1 What Is ‘Creative Construction Grammar’?

A sound is just a sound: It is a perception of longitudinal waves striking the eardrum. The sound we utter when we say ‘dog’ is merely a string of sounds, merely a form; it is not a dog, and it does not intrinsically mean dog. The form and the meaning are radically different things. But, mentally, we pair that form with the concept of a dog (/dɑːg/ ⇔ ‘concept of a dog’). Human beings are the symbolic species (Deacon Reference Deacon1997): They are prone to associate forms with meanings (form ⇔ meaning). In fact, Construction Grammar (CxG) (e.g., Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2019; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022a; Ungerer & Hartmann Reference Hartmann and Ungerer2024) argues that form-meaning pairings (known as ‘constructions’) that are stored in the long-term memory are the central units of language. Construction Grammar consequently investigates how we create and invent form-meaning pairs, how we combine them into utterances, and how we unpack those utterances to construct meanings. To know a communicative system is to know a relational network of constructions (Diessel Reference Diessel2019, Reference Diessel2023; Sommerer & Van de Velde Reference Sommerer, Van de Velde, Fried and Nikiforidou2025) and how they combine to create constructs. As a term, ‘construct’ denotes the mental representation of this combination process. The communicator then turns the constructs into a perceivable product that comprises the verbal utterance as well as any multimodal information such as gaze, stance, gestures, and so on. We call this a ‘performance.’ To construct a meaning in response to a communicative performance is to consider how the communicator could have blended the form parts of various form-meaning pairs into that performance. The mental space network built by the construer of those form-meaning pairs enables the construer to attribute a meaning to that communicative performance.

In this Element, we present our approach to Construction Grammar, which we label Creative Construction Grammar. One meaning of Creative Construction Grammar that we want to explore is the study of creative, playful, innovative uses of form-meaning pairs. Everyone notices and remarks upon such obvious creativity. Take, for example, the following instances of the well-known XYZ construction (Turner Reference Turner1987; Turner & Fauconnier Reference Turner and Fauconnier1999):

Amazon Is the Apex Predator of Our Platform Era (the headline of a New York Times article by Cory Doctorow [Reference Doctorow2023])

Shortbread, the little black dress of cookies (the title of a post on the blog bring a little bread [Sarah Grace Reference Grace2012])

We don’t want to be the German car industry of news publishing (Emma Thompson, the new Editor of The Wall Street Journal, joking to the hundreds of staff members listening, as quoted by Katie Robertson [Reference Robertson2023]) (Thompson was commenting on news about how German carmakers were slipping behind Tesla and China in the transition to electronic vehicles.)

It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sundowns sterner, and Gibraltar lights make the village foreign. November always seemed to me the Norway of the year.

XYZ is the Anax of constructions (Eve Sweetser, personal communication, August 29, 2025) (‘Anax’ [ἄναξ] is a word in Ancient Greek that appears in, e.g., The Iliad, to refer to high kings – e.g., Agamemnon and Priam – who exercise lordship over other, lesser, kings.)

We will discuss examples such as these in more detail later. For now, we just want to highlight the fabulous playfulness in these linguistic prompts: They were put together inventively, and they prompt for us to construct remarkable and unusual conceptual blends of Amazon and the lion (1), of a little black dress and a cookie (2), of the German car industry and news publishing (3), of November and Norway (4), of Anax and a clausal construction (5). This type of creative language use has recently received considerable attention in constructionist research (see, e.g., Bergs Reference Bergs2018, Reference Bergs2019; Bergs & Kompa Reference Bergs and Kompa2020; Hartmann & Ungerer Reference Hartmann and Ungerer2024; Herbst Reference Herbst2020; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2018, Reference Hoffmann2019a, Reference Hoffmann2020a, Reference Hoffmann2020b, Reference Hoffmann2022b, Reference Hoffmann2024, Reference Hoffmann2025, fc.; Trousdale Reference Trousdale2018, Reference Trousdale2020; Turner Reference Turner2018, Reference Turner2020; Uhrig Reference Uhrig2018, Reference Uhrig2020).

As Hoffmann (Reference Hoffmann2022b, Reference Hoffmann2024, Reference Hoffmann2025, fc.) points out in his 5C model of constructional creativity, a Creative Construction Grammar that aims to analyze such striking expressions not only needs to take into account the constructional network that underlies these creative constructs. It also must pay attention to the producer (the ‘constructor’) and their audience (the ‘co-constructors’) as well as, and of central relevance to the present Element, the mental process (‘constructional blending’) that produces these ‘creative constructs’ in the working memory.

Our Creative Construction Grammar approach, however, is not limited to just such blatantly creative examples. While constructions are stored in the long-term memory, constructs are form-meaning pairings that are created in the working memory (see Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2017a, Reference Hoffmann2022a, Reference Hoffmann2024, Reference Hoffmann2025). Only in rare cases does a construct involve a single construction (e.g., when reproducing prefabs such as “Thank you!” or “You’re welcome”). Instead, more frequently, speakers will combine several constructions to create a construct. Take the examples in (6) and (7):

Stacey clawed her way to the top.

Both of these draw on the Way construction (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995: 199–218; Israel Reference Israel and Goldberg1996), which, simplifying somewhat, has the form [A VERB possessive_pronouni way PP] and a meaning of ‘A traverses the pathPP while/by doing VERB’ (for more details, see Brunner & Hoffmann Reference Brunner and Hoffmann2020: 5; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022a: 188). In (6), the novice skier is in the A slot, her fills the possessive pronoun slot, and down the ski slope is in the PP slot, leading to an interpretation of ‘the novice skier traversed down the ski slope by walking.’ Similarly, Stacey, her, and to the top combine with the Way construction to yield the meaning ‘Stacey traversed to the top by clawing.’

(7) is arguably more creative than (6) since the former uses a non-motion verb (claw) while the latter has a motion verb (walk) in the Way construction. In both cases, however, we would like to raise the question of what is meant by statements such as ‘the novice skier is in/fills the A slot’ or ‘Stacey combines with the Way construction’: What is the underlying cognitive process that combines constructions in the working memory? As we shall argue, metaphors such as ‘merge,’ ‘combine,’ or ‘unify’ do not constitute cognitively plausible processes. Instead, we will argue that the domain-general process of conceptual blending underlies the combination of more innovative constructs such as (1–5), as well as more “normal” combinations such as (6) and (7).

Finally, we will illustrate that conceptual blending is also required for all associations of forms and meanings in the working memory. This is obvious when looking at the holophrases that children produce during language acquisition. A form such as /foʊn/ (phone) can be used by a child to express a myriad of different meanings (here drawing on data from Tomasello’s own daughter): “First used in response to hearing the telephone ring, then as she ‘talked’ on the phone, then to point at and name the phone, and then when she wanted someone to pick her up so she could talk on the wall-phone (pointing to it)” (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2003: 36). Similarly, bath was used by Tomasello’s daughter “as an accompaniment to preparations for bath, then as she bathed her baby doll” (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2003: 37). In order to correctly understand what their children are trying to communicate with a given form, parents obviously must draw on the constructions they have stored in the long-term memory (such as /foʊn/ ⇔ ‘concept of a telephone’). Yet these constructions only serve as prompts for a complex mental operation that, guided by joint attention (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2003), allows them to guess the particular communicative intention that the child is trying to express. This type of online semiosis is typical of not only parent-child interaction. Even when adults have stored a large number of form-meaning pairs in their mental network, enabling them to produce more complex messages, the meaning pole of entrenched constructions merely provides a starting point for further elaboration. Take the form-meaning pair tiger (/ˈtaɪɡəɻ/ ⇔ ‘concept of a tiger’): As Casasanto and Lupyan (Reference Casasanto, Lupyan, Margolis and Laurence2015: 551), among others, point out, it is impossible to specify a single necessary and sufficient property that is constantly associated with a word construction. In a specific communicative situation, tiger might be used to refer to the actual animal (cf. Well, Siegfried and Roy make that tiger disappear. TV Corpus US/CA 1995 Married with Children) – but, similarly, it can also be used to talk about a toy (cf. Give me three more balls. I’m going for that big stuffed tiger. TV Corpus 2009 US/CA Heroes). Occasionally, it is also used to address humans (cf. Go get them, tiger. TV Corpus 1998 US/CA Full House).Footnote 1 As we will argue, what is therefore also needed in Construction Grammar is a cognitive operation that enables humans to produce and understand the dynamic form-meaning associations that are created on the fly in the working memory for a specific communicative act.

Importantly, however, we do not claim that conceptual blending is the single cognitive operation that renders all other processes obsolete. In line with Usage-based Construction Grammar approaches (cf., e.g., Bybee Reference Bybee2006, Reference Bybee2010, Reference Bybee, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013; Croft Reference Croft2001; Diessel Reference Diessel2019; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019), we maintain that the mental constructicon of speakers is shaped by the repeated exposure to specific utterances (i.e., constructs) and that domain-general cognitive processes such as analogy, categorization, chunking, or cross-modal association play a crucial role in the mental entrenchment of constructions. Entrenchment is a metaphor for the storage of information in the long-term memory (the strengthening of associations and their routinization; Schmid Reference Schmid2020) and we subscribe to Goldberg’s (Reference Goldberg2019) definition, which states that

constructions are understood to be emergent clusters of lossy memory traces that are aligned within our high- (hyper!) dimensional conceptual space on the basis of shared form, function, and contextual dimensions.

Whenever we combine constructions into constructs, however, we must not only activate these associations in the working memory to produce them; in line with recent work in cognitive psychology, we “conceive of working memory as attentional processes operating on long-term memory” (Schweppe & Rummer Reference Schweppe and Rummer2014: 286). As we will show in this Element, humans do not compositionally combine constructions they combine them in a way that is best modeled by conceptual blending. Once a construct is uttered it becomes a token of usage and can consequently become entrenched in the long-term memory. The process of initial combination, however, will involve information activated in the working memory.Footnote 2

Creative Construction Grammar, therefore, aims to account for communicative performances that are considered ‘creative’ as well as ‘normal uses’ of language that do not strike people as particularly creative. As Gibbs has pointed out, routine language draws on “many of the same mental/linguistic routines employed in creative language use” (Reference Gibbs, Arndt-Lappe and Filatkina2025: 43; cf. also Gibbs Reference Gibbs, Winter-Froemel and Thaler2018). Experiments show that even when processing conventional metaphors (such as We have really come a long way since the wedding; Gibbs Reference Gibbs2017), speakers recruit cross-domain mappings (Gibbs Reference Gibbs, Arndt-Lappe and Filatkina2025: 49). The real difference between ‘creative’ and ‘routine’ uses of language lies in the degree to which speakers are consciously aware of a communicative performance: “[S]o-called automatic behavior is really organized by a complex set of cognitive, perceptual, and motor skills, all of which operate again without much conscious awareness” (Gibbs Reference Gibbs, Winter-Froemel and Thaler2018).

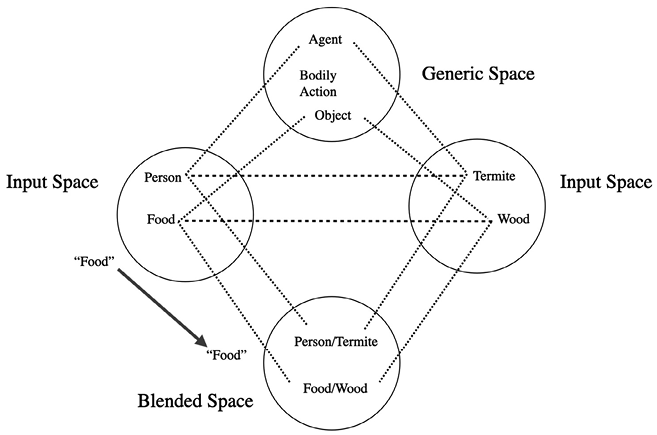

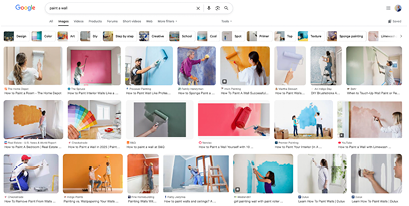

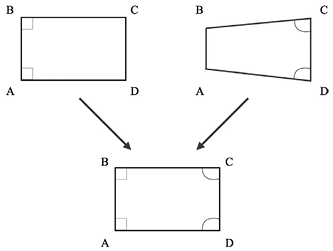

Sometimes these complex processes only become apparent when comparing two seemingly similar, ‘simple’ utterances. Take the statements The man painted the wall black versus The man painted the car black.Footnote 3 Despite the superficial similarity of the two utterances, the events that are mentally conjured up when processing them differ considerably with respect to type of paint and tools, as well as choice of clothes. The results of the respective Google image searches shown in Figure 1 are a case in point.

(a) Top Google image search result for ‘paint a wall’

(b) Top Google image search result for ‘paint a car.’

Search engine results do not, of course, constitute evidence for mental processes. The images in Figure 1 do, however, illustrate crucially different prototypical associations of apparently ‘compositional’ utterances of the type X paints Y.

In this Element, we argue that any discussion of constructions and communicative performances fundamentally depends on a theory of creative combination. A theory of creative combination is the indispensable heart of Construction Grammar. But surprisingly, so far Construction Grammar does not offer such a theory: It has a gaping hole where its heart should be. The central claim of this Element is that the best candidate for a theory of creative construction combination is the theory of Conceptual Integration, also known as ‘Blending’ (Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002).

Blending is a domain-general cognitive process that takes two or more inputs (e.g., semantic frames, words, constructions, gestures, images, ideas, etc.) and combines them into a blend. This process is selective (not every detail from an input space appears in the blend) and frequently gives rise to emergent meanings (which are not part of any of the input spaces). In the history of philology, rhetoric, and linguistics, there were many efforts to account for what looked like pyrotechnic special cases, such as remarkable metaphors, metonymies, analogies, and so on. In this Element, by contrast, we put forward the claim that blending is a domain-general process, and we argue that it is the central, indispensable process for all communication, including even the most basic cases. The present Element cannot provide a self-contained, expert presentation of every detail of blending theory (for this, see book-length treatments such as Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002 or Turner Reference Turner2014). We do, however, present ample evidence for our main claim Section 2 will elaborate on why we think Construction Grammar needs blending as its theory of construction combination, and Section 4 will show how blending theory meets the requirements of constructional combination. In the remainder of this section, we will shortly survey the evidence that blending is a domain-general cognitive process.

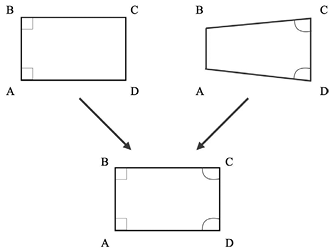

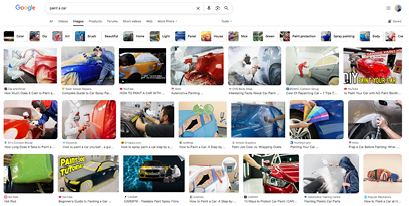

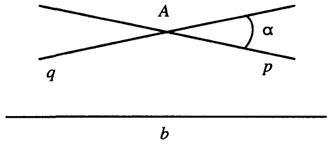

Conceptual blending is not at all specific to language. Quite the contrary. Conceptual blending is a domain-general process whose workings have been extensively examined in art, music, religion, mathematical insight, scientific discovery, advanced social cognition, advanced tool invention, fashion, and so on (Fauconnier & Turner, Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002; Turner Reference Turner2014). The great majority of research on blending lies outside the field of linguistics. Consider the invention of non-Euclidean geometry (Turner Reference Turner and Turner2001), which began from attempts to derive rather than assume the parallel axiom. So many geometers, regarding the parallel axiom as an embarrassment, had tried and failed to prove (rather than assume) the parallel axiom that as early as 1767, Jean le Rond d’Alembert (1717–1783) referred to it as “the scandal of the elements of geometry” (Reference D’Alembert1767: 203–207). Gerolamo Saccheri (1667–1733) made a remarkable attempt that focused on a quadrilateral ABCD where <DAB and <ABC are right angles, and where line segments ![]() and

and ![]() are equal. Without using the parallel axiom, it is easy to prove that <BCD and <CDA must be equal angles. Saccheri did this. If we assume the parallel axiom, <BCD and <CDA can be proven to be right angles. (In fact, the implication works in both directions: The parallel axiom is equivalent to the assumption that <BCD and <CDA are right angles. But all we need for this analysis is the first direction, i.e., that the parallel axiom implies that <BCD and <CDA are right angles.) Therefore, if we deny that <BCD and <CDA are right angles, we thereby deny the parallel axiom. Saccheri did just this in the hope of deriving a contradiction from the denial, which would prove the parallel axiom by reductio ad absurdum. But if <BCD and <CDA are not right angles, they are still equal, and so they must be either obtuse or acute. Saccheri attempted to show that, in either case, a contradiction follows. He assumed that they are acute; that is, he proposed a conceptual blend of two routine Euclidean figures. Both have a quadrilateral ABCD, equal line segments

are equal. Without using the parallel axiom, it is easy to prove that <BCD and <CDA must be equal angles. Saccheri did this. If we assume the parallel axiom, <BCD and <CDA can be proven to be right angles. (In fact, the implication works in both directions: The parallel axiom is equivalent to the assumption that <BCD and <CDA are right angles. But all we need for this analysis is the first direction, i.e., that the parallel axiom implies that <BCD and <CDA are right angles.) Therefore, if we deny that <BCD and <CDA are right angles, we thereby deny the parallel axiom. Saccheri did just this in the hope of deriving a contradiction from the denial, which would prove the parallel axiom by reductio ad absurdum. But if <BCD and <CDA are not right angles, they are still equal, and so they must be either obtuse or acute. Saccheri attempted to show that, in either case, a contradiction follows. He assumed that they are acute; that is, he proposed a conceptual blend of two routine Euclidean figures. Both have a quadrilateral ABCD, equal line segments ![]() and

and ![]() , equal angles <DAB and <ABC, and equal angles <BCD and <CDA. The blend takes this structure from both inputs. But the first input has right internal angles <DAB and <ABC, and the second input has acute internal angles <BCD and <CDA. The blend takes the right angles from the first input and the acute angles from the second (see Figure 2).

, equal angles <DAB and <ABC, and equal angles <BCD and <CDA. The blend takes this structure from both inputs. But the first input has right internal angles <DAB and <ABC, and the second input has acute internal angles <BCD and <CDA. The blend takes the right angles from the first input and the acute angles from the second (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Blending analysis of Saccheri’s quadrilateral

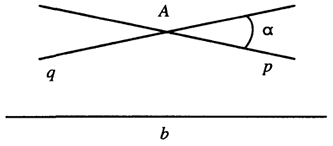

The blend is impossible in Euclidean geometry, but Saccheri never found a contradiction for it. In fact, he produced many astonishing theorems that are now recognized as belonging to hyperbolic geometry. These theorems were so repugnant to commonsense notions that he concluded they must be rejected. It is important to see that all of Saccheri’s elaboration of the blend followed everyday procedures of Euclidean geometry. The input spaces are Euclidean and familiar; the elaboration procedures are Euclidean and familiar. The only new thing in the process is the selective, two-sided projection to create the blend. Another theorem of Saccheri’s relied on a blend having to do with parallel lines: Given any point A and a line b, there exist in the pencil (family) of lines through A two lines p and q that divide the pencil into two parts. The first of these two parts consists of the lines that intersect b, and the second consists of those lines (lying in angle α) that have a common perpendicular with b somewhere along b (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Saccheri’s blend, in which, through a point outside a line, there is an infinity of parallel lines

The lines p and q themselves are asymptotic to b. In Euclidean geometry, angle α is 0 and p and q are identical. But for Saccheri’s new geometry, derived from the acute-angle blend, angle α is positive and p and q are distinct, so that there is an infinity of lines through A that have a common perpendicular with b and never meet it. This is a blend of two standard notions: The first is a schema of a parallel line through a point outside a line; the second is a schema of a bundle of lines through a point. If we blend these, we have multiple lines through a point outside a line that are all parallel to the line.

Blending is often introduced through such highly visible, pyrotechnic examples for the sake of pedagogy. But using flashy examples is profoundly misleading, as nearly all conceptual blending goes completely unnoticed in consciousness. By contrast, the cyclic day provides an example where the blending is still visible, but typically only once it has been pointed out. An actual day is an experience, and we can think of days as events along a timeline. That is already impressive blending: Days do not lie upon a line, nor do we move along a line through them (see Fauconnier & Turner Reference Turner and Favretti2008 for an analysis of the role of blending in conceiving of time). Further blending compresses a sequence of individual days into the cyclic day. The analogies across the inputs are compressed to identity (the cyclic day) and the differences are compressed to change. Now, in the blend, but not in the inputs, there is the amazing emergent structure that the day repeats. This conceptual blend simplifies navigation through daily routines, cultural practices, and societal structures.

Saccheri is not credited with the invention of non-Euclidean geometry. Credit is given instead to Gauss, Bolyai, and Lobatchevsky for recognizing (but not proving) that hyperbolic non-Euclidean geometry is mathematically consistent, and to Gauss for recognizing that physical space might be non-Euclidean. For us, today, non-Euclidean geometry is indispensable to science. We must use it, for example, to compute how to land a craft on Mars. The theory of general relativity is fundamentally built upon non-Euclidean geometry. Non-Euclidean geometry, particularly Riemannian geometry, which generalizes to curved spaces, provides the necessary mathematical tools to describe the motion of planets around stars, the bending of light around massive objects (gravitational lensing), and the behavior of objects near black holes. The operation of conceptual blending in mathematics is pervasive. It is extensively studied in Alexander Reference Alexander2011, Lakoff & Núñez Reference Lakoff and Núñez2000, Núñez in preparation, Steen & Turner Reference Steen, Turner, Martinovic and Danesi2025, and Turner Reference Turner and Danesi2019.

The site at http://blending.stanford.edu cites many hundreds of such studies of conceptual blending in cognitive science, psychology, neuroscience, psychotherapy, mathematics, physics, political science, education, film, pretend play, religion, artificial intelligence, computation, modeling, data science, gesture, music, painting, comics, counterfactual thinking, reasoning, logic, inference, and many other fields outside of linguistics and the study of communication.

There have also been studies on the extent to which the mental operation of blending is available to other species, such as the special panel on ‘Conceptual Blending in Animal Cognition’ at the conference of the Cognitive Science Society held in Vienna on July 26–29, 2021 (https://youtu.be/aPpmCX0Tl7w). We emphasize that our purpose here is to analyze cognitive processes, not to establish definitions (such as a definition of blending). Many operations of integration have been studied in neuroscience (e.g., sensory, perceptual, time-space collocation, object permanence). Efforts to stipulate which of these count as ‘blending’ are merely definitional attempts: provisionally useful for this or that conversation if properly done, but not scientifically fundamental. Blending theory has usually paid attention to cases where the inputs to the blend are in conflict and the blend contains emergent structure, because these are the kinds of integration for which human beings show constant, robust, perhaps unique capacities. These are the kinds of blending for which any linguist who proposes a theory of language must account.

We turn now from blending as a general mental operation to its role in robust human communication. Turner (Reference Turner1996, chapter 8, ‘Language’) argued that cognitive operations whose existence we must grant independent of any analysis of grammar can account for the origin of grammar, and specifically that language is a byproduct of our capacity for advanced conceptual blending. As he put it, “Language follows from these mental capacities as a consequence; it is their complex product.” Beate Hampe & Doris Schönefeld (Reference Hampe, Schönefeld, Müller and Fischer2003) concur: After critiquing other approaches in the theory of Construction Grammar to account for constructions and their combinations into constructs, they write, “let us turn next to the model of ‘conceptual blending,’ developed by Fauconnier & Turner (Reference Turner and Fauconnier1995, Reference Fauconnier, Turner and Goldberg1996, Reference Rubba, Fauconnier and Sweetser1998), which we take to be the most plausible model available.”

The rest of this Element argues that construction formation and construction combination are consequences of conceptual blending, a basic, domain-general mental operation in human beings. Blending theory is the basis of Construction Grammar.

2 Why Construction Grammar Needs a Theory of Creative Combination

All theories of Construction Grammar (CxG) are based on the view that human beings can create and learn form-meaning pairs (constructions) and can combine these form-meaning pairs to create more complicated expressions (Diessel Reference Diessel2019; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2019; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022a; Hoffmann & Trousdale Reference Hoffmann and Trousdale2013; Ungerer & Hartmann Reference Ungerer and Hartmann2023). For example, words are form-meaning pairs, and we can combine words to make sentences. Take the following example (from Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2018: 264):

Firefighters cut the man free

(8) clearly comprises the words firefighters, cut, the, man, and free. But how exactly are these words combined into this expression? A standard assumption in CxG is that so-called argument structure constructions provide a schematic skeleton into which words (and phrases, as will be seen) can be inserted. In (8), cut does not just have its prototypical transitive meaning (of a ‘cutter’ cutting something). Instead, it is understood that the man ends up being free because of the cutting event, and whatever is cut (most likely a vehicle of sorts that the man was trapped in) is not even mentioned in (8) (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995; Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier, Turner and Goldberg1996). The construction that evokes this interpretation is the Resultative construction:

FORM: [SBJ1 V2 OBJ3 OBL4]Resultative Construction5

⇔

MEANING: ‘A1 Causes B3 To Become C4 by V2-ing’

Yet how precisely does the combination of the words and the construction in (9) work? Which cognitive mechanism is supposed to account for the combination of form-meaning pairings? For centuries, linguistic approaches assumed that we combine words according to independent and meaningless syntactic rules. Construction Grammar (Hoffmann & Trousdale Reference Hoffmann and Trousdale2013; Hilpert Reference Hilpert2019; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2022a), however, rejects this assumption.

In CxG, there are essentially two approaches to how the combination of constructions is perceived to work (for further detail on the various approaches see Hoffmann Reference 71Hoffmann and Dancygier2017b, Reference Hoffmann2022a: 258–266; Ungerer & Hartmann Reference Ungerer and Hartmann2023: 22–27). First, there are formalist and computational approaches, such as Berkeley Construction Grammar (Fillmore Reference Fillmore1985, Reference Fillmore1988; Fillmore, Kay & O’Connor Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’Connor1988; Fillmore & Kay Reference Fillmore and Kay1993, Reference Fillmore and Kay1995; Michaelis Reference Michaelis1994; Michaelis & Lambrecht Reference Michaelis and Lambrecht1996; Fillmore Reference Fillmore, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013), Sign-based Construction Grammar (Michaelis Reference Michaelis, Heine and Narrog2010, Reference Michaelis, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013; Boas & Sag Reference Boas and Sag2012), Fluid Construction Grammar (Steels Reference Steels2011, Reference Steels, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013; van Trijp Reference Van Trijp2014), and Embodied Construction Grammar (Bergen & Chang Reference Bergen, Chang, Ostman and Fried2005, Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013). These approaches model construction combination by either ‘unification’ or ‘constraint satisfaction’. Yet while these mechanisms have proved very powerful in modeling language production, hardly any Construction Grammarian would claim that unification or constraint satisfaction are basic, domain-general mental operations.

On the other hand, Cognitive CxG (Croft Reference Croft2001; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019; Boas Reference Boas, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013), due to its cognitive linguistic foundations, follows the axiom that linguists should “strive to account for language in terms of more general cognition before they posit language-dedicated cognitive capacities” (Enfield Reference Enfield and Dancygier2017: 13). As Schmid (Reference Schmid, Geeraerts and Cuyckens2010: 117) observes, “[O]ne of the basic tenets of Cognitive Linguistics is that the human capacity to process language is closely linked with, perhaps even determined by, other fundamental cognitive abilities.” But when it comes to how exactly constructions are supposed to combine, Cognitive CxG has not so far pointed to a specific domain-general process. Its explanations remain vague: “Allowing constructions to combine freely as long as there are no conflicts, allows for the infinitely creative potential of language” (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006: 22).

Goldberg (Reference Goldberg1995: 50; Reference Goldberg2006: 39–40) (see also Boas Reference Boas, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013: 237–238) does, of course, outline some principles that mediate the combination of words and argument structure constructions (namely, the Semantic Coherence Principle or the Correspondence Principle). In current work, these are subsumed under the idea of ‘coverage’ (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019, discussed later) the idea that novel expressions are licensed to “the extent that the existing combination of constructions covers the hyperdimensional space required to include the novel expression” (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019: 73). While previously observed combinations certainly guide how we construct novel utterances, the question remains how these existing constructions were combined in the first place. In addition to the notion of coverage, however, Cognitive CxG has no specified (domain-general) process that is supposed to license the combination of constructions.

Adopting a cognitive linguistic perspective, the overarching question we ask in this Element is how exactly do speakers combine constructions in their minds? Do they simply ‘additively combine’ constructions? Do they ‘merge’ or ‘unify’ them? In other words, is there a domain-specific process that is involved? Most usage-based approaches maintain that CxG, as a cognitive theory of language, has a commitment to look for general cognitive operations to account for language acquisition, variation, and change. Only as a last resort should it hypothesize mental powers that operate only in the domain of language. But is there a domain-general process that could account for construction combination and is there, perhaps, also empirical evidence that such a process is actually at work?

One powerful domain-general process of higher cognition that has been shown to combine mental inputs into novel structures is Conceptual Integration, also known as conceptual blending (Turner & Fauconnier Reference Turner and Fauconnier1999). As mentioned in Section 1, conceptual blending has been used to explain complex human behaviors such as scientific discovery, reasoning, art, music, dance, social cognition, and religion. Blending theory surveys how various species possess rudimentary capacities for conceptual combination and proposes that advanced conceptual blending of the kinds that human beings can perform is perhaps only a slight advance along the cline of the basic blending operations. However, it is this advance that makes all the difference and evolutionarily permits the precipitation of a host of related creative abilities (Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002). While non-human species are astoundingly good at many performances at which human beings are poor, human beings show a remarkable aptitude for creative combination. Speculation about evolution aside (and examining only extant animals), we see at present great differences in creative performance between human beings and other species. Blending theory proposes that a species-wide mental operation (involving advanced forms of blending, with principles and constraints) makes all of these performances possible.

Take the example in (8): As has been mentioned, one might intuitively think that the various word constructions are merely filling in the slots of the Resultative construction (9). But the particular construal evoked by (8) goes beyond the meaning of the argument structure construction and illustrates that things are slightly more complicated: Free can, obviously, also mean ‘free from oppression’, but the selected meaning in (8) is ‘free from being stuck in a crashed car’. Moreover, prototypically, firefighters fight fires using fire hoses, but in (8) we picture them using a saw or a claw to cut the car. Finally, a core frame element of cut namely, the object that is cut (here the car) is backgrounded and not mentioned. All of this happens automatically due to our capacity for flexible, selective projection during blending; we do not even notice that much more than simple constructional combination is required. But even for such standard Construction Grammar examples, we need a more elaborate, flexible, and principled cognitive mechanism to explain the construct than simple ‘combination.’ ‘Combination’ is a word we ascribe to the output performance, but what is required is a theory of what processes might produce that output. The claim that construction combination has taken place does not constitute a theory of the process of creative combination.

In this Element, we argue that conceptual blending is the domain-general process that Construction Grammar so far lacks. Blending is the heart of creative combination, and a theory of creative combination is what CxG needs in order to count as a cognitive theory. In a nutshell, we propose that the way we form, combine, learn, and change constructions is the way we think.

This Element will next review alternative proposals in linguistics for the creative combination of linguistic units inter alia, ‘merge’ (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995, Reference Chomsky2021; Adger Reference Adger2003; Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Kitahara and Seely2022; Chomsky et al. Reference Chomsky, Seely, Berwick, Fong, Huybregts, Kitahara, McInnerney and Sugimoto2023), unification (Shieber Reference Shieber1986), constraint satisfaction (Müller Reference Müller2023: 511–519), juxtaposition and superimposition (Dąbrowska & Lieven Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005), coverage (Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019), and associative links (Diessel Reference Diessel2019; Schmid Reference Schmid2020). While all of these approaches have considerable empirical descriptive power, we will show that for virtually all phenomena across the lexicon-syntax cline, a more creative mental operation is required to fully explain how speakers combine constructions in the working memory – one that accounts for the selectivity of the process as well as for the resulting emergent meaning. As we will argue, conceptual blending is the cognitive mechanism that best accounts for all of these phenomena. Moreover, we will show that Cognitive Grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker and Geeraerts2006, Reference Langacker2008), a theory closely aligned with the goals of Construction Grammar, already assumes that blending is at the heart of composition in grammar.

Thereafter, we will discuss blending as a general mental operation and then illustrate blending in operation over a range of kinds of constructions, from morphological to clausal to discursive. We will explore how multimodal communication, which involves speech, gesture, action, the manipulation of elements in the environment, and other aspects of human communicative performance, crucially requires conceptual blending as an operation for assembling multimodal constructs.

In essence, our proposal is that any cognitive linguistic theory, and Construction Grammar in particular, requires a theory of creative combination that does not postulate a domain-specific combinatory mechanism and we argue that the theory of conceptual blending satisfies that requirement. We label the resulting approach, which takes conceptual blending as the central cognitive process underlying all construction combination, ‘Creative Construction Grammar.’

3 Candidate Theories of Creative Combination

Traditional words-and-rules approaches to language assume that the combination of words into sentences is achieved via syntactic rules. In such frameworks, words are the meaningful units of language, while syntactic rules are purely structural, combinatory operations. The latest and probably most prominent words-and-rules theory is Generative Grammar (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1995, Reference Chomsky2021; Chomsky et al. Reference Chomsky, Seely, Berwick, Fong, Huybregts, Kitahara, McInnerney and Sugimoto2023). In stark contrast to cognitive linguistic theories, Generative Grammar holds that the main components of language are innate, domain-specific principles and parameters. To explain, for example, how words combine, this approach maintains that “the simplest combinatorial operation is binary set-formation, Merge in contemporary terminology” (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2021: 13). Merge is a language-domain-specific operation that takes two words, such as eat and pizza, and combines them into an unordered set {eat, pizza} that still needs to be linearized via a language-specific parameter (yielding the sequence eat pizza in English and Pizza essen in German; for details see Chomsky et al. Reference Chomsky, Seely, Berwick, Fong, Huybregts, Kitahara, McInnerney and Sugimoto2023).

Cognitive Linguistics can be seen as a rebuttal to Generative Grammar, criticizing the latter’s reliance on language-specific and innate knowledge. Instead of postulating language-specific operations, cognitive linguists argue that a “parsimonious account of language would be in terms of cognitive abilities that humans are known to possess for reasons independent of language” (Enfield Reference Enfield and Dancygier2017: 13). In this vein, it would require substantial empirical support for cognitive linguists to postulate a language-specific process such as merge for the combination of words into sentences. Why should humans have ever evolved a language-specific set-forming computational operation that contains no information on linear order? From a Cognitive Linguistic perspective, we should instead look for a domain-general process to account for construction combination. Yet this immediately raises the question: Is there such a domain-general process that accounts for the combination of words?

An intuitive candidate might be ‘combine.’ Humans routinely combine physical objects (e.g., a stone and a wooden rod) into tools (a hammer) or mental concepts (such as ‘breakfast’ and ‘lunch’) into novel ideas (‘brunch’). However, as these examples illustrate, neither of these processes is a case of simple combination. A hammer is not just a stone and a wooden rod, it is a single tool that has a functional use that goes beyond what one could do with the individual parts (i.e., it has an emergent function beyond its parts). Similarly, brunch is not just breakfast and lunch, it is a meal that is, among other things, prototypically scheduled between the latter two. In this Element, we want to take a closer look at the mental process that allows us to combine linguistic signs into larger units. In the cognitive linguistic spirit, our goal is to identify the domain-general cognitive operation that explains the (apparently) simple combination of arm and chair into armchair but also accounts for more creative combinations such as brunch. In the following, we will therefore start by surveying the combinatory mechanisms that have so far been proposed in the cognitive linguistic and constructionist literature, always asking whether these really count as domain-general cognitive processes and whether they provide a cognitively plausible explanation.

3.1 Formal CxG

3.1.1 Unification

Formal Construction Grammar approaches explicitly draw on processes from mathematical and computational sciences to model construction combination: Berkeley Construction Grammar, for example (see, e.g., Fillmore & Kay Reference Fillmore and Kay1993, Reference Fillmore and Kay1995; Fillmore Reference Fillmore, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013) used ‘unification’ (see, e.g., Shieber Reference Shieber1986; Müller Reference Müller2023: 328–331) to combine constructions into constructs.

Unification grammars (Shieber Reference Shieber1986) include formal approaches such as Functional Unification Grammar, Definite-Clause Grammars, Lexical-Function Grammar, Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar, and Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Linguistic knowledge in these approaches is represented in attribute-value matrices (AVMs) such as CAT: N (for an attribute CATEGORY whose value is NOUN). The mathematical foundations of AVMs are so-called Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), with the unification of two DAGs being defined by precise mathematical algorithms of graph theory (see Harary Reference Harary1969). In (only slightly more) informal parlance, unification is a formal, algorithmic process “for solving sets of identity constraints” (Sag, Wasow & Bender Reference Sag, Wasow and Bender2003: 56, footnote 7; for a more technical definition, see Müller Reference Müller2023: 329). For the sake of illustration, take the following, simplified example: the transitive verb love selects for a subject NP and an object NP (SUBCAT <NP, NP>). Upon being combined with an NP such as football, unification would identify the latter as an eligible object of the verb and unify the two into a VP love football that in a next step still requires a subject (SUBCAT <NP, football>). Berkeley Construction Grammar employed a definition of construction unification that led to various computational problems (see Müller Reference Müller2023: 328–331; Sag, Boas, and Kay Reference Sag, Boas, Kay, Boas and Sag2012: 6). But beyond Berkeley Construction Grammar, there are a great number of formal syntactic theories that have successfully implemented unification-based formalisms for the combination of words into phrases and sentences (inter alia, Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar [Gazdar, Klein, Pullum & Sag Reference Gazdar, Klein, Pullum and Sag1985], Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar [Pollard & Sag Reference Pollard and Sag1994], or Lexical Functional Grammar [Bresnan & Kaplan Reference Bresnan, Kaplan and Bresnan1982]). So we are not disputing that unification is a powerful computational process that allows for the successful formal modeling of linguistic competence. But is this how humans actually combine constructions in their minds? If this were in fact the case, then that would mean that Construction Grammar postulates a language-specific mechanism, namely unification, for the combination of constructions, something that Cognitive Linguistics tries to avoid at all costs. As far as we know, no one has ever claimed that unification is a domain-general cognitive process – and even if anyone made this claim, it demonstrably is not how humans combine thoughts (as will be discussed). As we will show, the cognitive linguistic arguments against unification are the same as those that can be levied against constraint satisfaction as the single mechanism of construction combination: These are purely additive operations with no room for selective projection or emergent meaning. Let us turn now to constraint satisfaction to illustrate these shortcomings of formal construction combination mechanisms.

3.1.2 Constraint Satisfaction

Instead of unification, more recent constructionist approaches such as Sign-based Construction Grammar (Boas & Sag Reference Boas and Sag2012; Michaelis Reference Michaelis, Heine and Narrog2010, Reference Michaelis, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013), Fluid Construction Grammar (Steels Reference Steels2011, Reference Steels, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013, van Trijp Reference Van Trijp2014), or Embodied Construction Grammar (Bergen & Chang Reference Bergen, Chang, Ostman and Fried2005, Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013) use constraint satisfaction to model construction combination.Footnote 4 In these ‘constraint-based’ approaches, constructions are seen as constraints and a specific construct such as (8) will simply be checked as to whether it is licensed by appropriate constructions. Van Eecke & Beuls (Reference Van Eecke and Beuls2018: 344–348) impressively illustrate how a sentence like (8) is analyzed in such an approach, showcasing a Fluid Construction Grammar analysis. As they note, the Fluid Construction Grammar parser tries to freely combine all activated constructions, with “[c]onstructions [being] … activated in any order, as soon as the constraints in their conditional part are satisfied” (Reference Van Eecke and Beuls2018: 346). Thus, the definite NP construction matches and licenses the string the man in (8) and the Resultative construction matches and licenses the semantic and syntactic roles of firefighters, the man, and free (and so on). In contrast to generative approaches, which only consider structures to be grammatical if they are fully generated by the grammar, constraint-based approaches are more flexible and allow for partial matching of structures such as fragments as long as no constraints are violated (for a more detailed discussion of generative–enumerative vs. constraint-based approaches see Müller Reference Müller2023: 511–519). Consequently, constraint-based approaches are highly successful at parsing natural language data. Again, however, we would like to ask whether this is an adequate model of the cognitive operations that underlie human language processing: Constraint-based analyses are in essence checking whether the output of construction combination is licensed by the constraints imposed by the existing constructions, but they cannot be said to drive or motivate construction combination. Let us illustrate this point with the following example:

the more opaque that atmosphere isC1

the less conductive it isC2

the bigger the temperature difference you need to cross it.C3

(10) is an instance of the Comparative Correlative construction, a constructional constraint that conventionally comprises two clauses (Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff1999; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2003: 220; Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2017a; for a more detailed analysis of the construction see Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2019b, Reference Hoffmann2022a: 230–231): a first clause (C1: the more opaque that atmosphere is) that is interpreted as the protasis/independent variable for a second clause that is seen as the apodosis/dependent variable (C2: the less conductive it is). Normally, the Comparative Correlative construction thus licenses bi-clausal constructs such as the more opaque that atmosphere isC1, the less conductive it isC2, with a meaning that can roughly be paraphrased as ‘as the atmosphere becomes more opaque C1 → so it becomes less conductive C2.’ In (10), however, the second clause is not only the apodosis to the preceding clause but also the protasis to a second Comparative Correlative construct (the less conductive it isC2, the bigger the temperature difference you need to cross it.C3). Now, complex constructs such as (10) receive a straightforward post-hoc explanation in constraint-based approaches: Both the first pair of sentences (C1 and C2) as well as the second pair (C2 and C3) match the Comparative Correlative construction and can be licensed by it. Note, however, that this analysis is identical to the one that would be given had the speaker simply repeated the second clause, so that he would have uttered two Comparative Correlative constructs in direct succession as in (11):

a. the more opaque that atmosphere isC1

the less conductive it isC2

b. the less conductive it isC1

the bigger the temperature difference you need to cross it.C2

Again, we are not denying that constraint-based analyses are extremely successful at modeling examples such as (11). From a cognitive linguistic perspective, however, there is a crucial difference as to whether a speaker chooses (10) over (11). Instead of analyzing (10) in terms of constraint satisfaction, we argue that a cognitively more adequate account is to describe it in terms of conceptual blending. In (10), we have two instances of the Comparative Correlative construction that are blended into a single construct that, as part of its emergent meaning, expresses the correlative-causal relationship of the three clauses more tightly than (11). So, while constraint-based analyses might be able to assess the degree to which a construct matches the grammar of a language (in usage-based terms, its ‘coverage’ [Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019]; discussed later), blending can explain how and why speakers create (10) and (11), and why they might prefer the former over the latter in certain contexts.

We want to argue that formal operations such as merge, unification, or constraint satisfaction are inadequate metaphors for the cognitive combination of constructions that Cognitive Linguistics and Construction Grammar want to model: First of all, none of these formal approaches are driven by semiotic considerations – algorithms drive these combinatorial processes, not meaningful intent. Consequently, while these operations provide in-depth post-hoc analyses, they do not provide an explanation for how and why speakers combine constructions in a particular way. Secondly, in the linguistic literature, these formal processes are either explicitly (merge) or implicitly (unification and constraint satisfaction) defined as domain-specific procedures. Third, as we will illustrate in more detail in Section 3.2, construction combination is never simply additive. It is selective, and it frequently gives rise to emergent meaning.

Formal, language-specific combination processes are, therefore, inadequate to model the cognitive combination of constructions. But what about usage-based approaches to CxG: Are the processes postulated by these accounts more convincing?

3.2 Usage-Based CxG

3.2.1 Juxtaposition and Superimposition

Within usage-based linguistics, Dąbrowska & Lieven (Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005) directly propose a theory of creative composition of the sort needed in Construction Grammar. They argue that only two basic operations, juxtaposition and superimposition, are required. As they write,

[t]he production of novel expressions involves the combination of symbolic units using two operations: juxtaposition and superimposition … Juxtaposition involves linear composition of two units, one after another. Note that the two units can be combined in either order … In superimposition, one unit (which we call the “filler”) elaborates a schematically specified subpart of another unit (the “frame”).

In line with their usage-based approach, Dąbrowska & Lieven (Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005: 441–444) assume that symbolic thinking (storing pairings of form and meaning, i.e., constructions) is central to humans. Moreover, they maintain that language acquisition is the learning of concrete and schematic constructions, and that constructions are combined via juxtaposition and superimposition. Dąbrowska & Lieven’s analysis is a considerable improvement on (and empirically clearly superior to) postulating abstract and innate syntactic operations. At the same time, there are several issues that we would like to draw attention to. First of all, the way that juxtaposition and superimposition are defined marks them as domain-specific processes. It could, of course, be argued that juxtaposition is merely an additive procedure that can also be found outside of language. Superimposition, however, is specifically defined in a language-specific way (i.e., the phonological as well as semantic integration of a filler into the slot of a schematic construction; Dąbrowska & Lieven Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005: 444). As mentioned earlier, in line with the Cognitive Linguistic enterprise, we argue that such language-specific operations should be avoided at all cost, provided a domain-general process is readily available to explain the data. As we will show, blending is such a domain-general process, and the advantages of our Creative Construction Grammar approach will become particularly obvious when we discuss multimodal communication in Section 4.6 on Blending and Multimodality and Section 5.7 on Multimodal CxG.

What Dąbrowska & Lieven label ‘juxtaposition’ is called ‘composition’ in blending theory (Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002: 48). But in contrast to what blending theory calls ‘composition,’ Dąbrowska & Lieven’s ‘juxtaposition’ is merely an additive procedure that combines two or more constructions without any interpretative component: “[l]inear juxtaposition signals that the meaning of the two expressions are to be integrated, but the construction itself does not spell out how this is to be done, so it must be inferred by the listener” (Dąbrowska & Lieven Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005: 442). Thus, while the domain-specific operation of juxtaposition requires an additional interpretative process, blending offers a domain-general analysis of composition that includes interpretation (as well as selective projection and emergent meaning, something that juxtaposition cannot account for). Similarly, what Dąbrowska & Lieven label ‘superimposition’ is known in blending theory as ‘simplex blending’ (Fauconnier & Turner Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002: 119). Again, in contrast to simplex blending, superimposition is only additive in nature and cannot account for emergent structures or selective projection, particularly in multimodal communication.

Dąbrowska & Lieven (Reference Dąbrowska and Lieven2005) offer a convincing empirical analysis of the phenomena that children exhibit during language acquisition: the learning of constructions and their combination by putting them next to each other (juxtaposition) or combining them (superimposition). As they admit themselves, what is missing from this account is an explanation of how and why children do this. As we will show, conceptual blending not only accounts for these combination operations, but also offers a cognitive explanation for the cognitive semiotic processes that underlie and drive constructional combination.

3.2.2 Coverage

In her latest monograph, Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2019) explicitly addresses the creativity and partial productivity of constructions, focusing particularly on the latter phenomenon. A major innovation of her approach is the notion of coverage – the idea that the acceptability of a new construct is based on its similarity to the existing constructions that a speaker has previously entrenched. Goldberg proposes that instances of each construction cluster together in a hyper-dimensional space and that from this clustering generalizations emerge, which include information on semantics, information structure, syntax, and morphological and phonological constraints. As instances accumulate, new clusters can emerge, and these clusters are emergent constructions. Novel expressions are thus licensed by existing constructions to the extent that the existing combination of constructions covers the hyper-dimensional space required to include the novel expression. The principle of coverage is formalized using standard linear algebra modeling via vectorization:

Clustering algorithms in Bayesian models do this by assigning each new utterance (each usage event) to an existing cluster that maximizes the fit between the new usage and the cluster, while taking into account the prior probability of each cluster.

Barak et al. (Reference Barak, Fazly and Stevenson2014) have proposed such a model in which each usage event is represented by a vector of feature values (Fi), that includes a representation of the verb’s semantics, the utterance’s semantics, and the argument structure’s syntactic properties … The model learns incrementally just as human learners do. It assigns the very first usage event its own cluster; the next usage event is then assigned either to the existing cluster, if it is sufficiently similar to the previous usage event, or to a new cluster (the degree of dissimilarity that is tolerated is set by a parameter).

The principle of coverage recognizes the need for developing and constraining a theory of constructional productivity. It offers a usage-based explanation of how speakers can extend their constructional repertoire, and as such, we think it has greatly furthered our understanding of the degree to which novel constructs are influenced and shaped by the existing constructional network. At the same time, coverage is clearly not intended to be a comprehensive theory of creative combination. The main focus of Goldberg is to account for “the partial productivity of grammatical constructions” (Reference Goldberg2019: 4), to explain “[h]ow native speakers know to avoid certain expressions while nonetheless using language in creative ways” (Reference Goldberg2019: 3). As a result, the main property of coverage is its inherently conservative nature: A novel construct is only licensed to the degree it matches a speaker’s existing constructional knowledge. Constructions from this point of view are emergent clusters of form-meaning associations in a hyper-dimensional conceptual space. New expressions are then heard and are consequently associated with existing clusters. This, however, raises the question of how those new expressions, those new constructs, were formed in the first place, before hearers learned them in response to performances by others.

As a case in point take Perek’s impressive (Reference Perek2016) study on the VERB the hell out of NP-construction (e.g., Dudek said he’d once beaten the hell out of a Pepsi machine that took his money. COCAFootnote 5 2001 FIC SouthernRev). Perek found that the construction comprises several semantic subclusters which form the construction’s coverage, such as psychverbs (e.g., fascinate, please, or like) or physical actions causing harm (e.g., beat, knock, or slap; Reference Perek2016: 172–174). In line with the coverage hypothesis, he was able to further show that the productivity of these different clusters depended on their density, that is, the number of existing uses (Perek Reference Perek2016: 174–179; see also Goldberg Reference Goldberg2019: 67). Yet how did these clusters emerge in the first place? Any appeal to coverage, in essence, runs into the issue of regressus ad infinitum: When the construction was first coined, by definition, no cluster existed. Previous studies (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Napoli2008) had postulated that the source construction was one found in the context of religious writings describing exorcism (a priest beating the devil out of someone), in which the devil was still interpreted as an affected object. Later, the devil was supposed to have been “‘bleached’ to the extent that it became solely an intensifier” (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Napoli2008: 371). However, Hoeksema & Napoli (Reference Hoeksema and Napoli2008: 373) already mentioned a second potential source construction (e.g., Mrs. Whaling would scare the life out of her with her tales of fearful adventure in the Indian country; COHA 1884 FIC QueerStoriesBoys), in which the postverbal NP the living daylights/lights only had an adverbial meaning (i.e., it expressed that an event was particularly scary). Hoffmann & Trousdale (Reference 72Hoffmann and Trousdale2022) then found that in the critical period of the nineteenth century, other potential input constructions existed that had a postverbal NP without referential meaning, merely expressing intensification (She can knock the spots out of these boys at that game. 1887, source Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. spot, meaning she soundly beat these boys or They took the starch out of that Twelfth Maine, sir; COHA 1867 FIC MissRavenelsConversion, meaning they soundly beat the Twelfth Maine). In addition to this, the NP the devil had been used as a non-referential expression of a speaker’s heightened emotion since the eighteenth century (What the Devil do you do without your Shoes!; 1739, Old Bailey CorpusFootnote 6 17390502_25). Hoffmann & Trousdale (Reference 72Hoffmann and Trousdale2022) argued that several different routes might have led to the present-day construction VERB the NTaboo out of construction (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2021): Some speakers might have drawn on the exorcism construction together with the eighteenth-century non-referential the devil construction. Others might have used the idiomatic starch and/or spots constructions together with the exorcism construction. Alternatively, many other combinations are possible (e.g., blending the scare the life out of construction and the eighteenth-century non-referential the devil construction as well as many other combinations). Hoffmann & Trousdale (Reference 72Hoffmann and Trousdale2022) use this construction to show that multiple input constructions can allow different speakers to converge on the same novel construction. Whatever route speakers and hearers might have taken, all of these combinations require selective projection (of, e.g., the devil as a marker of heightened speaker emotion, postverbal NPs such as the spots/the starch as non-referential markers of intensification, the exorcism construction for the formal the hell out of sequence, etc.) to get an emergent new blended construction (FORM: [[NPi Vj [the NTABOO out of]k NPl] ↔ MEANING: [SEMi excessivelyk PREDj SEMl]]; adapted from Hoffmann & Trousdale Reference 72Hoffmann and Trousdale2022: 368).

What in a coverage approach accounts for the speaker’s ability to make new constructs? What accounts for the original creation of the constructions in the history of language usage? What accounts for the original creation of constructions in the history of the species? What Goldberg proposes seems to be a system of inferring a construction, or a change in a construction, from encounters with its usage. This is a system for recognizing constructions that are in use or perhaps attributing grammaticality to utterances. It is a new proposal for a type of language acquisition process, which learns constructions from utterances that are built out of those very constructions, and as such, it is an important mental process in Construction Grammar. But it is neither a full theory of how those utterances come into being in the first place, nor is it a theory of how the speaker can combine constructions to create the construct that the learner ingests as new data (whether for the purposes of learning or for reinforcing a construction). Accordingly, we do not see how ‘coverage’ provides a complete theory of creative combination.

Creative language use, of course, always draws on the constructional networks available to speakers (being one of the five Cs in Hoffmann’s [Reference Hoffmann2024, Reference Hoffmann2025, fc.] 5C model of constructional creativity). However, limiting novel uses to more or less creative extensions of existing constructions fails to account for the selective nature of constructional combination as well as the novel emergent meanings that go beyond what the input constructions seem to offer. Creative (and, as we will argue, non-creative) language use requires an advanced blending operation of constructions in the working memory that is much more flexible and dynamic.

3.2.3 Combination in Dynamic Network Approaches: Association, Sequential Relations, and Co-semiosis

One cognitive linguistic model that explicitly focuses on the emergent and dynamic nature of language is Schmid’s (Reference Schmid2020; see also Reference Schmid, Geeraerts and Cuyckens2010) Entrenchment-and-Conventionalization (EC-) Model. The EC-Model is a usage-based model of language as a dynamic complex-adaptive system, continuously evolving through interactions between usage, conventionalization, and entrenchment: Language changes diachronically in virtue of feedback loops created by interactions; language accordingly responds fluidly to new communicative needs and contexts. The EC-Model emphasizes emergentist association: linguistic conventions and knowledge emerge from the repeated use of language in various contexts; associations between forms and meanings, as well as between different forms themselves, become stronger with repeated use, leading to the conventionalization and entrenchment of linguistic elements. ‘Entrenchment’ refers to the strengthening of cognitive representations of linguistic elements through repeated use, making these elements more easily and quickly activated in the mind. ‘Conventionalization’ involves the establishment and maintenance of linguistic norms within a speech community. Entrenchment and conventionalization are presented as interdependent and mutually reinforcing, driving the continual adaptation and evolution of language. The EC-Model also highlights the importance of interpersonal effort in the conventionalization process. Interpersonal activities, such as co-semiosis (mutual understanding during communication), co-adaptation, and co-construction, are crucial for the establishment of linguistic conventions. They require active participation and cooperation between speakers, and this cooperation undergirds the conventionalization of linguistic forms and structures.

There is much in the elaborate EC-Model to applaud, and we feel no need to oppose anything in the brief description of the EC-Model presented here. Crucially, though, the processes proposed in the EC-Model are not cognitive processes and are certainly not domain-general processes: Instead, entrenchment and conventionalization are outcomes of processes. Our contribution is to propose, and defend, the hypothesis that blending is the domain-general cognitive process that leads to outcomes such as entrenchment and conventionalization. Furthermore, entrenchment and conventionalization as discussed in the EC-Model do not address the central operations of creativity, selective projection, and emergent structure in both mental spaces and mental space networks, or any of the other aspects of meaning construction analyzed in conceptual integration theory. We agree wholeheartedly that interpersonal effort is crucial to language dynamics but ask what makes that interpersonal effort possible? What makes it possible to have an elaborate conception of other minds and their role in interactive discourse, including our conceptions of what they are trying to do, and our conceptions of their conceptions of what we are trying to do, and our conceptions of their conceptions of our conceptions of what they are trying to do, and so on? These layers of conceptions, of other minds, of their viewpoints and their intentions, of their complicated labor in communicative interaction, including their conceptions of us, and their conceptions of our conceptions of them, and so on, are indispensable to co-semiosis. Blending is the cognitive engine of such conceptions. Constructors and co-constructors interact in co-semiosis. Their conceptions of their minds and their efforts, indeed of their interactive minds and their interactive efforts, are products of blending. It may be that a dynamic network model such as the EC-Model simply assumes that the domain-general cognitive operation of blending, with all its complicated processes, is available to the speakers and that such a model presents itself as exploring the consequences of blending. If so, then we offer no fundamental opposition or critique.

A similar highly valuable line of research on cognitive, usage-based varieties of Construction Grammar has been pursued by Holger Diessel (e.g., Diessel Reference Diessel2019, Reference Diessel2023). Diessel’s analysis revolves around the idea that constructions are organized within a network called the constructicon. He proposes a multidimensional network approach influenced by usage-based linguistics. By emphasizing the observable network of constructions and their associations, Diessel’s model, in our view, implicitly relies on the intricate processes of blending without explicitly incorporating them into his model. (Though conceptual blending is at least briefly mentioned as “a general mechanism of language use and cognition” Diessel Reference Diessel2019: 101, 107) The model’s strength lies in mapping the relationships and associations between constructions, but it does not fully explore the domain-general cognitive mechanisms that generate these relationships in the first place, and similarly does not address creativity, selective projection, or emergent structure in both mental spaces and mental space networks, or any of the other aspects of meaning construction analyzed in conceptual integration theory. It similarly takes for granted the cognitive operations that make possible conceptions of other minds and their work in co-construction during interaction and collaboration.

Fauconnier & Turner (Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002, and citations therein) argued that to fully explain human language one must point to the cognitive abilities possessed by human beings but not available to other mammalian and especially primate species. In their account, rudimentary forms of blending have been available from at least the stage of early mammals, depending on which kinds of integration phenomena one prefers to count as blending. They observe that ‘blending’ is merely a label and that what matters scientifically is not a label but analyses of the workings of relevant processes. Where one draws the line in integration phenomena for ascribing the label ‘blending’ is merely a matter of preference. They emphasized the performances in which other species surpass humans: Human beings cannot fly, photosynthesize, smell as well as a dog, or see as well as an eagle. The genome of the Norwegian spruce tree is seven times as large as the human genome. Fauconnier & Turner (Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002) proposed that human capacities lie on a cline of blending: while we may share this cline with many other species, human evolution produced a slight advance in blending abilities. They analyzed how, in reality, a small difference in causes can produce a very large difference in effects. Various species are impressively communicative (not only with each other, but also with human beings) yet there is a sharp difference between the communicative abilities of non-human species and those that are species-wide for human beings, and this difference is crucial for a comprehensive theory of human Construction Grammar. The original Fauconnier-Turner line of argument about the cognitive basis of human communicative performance has been pursued in other publications (e.g., Turner Reference Turner2014). A usage-based theory of the origin and development of full human language that rests on only cognitive abilities shared with other species is missing its central and indispensable component. Luckily, we propose that the needed component already exists and can be directly embraced: Conceptual Blending.

3.2.4 Composition and Integration

Within cognitive and functional approaches to language, there are many analyses of processes of language that look much like blending. The most prominent and thorough of these theories is Cognitive Grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker and Geeraerts2006). Langacker writes, for example, that “[o]ne constructional schema can be incorporated as a component of another” (Langacker Reference Langacker and Geeraerts2006: 46). These many analyses include considerations of coercion when two units combine (Taylor Reference Taylor2002: 287), partial sanctioning of a unit, and extension and innovation during the combination of units (Langacker Reference Langacker2008: 215–255). A close attention to the varieties of symbolic combination was present in Cognitive Grammar from its earliest days. For example, in his landmark 1986 introduction to the field in Cognitive Science, Langacker wrote,

“When a head combines with a modifier, for example, it is the profile of the head that prevails at the composite-structure level.” (Reference Langacker1986: 13)

“Each sense of ring depicted in Figure 1, for example, combines with the phonological unit [ring] to constitute a symbolic unit.” (Reference Langacker1986: 18)

“An auxiliary verb, either have or be, combines with the atemporal predication and contributes the requisite sequential scanning.” (Reference Langacker1986: 27)

“A modifier is a conceptually dependent predication that combines with a head, whereas a complement is a conceptually autonomous predication that combines with a head.” (Reference Langacker1986: 34)

“It should be apparent, however, that the same composite structure will result if the constituents combine in the opposite order, with Alice elaborating the schematic trajector of likes, and then liver the schematic landmark of Alice likes. This alternative constituency is available for exploitation, with no effect on grammatical relations, whenever special factors motivate departure from the default-case arrangement.” (Reference Langacker1986: 35)

It may be that Langacker and other cognitive and functional linguists would agree (no doubt with some amount of clarification or objection, and only to a certain extent) that such analyses presuppose general cognitive mechanisms not specific to language and that indeed the chief one they presuppose is blending. In response to this suggestion, Langacker wrote (personal communication, cited in Turner Reference Turner2020):

I fully agree that CG [Cognitive Grammar] “analyses presuppose general cognitive mechanisms not specific to language and that indeed the chief one they presuppose is blending.” I have long taken it for granted that conceptual and grammatical structures can be characterized in terms of mappings between mental spaces, and in particular, that ‘composition’ amounts to (bipolar) blending. This conforms to my traditional description that component structures are ‘integrated’ to form the composite whole. Perhaps because it is so evident, I have not made the connection to conceptual integration theory as explicit as I perhaps should have done. Here is one succinct statement: “In composition, component structures undergo conceptual integration to form a composite structure that is more than just the sum of its parts” (Langacker Reference 73Langacker2017, 118). Slightly more elaborate indications of the affinity are found in (Langacker Reference Langacker, Panther, Thornburg and Barcelona2009: 47) and (Langacker Reference Langacker, Dąbrowska and Divjak2015: 135–136).

In this Element, we now want to make explicit the role of conceptual blending as the sole source of linguistic combination that has implicitly been presupposed in previous cognitive linguistic approaches, as acknowledged for Cognitive Grammar by Langacker. We want to emphasize again that we support attempts to create mathematical and computational models of the kinds of combination we see in the development of language (phylogenetically and ontogenetically), language change, the formation of constructions, and the formation of constructs out of constructions. But we propose that theories like ‘merge’ do not provide a theory of creative combination (and are not cognitive); that theories like ‘coverage’ are still far from a theory of creative combination (and are not yet cognitive, although they might develop in that direction); and that the most prominent and influential theory of language in the fields of cognitive and functional linguistics, namely Langacker’s Cognitive Grammar, already assume blending as the central process of combination.

In the rest of this Element, we will briefly lay out principles of the mental operation of blending and analyze blending in action in language and communication.

4 Blending

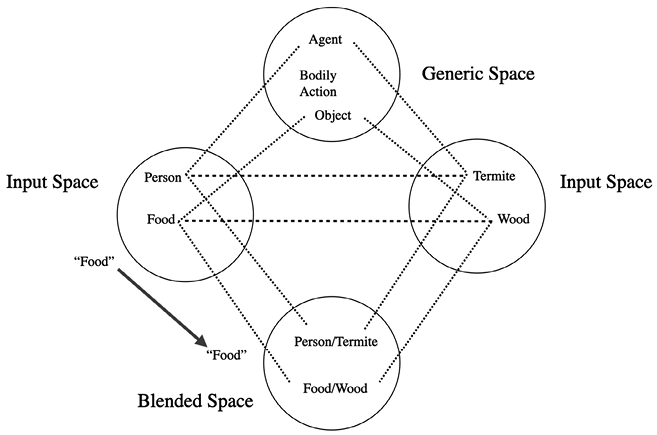

Conceptual blending occurs when various input ideas, meanings, and conceptual structures, often starkly in conflict, are selectively combined into a conceptual structure not identical to any of the inputs, often with an emergent structure of its own.