Introduction

When do politicians debate each other in parliament, and when do they prefer to avoid interactions with their fellow legislators? In front of the wide public audience following legislative debates (Lupacheva & Mölder, Reference Lupacheva and Mölder2024; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012; Thesen & Yildirim, Reference Thesen and Yildirim2023; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Thesen, Jennings and De Vries2023), MPs strive to establish and maintain a positive public image of themselves (e.g., Fetzer & Bull, Reference Fetzer and Bull2012; Gruber, Reference Gruber1993), ultimately serving their electoral, career‐related and policy‐making aspirations (Strøm, Reference Strøm1997). This results in an ongoing process of competitive valorisation of an MP's own public persona while at the same time degrading one of their political competitors. These dynamics, which Ilie (Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a) describes as identity co‐construction, lend legislative debates their dialogical character, a topic that has attracted increasing attention among political scientists in recent years (e.g., Bull, Reference Bull2016; Fetzer & Bull, Reference Fetzer and Bull2012; Ilie, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a, Reference Ilie2010b).

The continuous dialogue between MPs in the chamber is vital to representative democracies thriving on active discourse in their legislatures. It allows competing views on political issues to be presented to the public, which also contributes to the information of public opinion‐making (e.g., Landwehr & Holzinger, Reference Landwehr and Holzinger2010). This way, discourse between MPs from competing political camps caters to the fulfillment of the legislative expressive function, which constitutes an essential responsibility of parliaments in representative democracies (for a comprehensive review of work on parliamentary functions, see Marschall (Reference Marschall2018). Further, high‐quality political discourse has the potential to foster compromise among members of legislatures (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Bächtiger, Spörndli and Steenbergen2005), mobilise voters (Disch, Reference Disch2011) and continuously legitimise representative democratic systems as a whole (Judge & Leston‐Bandeira, Reference Judge and Leston‐Bandeira2021). Therefore, understanding the circumstances under which MPs seek discursive interactions in parliament is critical.

A wide range of studies shows that MPs leverage the dialogical nature of parliamentary debates to their advantage, engaging in the antagonistic identity co‐construction dynamics (Ilie, Reference Ilie2017). As speakers, they may address MPs in the chamber verbally (e.g., Antaki & Leudar, Reference Antaki and Leudar2001; Ilie, Reference Ilie2003) and non‐verbally (Arnold & Küpfer, Reference Arnold and Küpfer2024). From their seats in the chamber, MPs engage in identity co‐construction using applause (e.g., Imre et al., Reference Imre, Ecker, Meyer and Müller2023; Küpfer et al., Reference Küpfer, Müller and Stecker2025), interjections (e.g., Ash et al., Reference Ash, Krümmel and Slapin2024; Küpfer et al., Reference Küpfer, Müller and Stecker2025; Miller & Sutherland, Reference Miller and Sutherland2023; Shenhav, Reference Shenhav2008), questions (e.g., Poljak, Reference Poljak2023) and interventions (Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995). However, apart from qualitative, theory‐building work providing illustrative examples (e.g., Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995; Ilie, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a), previous research on these discourse practices has focused on unilateral utterances by either speakers or their audiences.

But when do instances of bilateral dialogical interaction occur during legislative debates? To address this question, we propose a new framework to analyse the emergence of parliamentary dialogue, which consists of two stages. The first stage describes the process where MPs decide whether they want to approach fellow legislators in the chamber and seek to initiate an interaction by inviting them for a dialogical exchange. In the second stage of the framework, invited MPs need to decide whether they want to accept the offer and debate with their colleagues, or not. Only if both MPs are interested in mutual exchange do instances of dialogue in parliament unfold. Thus, our framework covers any practically possible, successful and unsuccessful, attempts to initiate interactions and enables us to understand every decision in this process.

We argue that ideological preferences and government–opposition dynamics are two core principles guiding MPs within decision‐making in both stages of this framework. Initially, we expect MPs to be increasingly inclined to invite fellow legislators for interactions the more they disagree with them on substantial policy issues. We further anticipate opposition MPs to seek discursive exchange more often when facing members of the government majority than vice versa. For MPs receiving these invitations, we expect ideological divergence and government–opposition dynamics to have the opposite effect. This way, diverging ideological preferences are associated with higher risks for invited MPs to follow the invitation and thereby engage in dialogue with their fellow colleagues. Furthermore, we anticipate invited government MPs to be hesitant to engage in dialogue with opposition MPs.

We test these hypotheses on an original corpus of 14,595 interventions (Zwischenfragen) in the German Bundestag between 1990 and 2020, which we retrieved and annotated using a quantitative text classification pipeline developed for this study. Interventions are extraordinary acts of speech by MPs in the chamber that are directly related to the subject of the debate and the speaker's remarks (Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995). Speakers can decide whether they want to pause their speech for such an intervention or continue with their speech instead. Following an intervention, speakers respond to what has been said. In this respect, the decision as to whether or not to allow an intervention is also a decision as to whether they wish to accept the invitation to engage in dialogue with their colleagues in the context of parliamentary debates. Previous research has underscored the highly strategic behaviour of all actors involved in these interventions (e.g., Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995, Reference Burkhardt and Burkhardt2020; Klein, Reference Klein2016; Simmler, Reference Simmler1978). Furthermore, the German Bundestag offers highly structured procedures to handle interventions, ensuring that all attempts appear in the protocol and is home to a dynamically changing party landscape. This way, interventions in the German federal parliament represent an exceptionally suitable empirical case for testing our hypotheses.

Our findings suggest that MPs are guided by ideological preferences and government–opposition dynamics when deciding who they want to invite to a debate, and whose invitations they are willing to follow. As expected, the more ideologically distant two MPs are, the higher the probability that an MP tries to make an intervention and thereby invite the other for a dialogical interaction. The analysis also shows that invitations are most likely to be extended by opposition MPs facing members of the governmental majority in the chamber. MPs receiving intervention attempts are less likely to engage in dialogical interaction with ideologically more distant colleagues. However, we find tentative, yet not statistically significant, evidence suggesting that government MPs are less inclined to give way to intervening colleagues from the opposition. Thus, preferential differences and government–opposition dynamics have important implications for the emergence of discourse in parliament.

The paper proceeds as follows: We start by elaborating on how the dialogue between MPs shapes legislative debates and introduce our two‐stage framework to analyse the emergence of discourse in legislative environments. In a subsequent step, we develop our hypotheses regarding MPs' behaviour in both stages of this framework. We then shed light on the empirical case of interventions in the German Bundestag between 1990 and 2020 as well as on our data generation process and empirical strategy. Moving on to the empirical section of the paper, we present findings from our analysis testing our hypotheses. We conclude by discussing the implications and limitations of our findings as well as avenues for future research.

The dialogical nature of legislative debates

When participating in parliamentary debates, MPs aim to build and maintain a positive and coherent public image of themselves as competent, knowledgeable legislators (Fetzer & Bull, Reference Fetzer and Bull2012; Ilie, Reference Ilie2003, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a). This reputation, also referred to as positive public faces (Gruber, Reference Gruber1993, p. 3), helps MPs when pursuing their re‐nomination and re‐election, career advancement and policy‐making aspirations (Strøm, Reference Strøm1997). At the same time, MPs try to weaken the public appeal of their political competitors (Gruber, Reference Gruber1993; Ilie, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a). These dialogical interactions between political actors in parliament can further help the politicians involved to justify their behavioural decisions, foster trust in their abilities (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Bächtiger, Spörndli and Steenbergen2005) and mobilise them (Disch, Reference Disch2011). This way, MPs participating in legislative debates engage in a continuous process of competitive enhancement and devaluation of each other's public images, which Ilie (Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a) describes as identity co‐construction.

Identity co‐construction dynamics shape plenary debates and are a source of constant dialogical interplay between speakers and their fellow MPs in the audience (e.g., Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1984; Ilie, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a). What is being said at the rostrum can evoke various reactions in the chamber. At the same time, speakers themselves may also seek to signal support or concerns themselves regarding certain colleagues in the chamber or entities they represent (Bull, Reference Bull2016). Plenary debates are therefore characterised by their dialogical nature (Ilie, Reference Ilie2003, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a).

While extant research has examined under what circumstances MPs make use of this dialogical nature of legislative debates, it has kept focusing on rather unilateral forms to express (dis‐)affiliation. From their seats, MPs have been shown to use applause and cheers as affiliative forms for expression (e.g., Bull, Reference Bull2016; Imre et al., Reference Imre, Ecker, Meyer and Müller2023; Küpfer et al., Reference Küpfer, Müller and Stecker2025). To signal their dis‐affiliative stance to the speaker vis‐à‐vis a wide public audience, MPs have been shown to use parliamentary questions and interventions (e.g., Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt2004, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995; Poljak, Reference Poljak2023; Truan, Reference Truan2017) alongside interjections (e.g., Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1984; Bull, Reference Bull2000; Küpfer et al., Reference Küpfer, Müller and Stecker2025). Particularly, female speakers are affected by such dis‐affiliative expressions as they receive significantly higher amounts of uninvited comments from other, particularly male, MPs in the chamber (Ash et al., Reference Ash, Krümmel and Slapin2024; Miller & Sutherland, Reference Miller and Sutherland2023; Och, Reference Och2020). Standing at the rostrum delivering a speech, MPs have been shown to interact with their fellow MPs by inviting favourable reactions from the audience using gestures (e.g., Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1984; Bull, Reference Bull1986), rhetorical devices (e.g., Bull & Feldman, Reference Bull and Feldman2011; O'Gorman & Bull, Reference O'Gorman and Bull2021), quoting (e.g., Antaki & Leudar, Reference Antaki and Leudar2001) or making humorous statements (Bull & Wells, Reference Bull and Wells2002; R. Müller, Reference Müller, Tsakona and Popa2011). They also seek confrontation with other MPs, or entities which they represent, by attacking (Poljak, Reference Poljak2023), and addressing them verbally (Antaki & Leudar, Reference Antaki and Leudar2001; Ilie, Reference Ilie2003) or even non‐verbally (Arnold & Küpfer, Reference Arnold and Küpfer2024). These are all common ways for MPs to influence parliamentary discourse both as speakers as well as from their seats in the audience. However, the highly informative studies drawing on this literature have primarily focused on unilateral modes of expression of either the speakers or their fellow MPs in the audience.

This assessment reveals a gap in the existing literature on parliamentary discourse. Despite the potential for dialogical interactions stemming from both speakers' and their audience's behaviour, we still know very little about the circumstances under which they materialise. This is surprising given that a wide range of research highlights how legislative debates thrive on and are characterised by their dialogical character (e.g., Bull, Reference Bull2016; Ilie, Reference Ilie2003, Reference Ilie and Ilie2010a). In particular, we do not know under which circumstances MPs are interested in a discursive exchange with their fellow legislators and when this is not the case. We will shed light on these considerations in the following section.

Who wants to debate whom in parliament?

In this section, we develop a theoretical framework describing who tries to debate whom in parliament and when these efforts are successful, meaning that both MPs are interested in a dialogical exchange which, eventually, unfolds. Our framework distinguishes between MPs inviting others to a discursive interaction in parliament and those being invited. Inviting MPs seek to initiate a discursive interaction by extending an invitation to participate to a fellow MP in the chamber by implicitly or explicitly signalling deviant or opposing positions to the respective MP. In practice, speakers can invite their colleagues in the chamber to join in the discourse during their speech, while they, in turn, can use interjections, interventions or gestures to seek direct exchange with the speaker (Truan, Reference Truan2017). The role of the inviting MP is somewhat similar to that of attackers in the framework by Poljak (Reference Poljak2023) in the sense that they both explicitly seek the confrontation with competing political actors. Unlike attackers, however, inviting MPs do not necessarily seek to attack as an end in itself but explicitly want to initiate direct dialogical interactions with the opponent in front of a broad public audience. In a subsequent step, MPs receiving an invitation can decide on whether to do so or not. If they accept the invitation, they enter into a direct dialogue with their colleagues in the plenary. If they decline, as a speaker they continue with their speech or, as an MP in plenary, they remain silent or start another attempt at the next occasion.

The distinction between inviting and invited MPs makes no assumptions regarding the institutional environmental factors surrounding the actors who decide on whether to seek or avoid discursive interaction. This ensures that the framework can be used to analyse the emergence of dialogical interaction in various settings of elite discourse.

In general terms, dialogical interactions are associated with opportunities and risks for both the inviting and the invited MP: On the one hand, such discursive interactions allow MPs to showcase their stances as superior to those of their political competitors in front of a wide public audience, contributing to their policy‐seeking and electoral efforts. They also harbour potential for MPs' career advancement and vote‐seeking efforts and represent an opportunity to present themselves, alongside their rhetorical abilities, in a positive light while strengthening their personal public image in competition with their political opponents, both within and outside their own party. Dialogical interactions are therefore very attractive for MPs pursuing their individual career‐advancement, policy‐ and vote‐seeking goals. On the other hand, MPs participating in discursive interactions face the risk of losing the debate to their counterpart and thereby harming both of these goals.

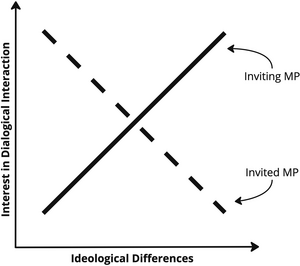

But under what conditions do MPs seek dialogical interaction, and when do they refrain? To address this question, we apply our framework starting from the assumption that political preferences substantially shape political, and thus legislative, behaviour, in line with seminal work within the legislative studies (e.g., Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012, Reference Proksch and Slapin2014; Schonhardt‐Bailey, Reference Schonhardt‐Bailey2003; Slapin et al., Reference Slapin, Kirkland, Lazzaro, Leslie and O'Grady2018). Therefore, we expect the political preferences of the MPs involved, and – more precisely – the degree to which they differ, to influence whether they are interested in directly engaging with each other or not. At the same time, we expect increasing preferential differences to have contrary implications for these two groups of actors: While increasing ideological differences between two MPs might serve as cues for one of them to invite the other for a dialogical interaction, these same disparities can also encourage MPs receiving such invitations to decline (see Figure 1). We further anticipate government–opposition dynamics to harbour opposing implications for various actors in the parliamentary discourse. By expecting MPs to rationally seek and avoid discursive interaction based on the potential risks and fortunes associated with either option, we follow what Bächtiger (Reference Bächtiger2014) coins as the strategic and partisan‐rhetoric approach to analyse debates in parliament.

Figure 1. Interest in seeking dialogue among inviting and invited MPs associated with varying levels of ideological differences.

Whom do MPs invite for a dialogical interaction?

The position of MPs inviting fellow legislators for a dialogical interaction is characterised by two strategic advantages over one of their counterparts receiving the invitations. First, inviting MPs can decide themselves when they want to address whom. MPs primarily extend invitations to engage in discourse within scenarios where they feel reasonably sure about the point they want to make and are confident that they can succeed in the debate with their counterpart. Due to this strategic advantage, the risk of losing out during a dialogical interaction is typically rather limited for those extending invitations. Second, MPs deciding whether to initiate the dialogue face no direct consequences from deciding against it, as the public remains unaware of their internal deliberations. Hence, MPs who choose to seek dialogical interaction have a strategic advantage over their colleagues who are confronted with their invitation.

Every situation where an MP does not agree with the positions or actions of other MPs in the chamber constitutes an occasion to invite them for a dialogue. We assume MPs to generally be receptive to opportunities enabling them to engage in discursive interactions with their colleagues since dialogical interactions are attractive opportunities to work on their public personas. Increasing differences in political preferences are a function of a rising number of issues political actors have divergent perspectives on, which are reflected in greater levels of inter‐party conflict (Küpfer et al., Reference Küpfer, Müller and Stecker2025; Poljak, Reference Poljak2023). Hence, we expect increasing differences in ideological preferences between two MPs to be associated with a higher probability of one of them inviting the other for a dialogue.

While it is well established that opposition parties have strategic incentives to engage in conflict with the government, it is not as clear which implications this has for their interest in dialogical interaction. Opposition parties benefit electorally from a distanced – and potentially conflicted – relationship with the government (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Tuttnauer & Wegmann, Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022; Whitaker & Martin, Reference Whitaker and Martin2022). Such a stance vis‐à‐vis the government helps opposition actors in demonstrating their substantive disagreement with the executive's behaviour. They are also signalling their engagement in fulfilling their institutional role as opposition actors by controlling the government, which can be attractive to voters regardless of their ideological preferences (Tuttnauer & Wegmann, Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022; Zur, Reference Zur2021). Dialogue with government actors in legislative debates offers an attractive opportunity for these activities, as opposition MPs can elaborate their criticism and potentially even persuade voters of their stance instead of merely interjecting. Further, since opposition parties are less powerful than government parties in shaping the issues debated in parliament, they have an additional incentive to seek alternative ways to push their issues onto the legislative agenda (Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins2005). We, therefore, expect members of the opposition to be particularly inclined to seek debates with fellow MPs from governing parties and engage in dialogical interactions with them.

H1a: The greater the ideological differences between two MPs, the more likely it is for one of them to invite the other to engage in dialogical interaction.

H2a: Opposition MPs are more likely to invite their colleagues from the governing majority for dialogical interaction than vice versa.

When do MPs accept the invitation?

In contrast to inviting MPs, the recipients of these invitations can only choose between two options, each of which is associated with some substantial risks alongside certain opportunities. Accepting invitations implies joining conversations initiated by fellow MPs who, as outlined above, are rather confident in the argument they wish to convey. If they succeed, this can pose a threat to the invited MP's public standing. At the same time, invited MPs can feel more pressure to engage in discursive exchanges with their inviting counterparts since being an expert on the debated issue. Further, they may feel confident in their substantive knowledge and rhetorical abilities, enabling them to challenge the arguments of the inviting MPs and succeed in a dialogical interaction. This way, invited MPs can capitalise on interactions they did not initiate in the first place, which contributes to their positive public perception.

Declining an invitation prevents invited MPs from losing out during the dialogue and thereby damaging the public image they strive to build and maintain. However, their image may also suffer from avoiding discursive interactions, as this can feed the impression that the invited MPs are not able to counter the arguments of their critics. Therefore, trying to avoid discursive interactions undermines the goal of shaping a positive public image and can damage the credibility of invited MPs. In sum, both shunning and engaging with the inviting MP have the potential to preserve or even enhance the image of the invited MP. At the same time, both options are associated with certain risks, requiring MPs who are confronted with an invitation to carefully weigh up which behaviour is more conducive to their identity co‐construction efforts.

We argue that MPs are generally inclined to follow a substantial part of the invitations they receive. As the cultivation of an advantageous public profile is always at the heart of MPs' efforts during legislative debates, which are inherently dialogical, the risk of being perceived as legislators who cannot defend their position and avoid discourse with other representatives instead of standing up to and refuting counterarguments is too great. Hence, we assume that there is a certain level of general willingness among invited MPs to engage in dialogical interactions. At the same time, we expect invited MPs to navigate the discussed risks along ideological preferences and government–opposition relationships, serving as indications of how the inviting MPs might encounter them in potential discursive interactions.

We expect ideological considerations and government–opposition relations to have the opposite effects on invited MPs as on their inviting counterparts. After all, what makes the position of invited MPs particularly challenging is its informational disadvantage vis‐à‐vis the inviting colleague. While inviting MPs benefit from determining the conditions under which they expect to gain an advantage from the dialogical encounter and can pursue it through the invitation, their invited fellow legislators are not necessarily well prepared for their arguments at this stage. Invited MPs must also consider that their counterparts likely have a compelling point to make, as inviting MPs would have concluded that the dialogue is strategically worthwhile for them. Thus, we argue that invited MPs tend to avoid discursive interactions with colleagues who are more ideologically distant, as this would give their confident political competitor and strongest critic an opportunity to publicly criticise their stance. Moreover, invited MPs would have to expect this interaction not necessarily to unfold in a particularly collegial manner, as adversarial behaviour between MPs becomes more likely the greater the ideological differences between them are (e.g., Otjes & Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2018; Poljak, Reference Poljak2023). Consequently, public discursive interactions with politically distant colleagues are particularly risky for invited MPs, which is why they tend to avoid them.

As elaborated above, opposition MPs' behaviour in parliament is shaped by their critical stance towards the government, which has also been shown to be an effective vote‐seeking strategy (Tuttnauer & Wegmann, Reference Tuttnauer and Wegmann2022). Critical assessments of government action are hardly conducive to the public image of members of the governing majority and are instead more likely to harbour the same dangers as questions from politically distant MPs. Therefore, we anticipate members of the government majority to be less inclined to follow invitations to debate members of the opposition than vice versa. This way they avoid granting critical views on their behaviour and decisions to become more visible than they already are.

H1b: The greater the differences in ideological preferences between two MPs, the less likely it is for one of them to accept the other's invitation to engage in dialogical interaction.

H2b: MPs from the government majority are less likely to accept invitations for dialogical interaction from opposition MPs than vice versa.

Further explanations drawing on MPs' personal characteristics

There is a thriving body of literature examining how behavioural patterns are unevenly distributed across groups of political elites sharing certain individual‐level characteristics (e.g., Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Debus and Müller2015; Burden, Reference Burden2008; Jones, Reference Jones, King, Schlozman and Nie2009; Matthews, Reference Matthews1960; Searing, Reference Searing1993). This has important implications for our theoretical considerations given that individual MPs, not parties, ultimately decide on whether to seek and avoid discourse in parliament. Therefore, we will also explore whether our core predictors of MP behaviour hold when incorporating individual‐level characteristics, which have widely been discussed to substantially affect elite behaviour. For the purpose of this study, we focus on three MP characteristics, namely gender, seniority and mode of election, which we will introduce individually below.

Female politicians have a systematically disadvantaged position in plenary debates compared to their male counterparts (e.g., Ash et al., Reference Ash, Krümmel and Slapin2024; Lovenduski, Reference Lovenduski2012; Miller & Sutherland, Reference Miller and Sutherland2023; Och, Reference Och2020). This is in line with earlier work showing that female politicians evaluate their political capabilities systematically lower compared to male peers (e.g., Fox & Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2011), while also facing substantially higher barriers when competing for speaking time (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Baumann, Debus and Müller2019, Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014), gain media visibility (Thesen & Yildirim, Reference Thesen and Yildirim2023) and advancing their political careers (e.g., Koch et al., Reference Koch, Kuhlen, Müller and Stecker2024; Kroeber & Hüffelmann, Reference Kroeber and Hüffelmann2022; O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2015).

Another strand of literature examines how politicians' seniority influences very similar dimensions of their legislative work. In this vein, research suggests unexperienced MPs are less likely to make interjections compared to their colleagues who have served multiple terms (e.g., Diener, Reference Diener2024). These findings are also supported by a wider body of work showing senior candidates and mandate holders to have substantial advantages in their individual electoral and career‐advancement efforts (e.g., Cirone et al., Reference Cirone, Cox and Fivy2020; Shomer, Reference Shomer2009).

A final body of research sheds light on how the mode of election influences how MPs navigate legislative environments. A core notion in this field states that MPs, as agents, serve different principals depending on whether they were elected into parliament by direct vote or as candidates on closed party lists, resulting in different priorities guiding parliamentary behaviour. This way, directly elected MPs are more likely to engage in signalling efforts targeted at their constituency (Zittel et al., Reference Zittel, Nyhuis and Baumann2019) and to deviate from orchestrated party positions both as candidates (Debus et al., Reference Debus, Lattmann and Wagner2024) and as elected MPs (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010).

As demonstrated above, politicians' gender, seniority and mode of election have significant implications for their strategic behaviour as legislators. Consequently, it is plausible to expect that these factors influence their incentives to seek or avoid discursive interaction in the plenary.

While these additional aspects may play a role in MPs' strategic reasoning regarding the risks and opportunities of their potential involvement in discursive interactions with their colleagues, we expect ideological preferences and government–opposition dynamics to remain the core explanatory factors. Even when further MP characteristics are being considered, parties remain the central coordinating actors in most Western, especially Western European, legislatures. Their coordinative power leaves individual legislators with relatively little room to manoeuvre when it comes to acting against the party's orchestrated line (e.g., Cox, Reference Cox2006; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2020). This is particularly the case during plenary debates, given that the parliamentary chamber represents the key venue of party competition outside campaign environments, where party dominance is potentially even higher than in other realms of parliamentary business. Hence, we expect the factors which were discussed in the previous two sections, that is, ideological differences in government–opposition dynamics, to remain the central explanatory concepts in the pursuit and avoidance of parliamentary discourse.

Data and research design

We test our theoretical expectations on the empirical case of interventions (so‐called Zwischenfragen) in the German BundestagFootnote 1 between 1990 and 2020. Interventions represent a unique opportunity to study who seeks, and avoids, discourse with whom as they force MPs to follow a formalised procedure when seeking to initiate instances of dialogical exchange. This way, interventions reveal strategic trade‐offs that MPs make with regard to their involvement in dialogical exchange with fellow MPs in the chamber.

Interventions in the German Bundestag, in particular, are a suitable case to study the circumstances under which MPs seek and avoid discursive interaction for multiple reasons: First, a wide range of scholars have highlighted the highly strategic use of interventions by members of the German Bundestag (Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt, Dörner and Vogt1995, Reference Burkhardt2004, Reference Burkhardt and Burkhardt2020; Klein, Reference Klein2016; Simmler, Reference Simmler1978), describing ‘the emphasising presentation of the own position […] while at the same time devaluing and simplifying the others’ point of view, [as] the most striking feature of interventions [in the German federal parliament]' (Uhlig, Reference Uhlig1972, p. 172). The strategic use of interventions is essential for the application of our framework since it strengthens our assumption that MPs are guided by strategic, partisan considerations when deciding whether they want to accept invitations for an interaction or not. Furthermore, granted interventions allow for actual engagement in a substantive argument,Footnote 2 and they show a high relevance in German parliamentary life.Footnote 3 Second, while interventions are an established device in various Western legislatures (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Fernandes2021; European Parliament, 2021), Zwischenfragen in the German Bundestag follow a well‐structured procedure ensuring a comprehensive stenographic documentation of all attempts in the plenary minutes and enables their complete automated detection. The dynamics we study in the German Bundestag are, therefore, comparable to those in other parliaments. The detailed documentation of all intervention attempts in the German case, however, allowed us to construct an original, comprehensive and high‐quality dataset spanning 30 years. Third, the last change to the Standing Orders of the German Bundestag affecting interventions was introduced in 1990, which implies that the institutional conditions remained unchanged throughout the entire observation period (Burkhardt, Reference Burkhardt and Burkhardt2020). Finally, the German Bundestag offers an exemplary case for studying modern parliamentary politics due to its dynamic party landscape with shifting government memberships, fluctuating party sizes and continuously evolving inter‐party relationships (J. Müller et al., Reference Müller, Stecker, Blätte, Bäck, Debus and Fernandes2021). Hence, findings derived in this study inform our understanding of elite discourse in various representative democracies characterised by multiparty systems.

The Standing Orders of the German Bundestag allow MPs to ask for permission to intervene at any point during a plenary debate. The following examples show two typical intervention situations:

Example I: Conservative MP allows intervention by a Green MP

Dr. Norbert Lammert (President): May Mr. Gastel make an intervention? […]

Ulrich Lange (Conservatives): Honourable colleague, if you like, please, go ahead.

Matthias Gastel (Greens): Thank you very much. […] You just mentioned the issue of bridges. We have seen a massive deterioration of bridges. […] Now you said that bridges will be assessed using quality metrics and that penalties are being imposed. But you also know that only a small proportion of bridges are assessed accordingly, just under 1,000 out of a total of 25,000 bridges, to be precise. Do you seriously believe that […] you will be able to avoid mis‐allocations and ensure that the money really is used to maintain the bridges? What about the other 24,000 bridges? We need to address them too.

Ulrich Lange (Conservatives): Mr. Gastel, I did not know that all 25,000 bridges are around 100 years old and about to collapse. […] Instead, those exact bridges have been singled out and it are precisely these bridges that are in urgent need of renovation. It is even prescribed how the renovations must be carried out. We believe this is the right, sound and sufficient approach (Bundestag, Reference Bundestag2014, p. 6767).

Example II: Far Right MP declines an intervention by a Social Democrat MP

Thomas Oppermann (President): Mr. Frömming, would you allow an intervention from colleague Röspel (Social Democrats)?

Götz Frömming (Far Right): No, I would like to complete my remarks without interruption. Thank you. […] (Bundestag, Reference Bundestag2019, p. 12239).

As demonstrated in the first example, Gastel (Greens) requests an intervention which is forwarded to the speaker (Lange, Conservatives). Lange allows the intervention, whereupon Gastel confronts his colleague at the rostrum with a critical perspective on his remarks. In the second example, in contrast, the president asks Frömming (Far Right) for his approval of an intervention by Röspel (Social Democrats). Frömming does not allow it by arguing that he wants to proceed with his speech without interruptions. The president has an overview of the plenary hall and is an intermediary actor responsible for an orderly debate that aligns with the rules of procedure.

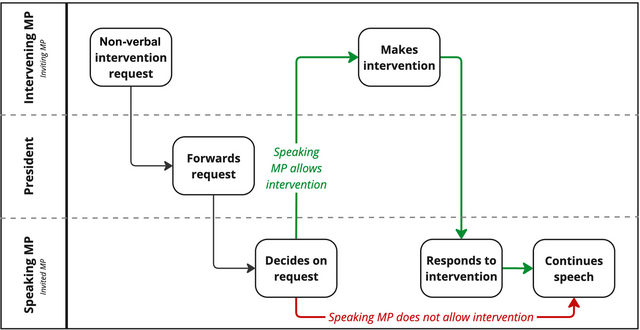

While it is a relatively easy task for humans to capture the course of an intervention attempt, it is a sophisticated task for a model due to the heterogeneity of keywords and formulations inherent to intervention situations and decisions. Our initial database of interventions contains all speeches available between 1990 and 2020 in the GermaParl (Blätte, Reference Blätte2020) corpus. As the corpus contains the text of all speeches, it also offers granular and precise meta‐information such as the legislative period, speech date, agenda item, party and speaker name. Figure 2 describes the most common paths from requesting an intervention to answering it. MPs first request an intervention through non‐verbal signals before they are picked up by the president chairing the debate. In terms of our proposed framework, this represents an invitation of an MP in the chamber to engage in a dialogue, which is being extended to the speaker. After receiving this request, the speaking MPs can then decide whether they want to proceed with their speech or engage in interactions with their fellow MPs in the chamber.

Figure 2. Illustration of the life cycle of an intervention (attempt) and its actors using the empirical case of interventions in the German Bundestag.

There are three central challenges to automatically extracting and annotating interventions, which typically follow the procedures depicted in Figure 2.Footnote 4 First, recognising an actual intervention situation builds the foundation of stage one of our framework. Second, annotating the decision to either approve or reject an intervention request is important for stage two of our framework. Third, we need to extract both the speaker's and intervening MPs' names and map them with their party. This last matching challenge allows for gathering information on the MP's status in the parliament (e.g., government vs. opposition or ideology) and, thus, investigating our hypotheses.

We developed, implemented and validated a pipeline that automatically detects and annotates all intervention attempts within our observational period. As we are interested in substantial debates, in the first step, we removed all debating formats whose main purpose is to control the government.Footnote 5 In a second step, we developed textual patterns to keep only actual intervention attempts, which are either announced by a non‐verbal action of an MP in the chamber or the chairs themselves. These situations were automatically annotated by looking for typical phrases of rejecting or allowing an intervention while incorporating a direct change of speakers as a strong indicator for an allowed question. Finally, we used a named entity recognition model specifically trained in German (Akbik et al., Reference Akbik, Blythe, Vollgraf, Bender, Derczynski and Isabelle2018) to extract the questioner's name from the president's announcement or the non‐verbal request of the questioner MP. We joined both the speaker and questioner names with related data from the Comparative Legislators Database (Göbel & Munzert, Reference Göbel and Munzert2022), a widely used resource providing meta‐information on the members of various federal parliaments around the world. Measures for the ideological distance between two MPs were computed using the absolute difference between ideology measures from the Manifesto Research on Political Representation database (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024). Additional daily information on individual MPs was drawn from Parliaments Day‐by‐Day (Turner‐Zwinkels et al., Reference Turner‐Zwinkels, Huwyler, Frech, Manow, Bailer, Goet and Hug2022).

Following this approach, we were able to derive robust annotations. To evaluate the outcome of this pipeline, we annotated a random sample of 1000 situations marked as containing any intervention‐related keywords. If we look at all these instances, the share of entirely correctly classified interventions lies at 89.95 per cent.Footnote 6 Our inter‐annotator agreement between two annotators lies at 0.91 Cohen's kappa score. A high agreement between annotators is not surprising as there is only a small room for interpretation in intervention situations. Our final dataset contains 14,595 attempted interventions between the 12th and 19th legislative periods and provides us with a solid empirical foundation for our subsequent analyses.

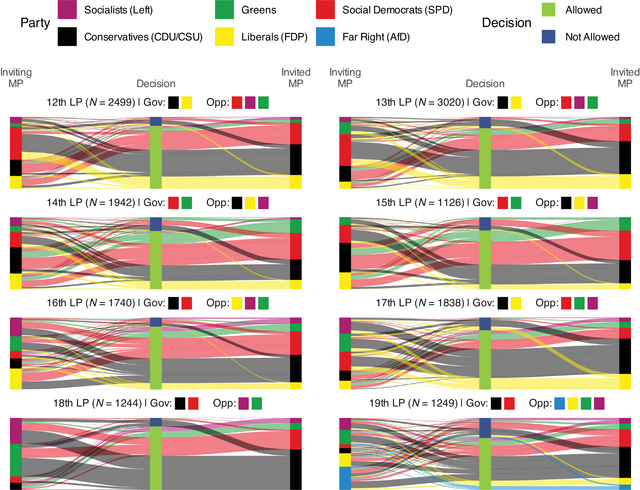

Which party receives how many intervention requests, and by which party are they extended? Figure 3 draws a fine‐grained picture by grouping for legislative periods and addressing the decision of the speaking MP. Each title indicates the number of intervention attempts as well as the party colours of the current government and opposition parties in a legislative period. The left‐hand side of each sub‐figure shows the party of the intervening MPs, while the right part depicts the party of the invited speakers. The centre pillar divides all attempts into allowed (light green) and rejected (dark blue) interventions.

Figure 3. Intervening (left column) and speaking MP (right column) by party, legislative term and speaker decision. The centre column indicates whether an intervention was allowed or rejected.

A few descriptive patterns stand out: The number of intervention attempts varies between legislative periods, having a mean of 1832. Further, the effects of opposition versus government become visible in this scenario. Government parties show substantively fewer attempts than opposition parties – while the government still receives most of the questions.Footnote 7 A particularly vivid example of these government–opposition dynamics is the shift from the 13th to the 14th legislative term, where the liberal‐conservative government, led by Helmut Kohl, was replaced with the Social Democratic‐Green coalition with Gerhard Schröder as the Chancellor. During the 13th term, the Social Democrats and Greens were responsible for significant parts of the intervention attempts and had the government majority, particularly in their sights. After the change of government, the tide turned. Now, the conservatives and liberals, who are now in opposition, undertake the majority of the intervention attempts and thereby focus on the new, centre‐left government. Finally, as expected, a remarkably high proportion of interventions is allowed (on average, only 16.23 per cent are being rejected).

Focusing on the 19th legislative period highlights the impact of the far‐right party AfD as a new member of the Bundestag. The party is responsible for the largest share of question attempts. However, other parties turn down the AfD's request during almost half of their invitations. This circumstance is the main driver for an increased rate of rejected intervention attempts in the 19th legislative period (27.78 per cent) compared to the average rejection rate of previous legislative periods.

Estimation strategy

To comprehensively test our hypotheses, we follow a two‐stage estimation strategy. In the first stage, we identify all possible combinations of MPs delivering speeches and those who might intervene during each speech in our observation period (i.e., MPs holding a mandate in the German Bundestag on the respective day). This leaves us with a dataset of the size of

where ![]() iterates over all days in all legislative periods and

iterates over all days in all legislative periods and ![]() describes all speeches in the dataset.

describes all speeches in the dataset. ![]() is the number of MPs that could have asked the current speaking MP on day

is the number of MPs that could have asked the current speaking MP on day ![]() and speech

and speech ![]() for an intervention. This dataset contains almost 60 million MP dyads and a metric outcome variable indicating the number of intervention attempts which have been observed between the two during the respective speech. Not every MP who might potentially make an attempt to intervene is physically present at any point of a debate. At the same time, we ensure that only those MPs are considered as potentially intervening colleagues who actually hold a mandate in parliament on the exact day of the observation. This way, every potential intervener has access to the plenary and, given that the agenda, including the list of speakers, is known ahead of the debate, both presence and abstention from the debate is a conscious decision of all MPs.

for an intervention. This dataset contains almost 60 million MP dyads and a metric outcome variable indicating the number of intervention attempts which have been observed between the two during the respective speech. Not every MP who might potentially make an attempt to intervene is physically present at any point of a debate. At the same time, we ensure that only those MPs are considered as potentially intervening colleagues who actually hold a mandate in parliament on the exact day of the observation. This way, every potential intervener has access to the plenary and, given that the agenda, including the list of speakers, is known ahead of the debate, both presence and abstention from the debate is a conscious decision of all MPs.

To examine when MPs seek to invite one another for a discursive interaction, we use a Poisson regression model. This is a suitable estimation strategy given the high number of speech‐wise MP dyads where no intervention attempt has occurred. In this stage 1 model, we control for the ideological difference between a potential questioner and the current speaker and a dummy variable indicating whether the intervening MP belongs to the opposition and the speaker to the government to account for opposition–government dynamics. This way, we can address our first pair of hypotheses.

In the second step of our estimation strategy, we shed light on the stage of our theoretical framework explaining under which circumstances invitations are being accepted and the speaker gives way for an intervention. In this analytical step, every of the 14,595 instances, where an MP in the chamber tries to intervene, represents one observation with a dichotomous dependent variable indicating whether the respective attempt has been successful or not. Using a Generalised Linear Model (GLM), we study the association between this outcome and ideological divergences as well as government–opposition constellations.Footnote 8

Both model specifications include fixed effects incorporating speaking and (potential) intervening MPs, as well as for the electoral term. Including any time‐invariant MP characteristics is crucial, as interventions are strategic decisions at the individual MP level. Furthermore, the term fixed effect accounts for all election period‐specific features.

In a final estimation step, we test the robustness of the presented explanations and explore further behavioural patterns among MPs when seeking and avoiding direct interactions with their fellow legislators. These further explanations were theoretically introduced earlier and examine gender (binary variable indicating the gender of the inviting and invited MPs), seniority (number of years the respective MP has spent in the German Bundestag) and mandate type (binary variable indicating whether the invited and inviting MPs hold direct or list mandates). Additionally, our estimation strategy covers government–opposition‐related dynamics such as recurring governments and grand coalitions to draw a fine‐grained picture of when discourse unfolds.

Results

In this section, we analyse and discuss the results of our models, followed by an exploration of further explanatory approaches.

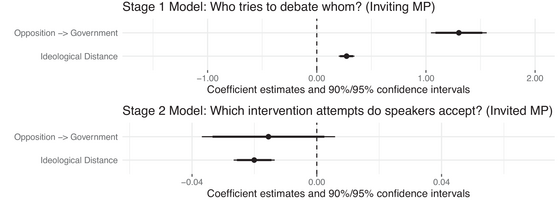

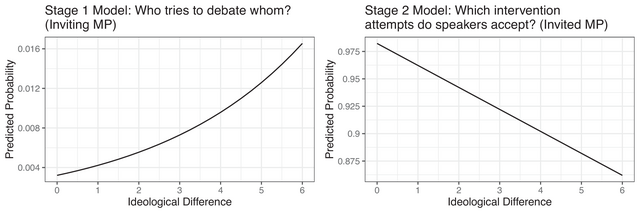

Figure 4 illustrates the results for both stages of our framework. In the first step of the analysis, we estimate the effects of ideological differences and government participation on the willingness of MPs in the chamber to invite speakers for a dialogue as part of an intervention. Our Poisson regression models in stage 1 indicate that MPs in the chamber are systematically more likely to seek dialogue with politically more distant speakers. For every difference score on our six‐point scale, the number of intervention attempts increases by a factor of 1.32 on average. This effect is highly significant and in line with hypothesis H1a.

Figure 4. Regression coefficients with 90 per cent (wide) and 95 per cent (narrow) confidence intervals for both framework stages. Stage 1 uses a Poisson regression; estimates for stage 2 are grounded on a generalised linear model. Fixed effects on legislative period, (potential) questioner ID and speaker ID.

Furthermore, intervention attempts are observed more frequently in situations where opposition MPs seek interaction with speakers from the governing majority. Compared to all other constellations, intervention attempts are 4.22 times more likely to occur in situations where an opposition MP in the chamber faces a speaker from the government majority. This effect is highly significant and in line with hypothesis H2a.

In the second step of the analysis, we predict the effects of the same factors (ideological differences and government–opposition dynamics) on the probability that speakers give way for an intervention and discourse eventually unfolds. Figure 5 depicts our predictions for both stages. Our models indicate that the probability of speakers accepting an intervention by fellow MPs in the chamber is systematically decreasing the more politically distant they are. The predicted marginal probability that speakers follow an invitation by a fellow MP who is about one difference point away from themFootnote 9 is on average around 96 per cent. If, by contrast, there is an ideological difference of around five points between the two MPs involved, such as between the FDP and the Left in the 18th legislative term of the German Bundestag, the predicted probability that speakers will accept the invitation is at about 85 per cent. Thus, increasing ideological differences are highly significantly associated with decreasing probabilities that interposed questions are allowed and discourse eventually unfolds. While this finding is in line with H1b, we only find tentative evidence regarding the anticipated effect for government–opposition dynamics among invited MPs. As also illustrated in Figure 4, the effect of opposition MPs inviting government colleagues is negative but statistically insignificant.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities based on stage 1 and 2 models indicating who invites whom for a dialogical interaction (stage 1; Poisson) and when these invitations are being accepted (stage 2; generalised linear model) dependent on an increasing ideological difference.

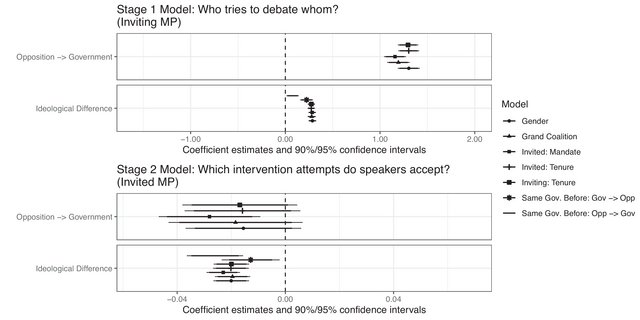

To test the robustness of our main findings for ideological heterogeneity and government–opposition dynamics, we empirically evaluate several further explanations. First, we run regression models that control for individual‐level effects related to gender, seniority and mandate type. Second, we test further scenarios related to grand coalitions (coalitions between Conservatives and Social Democrats) and the behaviour of opposition and government in recurring government compositions. Figure 6 holds the main coefficients for these models in both stages of our framework. While we find interesting patterns for further research in these models, ideological distance remains significant for all robustness specifications.Footnote 10

Figure 6. Further explanations of main regression coefficients with 90 per cent (wide) and 95 per cent (narrow) confidence intervals for both framework stages. Stage 1 uses a Poisson regression; estimates for stage 2 are grounded on a generalised linear model. Please find full model specifications in the Online Appendix (Tables A6 and A7).

Turning towards these MP characteristics, we observe further insightful patterns complementing our theoretical reflections on the strategic risks and opportunities associated with seeking and avoiding discourse: In line with our contention that discourse in parliament serves as an opportunity for MPs to present themselves and their abilities to a wide audience, less tenured legislators seek these interactions more often than their more experienced colleagues. At the same time, MPs are increasingly inclined to accept invitations for discursive interaction with increasing levels of parliamentary experience. This is very plausible, as the informational disadvantage that characterises the role of the invited MP becomes a diminishing risk, both through growing knowledge of the opponent's positions and through increasing confidence in their rhetorical skills.

Invitations for discursive interaction are significantly more common among MP pairs where both involved legislators are men (see Table A6). This is in line with the extensive literature highlighting gendered patterns shaping legislative environments. Further, we see MPs holding a direct mandate to be more likely to be more inclined to seek discourse at both stages of our analysis. While the observation is that mandate types are associated with divergent behavioural patterns of legislative behaviour, future research might address the role of varying electoral incentives as another guiding principle for seeking and avoiding interaction.

In summary, the very factors that encourage an invitation to discourse during legislative debates ultimately make it less likely for the exchanges to unfold. First, with diverging political preferences, MPs in plenary increasingly seek dialogue with the speaker. However, these same disagreements prompt the speaker to avoid direct confrontation with fellow legislators. Second, opposition MPs more frequently attempt to engage in discourse with members of the governing majority. Yet, we find only tentative evidence that these efforts lead to meaningful discursive exchanges.

Conclusion

In this article, we have examined the role of ideological differences and government–opposition dynamics in the formation of discursive exchanges between MPs during legislative debates. Although extant research highlights the dialogical nature of parliamentary debates, the empirical examination of these dynamics going beyond purely qualitative illustrations was, so far, mostly limited to unilateral utterances, e.g., interjections or applause. By distinguishing between MPs who invite others for a dialogical interaction and their counterparts who are being invited, we introduced a framework to analyse the formation of parliamentary discourse that contributes to this strand of literature. Using the exceptionally well‐documented empirical case of interventions in the German Bundestag between 1990 and 2020, we provide evidence supporting the notion of diverging ideological preferences and government–opposition dynamics harbouring countervailing implications for different MPs and ultimately for parliamentary discourse to eventually unfold.

We find that while increasing ideological differences between two legislators are associated with increasing probabilities for one of them seeking dialogue with the other, MPs receiving invitations from ideologically distant colleagues are more likely to avoid instances of discursive exchange with policy‐makers advocating more distant preferences. At the same time, speakers are less likely to accept invitations from ideologically distant MPs. As a result, ideologically distant MPs invite each other for dialogical interactions more frequently than those advocating more aligned political positions. At the same time, speakers are inclined to avoid discursive interactions with MPs with whom they share greater political differences.

This is a finding that certainly poses challenges for democratic discourse. In recent decades, new right‐of‐centre players have emerged in Western political systems, which have contributed to the increasing polarisation of party competition. If an increasing share of the relationships between MPs in Western parliaments is characterised by greater ideological differences, we must assume that discursive interaction will also take place less frequently.

We observe similar, yet not identical, patterns when considering the discursive behaviour of government and opposition MPs. Attempts to intervene are more prevalent in situations where legislators from the opposition face speakers from the government majority than in all other MP combinations. These same invitations are less likely to be accepted by the speaker. However, this effect is not statistically significant. Thus, government actors are not systematically more likely to evade interaction with the opposition than with their government colleagues, even though there is a tendency for them to do so.

Our empirical strategy is associated with certain limitations, which can serve as a departing point for future research. While it comes with the great advantage that we can test our hypotheses on manifest discourse proceedings, our estimation strategy remains a correlational approach. Hence, establishing causal evidence in this field remains a pressing issue.

Further, our analysis is limited to the empirical case of the German Bundestag. While there are multiple both empirical and practical reasons motivating this case selection, comparative approaches shedding light on potential differences in discourse seeking and avoidance dynamics in other parliamentary systems with their distinct debating cultures is a compelling avenue for future research.

Another limitation lies in the fact that our empirical strategy considers MPs' reasoning over risks and pitfalls associated with seeking and avoiding discursive interactions with fellow legislators as isolated phenomena. Applying our theoretical framework, future research could take path dependencies into account and explore how both inviting and invited MPs may consider the previous behavioural patterns of their counterparts when making these decisions.

Furthermore, since MPs seek discursive interaction with one another, hoping that it pays off with regard to their public image as legislators, the question of whether discursive exchanges are perceived by voters remains to be addressed. There is good reason to expect that this is the case, given that the long‐standing notion of active engagement in parliamentary debates leading to higher levels of media attention has received strong empirical support in recent years (e.g., Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012; Lupacheva & Mölder, Reference Lupacheva and Mölder2024; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Thesen, Jennings and De Vries2023). Thus, although it can be argued that direct interaction between competing politicians is a particularly attractive and informative event for media outlets covering day‐to‐day politics, the pay‐offs of discursive interaction remain to be explored systematically.

Another compelling research agenda might consider taking the debate itself into account while considering public opinion as an environmental factor influencing the perceived pressure to seek opportunities for enhancing an MP's public perception through dialogical interaction. This way, MPs might be more inclined to seek discursive interaction when their parties suffer losses in public support or when debating issues which are particularly salient in the electorate. MPs might also be more willing to debate issues they own (i.e., issues they are perceived as particularly competent on) with fellow colleagues. Taking these types of debate‐level characteristics in interaction with public opinion into account could be a very fruitful avenue for future research.

Finally, plenary protocols are a valuable source for studying parliamentary behaviour. However, they disregard behaviour that goes beyond what is captured in the text. For instance, not every MP holding a mandate in a parliament is present in the chamber at any point of a parliamentary sitting, but this is a piece of information which typically is not documented in plenary minutes. Although it can be argued that participation or abstention from debates is a conscious decision by MPs who are well aware of the list of speakers on the sitting day and who have access to the chamber at any time, recent advancements in multimodal methods could potentially soon also advance research on debating decisions. This way, information derived from video footage could determine the subset of MPs who actually are present at any point in time (Nyhuis et al., Reference Nyhuis, Ringwald, Rittmann, Gschwend and Stiefelhagen2021). Audiovisual studies would further help answer questions centred around non‐verbal communication between MPs, such as the way a potential inviting MP attracts attention and how this is recognised by the invited MP (Arnold & Küpfer, Reference Arnold and Küpfer2024).

Our findings contribute to our understanding of dialogical interaction in parliament, both with regard to their prerequisites, their emergence and the strategic considerations associated with them to all MPs involved. We demonstrate that MPs' engagement in interactions with their peers is influenced by both ideological factors and their individual roles in specific instances of interaction as well as the roles of their parties within the established government–opposition dynamics. Thus, this study offers a new perspective on the nature of parliamentary debates and the behaviour of individual MPs in them by distinguishing between inviting and invited MPs. Further, our proposed framework guiding our analysis contributes to future research on discursive elite interaction even beyond the legislative realm.

Acknowledgements

Justin Braun, Christina‐Marie Juen, Tristan Klingelhöfer, Corinna Kroeber, Simon Munzert, Jochen Müller and Christian Stecker provided incredibly helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We thank Tim Rieth for his excellent research assistance as well as the three anonymous reviewers for their tremendously constructive comments. The article was created as part of the project The Populist Challenge in Parliaments, funded by the DFG (407215771).

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The replication data for this article are publicly available on Harvard Dataverse at Koch, Elias; Küpfer, Andreas; 2025, ‘Replication Data for The Politics of Seeking and Avoiding Discourse in Parliament’, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8K9NAN.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Performance evaluation between both annotators.

Table A2: Summary statistics of the Stage 2 dataset (Main Variables)

Table A3: Summary statistics of the Stage 2 dataset (Main Variable Committee)

Table A4: Summary statistics of the Stage 2 dataset (Alternative Variables)

Figure A1: Average word count of interventions and answers per party.

Figure A2: Questioner (left column) and speaker (right column) dynamics of each party inviting for and receiving interventions.

Figure A3: Questioner (left column) and speaker (right column) dynamics of either opposition of government parties with the associated decision (center column).

Figure A4: Share of intra‐faction intervention attempts per legislative period.

Figure A5: Share of intra‐government or intra‐opposition intervention attempts per legislative period.

Table A5: Regression results for both framework stages based on 37,046,639 cases of potential question situations (Stage 1) and 14,595 cases of actual question situations (Stage 2).

Figure A6: Robustness checks for stage 1 of our framework.

Figure A7: Robustness checks for stage 2 of our framework

Figure A8: Coefficients for both stages after including committee membership as a fixed effect.

Table A6: Stage 1 models for further explanations based on gender, tenure, mandate‐type, grandcoalition, and government‐opposition behaviour.

Table A7: Stage 2 models for further explanations based on gender, tenure, mandate‐type, grand coalition, and government‐opposition behaviour.