Impact statement

Psychosis affects millions of people worldwide, yet most live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where access to mental health professionals and evidence-based treatments is limited. Families often serve as the primary caregivers, but they receive little guidance or support. This study responds to that critical gap by adapting and testing a family-based intervention – originally developed in the United States – for use in Pakistan. The adapted program, called Ca-REACH, equips family members with practical skills to reduce distress, improve communication and support recovery for their relatives with psychosis. The intervention was adapted by local stakeholders and delivered to 40 caregivers in Lahore, Pakistan. Findings show that caregivers and individuals with psychosis both benefited from the program, with high participation rates and meaningful improvements in well-being and symptoms. These results highlight that culturally adapted, family interventions can be both feasible and effective in LMIC contexts. Beyond Pakistan, this work offers a roadmap for other countries seeking to strengthen family engagement in mental health care without relying on scarce specialist resources. By showing how a structured adaptation process can preserve core therapeutic principles while respecting cultural and contextual realities, this study contributes to global efforts to make mental health care more inclusive, scalable and sustainable. In doing so, it advances the broader goal of global mental health equity – ensuring that families, wherever they live, have access to the knowledge and skills needed to support recovery from serious mental illness.

Introduction

The landmark Global Burden of Disease study drew attention to the fact that mental illness represents one of the leading causes of disability worldwide (Viana et al., Reference Viana, Gruber, Shahly, Alhamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bruffaerts, Caldas-De-Almeida, Girolamo, Jonge, Ferry, Florescu, Gureje, Haro, Hinkov, Hu, Karam, Lépine, Levinson, Posada-Villa, Sampson and Kessler2013). The ramifications of undiagnosed, untreated and under-treated mental illness are most acutely felt in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), where more than 80% of people who have mental disorders reside. Although a low-prevalence disorder, it is estimated that schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders account for 9.8% of the total burden of disease in LMICs. Recent estimates suggest that schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders contribute substantially to disability-adjusted life years in LMICs, with estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 and 2021 studies suggesting figures ranging from 9–11% depending on the inclusion of comorbid conditions such as self-inflicted injuries (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Fan, Yang and Fan2025; Patel, Reference Patel2007). These prevalence figures require careful interpretation, but underscore the disproportionate impact of psychotic disorders in low-resource settings.

Extensive research, including recent large meta-analyses, has demonstrated that family interventions for psychosis (FIp) are effective adjuncts to antipsychotic medication and contribute to reductions in relapse, rehospitalisation and caregiver burden (Pilling et al., Reference Pilling, Bebbington, Kuipers, Garety, Geddes and Orbach2002; Pharoah et al., Reference Pharoah, Mari, Rathbone and Wong2010; National Institute of Health Care and Excellence, 2014; Keepers et al., Reference Keepers, Fochtmann, Anzia, Benjamin, Lyness, Mojtabai, Servis, Walaszek, Buckley, Lenzenweger, Young, Degenhardt and Hong2020). Accordingly, international clinical guidelines recommend FIp as an evidence-based component of comprehensive care for psychotic disorders (National Institute of Health Care and Excellence, 2014; Keepers et al., Reference Keepers, Fochtmann, Anzia, Benjamin, Lyness, Mojtabai, Servis, Walaszek, Buckley, Lenzenweger, Young, Degenhardt and Hong2020; American Psychiatric Association, 2021). The core components of FIp include psychoeducation, problem-solving skills and communication skills. Unfortunately, even in well-resourced countries, few families with a loved one experiencing a serious mental illness have received a FIp (Turkington et al., Reference Turkington, Gega, Lebert, Douglas-Bailey, Rustom, Alberti, Deighton and Naeem2018). When offered, they most commonly consist of psychoeducation about psychosis and indicated treatments but omit crucial skill-building to support improved communication, problem-solving and coping strategies. Despite their efficacy, interventions developed in high-income, Western contexts may not directly translate to LMICs without cultural adaptation. Failure to adapt psychosocial interventions risks reducing their acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness in local settings (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Blank, Vaswani-Bye, Shepard, Buckland, Hardy and Turkingtonn.d.; World Health Organization, 2008; Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021). Thus, adapting interventions to align with local sociocultural norms, languages and service-delivery systems is critical to ensuring their impact in LMICs.

To address the unmet need for comprehensive psychoeducation and skills training, co-authors DT, KH and SK co-developed a structured, carer-clinician co-delivered intervention based on cognitive behavioural theoretical principles and techniques. The intervention, called Psychosis Recovery by Enabling Adult Carers at Home (Psychosis REACH) (Turkington et al., Reference Turkington, Gega, Lebert, Douglas-Bailey, Rustom, Alberti, Deighton and Naeem2018; Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021) uses a task shifting approach recommended by the World Health Organisation (World Health Organization, 2008). Psychosis REACH is designed to prepare carers for skill-building and behavioural change through recovery-oriented psychoeducation about psychosis, guided self-care strategies, and practical cognitive-behavioural techniques for supporting their loved one’s management of psychotic symptoms. Psychosis REACH was developed specifically to remediate the poor penetration of evidence-based FIp within routine care settings by enabling delivery that is not dependent on clinical infrastructure or specialised clinical providers. Its task-sharing model allows trained laypersons (including family caregivers and peers) to deliver structured, skills-based support that complements, but does not rely on, clinician involvement. While the model can be implemented independent of a clinical setting – as has been done in community contexts in the United States – it is also flexible and can be adopted or adapted by clinical programmes seeking to enhance family engagement and support (e.g., Lean et al., Reference Lean, Benitah, Wakeham, Virtheim, Kopelovich and Hardyn.d.). Naturalistic trials found evidence that the training reduces caregivers’ symptoms of depression, anxiety and burnout; decreases expressed emotion (a communication style associated with relapse risk); enhances caregivers’ knowledge about psychosis; and reduces stigmatising attitudes toward psychosis and the prospects of recovery (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Blank, Vaswani-Bye, Shepard, Buckland, Hardy and Turkingtonn.d.; Turkington et al., Reference Turkington, Gega, Lebert, Douglas-Bailey, Rustom, Alberti, Deighton and Naeem2018; Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021; Lean et al., Reference Lean, Benitah, Wakeham, Virtheim, Kopelovich and Hardyn.d.). Gains were sustained at 4-month follow-up, although perceived self-efficacy in applying skills to encounters with their loved ones diminished over time.

Because the intervention leverages global mental health strategies like task shifting and task sharing to mitigate the barriers associated with clinic-delivered care, the intervention may generalise well to LMIC contexts. Although other family interventions have been piloted in Pakistan with input from people with lived experience, these have not combined structured CBT-based skill-building with WHO-endorsed delivery models. The novelty of the current study lies in applying a validated cultural adaptation framework (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015) to an existing evidence-based FIp, Psychosis REACH, to evaluate its feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness for caregivers in Lahore, Pakistan. The specific adaptations for this study were informed by a previous qualitative study with patients, carers and staff at the centre (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Harris, Underwood, Thagadur, Padmanabi and Kingdon2013, Reference Rathod, Gega, Degnan, Pikard, Khan, Husain, Munshi and Naeem2018, Reference Rathod, Javed, Iqbal, Al-Sudani, Vaswani-Bye, Haider and Phiri2023; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Sajid, Naz and Phiri2023). Ca-REACH We set out to (1) apply an empirically validated cultural adaptation framework to Psychosis REACH, (2) evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of the culturally adapted intervention in Lahore, Pakistan, and (3) explore its preliminary effects on caregiver outcomes and care recipients’ psychiatric symptoms. We refer to this adaptation as Ca-REACH.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a two-phase investigation. In Phase 1, we co-developed cultural, linguistic and contextual adaptations of Psychosis REACH with local stakeholders in Lahore, Pakistan. In Phase 2, we conducted a single-arm feasibility trial to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary outcomes of Ca-REACH among Lahori caregivers of individuals with psychosis. Based on guidance for pilot and feasibility studies, a sample of 30 caregiver participants was considered adequate (Husain et al., Reference Husain, Chaudhry, Mehmood, Rehman, Kazmi, Hamirani, Kiran, Bukhsh, Bassett, Husain, Naeem and Husain2017; Lyles et al., Reference Lyles, Khan, Qureshi and Shaikh2023). This sample size also allowed for preliminary exploration of caregiver and service-user outcomes at baseline, post-training and 4-month follow-up. The follow-up assessment was employed to test whether the training resulted in sustained or delayed benefit to caregivers and to assess for any benefit to residents, which required a longer follow-up window for caregivers to be able to interact with their loved one following training. Ca-REACH. The research team consisted of international experts in cultural adaptation frameworks and processes, experts in the intervention under investigation and local psychologists and psychiatrists, who addressed language and cultural nuances, guided content dose and pacing and ensured participant comprehension.

Study centre

This single-centre study was conducted in the Department of Psychiatry at Fountain House Lahore, a leading mental health treatment and rehabilitation centre located in Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city and home to a predominantly Muslim population. The centre provides acute, subacute and long-term rehabilitation services and maintains approximately 400 inpatient beds across multiple levels of care. Most patients present with serious mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders.

Recruitment

Potential resident participants were eligible if they were residents of Fountain House Lahore with an ICD-11 chart diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, were over 18 years of age and had the capacity to provide informed consent. Caregiver participants were eligible if they self-identified as caregivers of residents at Fountain House Lahore who interacted with their loved ones for at least 10 h per week (Barrowclough and Tarrier, Reference Barrowclough and Tarrier1992). Additionally, caregivers needed to be over 18 years of age and have the capacity to consent. Participants were excluded if they were unable to participate due to poor availability, significant mental impairment, or substance use that would impact their ability to provide informed consent and fully engage in the study. Residents and caregivers who expressed an interest in the trial were approached by the study team to determine their eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study team provided a thorough explanation of the study and provided participant information sheets in Urdu to prospective participants. Participants were given sufficient time (>24 h) to read and understand the information before providing written consent to participate in the study.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Pakistan Psychiatric Research Centre, Ethics and Review Committee (Ref: PPRC/2021/PRCAFIP 2021), with research governance approval secured at the Fountain House, Lahore. Participant confidentiality was maintained through the anonymisation of data and stored in password-secure computers. Only individuals who provided explicit, written informed consent were enrolled in the study. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time without providing reason, nor impacting their treatment at Fountain House Lahore.

Intervention

Psychosis REACH is comprised of three core elements: (1) recovery-oriented psychosis psychoeducation; (2) cognitive, behavioural, and complementary techniques aimed at enhancing caregiver self-care and reducing the social isolation associated with caregiving; and (3) Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for psychosis (CBTp)-informed communication, coping and problem-solving skills, collectively known as the FIRST skills. The intervention is delivered in a hybrid synchronous-asynchronous format (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Blank, Vaswani-Bye, Shepard, Buckland, Hardy and Turkingtonn.d.) and is co-facilitated by clinician experts and family peers (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Vaswani-Bye, Monroe-DeVita and Buckland2020; Vaswani-Bye et al., Reference Vaswani-Bye, McCain, Blank, Tennison and Kopelovich2024). The core Psychosis REACH intervention consists of 5 h of asynchronous didactic content facilitated by an expert in psychosis, 3 h of family, peer and clinician co-facilitated role plays and optional follow-up skills coaching by a peer. The adapted intervention, described below, was delivered in a group setting and facilitated by a local psychologist. The digital platform was considered impractical due to local internet inaccessibility; instead, the local clinician was favoured due to her on-site availability, credibility and fluency in the local language and cultures.

Cultural adaptation

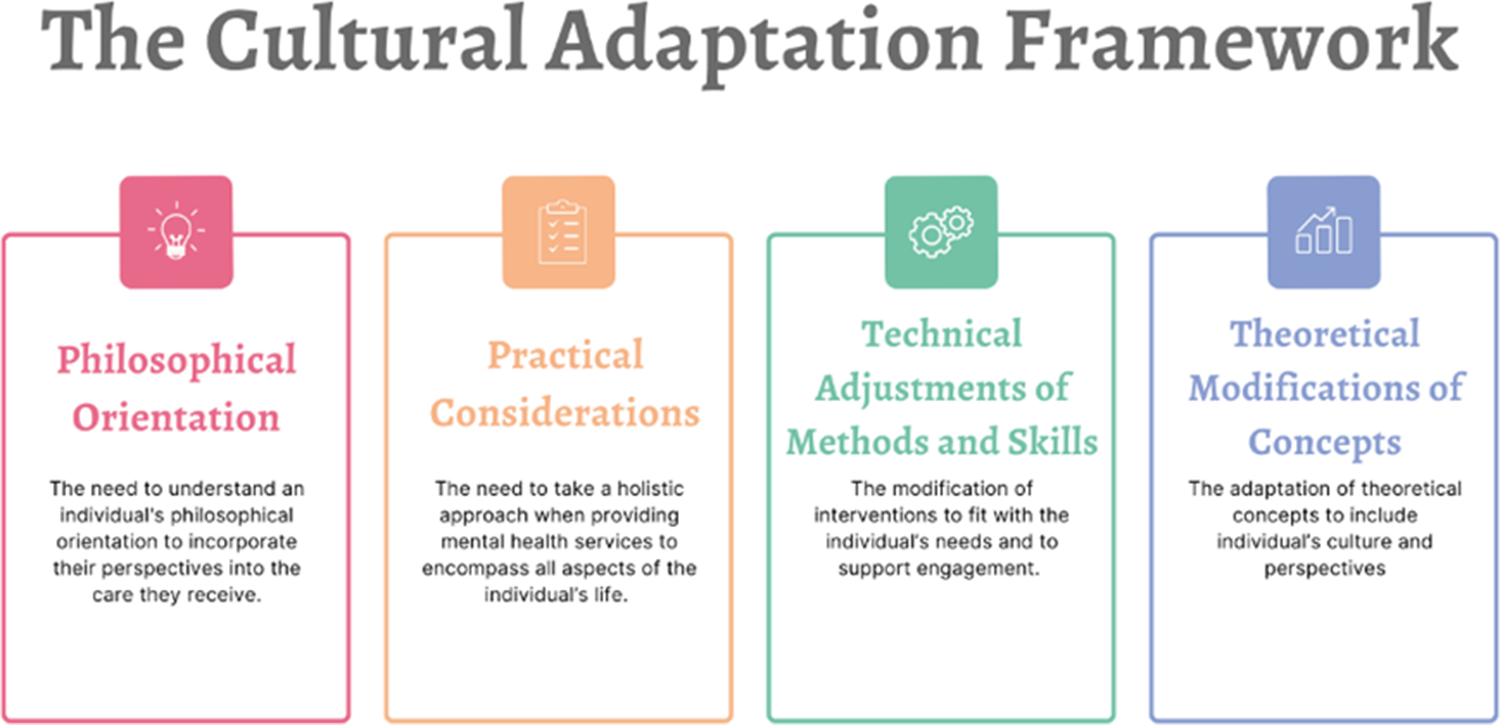

Adapting evidence-based interventions to fit the needs of individuals from diverse ethnic, spiritual and cultural backgrounds requires a holistic approach that incorporates cultural understanding. Accordingly, Rathod and colleagues have developed an evidence-based cultural adaptation framework that has been evaluated for use in diverse populations (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015). We utilised this framework to adapt the Psychosis REACH intervention content and modalities to support local uptake among a predominantly Muslim population in Lahore. As depicted in Figure 1, the framework has four core domains of adaptation–philosophical orientation, practical considerations, technical adjustments and theoretical modifications.

Figure 1. The cultural adaptation framework.

In addition, specific adaptations to Psychosis REACH were largely informed by a prior study conducted in Pakistan, which explored views and opinions of mental illness, particularly psychosis and interventions (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Javed, Iqbal, Al-Sudani, Vaswani-Bye, Haider and Phiri2023). Specific examples of adaptation made to each of the four domains of adaptation are delineated in Supplemental Table 1. Adaptations to the philosophical aspects of the intervention attempt to account for the variable worldview and life perspectives across individuals, communities and cultures that influence perceptions of health and illness, help-seeking behaviours, interactions with services and professionals, and treatment goals. The adaptation process sought to align the intervention, including the causal models for psychosis embedded within psychoeducation, with the cultural and spiritual beliefs of the study population. Local clinicians recommended a number of adaptations to the practical aspects of the intervention, such as the language, approach to supervision and the integration of folk stories and Quranic verses to support uptake. Clinicians were attuned to how factors such as employment, housing, justice and social welfare policies impact the experiences of the Muslim Lahori population and were uniquely poised to address these issues as needed. Technical adjustments to the mode and manner of interactions or interventions, as well as the setting, were made to enhance the therapeutic alliance and support engagement. For example, in-person, interactive delivery of educational content by a local psychologist was preferred to the recorded didactics of the foreign expert. Coping and communication strategies were aligned with local Islamic practices. Finally, the adaptation process included alterations to metaphors, analogies and constructs introduced in the intervention to optimise cultural resonance. Given the diverse ways in which culture influences both patients and clinicians, an individual-centred approach was employed during our adaptation process to explore underlying difficulties and presentations. This approach allowed for a more personalised and culturally sensitive engagement with each individual.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes: Feasibility and acceptability

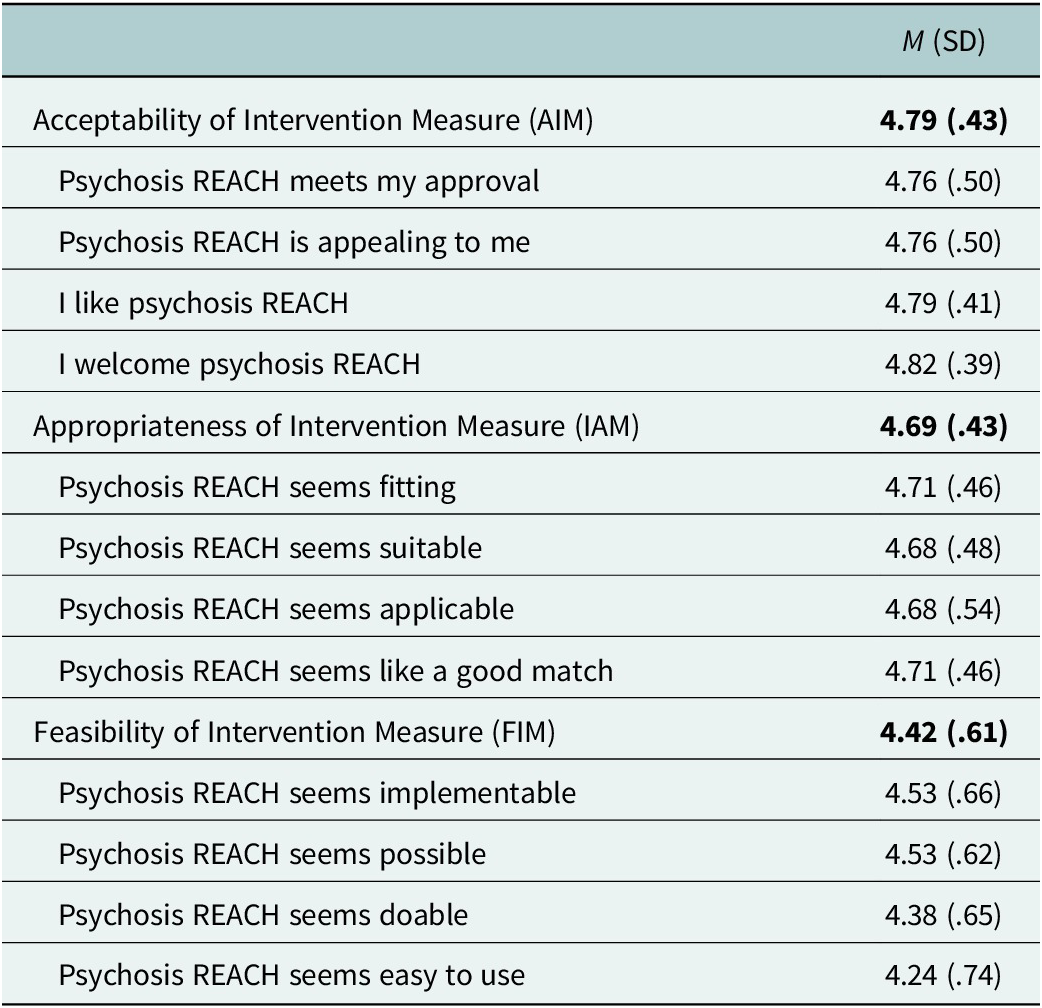

The primary aim of this study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of Ca-REACH in preparation for a fully-powered trial. Feasibility was operationalised as the proportion of eligible caregivers who enrolled, the proportion who completed post-test and follow-up assessments, session attendance and the percentage of participants providing full data across timepoints. Acceptability, feasibility and appropriateness were further assessed with validated self-report instruments. Participants completed the 4-item Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM), Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM) and Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM), each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (Weiner et al., Reference Weiner, Lewis, Stanick, Powell, Dorsey, Clary, Boynton and Halko2017). Higher scores reflected more positive perceptions of the intervention. These constructs, as delineated by Proctor and colleagues (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011), are leading indicators of implementation success and precursors to broader service outcomes, including efficiency, safety, effectiveness, equity and patient-centeredness.

Secondary outcomes: Caregiver and clinical variables

To enable comparison with prior Psychosis REACH evaluations and to explore potential clinical impact, we also assessed caregiver and service user outcomes. Caregivers completed surveys at three timepoints: pre-training (1 month before), post-training (immediately after) and follow-up (4 months post-training). The pre-training survey included demographics, psychiatric characteristics of the care recipient (e.g., diagnosis, lifetime hospitalisations), caregiver’s relationship to the individual with psychosis and level of involvement in care.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS is a 14-item scale designed to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms in both clinical and non-clinical populations (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983). The HADS has been validated in studies conducted in Pakistan (Imran et al., Reference Imran, Bhatti, Haider, Azhar, Omar and Sattar2010; Arshad et al., Reference Arshad, Qaider and Adil2011; Husain et al., Reference Husain, Khoso, Renwick, Kiran, Saeed, Lane, Naeem, Chaudhry and Husain2021) and is available in Urdu. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, with varying anchors per item. Anxiety and depression subscales are calculated separately: the anxiety score is the sum of odd-numbered items and the depression score is the sum of even-numbered items. Subscale scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater severity of anxiety or depression.

The Urdu version of Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing Scale is an 18-item self-report measure that assesses psychological well-being across six dimensions; the translated version has demonstrated good reliability and validity in a sample of Pakistani adults (Jibeen and Khalid, Reference Jibeen and Khalid2012). Because the PWB subscales have shown low-to-modest reliability – likely reflecting both the multidimensionality of the construct and the limited number of items per subscale (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Ploubidis, Huppert, Kuh and Croudace2009) – previous scholars have recommended using the total psychological well-being score (Garcia and Siddiqui, Reference Garcia and Siddiqui2009), which was adopted in the current study. The scale reflects a view of well-being as more than just the absence of mental illness, emphasising positive self-perception, relationships and life satisfaction.

CBT skill development

Caregivers rated their competencies on a 12-item self-report scale assessing each of the FIRST skills (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all comfortable/Not at all familiar; 5 = Expert). A total competency score was calculated by summing the scores across all 12-items. Competency scores for each of the five skill domains (e.g., Fall back on the relationship, Inquire curiously, Review the information, Skill building and Try it out) were also calculated.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scales (PANSS)

The PANSS is a 30-item clinician-rated instrument designed to assess the severity of schizophrenia symptoms (Kay et al., Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler1987). It includes three subscales: positive symptoms (such as hallucinations and delusions), negative symptoms (such as flat affect and avolition) and general psychopathology, which captures the overall severity of illness. Each item is rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Developed to provide a comprehensive and reliable measure of symptom severity, the PANSS has been validated across diverse settings and populations and is widely regarded as the gold standard for the assessment of psychosis treatment efficacy (Opler et al., Reference Opler, Yavorsky and Daniel2017). The Urdu version was validated in clinical research conducted in Pakistan (Habib et al., Reference Habib, Dawood, Kingdon and Naeem2015; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Saeed, Irfan, Kiran, Mehmood, Gul, Munshi, Ahmad, Kazmi, Husain, Farooq, Ayub and Kingdon2015) making it a reliable tool for evaluating psychotic symptoms in this population.

Assessment procedures and measure adaptation

Independent assessors conducted assessments at baseline, post-intervention and at 4 -month follow-up. These raters were trained in the administration of the Urdu version of the PANSS, Psychological Wellbeing Scale and HADS. To maintain data integrity, raw scores were entered by independent study personnel, minimising potential bias and ensuring the accuracy of the data collected. For measures not previously available in Urdu, a rigorous forward–backward translation process was used, guided by published standards for adapting self-report instruments (Beaton et al., Reference Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin and Ferraz2000) Translations were reviewed by community members in Lahore to ensure cultural appropriateness and reading-level suitability.

Analytic strategy

Data were analysed using SPSS version 29. Prior to hypothesis testing, data were screened for normality, missingness and outliers. Scale reliability for all self-report measures was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients to ensure internal consistency within the study sample. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations and correlations among study variables, were computed. Subsequent analyses examined changes in outcomes from baseline to post-intervention and 4-month follow-up using paired samples t-tests for outcomes assessed at two time points one-way repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for outcomes assessed at three time points. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were employed to assess specific changes between assessment intervals. Bonferroni-adjustments were used when conducting post hoc pairwise comparisons to account for potential Type 1 error inflation, yielding an adjusted alpha level of .017.

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Given the robustness of repeated measures ANOVA and paired-samples t-tests to deviations from normality, minor violations were deemed acceptable. Sphericity was tested using Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity, and when this assumption was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction (Greenhouse and Geisser, Reference Greenhouse and Geisser1959) was applied to reduce the likelihood of committing a Type 1 Error. All continuous measures were screened for univariate outliers (values >3 interquartile ranges from the quartiles) prior to analysis. A p-value less than .05 was considered indicative of statistical significance, except for post hoc pairwise comparisons, for which a Bonferroni-adjusted p-value of .017 was used. Listwise deletion was used to manage missing data.

Results

Demographics

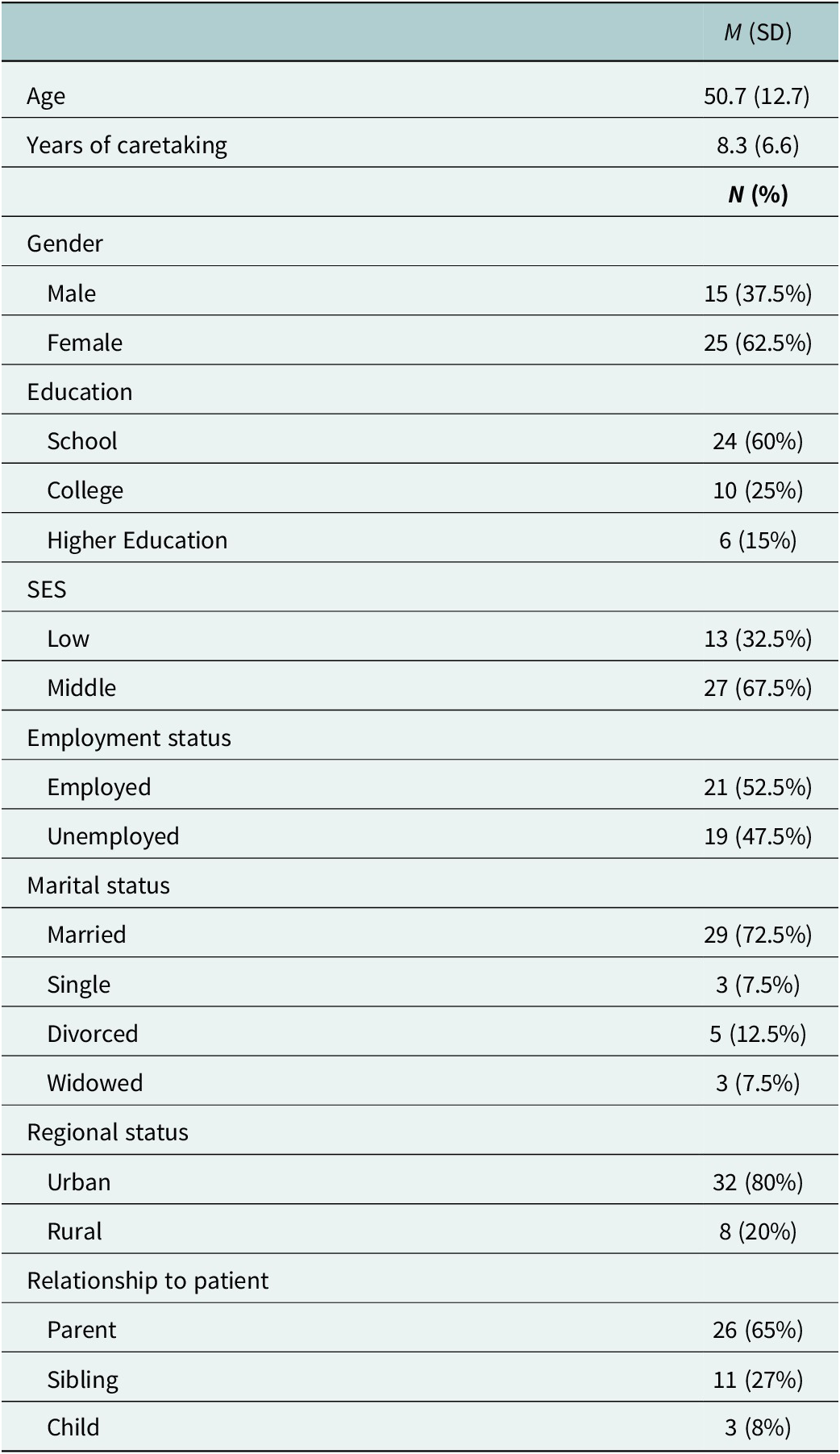

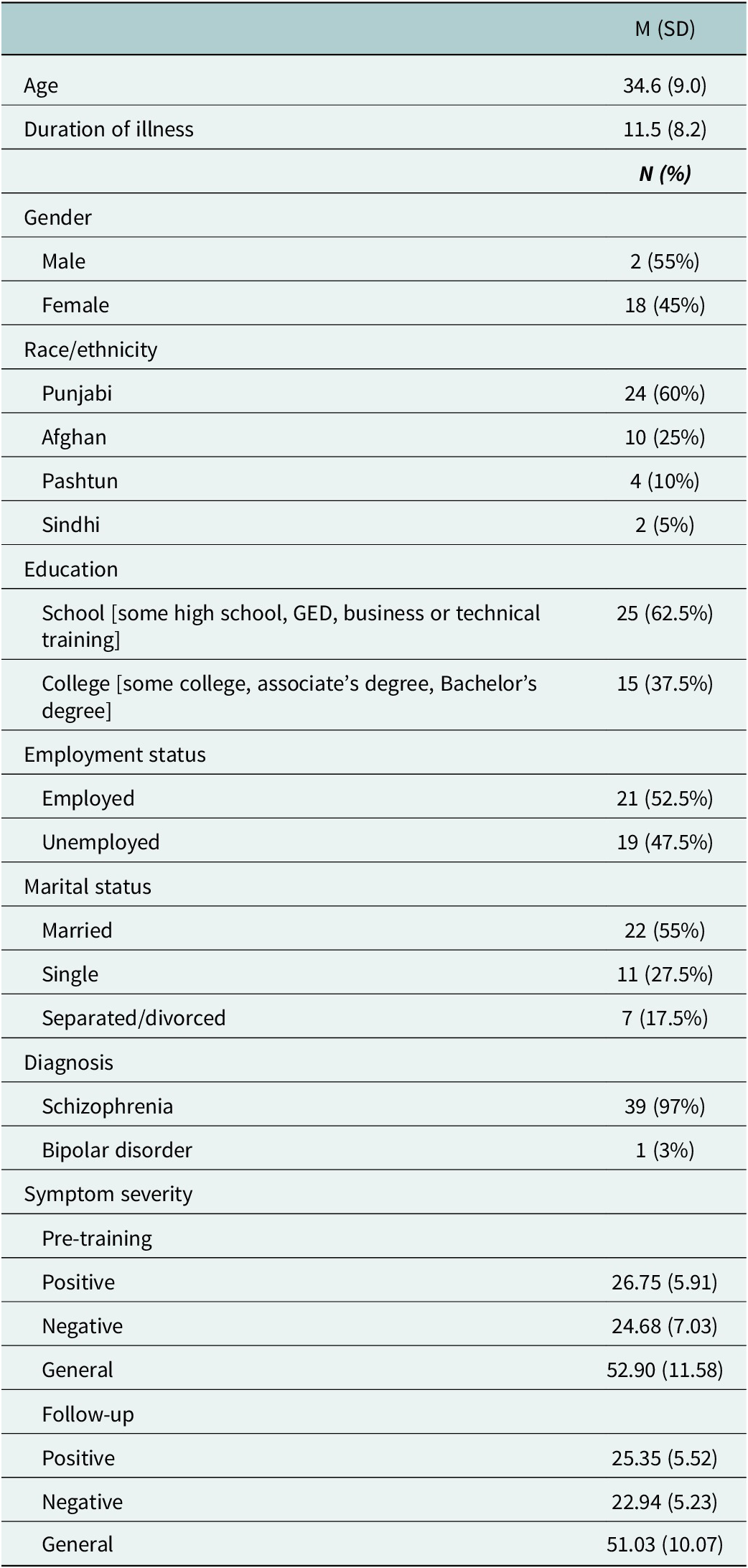

All 40 caregiver-resident dyads who were invited to participate in the study consented (see consort diagram, Supplemental Table 2). Demographic details are presented in Table 1 for caregivers and Table 2 for resident-participants. Caregivers were predominantly Punjabi (67%), parents (65%) and reported a wide range of caregiving durations (range = 1 – 28 years, M = 8.3, SD = 6.6). Most residents were male (55%), diagnosed with schizophrenia (97%), with an average duration of illness of approximately 11.5 years.

Table 1. Caregiver demographics (N = 40)

Table 2. Residents’ demographics (N = 40)

Outcomes

Feasibility of culturally adapted psychosis REACH

Feasibility was demonstrated across several process indicators. All 40 caregiver-resident dyads consented to participate (100% recruitment rate). Retention among caregivers remained high throughout the intervention period. Caregiver attendance rate across all intervention sessions was 96.5%. Assessments were successfully conducted at three time points (baseline, post-intervention and at four months follow -up period), confirming procedural feasibility. Data completeness among patient participants was moderate, with 85% (n = 34) providing full PANSS data at both baseline and 4-month follow-up. Table 3 presents the means and standard deviations for the perceived feasibility (FIM), acceptability (AIM) and appropriateness (IAM) of Ca-REACH; mean scores exceeded the conventional benchmark of 4.0 on each of the three scales.

Table 3. Acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of culturally-adapted psychosis REACH

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

Baseline Cronbach’s α coefficients for the HADS anxiety and depression subscales were .61 and .55, respectively. With questions worded in the opposite direction from the majority of the subscale (e.g., “I can sit at ease and feel relaxed,” “I feel as if I am slowed down”) removed, Cronbach’s α coefficients were larger (.81 and .72, respectively). We report results using the more reliable version of each subscale. Results using the full subscales can be found in supplemental materials (Supplemental Table 3).

Anxiety subscale

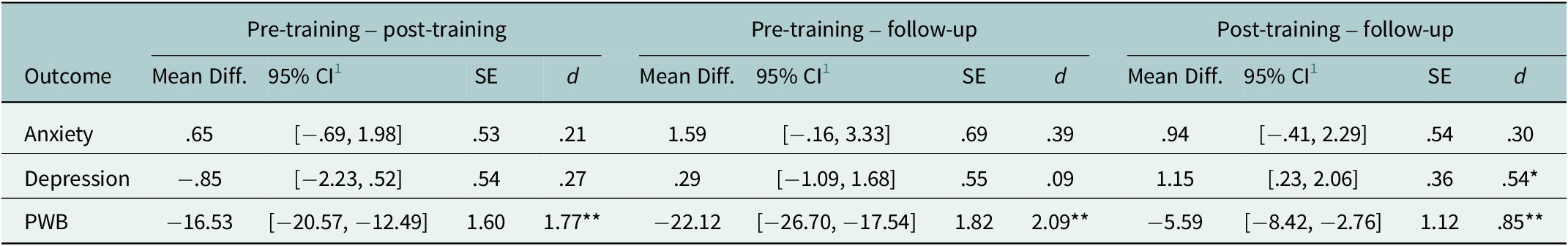

Normality was violated at pre-training (W = .92, p = .015), post-training (W = .94, p = .046) and follow-up (W = .91, p < .010). Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant, χ 2(2) = 4.79, p = .091. No univariate outliers were identified. The repeated measures ANOVA was statistically significant, with a slightly larger effect size, F(2, 66) = 3.66, p = .031, ηp 2 = .100. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a non-significant decrease in anxiety over time (see Table 4).

Table 4. One-way repeated measures ANOVA: post hoc pairwise comparisons

1 Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons; PWB = Psychological Wellbeing.

* p < .017 (Bonferroni adjusted alpha level); **p < .001; d = Cohen’s d.

Depression subscale

The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated a violation of normality at pre-training (W = .92, p = .021), post-training (W = .850, p < .001) and at follow-up (W = .809, p < .001). Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity was statistically significant, χ2(2) = 7.46, p = .024. No univariate outliers were identified. The repeated measures ANOVA was not statistically significant, F(1.66, 54.64) = 2.92, p = .072, ηp2 = .081, although post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed depression scores to be significantly lower at follow-up compared to post-training (see Table 4).

CBTp-informed FIRST skills

At follow-up, participants reported a moderate level of comfort in employing the FIRST skills (see Supplemental Table 4). Overall, the results indicate that participants generally felt comfortable using the FIRST skills, particularly in building and maintaining relationships and reviewing information shared by their loved ones. Participants reported slightly less comfort reported in the areas of skill building and trying out new skills.

Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)

Among the 40 caregiver-participants, 40 residents with a primary psychotic disorder consented to participate in research interviews, 34 of whom completed the PANSS at baseline and 4-month follow-up (see Table 2). The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated a violation of normality for the negative symptoms scale (W = .926, p = .024) and positive symptoms (W = .929, p = .030). No univariate outliers were detected. Paired-samples t-tests showed no significant changes in positive symptoms (t(33) = 1.57, p = .063, d = .27, 95% CI [−.08, .61]) or negative symptoms (t(33) = 1.41, p = .083, d = .24, 95% CI [−.10, .58]). However, we observed a significant decrease in general symptoms from pre-training to follow-up (t(33) = 1.72, p = .048, d = .30, 95% CI [−.05, .64]) and in PANSS total scores (t(33) = 2.95, p = .003, d = .51, 95% CI [.15, .86]).

Psychological wellbeing scale

PWB Cronbach’s α at baseline was .63. Consistent with prior recommendations, analyses used the total score rather than individual subscales. The assumption of normality was met at each timepoint. Mauchly’s test of sphericity was statistically significant, χ 2(2) = 9.29, p = .010. No univariate outliers were identified. The repeated measures ANOVA was statistically significant, F(1.60, 52.72) = 111.42, p < .001, ηp 2 = .771, with pairwise comparisons revealing a progressive increase in psychological wellbeing over time (see Table 4).

Discussion

We reported on a systematic cultural and contextual adaptation and single-arm feasibility trial of a CBTp-informed FIp, Psychosis REACH. The intervention has previously been delivered via a hybrid synchronous-asynchronous format to enhance accessibility (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021). In the context of Lahore, Pakistan, we delivered the intervention face-to-face, as online delivery proved to be a barrier to access due to low digital literacy, limited access to reliable internet, participant preferences for face-to-face interaction to enhance engagement and support, and limited English proficiency. The treatment adaptation reported here is directly responsive to calls for research that includes culturally-, geographically-, relationally- and gender-diverse caregivers supporting individuals with psychosis (Chakrabarti, Reference Chakrabarti2013). Whereas previous investigations of Psychosis REACH have been conducted exclusively in North America, this trial takes place in a LMIC context and was preceded by cultural and linguistic adaptation. Moreover, prior studies have highlighted the need to investigate the effects of FIp on the loved ones with psychosis, particularly to assess whether FIp delivered independent of the individual’s treatment plan is indicated. Although our sample size is small and we cannot draw causal conclusions without a randomised controlled trial, our findings suggest that FIp, like Psychosis REACH, can benefit both caregivers and their loved ones diagnosed with a serious mental illness. Additionally, our adaptation process leveraged the credibility of local clinicians to deliver culturally resonant information and skills training that met the needs, preferences, strengths and constraints of the local population. The study also benefited from partnerships between administration, clinicians and researchers affiliated with the clinical site, as well as collaboration with treatment developers and adaptation framework developers. Regular study team meetings ensured efficient and well-informed decision-making throughout the trial.

This feasibility study makes a valuable contribution to a sparse evidence base. A systematic review of the effectiveness and implementation readiness of psychosocial interventions for psychotic disorders in South Asian populations found that the family/caregiver intervention was among the intervention types showing significant reductions in symptoms, alongside community-based and CaCBTp programmes (Morillo et al., Reference Morillo, Lowry and Henderson2022; Lyles et al., Reference Lyles, Khan, Qureshi and Shaikh2023). Similarly, Morillo, Lowry and Henderson’s review of FIp in LMICs identified 27 studies with key therapeutic elements including psychotherapy, systemic approaches and task sharing with culturally adapted strategies like sustained family engagement. Despite heterogeneity and high risk of bias in many studies, interventions consistently demonstrated positive impacts across family-related outcomes, thus supporting integration of family psychosocial care into community mental health services in LMICs and addressing urgent gaps in psychosis treatment (Morillo et al., Reference Morillo, Lowry and Henderson2022).

Given this guidance and the scarcity of literature in this area, our systematic cultural adaptation of Psychosis REACH coupled with promising findings from a rigorous feasibility trial represent a significant advancement in the development of FIp in low- and middle-income predominantly Muslim countries. Our findings align with those of Husain and colleagues (Husain et al., Reference Husain, Khoso, Renwick, Kiran, Saeed, Lane, Naeem, Chaudhry and Husain2021), who reported similarly promising indicators of acceptability and feasibility in a randomised study of a culturally adapted family intervention among 29 participants. This study thus marks an important step in extending the research on culturally adapted FIp in resource-constrained settings.

Limitations

Despite the promising findings, results from this feasibility trial should be interpreted with caution. This was a single-centre, uncontrolled study with a small sample size, which limits generalisability. Although such characteristics are typical of feasibility research, they nonetheless constrain the strength of conclusions that can be drawn. Previous Psychosis REACH studies have shown that caregivers’ confidence in applying learned skills diminishes without ongoing, longitudinal coaching (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021). This observation informed the inclusion of trained family peers in the original intervention model (Kopelovich et al., Reference Kopelovich, Stiles, Monroe-DeVita, Hardy, Hallgren and Turkington2021; Naeem et al., Reference Naeem, Sajid, Naz and Phiri2023). In contrast, the current study included only a 4-month follow-up and did not incorporate peer-led skill rehearsal, precluding examination of longer-term skill retention. Additionally, the translated anxiety and depression subscales demonstrated low internal consistency in our sample when all items were retained, despite prior studies reporting acceptable reliability and validity for these Urdu versions (Mumford et al., Reference Mumford, Tareen, Bajwa, Bhatti and Karim1991). This discrepancy may reflect weak correlations between positively and negatively worded items in this cultural context. Finally, although participants reported high satisfaction and perceived benefit from Ca-REACH, feedback was global in nature, limiting our ability to identify which intervention components were most impactful. Future research incorporating qualitative methods and extended follow-up periods will be important to clarify the mechanisms driving benefit and the sustainability of skill use over time.

Implications for adaptations

We introduced technological, cultural and linguistic adaptations to respond to the contexts of the target population. Future adaptations of Psychosis REACH or similar interventions should consider alternative delivery methods that align with local needs, such as face-to-face sessions in settings where online delivery is impractical. Moreover, the study’s findings suggest that more detailed feedback mechanisms should be incorporated into future trials to identify the most impactful components of the intervention.

Conclusion

This study represents a significant step forward in the adaptation and implementation of family interventions for psychosis in LMICs, specifically within a predominantly Muslim population in Pakistan. Ca-REACH was found to be feasible, acceptable and appropriate. The high enrolment and retention rates, alongside positive outcomes in caregiver confidence and patient symptomatology, provide preliminary evidence that family involvement in psychosis care can be beneficial even in resource-constrained settings. Acknowledging the limitations, further research is warranted to confirm these findings in a phase 2 trial, exploring the long-term impacts of the intervention on both caregivers and residents. Finally, the study underscores the importance of cultural adaptation, the potential of family-centred care models and the need for continued innovation in the delivery of mental health interventions in diverse global contexts.

Abbreviations

- AIM

-

Acceptability of Intervention Measure

- ANOVA

-

Analysis of Variance

- Ca-REACH

-

Culturally adapted Psychosis REACH

- CBTp

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychosis

- FIM

-

Feasibility of Intervention Measure

- FIp

-

Family Interventions for psychosis

- FIRST Skills

-

Fall back on the relationship, Inquire curiously, Review the information, Skill building, Try it out

- HADS

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IAM

-

Intervention Appropriateness Measure

- LMICs

-

Low and Middle-Income Countries

- PANSS

-

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- Psychosis REACH

-

Recovery by Enabling Adult Carers at Home

- PWB

-

Psychological Wellbeing Scale

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10107.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10107.

Data availability statement

The de-identified datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

AJ, IH and RI would like to express their sincere gratitude to Medical Superintendent Dr. Syed Imran Murtaza, Ms. Ayesha Imran Murtaza, the staff and the members of Fountain House. PP acknowledges Kath Elliot from Hampshire & Isle of Wight Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust for their invaluable support in facilitating this project. SLK and AVB wish to acknowledge the growing global network of Psychosis REACH caregivers, Psychosis REACH Family Ambassadors and the University of Washington Family & Caregiver Advisory Board for their many contributions to the Psychosis REACH intervention and adaptations.

Author contribution

Writing-Original Draft: Led by SLK, with contributions and critical review from all authors. Writing – Review & Editing: All authors reviewed and provided substantive edits to the manuscript. SLK contributions included conceptualization, methodology, project administration and supervised data analyses. SR and PP developed cultural adaptation framework; input on adapted intervention administration; and supported data analyses, interpretation and visualization. AVB made significant contributions to subsequent iterations of the intervention, including CA-REACH. JMB contributions included data analysis and visualization and assistance with data curation, with assistance from VS, who also provided significant support in manuscript preparation. RI, IH and AJ supported project administration and site supervision, participant recruitment, material translation, cultural adaptations, intervention delivery and data collection.

Financial support

This study was funded by an anonymous foundation grant awarded to the first author (SLK).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this project.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Pakistan Psychiatric Research Centre, Ethics and Review Committee (Ref: PPRC/2021/PRCAFIP 2021) with research governance approval secured at the Fountain House Lahore.

Comments

Dear Drs. Bass and Chibanda,

I am pleased to submit our manuscript entitled “Cultural Adaptation and Preliminary Evaluation of the Psychosis REACH Family Intervention in Pakistan” for consideration for publication in Global Mental Health.

This study describes the cultural adaptation and pilot evaluation of Psychosis REACH (Recovery by Enabling Adult Carers at Home), a family intervention for psychosis (FIp) designed for delivery outside of traditional clinical settings. Our team adapted this intervention using a validated framework in collaboration with stake-holders at Fountain House Institute for Mental Health in Lahore, Pakistan. The adapted intervention, CA-REACH, was tested for feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness, and was associated with promising improvements in caregiver and patient outcomes.

Given Global Mental Health’s focus on culturally responsive mental health interventions, implementation science in LMICs, and innovations to reduce the treatment gap, we believe this manuscript is a strong fit. It con-tributes to the growing but still limited body of research on psychosocial interventions for psychosis in low-resource settings, highlighting the role of community-based, task-shifted strategies.

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by any other journal. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and declare no competing interests.

Thank you for considering our work for publication in Global Mental Health. We hope it will be of interest to your readership and contribute to global efforts to expand equitable access to mental health support for individuals with psychosis and their families.

Sincerely,

Dr. Sarah Kopelovich, PhD, ABPP

Associate Professor | Professorship in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis

SPIRIT Center and Center for Mental Health, Policy, and the Law

Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences

University of Washington School of Medicine

Phone: +1-206-221-1218 | Email: skopelov@uw.edu

On behalf of all co-authors.