Between 2017 and 2018, during my preliminary fieldwork in Kampala, Uganda, I encountered two judicial archives that had remained inaccessible and institutionally forgotten: the High Court of Uganda archive and the Mengo Court archive. These collections, containing legal activity from the early colonial period into the post-independence era, had never been catalogued or preserved in a way that allowed for meaningful scholarly engagement. The High Court archive preserved the court’s own appellate records. This court was established in 1902 and served as Uganda’s final court of appeal until the 1995 constitution created the Supreme Court as the new highest court of appeal. The Mengo Court archive housed legal records from the Kingdom of Buganda, which functioned as a semi-autonomous principality within Uganda and controlled its own institutions and legal system that operated simultaneously but largely apart from the British colonial courts. The archive contained case files from Buganda’s Principal Court often referred to as the Lukiiko, which served as the highest appellate native court for Buganda native and subordinate courts throughout the kingdom. The archive also housed records from the Mengo Magistrate’s Court, the Coroner’s Court, and the Judicial Adviser’s Court. Despite their historical importance, both collections were abandoned in court building basements, heaped in large, disordered bundles, some stacked on unstable wooden shelves, others stuffed into sacks and left on the floor (see Figures 1a,b and 2a,b). Covered in dust, ravaged by damp and insect damage, these uncatalogued records were too fragile to handle and logistically inaccessible to researchers; even the judiciary’s record staff struggled to consult them.

Figure 1. (a, b)The High Court Archive. All photographs are by the author (2018).

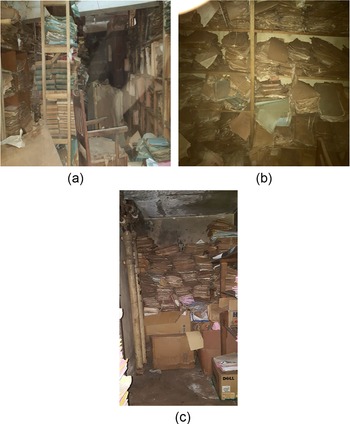

Figure 2. (a,b,c)The Mengo Archive.

The poor conditions in which these records were stored expose the institution’s neglect of their preservation. The Judiciary record staff I worked with often dismissed these records as too old or of little value to warrant preservation. For instance, during the cataloguing of the Mengo court records, the judiciary staff in charge of these records asked, “madam Sauda, after we finish cataloguing these old documents, will you destroy or burn them?” I replied, “Of course not.” That question laid bare an institutional perception of these materials as disposable relics and reflected the broader indifference towards vernacular legal records that neither originated from the formal colonial British courts nor contributed to precedent-setting jurisprudence. Native court records were particularly neglected because they did not conform to legal and documentary standards imposed by the colonial legal order. Several telling instances of this contempt are evident in the Mengo records’ treatment; the poor quality of the paper on which they were written and the deplorable conditions in which they were stored. These records were written on brittle paper, and stored in a basement next to the prisoners’ toilets, and other records were stacked in a room with sewage lines which sometimes overflowed and damaged the documents (see Figure 2 (c). Through ventilation holes in the storage rooms, inmates could pull out documents to use them as toilet paper. Such physical destruction and administrative contempt were not accidental but the result of a legal system that valued British court records over local ones. Yet judges and clerks still consult these records, especially in land, inheritance and kinship disputes, because statutory law often offers no clear guidance in those matters. The paradox between institutional neglect and ongoing practical utility reflects the unresolved tensions within Uganda’s legal memory regime.

The continued survival of these records cannot be attributed solely to bureaucratic inertia: they have endured because they remain useful. For decades, they have existed in poorly ventilated basements, uncatalogued and unprotected, yet they continue to serve as active instruments of adjudication. Their material degradation reflects a broader constellation of structural failures: inadequate archival training, lack of preservation mandates and the enduring legacy of a colonial legal hierarchy that determines what is preserved and what is discarded. The disparities in storage conditions, paper quality, and preservation between the High Court and Mengo archives reveal not only differences in material care, but also institutional hierarchies that have shaped – and continue to shape – forms of legal knowledge deemed worthy of preservation.

Two archives, two legal worlds

The High Court and Mengo Court archives preserve two profoundly different legal worlds, not only in format and language, but also in their assumptions about what law is, who defines it, where it is located, and how legal knowledge is produced and preserved. The High Court records which I discovered first, reflect the hierarchical and textual structure of British colonial law. Typed in English and shaped by legal formalism, these files offered the kind of material a legal historian might expect: statutes, appellate decisions and legal reasoning filtered through the institutional voices of judges and magistrates. Litigants appear only in the background; their arguments are reframed in narrow legal terms and stripped of urgency, emotion, or social context. What emerges is a version of legal life focused on procedure, precedent and jurisdiction – concerns that flattened the substance of the disputes into procedural abstractions. The more I read these documents, the clearer it became that this archive did not just reflect legal knowledge, it manufactured it through selective practices that made some forms of knowledge and experience visible while discarding others.

One case captured this colonial legal imagination with startling clarity. In a 1928 appellate ruling, Chief Justice Sir Charles Griffin overturned an arson conviction issued by a native court, declaring that the decision was ‘so entirely unsupported by evidence’. He criticised the native court for relying on hearsay and rumour as evidence, describing the outcome as ‘short of shocking’ and asserting that it ‘offends both reason and justice’. In a public commentary published in the Herald newspaper on this case, Griffin condemned native courts more broadly, calling them ‘an anachronism hardly in keeping with the march of progress’. He stated that they should be brought ‘into line with the principles and procedures of British justice or be abandoned, and their duties handed over to British courts’.Footnote 1 Griffin’s opinion was not just a critique of a specific case, it reflected a wider colonial belief that British law alone was capable of impartiality and reason. Native legal practices, in contrast, were considered morally and procedurally deficient. Griffin’s judgement is indicative of a broader colonial project that marginalized African legal practices and actively promoted British legal principles as the sole arbiter of impartiality and rational justice. As H. F. Morris later wrote, British judges of this era sought ‘to impose upon African society rules and technicalities of English law which were inept, incomprehensible, and even dangerous in an African context’.Footnote 2

These court records, like many other legal sources I encountered in archive, made visible how colonial legal officials actively promoted British legal norms only through court judgments but through the production of documentary sources like newspapers articles, legal publications which disparaged African legal practices as backward. Griffin’s statements reveal how colonial judges understood their role not simply as judges of legal disputes but as agents in shaping historical narratives that justified the expansion of British legal authority. Recognising the role of history in that project, they compiled and preserved documents with narratives that depicted indigenous adjudication practices as traditional, primitive, irrational or superstitious, while presenting British law as modern, coherent and rooted in scientific reasoning. These records spoke in the authoritative voice of British law and the colonial state, but what they left out was equally telling. The significance of African legal traditions is often diminished in the historical record because these documents were created and curated by those who discredited them, and it is those voices that continue to dominate historical narratives.

The silences and epistemological limits of the High Court records made my discovery of the Mengo Court archive especially revealing. I unearthed the Mengo archive while organising the High Court files. The contrast could not have been sharper; the Mengo records offered a messier but far more intimate picture of legal life in colonial Buganda. While the High Court archive was structured, typed in English and shaped by British legal formalism, the Mengo archive preserved a different legal world of how law functioned at the local level – through informal communal adjudication, vernacular legal reasoning and the everyday practices of law by ordinary Ugandans. These records included witness testimonies, statements from complainants and defendants, letters, petitions, evidence and reports from local authorities.

What makes the Mengo archive important is that it preserves the voices of ordinary litigants, those most often omitted from law’s archive – women, labourers, migrants and the poor – people who pursued their cases, made claims in their own words, using moral arguments rooted in shared norms and local understandings of law and justices. In this archive, law was not confined to formal courtrooms or legal professions; it was made and practised anywhere people gathered – in the shade of a tree, in courtyards, homes, or within the chiefs’compounds. It is these gatherings that became de facto hearings, spaces where grievances were heard, testimonies offered, and disputes resolved through deliberations that were intelligible to those involved. The Mengo records are not merely legal files; they are fragments of social history: evidence of how people argued, how they appealed to shared norms, and how they insisted that justice be responsive to their lived experiences. This version of legal culture – informal, dialogic and locally situated – is largely absent from the colonial state’s official archives, yet it is precisely in these cases that one encounters how Ugandans understood law not as a distant institution but as a practice embedded into their everyday lives.

Despite their historical value, these materials had been neglected and were in a state of advanced physical deterioration. One of the most difficult challenges in organising the Mengo archive was preserving the traces of meaning in documents that were very old, fragile, and never intended to be preserved by the legal system. While the High Court records I encountered were also considered ‘unimportant’ and neglected because they contained cases of ordinary people, they had at least been preserved in relatively good condition. By contrast, the Mengo court records were poorly preserved, disorganised, and physically fragile. Handwritten in Luganda on low-quality paper, many were water-damaged, torn or partially eaten by white ants. Their deteriorating physical state mirrored the broader archival disregard for vernacular legal traditions and local knowledge systems. Yet the linguistic and material fragility of these records does not reflect their epistemic richness. To an outside reader, the informality of the proceedings and the register in which they were recorded might suggest a legal system mired in tradition or resistant to change.

The Mengo records are difficult both to read and interpret, not only due to their fragile physical condition but also because they are written in vernacular Luganda, often using idioms, proverbs, popular sayings and expressive forms that do not translate easily into the formal categories of colonial legal discourse (Figure 3a–c). The handwriting is often dense, rushed and inconsistent because of the pace of oral testimony and the working practices of clerks with no formal legal training. Some documents in the files were written by litigants themselves; others were produced by chiefs who helped to mediate disputes. These were not files created with archival preservation in mind, nor were they intended to serve as legal precedent or be incorporated into formal case law. They were the by-product of encounters as they unfolded, messy, immediate records of oral complaints and testimonies hastily written down, and with decisions delivered on the spot; they were judgements shaped by consensus and the social dynamics of the people involved. Once the cases were resolved, the documents were folded into bundles, tied with ribbon, filed away; and eventually forgotten along with the legal culture, the people involved in these cases, and the broader social context that had produced these documents.

Figure 3. ( a, b c) Indicative trial records in their current state of preservation.

However, these records preserve something that formal legal archives rarely do: a record of the workings of customary law as it was practised, not in abstraction or doctrine, but in the lived experiences of ordinary people. What these records capture was not simply ‘custom’ but a legal culture that was oral, participatory, and relational. They document the language and internal logic of African jurisprudence as it was practised, contested, and reshaped in real time, not only in courtrooms, but also outside court in the communities where some of these disputes were resolved. Law here was not invoked abstractly, it was practised and shaped through the actions, opinions and decisions of those directly involved.

A striking illustration of this legal world appears in the 1949 case of Mbawadde v. Kiwanuka and Mayanja.Footnote 3 In this case, two schoolteachers brought charges against two Gombolola chiefs for attempted rape. The women’s testimonies described how the men entered their home, forcibly separated them in different rooms and attempted to assault them. The women raised enduulu (an alarm), prompting neighbours to rush to the scene, apprehend the chiefs, gather evidence, and report the matter to the Gombolola chief. When the chief failed to act, likely because of the accussed men’s status, Mbawadde and Nabitosi pursued the case through a chain of appeals, enlisting the support of a local priest, and the Ssaza chief; eventually the case reached the Principal court of Buganda. In court, the victims, the accused and the witnesses gave their testimonies in turn, recounting what had been said and seen. The court ultimately convicted both men based on the witness testimonies: Mayanja was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour, and Kiwanuka to two months for aiding and abetting. What stood out to me in reading the file was not only the outcome, but the procedural form. Although the final charge referenced the 1918 Buganda Adultery and Fornication Law, this statute was never cited during the proceedings nor used in the court’s deliberation and decision. Notably, in native courts, charges were not framed at the outset but were determined after all testimonies had been heard. This sequencing—testimony first and legal classification later—reveals the priority native courts gave to oral testimonies and concrete circumstances rather than physical evidence or written law

When the chiefs appealed to the British courts of law, they argued that the witness testimonies were inconsistent, that no medical evidence had been presented, and invoked British legal precedent in their defence. But their appeal failed. The British judge upheld the native court judgment, noting the ‘general agreement’ among the witness accounts. What was crucial, the judge noted, was that ‘the Principal Court found the witness testimonies to be credible’. In administering justice, native courts did not aim to enforce abstract laws, or protect individual rights in the modern sense, or produce binding precedent. They instead sought to right wrongs and restore balance in a way that was intelligible to the community. As Lloyd Fallers noted in his study of native courts in colonial Busoga, legal reasoning in these courts operated ‘without precedent or legislation’.Footnote 4 Judgments did not rely on written law or prior decisions but on situated knowledge of those present, individuals who had witnessed the incident, who knew the parties involved, or who could speak to their reputation and conduct.

This logic permeates the Mengo records, shaping not just the outcomes of cases but also how disputes were described, how testimonies were evaluated, how justice was interpreted, and how these cases were ultimately recorded. These records reveal more about the legal process, social relations and cultural values than they do about the legal issues. Judgments rarely include legal reasoning; instead, the documents provide detailed accounts of events – who said what, when, where and how people responded. Typically, the files document the sequence of events: the initial complaint, summons, testimonies, cross-examinations, evidence, the final verdict, and the charge. The records are rich with detail, including people’s names, what they wore, what they said, who raised the alarm, who responded, and the objects or evidence found. These were not merely dispute logs but reconstruction of a social world. In a single file, one could trace an entire community’s social dynamics. As I read through these files, I could hear these people’s voices speaking, especially when I read their testimonies aloud. One witness recounted, ‘We all arrived together and met the girls in the yard, where they were raising an alarm. While still in the yard, Mayanja emerged from the house, half-dressed. Muwonge had a torch and entered the house, where he found a coat, kanzu and two bottles of native beer on a table.’ This testimony, like many others, not only recounted what happened, the immediate response, but also captures how wrongdoing was interpreted, and the relational weight given to people’s opinions, participation and presence. A close reading of these files reveals how law functioned in people’s daily lives and how people actively influenced the legal process.

Working through the Mengo archive changed how I think about law and its archive. These records show that law in these courts was imagined and practised in expansive ways, grounded in everyday life, not confined to formal courtrooms or codified statutes. What constituted customary law was not a fixed body of rules but the people themselves and the local knowledge from which they drew. Law unfolded wherever disputes arose, even at the site of the incident. The moment someone raised enduulu (alarm) and neighbours responded, the legal process was already in motion. Often, this involved rushing to the scene to witness events as they unfolded, apprehending the accused, gathering evidence, reporting offenders, and assembling before a chief to offer information (obujulizi) that ultimately resolved. The importance of social witnessing was why witness testimonies carried more weight in court. Even in civil disputes, the courts relied the courts relied on people’s situated knowledge to resolve them. In court, witnesses testified one by one, recounting what they had seen, heard, or knew about the event or individuals, including their reputation. What mattered was not adherence to formal procedure or abstract legal reasoning, but collective participation and shared understanding. These courts did not operate according to formalised legal procedures or fixed institutional logic. Instead, law in these courts emerged from the everyday lives of ordinary people – from how they acted, how they responded to conflict, and how they sought resolution within a web of social relationships. Reading these files, I saw how the legal process was inseparable from social life: highly personalised, communal and dependent on the presence, participation and judgment of those involved. People did not just witness proceedings or law being applied; they participated in, and constituted the legal process itself. This is clearly evident in the record of Mbawadde v. Kiwanuka and the Mayanja case, where community members did not just testify, they intervened at the scene, detained the accused, provided evidence and demanded accountability.

The Mbawadde case and many others I encountered helped me see how deeply localised this legal order was, and how much authority ordinary people exercised over law and justice. These records disputed the assumptions I carried into the archive, especially those in African legal historiography that view native courts as marginal or as sites of ‘custom’ rather than law. What I found instead was a legal system that was substantive, responsive and flexible, capable of working with multiple sources of law, including colonial laws, religious norms, local knowledge, and shared moral expectations. While colonial officials may have viewed these courts as inferior or informal, the records show that these courts exercised considerable legal authority and often resisted the imposition of foreign legal principles. Instead, they adapted or reinterpreted law in ways that made sense to those involved in the dispute. They defined and enforced laws in ways that preserved communal values and, at times, acted in quiet defiance of colonial legal categories. These courts cannot be understood as merely instruments of colonial administration. Rather than seeing these courts as outside the law, the records compel us to recognise them as part of an evolving legal order, one that remains foundational, yet largely neglected in Uganda’s legal history.

The significance of the Mengo archive lies not only in what it contains but in what its survival and its prior neglect reveals about the violence of law’s archive and the politics of legal memory. When I first encountered these records, they had not been preserved in any official repository or protected as historical sources. There were no catalogue entries, no archival labels, and no recognition of their legal or historical value. As the pictures above show, many files had been abandoned in court basements, disordered, some damaged, and others shoved into sacks and covered in dust. Their material condition, brittle, worn and fragile – mirrored the institutional disregard for the legal world they documented, one that relied on the participation of people in their communities, and functioned in vernacular languages, through oral testimony, and community-based adjudication. These were records not of a codified system, but of a legal life that drew from cultural traditions, local knowledge, and shared moral reasoning. These records had not been forgotten by accident. Their disorder, their informality and their nonconformity posed a challenge to colonial legal frameworks and to the archival standards that continue to shape what gets remembered as law.

Yet despite their condition and neglect, these records revealed a rich and layered legal world. To recover this rich legal history, in 2018 and 2019, I worked with students from the University of Michigan and Makerere University, and staff from Uganda’s judiciary, to recover and catalogue over 150,000 of these records. We eventually transferred them to the National Archives, but the work we did was not simply about salvaging deteriorating documents: It was a reckoning with the deeper assumptions embedded in colonial legal authority, about what law is, where it resides and who gets to define it. When I began reading the Mengo records alongside the High Court files, the contrast was immediate and disorienting. The High Court archive presented law as centralised, codified and insulated, its authority rooted in textual abstraction and uniformity. The Mengo archive, in contrast, revealed law as a social practice: flexible, responsive, informal and rooted in everyday interactions. The difference was not just procedural. It revealed two divergent ways of thinking about what law is, and how it functions. The Mengo archive challenges the conceptual frameworks that continue to separate law from society and exposes the limits of definitions that treat law as distinct from the social worlds in which it is practised, contested, and remembered. That realisation prompted me to take the Mengo archive seriously, not just as an overlooked source but as an archive that compels us to rethink the categories through which law has historically been understood.

It was this discovery that led me to centre the Mengo archive in my research, not merely to recover a neglected source, but to engage different conceptions of law. As Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues, recovering the ideas and practices of marginalised actors requires decentring official state archives as the exclusive locus of political and legal thought. The Mengo archive enables that displacement. It forces us to confront the existence of multiple, and at times conflicting legal traditions within law itself, rather than displacing them onto society as informal. It reveals a juridical tradition rooted in vernacular reasoning and shaped by overlapping legal authorities and sources, including customary, religious, and colonial law, all of which often operated in tension. These records do not reproduce colonial legal categories; they disrupt them. They do not merely supplement colonial law; they contest the very terms through which legal authority has been historically constructed. Although scholars in archival theory and postcolonial studies have long exposed and critiqued colonial archives as partial, fragmented and shaped by structures of power, legal historians have been more cautious in applying this critique to law’s own archive. The Mengo archive brings that critical gap into view. It exposes the hierarchies of visibility and exclusion that structure how law is remembered, documented and studied. It invites a methodological shift: away from reading colonial archives as coherent and complete, and towards an interrogation of their omissions, distortions and silences. It reminded me that archives are not neutral repositories of memory – they are instruments of classification, erasure and power.

It was through this archival experience that the critiques of scholars like Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Renisa Mawani, Marisa Fuentes, Michel Foucault and Carlo Ginzburg began to resonate with a new clarity and urgency. Trouillot’s insistence that archival silences are not accidents but products of power was evident in the institutional disregard that shaped the fate of the Mengo records.Footnote 5 What Fuentes calls ‘the violence of the archive’ – its distortions, its biased representations that privileged colonial perspectives and its refusal to preserve lives and experiences of those that did not conform to official narratives, was not a metaphor in this context.Footnote 6 It was visible both in the curated records of the High Court archive where colonial legal officials and legal reasoning shaped what could be recorded and in the fragmented Mengo files: the damaged pages I tried to reassemble, the hurried notes scrawled in the margins and the testimonies folded into forgotten bundles. Mawani’s description of law’s archive as a structure of ‘juridico-political command’ rather than a neutral repository helped me make sense of how legal authority was not only exercised in the courtroom but also consolidated through selective archival preservation. Her argument that law is the archive; that it gains its authority through practices of generating, compiling, organising, referencing, absorbing and excluding other forms of knowledge, clarified how the Mengo archive had been marginalised not by neglect, but by design.Footnote 7 Foucault’s claim that the archive governs what can be said, who may speak, and what counts as knowledge, was evident in how these documents had been excluded from laws archive and legal historiography, not because they lacked evidentiary value, but because they did not conform to the normative expectations of legal authority, record-keeping or textual form.Footnote 8 Ginzburg’s analysis of inquisitorial records further sharpened this point: he shows how legal proceedings and the written documents they generate can mediate and distort the voices of the litigants, offering only fragments of their experiences.Footnote 9 My own archival work brought these critiques into sharper focus and forced me to confront the epistemological law’s archive and to reckon with its material silences. Yet as Mawani argues, law’s archive has often been treated by legal historians as a repository of truth, its rulings and statutes accepted as authoritarian evidence rather than as a discursive apparatus shaped by power, exclusion and the classificatory practices of the state. The Mengo archive exposed those assumptions and compelled me to rethink what counts as legal knowledge and whose voices it authorises.

How we interpret and make sense of these two archives, one which suppressed both the practice and internal logics of the indigenous legal system by casting it as backward, and the other that contested this view, animates my research. Reading these two archives side by side revealed not just two bodies of legal material, but two distinct epistemologies of law, two different ways of thinking about legal authority, justice and memory. In reflecting on my experience with these archives, I have come to see this contrast not just as an institutional divergence but as a fundamental difference in how law was imagined, practised, and remembered. The High Court records reduced disputes to their procedural essence, often silencing the voices of litigants or translating them into a legal register that made them legible to the state, but unintelligible to themselves. I found myself reading through summaries written by judges, only to wonder: where were the people? Their pain, intentions, strategies and language had been flattened, and their stories lost to procedural abstraction. By contrast, the Mengo records retained the messy, embodied and social dimensions of law. These were not transcripts of polished legal reasoning, but fragments of speech, memory and community judgment. Even when the records were incomplete or mediated through the hand of a clerk, the voices were still present – speaking in Luganda, invoking shared norms, demanding accountability or negotiating their place in the moral world. These files reminded me that law is more than a structure or a rule book; it is also a way of telling stories, of interpreting wrongs and responsibilities, and of making meaning out of injury. In these records, law functioned not as an external imposition but as a vernacular process — lived, narrated, and contested in the idioms of those who relied on it. Recovering these materials was not just about saving fragile documents; it was about reclaiming a world of legal thought and practice that the colonial project tried to erase or marginalise, that was never meant to endure, and that African legal historiography has yet to fully reckon with.

A final reflection: local court records and the disruption of colonial legal authority

The case of Nabowa v. Mukasa, heard in 1937, offers a compelling illustration of how local court records unsettle the boundaries between law and custom, and challenge the assumptions embedded in colonial legal categories.Footnote 10 This dispute involved Nabowa, a single woman, and Mukasa, a wealthy landowning chief who had allowed to live on his land under an oral agreement: she would provide domestic labour — cooking, farming and other services — in exchange for the right to reside there. Their arrangement was informal, and by conventional readings of Buganda’s property order, customary. Conflict arose when Nabowa began operating a bar on the land, which Mukasa characterised as a brothel. He accused her of abandoning her domestic obligations, running an immoral business, and ultimately issued an eviction order. Nabowa refused to leave unless Mukasa compensated for her property and crops. When Mukasa violently evicted her and destroyed her grass-thatched house, Nabowa did something that a woman in her position could not have done in the precolonial era. She sued Mukasa for unlawful eviction and in court, claimed not to be a domestic servant, but a tenant protected under the 1928 Busuulu and Envujjo Law, and claimed compensation for her property. In her words, ‘the labour she had provided – cultivating Mukasa’s garden, cooking food translated into Busuulu (rent) paid by tenants’, invoking the very legal categories in the law that did apply to women like her. Nabowa’s claim was an audacious one, particularly within a legal and social context where women’s claims to property were tenuous in early twentieth-century Buganda.

Mukasa never denied evicting Nabowa or damaging her property. On the contrary, he claimed the right to do so, arguing that Nabowa’s disobedience and immoral conduct warranted her removal since she was not a tenant. He rejected her interpretation of the Busuulu law, insisting that the law only protected and applied to male tenants who paid in cash or kind, not to women performing household work. In his testimony, he described Nabowa dismissively as ‘one of my ladies in my kisakate … whose duty it was to till work on my banana garden and cook food for me’. At issue in this case was whether Nabowa was a servant or a tenant, a distinction which had significant implications for her rights to land and compensation. Mukasa claimed that according to Buganda’s custom, food prepared by women could not constitute rent. ‘None of us eats food women cook as Busuulu,’ he told the court, ‘but we eat food our women cook as the culture and customs of our country.’ Yet despite his arguments, the lower court ruled in Nabowa’s favour ordering Mukasa to compensate her. When Mukasa appealed to the High Court, the High Court upheld the native court decision, but acknowledged that the Busuulu law had been misapplied, since Nabowa was not a tenant and did not pay rent in the form required by statute. The judgment did not affirm her status as tenant, but it validated her right to redress by ordering Mukasa to compensate her loss. That outcome – and the legal reasoning – was what I found most striking when I read this case I found in the Mengo archive.

At first, I flagged this case because it seemed to reinforce what I already knew about colonial land reforms, especially the Busuulu and Envujjo Law of 1928, which scholars have long argued transformed landlord–tenant relations in Buganda by granting landless tenants formal rights and curbing the unchecked authority of chiefs. Nabowa’s words and action made those legal transformations visible in a way that was difficult to ignore. But as I read more closely, the case revealed something else. My initial interpretation masked a more interesting story: one of legal change initiated by those absent in formal legal archives, unfolding in places most of us would not typically associate with law, and in disputes often dismissed as customary or extra-legal. This case was heard in a customary court, and the reasoning drew from statutory law, local practices and moral judgment of what was considered right, fair and just. Nabowa did not simply invoke the law – she expanded what law could mean by insisting that justice required recognising the value of her labour by compensating what she had contributed and lost. Her victory did not hinge on technical compliance with statutory definitions of tenancy. It rested on the recognition that her labour had value, and that evicting her without compensation violated shared moral expectations. Judges in these courts usually relied on values like amazima n’obwekanya – truth and fairness – not as abstract ideals, but as practical tools for making decisions.

Such cases would never have reached courts of law if colonial legal changes had not emboldened even those whom the statutes did not explicitly protect. The Busuulu law forced Buganda leaders to extend rights to the landless bakopi, making it possible for Nabowa to turn a household dispute into a legal matter. Those legal and moral expectations explain why bakopi like Nabowa brought their complaints to court, even when their claims to property were informal and tenuous. Her case shows how native courts became arenas where legal meaning was negotiated and reshaped. When claims about what was right, fair, and just reached British courts of law, they acquired meanings that they did not have in native ones. The British courts, which lacked an established body of law to handle the wide range of socially embedded and morally charged disputes brought before them, struggled to adjudicate such cases effectively. While British judges sometimes used tenancy cases as a platform for enforcing consistency within colonial law – even when doing so produced outcomes that seemed absurd to lay observers or unjust by the standards of many Ganda – in most cases, they were sympathetic to the landless bakopi and interpreted tenancy law in ways intended to curb the abuses of landowning chiefs. Reading these records, one can almost picture the judges – brows furrowed, heads in their hands, struggling to make sense of conflicts far removed from the legal categories in law they had been trained to apply. The legal categories that mattered were not those inscribed in colonial law, but those constructed in customary practice – shaped through negotiation and judgment rooted in the everyday lives of ordinary people.

What made Nabowa’s case so striking to me was that it forced a rethinking of the analytical frameworks that continue to shape the historiography of African law. Much of the literature maintains binary distinctions between custom and law, informal and formal, textual and oral, vernacular and codified. But her case and many others in the Mengo archive, show how these categories collapse in practice. Her claim emerged from an oral labour arrangement, yet it relied on statutory classifications; her argument was rooted in lived experience, but she translated that experience into a legal form the courts recognised. The judgment itself blended custom and statute, awarding compensation even as it acknowledged a misapplication of the law. None of this appears in the published legal sources that scholars rely on for their research. These cases were not cited or published in law reports. They survive instead on old, fragile, insect-bitten paper, written in Luganda and stored in court basements that were nearly forgotten. Recovering and reading these records compels us to ask different questions: What counts as law? Who defines its categories? Where is legal meaning produced, and who preserves it? Nabowa’s case, like many others in the Mengo archive, does more than fill archival gaps in the colonial record. It reveals the instability of colonial legal categories and shows how litigants like Nabowa brought everyday disputes into legal arenas, demanding that the law respond to their claims and expectations that fell outside its formal definitions. These records show how ordinary litigants shaped the content of law and its application – not just by invoking formal statutes, but also through the claims they made, the grievances they voiced, and the moral expectations they brought to court. That, in the end, is the disruption these vernacular court records enact, a disruption that invites us to reconsider not only what counts as law, and who has had the power to define it, but also what should be preserved.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the University of Michigan, the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), and the Judiciary of Uganda for their generous support of this archival work and research. I want to thank my advisor, Derek Peterson, for encouraging me to look for court archives and for his substantial support of these archival projects. I’m also grateful to the students from the University of Michigan and Makerere University, as well as the judicial staff, for their assistance in organizing and cataloguing the High Court and Mengo Court records and in transferring them to the National Archives of Uganda. I am especially thankful to my children, Abdul Kizito and Mariam Nassuna, for helping preserve these archives and assisting with data collection. These records are now housed in the Uganda National Records Center and Archives (UNRCA), and I am currently seeking funding to digitize these collections to ensure their long-term preservation and wider accessibility. Any errors remain my own.