1. Introduction and Motivation

Since Donald Trump’s second inauguration as president of the United States, his administration has attempted to reset US trade relations with its trading partners.Footnote 1 Blurring economicFootnote 2 and non-economic objectives,Footnote 3 the evolving efforts have included higher, discretionary tariffs, heightened customs scrutiny of inputs incorporated in traded products,Footnote 4 removing preferential access for least developed countries,Footnote 5 and removing duty-free entry under various US import programs.Footnote 6 The reset remains volatile, with the Trump administration encouraging partners ‘to buy down’ the tariff rates with, for example, promises to invest in the United States, mirror US measures for economic security alignment, grant more favourable treatment for US products, procure US energy products, or implement new customs rules and enforcement strategies.Footnote 7 Though the United States raised tariff rates beyond its bindings, it has made no effort to consider the renegotiation of tariffs through the institutions and procedures of the World Trade Organization (WTO).Footnote 8 The United States has promised swift retaliation should a partner challenge the United States or collaborate with others to confront the United States.Footnote 9 The actions of the United States fit into the classic case of bullying – the use of unilateral sanctions to impose a state’s will.Footnote 10

All of this may, or may not, fit within a grand narrative constructed by the United States to remake the trading system, to acknowledge the heavier role non-economic issues play in the net policy mix, or to assert that coercive power-oriented diplomacy must govern international trade.Footnote 11 Regardless, within a globalized economy governed by multilateral trade rules, interconnected trade agreements, and complex supply chains, the impact of these tariffs stretches beyond a single government deal, with cascading consequences from trade diversion due to the US tariff strategy. WTO Members face an unprecedented conundrum: how to respond to US demands while protecting their interests in an unequal contest, and, at the same time, maintaining their WTO commitments and preserving the foundational principles to avoid a wholesale unravelling of the system of international commerce on which they depend?

This question motivates our investigation into whether a heterogeneous group of economies with varying interests should nevertheless draw upon the mutual benefits they gain from the multilateral system to respond collectively to certain issues. Some governments have emphasized defensive trade diversification measures through enhanced strategic partnershipsFootnote 12 or the negotiation of trade agreements with other partners.Footnote 13 Some Members have brought disputes to the WTO.Footnote 14 Some have proceeded with immediate retaliation: for example, Canada’s response to the US tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminium products.Footnote 15

Conspicuous by its absence is a formal effort to mobilize a collective response to the United States’ divide-and-conquer approach, notwithstanding calls to that effect.Footnote 16 Commentators explain this in terms of the adverse incentive structure facing individual states, which militates against the sustained cooperation required for successful collective responses.Footnote 17 Thus, even when faced with a common threat, states tend to prioritize their domestic interests, finding it difficult to foster trust and to organize a collective response.Footnote 18 States would require considerable incentives to act in the collective interest.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, we argue that before evaluating what could influence Members to take collective action, considering the political realities they face, it is worthwhile asking what WTO institutions and legal procedures are available.

Our thesis is that WTO institutions provide recourse for Members to pursue collective action, should they wish to do so. Collective interests are inherent in the spirit of the GATT/WTO architecture, with the history of pragmatic interpretation and implementation of foundational principles providing inspiration and guidance. The article draws on economic theory and revives past contributions to the rules-based multilateral trading system to assess institutional processes that respect the inherent asymmetries of Members and still create a community invested in transparent, reciprocal, non-discriminatory trade. In the concluding section, we return to collective action problems to identify a roadmap for future research.

We use the idea of collective in a broad sense, appreciating that it speaks to integration – a concert or a chorus, a blending of actions that does not distinguish one from another.Footnote 20 We distinguish between collective and coordinated actions (or inactions). For example, Members may bring separate but identical disputes against one respondent Member’s allegedly WTO-inconsistent actions to the WTO. We associate our inquiry with a classic definition of collective security that refers to ‘a system, regional or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and agrees to join in a collective response to threats to, and breaches of, the peace’.Footnote 21 Notwithstanding the rationalist scepticism about the viability of collective action, we root our procedural inquiry in collective interests, as in the advancement of ‘shared interests’ and even a positive connection with the welfare of others through multilateral processes.Footnote 22

In connecting such ideas to the WTO, GATT Article XXV:1 confirms that Members may take joint action to operationalize the Agreement’s norms and principles.Footnote 23 Further, we note the similarity of coalition and collective, as Members may form coalitions through committee deliberation of a specific regulation or build collective responses through joint statement initiatives. Although we acknowledge that the global situation encompasses heterogenous states and complex economic, technological, and geopolitical conditions, we rely on the concept of collective action to focus on shared interests and community convergence to a solution for a discrete situation. Whether considering the development of rules or responses to a situation that impairs the objectives of the multilateral trading system, we acknowledge that each Member acts through specific incentives to participate. Nevertheless, their reciprocal cooperation can foster mutual benefits and expectations that feed into a community-based identity.Footnote 24

The article is organized as follows: Section 2 assesses the heightened relevance of state heterogeneity in terms of size and openness in trade governance. Though collective action is best undertaken by the largest possible group of WTO Members, we consider how smaller economies are most vulnerable to economic coercion, and how their relative size and economic potential power dictate their capacity to retaliate effectively. Put simply, the asymmetry in the global economy, reflected in the heterogeneity of states in terms of size and market power, matters when conceptualizing rules-based trade. Accordingly, Section 2 underscores the stakes for smaller economies within the WTO community.

Section 3 begins by evaluating WTO procedures for renegotiating tariff rates (i.e., modifying or withdrawing concessions in Members’ schedules) under GATT Article XXVIII. Article XXVIII of the GATT 1994 is an efficient rule designed to facilitate the adjustment of schedules.Footnote 25 While all Members have the right to modify or withdraw a concession, there is an inherent presumption that they will abide by WTO procedures. Renegotiation of tariff bindings defined in Article XXVIII operates in tandem with other governing principles, including good faith, reciprocity, and the most-favored-nation (MFN). However, we find limits to the procedures when confronted with the kind of overhaul the United States seeks to accomplish, and inevitably fail many small, open economies that do not fit into identified groupings under Article XXVIII. The United States shows no intention of compensating its trading partners, let alone those with a substantial interest in the sectors affected by the uncertainty and proliferation of tariffs. There is the added element that the United States’ blanket claim to security threatens the transparency of information needed to negotiate or consult with other trading partners. Thus, we argue that the existing renegotiation procedures would inevitably produce an inequitable remedy for most WTO Members.

Thereafter, Section 3 considers recourse to a situation complaint as a WTO-consistent pathway to achieve collective action in a dispute setting. A situation complaint, pursuant to GATT Article XXIII:1(c) and DSU Article 26.2, allows for public, collective negotiation concerning the current inequitable situation created by the United States’ trade actions that would nullify the objectives of a rules-based multilateral trading system. We further distinguish this little-used form of complaint from the more commonly understood violation and non-violation complaints.

No solution is perfect. We acknowledge that situation complaints lack established WTO practice, leaving open the possibility for a muddled solution. Moreover, a panel report must be adopted by consensus, leaving the possibility for a United States block. Yet there is reason to note that the existing Decision of 12 April 1989, which currently guides situation complaints, does not explicitly prohibit collective remedies, which may, at this time, be a legitimate approach to supporting rules-based trade governance. As we emphasize in our conclusion in Section 4, the practical reality is that a sufficiently large coalition will have a greater chance of preserving the WTO system. It is time to strip back procedures that no longer align with contemporary challenges and retain the normative pressures that shaped the GATT.Footnote 26

2. The Economic Case for Collective Action

Heterogeneity of economies based on size and openness has now become a crucial distinction for the governance of the rules-based multilateral trading system. This newfound importance of heterogeneity reflects the emergence of great power rivalry to capture economic rents accruing to new general-purpose technologies.Footnote 27 In addition, this heterogeneity accounts for the associated rise in economic security concerns, due in no small part to the weaponization of interdependence as part of the strategic contest over said rents.Footnote 28

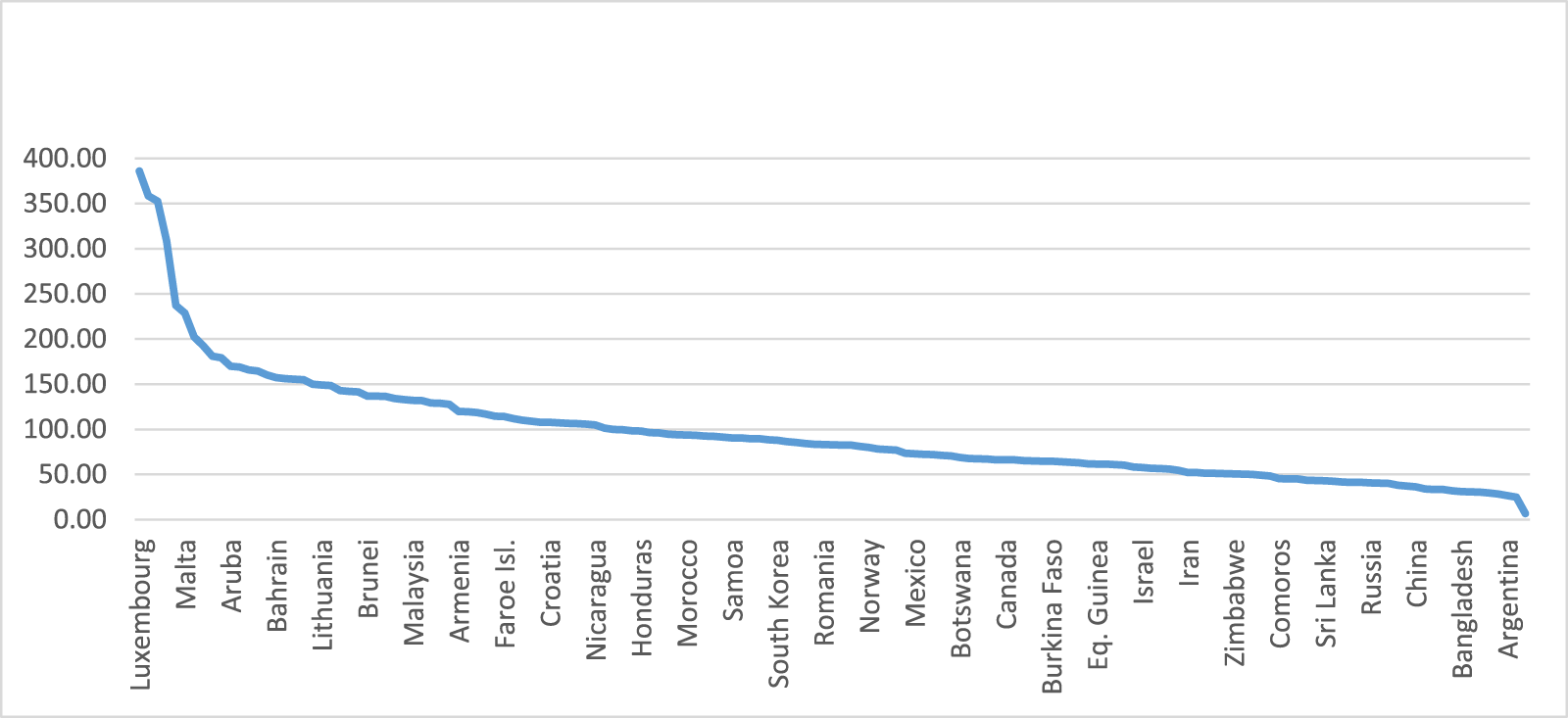

The degree of openness to trade – expressed as the sum of exports plus imports as a share of GDPFootnote 29 – varies widely across the WTO membership (Figure 1), with observations ranging from the 300–400% range for entrepots such as Singapore and Hong Kong to as low as the 20–30% range for large continental economies such as the United States and China, which feature massive internal markets that absorb potential trade before it reaches an international border, and even lower for isolated economies such as Sudan.

Figure 1. Trade openness (exports plus imports as % of GDP), WTO Member economies, 2023.

As a general rule, smaller economies tend to be relatively more open to trade because of their smaller production palette, which makes them more dependent on imports for economic security. Also, because of the smaller size of their domestic markets, they are more dependent on exports for economic efficiency.Footnote 30 More subtly, small open economies tend to have much greater gains from trade,Footnote 31 which makes them vulnerable targets for exploitation through coercionFootnote 32 – they have more to lose and thus more to transfer in a zero-sum exchange. While countries diversify greatly as they grow, as Ricardo Hausmann has shown through his Atlas of Complexity,Footnote 33 even a G7 country, such as Canada, cannot seriously contemplate an approach to economic security based on its own production.Footnote 34

Accordingly, the mechanisms for collective action within the WTO framework may be most valuable for smaller economies, whose size comes into play since the gains from cooperation in collective action relative to the costs of organizing collective action rise as the relative size of the economy falls. As shown in Figure 1, the vast majority of the smaller WTO Members have higher gains from trade than larger Members, such as the United States and China, which can afford to frame policy as if they were effectively closed economies. They are, by the same token, also more dependent on the vitality of the rules-based system and more vulnerable to strategic behaviour based on alleged economic security grounds, to economic coercion, and to divide-and-conquer tactics (selective use of sticks and selective use of carrots to achieve political objectives).Footnote 35

Considering a collective response to the United States’ volatile trade strategies, the larger the group, the louder the choir, and the better the outcome for the participating states in a context where relative economic power determines the division of the gains from trade. Which leads us directly to the question: how do WTO institutions and practices accommodate and facilitate such collective action?

3. Grounding Collective Action in Law

Section 3 makes two contributions. First, section 3.1 argues that the normal recourse to negotiations and consultations concerning the modification or withdrawal of concessions would be an unlikely solution for the United States’ interests in taking back all, or a significant part, of its bound rate concessions. Article XXVIII procedures are effective when one Member seeks to provide quid pro quo for modifying or withdrawing concessions. It can accommodate the threat of retaliation, but it does not offer this counterweight to all Members – only to defined groups.

While the United States could utilize Article XXVIII procedures to overhaul its tariff bindings, evaluating these procedures leads us to conclude that implementing this process would only produce inequitable outcomes in our current context. GATT Article XXVIII procedures result in the exclusion of some Members. Though Members are left with alternatives to renegotiation, including making complaints, implementing safeguards, or using trade remedies, none afford united responses to the United States’ unilateral actions. Although implementation of renegotiation may not help all Members protect their interests in today’s unequal conundrum, the principles of mutual gains and reciprocity can guide collective responses.

Our second contribution is procedural. In Section 3.2, we design a pathway for Members with shared interests to work together through a situation complaint to challenge a complex situation of economic uncertainty and volatility. This approach creates legal distance between the situation assessment and a remedy that seeks to prompt a respondent Member to comply with its WTO commitments. We draw on historical practice to flesh out the contours of a situation complaint that could foster means to mitigate harm caused by a complex set of circumstances, enabling a group of Members to protect their interests while concurrently upholding WTO principles. Indeed, we speculate that a situation complaint could have been an appropriate pathway for the United States in addressing its accumulating trade deficit concerns. For those who wish to move straight to the proposal for a situation complaint brought in response to the chain reaction of global economic uncertainty initiated with the United States’ 2025 measures, see Section 3.2.4.

3.1 Evaluating Multilateral Renegotiation Procedures

One of the defining features of the postwar trading system was the decision to negotiate in periodic rounds to lower tariff rates over time – a feature that distinguishes tariffs from quantitative restrictions. Article XXVIII of the GATT addresses situations in which Members must raise tariffs, requiring that such actions occur within a renegotiation process to balance the competitive conditions between Members. Members aspire to negotiate rather than take unilateral action, and they all agree to this approach, based on principles of reciprocity and non-discrimination. Withdrawal of concessions (or the threat of withdrawal) is possible, but, as detailed below, the procedure is calibrated to negotiation over unilateral action. However, Article XXVIII does not involve a multilateral negotiation, such that many WTO Members may not be included in the renegotiation under Article XXVIII. Deciding which parties are included in a particular renegotiation depends on interpretation and diplomacy, as there are no clear boundaries regarding which Members would have a ‘substantial’ interest in the changes in the context of today’s geopolitical and highly interdependent global markets.Footnote 36 Let us first begin by outlining the procedure of Article XXVIII before turning to the defined parties that may use it.

3.1.1 Types of Article XXVIII Renegotiations

Article XXVIII procedures have undergone significant changes over time, with the addition of new procedures and interpretive notes in the GATT period.Footnote 37 Trading partners that use tariff renegotiation procedures have sought to improve them by clarifying the eligible parties and the timelines that shape various routes to renegotiating tariff concessions, beginning with the initial period negotiated when the GATT was first signed as a provisional agreement in 1947.Footnote 38

Each renegotiation throughout the GATT period was case-dependent. For example, Brazil comprehensively renegotiated its entire schedule in 1956 to redress the ‘obsolete nomenclature’ and change the specific rates that failed to provide ‘reasonable’ protection.Footnote 39 Other times, renegotiation could lead to informal agreements, tariff rate quotas, safeguards, or new schedules.Footnote 40 The early GATT experience depended on governments finding a way to negotiate and avoid the unilateral withdrawal of obligations, thereby sustaining the balance of reciprocity between trading partners.Footnote 41 Yet, as Hudec observed, the law was an instrument to exert diplomatic pressure, but only if used when the community itself was confident that they shared the same values and understandings of consensus.Footnote 42

Article XXVIII procedures encompass three types of negotiations, with different time limits prescribed: three-year ‘open season’ renegotiation that occurs in defined time periods (sub-paragraph 1), authorized renegotiation that occurs at any time when examining ‘special circumstances’ (sub-paragraph 4), and reserved renegotiations (which have no time limits), if the applicant Member elects to reserve the right to renegotiate before the end of the three-year period introduced in paragraph 1 (sub-paragraph 5).Footnote 43 Per GATT Article XXIV, another negotiation can occur that is an exception to MFN, as Members can negotiate preferential trade arrangements on a regional basis or through a customs union – with a key commitment being that these smaller groupings liberalize ‘substantially all the trade’ between them.Footnote 44

A central requirement of GATT Articles XXVIII:2 and XXVIII bis is that negotiations are held on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis. Renegotiation for the withdrawal and modification of tariff bindings aims to achieve mutually advantageous arrangements, requiring reciprocal reductions in tariff bindings (a ‘balance of concessions’).Footnote 45 All tariff concessions, including those modified or withdrawn, must be extended to all other Members on a non-discriminatory basis.Footnote 46 Hence, all Members have an ‘effective opportunity’ to benefit from mutual contractual preferences.Footnote 47 The Appellate Body Report in EC–Poultry, cautioned against using the Article XXVIII procedures to create preferential treatment and afford a ‘loophole’ in the multilateral trading system.Footnote 48

In economic theory terms, Kyle Bagwell and Robert Staiger described the function of reciprocity and multilateral participation as aiming to help ‘weaker’ Members avoid ‘exploitation’ to ‘mitigate the influence of power asymmetries on negotiated outcomes’ by guiding governments toward a ‘political optimum’.Footnote 49 The exchange of concessions establishes equilibrium, for trading partners only take on the risks accompanying trade liberalization if they know their main trading partners are undertaking comparable risks.Footnote 50

3.1.2 Defining the Parties in Article XXVIII Procedures

Negotiations regarding the modification or withdrawal of tariff concessions are conducted with carefully defined categories of Members: first, Members that hold ‘initial negotiating rights’ (or INRs); second, any Member that it considers has a ‘principal supplying interest’ in the changes.Footnote 51 Paragraph 14 of Note Ad Article XXVIII defines ‘principal supplying interest’ as those Members that have had, over the course of a ‘reasonable period of time prior to the negotiations [last three-year period], ‘a larger share in the market of the applicant [Member]’.Footnote 52

Applicant Members must additionally consult with Members that have a ‘substantial interest’ in the tariff changes – such as those that have reasonable expectations concerning the relevant market, or those where the modified concession would affect a major part of that Member’s total exports.Footnote 53 There is no formal definition of ‘substantial interest’ found in Article XXVIII of GATT 1994.Footnote 54 Indeed, the Interpretive Note accompanying Article XXVIII confirms this.Footnote 55 In committee discussions and dispute settlement panel reports, most refer to a general acceptance of a 10% import share benchmark to determine ‘substantial interest’ for ‘methodological ease and consistency’.Footnote 56 However, as there is no precise formula, it is unclear whether the definition of a substantial supplier can account for economic security in markets or other non-economic features.

For developing economy Members, the concept of non-reciprocity was embodied in Article XXXVI:8 (effective 27 June 1966), with an interpretive note confirming its application to GATT Article XXVIII.Footnote 57 The renegotiation of concessions for establishing particular industries, of interest to developing economies, is outlined separately. Paragraph 7 of Article XVIII confirms that certain Members can modify or withdraw concessions to promote industries ‘with a view to raising the general standard of living of [their] people’.Footnote 58 However, to do so, these Members must negotiate with those Members that have INRs or ‘substantial interest’ in the concession, requiring ‘agreement’ on ‘compensatory adjustments’. Without agreement, the General Council would assess the adequacy of the agreement and determine whether reasonable efforts were made to offer compensation. If the Council finds this is the case, then the applicant Member may proceed to modify or withdraw, and other affected Members are free to modify or withdraw substantially equivalent concessions. A 2023 Secretariat report confirmed the process had not been invoked by developing country Members.Footnote 59

3.1.3 Retaliation and Rebalancing in Tariff Renegotiations

Although Members commit to good faith efforts to negotiate and consult with defined parties, the right to change tariffs is absolute and not dependent on an agreement being reached.Footnote 60 As such, the applicant Member seeking to make a change is free to implement the proposed changes. To counterbalance this right, the defined trading partners have corresponding rights to withdraw ‘substantially equivalent concessions initially negotiated’.Footnote 61 Retaliatory withdrawal is not a product of negotiation; it is the process initiated when the relevant Members cannot agree on compensation. However, the ‘price’ for non-agreement is set to substantially equivalent concessions initially negotiated.Footnote 62 Any compensation or withdrawal of concessions must comply with the non-discrimination principle.Footnote 63

Article XXVIII:3 does not require the defined trading partner to seek permission or multilateral authorization to withdraw concessions, mirroring the fact that the applicant does not seek permission for the modification or withdrawal from impacted trading partners. The procedures facilitate adjustment with ‘compensatory concessions to affected trading partners’.Footnote 64 That said, two timelines condition the retaliation process: the withdrawal must take place within six months of the initial change to the concession (extension is available), and the retaliating partner must allow for a 30-day period after negotiation.Footnote 65

During the GATT period, the retaliatory withdrawal of concessions in renegotiations was rare.Footnote 66 Anwarul Hoda concluded the limited use of retaliation, as set out in Article XXVIII:3, was due to the ‘desire to avoid a chain of retaliatory withdrawals by other trading partners affected by the initial withdrawal’.Footnote 67 The drafting history of Article XXVIII has suggested that there was careful consideration of the non-discriminatory retaliation action (withdrawal to adjust the balance) against the nullification and impairment clause (suspension of concessions) in the GATT.Footnote 68 Consideration of a ‘negotiation in reverse’ arose during the drafting of the procedures.Footnote 69 Any other trading partner impacted by a counteraction (the withdrawal of equivalent concessions) against the initial change could bring a dispute and claim nullification or impairment of benefits. As such, Article XXVIII:3 was not meant to create ‘widening ripples’ from the initial tariff change/retaliation outcome.Footnote 70

Article XXVIII:3 retaliatory withdrawal of concessions can occur under two circumstances. First, when the trading partners cannot reach an agreement concerning the tariff change and the applicant ‘freely’ modifies or withdraws concessions, then the ‘principal supplying interest’ partner and the ‘substantial interest’ partner may retaliate – that is, to ‘withdraw … substantially equivalent concessions initially negotiated with the applicant [Member]’.Footnote 71 Second, when a defined party with ‘a substantial interest is not satisfied’ with the agreement made, that party may retaliate by withdrawing ‘substantially equivalent concessions initially negotiated with the applicant [Member]’.Footnote 72

As mentioned, retaliation must occur within six months of the initial tariff change; however, relevant parties may extend this deadline. Members can reserve their rights to invoke sub-paragraph 3 to accommodate further (re)negotiation and consultation (pursuant to paragraphs 1, 2, and 5) to address the tighter six-month timeline.Footnote 73 A recent example concerning the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union demonstrates that the procedures under Article XXVIII:3 can be on hold, while concurrently negotiating and consulting under Article XXVIII:1, 2, and 5 – so far, the EU has extended the timelines on eight occasions, the latest publicly available extension was to July 1, 2025, to allow Members to finalise ongoing negotiations.Footnote 74

Article XXVIII:3 is a rare occurrence where countermeasures are foreseen within the GATT architecture. However, the rules do not specify an approach to calculate equivalence. Note also that the phrase ‘substantively equivalent concessions’ is different from consideration of retaliation in the context of ‘nullification or impairment’ of benefits per GATT Article XXIII. Note 6 of Ad Article XXVIII:1 suggests that equivalence takes into consideration ‘the conditions of trade at the time of the proposed withdrawal or modification’. In 1947, when drafting, the idea was that equivalence ‘would be determined in the light of what the party concerned had paid for the concession which had been withdrawn’.Footnote 75

In 1978, a GATT panel circulated its report concerning a dispute between Canada and the European Communities, following Canada’s withdrawal of concessions on various products due to dissatisfaction with the EC’s offer for an agreement on changing zinc duties from specific to ad valorem rates.Footnote 76 The EC asserted that Canada’s withdrawal was inconsistent with the GATT. The panel disagreed but did not make a quantitative assessment. Instead, the panel found that the withdrawal ‘should have been less than the equivalent of the total export volume of zinc to the Community as account should have been taken of the rebinding of the Community duty’.Footnote 77 Accordingly, the panel noted that the withdrawal must match the ‘actual damage suffered by Canada’ and, consequently, ‘should have been based on the difference between the ad valorem equivalent of the specific rate calculated on imports from Canada only and the new ad valorem rate’.Footnote 78

In a 1988 Council meeting, a discussion ensued regarding the level of retaliation following the United States’ non-compliance with the Superfund panel’s recommendations concerning petroleum taxes, which were found to be inconsistent with GATT Article III:2.Footnote 79 The Director-General’s Legal Advisor attempted to clarify the principles for calculating ‘appropriate’ retaliatory measures under GATT Article XXIII compared to the withdrawal of tariff concessions under Article XXVIII. The Legal Advisor noted criteria for the withdrawal of concessions included: the amount of imports before the three-year renegotiation period, including the development ‘trend’, the ‘size of the tariff increase being negotiated’, and an ‘estimate […] of the price elasticity’ for the product.Footnote 80 In 1991, the GATT Secretariat further clarified that tariff negotiations require a ‘focal point’ for compromise, which is typically the ‘relative magnitude of trade flows and the associated tariffs’.Footnote 81

3.1.4 The United States’ Current Rejection of Multilateral Negotiations

Article XXVIII procedures are far from perfect. They are ‘efficient,’ enabling a renegotiating country to settle with a limited group and move on.Footnote 82 After all, tariff rates are dynamic (distinguishing them from more rigid forms of quantitative restrictions) and expected to change with negotiation. However, the process can also be brutal for those kept outside the negotiation and consultation sphere. Moreover, even if changes are made on a non-discriminatory basis, the ‘compensation’ offered through Article XXVIII procedures may not be of interest to all other Members. Moreover, even those involved in the negotiation may not have an interest in an agreement, yet do not want to close out the negotiations.Footnote 83

For the recent tariff overhaul, the United States has not relied on Article XXVIII procedures. For those Members that could have negotiated or consulted with the United States about the reciprocal tariffs (those that held INRs, had a principal supplying interest, or a substantial interest), the path to renegotiation through Article XXVIII does not exist. Rebalancing against the United States’ increased tariffs could be permissible by imposing trade remedies, such as safeguards per GATT Article XIX and the Agreement on Safeguards, or by seeking remedies in the course of dispute settlement to redress nullification or impairment of benefits, pursuant to GATT Article XXIII.

That said, conventional remedies appear thin. With the United States’ ability to block a dispute settlement panel report, the impacted trading partners could lose their ability to implement any panel report that finds US non-compliance with Article II.Footnote 84 The causation and non-attribution requirements in GATT Article XIX and the Agreement on Safeguards have produced what Alan Sykes dubbed ‘fundamental deficiencies’ that render the rules inutile.Footnote 85

Members could benefit from a procedure that formalizes the middle space between a discrete dispute and new rulemaking. In the next section, we explore a lawful process that could help some Members preserve multilateral procedures (enhancing their individual and collective interests in the rules-based system) while seeking to attenuate the harm caused by a global situation of economic uncertainty. Seeking collective action through a situation complaint does not withdraw other potential complaints or negotiations with specific Members, such as the United States. However, as explained in the next section, a situation complaint could orient towards a discrete situation necessitating a collective response rather than a mutual settlement between two (or sometimes more) disputing parties.

3.2 Bringing Situation Complaints

The Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU) establishes an exclusive forum for Members to seek redress and confirms that Members should not ‘take justice into their own hands’.Footnote 86 Trade commentators have theorized that the DSU presents a legalization of the GATT system, primarily ‘designed to constrain unilateral punishments’.Footnote 87

More than one Member can pursue dispute settlement proceedings against a single respondent Member regarding the same matter (Article 9 of the DSU sets out the procedures for doing so). When a Member seeks recourse to WTO dispute settlement to redress another Member’s violation of its WTO obligations, a panel will determine if the measure is inconsistent with the relevant covered agreements and shall make findings to assist the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) in making recommendations and rulings in the dispute (per Article 11 of the DSU). In the absence of a mutual settlement, Articles 3.7 and 22.1 of the DSU confirm that the first remedy is the withdrawal of measures found to be inconsistent with WTO obligations. A violation complaint is therefore only effective if the respondent Member accepts the DSB recommendations and rulings.

While complainants could demonstrate the existence of a violation, there remains a risk that the United States would appeal the panel report into the void to prevent DSB adoption.Footnote 88 While the United States may seek to justify its allegedly inconsistent actions, the shortcomings of a violation complaint are that the United States has tended, especially in the past, to justify its trade restrictions within a broader framework of economic security, arguing that its actions are based on self-judged security interests, which it claims are non-reviewable by WTO panels.Footnote 89 With the power to appeal dispute settlement panel reports deemed counter to US interests into ‘the void’, the dispute settlement system cannot effectively police the abuse of measures or afford oversight over compliance with recommendations made.Footnote 90

Bringing non-violation complaints presents a similar problem for blocking the implementation of panel reports. Yet, non-violation complaints begin with a crucial presumption that there is no need for a rigorous assessment of whether the United States breached its tariff bindings. Due to past practice, winning a non-violation complaint would be challenging – unless Members agreed to a novel mechanism specifically designed for the United States.Footnote 91 The shift to a liability rule for non-violation complaints could prioritize rebalancing through compensation with the complainants.Footnote 92 This could, in turn, render other WTO rebalancing procedures obsolete, such as safeguards under Article XIX and renegotiation of concessions under Article XXVIII.Footnote 93 More importantly, there is a deeper question regarding the desirability of a multilateral trading system that does not hinge on accepted norms of transparency, reciprocity, equity, and non-discrimination, but rather one shaped by who holds asymmetric leverage over other Members.

In contrast, a situation complaint does not hinge on a Member’s non-compliance with its WTO commitments. As elaborated below, a situation complaint pursuant to GATT Article XXIII:1(c) could foster a public, collective response for impacted Members. We draw upon GATT practice to underscore that pursuing collective enforcement is not unprecedented – the text maintains the opportunity to design an efficient and equitable mechanism for governments that lack the economic and political power to pursue a complaint alone.

Briefly, when negotiating the GATT in 1947, situation complaints emerged as the multilateral trading system would comprise the International Trade Organization (ITO) legal framework (which was left stillborn by 1950) and the diplomatic ‘atmosphere’ of the GATT.Footnote 94 Situation complaints were initially understood to address exogenous events that could lead to circumstances where a Member might not meet its obligations.Footnote 95 The complaint underscored that the rules-based multilateral trading system would depend on a healthy global economy.Footnote 96 The Australian negotiators, who were instrumental in designing non-violation complaints, also offered examples of the circumstances contemplated for bringing situation complaints: a ‘world-wide collapse of demands’ or events where ‘a shortage of a particular currency places us all in balance-of-payment difficulties’ (emphasis added).Footnote 97 A related scope emerged out of concern for those circumstances when a country faced ‘devastating effects’ but was unable to gain multilateral authorization to escape its multilateral trade commitments.Footnote 98

Petros Mavroidis has remarked that situation complaints ‘could be the means to eventually respond cooperatively to a crisis, and thus mitigate its negative implications’.Footnote 99 As such, recourse to a community-driven coalition to ‘prevent disequilibrium in world trade and payments’ could potentially fall within the scope of a situation complaint.Footnote 100 Situation complaints could be the WTO version of retorsion, affording breathing space for necessary political actions.Footnote 101 Thus, situation complaints would offer ‘opportunity [for a government] to state its case to the international community and have its obligations reviewed with full international approval’.Footnote 102 The appropriate remedy for situation complaints was left open, ‘as may be appropriate in the circumstances’.Footnote 103 We turn next to Uruguay’s presentation of a situation complaint. Though upon review, the theory and approach to situation complaints remained unfulfilled, the experience remains critical to our discussion for demonstrating how the principle of equitableness underscored the desired use of situation complaints.

3.2.1 Uruguay’s Complaint

There are a few past examples of situation complaints.Footnote 104 One example is from 1962, when Uruguay charged 15 other economies with the non-fulfillment of their obligations and expressed general concern over the ‘present situation of imbalance’.Footnote 105 Ambassador Julio Lacarte, speaking for Uruguay, methodically laid out a list of hundreds of restrictive and discriminatory measures undertaken by 19 GATT Contracting Parties that closed markets for Uruguayan agricultural products, creating balance of payments difficulties.Footnote 106 The delegation identified the ‘serious prejudicial effects’ of the restrictions and the nullification and impairment of benefits that Uruguay should have accrued.Footnote 107 Lacarte highlighted Uruguay’s situation but linked this to the shared experience of primary producer countries, urging further consideration of GATT procedures and rules.Footnote 108 Perhaps for this reason, Uruguay repeatedly emphasized the need to reevaluate a more extensive, imbalanced situation. Finding difficulty with bilateral diplomatic exchanges achieving results, it was time for action, Lacarte explained, for a ‘situation of supplying countries of foodstuffs and primary commodities, having regard to the disequilibrium from which they suffer’.Footnote 109 Uruguay sought ‘equitable solutions reached in an atmosphere of equanimity’.Footnote 110 Uruguay urged the other governments to take formal steps towards its request to improve the present situation.Footnote 111

Over the course of several years, Uruguay presented requests for review and recommendations. A convened GATT panel reported on Uruguay’s recourse to Article XXIII in the twelfth session of the Contracting Parties.Footnote 112 Throughout the several rounds of review and assessment per country, the panel emphasized that Uruguay had not properly connected nullification or impairment to benefits accruing to Uruguay ‘under the General Agreement’.Footnote 113 The panel acknowledged Uruguay’s request to review the situation, even beyond questions of GATT consistency. However, it emphasized an obligation to present significant factual evidence to demonstrate the circumstances.Footnote 114 To show the situation was ‘serious enough’, the panel concluded that a Contracting Party must ‘demonstrate the grounds and reasons’ with ‘[d]etailed submissions’ to make a prima facie case of nullification or impairment.Footnote 115 Overlooking the ‘situation dimension’, the panel acknowledged Uruguay’s request to assess these restrictions as ‘broader issues’ concerning the GATT, but only offered recommendations for the individual trade restrictions listed by Uruguay.Footnote 116No precise description of ‘other situation’ arose in the filings studied, leaving it unclear how a panel’s role might change in that context.

Several panel reports were issued to evaluate the restrictive measures raised by Uruguay.Footnote 117 Uruguay continued careful documentation and consultations with other Contracting Parties concerning compliance with the panel’s recommendations. Like the earlier findings, the panel (of the same composition each time) concluded that Uruguay offered detailed lists of alleged trade barriers but did not provide sufficient ‘grounds’ for using the GATT’s nullification or impairment procedures; consequently, it found Uruguay failed to provide a basis for further discussions or the invocation of GATT Article XXIII.Footnote 118

Uruguay struggled to build a case for remedial action. Robert Hudec later observed that Uruguay’s attempts to make the GATT act as prosecutor had failed.Footnote 119 If Uruguay believed it was ‘getting less than it was giving’ (as Hudec explained), then the situation complaint, which seemed designed to permit Uruguay to give less owing to global pressures, was not the right form of complaint.Footnote 120 While Uruguay’s efforts highlighted many trade barriers, no countermeasures were proposed, and, if anything, the legal consequence remained a fuzzy commitment to satisfactory adjustment. The episode revealed Uruguay’s concerns but failed to elucidate a legal framework for redressing situation complaints.

3.2.2 Revisiting a Joint Proposal for Collective Action

Brazil saw Uruguay’s complaint as a test case for agriculture export economies in GATT dispute settlement.Footnote 121 To Brazil and Uruguay, it was clear that industrialized, developed economies had more bargaining power to protect domestic production and defy the GATT legal system.Footnote 122 Within the Committee on Trade and Development, Brazil and Uruguay authored a joint proposal to strengthen Article XXIII procedures for developing GATT Contracting Parties.Footnote 123 Brazil explained its motivation to build up the GATT Article XXIII procedures to make them more effective for developing economies.Footnote 124

The proposal to renegotiate GATT Article XXIII contained several divisive issues for the ad hoc working group within the Committee, including the proposal for collective action:

Without prejudice to the provisions of the preceding paragraph, in the event that a recommendation by the CONTRACTING PARTIES is not applied within the prescribed time limit of … months, the CONTRACTING PARTIES shall decide what collective measures shall be taken to ensure compliance with the Agreement.Footnote 125

Collective action was not the only controversial proposal to strengthen dispute settlement. Alongside this proposal was the possibility of remedial measures, pending review of allegedly GATT-incompliant measures taken by developed economies, and a proposal to automatically release developing economies from their GATT obligations when ‘seriously’ impaired by developed economies’ measures, like the GATT Article XIX procedures for protecting domestic producers.Footnote 126 Uruguay urged attention to ‘constructive remedies’ where measures affected the ‘essential interests’ of less-developed Contracting Parties.Footnote 127

The ad hoc group working on the legal amendments for GATT Article XXIII was divided on the scope and meaning of ‘collective measures’ to induce GATT compliance.Footnote 128 Some challenged the proposal, citing it as violating the ‘spirit’ of the GATT.Footnote 129 Others protested that the renegotiation of Article XXIII would ‘undermine’ the existing conciliatory approach.Footnote 130 But for Brazil, collective action was a necessity. The Brazilian representative countered by asking: Was non-compliance not as harmful to the GATT spirit?Footnote 131 The reality was that developed economies would not withdraw GATT-inconsistent measures willingly, and a single developing economy lacked the economic power to induce compliance – any retaliation would feel like a ‘mosquito bite’.Footnote 132 Collective action was necessary to impose ‘moral sanctions’ when individual parties ‘flouted decisions’ by the GATT Contracting Parties.Footnote 133 The push for collective action was part of a deeper problem concerning equality among GATT Contracting Parties.Footnote 134

When it came to explaining what ‘collective action’ entailed, Brazil and Uruguay had no clear answer. When asked whether it implied boycotts, the sponsors explained they did not anticipate a boycott as the answer.Footnote 135 Other delegates raised concerns that the vagueness of collective action would not allow governments to know ‘beforehand’ what measures were applicable.Footnote 136 There was no need to define the types of action; the GATT Contracting Parties must decide in the context of each dispute.Footnote 137 This was about inequality. Developing economies could see consultations with allegedly wrongdoer economies drag on, with the wrongdoer free to participate in GATT decision-making, including actions concerning the balance of payments concerns of developing economies.Footnote 138 Concurrent efforts to negotiate new provisions respecting trade and development in Part IV of the GATT would not address these problems respecting dispute settlement.Footnote 139

Brazil and Uruguay explained that Article XXV:1 of the GATT was their reference point for joint action.Footnote 140 They proposed that the ad hoc group closely examine this provision to provide clearer guidance on collective action.Footnote 141 The WTO archived records show no further discussion of collective action or joint action under Article XXV, as within the Committee for Trade and Development or the ad hoc group. Article XXV commits the Contracting Parties to giving effect to provisions that ‘involve joint action … with a view to facilitating the operation and furthering the objectives of [the GATT]’. Most experts are likely familiar with Article XXV:5, which grants waiver powers to the GATT Contracting Parties. Little is known about the scope for joint action. In a meeting of the GATT Contracting Parties, the Executive Secretary explained that a function of the GATT Contracting Parties was ‘acting jointly under Article XXV, to interpret the Agreement whenever they saw fit’.Footnote 142 Decades later, the United States drew from this understanding to assert the practice of adopting interpretations of the GATT 1947 through joint actions under Article XXV of the GATT 1947, in answering a panel question in United States–Certain Steel and Aluminium Products.Footnote 143

Returning to Uruguay and Brazil’s proposal, a meeting of the ad hoc group for legal amendment to Article XXIII took place in February 1966. However, there are no records of the discussion. The final report from the ad hoc working group for the Committee on Trade and Development indicated the divisive views of the delegations. While noting the inclusion of the text could ‘pressure’ industrialized economies to comply with GATT obligations, others argued the proposal was technically unfeasible.Footnote 144

Brazil and Uruguay continued rewriting provisions to improve GATT Article XXIII.Footnote 145 Inevitably, they compromised with the developed economies and rewrote the provision concerning collective action. The reformulated text left it to the Contracting Parties to ‘consider’ applicable action, remaining silent on the possibility of collective action: ‘In the event that a recommendation to a developed country by the Contracting Parties shall consider what measures, further to those undertaken under paragraph 9, should be taken to resolve the matter’.Footnote 146 The report placed on record that the phrase, ‘shall consider what measures’, was ‘intended to mean that the Contracting Parties shall consider the matter with a view to finding appropriate solution’.Footnote 147 The report indicated that the less-developed economies in the group did not find their ‘fundamental concerns’ were met with the draft text.Footnote 148

In 1965, no one imagined the destruction of the multilateral trading system if developing economies were stuck in political limbo without the power to pressure other GATT Contracting Parties to comply with the trading rules. Yet, collective action was not an impossibility in the GATT. Those economies that depend on open markets, but may be unable to undertake economic security strategies without external assistance, could benefit the most from bringing a joint situation complaint. The lesson for Members today could be to build on the norm of equitable considerations and joint action to promote the least trade-distorting policies that are reasonably available for reconciling and balancing domestic exigencies and international obligations in responding to economic security concerns under the kinds of extenuating circumstances contemplated for a situation complaint.Footnote 149 For example, although one defence against weaponized dependencies is diversification, existing domestic structures could constrain how small open economies develop policies in response to international pressures.Footnote 150 We further explain how Members could pair internal efforts to attenuate harm with collective recourse through a situation complaint in Section 3.2.4.

3.2.3 The European Communities’ Complaint

A second example of a situation complaint is a dispute between the European Communities and Japan in 1983. The EC requested a working party review of Japan’s practices under GATT Article XXIII:2.Footnote 151 The EC did not identify any alleged violations of the GATT by Japan, but instead referred to a grave trade imbalance caused by a ‘difficulty of penetrating the Japanese market’.Footnote 152 The EC argued that Japan’s trade liberalization efforts were ‘not commensurate with the magnitude of the problem’ and demanded ‘a co-ordinated series of general and specific measures’. The EC identified its desired result: ‘a [future] situation … where Japan offers equal opportunities of trade expansion to its trading partners’.Footnote 153 Such a situation would meet the ‘general GATT objective of “reciprocal and mutually advantageous arrangements”,’ the EC explained.Footnote 154

In subsequent GATT council meetings, Japan presented measures undertaken to liberalize its market and reduce internal barriers for foreign products to convince the other Contracting Parties that a formal review was unnecessary.Footnote 155 Though contemporary commentary on the dispute observed that the EC dropped its working party review request, the GATT council records suggest that the EC continued raising its concerns about Japan’s export-led development and use of protectionist measures.Footnote 156 Additionally, Japan remained attentive in reporting liberalization efforts throughout the year.Footnote 157 At the very least, raising the situation complaint highlighted the issue to the GATT community, requiring Japan to engage with the GATT Council, even though the EC never pressed for formal remedies.

3.2.4 Bringing a Situation Complaint

We have already emphasized that the WTO architecture permits Members to take joint action to facilitate the operation of the WTO Agreements.Footnote 158 We begin again with Article XXV:1 to emphasize joint action in bringing a dispute concerning a combination of circumstances that affect the development of a mutually satisfactory solution for the collective complainants, drawing on the initial impetus provided by Brazil and Uruguay’s collective enforcement proposal in the 1960s, as detailed above.

Collectively, Members could bring a situation complaint to the WTO, raising concerns about a global situation of uncertainty concerning trade flows shaped by (though not necessarily exclusively caused by) the United States’ attempt to unilaterally reset its bilateral trade balances. Thus far, bilateral bartering has produced self-declared ‘deals’ for many US trading partners (encompassing aspirational commitments with no legally binding obligations), or newly signed economic security agreements with less developed economies that establish (higher) bound rate concessions in exchange for, among other things, their alignment with US economic security-justified trade restrictions and prohibitions.Footnote 159 All completed deals remain uncertain as to outcomes, locked in a never-ending story of emergency, with the United States even demanding re-evaluation as it sees fit.Footnote 160

In bringing a situation complaint, some Members could clarify that the focus of the complaint is a collective response to a situation of global economic uncertainty. The situation complaint raised would engage individual and collective interests in the perseverance of equitableness, and the sustainability of rules-based trading for all Members. Two approaches are possible for situation complaints. The first is to use the situation complaint to pursue collective retaliation, and the second is to focus on attenuating harm among the joint parties in responding to a global situation. The second approach accords with the spirit of the normative guidance offered by GATT practice, but we will examine both for the sake of completeness.

The first approach would require Members to bring a situation complaint on the basis that the United States failed to use Article XXVIII procedures in modifying or withdrawing its concessions. The joint parties could argue that the United States created a situation of global inequity and instability through its tariff strategy, ignoring WTO procedures. The joint Members could seek a panel ruling on the withdrawal of substantially equivalent concessions from the United States due to the absence of a satisfactory agreement and, to the extent necessary, to reset the equilibrium established by WTO rights and obligations.Footnote 161 Each complainant could be asked to identify a substantial interest in this reset. The joint parties could, on that basis, plausibly assert a collective interest in restoring tariff renegotiation procedures owing to their economic interdependence.Footnote 162 Essentially, the joint parties could seek a determination to restore the rebalancing mechanism regardless of the United States’ efforts to bypass it. Subsequent arbitration could consider the calculation of equivalence, however difficult that would be in the circumstances.

This approach does not compromise the United States’ rights to withdraw or modify any, or even all, of its concessions. However, by asserting (even the threat of) selective withdrawal, the joint complaint signals to the United States that its circumvention of WTO rules will not preclude rebalancing. In this scenario, the United States remains free to use safeguards and other trade remedies and seek justification for all other trade restrictions based on the general and security exceptions in the WTO Agreements.

The second approach focuses on affording an adequate opportunity to develop a mutually satisfactory solution (per DSU Article 11) to the combination of conditions that impact the attainment of the WTO’s objectives. The United States’ 2025 measures would constitute part of the factual circumstances that triggered a situation of global economic instability. However, the situation complaint centers on procedures to facilitate and improve trade conditions among the collective parties. This approach leans into the idea that situation complaints differ from violation and non-violation complaints because they address a problem ‘for which no particular country is responsible’.Footnote 163 The United States could have (and arguably should have) mounted a situation complaint to seek redress for an untenable trade deficit that emerges from hundreds of bilateral surpluses and deficits, rather than attributing it to any specific bilateral relationship(s). Likewise, in response to the growing destabilization of the global economy through a domino effect of increasing bound rate concessions and trade prohibitions and restrictions, Members could bring a situation complaint to seek panel recommendations for inter-collective responses to attenuate harms to themselves and the multilateral system. The panel could set up special procedures for implementing inter-collective responses to the global situation. Such a proposal could be especially useful to the extent that the existing WTO architecture does not explicitly offer guidance on responding to the exceptional circumstances, such as further guidance on support limits on sectoral subsidies or added notifications for financial support of small businesses. There would be no commitment that such procedures would extend beyond the situation complaint. The panel could work with the joint parties to foster procedures for specific safeguards and other safety valves, including discrete forms of managed trade or investment facilitation tailored to attenuate harm to severely affected industries.Footnote 164 We further explore the scope of attenuating harm in Section 3.3.

Now, it bears emphasizing that bringing a situation complaint to pursue attenuating actions might be unnecessary. Members may coordinate in the absence of a formal complaint. For example, given material impacts on their trade and in the absence of a bona fide offer to negotiate or consult, per Article XXVIII procedures, Members could form a working group to discuss a solution. Members could potentially add an agreement from this working group to their scheduled commitments.Footnote 165 Such a course of action does not seek to modify WTO rules or seek to develop a new agreement.Footnote 166 This could create a presumption that failure to comply with WTO negotiation or consultation requirements with one Member is a failure that affects them all. The benefit of bringing a situation complaint, at least for the United States case study, is its incorporation of oversight and accountability mechanisms into an unprecedentedly fluid and chaotic set of circumstances. Recommendations and rulings could evaluate what legal or political actions the joint parties could adopt to respond to the situation under assessment. Therefore, the panel would support these Members in fostering mutually beneficial and equitable solutions (as Ambassador Lacarte urged) when attenuating some or all of the harms created by the situation.

Currently, without WTO practice, it is unclear what role a panel could play in situation proceedings. Though Members may wish to avoid targeting the United States in bringing a situation complaint, they may nevertheless acknowledge certain Member’s contributions to the situation itself. Recall that Uruguay’s complaint addressed the broader GATT failure in not improving Uruguay’s exports of agricultural products, while still identifying specific respondent governments.Footnote 167 There is nothing prohibiting the use of a situation complaint to ‘dramatize’ the failure of the current implementation of procedures to dissect the situation and seek a remedy for it.Footnote 168 Additionally, Members could argue that the situation complaint is of systemic importance since the United States’ pressure upon other Members to deviate from their own WTO commitments in tariff buy-outs could ultimately unravel the system.

The legal operation of a situation complaint is governed by GATT Article XXIII:1(c) and DSU Article 26.2. Together, these provisions clarify that the DSU applies to a situation complaint, up until the point of panel report adoption. The consideration of adoption, surveillance, and implementation of panel rulings and recommendations is governed by the GATT Decision of 12 April 1989 on Improvements to the GATT Dispute Settlement Rules and Procedures.Footnote 169 The 1989 Decision describes ‘prompt compliance’ with panel recommendations and rulings. Though per the second approach, Members need not focus on the United States’ compliance, but rather on addressing their mutual interests through dispute settlement, while defending the collective interest in trade multilateralism. Even if the United States entices one Member to defect from this effort, with a so-called deal, Members could still commit to working with other Members to address the broader situation at hand.

Finally, according to the rules, adopting a panel report concerning a situation complaint would be subject to consensus.Footnote 170 Accordingly, the United States could block the adoption of a panel report. The concern of blocking need not spell disaster for Members bringing a situation complaint. Particularly if seeking the second approach, Members could argue that a situation complaint centers on a united approach to the inequitable equilibrium of the current situation. The focus would be on establishing a targeted, public review of the situation, requiring panel recommendations and rulings on proposed means to attenuate harm while remaining compliant with WTO rules. The parties bringing the situation complaint could argue that the goal is to encourage collective discussion under the guardianship of a panel assessment. Even if the United States were to block a dispute settlement report, Members could informally still build from the panel’s recommendations. Likewise, the United States could challenge how attenuating steps impact its trade benefits. Nevertheless, there is ultimately a powerful signal in a situation complaint. Rather than trying to coerce the United States into compliance with the threat of retaliation, the situation complaint sends a ‘warning shot across the bow’ that abusing WTO commitments does not translate to a remake of the world trading system.Footnote 171

3.3 Attenuating Harm and Countermeasures

We acknowledge the urgency of action while attending to the normative content of WTO law and processes. Collective action may seem a legitimate action in these circumstances, but without explicit procedures, the proposition necessarily exists in a ‘grey zone’ of legality.Footnote 172 Like Schrödinger’s Cat, the Members cannot determine the legality of collective action channelled through a situation complaint until it is tried, or the box is opened to see the fate of the cat. Yet, we close the assessment of law by making one final argument that suggests governments may not be seen as unilaterally resolving WTO disputes by acting collectively. Or, more specifically, it is not collective action that could potentially weaken the multilateral trading system or violate Article 23.1 of the DSU. Rather, it is whether they seek to decide that a violation has occurred without recourse to dispute settlement. We argue that even without the presentation of a situation complaint, collective action that aspires to attenuate harm caused by the United States’ overhaul of its trade concessions remains consistent with WTO obligations. As the concessions are understood to be protected by a liability rule, then measures to attenuate harm (or what the panel described as palliative care) need not defile the WTO legal system.Footnote 173

The Appellate Body has made clear that ‘[s]eeking redress of a violation is not by itself prohibited by Article 23.1’ but to violate the provision, a Member must seek redress ‘without having recourse to, or abiding by, the rules of the DSU’.Footnote 174 Drawing from the dispute settlement panel assessment in EC–Commercial Vessels, the DSU conditions how Members respond to what they consider to be another Member’s violations of the WTO covered agreements.Footnote 175 Remedial actions, per the DSU, refer to actions intended to restore the balance of WTO rights and obligations.Footnote 176 However, the panel found that redress does not encompass actions ‘to compensate or attenuate the harm caused to actors within the aggrieved Member as a result of the allegedly WTO-inconsistent action’.Footnote 177 Actions designed to attenuate harm were distinct from actions taken to induce cessation of the WTO rule violation.Footnote 178 Trade adjustment assistance to workers affected provides an example.Footnote 179 The panel distinguished ‘palliative action’ from the redress in DSU Article 23.1, finding such care would not restore the balance of rights and obligations between Members.Footnote 180 The panel did not circumscribe which approaches to take, leaving the possibility for future consideration of possible retorsions available under international law.Footnote 181

There remains the potential argument to conceive of collective action even beyond the parameters of multilaterally authorized redress: to consider the institution of countermeasures for alleged violations of international and non-WTO norms.Footnote 182 The EU and its Member States have developed domestic instruments to deter and pursue reparations for acts of economic coercion (a concept not defined in WTO law).Footnote 183 Normative questions as to the limits of justifying anti-coercion measures based on WTO or other treaties’ security exceptions remain unanswered and are a subject for future interpretation. The pursuit of collective action does not stand in direct contravention of the European Commission’s redress of economic coercion; however, we posit that a collective front could improve the prospects for settling the matter within an international forum. Both economic theory and international legal theory have emphasized that collaboration among weaker powers helps counteract harms caused by stronger powers.Footnote 184

Beyond doctrinal questions, the International Law Commission’s (ILC’s) codification of countermeasures raises valuable cautions that take us back to Ambassador Lacarte’s warnings about an unduly rigid regime that favours the alleged wrongdoer (the powerful state) to the detriment of weaker, developing states suffering harm.Footnote 185 The experiences of smaller, emerging economies with WTO dispute settlement have exposed inequities and limitations of enforcing rulings.Footnote 186 The Charter of Economic Rights and Duties (1974), an international legal resolution from the UN General Assembly, spoke of a collective rejection of ‘foreign aggression’ and a ‘duty’ to extend assistance to Members impacted by coercive policies.Footnote 187 With careful attention to the public good and the experience of weaker Members prevailing in a dispute, Joost Pauwelyn advocated for collective enforcement to embrace the fact that the WTO is a collective construct.Footnote 188 We liken this to a separate argument made by Petros Mavroidis in the context of WTO remedies, when evaluating actions that try to find the limits of retaliation while ‘preserving the peace for the greater good’ (keeping all WTO Members participating in the system).Footnote 189

To close this section, we can recall Clair Wilcox’s assessment that ITO/GATT dispute settlement aimed to ‘tame retaliation, to discipline it, to keep it within bounds’.Footnote 190 Wilcox, head of the United States’ delegation that negotiated a Charter for the ITO, made clear the multilateral trading system would not outlaw the power to retaliate, but would impose a ‘check’ on its growth and use and would seek ‘to convert [retaliation] from a weapon of economic warfare to an instrument of international order’.Footnote 191 In this light, we could understand the system as setting limits, but not anchoring those limits for all time. If anything, such limits would evolve in response to the specific circumstances at hand. The GATT’s pliable techniques and experimentalism formed a ‘continuous process in which there [was] usually more than one answer in the air at any one time’.Footnote 192

4. Conclusion

This article has considered whether WTO Members can develop a collective response to a situation that is globally welfare-damaging and impacts individual Members differentially. We have set out the procedures for doing so, concluding that collective action remains within the letter and spirit of the WTO Agreements. We were motivated by the United States’ move to redraw its trade relations and break from its international trade commitments through bilateral negotiations in which it holds asymmetric leverage, buttressed by a proactively announced escalation in response to any attempt by counterparties to join in forging a collective response. Our focus has been on establishing the potential for collective action within the WTO architecture. We have highlighted a path forward for counterparties that pre-empts cascading internecine harms from bilateral acquiescence in WTO-inconsistent demands that would otherwise exacerbate the erosion of the mutual benefits generated by the rules-based trading system.

We began with the economic underpinnings, namely that systems characterized by heterogeneity in the size and latent economic power potential of agents (in our case, states) can become sites of strategic contestation. Collective action that resets (or at least partially moves towards) symmetry in power can improve outcomes for the smallest actors, creating gains from cooperation that could lead to a negotiated settlement. Certainly, the larger the coalition capable of pooling interests within the multilateral trading system, the greater the chance for resetting power asymmetry. We highlighted that small open economies have the greatest gains from trade within the trading system relative to the costs of cooperation to reinforce our impetus to sharpen a WTO framework for collective action.

We then evaluated the implementation of the WTO procedures established for the express purpose articulated by the United States in overhauling its trade strategy, namely, to redress trade outcomes that it was no longer willing to tolerate, to understand the unravelling of said procedures better.

Against this background, we assessed the possibility for collective action based on the WTO procedures that facilitate joint action and encourage multilateral dialogue among Members. Specifically, we scrutinized the situation complaint within the WTO dispute settlement mechanism, arguing that the benefit of the procedure lies in the due process that unfolds, including the public review of the situation, the collective discussion thereof, the formal panel recommendations and rulings, and the signal (powerful in our estimation) that it sends of the resilience of the multilateral system. We observed that GATT Article XXV:1 endorses joint action to further the objectives of the WTO Agreements. In complement with ordinary bilateral engagement (to negotiate trade preferences, form agreements, and resolve disputes), we reviewed how the established rules enable the trading community to pursue joint action to address domestic and mutual interests in complex, cumulative circumstances. We conclude that, if undertaken, joint action, via a situation complaint, can raise each Member’s voice into a countervailing choir, and, more importantly, it can reinforce the mutual benefits derived from the multilateral trading system. Joint action thus serves a double purpose in engaging domestic concerns and the collective interests of those intending to preserve the multilateral system on which each Member depends.

While the United States’ trade strategy served as an impetus for our assessment, our novel contributions apply generally to any Member in a position to use asymmetric economic power to revise Members’ mutual bargains through unilateral exploitation of economic inter-dependencies, in defiance of their WTO commitments. In laying out a potential pathway for forming collective interests and responding united, a broader implication for the article could extend to fresh thinking as to how constellations of Members can achieve progress in advancing multilateral objectives in the absence of consensus while remaining committed to, even reinforcing, WTO norms.

In using collective action as an organizing principle, we acknowledge that we only establish the possibility within the WTO system and do not shed light on the factors determining the likelihood of successful collective actions. When Mancur Olson challenged group theory in the 1960s, he noted common interests were not enough to produce a public good, for ‘rational, self-interested individuals will not act to achieve their common or group interests’.Footnote 193 Indeed, if WTO membership guaranteed collective interests and global public goods, explaining why any Member must occasionally pursue domestic interests and design measures inconsistent with their WTO commitments would be difficult. But, of course, Members can, and do.

However, these considerations co-exist with others that insist, as interests evolve, that repeated acts of cooperation can foster interdependence or solidarity.Footnote 194 Connecting this insight to past GATT practice, we have observed that strategic decisions were undertaken with a keen eye towards global impact. For this reason, Ambassador Lacarte, a founding architect of the GATT/WTO system, held that equitable considerations must be as important when applied to trading partners as to domestic interest groups when formulating trade policies.

In a similar vein, laboratory experiments and field research on collective action have expanded new possibilities for collective action in certain contexts.Footnote 195 There are considerable open questions concerning the potential for collective action by a heterogenous community since heterogeneity extends well beyond size, economic interests, and competing strategic objectives.Footnote 196 Our emphasis here has, however, aligned with some of Elinor Olstrom’s design principles for collective action by stressing that impacted Members come together for face-to-face discussion of an ‘optimal’ joint strategy to hopefully increase cooperation over time.Footnote 197 Further research could draw upon this work to explore credible buy-ins for WTO collective action, drawing upon different theoretical bases, including rational choice or evolutionary.Footnote 198 Future work could expand upon the outcomes of joint, palliative action to fight uncertainty with certainty, supporting growth rather than fighting over irretrievably lost gains.Footnote 199

To conclude, whether the WTO system collapses will not be determined by rule-breaking by one Member. Rather, it will be determined by how such defections are perceived, justified, rationalized, accepted, and repeated by other Members. We acknowledge that the operation of collective action, like other joint action initiatives, may initially struggle to find its footing within the WTO.Footnote 200 At the same time, the experience of this singular defection by the United States will irrevocably change the historical data on which states base their policy choices and on which theoretical treatments of collective action will be predicated. We cannot predict what lessons Members will draw, but our proposals afford a space for a return home, if and when the time calls for it.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ignacio Garcia Bercero, Kathleen Claussen, Lothar Ehring, Michael Gasiorek, Rob Howse, Andrew Lang, Simon Lester, Emily Lydgate, Inu Manak, Gabrielle Marceau, Petros Mavroidis, Krzystof Pelc, Amy Porges, and Alan Sykes for detailed comments on early versions of this work. We thank Thalia Kalai for her editing assistance.