City Academies and Academic History Paintings

The rise of history painting in Europe is intimately linked to the rise of academic art itself. Art academies had originated towards the end of the Middle Ages at city level, emerging from the guild system of the medieval municipalities and the private studios (workshops, ateliers) of recognized masters with their trainees. This atelier tradition persisted into modern times in osmosis with municipal art schools, where the master would often also teach and which would host exhibitions and broker commissions. Even in the nineteenth century, we see that travelling art students would seek their training at institutional academies surrounded by private studios. A European model of ‘official’ training establishments evolved in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The prototypes were in Renaissance Italy: Florence (1563), Perugia (1573) and, most importantly, Rome (1593). In 1648, the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was founded in Paris, later to become the Académie des beaux-arts; subsequent foundations were usually in metropolitan centres with strong ties to court life.Footnote *

In and between these academies, and in the wake of the Italian Renaissance and the baroque, a ‘classicist’ repertoire and set of techniques crystallized and converged into a pan-European style. The technique stressed lifelike verisimilitude, a finesse of unobtrusive brushstrokes and a mastery of perspective and anatomy. These were studied and applied in a set of genres that became standardized and were classified in a hierarchy of status. History painting counted as the most prestigious of all artistic genres, above the portrait, landscape or still life. History paintings were usually in the high, heroic or ‘sublime’ mode, ambitious in topic and on a large canvas, often involving complex, dramatic scenarios (battles, crisis moments known from classical or biblical literature) in settings that also required a mastery of anatomy, perspective, landscape and architectural design. The topics were taken from a repertoire that was strictly circumscribed by the horizons of ancient Greece, ancient Rome and the Bible. No distinction was made between fictional or historical themes: scenes from the Iliad or Euripides were mixed with those from Greek mythology and the Roman historians. Classical as it was, the repertoire was also timeless (ironic for something called ‘history painting’), much like the commemorative statues, paintings and sepulchral monuments of saints, princes and prelates in churches.1

Besides being transhistorically timeless, the classicist repertoire was also transnational. Biblical and classical antiquity, the stories of Troy, Jerusalem, Athens and Rome (even including outriders such as Babylon and Carthage), were considered to be the shared heritage of all of modern Europe. Any localization was mostly at the level of court or metropolis. The equestrian statues of the condottieri Gattamelata and Bartolomeo Colleoni in Padua and Venice (mid-to-late fifteenth century) are modelled on the classical prototype statue of Marcus Aurelius (c. 175 AD), but they specifically honour champions of Italian city republics, Venice in particular. The seventeenth-century statue of Erasmus belongs to Rotterdam; Jeanne d’Arc was commemorated in the public spaces of Orléans and Rouen, the diocesan cities of her triumph and martyrdom, long before she became a nationally French saint.

This biblical/classical thematic repertoire never really went away. It remained prominent within history painting for as long as that genre endured, right up to the time of Lawrence Alma-Tadema; but it was overlaid by an additional repertoire: themes taken from medieval and early modern European history. Those themes, dealing with the period when the European state system crystallized out of its feudal antecedents, were usually known as ‘national’ as opposed to ‘classical’.

The style of these paintings remained in the ‘academic’ mode, largely impervious to the great nineteenth-century artistic transitions of plein-air painting, realism and the avant-garde -isms. Conventional as they were, these history paintings tend to be overlooked or marginalized in those art histories that focus on the emergence of new modes of expression and on the search for originality and individualism. The style of late (Romantic) academicism has long been decried as kitsch, ‘salon art’ or art pompier, reflecting at best the century’s bourgeois complacency and anxieties. A point of critical attention has traditionally been the genre’s voyeuristic obsession with female nudity in ‘respectable’ (allegorical, orientalist, mythological or historical) contexts.2

From Classical to National: History and Imagination

In the course of the eighteenth century ‘classical antiquity’ was increasingly turned into ‘ancient history’. It was seen not as the timeless foundation of civilization but as a period in human affairs with its historical dynamics of conflict and resolution, growth and decline (as per Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1776–1789), and as a period in which visual evidence, often archaeologically retrieved (e.g. at Pompeii and in the Roman catacombs), provided welcome documentation to complement written sources. Indeed, as Francis Haskell has argued, the visual reproduction of archaeological material evidence about life in ancient times (coins, vases, statuary) provided a strong incentive to render the imagination of those distant periods itself a visual one, and one that could be evoked by visual means. In this shift, history painting developed into a representation of past events, rather than a ‘classical’ exemplum of timeless relevance. Ancient manners and events were depicted, visualizing what things must have been like – a stimulus to the viewer’s historical imagination. This budding historicism was accompanied, from the late eighteenth century onwards, by a turn towards the vernacular past: themes were increasingly chosen from the post-classical history of the European nations. The Death of General Wolfe (1770) by Benjamin West, a glorification of the conqueror of Quebec expiring on the battlefield in 1759, is usually considered a turning point in the thematization of the national as opposed to the universal (classical or biblical) past.3

Another nationalizing trend was set in motion by dynastic and literary antiquarianism: monarchs would have their palaces adorned with portraits and acts of their forefathers, which in the cases of Britain and France might lead into the medieval and semi-legendary territory (Merovingian, Anglo-Saxon) that would subsequently be claimed for ‘national’ history.4 Tellingly, the Romantic ‘Nazarenes’ (on whom more in what follows) found employment in adding historically reimagined portraits to the gallery of medieval and later emperors in the Kaisersaal in Frankfurt’s Römer buildings. Visual and textual antiquarianism went hand in hand. Portraits (usually fanciful) of medieval kings and queens adorned, as woodcuttings, the pages of treatises by antiquarians such as Jean-Baptise de La Curne de Saint-Palaye; illustrations of ancient bards and Nordic heroes began to proliferate in the wake of Macpherson and his contemporaries. The Swiss–English painter Henry Fuseli depicted scenes from the Nibelungenlied, which had recently been re-edited. Again, the line between historical veracity and legendary fable was not easily drawn in these decades when historical source criticism was still in its infancy and the mythologies narrated by Suhm and Macpherson were often taken as historical fact.

By contrast, in the revolution-inspired works of Jacques-Louis David classical themes were used to allegorize and inspire contemporary, national affairs, holding up ancient Greek or Roman heroes such as Leonidas or the Horatii as models for the republican virtues of contemporary France. Thus national history could, even in the Romantic century, hark back to classical symbols. The tribal opponents who had resisted Roman expansionism in the first or second centuries AD, mentioned by Roman historians such as Tacitus or Livy, now became national heroes defending an independence understood, anachronistically, in terms of contemporary nation-building. Arminius the Cheruscan became a German inspiration, Vercingetorix a French one, and Boudicca an English one.

With the Parisian Academy of Fine Arts as an obvious starting ground, an increasingly recognizable, clearly characterized genre of national history paintings spread across Europe in the course of the nineteenth century by means of the tight, professional system of masters and pupils that formed the art world. David, his pupils Antoine-Jean Gros and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and their pupils and pupils’ pupils such as Paul Delaroche and Jean-Léon Gérôme, among them span the entire century (David died in 1825 and Gérôme in 1904) and fixed an iconography of sublime evocations of key moments in the nation’s history. Their topics included court scenes, deathbed scenes, battle scenes and a number of genre scenes showing great historical figures (frequently other painters: Dürer, Leonardo) in domestic situations. At the same time, this choice canonized such national moments as being suitable for even the most prestigious of artistic expressions. Although the choice and treatment of topics is often Romantic (evoking the Walter-Scott-style couleur locale of the past and the pathos of history), the style is that of high, classical academicism: ambitiously striving for technically convincing verisimilitude through the mastery of brush technique, perspective, textures, human anatomy and physiognomy, and historical detail, often on a large canvas.5

The shared technique of academicism helps to explain the pan-European spread of history painting. Not only could artists from many countries assemble around masters in European ‘hubs’ such as Paris; the paintings themselves were also mobile. The exhibition of two prominent painters from the Antwerp historicist school, Édouard de Biefve and Louis Gallait, in nine German cities between 1842 and 1844 famously inspired a new departure for history painting in many parts of Germany, notably Bavaria. But usually it is the personal network, the filiations of masters to pupils, often through the hub of an internationally renowned academy, that adds up to a quasi-genealogical conduit carrying the spread of history painting across Europe. Even from remote countries with a modest local art scene, promising young artists would be sent (often thanks to sponsorship from wealthy, public-minded patrons) to train at academies and return to introduce the fruit of their training in their own countries: Theodor Aman was given funds by his Romanian patrons to travel to Paris, Norwegian painters such as Peter Nicolai Arbo trained in Düsseldorf, and Munich became the preferred training ground for aspiring painters from the Bohemian lands. All of them celebrated their own countries and their unique authenticity, be it in historical scenes (Aman), Nordic mythology (Arbo) or legend-infused landscapes (the Czechs); all of them did so in the universally current techniques and conventions of academicism.6

The Nazarenes and the Mural

In this Europe-wide urban-academic network, Paris remained, despite all the French regime changes between 1789 and 1871, a pre-eminent node for the academic depiction of national history, with in its wake the academies of Berlin, St Petersburg, Vienna, Antwerp and Düsseldorf. But special mention should be made, alongside Paris, of Rome as a central hub and hatching ground. Not only was the Papal Academy located there amidst the continuity from classical antiquity into Renaissance and baroque, but also various ateliers were set up in Rome by artists from different countries as meeting-grounds for their fellow countrymen, foreshadowing the rise of ‘national’ art institutes in that European metropolis. A sojourn in Rome (often facilitated by a Prix de Rome or a patronage scholarship) counted as the culmination of an artist’s training and helped consolidate the city’s function as a hub. Among these private ateliers and points of artistic congregation, none proved more influential than that of the German Nazarenes.7

A number of Romantically minded young painters found themselves excluded from the rolls of the Vienna academy in that city’s Napoleon-inflicted decline after 1805. They decided to take up residence in Rome, now annexed by Napoleon, where they could make use of a recently secularized Franciscan monastery. Their nationally German hairstyles (long and parted in the middle, à la Dürer, in a rejection of the powdered wig; see Figure 4.4) earned them the nickname of ‘Nazarenes’. In their residence at the San Isidoro church and monastery they lived amidst specimens of the ancient, now languishing, art of the fresco. It appealed to their religious earnestness, their cultural nostalgia and their anti-classicism. The fresco, with its bold colours and clear outlines, sidestepped the jejune artistic opposition between disegno and colorito and allowed them to express their spiritualism and their sympathy with late medieval and early Renaissance forms.

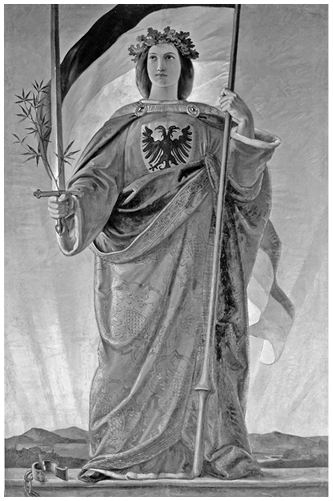

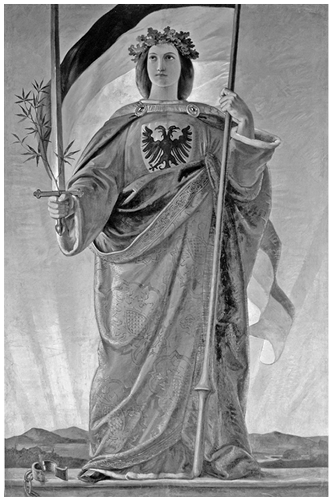

The Nazarenes obtained commissions to decorate Roman villas with frescos and gained lasting, Europe-wide influence. Their clearly outlined and brightly coloured style became the hallmark of the new, Romantic-historicist mural, which was institutionalized when their leader Peter von Cornelius was appointed to head the academy of Düsseldorf and then that of Munich. Düsseldorf and Munich as training grounds helped established the Nazarene mode as a standard for a great number of Romantic-academic painters of the period and the mural as a flagship genre. In Frankfurt’s Paulskirche, the deliberations of the 1848 National Assembly were overlooked by a large allegory of Germania (Figure 8.1) by the Nazarene Philipp Veit; she was depicted as an oak-wreathed female, foot-shackles undone, displaying on her robe the imperial escutcheon of the double-headed eagle and holding a sword and the national tricolour flag of 1813–1814.8

Figure 8.1 Allegory of Germania

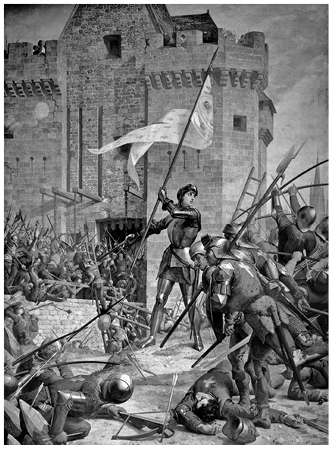

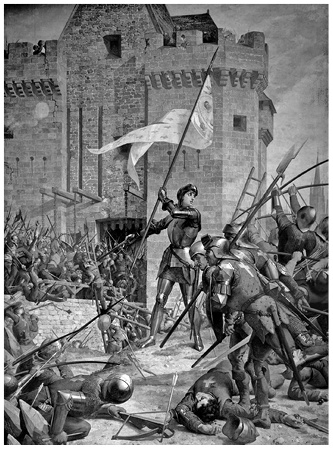

Throughout the century, many prestigious commissions were for mural decorations of restored or newly built palaces and government buildings everywhere in Europe, with Germany as ‘ground zero’. This in turn helped consolidate the Nazarene, Romantic style in academicism: from Maclise’s murals for the new Houses of Parliament in London to Jules Lenepveu’s Joan of Arc cycle in the Parisian Panthéon (Figure 8.2); from Henri Leys’s historical murals for the Antwerp City Hall to Ford Madox Brown’s Pre-Raphaelite celebrations of craftsmanship and labour for the Manchester Town Hall. Within Germany, there are the sumptuous murals at Wartburg Castle, the city hall of Aachen, Munich’s city hall and Neue Pinakothek, and the Imperial Manor at Goslar (more on which further on). As a result of such lavish, large-scale decoration, public buildings became an immersive experience, a time capsule where the visitor would be transported back to the settings, scenery and narratives of bygone ages – a form of mental time-travel that is the essence of historicism. Among them, these murals captured a selected iconography of historical episodes and helped canonize those episodes as historical myths.9

Figure 8.2 Joan of Arc in Armour at the Siege of Orléans (Jules Lenepveu, 1874; Panthéon, Paris).

The grandiose style of history paintings was also used for prestigious topical affairs. Napoleon, and many nineteenth-century rulers after him, commissioned paintings of their coronations and of battles scenes from recent victories; these were done in the grand manner of the history painting and in the process propagandistically asserted the claim that ‘history was being made’ and that these coronations or battles were of lasting historical importance.10 The nineteenth century produced a welter of battle scenes, some depicting events as long ago as the first-century battle of the Teutoburg Forest, others as recent as the Crimean War or the scramble for Africa (e.g. Marià Fortuny’s The Battle of Wad-Rass, 1868). Academic history painters would become the recorders of their country’s old and recent glories. Sixty-five years after David painted Napoleon’s 1806 self-coronation ‘from life’ (having been invited to the occasion for the purpose), Anton von Werner was summoned to Versailles to witness the German imperial proclamation there in 1871, which he proceeded to depict in no fewer than three copies.

Those were state-sanctioned applications. More subversively, Eugène Delacroix painted his famous Liberty Leading the People only months after the 1830 revolution that it celebrates. The ‘history’ in such history painting is often of very recent vintage and signified ‘importance’ rather than ‘pastness’. At the same time the nationalizing tendency is all-pervasive. The nation becomes the dominant frame for calibrating such general notions as historical importance, glory and liberty: it is always the nation’s experience of history, the nation’s glory and its liberty that are celebrated or extolled, with religion running a distant second. The Romantic-historicist preoccupation with early Christianity spawned a great number of history paintings evoking scenes of Christian martyrdom in Roman arenas. And there was, of course, a good deal of inter-nation solidarity, especially regarding the Greek and Polish struggles for national independence: Delacroix was a prominent philhellene, and many of his paintings denounced Ottoman tyranny.11

As Delacroix and his philhellenic paintings indicate, the turn to nationality could go in tandem with an altogether different taste for colourful exoticism: that of orientalism. Almost every painter of history paintings also tried his hand at odalisques, harems or bazaars. The tight conjunction between exoticism and historicism is not fortuitous: both are, in true Romantic fashion, attempts to render a world other than the straightforward here and now. In addition, a nationalist undercurrent is noticeable in both: while historicism bolsters the nation’s rootedness in the past, exoticism often bespeaks colonial ambitions, rooted as it was in Mediterranean expeditions from Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign onwards. Maghrebinian scenes by French or Spanish painters are part of the colonial expansionism of both countries in Northern Africa. Orientalism in Russian painting is part of that country’s oriental imperial colonialism in the Caucasus and Central Asia, overtly celebrated in Vasilij Surikov’s huge canvas on the conquest of Siberia (1895, Figure 8.3).12

Figure 8.3 Yermak’s Conquest of Siberia (Vasilij Surikov, 1895; State Russian Museum, St Petersburg).

The Past as a Magic Mountain: Goslar

The history painters of the nineteenth century are overshadowed these days by names such as Monet, Van Gogh, Klimt and Picasso: those who innovated their style away from academicism and historicism. But we should not underestimate the influence of history painters at the time: through official commissions and through the teaching institutions of the visual arts, they were in a position to establish a pictorial canon of key moments and scenes from the nation’s past, often displayed as murals on the walls of public buildings or reproduced as engravings, lithographs or photographs, also in book illustrations. And they were called upon to broadcast the nation’s identity in high-prestige form. A telling example is the murals for the Imperial Manor at Goslar by Hermann Wislicenus. He had been a pupil at the Dresden Academy of the Nazarene Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and, while in Rome, of Peter von Cornelius; and as of 1868 he had taught at the Düsseldorf Academy.13

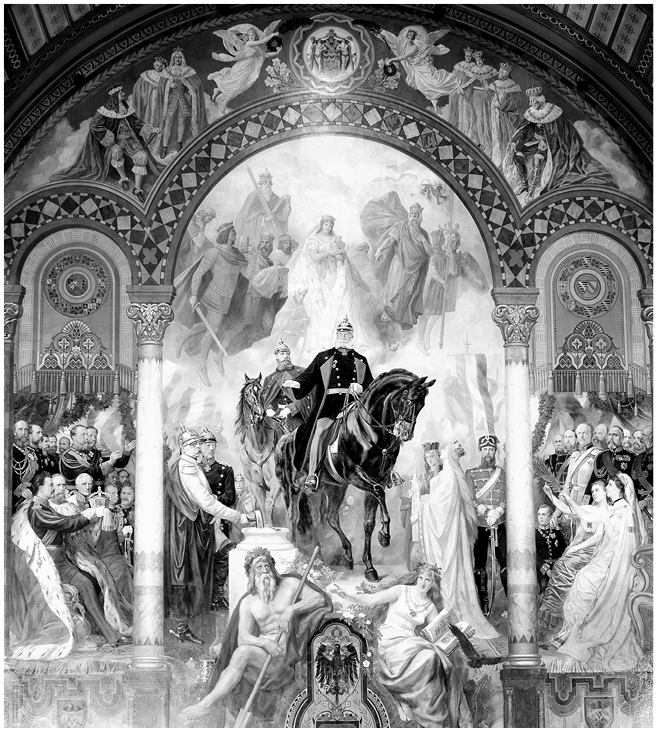

Goslar’s palace of the medieval Hohenstaufen emperors had been restored once that city had come under Prussian rule in 1868, and the restoration works were rounded off by an ambitious programme of some forty historical murals in the main hall. Executed by Wislicenus in the late 1880s, these evoked scenes of German history from Charlemagne to the 1870 proclamation of the Second Reich. They were arranged ‘in the round’ in a narrative sequence that positioned Wilhelm of Prussia as the white-bearded avatar of the greatest Hohenstaufen emperor, Friedrich Barbarossa. Recurrent themes run through this sequence: the emperor’s problems with insubordinate liegemen (the recalcitrant duke of Saxony and Bavaria foreshadowing recent frictions with the kings of Hanover and Bavaria) and with the papacy (foreshadowing the Kulturkampf, Bismarck’s attempt to root out Papal ultramontanism in Germany). Thus an anti-Papal and anti-Guelph continuity from Hohenstaufen to Hohenzollern is constructed; in the process, the Habsburgs’ long tenure of imperial dignity is written out of the story.

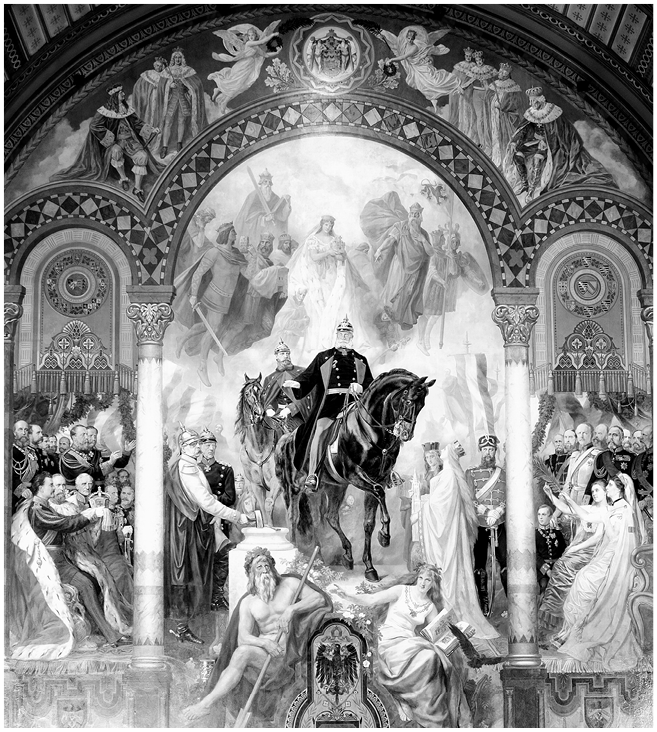

The entire cycle culminates in a huge centrepiece evoking ‘history coming full circle’. Wilhelm I’s re-establishment of the German empire is allegorically evoked as he and the Crown Prince ride on horseback towards the spectator (Figure 8.4). They are overseen by celestial spirits above them: their dynastic ancestors and their imperial predecessors, including Charlemagne and Barbarossa, and also the revered Queen Louise, Wilhelm’s mother. In the wings, on the right and left, are the Hohenzollern royal household and the assembled German princes; Ludwig of Bavaria is even made to proffer the imperial crown. They are flanked on one side by Bismarck and Moltke (the victorious general of the 1870–1871 war) and on the other side by allegorical representations of Alsace and Lorraine, now reunited into the Reich. At their feet are allegorical figures of Father Rhine and the Muse of German Legend, holding an open book.

Figure 8.4 Wilhelm I as Refounder of the Reich (Hermann Wislicenus, 1885; Imperial Manor, Goslar).

In this apotheosis, everything becomes a spectacle, with history, legend and allegorical symbolism merged into an eternal, timeless moment. That, indeed, is the overall effect as one enters Goslar’s Kaisersaal: a magic mountain (like Barbarossa’s Kyffhäuser, or the one where an elf queen entertains Tannhäuser) where time stands still, and all of history is suspended and simultaneously present. The effect is heightened by the shock-and-awe scale of the design: there is not a single surface that is not covered by heavily allegorical scenes visualizing historical episodes, and the visitor’s field of vision is wholly occupied by them, as in a panorama or an Imax 3D theatre. Furthermore, these scenes are often of a legendary nature and even involve fairy tales: the Barbarossa legend is dovetailed with the tale of Sleeping Beauty, depicted in numerous scenes as an allegory of the dormancy of the German Reich. The Muse of German Legend has good reason for sitting at the emperor’s feet.

Wislicenus’s hugely ambitious, densely layered and hyper-referential project was the grandiose culmination of a tradition that at the time of its completion was already beginning to be outflanked. The grand historical style, focusing on battles, coronations and crises at court, was no longer the only way to impress onlookers. Indeed, the academic style as a whole, including its flagship, the mural, was maintaining itself only in an increasingly isolated sanctuary, artificially nurtured by government commissions for high-prestige buildings.

A new avant-garde, deliberately defying the academic tradition, had announced itself when Gustave Courbet, rejected for an Academy Salon in the mid-1850, mounted a private exhibition that he entitled Le réalisme (more on this in Chapter 10). Amplified by other new developments (the rise of plein-air painting, of artists’ colonies and of new, looser brush techniques), the visual arts embarked on an agenda of innovative experiment that thrived in a climate of épater les bourgeois and moved sharply away from the conformism of the academy; at the same time, this new artistic vanguard moved away from historical topics in favour of landscapes, contemporary social scenes and abstraction.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s 1874 essay ‘On the Use and Abuse of History for Life’ marked a more generalized weariness with the monumental celebration of the past à la Wislicenus: historicism was pushed into the cultural margins by a more future-oriented, innovatory and critical approach to culture. Realism fed into Impressionism and the various secessionist and avant-garde movements of the fin-de-siècle and the twentieth century. All of these movements were united in their scorn for academic art, and art critics and art historians soon adopted that scorn.

Notwithstanding, historicism remained an inspiring modality in the late-emerging sub-imperial nationalities of Europe. In the Russian borderlands from Finland to Georgia, the state-sanctioned monumentalization of the past in academic painting had never been applied to subaltern cultural traditions. As new generations of artists emerged in these peripheries, fully sensitized to a more modern style and technique, they still felt the need to apply this to the retrieval and celebration of their national culture. Russian historicism flourished in an art nouveau style and was also used by Akseli Gallen-Kallela for Finnish mythological themes.14

Sentimental Historicism

Of course, history painting was more than bombastic murals. The historicism that was mentioned earlier, in the mode of Walter Scott, stressed not only the awesome and somewhat stilted grandeur of the past but also its relatable domesticity.

When setting the agenda for Romantic historicism, Scott had, uniquely, combined elements of alienation and recognizability in his evocations of history. His narrative focus was always on the domestic, private affects of his protagonists, while situating these in the grand sweep of historical crisis moments and transitions. He patented, as it were, the historicist dualism of empathy and exoticism. Ivanhoe (1819–1820) had evoked, in a sweeping historical canvas, the crisis of Plantagenet kingship during the crusading absence of Richard the Lionheart, amidst all the tensions of an ethnically divided, Saxon-versus-Norman medieval England; but it also depicted the private emotions of the protagonists, Wilfred of Ivanhoe and Rebecca.

That dualism had become the hallmark of the historical novel as such. In historical novels such as Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Lampedusa’s The Leopard and Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Napoleon’s Russian campaign needs its young Natasha Rostov, Garibaldi’s Sicilian campaign its ageing Prince of Salina, and the theological showdown between Dominicans and Franciscans its ingénu Adso of Melk. These fictitious protagonists with their private, individual relatability allow the past to ‘come to life’, to be empathetically experienced, imaginatively at least, from within, as it must have felt at the time.

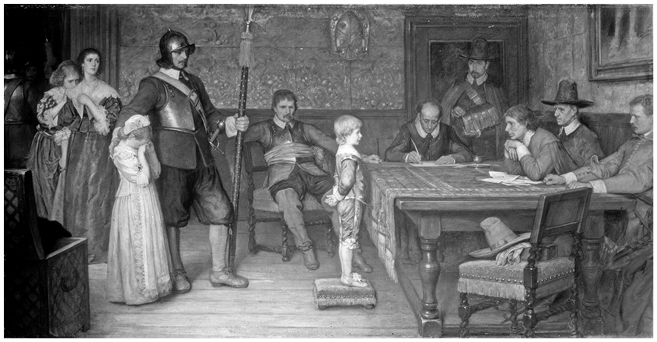

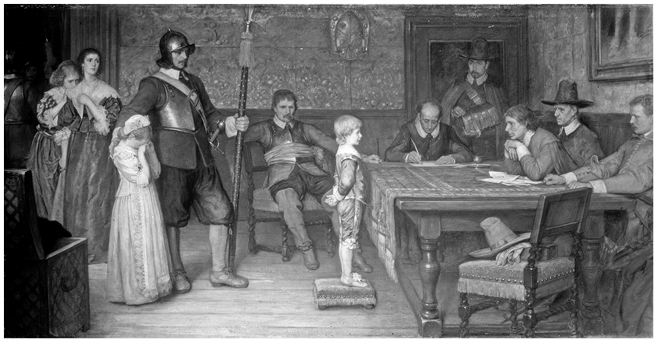

The vivid evocation of domestic familiarity amidst the sublime grandeur of historical distance was also attempted in Romantic history painting. Next to the grandeur of the battle and court scenes, we see the sentimental sub-genre of the ‘historical genre painting’. Genre art was one of the lesser academic styles, evoking scenes from domestic home life, frequently also involving middle-class or peasant settings. As the scenic settings of Brueghel, Van Ostade and Vermeer had receded into the past, they had become defamiliarized, quaint: illustrations of bygone manners and fashions.15 And this appealed to the many history painters who chose to take their topics not from the sublime or heroic register (battles, executions and coronations) but from the private lives of historical figures. And so we see various renditions of Charles V visiting Titian in his studio or Henri IV playing with his children. As the century progressed and Romanticism developed into Biedermeier or Victorian sentimentalism, this taste became more pronounced. William Frederick Yeames’s And When Did You Last See Your Father? (1878) shows Cromwellian investigators, hunting for Cavaliers, interrogating a young boy, whose mother, the wife of the fugitive cavalier, looks on in anguished apprehension (Figure 8.5).16 One can imaginatively immerse oneself in scenes such as these. The period detail, the lovingly rendered clothes, furnishings and interiors, are all meant to assist an emotional immediacy, helping the viewer to experience the past as it must have been experienced at the time.17

Figure 8.5 And When Did You Last See Your Father?

With the rise of realism this sentimental historicism also declines, along with the recession of the historical novel, which moved by way of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities and baroness D’Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel to the unprestigious margins of the literary system: the female readers of Georgette Heyer, the juvenile readers of G. A. Henty. Despite occasional masterpieces, the genre of the historical novel as a whole became, as the telling German word has it, gesunkenes Kulturgut, a depreciated cultural heritage. And something similar befell academic history painting.

Painters such as Il’ja Repin and Theodor Aman, who had made their names as academic history painters, turned towards more contemporary themes and a looser style, abandoning the clear outline that had been the hallmark of the fresco and of its historicist-academic derivations. As the great talents moved to different registers, national history painting proper subsisted as a pale imitation of its former self. It drifted from the salon and from palatial public buildings towards the eye-candy glitter of fairgound attraction and mass entertainment. Alongside Wislicenus’s Goslar murals, we see Árpád Feszty’s huge panorama celebrating the Hungarian Landnahme by the Magyars (1894), part of an entire fashion for 360°-panorama paintings embellishing historical tourist destinations all around Europe, from Sebastopol to Waterloo. History paintings were used for diorama pavilions in world fairs; Yeames’s And When Did You Last See Your Father? became a waxwork display in Madame Tussaud’s. Only in a few cases do we see that avant-garde artists of the later century continue to treat historical topics in a modern register: Puvis de Chavannes’s St Geneviève murals for the Panthéon (1874), Carl Larsson’s Midvinterblot mural for Stockholm’s National Museum (1915) and Alphonse Mucha’s Slavic Epic cycle (1910–1928).18

Remediations and Mass Commodification

This is the irony, then: the most august genre of the academic tradition, the history painting, around 1900 becomes almost a decorative art, used to embellish public buildings or tourist attractions. Its scenes were found less and less on canvas and more and more in remediated form: as engravings or illustrations for popular periodicals or historical surveys or albums such as the German collection Bildersaal der deutschen Geschichte (1890), or collectible chromolithographs, or educational school plates. The mural turned, increasingly, from paint to stained-glass windows and ceramic or glass tiles (mosaics such as those of the Venetian firm of Salviati, or azulejos in Spain and Portugal, or the tile tableaux on the outside walls of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum). Such media were also eminently suited to the fresco-derived style patented by the Nazarenes: a combination of bright colours and crisp outlines.19

That Nazarene style survived principally in the art of religious ultramontanism. There had always been a degree of Catholic fervour among the Nazarenes, and their art flourished most conspicuously in the altarpieces and pious lithographs and prayer cards distributed in their millions during the decades of ultramontanist devotionalism, showing ultra-saccharine, pastel-coloured madonnas, saints and biblical scenes. That this religious kitsch breathes and perpetuates the aesthetics of Nazarene Romanticism alerts us to the continuing, camouflaged subsistence of this school of academic painting. The same goes for the brightly coloured lithographs of Hindu deities popular among religious devotees and often encountered in Europe as restaurant decorations. These were pioneered by Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906), a successful Indian painter and lithograph publisher, who had learned his craft from a German, Nazarene-influenced teacher and applied it towards Nazarene-style icons of Hindu deities and Indian national and mythological heroes (Figure 8.6).20

Figure 8.6 The Goddess Saraswati (Raja Ravi Varma, 1896; Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum, Vadodara).

Far away from the salons and galleries, then, academic history painting left its traces – wherever, indeed, its celebratory piety and easy-on-the-eye style were suitable.Footnote * One such medium was that of the national currencies developed for newly independent countries after 1918. Artists such as Alphonse Mucha and the Latvian Rihards Zariņš, masters of decorative and graphic arts, produced patriotic propaganda posters (another suitable medium with its preference for the bright-colours/clear-outline register) and would later provide their newly independent homelands, Czechoslovakia and Latvia, with designs for postage stamps and banknotes, often involving allegories, scenes from the nation’s past, and portraits of the nation’s heroes.21

This is the diffused, watered-down legacy of academic art. In the terminology of Pierre Bourdieu, the genre has moved from ‘restricted’ to ‘unrestricted’ culture (mass-produced, non-exclusive, widely and cheaply available, and accordingly without exclusiveness or prestige). In Michael Billig’s terms it has become the genre of ‘banal nationalism’, merely ambient and unobtrusive after having once been the carrier of a definitive and explicit, ‘hot’ national agenda – yet (in spite of what the word ‘banal’ may suggest) wielding a huge influence, penetrating far and wide in society. Recalling David Lowenthal, we may also phrase it as a shift from the academy towards ‘heritage’ commodification. After its big splash in the early nineteenth century, history painting has become static noise, a vague background radiation in nations’ public spheres.22

Sic transit? Not quite.

A Repertoire

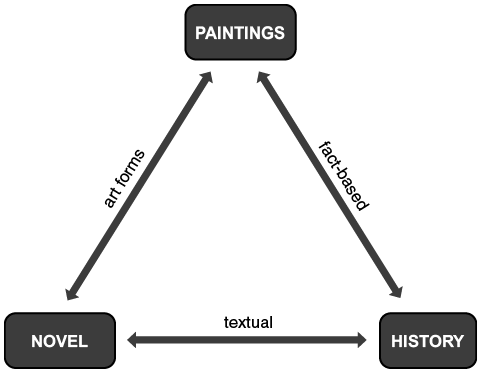

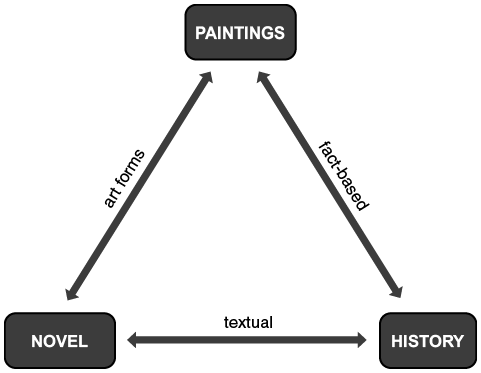

The true importance of history painting comes to the fore if we align it not with the other visual arts but with the textual media of historicism: history writing and the historical novel. We have seen how the rise of the history painting involved an increasingly visualized understanding of the past seen in historical rather than antiquarian terms; we have also noted the influence of Walter-Scott-style historicism and how its marginalization occurred more or less in tandem with that of the historical novel. These are not fortuitous coincidences; they bespeak a meaningful cohesion between the three genres. These relate to each other in a complex triangulation, in which two of the three are textual (the historical novel and history writing), one visual; alternatively, two of the three belong to the field of cultural/artistic production (the novel and history painting), one to the field of knowledge production (history writing). Finally, two of the three are factually representative (history painting and history writing), one fictionally narrative (the novel) (Figure 8.7).

Figure 8.7 History painting, history writing and the historical novel.

Against this background, we notice how very discursive history painting is. Much more so than landscapes, portraits or still life, it evokes a historical record and an intertext. We are meant to understand (or know first-hand) how the painting relies on accounts known from other, textual sources: histories mostly, but often also fictions (myths, epics or romances). The Edda, Iliad and Nibelungenlied furnished themes as well as Joan of Arc or the conquest of Siberia.Footnote *

In other words, the past was mined by historians, novelists and painters, and each of the three took their bearings from the other two. Like historians and novelists, painters had to negotiate the problematic relationship between a truthful, documented representation of the past and the need to fill the gaps in the documentary evidence by means of informed guesses and the imagination. Whereas the novel relies mainly on the organizing principle of a fictional narrative, history writing (even narrative history) is organized around the constraints of the available archive and pre-existing knowledge.23 In that negotiation, history paintings tended to gravitate to a documented rather than to a fictional past – based on existing knowledge, or on a known historiographical account. This means that history painting, although it is an art form, is quite close to historiographical knowledge production. It is, in a way, an illustration to history writing, transmuting the textual narrative into a spectacle and rendering accounts of the past, in the most literal sense of the word, imaginable.

The three genres parted ways after the death of Walter Scott in 1832. As history writing professionalized into the positivistic factualism of austere university departments, it was left to the art genres of the novel and painting to keep the Romantic sensation of the past alive. As they did so, they lost (as we have seen) artistic prestige and canonicity towards the end of the century; but they maintained their hold on the popular imagination. The public at large continued to imagine the past, and especially the Middle Ages, in the mode established by the Romantic generation; and novels and paintings helped to recycle and perpetuate that image.

The perpetuation was aided by reproducing and recycling Romantic evocations of the past in newly emerging media. Canonical narratives and themes had always been apt to move from one medium of expression (visual, textual or musical) to another: witness the importance of pictorial, theatrical and operatic spin-offs of historical novels. This also extended to new media as they emerged: waxworks and cinema in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the musical and video serials nowadays. Themes, narratives and affecting heroes and heroines (Joan of Arc, Wilhelm Tell, Mary Queen of Scots, etc.) move around among printed page, painting, the theatre/opera stage and the screen (silver or digital).

What was attempted in the nineteenth-century three-way intermediality between the historical novel, history writing and history painting, and continued in transferences to different emerging media, is a reconciliation between the textual and the visual, between narrative and spectacle.24 As we have noted, history paintings showed a gravitation towards the descriptive, anecdotal and narrative. Romantic histories and historical novels often took their readers to scenes set in the past and described as set-pieces, asking the reader to imagine and visualize a setting or situation. These genres were striving to unite the two modalities of art as distinguished by Lessing in his Laokoon of 1766: the Nebeneinander (one-next-to-another, objects arranged in space) and the Nacheinander (one-after-another, events arranged in time). History paintings tended to concatenate into cycles: witness Wislicenus’s narrative arrangements of the Goslar Kaisersaal, or Lenepveu’s series of scenes from the life of Joan of Arc in the Panthéon, or Mucha’s Slavic Epic: the narrativity of these scenes episodically arranged into cycles becomes almost that of the graphic novel.

As the canonicity of academic history painting was waning, its way of turning historical narratives into grand spectacle found a new medium of expression, perfectly combining Nacheinander and Nebeneinander, narrative and spectacle: that of film – ‘moving pictures’, as they were called. From D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation to Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky, the cinema screen became the successor to the theatre stage, the canvas, the mural, the diorama, for the projection of a Romantically evoked past. The great epic blockbusters and action movies of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, which we shall survey in more detail in Chapter 12, in many cases recycle tales and scenes, narratives and spectacles, from the national past as they were rendered canonical by historians, novels and paintings during the Romantic period.

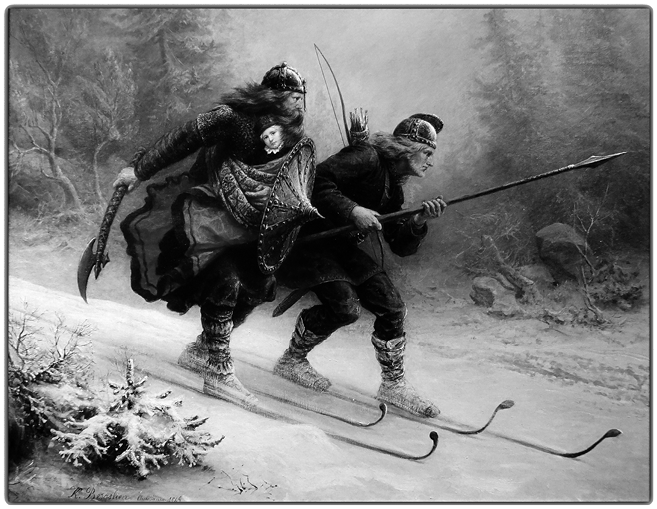

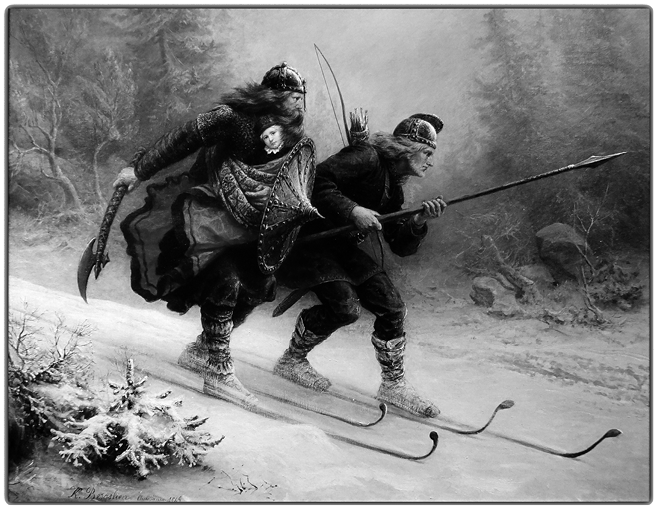

How that perpetuation worked may be illustrated by the telling example of the Norwegian movie Birkebeinerne (‘Birchlegs’, i.e. men with birchbark leggings, 2016; marketed internationally as The Last King). It revolves around a historical episode rendered memorable by the Romantic historian Peter Andreas Munch in Det Norske Folks Historie (1852–1863) and, following him, by Knud Bergslien’s iconic history painting of 1869 (Figure 8.8). That painting was picked up in the 2016 movie poster for Birkebeinerne by the contemporary artist Marcell Bandicksson. Norwegian historians have moved on from Munch; Norwegian painters have moved on from Bergslien; but Norwegian cultural memory is still deeply informed by their Birkebeinerne.

Figure 8.8 ‘Birchlegs’ Skiing Across the Mountains with the Infant King

Even in the twenty-first century, Romantic history painting, with its celebration of the nation’s colourful past, is alive and kicking in the ecosystem of popular cultural memory; and epic still thrives.