There have been repeated attempts to reform the mental healthcare system in Ukraine during its years of independence; most notably, a goal was set in the ‘Concept of the Development of Mental Health Care’. The goal was ‘to create an integral, effective system of mental health care that would function in a single interdepartmental space, ensure improvements to the quality of life and observance of human rights and freedoms’. It was approved by the Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine (no. 1018-p), and the Concept Implementation Plan was developed between 2018 and 2021. During this period, initiatives and projects focusing on the field of mental health gradually began to appear in Ukraine.

Among these initiatives was the Ukrainian–Swiss Mental Health for Ukraine project, which is funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). In 2019, the SDC’s consortium representatives from the Implemental Worldwide Community Interest Company (CIC) visited Lviv. They spent time with stakeholders, learnt about the challenges associated with providing mental healthcare in Ukraine and developed key recommendations. 1,2 Among these recommendations was the development of organisational structures, which would allow people to come together and take collective responsibility for the development of mental healthcare systems in Ukraine. The report proposed an organisational structure referred to as a local implementation team (LIT). This is similar to the ‘local implementation teams’ developed to implement the National Framework for Mental Health in the UK. 3

Chervonohrad (now Sheptytskyi) LIT

Following Implemental’s recommendations, Chervonohrad (officially renamed Sheptytskyi in 2024) became the first city in Ukraine to establish a LIT in the mental health field. Reference Power and Suvalo4 At the time the team was established, the city was officially named Chervonohrad; however, in September 2024, Ukraine renamed it Sheptytskyi. As noted in the title, the team comprised intersectoral bodies, this term referring to collaborative groups of stakeholders from various sectors that are relevant to mental health, including healthcare, social services, education and police. The LIT’s purpose was to plan, implement, monitor and improve services in the field of mental health.

The regulation stipulated that the LIT should:

-

(a) Assess mental health needs in the community.

-

(b) Determine the priorities and risks, then plan and implement activities to improve community services.

-

(c) Arrange meetings to draw people’s attention to, and solve the problems related to, planning and providing mental health services.

-

(d) Make and follow yearly activity plans aimed at developing, implementing and providing community mental health services. These should be informed by professional recommendations, as well as by the specific needs of the local population with mental health needs. Learning should derive from other districts, communities and regions in Ukraine.

-

(e) In the planning stages, measures should aim to improve practice within regional administrative bodies, social service providers and other interested parties.

Formation of the LIT was guided by the City Governance and approved by the City Council; chosen participants came from a range of sectors, and members included the following:

-

(a) the deputy mayor as head of the LIT

-

(b) the head of the Chervonohrad Centre for Primary Medical and Sanitary Care

-

(c) the deputy head of the Labour and Social Protection Administration

-

(d) an education specialist

-

(e) an addiction specialist from the Municipal Enterprise Central District Hospital

-

(f) the head of Chervonohrad City Organisation of Disabled Youth

-

(g) public representatives.

Outcomes and activities

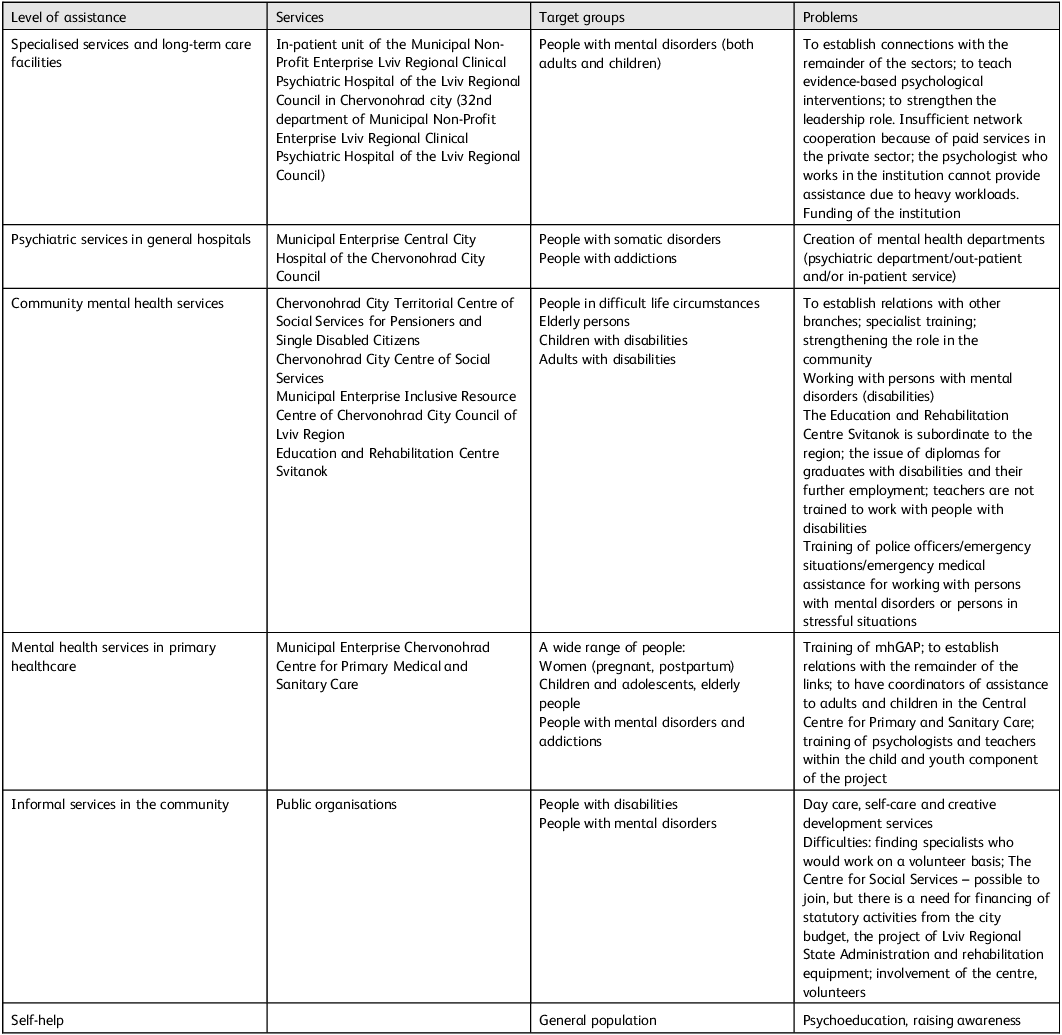

The LIT identified gaps and needs in Chervonohrad’s (now Sheptytskyi’s) mental health services, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Identified needs in Chervonohrad (now Sheptytskyi) mental health services

mhGAP, World Health Organization Mental Health Gap Action Programme.

Among the key activities delivered, the LIT:

-

(a) Facilitated World Health Organization Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) training, in cooperation with local non-governmental organisations (NGOs), for health and mental healthcare specialists.

-

(b) Facilitated knowledge exchange meetings for experts and residents in the community, with support from NGOs.

-

(c) Members took part in leadership training in mental health.

-

(d) Established organised training within a psychiatric hospital: ‘An educational and mentoring project for the formation of teamwork with a rehabilitation approach’.

-

(e) Conducted a social media-based information campaign on the topic of mental health, with support from the city council.

-

(f) Another notable outcome of the LIT was the situational analysis of mental health services in the city of Chervonohrad (now Sheptytskyi). For this, the WHO methodology ‘mhGAP methodology for situational analysis: a minimum data set for the implementation of mhGAP at the level of primary care’ was used.

Challenges and lessons

The activities of the LIT took place during periods of difficulties experienced by the country. Challenges included the second stage of the transformation of healthcare system financing on 1 April 2020, decentralisation and the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, the regularity of LIT meetings was disrupted. Despite this, LIT participants noted the importance of the previous work done and declared the need for further joint activities.

In addition, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 caused a humanitarian crisis and dramatically increased mental health needs. Despite these challenges, the LIT provided a dedicated platform in the field of mental health, enabling more flexible and effective responses to these challenges. Consequently, trained professionals better understood mental health needs and knew where to look for resources to meet them. There were high level levels of understanding of mental health and local needs, as well as pre-established referral routes and processes of interaction among participants in the field of mental health. Subsequently, the presence of local coordination bodies was shown to be relevant and effective under these new crisis conditions.

Participants also shared their own challenges encountered during LIT activities. First, the level of stigma and prejudice surrounding mental health hindered the development of services and interaction among the various parties involved. Moreover, at national and regional levels, there was a reported lack of community understanding of mental health policies, intersectoral coordination and flexibility in the provision of services, which affected problem-solving. As might be expected with Ukraine being a middle-income country, there was also a notable lack of funding, human resources, material resources and local leadership within the field of mental health. Reference Metreau, Young and Eapen5 These challenges were tackled through a combination of training, meetings with service users and decisions made by the local city council.

Recommendations about the activities of local mental health teams included the following:

-

(a) LITs should be created at a regional district level or in the district centre, and should involve representatives from these communities.

-

(b) LIT members should have roles in various employment departments (healthcare, social sphere, education, employment, police). There should also be civil society members (representatives of religious communities, NGOs working in mental health, etc.).

-

(c) The group should be open to the public sector, especially community organisations representing people with mental health disorders and their families.

-

(d) Involvement of service users is crucial for the promotion of the group’s activities, advocating for better care and overcoming stigma and prejudice.

-

(e) Regular meetings are an essential element of routine work, planning and lobbying.

-

(f) All decisions should be documented in order to influence budget-setting processes and funding of agreed activities.

-

(g) Gaps identified in mental healthcare should be presented in the form of requests to the relevant structures, in order to secure funding and tackle needs.

-

(h) Leadership and vision in the local community/district is a key element.

-

(i) Professional training in different fields is key to raising awareness and ensuring the implementation of human-centred and evidence-based practices.

-

(j) Support from an external facilitating organisation is very helpful for LIT members. This role can include raising of awareness, psychoeducation and explanation of evidence-based, recovery- and human rights-oriented mental health frameworks.

-

(k) Willingness to learn and be open to innovations to improve services in the local community is essential.

Conclusions and implications

It can be concluded that LITs are an extremely important means of communicating, assessing needs and coordinating mental healthcare. LITs have now proven to be beneficial in both the UK (a high-income country) and Ukraine (a middle-income country). This has strong implications for mental health reforms globally because it is underfunded globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. LITs provide a solution that is cost-effective, scalable, led by local stakeholders and adaptable in the face of national emergencies. In this instance, the LITs not only upheld their work in the face of a global pandemic but also provided a buffer against the unwanted consequences of war. LITs create a permanent platform that has community involvement and support from local authorities. They form a space for the different perspectives of mental health needs to be heard and used to inform decision-making. The formalisation of the group is an important step in lobbying for the budgeting of necessary services in the community and/or seeking external funding (grants, regional or state budgets). Support from an external facilitating organisation is also helpful to raise awareness, provide psychoeducation and ensure that mental health frameworks used by the LIT are recovery and human rights oriented.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this paper are included within the article and its supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of this paper.

Funding

This article was funded by the Mental Health for Ukraine project, which is a development project funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). The project is jointly implemented by the consortium of GFA Consulting Group GmbHm, Implemental Worldwide Community Interest Company (CIC), the Ukrainian Catholic University Lviv and the University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich.

Declaration of interest

This article was written and edited by members of the Mental Health for Ukraine project, as well as by Implemental Worldwide CIC. The views and opinions presented in this paper are those of the authors and may not represent the views of the Mental Health for Ukraine project team, Implemental Worldwide CIC or the SDC.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.