Introduction

Many settlements flourished on the East African coast from the seventh century ce until the arrival of the first Portuguese merchants at the very end of the fifteenth century ce. These settlements were integrated into a large system of commerce and migration in the Indian Ocean World, where various goods, services and people flowed between the East African interior, the coast and other Indian Ocean ports. The material, linguistic and religious cohesion of the people on this coast is encompassed by the term Swahili, which refers to the region between southern Somalia and northern Mozambique and its inhabitants. The majority of Swahili history prior to 1500 ce is understood through archaeology and linguistics, as there are few written records from this time. Archaeological investigations and oral histories have revealed numerous Swahili coastal settlements of varying size and material complexity, the earliest dating to the sixth to seventh centuries ce (Fitton Reference Fitton2017; Fleisher & LaViolette Reference Fleisher and LaViolette2013; Juma Reference Juma2004). The most well-known Swahili sites include durable stone architecture, such as Kilwa in Tanzania, but most people would have resided in houses of wood, wattle and daub (Fleisher & LaViolette Reference Fleisher and LaViolette1999). They subsisted on fishing, agriculture, local craft production and trade, and after 1000 ce increasingly practised Islam as their main religion. Politically, Swahili towns were structured through local rulers and sultans, with wealthy merchant families holding significant power in some towns. While the Swahili seem to have become more culturally, religiously and linguistically distinct from their neighbours in the early second millennium, they continued to interact with peoples of the East African hinterland and interior in various ways, connected through kinship, marriage, blood-brotherhoods, slavery, clientship and trade (Kusimba Reference Kusimba, Hauser and Haines2023; Kusimba & Kusimba Reference Kusimba, Kusimba, Wynne-Jones and LaViolette2018).

Several Swahili towns have their foundations in the early second millennium, a time when many settlements became more urban and socially complex, while increasing their integration into Indian Ocean trade networks. One of these towns is Tumbatu, a sprawling stone town located on a small eponymous island just off the coast of Unguja (Zanzibar) in Tanzania. Today the site itself is unoccupied and used mostly for agriculture, but its legacy remains evident in the numerous stone ruins that scatter the area. Together with a team of local heritage practitioners and students, I carried out shovel test pit (STP) surveys and excavations at Tumbatu and neighbouring Mkokotoni in 2017 and 2019. The field work revealed two settlements occupied between c. 1000 and 1400 and with a shared material culture, the majority of which were pottery and glass beads (Rødland Reference Rødland2021). Both sites would have been connected to long-distance trade networks with the Indian Ocean, with imports from Arabia, India, China, and southeast Asia and with mainland Tanzania and the broader interior of eastern Africa. These regional trade routes would have brought various goods as well as enslaved people.

Slavery is notoriously difficult to uncover archaeologically, and the majority of slavery studies in East Africa focus on the period after 1500. As slavery is assumed to have been relatively small-scale in the medieval period, with most slaves working in domestic or agricultural contexts, we are unlikely to uncover houses or storage facilities related directly to slavery and slave trading. In this paper I present a preliminary study, in which I seek to look for the subtle traces of slaves through their everyday material culture. I do this by examining a small selection of pottery types from Zanzibar that do not fit into wider Swahili pottery assemblages, and which may thus have been produced and used by female slaves and/or migrants. Most slaves would have been culturally and religiously different from the main population of Swahili towns, which to some extent would have been reflected in their material culture. Through a material culture of difference, we can recognize enslaved and non-elite migrants and allow for a fuller understanding of socio-economic and cultural complexity in Swahili towns.

Swahili connections: trade, migration and cosmopolitanism

The earliest Swahili settlements of the sixth and seventh centuries ce were founded by groups of people from the East African hinterland and interior with mixed agricultural and pastoralist subsistence economies (Horton & Chami Reference Horton, Chami, Wynne-Jones and LaViolette2018). The language that developed on the coast, Kiswahili, is a Bantu language (Nurse & Spear Reference Nurse and Spear1985). These coastal people took full advantage of what the sea had to offer in forms of both subsistence and trade, and some settlements grew to become wealthy and urban towards the eleventh century. These Swahili towns thrived at the intersection of different cultures and trade-networks, drawing in people from neighbouring settlements and the East African interior, as well as more far-flung port cities in the Indian Ocean. Swahili towns offered opportunities to trade and engage in various arts and crafts, and became cosmopolitan and multi-cultural in their character. When the first Portuguese sailors and soldiers entered this part of the Indian Ocean, travelling up the coast from Mozambique, they encountered people with various religions, ethnicities and ways of dressing (Newitt Reference Newitt2002, 4).

The slaves wear a cloth from the waist to the knees; all of the rest is naked. The white Moors who are the owners of these slaves wear two cotton cloths, namely one tied at the waist that reaches to the feet, and another that falls loosely from the shoulder and covers the waistband of the other, their bodies are well shaped and their beards large and frightening to see.

Account of the Voyage of D. Francisco de Almeida, Viceroy of India, by Hans Meyr 1506. (Newitt Reference Newitt2002, 14)

The observations made by the Portuguese were influenced by racial and religious bias (Elbl Reference Elbl2007). However, these and other historical texts by Muslim and Portuguese visitors to the coast show that Swahili towns like Kilwa, Sofala and Mombasa were home to people of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, including migrants and slaves. Portuguese sources also describe a system of agriculture in which mainland clients worked in fields owned by Swahili patrons (Vernet Reference Vernet, Weldemichael, Lee and Alpers2017), further highlighting the interconnectedness of Swahili coastal residents with their neighbours. Recent genetic studies have further shown the complex ancestries of the medieval Swahili: ‘More than half of the DNA of many of the individuals from coastal towns originates from primarily female ancestors from Africa, with a large proportion—and occasionally more than half—of the DNA coming from Asian ancestors’ (Brielle et al. Reference Brielle, Fleisher and Wynne-Jones2023, 866). These findings are echoed in local foundation myths and chronicles from towns such as Tumbatu, Kilwa, Mombasa and Pate, that emphasize the arrival of ancestors from Persia or Arabia, often marrying local women (Gray Reference Gray1962; Ingrams Reference Ingrams1931; Pawlowicz & LaViolette Reference Pawlowicz, LaViolette, Schmidt and Mrozowski2013). While these myths have been widely debated and are historically complex (Pouwels Reference Pouwels1984; Spear Reference Spear2000), they show the central role migration and cultural exchange have played in the development of these towns over a long period of time, and in how the Swahili conceptualize themselves. However, apart from the DNA study cited above, there are few direct traces of migrants or archaeological evidence for migrant communities. We can only assume that some of the material goods found in Swahili towns arrived with or belonged to people from places beyond the coast, including the East African hinterland and interior.

In this article, I use the terms slave and migrant deliberately, as both groups of people may have left material traces of difference—including pottery. By including both groups, I recognize that they often, but not always, overlap; many slaves would have been migrants, and some migrants were slaves. However, I focus specifically on slaves because they are a group of migrants for which we have the most historical documentation, if still limited, particularly for Zanzibar. The study of pots also allows for a gendered perspective, as historically most potters were women. Female migrants may have arrived to the coast for a variety of reasons—to engage in trade, apply their craft, seek marriage partners, or escape violence or raids. Migrating women may initially have found themselves within a system of asymmetrical dependency in socially stratified Swahili towns, in which they would have relied on patrons, family members, or husbands to access trade and production networks. But many would also have arrived as enslaved people. The majority of slaves transported in the Indian Ocean during the medieval period were women, and therefore a significant number of migrating women are likely to have been slaves. Given that the potters in this study were migrant women, and that most slaves were also women, it is plausible—although not provable—that some migrant potters were enslaved women.

The aim of this study is not to prove the existence of slavery or assess its scale. Rather this approach aims to look at the small material traces enslaved people and non-elite migrants may have left behind in their everyday practices and interactions. I do this by approaching material culture that differs from the general assemblage of Tumbatu and Mkokotoni—specifically pottery. I approach it as a material culture of difference, in which the cultural backgrounds of migrants were reflected in some of the things they created and used in their daily lives. Coastal communities were firmly rooted in East African culture and traditions, yet were also socially, culturally and economically mixed; migrants seem to have been commonplace, easily incorporated into the socio-economic fabric of the towns. Looking for individuals with diverse backgrounds in such contexts is therefore challenging but, as I will argue, not impossible. This approach also allows us to consider how archaeologists can investigate differences in socio-economic identity on the Swahili coast, their material remains, and ways of thinking about belonging and agency. Contrary to later Euro-American systems of slavery, which were based heavily on ideas of race, slaves in East Africa were not grouped together based on ethnic background alone and would have been a heterogenous group. However, their cultural difference would have played a role in their enslavement; generally, people did not enslave their own. Slaves would have thus been culturally, linguistically and religiously different from the main population of the towns. This difference is therefore a key to locating slaves in the material record, as it would have been articulated through slaves’ use of and access to food, clothing, ornaments, personal belongings, pots, etc. While archaeologies of slavery in Africa are challenging, it is worthwhile to consider how we might overcome these methodological challenges (Alexander Reference Alexander2001; Lane & MacDonald Reference Lane and MacDonald2011; Robertshaw & Duncan Reference Robertshaw, Duncan and Cameron2008; Rødland et al. Reference Rødland, Wynne-Jones, Wood and Fleisher2020).

Zanzibar and slavery in the second millennium ce

The Zanzibar archipelago is located off the coast of mainland Tanzania. Its two main islands are Unguja and Pemba, although many refer to the former simply as Zanzibar. The islands played an important role in the networks of slave trading that expanded on the East African coast from the seventeenth century ce, a network that saw thousands of slaves carried between Madagascar, the Comoros, East Africa and various ports in the Indian Ocean. Of 1600 slaves registered in Zanzibar in 1860–61, the majority originated in modern-day Malawi, southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique (Vernet Reference Vernet and Ness2013, 4). According to Vernet (Reference Vernet, Mirzai, Montana and Lovejoy2009, 50), Zanzibar was one of the primary areas from which Portuguese in Mombasa bought their slaves in the seventeenth century. Whether Zanzibar was used as a port for the translocation of slaves or as a source is unclear. After the sultan of Oman moved his capital to Zanzibar in 1840, a substantial slave-based plantation economy also developed on the islands under Omani and Swahili landowners, to some extent based on earlier systems of agriculture and labour (Vernet Reference Vernet, Weldemichael, Lee and Alpers2017).

While the role of Zanzibar as a hub for slavery and slave trading intensified dramatically between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, some historical evidence suggest that the islands were already involved in slave trading from the late first millennium ce onwards. Writing as early as the ninth century, Arab scholar Al-Jahiz claims that Qanbalû was a source of slaves to the Arab world (Allen Reference Allen1993, 73)—Qanbalû likely refers to Pemba (LaViolette Reference LaViolette, Reid and Lane2004). Chinese writers Tuan Ch’eng-shih (ninth century ce) and Chu-fan-chi (thirteenth century ce) claim that the kidnapping and sale of women and children took place on the Somali coast, in Madagascar and maybe also Pemba, although maintaining that the main export products were ivory and ambergris (Chau et al. Reference Chau, Hirth and Rockhill1911, 128–9; Freeman-Grenville Reference Freeman-Grenville1962, 37). In an eleventh-century account from eastern Arabia, Zanzibari slaves were seen working in the oasis of Al-Ahsa (Khusraw Reference Khusraw2001, as cited in Kloss Reference Kloss, Pargas and Schiel2023, 143). In a Chinese map originating between 1311 and 1320, Zanzibar is marked as a source of slaves (Snow Reference Snow1988, as cited in Horton in prep.). While these sources refer to the export or translocation of slaves via the Zanzibar archipelago, slaves would also have worked locally within Swahili settlements. The number of slaves living in Swahili towns during the medieval period would have varied at different settlements, depending on local factors and economic structures. Zanzibar may have relied more heavily on slave labour than other Swahili settlements, especially for agriculture. The islands are large and fertile; Pemba in particular has a long history of agricultural production, and was able to create surplus for trade with other coastal towns (Vernet Reference Vernet, Weldemichael, Lee and Alpers2017). But unlike many other towns on or near the mainland, Zanzibar did not have immediate hinterland neighbours from which landowners could employ clients to work the fields. Lacking such relationships with non-Swahili populations, landowners in Zanzibar may instead have brought slaves to work the land surrounding their towns. For example, Portuguese writer Bocarro noted in 1634 that inhabitants on Pemba had brought cafres to the island to cultivate (Vernet Reference Vernet, Mirzai, Montana and Lovejoy2009, 53). The term cafre was variously used to describe East Africans or enslaved Africans (Gharala Reference Gharala2022). The practice of using slaves in agriculture has also been documented in Pate as early as the sixteenth century ce (Vernet Reference Vernet, Mirzai, Montana and Lovejoy2009, 53)

Medieval sources also mention slave trading and the use of slaves elsewhere on the Swahili coast, including Ibn Battuta’s account from Kilwa in 1331 (for brief overview, see Rødland et al. Reference Rødland, Wynne-Jones, Wood and Fleisher2020). Later Portuguese texts also refer to enslaved people living and working in Swahili towns from the 1500s onwards. There are no reliable data for the scale of slavery within Swahili East Africa before 1500, and scholars such as Vernet (Reference Vernet and Ness2013) have referred to it as minor during the late first and early second millennium. However, he also notes that servile status could be ambiguous, and different forms of dependency and servitude existed at the same time, relating to varying social and economic roles. When we consider the common use of enslaved people in the Islamic Indian Ocean during the medieval and early modern periods, and the rapid expansion of slave trade from East Africa by the Portuguese from the sixteenth century based on existing slave trade networks, I would argue that the presence of enslaved people in Swahili African towns was not insignificant, particularly in Zanzibar. However, more research is needed to understand slavery in this period more fully. Additionally, we know little about the experiences of slaves at this time and their role in society. However, based on comparisons with contemporary Islamic slavery and later African forms of slavery, we can infer that the function of slaves was mainly social and cultural. The majority of slaves are assumed to have been women, brought into service as domestic servants or concubines as elsewhere in the Islamic world (Urban Reference Urban2022), and as a show of wealth; slaves and other dependents played an important role in elite display of wealth, status, and power on the Swahili coast (Vernet Reference Vernet and Ness2013, 2). There is little to indicate a slave-based economy or significant segregation between enslaved and free people. We can therefore expect that slaves were able to integrate into the dominant society after some time, if they adopted religious and cultural norms. Slaves may also have been used in certain productive roles, such as agriculture, especially where labour was in short supply, such as in Zanzibar.

It is unlikely that the Zanzibar Swahili were themselves slave raiders. Enslaved persons would probably have arrived to the coast through trade routes that also brought other commodities, either by land or by sea. One such route could have been via Pangani Bay, an area on the mainland just opposite Zanzibar where several second-millennium ce settlements have been recorded (Mjema Reference Mjema, Sadr, Esterhuysen and Sievers2016; Walz Reference Walz2010). Some of these have shown medieval trade links with interior settlements that follow later known caravan routes, attesting to ancient links between the coast and the interior (Walz Reference Walz2010). It is difficult to establish direct links between specific settlements, however. Artefacts such as glass and marine shell beads and imported pottery found at interior sites show links with the coast, but not through which towns the goods travelled or how direct the trade was. Likewise, many goods would have travelled from the interior to the coast, such as rock crystal, iron and ivory. Some information can also be gleaned from later caravan routes that increasingly came to carry slaves and ivory from the interior to the coast. Among these we find the nineteenth-century route between Pangani and Lake Victoria (Biginagwa Reference Biginagwa2012), which may partly or fully have followed older routes. Slaves may also have entered Zanzibar via the sea, and the use of Madagascar and Mozambique as a source for slaves mentioned in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Portuguese sources may have older roots. As early as 1506, Afonso de Albuquerque writes about Madagascar: ‘for the ships from Melinde and Mombasa come there to trade and in exchange for these things take away many slaves and provisions’ (Newitt Reference Newitt2002, 19). In addition, it is possible some slaves arrived into East Africa via Arab or north-east African traders, as the areas in inland Ethiopia and Sudan were extensively used as sources for slaves to the Arab world and beyond (Collins Reference Collins, Jayasuriya and Angenot2008; El Hamel Reference El Hamel2013).

Tumbatu and Mkokotoni in northern Zanzibar

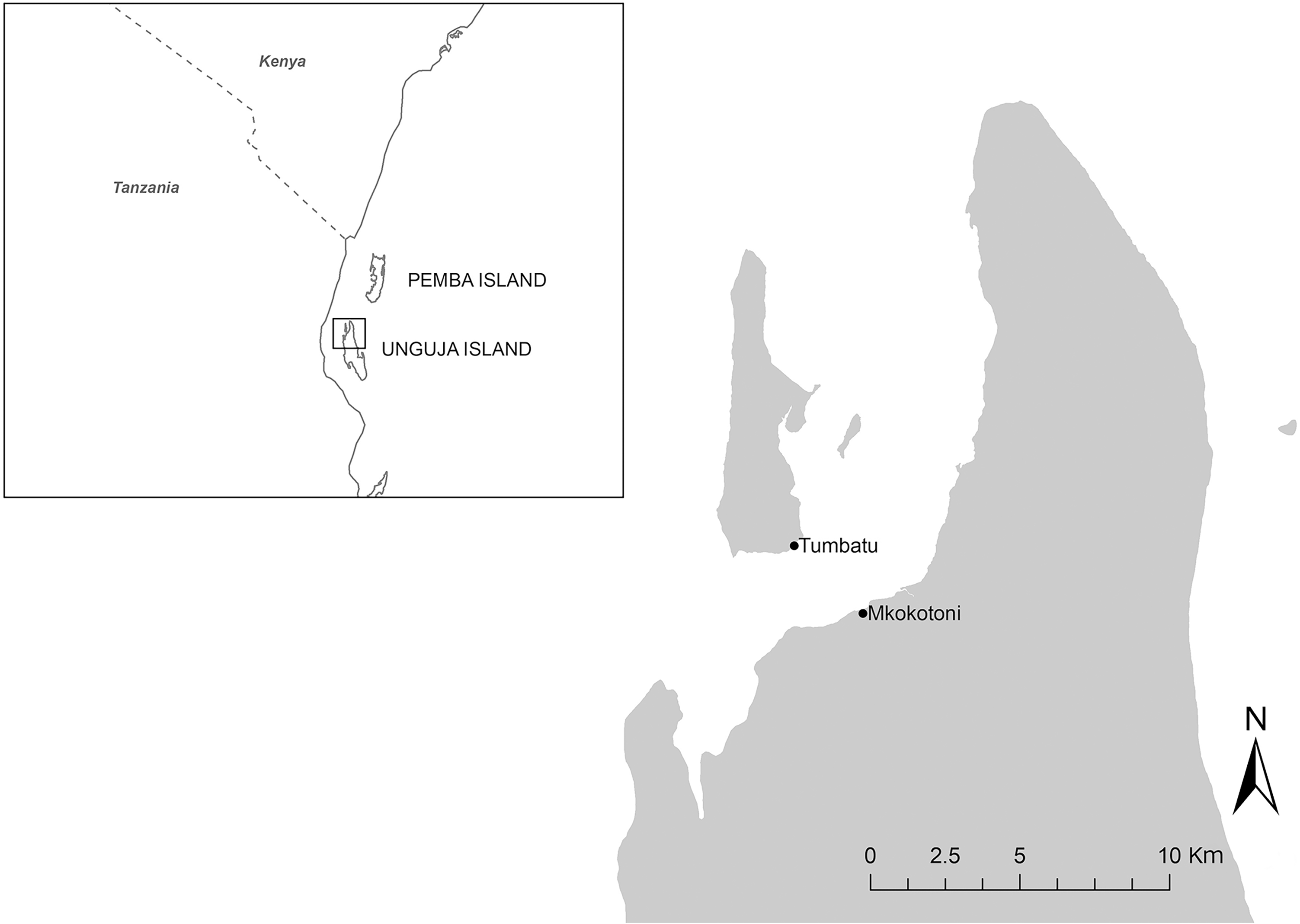

In north-western Unguja lie the two early second-millennium ce settlements Tumbatu and Mkokotoni (Fig. 1). Tumbatu (c. 25 ha) is an old stone town on the small eponymous island opposite Mkokotoni, and still contains around 150 stone house ruins and house mounds as well as several mosques. Mkokotoni is a smaller site, around 9 ha, with little visible architecture. Modern settlements are located near both archaeological sites, but today the sites themselves are mostly uninhabited and used for farming. The two sites were explored archaeologically during two seasons of fieldwork in 2017 and 2019. These included shovel-test-pit surveys covering the known extent of the sites and excavations of nine trenches in total. The excavations uncovered parts of two domestic buildings in Tumbatu, while three trenches in Mkokotoni revealed a probable workshop used in the processing or production of glass beads. We used the single context method to excavate all trenches at both sites. The deposits were heavily mixed: rubble layers from the collapse of the stone walls were mixed with artefacts, making fine-scale interpretations of the use of space over time unfeasible. However, we recovered very few modern inclusions and datable finds relate to the period between 1000 and 1400 ce. We can therefore assume that while contexts were mixed, they still reflect the main occupation period of the two sites. The most common artefacts recovered were local pottery, imported pottery, glass beads and various pieces of metal, in addition to marine shells and animal bones. The finds correlate to what has been found at other contemporary Swahili sites, although expected differences in quantities occur. One notable discovery was the complete lack of evidence for wattle-and-daub houses in Tumbatu during the STP survey in 2017. This is unusual for any Swahili settlement, which generally contain a mix of stone and daub housing, or only the latter.

Figure 1. Map of northern Zanzibar with the two sites marked.

While they are two separate archaeological sites, I have argued elsewhere that Tumbatu and Mkokotoni formed one large townscape linked together by trade, production and socio-economic relationships (Rødland Reference Rødland2021). They are only separated by the Tumbatu channel, 3 km wide between the two settlements and easily traversed by boat. The two sites were occupied between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries ce, although previous work in Mkokotoni by Mark Horton and Catherine Clark showed signs of earlier settlement as well (Clark & Horton Reference Clark and Horton1985; Horton & Clark Reference Horton and Clark1985). From the geographical location and archaeological data, I infer that Tumbatu was a trading entrepot with links to local, regional and long-distance ports, while Mkokotoni was mainly a productive centre from where the urban population gained food, pottery, and other everyday items. The evidence for glass bead production in Mkokotoni highlights the mixed economy of this site and its inclusion in long-distance trade and production networks. As such, the larger Tumbatu–Mkokotoni townscape housed a diverse population of varying socio-economic roles, which likely also included enslaved labourers working in domestic and agricultural contexts.

Ceramics as source: ‘outlier’ pottery from Tumbatu and Mkokotoni

Approaching slavery and migration through pottery

While there have been long-running debates regarding the link between cultural or ethnic groups and pottery styles (Gosselain Reference Gosselain2000; Gosselain & Smith Reference Gosselain, Smith, Lane and Mitchell2013; Jones Reference Jones1997, 199; Kelly Reference Kelly2015; Lane Reference Lane, Richard and MacDonald2015), many studies still emphasize the ways in which pottery production techniques, style and use are influenced by culture in various ways, as well as through the potter’s kin networks. The notion that pots can tell us something about a person’s cultural or ethnic identity (or geographic background) has implications for methodologies of slavery research, as shown by a small number of case studies. In her study of potters in the Kadiolo region in southern Mali, Frank (Reference Frank1993) observed that local potters made pots in the style of other Mande potters, but used a different production technique, taught to them by their mothers and mothers’ mothers. Frank suggests the ancestors of these women potters may have been enslaved, thus bringing their own learned production technology to a new place, but adopting the local style. A more well-known case can be found across the Atlantic, where the presence of broadly similar earthenware pottery recovered from archaeological sites in the Caribbean, USA and South America have been understood to relate to the presence of enslaved people. Referred to as colonoware or Afro-Caribbean ware, the pottery is thought to reflect certain practices of production found in West and Central African societies, but also influenced by native American traditions (Hauser & DeCorse Reference Hauser and DeCorse2003). Studies such as these highlight that pottery styles are sensitive to culture, migration and change, but that local socio-economic factors impact how pots are made, by whom, and what form and style they take. Aspect such as trade, need, technical style and ethnic/cultural distinctions play a role in how pots are used and understood.

Pottery on the Swahili coast

The importance of potsherds to our understanding and study of Africa’s past cannot be underestimated. Pots, and their decoration, shape, production technique, fabric, finish, use and trade, have highlighted movements of people, things and foods as well as social relations between groups (Gosselain Reference Gosselain, Roberts and Vander Linden2011; Lane Reference Lane, Richard and MacDonald2015). In coastal East Africa, ethnographic and ethno-historical studies have demonstrated that the majority of potters were women, and that knowledge of pottery production was passed down from mother to daughter or within other familial relationships (M’Mbogori Reference M’Mbogori2013; Walz Reference Walz2010, 322; Wandibba Reference Wandibba, Kusimba and Kusimba2003). This was probably also the case in the earlier Swahili settlements, and production would most likely have taken place on a household scale, with the trade in pots occurring over relatively short distances and within the community (although see Fleisher & Wynne-Jones Reference Fleisher and Wynne-Jones2011; Namunaba et al. Reference Namunaba, Wandibba and Wahome2022). The extent of specialization and trade in pottery is unclear, but pottery production is a specialized skill and only some women would have been potters (Wandibba Reference Wandibba, Kusimba and Kusimba2003). During interviews with potters in coastal Kenya, M’Mbogori (Reference M’Mbogori2013, 115–18) also found that many potters were of low status. This is also echoed in Wynne-Jones and Mapunda’s (Reference Wynne-Jones and Mapunda2008, 9–10) work on Mafia Island. Pottery production has become rare on the coast today. Conversations with local inhabitants in Tumbatu suggested there are no clay sources on the island, and while this has not been confirmed, the thin and sandy soil cover in the southern part of the island supports this. If this were the case, it is likely that pots were purchased in Mkokotoni or other nearby settlements, suggesting some specialized production.

Different pots had different uses, and while the main function was to prepare, store and serve food and beverages, they would also have been used in feasting events, where food and pots were used in public displays of wealth and generosity (Fleisher Reference Fleisher2010). Shared decorative motifs may have been important in such contexts to confirm social bonds and familial relations and display the shared values of the people present. During her ethno-archaeological work on the Kenyan coast, Donley-Reid (Reference Donley-Reid1990) also found that pottery decoration in more recent times was associated with spiritual protection. These multiple layers of meaning can help explain the widespread use of similar pots along the East African coast, and why change was rare or slow. Pottery from Swahili sites shows a high degree of similarity and continuity over time, and while there are also regional and local differences, a ‘Swahili tradition of ceramic manufacture’ (Croucher & Wynne-Jones Reference Croucher and Wynne-Jones2006, 120) can be recognized. These similarities show networks of pottery production spanning long distances and suggest shared practices of food consumption, ritual and feasting. Several studies have also indicated that this continuity persists despite significant social and economic changes and migration, such as the growth of slavery, plantation production, capitalism and colonialism occurring along the coast in the eighteenth to twentieth centuries (Croucher Reference Croucher and Marshall2015a; Mjema Reference Mjema2024; Wynne-Jones & Mapunda Reference Wynne-Jones and Mapunda2008). During her work at nineteenth century plantation sites in Pemba, Croucher (Reference Croucher and Marshall2015a,Reference Croucherb) noted that the pottery recovered from areas inhabited by enslaved populations bore much resemblance to local pottery styles that had been produced in Pemba for several hundred years, suggesting slaves chose to conform to local types of pottery manufacture rather than continuing the traditions from their various home-regions. This is also demonstrated in the ethnographic study by Wynne-Jones and Mapunda (Reference Wynne-Jones and Mapunda2008) on Mafia Island in Tanzania, where Makonde immigrant potters would produce pots in the local Mafia style, using techniques learned on Mafia, rather than those styles and techniques learned from their homelands. These observations have several implications for how we understand the Swahili, as they show that pottery styles may not reflect socio-economic changes or ethnic belonging in past settlements, and that some immigrants to Swahili East Africa saw it necessary or desirable to adopt local ceramic practices related both to production and use of pots. This may have been one way for outsiders to integrate into local societies and take part in shared practices. ‘By choosing to create pots of the same type along the coast, potters simultaneously signalled their inclusion within a particular group and their difference from inland neighbours’ (Wynne-Jones Reference Wynne-Jones2007, 337). This conservative homogeneity in pottery style complicates the study of immigrants and outsiders in Swahili society through pottery; however, it also highlights the uniqueness of those pots that do not fit this style and begs the question of why some potters chose to make different types of pots. Pottery has great potential to inform slavery studies, if we bear in mind the historical contexts in which pots were made.

The Tumbatu and Mkokotoni pottery

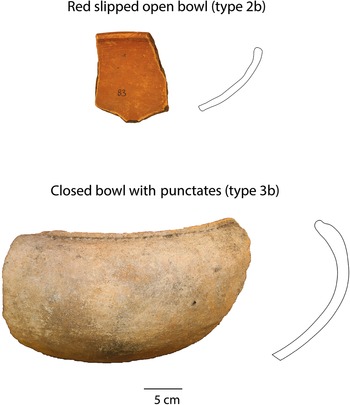

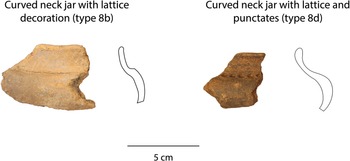

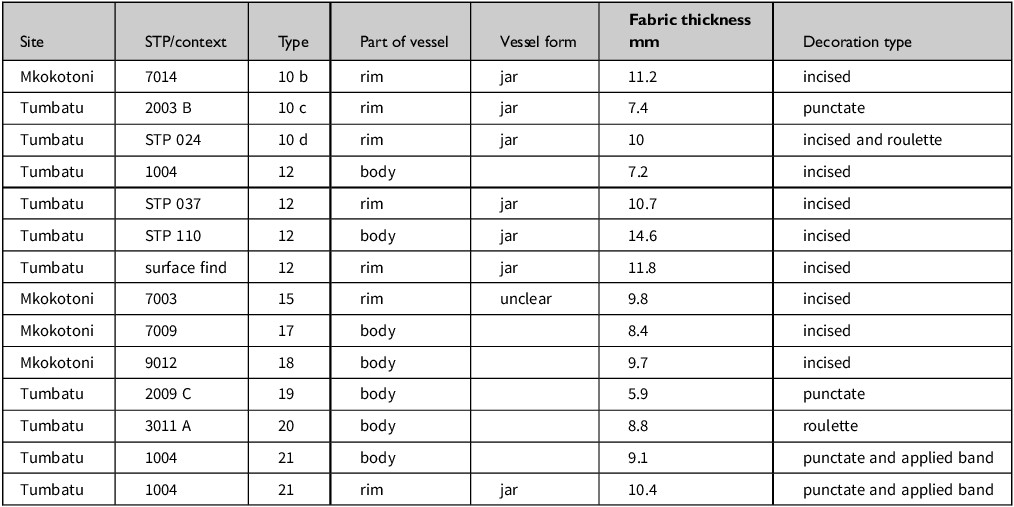

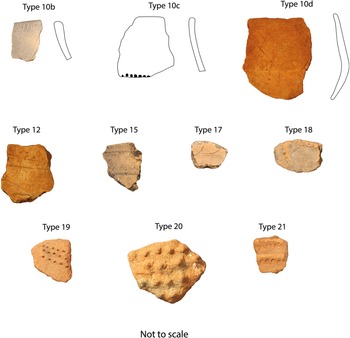

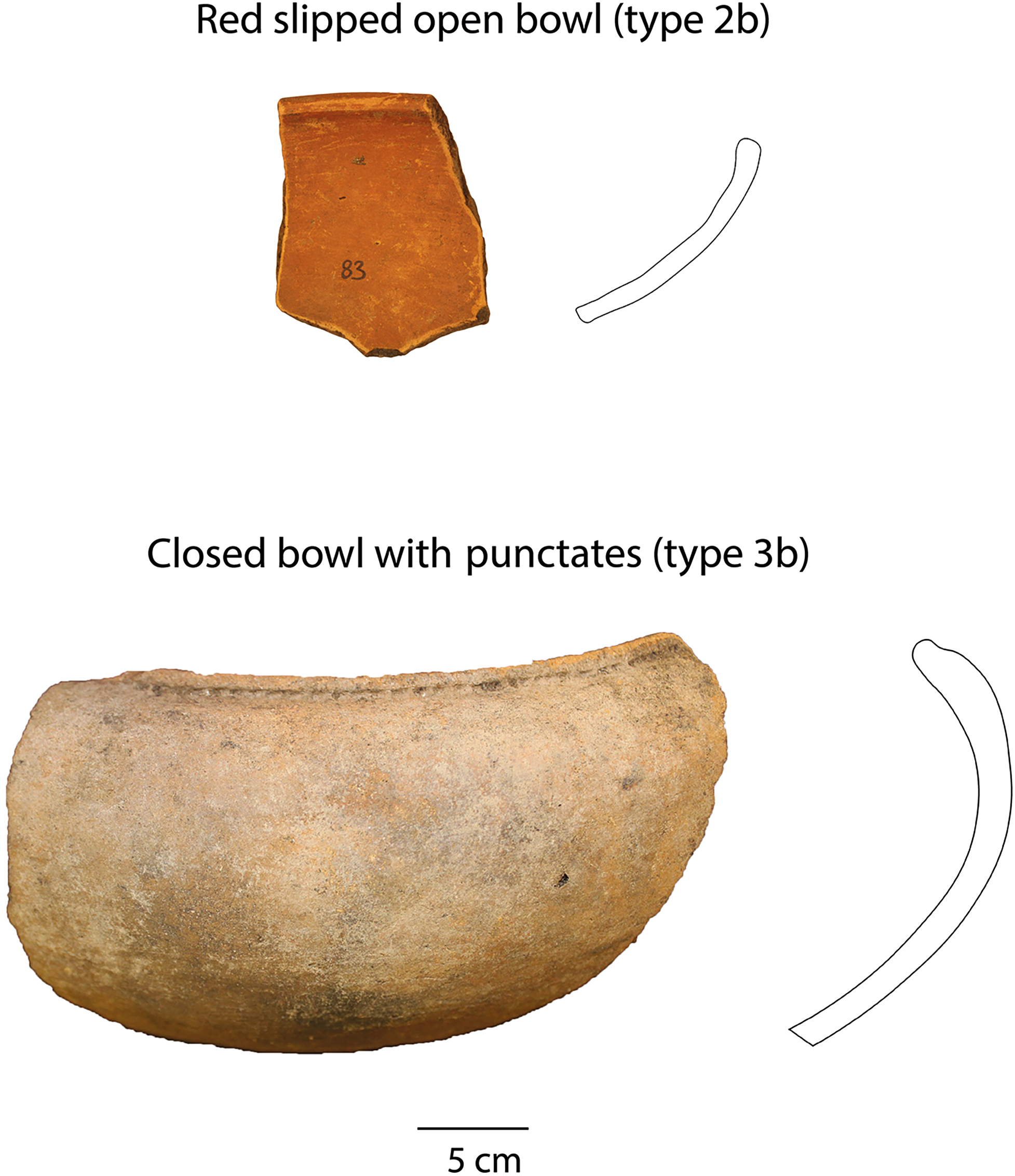

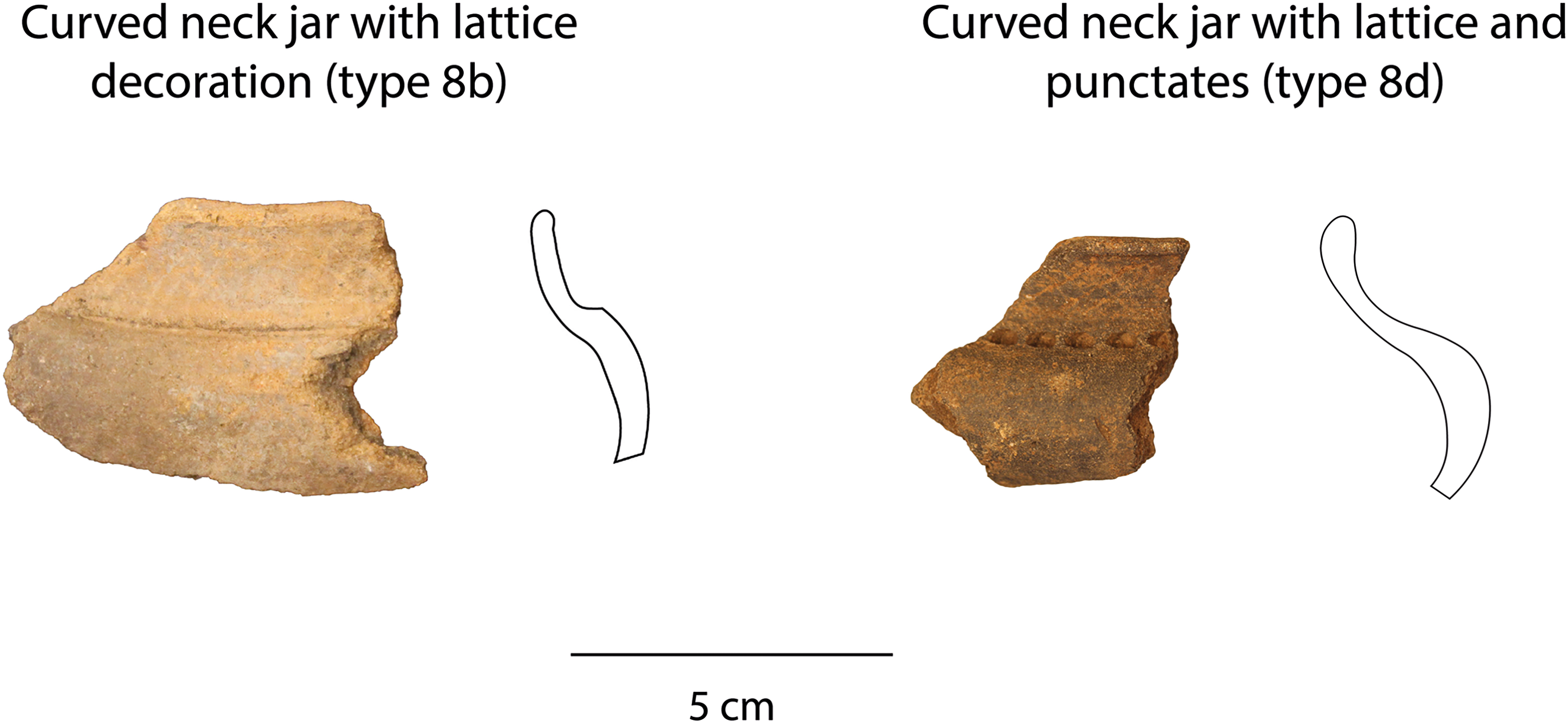

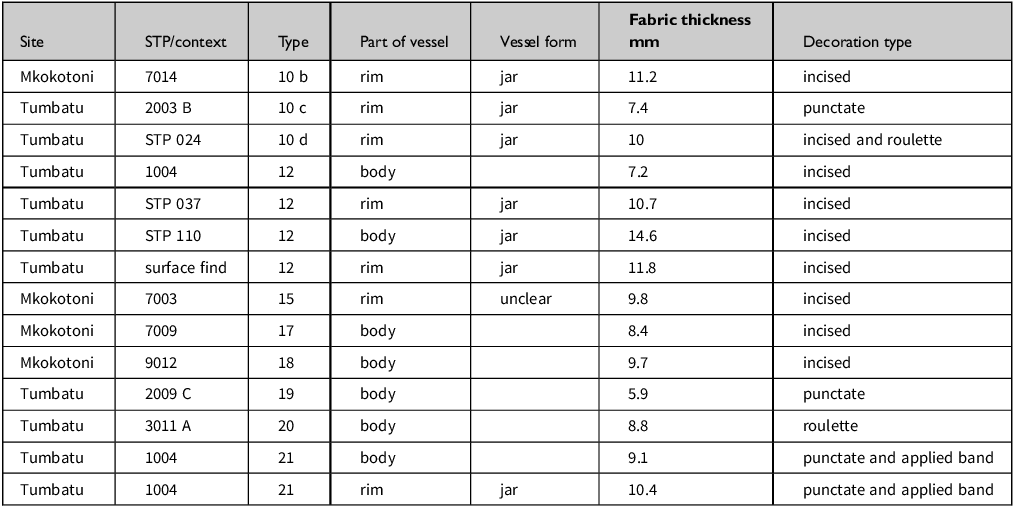

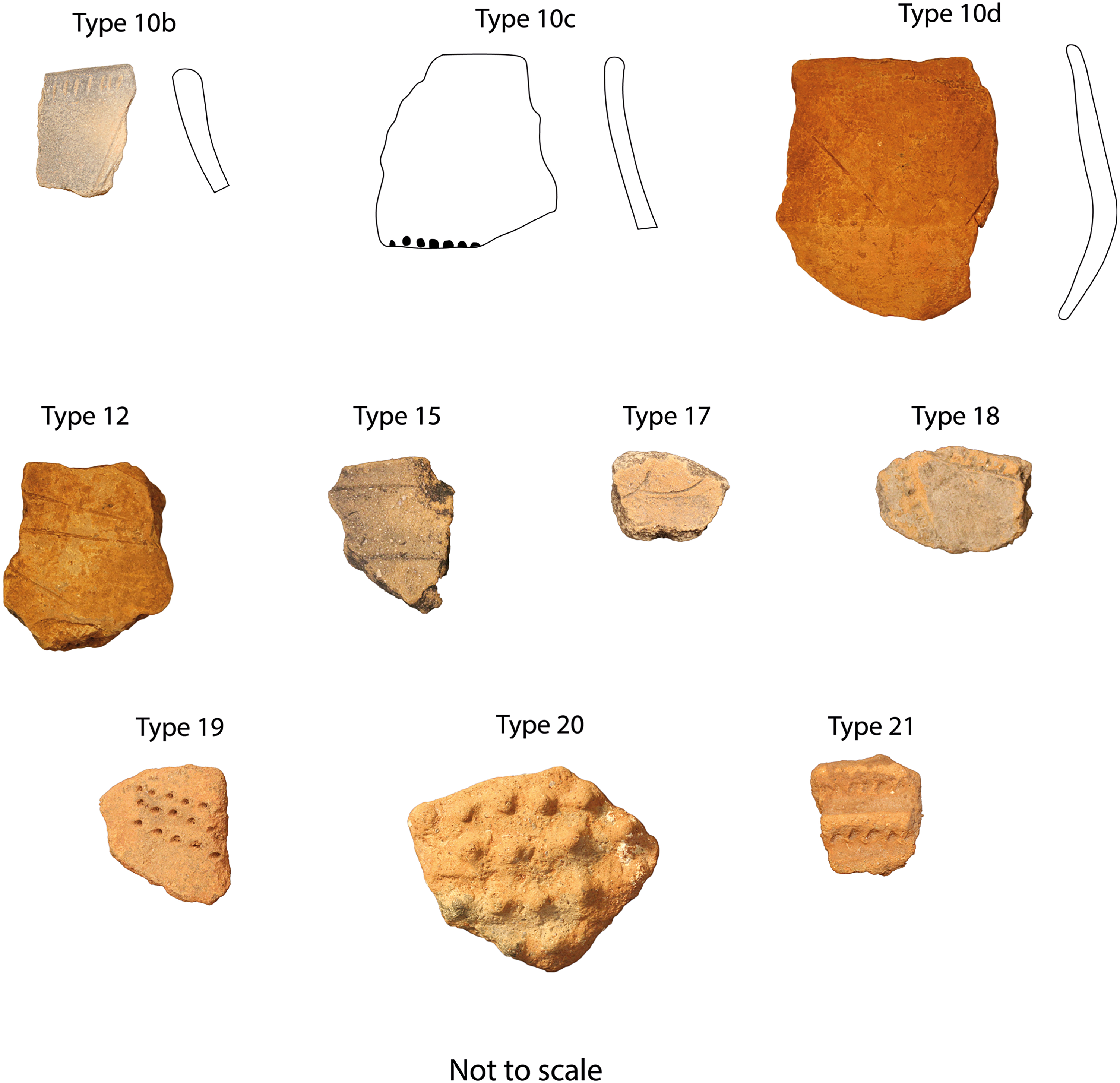

Different categories of ceramic objects were recovered in Tumbatu and Mkokotoni, including spindle whorls, gaming pieces, bottle stoppers and a lip/ear plug. The majority, however, were earthenware pots of local manufacture with and without decoration. While most likely produced locally in and around the two sites, they share stylistic similarities with pots found at contemporary sites all along coastal East Africa, fitting into a wider Swahili style of pottery from the first half of the second millennium ce. This period is characterized by less variety and elaboration in decoration and pots are often quite simple. This is also true for Tumbatu and Mkokotoni: the assemblage was relatively simple and uniform in terms of decoration and form. In total, 11.6 per cent (n=1084) of the whole assemblage was considered diagnostic, i.e. containing elements such as decoration, rim, base, handles, and/or carinations. The most common types according to these diagnostic sherds were undecorated open bowls, followed by red-slipped open bowls, undecorated closed bowls and closed bowls with a row of punctate decoration just below the lip (Fig. 2). These bowl types together make up c. 70 per cent of all types in Tumbatu and 73 per cent in Mkokotoni. Undecorated or decorated jars make up most of the remaining types, where decoration is usually in the form of lattice decoration and/or a row of punctates on the neck (Fig. 3). A small number of sherds did not fit this general style and may be of a local Mkokotoni/Tumbatu style, but nevertheless show an overall similarity to Swahili ceramics in terms of decoration style and/or vessel form. This regional difference between settlements has also been noted elsewhere on the coast, and is expected. The relative conservatism of Swahili pottery, as discussed above, makes deviation from the norm particularly noticeable. A small collection of pottery sherds from both sites differs from this general style significantly enough to consider them non-local in style, based mainly on their type of decoration design, which was the most significant variable. I will refer to these as ‘outlier’ pottery. These are the sherds relevant for this study, and number only 14 altogether (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Below I compare the various features of the different pottery types that may indicate choices made during the production process. However, the analysis was aided only by a handheld magnifying glass; future analysis may involve more detailed chemical and petrographic analysis that was not possible at this time.

Figure 2. Common pottery types found in Tumbatu and Mkokotoni. (Photographs and drawings: author.)

Figure 3. Pottery types found in Tumbatu and Mkokotoni. (Photographs and drawings: author.)

Table 1. Sherd information for outlier pottery types.

Figure 4. Outlier pottery types from Tumbatu and Mkokotoni. (Photographs and drawings: author.)

Clay fabric

The Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery has clay fabrics of variable quality and inclusions, with the most common inclusion/temper being sand. Other inclusions recorded were shell, grog, coral, organic materials and mica/quartz. Some vessels (16 per cent) had a finer, well-prepared fabric with small inclusions, and these pots are of better quality than the rest. This variability in clay fabric has also been recorded for other sites, and in her work on pottery from the Swahili sites Manda and Ungwana, M’Mbogori (Reference M’Mbogori2013, 213) proposes it relates to the use of different clay sources. The fabric of the outlier pottery is similar to that of the broader assemblage, the main inclusions being sand, and no observable difference was recorded between the fabric of the outlier pottery and the general Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery. This strongly suggests the outlier pottery was produced using the same clays and tempers as the locally made Swahili pottery, and did not arrive to the sites via trade or exchange.

Forming technique

Evidence of the forming technique of pottery vessels may be visible in the clay fabric and recorded through micro-fabric analysis (Lindahl & Pikirayi Reference Lindahl and Pikirayi2010, 137–8; M’Mbogori Reference M’Mbogori2013, 187). Unfortunately, this was not recorded during initial analysis of the pottery in 2019, although some general observations can be made based on surface inspection of the sherds and analogies with other assemblages. M’Mbogori’s (Reference M’Mbogori2013) careful analysis of local pottery from Manda and Ungwana revealed that all the pots were formed with a technique of drawing the walls upwards from a lump of clay. The rim was then added as a coil (or coils). This technique has also been recorded on pottery from Unguja Ukuu (Reference HicksHicks forthcoming). This seems highly likely to be the case for the Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery as well, where surface inspection of a selection of sherds showed no indication of coils below the rim, indicating the body of the pot was made by drawing and the rim added as a coil. The outlier pottery similarly does not show clear signs of forming technique, and some sherds were too small or worn to be useful. However, one sherd has indications that the rim was added as a coil (type 10b). Another has evidence of cracking that has likely occurred due to shear stress, a sign that the vessel was formed by drawing (type 10d: Elizabeth Hicks, pers. comm. 2025). However, as many different population groups in East Africa use this form of drawing technique (Gosselain Reference Gosselain2000; M’Mbogori Reference M’Mbogori2013, 6), forming technique may not be a reliable indicator of different cultural groups.

Vessel shape

In cases where vessel shape could be determined, most of the Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery were open bowls (56.7 per cent), followed by closed bowls (26 per cent), curved-necked jars (10.1 per cent) and straight-necked jars (5.4 per cent). A small number were plates (1.8 per cent). For the outlier pottery, the vessel form was difficult to determine due to the small size of many of the sherds. Those whose form could be determined were two jars with straight necks (types 10c and 10d), two jars with curved necks (type 12 and 21) and two jars where neck shape is unclear. The thickness of the sherds falls between 6 and 14.6 mm, which is within the range of the overall assemblage.

Finishing

The Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery showed signs of several different finishing techniques used by the potters. This is consistent with observations made on pottery from other coastal settlements. The most common of these techniques is smoothing, which leaves little to no marks, probably with wet hands or cloth; some of the sherds also showed signs of scraping with a harder tool such as a shell or wood; a small number of pots had been burnished with a hard/smooth tool such as a pebble (M’Mbogori Reference M’Mbogori2013). Five of the outlier pottery sherds had a smooth surface finish, while the rest seem to have been left largely untreated. None of the outlier pottery showed evidence of burnishing or scraping with a hard tool.

Decoration

Decorative elements occurred on just 6.7 per cent of Tumbatu/Mkokotoni pottery, including slip, paint, burnish and plastic motifs. Most slip and paint were red or brownish red, or a silvery colour. Many of the slipped and painted vessels were also burnished. The most common plastic decorations were incised and/or punctates on the upper part of the vessel, made with a variety of hard and sharp tools before the vessel was fired. There is not much variation in these motifs. The outlier pottery was not decorated with slip or paint, and all decoration was plastic motifs. The decorative motifs differ from those of the main assemblage, and do not resemble common coastal types. Some have correlates with types found at other coastal sites but are generally rare, including types 17, 18, and 19 (Croucher & Wynne-Jones Reference Croucher and Wynne-Jones2006; Fleisher Reference Fleisher2003; Hicks forthcoming). A variety of tools and techniques would have been used to create the various decorations, the majority of which are incised (types 10b, 10d, 12, 15, 17 and 18). Some also have punctates (10b, 10c, 19 and 21). The punctates on type 10b may have been made with fingernail impressions. Two sherds are especially notable, as they include possible roulette designs (types 10d and 20). Roulettes typically do not occur in Swahili assemblages. Type 10d displays a possible cord roulette design underneath a more common incised motif. Cord roulettes are found elsewhere in East Africa from the early second millennium, including inland Tanzania towards Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria (Gosselain Reference Gosselain2000; Odner Reference Odner1971; Soper Reference Soper1985). Type 20 displays raised bumps (mamillations) that may have been made with a carved wooden roulette, as shown in Soper (Reference Soper1985, 34). These types of roulette are less common than the cord types, but can be found in areas around Lake Victoria (Soper Reference Soper1985). Type 21 also has an unusual design, created from applied bands of clay; the band was then punctuated with an angled tool to create an arch-like design (Elizabeth Hicks, pers. comm. 2025).

Spatial contexts/find location

Four of the sherds were found during the STP survey in Tumbatu, and did not cluster in any particular area. One was a surface find, and therefore cannot be dated confidently; however, the site is not inhabited today and is used only for farming, so surface remains are likely to stem from the occupation period between 1000 and 1400 ce. Six sherds were found during excavations in Tumbatu, during which we uncovered remains of two separate coral stone houses. Six trenches covering 52,75 m2 were excavated in total. Three sherds were found in the first trench within the first house (two are likely from the same pot), in a context relating to a midden deposit covering the house and its walls (context 1004). The other three sherds were found in two separate rooms in the second house and may be related to domestic contexts. One of the rooms has been interpreted as a large communal room (contexts 2003 and 2009), used for entertaining guest and family members and serving food, and contained no production remains (Rødland Reference Rødland2021, 213). The second room (3011) was difficult to interpret, but may have been a storage area for valuables, raised above the floor of the house. However, most contexts were mixed with floor fill and/or coral rubble, so interpretations about spatial contexts are unreliable. Four of the sherds were recovered from excavations in Mkokotoni (contexts 7003, 7009, 7014, and 9012), where three trenches were excavated within an area that seems to be related to glass bead production or reworking (Rødland Reference Rødland2023). The three trenches covered an area of 10 m2, within which we uncovered two coral stone structures, one of which may have been a workshop and the other a furnace. While the primary function of the workshop was related to glass beads, remains of other activities included the spinning of thread, shell-bead making and food preparation and consumption.

Discussion: implications for Swahili society and future pottery studies

Key findings and interpretations

While Swahili towns of the medieval period are understood as cosmopolitan places, the focus has tended to be on merchants and elites and their material culture as reflected in the archaeology. But coastal towns would have been home to other migrants as well: people drawn to these urban settings to find work, reunite with family, or discover new opportunities. Many would also have come through forced migration, such as enslavement and pawnage. Specialized crafting may have been one important way for migrants to support themselves in urban settings. We can only speculate what opportunities were available to these migrants and how they participated in Swahili society; some may not have been able or willing to be fully incorporated and take on a coastal lifestyle. The Makonde potters interviewed by Wynne-Jones and Mapunda (Reference Wynne-Jones and Mapunda2008, 9–10) highlight this in a way that is particularly interesting to archaeologists. They chose to conform to the expectations of other coastal residents in terms of their pottery production, but they did not see themselves as part of that same community, nor were they accepted as such by the local residents. However, when they had an opportunity to do so by selling their pots to hotel owners, they made pots that fitted their own artistic and aesthetic style instead of the local style of pots. These insights are crucial, highlighting that disjunctions between people’s identity and their material culture can occur in ways that might not be visible in the archaeological record.

In the current study I suggest that some of the potters who lived and worked in Tumbatu and Mkokotoni were enslaved or migrant women, who chose to make certain pots that deviated from the norm or commonly accepted style of the coast. The 14 sherds used in this assessment were found in a variety of contexts, including domestic, productive, storage and outdoor areas. The sample is too small and the contexts too varied to determine the relationship between space, the pots and their makers. However, it does suggest that the users and producers of these pots were working and possibly living in these varied spaces, perhaps as domestic servants, agricultural labourers, craft specialists and artisans. Tumbatu was a town whose main function lay in mercantile activities and whose population seems to have been relatively wealthy. Domestic workers, either enslaved or free, may have carried out other types of tasks unrelated to these merchant activities. Especially work considered dirty may have been relegated to servants and slaves, to allow the town’s wealthier women to live a lifestyle in seclusion and purity, in line with widespread Islamic coastal beliefs (Donley-Reid Reference Donley-Reid1990; Horton & Middleton Reference Horton and Middleton2000, 183). In more recent ethnographic work, pottery production has been associated with marginalized people and considered ‘dirty’ work (Wynne-Jones & Mapunda Reference Wynne-Jones and Mapunda2008). Because of such associations, pottery production could also have been seen as an opportunity for immigrant women (dependent or otherwise) to fill a niche, especially in Tumbatu where clay or finished pots may have been traded from Mkokotoni or its surroundings. While we have little historical evidence for the role of slaves during the medieval period, the use of slaves in craft production has been demonstrated through early Portuguese texts that describe Pokomo smiths of slave origin in Siyu (Vernet Reference Vernet, Mirzai, Montana and Lovejoy2009, 50). The association of outlier pottery types with the bead workshop in Mkokotoni is intriguing and could suggest a relationship between migrants and bead-production technology.

Another artefact that raises questions about cultural identity is the discovery of a ceramic lip or ear plug in the workshop contexts in Mkokotoni. Similar ceramic plugs have been recovered elsewhere, including Kilwa in southern Tanzania (Chittick Reference Chittick1974, 426), Shanga in Kenya (Horton Reference Horton1996, 335) and Bandarikuu and Kaliwa in Pemba (Fleisher Reference Fleisher2003, 314, 325), but they seem to have been rare. Possible lip/ear plugs made from aragonite were recovered from Manda (Chittick Reference Chittick1984, 196) and Shanga (Horton Reference Horton1996, 335). Such plugs do not seem to have been part of the common coastal style. The Portuguese traveller Duarte Barbosa, however, writing in the early sixteenth century, described lip plugs being used by people neighbouring the Swahili on the Mozambican coast (Seligman Reference Seligman2015). Lip plugs have been in use by groups such as the Macua in Mozambique and the Makonde in southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique (Pawlowicz & LaViolette Reference Pawlowicz, LaViolette, Schmidt and Mrozowski2013; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Duarte and Duarte2018, 449; Seligman Reference Seligman2015). Additional Portuguese sources describe how the Portuguese obtained enslaved people from Mozambique, especially the Macua, during the sixteenth century, suggesting an existing trade in people from this area at that time (Vernet Reference Vernet, Mirzai, Montana and Lovejoy2009). Enslaved people living in Zanzibar before the sixteenth century may well also have come from this area. The lip or ear plug is a small trace of a cultural style originating outside of the Swahili coast.

The pottery from Tumbatu and Mkokotoni also provides insights about choice. Migrants who had settled in these towns may have wanted to keep something from their own cultures and homelands, by producing pots that did not fit into the wider practices and aesthetics of the coast at the time. They may also have been excluded from traditional learning networks, especially if these were based around family units and kinship; slave status in African societies is often associated with lack of kinship (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy2012, 13). While pots are only one of many items used in everyday practices, and cannot give a full picture of agency, livelihoods and social interaction for immigrants to Swahili towns, they are still important and polysemic artefacts that carry meaning beyond their practical function. The process of production and the choice of decoration, form, finish, use and display may have carried cultural, religious, or ritual meaning for the potters and their users (David et al. Reference David, Sterner and Gavua1988; Fleisher Reference Fleisher2010; Gosselain Reference Gosselain1999). They may also have been mnemonic devices, harbouring memories of home, family and belonging (Ashley & Grillo Reference Ashley and Grillo2015, 467). These pots may also have been used in different practices around ritual feasting or food consumption, supporting a diet that differed from that of the other coastal residents.

Interpreting Swahili coast pottery and migration: possibilities and future directions

The possibility of immigrant potters has previously been raised by Mark Horton in his study of Shanga, a settlement in Lamu, Kenya, occupied between the eighth and early fifteenth centuries ce (Horton Reference Horton1996). Horton identified pottery with a wavy line comb motif, which does not fit the other local styles, and argued it may be indicative of a pastoralist group living on the island around 1000 ce. Horton and his team even uncovered the tool most likely used to produce this particular motif (Horton Reference Horton1996, 256). Most of the larger archaeological publications from the coast have not dealt with pottery outliers in this way, however. In some of the most comprehensive publications from Kilwa and Manda, such pottery types are simply categorized under ‘miscellaneous’ (Chittick Reference Chittick1974, 332–3; Reference Chittick1984, 142–4), and many of these are represented by only one or two sherds. There is great potential in viewing some of these miscellaneous types as outliers produced by immigrants for their own use, and I argue they merit further attention in the future. The fact that outlier pottery types are few in number strengthen their association with immigrant people, as large quantities would instead suggest large-scale adoption/exchange by the main population or transfer of styles into local pottery production.

Many scholars of the coast have recognized the variability in ceramic assemblages and regional differences between different pottery types, and used pottery typologies to understand connections between coast, hinterland and the interior of East Africa (e.g. Chami Reference Chami1998; Pawlowicz Reference Pawlowicz2013; Robertshaw & Duncan Reference Robertshaw, Duncan and Cameron2008; Walz Reference Walz2010; Wynne-Jones Reference Wynne-Jones2005). Migration itself has rarely been a topic in such studies, however, and the role of pottery variability has not been linked to differences in pottery producers in this way. The sample of outlier pottery types from Tumbatu and Mkokotoni is small, but it does allow us to ask new questions of the assemblages from coastal sites: what should we do with pots that do not quite fit our typologies? And what do we mean when we use terms like ‘local’ and ‘imported’ pottery in our research and publications? For many archaeologists working on the coast, myself included, it has been common to split pottery types and analysis into local and imported pottery, the separation often made based on fabric type and presence or absence of glaze. But there can be much variability within the local pottery types, and typologies often generously accommodate variability to the extent that it can be difficult to determine which types might not belong. This has been noted by several archaeologists already: ‘In practice, newly found or analysed artefacts get pigeonholed into recognised types and ceramics that fail to match existing categories, (….) are often described tangentially or simply ignored’ (Ashley & Grillo Reference Ashley and Grillo2015, 465). Researchers have also noted the degree of similarity in fabric types, form and decoration over large geographical distances and between different social/ethnic groups (Horton Reference Horton1996, 243; M’Mbogori Reference M’Mbogori2013, 4), which is partially explained by interaction between population groups or by the shared origins of such groups. While coastal typologies can be highly useful, their generous flexibility might also pose obstacles to the nuance of migration and networks between regions. For example, Horton compares his wavy line pottery to others found at ‘sites in the East African coastal hinterland where it is generally thought to be associated with pastoralist locations’ and calls the wavy line pottery ‘intrusive’ (Horton Reference Horton1996, 256, 401). But despite his recognition of this intrusion, Horton includes this type in the broader Tana tradition described for the Shanga archaeological site. This inclusion has the unfortunate consequence of obscuring the presence of different cultural or social groups, by treating all ceramics from Shanga as part of a ‘single broad group, spanning the entire occupation of the site’ (Horton Reference Horton1996, 243). While Horton’s interpretation of Shanga is that of a multi-ethnic community, it is unclear why this is not reflected more clearly in his ceramic typology.

The current study is preliminary, and is limited by small sample size, lack of comparative data with other coastal pottery assemblages and their production, and the dearth of evidence for slavery and forced migration. These issues can be addressed in future research, focusing specifically on comparing Swahili pottery assemblages more broadly, analysing their geographic and temporal distributions and interrogating the structures of pottery production and trade on the coast. The use of petrographic, mineralogical and chemical analysis may reveal details about the chaîne opératoire of Swahili pottery, including the raw materials used and their sources, as well as food and drink residues. These methods have, to date, rarely been used on ceramics in East Africa, despite their significant potential to let us go beyond morphological studies (Ashley & Grillo Reference Ashley and Grillo2015; Namunaba et al. Reference Namunaba, Wandibba and Wahome2022), and studies of different coastal pottery on the macro-scale would prove extremely useful. Many questions remain to be answered: Where did people source their clay? Were pots traded over short or long distances? Were they produced by a small number of specialists, or by every household? How did change in decoration and form occur, and how did trade networks impact such changes? With this current study I argue that paying greater attention to the variability within pottery assemblages on the coast can reveal traces of migration that may previously have gone unnoticed. When we consider the multi-cultural nature of many Swahili towns, it seems prudent to understand some pottery variability within the framework of migration.

Summary and final remarks

In this study I have emphasized how we might understand pottery variation as signs of direct migration of female potters, rather than as the remains of more ambiguous culture contact and diffusion of styles. Female potters might have arrived to the Swahili coast from interior regions in Mozambique, Tanzania, or Kenya as slaves or other dependents to work in domestic, productive, or agricultural contexts, or as voluntary migrants seeking new opportunities in an urban environment. Their association with pottery production could be related to low or marginal status, as seen from more recent ethnographic work in coastal East Africa. Their reasons for creating outlier pots that did not fit the broader cultural style of the coast may be varied and could be connected to their status as outsiders who were not given access to local production techniques. However, this seems unlikely, as they would have relied on local potters to find clay sources and may also have participated in communal firing. It is possible instead that migrant potters in Tumbatu and Mkokotoni produced pots both for their own use and for trade to other inhabitants, customizing their style to the intended user. Some of these pots may have acted as mnemonic devices, a little piece of home in a strange land; allowed the person to engage in specific culinary practices; carried ritual or religious significance; or been part of a sub-conscious, embodied way of making. Significantly, they might be one of few material remains of the forced migration of people who entered Swahili society in slavery. Without historical texts, we have few opportunities to study the presence of slaves in medieval East Africa and their agency within the urban, Muslim population.

Acknowledgements

The archaeological field work was carried out in collaboration with the Department of Museums and Antiquities in Zanzibar and completed as part of my PhD studies at Uppsala University with funding from the following: National Geographic Young Explorers Grant; Anna Maria Lundins Stipendiefond; Sederholms Utrikes Stipend; Kungliga Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundets Resestipendium; Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis; Sernanders Stipendium; and Knut Stjernas Stipendium. The research for this paper was carried out at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies, University of Bonn. I wish to thank Elizabeth Hicks for her helpful comments, and the two anonymous reviewers for thoughtful feedback on the first draft of this article.