Organizations are social systems that can contain localized norms, values, expectations, rules, and customs about right and wrong (Solinger, Jansen, & Cornelissen, Reference Solinger, Jansen and Cornelissen2020). Studying the qualities that differentiate organizations along these lines is needed to understand why some of them facilitate widespread misconduct (Ashforth & Anand, Reference Ashforth and Anand2003) while others enable more pro-social ends (e.g., compassion; Dutton, Worline, Frost, & Lilius, Reference Dutton, Worline, Frost and Lilius2006). A growing body of research has been devoted to ethical cultureFootnote 1 to address this question. A variety of models of ethical culture have been proposed, and great progress has been made in understanding ethical culture in organizations (see Roy, Newman, Round, & Bhattacharya, Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024 for a review). However, once a body of research has matured, there is usually a need for a period of critique in which existing limitations are explicitly identified and addressed (Gottfredson, Wright, & Heaphy, Reference Gottfredson, Wright and Heaphy2020). The literature on ethical culture has reached this point as several limitations seem to inhibit further progress.

Ethical culture appears to lack conceptual clarity. Multiple sources of ambiguity seem present, with both parent concepts, “ethics” and “culture” evading precise definitions by social scientists (see Jones, Reference Jones1991; Martin, Reference Martin2001; Patterson, Reference Patterson2014; Tenbrunsel & Smith‐Crowe, Reference Tenbrunsel and Smith‐Crowe2008; Warren & Smith-Crowe, Reference Warren and Smith-Crowe2008 for discussions). Different models of ethical culture have been proposed to further develop and clarify this concept. These models feature different ideas about what ethical culture is, while also having some overlap. They also appear to have different conceptual weakness. Taken together, the cumulative depiction of ethical culture is both complicated by the multitude of models and vague in terms of conceptual definitions. Conceptual issues of this sort are known to create downstream problems with empirical research and, subsequently, also limit the quality of practical recommendations that can be made (Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023; Lambert & Newman, Reference Lambert and Newman2023; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2003).

Ethical culture is theorized to be about shared meaning systems held by members of organizations or subunits (Huang & Paterson, Reference Huang and Paterson2017; Huhtala, Tolvanen, Mauno, & Feldt, Reference Huhtala, Tolvanen, Mauno and Feldt2015; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Hannah, Avolio, Kozlowski, Lord, Treviño, Dimotakis and Peng2012; Treviño, Reference Treviño1990). This suggests that ethical culture is best conceptualized as a collective and multilevel collective concept—that is, a group-level concept based on patterns among lower levels (Morgeson & Hofmann, Reference Morgeson and Hofmann1999). Theory development for collective and multilevel concepts call for additional steps to make accurate levels-based inferences (Chen, Mathieu, & Bliese, Reference Chen, Mathieu, Bliese, Yammarino and Dansereau2005; Klein, Dansereau, & Hall, Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994; Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). However, multilevel issues with ethical culture need more attention (Mayer, Reference Mayer, Schneider and Barbera2014; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024).

These points suggest critique and reform are needed when it comes to studying ethical culture. When an area of research is suspected to lack conceptual clarity, it is necessary to diagnose the issues and embark on conceptual revision (Welch et al., Reference Welch, Rumyantseva and Hewerdine2016). Because theory informs empirical work, this stage must be addressed first before related methodological and measurement issues can be tackled (Lambert & Newman, Reference Lambert and Newman2023; Singh, Reference Singh1991). Generally, this process involves identifying conceptual limitations, weighing solutions to limitations against methodological considerations, and developing a revised conceptualization with these limitations in mind (Makowski, Reference Makowski2021). Such efforts can and should build upon past knowledge by organizing conceptually sound aspects of prior models into a revised compound construct (i.e., concept mixology; Newman, Harrison, Carpenter, & Rariden, Reference Newman, Harrison, Carpenter and Rariden2016). To accomplish these goals, we use best practices for conceptual revision to systematically analyze, evaluate, and reorganize the cumulative conceptual domain of ethical culture (155 definitions) using the method proposed by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016).

Because ethical culture is theorized as a collective, multilevel concept, a critical examination of existing research also calls for investigation into levels of analysis. Thus, we capture the state of the science regarding levels of analysis using recommended techniques (e.g., Gooty, Serban, Thomas, Gavin, & Yammarino, Reference Gooty, Serban, Thomas, Gavin and Yammarino2012; Yammarino, Dionne, Chun, & Dansereau, Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005). This step in the development of a research area is necessary to have a clear picture of the extent to which the literature addresses levels in methodologically and theoretically rigorous ways, and it helps with identifying areas to improve.

The result of these efforts revealed disorganization of the conceptual domain, confusion between the conceptual domain and the nomological network, and imprecise treatment of levels of analysis. We propose a revised definition and multilevel model by integrating the anthropological concept of ethical affordances (Keane, Reference Keane2016) with the model of cultural dynamics (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). The cultural dynamics model helps with disorganization by providing a theoretically justified approach for organizing the conceptual domain and for integrating conceptually clear elements of prior work into the revised model. The cultural dynamics model also depicts how elements of ethical culture might interrelate (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Focusing on ethical affordances differentiates ethical culture from related concepts in a conceptually sound way. We expand our theorizing to depict how ethical culture manifests at theoretically significant levels by exploring bottom-up emergence (processes by which lower levels combine to form higher-level properties; Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000) and top-down influences (processes by which higher levels influence lower levels). The revised model of ethical culture provides a stronger basis for studying more theoretically precise linkages with closely related concepts in the nomological network as well as for studying ethical culture as a multilevel concept.

1. PREVIOUS CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF ETHICAL CULTURE

Beginning in the late 1980s, behavioral business ethicists began to grapple with the question of how moral aspects of culture vary in organizations (Kish-Gephart, Harrison, & Treviño, Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010; Treviño, den Nieuwenboer, & Kish-Gephart, Reference Treviño, den Nieuwenboer and Kish-Gephart2014), and three dominant models of ethical culture have formed as a result (Mayer, Reference Mayer, Schneider and Barbera2014). One of the first to address this question was Treviño (Reference Treviño1986, Reference Treviño1990), who posited that ethical culture is a subset of an organization’s culture that reflects the interplay of ethics-related organizational systems that could be formal or informal. This model of ethical culture focused largely on the “phenomenal” parts of culture—that is, “more conscious, overt, and observable manifestations of culture such as structures, systems, and organizational practices”—because they could be measured in a more straightforward way (Treviño, Butterfield, & McCabe, Reference Treviño, Butterfield and McCabe1998: 451). Formal systems are officially endorsed by the organization and include leadership, authority structures, policies, reward systems, orientation and training programs, and decision-making processes. Informal systems are unofficially communicated and shared. They include norms, heroes, role models, rituals, stories, and language.

Around the same time, Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989) proposed another view of ethical culture, which they referred to as “corporate ethical values.” Hunt, Wood, and Chonko (Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989) adopted the view, supported by some culture scholars of the time (e.g., Rokeach, Reference Rokeach1973), that values are the most important dimension of an organization’s culture, and they advocated for a special focus on “the ethical dimensions of corporate values” for understanding ethical culture (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989: 79). Cultural values are espoused standards and ideals (Schein, Reference Schein1990, Reference Schein2017). Drawing from Deal and Kennedy (Reference Deal and Kennedy1982), Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989) noted that values create a sense of identity, promote stability of a social system, direct decision-making, and call for commitment to a larger purpose. Corporate ethical values were defined as a “composite of the individual ethical values of managers and both the formal and informal policies on ethics of the organization” (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989: 79). They indicate what courses of action are right and worth doing. Although Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989) emphasized ethical values in their work, their model also included policies on ethics, overlapping somewhat with other components of culture such as those proposed by Treviño (Reference Treviño1990).

In a later effort to refine ethical culture, Kaptein (Reference Kaptein1999, Reference Kaptein2008) proposed the corporate ethical virtues model of ethical culture. The model was based on Solomon’s (Reference Solomon1999) conceptualization of virtues, which are enacted values and pervasive traits that enable success in society. According to Kaptein, an organization is virtuous when it operates in a way that fosters employees’ ethical behavior. Organizational virtues include making normative expectations known and providing employees with material and emotional support to complete their tasks in a morally appropriate way. In virtuous organizations, managerial behavior is consistent with normative expectations, and employees are aware of the consequences of their actions. Problems can be discussed openly, and unethical behavior can be reprimanded.

Since the initial work on ethical culture, a large body of research on the topic has since been produced (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024), and additional perspectives have been proposed (see Table 1 for a summary). Ethical culture is now accepted as an important component of behavioral business ethics (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010; Peng & Kim, Reference Peng and Kim2020). It represents a multifaceted system of environmental variables intended to answer the question of why good people behave badly in certain organizational environments. Unlike other predictors of unethical behavior, such as maladaptive character traits of bad actors, the cultural environment highlights work experiences that can be changed and managed. Taken together, these points suggest that an ethical culture is a potentially powerful intervention for preventing damaging forms of misconduct.

Table 1: Definitions of Ethical Culture with Select Associated Items

2. TAKING STOCK OF CHALLENGES AND CHARTING A WAY FORWARD

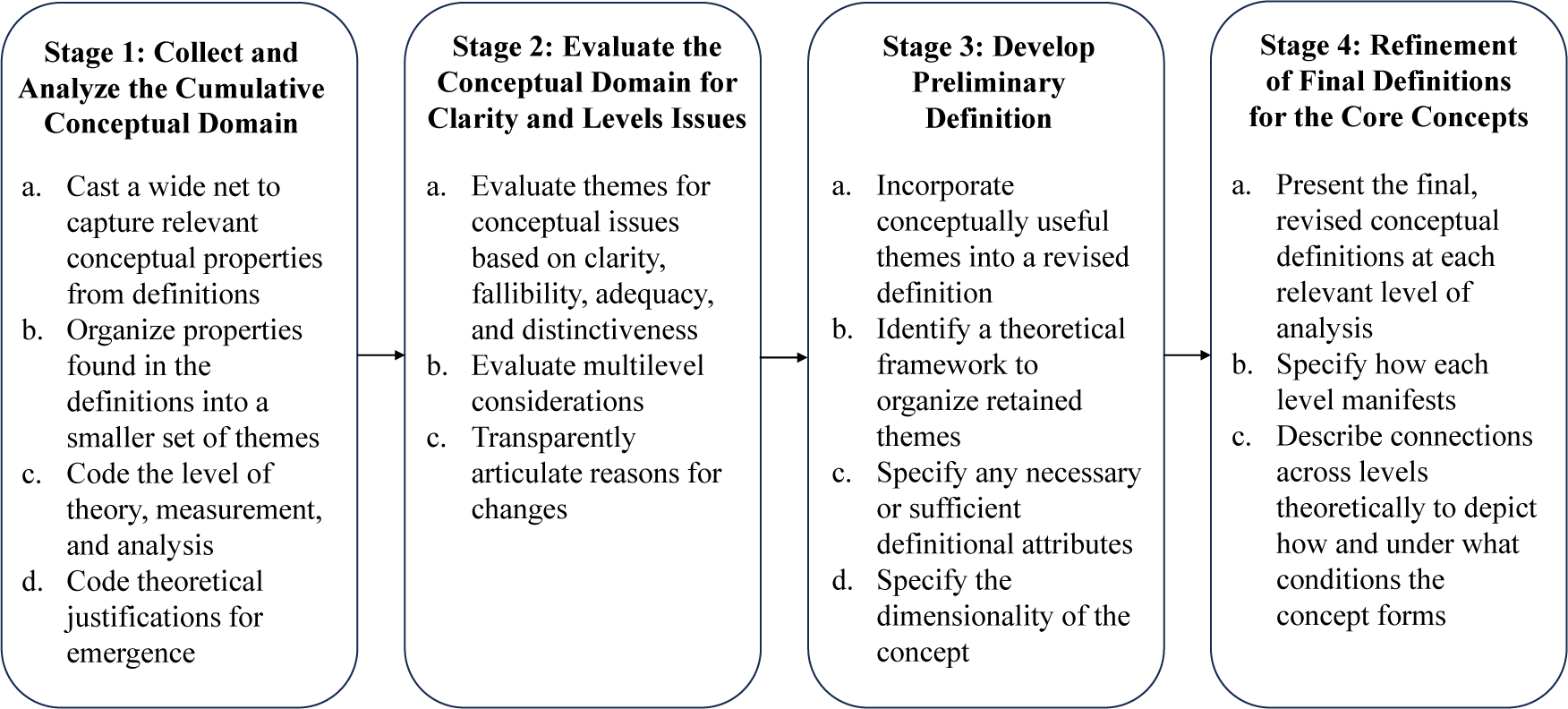

Once a concept has been repeatedly affirmed as important, there is often a need to explicitly identify and revise extant limitations associated with it to make further progress (Gottfredson et al., Reference Gottfredson, Wright and Heaphy2020; Ross, Toth, Heggestad, & Banks, Reference Ross, Toth, Heggestad and Banks2025; Welch, Rumyantseva, & Hewerdine, Reference Welch, Rumyantseva and Hewerdine2016). Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016) outlined a step-by-step process to accomplish this. Conceptual revision is to be performed systematically by 1) collecting and analyzing a representative set of definitions from the literature to identify themes, 2) evaluating definitional themes for clarity and scientific utility, 3) organizing definitional themes that are unafflicted by conceptual problems into a revised theoretical model, and 4) presenting the final, revised conceptual definition after several rounds of revision (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). Incorporating useful elements of prior definitions into an overarching model, that is, conceptual “mixology,” enhances predictive validity and allows for the revised concept to build upon the accomplishments of prior research while also addressing issues (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Harrison, Carpenter and Rariden2016).

Because ethical culture is a collective, multilevel concept, we added several steps to this process to assess how ethical culture is addressed with respect to levels of analysis, following recommendations from Yammarino et al. (Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005) and Klein et al. (Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994). Multilevel concerns are often treated as a statistical challenge and have been overlooked during concept development. However, there should be a “primacy of theory” because statistical treatment of a concept depends on how it is theorized (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994). This requires specification of the level(s) at which a concept resides (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994; Miller, Reference Miller1978; Rousseau, Reference Rousseau1985) and providing definitions of the concept at each of these levels (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mathieu, Bliese, Yammarino and Dansereau2005). Connections across levels need to be described theoretically to indicate how and under what conditions the concept manifests at a given level (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). It is important to assess whether the level at which a concept is defined (i.e., level of theory) aligns with how it is studied and treated empirically (i.e., level of analysis/measurement, Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994) as failure to have alignment undermines the quality of levels-based inferences that can be made (Yammarino et al., Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005).

These major stages of conceptual revision serve as the structure for the remainder of this work (see Figure 1). Throughout, we adopt a pragmatist-interactionist approach, which rejects the goal of creating “correct” scientific concepts that offer the “truth” (Blumer, Reference Blumer1940; Welch et al., Reference Welch, Rumyantseva and Hewerdine2016). Instead, concepts should be developed and evaluated based on scientific or practical utility. This includes clarity (defined using concise language), fallibility (creates falsifiable hypotheses), adequacy (appropriately references and structures theoretical linkages), and distinctiveness (differentiated from related concepts; Makowski, Reference Makowski2021).

Figure 1: Multilevel Conceptual Revision Process

2.1. Stage 1: Collecting Representative Definitions and Analyzing the Literature

Stage 1 involves taking stock of the cumulative conceptual domain (i.e., the constitutive definitions of a concept; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Harrison, Carpenter and Rariden2016).Footnote 2 It is important to “cast a wide net” to capture a sufficient representation of definitions (Stage 1a in Figure 1; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). We searched for peer-reviewed academic articles containing the words “ethical culture” in the abstract in Business Source Complete, Psych Info, and Web of Science. We cross-referenced recent meta-analyses (Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010; Peng & Kim, Reference Peng and Kim2020) and literature reviews on ethical culture (Mayer, Reference Mayer, Schneider and Barbera2014; Treviño et al., Reference Treviño, den Nieuwenboer and Kish-Gephart2014; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024) to identify any missing articles. Articles were included if they contained text defining or describing ethical culture or if ethical culture was studied as a focal concept (i.e., variable). Definitional text was identified by examining the introduction of the article, the theoretical development sections, or sections of the articles that contained “ethical culture” in the heading. We also searched for text containing terms such as “defined,” “refers,” “characterized,” or “describes.”

Given that one of our aims was to analyze the conceptual domain of ethical culture, we included theoretical articles or commentaries, in addition to empirical articles, if a definition of ethical culture was included. The search process revealed 155 viable articles. The date of publication for articles that were included spanned from one of the earliest works on the concept (Treviño, Reference Treviño1986) through the end of data collection (2024).

Definitional text was coded to find themes in the core conceptual properties (Stage 1b in Figure 1; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). Definitions consist of constituent attributes (Blumer, Reference Blumer1954), which were the unit of analysis during coding. Attributes are the key features or properties of a concept. When considered jointly, they ascribe meaning to the concept and should differentiate it from others. According to Podsakoff et al. (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016), who cited Goertz (Reference Goertz2006), “The core attributes of a concept constitute a theory of the ontology of the phenomenon under consideration” (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016: 161). Attributes of concepts are intended to answer the question of “what” (Gerring, Reference Gerring2012). What features define something? What do we mean when we refer to a certain scientific entity? Thus, we searched for unique attributes contained within definitions. Coding was conducted by the first author in NVivo12. Initially, every potential attribute was recorded as it was explicitly stated in the text, revealing fifty distinct attributes. For example, the definition provided by Key (Reference Key1999: 219) of “Ethical culture represents shared norms and beliefs about ethics” would be coded as having core attributes of being about 1) shared 2) norms and 3) beliefs. Open coding was then used to organize the initial attributes by abstracting the coded text at a level above the actual data (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss1990). Several higher-order themes emerged by grouping similar attributes together. Twenty-two themes of attributes remained (see the Open Science Framework repository for a full list of attributes).

Additional pieces of information were coded to assess ethical culture as a multilevel concept (Stage 1c in Figure 1; Yammarino et al., Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005). The level or levels at which ethical culture was theorized to manifest, that is, the level of theory, was coded for each article. The level of theory indicates “the focal level to which generalizations apply” (Mathieu & Chen, Reference Mathieu and Chen2011: 613). The level of theory was identified by examining theoretical arguments, the conceptual definition, the literature review, or the hypotheses formulation sections of the article (Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Serban, Thomas, Gavin and Yammarino2012; Yammarino et al., Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005). Each level was recorded if multiple levels were claimed.

For eligible empirical articles (ninety-seven articles), we coded the level at which the data were measured and analyzed to help determine if there was alignment between the theoretical level of interest and the level to which inferences can be made based on analysis.Footnote 3 The level of measurement is the level of “the actual source of data” (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994: 198). The level of analysis is the level at which the concept is treated during statistical procedures (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994). The level of analysis was the same as the level of measurement unless individual-level responses were aggregated to represent higher levels. If aggregation procedures were used, the level of statistical analysis was coded to reflect the level to which data were aggregated. The level of analysis should match the level of theory in multilevel research (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994; Gooty et al., Reference Gooty, Serban, Thomas, Gavin and Yammarino2012; Yammarino et al., Reference Yammarino, Dionne, Chun and Dansereau2005).

When authors aggregated lower-level data to higher levels, we recorded if the authors specified how lower levels emerged (Stage 1d in Figure 1; Klein & Kozlowski, Reference Klein and Kozlowski2000). We noted whether emergent properties were indicated by referring to one of the composition models proposed by Chan (Reference Chan1998). A composition model provides “a systematic framework for mapping the transformation across levels” and is needed to establish the meaning of the higher-order concept when it is derived from lower levels (Chan, Reference Chan1998: 234). Composition models indicate potential criteria, such as within-group agreement, used to provide evidence that the higher level emerged from lower-level data and to indicate which mathematical transformation (e.g., group mean) should represent the higher level. We also coded multilevel statistical procedures used to provide evidence that lower levels transferred to higher levels (e.g., rwg; James, Demaree, & Wolf, Reference James, Demaree and Wolf1984).

2.2. Stage 2: Evaluate the Conceptual Domain for Clarity and Levels Issues

Analysis revealed eight limitations in the conceptual themes (Stage 2a in Figure 1) and treatment of levels (Stage 2b in Figure 1). These limitations reflect disorganization of the conceptual domain, confusion between the conceptual domain and nomological network, and imprecise treatment of levels of analysis. A summary of these limitations and their solutions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2: A Summary of Existing Conceptual Limitations and Proposed Solutions

2.2.1. Disorganization of the Conceptual Domain

Definitions of ethical culture, in the aggregate, reveal conceptual disorganization (Limitation 1). Disorganization of the conceptual domain occurs when definitional attributes are lumped together in a confusing or inconsistent way and/or without a clear conceptual reason why they belong together as part of the same concept (Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023; Gardner, Karam, Alvesson, & Einola, Reference Gardner, Karam, Alvesson and Einola2021; Locke, Reference Locke2012; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2003). Many attributes are considered part of ethical culture, yet there is no theoretical core that depicts why these attributes belong together (see Table 1). Along these lines, ethical culture is often defined as involving an interplay, interaction, or alignment (46 percent) among its constitutive attributes, yet there have been limited efforts to portray the nature of this interplay or how alignment occurs. The problem extends into measurement as the items used to measure ethical culture also touch on a wide range of phenomena, are disorganized, and are sometimes inconsistent with the definition (see the select items in Table 1). For example, the model developed by Hunt et al. (Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989) implies a focus on ethical values (i.e., “the corporate ethical values model”). Yet, the items largely focus on behavior of leaders, an issue we address in greater detail below. Other models also show inconsistency between the items and definitions.

Between the definitions and measures, it is hard to comprehend what is being studied. This limitation reflects an adequacy problem (appropriately references and structures theoretical linkages; Makowski, Reference Makowski2021). Scientific concepts should have a theoretical core that binds and organizes their properties (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). Using a theoretical framework to structure and define the concept can help indicate what attributes are grouped together and on what basis, thus decreasing disorganization.

2.2.2. Confusion Between the Conceptual Domain and Nomological Network

Analysis revealed confusion between different concepts in the nomological network and the conceptual domain. Strong definitions must distinguish a concept from related ones. Thus, there should be a defensible way of distinguishing ethical culture from its broader parent concept, organizational culture. There have been two primary ways of accomplishing this. The corporate ethical virtues model draws on the idea of organizational virtues. However, this definition is “invalid” because it anthropomorphizes organizations and therefore describes something that cannot exist (Limitation 2; Locke, Reference Locke2012). Virtues involve innately human characteristics such as intellectual awareness of what one is doing and morally appropriate motivation (Audi, Reference Audi2012). Although anthropomorphizing organizations is common in the management literature, it is conceptually problematic (Andersen, Reference Andersen2008). Scientific conceptual definitions must articulate the unique nature of classes of phenomena in a way that enables their empirical study. Using organizational virtues does not meet the mark because it does not refer to anything that actually exists. Organizations cannot be intellectually aware, nor can they have motivations.

Ethical culture has also been distinguished from organizational culture more broadly by suggesting it represents the elements of culture that result in ethical behavior (41 percent of definitions; Limitation 3). Some version of this limitation is in multiple definitions in Table 1. This is problematic because ethical behavior is a common dependent variable of ethical culture (e.g., Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010). Defining a concept based on its own outcomes means that the specific properties of the concept tend not to be articulated and hypotheses cannot be falsified on theoretical and empirical levels (Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart, & Shamir, Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2003). Theoretically, if a study sought to establish a relationship between ethical culture and ethical behavior and did not find one, by definition, what was thought to be ethical culture would not be because it is theorized as that which produces ethical behavior.

Empirically, the idea of ethical behavior is deeply embedded in several items used to measure ethical culture (see Table 1; “ethical behavior is the norm,” “my coworkers commonly engage in unethical behavior,” “my coworkers in this organization are highly ethical”). Having measures that blend predictors and outcomes creates causal indeterminacy (Fischer, Hambrick, Sajons, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Fischer, Hambrick, Sajons and Van Quaquebeke2020; Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023). The outcome variable is “smuggled” into the independent variable; the input and output are combined (see Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2020a: 6 for a detailed discussion of this problem). This raises questions about the value of what can be concluded from findings (Antonakis, Reference Antonakis2017). Embedding ethical behavior in items of ethical culture leads to interpretations of findings that amount to “organizational cultures where ethical behavior is the norm have more ethical behavior” or “organizational cultures where coworkers commonly engage in unethical behavior have less ethical behavior.” Such findings are tautological, and due to the conflation of predictor and outcome, hypotheses are essentially unfalsifiable on an empirical level as well.

Similarly, leadership is also included in definitions of ethical culture (21 percent of definitions). Yet leadership is also an antecedent of ethical culture (e.g., Peng & Kim, Reference Peng and Kim2020; Limitation 4). At a minimum, leadership should either be an antecedent or part of ethical culture, but it should not be both, as there is little need to use the same concept to partially predict itself. Leadership and culture have important distinctions that mean they should be viewed as distinct. Culture refers to shared perceptions of meaning held by a group or a social system (Key, Reference Key1999; Martin, Reference Martin2001). Leadership is about “what people do in order to influence others” (Fischer, Hambrick, Sajons, & Van Quaquebeke, Reference Fischer, Hambrick, Sajons and Van Quaquebeke2023: 1). Leaders are ultimately individual people, and leadership is about the patterns of influence behaviors a person takes (Banks, Reference Banks2023; Banks, Woznyj, & Mansfield, Reference Banks, Woznyj and Mansfield2023; Fischer, Dietz, & Antonakis, Reference Fischer, Dietz and Antonakis2024; Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Karam, Noghani, Cogliser, Gullifor, Mhatre, Ge, Bi, Yan and Dahunsi2024). Consider the following definitions of ethical leadership, which place leadership as behaviors enacted by individuals (italics added to highlight):

The demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making (Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005: 120).

Signaling behavior by the leader (individual) targeted at stakeholders (e.g., an individual follower, group of followers, or clients) comprising the enactment of prosocial values combined with expression of moral emotions (Banks, Fischer, Gooty, & Stock, Reference Banks, Fischer, Gooty and Stock2021: 6).

Thus, culture and leadership are qualitatively distinct concepts. Leadership is a behavioral concept that is ascribed to individuals, and culture is a meaning-based concept that applies to groups.

Including leadership as part of ethical culture introduces conceptual conflation, which refers to when distinct types of concepts (e.g., perceptual, behavioral, trait) are erroneously merged as part of one concept (Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Toth, Heggestad and Banks2025). Conflation masks important theoretical and functional differences between concept types such as how they operate or how they form. It also makes it challenging to study relationships between concepts. Including leadership as part of ethical culture also presents a major problem for investigating trickle-down models about the influence between ethical leadership on ethical culture (see Peng & Kim, Reference Peng and Kim2020 for a meta-analytic review). The items in Table 1 illustrate that each measure of ethical culture contains items about leadership, suggesting that the observed relationship between these constructs is artificially inflated (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024). In fact, some items of ethical culture are almost indistinguishable from items used to measure ethical leadership (e.g., “My supervisor sets a good example in terms of ethical behavior,” “My leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics,” Brown et al., Reference Brown, Treviño and Harrison2005; DeBode, Armenakis, Feild, & Walker, Reference DeBode, Armenakis, Feild and Walker2013).

Removing leadership from definitions of ethical culture does not mean that leadership is unimportant in understanding ethical culture. Leaders can form culture through what they pay attention to, how they allocate resources, and what behaviors they model (Berson, Oreg, & Dvir, Reference Berson, Oreg and Dvir2008; Schein, Reference Schein2017; Spinosa, Hancocks, Tsoukas, & Glennon, Reference Spinosa, Hancocks, Tsoukas and Glennon2023). The selection and evaluation of leaders depend on (i.e., is influenced by) culture, and definitions of good leadership are culturally situated (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson, Bryman, Collinson, Grint, Jackson and Uhl-Bien2020b). These arguments point to a bidirectional relationship between culture and leadership, not that leaders (i.e., people and their influence behaviors) are culture (i.e., shared systems of meaning). Separating leadership from ethical culture should better equip researchers to study the relationship between the two.

There is also ambiguous distinction between ethical climate and ethical culture (Limitation 5). The prevailing consensus is that organizational climate and culture are distinct concepts due to their different foci (Ehrhart, Schneider, & Macey, Reference Ehrhart, Schneider and Macey2013; James et al., Reference James, Choi, Ko, McNeil, Minton, Wright and Kim2008; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024; Schneider, Ehrhart, & Macey, Reference Schneider, Ehrhart and Macey2013) and empirical distinctiveness (Trevino et al., Reference Treviño, Butterfield and McCabe1998). Compared to climate, culture is generally regarded as a broader and more inclusive concept, having components that members tend to be more aware of (artifacts) and components that tend to be subconscious (assumptions). Organizational climate is often depicted as shared perceptions regarding the policies, practices, and procedures about something (Kuenzi & Schminke, Reference Kuenzi and Schminke2009: 637; Schneider & Barbera, Reference Schneider and Barbera2014), while organizational culture is about shared perceptions of artifacts, values, assumptions, and symbols (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993; Schein, Reference Schein1990).

The meanings of ethical culture and ethical climate have evolved in ways that are somewhat at odds with these more generally accepted understandings of organizational climate and culture. Ethical climate was originally viewed as a system of institutionalized and shared ethical norms and principles (“…normative patterns in the organization,” Victor & Cullen, Reference Victor and Cullen1988: 103; “the shared perception of what is correct behavior and how ethical situations should be handled in an organization,” Victor & Cullen, Reference Victor, Cullen and Frederick1987: 51), which is not consistent with the accepted definitions of organizational climate (Kuenzi, Mayer, & Greenbaum, Reference Kuenzi, Mayer and Greenbaum2020: 47). Similarly, many definitions of ethical culture in Table 1 do not appear to tap as much into the more subtle or meaning rich cultural forces that operate below conscious awareness, such as assumptions or symbolic meanings. Ethical culture and ethical climate have struggled to gain legitimacy outside of business ethics circles (Mayer, Reference Mayer, Schneider and Barbera2014). The incongruent meanings with more general understandings of these concepts could be one reason why.

To align with the broader understandings of organizational climate, ethical climate has been redefined as shared perceptions of ethical policies, practices, and procedures (Kuenzi et al., Reference Kuenzi, Mayer and Greenbaum2020). Having revised ethical climate to be in more alignment with broader understandings of climate, two questions remain: 1) what should be done with the shared ethical norms in Victor and Cullen’s (Reference Victor and Cullen1988) models of ethical climate and 2) how can ethical culture be distinguished from Kuenzi et al.’s (Reference Kuenzi, Mayer and Greenbaum2020) revised model of ethical climate? Regarding the first question, it seems hasty to cease work on the shared ethical norms/principles that stem from Victor and Cullen’s (Reference Victor and Cullen1988) widely studied model. Instead, the norm-based view of ethical climate is more appropriately reorganized into a theory of ethical culture. Ethical norms are included as a part of ethical culture (30 percent of definitions), and moral principles are considered a part of cultural values (i.e., “espoused goals, ideals, norms, standards, moral principles, and other untestable premises” Schein, Reference Schein1990: 9). Even Victor and Cullen (Reference Victor and Cullen1988) recognized that their ethical climate model is part of culture (103).

Regarding the second question, we believe ethical culture can be further distinguished from ethical climate by aligning more closely with broader understandings of culture. Many definitions and items used to study ethical culture in Table 1 are not connected to deeper, less overt meaning structures that are commonly associated with culture such as shared assumptions, beliefs, symbols. Engaging more with theory on organizational culture should help resolve the misalignment by highlighting the different foci of this area of research.

This set of limitations relates to clarity (clear communication of conceptual meanings), adequacy (appropriately references and structures theoretical linkages), fallibility (able to produce falsifiable hypotheses), and distinctiveness (differentiation from other concepts; Makowski, Reference Makowski2021). The confusion between the conceptual domain and the nomological network can be partially resolved by having a clearer theoretical foundation that describes culture in the context of ethical culture. The absence of a clear depiction of culture caused closely related, but distinct, concepts to be engulfed in the conceptual domain. It also caused concepts that should be considered part of ethical culture to be viewed as distinct.

Confusion between the conceptual domain and nomological network can also be resolved by having a necessary and sufficient attribute or attribute set that is uniquely applied to ethical culture (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). Necessary attributes must be present for something to be considered an example of the concept, and sufficient attributes constitute the concept’s unique nature. This attribute/attribute set must be defined in a way that does not rely on the outcomes or antecedents of ethical culture and should be a characteristic that applies to culture.

2.2.3. Imprecise Treatment of Levels of Analysis

Finally, analysis of the literature revealed several limitations regarding levels of analysis. Almost all articles (97 percent) stated that the organizational level was at least one relevant level of theory. The subunit level (6 percent) was also occasionally claimed as a relevant level of theory. Some articles explicitly stated the focal level of theory was at the individual level (10 percent). When developing multilevel concepts, the nature of the concept at each specific level should be explicitly articulated (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mathieu, Bliese, Yammarino and Dansereau2005). Clear articulation of the concept across levels in turn guides attention to the appropriate theoretical level and subsequently the right level of analysis.

There needs to be a cohesive multilevel model of ethical culture that accomplishes this goal (Limitation 6). Such a model will help address conceptual confusion that has expanded across levels. This conceptual confusion can be seen with the small number of studies conducted on the subunit level. This is surprising given that the subunit level is considered one of the primary levels at which shared culture manifests due to the large and complex nature of many modern organizations (Ostroff, Kinicki, & Muhammad, Reference Ostroff, Kinicki, Muhammad, Weiner, Schmitt and Highhouse2012; Schein, Reference Schein2017). Additionally, the number of articles stating the individual is a relevant theoretical level is quite high, given that culture only theoretically applies to higher-level systems of meaning (e.g., at the subunit or organizational level; James et al., Reference James, Choi, Ko, McNeil, Minton, Wright and Kim2008: 21). Individuals have perceptions of ethical culture, and organizational/subunit ethical culture is often composed of aggregations of these perceptions (Chan, Reference Chan, Schneider and Barbera2014). The focal level of theory should always be at a group level, not the individual level, as individuals do not possess a culture.

In addition to definitions across levels, theory for multilevel concepts should conceptually depict how a concept manifests at a particular level by portraying top-down and bottom-up processes involved (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). Top-down influences are about the processes whereby higher levels influence lower levels. Depictions of top-down processes were underdeveloped (Limitation 7). The broader organizational culture literature portrays ways in which external environmental factors, such as national context, exert top-down influences on organizational-level culture (Erez & Gati, Reference Erez and Gati2004; Ehrhart et al., Reference Ehrhart, Schneider and Macey2013). Existing research on ethical culture has featured little discussion of how similar external top-down factors from beyond the organizational level may influence organizational-level ethical culture.

Additionally, the main motivation of ethical culture research is to understand how organizational ethical culture operates as a top-down influence on individuals (e.g., Kish-Gephart et al., Reference Kish-Gephart, Harrison and Treviño2010; Mayer, Reference Mayer, Schneider and Barbera2014). Although most articles have theoretically claimed to examine this top-down influence, most were unable to do so empirically. Eighty-seven percent of the quantitative articles claiming the organizational level as the level of theory fully relied on unaggregated, individual-level perceptions of ethical culture. Thus, the level of theory (organizational) is, by and large, misaligned with the level of analysis (individual; Klein et al., Reference Klein, Dansereau and Hall1994). Such misalignment has been dubbed the folly of “theorizing ‘A’ but testing ‘B’” (Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, & Yammarino, Reference Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou and Yammarino2001: 515), where A is organizational-level ethical culture and B is unaggregated individual-level perceptions of ethical culture. Effect sizes from analyses conducted solely at the individual level cannot be used to estimate effect sizes for organizational-level phenomena (interested readers should see Bliese & Halverson, Reference Bliese and Halverson1996; Diez-Roux, Reference Diez-Roux1998; Robinson, Reference Robinson1950). This raises significant questions about organizational ethical culture as findings from unaggregated individual-level perceptions of culture cannot be used to make inferences about theoretical claims related to culture at the organizational level (Chan, Reference Chan, Schneider and Barbera2014: 484).

Ethical culture is theorized to form when individual-level understandings of culture become shared (35 percent of definitions), suggesting the presence of bottom-up emergence. Bottom-up emergence occurs when individual characteristics create patterns that result in the manifestation of a higher-level group property (Kozlowski, Chao, Grand, Braun, & Kuljanin, Reference Kozlowski, Chao, Grand, Braun and Kuljanin2013; Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). There needs to be both conceptual justification and empirical evidence indicating that emergence took place (Kozlowski & Klein, Reference Kozlowski, Klein, Klein and Kozlowski2000). The conceptual depiction of bottom-up emergence is the basis for how the higher level should be treated empirically. Morgeson and Hofmann (Reference Morgeson and Hofmann1999) recommended theoretically describing relevant interactions among lower levels that portray how the higher-level manifests and whether emergence is conditional.

Descriptions of when bottom-up emergence causes ethical culture to manifest at different levels need more attention (Limitation 8). Bottom-up emergence must be described either as compositional or compilational (Bliese, Reference Bliese, Klein and Kozlowski2000). Social learning theory is one of the most common theories used to explain how perceptions of ethical culture become shared (e.g., Huhtala et al., Reference Huhtala, Tolvanen, Mauno and Feldt2015; Kangas, Muotka, Huhtala, Mäkikangas, & Feldt, Reference Kangas, Muotka, Huhtala, Mäkikangas and Feldt2017; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Hannah, Avolio, Kozlowski, Lord, Treviño, Dimotakis and Peng2012). Typically, the theory is used to suggest that employees model leaders, and this modeling causes a shared belief system to develop (i.e., emerge). This means compositional emergence is involved (i.e., lower-level cognitions, attitudes, affect, or behaviors become shared by individuals). One of several composition models must be selected to articulate the nature of transferences across levels and to establish the empirical criteria that indicate whether emergence took place. Almost no articles explicitly described the compositional model used (Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Hannah, Avolio, Kozlowski, Lord, Treviño, Dimotakis and Peng2012 is one exception). Perhaps due to the lack of discussion about the composition model used, justificatory evidence that emergence took place was varied, unsystematic, and lacking sufficient detail.Footnote 4

The imprecise treatment of levels of analysis presents adequacy problems as the theoretical linkages across levels need more consideration. In part, these limitations need to be resolved with more multilevel empirical research. However, a multilevel model is needed to set the foundation for empirical research to progress. There needs to be a definition for each level and a depiction of the processes that shape how ethical culture manifests at each level. The lack of an explicitly multilevel model of ethical culture appears to have made it easier to change the level of interest throughout the research process (i.e., one level is stated during theoretical development, yet another is tested) and caused important levels of theory to be neglected (subunit). Finally, there needs to be a clear discussion of which type of composition model best describes ethical culture using Chan’s (Reference Chan1998) typology.

These eight limitations taken together indicate several areas for reform. Given that ethical culture was introduced nearly forty years ago, these limitations are as understandable as they are in need of resolution. Much less was known about multilevel theorizing and conceptual clarity when ethical culture was initially introduced. Fortunately, there is now much more guidance on the above issues. The remainder of this work updates this existing conceptual domain in light of advances in these areas and proposes solutions to identified problems.

2.3. Stage 3: Organize the Conceptual Domain and Develop a Preliminary Definition

2.3.1. Identify a Theoretical Framework to Organize Attributes

Although there are existing limitations, aspects of the conceptual domain of ethical culture are useful and clear. In accordance with best practices for conceptual revision, we next incorporate conceptually useful themes identified in Stage 1 into the revised model (Stage 3a in Figure 1). This enables revised concepts to both build upon past knowledge while also addressing existing limitations (Makowski, Reference Makowski2021; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Harrison, Carpenter and Rariden2016; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2016). These themes are consolidated using a theoretical framework (Stage 3b in Figure 1), which provides a basis for organizing different environmental features as part of ethical culture and proposes an internal structure (Limitation 1).

We use the cultural dynamics model to this end (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). The cultural dynamics model builds on Schein’s (Reference Schein1985) three-level model and comprises four interrelated subdimensions: artifacts, symbols, values, and assumptions. It helps distinguish ethical culture from related concepts like climate by emphasizing deeper, less overt meaning structures (i.e., assumptions, beliefs, symbols; Limitation 5). It also creates the opportunity to integrate the definitional attributes from the existing literature that were unaffected by conceptual limitations and that mirror aspects of Schein’s model (e.g., Treviño, Reference Treviño1990; Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Wood and Chonko1989). Moreover, the cultural dynamics model creates clearer boundaries about what should and should not be considered ethical culture (Limitation 4).

2.3.2. Identify Potential Necessary and Sufficient Attribute(s)

A strong conceptual definition for ethical culture needs at least one distinctive attribute that highlights which aspects of culture generally are the most important for understanding ethical issues (Stage 3c in Figure 1). This attribute must be distinct from outcomes (Limitation 3) and logically apply to cultural systems (Limitation 2). Roy et al. (Reference Roy, Newman, Round and Bhattacharya2024) suggested that ethical culture research should engage with outside disciplines to further develop this area of work. Consistent with this advice, we drew on the anthropological concept of ethical affordances to accomplish these goals.

Affordance theory is an interactionist theory that depicts how aspects of the environment offer possibilities for people to engage in the environment in a certain way (Gibson, Reference Gibson1979; Scarantino, Reference Scarantino2022). Without considering its affordances, a chair is just a set of planks and shafts attached together. When thinking about its affordances, a chair offers a place to sit down or change a lightbulb (Mead, Reference Mead1934). Social contexts operate similarly (Reis, Reference Reis2008). Brushing one’s teeth is unlikely to afford the possibility of showing courage, but witnessing a coworker being mistreated can. Cultural systems also offer affordances. Culture offers ways of navigating life, constructing meaning, defining experiences, or perceiving the world (Kitayama, Mesquita, & Karasawa, Reference Kitayama, Mesquita and Karasawa2006; Miyamoto, Nisbett, & Masuda, Reference Miyamoto, Nisbett and Masuda2006; Ramstead, Veissière, & Kirmayer, Reference Ramstead, Veissière and Kirmayer2016). People can engage with cultural affordances in intentional ways as well as in ways that operate below conscious levels.

Ethical affordances are an extension of affordance theory that refer to aspects of people’s environment that are used to make moral judgments of their own or others’ behaviors (Keane, Reference Keane2014a). Ethical affordances are about the environmental features that are saturated with meaning about right and wrong. Material objects and nonphysical sociocultural entities are all examples of ethical affordances (e.g., narratives, practices, language, law, rituals, symbols; Keane, Reference Keane2014b). Stories shared by organizational members or the code of conduct are examples of elements of culture that may inform meaning about right or wrong. When something offers an ethical affordance, it can direct attention toward ethical issues (Keane, Reference Keane2014a). An example from ethical culture includes language, which can direct attention toward or away from moral considerations. Ethical affordances may also inform moral thinking that is less explicit. Seeing an inspirational quote has been shown to activate a moral mindset without rising to the level of deliberate contemplation (Desai & Kouchaki, Reference Desai and Kouchaki2017).

These arguments suggest that aspects of organizational culture offer ethical affordances. Viewed this way, ethical culture refers to employees’ shared perceptions of the aspects of organizational culture—artifacts, values, symbols, and assumptions—that operate as an ethical affordance. These cultural materials supply meaning about right from wrong, prompt reflections on moral implications of experiences, direct attention, and enable evaluations of behavior. This could occur in both conscious and less conscious ways. From this logic, we offer the following general definition of ethical culture:

The shared perceptions of artifacts, symbols, values, and assumptions that inform right from wrong in the workplace.

Ethical culture is distinct from ethical climate based on its combined focus on artifacts, symbols, values, and assumptions—particularly due to the more subconscious components. The focus on ethical affordances separates ethical components of culture from the rest (necessary attribute). Jointly, these attributes are sufficient to distinguish ethical culture from related concepts.

2.3.3. Definitions of the Subdimensions of Ethical Culture

Using the cultural dynamics model, we specify the dimensionality of ethical culture (Stage 3d in Figure 1). To address confusion between the nomological network and conceptual domain, our subdimensions exclude leadership (Limitation 4) and include elements that are commonly attributed to culture (e.g., assumptions, symbols, moral norms; Limitation 5).

Ethical culture contains artifacts, which we define as shared perceptions of visible, tangible, or audible objects or entities that inform right from wrong in an organizational context. Artifacts are the material forms of ethical culture and can be directly perceived (e.g., visually, auditorily). Much of Treviño’s (Reference Treviño1990) ethical culture is incorporated into this subdimension: language around ethics, codes, orientation and training programs, rewards, sanctions, rituals, myths, and stories. An employee can consult a code of ethics to help them reflect on a morally questionable situation, direct attention toward the problem, and provide guidance on how to proceed (DeBode et al., Reference DeBode, Armenakis, Feild and Walker2013). The university ritual of signing the honor code or using ethics-related language in newsletters are also examples of artifacts (Eury & Treviño, Reference Eury and Treviño2019).

The cultural dynamics model distinguishes artifacts from symbols (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Symbols are signs or representations of deeper meanings (Gioia, Thomas, Clark, & Chittipeddi, Reference Gioia, Thomas, Clark and Chittipeddi1994). According to the cultural dynamic model, symbols are artifacts that have “conscious or unconscious association with some wider, usually more abstract, concept or meaning” (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993: 669). All symbols are artifacts, but not all artifacts are symbols. Symbolism is identified by comparing the artifact’s full meaning to its literal meaning, with the difference being “surplus” symbolic meaning (Ricoeur, Reference Ricoeur1976). A corner office is literally a square room with a door and perhaps several windows, but the added symbolic meaning is of success and status. Symbols of ethical culture are defined as shared perceptions of artifacts that inform right from wrong in an organizational context and have surplus meaning.

Symbols are an important yet understudied component of ethical culture, and they differentiate culture from climate. The actual artifact itself seems less central for understanding ethics in organizations than its surplus symbolic meaning. Approaches for handling sexual harassment, for example, have been interpreted as a shield to protect employees or as a weapon to target the accused (Dougherty & Goldstein Hode, Reference Dougherty and Goldstein Hode2016). The literal, nonsymbolic purpose of the ritual of signing the honor code is to convey the information in the honor code and have students sign off to confirm their understanding. Students have interpreted this ritual to have additional symbolic meaning of creating a burden to report others (McCabe, Trevino, & Butterfield, Reference McCabe, Trevino and Butterfield1999). The literal meaning of ethics training is to teach employees how to respond to moral dilemmas, but research shows that some symbolize them as finger-pointing exercises (Jovanovic & Wood, Reference Jovanovic and Wood2006).

The third subdimension is cultural values (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Generally, cultural values constitute social expectations, and they provide information about appropriate behaviors (Hartnell, Ou, & Kinicki, Reference Hartnell, Ou and Kinicki2011). They reflect shared ideologies, justifications, or philosophies (Schein, Reference Schein1990). Integrating perspectives from the existing conceptual domain, we suggest that ethical values are shared perceptions of ideals, norms, and standards that indicate acceptable treatment of other entities (e.g., people, the natural environment) in an organizational context. Strong ethical values that align with the mission or vision of the organization are considered central for a well-developed ethical culture (Ardichvili, Mitchell, & Jondle, Reference Ardichvili, Mitchell and Jondle2009). Victor and Cullen’s (Reference Victor and Cullen1988) norm-based view of ethical climate aligns with this definition and should therefore be viewed as an element of ethical culture—not ethical climate. Their work suggests organizations differentially value care, self-interest, external laws, organizational rules, or independent moral judgment. Norms of obedience and balancing the needs of different stakeholders, identified in Stage 1, also fit this definition.

Finally, some part of culture operates at more subconscious, subtle, and automatic levels. This aspect of culture in organizations has been described as taken-for-granted assumptions, unacknowledged beliefs held by employees (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993), or cultural schemas operating below awareness (Boutyline & Soter, Reference Boutyline and Soter2021). Cultural assumptions have more subtle motivational influences, tapping into less conscious forms of cognition (Vaisey, Reference Vaisey2009). Assumptions shape what people see and where their attention is directed (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993; Schein, Reference Schein1990). Although assumptions are part of organizational culture (Denison, Reference Denison1996; Martin, Reference Martin2001), they are relatively under-studied in ethical culture research. Like symbols, subconscious assumptions are another key part of what distinguishes culture from climate and therefore should be an area of focus for ethical culture researchers.

For ethical culture, we define assumptions as shared taken-for-granted beliefs that inform right from wrong in an organizational context. Shared cultural assumptions appear to reflect reality and provide a sense of order. They define what is expected or seems “known.” Assumptions of ethical culture constitute perceived knowledge about what is good or bad or how things work regarding ethics. Assumptions would shape what employees notice or do not notice as morally problematic or morally good in the context of their culture. They direct attention toward what is perceived as morally good or bad and can change saliency of moral issues.

Some assumptions could be that companies must be ethical to survive or that companies need to meet expected performance metrics at all costs, including through fraud (DeBode et al., Reference DeBode, Armenakis, Feild and Walker2013). Another assumption is that people are primarily driven by self-interest (Ghoshal, Reference Ghoshal2005). This could implicitly shape whether or how people notice, react to, or interpret self-interested behavior. This assumption could result in the perception that self-interest is not morally problematic. Ghoshal (Reference Ghoshal2005) noted that this assumption is embedded in ways of viewing economic and organizational activity, and it shapes the world views of managers and employees who come to expect such behavior. Belief in a just world—the belief that the world is fair and that people get what they deserve (Furnham, Reference Furnham2003)—also seems to fit as an assumption of ethical culture. This belief asserts that good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people. It creates “psychological buffers against the harsh realities of the world” because it reassures people that they will not experience something bad if they are generally good (Furnham, Reference Furnham2003: 796). Belief in a just world blunts reactions to injustice and prompts victim blaming. Each of these assumptions constitute perceived knowledge about morality and would direct attention in terms of what is or is not noticed as right or wrong.

2.3.4. Subdimension Interrelations

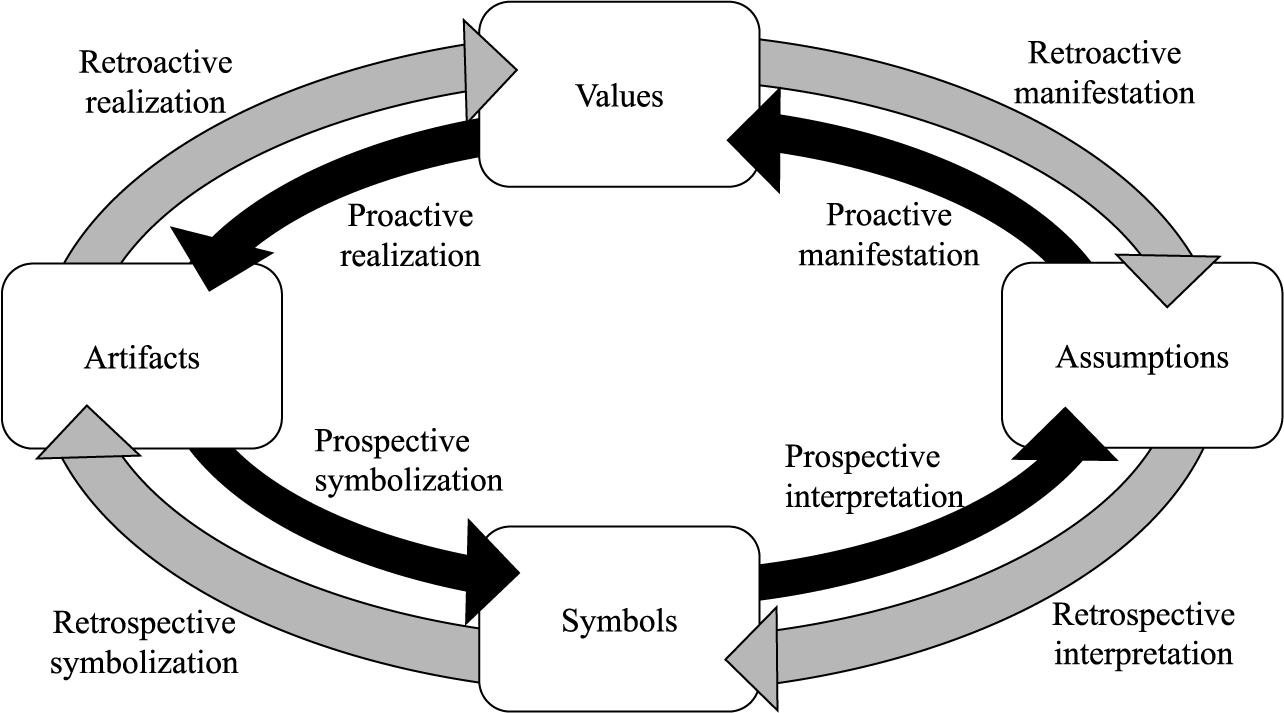

A benefit of the cultural dynamics model is that it highlights potential internal relationships that have not been a focus of previous ethical culture research (Limitation 1). The four subdimensions of the cultural dynamics model influence one another in a bidirectional way (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). We describe these processes and how they relate to ethical culture (Figure 2). These cultural dynamics are theorized to be ongoing and could occur and recur simultaneously. Each relationship will not necessarily always be triggered. We describe conditions that could trigger them.

Figure 2: Dynamic Relationships Among Ethical Culture Sub-Dimensions

In Hatch’s (Reference Hatch1993) cultural dynamics model, manifestation refers to the bidirectional relationship between assumptions and ethical values. Proactive manifestation occurs when assumptions subconsciously “provide expectations that influence perceptions, thoughts, and feelings about the world and the organization” (1993: 662). Assumptions accomplish this by narrowing the field of vision and guiding what employees pay attention to. To employees, these perceptions, thoughts, and feelings seem to reflect the world; they reflect reality. Corresponding cultural values would form based on the extent to which they like or dislike these reflections. Consider the assumption that self-interest is a primary driver of human behavior. Employees may notice self-interested behaviors, come to expect it, and interpret ambiguous behavior or even pro-social behavior as actually caused by it (i.e., there is no true altruism). This assumption, by subconsciously shaping what employees pay attention to and think, could promote self-interest as an acceptable cultural value if it seems to “work.”

In addition to assumptions revealing themselves as values in proactive manifestation, ethical values may reciprocally influence assumptions through retroactive manifestation. In retroactive manifestation, values may either maintain or challenge existing assumptions. Values that align with tacit assumptions provide organizational members with a sense of continuity within the belief system, and the cultural system appears to function normally. Values buttress assumptions during periods of harmony. However, new and inconsistent values can emerge from, for example, changes in leadership or exogenous shocks. Consider the new values, such as populism, that came from the 2008 financial crisis (Guriev & Papaioannou, Reference Guriev and Papaioannou2022). If new values are repeatedly affirmed as useful, they will morph into taken-for-granted assumptions over time. Some values may not be viewed as useful by organizational members, and they would fail to eventually form into assumptions.

The previous discussion on manifestation refers to the links between assumptions and values. The cultural dynamics model also portrays realization, which is about the bidirectional influence relations between values and artifacts (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Proactive realization occurs when shared values spur activities that create cultural artifacts. This process is about how espoused values are implemented, materialized, or enacted upon by organizational members. Values can be proactively realized through the production of objects, events, or discourse. An example would be if the value of care motivates members of the organization to create an organizational citizenship award. If ethical values do not stimulate the actions of organizational members, there are limited mechanisms by which they receive tangible form. Conversely, artifacts may initially be incongruent with cultural values, perhaps produced by some external event or environmental pressure. Culturally incongruent artifacts face several possibilities (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). If deemed illegitimate, organizational members may ignore them or remove them, resulting in a failure to incorporate the new artifact into the cultural system. If deemed legitimate, they would cause a shift in cultural values until values are congruent with the artifact during what Hatch calls retroactive realization. Unjustified police killings of Black Americans caused many organizations to respond by introducing new programs to create more diverse and inclusive workplaces circa 2020 (Friedman, Reference Friedman2020). In some organizations, these new artifacts may have been deemed legitimate and retroactively promoted the value of social justice.

The dynamic model also proposes symbolization processes (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Symbolization is about the connection between artifacts and their wider, more abstract symbolic meanings. Prospective symbolization occurs when artifacts accrue surplus, symbolic meaning. According to the cultural dynamics model, all symbols begin as artifacts. Some artifacts accrue surplus symbolic meaning over time if they are viewed as significant or important. Many organizations, particularly large corporations, have similar cultural artifacts intended to operate as ethical affordances, such as a code of ethics (Sharbatoghlie, Mosleh, & Shokatian, Reference Sharbatoghlie, Mosleh and Shokatian2013); however, the nature and level of their symbolic meanings vary (Treviño, Weaver, Gibson, & Toffler, Reference Treviño, Weaver, Gibson and Toffler1999). The code of conduct is literally a list of rules for employees to follow. The code of conduct may not be symbolically significant, failing to go through prospective symbolization. Conversely, the code of conduct may have more symbolic meaning, perhaps as a map for navigating issues or as a source of protection. The literal meaning of symbols may also be brought to the forefront during retrospective symbolization (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993). Returning to the previous example, diversity initiatives may have taken on the symbolic meaning of supporting social justice. However, increased scrutiny can be placed on their literal meaning due to a lack of real change (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Milkman, Gromet, Rebele, Massey, Duckworth and Grant2019). The misalignment between symbolic and literal meanings could cause the literal meaning of the artifact to be reemphasized and the symbolic meaning to be revised during retrospective symbolization.

Interpretation “involves a second-order experience of symbolization” (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993: 674). Interpretation establishes meaning. During interpretation, symbolic meaning interrelates with taken-for-granted assumptions. Cultural assumptions represent structures of knowledge about morality—what seems to be “already known,” expected, or taken as a given. The broader system of assumptions influences symbolic meaning during retrospective interpretation. That is, the symbolic meaning attributed to artifacts is created based on the perceived knowledge and expectations about morality contained within cultural assumptions. Consider again finding that some people symbolically view rules for handling sexual harassment as weapons (Dougherty & Goldstein Hode, Reference Dougherty and Goldstein Hode2016). Belief in a just world (good things happen to good people; bad things happen to bad people) and the assumption that people are naturally self-interested could have driven this symbolic meaning. Belief in a just world results in victim blaming because the victim is thought to have caused their circumstances (Furnham, Reference Furnham2003). This assumption could draw attention away from the potential protective functions of these policies. Combining this with the assumption that people are self-interested could shape the expectation that people would use these policies as a weapon for personal advantage. In this case, retrospective interpretation takes place as new symbolic meanings form based on what is already known (assumptions).

A central theme in interpretative processes is that there are reciprocal influences between assumptions and symbols (Hatch, Reference Hatch1993: 674). Sometimes symbolic meanings form that are incongruent with taken-for-granted assumptions. Prospective interpretation describes that symbolic meanings may revise cultural assumptions. Belief in a just world could be challenged after observing a colleague struggle with being harassed. In such a case, symbolic meanings around rules for addressing sexual harassment could be revised. Rather than viewing them as a weapon, they may be viewed more like a shield or even an ineffective tool. In turn, this experience and new symbolic meaning could challenge the view that bad things only happen to bad people and could prompt a shift in the underlying belief in a just world.

2.4. Stage 4: Present Final Revised Conceptual Definitions

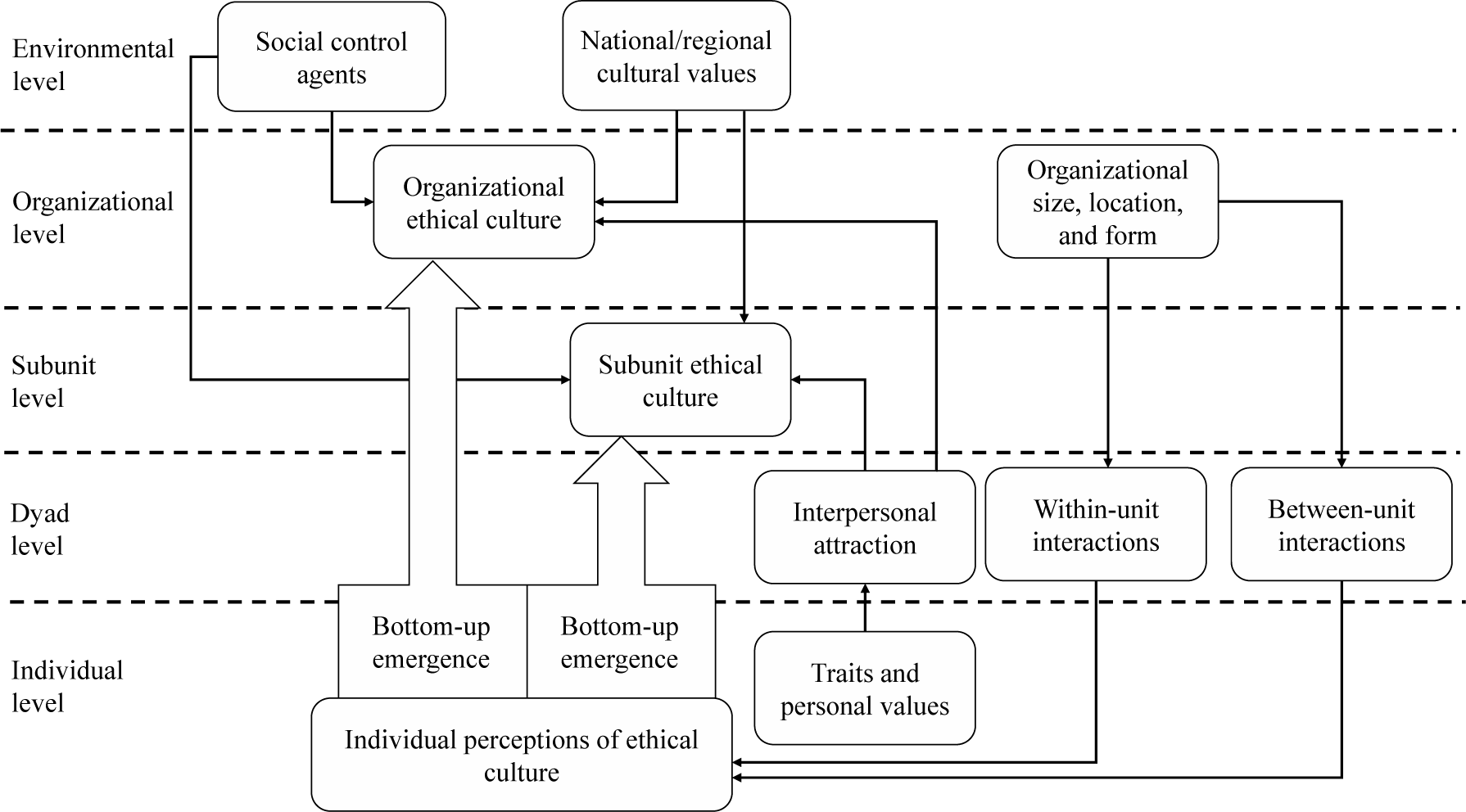

In Stage 4, we present the final revised conceptual definitions for ethical culture. These definitions are based on the conceptual foundation of the subdimensions proposed in Stage 3. To resolve conceptual Limitation 6, there needs to be a definition for each identified level of theory (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mathieu, Bliese, Yammarino and Dansereau2005). It is also important to portray potential bottom-up and top-down influences that depict whether and how ethical culture manifests at each level (Limitations 7 and 8). We next present a multilevel model of ethical culture to satisfy these considerations. Some multilevel processes are described presently (see Figure 3), but there are likely others that could also be explored.

Figure 3: A Multi-Level Model of Proposed Top-Down and Bottom-Up Relationships

2.4.1. Ethical Culture at the Organizational Level: A Definition and Exploration of Top-Down Influences

At the organizational level, culture reflects a collectively held schema that internally integrates and coordinates employees (Ostroff et al., Reference Ostroff, Kinicki, Muhammad, Weiner, Schmitt and Highhouse2012). Organizational ethical culture is typically viewed as the shared perceptions of organizational members. We therefore define organizational ethical culture as organizational members’ shared perceptions of values, taken-for-granted assumptions, artifacts, and symbolic meanings that inform right from wrong in the workplace. Thus, organizational ethical culture represents the landscape of culturally based ethical affordances that are commonly accepted or perceived by organizational members. Shared perceptions of ethical culture manifest at the organizational level when there is greater integration across different subunits or hierarchical layers (Chan, Reference Chan, Schneider and Barbera2014). As we depict in the subsequent section, some organizations have a weak or fragmented organizational ethical culture. In these cases, subunits may be the level at which perceptions of culturally based ethical affordances are more strongly shared.

One top-down influence that could affect organizational-level ethical culture is externally mandated ethical guidelines and rules. Greve, Palmer, and Pozner (Reference Greve, Palmer and Pozner2010) use the term “social-control agent” to refer to external entities that control the ethics of organizations. Environmental social-control agents include professional associations (e.g., the American Bar Association), states (e.g., national or local law), and international governing bodies. Such top-down processes should primarily influence the formation of new artifacts. Consider the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, perhaps one of the most important policies capable of influencing the ethical cultures of organizations in the United States (Treviño & Nelson, Reference Treviño and Nelson2017). The guidelines incentivize the creation of artifacts to discourage misconduct, such as creating compliance standards and disciplinary mechanisms for lack of compliance. New artifacts introduced by the social-control agent could stimulate retroactive realization, during which new artifacts might create a shift in ethical values. If the new value is repeatedly reinforced as useful, it may eventually create an assumption through retroactive manifestation. New artifacts may also acquire symbolic meaning during prospective symbolization. The introduction of new artifacts from the social-control agent could potentially shift the entire cultural system.

Organizations are also nested within larger social structures. National or regional factors could create top-down influences on organizational ethical culture. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions offer a glimpse into some of these potential top-down influences. Developed using data from over forty countries, Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions vary across nations based on individualism/collectivism (prioritization of the self/immediate family compared to prioritization of ingroups/larger social frameworks), power distance (acceptance of uneven power distribution), uncertainty avoidance (feelings of insecurity or threat from uncertainty), masculinity/femininity (focus on assertiveness, acquisition of money and things compared to focus on caring for others), and long-/short-term orientation (emphasis on future or present; Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1980). Perhaps the primary route by which these national or regional factors would affect organizational ethical culture in a top-down way would be through organizational values as values are also the focus of the Hofstede model. Organizational ethical cultures in countries higher on femininity may have higher organizational values of care, or power distance at a national level could influence organizational norms of obedience. Should national or regional culture influence values in organizational ethical culture, it could prompt further changes to other elements of the model. Value-congruent artifacts could form through proactive realization. Research has found language about ethics, a type of artifact, varies based on these broader cultural dimensions (Scholtens & Dam, Reference Scholtens and Dam2007). Such values could also influence assumptions through retroactive manifestation.

2.4.2. Ethical Culture at the Subunit Level: A Definition and Theoretical Depiction of Subunit Ethical Culture Manifestation

Cabana and Kaptein (Reference Cabana and Kaptein2021) observed that a majority of ethical culture research is about consensus among organizational members and that insufficient attention has been paid to subunit differentiation within organizations. Our own analysis confirms their view, indicating that an overwhelming emphasis on organizational ethical culture (97 percent of articles) to the neglect of exploration of subunit differentiation (6 percent of articles; see Cabana & Kaptein, Reference Cabana and Kaptein2025; Schaubroeck et al., Reference Schaubroeck, Hannah, Avolio, Kozlowski, Lord, Treviño, Dimotakis and Peng2012 for exceptions). This is notable as some have argued that subunits should be the primary level of theory for culture because many modern organizations are too large and complex to have a strong organizational-level culture (Ostroff et al., Reference Ostroff, Kinicki, Muhammad, Weiner, Schmitt and Highhouse2012). To help address limitations related to levels of analysis, more focus on subunit ethical culture is needed. Presently, subunit ethical culture is defined as sub-unit members’ shared perceptions of artifacts, symbols, values, and assumptions that inform right from wrong in the workplace. Unique subunit ethical cultures would occur when there is both within subunit agreement and between subunit differentiation. If there is no variation between subunits, all the subunits in an organization would be the same and no defined subcultures would exist. If there is no within subunit agreement, there are no shared perceptions of ethical culture at all. Thus, both are needed for the subunit to be a relevant level of theory.

Developing theory around conditions that give rise to within subunit agreement and between subunit variation becomes an important follow-up consideration. In particular, potential lower-level interactions that prompt emergence of either subunit or organizational ethical culture should be described (Morgeson & Hofmann, Reference Morgeson and Hofmann1999). Simon’s (Reference Simon1962) depiction of fully and nearly decomposable systems helps portray when distinct subunits manifest within a larger system by focusing on the relative strength of connections within subunits (i.e., interactions among employees within the same subunit) and between subunits (i.e., interactions among employees from different subunits). Fully decomposable systems are those that have no connections between subunits yet have connections within subunits. Organizations are typically nearly decomposable systems that are characterized by relatively weak yet nonzero between-unit interactions and stronger within-unit interactions. An example could be if faculty at a university largely interact with members of their own department or college. Occasionally, faculty might interact with members of other departments or colleges, but these interactions might be comparatively less frequent than within department/college interactions.

The idea of nearly decomposable systems highlights several relevant organizational-level factors that would shape the formation of subunit ethical cultures. The size and geographic dispersion of organizations are organizational-level factors that would exert top-down influences on subunits (Schein, Reference Schein2017). In larger or geographically dispersed organizations, distinct subunit ethical cultures may be more likely to manifest because between-unit interactions would be curtailed, and within subunit interactions would be more likely. Smaller and/or more geographically centralized organizations should have comparatively more between-unit interactions and thus less prominent subunit ethical cultures.