Introduction

There are growing concerns among pundits about the increasing elite ideological polarization due to its potential to push the masses to the extremes (Zingher & Flynn, Reference Zingher and Flynn2018). Are these concerns warranted? Two different yet complementary bodies of literature have approached this question. The first focuses on the ‘follow‐the‐party’ effect, examining whether partisans tend to adopt more polarized positions when their party does so (Lenz, Reference Lenz2013; Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2020). The second explores whether ideological polarization unfolds from the top‐down or the bottom‐up, testing whether polarization at the elite level precedes polarization among the masses or vice versa (Moral & Best, Reference Moral and Best2023; Steenbergen et al., Reference Steenbergen, Edwards and De Vries2007). Despite the persistent interest in these questions, we still lack conclusive evidence on whether party‐level ideological polarization causes mass‐level ideological polarization.

Both strands of the literature predominantly argue that when parties ideologically diverge from each other, partisans will also diverge from each other in terms of their preferences (Abramowitz & Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Garner & Palmer, Reference Garner and Palmer2011; Silva, Reference Silva2018). This phenomenon is explained by the follow‐the‐party effect, which revolves around the concept of group loyalties. Individuals easily develop attachments to groups (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1981), which lead them to see the world in terms of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Once individuals develop a self‐identification with a group, they tend to conform to their groups (Cohen, Reference Cohen2003), engage in motivated reasoning (Bolsen et al., Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014), exhibit positive bias towards their own groups (Otten & Wentura, Reference Otten and Wentura1999) and display negative bias towards other groups (Billig & Tajfel, Reference Billig and Tajfel1973). Given that party identity functions as a social identity (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015, Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018), partisans are inherently more motivated to maintain their identity than their ideological preferences (Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Skov, Serritzlew and Ramsøy2013). This motivation is so strong that they are likened to behaving like football fans (Mason, Reference Mason2015). Consistent with classic theories of opinion formation, individuals tend to resist information that conflicts with their predispositions while absorbing information that aligns (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Consequently, this results in the reinforcement of predispositions, hence polarized opinions if parties diverge. Much empirical evidence shows that partisans typically follow their party, adjusting their own ideological stances to align better with it (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017; Barber & Pope, Reference Barber and Pope2019; Lenz, Reference Lenz2013; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Skov, Serritzlew and Ramsøy2013), even when this contradicts their previous beliefs (Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2020). These findings contradict normative expectations that citizens should select politicians who represent their policy preferences, thus prioritizing their ideological stances (Achen & Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017).

Likewise, research has also focused on the reactions of out‐partisans to the positions of parties they do not support. Evidence suggests a ‘backlash’ effect among identifiers of an ideologically different opposing party, wherein they shift even further away from a party's position when it takes a more extreme stance in general (Feddersen & Adams, Reference Feddersen and Adams2022; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). A similar argument also applies to radical right party entry, which causes backlash among left‐wing voters (Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019). Moreover, the more extreme the perceived position of an opposing group is, the more likely individuals are to position themselves as more extreme in the opposite direction (Ahler, Reference Ahler2014). This likely arises from the fear of potential policy implementations favouring the opposing group and the increased perceived threat regarding the group's political interests (Renström et al., Reference Renström, Bäck and Carroll2021), thereby triggering a backlash effect (Bishin et al., Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2016; Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019). However, the results are inconclusive, as there is also research indicating the absence of such an effect (Guess & Coppock, Reference Guess and Coppock2020).

This research tests two mechanisms of mass ideological polarization: (1) the follow‐the‐party effect and (2) the backlash effect. However, testing these questions is challenging for several reasons. Party stances rarely change, often happening gradually. Such changes might be prompted by anticipating shifts in public opinion. Simultaneously, public opinion could react to party position changes. Due to this endogeneity, scholars have turned to experimental designs to study this dynamic, trading off external validity for internal validity. However, manipulating party positions in experiments might not accurately reflect the real‐world complexities, as participants likely possess prior knowledge of party positions on important issues (Slothuus, Reference Slothuus2016). This ‘pre‐treatment’ could obscure the true impact of party position change. For instance, if respondents have already aligned their preferences with their preferred party or switched their preferred party to better match their own preferences, it could wrongly suggest that the effect is nil, even when it is present. Manipulating party positions to deviate from their actual stances on major issues presents further challenges, as participants might perceive such treatments as unrealistic. One approach to address these issues is using hypothetical parties, albeit at the cost of external validity – neglecting real‐world trade‐offs between ideological commitments and party loyalties. Manipulating positions on lesser‐known issues is another alternative, but this confines interpretations to minor issues where voters might be less inclined to oppose their party's stance. Importantly, as issue preferences and party identification both signal information about each other, manipulating one leads to manipulation of the other, even when the information on the other is provided (Orr et al., Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023), violating the information equivalence assumption in experiments (Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey2018). This leads Orr et al. (Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023, p. 948) to state that ‘scholars will have to find new research designs if they want to convincingly estimate the effects of identity or loyalty independent of policy substance’.

This research note overcomes these limitations by leveraging a sudden real‐world party position change that resulted in polarization. This occurred when the United Kingdom's Labour Party shifted leftward following a leadership change. In this design, I use the unanticipated party position change as a real‐world treatment and compare the pre‐ and post‐ideological preferences of Labour partisans (in‐partisans) and Conservative partisans (out‐partisans). By doing so, I address two questions that relate to both identity and polarization research: First, did Labour partisans adopt a more left‐wing stance when their party moved further to the left? Second, did Conservative partisans backlash by adopting a more right‐wing stance when the opposing party (i.e., the Labour Party) adopted a more extreme ideological position? The findings contribute to two distinct but closely connected bodies of literature: (1) the role of partisan identity in opinion formation (i.e., follow‐the‐party effect) and (2) the role of political parties in polarizing the mass public.

Identification strategy

The British case provides a good opportunity for studying the follow‐the‐party and backlash effects in a context distinct from the American case. Like the United States, the United Kingdom is a stable democracy with two primary competitors: the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. This similarity allows connecting this research's findings to previous findings where follow‐the‐party and polarization research originated. However, the United Kingdom's multiparty system, unlike the United States's two‐party system, introduces diverse elite cues. This distinction allows a comparison to determine whether the latitude parties have in shaping the opinions of their supporters through party loyalty and effective elite cues replicates outside the United States.

After the Labour Party's defeat in the 2015 General Elections, leader Ed Miliband resigned on 8 May, triggering a leadership election held between 14 August and 10 September. Initially, polls among Labour supporters favoured Andy Burnham, while Jeremy Corbyn was the least preferred (Dorey & Denham, Reference Dorey and Denham2016). Corbyn barely secured the 35 nominations required from MPs to enter the race. For instance, the front‐runner, Andy Burnham, supported Corbyn's nomination to symbolically broaden the ideological debate (Dorey & Denham, Reference Dorey and Denham2016). The symbolic support from the MPs is evident as Corbyn received even fewer first preference votes (15) from Labour MPs during the leadership election (Diamond, Reference Diamond2016). Even after he was nominated, Corbyn faced a significant lack of recognition, with many viewing his nomination as a way to ensure a diverse range of perspectives rather than a serious bid for leadership. Therefore, it is clear that Jeremy Corbyn's nomination was not fuelled by Labour supporters' desire for a more left‐wing shift in the party's position or by the Labour Party's attempt to respond to public opinion by shifting their ideology to the left (Online Appendix 1 provides empirical evidence consistent with this interpretation, alleviating concerns about reverse causality). On the contrary, all Labour candidates seeking the leadership agreed that Ed Miliband's left‐wing stance contributed to the party's defeat in the 2015 elections, despite Miliband being more moderate than Corbyn (Dorey & Denham, Reference Dorey and Denham2016). However, once nominated, despite his initial lack of support, Corbyn, with his far‐left position and narrative against injustice, gradually mobilized a significant base, leading to a drastic increase in Labour membership (Whiteley et al., Reference Whiteley, Poletti, Webb and Bale2019). The Labour Party's leadership election reforms, which replaced the previous electoral college system with a one‐member‐one‐vote system, extended the voting to registered supporters in addition to party members. Corbyn's success was particularly notable among newly registered supporters, 84 per cent of whom backed him. In contrast, he received 49.6 per cent support from the full members (Diamond, Reference Diamond2016). Therefore, a procedural nomination was followed by Corbyn's ability to mobilize new members and persuade old members, which played a crucial role in his election receiving 59.5 per cent of the votes.

As Corbyn's nomination was unexpected and not driven by public opinion, the leftward shift in the Labour Party's position once Corbyn was elected is a unique opportunity to test whether Labour partisans followed their party. Similarly, the Conservative Party's leader and the then prime minister, David Cameron, reacted to Corbyn's election by saying that ‘The Labour Party is now a threat to our national security, our economic security and your family's Security’, providing a good opportunity to test the backlash effect among the Conservative identifiers (Stone, Reference Stone2015).

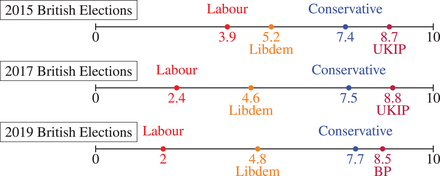

With Jeremy Corbyn's leadership, the Labour Party underwent a rapid leftward shift, resulting in a sudden increase in party polarization in the United Kingdom. As shown in Figure 1, British Election Study experts consistently positioned the Conservative Party and the UK Independence Party (UKIP) similarly across three elections, indicating that parties became more dispersed on the ideological spectrum (i.e., increased party polarization) due to the Labour Party's leftward shift.Footnote 1 Specifically, it shifted its position from 3.9 in 2015 (pre‐Corbyn) to 2.4 in 2017 (post‐Corbyn, 2 years) and to 2.0 in 2019 (post‐Corbyn, 4 years).

Figure 1. Party positions according to British Election Study Expert Survey.

Figure 2 shows that this trend is also perceived by citizens (see Online Appendix 2 for perceptions by partisan groups and question wordings). They perceived the Labour Party shifting from 3.2 in 2015 (wave 6, pre‐Corbyn) to 2.6 immediately after Corbyn's arrival in 2016 (wave 7), 2.2 in 2017 (wave 12) and 1.7 in 2019 (wave 18). This confirms that under Corbyn's leadership, Labour shifted its policy to the far left, and voters recognized this shift. Citizens clearly use party leaders as cues to form perceptions of party positions (Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2017) as also seen when they quickly updated their perceptions of the Labour Party's position after Jeremy Corbyn was replaced by the more moderate Keir Starmer. Moreover, perceived position of other parties closely aligns with expert perceptions, indicating that the increased elite polarization in the United Kingdom was caused by the Labour Party's rapid leftward shift, providing a unique case to test both the ‘follow‐the‐party’ and ‘backlash’ effects in real‐world politics.

Figure 2. Average perceived position of Labour Party's according to respondents.

Note: British Election Study Internet Panel data.

Using panel data from the British Election Study Internet Panel 2014–2023, I compare the left‐right positions of both groups before and after the Labour Party's leftward shift. The dependent variable is the change in left‐right self‐placement between wave 6 (conducted in May 2015) and wave 7 (the first wave post‐change, conducted in April/May 2016). Negative (or positive) values indicate shifts to the left (or right). I regress this shift on partisanship as measured in wave 6, prior to the position change and Jeremy Corbyn's nomination.Footnote 2 Independents serve as the counterfactual group, as they lack party identification and are neither expected to follow nor backlash against the Labour Party's position change.Footnote 3 While acknowledging the potential influence of other political developments between these waves, the absence of an election campaign during this period suggests that any changes in how voters and experts perceive the Labour Party's position are plausibly, though not solely, driven by the position change and clarification following the leadership change.

Results

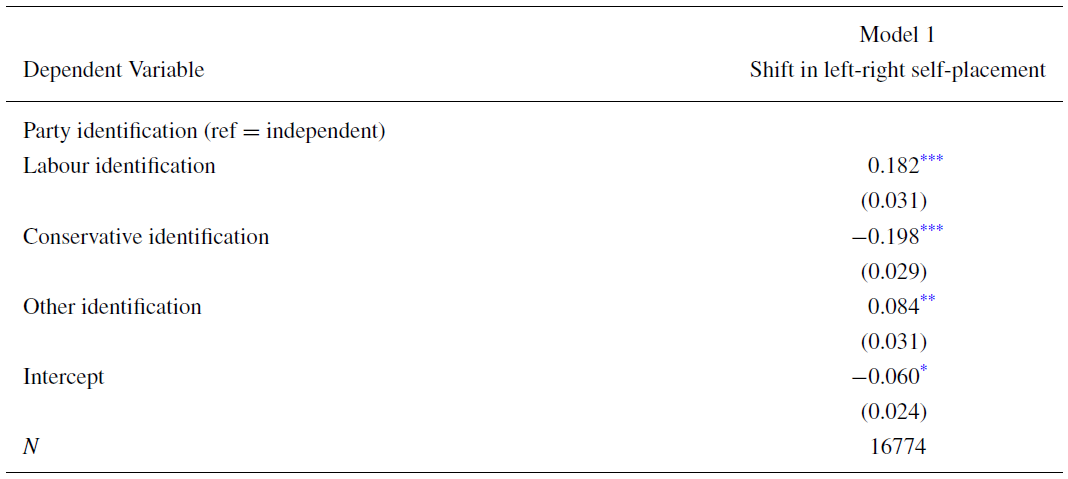

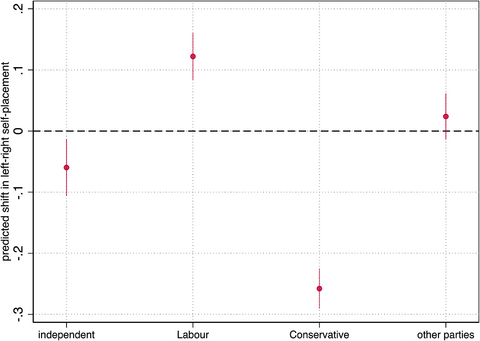

Table 1 presents the findings from an ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation with robust standard errors to test the follow‐the‐party and backlash effects. The positive coefficient for Labour identification indicates that Labour identifiers, compared to independents, became slightly more right‐wing by 0.18 points. On the other hand, the negative coefficient for Conservative identification indicates that Conservative identifiers, compared to independents, became more left‐wing by 0.20 points. Figure 3 visualizes the average predicted shift for each partisan group. The intercept (−0.060) in Model 1 suggests that independents slightly became more left‐wing, though this shift is not a substantial one. While Labour identifiers moved to the right, Conservative identifiers moved to the left, and identifiers of other parties did not shift their ideological stance. These findings do not support the follow‐the‐party effect among Labour partisans or the backlash effect among Conservative partisans.Footnote 4 In other words, partisans did not polarize by following Labour's leftward shift nor did out‐partisans adopt more extreme positions in the opposite direction.Footnote 5 The lack of evidence for these two mechanisms of polarization suggests that mass polarization did not follow elite polarization.Footnote 6

Table 1. Lack of follow‐the‐party and backlash effects among partisans

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

*

![]() $p<0.05$, **

$p<0.05$, **

![]() $p<0.01$, ***

$p<0.01$, ***

![]() $p<0.001$.

$p<0.001$.

Figure 3. Lack of follow‐the‐party and backlash effects among partisans.

Note: OLS regression model with robust standard errors is estimated. The dependent variable is the shift in left‐right placement between wave 6 and wave 7.

To ensure that the effect is not merely a lagged reaction and truly nil, I now examine over‐time trends. However, it is important to acknowledge that when analysing these trends, shifts in self‐placement among partisans and their perceptions of their party's ideological stance might be influenced by factors beyond just the leadership change. For instance, over the course of 6 years, other significant developments, such as the 2016 referendum on whether to remain or leave the European Union and subsequent discussions on how to exit, became important factors. Therefore, it is important to note that the main focus of this research note is on the immediate effects and that one should approach the over‐time analyses below with caution and interpret them within the context of potential lagged effects.Footnote 7

During the 2017 elections, the Labour Party's clearly more left‐wing manifesto resonated strongly with voters, resulting in a significant increase in its vote share by around 10 percentage points. Hence, when partisan cues were stronger Labour partisans may have adopted a more left‐wing stance, while Conservative partisans might have reacted with a backlash during the first general elections under Jeremy Corbyn. To explore potential lagged effects, I estimate auto‐regressive OLS panel data analysis, which controls for observed or unobserved time‐invariant confounders by estimating within‐individual effects.

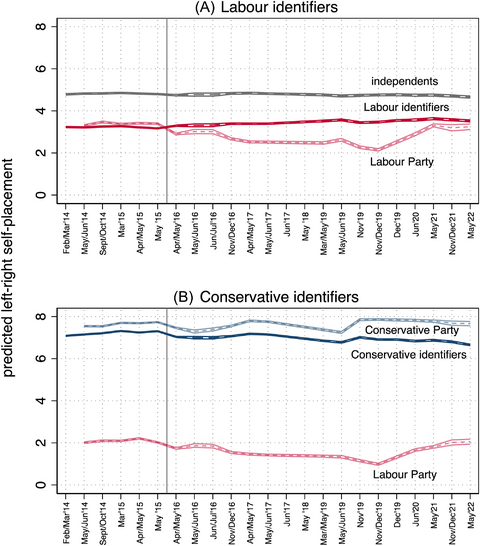

Figure 4 presents the average within‐individual effects among partisan groups and their perceptions of the Labour Party's ideological stance.Footnote 8 The figure includes two panels: (a) trends among Labour identifiers and (b) trends among Conservative identifiers. Panel a plots the evolution of average ideological positions among independents (grey) and Labour Party identifiers (dark red), along with how Labour identifiers perceive the party's position (light red) before and after the leadership change (vertical line). Party identification is held constant at wave 6 (pre‐Corbyn) because the objective is to examine how individuals already identifying with a party react when the Labour Party adopted a more left‐wing position.

Figure 4. Labour partisans do not follow the party and conservative partisans do not backlash.

Note: Predictions are from panel data OLS regression with individual fixed effects. See Online Appendix 2 for question wordings. Detailed descriptions of each panel are provided in the text.

In the short term, Labour identifiers perceived a 0.5‐point leftward shift in the party's position between wave 6 (May 2015) and wave 7 (April/May 2016). However, they did not adopt a more left‐wing shift themselves. If anything, Labour partisans became less left‐wing by 0.13 points right after the leadership change, consistent with Model 1 in Table 1.

In the long term, Labour partisans increasingly perceived the party as more left‐wing from wave 6 onwards. Despite this, they continued to moderate their own ideological stance, widening the gap between themselves and the Labour Party. For instance, their average position was 3.16 in wave 6 (just before the position change), which shifted to 3.29 in wave 7, 3.39 during the 2017 General Elections (wave 12), and 3.46 during the 2019 General Elections (wave 18).Footnote 9 Meanwhile, independents (based on identification in wave 6) remained stable over time.

The key takeaway from panel a is that although Labour identifiers perceived the party as shifting continuously to the left, they themselves did not follow suit by becoming more left‐wing. As partisans typically perceive their party as closer to their own position (i.e., projection bias), the absence of a follow‐the‐party effect is particularly convincing, especially as the gap between their own stance and their perception of the party's position widened over time.

Panel b in Figure 4 focuses on Conservative identifiers (dark blue) based on their wave 6 identification, showing their perceptions of both the Conservative Party's position (light blue) and the Labour Party's position (light red). In the short term, immediately after the position change, Conservative partisans shifted slightly leftward by 0.26 points, even though they perceived the Labour Party to have shifted to the left by 0.28 points. Interestingly, despite no actual change in the Conservative Party's position according to experts, Conservative identifiers perceived their party as having moved to the left by 0.27 points. This points to a lack of evidence for a backlash effect, as Conservative identifiers did not move further right in response to Labour's shift.

In the long term, there was no backlash effect among Conservatives. Like Labour partisans, Conservative partisans also moved slightly towards the centre over time. Although Conservatives perceived their party to have moved to the left, this interpretation requires caution, as perceptions of party position and one's own ideological position can be endogenous. It is possible that Conservative identifiers aligned their perceptions of their party's position with their new ideological stance (i.e., projection bias). Regardless of interpretation, these results clearly indicate an absence of backlash: Conservative partisans did not move to the right when the Labour Party moved to the left.

Effective party cues for the ideologically out‐of‐touch partisans

Does the lack of a follow‐the‐party effect mean that the Labour Party could not cue its supporters? To explore this, I test whether the party could cue those who were out of sync with its ideological position. If partisanship is a social identity, partisans are biased reasoners that are motivated to maintain their identity over ideology. When their party shifts away from them, this creates cognitive dissonance, leading to motivated reasoning to rationalize the party (Kunda, Reference Kunda1990; Leeper & Slothuus, Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014; Matz & Wood, Reference Matz and Wood2005; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Skov, Serritzlew and Ramsøy2013). This dissonance, strongest among those furthest from the party, may drive them to seek consonance and group similarity by shifting left (see Online Appendix 10 for detailed theoretical elaboration). Therefore, whether partisans follow the party might be contingent on how far away they become with the party when the latter moves further to the left.

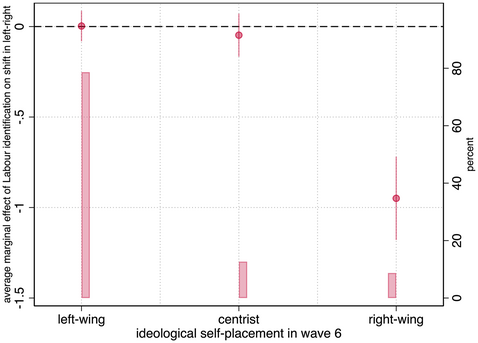

I focus on left‐wing, centrist and right‐wing Labour identifiers (based on their pre‐shift positions) to explore their reactions to the Labour Party's leftward shift.Footnote 10 Figure 5 shows that right‐wing Labour partisans adjusted their positions to be more left‐wing compared to independents.Footnote 11 This suggests that the Labour Party could cue its partisans who were initially out of touch with the party by providing left‐wing cues. However, it did not lead those already aligned with the party's position to adopt more extreme ideological stances.

Figure 5. Previously right‐wing labour partisans followed the party's lead to the left.

Note: OLS regression model with robust standard errors is estimated (see Online Appendix 10 for regression outputs). The dependent variable is the shift in left‐right placement between wave 6 and wave 7.

Robustness

Additional checks support these conclusions. Strong Labour partisans did not shift further left (see Online Appendix 12). The absence of a follow‐the‐party effect is evident even among stable Labour partisans who consistently identified with the party in consecutive waves before the position shift (see Online Appendix 13). Additionally, motivation to align their positions with the party is likely higher for those who both identified with the Labour Party prior to Corbyn's election as the leader and remained as Labour partisans in each wave until wave 12 (May/June 2017). Despite this, the follow‐the‐party effect was still absent among these dedicated partisans (see Online Appendix 14).

Despite null results regarding the overall left‐right brand, the follow‐the‐party and backlash effects might still manifest on different political issues or attitudes. For instance, one could argue that the redistribution issue is where it is most likely to observe these effects, given Jeremy Corbyn's clear far‐left stance on the economy. However, results in Online Appendix 15 provide further evidence that there are simply no follow‐the‐party and backlash effects when focused on attitudes towards redistribution, immigration, or European integration.

Could Brexit alignment explain the post‐Brexit moderation among Labour and Conservative partisans? It is possible that Labour identifiers in wave 6 shifted to identify with the now Brexit‐supporting Conservative Party, potentially explaining moderation. Conversely, some wave 6 Conservative identifiers might have distanced themselves from the party due to its Brexit stance and became Labour identifiers (Schonfeld & Winter‐Levy, Reference Schonfeld and Winter‐Levy2021), causing moderation. However, focusing on respondents who maintained their Brexit views from wave 6 (May 2015) to wave 12 (May/June 2017) and consistently identified with the Labour Party before and after the referendum reveals that even these individuals did not adopt a more left‐wing stance (see Online Appendix 16). This suggests that the observed trends are not attributable to adjustments in party identification based on Brexit views.

Research shows that divided parties struggle to lead their electoral base (Ray, Reference Ray2003). Considering that the Labour Party has been perceived as more divided by its partisans since Jeremy Corbyn, they might be less inclined to follow the party's lead. Additional analyses demonstrate that the perceived dividedness of the party does not influence this effect (see Online Appendix 17). In other words, even Labour identifiers who perceived the party as unified did not follow its lead.

One might argue that Corbyn's lack of popularity or his perceived deviation from his party's values could explain the absence of a follow‐the‐party effect. However, analyses counter these arguments (see Online Appendix 18). Despite perceiving Corbyn as more left‐wing than the Labour Party, partisans noticed a significant leftward shift in the party's position, suggesting the leftward shift was broader than just Corbyn's personal ideological commitments. Moreover, while warmer feelings towards Corbyn only slightly mitigated the moderation effect among Labour partisans, they did not lead to a more left‐wing alignment. This suggests that the lack of a follow‐the‐party effect cannot be explained by Labour partisans not liking Jeremy Corbyn. Interestingly, Conservative identifiers who felt positively towards Corbyn or the Labour Party became less right‐wing, suggesting the effectiveness of partisan cues for out‐partisans.

Lastly, Corbyn's left‐wing position could resonate more among younger voters. However, even among young Labour identifiers, there was no noticeable adoption of more left‐wing positions (see Online Appendix 19).

Discussion

The findings of this study address a prevalent question among political scientists: When leaders with an extreme policy agenda assume leadership positions in mainstream parties, can they polarize the ideological preferences of the masses? Contrary to conventional wisdom, the results do not support the expectation that both in‐partisans and out‐partisans would adopt more extreme positions in opposite directions. Instead, both groups tended to moderate their ideological stances, which contradicts the ‘follow‐the‐party’ and ‘backlash’ effects.Footnote 12 Only ideologically inconsistent partisans (i.e., right‐wing Labour partisans) showed a tendency to align with the party's new position once it was clarified. That is, partisans do not blindly become more polarized just because their party embraces more extreme ideologies.

These findings do not contradict previous works demonstrating that British citizens use party cues to form their opinions (Brader & Tucker, Reference Brader and Tucker2012). Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Green and Milazzo2012) found that when parties ideologically converged, they successfully cued citizens, resulting in a less ideologically sorted electorate. This research note reveals that the Labour Party's new position served as a cue for right‐wing Labour partisans, leading them to adopt more left‐wing stances. However, those already in sync with the party did not further polarize. This suggests that public responses to cues from polarizing elites follow a spatial logic. This finding is consistent with evidence from Denmark, where party position change led partisans, especially those whose preferences were the most inconsistent with the party's new position, to follow the party's new stance (Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021).

Overall, in joining the findings of Slothuus (Reference Slothuus2010), these results depict a portrait of critical partisans who do not blindly follow their party's lead. This challenges the idea that the masses are destined to polarize if political parties themselves polarize. This image of critical partisanship underscores that parties have limited influence in shaping the preferences of their base. These findings align well with Schonfeld and Winter‐Levy (Reference Schonfeld and Winter‐Levy2021), who showed that when the Conservative Party, despite having campaigned to remain in the European Union, shifted to support Brexit after the referendum, pro‐European Conservative identifiers were more likely to leave the party instead of changing their views on Europe. However, new Conservative identifiers adjusted their opinions on redistribution to better align with the Conservative Party.

The results of this research note speak to the ongoing debate on the role of party loyalties in the United Kingdom in comparison to that in the United States. On the one hand, Goren (Reference Goren2005) finds that partisan attachments in the United States are even more stable than core values, which themselves are generally more stable than issue positions. This suggests that party identification in the United States causes changes in values without being influenced by them. These findings support the original conceptualization of party identification by Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980) that it is an unmoved mover that is exogenous to issue positions and core values, hence providing a ‘perceptual screen’ for interpreting political matters. As summarized by Green et al. (Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004, 4), ‘When people feel a sense of belonging to a given social group, they absorb the doctrinal positions that the group advocates’. On the other hand, measuring party identification as a social identity through various items in four multiparty contexts (United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden), Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018) find that it is rather strong partisans in the United Kingdom who act like partisans in the United States in that they prioritize their identity over ideology.Footnote 13 Moreover, Evans and Neundorf (Reference Evans and Neundorf2020) find that in the United Kingdom, core values exhibit greater stability than partisan attachments. In contrast to the findings of Goren (Reference Goren2005), core values predominantly influence partisanship rather than the other way around. The findings of this research suggest that in the United Kingdom, party identification offers parties less influence over shaping partisans' ideological stances, implying that partisanship might not function as an unmoved mover, as traditionally conceptualized.

Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Green and Milazzo2012) find that the British public only slightly followed the Labour and Conservative Parties' gradual moves to the centre whereas Cohen and Cohen (Reference Cohen and Cohen2021) find clearer evidence that mass (de)polarization on redistributive attitudes trends with elite (de)polarization, challenging Evans and Neundorf (Reference Evans and Neundorf2020) who argued that ideology in the United Kingdom is stable. My results offer a slightly different perspective: elite‐level polarization did not immediately lead to mass‐level polarization, either among partisans or non‐partisans. Notably, both Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Green and Milazzo2012) and Cohen and Cohen (Reference Cohen and Cohen2021) examine gradual changes in party polarization and long‐term ideological shifts while this research focuses on a sudden change in party polarization and the immediate shifts in mass ideological polarization, minimizing the endogeneity issue discussed earlier. The sudden change in one party's position also allowed for testing both follow‐the‐party and backlash effects. Despite these differences, a common finding is that partisanship does not appear to drive changes in ideological trends, as Cohen and Cohen (Reference Cohen and Cohen2021) find that the (de)polarization trends are not driven by partisans becoming (de)polarized but apply more broadly to the citizenry.

These results also imply that party identifiers update their beliefs not only based on information from their own party but also from the opposing party (Coppock, Reference Coppock2023; Fowler & Howell, Reference Fowler and Howell2023). Following a leadership change, media coverage significantly increases, especially if it results in a shift in the party's ideological position. This exposes citizens to new information about the party, originating not only from the party itself but also from political commentators and elites of other parties, who comment on the opposing party's new position. Consequently, partisans may respond to information from the out‐party as well, suggesting that persuasion, rather than polarization, might occur when exposed to countervailing information (Coppock, Reference Coppock2023). Consistently, results show that Conservative partisans who felt warmly towards Corbyn or the Labour Party moved in the direction of the out‐party cue, indicating that partisan cues are still useful for citizens despite their limited influence.

Lastly, while leadership changes influence party perceptions, factors like interactions with other parties, shifts in the political agenda and media coverage might also play a role. Given the 1‐year gap between waves 6 and 7, other political developments might have influenced perceptions of the Labour Party's position as well. Future studies should better isolate leadership effects by using panel data with shorter intervals or a rolling cross‐sectional survey, minimizing potential confounders and providing a clearer understanding of leadership effects on perceptions.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ruth Dassonneville, Zeynep Somer‐Topcu, Jean‐François Godbout, Markus Wagner, Jane Green, Matthew Levendusky, Alexandra Jabbour, Vincent Arel‐Bundock, Philippe Mongrain, André Blais, Romain Lachat, Wayde Z. C. Marsh, Giorgio Malet, Patrick Fournier and Frédérick Bastien for their comments and suggestions throughout the development of this paper. I am also grateful to the panel participants at the American Political Science Association and European Political Science Association. The research was supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Société et culture (grant: 307597) and the European Research Council (grant: 101044069). I also thank the editors of EJPR and their three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Data availability and replication

All replication data and syntax are publicly available in the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/10FMMW

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 1.1. No Noticeable Shift among Labour Identifiers Prior to Leadership Change

Figure 2.1. Distribution of Perceived Shift among Labour Identifiers

Figure 2.2. Distribution of Perceived Shift among Independents

Figure 2.3. Distribution of Perceived Shift among other Identifiers

Table 2.1. Who perceived the shift?

Figure 2.4. Who perceived the leftward shift of the Labour Party?

Table 3.1. Descriptive statistics for wave 6 and wave 7

Table 4.1. Lack of Follow‐the‐Party and Backlash Effects among Partisans

Table 5.1. Lack of Follow‐the‐Party and Backlash Effects despite being aware of the shift

Table 6.1. Liberal Democrats and UKIP Identifiers do not Backlash

Figure 7.1. Change in Distribution in Left‐Right Self‐Placement

Figure 9.1. Over‐time patterns among respondents who took the first 12 waves

Figure 9.2. Over‐time patterns among respondents who took the all of the 20 waves

Table 9.1. Table of descriptives ‐ unlimited sample

Table 9.2. Table of descriptives all first 12 wave‐takers

Table 9.3. Table of descriptives all 20 wave‐takers

Figure 10.1. Labour Party's Shift to Left and Conditionality of Party Effect

Table 10.1. Right‐wing Labour partisans become less right‐wing

Table 11.1. Out of sync Labour partisans moved to the left

Figure 11.1. Out of sync Labour partisans moved to the left

Table 12.1. Did Strong Labour Partisans Follow the Party?

Figure 12.1. Did Labour Partisans Follow the Party (by partisanship strength)?

Figure 12.2. Evolution of left‐right placement among weak and strong Labour identifiers

Table 13.1. Consistent Labour partisans did not follow the party

Figure 13.1. Results by consistent Labour identifiers

Table 14.1. Consistent Labour partisans did not follow the party

Figure 14.1. Results among consistent Labour identifiers

Figure 14.2. Results among consistent Labour identifiers

Table 15.1. Lack of Follow‐the‐Party and Backlash Effects on Different Dimensions of Conflict

Figure 16.1. Evolution of left‐right placement among consistent Labour identifiers who maintained their Brexit views

Table 17.1. Perceptions of how Unified/Divided the Labour Party do not explain the observed findings

Figure 17.1. Labour Partisans who Saw the Party as United did not Follow the Party

Table 18.1. Perceived left‐right position of the Labour Party and Jeremy Corbyn (by Labour partisans)

Table 18.2. Do feelings towards the Labour Party and Jeremy Corbyn influence how masses react to party cues?

Table 19.1. Did young people follow the Labour Party's leftward shift?