In 1744 Johan Daniel Berlin published the first music textbook in the Danish language: Musicaliske Elementer, eller Anleedning til Forstand paa De første Ting udi Musiquen (Musical Elements, or A Guide to Understanding the First Things about Music).Footnote 1 The book provides an introduction to elementary music theory and to how different musical instruments are played. At the time, Berlin was a stadsmusikant (privileged town musician) in Trondheim and one of the foremost official musical authorities in Norway, which was then part of the double kingdom of Denmark–Norway. As Berlin was Prussian-born and kept in close contact with the latest advances in the field, his work provides valuable insight into the transfer of music theory from continental Europe to Norway in the middle of the eighteenth century.Footnote 2

While several surveys of Norwegian music history mention Musicaliske Elementer as a significant publication,Footnote 3 there remain gaps in research on this central source. In a 1987 study, Peter Andreas Kjeldsberg summarized the book’s main contents and its immediate reception.Footnote 4 In a 2008 chapter, Randi M. Selvik argued that Berlin’s presentation of music as a science aligned with a rationalist view typical of the early eighteenth century.Footnote 5 Furthermore, Berlin’s comments on ornamentation have been a central source for studies of eighteenth-century performance practice in Norway.Footnote 6 The book is also mentioned in several studies of music in eighteenth-century Norway in general, and of its author in particular, but a broader study of its significance in the country’s history of music theory – including broader discussions of its specifically music-theoretical contents and context – is lacking. Indeed, the recent surge of research on Scandinavian histories of music theory has focused on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, giving little attention to earlier periods.Footnote 7 This article aims to fill this gap in the literature by asking the following questions:

1. What is the music-theoretical content of Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer?

2. How does this content relate to contemporaneous continental European music theory?

3. To what extent do later Norwegian and Danish theory sources build on Berlin’s work?

In this article, I broadly understand music theory as a field covering a number of disciplines spanning from the most elementary knowledge of musical notation (sometimes called ‘rudiments’) to compehensive theories of how different musical parameters work. In line with the pedagogical contents of Berlin’s book, I will focus on elementary music theory, which in some contexts is regarded not as music theory at all, but rather as a prerequisite that makes music-theoretical discourse possible.Footnote 8 Precisely because it is considered so fundamental, investigating its history is important. The questions posed above concern the transfer of music-theoretical knowledge between different parts of Europe in the eighteenth century, in this case from the centre of continental Europe to the Scandinavian periphery of Trondheim (and also Denmark–Norway as a whole). The case of Berlin is particularly interesting because he kept himself up to date with the latest German-language publications in music theory to an impressive extent. The primary sources in this study are Berlin’s textbook, the inventory of his library and other known eighteenth-century Norwegian theoretical sources. Because the union of Denmark–Norway lasted until 1814, I will also consider theory books published in Denmark.

This article relies on the theoretical-methodological framework of ‘intercultural transfer’ to address its central questions. The concept of intercultural transfer (Kulturtransfer) was first developed in the mid-1980s by Germanists and cultural historians Michel Espagne and Michael Werner.Footnote 9 More recently, it has been adopted by (primarily Germanophone) musicologists. In the extensive article on ‘Musik und Kulturtransfer’ in MGG Online, Stefan Keym provides a broad description of the framework, highlighting four aspects of the process of transfer that should be elucidated in the analysis:

1. the needs and motivations of the members of the host culture in adopting a cultural concept that initially appears foreign to them;

2. the actors, media and paths through which the concept enters a new cultural area;

3. the ‘translation’ of the concept, since a foreign concept is generally not adopted in a 1:1 correspondence; determining factors include the selection of individual elements from the source culture and their recombination with existing elements in the receiving culture; and

4. discourse on the transfer process by contemporaries and posterity.Footnote 10

The discussion below will touch on all four aspects of the intercultural transfer of music theory, albeit to different degrees, in order to address the research questions presented above. As the bulk of the article focuses on one actor and one source, my primary focus will be on the second aspect. Current research literature tells us little about music theory in Norway before Berlin’s 1744 textbook. Although we do, of course, know that different sorts of musical practices existed and can thus assume that there were oral traditions of music theory, I am aware of no historical records outlining what they would have entailed. This lacuna presents a challenge to the first step of an intercultural transfer analysis, as it makes it difficult to assess whether Berlin’s book introduced new music-theoretical knowledge to readers in Norway or simply codified an existing oral practice. None the less, adopting the cultural concept of the elementary theory textbook aimed towards amateurs, based on models from German-language literature, was itself an act of intercultural transfer which was surely motivated by the absence of any such codification of music theory for Danish–Norwegian readers.Footnote 11 The following four sections offer a sketch of the historical context, an overview of Berlin’s library, a critical survey of Musicaliske Elementer and a broader discussion of the transfer of theory.

Historical Context

Johan Daniel Berlin was a key figure in mid-eighteenth-century Norwegian musical life. Born in Memel, Prussia (now Klaipėda, Lithuania) in 1714, Berlin lived most of his life in Trondheim, where he died in 1787. He studied music as an apprentice of Andreas Berg, the privileged town musician in Copenhagen, from 1730. In 1737 Berlin moved to Norway to become Trondheim’s royally appointed privileged town musician, a position he held until 1767. He also served as organist in several of the town’s churches, including its cathedral (Nidarosdomen) from 1741 until his death in 1787. Holding these key positions, he was an official authority on musical matters in the city and its surrounding areas. In addition to being a significant composer and musician, Berlin was a scientist, architect, inventor, the city’s fire chief and member of Det Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskab (The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters).Footnote 12

There were four categories of public music professionals in eighteenth-century Denmark–Norway: privileged town musicians, military musicians, organists and singing teachers (cantors) at schools and churches.Footnote 13 The system of privileged town musicians had become institutionalized in the seventeenth century.Footnote 14 Similar systems had long been in place elsewhere, for instance in German states (with posts that had names such as Stadtpfeifer, Stadtmusikus or Stadtmusikant). However, Jens Henrik Koudal argues

that the stadsmusikant institution in Denmark may well have taken its basic impulses from Germany, but nevertheless developed clear independent features in the period 1660–1800, because it had to meet the needs of both the Absolute Monarchy and the towns. No formal guild-like structure for the occupation ever arose. On the other hand – and this is what was special about it – it was regulated by Royal privileges which linked town and countryside: the absolute monarchy confirmed the rights of the stadsmusikanter in the towns and gave them a monopoly of all paid music performance in the country. It was a consistent, absolutist system of privilege.Footnote 15

At the turn of the eighteenth century, there were six privileged town musician offices in Norway, a number that increased to and then stabilized at ten offices over the course of the century.Footnote 16 Several of the offices, including the one in Trondheim (which had been established in the seventeenth century and was the northernmost), also covered large areas outside the city. In practice, the offices covered most of southern Norway. Within their designated area, the town musicians could grant local musicians the right to perform for payment under their privilege, for instance in traditional ceremonies such as weddings. There are several examples of town musicians suing local musicians for performing without permission, including in Trondheim during Berlin’s time.Footnote 17 The royal privilege was removed in 1800 and the town-musician system gradually dissolved towards the middle of the nineteenth century. Berlin thus became Trondheim’s privileged town musician at the peak of the system’s operation in Denmark–Norway and is generally considered to have been the most important town musician in Norwegian history.Footnote 18

The royally appointed privileged town musicians played a significant part in processes of intercultural transfer through their monopoly on regulating paid musical performance in their regions. In 1952 Asbjørn Hernes argued that these figures were central in bringing certain types of folk tunes, and even the fiddle itself, to Norway.Footnote 19 Hernes has been criticized for his strong focus on the privileged town musicians and consequent downplaying of other ways in which musical culture could have moved to Norway, such as through military musicians and the travels of the educated upper class, as well as for the absence of musical examples supporting his claims.Footnote 20 Nonetheless, Hans Olav Gorset has found evidence that supports Hernes’s overall argument of significant continental European influences on Norwegian folk music during the eighteenth century, some of which can be associated with the town musicians.Footnote 21

The great increase in literacy among the common people in eighteenth-century Norway was certainly one major motivation for producing texts on music in the Danish language.Footnote 22 For example, the first compulsory elementary education in Norway (almueskolen) was established in 1739, teaching children to read and write Danish. This growing literacy may have contributed to a demand for Danish-language literature for amateurs wishing to learn elementary music theory in Norway. That the musical Liebhaber was Berlin’s intended readership is further indicated by the appeal to ‘lovers of . . . the nature of music’ (‘Elskere af . . . det Musicaliske Væsen’) in the book’s lengthy title (as quoted in full and discussed below).Footnote 23

Berlin’s status as a prominent musician, composer and theorist is demonstrated by his inclusion in several historical music encyclopaedias, all of which emphasize his theoretical work. Several of these encyclopaedias even mention translations of Musicaliske Elementer, implying an international dissemination of the work. However, as noted in earlier scholarship on Berlin by Karl Dahlback and Kari Michelsen, the existence of these translations has not been confirmed.Footnote 24 While Gustav Schilling mentions a Swedish translation,Footnote 25 the entry on Berlin in a central Swedish nineteenth-century music encyclopaedia does not mention any publications in that language.Footnote 26 A German translation is mentioned in several sources throughout the nineteenth century, though Dahlback (in 1951) and Michelsen (1971) only consider Schilling and François-Joseph Fétis. In 1790, Ernst Ludwig Gerber does not mention the original Danish title, but calls Berlin’s 1744 publication Anfangsgründe der Musik zum Gebrauch der Anfänger (Fundamentals of Music for the Use of Beginners).Footnote 27 This German title is repeated by Schilling in 1835, who claims that it is a German translation of Musicaliske Elementer, but wrongly dates the Danish original to 1742.Footnote 28 In 1866, Fétis repeats this claim, including the wrong dating of the original publication.Footnote 29 Like Gerber in 1790, Eduard Bernsdorf’s 1856 encyclopaedia mentions only the German title.Footnote 30 In Norway, a German translation is mentioned by Johan Gottfried Conradi in 1878.Footnote 31 Searches in online databases such as WorldCat and the catalogues of different national libraries have uncovered no new clues indicating the existence of any translations. In short, much indicates that this was a game of music-historical ‘telephone’, perhaps caused by Gerber’s use of the freely translated German title in 1790.

While Musicaliske Elementer was Berlin’s most significant music-theoretical publication, it was not his only one. In addition to several published writings on non-musical topics, he produced another on music theory: ‘Anledning til Tonemetrien’ (A Guide to Tonometry). This lengthy article was first published in Det Trondhiemske Selskab’s publication series in 1765.Footnote 32 Two years later, the 1765 volume of the series, including Berlin’s article, was published in German translation.Footnote 33 The German version of Berlin’s text was also published separately the same year.Footnote 34 Engaging with central discussions in the contemporaneous German literature, the text discusses tuning theory and logarithmic calculations for equal temperament – in Berlin’s case not only twelve-tone, but also twenty-four- and thirty-six-tone equal temperament. It further describes the construction of a tuning instrument he had invented, the ‘Monochordon Unicum’, which was built in 1752 and is today on display at Ringve Musikkmuseum in Trondheim. As argued by Ola Kai Ledang, Berlin’s work on tuning theory shows great insight into contemporary music-theoretical discussions but was neither particularly original nor influential in a European context.Footnote 35 Berlin’s most important contribution as an author on musical subjects was instead the pedagogical dissemination of elementary music-theoretical knowledge in Danish.

Berlin’s Library

In examining the case of Johan Daniel Berlin from the perspective of the intercultural transfer of music theory, it is worth noting that he came from Prussia, was educated in Copenhagen and appears to have kept in close touch with contemporary German music theory. This last aspect is evidenced by the inventory of his possessions that were put up for auction after his death on 4 November 1787.Footnote 36 In addition to many mathematical and musical instruments, there is an impressive list of books on a range of scientific subjects, including astronomy, mathematics, meteorology, philosophy, religion, medicine, chemistry, city planning, law, electricity, history and architecture. The largest group, however, consisted of books on music. The book section of the inventory ends by listing fifteen ‘bundles’ (Bundter) of unspecified books, indicating that the book collection was significantly larger than the 379 specified items.Footnote 37 In her thesis on Berlin, Kari Michelsen identified eight music books in Det Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskab’s collection that once belonged to Berlin but were not listed in the auction inventory.Footnote 38

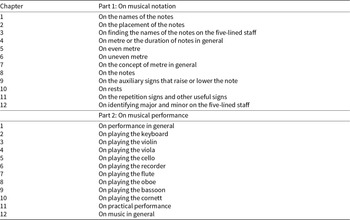

Table 1 provides details of Berlin’s library of music books as reconstructed from the auction inventory, Michelsen’s thesis and bibliographic data from NTNU Universitetsbiblioteket’s digital catalogue and WorldCat. The Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet library in Trondheim houses the library of Det Kongelige Norske Videnskabers Selskab (Gunnerusbiblioteket), which acquired many, but not all, of Berlin’s books.Footnote 39 The auction inventory, which lists authors’ names, shortened titles and (for some entries) years of publication, is the primary source. However, several of the entries in the inventory are incomplete, making it unclear exactly which book they refer to and necessitating cross-checking with the other sources to fill the gaps.

Table 1. Reconstruction of the catalogue of Johan Daniel Berlin’s library of music books

a . For instances where it is uncertain which edition Berlin owned, the year of publication of the first edition is followed by a question mark; dates in square brackets indicate the year Berlin acquired the book, if known; hymnals and other song books have not been included; and volumes of multi-volume works have been combined into one entry.

b . Bound together with Marpurg’s 1757 Anfangsgründe der theoretischen Musik.

c . The auction inventory (which does not list any author) lists the title ‘Aller Musicalischen alten und neuen Instrumenten, in fünff Theilen’. Based on this description, I find it most likely that it refers to volume 2 part 1 of Praetorius’s Syntagma musicum. We know that Berlin had access to the Syntagma musicum, since he cited it in a 1752 newspaper article; see Kari Michelsen, ‘Johan Daniel Berlin (1714–1787)’ (Cand. philol. thesis, Universitetet i Trondheim, 1971), 136.

Almost all of the principal German-language theory sources available at the middle of the eighteenth century were found on the shelves of Berlin’s personal library in Trondheim. He owned books by C. P. E. Bach, Johann Joseph Fux, Johann David Heinichen, David Kellner, Joseph Friedrich Majer, Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, Johann Mattheson, Christoph Nichelmann, Freidrich Erhardt Niedt, Friedrich Wilhelm Riedt, Joseph Riepel, Johann Adolph Scheibe, Georg Andreas Sorge and Johann Gottfried Walther. Marpurg and Mattheson are represented by seven works each, Sorge by four and Scheibe three. Jean-Philippe Rameau is represented only through his German reception, in particular Marpurg’s translation of Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s summary.Footnote 40 The diverse topics covered span from introductions to elementary theory and figured bass to technical discussions of tuning theory and temperament. Hernes noted that inscriptions in Berlin’s copy of Mattheson’s Critica Musica claim that it was a gift from Mattheson in 1739, indicating that they met or were at least in contact.Footnote 41 Given Berlin’s fascination with Mattheson’s writings, it is surprising that the latter’s pamphlet of 1740 Etwas Neues unter der Sonnen! oder Das unterirdische Klippen-Concert in Norwegen (Something New under the Sun! or The Underground Mountain Concert in Norway) – a short text that contains the first printed transcription of Norwegian folk musicFootnote 42 – is not listed in the auction inventory. Of course, given the incompleteness of the list, indicated by the fifteen bundles of unspecified (and presumably shorter) books, its absence from the auction inventory does not preclude the possibility that Berlin owned it.

As the years of publication make clear, Berlin continued to acquire music-theory books from the continent long after he had settled in Trondheim in 1737. Most of them are from the 1730s, 1740s and 1750s. Only one book published after 1760 appears in the inventory, suggesting that at some point he stopped expanding his collection. For example, Johann Philipp Kirnberger is represented only by his early publication Der allezeit fertige Polonoisen- und Menuettencomponist (1757) – an introduction to composing minuets and polonaises using dice. His main theoretical works, including Die Kunst des reinen Satzes in der Musik (The Art of Pure Composition in Music, 1771–1779), only appeared in the 1770s and did not make it into Berlin’s comprehensive library. For most of the books, we do not know when Berlin acquired them, making it difficult to know exactly which texts were available to him when he wrote Musicaliske Elementer, apart from the obvious fact that books published after 1744 can be ruled out.

It is also somewhat unclear how Berlin acquired these works. The limited organized music trade in eighteenth-century Norway made it necessary to travel or use contacts abroad in order to source such items. We do not know how much Berlin himself travelled after moving to Trondheim, but he certainly had a broad professional network. Michelsen’s study of the music trade in Norway suggests that sheet music and music literature came to Trondheim mainly by ship, which because of the ice would have been significantly restricted during winter.Footnote 43 Copenhagen was the most important point of contact between Norway and continental Europe at this time, and catalogues of new books and sheet music sold in Copenhagen provide insight into the availability of music literature.Footnote 44 Michelsen has listed the sheet music and music literature included in five such catalogues – from 1759, 1768, 1786, 1795 and 1799 – drawn from the collection of the Norwegian book collector Christopher Hammer (1720–1808).Footnote 45 The catalogues indicate how book collectors and sellers in Norway could get information on new books available abroad. They show that several music-theory books were available from vendors in Copenhagen shortly after their release. They include a handful of theory books, all in German. The catalogues from 1759 and 1768 include key works by the following authors also found in Berlin’s library: d’Alembert, Johann Wilhelm Hertel, Marpurg, Peter Franz Tosi, Kellner, Riedt and Riepel. Marpurg is the only author represented by several titles and by titles in both catalogues. Many of the authors in Berlin’s library (for instance Mattheson) are not included, perhaps because their books were no longer considered new.

Berlin’s collection of music books is exceptional for its time, with respect to both size and thematic breadth. It was not, however, the only collection in mid-eighteenth-century Norway containing theory books. For example, in her study of musical life in Bergen in the period 1780–1830, Randi M. Selvik mentions that the collection of Claus Fasting (1746–1791) contained Johann Friedrich Daube’s General-Bass in drey Acorden, Barthold Fritz’s Anweisung and Mattheson’s Exemplarische Organisten-Probe.Footnote 46 Selvik’s study also indicates that eighteenth-century theory, particularly the work of Marpurg and Kirnberger, remained relevant in Norway into the early nineteenth century; key works by several central eighteenth-century theorists appeared in the book collections of Friderich Bøschen (1771–1825) and Christian Fredrik Gottfried Bohr (1773–1832).Footnote 47 The influential Lindeman family also possessed a large library of handwritten translations of central music-theoretical texts.Footnote 48

Musicaliske Elementer (1744)

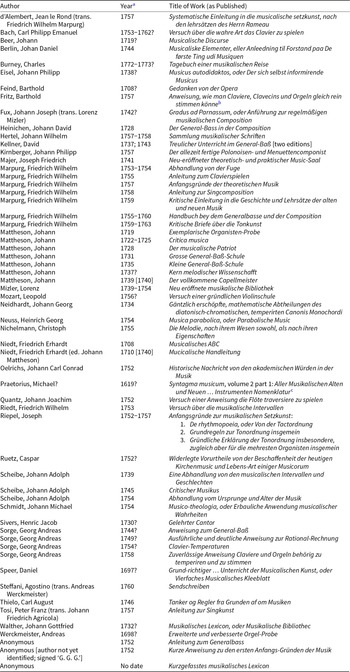

Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer (1744) was published in Trondheim at the author’s expense. The full title-page of the book (Figure 1) reads:

Musicaliske Elementer / eller / Anledning til Forstand / paa / De første Ting udi MUSIQUEN / hvor udi / Den Musicaliske Signatur / I den Bruug som den nu haves hos de fleeste, / saa ogsaa / Applicaturen paa nogle saa kaldte strygende og blæsende Instrumenter / og andet meere Musiquen tilhørende; / For dem, som ere Elskere af at lægge ret Grund til at forstaae det Musicaliske Væsen, / kort og tydeligen anført, fuldferdiget og udgivet / ved / JOHANN DANIEL BERLIN / Kongel. privilegerte Stads-Musicus og Organist til Dom-Kirken i Tronhiem. / TRONHIEM, / Trykt paa Authors Bekostning af Jens Christ. Winding, 1744.Footnote 49

Musical elements, or A guide to understanding the first things about music, including musical notation in the form in which it is now used by most people, as well as how to play some so-called string and wind instruments and other things more closely related to music; For those who are lovers of laying the right foundation for understanding the nature of music, briefly and clearly written, prepared and published by Johan Daniel Berlin, royal privileged town musician and organist of the cathedral in Trondheim. Trondheim: printed at the author’s expense by Jens Chr. Winding, 1744.

Figure 1. Johan Daniel Berlin, Musicaliske Elementer, eller Anleedning til Forstand paa De første Ting udi Musiquen (Trondheim: Winding, 1744), title-page. Nasjonalbiblioteket, Oslo, NA/A h 9721

There are at least nineteen existing copies of Musicaliske Elementer, located in the following libraries and museums: NTNU Universitetsbiblioteket, Trondheim (four copies); Nasjonalbiblioteket, Oslo (three); Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Stockholm (three); Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Copenhagen (three); Det Kgl. Bibliotek, Aarhus (one); Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen (one); Musikmuseet, Copenhagen (one), Anno Glomdalsmuseet, Elverum (one); Norrköpings Stadsbibliotek (one); and Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome (one).Footnote 50 Five of the existing original copies include handwritten collections of keyboard pieces, some of which were composed by Berlin, as an appendix.Footnote 51 The length and contents of the added manuscript pages, which are bound together with the printed text and mostly in Berlin’s hand, differ among these five copies. Two of them additionally include a short introduction to figured bass. The following will focus on the printed text, which also appeared in a modern edition in 1977.Footnote 52

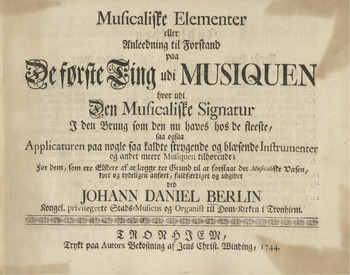

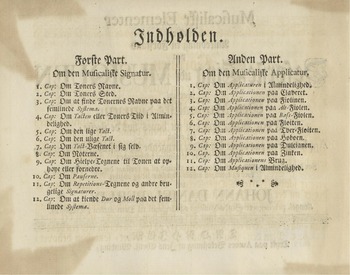

The book spans 139 pages in quarto format and is divided into two parts of almost equal length. Both parts contain twelve chapters, as listed in the book’s table of contents (Figure 2, translated in Table 2). Additionally, the book contains a six-page preface, signed by Berlin on 1 January 1744 in Trondheim.Footnote 53 As the table of contents makes clear, Part 1 focuses on musical notation (Signatur) and Part 2 on how to play different musical instruments (Applicatur).Footnote 54 The aspects covered in Part 1 are the fundamentals of musical literacy in contemporaneous Western Europe, including note names, different types of metre (‘even metres’ being duple and quadruple metres and ‘uneven’ triple), ornaments and the difference between major and minor. The instruments presented in Part 2 are the keyboard (‘Claveret’), violin (‘Fiolinen’), viola (‘Alt-Fiolen’), cello (‘Bass-Fiolen’), recorder (‘Fløiten’), flute (‘Tver-Fløiten’), oboe (‘Hoboen’), bassoon (‘Dulcianen’)Footnote 55 and the cornett (‘Zinken’).Footnote 56 Certain other instruments – such as trumpets (‘Trompetter’), trombones (‘Bassuner’) and French horns (‘Valthorner’) – are mentioned in passing.Footnote 57

Figure 2. Berlin, Musicaliske Elementer, table of contents

Table 2. Translation of the table of contents for Johan Daniel Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer, eller Anleedning til Forstand paa De første Ting udi Musiquen

Berlin’s equal focus on notation and how to play various instruments is grounded in his view that ‘a complete musician’ (‘een fuldkommen Musicus’) is one that masters ‘the whole science’ (‘den heele Videnskab’) of music.Footnote 58 This is discussed in the final, more philosophical chapter of the book. He follows up by comparing a person who only knows how to play but does not know any theory, and thus plays ‘wildly’ (‘vildt’),Footnote 59 to ‘an unintelligent animal’ (‘eet u-forstandig Dyr’).Footnote 60 He calls a listener who enjoys such music a ‘wild barbarian’ (‘vild Barbar’).Footnote 61 A person who knows theory but not how to perform, on the other hand, knows only the connections between the figures on the page, but not what they really mean beyond that. Based on this, Berlin argues that the composer – who must necessarily know the nature of notation, technical performance and sounding music – is ‘the greatest musician’ (‘den største Musicus’).Footnote 62

The content of Berlin’s book does not differ significantly from what can be found in contemporaneous theory books from the continent. Berlin does not acknowledge in the book which sources he used. Nevertheless, Peter Andreas Kjeldsberg and Hans Olav Gorset have argued that Majer’s popular 1732 Museum musicum might have served as a rough model for Berlin’s book.Footnote 63 Majer’s 1741 Neu-eröffneter theoretisch- und praktischer Music-Saal, which we know formed part of Berlin’s library, is the second (revised and expanded) edition of his influential Museum musicum. I will use that edition for my comparison. It is of comparable length to Berlin’s book and is similarly presented in two parts: following a preface, the first part treats musica theoretica (focusing on musica signatoria) and the second musica practica (focusing on musica exsecutoria). Further, several of the fingering charts in the second part bear a striking visual similarity to the ones in Berlin’s book, without being exactly the same. The initial sentences of the books are also strikingly similar. Berlin writes, ‘That music is as much a gift from God as all other sciences is not to be contradicted’ (‘At Musiquen ligesaavel er een Guds Gave, som alle andre Videnskaber, er ikke at modsige’).Footnote 64 The opening sentence of Majer’s text reads, ‘Noble music, like all other sciences, originally comes from God’ (‘Die edle Musica kommt, gleich alle andere Wissenschafften, ursprünglich von GOTT her’).Footnote 65 Berlin’s book is, however, not a mere adaptation of Majer’s. There are differences in contents and structure. Majer’s first part is briefer than Berlin’s, while Majer’s longer second part covers vocal music and many instruments not discussed in detail in Berlin’s book (flageolet, clarinet, trombone, French horn, trumpet, lute, harp, guitar, timpani, viola da gamba and viola d’amore). Majer also includes an appendix with definitions of musical terms.

Introductions to elementary music theory and how to play a range of musical instruments formed a popular genre at the time. In addition to the work of Majer, Berlin owned similar books by Daniel Speer and Johann Philipp Eisel (see Table 1). Another similar brief introduction to elementary theory in Berlin’s library, albeit without the survey of different instruments, is Niedt’s Musicalisches ABC (1708).Footnote 66 Although we cannot be certain, because we do not know when Berlin acquired most of these books, it is likely that he consulted all of them when preparing his Musicaliske Elementer.

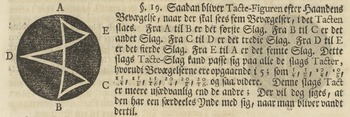

In some respects, Berlin deviated from commonly held views among contemporary German theorists. One example is from the introduction to metre, in which he illustrates how to beat different types of metres with comments on each individual hand movement. He writes of quintuple metre (Figure 3) that ‘this kind of metre is more unusual than the others; however, it will be said that it has a special grace when one becomes accustomed to it’ (‘Denne slags Tact er meere usædvanlig end de andre; Der vil dog siges, at den har een særdeeles Ynde med sig, naar man blived vandt dertil’).Footnote 67 This was a very unusual view. Based on a recent study of a range of eighteenth-century German theoretical sources, Paul Newton-Jackson asserts that ‘quintuple and septuple metres are almost universally rejected as unnatural, obsolete and unpleasant’.Footnote 68 Similarly, Roger Mathew Grant observes that

trials and critiques of quintuples and septuples gradually emerged at the close of the eighteenth century when theorists began to include these meters in their exhaustive lists of every possible signature. During this time composers attempted movements and small pieces in these meters while theorists explained their existence in order to condemn or dismiss it.Footnote 69

Figure 3. Quintuple metre in Berlin, Musicaliske Elementer, 14

Grant cites Riepel, Marpurg, Kirnberger and Augustus Frederic Christopher Kollmann as examples of such dismissals, while Newton-Jackson cites Walther, Marpurg and Johann Georg Sulzer.Footnote 70 Most theory books of the eighteenth century, however, do not mention the metres at all. They were, after all, only very rarely used in composed music.Footnote 71 While quintuple metre was included by Berlin, septuple metre was simply not mentioned in his otherwise exhaustive list of theoretically possible metres. It is also worth noting that while Berlin speaks in detail about metre, and includes the concept of tempo, he introduces no concept of rhythm in his book, speaking only of the different notes’ ‘length of time’ (‘Tiids Længde’).Footnote 72

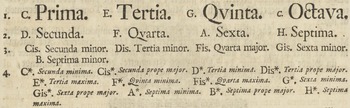

In the book, Berlin follows an archaic note-naming practice. With the sole exception of B♭/A♯, which are named B (as opposed to H, which refers to B♮), Berlin consistently uses the ‘sharp’ note names. For example, the pitch between D and E is always called Dis in the text, even if it is notated as E♭ in the music (Figure 4).Footnote 73 This was a common practice in the early eighteenth-century German literature, including the textbooks by Majer, Eisel and Niedt that may have served as models for Berlin.Footnote 74 However, it was quickly falling out of fashion, and by the middle of the century the modern German practice (E♭=Es) became the norm. Josef Riepel was, for one, very critical of the older way of naming notes, which he in 1755 described as outdated.Footnote 75

Figure 4. Example of note-naming in Berlin, Musicaliske Elementer, 41

A particularly interesting aspect with regard to the naming of notes is how Berlin conceptualizes relations between pitches. Throughout the book, when writing about pitch relationships, he draws on two different conceptual metaphors: tones are not only described as higher/deeper (høyere/dybere), common in the continental literature, but also as finer/coarser (finere/grovere) – the former conceptualizing pitches in spatial terms, the latter as textures.Footnote 76 In George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s terminology, Berlin thus uses both an orientational and an ontological metaphor.Footnote 77 He appears to use these metaphors interchangeably, often using both simultaneously, for instance writing about ‘the coarser and deeper tones’ (‘de grovere og dybere Toner’) and ‘a higher or finer tone’ (‘en høyere eller finere Tone’).Footnote 78 Elsewhere, however, he uses the ontological metaphor alone, simply writing ‘the coarse g’ (‘det grove g’) and ‘the coarsest octave’ (‘den groveste Octav’).Footnote 79 That there are many different cultural and historical practices of conceptualizing relationships between pitches is well known,Footnote 80 but to my knowledge the use of the fine/coarse metaphor in this manner has not been discussed before. While further research is needed, it is possible that this conceptual metaphor was part of an oral music-theoretical discourse in Norway, into which Berlin was ‘translating’ continental theory.Footnote 81

The subtitle of Berlin’s book highlights that the text is an introduction to ‘the first things in music’ (‘De første Ting udi Musiquen’). In the final chapter, he clarifies that ‘the first things in music are a sound in its own right. The last thing in music is the dissolution or development of a sound in all its diversity’ (‘De første Ting i Musiquen er een Lyd i sit eget Væsen. Den sidste Ting i Musiquen er een Lyds Opløsning eller Udvikling i sin Mangfoldighed’).Footnote 82 The image of music starting with a note and ending with a ‘diversity’ of sound is also the foundation of Berlin’s presentation of chords, scales and keys. In the chapter on major and minor, he opens by claiming that a chord is a collection of four notes – the first, third, fifth and eighth notes of the scale.Footnote 83 He soon turns this relationship on its head, however, claiming that ‘one experiences in music that the musical chord lies hidden, as it were, in every sounding thing’ (‘Man erfarer dette i Musiquen, at der ligesom ligger skiult i eenhver lydelig Ting den Musicaliske Accord’).Footnote 84 Without it being stated explicitly, we sense an implicit reference to the harmonic series. Since the first and fourth notes of the chord are the same, he explains that the chord is often called trias harmonica, tying his explanation to Johannes Lippius’s original term for the concept of a triad.Footnote 85 Joel Lester demonstrates that the concept had several names in the early eighteenth century:

the harmonic triad (trias harmonica in Niedt 1700), the perfect chord (l’accord parfait in Couperin), the common chord (comon corde in Blow c. 1670?, concentus ordinarius in Muffat 1699, Ordinar-Satz or Ordinar-Griff in Werckmeister 1702, ordinair Accord in Heinichen 1728), and, with Mattheson’s characteristic bombast, the ‘perfect, fully consonant, harmonic triad or chord’ (1735).Footnote 86

Berlin’s preferred term – ‘the musical chord’ (‘den Musicaliske Accord’) – is related to these continental terms without being a direct translation of any of them.

After introducing the concept of a chord, Berlin goes on to claim that the major scale was historically generated by filling out the gaps with grace notes to the original chordal notes C, E, G and C.Footnote 87 Implicitly, he thus presents a set of scale-degree functions. The new scale steps are called ‘shadow’ notes in relation to the ‘original’ notes: ![]() $\hat{2}$ is a grace note to

$\hat{2}$ is a grace note to ![]() $\hat{1}, \hat{4}\ \text{to}\ \hat{3}, \hat{6}\ \text{to}\ \hat{5}\ \text{and}\ \hat{7}\ \text{to}\ \hat{8}$. Through exploring this scale, according to Berlin, musicians discovered the minor chord on D, which he calls the original minor chord. Without going into the generation of the minor scale, he presents it in what is usually called its ‘melodic’ version:

$\hat{1}, \hat{4}\ \text{to}\ \hat{3}, \hat{6}\ \text{to}\ \hat{5}\ \text{and}\ \hat{7}\ \text{to}\ \hat{8}$. Through exploring this scale, according to Berlin, musicians discovered the minor chord on D, which he calls the original minor chord. Without going into the generation of the minor scale, he presents it in what is usually called its ‘melodic’ version:

Den diatoniske Dur Scala er i alle Tilfelde baade opstigende og nedstigende, som C D E F G A H c. Den diatoniske Moll Scala ansees opstigende saaledes: D E F G A H cis d, og nedstigende saaledes: d, c, B, A, G, F, E, D.Footnote 88

The diatonic major scale is in all cases, both ascending and descending, C D E F G A B c. The diatonic minor scale is considered ascending as follows: D E F G A B c♯ d, and descending as follows: d c B♭ A G F E D.

He further explains that the scales can be transposed, yielding twelve of each type. He does not mention ‘harmonic’ minor, nor any modal theory.Footnote 89

The story of how the scale is generated from a single tone to a chord and, finally, to the diatonic scale is repeated on the very last pages of the book. Here, however, Berlin goes further, foreshadowing his later mathematical work on tuning theory and equal temperament. He claims that there are four ‘diatonic’ scales generated from a single tone:

1. The tone generates the (major) chord, with the third, fifth and octave (the first diatonic scale).

2. The grace notes mentioned fill out the space between each chordal note, generating what is usually called the diatonic scale (the second diatonic scale).

3. By replicating this second scale on each of its own steps one gets five further notes, generating what is usually called the chromatic scale (the third diatonic scale).

4. Because the notes in this (chromatic scale) can also be raised or lowered in musical practice, there are twelve more notes in between the twelve existing ones, resulting in a twenty-five-note scale including the octave (the fourth diatonic scale).Footnote 90

Berlin visualizes the generation of this ‘perfect’ (‘fuldkomne’) diatonic scale in a figure with four levels (Figure 5). He does not go into the use (or notation) of the fourth scale, which he claims is elsewhere called the ‘enharmonic’ (‘enharmoniske’) scale,Footnote 91 seemingly including it primarily to acknowledge the existence of notes beyond the twelve chromatic ones. The other parts of the book recognize twelve notes only. Berlin acknowledges that it is the second scale that is usually called diatonic and does not explain why the other three scales should also have this name.

Figure 5. Figure illustrating the four scales in Berlin, Musicaliske Elementer, 129

Transfer of Theory

Berlin’s textbook and its relations to contemporaneous literature offer important glimpses into the transfer of music theory from continental Europe to Norway. However, it is only one piece of the puzzle. First, the type of elementary music theory presented in Musicaliske Elementer was primarily taught orally (if not tacitly). Second, there were other musical professionals besides the privileged town musicians and organists, such as military musicians and singing teachers. Third, several other works of music theory appeared in Danish shortly after Berlin’s. Finally, although the sources in this specific regional context are very scarce, there are also traces of more advanced music theory in circulation (as reflected in Berlin’s library and his work on tuning theory). These were all part of the transfer of continental European music theory to, and its dissemination within, eighteenth-century Norway. In this final section, I will attempt to relate Berlin’s book to other known Norwegian – and some Danish – theory sources of the eighteenth century to situate the book within these broader processes of transfer.

The town-musician apprenticeship system in eighteenth-century Denmark–Norway was undoubtedly an important milieu and means for the communication of music theory. As was the case with Berlin, prospective privileged town musicians spent several years as apprentices to a master town musician. Koudal argues that although the town musicians in Denmark–Norway were not a formal guild, their educational system was rather guild-like, usually involving five to eight years of apprenticeship and learning the art of playing many different instruments. Unfortunately, we have limited knowledge about the learning of music theory in this context.Footnote 92 Some scholars have assumed that the textbook by Berlin and a 1782 textbook by Lorents Nikolai Berg (1742/1743–1787), town musician in Kristiansand in southern Norway, reflected the expected level of music-theoretical knowledge for a town-musician apprentice.Footnote 93 However, because there is little to suggest that these textbooks were aimed towards town musicians,Footnote 94 they cannot really say much about what such people were expected to know. Berlin’s rich library and his work on tuning theory prove that his knowledge of music theory went far beyond the introductory level of these texts. One specific topic omitted from these textbooks that we can nevertheless assume any town musician must have mastered is figured bass. This was essential knowledge for any educated musician in eighteenth-century Europe, something also reflected in the several figured-bass manuals in Berlin’s library. As mentioned, Berlin was very explicit about the need for a ‘real’ musician – as opposed to a ‘cheater’ (‘Fusker’) – to understand both the theoretical and practical aspects of music properly.Footnote 95 If we assume that this idea of what constitutes a real musician was widespread, theory must have played an important part in music education of the time.

We do not know how many copies of Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer were printed, but traces of its contemporary reception indicate that it was an important book in Denmark–Norway in the second half of the eighteenth century. Following its appearance, several similar Danish-language introductions to music appeared, by Carl August Thielo in 1746,Footnote 96 Fredrik Christian Breitendich in 1766 (two books),Footnote 97 Niels Hansen in 1777Footnote 98 and the aforementioned textbook by Berg in 1782.Footnote 99 Hansen and Berg’s textbooks explicitly cite and recommend Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer.Footnote 100 Hans Magne Græsvold finds it likely that Berg used Berlin’s book as a model for his own textbook, which was the second to be published in Norway.Footnote 101

Much of the contents with regard to musical-notation practices and terminology overlap between the later Danish-language books, even though they have different focus points. Berg’s book is the closest in content to Berlin’s, giving general instructions on how to play a range of different instruments and an introduction to reading musical notation. Thielo focuses on the keyboard and singing, while Hansen is dedicated completely to singing.Footnote 102 Breitendich has one volume on singing and one volume on figured bass. While all authors present the concept of metre, Berlin’s book is the only one that includes complex time signatures. In line with common practice, the other music-theory textbooks published in eighteenth-century Denmark–Norway simply do not mention the existence of metres beyond simple and compound. This aspect of Berlin’s book was thus not taken up by the later authors, which remained more in line with the continental practice of disregarding complex metres. Similar to Berlin, however, Thielo, Breitendich and Berg all discuss rhythm in terms of the ‘time’ (Tid) of the notes. The term ‘rhythm’ (Rhytmus), from prosody, is included only in Hansen.Footnote 103

Breitendich’s 1766 volume on figured bass does not explicitly introduce or discuss the concept of the rule of the octave but exemplifies the different keys through scales harmonized using this principle.Footnote 104 This tells us something vital about the teaching and understanding of the concept of a key in eighteenth-century Denmark–Norway. It presents the implicit tonal theory of the rule of the octave by ascribing specific chord structures to particular scale degrees in the bass.Footnote 105 A key feature of the rule of the octave is that some scale steps are more stable than others, which are more active. ![]() $\hat{1}$ and

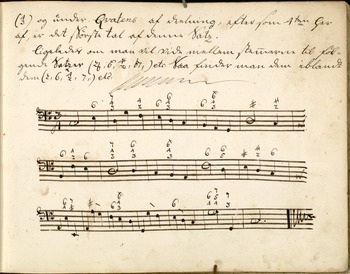

$\hat{1}$ and ![]() $\hat{5}$ are the most stable and the only steps that take root-position triads. The remaining steps take different types of sixth chords and (inversions of) seventh chords. This aligns well with the view of the scale, separating it into ‘original’ and ‘shadow’ notes, presented in Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer. Berlin does not cover figured bass in the book, but the Trondheim and Norrköping copies of his work contain a manuscript appendix with a short introduction (five and six pages, respectively) to figured bass that appears (in both cases) to be in Berlin’s hand.Footnote 106 The text is restricted to presenting what each figure means, in order to enable the reader to realize simple figured basses. However, the appendix in Trondheim ends with an example of a bass (Figure 6) that consists of several scale-based passages in different keys, clearly utilizing the rule of the octave.

$\hat{5}$ are the most stable and the only steps that take root-position triads. The remaining steps take different types of sixth chords and (inversions of) seventh chords. This aligns well with the view of the scale, separating it into ‘original’ and ‘shadow’ notes, presented in Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer. Berlin does not cover figured bass in the book, but the Trondheim and Norrköping copies of his work contain a manuscript appendix with a short introduction (five and six pages, respectively) to figured bass that appears (in both cases) to be in Berlin’s hand.Footnote 106 The text is restricted to presenting what each figure means, in order to enable the reader to realize simple figured basses. However, the appendix in Trondheim ends with an example of a bass (Figure 6) that consists of several scale-based passages in different keys, clearly utilizing the rule of the octave.

Figure 6. Demonstration of figured bass in a handwritten appendix to a copy of Berlin’s Musicaliske Elementer. NTNU Universitetsbiblioteket, Trondheim, Gunnerus XM; Oct. 8. CC BY-SA 4.0

Certain aspects presented in Berlin’s textbook – which might have already been oral practice – were cemented in the later literature. One practice the work seems to have helped preserve is the old system of note-naming discussed above. While, as we have seen, naming notes using only sharp note names had fallen out of fashion in the German literature by the middle of the eighteenth century, it remained common in Norway throughout the century. In Denmark, the practice was followed in the textbooks by Thielo and Breitendich.Footnote 107 Breitendich acknowledged that this was becoming outdated, but nevertheless retained it in his books.Footnote 108 The first Danish-language textbook consistently to incorporate the practice of naming the flattened notes Ces, Des, Es, Fes, Ges, As and B is Hansen’s from 1777.Footnote 109 In Norway, however, Berg retained the old system as late as 1782.Footnote 110 Unlike the Danish authors, all of whom clearly preferred the spatial terminology, he calls high and low tones ‘coarse and fine tones’ (‘grove og fine Toner’), similarly to Berlin.Footnote 111 Berg is also alone among these writers in using Berlin’s preferred term for the triad – ‘musical chord’ (Musicalisk Accord).Footnote 112

Traces of eighteenth-century Norwegian music-theoretical practice can also be found in unpublished manuscripts. In addition to Berlin’s appendix on figured bass, these include an undated manuscript written by Hans Henrik Bøcher (1712–1777),Footnote 113 probably from 1768 or 1769,Footnote 114 and an undated manuscript that belonged to Karen Angell (1732–1788).Footnote 115 The Bøcher manuscript forms part of a parish register from Risør and is entitled ‘De Musicalske Grund Regler’ (The Musical Ground Rules). The Angell manuscript is entitled ‘Musicalisk Tidsfordriv’ (Musical Passage of Time) and is a music book with a theoretical introduction named ‘Den Musicaliske Signatur’ (Musical Notation). Both manuscripts use the old note-naming practice, with its preference for sharp note names. Unlike the theory books printed in Norway by Berlin and Berg, they include solmization, indicating that this was a part of oral music-theoretical practice in the country.Footnote 116 Bøcher also includes some modal theory, and, like Berlin and Berg, he uses the fine/coarse metaphor when talking about pitch range. This terminology thus appears to have been common in Norway. Hampus Huldt-Nystrøm has discussed the contents of the Bøcher manuscript in detail, concluding that the most interesting aspect of it is how archaic the terminology was for its time.Footnote 117

Although the references to Berlin in the textbooks by Hansen and Berg demonstrate that his work had an impact in both Kristiansand and Copenhagen, Berlin’s influence was no doubt strongest in Trondheim and the surrounding areas, where he and his family in practice had a monopoly on decisions related to music and music making from the 1740s until the turn of the nineteenth century. The Berlins could justifiably be called Norway’s first musical dynasty. Around 1770, Berlin and his sons Johan Andreas (1734–1772) and Johan Henrich (1741–1807) simultaneously held all three major organist posts in Trondheim.Footnote 118 Besides the Berlins, another significant musical family in that city was the Tellefsens. One of the existing copies of Musicaliske Elementer belonged to Johan Christian Tellefsen (1774–1857) and contained, in addition to the printed text and manuscript music by Berlin, a manuscript section with chorales and other small pieces in Tellefsen’s hand.Footnote 119

Within the Berlin family’s milieu was also the organist Ole Andreas Lindeman (1769–1857), who would start a particularly influential musical family consisting of several generations of professional musicians and music teachers. He was the father of the famous organist, composer and folk song collector Ludvig Mathias Lindeman (1812–1887). A connection between the families can be seen in that the most renowned of Johan Daniel Berlin’s sons, composer and organist Johan Henrich Berlin, became Ole Andreas Lindeman’s first music teacher in the 1780s. Lindeman shared Johan Daniel Berlin’s interest in continental music theory. As already mentioned, the Lindeman family owned a substantial number of handwritten translations of music-theory books stemming from Ole Andreas Lindeman. Of the sixty-three titles, twelve overlap with those found in Berlin’s library.Footnote 120 Some of these are copies of the same work, reducing the number to eight: C. P. E. Bach, Fux, two by Marpurg (Abhandlung von der Fuge and Handbuch bey dem Generalbasse und der Composition), Leopold Mozart, Tosi, Walther and Werckmeister. Surprisingly, given Lindeman’s interest in earlier music theory, there are no works by Mattheson in his collection. Ole Andreas Lindeman had studied with the Kirnberger student Israel Gottlieb Wernicke (1755–1836), and Kirnberger is the most-represented theorist in the Lindeman collection. The collection also contains translations of key works by, for instance, Heinrich Christoph Koch, Georg Joseph Vogler and Luigi Cherubini. Unsurprisingly, Lindeman’s collection thus included slightly more recent theory than Berlin’s, showing a development in the field in Norway which was, however, still tightly connected to transfers from continental (primarily German) sources. It is also at this point, at the turn of the nineteenth century, that the formerly very strong position of the Berlin family in Norwegian life fades.

Johan Daniel Berlin and his Musicaliske Elementer played an important role in the intercultural transfer of music theory from other parts of Europe (particularly the German-speaking lands) to Norway during the eighteenth century. The above survey and comparison of relevant historical sources, in line with the aims of intercultural transfer analysis, highlights: (1) the need for such textbooks in Danish; (2) how Berlin’s central role as a privileged town musician and organist with a good overview of current German theory literature put him in an ideal position to produce one; (3) similarities and differences between Berlin’s textbook and German theoretical literature; and (4) Berlin’s work in relation to the broader construction of a Danish-language theory discourse. Among the key findings are Berlin’s role in the cementing of a note-naming practice, which included a preference for the use of sharp note names, and a conceptualization of pitch relationships as ‘coarse’ or ‘fine’ in addition to the more common spatial metaphors. More broadly, the analysis demonstrates the hegemony of German musical culture in Scandinavia at this time, including the key role played by the intercultural transfer of German-language music theory to the region.