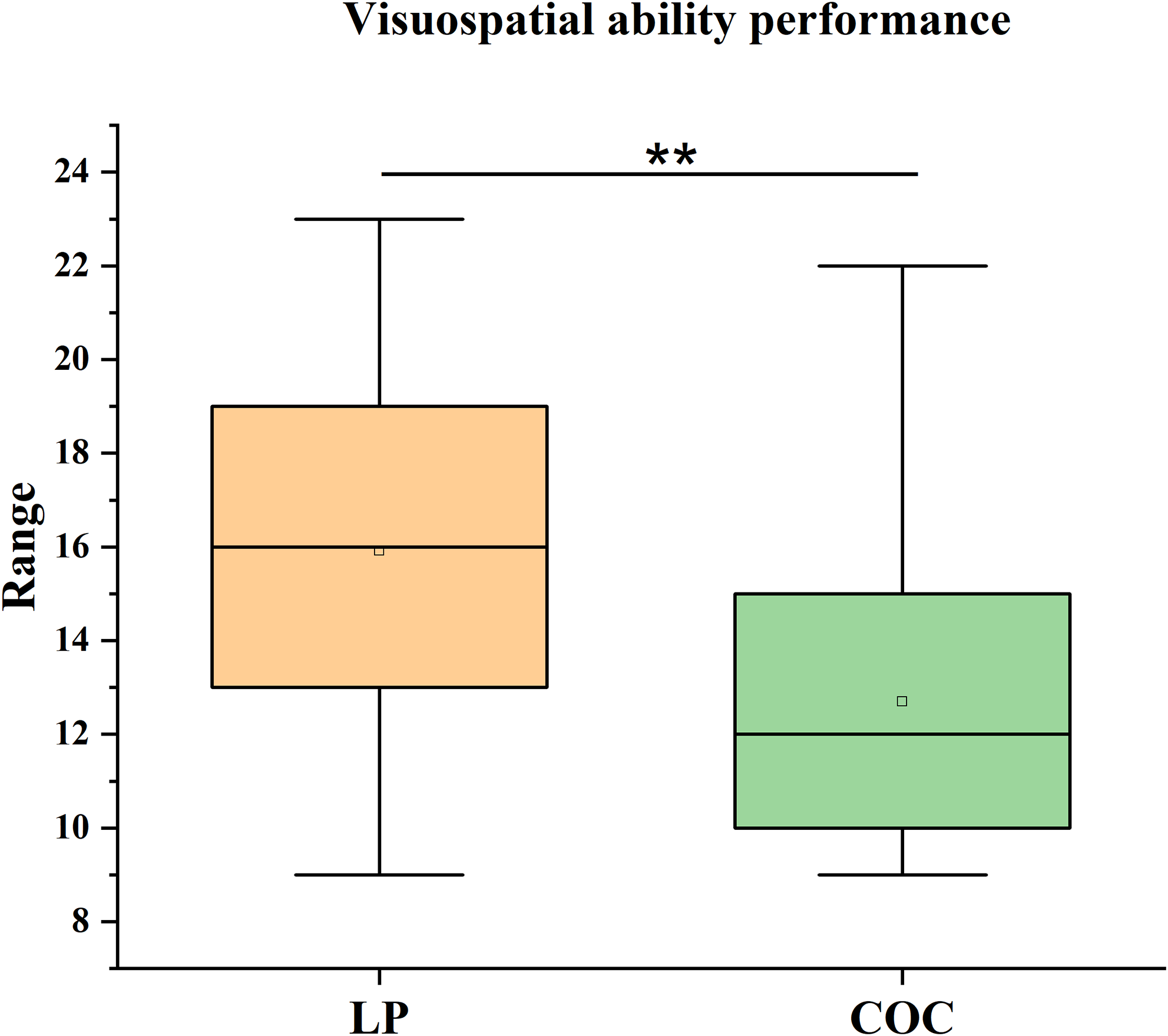

Similarly, a significant difference was observed in visuospatial ability, as measured by the Visual Puzzles subtest of the WAIS-IV, even after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (αadj = 0.0125). The LP group outperformed the COC group (U = 155, p = 0.006), with a medium effect size (r = 0.40). The LP group showed a median score of 16 (IQR = 7) compared to a median score of 12 (IQR = 5) for the COC group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Visuospatial performance. Median scores (IQR) on the visual puzzles subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) in the LP and COC groups. The difference was analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. **p < 0.01, COC versus LP.

COC use is associated with higher scores in cognitive inhibition

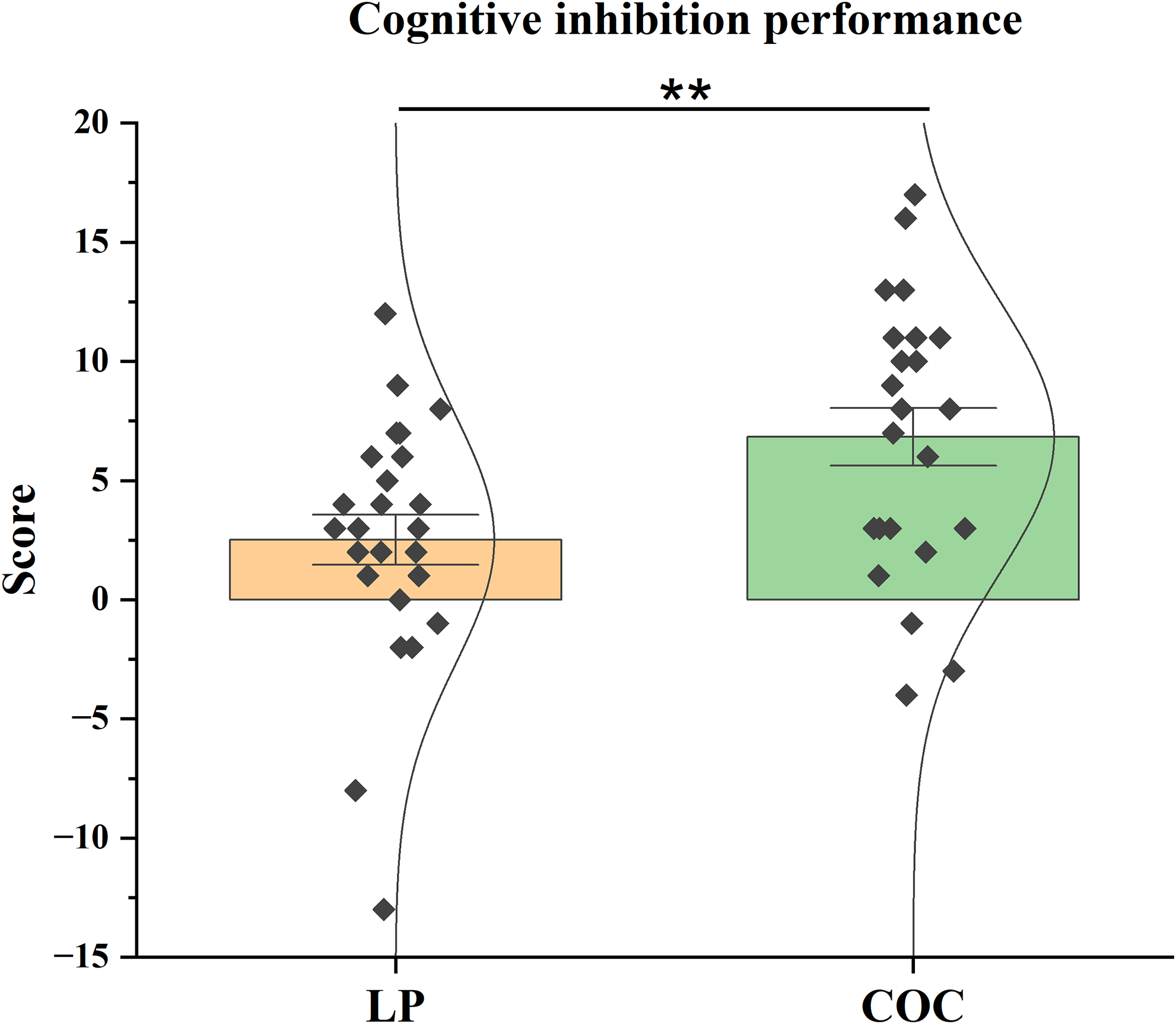

Analysis of cognitive inhibition, assessed via the interference coefficient of the SCWT, showed a significant group difference, even after applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (α adj = 0.0125). The difference was associated with a medium effect size (d = 0.783). The COC group scored significantly higher (t(46) = 2.710, p = 0.009) than the LP group. The COC group scored M = 6.83 (SEM = 1.205), compared to M = 2.52 (SEM = 1.046) for the LP group (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cognitive inhibition performance. Mean interference coefficient scores (± SEM) on the Stroop Colour and Word Test (SCWT) in the LP and COC groups. The difference was analysed using the t-test. **p < 0.01, COC versus LP.

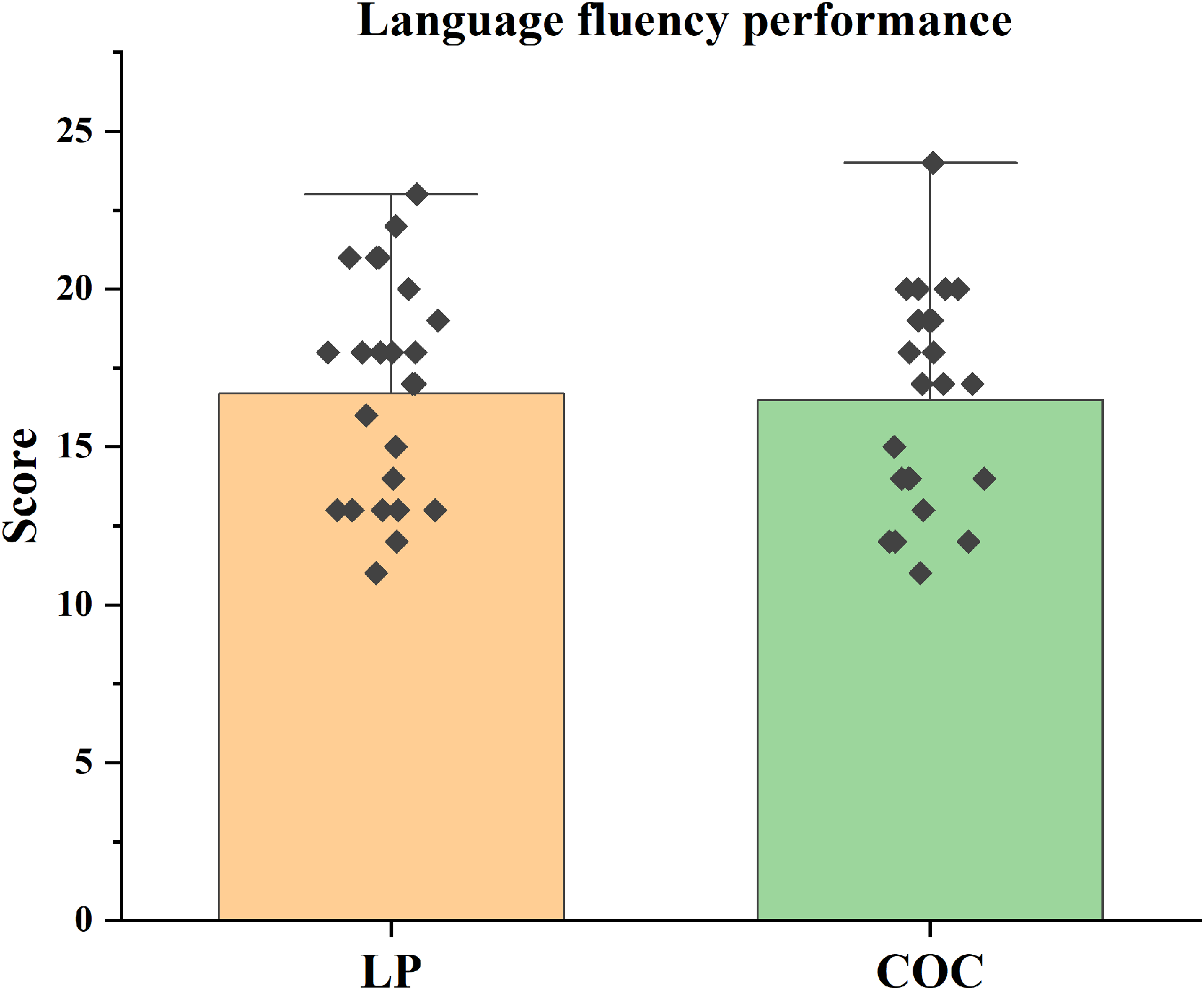

No significant differences were found between groups in language fluency tasks (p > 0.0125) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Language fluency performance. Mean language fluency scores (± SEM) on the verbal fluency test (VFT) in the LP and COC groups. The difference was analysed using the t-test.

Discussion

Our results showed that DRSP/EE use was associated with lower performance in verbal memory and visuospatial ability tasks in comparison to naturally cycling women evaluated in the LP. As indicated in the introduction, the existing literature regarding cognitive associations of COC use is inconclusive; some studies report no differences between COC users and naturally cycling participants, but differences often emerge when COC are separated by progestin action (e.g., androgenic or anti-androgenic) and/or when menstrual cycle phase is assessed (Gurvich et al., Reference Gurvich, Nicholls, Lavale and Kulkarni2023). For example, a recent study reported no differences in verbal memory performance between COC users and naturally cycling participants (Hochheim et al., Reference Hochheim, Frokjaer, Larsen and Dam2025). However, only 6% of those naturally cycling participants were assessed during the LP, and the COC users were not analysed by the differential androgenic action of progestins.

The findings from the current study suggest that LP is a particularly relevant control phase. Differences in verbal memory performance in naturally cycling women have been linked to differences in left hippocampal activity across the menstrual cycle: increased activity is reported during the LP compared with activity during the follicular phase (Lisofsky et al., Reference Lisofsky, Lindenberger and Kühn2015). Given that the left hippocampus is crucial for verbal memory performance (Bonner-Jackson et al., Reference Bonner-Jackson, Mahmoud, Miller and Banks2015), this is further supported by findings showing a decrease in the magnitude of left hippocampus activity during verbal encoding, which was associated with a decline in endogenous oestradiol levels (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Weiss, Makris, Whitfield-Gabrieli, Buka, Klibanski and Goldstein2016).

Regarding visuospatial abilities, the literature suggests that progestin androgenicity is a key factor in performance. In previous studies, non-COC users outperformed anti-androgenic COC users (Wharton et al., Reference Wharton, Hirshman, Merritt, Doyle, Paris and Gleason2008; Griksiene et al., Reference Griksiene, Monciunskaite, Arnatkeviciute and Ruksenas2018). Conversely, androgenic COC users reported higher scores than women in the mid-luteal or pre-ovulatory phases (Peragine et al., Reference Peragine, Simeon-Spezzaferro, Brown, Gervais, Hampson and Einstein2020). In contrast, another study reported no differences in visuospatial abilities and verbal memory among COC users (considering androgenicity) and naturally cycling women (Davignon et al., Reference Davignon, Brouillard, Juster and Marin2024). However, in this latter study, naturally cycling women were only assessed during the early follicular and pre-ovulatory phases and not during the LP. Therefore, the menstrual cycle phase of assessment of naturally cycling participants is relevant to explaining our results.

Visuospatial performance has been reported to be sensitive to the hormonal milieu; lower scores were associated with the highest oestrogen levels (whether due to menstrual cycle phase or COC treatment) (Peragine et al., Reference Peragine, Simeon-Spezzaferro, Brown, Gervais, Hampson and Einstein2020). Almost all our participants (88%) were in the mid-LP, when endogenous oestradiol and progesterone levels are expected to be relatively high. In contrast, DRSP/EE pill suppresses ovulation and maintains low levels of these hormones (Bachmann and Kopacz, Reference Bachmann and Kopacz2009), but possesses anti-androgenic properties (Edwards & Can, Reference Edwards and Can2024; Sitruk-Ware, Reference Sitruk-Ware2006). Therefore, in this domain, our results may be better understood in terms of the anti-androgenic action of DRSP. As mentioned previously, androgenic COC users reported higher scores than anti-androgenic COC users.

Moreover, regarding sex differences, it has been profusely documented that males outperformed females in this cognitive domain (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Kong, Luo, Zeng, Lan and You2019; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Andrinopoulos, Steeves and Kingstone2024), and these differences subsequently increase with age (Lauer et al., Reference Lauer, Yhang and Lourenco2019), mirroring the trajectory of androgens levels (Mason et al., Reference Mason, Schoelwer and Rogol2020). Our study did not measure hormones levels, but is well documented that women using anti-androgenic COC have significantly lower circulating androgens and higher sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases bioavailable androgens (Wierman et al., Reference Wierman, Arlt, Basson, Davis, Miller, Murad, Rosner and Santoro2014; Teal & Edelman, Reference Teal and Edelman2021). Therefore, the observed differences in visuospatial performance could be associated with the DRSP/EE anti-androgenic action.

In concordance with this assumption, our findings indicate that COC users demonstrated higher performance in the cognitive inhibition coefficient. As previously described, performance in this task has been associated with activity in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Okayasu et al., Reference Okayasu, Inukai, Tanaka, Tsumura, Shintaki, Takeda, Nakahara and Jimura2023). Interestingly, neuroimaging studies report increases in frontal cortex activity associated with anti-androgenic progestins use (Pletzer et al., Reference Pletzer, Winkler-Crepaz and Maria Hillerer2023), and previous behavioural studies have reported lower performance in this coefficient during high-hormone menstrual cycle phases (Hatta & Nagaya, Reference Hatta and Nagaya2009). Therefore, the DRSP/EE anti-androgenic action may be linked to increased frontal cortex activity, which could contribute to the observed higher cognitive inhibition performance.

Finally, our results did not indicate differences in verbal fluency. Other studies have reported differences between COC users and non-COC users, but these differences were limited to androgenic COC users (who demonstrated lower scores) in comparison with anti-androgenic COC users and non-users (Griksiene & Ruksenas, Reference Griksiene and Ruksenas2011). Therefore, our results are in concordance with this previous study.

Conclusion

Our findings, which must be interpreted with caution given the small sample and the cross-sectional design, suggest that both menstrual cycle phase and anti-androgenic COC use are potentially associated with domain-specific differences in cognition. The LP, naturally characterised by higher endogenous levels of ovarian hormones, was associated with higher scores in verbal memory and visuospatial ability, but conversely, with lower performance in cognitive inhibition. In contrast, the use of anti-androgenic COC, which are known to suppress the endogenous oestrogen, progesterone and androgen levels, was associated with lower scores in verbal memory and visuospatial ability, yet with a higher score in cognitive inhibition. This domain-specific pattern suggests a complex, non-linear interaction between oestrogen, progesterone and androgens and cognitive domains.

While numerous studies have investigated cognitive changes across the menstrual cycle, in relation to various hormonal contraceptives, and compared male and female performance (Le et al., Reference Le, Thomas and Gurvich2020; Griksiene et al., Reference Griksiene, Monciunskaite and Ruksenas2022; Gurvich et al., Reference Gurvich, Nicholls, Lavale and Kulkarni2023; Pletzer et al., Reference Pletzer, Winkler-Crepaz and Maria Hillerer2023), our results specifically highlight the need for more nuanced research. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to assess causal effects and focus on a wider range of androgenic and anti-androgenic COC formulations to differentiate between the effects of specific progestins. Furthermore, investigation into other contributing variables, such as cognitive strategies, mood, or personality, is essential to increase understanding, as cognitive performance is not a monolithic process.

These findings have real-world relevance for both contraceptive counselling and cognitive assessment. Clinicians should be aware of the potential for minor, domain-specific differences in cognition associated with COC use when counselling patients, particularly those in professions requiring high verbal memory or visuospatial skills. Moreover, cognitive testing batteries should consider menstrual cycle phase or COC status as a variable when establishing baseline cognitive function in reproductive age women.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found here https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2025.10053.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

N.L. conducted the data analysis, prepared the figures and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. L.S.-G. was responsible for participant recruitment and cognitive assessments. A.dT.-L. designed the experimental protocol. A.dT.-L., D.G., T.D.-R. and N.L. contributed to the critical revision and finalisation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study.