Introduction

Charities address some of the world’s most important and neglected problems (MacAskill, Reference MacAskill2015; Singer, Reference Singer2019). Some of the highest-impact (e.g., Against Malaria Foundation; GiveWell, 2021) and most famous (e.g., American Red Cross; Charity Navigator, 2022) charities rely on asking people to give money for no tangible reward (Bendapudi et al., Reference Bendapudi, Singh and Bendapudi1996). As a result, effective fundraising is both critical and challenging for nonprofits. We conduct a meta-review of systematic reviews to identify ‘what works’ to promote charitable donations. Our aim is to provide practitioners and researchers with a resource for identifying which interventions have been investigated, which ones work, and which do not. By charitable donations, we mean the altruistic transfer of money from a person to an organisation that helps people in need (after Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b). We catalogue systematic reviews because they: (a) search for and assess the evidence about which interventions work (Hulland & Houston, Reference Hulland and Houston2020; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2018), (b) describe the effectiveness of interventions in a way that can be systematically compared, and (c) help practitioners and researchers understand which interventions have good external validity and generalisability (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2018). By synthesising systematic reviews, we can provide stronger recommendations for evidence-informed decision-making than by reviewing individual studies alone (HM Treasury, 2020).

This Meta-Review Investigates Which Hypothesised Drivers of Charitable Giving Have Robust Support

There are several existing reviews of evidence-based charitable promotion (e.g., Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b; Bendapudi et al., Reference Bendapudi, Singh and Bendapudi1996; Oppenheimer & Olivola, Reference Oppenheimer and Olivola2010; Wiepking & Bekkers, Reference Wiepking and Bekkers2012). We build on these reviews by conducting a meta-review, also known as an umbrella review or overview of reviews. Meta-reviews are similar to systematic reviews because they systematically search for and appraise existing research to answer a focused research question. A systematic review aggregates primary studies, but a meta-review aggregates systematic reviews. This allows meta-reviews to cover a wider scope than traditional systematic reviews (Becker & Oxman, Reference Becker, Oxman, Higgins and Green2011). Systematic reviews employ a comprehensive, reproducible search strategy to identify primary research into the effects of an intervention (e.g., providing information about recipients) on a specific outcome (e.g., size of donation) across contexts, while also assessing which situational factors influence those effects. Meta-analyses may form part of a systematic review and use statistics to estimate the average strength of those effects (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019). Research standards and practices differ across disciplines, and even within a discipline (e.g., psychology), findings about ‘what works' to increase charitable donations can conflict with each other due to inconsistent pre-registration, participant demographics, and publication bias (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). Charitable donation as a behaviour is therefore a good fit for a meta-review because useful research on the topic is fragmented across many disciplines including marketing, economics, psychology, and others (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b; Bendapudi et al., Reference Bendapudi, Singh and Bendapudi1996; Mazodier et al., Reference Mazodier, Carrillat, Sherman and Plewa2020; Pham & Septianto, Reference Pham and Septianto2019; Rothschild, Reference Rothschild1979; Septianto et al., Reference Septianto, Tjiptono, Paramita and Chiew2020; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Buil and de Chernatony2017). Our meta-review aggregates systematic reviews on charitable giving. Where included systematic reviews are accompanied by a meta-analysis, we aggregate those meta-analyses into a meta-meta-analysis to quantify and compare the strength of interventions to promote charitable giving.

We organise the presentation of results from our meta-review using an established and highly-cited model of drivers for charitable donations (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b). This narrative review proposed a model where donors are more likely to give when they are prompted to donate (solicitation) to a cause they know about (awareness of need), if the cost is low enough (costs and benefits) for the effect it has on society (altruism). According to this model, people also donate if they think doing so will make them look good in the eyes of others (reputation), make them feel good (psychological benefits), align with what is important to them (values), and make a meaningful difference (efficacy). Bekkers and Wiepking classified different interventions found in primary research into one or more of these drivers, for example, by discussing how tax deductibility decreases the costs of donation. However, unlike a systematic review, their narrative review approach did not account for publication bias or pre-register inclusion and exclusion criteria; it also did not estimate the relative effectiveness of each driver for influencing charitable donations. In our meta-review, we seek to comprehensively identify all interventions that increase charitable behaviour and that have been the focus of an existing systematic review. Because systematic reviews often include a meta-analysis, which summarises the quantitative effect size or ‘strength’ of an intervention on charitable donation behaviour, our meta-review will also assess the effectiveness of each driver (e.g., awareness, costs and benefits) in increasing charitable donation behaviour. In this review, we use the Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) classification to identify which drivers have been the most studied, which have not, and which drivers appear to most influence charitable donation behaviour.

Aim

In this meta-review, we aim to:

1. synthesise the systematic reviews on interventions designed to promote charitable donations across disciplines

2. combine the quantitative effect size estimates from meta-analyses included in the systematic reviews and use meta-meta-analysis to estimate the effectiveness of interventions to promote charitable donations

3. interpret the findings by classifying each intervention according to a widely-used model (Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) and best-practice guidelines for evidence-informed decision-making (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Schünemann, Tugwell and Knottnerus2011; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019)

Method

We conducted a meta-review of systematic reviews using established recommendations (Becker & Oxman, Reference Becker, Oxman, Higgins and Green2011; Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009; Khangura et al., Reference Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw and Moher2012; Pollock et al., Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2017; World Health Organisation, 2017) to synthesise the literature on how to increase charitable donations. We conducted a meta-meta-analysis on any meta-analyses reported in the included systematic reviews. A meta-meta-analytic approach was necessary because it permitted the use of all available information from the original meta-analyses to calculate a pooled effect while accounting for variability at both the study and meta-analysis level. Our meta-review was prospectively registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/465ej/). Details of our search strategy including search strings, screening and selection of studies, data extraction and quality assessment, quantitative synthesis, and certainty assessment are presented in Supplementary File 1 and summarised below.

We searched Scopus, PsycINFO (Ovid), Web of Science, and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects due to their broad but non-overlapping corpora, and their coverage of topic areas relevant to our research question. We conducted searches on July 17th, 2019 and March 4th, 2021. We developed terms for identifying systematic reviews informed by a comprehensive typology of review methods (Grant & Booth, Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Schünemann, Tugwell and Knottnerus2009). Terms for charitable donations as outcomes included: altruis*, charit*, philanthro*, donat*, pledge*, or non-profit. Titles and abstracts were screened in duplicate; full-text articles were screened in duplicate; and included papers were extracted in duplicate. Disputes were resolved by discussion between reviewers, consulting a senior member of the team, if necessary.

Our inclusion criteria were (1) systematic reviews, scoping reviews, or similar reproducible reviews (i.e., those with a reproducible method section describing a searching and screening procedure); (2) reviews describing monetary charitable donations; (3) reviews assessing any population of participants in any context; and (4) written in English (due to logistical constraints) and (5) peer-reviewed (although no papers ended up being excluded on the basis of this criteria). Exclusion criteria were (1) primary research reporting new data (e.g., randomised experiments); (2) non-systematic reviews, theory papers, or narrative reviews; (3) reviews on cause-related marketing; and (4) reviews of other kinds of prosocial behaviour (e.g., honesty, non-financial donations). We also conducted forward and backward citation searching (Hinde & Spackman, Reference Hultcrantz, Rind, Akl, Treweek, Mustafa, Iorio, Alper, Meerpohl, Murad, Ansari, Katikireddi, Östlund, Tranæus, Christensen, Gartlehner, Brozek, Izcovich, Schünemann and Guyatt2015) via Scopus with no subject or publication requirements. We developed a data extraction template to capture information from each included review and assessed the quality of the included reviews using an abbreviated list of quality criteria drawn from AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al., Reference Singer2017). We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence across all reviews for each combination of intervention and outcome (Guyatt et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green2011; Higgins et al., Reference Hulland and Houston2019; Hultcrantz et al., Reference Jung, Seo, Han, Henderson and Patall2017). More information about and results of these quality assessments are available in Supplementary File 1.

Many, but not all, systematic reviews also conducted meta-analyses to quantify the size of effects on donations. So we could compare the relative size of effects between these different meta-analyses, we conducted a meta-meta-analysis, or second-order meta-analysis (Hennessy et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019; Schmidt & Oh, Reference Septianto, Tjiptono, Paramita and Chiew2013). These models are the best practice for synthesising effects across different meta-analyses because they can compare effect sizes on a common metric while accounting for variability both within- and between reviews (Hennessy et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019; Schmidt & Oh, Reference Septianto, Tjiptono, Paramita and Chiew2013). Our primary outcome was the overall pooled effect size of intervention on donation size. A secondary outcome was donation incidence—whether a donation of any size was provided—because many reviews reported on this dichotomous outcome. We extracted quantitative estimates from reviews that included meta-analyses and converted them to the most commonly used metric (r) using the compute.es package (Del Re, Reference Engel2020) in R (R Core Team, Reference Richard, Bond and Stokes-Zoota2020). We conducted a meta-meta-analysis using the meta sem package (Cheung, Reference Conigrave2014) and msemtools packages (Conigrave, Reference Coyne, Padilla-Walker, Holmgren, Davis, Collier, Memmott-Elison and Hawkins2019). We used random-effects meta-analyses to calculate pooled effects for each mechanism and each outcome, then conducted moderation analyses to assess whether interventions were homogenous within mechanism and outcome. Raw data and code for reproducing the analyses are available at https://osf.io/465ej/.

Results

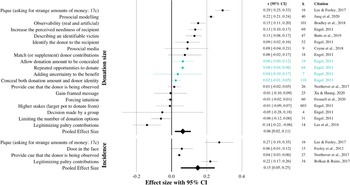

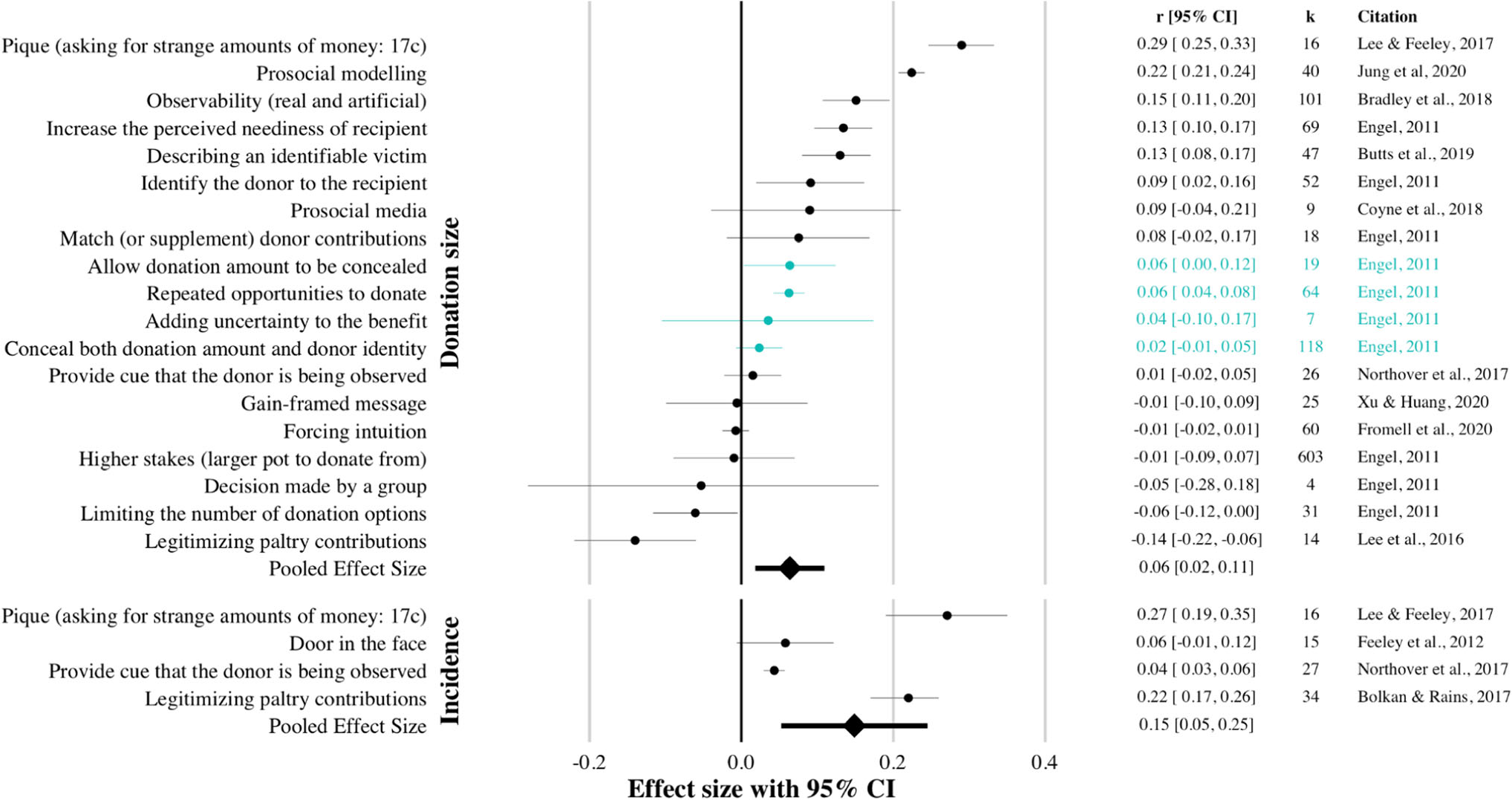

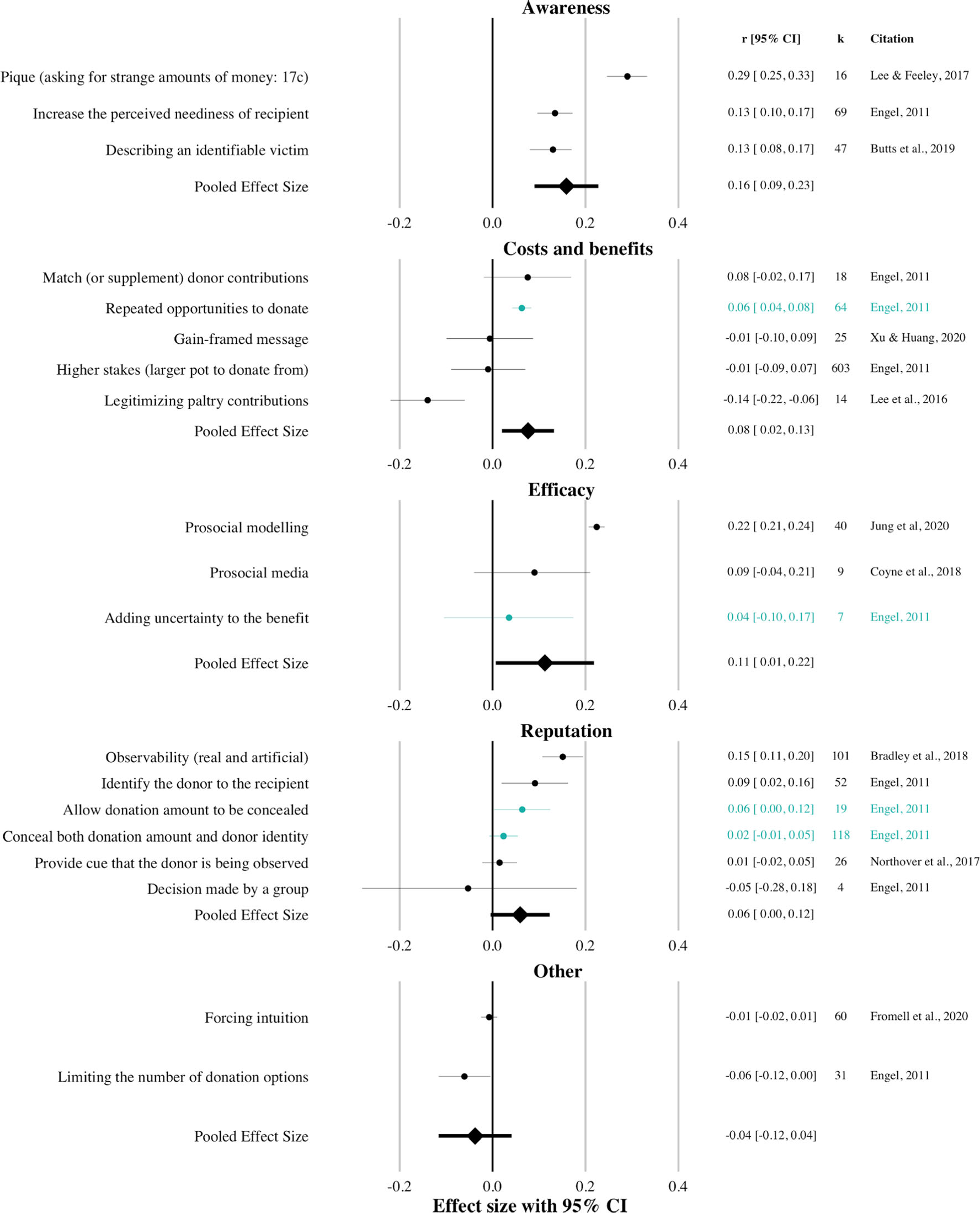

We organise the results as follows. First, we describe the reviews identified and included through the systematic search (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Second, we present a meta-meta-analysis for the pooled effect of interventions on donation size and donation incidence (Fig. 2). Third, we organise the included interventions using the model of drivers for charitable donations from Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) to present a meta-meta-analysis of interventions for each driver (Fig. 3) and describe each intervention in detail.

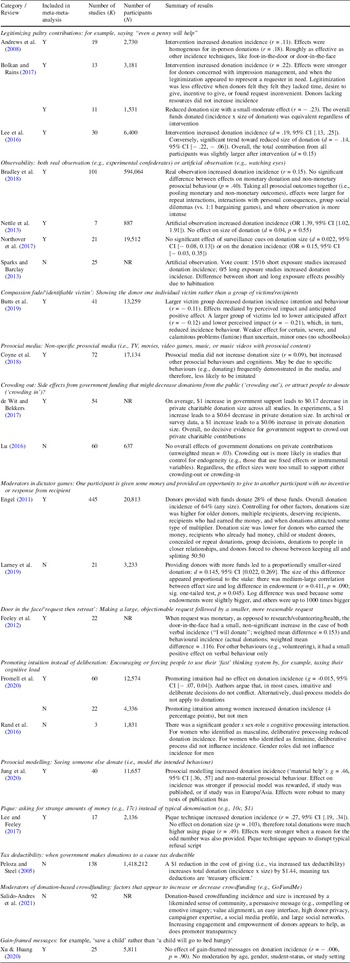

Table 1 Summary of included reviews

Category / Review |

Included in meta-meta-analysis |

Number of studies (K) |

Number of participants (N) |

Summary of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Legitimizing paltry contributions: for example, saying “even a penny will help” |

||||

Andrews et al. (Reference Andrews, Carpenter, Shaw and Boster2008) |

Y |

19 |

2,730 |

Intervention increased donation incidence (r = .11). Effects were homogenous for in-person donations (r = .18). Roughly as effective as other incidence techniques, like foot-in-the-door or door-in-the-face |

Bolkan and Rains (Reference Bolkan and Rains2017) |

Y |

13 |

3,181 |

Intervention increased donation incidence (r = .22). Effects were stronger for donors concerned with impression management, and when the legitimization appeared to represent a requester in need. Legitimization was less effective when donors felt they felt they lacked time, desire to give, incentive to give, or found request inconvenient. Donors lacking resources did not increase incidence |

Y |

11 |

1,531 |

Reduced donation size with a small-moderate effect (r = − .23). The overall funds donated (incidence x size of donation) was equivalent regardless of intervention |

|

Lee et al. (Reference Mazodier, Carrillat, Sherman and Plewa2016) |

Y |

30 |

6,400 |

Intervention increased donation incidence (d = .19, 95% CI [.13, .25]). Conversely, significant trend toward reduced size of donation (d = − .14, 95% CI [− .22, − .06]). Overall, the total contribution from all participants was slightly larger after intervention (d = 0.15) |

Observability: both real observation (e.g., experimental confederates) or artificial observation (e.g., watching eyes) |

||||

Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Lawrence and Ferguson2018) |

Y |

101 |

594,064 |

Real observation increased donation incidence (r = 0.15). No significant difference between effects on monetary donation and non-monetary prosocial behaviour (p = .40). Taking all prosocial outcomes together (i.e., pooling monetary and non-monetary outcomes), effects were larger for repeat interactions, interactions with personal consequences, group social dilemmas (vs. 1:1 bargaining games), and where observation is more intense |

Nettle et al. (Reference Nettle, Harper, Kidson, Stone, Penton-Voak and Bateson2013) |

Y |

7 |

887 |

Artificial observation increased donation incidence (OR 1.39, 95% CI [1.02, 1.91]). No effect on size of donation (d = 0.04, p = 0.55) |

Northover et al. (Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017) |

Y |

21 |

19,512 |

No significant effect of surveillance cues on donation size (d = 0.022, 95% CI [− 0.08, 0.13]) or on the donation incidence (OR = 0.15, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.35]) |

Sparks and Barclay (Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2013) |

N |

25 |

NR |

Artificial observation. Vote count: 15/16 short exposure studies increased donation incidence; 0/5 long exposure studies increased donation incidence. Difference between short and long exposure effects possibly due to habituation |

Compassion fade/‘identifiable victim’: Showing the donor one individual victim rather than a group of victims/recipients |

||||

Butts et al. (Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019) |

Y |

41 |

13,259 |

Larger victim group decreased donation incidence intention and behaviour (r = − 0.11). Effects mediated by perceived impact and anticipated positive affect. A larger group of victims led to lower anticipated affect (r = − 0.12) and lower perceived impact (r = − 0.21), which, in turn, reduced incidence behaviour. Weaker effect for certain, severe, and calamitous problems (famine) than uncertain, minor ones (no schoolbooks) |

Prosocial media: Non-specific prosocial media (i.e., TV, movies, video games, music, or music videos with prosocial content) |

||||

Coyne et al. (Reference Crocker, Canevello and Brown2018) |

Y |

72 |

17,134 |

Prosocial media did not increase donation size (r = 0.09), but increased other prosocial behaviours and cognitions. May be due to specific behaviours (e.g., donating) frequently demonstrated in the media, and therefore, less likely to be imitated |

Crowding out: Side effects from government funding that might decrease donations from the public (‘crowding out’), or attract people to donate (‘crowding in’)? |

||||

de Wit and Bekkers (Reference Everett, Caviola, Kahane, Savulescu and Faber2017) |

Y |

54 |

NR |

On average, $1 increase in government support leads to $0.17 decrease in private charitable donation size across all studies. In experiments, a $1 increase leads to a $0.64 decrease in private donation size. In archival or survey data, a $1 increase leads to a $0.06 increase in private donation size. Overall, no decisive evidence for government support to crowd out private charitable contributions |

Lu (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2016) |

N |

60 |

637 |

No overall effects of government donations on private contributions (unweighted mean = .03). Crowding out is more likely in studies that control for endogeneity (e.g., those that use fixed effects or instrumental variables). Regardless, the effect sizes were too small to support either crowding-out or crowding-in |

Moderators in dictator games: One participant is given some money and provided an opportunity to give to another participant with no incentive or response from recipient |

||||

Y |

445 |

20,813 |

Donors provided with funds donate 28% of those funds. Overall donation incidence of 64% (any size). Controlling for other factors, donations size was higher for older donors, multiple recipients, deserving recipients, recipients who had earned the money, and when donations attracted some type of multiplier. Donation size was lower for donors who earned the money, recipients who already had money, child or student donors, concealed or repeat donations, group decisions, donations to people in closer relationships, and donors forced to choose between keeping all and splitting 50:50 |

|

Larney et al. (Reference Larney, Rotella and Barclay2019) |

N |

21 |

3,233 |

Providing donors with more funds led to a proportionally smaller-sized donation: d = 0.145, 95% CI [0.022, 0.269]. The size of this difference appeared proportional to the stake: there was medium-large correlation between effect size and log difference in endowment (r = 0.411, p = .090; sig. one-tailed test, p = 0.045). Log difference was used because some endowments were slightly bigger, and others were up to 1000 times bigger |

Door in the face/‘request then retreat’: Making a large, objectionable request followed by a smaller, more reasonable request |

||||

Feeley et al. (Reference Funder and Ozer2012) |

Y |

22 |

NR |

When request was monetary, as opposed to research/volunteering/health, the door-in-the-face had a small, non-significant increase in the case of both verbal incidence (“I will donate”; weighted mean difference = 0.153) and behavioural incidence (actual donations; weighted mean difference = .116). For other behaviours (e.g., volunteering), it had a small positive effect on verbal behaviour only |

Promoting intuition instead of deliberation: Encouraging or forcing people to use their ‘fast’ thinking system by, for example, taxing their cognitive load |

||||

Fromell et al. (Reference Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2020) |

Y |

60 |

12,574 |

Promoting intuition had no effect on donation incidence (g = -0.015, 95% CI [− .07, 0.04]). Authors argue that, in most cases, intuitive and deliberate decisions do not conflict. Alternatively, dual-process models do not apply to donations |

N |

22 |

4,336 |

Promoting intuition among women increased donation incidence (4 percentage points), but not men |

|

Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016) |

N |

3 |

1,831 |

There was a significant gender x sex-role x cognitive processing interaction. For women who identified as masculine, deliberative processing reduced donation incidence. For women who identified as feminine, deliberative process did not influence incidence. Gender roles did not influence incidence for men |

Prosocial modelling: Seeing someone else donate (i.e., model the intended behaviour) |

||||

Jung et al. (Reference Lasswell2020) |

Y |

40 |

11,657 |

Prosocial modelling increased donation incidence (‘material help’): g = .46, 95% CI [.36, .57] and non-material prosocial behaviour. Effect on incidence was stronger if prosocial model was rewarded, if study was published, or if study was in Europe/Asia. Effects were robust to many tests of publication bias |

Pique: asking for strange amounts of money (e.g., 17c) instead of typical denomination (e.g., 10c, $1) |

||||

Lee and Feeley (Reference MacAskill2017) |

Y |

17 |

2,136 |

Pique technique increased donation incidence (r = .27, 95% CI [.19, .34]). No effect on donation size (p = .103), therefore total donations were much higher using pique (r = .49). Effects were stronger when a reason for the odd number was also provided. Pique technique appears to disrupt typical refusal script |

Tax deductibility: when government makes donations to a cause tax deductible |

||||

Peloza and Steel (Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2005) |

N |

138 |

1,418,212 |

A $1 reduction in the cost of giving (i.e., via increased tax deductibility) increases total donation (incidence x size) by $1.44, meaning tax deductions are ‘treasury efficient.’ |

Moderators of donation-based crowdfunding: factors that appear to increase or decrease crowdfunding (e.g., GoFundMe) |

||||

Salido-Andres et al. (Reference Salido-Andres, Rey-Garcia, Alvarez-Gonzalez and Vazquez-Casielles2021) |

N |

92 |

NR |

Donation-based crowdfunding incidence and size is increased by a likeminded sense of community, a persuasive message (e.g., compelling or emotive imagery; value alignment), an easy interface, high donor privacy, campaigner expertise, a social media profile, and large social networks. Increasing engagement and empowerment of donors appears to help, as does promoter transparency |

Gain-framed messages: for example, ‘save a child’ rather than ‘a child will go to bed hungry’ |

||||

Xu & Huang (Reference Xu and Huang2020) |

Y |

25 |

5,811 |

No effect of gain-framed messages on donation incidence (r = − .006, p = .90). No moderation by age, gender, student-status, or study setting |

Note. NR = not reported

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram of search and filtering of included reviews

Fig. 2 Pooled effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals from meta-analyses of interventions, grouped by outcome (donation size vs. incidence). Note: All effect sizes were converted to r, allowing for more meaningful comparisons between reviews. Light rows were interventions hypothesised to reduce donations. For these interventions, the sign of effects was reversed during analyses to calculate meaningful meta-meta-analytic pooled effect sizes

Fig. 3 Pooled effect of donation size (with 95% confidence intervals) from meta-analyses of interventions, grouped by hypothesised mechanism. Note: All effect sizes were converted to r to allow for meaningful comparisons between reviews. Light rows were interventions hypothesised to reduce donations. For these interventions, the sign of effects was reversed during analyses to calculate meaningful pooled effect sizes

Records Identified Through Systematic Search

As outlined in Fig. 1, we screened 2294 unique titles and abstracts. The team subsequently screened 60 full texts for eligibility, 21 of which were included. Of the included systematic reviews, 15 included meta-analyses of either donation size or donation incidence. Characteristics and summaries of each included review are presented in Table 1. Most full-texts were excluded for being reviews that were not systematic (Weyant, Reference Weyant1996). Ten focused on prosocial behaviour but did not report charitable donations distinctly, so unique effects on that outcome could not be discerned (Nagel & Waldmann, Reference Oppenheimer and Olivola2016). Six were on organisational behaviour that did not include charitable donations (e.g., the effects of nonprofits becoming more commercial; Hung, Reference Khangura, Konnyu, Cushman, Grimshaw and Moher2020) and five were primary research (Kinnunen & Windmann, Reference Lee, Moon and Feeley2013) (e.g., randomised experiments; Kinnunen & Windmann, Reference Lee, Moon and Feeley2013). Three reviews did not report prosocial outcomes (e.g., effects of advertising on sales; Assmus et al., Reference Assmus, Farley and Lehmann1984). Quality appraisal and certainty assessment of the included reviews were conducted consistent with our pre-registered protocol. Due to limitations of space, we report the results of these assessments in detail in Supplementary File 1, including a table describing the quality assessment (Table S1) and certainty assessment (Table S2).

Meta-Meta-Analysis of Interventions on Donation Size and Donation Incidence

As shown in Fig. 2, the meta-meta-analytic pooled effect on donation size and donation incidence was small (r = 0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.12], K = 23). The pooled effect was calculated using meta-analyses reported in the included systematic reviews. These effects were heterogeneous between reviews (I 2 2 = 0.85), meaning that the different interventions (e.g., pique, identifying recipient) had very different effects on outcomes (e.g., donation size). The effects were not moderated by the specific outcome (p = 0.12). As seen in Fig. 2, this means pooled effects were similar for donation incidence (r = 0.15, 95% CI [0.05, 0.25], K = 4) and donation size (r = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.11], K = 19). Raw effect sizes extracted from meta-analyses in the included reviews are available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/465ej/).

Interventions to Increase Charitable Donations Organised Using Bekkers and Wiepking’s (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) model

We used a mixed-methods approach to synthesise quantitative effect size estimates with a qualitative analysis of findings according to Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b), with descriptions of each included review. We conducted a further meta-meta-analysis (Fig. 3) with interventions grouped by the mechanism ascribed by Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b). As shown in Fig. 3, the pooled effects of each hypothesised mechanism were significant, however there was large heterogeneity in the effects of each mechanism (all I 2 total > 0.70). Moderation analyses for interventions within each mechanism were all significant (each p < 0.018), suggesting that the specific design, channel, or context in which the intervention was delivered influenced the effective use of the hypothesised mechanism. In the following sections, we describe each identified behaviour change intervention organised by mechanism.

Interventions to Increase Awareness

On average, strategies designed to increase awarenessFootnote 1 had small to moderate effects on donations (r = 0.16, 95% CI [0.09, 0.23], K = 3). In general, charities can increase awareness and therefore donations by piquing donor interest, demonstrating the need, or identifying a victim.

There were Large Effects from the Pique Technique

Piquing interest increased both compliance (r = 0.27, 95% CI [0.19, 0.35], k = 16; Lee & Feeley, Reference MacAskill2017) and donation size (r = 0.29, 95% CI [0.25, 0.33], k = 16; Lee & Feeley, Reference MacAskill2017), leading to much larger total revenue (r = 0.49, 95% CI [0.45, 0.53], k = 16; Lee & Feeley, Reference MacAskill2017). The pique technique involved asking donors for unusual amounts of money (17c instead of 10c), and was designed to break the ‘refusal script’: would-be donors were more likely to stop and ask for a rationale when an odd amount of money was requested of them (Lee & Feeley, Reference MacAskill2017). The largest experiment involved a $3 request so the technique may have questionable ecological validity. It is unclear whether it would also work for requesting $1017 instead of $1000.

Describing a Needy Recipient Increased Donations

This was evaluated in three meta-analyses. Engel found that needy recipients received an increased donation size in dictator games (r = 0.13, 95% CI [0.10, 0.17], k = 69; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011).Footnote 2 Neediness was also a mechanism that explained legitimizing paltry contributions (described below). When someone said “even a penny would help”, many donors saw the recipient as more needy, which had indirect effects on donation compliance (Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017). Finally, compared with causes with modest negative impact (e.g., no school books), when a problem was described as severe, certain, and calamitous (e.g., natural disaster), donation size increased regardless of whether the victim was identifiable or not (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019).

Describing an Identifiable Victim Increased Donation Size

Under most circumstances, donation size increased when donors were presented with a single, ‘identifiable victim’ (r = 0.13, 95% CI [0.08, 0.17], k = 47; Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019) than when presented with statistics or multiple recipients. This is also known as ‘compassion fade’, where a larger number of victims leads to lower perceived impact and lower expected positive affect from donating (Jenni & Loewenstein, Reference Kinnunen and Windmann1997). Mediation analyses supported these hypothesised paths (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019). Empathy had a smaller mediating role: while people showed slightly less empathy for a larger group of people, this lower empathy had only a small effect on donations.

Interventions to Reduce Cost or Increase Benefits

On average, strategies targeting costs and benefits weakly increased donations (r = 0.08, 95% CI [0.02, 0.13], K = 5). The most influential effects appeared to be imbuing a charity with tax deductibility, but nudges or framing strategies had few effects.

Tax Deductibility Increased Donations

One large meta-analysis of 69 studies (n = 1,418,212), examined the impact of tax deductibility on charitable donations (Peloza & Steel, Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2005). Effects were reported as price elasticities which could not be converted to effect sizes. They found substantial elasticity: a tax deduction of $1 resulted in an additional $1.44 being donated to charity (confidence interval not reported). The authors found that tax deductions particularly increased the likelihood of bequests. High-income donors were no more concerned with tax deductions than lower-income donors.

Matching (or Supplementing) Donor Contributions did not Affect Donations

In contrived experiments, when donors were told their funds would be matched (fully or partially), there was a small but non-significant increase in donations (r = 0.08, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.17], k = 18; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011).

‘Door-in-the-Face’ Does not Reliably Increase Donations

Door in the face is designed to reduce the perceived cost of donating by initially presenting a high anchor (e.g., “will you donate $1000?”), then asking for something more achievable (e.g., “how about $10?”; also known as the ‘request then retreat strategy’). Evidence for this strategy appears weak: donors may be marginally more likely to say they will donate (r = 0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.12], k = 7; Feeley et al., Reference Funder and Ozer2012) but this does not translate into actual compliance (r = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.12], k = 15; Feeley et al., Reference Funder and Ozer2012).

Repeated Opportunities/Requirements to Donate Decreased Donations

In contrived experiments with repeated rounds, donors gave less when they were aware there would be multiple opportunities to donate (r = − 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.08, − 0.04], k = 64; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011).

Gain-Framed Messaging did not Affect Donations

Prospect theory proposes that small losses loom larger than small gains, but framing appeals for charitable donations as ‘losses averted’ did not increase the likelihood of donations (r = − 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.10, 0.09], k = 25; Xu & Huang, Reference Xu and Huang2020).

Higher Stakes Inconsistently Decreased Donations

Some studies have asked whether those donating from larger pools of money (usually in contrived experiments) are more generous or more frugal. The larger of the two meta-analyses found no relationship between stake size and donations (r = − 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.09, 0.07], k = 603; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011). But, a follow-up, more focused meta-analysis found that those endowed with more money tended to be less generous, in relative terms, than those endowed with less (r = − 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.03, − 0.12], k = 18; Larney et al., Reference Larney, Rotella and Barclay2019). That is, when people had more, they may donate more in absolute terms, but usually donated a lower percentage of the money they held.

Legitimizing Paltry Contributions has Negligible Total Benefit

Three systematic reviews investigated the effect of ‘legitimizing paltry contributions’ on charitable donations (usually words like “even a penny will help”; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Carpenter, Shaw and Boster2008; Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017; Lee et al., Reference Mazodier, Carrillat, Sherman and Plewa2016). The largest of these reviews found a moderate increase in compliance (r = 0.22, 95% CI [0.17, 0.26], k = 34; Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017) which was offset by a decrease in the size of the average donation (r = − 0.23, 95% CI [− 0.34, − 0.12], k = 11; Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017). The net effect of these competing forces was a non-significant increase in total revenue (r = 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.07], k = 18; Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017). Mediation analyses suggest that the technique increases the perceived neediness of the cause, but that it also vindicates those likely to donate a small amount to avoid judgement (i.e., donors high on ‘impression management’).

Interventions to Increase Efficacy

On average, strategies targeting efficacy increased donations (r = 0.11, 95% CI [0.01, 0.22], K = 3). Direct modelling of the desired behaviour—seeing others donate money—appears to increase donations, but general prosocial media does not.

Prosocial Modelling Moderately Increased Donations, Regardless of Media

When people saw others acting prosocially, they were more likely to imitate, including charitable donations (r = 0.22, 95% CI [0.21, 0.24], k = 40; Jung et al, Reference Lasswell2020). Effects were consistent across media (e.g., direct observation vs watching on TV), age, gender, and culture.

Generic Prosocial Media has Uncertain Effects

Jung and colleagues (Reference Jung, Seo, Han, Henderson and Patall2020) looked at studies where the model performed the same behaviour (i.e., the model donated money and the dependent variable was donation too); they moderated how the model was viewed (real observation vs. via media). Coyne and colleagues (Reference Coyne, Padilla-Walker, Holmgren, Davis, Collier, Memmott-Elison and Hawkins2018) instead looked at media only (TV, movies, video games, music or music videos) with explicitly prosocial content (but not necessarily donating money). Participants in one study were more likely to donate money while listening to “Love generation” (by Bob Sinclair) rather than “Rock this party” (also Bob Sinclair; Greitemeyer, Reference Hennessy, Johnson and Keenan2009). This trend, however, was not reliable with small pooled effects on financial donations and a confidence interval including the null hypothesis (r = 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.04, 0.21], k = 9; Coyne et al., Reference Crocker, Canevello and Brown2018). The media seldom demonstrated the exact behaviour being measured (i.e., ‘Love generation’ does not talk about donations); imitation and efficacy may increase the likelihood of the behaviour being observed but effects do not spill over to nearby prosocial behaviours.

Certainty of Donation Benefit has Little Influence on Donation Compliance

As mentioned previously, correlational studies show that certain calamities appear to attract donations, regardless of interventions like ‘identifiable victims’ (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019). Among dictator games, when uncertainty was added to the benefit (e.g., donating lottery tickets) there was no significant reduction in donations (r = − 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.17, 0.10], k = 7; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011). This may not necessarily translate to different types of uncertainty, however, such as uncertainty that a charity will have an impact.

Interventions to Increase Reputation

On average, strategies targeting reputation slightly increased donations (r = 0.06, 95% CI [0.00, 0.12], K = 6). In general, people are somewhat more likely to donate when there is some reputational benefit to doing so (e.g., being observed or having the donation amount visible).

Being Observed by Others Increases Donations

After synthesising a large number of studies and participants (N > 500,000), Bradley and colleagues found that being observed significantly increased donations (r = 0.15, 95% CI [0.11, 0.20], k = 101; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Lawrence and Ferguson2018). Consistent with reputation hypotheses, effects were larger for repeat interactions, interactions with personal consequences, group social dilemmas (vs. 1:1 bargaining games), and where observation is more intense. In contrast, Engel moderated his findings by whether or not donations were concealed. He found donations decreased when concealing the donor (r = − 0.09, 95% CI [− 0.02, − 0.16], k = 52; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011) or the amount donated (r = − 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.12, 0.00], k = 19; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011), but effects were small.

Artificial Cues of Being Observed Do Not Reliably Increase Donations

Three systematic reviews have explored the effect of artificial surveillance cues on donor generosity (Sparks & Barclay, Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2013; Nettle et al., Reference Nettle, Harper, Kidson, Stone, Penton-Voak and Bateson2013; Northover et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017). Studies have typically analysed the effect of displaying images of ‘watching eyes’ on donation decisions made within economic games, but many include field experiments (e.g., eyes above ‘honesty boxes’). The largest of these reviews found negligible increases in compliance (r = 0.04, 95% CI [0.03, 0.06], k = 27; Northover et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017) and donation size (r = 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.05], k = 26; Northover et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017). Effects seem to only work short-term, with few studies finding any long-term benefits (Sparks & Barclay, Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2013). Overall, artificial surveillance may increase the chance of people donating something in the short term, but the best quality evidence suggests effects are small.

Decision Made by a Group

Making a decision as a group may increase the reputational stakes of signalling altruism but also may diffuse the reputational benefit of donating. Group decisions had no significant total influence on donations (r = − 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.28, 0.18], k = 4; Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011) but the confidence intervals are wide due to the small number of studies.

Interventions to Affect Altruism

Few reviews explored the altruism mechanism proposed by Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b). Two reviews explored the crowding-out hypothesis—that donors motivated by a desire to have an impact would avoid causes already supported by governments because of diminishing marginal returns (Lu, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2016, k = 60; de Wit & Bekkers, Reference Everett, Caviola, Kahane, Savulescu and Faber2017, k = 54). Neither review found decisive evidence for crowding out. A subset of the studies in the reviews had higher internal validity—they either controlled for confounding statistically or via experimental designs. These studies were more likely to suggest that government funding reduces private donations (de Wit & Bekkers, Reference Everett, Caviola, Kahane, Savulescu and Faber2017; Lu, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2016), but given the small, heterogeneous effect sizes, the evidence for a relationship is weak.

Other Influences that have been explored

We did not find reviews of interventions that could be easily classified as ‘solicitation’, ‘psychological benefits’, or ‘values’. We could not easily classify two review findings on the basis of Bekkers and Wiepking’s (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) mechanisms. One review tested a range of interventions designed to promote intuitive thinking (e.g., high cognitive load), but these studies did not influence donations (r = − 0.01, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.01], k = 60; Fromell et al., Reference Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2020). The authors argue that ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ thinking are often aligned on issues of charitable donations. Engel (Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011) found that reducing the number of options available to the donor decreased the amount they donated.

Discussion

Charities conduct activities that seek to address a wide range of social problems (MacAskill, Reference Nagel and Waldmann2015; Singer, Reference Slattery, Vidgen and Finnegan2019). Our meta-review identified interventions (e.g., piquing donor interest, prosocial modelling, increased neediness, identifiable victims, tax-deductibility) that robustly increase charitable donation size or incidence. The effect size of most interventions on charitable donations was relatively small in terms of increasing the success of individual opportunities to donate (|r|< 0.1), but would likely “add up” over time (Funder & Ozer, Reference Funder and Ozer2019). It is important to note that our certainty for this estimate is low, due to limitations in many of the included systematic reviews (e.g., many did not assess the quality of included studies; much neglected publication bias). Most effect sizes were far smaller than the average effect size of interventions published in marketing science (r = 0.24; Eisend, Reference Eisend2015; Eisend & Tarrahi, Reference Eisend and Tarrahi2016) or social psychology (r = 0.21; (Richard et al., Reference Rothschild2003). We identified support for some of the mechanisms described in a widely-used model of charitable donations (increasing awareness, efficacy, benefits, and reputation; Bekkers & Wiepking, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b) and some gaps in the review-level literature (e.g., systematic reviews assessing psychosocial benefits or values). Most reviews included primary studies that assessed interventions in contrived experiments, but some found consistent results in field and laboratory experiments. The findings suggest that several types of interventions can help to increase charitable donations, but the overall poor quality of the evidence suggests that expert judgement and contextual factors will be critical for good decisions in charity promotion.

Practitioners May Draw From a Range of Robust Interventions to Increase Charitable Donations

Taking the findings together, and notwithstanding the limitations of the included reviews, we recommend practitioners consider the following interventions for promoting charitable donations. Examples of the source, recipient, context, channel, and content of each intervention (Lasswell, Reference Lu1948; Slattery et al., Reference Sparks and Barclay2020) are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Help Donors Feel Confident

When interventions increased donor confidence, they tended to solicit higher donations. Effective strategies included seeing other people who donated money (Jung et al., Reference Lasswell2020), not merely seeing people performing ‘prosocial behaviours’ (Coyne et al., Reference Crocker, Canevello and Brown2018). Theory and preliminary findings would suggest that effects are stronger when viewing those who share our group identity (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Louis and Masser2018, Reference Chapman, Masser and Louis2020). Uncertainty about the benefit of a charitable donation may cause prospective donors to reduce their donation size; donation matching campaigns may cause prospective donors to slightly increase their contribution (Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011). Identifiable victims work because donors feel more confident that they could make a meaningful difference (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019). Overall, the key mechanism is that if prospective donors think they can make a meaningful difference, they are more likely to donate (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019).

Provide Donors with Meaningful Rationales for Why Donations are Needed

Donors are persuaded by needy recipients (Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011). Campaigns that say things like ‘even a penny will help’ can increase the likelihood of an initial donation when it signals the ‘desperate need’ of the cause (Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017). Similarly, highlighting a single beneficiary (“identifiable victim”) does not change likelihood of donation behaviour if the charitable cause is obviously severe and widespread (Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019). Piquing a donor’s interest via odd requests (e.g., 17c) appears to work by prompting a conversation around why the donation is needed (Lee & Feeley, Reference MacAskill2017).

Help Donors to Look Good in Front of Others, but Beware Side-Effects

Donations are more likely when donors are observed (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Lawrence and Ferguson2018), and when both they and their donation size are identified to recipients (Engel, Reference Feeley, Anker and Aloe2011). Charities should be careful to avoid using this in a way that creates guilt or social pressure (Bennett, Reference Bennett1998) or in a way that is contrived/artificial (Northover et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017; Sparks & Barclay, Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2013). Instead, charities can use transparency as a way of facilitating pride and self-efficacy (Crocker et al., Reference de Wit and Bekkers2017), to minimise the taboo around discussing charitable donations publicly, and to help establish a social norm toward giving (Singer, Reference Slattery, Vidgen and Finnegan2019).

Seek and Advertise Tax Deductibility

Given the large and significant price elasticity from tax-deductibility (i.e., tax-deductibility increased donations; Peloza & Steel, Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2005), directing effort toward becoming tax deductible will likely pay dividends. While few studies explicitly assessed the impact of advertising deductibility, we assume that doing so may confer some benefits for donations.

Some ‘Nudges’ and Compliance Techniques Work but have Modest Expectations

Nudges usually assume that people will be more likely to donate if charities activate their ‘fast’, intuitive thinking system, but this is not the case (Fromell et al., Reference Ganann, Ciliska and Thomas2020). It appears that intuitive and deliberate thinking around donations are usually aligned. Nudges and framing strategies such as artificial cues (Northover et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff and Moher2017; Sparks & Barclay, Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2013), legitimizing paltry contributions (Bolkan & Rains, Reference Bolkan and Rains2017), ‘door-in-the-face’, (Feeley et al., Reference Funder and Ozer2012) are not consistently effective.

To Aid Evidence-Informed Decision-Making, Reviews and Research Must Improve

Despite being mostly systematic reviews of randomised trials—which are the best causal evidence for effects of interventions (see Fig. 1)—we judged the certainty of all effects to be low. This was because the reviews here, and their included studies, often failed many well-established criteria for internal and external validity (Guyatt et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green2011; Higgins et al., Reference Hulland and Houston2019; Hultcrantz et al., Reference Jung, Seo, Han, Henderson and Patall2017). Many interventions were only tested in laboratories or in experiments with relatively trivial amounts of money (< $10). In contrast, many methods of persuasion commonly used in charitable contexts, such as emotional appeals and rational arguments (Bennett, Reference Bennett2019; Caviola et al., Reference Caviola, Schubert, Teperman, Moss, Greenberg and Faber2020; Stannard-Stockton, Reference Sterne, Savović, Page, Elbers, Blencowe, Boutron, Cates, Cheng, Corbett, Eldridge, Emberson, Hernán, Hopewell, Hróbjartsson, Junqueira, Jüni, Kirkham, Lasserson, Li and Higgins2009), were seldom examined directly by the reviews we found. In addition to reviewing more authentic interventions, review authors could increase the reliability and transparency of their methods via AMSTAR 2 and PRISMA. Registration and standardised reporting checklists like PRISMA (Moher et al., Reference Northover, Pedersen, Cohen and Andrews2010; Page et al., Reference Pham and Septianto2021) improve the internal validity of systematic reviews through common expectations of methodology and reporting.

Results Supported Many Mechanisms Proposed by Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011a, Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b)

Many interventions designed to increase awareness, efficacy, and reputation appeared to usually increase donations, as hypothesised by Bekkers & Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b). We did not find systematic reviews that assessed other hypothesised mechanisms as classified by Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011b), such as solicitation, psychological benefits, and values. However, these findings may not necessarily reflect strengths and weaknesses in the proposed mechanisms but could reflect the way interventions are categorised. As described above, we followed the categorisation of Bekkers and Wiepking (e.g., identifiable victim as ‘awareness’) even if we had reason to think that interventions may be better classified elsewhere (i.e., identifiable victim as ‘efficacy’ or ‘psychological benefits’; Butts et al., Reference Butts, Lunt, Freling and Gabriel2019). Primary studies and non-systematic reviews have found support for some other mechanisms (psychological benefits, Crocker et al., Reference de Wit and Bekkers2017; value alignment, Goenka & van Osselaer, Reference Greitemeyer2019) but for formal model building, researchers should explicitly test whether interventions are operating by the hypothesised mechanism.

Limitations Of Our Meta-Review

By focusing on review-level evidence we necessarily excluded primary studies that would have been useful for charity and non-profit researchers and practitioners. While a review of 1339 included primary studies would have been intractable, reviews of primary studies have sufficient granularity to look at mediators and moderators that might be useful across studies. Instead, we were beholden to the methods of the included reviews. Similarly, we were limited to the interventions selected by previous reviewers, so necessarily omitted interventions not included in any systematic reviews, even though they may inform research and practice (e.g., opt-in vs. opt-out donations; Everett et al., Reference Fromell, Nosenzo and Owens2015). There may, for example, be a wealth of knowledge on interventions using the internet to drive donations, but since there have been few systematic reviews on that topic, those interventions would have been excluded from our meta-review (Bennett, Reference Bennett2016, Reference Bennett2019; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Chen and Lei2014). In a similar vein, focusing on systematic reviews means we may have excluded some more recent, ‘cutting-edge’ interventions. It often takes a number of years for an intervention gaining traction and it being subject to a systematic review. For example, recent research has shown that donors may actually prefer cost-effectiveness indicators (i.e., cost per life saved) to overhead ratios (i.e., percent directed to administrative expenses) but that the latter is usually the focus of decision-making because of the ‘evaluability bias’: people weigh an attribute based on how easy it is to evaluate (Caviola et al., Reference Caviola, Faulmüller, Everett, Savulescu and Kahane2014). However, few studies have examined the effect of publishing cost-effectiveness indicators so it is not yet possible to meta-analyse these interventions. As a result, while the interventions presented in our review have been thoroughly assessed, and many have been shown to be robustly beneficial, there may be other interventions with larger effect sizes not listed here.

Our meta-review prospectively excluded grey literature and reviews in other languages. This may affect generalisability, but doing so seldom affects conclusions from meta-reviews (unlike reviews of primary studies; Ganann et al., Reference Goenka and van Osselaer2010), and we excluded no reviews on the basis of this criteria (see Fig. 1). This is likely because unpublished reviews of charitable donations are less likely to use systematic search and synthesis methods. Nevertheless, there may be other reviews that contribute to this discussion that was missed by our searches and inclusion criteria.

Our review used well-validated assessments of certainty (i.e., GRADE) and review quality (i.e., an abbreviated AMSTAR2 checklist; see Supplementary File 1). These assessments allow interested readers to know the quality of the included reviews and certainty of the included findings. However, in a meta-review, these tools are again beholden to the methods of the included systematic reviews. For example, GRADE reduces the certainty of the findings if there are few randomised experiments, or if the included randomised experiments may have been subject to common experimental biases (e.g., if they were unblinded). These biases reduce the internal validity of the findings, but few included reviews formally assessed these biases. As a result, we could not conduct sophisticated assessments of the internal validity of the included without examining the methods of the 1339 primary studies. We hope future systematic reviews of primary studies more frequently assess these biases using a validated tool, like ROB2 (Sterne et al., 2019). Similarly, GRADE accounts for the external validity of the included studies—such as whether or not findings are likely to generalise to the populations or situations most practitioners are interested in. This can be a complex question requiring judgement. For example, in some cases, Mechanical Turk contractors may be representative samples, but external validity also depends on the design of the study (e.g., viewing a real advertisement vs. playing an economic game). Our ability to assess external validity was subject to the quality of the reporting in the included systematic reviews (unless we wanted to review all 1339 methods). We hope future reviews discuss the external validity of their included studies, and could consider integrating those judgements into their own certainty assessment (e.g., via GRADE). Another approach would be to assess the facilitators and barriers to successfully delivering a pilot-tested intervention to new populations and in new contexts (e.g., scale-up; Saeri et al., Reference Schmidt and Oh2021).

One additional limitation concerns the intervention of tax deductibility (Peloza & Steel, Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2005). This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the impact of tax deductibility on charitable donations primarily in the United States, with a minority of included primary studies describing the effect in similar countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom. Given that formal tax structures and cultural values of taxation and charitable giving differ significantly between countries, and tax policy can vary over time within a given country, the substantial effect size observed in Peloza and Steel’s (Reference Pollock, Campbell, Brunton, Hunt and Estcourt2005) meta-analysis may not hold in other settings.

Conclusion

Increasing charitable donations could benefit society in a multitude of ways: from helping to address global poverty, health, animal suffering, climate change, human rights, and the long-term future of humanity. As a result, identifying robust strategies for promoting charitable causes can have widespread social benefits. Providing good review-level evidence is a key way that charity science can contribute to evidence-informed decision-making in this important area.

In this meta-review, we synthesised multidisciplinary literature on how to promote charitable donations. We identified a range of strategies that may increase donations and some mechanisms that may help explain their effects. These findings suggest that organisations can solicit more money by focusing on individual victims, increasing the publicity of donations, discussing the impact of the donation, and both ensuring and promoting the tax-deductibility of their charity.

Future reviews into other interventions—particularly those conducted outside of contrived experimental settings—would allow researchers and practitioners to assess the ecological validity of those interventions. Readers could have more faith in those reviews if they more consistently followed best-practice approaches to systematic reviews. Our meta-review reveals patterns and gaps within the current research, but it also identifies an array of well-researched mechanisms for promoting charitable donations. Using the findings of these reviews may increase the funds directed to some of the most important and neglected problems facing humanity.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Lucius Caviola and David Reinstein, and several anonymous reviewers for their efforts in maximising the rigor and usefulness of this manuscript

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. No funding was received for conducting this study. No funds, grants, or other support were received.