How teachers are supported, inspired and nurtured has long been a focus of academics, school leaders and politicians. In a world of increasingly restricted resources, both financial and material, it becomes imperative to consider new ways to ignite new thinking about the purpose of education as well as the role of educators. We hear about children being the future, that our future is in their hands, that we need to prepare children with twenty-first-century skills but beyond the rhetoric, practice, professional learning opportunities and systems seem glacial in their ability to adapt and flex to the needs of the era. If the jobs that today’s children and young people will have in the future, are not yet invented and with climate anxiety on the rise, how are teachers and school leaders preparing themselves to inspire and nurture those in their care? Though this is not political statement, since the turn of the century, politicians, academics, business leaders and educators have been repeating a similar mantra – children are not ready for a world in which climate change and other sustainability challenges will impact their lives, livelihoods and ways of living. This book aims to provide a catalyst for discussions in staff rooms, classrooms, lecture rooms and any other space in which the questions about the purpose of education now are evoked.

Before framing the purpose of this book, let us introduce ourselves. James is an experienced school leader and has a doctorate in the study of the diversities of creative learning. He is the founding Headteacher of the University of Cambridge Primary School, a research-informed government school in the UK. He is now the CEO of Avanti Schools Trust, a multi-academy trust that runs primary and secondary schools in the UK. Emily is a professor of climate science, a leading voice in the international discourse about climate change and founding director of Cambridge Zero, the major transdisciplinary climate initiative at the University of Cambridge. And Harry is an historian and political theorist who co-launched Cambridge’s Centre for the Future of Democracy. This could be the beginning of a bad joke: a teacher, a scientist and an historian … But the diversity of our disciplinary interests reflects the approach of this Education Vision book – to bring together a range of voices with different perspectives from diverse subject areas to talk about the big challenges of the day.

The book is structured with two different types of chapters: manifesto chapters and teacher response chapters. The manifestos in this book are written by different authors and derive from different disciplines. They’re obviously not party political – they certainly don’t offer comprehensive policy prescriptions or precise governance strategies – nor do they share ideological commitments or even the same views on the role or purpose of education.

Each manifesto has its own distinct structure and orientation. Some are empirical, others theoretical. Some are declarative, others are more discursive. Most rest in part on personal reflections, a few are framed from a more distant perspective. The rhythm and emphases of their arguments differ. They are diverse, and deliberately so.

What they have in common, however, is an expansive view of the role and potential of children (in schools, in society, in politics), and the capacity for educational reform. In that sense, they’re all, in a certain way, optimistic. The pictures they paint of current educational conditions or worldly predicaments are sometimes bleak. But they all accept that change is possible and that children – as either agents or participants – must be placed at the heart of it.

The first manifesto sets out the challenges children will face over their lifetimes, in particular challenges arising as consequences of climate change and the destruction of nature within the context of growing social inequalities. Subsequent manifestos are focused on the response of children to these threats, though they are applicable more broadly. How can we enable children to have a greater voice in their future, and where do children fit in our democratic decision-making structures? How can our pedogeological structures respond to provide the holistic view, spanning sciences and arts, that is required to reimagine our relationship with the world? How can we support children to thrive – on one hand by drawing in practical terms on an understanding of the biology of stress and on the other more prosaically by enabling them to consider the purpose of life? Finally, how can we better connect our knowledge and experiences globally to inform and empower children around the world, and through education support a journey to a sustainable future that is also fair and just?

In different ways, each manifesto registers scepticism about prevailing disciplinary norms and the effects these norms have on the way children are perceived, understood and treated. Each also proposes a new mode of operation or way of thinking, designed to both reorient a field of research and do greater justice to the dignity, importance and power of young people. All the manifestos in this collection make a call to action.

Readers are encouraged to question these claims and reflect on the differences and similarities – in structure, tone and content – between the manifestos. The collection is intentionally eclectic. And while we hope all of them resonate and persuade, we don’t expect every manifesto to land with every reader. They should all, in their own way, be stimulating and provocative, but it’s readers’ responsibility to adjudicate their strengths and weaknesses and draw conclusions about what’s useful or needed. Conventional manifestos put prescriptiveness front and centre. By contrast, we want the relationship between author(s) and reader to be dialogic and democratic.

Following each chapter, practising teachers, school leaders and teaching assistant write responses, to suggest ways in which the manifesto ideas/ideals could manifest in the context of classrooms and schools. At the end of each practitioner chapter, there are provocations to invite the reader to contribute their own thinking for their own contexts. The reader will note that each chapter looks different. We offered authors the freedom to respond freely, allowing for diversity of positioning, presentation and purpose. We included some stylistic ‘hooks’ especially at the end of the practitioner wisdom chapters, the ‘Over to You’ sections, to invite the reader to join us in the dialogue. This is not a book with answers. It is a book that aims to provoke new thinking and to ask for more, better, bolder questioning about how we work as educators in schools. In the remaining part of this chapter, we position the reason why a book like this has relevance and why its questions will have longevity in our collective endeavour to contribute new ideas to the mix.

0.1 Climate Matters: To Children

The idea for this book came from the school where James was Executive Headteacher, which Emily’s children attend and where Harry has conducted research about democracy. It started with the adults listening to the children:

Vignette of Despair

Gemma turned the TV off. Sir David Attenborough, the famous British natural scientist, had taken her on a journey to the furthest corners of the planet and warned of the dangers to penguins, polar bears, snow leopards and many other animals. Gemma turned to her mum and said, ‘There is no point in living, just no point.’ Her mum looked horrified and frightened. How could her nine-year-old daughter be so pessimistic about life? How had her childhood become so caught up in worry about the future that she felt there was no longer any point? Gemma went on to explain that she wasn’t speaking about herself as an individual, rather the whole of humanity: she didn’t understand the point of humanity if the outcome of our collective actions is simply destruction.

Vignette of Values

Tom is autistic. He visits his headteacher’s office daily. Sometimes he talks. Sometimes he sits eating crackers and then leaves. Today he spoke.

‘You see, the problem is the adults need to do more to teach us about life. We need to know about being kind and doing stuff for other people. You know what I mean, like, on the way to school, this parent in front of me said to his son, “just push past everyone else”, but you see that is not compassionate because everyone is trying to get to school on time. That dad should have thought about everyone not just his son and pushing past. You know what I mean? We need the adults to show us more gratitude – I mean how to be grateful for what we have in life, for this school, for the teachers, for the stuff we have, isn’t it? Otherwise, everyone will be selfish and not think about the community … and then the world will die.’

Vignette for Action

Alistair and Aisha came to class with a bag of coins. They had raised £12.80. ‘We made a stall outside Al’s house and we made lemonade and sold it. We wanted to raise money to help protect animals.’

These three vignettes give an example of the ways children engage in a world that they see is increasingly fractured. More than ever, children have access to information, misinformation and populist/influencer accounts of realities that, instead of providing knowledge, have left them confused and worried. Dame Rachel de Souza, the UK children’s commissioner, has sought evidence and possible responses to influence government policy; to explain to politicians that climate change matters to children and that therefore it must matter to adults, and especially to those who work in schools. What follows in this chapter are three starting points to consider how we approach climate change and living sustainably on a planet with finite resources.

0.2 Developing Knowledge and Understanding of Climate Change and Sustainability for Education

It is evident that our current model of society is unsustainable. We use more resources than our planet can deliver. We are at the brink of a human-induced mass extinction of species. Our polluting and destructive ways threaten our own lives. The inequalities in global society are extreme and compound the environmental threats to the human and natural world. Social cohesion is strained and being further stressed by climate change threatening basic provisions. The very sense of individual purpose and meaning is, for many people, waning.

Feelings of anxiety and despair abound, especially among young people. Drawing on the work of tens of thousands of experts, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has concluded that there is a ‘rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all’ (IPCC, 2023). If that is a shocking statement to read as an adult, pause and imagine for a moment what is means to a child today.

But if we have arrived at such a dysfunctional, dystopian place in our history, what place does education have in helping to shape a productive response? How can we better prepare young people around the world for the future? How can we build the foundations to support more sustainable and just societies? How can we empower learners to take informed decisions and take personal and collective action to change society and care for the planet?

This book attempts to offer some preliminary thoughts to these important questions as well as invite more questions in the contexts the reader finds themselves. A starting point is to understand what it is we are wanting to achieve through children’s education in the context of climate change and sustainability.

Firstly, we can ensure children have an awareness of the challenges that are likely to be defining features of their lives. The three C’s of climate, conservation, community are not the traditional components of educational curricula, and they transcend traditional disciplines. However, it is vital to develop knowledge and a holistic understanding of these topics to properly equip children to comprehend the challenges that are facing the world today. The environmentalist Mary Colwell has argued for the need to reconnect young people in the UK with the natural world around them through education, ‘not just because it’s fascinating, not just because it’s got benefits for mental health, but because we’ll need these young people to create a world we can all live in’ (Colwell, Reference Colwell2021). This dialogue must happen in an inclusive way that respects cultural diversity – too often some groups of society are perceived to be the unique custodians of these issues. For example people of colour in the UK face systemic barriers in accessing and thriving in green spaces (Pettinato, Reference Pettinato2023). A transdisciplinary approach is required that not only encompasses scientific facts of environmental change, but addresses the social, economic and behavioural facets of climate justice and action-based solutions, and contextualises this in learner’s real-life experience and aspirations (UNESCO, 2020).

Secondly, we can ensure children develop the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to respond to these challenges over their lifetimes. This relates to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals which include a target that by 2030 all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development. In part it means encouraging learners to discuss and explore alternative values to those of highly consumer-driven societies, recognising young people are an important consumer group and that the way their consumption patterns and behaviours evolve will greatly influence the sustainability trajectories of their countries (UNESCO, 2020). It means responding to the opportunities and risks brought about by technological advances and understanding what role technology can play in supporting sustainable futures. It also means identifying the vocational training required to underpin the employment of the future, and the inspiration and competencies for them to lead the change. Showcasing potential green careers is an essential element of this. A summer intern working with Emily at Cambridge Zero produced a series of films to ‘raise awareness of the great diversity of green jobs that are currently available, as well as those that will be available in future … thereby empowering young people to pursue a career that has a positive impact on the planet’ (Prosser, Reference Prosser2021). More broadly, and reflecting one of the vignette’s above, it means giving children a values-based framework to enable them to construct a new, fairer and more sustainable society.

Finally, we can ensure children are supported emotionally and have the confidence to undertake transformative action or influence societal change towards a more sustainable world. It is important to recognise the real anxiety of many children and young people about their future, and to provide them with the tools to cope. Studies in the UK indicate that while there is little generational difference in terms of belief in climate change and its impacts, younger generations have stronger negative emotions of fear, guilt and outrage. Responding to that means giving children a sense of agency today, enabling them to meaningfully participate in actions and decisions that will impact their future. Doing so will not only fulfil our duty to respect and to support children (who often have ingenious solutions to sustainability challenges), it is also the right and just thing to do – a first step in tackling inter-generational inequity (Poortinga, Demski and Steentjes, Reference Poortinga, Demski and Steentjes2023).

A creative project to embed a sense of agency that was delivered at James’ school in collaboration with Cambridge Zero. Children created artworks in five categories – poles and oceans, endangered animals, trees and plants, people, and words/phrases associated with climate change – which were adhered to the faces of cardboard cubes. The cubes could be moved around and rotated, representing our ability to enact change, and mirrors were incorporated to highlight how we can all be agents of change – the children and those enjoying their work (see Figure 0.1). The project had powerful symbolism and provided an opportunity for rich discussions among the children. It also highlights the importance of a fourth C as a key component of educational offerings: creativity. This is an essential enabler of the sort of innovative thinking required to imagine and realise a sustainable future.

A coherent and effective strategy for educating children on climate change and sustainability needs to sit within a reimagined lifelong learning framework and a broader context of supporting active and compassionate citizenship. The objective should be not only to support the accomplishments of individuals, but also to contribute to the collective prosperity of the world we inhabit. Measurements of the quality of such an educational offering will need to be developed – which may focus more on learning content and its contribution to sustainability, and less on the achievement of specific learning outcomes.

Schools have a central place themselves within communities. The learnings that are conveyed to students in educational establishments, can rapidly diffuse through family networks and other community pathways, dissemination which can be proactively supported through engagement activities that embrace local contexts. Schools can also ensure sustainability-related learning content and its pedagogies are reinforced by the way their own facilities are managed and how decisions are made within their institution, including empowering children and creating opportunities for them to take an active role in the development and implementation of sustainability policies.

0.3 Developing Democratic Spaces for Children in Education

Since Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future movement, children have played a more visible role in protest politics. However, because children are excluded from formal democratic activities, like voting, their voice and agency carry less political weight. So, notwithstanding their profile in public campaigns, children’s concerns and interests are more likely to be overlooked in political discourse and decision-making.

The vignettes of despair and value, discussed above, give a taste of children’s predicament. They show that, although children have political preferences (about climate change), and moral priorities (about community), their relative disempowerment means their interests and concerns are liable to be ignored in favour of adult preferences. This exposes a major error in one of the common assumptions about the place and role of children in democratic life. It’s argued that children don’t need more democratic rights because their interests and preferences are already represented by their parents or family, their teachers and maybe even by politicians. However, as these vignettes reveal, adults don’t always or necessarily understand or cater for children’s preferences, and, as a consequence, children are often inadequately represented.

Harry encountered similar viewpoints while conducting research into children’s attitudes to democracy, voting and representation – hosted in the University of Cambridge Primary School (Pearse, Reference Pearse2023b). As a group, children don’t share the same concerns or priorities; they’re not a homogenised constituency – much in the same way that adults aren’t. Many of the children involved in the research were engaged in politics, or at least curious about the prospect of voting. Others, however, were not. And some, in fact, were already disillusioned with democratic process and actors. And yet, despite this range of opinion, most of the children were sceptical about existing processes or mechanisms of child representation. They understood that, in certain respects, parents and teachers were able and willing to act in children’s interests, but also largely agreed that the people best placed to understand the interests, beliefs or conundrums of children are children themselves. They acknowledged that children have political perspectives, and ethical viewpoints or intuitions, which are sometimes unfamiliar to other cohorts; and that their perspectives and intuitions not being adequately considered or heeded by adults or the democratic institutions.

To some extent, this helps explain children’s increasing involvement in grassroots political protest. Many children recognise that democratic politics is failing to reflect or represent their interests, and that the best way to channel and communicate one’s priorities is often to do so oneself, rather than leave it to others.

Of course, the same calculation does not, and cannot, apply in more formal political settings. Children aren’t allowed to stand for parliament and represent other children, for much the same reasons they’re not allowed to become surgeons or lawyers or police officers – jobs that rightly require qualifications that children inevitably lack. However, just because descriptive representation is off the table, it doesn’t mean a more general form of political representation should be as well. In fact, the latter is increasingly urgent, for without representation, children will remain excluded from political discourse and processes, and their preferences and perspectives will continue to be overlooked or marginalised. As the UK Children’s Commissioners (2020) put it, as children’s ‘right to be heard and involved in decision-making processes … is being denied … the UK government does not prioritise children’s rights or voices in policy or legislative processes’.

Climate change is probably the issue that best illustrates the disjuncture between children’s political concerns and concrete political action. We know that young people and children are acutely anxious about climate collapse (Hickman et al., Reference Hickman2021). And yet, despite their concerns, adult-run politics has failed to take adequate preventative or mitigatory action. The UK Children’s Commissioners cite England’s initial COVID-19 response measures as further evidence that children’s political interests are frequently deprioritised – in this case, relative to commercial retail interests or the safety of the elderly. As a backdrop to these policy failures, electoral outcomes are increasingly skewing by age (see Brexit and the election of Donald Trump), with young people routinely losing out to the old (see the fate of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in 2017) (Runciman, Reference Runciman2018, pp. 163–164). Children – who can’t vote – are in an even worse position than younger voting demographics. And still, in the long run – after every electoral decision, or constitutional change, or period of existential policy inaction – children will inevitably face the lion’s share of the consequences (measured temporally).

The justifications for the marginalisation of children are weak, and in the interests of fairness and justice, children require a more significant political voice. Children are not lesser citizens than adults. They have as much moral value and integrity, and they’re as familiar with, and as shaped by, their personal experience, as their adult peers. In many important ways, children and adults are equals (Pearse, Reference Pearse2023a). And yet, politically, they’re jarringly unequal, and children have considerably less scope to express and prosecute their beliefs and perspectives.

This arrangement is propped up by another common but erroneous assumption that children are incapable of ‘properly’ participating; that they lack the qualities – competence, rationality, wisdom – that equip a person for democratic life. Unhelpfully, the definition of these qualities, and what they entail, is unknown, or not agreed upon. Furthermore, a voting age threshold justified by virtually any definition of competence or wisdom wouldn’t just stop children from voting; it’d also disqualify most adults from democratic participation. Democracies have mostly dispensed with the idea that political rights are only to be gifted to those with particular characteristics – be it wealth, or maleness, or whiteness, or the right religion (Olsson, Reference Olsson2008, pp. 57–59). Universal suffrage ought to mean that every citizen is entitled to a democratic life, irrespective of intelligence, identity or resources. Age (as a vague proxy for competence) is the only remaining exclusion. And this too – at least in its current form (excluding all those under eighteen) – is likely to be overcome eventually.

What it might mean, or what it could look like, to better integrate young children into democracy is uncertain. Extending the franchise is the most radical option, but there are other ways of ensuring children have a voice in democratic politics. They could be included in deliberative exercises – either with adults, or just with other children – or allowed to contribute to decision-making in the institutions they’re most closely involved in, like schools (Pearse, Reference Pearse2022).

0.4 Developing Spaces for Enquiry in Education

Being an educator in the twenty-first century has become an increasingly complex role. Educating children to be healthy, engaged and active citizens in a world that is fraught with complex political, economic and social issues is vital and incredibly difficult. Governments, parents and society expect more from schools and the people (the teachers, teaching assistants and school leaders) who work within them. Being an educator requires more than the delivery of (often myopic) government edicts and strategies. The act of teaching necessitates new thinking, an invigorated and empowered professionalism, and a view that teaching is an intellectualised profession; doing more of the same will not support better social mobility and outcomes for children.

What really matters in education? Though the question is continually asked, the answers are often evasive. In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic emphasised that if one thing can be relied upon, it’s that things change. However, we also know that state education is very slow to do so. And here lies the crux of our dilemma as educators: how can we better respond to the fast-paced changes in the world, in technology, in social and cultural norms, to massed migration? If climate change matters to the world and to people, how does it matter within education systems and within schools? In the post-pandemic context, the questions about how we educate our children and young people have become more urgent with our answers more critical.

The world is in crisis. The future for our children, grandchildren and great grandchildren is uncertain. There are at least three existential uncertainties: the survival of planet Earth, the unravelling of cohesive communities, and the risks to individuals’ sense of purpose and meaning. The forces for change are held back by technocratic and unimaginative responses to these challenges. Our education systems are no longer fit to reimagine, reinvent and reinvigorate our response-ability (the ability/capability to respond) to the challenges that will arise. The world – and the education systems we create – require a revolution of the social imagination through education, leading us to a tomorrow of active and compassionate citizenship.

Schools are important social places. Whilst there is a centralised attempt to standardise schools, in reality, they are diversly experienced intercultural spaces. They adapt and change as society evolves around them. In recent times, there has been an increase in massed migration across the globe, and unprecedented levels of interaction among diverse populations. We live in times of massed uncertainty with a perceived sense of the rise in xenophobia (and associated social phobias like Islamophobia, homophobia) in response to the challenges of cultural diversities.

Within this context, in recent years, there is a growing call for the teaching profession to be ‘research-informed’; for example the current UK Government has invited schools to apply to be ‘research schools’ to disseminate meta-research, or ‘big data’ evidence, about what works in schools. However, teachers’ engagement with research, and their use of research in their own classrooms has not yet become the norm. This is because such large-scale research does not always translate into the nuanced dialects/contexts/realities characteristic of our range of schools and classrooms. Teachers need resources that explicitly demonstrate, with real examples, how the use of research can be applied in classroom and school contexts. Teachers need to reframe their roles as teaching-researchers, as intellectuals who research their practice – people who ask questions about their practice, who problematise, who seek new opportunities and who ‘tinker’ with existing conventions, building not only research-informed but also research-generating practices.

Research-informed practice could be nurtured in three key aspects: by developing an ethic of trust, by acknowledging that phronēsis (or practical wisdom) arises when teachers bridge their practitioner wisdom with academic research and by giving opportunities for teachers to identify what things matter in their classrooms (see the Foreword). There have been examples of these aspects in James’ school.

Schools are busy places. What goes on in schools is much more complex than the delivery of a curriculum. The principle of developing research-informed practitioners and practice is evident in the mission of the Chartered College of Teaching, which was established in the UK as a professional body for teachers and teaching assistants. A sense of teacher and children agency and ethic of trust became a cultural norm at the University of Cambridge Primary School. As the following vignette demonstrates, one of James’ colleagues was able to inspire change in strategies to support inclusive practice – this was a result of a culture of trust within the school.

In our first year, I noticed one of my new teaching assistant colleagues. She was passionate and believed in the power of reading to effect change. I gave Aimee a copy of the ‘Maximising the Impact of Teaching Assistant’ research. This research analysed the impact of teaching assistants (TAs) on outcomes for children. Although the Education Endowment Foundation suggested that they have little impact on students’ outcomes, we know that TAs add value to the life of a school.

On Monday morning, Aimee was sitting outside my office and said, ‘You need to deploy the TAs differently.’ She explained the negative results of one-to-one support and instead spoke of scaffolding up, not differentiating down. I said, ‘Go on then. Make the changes.’ What arose was a TA community that developed a researcher mindset – each week they pose problems, and together they discuss possible solutions, drawing from research into speech and language, for example.

Professional development in schools is another way to support the notion of teachers not as researchers but as teachers with researcher mindsets. A lesson study approach (Rolls and Seleznyov, Reference Rolls and Seleznyov2020) can be beneficial. This involves identifying problems and using academic expertise to shine different knowledge on the matter, which in turn supports teachers’ planning. Following a period of shared planning, the academic expert and practitioners observe and model lessons which are then discussed and analysed. Bridging these different forms of knowledge creates a cultural shift where teachers were actively engaging in research and new ideas, and are creating ways to use and develop these within their classrooms. There is explicit recognition of practitioner wisdom sitting alongside academic knowledge.

The third aspect in developing research mindsets is for teachers to identify things that matter for the children in their care. For example the curriculum design in James’ school gives primacy to oracy and dialogue – based on the practical reflection that children who speak and ask questions seem to do academically and socially better than those who do not. It drew inspiration from social sciences and built on the concept – to Professor Robin Alexander’s work on culture and dialogue and his collation of research for the Cambridge Primary Review (Alexander, Reference Alexander2010). The University of Cambridge Primary School was fortunate to work with Professor Sue Gathercole, whose research about working memory helped frame how teachers should give instructions so that the roughly 30 per cent of people with poor working memory do not miss out on key learning. The school also has an ongoing relationship with Professor Usha Goswami and is participating in a project about music, rhyme and rhythm and their impact on language development from a neuroscience perspective. This research has provided new insights into practical issues faced in classrooms, and as such, teachers have found it meaningful and are willing to engage with it.

0.5 A Draft Framework for Thinking about Sustainability Education

We uphold the view that siloed thinking about climate change will not help us find innovative and meaningful mitigations and solutions. We are of the view that, as well as academic knowledge about the climate, science and technology, there is a need to support children and young people in developing possibilities thinking mindsets, where creativities and critical thinking are vital and not peripheral to the education experience. Moreover, as well as the scientific knowledge, other domains of learning, for example philosophy, religion, ethics, arts, languages, politics, psychology and sociology, must be included in the possibilities thinking. What happens when theologians and climate scientists grapple with the issues? What will arise if musicians work with sociologists to make sense of the complexities and nuances of sustainability? What happens if we think in a transdisciplinary way? Moreover, where are the democratic voicings in our schools and examples of innovation (see also Biddulph and Baldacchino, Reference Biddulph, Baldacchino, Biddulph, Rolls and Flutter2023; Biddulph, Rolls and Flutter, Reference Biddulph, Rolls and Flutter2023)?

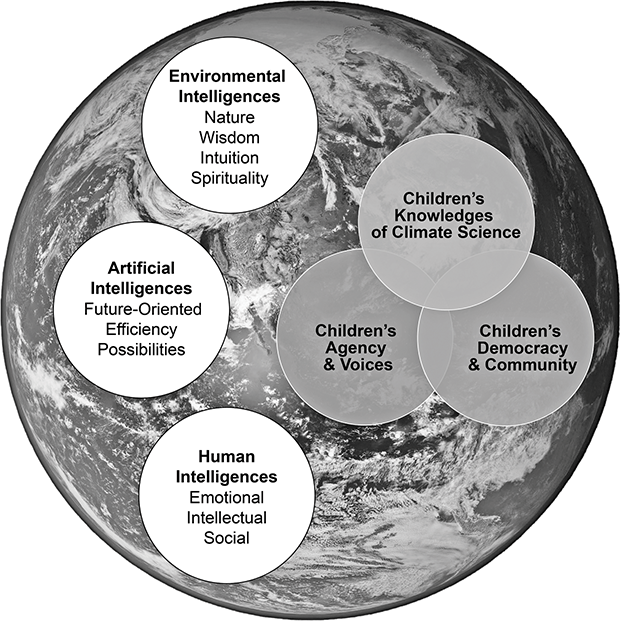

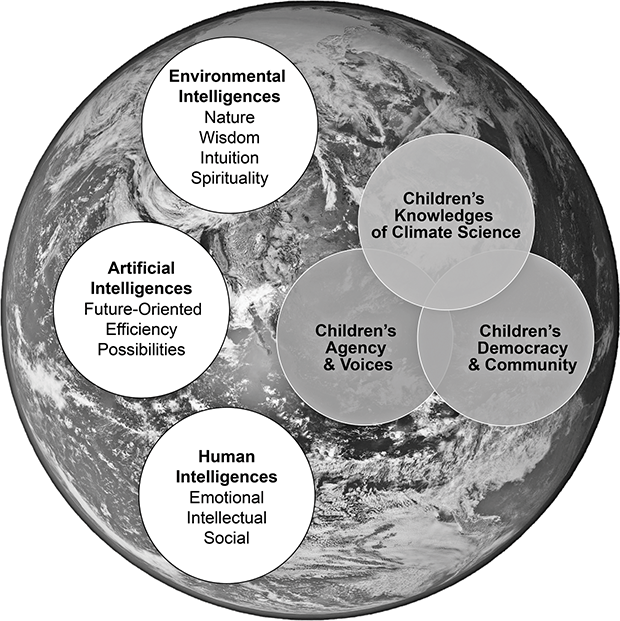

If we maintain a post-human theoretical perspective, which states that humans are a part of the ecosystem and not in a privileged position apart from or above the system, then we start thinking differently about how the world is ordered and our place, privilege and power within it. Figure 0.2 presents a new framework for thinking about ways to reimagine education.

Figure 0.2Long description

The left of the planet has three separate circles outlining different categories of intelligences: 1. Environmental intelligences: Nature, wisdom, intuition, spirituality; 2. Artificial intelligences: Future-oriented, efficiency, possibilities; 3. Human intelligences: Emotional, intellectual, and social. On the right of the planet are three intersecting circles with the following text: 1. Children’s knowledges of climate science, 2. Children’s agency and voices; 3. Children’s democracy and community.

The framework presents three broad forms of intelligences – human, environmental and artificial. It provokes questions about how humans interact with AI and the environment. In this worldview, what does human intelligence offer? And how does this compare to the intelligence of the environment, to wisdom traditions and qualities of intuition and spirituality? How can artificial intelligence contribute? As well as these intelligences, there are new knowledges about democracy and community, about children’s co-agency and pedagogic ways to raise children’s voices and new meaningful knowledge about climate change. The interconnected relationships are messy with multiple pathways and opportunities. This view of sustainability education is articulated through dialogue between educators, between children and between educators and children – co-authoring and co-creating new routes towards a sustainable education. It is education enacting in terms of possibilities, creativities and as the social imagination.

0.6 A Purposefully Eclectic Book

It has been a very difficult book to bring together. Our intention was to forge a bridge between academic research and the ideas, insights and wisdom of primary school teachers. However, trying to connect case studies from across the globe, ensuring a rich and diverse response to the environmental challenges we all face, has been almost impossible. And yet, this book and the books that follow attempt to bring ‘possibilities and creativities thinking’ (Burnard and Loughrey, Reference Burnard and Loughrey2023) into the DNA of our education systems, schools and classrooms, as well as the mindsets of those people who work with our children and young people.

Possibilities and creativities thinking is the imaginative and action-oriented process driving us from what is to what could be. It is more than the use of the imagination. Considering the challenges or problems with which we are faced, possibilities thinking offers a theoretical way of bridging current ideas with exploring the diversity of new ideas. Creativities thinking involves transdisciplinary and intercultural ways of approaching problems. This involves dialogue, appreciation of diverse ideas, welcoming cultural differences, responding to problems with the use of the arts, allowing for uncertainty to exist and remain, and brought about in social contexts (Burnard and Loughrey, Reference Burnard and Loughrey2023). Both concepts are a response to Maxine Greene’s (Reference Greene2000) call to educators to think more imaginatively – to reimagine society as it could be, to remember our duty to build our social imagination, and to develop the capacity to (re)invent visions of society. Possibilities and creativities thinking is most promising when considered as a collaborative participatory endeavour. It is intercultural and situated in social actions. It is positive, hopeful and passionate, and it represents a firm belief in the potential of human creativity and the collective human spirit.

So, why has it been difficult to build new global collaborations to discuss the uncertainties of thriving on planet Earth? How do we address the dominance of white hegemonic thinking, and the fact that climate change discourse is rooted primarily in the Global North? Why has it been difficult to find case global studies, or engender trans- and intercultural dialogue about our planet?

In part, the reasons for these problems stem from the systematic rigidity of our governance and education systems – our silos of knowledge and research disciplines, and the ways we organise societies. Rather than building bridges, society has constructed barriers between people, places and politics. In a recent professional journal entry, a reflective diary that some school leaders keep, James noted some of the problems of his and his fellow editors’ white, educated, privileged positioning, bringing to the fore the challenges experienced in collating the collection of Education Visions.

This book seems an enormous task. Reminds me of my doctoral thesis, exploring diversities, trying to make sense of who I was and how I was to engage with people who, in the context in which I was working, were seen as the ‘other’. Through the process, I was reminded to ask questions about how I located myself, how much I revealed about myself, to reconcile my different roles and positions. As Helene Cixous (Reference Cixous and Sellers1994, p. xv) explains,

Like all those whose vital substance is cut from the same fabric as writing, I am constantly impelled to ask myself the questions engendered by this structure which is at once single and double: questions of the ethical, politico-cultural, aesthetic, destinal value of this constitution; questions of the necessity of writing for myself and for others; of the usefulness, the strangeness of forever being here and elsewhere, ever here as elsewhere, elsewhere as here, I and the other, I as the other, etc.

It has been difficult to find contacts across the world, to weave into the fabric of our possibilities thinking the threads of sub-Saharan Africa, or first peoples’ wisdom, or of island states, or countries in the Middle East, or from experts in countries for whom raised sea levels will obliterate life. And yet, the book started with the intention to weave this rich diverse human capacity to invent new visions. As McLaren (in hooks, Reference hooks1994, p. 31) says, we must guard against seeing diversity as somehow a harmonious, ‘ensemble of benign cultural spheres’ but instead to acknowledge that, ‘when we try to make culture [diversities] an undisturbed space of harmony and agreement where social relations exist within cultural forms of uninterrupted accords, we subscribe to a form of social amnesia in which we forget that all knowledge is forged in histories that are played out in the field of social antagonisms’.

Who am I (we) in presenting possibilities without ‘whitewashing’ the issues? How do we make sense of the nuances, in the inflections of accents, languages, ways of thinking, knowledges and practices? How do we invite more dialogue? How do we embrace the uncertainties that arise with the niggling feeling that we need to hear more voices?

Many examples in this book are drawn from experiences at the University of Cambridge Primary School (UCPS), in the UK – partly for the practical reason that James, the concept editor of Education Visions, works there and partly because the school’s raison d’être is to be global and a conduit for partnerships. The school is a state-funded school with no additional resources from the University of Cambridge. It opened in 2015 and serves a diverse community, including disadvantaged families and a much higher than average intake of children with special educational needs and disabilities, with some families from academics working at the University of Cambridge as well as those representing the local community. UCPS currently has more than 600 pupils, from nursery to Year 6 (age three to eleven). It is the first university training school for primary education in the UK and partners with colleagues at the University to collaborate in research projects and provide initial teacher education to trainee teachers. The hope is that in subsequent books, greater diversities will be presented. As such, we want to make it clear from the outset that this book is necessarily incomplete. Its completion comes when the reader brings together people in their own countries, homes, schools, education communities and other social spaces to discuss the issues raised. Its completion comes when the readers challenge the visions and our collected responses. Its completion comes when new ideas are offered.