Introduction

Populism puts ‘the people’ central in political decision‐making. Its central claim is that political power should reside with the people, as opposed to the elites (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). To study populist beliefs at the individual level, scholars recently developed the populist attitude scale (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012). Research on both the individual and the party level has found that populism is a diverse phenomenon, applicable to inclusive left‐wing ideologies and exclusionary right‐wing ideologies (Meijers & Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel, Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018). Indeed, populism is thought to be a thin‐centred ideology that is usually attached to ‘full’ ideologies, such as socialism or nationalism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). As a result, the concept of populism remains agnostic about who constitutes the people.

In civic terms, we can think of the people as ‘citizens’ (e.g., Almond & Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963). In ethnic terms, ‘the people’ can refer to a more cultural understanding of folk. While in some cultural contexts, there is no strong semantic difference between ‘the people’ and ‘citizens’ (e.g. in the English‐speaking world), in many other contexts, ‘the people’ (i.e., das Volk) has a strong ethnic connotation. For example, in Italian il popolo has a stronger ethnic character than i cittadini or le persone. In Polish, the term naród signifies the ‘nation’ as an ethnic group, compared to społeczeństwo (‘the public') (Zubrzycki, Reference Zubrzycki2001). While this difference is particularly outspoken in German, the difference exists in more Germanic, Slavic and Roman languages. In the 1800s, the term Volk and völkisch became strongly associated with an ethnic and racial conception of ‘Germanness’. After World War I, the terms Volk and Volksdeutsche were used to describe an ethnically and culturally homogeneous German diaspora, who were citizens of different states after the Versailles Treaty of 1919 (Gosewinkel, Reference Gosewinkel2003). Das deutsche Volk was also used by the Nazis to delineate ethnic Germans from non‐ethnic Germans. In 1935, poet and playwright Bertold Brecht, therefore, called for the use of Bevölkerung (‘population’ or ‘the public') instead of Volk to avoid the Nazis’ “foul mysticism” (Brecht, Reference Brecht1993).

Scales of populist attitudes have mostly relied on ethnic conceptions of the people (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2018; Van Hauwaert et al., Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo2020). At the same time, populist attitude scales have often been inconsistent in juxtaposing the elites with ‘the people’ or with ‘citizens’. For instance, the scale proposed by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) primarily refers to ‘the people’. Yet one item in the Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) scale contrasts ‘the citizen’ with ‘politicians’ (POP4) – an item that nonetheless contributes significantly to the latent construct of populism (Van Hauwaert et al., Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo2020). It is also likely that differences arise from inconsistencies across translations of the original survey items. For instance, ‘the people’ has been translated differently in different translations of the populist attitude scale. For instance, in the French context ‘the people’ has been translated as le peuple in some items but as les citoyens in other items (Ivaldi, Reference Ivaldi2018). Yet another study of French citizens refrains from using either le peuple or les citoyens, choosing the more neutral les gens instead (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). In Italian, ‘the people’ is sometimes referred to as il popolo, and sometimes as le persone (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). In Polish, ‘the people’ has been measured as społeczeństwo (‘the public') and the more ethnic naród.

The underlying assumption is that the different conceptions of the people (i.e., civic or ethnic) functions similarly – also known as measurement invariance or measurement equivalence.Footnote 1 In this paper, we test the degree to which the populist attitude scale is invariant across civic and ethnic conceptions of the people: That is, do people exposed to a civic conception of the people have a similar populist attitude score as people exposed to an ethnic one? This is important because populist attitudes aim to operationalize populism as a ‘thin ideology’ as propagated by Mudde (Reference Mudde2004). This perspective posits that populism is usually combined with other, left‐ or right‐wing, ideologies. Hence, the populist attitude scale should capture populist ideation across different ideological predispositions. In a similar vein, Castanho Silva et al. (Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020) criticize populist items scales which include nativist items.

Using a wording experiment in Germany (N = 7,034), we examine measurement invariance across ethnic and civic conceptions of ‘the people’.Footnote 2 First, we study whether an ethnic or a civic conception of the people affects respondents’ agreement with the two items of the populist attitude scale that directly juxtapose ‘the people’ with the elites – i.e., assessing structural, metric or weak invariance (Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, Reference Hirschfeld and Von Brachel2014).Footnote 3 We further examine this structural invariance, by testing whether far right voters and respondents with an exclusive national identity respond differently to ethnic conceptions of the people. In addition, we examine whether the differences found to affect the overall latent construct of populist attitudes, examining whether the intercept and the error terms are invariant (i.e., scalar and strict invariance) (Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, Reference Hirschfeld and Von Brachel2014). We show that the populist attitudes scale based on a civic conception is not the measurement equivalent of the one using the ethnic conception. The assumption of measurement invariance is thus not met. Using a civic conception leads to higher scores on the populist attitude scale compared to using an ethnic conception. This suggests that the way in which the people is conceptualized has important implications for the measurement of populist attitudes as well as for its explanatory power. Our findings also suggest that political scientists should pay much more attention to the translations they commission for their surveys. While new survey items are carefully constructed, translations are often not put to the same scrutiny. We demonstrate that by choosing certain translations over others (e.g., Volk for the ‘people') this slightly changes the measured concept. As a result, instead of measuring populist attitudes, one also measures a nativist component. Hence, by relying on careless translations we run the risk of imprecise and biased measurement.

A civic versus ethnic conception of ‘the people'

To test whether an ethnic or civic framing of the people affects respondents’ agreement with key populist items, we conduct a wording experiment. Wording experiments have been used in political science to assess how different question phrasing affects respondents’ perceptions of concepts, such as issue ownership (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Van Camp, Lefevere and Tresch2016), climate change (Schuldt et al., Reference Schuldt, Konrath and Schwarz2011) and party identity (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Burton and Kneeshaw2002). We rely on a nationally representative sample of German citizens over 18 years old (N = 7,034). Given the more pronounced ethnic connotation with the concept of ‘people’ or Volk in the German language, the German case is particularly suitable to tease out differences between ethnic and civic conceptions of the people in key populist attitude items. Our sample is from an online panel provided by the survey company Respondi – for an overview of all variables in the study, as well as the descriptive information, see the Online Appendix (OA; pp. A2–A6). Quotas for age, gender, and education were included to ensure the representativeness of the sample. We have 3,507 respondents in the group that received the ethnic phrasing and 3,527 respondents in the group with the civic phrasing. This large sample size also allows us to detect small effects of question wording differences.Footnote 4

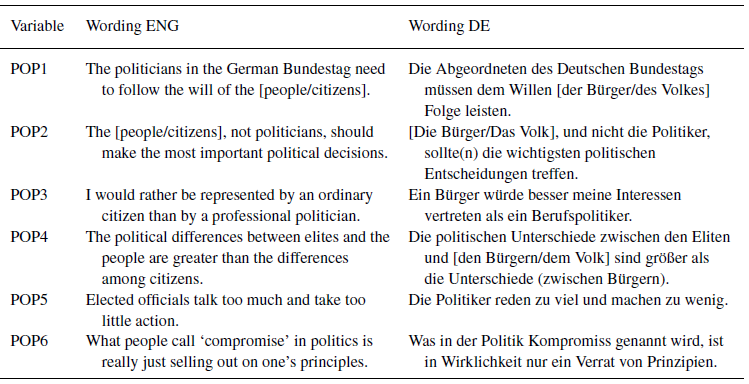

To examine whether civic conceptions of the people elicit different responses than ethnic conceptions, we experimentally vary the wording of two of the six items in the scale proposed by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) (see Table 1). In the original Akkerman et al. scale deployed in the Netherlands, the items POP1 and POP2 were phrased in ethnic terms (i.e., with reference to het volk). We randomize whether respondents received an ethnic framing (i.e., with reference to ‘the people; or das Volk) or a civic framing (i.e., with reference to 'citizens’, or Bürger). A balance test, reported in our https://github.com/MarikenvdVelden/wording‐experiment‐populist‐attitudes (Online Research Compendium), demonstrates that the allocation of the treatment was fully random. The upper two items in Table 1 show the differences in wording for the two items POP1 and POP2 in English and German. All the other items were kept constant.Footnote 5

Table 1. Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) populist attitudes scale

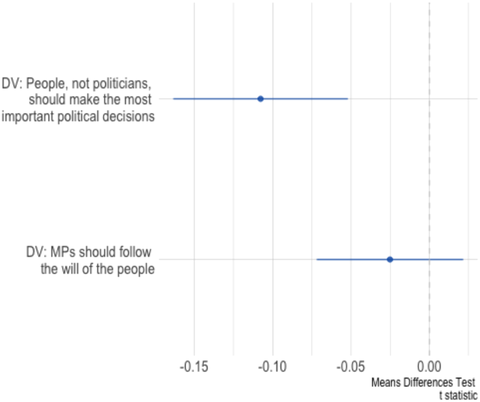

Figure 1 shows the results of a difference of the means test for the two treatment groups (ethnic vs. civic wording) for both items – Table A.5 in the OA shows the coefficients. There is a statistically significant difference in respondent agreement with the ethnic and civic conceptions of the people for the item POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions') but not for POP1 (‘The politicians need to follow the will of the people'). The negative coefficient for POP2 indicates that when ‘the people’ is conceived as das Volk respondents are more likely to agree with the item's statement compared to the civic wording of Bürger. Yet, as the results show, the difference is small in substantive terms.

Figure 1. Differences in ethnic and civic conceptions of the people. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

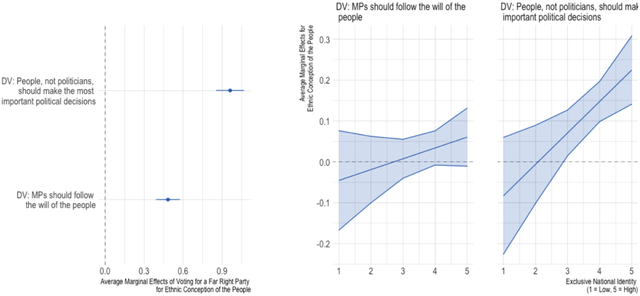

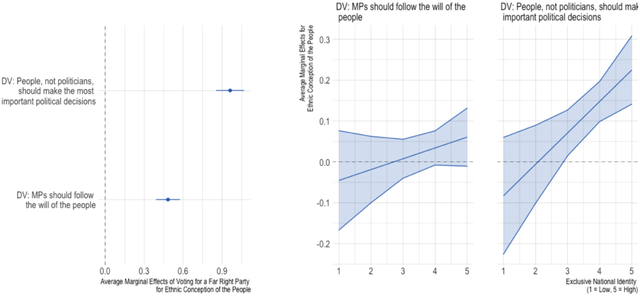

How does the effect of an ethnic conception of the people vis‐à‐vis a civic conception of the people vary across respondents? The left‐hand panel of Figure 2 shows the results of an OLS regression analysisFootnote 6 with the interaction between the treatment and a variable measuring whether or not the respondent voted for the far‐right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) – for more details, see Table A.6 in the OA. We see that far‐right voters show much more agreement with items POP1 and POP2 when it is phrased in an ethnic way. These effects are substantial and statistically significant. For the item POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions'), when voting for the AfD and being in the ethnic conception of the people condition, one scores on average a full point higher on a 5‐point scale, which is about a full standard deviation. For the item POP1 (‘The politicians need to follow the will of the people'), the effect size is about half a point (i.e., half a standard deviation).

Figure 2. Average marginal effects for ethnic conception of the people. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the next step, we examine whether respondents with lower and higher levels of exclusive national identity are affected differently by the treatment. Inspired by Mader et al. (Reference Mader, Pesthy and Schoen2021), we measure exclusive national identity using a four‐item additive scale on a 5‐point Likert scale, which asks respondents to rate how important the following aspects are to be considered German: being born in Germany (a), having German ancestors (b), being able to speak German (c) and sharing German manners and norms (d). The right‐hand panel of Figure 2 shows the interaction effect between the treatment and the exclusive national identity variable on agreement with the two items – for more details, see Table A.7 in the OA. Compared to not adhering to an exclusive national identity, the average score of fully adhering to an exclusive national identity is 0.2 higher on a 5‐point scale for the item POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions'). Compared to the standard deviation of this item (1.17; see Table A.4 in the OA), this is a small effect. For the other item, the line is much less steep over the various levels of adherence to an exclusive national identity. Overall, we see that the difference between an ethnic and civic wording is only statistically significant for respondents with higher levels of exclusive national identity (ca. >2.5 on the exclusive national identity scale). Both the analyses from the left‐ and right‐hand panels of Figure 2 suggest that far‐right voters and respondents with an exclusive national identity interpret ‘the people’ (das Volk) in an ethno‐cultural way. The results of Figures 1 and 2 seem to suggest that the assumption of measurement invariance is not met, as we find a statistically significant difference for the POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions') item.

In addition, we have explored how the effect of an ethnic conception of the people vis‐à‐vis a civic conception varies across age and region. People that are born during or closely after WWII, as well as people born and/or living in certain regions in Germany (e.g., the East or Bavaria), could potentially have a different reaction to the two conceptions of the people – all figures can be found in the OA (Figure A‐2, p. A9) as well as in our https://github.com/MarikenvdVelden/wording‐experiment‐populist‐attitudes (Online Research Compendium). Age. We demonstrate in the upper‐left panel of Figure A‐2 in the OA that for younger age groups (i.e., all age groups younger than 50 years old) there is no difference between the civic and ethnic conceptions of the people. Yet, for the older population (50 years old and more), we see that people receiving the ethnic treatment report higher levels of agreement with the items compared to people receiving the civic treatment for both POP1 (‘The politicians need to follow the will of the people'), the effect size is about half a point (i.e., half a standard deviation) and POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions'). The effect size is still small in substantive terms: between a 0.1 and 0.3 increase on a 5‐point scale.

Region . We show in the upper‐right panel of Figure A‐2 in the OA that while for most regions in Germany, there is no statistically significant difference between receiving ethnic or civic treatment. Yet, for the regions Sleswig‐Holstein (i.e., the region bordering Denmark) and Hessen (mid‐Germany), we see that people receiving the ethnic treatment report lower levels of agreement with the items compared to people receiving the civic treatment for both POP1 and POP2. The same effect holds for the region Bremen for POP1 and for Berlin and North‐Rhine Westphalia for POP2. This could suggest that in Western districts people are sensitive to the ethnic conception of the ‘people’, and all else equal under‐report their populist attitudes by approximately 0.5 points on a 5‐point scale.

We also explored whether the difference between civic and ethnic conceptions is only present for voters of far‐right parties or also exists for people placing themselves on the edges of the ideological spectrum. An interaction between the treatment and ideological self‐placement – for more details, see the lower‐left panel of Figure A‐2 in the OA – demonstrates that for POP1 (‘The politicians need to follow the will of the people') there is a positive, yet insignificant, relationship between ideology and receiving the ethnic treatment, i.e., the more right‐wing, the higher your score on the item when receiving the ethnic treatment compared to the civic treatment. For POP2 (‘the people, not politicians, should make the most important political decisions’), we see the opposite: Left‐wing people report higher scores on this item when shown the ethnic conception of the people compared to the civic conception. Yet, the effect is substantially small, between approximately a 0.2 and 0.05 decrease on a 5‐point scale. This effect is negative, meaning that the more right wing a respondent is, the smaller the difference between the score for the item for the two treatments. The effect becomes insignificant for an ideology score of 7 and higher. In addition, we explored the differences between those who are opponents and proponents of political pluralism, as the civic conception of the people might invite a more pluralistic view on who are included in the people. The lower‐right panel of Figure A‐2 in the OA demonstrates the opposite: Respondents who are negative towards political pluralism (i.e., low scores) and that receive the ethnic treatment, report lower levels of agreement with the items compared to those who are positive towards political pluralism (i.e., high scores) for both POP1 and POP2. This effect is bigger for POP2 than for POP1.

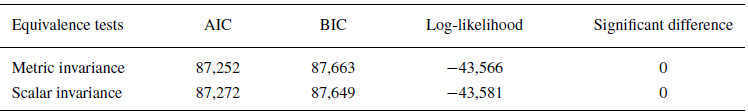

Does an ethnic and civic framing of the items POP1 and POP2 affect the measurement invariance assumption of the latent construct of populist attitudes? To answer this question, we cannot just compare the means of the group, since we would assume that the measures function similarly in these different groups (e.g., see Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, Reference Hirschfeld and Von Brachel2014; Van de Vijver and Leung, Reference Van de Vijver and Leung2021; Bieda et al., Reference Bieda, Hirschfeld, Schönfeld, Brailovskaia, Zhang and Margraf2017). We therefore need to test the degree to which measures are invariant across groups. To do so, multiple‐group confirmatory factor analysis (MG‐CFA) has become the de facto standard in psychology (Chen, Reference Chen2008). We first test the measurement variance in a confirmatory factor analysis (see Table A.9 in the OA). The averages of the civic and ethnic conception scales of populist attitudes differ significantly: Respondents exposed to the civic conception score higher (0.44 on a 5‐point scale) on the populist attitudes scales than respondents in the ethnic conception condition. In terms of model fit, both constructs show very similar goodness‐of‐fit statistics (i.e., CFI, BIC, RMSEA and SRMR)Footnote 7. Interestingly, however, both the ‘ethnic’ and the ‘civic’ scales show a satisfactory model fit (CFI > 0.9; RMSEA < 0.08; and SRMR < 0.02) – for more information, see OA Table A.8. Moreover, when testing metric and scalar invariance – i.e., is the magnitude of loadings similar across groups or are the magnitude of loadings and the intercept difference across groups – we find statistical significant chi‐square differences for the metric invariance and scalar invariance models, shown in Table 2. This indicates that the assumption that the different conceptions of the people function similarly is not met.

Table 2. Measurement invariance: CFA models

Additionally, we have estimated a graded item response theory (IRT) analysis (see also Van Hauwaert et al., Reference Van Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo2020). This scaling model shows that POP1 and POP2 contribute slightly more information to the latent construct when the items are ethnically phrased, as opposed to a civic framing (see Figure A.5 and Table A.13 for more information in the OA). While the means of the scales with the different conceptions of the people are not different, testing metric and scalar invariance – see Table 3 – we see that the equal slope assumption (metric invariance) as well as one form of scalar invariance (i.e., the one with free means) are not met. This indicates that even varying the wording of ‘the people’ in two items of the full Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) item battery is enough to demonstrate that the scales are not equivalent anymore.

Table 3. Measurement invariance: IRT models

Moreover, we have created an additive scale (see Table A.11 in the OA) as well as constructed a scale using the approach of Wuttke et al. (Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020) (see Table A.12 in the OA) – i.e., using the lowest value on one of the items that construe the latent construct. For both scales, we find statistical significant average values for the scales based on ethnic and civic conceptions of the people. For both scaling methods, people in the civic conception have on average a higher mean value compared to the ethnic conception. While we are not able to formally test all forms of measurement invariance, a statistically significant mean here suggests that the measurements are not equivalent.

Conclusion

The populist attitude construct aims to operationalize populism as a thin‐centred ideology on the individual level (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012). From this perspective, populist ideation is present both on the left and the right side of the political spectrum. The concept ‘the people’ is an empty signifier that is discursively filled in different ways by left‐ and right‐wing populists. Therefore, it is important that the ‘populist attitudes’ construct is not biased towards one group or the other. Yet, existing populist attitudes scales have been inconsistent in using ‘ethnic’ or ‘civic’ conceptions of the people. Moreover, in many languages, the concept of ‘the people’ has a clear ethnic connotation. This could hinder individual‐level measurement of populism as a thin‐centred ideology.

Using a wording experiment, we, therefore, examined whether German respondents presented with an ethnic framing of ‘the people’ (das Volk) answered key populist attitude items differently than respondents who received an ethnic framing of ‘the people’ as citizens (Bürger).

We find that the measurement invariance assumption does not hold: Using different wordings does not lead to equivalent measures. Moreover, there are statistically significant differences between the two wordings. We only varied the ethnic and civic conceptions for two items. This is likely to be more consequential in survey batteries that predominantly include items which contrast ‘the people’ with elites to measure populist attitudes (for an overview of different batteries, see Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). The populist attitude scales proposed by Schulz et al. (Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2018) and Stanley (Reference Stanley2011), for instance, contain references to ‘the people’ in 7/9 and 7/8 of the items, respectively.

While respondents receiving the items with an ethnic conception of the people scored overall higher on the items, their overall score on the populist attitude scale was not higher (shown in OA, pp. A10–A13). The higher levels of agreement with the items displaying an ethnic conception of the people is particularly pronounced for voters of the far right (shown in the left panel of Figure 2) as well as for older voters (shown in OA, pp. A8–A9). The difference between an ethnic and a civic conception of the people in the items was also only significant for respondents who adhered to a moderate to a high level of exclusive national identity (shown in OA, pp. A8–A9). This finding is highly suggestive of the ‘ethnic’ interpretation of ‘the people’ – at least in the German language – thereby conflating populism with nationalism.

Importantly, the degree to which ‘the people’ is understood in denoting a specific ethno‐cultural group likely differs across countries. This type of differential item interpretation might therefore lead to even more measurement invariance when used in cross‐national research (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). In other words, if the ethno‐cultural connotation of the people varies across countries, this may hamper cross‐national applications of populist attitude scales that include multiple items referring to ‘the people’. In fact, in a comparison of different populist attitudes scales Castanho Silva et al. (Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020) find that the scales by Schulz et al. (Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2018) and Stanley (Reference Stanley2011) perform worse than the scale proposed by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014). To empirically establish whether differential interpretations of ‘the people’ matter for measurement invariance, it would be worthwhile replicating this study for different countries. In addition, it would be worthwhile in replicating this analysis for different scales than the Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014) scale.

Crucially, our findings suggest that populist attitude scales that rely on ethnic measures of ‘the people’ might not be entirely appropriate for measuring populism as thin ideology that attaches itself to both inclusive and exclusionary ideologies. While (ethnic) nationalism and populism often go hand in hand, it is important that we keep both concepts analytically distinct, both conceptually and empirically (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017). An ethnic priming of ‘the people’ in the populist attitudes scale makes it more difficult to keep ethnic nationalism and populism distinct.

One could argue theoretically that ‘the people’ captures the meaning of the concept of populism better than ‘citizens’. After all, it populism assumes the people to be a homogeneous entity. Yet, our findings suggest that also a civic framing of the concept yields a satisfactory model fit when estimating a confirmatory factor analysis. In addition, our results suggest that an ethnic framing of the citizens runs the risk of overestimating the degree of populist attitudes among more nativist citizens. To avoid priming respondents with an ethnic conception of the people, future studies should use a consistent ethnic or civic conception of the people when measuring populist attitudes, bearing in mind that the civic conception does lead to higher values on the scale.

What is more, our results suggest that political scientists should be careful when commissioning translations of survey items. While different translations of key concepts may seem equivalent to non‐specialists, our findings show that such nuances can yield measurement invariance – impeding comparison across countries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the four anonymous referees and the EJPR editors for their constructive comments. The paper has really greatly improved from the comments we received. Further, we would like to thank Andrej Zaslove and Philipp Masur for their helpful feedback.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1

Table A.1: Survey Questions ‐ DV

Table A.2: Survey Questions ‐ Demographics

Table A.3: Survey Questions ‐ PreTreatment Questions

Table A.4: Descriptive Information

Figure A.1: Balance Checks

Table A.5: Differences in Ethnic and Civic Conceptions of the People

Table A.6: Average Marginal Effects for Ethnic Conception of the People

Table A.7: Table Results H2b

Figure A.2: Average Marginal Effects for Ethnic Conception of the People

Table A.8: Confirmatory Factor Analysis ‐ Fit Statistics

Table A.9: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table A.10: Measurement Invariance ‐ CFA Models

Figure A.3: CFA Distribution

Table A.11: Addative Scaling Analysis

Figure A.4: Addative Scale Distribution

Table A.12: Wüttke et al. Approach

Figure A.5: Wuttke et al. Approach Distribution

Figure A.6: IRT Distribution (1)

Table A.13: IRT Analysis

Table A.14: Measurement Invariance ‐ IRT Models

Figure A.7: IRT Distribution (1)

Table A.15: Table Results DV: Populist Vote

Table A.16: Table Results DV: AfD Vote

Table A.17: Table Results DV: Left Vote

Table A.18: Table Results DV: Populist Vote

Table A.19: Table Results DV: AfD Vote

Table A.20: Table Results DV: Left Vote