Introduction

The number of people living with chronic conditions, such as non-malignant respiratory disease, is increasing, as is the associated need for informal care (Farquhar Reference Farquhar, Bausewein, Currow and Johnson2016). Informal or unpaid care provided by family members and friends is fundamental to the current model of health and social care in the United Kingdom (UK): the contribution by unpaid carers is valued at £162 billion annually (Petrillo and Bennett Reference Petrillo and Bennett2023). The increasing reliance on caregivers, and the economic contribution made by caregivers, makes sustaining this role of great importance to patients, families, and the health and care system. This paper explores the roles and experiences of informal caregivers caring for people with non-malignant respiratory disease at the end of life, to help inform future research and/or service provision.

Non-malignant respiratory diseases are incurable, progressive conditions with significant physical and psychological symptoms and rising global prevalence (Mc Veigh et al. Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2019). The definition of non-malignant respiratory disease used in this review will be that of Mc Veigh et al. (Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2017, Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2018, Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2019): Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and bronchiectasis. These 3 conditions have commonalities in relation to diagnosis in adulthood, symptom burden, and prognosis, therefore suggesting there may be similarities in their impact on caregiver roles and experiences.

There are known inequalities in provision of palliative and end of life care for people with non-malignant respiratory disease (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Atkins and Wilson2019; Butler et al. Reference Butler, Ellerton and Gershon2020). Traditionally, palliative care services have provided care for people with cancer diagnoses, and their families. However, most deaths result from causes other than cancer – 71.5% of deaths in 2019 were non-cancer-related – and the need and benefit of palliative care in non-malignant conditions is well recognized (Hospice UK 2021). Improving end of life care for people with non-malignant diagnoses has been highlighted as a priority for service improvement and research (Hospice UK 2021; Hospice 2024; Alliance Reference Alliance2025).

Advanced non-malignant respiratory disease is associated with high biopsychosocial symptom burden including pain, breathlessness, fatigue, and anxiety (Kingston et al. Reference Kingston, Kirkland and Hadjimichalis2020). For family members and friends, high levels of physical disability, along with emotional distress, can result in significant strain (Maddocks et al. Reference Maddocks, Lovell and Booth2017; Farquhar Reference Farquhar2018). The unpredictable nature of non- malignant respiratory disease progression also hinders accurate prognostication, effective information giving, and timely referral to palliative care services (Pinnock et al. Reference Pinnock, Kendall and Murray2011; Boland et al. Reference Boland, Martin and Wells2013; Bajwah et al. Reference Bajwah, Koffman and Higginson2013b; Mc Veigh et al. Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2019), meaning less access to potentially beneficial care for people with non-malignant respiratory disease and their caregivers. People with these conditions have been reported to have poorer outcomes at the end of life, compared to those with some malignant conditions. This includes delayed palliative conversations, limited engagement in care planning, higher use of invasive interventions, and increased rates of hospital death (Bloom et al. Reference Bloom, Slaich and Morales2018; Butler et al. Reference Butler, Ellerton and Gershon2020; Tavares et al. Reference Tavares, Hunt and Jarrett2020); all of which can add to caregiver distress and burden (Farquhar Reference Farquhar2022). All the above factors may add to caregiver distress and burden (Farquhar Reference Farquhar2022). Better understanding of caregivers’ roles in non-malignant respiratory disease during the end of life period (when symptoms and needs intensify) may allow support to be appropriately tailored, thereby benefiting both caregivers and the people they care for.

The aim of this qualitative systematic review was to identify, review and synthesize primary qualitative literature to answer the question “what are the roles and experiences of informal caregivers providing care to a person with non-malignant respiratory disease at end of life from the perspectives of the caregiver and recipient of care?”

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered on the international systematic review registry (PROSPERO) (registration CRD42023451677), and the completed study is reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Page et al. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt2021) where applicable.

The methodology employed in this review was thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden Reference Thomas and Harden2008). This systematic approach is appropriate for identification, review, and synthesis of qualitative studies concerning experiences and perspectives (Thomas and Harden Reference Thomas and Harden2008; Barnett-Page and Thomas Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas2009). Thematic synthesis draws upon methods of primary data analysis (Thomas and Harden Reference Thomas and Harden2008) and seeks to identify and translate findings from primary studies and combine them to create themes which offer new information and understanding of the topic.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was designed, with speciality librarian input, for the following electronic databases: British Nursing Database, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus, Medline, PsycInfo, ProQuest Sociology, AMED. Databases were selected to ensure broad coverage of disciplines relevant to the topic (Gusenbauer and Haddaway Reference Gusenbauer and Haddaway2020). Limiters were placed to return only peer-reviewed journals available in English; publication date was limited only by the data parameters of each included database. Searches were run to October 2024 and checked for currency in May 2025.

Full details of search terms are available in Table 1.

Table 1. Search terms used in databases searches including Boolean operators

The SPIDER search strategy tool was used to develop the research question and support retrieval of qualitative evidence (Cooke et al. Reference Cooke, Smith and Booth2012; (see supplementary materials 1 for more detail). Database searches returned 1644 records. The Rayyan systematic review platform was used for title and abstract screening against pre-defined eligibility criteria (see Table 2) undertaken by KR with discrepancies discussed by the research team. Sixty-six records were included for full text screening. To ensure consistent application of eligibility criteria, the first 20% of full-text records alphabetically by first author were initially screened by both KR and AL and results compared and discussed. Once consistent application of the criteria was assured, the remaining 80% were screened by KR and AL, results compared, and discrepancies resolved. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Quality assessment

The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (JBI 2020) was used to assess quality of included studies. KR reviewed all articles; 3 sample articles were reviewed by AL to ensure consistent application of the tool. The aim of quality appraisal was not to determine exclusion or inclusion in the review, rather to enable consideration of quality in relation to findings. The quality assessment is available in Supplementary Materials 2.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized form, adapted from Noyes et al. (Reference Noyes, Booth and Flemming2018) and used successfully by the authors previously (Rogers et al. Reference Rogers, McCabe and Dowling2021). KR extracted data from all articles, with a comparative sample independently extracted and checked by AL (see Table 3).

Table 3. Extracted data items

Data synthesis

In thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden Reference Thomas and Harden2008) data synthesis involves a 3-stage process: data are inductively coded line-by-line to identify a unit of meaning and content. The codes are then reviewed for similarities and differences and categorized into “descriptive themes.” Stage 3 requires the researcher (KR) to reconsider the stage 2 descriptive themes in relation to the research question thereby revealing new insights and generating “analytical themes” (Thomas and Harden Reference Thomas and Harden2008). Lumivero NVivo qualitative data analysis software was initially used to support stages one and two of the synthesis process (Houghton et al. Reference Houghton, Murphy and Meehan2017), the work then continued in MS Word and Excel, allowing flexibility during stage three.

Results

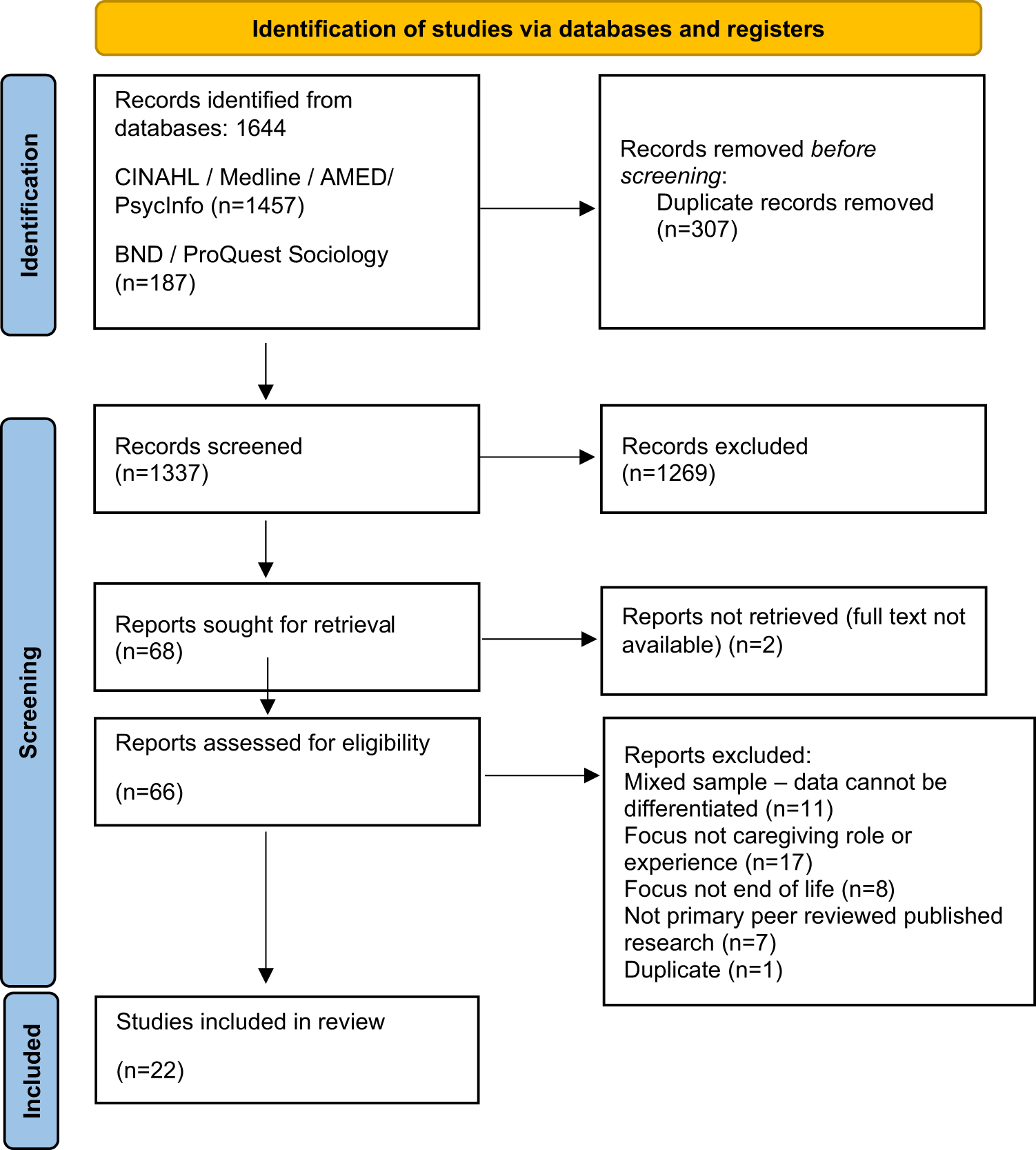

Twenty-two articles were identified which met the eligibility criteria and were included for review (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) flow diagram (Page et al. Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt2021) from searches to May 2025.

Study characteristics

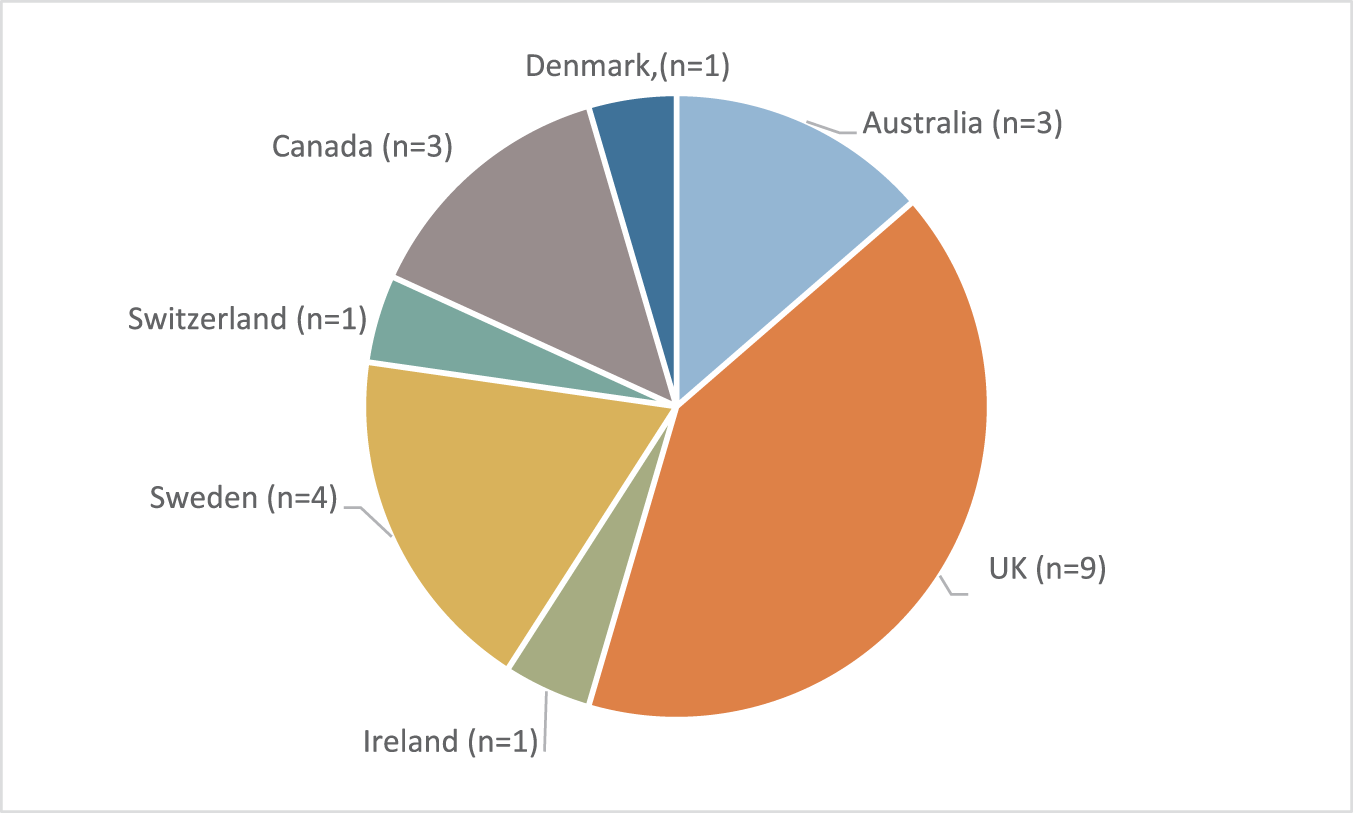

The articles were published between 2001 and 2022 and reported studies from seven countries, with the UK most represented (n = 9) (see Fig. 2). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease was the most represented condition (n = 16 studies), 5 studies focused on ILD, and participants affected by bronchiectasis appeared in only 1 study.

Figure 2. Study location (n = the number of studies from each location).

A summary table showing characteristics of each included study is given in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary table showing characteristics of included studies

Notes:

1 Where HCPs form part of the sample, data collected from HCPs was not extracted for synthesis.

2 Mixed method data collection, only qualitative data was extracted for synthesis.

Table designed using ENTREQ framework for reporting the synthesis of qualitative health research Tong et al. (2012).

[year of publication, country, population, number of participants, data collection, methodology, analysis, research questions]

Data synthesis

The data synthesis process generated 5 analytical themes:

1. Caregivers experience a shift in identity and new roles

2. Adaptation is necessary to cope with loss and change

3. Caregivers need more information and coordinated care services

4. Emotional effects of caregiving

5. Future uncertainty and facing death

See Table 5 for individual study contributions to the analytical themes.

Table 5. Individual study contributions to the analytical themes

Caregivers experience a shift in identity and new roles

Caregiving caused a gradual change in the nature of the relationship between the cared-for person and the caregiver; participants reported emotional and functional changes to relationships: “It feels like I’ve lost my friend. She is not the same person anymore. She has become more selfish and never asks me how I feel, but all focus should be on her” (Caregiver quote; Strang et al. Reference Strang, Osmanovic and Hallberg2018). These changes related to the shift in responsibilities as the cared-for person became more unwell and required more support: “I want a relationship with my husband. I don’t want to check his medications, or check clothes, no, I just want to have a good time with him” (Caregiver quote; Strang et al. Reference Strang, Fährn and Strang2019).

Caregivers described taking on a new identity, although this identity was not always initially acknowledged or accepted positively: “Carers described a lack of choice, even for some, a lack of awareness, until they suddenly realized they were fulfilling a significant caring role” (Author interpretation; Philip et al. Reference Philip, Gold and Brand2014). “Informal caregivers like Penny, wife of James, struggled to adapt to the increasing reliance of her husband on her time and emotional well-being. She felt suffocated and frustrated by his neediness” (Author interpretation; Bajwah et al. Reference Bajwah, Higginson and Ross2013a). Their responsibilities were not only related to the care needs of the cared-for person, but also to the domestic roles previously held by the cared-for person “I’m doing a thousand jobs as well. I’m just going crazy because you don’t get to the end of it… We’re nurses, we’re doctors, we’re housewives, we’re cooks, we’re gardeners. We’re shopping” (Caregiver quote; Seamark et al. Reference Seamark, Blake and Seamark2004).

Caregivers fulfilled a range of roles and in some cases had developed expert knowledge of the condition and associated treatments. Alongside practical, everyday help such as care for personal hygiene, errands, and household duties like shopping and cleaning, caregivers assumed more complex responsibilities. Caregivers became information-givers and decision-makers in the care of the person: “I said she’s not improving much, doctor … She had the bipap here before when she was about this stage and the nurse said, Yeah that might be a good idea, and the doctor put the bipap on.” (Caregiver quote; Philip et al. Reference Philip, Gold and Brand2014). Caregivers were relied upon to relay vital health details to healthcare professionals and in some cases to seek out information about the disease; this proved upsetting when relating to disease severity and prognosis: “Myself and my husband got on the internet and found out ‘well actually life spans 5 years,’ she had no idea, no one’s even told her that (…) so we go ‘how do we tell her this’ (…) so actually the actual breaking the news was myself…” (Caregiver quote; Bajwah et al. Reference Bajwah, Koffman and Higginson2013b).

Caregivers were required to make complicated judgements about when to seek support of healthcare services and often held responsibility for implementing decisions about future care, when advance care planning had taken place: “I think this one is about when they don’t want to be revived, if you got so bad … it is for him to give permission for me to make his decisions on his behalf knowing what he wants?” (Caregiver quote; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Brooksbank and Burgess2012). This role was reported both negatively as a stressor but also positively as a comfort, knowing they could facilitate the person’s wishes: “Because when he was in the hospital, he was in the hospital for a week and he said to me, ‘Don’t ever, ever send me to the hospital to pass away.’ And I said ‘I won’t.’ And I didn’t and I’m glad…” (Caregiver quote; Pooler et al. Reference Pooler, Richman-Eisenstat and Kalluri2018).

Adaptation is necessary to cope with loss and change

Caregivers felt a responsibility to maintain everyday life and to do this, adaptation was needed to accommodate the effects of the illness, in particular breathlessness. Adaptations were made in many aspects of life in relation to daily activities and how the environment was arranged: “…it’d be easier if she stayed in this room so we made that into a bed. And what we did, I mean, the toilet is literally right there, kitchen is out there” (Caregiver quote; Elkington et al. Reference Elkington, White and Addington-Hall2004). The nature of relationships, and the expectations caregivers had of their futures were disrupted by the illness and accompanied by a sense of loss, for example, a participant with COPD commented, “Maybe the hardest thing is that I’m just not up to having sex anymore [pauses for breath], I’m too sick and that’s really hard [cries]” (Ek et al. Reference Ek, Ternestedt and Andershed2011). The participant’s partner acknowledged the need to adapt: “You just have to accept things as they are. In the long run it’s not 100 percent important either. Now we are thankful as long as we still have each other” (Ek et al. Reference Ek, Ternestedt and Andershed2011). Adaptation was ongoing and dynamic in relation to deterioration in the health of the cared-for person and increasing limits on their functional ability: “We miss travelling. We loved to go places and every so often, I forget and I said ‘why aren’t we going down to the warmer climate?’ Now that we have a few pennies … and then we realize … the insurance doesn’t cover his illness” (Caregiver quote; Molzahn et al. Reference Molzahn, Sheilds and Antonio2021).

To cope with increased demands of caregiving, various coping strategies were employed. Peer support from other caregivers was viewed positively by those who engaged with it and was reported to help with both practical and emotional aspects of caregiving. Maintaining hope and a positive attitude also contributed to coping with caregiving: “You can’t get stuck over the impossible, instead you must focus on things that are possible to do. Otherwise it would be just miserable” (Caregiver quote; Strang et al. Reference Strang, Osmanovic and Hallberg2018). Although in relation to deteriorating health of the cared-for person, this hope was often short-lived: “I don’t think I realized how sick my husband was toward the end, and I remained optimistic although we could see that it was unlikely he would be able to get up again” (Caregiver quote; Egerod et al. Reference Egerod, Kaldan and Shaker2019).

The constant nature of caregiving was apparent, and caregivers reported impact on their own health and social life in the course of caregiving: “I collapse. I take sedatives, I sleep poorly, my body aches.. this burden to always take care, I can’t do it anymore. So I have sought help for myself, because I can’t take it anymore, not physically not mentally, I feel like I’m collapsing” (Caregiver quote; Strang et al. Reference Strang, Fährn and Strang2019). “We always had a lot of friends and family in our home … this is the past … he doesn’t want anyone at home … it is so sad and I feel lonely …” (Caregiver quote; Fusi-Schmidhauser et al. Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Froggatt and Preston2020). The cared-for people recognized the burden of caregiving on their family member and worried for the health of that person: “‘I think that the one that suffers most is (my wife) because she’s been hard at it for eighteen months looking after me.’ ‘She’s a sticker, she treats me well and she looks after me, but it’s taken a toll, it’s taken a toll’” (Person with COPD; Seamark et al. Reference Seamark, Blake and Seamark2004).

Caregivers need more information and co-ordinated care services

Caregivers felt they needed more information than was provided by healthcare professionals, particularly in relation to the progression of the disease, the treatments being used (e.g., oxygen therapy), and conversations about the end of life: “There was no information and it was really hard to find and it felt like we were completely on our own … From what I found online, it was scary” (Caregiver quote; Kalluri et al. Reference Kalluri, Orenstein and Archibald2022).

Information was important to support the adaptations needed in response to changes in the health of the person with non-malignant respiratory disease. Being able to talk with healthcare professionals was valuable for caregivers’ own needs, as well as the needs of the cared-for person. Information about available support services and practical issues, such as financial advice, was viewed as lacking and caregivers had to seek sources of information beyond healthcare professionals: “What would have been helpful and comforting for me [is] to have been fully informed. [The patient] didn’t always want to think about it, but I needed to so I could work out what to do” (Caregiver quote; Philip et al. Reference Philip, Gold and Brand2014). Contact with healthcare professionals was appreciated and acted as a support in itself, but did not always happen, or did not happen in a timely way according to caregivers.

Caregivers tended not to emphasize their caregiving role and much of the role remained invisible to those outside the home. This lack of recognition of the role left some caregivers without suitable support: “No, no one has asked about me. Sometimes I wish someone would ask how we’re doing here at home” (Caregiver quote. Ek et al. Reference Ek, Ternestedt and Andershed2011).

Palliative care services were not familiar to all participants, but the concept of holistic care was seen as relevant to care of people with non-malignant respiratory disease from early in the disease trajectory. Issues arose with, and between, primary and secondary care services: secondary care such as respiratory clinics were valued for their specialist skills but could be far from home. Primary and community services did not always provide continuity, and this impacted upon where people were cared for and where they died: “She did die in hospital, she did indeed and that’s part of my hurt, calling the ambulance and letting her die in there. She would have loved to have died at home. I think that if we had had more support at home she could have died at home” (Caregiver quote; Mc Veigh et al. Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2017).

Some participants were able to access local healthcare professionals when needed but others reported not knowing who to contact for support: “Even knowing who to call, or someone to call, would be really nice because when you’re the caregiver it’s not a 9 to 5. It’s 24 hours” (Caregiver quote; Pooler et al. Reference Pooler, Richman-Eisenstat and Kalluri2018).

Emotional effects of caregiving

Caregiving impacted upon the emotional state of caregivers, in the main this was a negative impact although some positives were identified. Watching the person with non-malignant respiratory disease struggle with symptoms, particularly breathlessness, was very difficult for caregivers who found it frightening: “Yes, it is a horror seeing your relative trying to breathe but not getting any air. You cannot do anything! You just try to calm her down and wait for the ambulance” (Caregiver quote. Strang et al. Reference Strang, Osmanovic and Hallberg2018).

As the person’s condition deteriorated, caregivers reported increased anxiety and doubt about their ability to provide adequate care: “If she gets breathless, I am getting anxious and distressed…I really ask myself if I am the right person to look after her…” (Caregiver quote; Fusi-Schmidhauser et al. Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Froggatt and Preston2020). There were feelings of blame and guilt between caregivers and cared-for people, for some caregivers the smoking-related etiology of COPD caused resentment toward the cared-for person, blaming them for their illness: “… but if he would stop smoking, he may be able to keep 40% of his lung function … but nothing, he keeps smoking …” (Caregiver quote; Fusi-Schmidhauser et al. Reference Fusi-Schmidhauser, Froggatt and Preston2020). Both caregivers and cared-for people felt guilt about their situation, cared-for people felt guilty for causing burden, and caregivers worried about not doing enough or not making the right decisions around care and treatment: “I haven’t have trouble accepting that he’s gone, but I just can’t accept the way he died … why didn’t I go and get the nurses? It was my biggest mistake” (Caregiver quote. Egerod et al. Reference Egerod, Kaldan and Shaker2019).

Despite the evident emotional toll of caregiving, some caregivers expressed feelings of pride from fulfilling a duty to care for a family member, or advocating for the person to have their wishes met at end of life: “I just love him and I find that every day when I see him, what else could I do to try and make him a wee bit … better? It’s very satisfying to know that he appreciates what I do and it’s nice to know that you are helping someone” (Caregiver quote; Spence et al. Reference Spence, Hasson and Waldron2008).

Future uncertainty and facing death

Although many participants understood the terminal nature of non-malignant respiratory disease, the speed with which their family member deteriorated and died was shocking. The unpredictability of the disease progression made facing death difficult: “She could be fit in the morning, and then they would phone in the evening to say that I had better come because she hasn’t got long to live, and it continued like that for a very long time” (Caregiver quote; Ek et al. Reference Ek, Andershed and Sahlberg-Blom2015).

As caregivers became accustomed to their family member surviving recurrent exacerbations of their condition, the final deterioration was not always identified as the end of their life: “We [wife and patient] had no idea that he might die. It just didn’t occur to us. Instead, we thought he would become fit as usual and return home, because that is what had happened on previous occasions” (Caregiver quote; Ek et al. Reference Ek, Ternestedt and Andershed2011).

Place of death was important for caregivers reflecting upon the death. Ensuring they died in their preferred place was seen as honoring that person’s wishes: “But I’m glad I did what I did (pause) because he didn’t want to pass away at the hospital. [emphatic] He wanted to pass away at home. (long pause) … he said to me, ‘Don’t ever, ever send me to the hospital to pass away.’ And I said ‘I won’t.’ And I didn’t and I’m glad” (Caregiver quote; Pooler et al. Reference Pooler, Richman-Eisenstat and Kalluri2018).

Both participants and caregivers feared the symptoms of dying, particularly severe breathlessness, and caregivers sought to reassure their family member that they would alleviate these symptoms when the time came: “My greatest worry was that I couldn’t keep my promise to him that he wouldn’t suffocate … he took his last breath at three in the morning, death came peacefully and it comforted us” (Caregiver quote; Egerod et al. Reference Egerod, Kaldan and Shaker2019). Caregivers saw future care planning and decisions about what to do in an emergency as helpful, but these were not always in place due to difficulty in discussing sensitive subjects: “… You’ve probably got to talk about it. What if a decision had to be made? At the moment he’s very lucky, but if we had an emergency and it’s life threatening, well that would have to be my decision. I’m not sure what I would say. I don’t know. We haven’t talked about it” (Caregiver quote; Philip et al. Reference Philip, Gold and Brand2014).

Discussion

This review aimed to identify, collate, and synthesize the qualitative evidence in relation to the roles and experiences of informal caregivers when caring for someone with non-malignant respiratory disease at the end of life. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first review to focus solely on caregivers in this particular context. Respiratory conditions have high global mortality rates, yet this patient group experience a lack of access to specialist palliative care when compared to people with cancer (Janssen et al. Reference Janssen, Bajwah and Boon2023). Focus on this group of caregivers is highly relevant as demand for informal care remains high and the contribution of caregivers is essential to current healthcare systems. This review found that the experience of caregiving in non-malignant respiratory disease at the end of life was characterized by change and loss as caregivers face an uncertain future; more information and support are needed to sustain their caregiving role.

The experience of shifting identity and roles, and coping with loss and change, are not experiences unique to caregiving in non-malignant respiratory disease. For example, Catchpole and Garip (Reference Catchpole and Garip2021) found role and identity changes in people caring for a person with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). As in the current review, caregivers in CFS also reported loss of previous life, and frustration in their caregiving role (Catchpole and Garip Reference Catchpole and Garip2021). The current review found participants described losing aspects of their previous relationship because of the illness and caregiving role. Similarly, Broady (Reference Broady2015) discussed how caring for a spouse with declining health creates imbalance in the spousal relationship as one partner becomes increasingly dependent, and Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Pei and Chen2023) reported that family caregivers in advanced cancer found additional roles to be a characteristic of caregiving, spanning both practical and emotional aspects.

When compared with the findings of this review, the conclusions of Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Pei and Chen2023) demonstrate commonality of experience between caregivers for people with cancer and for people with non-malignant respiratory disease: for example, adaptation and coping strategies across the groups were similar such as, adopting a positive attitude and seeking social support. Also echoing the findings of the current review, Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Pei and Chen2023) noted that although social support was viewed positively, family caregivers reported feeling isolated with reduced social contacts outside the home.

These similarities between caregiving in cancer, and caregiving in non-malignant respiratory disease, demonstrate a widespread need to improve caregiver support and suggest that characteristics of the caregiving experience at the end of life may transcend clinical diagnosis. Despite this suggestion, it should be noted that people with advanced cancer are more likely to receive specialist palliative care input (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Ellerton and Gershon2020) which may include support for caregivers; further highlighting the long-standing inequality and disadvantage of people with, and caring for those with, a non-malignant diagnosis (Care Quality Commission 2016; National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death 2024).

The current review clearly demonstrates that caregivers have unmet needs. This finding resonates with the work of Farquhar (Reference Farquhar, Bausewein, Currow and Johnson2016, Reference Farquhar2018, Reference Farquhar2022) which illustrates the importance of understanding and assessing the needs of caregivers. In particular, the current review highlights unmet needs in relation to information and access to care services. Caregivers report lacking information about practical aspects such as finances, and medical issues such as disease progression and end of life planning. Häger Tibell et al. (Reference Häger Tibell, Årestedt and Holm2024) found that support and information sharing by healthcare professionals led to higher levels of caregiver preparedness for caregiving and for death in advanced cancer, demonstrating the value of contact and communication between families and healthcare professionals. Mirroring findings in the current review, a scoping review of caregiver needs in pulmonary fibrosis also highlighted the importance of information about disease progression, alongside practical advice and the desire to discuss future care planning (Klein et al. Reference Klein, Logan and Lindell2021).

Caregiving in advanced non-malignant respiratory disease can be highly emotive. Feelings of fear, guilt and responsibility are evident for caregivers who are present alongside people as their health deteriorates, and symptoms worsen. Living with COPD can illicit feelings of guilt on the part of the ill person and blame from the caregiver for a perceived “self-inflicted” illness; this may lead to people with COPD feeling unworthy of support (Jerpseth et al. Reference Jerpseth, Knutsen and Jensen2021), further complicating the relationship between caregiver and cared-for. In a narrative review of caregiving at end of life, Nicholls et al. (Reference Nicholls, Carey and Hambridge2025), found feelings of caregiver reward and satisfaction similar to those reported by some participants in the current review. Such feelings often related to successfully upholding the dying persons’ wishes about preferred place of death, highlighting the need for conversations to establish preferences for future care. The current review illustrates the emotional and practical complexity of caregiving in non-malignant respiratory disease, particularly in the context of known inequalities between malignant and non-malignant care provision which may impact the experience of caregivers.

Taylor (Reference Taylor2017) suggests that prognostic conversations commonly precede advance care planning meaning the unpredictability of disease progression and challenge of prognostication in non-malignant respiratory disease may impede timely referrals to palliative care services and cause uncertainty and distress for caregivers (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Atkins and Wilson2019; Ng et al. Reference Ng, Chiam and Chai2024). In the current review, caregivers were often aware of the incurable, progressive nature of the condition but advance care planning, whether with healthcare professionals or in conversation with the ill person, did not always take place. When advance care planning had taken place, caregivers felt satisfied that they could fulfil the wishes of the ill person. It has been further asserted that advance care planning may improve bereavement adjustment for caregivers, as it involves emotional preparation for the death and provides clarity for end of life decision-making (Falzarano et al. Reference Falzarano, Prigerson and Maciejewski2021). In exploring how responsibility shapes the role of family caregivers in Motor Neurone Disease, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Palmer and Kaltsakas2025) also highlight bereavement risks associated with caregiving. As in the current review, complex roles, such as decision-maker, were found to be undertaken by caregivers and Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Palmer and Kaltsakas2025) suggest that the loss of these roles, in addition to their relative’s death, could exacerbate the bereavement experience. Given the potential significant health risks of bereavement, such as physical health problems, poor psychological health and excess mortality, as highlighted by Stroebe et al. (Reference Stroebe, Schut and Stroebe2007), attention on bereavement adjustment and promotion of wellbeing for caregivers is an important consideration for service providers.

Limitations and strengths

Whilst systematic searches were conducted, including follow-up searches to locate newly published work, a possible limitation of this review is that relevant studies may not have been identified, for example those reported in unpublished literature. However, sufficient studies were included in the review to address the research question. Furthermore, none of the included studies was identified as being of especially low quality, although it is noted that the philosophical standpoint, beyond a statement of qualitative methodology, was noted in only 4 of the studies (Seamark et al. Reference Seamark, Blake and Seamark2004; Ek et al. Reference Ek, Ternestedt and Andershed2011; Mc Veigh et al. Reference Mc Veigh, Reid and Larkin2017; Molzahn et al. Reference Molzahn, Sheilds and Antonio2021). Nonetheless, methods were congruent with methodology, and appropriate for the research question or study aims, in all cases.

The authors acknowledge that COPD was the most represented condition in the data included in the current review. ILD and particularly bronchiectasis were less well represented. Whilst COPD is a more prevalent condition (World Health Organization 2024), the experiences of those with ILD and bronchiectasis deserve attention, and more research is warranted in these conditions in future.

It could be argued that including international studies in the current review may limit the transferability of findings across UK health and care systems; however, all studies were from countries with similarly developed healthcare systems, and themes were crosscutting across all the regions represented by the studies.

Thematic synthesis relies upon the researcher to synthesize and interpret data as presented by the primary authors to generate new insights. The subjective value of qualitative interpretation is acknowledged, and the research process has been reported transparently to demonstrate rigor. The lead author is a registered nurse with experience in the care of people dying with chronic, non-malignant conditions and their families. This experience undoubtedly influenced the research process and was reflected upon individually, and within the research team during the study, to examine the work and interrogate potential underlying assumptions. This reflexive practice is a particular strength of the current review, as was the input of public contributors as part of the research team who endorsed the overall topic, contributed to decisions on terminology, and reviewed findings during the synthesis stage.

Conclusion

The current review sheds light on the multifaceted roles and deeply emotional experiences of informal caregivers providing care to a person with non-malignant respiratory disease at end of life, illustrating the highly unpredictable and complex nature of caregiving in non-malignant respiratory disease. Unmet informational needs appear to be a pervasive part of caregiver experience highlighting the need for awareness and recognition of caregivers by those working within the health and social care systems. The significant contribution of caregivers, at an individual and population level, against a backdrop of continuing inequality, clearly illustrates the need for strengthened efforts to improve support for caregivers and in turn the people they care for.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951526101643.

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement contributors Jackie Dolman, Joanne Lloyd and Karen Amegashitsi is recognized with gratitude.

Funding statement

Funding for this study was provided by the University of the West of England as part of an internally funded doctoral capacity building program.

Competing interests

Authors 1, 2, and 4 were all employed by the University of the West of England at the time the research was conducted. Author 2 is now Professor Emerita.