Introduction

Public organizations increasingly span boundaries, resist standardized solutions, and face complex, difficult-to-define policy challenges (Christensen and Lægreid Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011; Head Reference Head2022). These conditions are argued to require design processes built on learning, inclusion, and reflexive adaptation – and yet how such capacities unfold in practice remains less clear, particularly in highly institutionalized organizations (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing2017; Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Coban and Bali2021). While theory suggests that complex, boundary-spanning problems require reflexive learning and inclusion for organizations to address them thoroughly, this study examines how these capacities actually unfold in practice, without presuming them as normative ideals (Fischer Reference Fischer2003; Yanow Reference Yanow and Schatz2009). The challenges of engaging in reform and organizational change often involve complex elements of organizational problem-solving (Christensen and Laegreid Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011; Snowden and Boone Reference Snowden and Boone2007).

In civilian bureaucracies, rule-bound accountability systems condition how organizations operate (Peters Reference Peters2019), whereas in risk-oriented organizations, hierarchical structures and strong socialization shape tendencies toward doctrine-based ways of working (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989; Soeters et al. Reference Soeters, Winslow, Weibull and Caforio2006). In both settings, organizational logics shape the possibilities for reflexive learning and inclusive design practices, which condition how adaptive approaches unfold (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing2017; Christensen and Laegreid Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011). This raises the broader question of how organizational logics shape learning, inclusion, and adaptive practices in policy design.

To explore this question empirically, the paper focuses on the Danish Armed Forces, a highly structured, risk-oriented organization under significant reform pressures. Their role in administrative and reform-oriented policy processes provides an analytically informative case for examining how governance mechanisms shape learning, inclusion, and adaptation (Soeters et al. Reference Soeters, Winslow, Weibull and Caforio2006). The Armed Forces play a central role in national policy implementation, making them a relevant case for understanding how hierarchical, risk-oriented public organizations handle administrative and reform-oriented challenges. This study examines how institutional logics shape learning, reflection, and adaptive practices in response to reform challenges, which differ in character from operational or crisis-oriented problems (Ansell and Gash Reference Ansell and Gash2008; March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989; Snowden and Boone Reference Snowden and Boone2007). While operational routines rely on clear roles, standardized doctrines, hierarchical problem-framing, and well-defined criteria for success, reform challenges are inherently emergent: requiring sensemaking, negotiation across contexts, iterative adaptation, and collaborative engagement across professional and organizational boundaries. By tracing how these capacities are shaped and constrained under strong institutional logics, the study highlights broader lessons for adaptive practices in hierarchical, risk-oriented public organizations (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing2017; Christensen and Lægreid Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011).

The article is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework, beginning with institutional theory to examine how organizational structures and governance logics shape the conditions for policy design. A discussion of collaborative policy design and the process demands of learning and inclusion follows. The methodology section outlines the case selection and qualitative data collection strategy. Next, the empirical analysis examines how governance mechanisms shape collaborative practices across three policy design stages. The discussion synthesizes the findings and identifies key governance traits and dynamics that help to explain policy design in risk-oriented organizational settings. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main contributions and suggests avenues for future research.

The role of institutions

Public organizations face institutionalized norms and assumptions that shape what is considered appropriate action, often creating conditions that influence whether learning, reflection, and adaptive practices can emerge (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989; Peters Reference Peters2019). These institutional patterns are not fixed rules; instead, they tend to guide organizational behavior, making some approaches more likely than others. Whether collaborative elements or inclusive problem-solving practices develop depends on the broader governance arrangements and embedded organizational logics in which policy design occurs (Hoppe Reference Hoppe2010). By highlighting these dynamics at the institutional level, this section sets up an analysis of how such logics interact with reform-oriented and administrative challenges in professionalized public organizations.

Institutional theory emphasizes how organizational behavior is influenced by enduring norms, formal rules, and commonly accepted understandings of legitimacy and appropriateness (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989; Peters Reference Peters2019). In public agencies, decision-making is structured by institutionalized expectations, such as which actions are considered viable or necessary, who is deemed legitimate to speak, and what forms of knowledge count (Howlett and Mukherjee Reference Howlett and Mukherjee2017). Patterns develop through repeated enactment and become embedded in routines, roles, and practices, creating conditions for responding to new demands and changed circumstances. Institutions thus shape outcomes, problem framings, and the procedural pathways through which issues are addressed.

Since the 1990s, research has shown that Western military organizations are characterized by strongly hierarchical structures, where authority is tied to rank and roles are clearly defined (Feaver Reference Feaver2003; Friesl et al. Reference Friesl, Sackmann and Kremser2011; Holmberg and Alvinius Reference Holmberg and Alvinius2019). These organizations often operate through a logic of obedience, loyalty, and risk control, reinforced through socialization, doctrine, and strong leadership norms (Cawkill Reference Cawkill2004; Moreno and Gonçalves Reference Moreno and Gonçalves2021). This institutional culture tends to prioritize command over dialogue, thereby limiting critical feedback and the integration of alternative expertise (Fragoso et al. Reference Fragoso, Chambel and Castanheira2019; Hedlund Reference Hedlund2013; Hutchison Reference Hutchison2013). These features are closely tied to the operational logic of military organizations, where uncertainty and risk require control, speed, and clear accountability (Dvir et al. Reference Dvir, Eden and Banjo1995; Shields and Travis Reference Shields, Travis, Heeren-Bogers, Esmerelda Kleinreesink, Moelker, van der Meulen and Beeres2020). Scholars increasingly distinguish between operational and administrative spheres in the military, each governed by distinct rationalities (Ydén Reference Ydén, Obling and Tillberg2021). While operational tasks demand decisiveness and control, administrative challenges, such as resource planning or cultural reform, require engagement, interpretation, and coordination across levels (Christensen and Lægreid Reference Christensen and Lægreid2007; Soeters et al. Reference Soeters, Winslow, Weibull and Caforio2006). When operational governance mechanisms are applied in administrative settings, tensions may emerge, and policy design practices can be influenced by logics constraining ownership, learning, and institutional adaptation (Christensen and Laegreid Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011).

Collaborative policy design

Policy implementation challenges in public administration have traditionally been associated with long implementation chains and street-level discretion (Lipsky Reference Lipsky2010; Pressman and Wildavsky Reference Pressman and Wildavsky1980). Recent research also suggests that the policy design phase has an important influence on implementation (Linder and Peters Reference Linder and Guy Peters1984), underscoring the need to understand how policies are formulated within their institutional and organizational contexts.

Policy design involves crafting goals, assumptions, rules, and tools to address specific policy problems (Howlett Reference Howlett2014; Ingram and Mann Reference Ingram and Mann1980). Traditional approaches emphasize expert-led planning, while newer perspectives, such as collaborative and design-thinking approaches, highlight participation, iteration, and responsiveness to diverse knowledge sources (Bason Reference Bason2014; Body and Terrey Reference Body, Terrey and Bason2014). These approaches are often applied to complex, poorly structured problems that resist standardized solutions or hierarchical control (Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Coban and Bali2021; Peters Reference Peters2018; Rittel and Webber Reference Rittel and Webber1973). Although often discussed as a normative ideal, collaboration can also be understood as a pragmatic response to uncertainty, especially when problem definitions or solutions are contested (Ansell and Gash Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Head Reference Head2022). Inclusive and reflective policy processes can enhance legitimacy, relevance, and shared ownership of policy solutions; however, institutional and organizational contexts can shape the feasibility of such processes in practice.

Although initially developed in networked and inter-organizational settings, recent research explores how collaborative principles can be applied within public organizations to address internal complexity in domains like education or local government (Bentzen Reference Bentzen2022). However, such practices may face constraints in risk-oriented organizations such as the military, where authority, loyalty, and role clarity are emphasized, shaping the space for collaborative capacities (Christensen and Laegried Reference Christensen and Laegreid2011; Soeters et al. Reference Soeters, Winslow, Weibull and Caforio2006). This raises questions about whether and under what conditions governance mechanisms can enable capacities such as learning, reflection, and inclusion during policy design.

This study adopts an exploratory approach to examine how governing mechanisms structure the unfolding of design work and how collaborative process demands (particularly learning and involvement) emerge and are shaped during policy design. These demands are treated as analytical lenses rather than normative benchmarks, providing a way to understand how military bureaucracies respond to complex administrative challenges. Rather than evaluating collaboration per se, the aim is to trace how institutional conditions shape the possibilities for reflective and inclusive design practices, setting the stage for the subsequent theoretical discussion.

Analytical framework

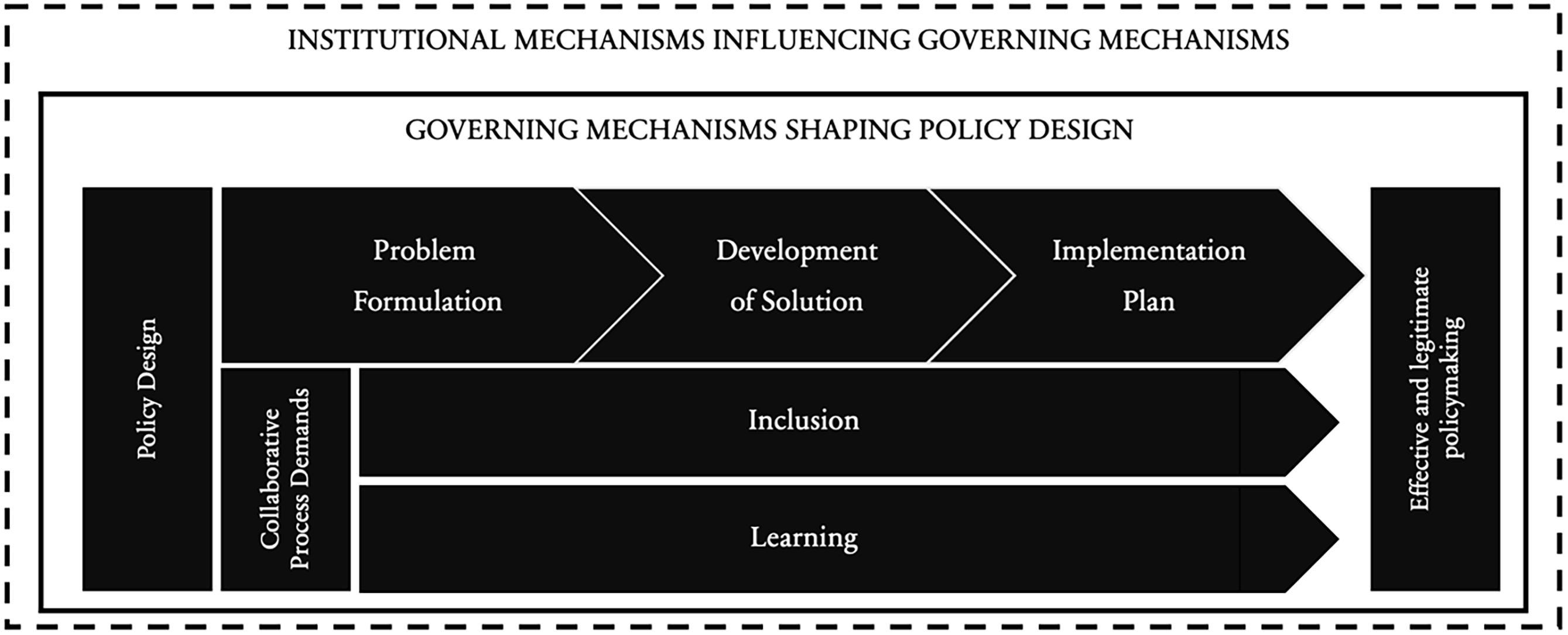

An analytical framework is developed to examine how governance structures shape administrative policymaking. Drawing on the outline of the institutional theory, governance research, and collaborative policy design, the framework focuses on how governance mechanisms, defined as institutionalized arrangements and logics that structure action and interaction, enable or constrain collaborative capacities in complex policy design (Howlett and Mukherjee Reference Howlett and Mukherjee2017; March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1989). Rather than presenting a normative model, it serves as a heuristic tool to trace how institutional conditions influence patterns of action and interaction (Bennett and McWhorter Reference Bennett and McWhorter2016).

For analytical purposes, policy design is conceptualized in three interconnected phases: (1) problem formulation, (2) solution development, and (3) implementation planning (Howlett Reference Howlett2019). Problem formulation concerns how the issue is framed and defined; solution development focuses on generating and selecting possible responses; and implementation planning involves translating the chosen solution into practical steps and responsibilities. Special emphasis is placed on problem formulation, particularly in the context of ill-structured problems where causes, goals, and appropriate responses are contested (Hoornbeek and Peters Reference Hoornbeek and Guy Peters2017; Rein and Schön Reference Rein and Schön2020). How a problem is framed shapes the trajectory of design by influencing assumptions, tool selection, and pathways forward. Design-oriented perspectives emphasize the value of exploring multiple framings and critically interrogating causal logics, as this can foster innovation and responsiveness while simultaneously reducing the risk of early lock-in or path dependency (Junginger Reference Junginger and Bason2014; Peters Reference Peters2021; Weick Reference Weick1995).

Collaborative process demands – learning and inclusion

Two key process demands – learning and inclusion – are used as analytical lenses to examine how hierarchical governance structures shape the unfolding of policy design. Rather than treating them as normative ideals, the study engages these concepts as pragmatic responses to policymaking under conditions of uncertainty and complexity (Head Reference Head2022; Mukherjee et al. Reference Mukherjee, Coban and Bali2021). They help to assess whether and how public organizations can reflect, adapt, and incorporate diverse insights throughout the design process.

Learning refers to collective processes in which actors make sense of policy problems, revisit assumptions, and reflect on potential solutions and consequences. It includes technical problem-solving and deeper interpretive work, such as rethinking goals in light of past experiences or emerging knowledge (Mezirow Reference Mezirow2000; Weick Reference Weick1995). When supported, learning creates space for reflection and adjustment before policies become locked into suboptimal paths (Hartley Reference Hartley2005; Mezirow Reference Mezirow2000). These processes depend on individual capability and governance environments that enable openness, dialogue, and frame-shifting – even in settings that emphasize hierarchy and control.

Inclusion involves actively engaging those with relevant experiences, perspectives, or implementation roles in shaping policy design. Inclusion is associated with improved decision quality and perceptions of fairness, ownership, and legitimacy (Weibel Reference Weibel2007). Even when outcomes are contested, actors are more likely to accept them if they feel heard and acknowledged (de Bruijn Reference de Bruijn2002). This internal dimension – how policy is received and enacted – is shaped by its content and by the degree of inclusivity and dialogue in the process. In hierarchical organizations, where the distance between decision-makers and implementers is substantial, inclusion becomes vital for feasibility and acceptance.

Military organizations offer a paradigmatic case of risk-oriented public bureaucracies. Designed for operational stability and accountability under uncertainty, they operate according to institutional logics that prioritize control, predictability, and role clarity. These features make them especially relevant for examining how internal governance mechanisms enable or constrain collaborative process demands, particularly learning and inclusion. In so doing, they provide a valuable lens for exploring broader challenges of adaptive governance in risk management institutions.

The aim is not to evaluate whether collaborative design works but to explore how governance mechanisms and institutional logics shape the conditions for learning and inclusion. These demands are analytically derived from the nature of complex policy challenges. Rather than seeking generalization, the goal is to generate situated insights into risk-oriented bureaucracies that govern administrative policymaking under structural constraints and how such restrictions may limit adaptability, ownership, and practical relevance in comparable contexts. Institutional theory examines how embedded norms and governance structures shape learning and inclusion during policy design (Heikkila and Gerlak Reference Heikkila and Gerlak2013). The goal is not to assess these institutions applying a normative yardstick, but rather to explore how they influence problem framing, participant legitimacy, and whether collaborative practices are necessary or disruptive.

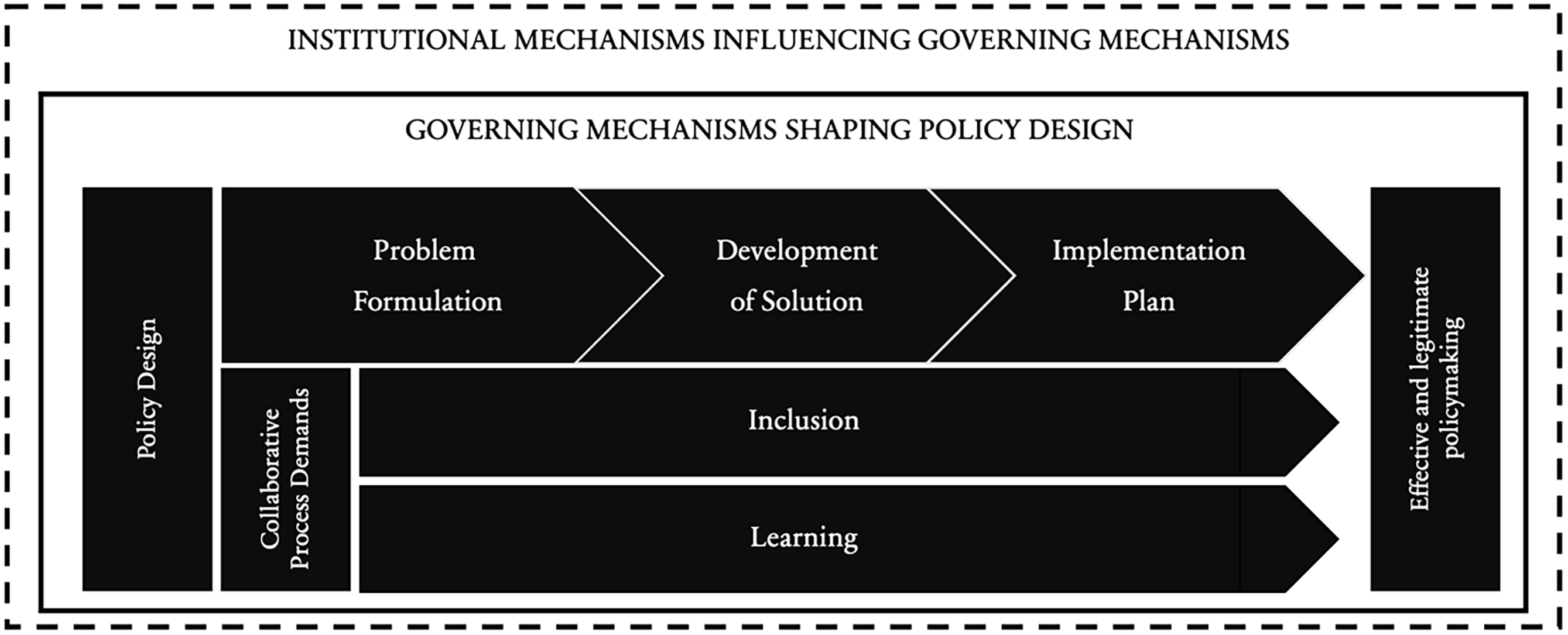

Figure 1 illustrates the framework used to examine how learning and inclusion are enabled or constrained through governing mechanisms, such as formal structures, accountability procedures, and institutional logics, across three phases of policy design.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework.

Source: author’s own illustration.

Understanding military policymaking through this lens contributes to broader debates in public administration by showing how institutional structures and governance mechanisms shape internal policy processes, particularly in administrative and strategic domains. As reforms increasingly push military organizations to strengthen internal governance and adaptive capacity, examining how institutional logics govern policy design becomes ever more critical.

Methods

A qualitative comparative case-study design was chosen to explore how policy design unfolds in a military organization and to examine how institutional logic shapes collaborative process demands within risk management contexts. The two cases were not selected for representativeness but rather for their contrasting organizational configurations and potential to illuminate governance dynamics under different structural conditions. Case A involved strong external visibility and cross-organizational involvement, while Case B was embedded in a more contained command structure. This contrast allows for a nuanced understanding of how organizational distance, actor constellations, and institutional expectations affect administrative policymaking.

The study traces how policy problems are recognized, framed, and translated into solutions, a process often carried out in informal ways (Béland and Howlett Reference Béland and Howlett2016). The aim is to explore how structural and institutional features enable or constrain learning and inclusion, not to assess policy effectiveness. The cases are treated as paradigmatic of risk-oriented bureaucracies where institutional mechanisms shape – not merely support – the conditions for collaboration (Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg2001). The interviews and observations focused on actor interactions and the institutionalized governance mechanisms that influenced possibilities for learning and inclusion across the design phases.

Case selection and method

The selected cases are drawn from the Danish Armed Forces. Denmark is a representative democracy with lengthy traditions for defense settlements with broad political support. In 2023, the Danish government and most of the Danish parliament agreed on a ten-year Defence Settlement encompassing more than US$20 billion in investments from 2024 to 2033 (The Danish Ministry of Defence 2023). The Danish Ministry of Defence is divided into eight agencies and three authorities. The Defence Command Denmark (DCD) is the largest agency, employing approximately 15,000 employees and providing the organizational context for this study. The military organization is traditionally described as hierarchical, leader-centric, and based on strong organizational socialization (Hutchison Reference Hutchison2013), which most likely influences the policy design processes. On the other hand, the public sector in Denmark is characterized by low power distances, high levels of social capital, and interpersonal trust (Morrone et al. Reference Morrone, Tontoranelli and Ranuzzi2009), which may influence policy design processes in favor of facilitating inclusive stakeholder collaboration. This contrast provides a relevant setting for examining how policy design processes are shaped under different institutional expectations, which is explored through two cases, described in the next section.

Empirical cases and analytical relevance

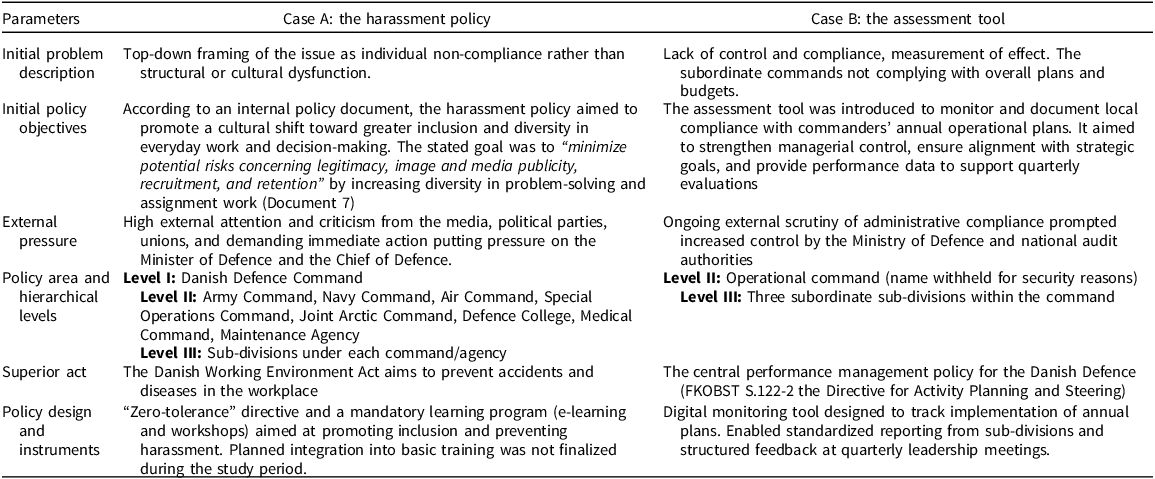

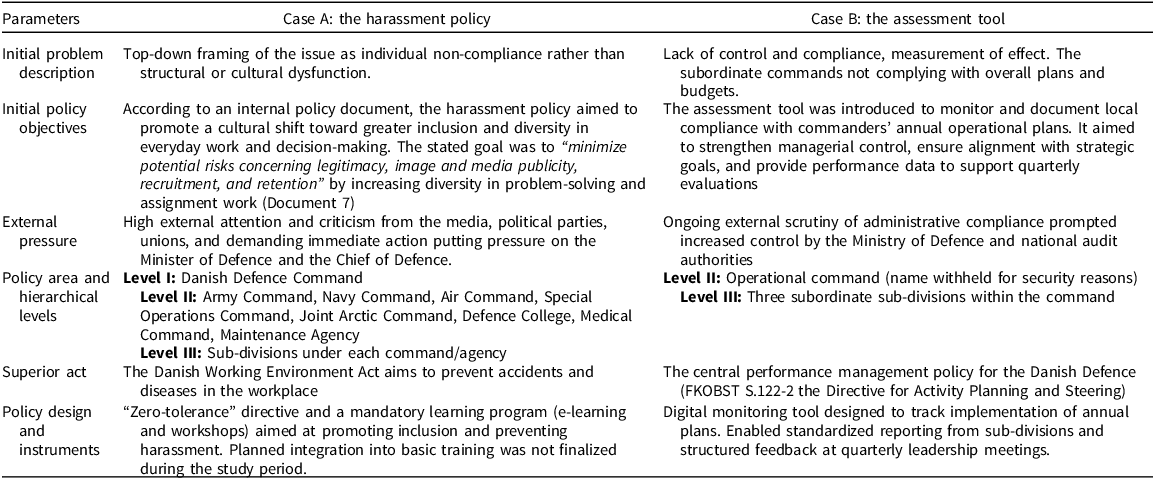

Case A concerns a reintroduced harassment policy following a public scandal that revealed systemic issues over two decades. Case B centers on a financial accountability tool introduced in response to criticism from the National Audit Office. In both cases, the top-level leaders expressed frustration with previous initiatives that failed to generate meaningful change, emphasizing the need for more reflective approaches. As both policies addressed persistent policy problems, they enabled the examination of how governance mechanisms shape the inclusion and learning of complex issues in different organizational configurations. The cases are introduced below, and further details are in Table 1.

Table 1. Policy cases overview

Source: author’s own compilation.

Policy Case A: the harassment policy

In June 2022, an investigative television program, In War and Harassment, exposed more than 20 years of continuous sexual harassment in the Danish Armed Forces. The show put the policy problem on the agenda, prompting the Chief of Defence of the DCD to call for renewed and more decisive action in the institutions of the Danish Armed Forces. In the program, the Chief of Defence condemned harassment, underlining that diversity and inclusion were essential for the organization’s success. It was further emphasized that the response to the harassment issue required a break from “normal ways of working” and called for a more serious and engaged approach across the organization; however, this ambition was accompanied neither by changes in governance arrangements nor expectations that could support such a shift.

Policy Case B: the assessment tool

The policy was initiated in one of the five Danish military operational commands subordinate to the DCD (the specific command is not named for military security reasons). The policy aimed to enhance financial steering and secure planned effects. The initiative came at a time of severe and sustained criticism of the administration in the Danish Armed Forces from the National Audit Office and internal reporting, also pointing to a lack of adherence to regulations in general and in this command more specifically. The initiating commander framed the assessment tool as an iterative instrument to improve oversight through learning.

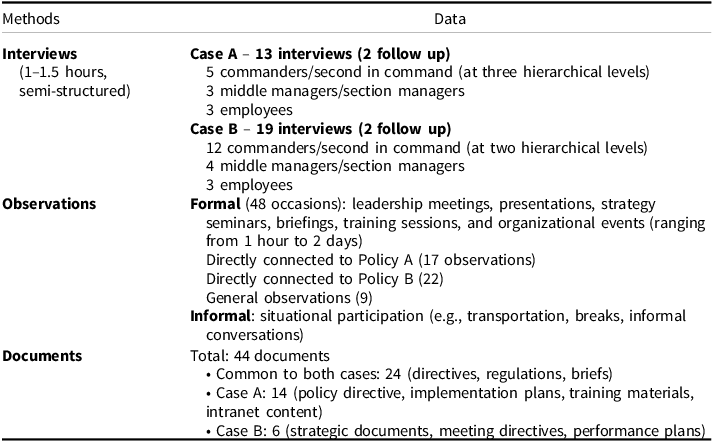

Data collection

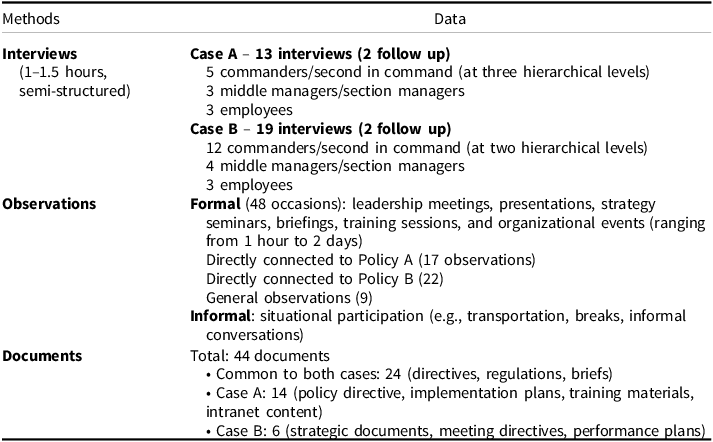

The study drew on interviews, observations, and case-relevant documents. The documents were analyzed to trace formal structures, policy content, and policy narratives. The interviews focused on the roles and experiences of the involved actors in the policy design processes to understand the interactions and participation. Formal approval to gain access to the field was negotiated with the Danish Defence and supported by prior research collaboration (the researcher’s embedded position and familiarity with the organization). This supported trust-building and allowed in-depth access to meetings, documents, and frontline perspectives. A total of 32 semi-structured interviews were conducted to elicit respondents’ experiences and interpretations of the policy design processes. Participants were encouraged to discuss enabling factors and challenges related to collaboration, learning, and inclusion. Interview themes included responsibilities, coordination practices, governance structures, and decision-making processes.

In both cases, meetings, seminars, and presentations related to policy and everyday business were observed throughout the design process to obtain a firsthand impression of what transpired. Interviews and observations took place from January 2022 to the end of 2023. See Table 2 below for an overview of the methods and data.

Table 2. Overview of methods and data employed in the study

Source: author’s own compilation.

Combining interviews, observations, and internal documents enabled a triangulated understanding of the formal and informal governance mechanisms shaping the two policy processes. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in NVivo alongside organizational documents. Coding was guided by the analytical dimensions of learning and inclusion, as well as governing mechanisms linked to institutional logics (Figure 1).

Empirical analysis

The following analysis traces how collaborative process demands, learning, and inclusion unfolded in each case across three design stages: problem formulation, solution development, and implementation planning. A structured within-case approach is applied, followed by a cross-case synthesis. The focus is on how institutional governance mechanisms shaped the presence or absence of collaborative practices throughout the design process.

Case A: the harassment policy

Case A – problem formulation

In Case A, the problem formulation phase lacked inclusion and mutual learning. Instead of engaging relevant experts or affected actors, the issue was quickly framed at the top level. The commander-in-chief diagnosed the problem and issued a solution, reinforcing a logic of urgency and decisiveness. At the executive level, harassment was primarily treated as an issue of individual non-compliance. Despite previous efforts failing to address the problem meaningfully, no organized attempt was made to investigate the underlying causes or consider alternative perspectives. One senior official described the approach as “narrowing-down challenges” through internal meetings, emphasizing a diagnostic mindset instead of open inquiry.

Formal mechanisms for involving multiple voices were absent. Internal documents focused on action and delivery, and suggestions to involve external perspectives were dismissed. Respondents described an intense pressure to deliver and “be responsive to orders,” replacing curiosity and reflection with symbolic activity.

A top-down, plug-and-play approach dominated the problem-solving, emphasizing simplicity and reinforcing existing assumptions. This univocal framing limited opportunities for critical reflection, inquiry, and the exploration of problems. While respondents recognized past policy failures and pointed out internal resistance, decision-makers interpreted these issues as a call for stricter enforcement, further constricting the policy space.

In sum, despite the complexity and persistence of the harassment issue, the problem framing in Case A was centralized, simplified, and lacked deliberation. The problem was unilaterally defined, bypassing collaborative exploration. Governance mechanisms such as urgency, role expectations, and compliance logics constrained inclusion and foreclosed alternative perspectives. The resulting process was shaped more by speed and control and less by learning or reflection.

Case A – development of solution

In this phase, the commander-in-chief tasked the Planning and Capability Division (PCD) with developing a training program for top management. The order, including a predefined solution and deadline, was sent directly from the commander’s office. Relevant and affected actors across levels and divisions were not involved. The process activated hierarchical role expectations, procedural routines, and narrow accountability logics that constrained cross-functional deliberation and learning.

Experts and affected end users were not included in the development of the solution. Even the unit responsible for the Armed Forces’ central learning platform was initially unaware of the initiative and had to invite themselves into the process. This exclusion led to inefficiencies, as the proposed solution did not align with the platform’s requirements, wasting scarce resources. Coordination was strictly top-down, reinforcing an operational logic prioritizing task control over reflection. A short meeting between the commander-in-chief, chief of staff, and the PCD team served primarily for top-level orientation and swift approval. As one PCD employee recalled: “They were very prepared, and then bum, bum, bum, you’re out again, and what happened? … The only thing was that [the commander-in-chief] wanted it to apply to the entire organization. And that’s where I run out of breath! 15,000 people!” (Employee, Level I). This sudden scaling of the solution without input or deliberation further highlighted how decisions were centralized and adjusted unilaterally.

As the project expanded, responsibility was handed over to the Organizational Education (EA) division. This transfer was not negotiated but decided at the top, reflecting hierarchical delegation rather than collaborative planning.

Employees described struggling to interpret very unclear expectations and shifting tasks. “We grope in the dark concerning what they want. We use our contacts, assistants, and adjutants to get information… And the short deadlines… you can’t waste time guessing!” They supplemented: “Tasks are expected to be sent down. Still, it’s impossible to send crucial information up. We find solutions, but how competent can it be if we can’t influence decisions?” (Employee, level I).

These accounts illustrate how centralized decisions, information asymmetries, and fear of overstepping roles hindered competent execution. Informal networks were used to compensate for the lack of formal dialogue. Reflection was local and limited to technical improvements. Broader discussions, especially across units or levels, were constrained to avoid interfering with others’ responsibilities. Feedback focused narrowly on reporting progress, not surfacing challenges or aligning strategic priorities.

Unrealistic deadlines, a high task volume, and limited space for reflection undermined effective coordination, mutual sense-making, and learning. Employees were often asked to revise or undo work that had already been completed due to sudden and unexpected decisions from above. These dynamics reflect embedded governance mechanisms, procedural rigidity, centralized control, and narrow accountability, which suppressed collaborative learning and constrained strategic planning.

Case A – implementation plan

The EA division developed the implementation plan based on the predefined policy solution and guided by strict deadlines, centralized procedural routines, and accountability logics. The plan included mandatory training that had to be conducted within fixed timelines, and centralized control mechanisms ensured compliance, being non-responsive to local conditions.

The implementation phase did not include real-world testing or iterative development of the policy model or planning. In sessions with affected actors, the PCD tested the content in a local seminar, verifying whether training cases were perceived as realistic and understandable. Even though this was testing, it differed from prototyping in revisiting core assumptions. Furthermore, the EA division received feedback through a hotline and train-the-trainer courses. Some responses, such as claims of “metal fatigue” or “this doesn’t concern us,” reflected resistance or disengagement, and concerns about increased sanctions also emerged. The feedback was incorporated into qualitative reports sent up the chain of command, with the expectation that further directives would follow if leadership deemed revisions necessary. While minor technical adjustments were made, core assumptions and instruments were not reconsidered.

In sum, collaborative process demands were weakly supported in the design phases. While some feedback loops were established, they did not challenge the underlying logic guiding the process. Iterations were reduced to content testing and technical fixes. No affected actors were involved in the design stages, and limited upward communication hindered mutual learning. Formal pressures to demonstrate responsiveness from public criticism and top-level leadership commitments in Case A did not translate into structural support for collaborative practices. While the case had prompted several prior attempts at resolution, none included a reconsideration of the problem definition or the assumptions guiding the approach. The dominant framing that located the issue in individuals’ failure to behave appropriately remained unchallenged. This closed the interpretive space and discouraged inquiry into potential systemic or organizational causes, limited reflection, and inclusion.

Case B: the assessment tool

Case B – policy formulation

In Case B, the commander simultaneously defined the challenge and determined a solution without engaging with affected actors, reflecting a top-down governance logic that centers on control and task compliance. The problem was framed as a need for greater alignment and control over sub-division resources, focusing on the sub-division’s lack of compliance. There was no institutionalized space for open inquiry or exploration of the problem during policy formulation, indicating the absence of governance routines that support deliberation and cross-level learning. Although Case B offered a more inclusive institutional setup than Case A, with regular meetings involving affected actors, these actors were not included in deliberations on how to interpret or frame the issue. The initial problem framing endured, placing lower-level agencies in defensive positions and dismissing their perspectives.

Observations from seminars, meetings, and interviews revealed a lack of mutual understanding, as subordinate commanders struggled to make sense of the tool because it did not reflect their way of understanding the problem, their specific conditions, and local demands. Top-level leaders emphasized execution and control, while sub-divisions pointed to misalignment between goals and resources, overregulation, and a lack of trust in professional judgment, revealing an institutional asymmetry in authority and voice shaped by firm role expectations and accountability structures. Rather than fostering an empathetic exploration of the problem, the issue was reduced to a binary “us/them” framing, illustrating how hierarchical norms and adversarial role assumptions can inhibit shared sensemaking. This approach simplified complex problems into opposites and led to the demotivation of lower-level managers.

Relatedly, there was little effort to promote mutual learning through collaboration during the initial phase. This chain-of-command initiation highlights the prevalence of top-down mechanisms that hindered iterative and constructive problem-framing and shared sense-making, which could challenge assumptions and truisms by building a collective understanding. The solution to the problem was first presented in a meeting between the commander and middle manager of the selected subsection, bypassing the management group. Although lower-level managers and employees appreciated the ability for swift and firm decision-making, the one-way approach, lacking consideration and opportunities for mutual learning, simultaneously demotivated subordinates and hindered nuanced understandings of problems. Moreover, bypassing the management group diminished the chances for engaging in a collaborative exploration of the problem and mutual reflection on the predefined solution by evaluating the ideas and proposals of a single individual.

Case B – development of solution

The detailed development of the solution was primarily coordinated through hierarchical command structures, leaving little space for engaging affected actors in mutual learning or deliberation. Communication remained largely instructional, shaped by governance routines prioritizing clarity and control over joint exploration. As one middle manager explained: “We often talk past each other, and we depend on the management teams to translate orders from the command level to the corps … Then we focus on breaking orders down for them [sub-divisions] so it’s as precise for them as possible” (Middle manager, Level II). This illustrates a problem-solving logic oriented toward task division rather than collective sensemaking or shared understanding. Rather than fostering dialogue across levels, top leaders emphasized the circulation of small items of information. As one lower-level leader explained, “The collaboration and coordination between the hierarchical agencies aren’t good. There isn’t enough information-sharing between the levels and very little knowledge of each other’s needs and conditions […] When they’ve said what they want, we have to do it. And we don’t know where to go to get it properly explained or framed” (Second in Command, Level III).

As revealed in the interviews across hierarchical and functional levels, the lack of deliberation hindered effective problem-solving. Rooted in centralized control, role expectations, and rigid coordination structures, these dynamics limited the integration of local knowledge and discouraged upward communication. Consequently, leadership remained insulated from insights that could challenge existing routines or improve implementation. These dynamics were reflected in how tasks were assigned without clarification or dialogue. As one employee recounted: “My boss just threw this job in my lap and said we have to come up with an estimate fast. I just said, ‘Yes sir!’ Even though we probably didn’t understand the content or the intent” (Employee, Level II). This way of working expressed urgency rather than collaboration. Deliberation about the problem, solution, or implementation methods was absent. A second-in-command explained:

“I try to define the task and then set a direction which I anticipate is important to the commander. Then I double-check the documents, so the commander doesn’t get annoyed” (Second in Command, Level II). This anticipatory behavior, shaped by implicit role expectations, undermined collective reflection and discouraged criticism and deliberation, even when actors held relevant insights.

The assessment tool was presented at a leadership seminar, where sub-divisions raised concerns about its data, purpose, and coherence with existing tools. However, the commander-in-chief dismissed these, reinforcing the perception that feedback was symbolic. Rather than deliberations, reflections, or shared sensemaking, the meeting produced a list of deadlines. The promised iteration lacked substance, and no mechanisms for feedback integration were specified. Although new insights emerged during development, they were sidelined. One employee noted: “I looked into what we already have and recognized we have everything! But we don’t use it the way it should be used! … I don’t think we use the forums we have accordingly” (Employee, Level II). A suggestion to integrate these insights into a more holistic steering model was rejected by a superior without explanation. Others similarly described how suggestions and criticism were dismissed without justification. Communication was reduced to information-sharing. Deliberation and reflections were often dismissed as “chit-chat” or “unnecessary details,” reinforcing a logic where criticism was seen as unproductive or inappropriate.

In summary, mutual learning and critical reflection were largely absent and unsupported in the development phase. Inclusion was not considered a relevant concern nor was it structurally enabled. These constraints were not merely the result of isolated leadership decisions but reflected institutionalized governance patterns prioritizing formal compliance and task execution over adaptive sensemaking.

Case B – the implementation plan

The commander ordered that the implementation of the assessment tool should align with the existing annual planning and reporting processes. Lower-level commanders and management teams were tasked with delivering performance assessments and data by specified deadlines. The implementation was intended to adhere strictly to procedural routines emphasizing formal compliance, allowing no room for deliberation, process transparency, ongoing evaluation, or contextual adaptation – despite the commander’s stated commitment to iterations.

Some testing of the tool was included, concentrating on whether the information provided by subcommands met the commander’s expectations for control, reinforcing single-loop learning focused on technical optimization. Broader aims were not pursued, such as clarifying the underlying problem, refining the solution logic, or integrating the tool with existing systems. Although the assessment tool aimed to simplify sub-command tasks, those affected were not involved in defining the problem or exploring alternatives. Mutual learning and vertical dialogue were absent, preventing new insights from reaching the decision-making level. Critical reflection was also limited, as implementation decisions were neither justified nor debated. Testing efforts focused solely on superficial content adjustments instead of fostering deeper organizational learning.

Despite differences in organizational context, similar structural governance mechanisms constrained learning and inclusion in both policy cases, indicating a deeper layer of institutional embeddedness. These findings illustrate how hierarchical logics and procedural routines shape the unfolding of collaborative process demands, providing the basis for the discussion of empirically embedded governance dynamics in the next section.

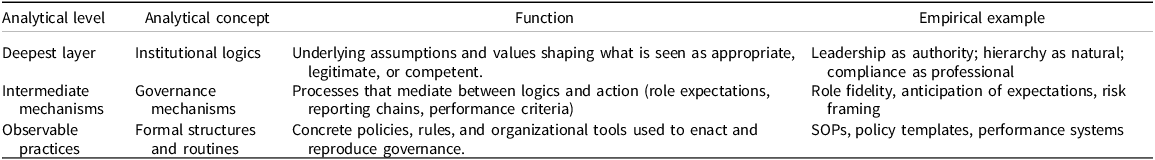

Military institutional dynamics influencing policy design processes

The cross-case analysis revealed recurring governance dynamics that constrained learning and inclusion during policy design. These operated both at the surface level of organizational routines and the deeper institutional level of embedded logics. Three interrelated dynamics were especially significant: leader-centric practices, role adherence, and compliance-driven control.

Leader-centric practices

Across both cases, leadership was highly centralized. Commanders defined both problems and solutions early, and these framings dominated subsequent action, limiting space for alternative interpretations or iterative exploration. Decisions were rarely questioned, and even when implementation challenges arose, they were not fed back upward. Communication primarily flowed top-down, leaving lower levels with little insight into the strategic intentions and cause-and-effect rationales underpinning them. Feedback was reduced to routine reporting, with limited potential to reshape decisions.

This leader-centric orientation reflected a governance logic rooted in deference to rank, where the expectation that leaders should justify or contextualize decisions was structurally absent. Leadership functioned as a performative mechanism for enacting control rather than an enabling force for deliberation and joint sensemaking. Without elaborated rationales or feedback channels, actors relied on informal cues and guesswork. The effect was fragmented design processes in which task alignment substituted for collective reflection and sensemaking.

Strong role adherence

Rigid role segmentation further constrained collaboration. Responsibilities were narrowly defined, and deviating from formal authority lines was seen as inappropriate or even disloyal. Dialogue across functions or levels was limited, as professional identity was tied to role fidelity rather than to cross-boundary problem-solving. Actors who attempted to broaden discussions risked being perceived as overstepping.

This structural segmentation discouraged the integration of knowledge beyond assigned scopes. Relevance was judged by formal position, which meant valuable insights from lower levels or other functions were often dismissed. Even when routines were ineffective, actors defaulted to staying within their role boundaries. The result was a governance logic where competence equaled role adherence, constraining adaptation by rendering collective exploration illegitimate.

Compliance-driven control

Governance mechanisms prioritized control, procedural clarity, and output delivery. Despite stated ambitions to promote adaptability, the dominant logic followed a linear, task-oriented model that treated problems as static and solvable through predefined steps. Collective problem-solving was reduced to planning: assembling modular pieces into fixed solutions. Feedback systems primarily existed to verify compliance rather than to support reflection or course correction.

Lower-level insights were often filtered out or dismissed as noise, complaints, or role-overstepping, with no institutional structures in place to legitimize upward influence or collective reframing. When reflection occurred, it mainly remained technical and surface-oriented, focused on technical improvements rather than questioning assumptions or goals, amounting to single-loop learning at best.

These patterns reflected an institutional condition that rewarded predictability and task completion over interpretive flexibility or open-ended learning. Actors met expectations but remained locked in practices misaligned with the complexity of their challenges. The organization functioned like a layered system of control, where role expectations discouraged questioning, communication routines suppressed dialogue, and performance systems prioritized measurable outputs over collective insight. Together, these mechanisms formed a self-reinforcing web that stabilized compliance and discouraged adaptive practices—even when their necessity was widely acknowledged.

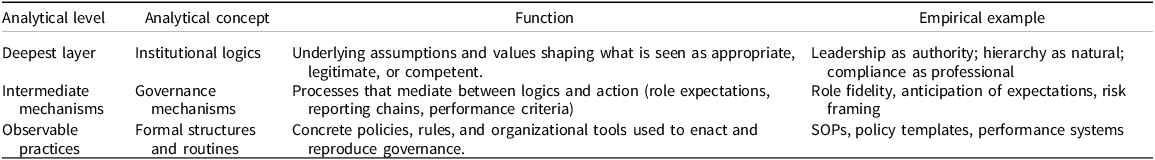

Table 3 synthesizes the core institutional patterns identified across the two cases, illustrating how leadership logics, role expectations, and control routines interact as layered governance mechanisms that stabilize and reinforce compliance, constrain learning, and limit adaptive capacity.

Table 3. Governance layers and mechanisms identified in two policy design cases

Source: author’s own analysis and synthesis.

Discussion

Building on this synthesis, the discussion explores how these governance mechanisms and institutional logics operate as deeper organizational structuring forces. Despite formal ambitions for adaptability, the analysis revealed consistent constraints on collaborative process demands across differing conditions. These constraints reflect not isolated practices but rather resilient institutional patterns that may shape adaptive policy design in other hierarchical public organizations.

The discussion is organized around three governance dynamics derived from the empirical findings: (1) leader-centric governance, (2) bureaucratic role adherence, and (3) compliance-driven governance. Together, these themes illustrate how risk-management organizations struggle to support interpretive flexibility and cross-level engagement despite being optimized for clarity, speed, and control – a dynamic with implications for adaptive policy design in hierarchical public organizations. The discussion situates these insights within broader debates on governance, institutional logics, and the challenges of designing administrative policies in risk-oriented bureaucracies.

Leader-centric governance

The analysis revealed a governance pattern where leadership was enacted and anticipated – subordinates aligned with presumed expectations, often without explicit direction or profound understanding. This structure reinforced vertical coherence and constrained space for reframing problems rather than including various knowledge bases. As synthesized interpretive authority remained concentrated at the top, functioning as both the source of direction and the filter of meaning, with no formal structures to explore alternative problem framings or solutions. In effect, this governance mode concentrated the generative and trajectory-setting power of policy design in the hands of a few, leaving little room for plural perspectives or reflective deliberation (Schön Reference Schön and Ortony1993). How problems are framed at the outset shapes which solutions are seen as viable and position actors as competent or deviant. It also determines whose voices are legitimized during implementation (Hoppe Reference Hoppe2010). By excluding other actors and knowledge bases, this mode of governance reinforced ingrained assumptions and positioned leaders as the sole interpreters of problems and solutions (Fischer Reference Fischer2003; Hoppe Reference Hoppe2010). As Hutchison (Reference Hutchison2013) notes, military leaders often construct issues as stemming from subordinate incompetence – a framing that amplifies their status while narrowing the space for criticism. This suppression of early-stage critical engagement foreclosed collective sensemaking and increased the risk of one-dimensional, biased outcomes (Fischer Reference Fischer2003; Rein and Schön Reference Rein and Schön2020).

Despite their importance for qualifying decisions, no mechanisms existed to involve affected actors or implementation-level perspectives early in the design process (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell, Sørensen and Torfing2017). Adaptive design requires an empathic approach that supports early engagement with the lived environments, perspectives, and resource constraints of those implementing policy and affected by solutions (Bason Reference Bason2014; Bentzen Reference Bentzen2022; Junginger Reference Junginger and Bason2014). Without such mechanisms, design risks detaching from the conditions under which it must function. While some leaders acknowledged implementation challenges, their reflections remained more personal than institutional, illustrating how concentrated authority can limit collective sensemaking and adaptive learning in hierarchical organizations. Challenges were often reduced to blaming organizational reluctance or subordinate incompetence, a pattern seen in other military studies (Friesl et al. Reference Friesl, Sackmann and Kremser2011; Gushpantz Reference Gushpantz2017; Holth and Boe Reference Holth and Boe2019; Hutchison Reference Hutchison2013). Without mechanisms to redistribute interpretive authority, deliberation was confined, learning constrained, and the organization was left with surface-level coherence but limited capacity for adaptive or reflexive policy practice (Fischer Reference Fischer2003; Yanow Reference Yanow2000). While intensified in military settings, these dynamics highlight boundary conditions for adaptive policy design in hierarchical public organizations more generally.

Bureaucratic role adherence

The findings demonstrate how strict role segmentation and formal authority structures fragmented the design process, limiting systemic understanding. Rather than adapting to task complexity or engaging in learning, actors coordinated through routine procedures and standardized professional expectations. Responsibilities were rigidly divided, and adherence to assigned roles was central to professional identity. These roles were reinforced not only by the formal hierarchy but also by active role-policing at all levels: subordinates corrected both peers and leaders, while leaders enforced boundaries downward. This upheld vertical coherence but limited flexibility and innovation.

Segmentation appeared self-evident, reflecting deeply internalized assumptions about proper conduct reinforced through military socialization (Hutchison Reference Hutchison2013). As studies on military reform show, new modes of working calling for flexible or cross-functional engagement often trigger identity conflicts, underscoring the embeddedness of fixed roles in military organizations (Holmberg and Alvinius Reference Holmberg and Alvinius2019; Thorbjørnsen Reference Thorbjørnsen2007; Tillberg Reference Tillberg, Obling and Tillberg2021). In this context, stepping outside one’s assigned scope was not simply discouraged – it was perceived as inappropriate, even deviant. The result was a design process driven by execution within narrow scopes; lower-level insights rarely traveled upward, and role expansion had no institutional support (Hoppe Reference Hoppe2010).

This rigidity carried costs: when implementation failed or unintended consequences emerged, responsibility could be traced to individual roles, discouraging actors from raising concerns or revisiting assumptions and limiting opportunities for shared sensemaking.

These findings illustrate that, in practice, organizational role adherence and hierarchical enforcement can limit the use of mechanisms such as role flexibility, integrative knowledge practices, and horizontal coordination, which the literature identifies as supporting complex problem-solving (Ansell and Gash Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Bason Reference Bason2014). In the cases studied, alternative voices and knowledge were structurally marginalized, and contributions outside prescribed roles were rarely recognized as legitimate; inclusion and learning were thus foreclosed by the system rather than actively resisted by actors, illustrating how these governance mechanisms can constrain adaptive policy design in hierarchical public organizations.

Compliance-driven governance

The findings reveal that policy design was structured around governance mechanisms emphasizing compliance and control rather than inclusion or learning. Despite formal ambitions for change, problem-solving remained linear and task-oriented. Standardized routines framed problems as already solved and implementation as planning and execution, while feedback from subordinates was often filtered out or ignored, structurally limiting cross-level exploration. This illustrates differences between governance optimized for operational clarity and speed versus collaborative policymaking logics, which emphasize reflexivity, iteration, and responsiveness to complexity and uncertainty.

The reflection focused on technical adjustments rather than reconsideration of goals or assumptions, exemplifying single-loop learning and the limited structural capacity for adaptive, double-loop governance (Argyris and Schön Reference Argyris and Schön1997). A narrow understanding of problem types, available tools, and governance alternatives reinforced what Argyris and Schön (Reference Argyris and Schön1997) referred to as skilled incompetence: the ability to meet formal expectations while remaining blind to their limitations. Structural constraints on adaptive learning were further amplified by organizational and governance conditions identified in other contexts (Boin and van Eeten Reference Boin and van Eeten2013; Freeman and Calton Reference Freeman and Calton2021). While intensified in military contexts, these dynamics illustrate structural limitations that can impede adaptive policy design in hierarchical public organizations more broadly.

Collaborative design, characterized by iteration, shared interpretation, and responsiveness to complexity (Ansell and Gash Reference Ansell and Gash2008; Bason Reference Bason2014), was largely absent and remained unsupported by existing governance structures. Learning remained fragmented and reactive, and modest attempts to reframe processes were marginalized due to structural and procedural constraints.

These findings underscore the importance of studying policymaking in context: governance mechanisms operate as an interrelated web that shapes how problems are framed, how solutions are developed, and the institutional conditions that enable agency, learning, and adaptation (Hoppe Reference Hoppe2010; Howlett Reference Howlett2014).

Conclusion

This study contributes to the governance and policy design literature by showing how institutional features of military organizations shape the conditions under which collaborative process demands (e.g., learning, inclusion) emerge in administrative policy design. While focused on the military, these patterns illustrate broader governance dynamics relevant to hierarchical and risk-oriented public organizations. By analyzing policy design processes in their organizational context, the study demonstrates how governance logics and institutionalized expectations structure opportunities for inclusion, learning, and adaptation.

Drawing on administrative policy cases from the Danish Armed Forces, the analysis demonstrates how centralized decision-making, role adherence, and compliance-oriented governance logics constrain exploratory sensemaking and adaptive capacity in administrative policy processes – a pattern likely relevant to other hierarchical public organizations. Problem framing was primarily delegated to individual leaders, mutual learning was limited, and policy solutions tended to mirror previous practices, reflecting strong adherence to established routines and compliance norms that prioritized conformity over reflexive learning. The processes lacked structural support for reflection, inclusion, and cross-level dialogue. Operational procedures and methods were often transposed onto administrative policymaking, despite the latter involving persistent and complex challenges that require learning and capability building. These patterns emerged from the interplay of governance mechanisms, role structures, and accountability systems.

While the study did not set out to assess the organization’s openness to change, the findings reveal how governance mechanisms form a tightly woven “web,” aligning leadership expectations, accountability structures, and action-oriented routines. This web channels activity along predefined routines, shaping decision-making and limiting the scope for addressing ambiguous or persistent problems – a pattern that may constrain adaptive policy design in other hierarchical organizations.

Future research could investigate how adjustments to leadership authority, role segmentation, and compliance mechanisms create conditions for more reflexive and inclusive policy design. Exploring the use of collaborative tools across different phases of the policy process, particularly in risk-oriented or hierarchical organizations, may further illuminate the institutional conditions under which learning and adaptation can occur. Leadership studies could clarify how reform-minded actors navigate structural constraints when tackling complex policy challenges.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods, and no replication materials are available.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jacob Torfing and Anne Roelsgaard Obling for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this article. The author also sincerely thanks all members of the Danish Armed Forces who participated in the study for their time and contributions, which made this research possible.

Funding statement

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

The author declares none.