The so-called investiture painting from the palace at Mari (Figs. 2 and 5), a site on the Euphrates in what is today Syria (Fig. 6), dates from the eighteenth century bce, the Old Babylonian period of ancient Mesopotamian culture. Today in the Louvre, it is unique in its state of preservation and richness of imagery within the corpus of extant ancient Mesopotamian works of art in the medium of wall painting. Perhaps no other single work of art surviving from the ancient Near East is broader in visual vocabulary. The painting is further unique in its posing a difficult iconographic problem. There are a significant number of visual elements in the composition familiar from their widespread occurrence in ancient Mesopotamian art. These include the flowing vase, the ring and rod, mythical quadrupeds, the mound rendered with the “mountain scale” pattern, the protective Lama goddess with raised hands, and the goddess Ishtar with her attributes, the lion, the scimitar, and the maces emanating from her shoulders.1 The unique way in which these figures are brought together and set in relationship with elaborate elements of frame, landscape, and ornament, however, makes the iconography of the painting challenging.2 Even though the composition stands alone within its chronological and spatial framework, its imagery resonates with the fundamental figural aspects of many other ancient Mesopotamian monuments. Its almost encyclopedic visual repertoire warrants an interpretive endeavor within the larger framework of the art of the ancient Near East.

6. Map of ancient Mesopotamia.

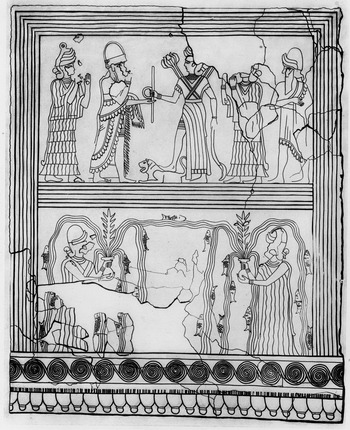

The painting is a symmetrical composition delineated by an interior frieze of running spirals, finished above and below by bands of what seem to be tassels (Figs. 2 and 5).3 The imagery of the scene, particularly its central panel showing the king and the goddess Ishtar (Fig. 7), is primarily embedded in the visual language of Babylonia, to which Mari was closely bound culturally and politically in the early second millennium bce. Aspects of the larger composition (Figs. 2 and 5), such as the interest in landscape and the natural world, as well as the fondness for abstract patterns in the form of bands and running spirals, evoke the contemporary artistic traditions of Syria, Egypt, and the Aegean.4 With the large representations of the protective Lama goddess, a Babylonian figural type going back to the Neo-Sumerian period, that flank the landscape, the composition resumes its hieratic character outside the central panel as well.5

7. Drawing of the central panel of the “investiture” painting from the palace at Mari. From Parrot, Peintures murales, pl. XI.

The line drawings in Figures 5 and 7 show in clear and neutral fashion what is preserved of the composition. The photograph of the remains of the painting in Figure 2, which is the standard in current academic publications on the art and archaeology of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, features some restorations only where they are certain or highly likely. In tandem with the line drawings, it is possible to note the restored segments of the painting in the photograph, distinguished also by difference in color and lines of fracture. The two major gaps in the composition are the upper part of the lateral panel on the left hand side and a portion of the zone above the central panel. Also missing are the heads of both of the lowermost bovines flanking the centerpiece. In light of the symmetrical configuration dominating the composition, one may make the assumption that the left hand side mirrored the right hand side, perhaps with the exception of the large blue bird, as proposed in the next chapter. It seems unlikely that the missing part of the zone above the central panel featured any figural or other imagery that would have been meaningful within the overall composition of the painting. From the remains of the painting, it is also clear that the outer frame extended horizontally toward the right hand side, suggesting that the composition had imagery adjacent to it, perhaps within a programmatic whole (Fig. 2). Today, in studying the painting, we certainly are at a distadvantage by not knowing what was around it and what the contemporary decorative program of its findspot was like. However, the image is also well rounded enough within its own parameters to justify an iconographic analysis and further contextualization within the artistic traditions of ancient Mesopotamia and adjacent areas.

Archaeological Discovery and Architectural Setting

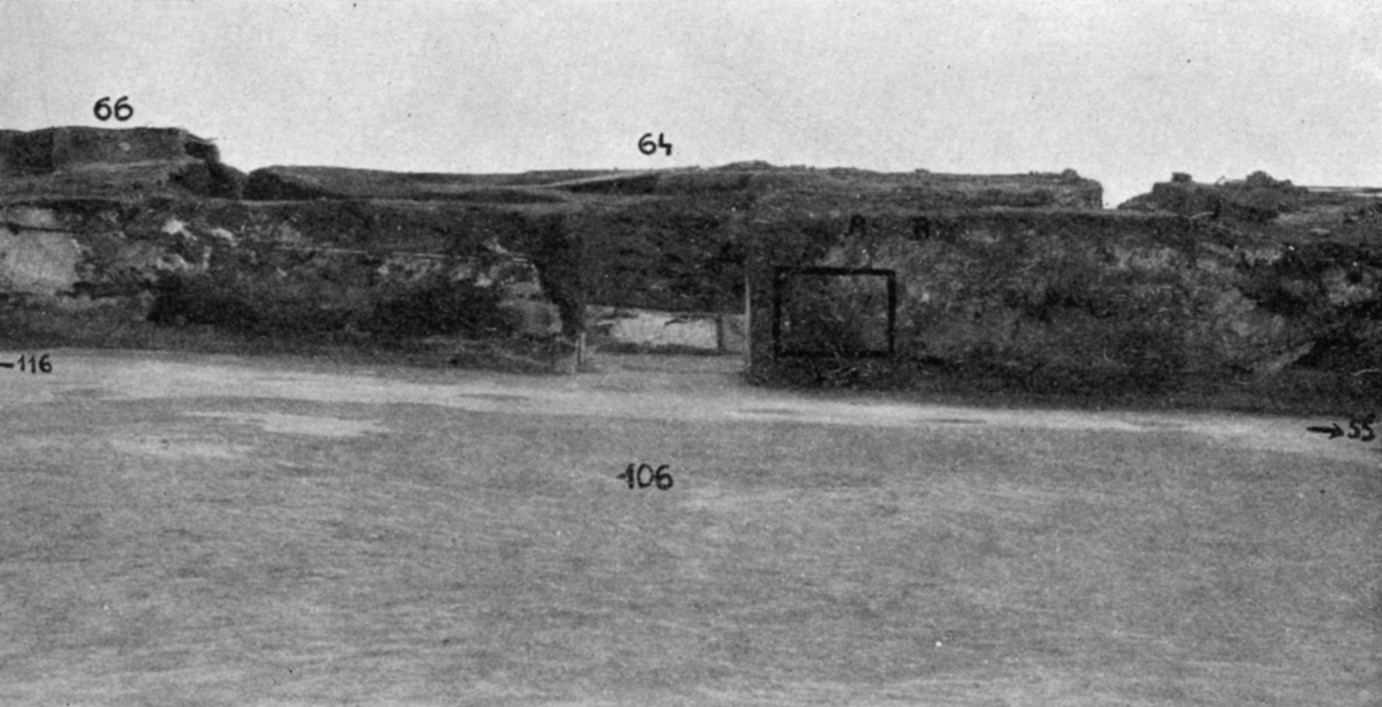

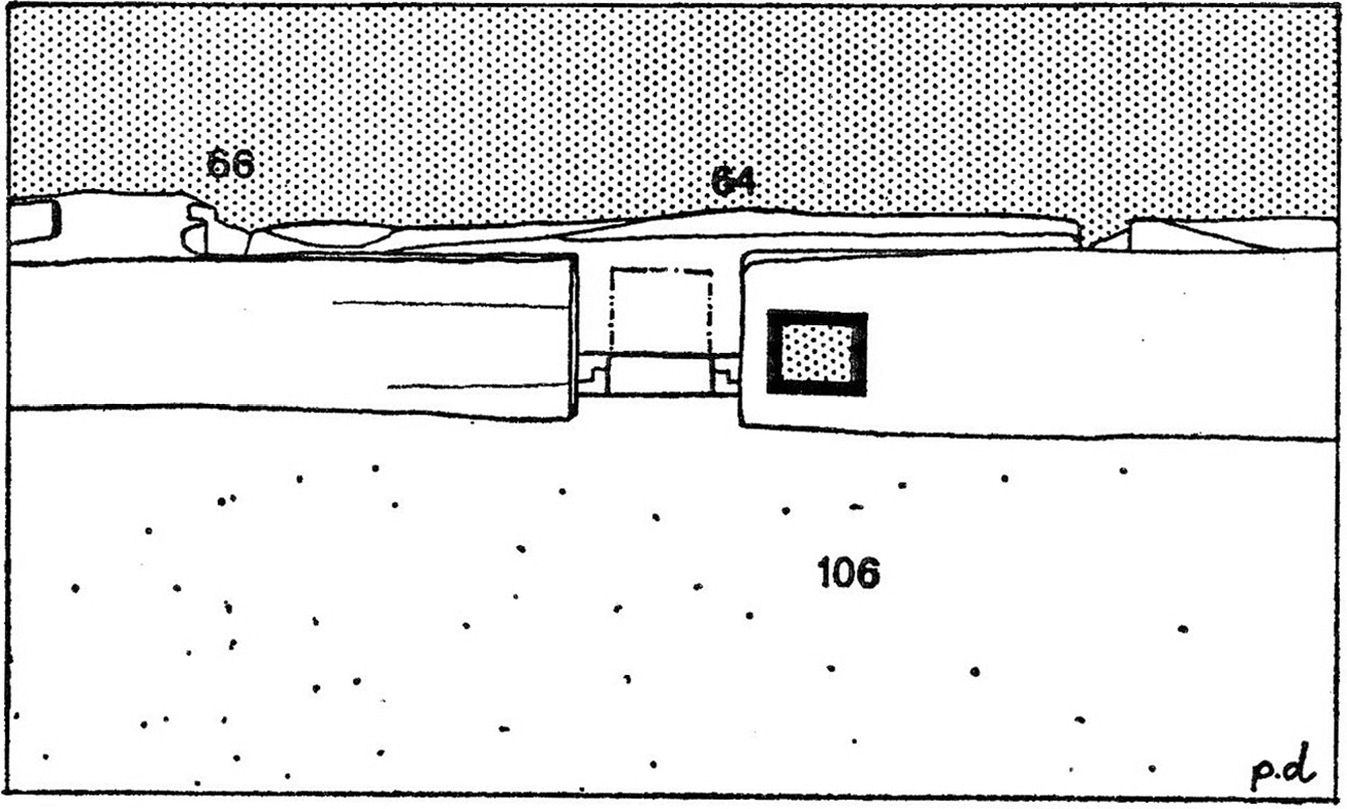

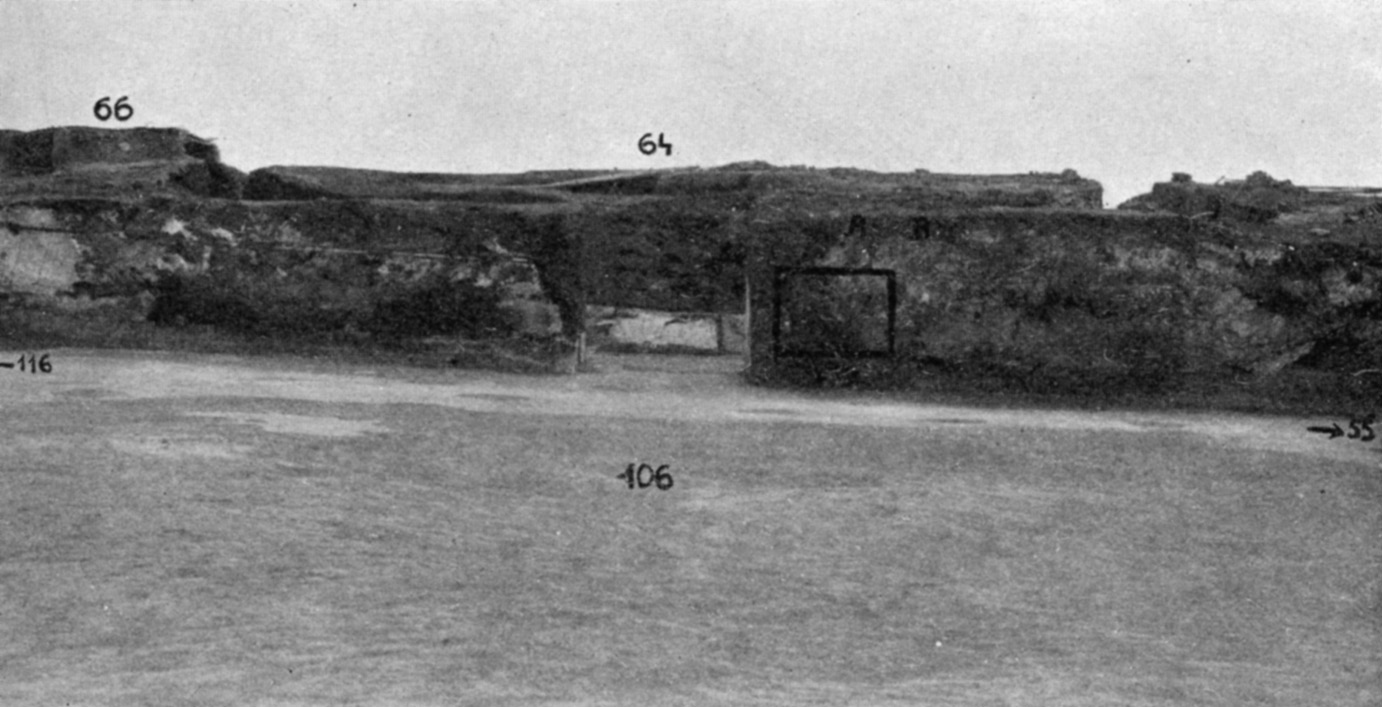

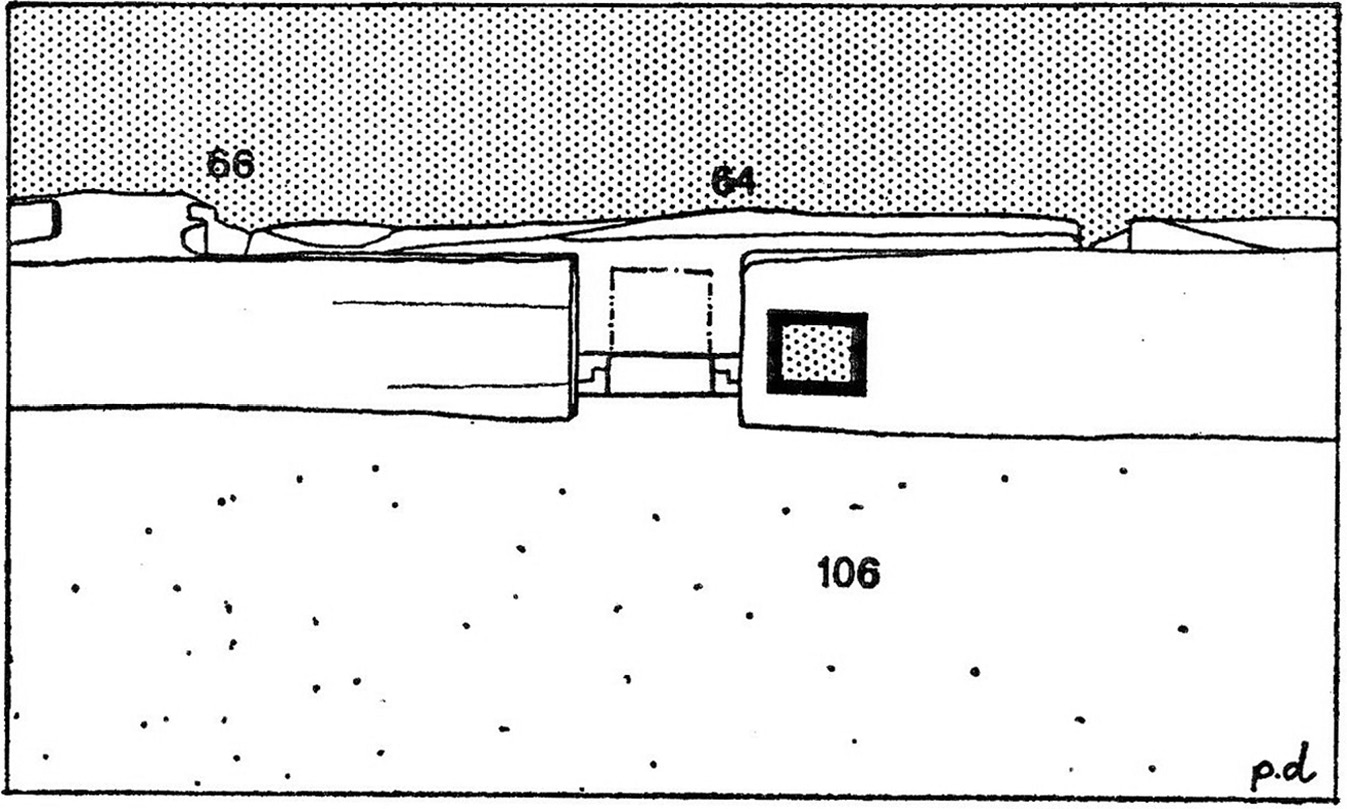

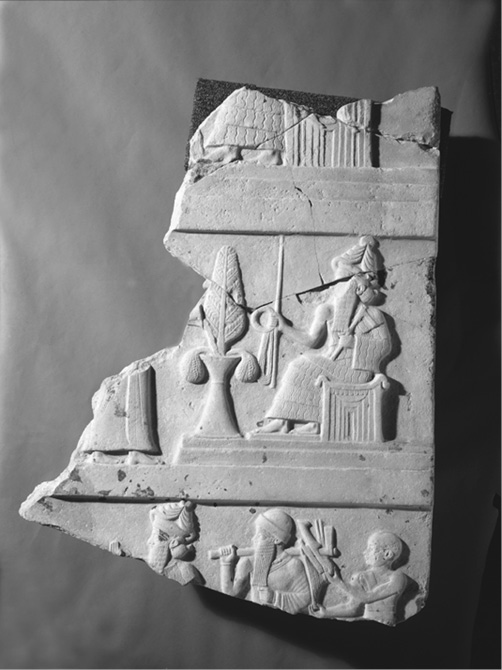

The “investiture” painting from Mari was discovered in situ by André Parrot during the 1935–36 excavation season on the south wall of Court 106 of the Old Babylonian palace, to the right of the doorway leading into Room 64, the throne room suite (Figs. 8–9). The bottom of the painting was about 35 cm above the ground line. With a width of 2.5 m, and a height of 1.75 m, the composition was at eye level (Figs. 8 and 9).6 It was painted above an ornamental plinth directly on a mud plaster coating.7 Moortgat dated the painting to the time of Zimri-Lim (1775–1762 bce), a contemporary of Hammurapi (1792–1750 bce), and the last resident of the palace before its destruction by the Babylonian king around 1762 bce.8 Moortgat’s principal basis on which to propose this date was stylistic. He drew attention to the Mari painting’s depiction of the horned crown of divinity in profile (Fig. 7), which he considered to have been modeled after the Stela of Hammurapi (Fig. 10), the first extant occurrence of this rendition in the art of Babylonia. In fact, Moortgat connected the “investiture” painting specifically with this stela, a monument originating in the later years of Hammurapi’s reign.9 The standard manner of showing the horned crown in ancient Mesopotamian art was a frontal depiction throughout the third millennium bce, as seen in the commemorative relief sculpture of the Ur III period (Fig. 11).

10. The relief carving on the Stela of Hammurapi, Old Babylonian period.

Jean-Claude Margueron, the previous excavator of Mari, however, criticized Moortgat’s giving precedence to the art of Babylonia in the development of anything original in the visual arts.10 He posed the question what if it was in Mari that the depiction of the horned crown in profile was first developed and it was Babylonia that borrowed it from its northern cousin? Thus, he proposed to move the date of the “investiture” painting about 40 years earlier, from the destruction of the palace by Hammurapi, to the time of Yahdun-Lim, father of Zimri-Lim, and “the first true ruler of Mari in the Old Babylonian period.”11 In this study, I concentrate on the meaning behind the imagery of the “investiture” painting rather than the complex and long-standing debate on the dating of the Mari paintings and its implications for the chronology of the palace. Here, the discussion of the chronology is important inasmuch as there is no disputing the wider frame for dating the painting sometime in the first several decades of the eighteenth century bce, the height of the Old Babylonian period.12

The Mari Painting in the Context of the Art of the Ancient Near East

The painting is the first extant image in ancient Mesopotamian history that offers a clear visual expression of the division and connection between a sacral terrestrial domain and its celestial counterpart. The terrestrial in the Mari painting is the lower register of the central panel featuring the flowing vase, and the celestial is the upper register featuring Ishtar, the ancient Mesopotamian lady of heaven and a goddess co-extensive with the star Venus (Fig. 7). These two domains are aligned vertically within a framed unit, communicating the potential of movement or transition between them. The painting presents the earliest attested paradigm in the art of ancient Mesopotamia for formulaic bi-partite images that feature a terrestrial visual element, such as a stylized plant, the flowing vase, or a combination of both, with a celestial signifier placed above it, such as the winged disk of the later periods. In this regard, it deserves detailed scrutiny from a cosmological perspective.

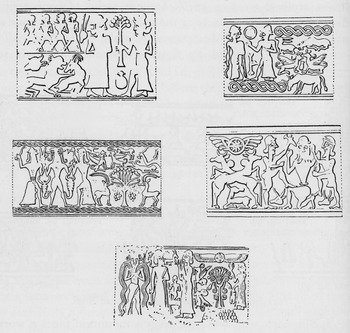

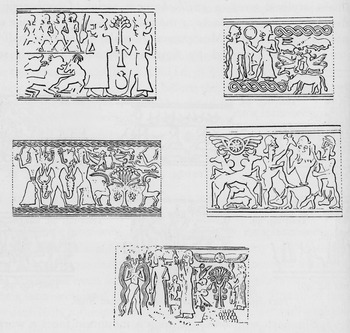

Representations of stylized plants or trees flanked by animals or mythological creatures abound in the art of ancient Mesopotamia prior to the “investiture” painting, as seen in the art of Uruk, Jemdet-Nasr, and Early Dynastic periods of the fourth and third millennia bce. But none of these images features as clearly delineated a celestial layer or symbol in association with them in a well-rounded format as the central panel of the Mari composition.13 Numerous examples of multi-level images come especially from the western Asian artistic traditions of the Late Bronze and Iron Age. They belong to a number of states in northern Mesopotamia, Syria, and Anatolia, such as the Mittanian (ca. 1500–1350 bce), Hittite (ca. 1400–1200 bce), and Middle (ca. 1350–1000 bce) and Neo-Assyrian empires (883–612 bce). According to Moortgat, key in the formulation of these visual statements is Kerkuk glyptic, the cylinder seals of the Kingdom of the Mittani (Fig. 12).14 Examples that integrate the flowing vase or water with the terrestrial levels of such stratified compositions are observed particularly in the glyptic art of the Kassite (ca. 1595–1157 bce) and Assyrian cultures; they incorporate the vase into representations of stylized plants.15

The intercultural era characterized by the Near Eastern empires of the Late Bronze Age had its foundation in the interculturalism of the Middle Bronze Age, in which the kingdom of Mari was an important player. With its location on the Middle Euphrates, the art of Old Babylonian Mari partakes both of Babylonian and Syro-Mesopotamian artistic idioms, not to mention its openness to influences from Egypt and the Aegean.16 As a state in Syria, the kingdom of Mari lies closer than does Babylonia spatially and conceptually to the artistic ideas that developed in northern Mesopotamia and Anatolia in the Late Bronze and Iron Age. Although not an empire, as a kingdom with a significant sphere of regional territorial control, Mari belonged to the same political milieu as the kingdoms of Shamshi-Adad (ca. 1808–1776 bce) of Assyria and Hammurapi (1792–1750 bce) of Babylon. It was engulfed by both in the eighteenth century bce.17 These two territorial states laid the political groundwork for the great empires of the Late Bronze and Iron Age in Western Asia.

There is an uninterrupted chain of artistic production in the medium of wall painting in Syria and Mesopotamia from the Middle Bronze through the Iron Age, as attested in the archaeological record, albeit in highly fragmentary condition, constituted by finds from Alalah, Qatna, Nuzi, Dur Kurigalzu, and Kar Tukulti-Ninurta from the Late Bronze Age; and those from Til Barsib and the Neo-Assyrian royal palaces from the Iron Age. By virtue of its hieratic figural repertoire of Babylonian descent, the Mari painting has more in common with ancient Mesopotamian examples of wall painting and works of art in other artistic media, such as cylinder seals, sculpture, and glazed brick panels, than with extant examples of wall painting from Syria.18 Fragments of painting from Syrian sites of the Late Bronze Age, such as Alalah and Qatna, show an approach to painting thematically and stylistically quite different from the “investiture” painting. They are much more closely aligned with Aegean traits than is painting in Mari, despite the latter’s incorporating running spirals and a degree of naturalism, as discussed further in Chapters 2 and 4.19

The principal components of the Mari painting that connect it with remains of wall painting surviving from Mesopotamia in the second and first millennia bce are elements of frame, ornament, a compartmentalized approach to compositions of scenes, and, to a certain extent, figural imagery.20 A degree of resemblance in imagery is seen particularly in the decoration of the palace of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 bce) at Kar Tukulti-Ninurta, which features stylized trees flanked by winged bird-headed figures, and the wall painting from Residence K of Sargon II’s citadel at Khorsabad depicting the conferral of the ring and rod on the king by the god Ashur.21 Also related in figure and composition is another Neo-Assyrian work in a medium close to painting, the glazed brick panel of Shalmaneser III (858–824 bce) from the throne room suite of Fort Shalmaneser at Nimrud.22 All these works of art make use of frames, compartmentalization, and ornamental bands, which are concentric in the case of the Khorsabad painting and Fort Shalmaneser glazed brick panel.

The Kar Tukulti-Ninurta and Khorsabad paintings, however, do not juxtapose two different principal layers of figural representation within a meaningful whole. As for the Fort Shalmaneser glazed brick panel, as a descendant of the so-called “sacred tree” relief of the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II (Fig. 3), it does feature two primary layers in its central field. Nevertheless, it extracts the terrestrial tree from its usual location and places it above the winged disk. In spite of the overlaps in technique, ornament, and imagery between the Mari painting and wall painting and glazed brick panels in ancient Mesopotamia at large, the study of the “investiture” painting need not be confined to a framework determined by artistic medium alone. Its composition and imagery are in conversation with many works of art from different traditions in the ancient Near East in a variety of media.

Surely, the best crystallization in the art of ancient Mesopotamia of the binary compositional principle of the terrestrial and celestial can be found in the “sacred tree” relief from the throne room of the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (Fig. 3), the first capital city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire upon the shift away from Assur.23 The panel, along with its damaged counterpart from the same space, is the only composition in relief sculpture from the art of the Neo-Assyrian Empire that shows the tree surmounted by the winged disk and flanked by two representations of the royal figure. By contrast, early Neo-Assyrian palaces abound in relief images of the “sacred tree” depicted alone and those that show it flanked only by winged mythological figures without the king and the winged disk. As such, the throne room “sacred tree” panel of Ashurnasirpal II is a truly unique work of art that warrants that special emphasis be placed on it in the scholarship on the art of ancient Mesopotamia. This panel constitutes a summation and culmination in the Iron Age of a long-standing Late Bronze Age artistic tradition featuring emblematic designs of stylized trees, winged mythical figures, and winged disks, here combined with the royal figure. In its uniqueness, semantic denseness, and figural and compositional repertoire, it is a direct counterpart to the Mari painting, found also in the context of a throne room suite, across the one-thousand year period of time that separates, or connects, them.

A hallmark of the northern Mesopotamian and Anatolian visual imagery of the Late Bronze Age, the winged disk is absent from the Mari painting. However, with its placing the domain of the celestial goddess Ishtar above an aquatic terrestrial realm, characterized also by stylized plants growing out of the flowing vases, the Mari painting is aligned structurally with these later compositions. Among the other characteristics of the painting that speak to this affinity are the “sacred” trees and winged mythical beings depicted prominently in its outer field and the overall symmetrical design of its composition. Last but not least, Ishtar’s holding the ring and rod in the upper field of the Mari central panel is a direct antecedent of the inclusion of the ring, although without the rod, in the depiction of the god inside the winged disk in the throne room “sacred tree” relief of Ashurnasirpal II (Figs. 3 and 13). In other examples of the Assyrian winged disk, the god within also holds weapons (Fig. 14), paralleling the warlike attributes of Ishtar shown in the Mari painting (Fig. 7).

In certain ways, the “investiture” painting is still within the artistic idiom of what Moortgat had characterized as Sumero-Akkadian art, the imagery of, say, the art of Sargon of Agade (ca. 2334–2279 bce), Gudea (ca. 2100 bce), and Ur-Namma (ca. 2112–2095 bce).24 But it is also novel in its conversation and concordance with the iconographic paradigms of the Syro-Mesopotamian and Anatolian cultures of the several centuries that follow the Old Babylonian period. Much more than other extant works of art from the Old Babylonian period, such as the Stela of Hammurapi, it is the lynchpin between the “classical” art of Babylonia and the eclectic trends that characterize the art of the great empires of the Late Bronze and Iron Age based in northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Egypt.

The Affinity between Mari and Assyria

The Old Babylonian period culture of Mari and the Neo-Assyrian Empire share, more than any other states in ancient Mesopotamian history, a well-documented presence of scholars and specialists associated with the royal palace, especially experts on prophecy and divination.25 Even though the written attestation for Neo-Assyrian prophecy comes exclusively from the Nineveh archives of tablets dating to the reigns of Esarhaddon (680–669 bce) and Ashurbanipal, there is reason to assume that the practice had an earlier history in Assyria.26 As intellectuals in their own right, the master iconographers responsible for the design and execution of the regal works of art belonging to these two courts were likely closely familiar with these scholarly milieus. As such, a comparative treatment of the Mari painting and the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel from Nimrud as bearers of special knowledge is essential.

Among the primary activities of the specialists at Old Babylonian Mari, prophecy and divination had the most important place. Both activities were concerned with validating actions taken in the present and their consequences for the immediate future in the political and military affairs of the state.27 Such an emphasis in governmental matters on prophecy and its confirmation through divination may point to the presence of a theoretical or speculative background to these practices as well. Divination had close links with conceptions both of history and temporality, particularly in its capacity to make the future an object of scrutiny, relating an empirical perspective focused on individual phenomena to larger patterns or structures within the cosmic order. The intellectual background both of prophecy and divination may also have been connected more fundamentally with conceptions of the past, present, and future; or those of sacral time and history on a philosophical level, the semantic content I propose here both for the Mari painting and the Assyrian “sacred tree” panel.28

Conceptions of Renewal in the Mari Painting

As a working hypothesis, I posit that the association between the terrestrial and celestial conveyed visually in the central panel of the “investiture” painting speaks to the presence in Old Babylonian Mari of an intellectual speculation on the relation between a primeval past, expressed through the terrestrial, and a possible conception of an ideal future, expressed through the celestial. This relation is presented within the paradigm of the periodic renewal of the cosmic order at a fundamental level as signaled by the outer composition and frame of the painting (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). The idea of renewal in the Mari painting is communicated to the viewer most immediately through an ideal, or paradisiac, garden (Figs. 2 and 5). It is further signaled through the occurrence in the painting’s imagery of the flowing vase, a motif not only symbolizing notions of agrarian fertility but also regeneration and purity, especially in its connection with the ancient Mesopotamian god of the sweet subterranean water sources and ritual purity, Enki/Ea.29 With its endlessly flowing streams of water gushing out of as limited in size an element as a small vessel, the flowing vase is surely a magical symbol whose meaning must not have been confined to agrarian abundance. In the painting, recurrent renewal is also signaled in the abstract by the frame of the running spirals surrounding the entire composition.

Renewal or regeneration in its basic sense is a seasonal matter in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly manifest in the celebration of the New Year’s festival in different states and periods throughout its history.30 As for the idea of a radical renewal of a world order already in existence, preceded by a total destruction thereof, it is preserved in one particular mythical incident, the Flood. While any instance of seasonal renewal associated with the calendar would have had relevance to the visual statement found in the Mari painting, a renewal of the cosmic order may be considered much more commensurate with the regal depth and importance of such a work of art. Thus, we can examine elements of the imagery and composition of the “investiture” painting in light of the paradigm offered by the “classical” Babylonian Flood myth, especially its aftermath in the form of the establishment of a paradisiac land of longevity in which the immortalized Flood Hero is placed.

The Flood story per se does not find figural expression in the art of ancient Mesopotamia. But its crucial place in the religious and intellectual perspective of this culture from at least the first half of the second millennium bce may be thought to have had its impact on the visual domain. As W. F. Albright underlined as early as 1919, the symbolism of the flowing vase cannot be divorced from some of the principal themes contained in the Flood myth, particularly the land of immortality to which the Flood Hero is transported in the aftermath of the Deluge.31 To that end, a reading of the Mari painting against the exemplar of the Babylonian Flood myth is an essential aspect of the present study.

The Flood Myth in the Old Babylonian Period

The Old Babylonian period witnessed the composition of the first extant literary texts containing the “classical” Flood story, the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs, or the Atra-ḫasīs Epic, which places the Flood within the larger framework of the creation of mankind by the gods, the Sumerian Flood Story, and the recently discovered Ark Tablet.32 As we have seen, the Sumerian King List, having taken its final form during the Isin Dynasty, also features the Flood as a benchmark in the historical scheme that it presents. The Old Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh included the figure of the Flood Hero as well, although perhaps not the Flood narrative itself.33 Thus, the prominent place of the Flood as a theme in major texts from the broader Old Babylonian period is clear.34

The most complete narrative account of the Flood to have survived from ancient Mesopotamia, however, is Tablet 11 of the Standard Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, redacted and collated in the Neo-Assyrian period. The striking parallels between the Flood stories found in this work and the Old Babylonian Poem of Atra-ḫasīs show that we are here dealing with a continuum.35 My engagement with the Flood story in relation to the Mari painting is primarily centered on the themes preserved in the two texts from the Old Babylonian period proper, the Poem of Atra-ḫasīs and the Sumerian Flood Story. In the meantime, however, I do not suppress aspects of the Standard Babylonian Gilgamesh relevant to the present perspective solely on the basis of the lateness of its date. Some of the themes and images this poem contains, not found explicitly in the extant literature from the Old Babylonian period, may represent ideas and modes of thought belonging to a deeper ancient Mesopotamian tradition, the ramifications of which would be of value in approaching some of the interpretive problems tackled with in this study.

Previous Interpretations

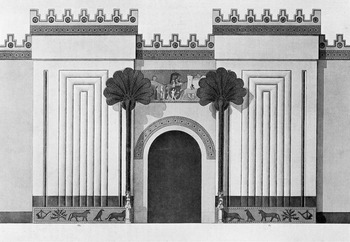

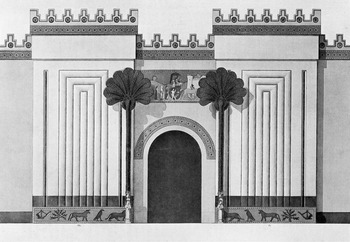

In the scholarship of the last several decades, an understanding of the “investiture” painting as the by and large faithful depiction of a real architectural or spatial locale either within or outside the palace at Mari seems to have been well established. This idea was first expounded in an article by Marie-Therèse Barrelet in 1950.36 Drawing a visual analogy among the “investiture” painting, the entrance to the Sîn Temple at Khorsabad from the Neo-Assyrian period (Fig. 15), and the Ishtar Gate in Babylon from the Neo-Babylonian (625–539 bce), Barrelet proposed that the “investiture” painting must depict, within ancient Mesopotamian representational conventions, the component parts of the Ishtar Temple excavated by Parrot to the west of the site, outside the palace.37

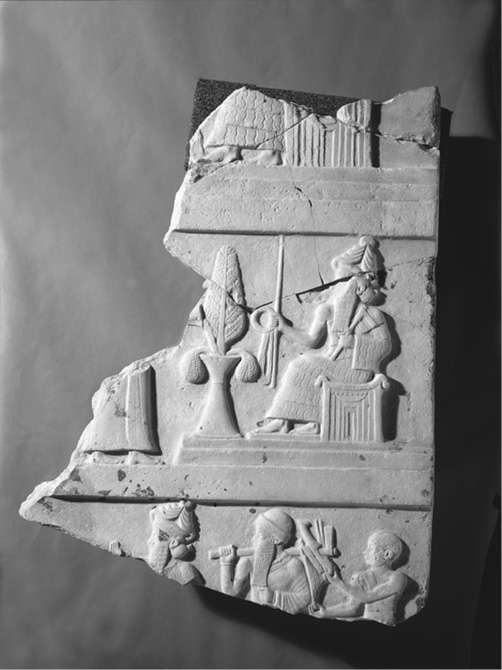

The Old Babylonian level of this temple, however, is completely unknown on account of the destruction caused by Hammurapi’s invasion around 1762 bce. Barrelet based her argument on the plan of the older, pre-Sargonic (Early Dynastic, ca. 2900–2334 bce), phase of the temple featuring an antecella and a shrine.38 She connected the bottom register of the central panel of the painting with such a putative antecella (Fig. 7). As sculptural comparisons to the two goddesses holding the flowing vase shown in the bottom register of the centerpiece of the painting, Barrelet pointed on the one hand to the statues of divine figures bearing the flowing vase and flanking the entrance of the Sîn Temple at Khorsabad (Fig. 15), and on the other to Mari’s very own statue of the goddess holding the same vase, found broken into several pieces in Room 64, part of the throne room suite, and Court 106 (Figs. 8 and 16). Barrelet saw the upper register of the central “investiture” panel as the representation of the inner shrine of the Mari Ishtar temple, where a potential hand-taking ritual, connected with an equally probable New Year’s festival, may have occurred (Fig. 7). She saw the fruiting date palms shown in the painting in connection with the cult of Ishtar and with natural trees one would have found planted in ancient Mesopotamian sacred precincts (Figs. 2 and 5). As for the trees closest to the central panel, so far unidentified botanically, she proposed that they may be representations of artificial trees, examples of which were found again at the entrance of the Sîn Temple at Khorsabad in the form of wooden cores covered with sheets of bronze.39

Barrelet drew an analogy between the figures shown on the glazed brick compositions flanking the same temple entrance at Khorsabad (Fig. 15), the Assyrian “astroglyphs,”40 and the fantastic animals represented in three registers between the natural date palm and the unidentified tree in the “investiture” painting (Figs. 2 and 5). She stated that the Mari figures must represent a similar wall decoration found in the Ishtar Temple. Finally, Barrelet pointed out the band of running spirals framing the Mari painting as a schematic representation of water, suggesting that this element of the composition, coupled with the large tutelary Lama goddesses behind the date palms, might be evoking an architectural and sculptural decoration in molded brick such as that found on the well-known Innin Temple of Karaindash in Uruk from the Kassite period.41

In his final archaeological report, as well as another publication, on the Mari paintings, Parrot praised Barrelet’s perspective, and finding her argument convincing, proposed only one amendment to it, in that he located the ritual thought to be represented in the scene not in a structure outside the palace but inside it.42 He considered the palm trees to have been planted in Court 131, which he identified with the “Court of Palms,” a designation textually attested but not identified archaeologically in the palace.43 He thought of the bottom register of the central scene as representing Room 64, connecting the statue of the goddess holding the flowing vase discovered partially in this room (Fig. 16) with the figures of the goddess holding the flowing vase shown in the painting. As for the band of running spirals, Parrot associated it with the painted faux marbre decoration found on the upper surface of the podium placed against the south wall of Room 64 (Figs. 8 and 17). Finally, he saw in the upper register of the central panel a rendition of Room 65, the throne room proper.44

Taking the spatial model characterizing all these interpretations to the extreme, and building on Parrot’s placing the scene inside the throne room suite, Yasin Al-Khalesi in his 1978 work located all the elements of the central panel of the “investiture” painting in Room (Sanctuary) 66, part of Room 65, reached by a flight of stairs.45 He understood the bands separating the two registers as a schematic representation of these stairs, and the frame of concentric bands surrounding the panel as a rendition of the recesses inside the doorway leading from Room 65 to Room 66. Even though often carefully articulated, such perspectives deny the “investiture” composition its full representational autonomy and semantic richness, making it a mere derivative in two dimensions of actual three dimensional objects or spatial and architectural elements. The strictly empirical focus on the image’s parallelism to real architecture has, for the most part, caused the rich metaphysical aspects embedded in the painting to be overlooked.

Alternative Views

In her work on wall painting and glazed brick tiles in the ancient Near East, Astrid Nunn has a brief treatment of the meaning of the “investiture” painting, in which she states that it would be deceptive to see in the central panel of the composition two architectural spaces one above the other.46 She aptly posits that the painting as a whole should rather be understood in symbolic terms, with elements of “actuality” also incorporated. Not favoring the usual perception that the scene involving the king and Ishtar depicts a clearly defined event or activity, she understands the image as showing the king in the act of experiencing the extraordinary, or the supernatural, in more fundamental terms. Nunn questions the common tendency in scholarship to associate ancient Near Eastern imagery all too readily with cultic procedures or concrete events, underscoring a purer symbolical dimension in its semantics.47

Among the few other interpretations of the painting outside the “pictorial imitation” model is Moortgat’s own brief treatment of it in his short monograph on wall painting in ancient Mesopotamia.48 Here, the archaeologist sees the composition as a schematic representation of the entire cosmos in mirror symmetry, ranging from the mountain scale pattern, the sign for the chthonic realm, with its mythological quadrupeds symbolizing the netherworld; across the vegetal world that nourishes both human and animal; up to the celestial gods in the firmament, with the blue bird in the air or high on top of the branches connoting the heavenly realm.49

Curiously enough, another symbolic interpretation comes from Parrot himself, who seems eventually to have acknowledged the paradisiac associations of the landscape scene in the painting, much later in his career, in his 1974 work on Mari. Drawing a parallel between the imagery of the painting and the description of Eden in the Book of Genesis, Parrot accepts that the Mari painting is certainly not an illustration of the relevant biblical passage, noting, however, that the resemblance is too strong to ignore.50 With such a statement, Parrot seems to have taken due notice of the primarily symbolic and conceptual nature of the painting, and moved away from the view that sees in it an actual locale inside or outside the palace at Mari. His observation that the four streams emanating from each of the Mari painting’s flowing vases evoke the notion of the four streams of paradise is also valuable for a reassessment of the meaning of the flowing vase in the study of ancient Mesopotamian art.

Also outside the “pictorial imitation” model is Alfred Haldar’s 1952 reading of the image as Ishtar’s delivering an oracle to the Mari king in association with the “New Year festival.”51 This interpretation is apt in its connecting the painting with the practice of prophecy, so prominent at the Mari court in the Old Babylonian period.52 Even though its literal perspective of seeing the imagery as a depiction of a clearly defined ritual act is not entirely commensurate with the present approach, Haldar’s interpretation offers a parallel to my emphasis on notions of temporality and the future informing practices of prophecy and divination in ancient Mesopotamia and arguably embedded in the “investiture” painting. After all, as is the primary argument of this book, the king may be shown here in the act of receiving the supreme oracle, the knowledge of the ultimate renewal of the cosmic order, from Ishtar as a deity of prophecy and regal fortune.

Finally, a recent detailed study of the painting by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and Ronan James Head has proposed a much needed symbolic interpretation, highlighing conceptions of royal renewal, with due emphasis on godlikeness, divinization, and priesthood.53 Even though this article may not be, strictly speaking, an art historical study, it sets a well-rounded precedent to my approach here, with its favoring comparison, especially biblical, and the integral traditions of the ancient Near East. There are certain overlaps between this study and mine in the reading of the visual motifs, but in the end, the specifics of framework and argument are also different enough in each endeavor.

A Critical Position

In the present essay, I, too, attempt to redress the limitations of the “pictorial imitation” approach to the Mari painting by arguing for the presence of a primarily symbolic semantic system in it. It is important to recognize the potential in the art of the ancient Near East of transcending specific events or clearly defined ritual activities in order to operate in a more fundamental semantic that has a primarily philosophical component. The architectural analogy, however, has utmost value as long as it is not applied literally and rigidly, equating all the elements of the painting with the real, known or putative, architectural features of the site of Mari. Elements of the painting must certainly be understood in reference to architecture, especially those that suggest doorways and stepped structures, be they stairs or stories, but in a cosmic rather than literal sense. Within my proposed symbolic system, it is more appropriate to talk about an architecture “not of this world,” representing transitional processes and graded hierarchies predominantly religious in nature. The architectural analogy has additional value in the interpretation of the central panel of the painting as an ideal enclosure crucial to conceptions of cosmic order, both primeval and future, in its sense both of an occluded subterranean enclosure and a heavenly temple.

Even though this study is not focused only on the “investiture” painting, the latter’s foundational quality in relation to the regal art of the Late Bronze and Iron Age empires of Western Asia calls for its detailed analysis. As such, the Mari painting functions here as a pilot image driving and guiding the study of a broader corpus of other images as well. Given the interconnectedness of the ancient Western Asian and Egyptian worlds, as well as the continuum in the language of images across the ages of Near Eastern antiquity, the analysis of the Mari painting should be carried out in tandem with that of other relevant images from Assyria, Babylonia, Egypt, and Anatolia, rather than in a vacuum defined only by the Kingdom of Mari and the Old Babylonian period. Barrelet’s work undertook such a diachronic analysis more than half a century ago, without, however, any engagement with the metaphysics of the art of the ancient Near East and Egypt. It is this additional task that the following chapters undertake.