1. Introduction

The metaphor of polyphony is useful to convey the idea of polychrony. Around the 12th century, the echoic/reverberant cathedral of Notre Dame was an experimental laboratory, a sonic supercollider for staging tonal collisions of multiple, interwoven monody while trying to stabilise and control the complex frequential interactions. Yet further, amidst this complexity of diffraction and reflection, lingered a kind of ghostly quality of reverberant presence, a fuzziness or blurriness of the now – though not the first encounter of memory and echo in history.Footnote 1 A few centuries later, in a period of revolutionary neo-scientific innovation, the field of music was profoundly influenced by the empirical, mathematical, and technological innovation of the time.Footnote 2 In the 16th to 18th centuries in particular, mathematical systems of pitch temperament were liberally experimented with, complementing Rameau’s work in functional vertical/chordal harmony. The clavier was in its time the orrery (planetarium) of the music world, mechanistically modeling the intricate relationships of the tonal orbits – a conformalisationFootnote 3 of theory and mechanism. It was also a time of early experimental acoustics: that sound needs a medium (Boyle), how distance affects echo delay (Mersenne), and the calculation of the speed of sound (Newton).

Our experiments, as the following reports show, focus exclusively on tempering the horizontal aspect of the sonic (time) rather than the vertical aspect of harmonisation, revisiting that ghostly, echoic phenomenon of the gothic cathedral – albeit on a global scale. This is accomplished by manipulating network latency with live audio buffers using a customised Max for Live device called the Netronome. Network music practice eventually brings with it an awe-inspiring appreciation of latency, but at first encounter this latency-saturated environment feels like temporal quicksand. This article is about our human-technological response to playing music in highly disjointed chron[i]logical environments – like a hall of mirrors.

Signaletic latency in general (sound/light/impulse) is straightforwardly an emergent property of distance. Distance is a physical medium (a metaxy – the in-between); thus, distance is already (somehow) a signal delay buffer as nature.Footnote 4 Networks are simply thin conduits of space-time, having the advantage of addressability. We can then encode and send our sonic signaletic messages to remote locations (in the future) while injecting a small amount of configurability into their coordinate systems (timeline). As such, we can transform our temporal quicksand into a properly striated space. Thus, keep in mind as the discussion of polychrony and temporal fusion proceeds that we are not engaging in metaphysics, but an architech-chronics. The experiment we constructed to confirm the framework is a distributed, multi-offset (due to latency) rhythmic problem with a circular-ringed score that can be shared and updated live from anywhere in the world.

2. The chronotechnics

Music representation commonly limns in the range of frequency and the domain of time, wherein both there is a need for fine and coarse differentiation. In the range of frequency, we coarsely differentiate zones of pitch, which then may require finer adjustments microtonally when we deal with modes – quarter steps and less. Then, there may be a need beyond even the Helmholtz-EllisianFootnote 5 realm, where the finest levels of quanta are required to deal with microtonal representation on the level of cents and hertz (Sabat and Nicholson Reference Sabat and Nicholson2020, p.72).

In the domain of time, we coarsely differentiate into beats and subdivisions but may further differentiate when it comes to quantisation and finer modal adjustments of beat offset or swing. There is also the idea described succinctly by Curtis Roads that the ear discerns microsonic effects on the order of milli-, micro-, and nano-seconds, corresponding to specific frequential, spatial, and timbral phenomena (phase, delay, comb, high and low pass). The point being that we can explain (represent) much sonic phenomenon, including certain loudness effects, in the singular domain of the temporal (Roads Reference Roads2001, p.5).

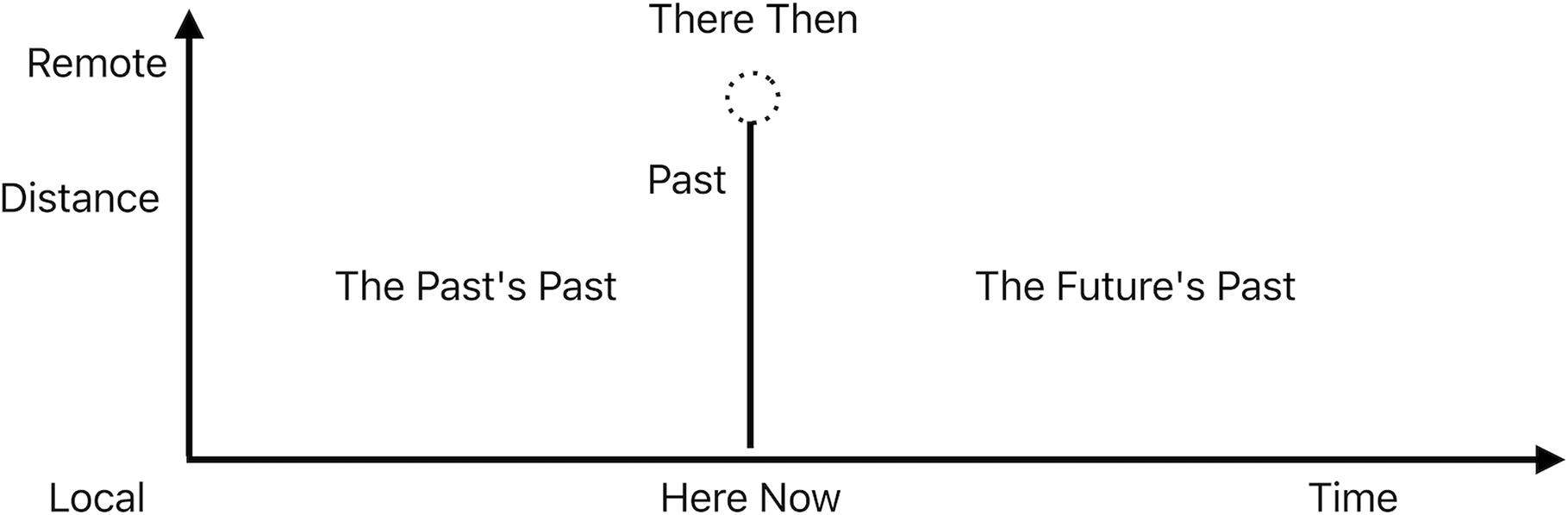

The collapsing of frequency and time dimensions into a singular domain then frees up the range dimension to accommodate a spatial representation (distance). This provides a framework to talk about the practice of networked music, whose defining feature (at first glance) is that of space: the planetary distribution of performance nodes. Thus, our range value (y) now represents space, or rather distance, while progressive time (and all its sonic phenomena) resides on the x-axis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Here and now; there and then.

To fit the three dimensions of space into one vertical dimension requires that we just use distance from here – a local point of reference. In other words, the zero point of our range variable can indicate the local node of a network music event, while the extension represents the remote.

Keep in mind, however, that in a multi-nodal or trans-local (Doruff Reference Doruff2006) network music performance, the local is actually all of the singular perspectives of the situated observers in the network all at once. Everyone considers their own point of view the here-and-now, while the other nodes are the there-and-then. And there we have the first strange attractor of network music: there is actually no universal now (downbeat) that two observers in the system can agree upon. The topic is subtle, so let us just say initially that when network musicians play together, no one is experiencing the same musical reality (Caceres and Renaud Reference Caceres and Renaud2008, 5); they are all indeed playing one piece, participating in one event, yet it manifests differently at each node because of the temporal offset.

Sound traveling at the speed of light over fiber-optic cables takes around 110 ms to get across the Pacific Ocean (Caceres Reference Caceres, Hamilton, Iyer, Chafe and Wang2008, 64). So what is this distance we’ve been talking about, except for time? Network music’s distinguishing feature is apparently not about space; it is about time (latency). This idea was mentioned in an earlier paper by the author, as originally inspired by Bakhtin’s idea of the ChronotopeFootnote 6 (time-space) (Fields Reference Fields2012, 86). In the ontological sense then, when referring to time-spaces in network music, we would be concerned firstly with the temporal aspect of spatial distance (latency alone) and secondly, the potential for offset temporal fusion implied in the trans-local. Thus a temporal intricacy manifests in the weaving of signals that originate from and terminate in multiple locations in a complex way, such that each node carries the imprint of other-local (other-worldly) temporality – a fusion of now and multiple thens.

Music performances engaging with non-tempered (in the wild) complex network topologies are technically, mathematically, and in practice, cognitively daunting. Only in art have humans had some preparation for this loss of the instinctually organic here and now. Thus, as art, physics, and networks converge in a historical way, we would expect to see more of a developed theory that discusses this evolutionary moment.Footnote 7 We do find a foundation for discourse in the chronopoetics of Wolfgang Ernst, who speaks of time-criticality in the field of media archeology as:

“a field of knowledge originated by media and their analysis. It includes concepts like real time, time axis manipulation, as well as the actualization of stored time signals and the temporalizing variants of Aristotelian metaxy, which in this sense means not only the spatial in-between as media channel, but also media-technically the temporal in-between, the smallest memory buffers and signal delays” (Ernst Reference Ernst2016, 4).

However, as Ernst’s temporal in-between stops just short of a more plural chrono-technic that could account for the temporal fusion implicated in trans-local performances, then the Caceres and Renaud paper stating in 2008 that “a consistent framework to understand it is still to be developed” (Caceres and Renaud Reference Caceres and Renaud2008, 6) still stands. While this is what motivates the idea of the well-tempered network in general, the attempt in this discussion hopes to strike a balance between the speculative and the practical. Moving forward, in the context of this issue’s theme, the focus will be on how one can approach the notation of networked rhythmic events without ignoring the notion of what makes these experiments interesting in the first place.

3. Original inspiration

The Antikythera mechanism (Figure 2) lends itself as an ideal model for network music’s intricate inter-nodal relationality. The Antikythera is a 2000-year-old mechanical model of the solar system, used to predict cosmological movements and events (Freeth et al. Reference Freeth, Higgon, Dacanalis, MacDonald, Georgakopoulou and Wojcik2021). As a whole, it is a coordinated, rational system of multiply interconnected gears/cycles, moving in a mechanised dance of cosmotechnics (Hui Reference Hui2021). The Netronome, an algorithmic mechanism developed for this project, attempts to do the same as the ancient Greeks: create a model of some predictability and control to temper the irrationalFootnote 8 and infinite potential, though of a networked nature.

Figure 2. Diagram of the Antikythera mechanism.

In the model of the Antikythera, picture the gear’s teeth as musical beats per cycle/loop. The gears may be directly latched together, node to node, or be related distantly through the medium of inter-ratio mechanical computation. In an analog process, the model will synchronise to the more distant nodes by the addition/subtraction of the diameters of the gears and the numbers of teeth. For the Netronome syncing audio over networks, this is accomplished by adding intervening audio buffers to create latency and subtraction by working with flexible rhythmic strategies (subdivisions/polyrhythms) to make patterns fit together. In this way, we can envision tempering the networked world via the wisdom of Pythagoras and Euclid (more on Euclidean rhythms below).

4. The network

As a physical entity, the acoustic space of the network depends on a globally distributed assemblage of conduits and technologies. An actual online music event, composed of a definitive number of nodes/locations, begins to collapse this vast potential of acoustic space into a real entity with length, duration, and quality, the physical nature of which is constructed for the optimal passage of electrons and photons. The integrity of the encoded sound information must be maintained through numerous transformations and conversions: acoustic, mechanical, electrical, optical, and with several buffer diversions (software/hardware). In this space, we can get very creative with network time delay by using audio buffering (Chafe and Gurevich Reference Chafe and Gurevich2004; Gurevich and Chafe Reference Gurevich, Chafe, Leslie and Tyan2004) – the process that we’re calling tempering.

A well-tempered network is a virtualised temporal layer whereby each edge latency becomes tunable by intervening audio buffers. Carôt categorised this as the fake-time approach (Carôt and Werner Reference Carôt and Werner2007). This paper frames the network latency issue as a malleable continuum: consequential and real. As such, there are two approaches to take toward such attunement: the bottom-up approach attempts to touch the natural tendency of this geochronometry of distance as lightly as possible – or not at all – challenging musicians to go with the temporal flow. In the top-down approach, the composer can ignore the latency situation altogether and specify any rhythmic value by adjusting audio buffers to artificially create predictable conditions that thereby afford a designing scenario (making scores). The first approach dictates the enfolded poly-tempi and poly-rhythms implicit in the morphology of the network; the second approach is an explicitly familiar rhythmic space – though infused, of course, by the strange quality of toporhythmia (place rhythm; see below). Such is the networked temporal continuum: from the organic given (reticula naturans) to the artificially built (reticula naturata). The reader may refer to more dedicated literature on the history and development of the numerous systems and approaches addressing the cultivation of network space for music creation (Barbosa Reference Barbosa2003; Rebelo Reference Rebelo2009; Renaud et al. Reference Renaud, Carôt and Rebelo2007).

5. The Netronome

The NetronomeFootnote 9 is a utility (M4L Ableton Live Plugin or Max patch) that measures the total roundtrip audio latency to and from a Jacktrip hubserverFootnote 10 (Caceres, Reference Caceres and Chafe2009), and tunes this echo time symmetricallyFootnote 11 to a specific note value at a chosen beat per minute (i.e., a quarter note at 120 bpm equals 500 ms–250 ms to the server and 250 ms back). The hub server is a point through which all signals travel. Each edge carries audio bidirectionally. An early Weinberg paper would call such a network structure of nodes and edges a flower topology (Weinberg Reference Weinberg2005, p.34). In an actual situation, the edges of the flower would likely be of different lengths (making an asymmetric flower). The Netronome’s job is to make the flower perfectly symmetrical, such that all the edges are of the same note value (or subdivision). With that, all notes to and from the server are synchronised to a common pulse. Hence, the networked metronome (Netronome).

A system of distributed Netronomes (each node of an ensemble) creates a virtual temporal matrix. All sound goes through the matrix; the audio channels of the Netronome thus become an integral part of the overall signal path. The Netronome sends and receives its audio to/from a local Jacktrip client via a virtual audio driver.Footnote 12 A significant methodological implication for network music then becomes this essential practice of temporal fine-tuning that one rehearses with the audio server. All musicians in the ensemble calibrate their delays independently previous to rehearsals and performances. Once the delay is known, it should not change significantly, though the Netronome can fine-tune the delay by ear in millisecond increments if needed. In networked music, edge control (latency tuning) becomes a genuinely creative aspect of composition.

In Figure 3, as an M4L object, the Netronome’s BPM value and time signature follow Ableton’s metronome settings. The process starts by sending the latency calibration signal to the server, which echoes that back. A signal difference measuring functionFootnote 13 aligns the current beat with the echoed beat. With a note length of 1000 ms (quarter note at 60 bpm), if the latency box were to find a server echo time of 200 ms, for example, the adjusted added time would need to be 800 ms. 200 ms network delay + 800 ms buffer delay (400 ms before output bus and 400ms after input bus) = 1000 ms. The figure shows both the ToJackTrip and FromJackTrip plugins. The ToJackTrip object usually goes in an Ableton Return track (routed to the Jacktrip client), so all tracks that need to be sent to a remote ensemble would be sent to that Return track. The FromJackTrip object goes in an audio track, receiving the return signal back from the Jacktrip client through the loopback device. By using time signatures and note values creatively, net musicians can explore the infinite possibilities of multi-nodal structured rhythms.

Figure 3. Netronome as a Max for Live object (M4L). Calculates server echo time and adjusts round trip latency to a desired note value. https://github.com/pparocza/Netronome.

6. Netronomia: Circle score overview

To date, the networked circular/ringed scores we have iterated for this study are titled Netronomia (I and II). The first version, for three nodes, was developed by Ethan CaykoFootnote 14 in 2023 using a p2p-like network topology; the Jacktrip hubserver was still used for convenience, but a remote desktop connection was used to make manual peer routings through the server – an obviously negative factor for scaling the size of performances (but not a detractor at this point in the project). In this piece, Cayko is exploring the concept of toporhythmia (place rhythms), described in his master thesis of 2012 as the multiple nodal facets of a network piece (more detail below) – what Caceres and Renaud term as bi-located patterns (Caceres & Renaud, 5). The circular/ringed score was a key decision in representing this intricate tapestry of rhythms as an optimal form for providing a focal (gestalt) experience for the musicians. In other words, the circular morphology provides immediate insight into the distributed nature of and immediate awareness into the concurrency of the trans-local state. Cayko hardcoded parts as presets in what was recognised as a less-than-dynamic situation – but again, appropriate for this first study.

Netronomia II was created by the author and Chinese developer Yanpeng Chen for five nodes in 2024, using a much more automated Netronome process in a server-centric topology, which cuts down on the technical setup time by magnitudes. The score development has made strides also, using socket.ioFootnote 15 (for inter-score communication) with a “dashboard” interface that controls the behavior of the distributed score system. The dashboard can load and step through midi files to display, transform, and transmit the visual patterns to each of the rings independently on the remote circular scores. The scores then maintain a continual state of sync; any local change is reflected globally. Inter-score communication with socket.io is rather seamless in function as compared to the author’s earlier score system module as included in the highly engineered ArtsmeshFootnote 16 software. Hajdu and Didkovsky surveyed other early prototype networked systems up to 2009 that implemented distributed notation solutions (Hajdu and Didkovsky Reference Hajdu and Didkovsky2009). Craig Vear discusses more recent and defining aspects of distribution and communication between digital scores in his recent book on The Digital Score (Vear Reference Vear2019, 134).

The Netronomia II score system maintains the current state of the whole networked performance environment, such as the name and number of performers, actual network delay values compared to the adjusted delay values of each node, and bpm and time signature for the piece. For better or worse, in Netronomia II, everyone is seeing the same score. Netronomia I, on the other hand, was hardcoded with a customised display for each musician as to what was actually being heard at each location regarding the offset beats. Thus, what Netronomia II gained in efficiency by synchronising with inter-score communication might have been lost in the more monolithic view. Both versions of Netronomia were coded in the Processing/P5.js-based format and are conveniently stored and accessed on the Openprocessing site.Footnote 17 They are easily edited online in real-time for the immediate demands of a performance, yet the code runs locally in a browser at each node.

The name of the piece, a neologism, comes from a kind of mental aphasia that often occurs in the thick of network music practice and which we started to call netronomia (as in “I have a bad case of netronomia”). It is commonly experienced as a buzzing confusion or weirdly wired disorientation that comes from the loss of a stable here-and-now and being overwhelmed by labyrinthine signal paths and topo-variant phenomena echoing through our constructed trans-local matrixes. The human brain has no special neurons (yet) for trans-local, time-space fusion. To colleagues who have successfully navigated the shallows of inter-audio loopback communication, only to emerge into the turbulent whirlpools of hubserver modes, it is to you, previous sufferers of this undiagnosed psychopathology, that we dedicate these scores. It is intended that the Netronomia circular score will be an extended series of iterations and performances; it is more a template and method to be varied and evolved.

7. Netronomia I

The first version for three nodes consists of acoustic instrumentation: Vermont/bass, Santa Barbara/cello, and Beijing/guqin.Footnote 18 Cayko made three circular scores with preset Euclidean rhythms (Figure 4), defined as having “the mathematical property that their onset patterns are distributed as evenly as possible: they maximize the sum of the Euclidean distances between all pairs of onsets, viewing onsets as points on a circle” (Demaine et al. Reference Demaine, Gomez-Martin, Meijer, Rappaport, Taslakian, Toussaint, Winograd and Wood2007). Thus, it was supposed that several Euclidean rhythms together with the property of “maximum evenness” would sound optimal together in the topo-variant environment. Cayko’s study focuses exclusively on choreographed rhythm, the hardest nut to crack in network music.Footnote 19

Figure 4. Part I of Ethan Cayko’s piece, Netronomia. Three parts: Vermont/bass (green), Santa Barbara/cello (blue), and Beijing/guqin (red).

Cayko’s piece stems from his master’s thesis, Rhythmic Topologies and the Manifold Nature of Network Music Performance, on the technique of toporhythmic composition (Cayko Reference Cayko2012). In the composition of toporhythms (place rhythms), a netronomic function is used to tune the network time between performers to the desired beat value and tempo. As he describes it, the toporhythm technique “creates a rhythmic topology between performers that can be utilized to create distributed patterns. These patterns unfold differently in each performance space, resulting in a manifold music” (Ibid, p.ii). In other words, due to the temporal offset between musicians in network music, a single music piece exhibits as many different facets as there are nodes in a performance. The following examples from Cayko’s thesis demonstrate the issue:

In Figure 5, the nodes are separated by a quarter note. A rhythmic pattern initiated at node one (N1) is synchronously duplicated at node two (N2). Due to the temporal offset between the nodes, the aggregate result at node one reflects a different rhythm from node two.

Figure 5. Toporhythm with two nodes.

Continuing, in Figure 6, Cayko adds the terms initiate node (IN), penultimate node (PN), and terminal node (TN). At this point in the piece, N3 is the IN, N1 is the PN, and N2 is the TN. TN can synchronise with both IN and PN nodes, but notice that the aggregate rhythms at the other nodes are both different.

Figure 6. Toporhythm with three nodes.

For his latest experiment with toporhythms, Cayko is experimenting with Euclidean rhythms and a circular score with rings. Figure 7 shows Part I of the Beijing score (Guqin, red) for Netronomia with Vermont (bass, green) and Santa Barbara (cello, blue) nodes in the inner rings.Footnote 20 The three independent rings each have three preset rhythms, which will be cycled through in three minutes. Each node will see their own part in the outer ring, with their collaborators’ parts in the inner rings. The tempo is 100 BPM; the duration of a quarter note at this tempo is 600 ms (the next section will deal more explicitly with the tempo calculation process as to not burden the text here). Cayko also provides pitch sets for the musicians to improvise around. The most important point here is that the musicians are each looking at the three different aspects of one score, as their partner’s offset beats are explicitly notated as to what is actually locally heard (review Figure 4). For example, notice that Beijing’s (red) downbeat on the top of the circle coincides with the end of a sequence of four quarter notes from SB (blue) and Vermont (green), meaning that Beijing is playing with notes sent in the past: a quarter note ago in the case of SB and a half note ago in the case of Vermont (verify in the companion scores of fig 4).Footnote 21 The row offset button function (to the right and bottom of the score) was designed to rotate any one of the rings counterclockwise or clockwise any number of ticks to provide the composer (or players/listeners) with a kind of visual calculator to gauge how rhythms (after delay) would actually be heard at any of the other nodes. Used creatively, it can also be shifted during a performance for interesting transitions during a performance.

Figure 7. Circular Score with Three Parts (guqin view); the local ring being the outer ring.

When listening to the three different versions, one definitely hears the emphases of the phrases differently. Each time the musicians go around the ring score, it gives them another chance to settle into the pocket of the rhythm and to come to more of a sense of the character of the three-node rhythmic-temporal fusion. There is no more subtle way to investigate (feel) the actual empirical phenomenon of relativity (as the musicians do here) than that of musical sensitivity, which goes beyond the millisecond to that of laying back or leaning forward into the magnetism (attraction and repulsion) of each of the beat foci – with each performance node perceiving that focus differently. Though on different beats, they are entraining on an expanded sense of simultaneity. They are in another sense getting used to a prosthesis (the network), feeling their distal counterparts through the phenomenological continuum of three distinct and yet overlapping time-spaces. Cayko, as the initiate node, must keep the pulse moving forward without overly compensating for the hits and misses of the other remote nodes. With networked loop forms, the settled groove means a successful and stable time-space fusion.

Toporhythmia due to temporal displacement is a feature of network music, not a bug. It is not a problem that should be compensated for, even if there were a quantumly entangled way to do so. As further food for thought, network music reveals this phenomenon as present in co-located music also, though hidden or implicated. When separated by distance (in a juxtaposition of trans-localities), this phenomenon of manifoldness becomes explicate.Footnote 22 The multi-faceted aspect of network music becomes exponentially complex with each additional node that joins and progressively challenges the comprehension of the musical psyche to organise such. Here resides a new challenge for music representation and digital score innovation. Previous to music performance over networks, there was no need, nor conception even, of what could lie beyond mono-chronal perspectives in music, so implicit was it to the human experience of locality – though not an unknown idea in literature since Bakhtin’s theory of the polyphonic novel (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin1984). Now, the aspect of polychronicity can’t be ignored.

8. Process notes

The following notes give a sense of the tortuous process of manually tuning a network using the first prototype of the Netronome. To start, a network pingFootnote 23 was done, and the rest was tuned by ear with a metronome pulse being fed to a microphone on one end, while on the other end, a technician held a microphone close to his headphone speaker to feed the signal back. In short, the metronome’s sound pulse (n – 1) went from one node to the other and back, where it then aligned with the next current pulse (n) of the metronome.

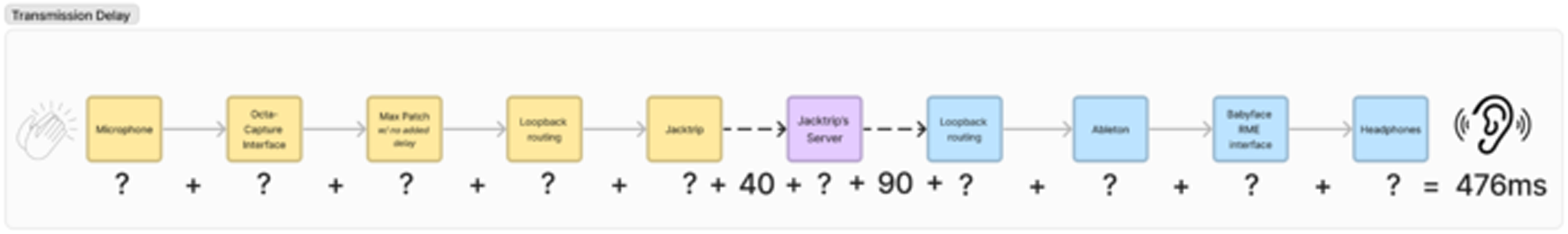

Network ping times to the server are thus only a part of the signal path, but a good minimum estimate to use. For example, in Cayko’s experiments, node A’s ping time to the server was ∼80 ms (40 ms one-way); node B’s ping time to the server was ∼180 ms (90 ms one-way). What the ping times suggest is that the one-way latency contributed by the network between the two parties should be more than 130 ms (40 + 90 = 130). The network was tuned by finding a tempo at which the round-trip metronome click was a quarter note, which turned out to be 63 bpm – which meant that the real perceived round-trip latency was ∼952 ms (60000/63 = 952.4), or a one-way latency of 476 ms. It also means that 346 milliseconds (476-130) were being introduced by other factors not accounted for in the network ping, such as mic cable lengths, analog/digital conversion, hardware and software buffers, server audio routing, etc. Hence, the more inclusive term “transmission” delay is more descriptive of the facts than simply network delay (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Actual Factors in Transmission Delay. The image is too small to read, but there is a microphone/cable/mixer/headphone input/output stage, hardware converters, multiple software buffers, network delays, times two. The reaction times of a body/brain (organism) could also be included in a discussion of transmission delay path.

After finding that transmission delay with no added latency in the Max patch (1st iteration of the Netronome), it was decided to pick 100 bpm and attempt to tune to a half note (600 ms one way – 1200 round trip). Because the participants knew that the real latency was 476 one-way and that the desired one-way delay was 600, it meant they could simply type in 124 ms to the delay compensation buffers at both nodes, maintaining symmetry between send and receive signal paths.

It was then noticed that node B was routing audio through Ableton before going to his headphones, while Ableton had an I/O buffer size of 512. We switched that to 64 to minimise its contribution to the latency and re-tuned. That adjustment made it so we were perfectly aligned at 107 bpm (∼560 ms) instead of 100 bpm (600 ms), which means that change reduced the latency by 40 ms. We then entered 144 (124 + 20 ms) into both of our patches, and it was back to spot on at 100 bpm.

Such is the challenge of a manual tuning of network latency. It means, or has meant in the past, that the amount of technical preparation for a network music performance has persistently far exceeded the time for rehearsing musical content. This was an important motivation for developing an automated Netronomic tuning process.

9. Netronomia II

Netronomia II for five networked musicians took place one year after Cayko’s version. The instrumentation consisted of five playersFootnote 24 this time using Ableton instruments, as the latest version of the Netronome now comes as a Max for Live (M4L) device as well as a stand-alone Max patch. Netronomia II demonstrates a three-component score system: the Netronome, a score management interface (dashboard), and the distributed circle scores for any number of remote players. The dashboard (Figure 9, left) can be operated by someone not playing an instrument in the performance. The operator takes on the role of entering the players’ names and latency status, which consists of actual network latency (derived from the Netronome calculation)Footnote 25 and the adjusted latency – that which the group decides as a whole to tune to. As players are entered, nodes appear on the dashboard’s nodal graphs, and at the same time, empty rings appear on all the circle scores running on the internet (Figure 9, right). The patterns are staged on a grid at the bottom of the node graph area, either by loading precomposed midi data files or by using the built-in algorithm that instantiates a random Euclidean-like distribution of beats of some chosen density. With all players entered, the data is then sent out to all the remote scores on the internet via socket.io, each performance having a unique port number for communication between just those scores. The score operator will advance the patterns during play, or alternatively, the scores can be composed in real time in the staging area, edited, and then sent out to the ensemble.

Figure 9. Netronomia II dashboard score (left): creates nodes with colored ring counterparts on the circle score (right), one for each participant – establishing and advancing the patterns in real-time.

For Netronomia II, two of the musicians experimented with composing together to create the five sparse individual parts. The intention was to avoid a densely filled, generic-sounding rhythmic space where players would certainly lose the awareness in performance of who was doing what. With the tempo locked in at 60 bpm (1000 ms quarter notes), the first musician ran his Ableton transport, initialising an empty four-measure loop with overdub recording engaged, and entered a couple notes. The second musician manually synchronised his transport to the first musician, also instantiating an empty four-measure loop, and engaged the overdub record function. Both musicians were then in live looping mode. Ableton has a Link function to synchronise musicians only on the same local network. In this scenario, the second musician had to start and ‘nudge’ their transport a couple of times until the sync was perfect.Footnote 26 In this way, a most enjoyable loop space was created between the musicians separated in time by one second. Slowly, notes were added and subtracted, moved, or transposed until 5 parts were made – each twelve measures long. We could stop and start our loops at any time but kept Ableton’s transport running all the time so as not to have to resync the transports. In the end we export five separate midi tracks for importing into the circle score for the performance.

Both versions of Netronomia are toporhythmic studies, so we compose knowingly – with multiple versions in mind (forgoing one ideal version). Instruments had a degree of freedom with pitch or timbre by use of hardware controllers. The articulation of some timbre change provided an element of contour to the loop – which helped to create an awareness of the top of the circular trajectory. The timbre palette for five instruments wasn’t left to chance. It is especially helpful in the network scenario that instrument classes be distinguishable and complementary roughly, say by frequency range (SATB) or spectral quality (sampled, synthetic, wet/dry). Netronomia II is only twelve measures long (as was Netronomia I); with four measures loading into the circle score at one time, we had three loop patterns to play with (Figure 10). The idea was to stick to the loop until it cohered, and then some, giving the score operator a flexible signal for when to move on to the next loop system. It was interesting to see the average TTC (time to coherence) for these sections improve over time as musicians got more familiar with the circular score.Footnote 27 Signaling the time of score transition on the network can be done a number of ways: it can be timed, the score operator can make the creative decision, or players can agree to drop out when they feel it’s time to load the next loop. We opted for strategically dropping out, introducing a short silence. The score was then updated for the next section, the players saw their new part, and once again entered in a staggered manner following the initiate node (outer ring). For more strategies on using dynamic cues on the network, Alain Renaud has covered the topic most extensively (Renaud, Reference Renaud2010).

Figure 10. Netronomia II circle score (following Cayko’s design) displays four measures of a midi file pattern at a time. Advancing the midi file (turning the page) is controlled from the dashboard score from anywhere in the world. Patterns may also be shifted left-right by eighth notes.

Confirmation of the toporhythmic phenomenon comes finally in the version reveal afterparty. Each node records their local version: five nodes, five versions. The strategy for cued entrances in this piece was that the outer ring was the initiating node; each musician played in reference to the outer ring’s part but entered in the order of outermost rings first. Composers can roughly plan how offset beats will be received by row shifting during the composing process (shifting the midi notes left or right), and this can also be confirmed visually in the circle score via a shift counter/clockwise function. However, it is still a harrowing exercise to try to grasp, in our case, a five-dimensional sculpture. For that’s what it’s like: an artist can move around a sculpture to try to capture the different shades and aspects of their object, but he’ll never be able to see all aspects at once. Figure 11 shows an example of the toporhythmic effect in Netronomia II. Figure 12 shows an analysis of the audio file that confirms the expected results.Footnote 28

Figure 11. Toporhthymic Effect. Left: Netronomia II, original score, part 1. Right: showing the expected offset beats at the Shijiazhuang node (SJZ) – 2nd ring from center, where the player is following the Beijing initiate node – outer ring. SJZ plays on beat 2 and beat 3&. All other nodes who are also playing with the outer ring will arrive one quarter note delayed in SJZ.

Figure 12. This is the audio analysis of the expected outcome in SJZ. SJZ is purple, labeled by the players initials, ‘jy.’ Jy plays accurately on beat 2 and beat 3& with Beijing (light blue, labeled ‘k’) that just shows k’s downbeats on beat 1 in the analysis. As confirmation of the quarter note delays with other parts, see the yellow dots: labeled ‘x.’ X at the Inner Mongolia node (2nd ring), is following k also; most of x’s beats fall on beat 4. Notice however how his beats arrive consistently synchronised with k’s beats on beat 1 in SJZ. While L’s notes from Wuhan are mostly consistent (dark blue), he has made a mistake in measure 1. J in Beijing (red) on the other hand, following k also, must be playing his two consecutive beats early starting on beat 4 for him to arriving in SJZ on beat 1, which is a mistake.

10. Reflections

The circular, ring score developed by Cayko set a strong direction for this project, both in design and in the fact that it morphologically suggested that loops would be the musical form of choice in our exploration of toporhythms – and beyond to polychony. Critically, the loop form proved profoundly revelatory of the phenomenon of polychrony (not just the idea). Loop structures set up a canvas of flexible duration (duree)Footnote 29 to work in; the repetition allows for the stabilisation of the temporal frame to set, which consequentially then facilitates an expansion of presence inside the chronotopal fusion. Future versions call for independently configurable ring lengths and subdivision parameters, allowing for polyrhythms and a much more subtle exploration of networked topologies.

In addition, given the limited time to introduce traditional music players into the weirdness of the networked music space, the circular score provides an intuitive mapping of the musical parameters, without needing to be overly concerned about the challenges that the technicians went through to produce a tuned network for the performance. Cayko decided not to animate the circle in any way (rotating or having a position pointer), as players cannot as yet depend on a globally distributed visual sync.Footnote 30 The rhythms were kept simple enough to be memorised, such that after a couple of rounds, the score was meant to recede into the background, leaving only the engagement of the ear. Netronomia was a springboard for how to make the circle score more interactive and responsive for a wider range of musical possibilities.

The further engineered Netronomia II score system certainly achieved an elegant solution: automating the network tuning process, dynamically placing players on the score, loading midi files, which affords precomposition, sending out the patterns to a globally distributed ensemble with the click of a button, real-time updating of scores, and playing in perfect synchronisation to a measured pulse from anywhere on the planet. However, with Netronomia II, all participants read an identical score, without notating for each player their unique toporhythmic case according to their location (as Cayko did in Netronomia I). However, one of the purposes of Netronomia II was to scale. While the careful design of toporhythms can be done in bi- and tri-local settings, five-node performances cross a threshold where other qualities related to a higher order of complexity begin to attract attention. Thus, the toporhythm mining had to be pushed to the post-performance analysis stage (the version reveal party). Netronomia II, instead, was more about time and less about space: Chronos more than Topos.

I’m looking forward to future Netronomia projects; scaling up still continues to be the trajectory. But at the same time, a review and synthesis of these projects allows for the incorporation of lessons learned – for example, to maintain the convenience of global control and communication, yet allow local scores their autonomy of perspective. Technically, we have to wonder if 10 or 20 rings will still be legible to the eye, or shall we have a constellation of simpler rings, like the connected gears of the Antikythera mechanism (see above)?Footnote 31

Currently, the Netronome, inspired by the ability of local transport to sync with Ableton Link,Footnote 32 is experimenting with a global transport sync technique. Something like this was proposed in Oda and Fiebrink (Reference Oda and Fiebrink2016), which used GPS to synchronise system clocks. The author previously experimented (ineffectively) with a technique using Apple’s system clockFootnote 33 to synchronously trigger transport processes in parallel using the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) standard. However, the discussion must be limited here.

11. Conclusion

The acoustic behavior of any given networked configuration can be virtualised to create a temporally coherent time-space. In other words, it can be quantised or tempered, such that musicians are able to coordinate using musically sensible terms. The benefit of this mediated time environment is that network musicians can finally approach the networked space in somewhat familiar terms. As experience mounts, however, the given physical incoherencies of complex network timings (the irrational) can be re-approached creatively, in a finely tempered manner.Footnote 34 With some control and predictability, scores can be designed to tap the creative potential latent in any particular complex network topology. If scores have been a necessary tool thus far as an aid to cohere the many voices in localised scenarios, one can imagine how they will be doubly critical to new networked music practices, in which musicians must navigate unintuitive trans-local temporalities that are only now being encountered for the first time in history.

It is understandable that musicians in the first 20 years of networked music have been slow to embrace this new practice, with all its black-boxed metaxy.Footnote 35 Like the theory of relativity awaiting its Eddington’s Eclipse Experiment moment,Footnote 36 network music will have its proof with tempered time-spaces. The networked music future presents an opportunity for transcending mundane conceptions of mono-chronal time, facing a challenge much like when the reverberant/echoic gothic cathedral physically inspired experimentation with pluralistic monophony as it strove toward harmonically coherent polyphony. Imagine the activity of the neural circuitry of those early polyphonists, Leonine and Perotin, immersed in the wild of those architecturally rich wavefronts of Notre Dame. The global network is that new architectural wonder that will house the transition in music from monochrony to polychrony as we innovate new techniques and distributed scores to support this. Much further in the future, we will certainly be faced by complex interplanetary musical scenarios. As such, musicians will no longer be only distant in time; they will also be moving targets.

While it is understood that no signal can travel faster than the speed of light, this certainly doesn’t rule out the fact that musical sense/meaning can’t be generated in multiple time spaces synchronously – allowing this one last neologism, transchronal-aisthesia.Footnote 37 Classical theory (Shannon and Weaver Reference Shannon and Weaver1949) is framed as a transmission model (sender, content, noise, receiver). Enactivism frames communication as participatory sense-making (Varela et al. Reference Varela, Thompson and Rosch1991). Signals, especially in musical communication, may mutually enactivate or bring forth meaning rather than simply transfer information.

12. Afterword

Interwoven here are the small and large frames: the study (toporhythm/score) and the paradigm (chronotechnics). Yet the author’s art (for better or worse) is such that both the musicological and philosophical poles tend to suffer detachment due to the pull of speculative play. Regarding the study: the toporhythmic phenomenon and the challenge it presents to notational practice is just beginning and surely worthy of deeper study, but for this paper, it is merely the footprint in the chronotopical background radiation. Time itself leaves no footprint, so the temporally embedded signal/event (rhythm) was only used as a probe to distinguish that there had indeed been a verifiable temporal displacement and that we could begin to organise it. Regarding the paradigm: in the introductory references to Caceres and Renaud, the author supports their observation that there is an overdue lack of a robust theory for network music practice – while I have found that Wolfgang Ernst’s work can be extended. When theoretical frameworks are lacking, scholarly speculation is a tactic to provoke action. Thus, the author makes this provisional stance by insisting on the priority of chronality: polychrony in the trans-local, monochrony in the remediated local. It’s simply a matter of elegance: once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

Acknowledgements

The Digital Score project (DigiScore) is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant agreement No. ERC-2020-COG–101002086).