1 Definition and Model of Mysticism

The etymology of the English term “mystic” traces back to the ancient Greek Eleusinian rites, where initiates were required to remain silent (muein) about the details of the ceremony, giving rise to the Greek term mustikos (i.e., initiates). It denotes an encounter that transcends worldly description and is withheld from non-initiates. Similar meanings are found, for example, in Chinese, shen mi, “divine secrets.” Therefore, mysticism denotes an experience that extends beyond perceived reality and its linguistic representation.

This return to the linguistic root aligns with William James’s (Reference James1902) classical definition, which identifies two essential characteristics of mysticism: the noetic and the ineffable. The noetic aspect refers to insights apprehended through direct intuitive knowledge, pointing to a deeper understanding of reality, while the ineffable pertains to experiences that transcend the limits of language. Together, these elements define mysticism as an encounter that pushes the boundaries of perceived reality and transforms the perceiver, culminating in an indescribable state of revelation. This extends the definition and scope of mysticism, encompassing all extraordinary experiences that meet these two criteria – a transcendence of perceived reality and a transformation of the individual.

Mysticism has been defined and understood in various ways, often emphasizing an altered state of consciousness distinct from the daily mundane one (Tart, Reference Tart1972). The human longing for something beyond perceived reality frequently initiates the mystical journey (Weiner, Reference Weiner1969). As such, mysticism encompasses concepts that transcend the ordinary, often described using terms such as exceptional, extraordinary, nonordinary, ecstatic, paranormal, supernormal, and altered. For instance, Murphy (Reference Murphy1992) characterizes mystical experiences as altered states that reveal deeper truths, where the “supernormal” refers to unconscious abilities brought under conscious control. Similarly, Merkur (Reference Merkur2010) frames mysticism as the practice of religious ecstatic states of consciousness, accompanied by corresponding ideologies. Given our expanded definition, this Element adopts an inclusive approach, using the term mysticism to encompass a wide range of experiences otherwise labeled differently, as long as they align with the core criteria outlined in our framework.

This Element examines the psychology of mysticism while integrating insights from religious, anthropological, and philosophical perspectives. Unlike philosophical approaches that consider the ontological status of mystical experiences, religious studies that focus on historical texts, or anthropological analyses that compare mystical practices across societies, the psychological perspective, with its emphasis on consciousness, prioritizes individual experiences. It values self-reported observations, employs empirical methodologies, and analyzes descriptive accounts of mystical states. From this viewpoint, while the objects of mysticism may be unverifiable or metaphysically elusive, the psychological impact of the experience itself remains valid and significant (Staal, Reference Staal1975). In exploring mysticism, the focus shifts from what elicits the experience to the psychological state of the individual undergoing it.

The following sections expand on the noetic and ineffable qualities that define mysticism, clarify its definition, present representative typologies and measurements in psychological research, and finally, introduce the layered hierarchy model that will be explored in depth throughout this Element.

1.1 Noetic and Ineffable

Noetic knowledge refers to insight gained directly – often through bodily experience, intuitions, visions, and revelations that reach beyond sensory processing or rational thought. These modes of knowing illustrate how mystical insight transcends the limits of ordinary perception and reasoning. They open onto a deeper grasp of reality, one that is difficult to articulate yet profoundly meaningful to those who encounter it. As Blavatsky (Reference Blavatsky1895) observed, the essence of truth cannot be fully conveyed in words or writing but must be discovered within one’s own inner experience.

Mystical knowledge often takes the form of a direct perception of reality. In this sense, mysticism resembles science in its systematic inquiry into the nature of the world – yet whereas science focuses on external phenomena, mystics seek understanding through inner experience (Radin, Reference Radin1997). Mysticism thus culminates in a form of knowing detached from sensory or mental imagery (Smart, Reference Smart1965). Huxley (Reference Huxley1954) draws a sharp contrast between mystical insight and rational or systematic reasoning, defining mysticism as a direct apprehension of reality that surpasses discursive thought while still being wholly and immediately grasped.

A key element in this process is intuition, which serves as a bridge between external symbols and inner understanding. Rooted in Aristotle’s notion of nous, often translated as intuitive reason, intuition involves the direct apprehension of primary, self-evident principles (Bolton, Reference Bolton and Osbeck2014). For Coomaraswamy (Reference Coomaraswamy1977), intuition allows us to grasp the truths behind symbols, which themselves only point toward deeper meanings. Thus, symbols derive significance not from their own content but from the transcendent realities they reveal.

Mystical traditions also speak of “knowledge by identity,” in which one knows by becoming one with what is known (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Crabtree and Marshall2015). Unlike ordinary knowledge, which presupposes a gap between subject and object, this mode of knowing fuses the two. The faculty that mediates such knowledge is gnosis, a direct and immediate form of understanding. Meister Eckhart described this as a “pure intellect” uniting with its object without separation. In this framework, experiencing something confers its reality, a point developed by Shanon (Reference Shanon2002) under the notion of the “conferral of reality.” Similarly, Merleau-Ponty (Reference Merleau-Ponty1962) emphasized that perception does more than register details about objects; it also affirms their existence. To experience something is thus already to believe in its reality. Huxley (Reference Huxley1954) extended this insight by suggesting that mystical awareness can encompass all that happens everywhere in the universe. He further proposed that attaining such superconscious states requires passing through the subconscious, one pathway being the chemistry of the individual cell – an anticipation of what might be called embodied spirituality, or knowing through becoming.

Mystical experiences are often described as ineffable because they involve a profound transformation of the self, making them resistant to verbal expression. In such states, ordinary cognitive processes are suspended, leaving no framework for articulating the experience. This raises a central question: if such experiences are ineffable, how can they yield knowledge? A common explanation is that while discursive reasoning falls silent during the experience itself, it resumes afterward, enabling interpretation and communication of the insights received.

Another crucial question follows: Is there still a perceiver once everything disappears from consciousness? The answer given by most accounts is yes. With the dissolution of the governing ego, a different form of self-awareness emerges. This self is not the familiar “I” of ordinary reasoning but a deeper awareness that observes and exists independently of egoic constructs. Obeyesekere (Reference Obeyesekere2012) describes this agency as grounded not in the “I” but in what Nietzsche (Reference Nietzsche1909) termed the “It,” as in his famous remark: “A thought comes when it wishes, and not when ‘I’ wish” (p. 24). Nietzsche’s critique unsettles the Cartesian dictum “I think, therefore I am,” suggesting instead that thought arises spontaneously, apart from the ego’s control. Freud’s The Ego and the Id might be more precisely translated as The I and the It, reflecting the distinction between the conscious self and a deeper, impersonal agency.

Although mysticism resists articulation, it is expected to enlighten and transform the way one relates to reality. In classical Jewish thought, for example, clarity of perception – not a “cloud of unknowing” – is taken as the mark of true mystical experience (Weiner, Reference Weiner1969). A claim to profound truth must engage both feeling and reason. This is why Moses, to whom the concrete laws and historical narratives of the Tanakh are attributed, is regarded as the Jewish mystic par excellence. Unlike other prophets who apprehended truth as if through a dim mirror, Moses is said to have seen it as though through a clear glass. The communicability and clarity of his vision testify to a face-to-face encounter with divine reality.

Because mysticism carries both noetic depth and ineffability, it has sometimes fostered elitism and rigidity in asserting exclusive truth. Such tensions have accompanied mysticism across the centuries and continue in the present. This Element, however, argues from a pluralistic standpoint that mysticism should cultivate inclusivity and openness, always widening its horizon of possibilities. Each mystical encounter should be treated not as a final revelation but as a gateway to further exploration, reminding us that there is always more to uncover and understand.

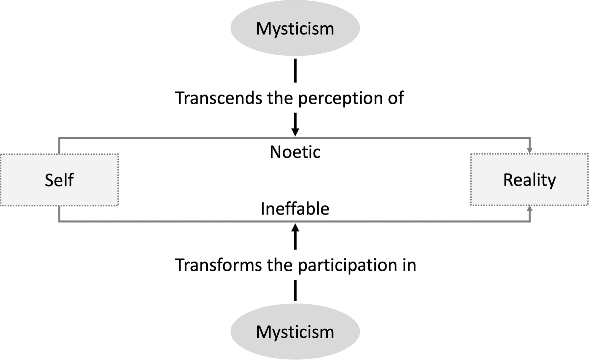

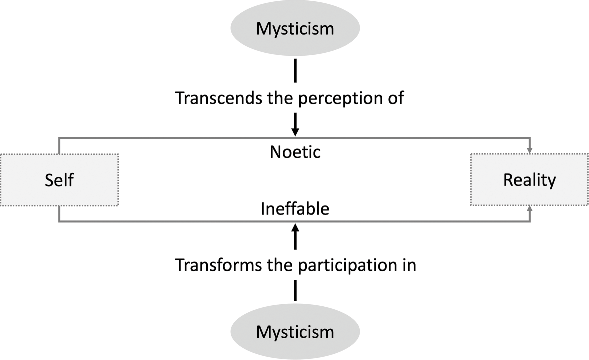

With these extended explanations in mind, three conceptual pairs emerge in defining mysticism as transcendence of perceived reality and transformation of the individual: self and reality, transcendence and transformation, and the noetic and the ineffable. Their interrelations can be described as follows. Prior to a mystical encounter, the individual self perceives and engages with reality in an ordinary way. Mysticism transcends this perception, opening onto a noetic grasp – an intuitive knowledge of a deeper dimension. Simultaneously, it transforms the individual so that their mode of interaction with reality is no longer the same. Ineffability, in this context, does not merely indicate what cannot be described because language and cognition fall short; it also renders ordinary modes of action inadequate, since action itself is a form of articulation. In this sense, mysticism moderates and modifies the interaction between self and reality, reshaping both perception and participation. Figure 1 provides a schematic view of our definition of mysticism.

Figure 1 Theoretical model of defining mysticism as transcending the perceived reality and transforming the individual.

1.2 Types and Measures

There are numerous ways to classify mysticism, with psychological assessments of such experiences relying primarily on self-reports (Jones & Gellman, Reference Jones and Gellman2022). Classical classifications, echoing Greek irrationalism (Dodds, Reference Dodds1964), often propose broad categories based on general psychological features. Naranjo (Reference Naranjo, Naranjo and Ornstein1976) identifies three types of meditative states: the negative way, the middle way, and the expressive way. The negative way emphasizes elimination, detachment, and emptiness, pursuing a path of inner emptiness. This idea is akin to the via negativa, an iconoclastic turn in mysticism in which forms attributed to the divine are regarded as limiting rather than revealing, and the mystical path is understood as the removal of such obscurations. From this perspective arises the concept of ineffability. The middle way involves concentration, absorption, and union, characterized as outer-directed and aligned with an Apollonian orientation. The expressive way, by contrast, highlights freedom, transparency, and surrender, embodying an inner-directed, Dionysian orientation. Another influential scheme distinguishes between functional and nonfunctional mysticism (Paper, Reference Paper2004). Functional ecstasies include visions, problem-solving dreams, shamanism, mediumship, and prophecy – experiences with practical implications. Nonfunctional ecstasies, in contrast, encompass unitive states, pure consciousness, and encounters with nonself, with the emphasis placed on transcending utility.

A common approach to understanding extraordinary experiences is to enumerate known examples, and measurement instruments have often adopted this strategy, asking respondents to identify or classify their own experiences. White (Reference White and Tart1997), for example, cataloged approximately 100 exceptional human experiences, organizing them into five categories: psychic, encounter, death-related, unitive, and exceptional but normal (e.g., dreams). More recent studies propose empirically derived categories such as numinous, revelatory, synchronistic, aesthetic, paranormal, and mystical experiences (Yaden & Newberg, Reference Yaden and Newberg2022). Standard textbooks in the psychology of religion likewise include discussions of paranormal experiences that overlap with religious and spiritual phenomena (e.g., Hood et al., Reference Hood, Hill and Spilka2018). Some scales explicitly target paranormal-like experiences, such as nonlocal consciousness, extraterrestrial contact, precognition, survival of consciousness, communication with the dead, clairvoyance, psychokinesis, telepathy, and automatism. Examples include the Noetic Experience and Belief Scale (Wahbeh et al., Reference Wahbeh, Yount, Vieten, Radin and Delorme2020) and an earlier, more comprehensive Anomalous Experiences Inventory (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher, Kumar and Pekala1994). At the other end of the spectrum are scales that measure more ordinary experiences of transcendence in daily life, such as awe, gratitude, mercy, connection with the transcendent, and compassionate love, as captured in the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (Underwood, Reference Underwood2011).

The dominant psychological model of mysticism, focused on unitive experience, is grounded in the classification of core features first outlined by James (Reference James1902) and Otto (Reference Otto1932), and later expanded by Stace (Reference Stace1960). This framework identifies two experiential factors: the introvertive factor, marked by the dissolution of self and spatiotemporal transcendence; and the extrovertive factor, entailing unity with the world and recognition of the subjectivity within all things. A third interpretive factor captures the appraisal of experience in terms of positive affect, sacredness, noetic quality, and ineffability. Importantly, not all mystical experiences are positive: Otto (Reference Otto1917), for instance, explicitly described the frightening and awe-inspiring aspect of the divine in his concept of the mysterium tremendum. Nevertheless, this three-factor model was operationalized in the Mysticism Scale (Hood, Reference Hood1975), which has been validated cross-culturally, with a brief eight-item version also available (Streib & Chen, Reference Streib and Chen2021). Related measures assessing mystical states occasioned by psychedelics have likewise been developed, beginning with Pahnke’s (Reference Pahnke1969) work and culminating in the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths2015), emphasizing mystical unity, positive mood, transcendence of time and space, and ineffability.

One major critique of preceding measures is that they conflate appraisal, affect, and phenomenology, as seen in the MEQ’s emphasis on positive states, leaving little room for negatively valenced mystical experiences. Challenging this narrow focus on alterations in selfhood, Taves and Barlev (Reference Taves and Barlev2023) advanced a feature-based approach that distinguishes phenomenological features of experiences from their appraisals in interview protocols. The Inventory of Nonordinary Experiences (Taves et al., Reference Taves, Ihm and Wolf2023) reflects this updated understanding by incorporating a broader range of lesser-studied phenomena, including experiences of Kundalini energy, possession states, and unitive mysticism.

Qualitative studies are particularly useful in capturing nuances that structured self-report questionnaires may overlook. One line of research has adapted Hood’s scale into qualitative investigations of various traditions, including Buddhists (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Qi, Hood and Watson2011a), Daoists (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo and Cowden2023; Chen & Guo, Reference Chen and Guo2025), North American shamans (Chen, Reference Chen2023), and soul-mate relationships (Chen & Patel, Reference Chen and Patel2021). Another approach has examined the varieties of contemplative experience among American Buddhists (Lindahl et al., Reference Lindahl, Fisher, Cooper, Rosen and Britton2017), employing open-ended questions alongside detailed coding manuals that categorize cognitive, affective, somatic, and self-related changes.

A comprehensive anthropological study conducted in the US, Ghana, China, and Vanuatu examined the experience of sensing the presence of gods, resulting in the development of the Spiritual Events Scale and the concept of Porosity – the idea that spirits can influence human thoughts and feelings, sometimes even causing harm (Luhrmann et al., Reference Luhrmann, Weisman and Aulino2021). The Spiritual Events Interview further explored how individuals perceive divine presence through auditory experiences, dreams, visual phenomena, bodily sensations, and encounters with supernatural beings, leading to the development of quantitative scales.

Certain personality and aptitudes are inducive to mysticism. Thalbourne and Delin (Reference Thalbourne and Delin1994) coined the term “transliminal” to describe a common underlying factor characterized by an involuntary susceptibility to inwardly generated psychological phenomena of an ideational and affective kind. The resulting Transliminality Scale (Chen & Ghorbani, Reference Chen and Ghorbani2024; Houran et al., Reference Houran, Thalbourne and Lange2003) measures an aptitude for heightened sensory perception and a tendency for absorption – a disposition for experiencing episodes of total attention that fully engage one’s representational resources (Tellegen & Atkinson, Reference Tellegen and Atkinson1974).

Mystical states can arise either spontaneously or under a variety of religious and spiritual contexts that offer techniques designed to induce mysticism. Shamanism, for instance, has developed systematic methods for inducing altered states of consciousness, such as through visualization or rhythmic drumming (Harner, Reference Harner1980). In laboratory-controlled settings, numerous ways have been developed to elicit different mystical states (for a review, see Ludwig, Reference Ludwig1966). These techniques are often ironically contrasting, including reduction of stimuli (e.g., isolation tanks; Hood & Morris, Reference Hood and Morris1981) and enhancement of external stimuli (e.g., stress; Hood, Reference Hood1977), as well as techniques that increase both alertness and relaxation (e.g., concentrative meditation; Deikman, Reference Deikman1966).

With the recent exploration of psychedelic drugs for psychiatric treatment, psychedelics can reliably trigger unitive mystical experiences (Merkur, Reference Merkur1998), both with psilocybin (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Richards, McCann and Jesse2006) and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD; Carhart-Harris, Reference Carhart-Harris, Muthukumaraswamy and Roseman2016). The variety of conditions that occasion mystical experience highlights the complexity of this issue. A single stimulus can produce various states of consciousness, while different stimuli can also result in the same type of conscious state. Physiological states are neither necessary nor sufficient for the experience to occur.

1.3 Layered Hierarchy Model

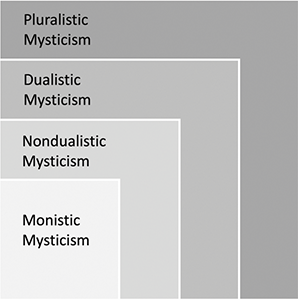

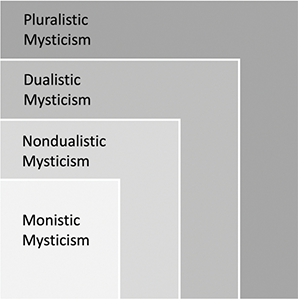

This brief review shows that mysticism is an encompassing category that incorporates a wide range of extraordinary human experiences. The central issue lies in definitions, which shape how one conceptualizes and maps different forms of mysticism. One influential perspective is the core–periphery model, depicted in Figure 2a, which locates a mystical core, such as union with the Absolute, as the ultimate truth of reality, set apart from peripheral experiences that attach this core to particular deities or traditions. This, however, is not the view we adopt. Instead, we propose a layered hierarchy model of mysticism, depicted in Figure 2b, and illustrate its layers – monistic, nondualistic, dualistic, and pluralistic – each representing a distinct configuration of perceived reality, the individual self, and the patterns of interaction between self and reality. While neither exhaustive nor definitive, the aim of this model is to chart the complex terrain of extraordinary experiences and to offer one way of understanding the variety of human experiences and the possible meanings behind them.

(a) Core and Periphery Model

(b) Layered Hierarchy Model

Figure 2 Two different conceptual models of mysticism.

The layered hierarchy model diverges from the core-periphery model in several fundamental ways. Rather than serving as a mere classification system for extraordinary human experiences, it rejects the notion that different mystical states exist as discrete, non-overlapping categories. It neither implies a hierarchical ranking of importance or progression nor suggests that one form of mysticism is more “real” than another. Instead, this framework provides a lens through which extraordinary experiences are understood as transcending human perceptions of reality by integrating both physical (body) and nonphysical (consciousness) aspects.

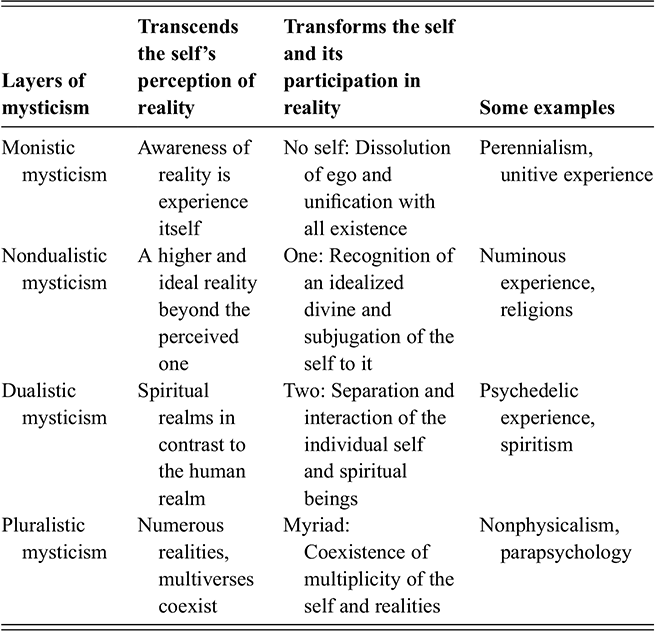

In the layered hierarchy model, monistic mysticism emphasizes the experience of oneness, where all reality is perceived as a unified whole, and the self dissolves entirely into infinite emptiness, rendering the body formless and irrelevant. This perspective is prevalent in perennialism and the concept of a unitive common core. Nondualistic mysticism introduces a higher reality beyond the mundane world, where the self partially submits to an idealized divine presence, often regarding the body as an obstacle to the soul’s liberation. Such experiences are commonly embedded within mystical traditions across various religions. Dualistic mysticism, by contrast, maintains a clear distinction between human and nonhuman realms, often involving interactions with spiritual beings or transcendent forces. Within this framework, the self remains distinct yet engages with the spirit world, with the body serving as a vessel for divine teachings, as seen in spiritism or certain psychedelic states. Pluralistic mysticism, meanwhile, embraces the coexistence of multiple realities, with the self manifesting in diverse forms and the body regarded as integral to realizing spiritual potential. This perspective is frequently expressed in nonphysicalism and parapsychological perspectives. Table 1 provides a summary of these four layers, aligning with an expanded definition of mysticism – one that encompasses both the transcendence of perceived reality and the transformation of the perceiver.

| Layers of mysticism | Transcends the self’s perception of reality | Transforms the self and its participation in reality | Some examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monistic mysticism | Awareness of reality is experience itself | No self: Dissolution of ego and unification with all existence | Perennialism, unitive experience |

| Nondualistic mysticism | A higher and ideal reality beyond the perceived one | One: Recognition of an idealized divine and subjugation of the self to it | Numinous experience, religions |

| Dualistic mysticism | Spiritual realms in contrast to the human realm | Two: Separation and interaction of the individual self and spiritual beings | Psychedelic experience, spiritism |

| Pluralistic mysticism | Numerous realities, multiverses coexist | Myriad: Coexistence of multiplicity of the self and realities | Nonphysicalism, parapsychology |

In our model, both “layer” and “hierarchy” carry distinct meanings. The hierarchical arrangement of these layers reflects multiple dimensions. First, it represents varying levels of transcendence in perceived reality, ranging from the ultimate unity of all things to the multiplicity of physical and non-physical worlds. Second, it addresses the transformation of selfhood, spanning from complete dissolution to a well-defined sense of agency, with multiple possible agents emerging within the experience. Third, it concerns the degree to which the body is involved, ranging from total irrelevance to being indispensable for the experience. The fourth dimension pertains to cultural influences – monistic experiences, being devoid of specific content, are least shaped by cultural and cognitive framing, whereas the outer layers are more susceptible to situational and interpretive factors. The layered structure also highlights the overlap between different types of mysticism: nondualistic mysticism encompasses elements of monistic mysticism, dualistic mysticism incorporates aspects of both nondualistic and monistic mysticism, and pluralistic mysticism integrates aspects of all three. This perspective preserves the possibility that a common unitive core may exist at every experiential layer.

2 Monistic Mysticism

The first layer, monistic mysticism, posits a single ultimate reality experienced as a profound awareness of unity with the cosmic consciousness. In this state, the distinction between perceiver and experience vanishes; awareness and experience merge into one. This form of mysticism transcends perceived reality by revealing the fundamental oneness of all existence and transforms the individual through the dissolution of selfhood. This section will first describe the philosophical tradition of perennialism, which emphasizes a universal principle underlying all traditions. Next, it will examine unitive mysticism and the common core thesis in psychology, which seeks to identify shared experiential elements across traditions. Following this, social constructionist critiques of the common core thesis and essentialism will be presented and addressed. Finally, a modified common core thesis will be introduced, balancing the universality of human psychological processes with cultural specificity.

2.1 Perennial Philosophy

This position finds its strongest advocate in what is known as the perennial philosophy, eloquently articulated by Aldous Huxley (Reference Huxley1945) as “the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man’s final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being – the thing is immemorial and universal” (p. 4). The origins of the perennial philosophy may be traced to the sixteenth century, when it emerged as a Renaissance vision of a primordial religion underlying all religions, subsequently expressed in diverse forms (Kripal, Reference Kripal2008). This constitutes the narrow sense of perennialism as the unification of beliefs and traditions.

The core assertion of perennialism is that truth is one, everywhere, and always the same. This universal truth underlies all religious and spiritual traditions, cutting across cultural boundaries. Ultimate reality is regarded as accessible to human consciousness through direct spiritual experience. In poetic terms, much like a perennial flower that blossoms year after year, truth is repeatedly unveiled to humanity. Without insisting upon surface-level similarities among traditions, perennialists argue that authentic revelations and practices have been providentially given to specific peoples, each sufficient for guiding humanity toward its ultimate end (Cutsinger, Reference Cutsinger1997).

Perennialism boasts a long and vibrant intellectual history, often celebrated as an unbroken continuity of thought. It includes authors who identify sublime principles – some transcendent source of all realities – as perennial (Faivre, Reference Faivre1994). Among them are ancient Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato; Hellenistic and early Christian thinkers like Ammonius Saccas and Origen; Gnostic and Neoplatonic figures such as Plotinus and Iamblichus; early Christian theologians like Dionysius the Areopagite and Augustine of Hippo; Renaissance thinkers such as Marsilio Ficino and Nicholas of Cusa; and Hermeticists like Paracelsus and Jacob Boehme. Contributions also come from medieval Islamic philosophers, Christian mystics, and Jewish Kabbalists, who will be discussed in Section 3 on nondualistic mysticism, while modern esotericists such as Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society will be considered in Section 4 on dualistic mysticism.

Several key twentieth-century figures are recognized as pioneers of the so-called traditionalist school, which revived and promoted perennial philosophy. Ananda Coomaraswamy (Reference Coomaraswamy1943), noted for his exploration of traditional metaphysics and symbolism in Eastern religions, sought to uncover a unifying core among seemingly disparate traditions. René Guénon (Reference Guénon1945), a French metaphysician, advocated a return to esoteric wisdom grounded in universal principles underlying all manifestation. His disciple Fritjof Schuon (Reference Schuon1953) further developed the notion of a transcendent unity of religions. A summary of perennialist writings, including extensive quotations from diverse religious and esoteric traditions, can be found in Perry (Reference Perry1981).

Yet the absolute and often dogmatic claims of perennial philosophy invite several criticisms. The foremost critique is the lack of evidence supporting the doctrine of the unity of all religions (Staal, Reference Staal1975). This doctrine appears to be a construct of a group of spiritual illuminati promoting a new religious movement aimed at unifying, or perhaps challenging, existing religions. A more pluralistic and context-sensitive approach to esotericism is therefore advocated, one grounded in historical, textual, and descriptive analysis rather than subsuming diverse traditions under a universal category (Huss, Reference Huss2020).

Another line of critique is that perennialism tends to mirror truths propagated by Western imperialism. For example, rather than urging reverence for the ongoing cycles of human and natural life or honoring the spirits of the land without ownership, perennialist truths often resemble a deistic framework familiar to Western civilizations. In other words, representations of the East are filtered through a lens of power serving imperial interests (Said, Reference Said1978). Systematic criticism of this perspective has emphasized that not all societies follow Europe’s developmental trajectory, and Europe is not essential for understanding non-Western experiences (Chakrabarty, Reference Chakrabarty2020).

Finally, a central tenet of perennial philosophy – that Truth and the Way precede life – requires acceptance of prescribed wisdom as the condition for a meaningful existence. Yet perennialism is not a pragmatic framework; mere assent to the doctrine of universality does little to improve daily life. As Nasr (Reference Nasr1981) argues, one cannot have immanence without transcendence: the transformative encounter with the divine is essential to perceiving the cosmos as theophany. Without such lived experience, the universal spiritual vision of perennial philosophy remains abstract and disconnected from practical human concerns.

2.2 Common Unitive Core

The pursuit of universal truth within perennial philosophy provides a foundation for the psychological study of unitive experiences. The claim that a common wisdom underlies diverse spiritual traditions suggests a phenomenological unity between perceiver and perceived reality. While unity is singular in essence, it manifests in distinct forms. One such form is extrovertive unity, in which the self merges with all things, perceiving reality in its totality without imposed categorization – a state encapsulated in Bucke’s (Reference Bucke1923) notion of cosmic consciousness. This entails an awareness of the cosmos as intrinsically alive and ordered, accompanied by a sense of eternal existence, as undying consciousness is experienced as already present. Another form is introvertive unity, which divides into two states: one with awareness and one without. In the awareness state, ego is not lost; the experiencer observes the experience and can recall it later, even when infused with a profound sense of nonself. Forman (Reference Forman1999) describes this as the pure consciousness state, an unchanging interior silence that coexists with intentional experience. By contrast, the no-awareness state occurs when, at the height of the experience, the experiencer is entirely unaware of its occurrence. Jones (Reference Jones1986) calls this depth mysticism, in which there is no direct apprehension of unity but rather an awareness that itself constitutes the experience. This form of unity closely parallels nondualist Vedanta, particularly the turiya state described in the Mandukya Upanishad (2–7), which transcends waking, dreaming, and deep sleep. Turiya is characterized as neither inward nor outward, ineffable, beyond duality, and defined by unwavering conviction in the oneness of self, causing the phenomenal world to dissolve.

These different types of unity are experiences rather than beliefs, untethered from specific content. This feature is crucial: when a person reports an experience of oneness – whether perceiving all things as part of the same whole or merging with all things – the object of unity remains unspecified, leaving interpretation open to cultural variation. A Neoplatonist may describe it as union with “the One”; an Eckhartian Christian may identify it with the Godhead; a Sufi may interpret it as Tawhid; and a Daoist may understand it as the Way. Yet despite these doctrinal differences, the pure experience of oneness recurs across mystical writings. This striking consistency led William James (Reference James1902), adopting radical empiricism, to conclude: “In Hinduism, in Neo-Platonism, in Sufism, in Christian Mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note” (p. 332).

Building on this observation, the common core thesis asserts that a universal experiential core exists across cultures and can be empirically identified (Hood, Reference Hood and McNamara2006). Hood’s 32-item Mysticism Scale (1975) operationalizes this core through three factors: an introvertive factor of ego loss and spatiotemporal transcendence; an extrovertive factor of unitive vision and the inner subjectivity of all beings; and an interpretive factor encompassing sacredness, bliss, noetic quality, and ineffability. In psychological studies, respondents rate the extent to which they have experienced these phenomena (e.g., for ego loss: “everything has disappeared from mind until you are conscious only of a void”). Factor analysis, which groups responses based on patterns of association, has shown that this three-factor structure holds across diverse religious and cultural contexts, including American Christians (Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Hood and Chen2019), Chinese Buddhist monastics (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Qi, Hood and Watson2011a), Chinese Christians and religious nones (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Hood and Watson2012), Iranian Muslims (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ghorbani, Watson and Aghababaei2013), and Tibetan Buddhists (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yang, Hood and Watson2011b). While studies using the Mysticism Scale evaluate whether the structural arrangement of mystical facets aligns with empirical data – without directly probing the specific content of experiences or the comparability of interpretations across traditions – the scale’s successful cross-cultural application suggests that unitive experience, though abstract and devoid of specific content, can nonetheless be meaningfully recognized across diverse cultural and linguistic contexts.

2.3 Criticism and Response

The common core thesis and monistic mysticism have been subject to sustained critique from social constructionism, which holds that reality emerges through cultural and linguistic processes and that observation is never entirely free of context. From this perspective, essentialist claims about mystical experience are undermined: the perception of unity does not correspond to an independent reality, and mysticism should not be treated as a discrete domain. Sharf (Reference Sharf and Taylor1998) and contributors to Katz’s edited volumes (Reference Katz1978, Reference Katz1992) reject the notion that mystical experiences are private, inner events existing apart from cultural frameworks. For Sharf, while experiences do occur, the very category of “experience” functions less as an objective reality than as an academic construct that legitimizes particular interests. In short, mysticism, according to constructionists, derives meaning from public discourse and shared cultural traditions rather than from experience itself.

On a more moderate level, mystical experiences are taken to be culturally conditioned narratives, rituals, and expressions rather than unmediated inner events. Thus, monistic mysticism cannot be detached from the traditions in which it is embedded (Katz, Reference Katz1978). The congruence of mystical experiences across traditions is rendered impossible by historical and cultural particularization (Proudfoot, Reference Proudfoot1985). Proudfoot further argues that beliefs and attitudes shape experience, rather than result from it, determining in advance what kinds of experiences are even possible. From this vantage point, mysticism differs fundamentally across traditions. Katz’s subsequent edited volumes situate mystical writings within their respective religious milieus (Katz, Reference Katz1983), align them with sacred scriptures (Katz, Reference Katz2000), and anthologize texts devoted to mystical doctrines and practices (Katz, Reference Katz2013). Covering Judaism, Christianity, Sufism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Native American spirituality, this body of scholarship underscores both the diversity of mystical content and the varied modes of its cultural expression.

Culture not only shapes experience but also governs how it is reported (Bharati, Reference Bharati1961). Mystical reports are never pure transcripts of experience; even Stace (Reference Stace1960) acknowledged that describing an experience inevitably entails interpretation. To address this, characteristics such as bliss, sacredness, noetic quality, and ineffability have been identified as complements to experience – aligned with it but conceptually distinct. Since mystical accounts reflect both felt states and cognitive appraisals, attempts to draw a strict boundary between description and interpretation must account for this overlap.

Methodologically, psychological scales have been criticized for constraining how mystical experience is reported. Predefined factorial structures, rigid question formats, and limited interpretive freedom risk overlooking dimensions of experience not anticipated by the instruments (Belzen, Reference Belzen2009). While self-report remains the dominant method, its validity is uncertain, since it is often unclear whether respondents describe heightened emotion or a mystical state (Greeley, Reference Greeley1975). These philosophical and methodological challenges continue to cast doubt on a monistic common core, even as empirical assessments have identified it across cultures.

Yet the claim that mysticism is nothing more than a cultural construct neglects neurological evidence. Monistic mysticism has been linked to decreased activity in the posterior parietal cortex, which governs spatial awareness and self-other differentiation (Newberg, Reference Newberg2018). This reduction correlates with reported unity and transcendence. Likewise, disrupted connectivity within the default mode network (DMN) – including the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, posterior parietal cortex, and temporal regions – has been associated with reported experience of ego dissolution (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Subramanian and Perry2024). Research on psilocybin and LSD similarly shows significant decreases in activity and connectivity in connector hubs of the brain, facilitating unconstrained cognition (Carhart-Harris et al., Reference Carhart-Harris, Erritzoe and Williams2012, Reference Carhart-Harris, Muthukumaraswamy and Roseman2016). These decouplings strongly correlate with reports of ego dissolution and altered meaning, highlighting the role of neural circuitry in sustaining selfhood. Long-term contemplative practice also leaves structural traces, such as increased gray matter density in regions tied to emotional regulation and cognitive control (Goleman & Davidson, Reference Goleman and Davidson2018). Still, as Sarter et al. (Reference Sarter, Berntson and Cacioppo1996) caution, neural activity does not correspond one-to-one with experience; brain activity alone cannot explain experience.

While culture shapes mystical expression, one could argue the reverse: that universal principles precede cultural variation. Guinn (1997) contends that sacred principles determine culture rather than merely arise from it. As these principles move from the essential to the substantial – from the principial to the cultural – variations of expression emerge, giving rise to the diversity of traditions. At this level, only motifs or essential principles remain universally recognizable (Campbell, Reference Campbell1949). Moreover, cultural context does not entirely determine the content of mysticism. Many experiences incorporate elements unfamiliar to the individual’s religious background, challenging the view that they are wholly constructed (Almond, Reference Almond1982).

An experience detached from its cultural context may lose some of its interpretive depth, yet this does not invalidate the experience itself. Mystical experiences are authentic psychological phenomena that have been systematically studied in real-time using methods such as autogenic training (Albrecht, Reference Albrecht and Woehrer2019). Another critique maintains that if language shapes experience, then ineffable states cannot be genuine experiences. Paper (Reference Paper2004) responds: “While it may be logically impossible for me to have had an ineffable experience – ineffable even to myself – for me it remains a fact that I did indeed have it. Thus, I must either give up on myself or formal logic; my own personal choice I trust is obvious” (p. 55).

Individual construction undeniably plays a role, but at a more fundamental level than social constructivist critiques allow. Belief sets the boundaries of what realities one can access. As the aphorism goes: “For those who believe in God, no explanation is necessary. For those who do not believe in God, no explanation is possible.” This ontological divide is exemplified by those who reject dominant normative frameworks in favor of alternative realities, as seen among perennialist commitments. Jung (Reference Jung1953) directly addresses this ontological divide within religious experience, though it could equally apply to mysticism in general: “Religious experience is absolute; it cannot be disputed. You can only say that you have never had such an experience, whereupon your opponent will reply: ‘Sorry, I have.’ And there your discussion will come to an end” (p. 167). Believers, then, do not speak merely of what they believe, but of what they know to be true – both of reality and of themselves (Jones, Reference Jones1986).

2.4 Modified Common Core Thesis

These considerations led to a modified common core thesis – one that acknowledges cultural differences while still assessing universality (Chen, Reference Chen, Yaden and van Elk2025). First, the empirically identifiable cluster of mystical experiences does not entail a shared set of higher-order beliefs or practices, as posited by perennial philosophy, nor does it authorize the supremacy of one belief system over another. Moreover, these mystical characteristics do not exhaustively encapsulate private experience, since borderline cases exist where episodes only partially conform to the core features. The common core thesis thus maintains that a unity at the phenomenal level underlies the diversity of religious dogmas and concepts, which emerge as secondary constructs.

Second, reconciliation between the common core thesis and social constructivism may be found in the view that individual beliefs enrich rather than replace mystical experience (Smart, Reference Smart1965). From this perspective, interpretive systems reshape experiences into culturally intelligible forms. A mediating position holds that mystical experience involves a fundamental transformation of consciousness that transcends doctrinal distinctions, yet its expression remains deeply embedded within particular traditions (Studstill, Reference Studstill2005). Parsons (Reference Parsons, Cattoi and Odorisio2018) further argues that mysticism is best studied not in sweeping generalizations but case by case. Precisely because a transcendental core exists, variation in expression acquires comparative significance, reinforcing the claim that “humans are vastly different, with just enough commonalities to enable discourse and empathy” (Parsons, Reference Parsons, Cattoi and Odorisio2018, p. 146). At its most abstract and contentless level, monistic mysticism functions as a conceptual bridge, integrating diverse expressions across traditions.

Third, qualitative research complements quantitative studies by probing the content of mystical experiences and capturing phenomena beyond predefined categories. Semi-structured interviews designed to elicit the substance of mystical experience reveal a broader spectrum of experiential types than those typically identified in quantitative models. Some align closely with doctrinal frameworks. For instance, in a study with 139 Chinese Pure Land and Chan Buddhist monks and nuns, participants described the dissolution of selfhood not merely as consciousness of a void but as an intricate state of zhenkong miaoyou – “wondrous existence in true emptiness” (Chen et al., 2011). In another study with individuals in soulmate relationships, participants reported profound, self-effacing connections that extended beyond explicitly religious contexts (Chen & Patel, Reference Chen and Patel2021). In a study with nineteen Daoist monastics, ego dissolution was interpreted through bodily sensations, such as the perception of energy movements (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo and Cowden2023). In a study with sixty-one trained shamans in North America, mysticism was understood as a fundamental shift in their perception of reality itself within the framework of Shamanic healing (Chen, Reference Chen2023). More recently, in a study with thirty-nine Daoist monastics, mixed-methods and network analysis were used to examine the structure of their experiences, thereby refining the common core thesis within a less-studied tradition (Chen & Guo, Reference Chen and Guo2025).

In sum, both theoretical argument and empirical evidence support the existence of a common experiential core of monistic mysticism, while allowing for variability in interpretive organization across traditions. Subtle differences emerge among samples from distinct religions, yet certain facets consistently define unitive mysticism, producing what Wittgenstein (Reference Wittgenstein1953) termed a “family resemblance” across traditions. This challenges the classical notion that all members of a category share a single essential feature. Instead, categories are linked by overlapping similarities, much like resemblances among family members who may share certain traits without any one being universally present. The modified common core thesis therefore, rests on three key elements: a universal experiential core at the facet level (e.g., ego loss), socially constructed variability at the factor level (e.g., introvertive factor), and stable family resemblances across cultural contexts. While monistic mysticism provides a valuable framework for understanding certain shared psychological phenomena, it has become increasingly evident that mysticism as a whole encompasses multiple forms of perceived reality, with ego dissolution representing but one among many possible configurations of selfhood.

3 Nondualistic Mysticism

The second layer, nondualistic mysticism, acknowledges the apparent duality and hierarchy between subject (e.g., the created, mundane existence) and object (e.g., a deity, God, or the cosmic order), while emphasizing the possibility that the created may ultimately become one with the Creator. It frequently takes the form of a numinous experience in which the world and humanity are perceived as imperfect reflections of an ultimate reality. Within this framework, mystical experiences often pursue detachment from the material and transient in order to return to the divine source – where unity with the divine is fully realized and the distinction between the created and the Creator dissolves. Nondualistic mysticism thus aligns with our definition of mysticism by affirming the existence of a transcendent reality beyond the mundane world and by requiring the subjugation of the individual self to an idealized manifestation of the divine. This form of mysticism incorporates a pursuit of universal principles inherent in monistic mysticism, insofar as many religious traditions strive for communion and oneness with ultimate reality. Yet it extends beyond monistic mysticism by recognizing that the individual is inherently distinct from the divine, such that the ultimate unity of the two is not assured or automatic.

Each religious tradition articulates its mystical experiences through distinct theological and philosophical languages, reflecting the uniqueness of its worldview. Determining the extent to which traditions converge on a shared mystical essence remains a significant challenge, precisely because of these differences. The following sections examine mystical thought within several major religious traditions as an entry point into deeper study. It is evident that such traditions cannot be neatly summed up, and what is presented here constitutes only approximations rather than exhaustive or axiomatic descriptions, leaving room for many exceptions. The section organizes these traditions according to their historical origins. The Abrahamic traditions, or People of the Book – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – each develop distinctive mystical frameworks rooted in their monotheistic foundations. The Dharmic religions of Hinduism and Buddhism arise in India, with Buddhism extending beyond its homeland to take root in other cultures. In addition, two Chinese traditions, Daoism and Confucianism, are considered, offering perspectives that move outside a strictly monotheistic or theistic paradigm. The section concludes with a comparative discussion that reflects on the idea of “a religion of all religions” as a lens through which mysticism across traditions might be approached.

3.1 Abrahamic: Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Mysticism

3.1.1 Jewish Mysticism

Jewish mysticism is the pursuit of direct, experiential knowledge of God (Scholem, Reference Scholem1961), employing specific spiritual techniques to attain the unitive experience (Idel, Reference Idel1988). In contrast to philosophical Judaism’s emphasis on rationalism and abstraction, Jewish mysticism arises from a profound yearning to identify with the innermost divine essence of all things. Both the surface meaning, nigleh – the revealed aspect of an act or text, as exemplified in Jewish law and the Talmud – and the hidden matter, nistar – the mystical teachings of the Torah – are central to this mystical orientation. Jewish mysticism, therefore, entails the removal of outer coverings in order to disclose the inner quality of things (Weiner, Reference Weiner1969). Across history, Jewish spiritual thought and practice have developed through several distinct stages. The biblical period, particularly the book of Genesis, provides paradigmatic expressions of mystical doctrine and phenomena. The rabbinical era gave rise to Merkavah and Hekhalot mysticism, followed in the medieval period by the emergence of Kabbalah and, later, the flowering of Hasidism (Green, Reference Green1987). Scholem (Reference Scholem1987) traces the origins of Kabbalah in twelfth-century Southern Europe to the text of the Bahir, culminating in the composition of the Zohar.

Several hallmarks define Jewish mysticism. A first is the perennial spiritual belief that “as above, so below,” signifying a correspondence between divine order and mundane existence. Creation itself is understood as a process of divine emanation through the Sefirot, ten channels mediating between the physical world and Ein Sof – the infinite, unknowable aspect of God that transcends human comprehension (Idel, Reference Idel1988). This dynamic interplay between heavenly power and earthly existence unfolds in two contrasting mystical models: the anabatic ascent, in which the mystic rises upward to bring down divine power, and the katabatic descent, wherein Messiahs enter into the realm of evil to redeem fallen souls (Idel, Reference Idel and Katz2013).

Another defining feature is the emphasis on action. For the Jewish mystic, mystical union requires the performance of precise rituals, rather than a passive reception of divine grace, as is often the case in Christianity. In this respect, Jewish mysticism shares with Hindu mysticism an emphasis on ritual, on its cosmic effects, and on the use of breathing techniques to induce altered states of consciousness (Idel, Reference Idel and Katz2013). This emphasis is further accentuated by the insistence on precision in mystical techniques – whether ecstatic, theurgical, or talismanic (Idel, Reference Idel1995) – since their efficacy depends on meticulous execution. Moreover, many of these practices are not regarded as mere human inventions but as divine revelations, reinforcing nomianism, or strict adherence to divine commandments, as central to religious faith and practice.

Finally, as in many other mystical traditions, Jewish mysticism often embraces paradox. The supreme, most sacred spiritual reality is ineffable, and God remains ultimately beyond human comprehension (Idel, Reference Idel1995). Because Jewish theology preserves the fundamental distinction between Creator and creation, mystical self-loss or merging with the divine is exceedingly rare. As Scholem (Reference Scholem1961, pp. 122–123) observes, “It is only in extremely rare cases that ecstasy signifies actual union with God, in which the individuality abandons itself to the rapture of complete submersion in the divine stream. Even in this ecstatic frame of mind, the Jewish mystic almost invariably retains a sense of the distance between the Creator and His creature.” This paradox – the simultaneous longing for and impossibility of full union – may account for the Jewish mystic’s intense focus on text (Torah) and language (Hebrew). The Hebrew language and alphabet are considered sacred, serving as direct expressions of divine thought. Jewish mysticism extends beyond the meaning of words to the very form of letters themselves, inspiring spiritual techniques such as gematria, in which numerical values are assigned to words to uncover hidden connections. Through the practice of gematria, the mystic undergoes a psychological shift that enables a closer approach to divine reality.

3.1.2 Christian Mysticism

Rather than “mystical union,” Christian mysticism is better described as beliefs and practices centered on the direct “presence of God.” In his magnum opus, McGinn argues that mystics seek to understand and live daily life in God’s presence. His historical survey of Christian mysticism begins with its origins through the fifth century (McGinn, Reference McGinn1991) and extends to quietism in seventeenth-century southern Europe (McGinn, Reference McGinn2021). Additionally, McGinn (Reference McGinn2006) has edited key writings on Christian mysticism, providing firsthand accounts and annotations that highlight mysticism as a transformative encounter with God’s presence rather than an abstract theological concept.

The emphasis on experience was not widespread in early Christianity. Before the twelfth century, monastic mystics rarely spoke of personal encounters with God, instead expressing mystical transformation through biblical exegesis. With Bernard of Clairvaux, active in the first half of the twelfth century, personal experience became more pronounced, culminating in what McGinn (Reference McGinn1998) calls the “flowering of mysticism” through the sixteenth century. Figures like Meister Eckhart (Reference Eckhart2009) preached the unity of the soul with the divine, famously stating, “The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me: my eye and God’s eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, and one love” (Sermon 57, p. 298). Similarly, Teresa of Ávila (Reference Kavanaugh and Rodriguez1979) described her spiritual journey through the metaphor of an inner castle with seven mansions, representing stages of growth and intimacy with God. At its core lies the innermost chamber, where God resides and where the ultimate Spiritual Marriage occurs.

McGinn (Reference McGinn and Katz2013) outlines three key characteristics of Christian mysticism. First, orthodoxy holds greater importance than orthopraxy. The doctrines of the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) and Jesus Christ as the Messiah distinguish Christian mysticism from other Abrahamic traditions, despite the diversity of Christological interpretations within it. Second, Christian mysticism emphasizes action. The balance between mystical experience and its visible effects is framed as the relationship between contemplation and active love. Charity is often seen as more vital to the Church than personal ecstasy. The highest mystical goal is to achieve a state where one actively loves in the midst of contemplation, exemplified by Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Jesuits. Finally, Christian mysticism is communal. While individuals prepare for union with God through mystical teachings, this experience often occurs within the Church’s communal life – through biblical reading, liturgy, sacraments, prayer, and preaching. The knowledge gained through mysticism is considered a divine gift, meant not for personal enlightenment alone but for the service of the Church through teaching, intercession, and healing.

3.1.3 Islamic Mysticism

Islamic mysticism is most often expressed in the form of tasawwuf or Sufism, which is rooted in the Qur’an and Sunnah. Central to Sufi thought are the principles of tawhid (divine unity), the transformative power of dhikr (remembrance of God), and the integration of inner virtues with outward practices modeled on the life of the Prophet Muhammad (Nasr, Reference Nasr1991). Within the Sufi framework, three interrelated concepts structure the mystical path: shariah, the code of conduct that governs Muslim life; haqiqah, the knowledge of ultimate reality attained through communion with God; and tariqah, the path that bridges the exoteric shariah with the esoteric haqiqah. These three form a symbolic architecture: shariah as the circumference, haqiqah as the center, and tariqah as the radii connecting the two (Guenon, Reference Guénon and Herlihy2009). In this vision, external observance, inner realization, and the spiritual path remain inseparable dimensions of mystical life.

The principle of tawhid, or the oneness of God, stands at the very heart of Islamic mysticism. Yet Sufis have historically offered diverse interpretations of how this unity should be approached and to what extent the human being can draw near to God (Fakhry, Reference Fakhry2004). Neoplatonic philosophers such as al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and Ibn Bajjah emphasized reason and intellectual contemplation as the primary means of comprehending God, advancing the human intellect as a path toward divine knowledge. By contrast, early Sufi figures such as Junayd of Baghdad and later al-Ghazali articulated a more dualistic vision in which God is approached through awe, reverence, and love, yet without intimacy or identification. In more radical voices, such as al-Hallaj and al-Bastami, this boundary dissolved, leading to bold proclamations of identity with the divine. Rumi, meanwhile, celebrated the transformative power of love, music, poetry, and dance, emphasizing the ecstatic dimensions of mystical union (Lewis, Reference Lewis2000). Expanding upon these currents, Ibn Arabi articulated a sweeping metaphysical system in which all differences and otherness are dissolved in God, positing creation as nothing other than the Creator’s self-disclosure. Since Ibn Arabi, the path to true gnosis has often been conceived as a progression from the illusion of separateness to the realization that all existence is one with the Divine (Awn, Reference Awn and Katz2013).

Although the unity of God ultimately eludes empirical verification and rational demonstration, it may nonetheless be discerned through layers of manifestation, each of which serves as a sign of divine oneness (Schimmel, Reference Schimmel1994). One way in which these signs are recognized is through the cultivation of the creative imagination, particularly through meditation and contemplative practice. Such exercises allow the seeker to perceive unity beneath the multiplicity of the world, thereby recognizing creation as an interconnected field of divine self-disclosure. It is in this light that Ibn Arabi develops the notion of the alam al-mithal, or the Imaginal World, an intermediate realm where spiritual realities assume symbolic forms and physical realities become spiritualized. In this realm, divine energies manifest in ways accessible to human perception, while never losing their essential transcendence. Imagination thus becomes not a faculty of idle fantasy but a bridge between thought and being, a means of accessing divine realities directly and facilitating the soul’s ascent toward union with God (Corbin, Reference Corbin1969).

3.2 Dharmic: Hindu and Buddhist Mysticism

3.2.1 Hindu Mysticism

One classical way to understand the progression of Hindu mysticism is as a journey from the Vedas to the Upanishads, and finally through the Bhagavad Gita. The journey begins with the vision of the four Vedas, emphasizing cosmic unity and divine order, followed by an exploration of sacrifice and ritual as a means of connecting with the divine. The Upanishadic quest deepens this inquiry, seeking ultimate reality (Brahman) and self-realization (atman), while the Bhagavad Gita integrates devotion (bhakti yoga), knowledge (jnana yoga), and action (karma yoga) into a comprehensive spiritual path. Yoga, meaning “to yoke” or “to unite,” in its narrow sense refers to the Yoga school – one of the six orthodox systems of Hindu philosophy – which developed with relative independence from the other traditions and could thus be flexibly absorbed into diverse mystical practices. More broadly, yoga encompasses any spiritual discipline – meditation, breath control, concentration – that unites the seeker with their ultimate quest for liberation (Eliade, Reference Eliade1958). The richness of Hindu philosophies is often expressed through myths and symbols, employing motifs such as the lotus, wheel, and serpent to articulate truths otherwise beyond expression (Zimmer, Reference Zimmer1946).

Hindu mysticism may be traced across several overlapping phases (Sharma, Reference Sharma and Katz2013). The earliest form, sometimes called acosmic mysticism, involves direct illumination without deity worship, exemplified by Samkhya and classical Yoga. Lacking a clear conception of God, the yogin does not seek personal union with a divine presence but rather the realization of the self in its pure, isolated state, freed from the entanglements of material nature. A subsequent phase of theistic mysticism emerges with figures such as Ramanuja and Madhva, who affirm Brahman as both the indwelling ground of the universe and the source of all souls. For Ramanuja, Brahman is the immanent reality in which human souls and the cosmos exist as the body of God, yet remain distinct, wholly dependent on Him for their being. Parallel to these developments, the bhakti tradition expands the mystical landscape through devotional paths centered on personal, relational encounters with God, expressed through love, surrender, and ecstatic union with saguna (qualified, personal) Brahman. This devotional current crystallized around deities such as Krishna, Shiva, and the Goddess, and profoundly shaped the emotional and communal dimensions of mystical life in Hinduism.

Finally, absolutist mysticism, most forcefully articulated by Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta, “the end of the Vedas,” interprets the Upanishads as teaching that Brahman is without attributes (nirguna), infinite, and the sole truth of existence (Sivaraman, Reference Sivaraman1989). In this view, bondage (samsara) and liberation (moksha) are mere illusions born of ignorance, since the atman is ever one with Brahman. Yet Advaita also recognizes the provisional significance of saguna Brahman, the personal God, as an object of worship and meditation, preparing aspirants for the eventual realization of formless nirguna Brahman. Shankara (Reference Shankara, Prabhavananda and Isherwood1947) thus states, “How can one imagine duality in Brahman, which is entire like the ether, without a second, the supreme reality? There is neither birth nor death, neither bound nor aspiring soul, neither liberated soul nor seeker after liberation – this is the ultimate and absolute truth” (p. 115). Another significant strand is Tantric mysticism, which arose in medieval India and emphasized ritual, mantra, subtle-body practices, and the harnessing of divine energy (shakti) to achieve transcendence. Unlike the renunciatory tendencies of classical Advaita, Tantra often affirms the sacredness of the body and the dynamic, creative power of the divine manifest in material existence. Modern figures such as Ramakrishna (Nikhilananda, Reference Nikhilananda1942) and Sri Aurobindo (Reference Aurobindo1990), who have both influenced and been influenced by the West, further elucidated left-handed and right-handed Tantra – integrating the erotic and mystical – and transforming ritual practices into internal contemplative exercises.

Across these mystical traditions, Hinduism emphasizes right action (orthopraxy) rather than right belief (orthodoxy), in contrast to Christian mysticism. A Hindu must fulfill their varnasrama dharma – duty (dharma) determined by caste (varna) and stage of life (ashrama). Thus, Hinduism’s ritual precision and caste-based restrictions stand in stark contrast to its doctrinal inclusivity, accommodating nontheism, theism, absolutism, and syncretism (Zimmer, Reference Zimmer1951). By contrast, Jainism and Buddhism reverse the emphasis: while Hinduism prescribes worldly duty under Brahmanic supervision, Jain and Buddhist traditions champion renunciation, as exemplified in the figures of Mahavira and the Buddha (Dumont, Reference Dumont1975).

In yoga, a dialectical tension exists between effort and surrender. Terms such as vitarka (inquiry) and vicara (analysis) indicate a mind engaged in self-examination. At first, this deliberation directs attention to the movements of thought; later, in advanced meditation, such cognitive activity dissolves into an unbroken flow of awareness. The Yoga Sutra teaches that this state is not achieved by forceful suppression or overanalyzing thoughts – which merely introduce new waves of mental activity – but through detachment (Staal, Reference Staal1975). This paradox is often misunderstood, leading some to misinterpret yoga as passive or inactive. On the contrary, the true yogin is vigorous, disciplined, and engaged, possibly even while living fully within the world.

3.2.2 Buddhist Mysticism

The Upanishads, especially the Chandogya, frame spiritual experience in terms of union, affirming the nonduality of Atman and Brahman. In contrast, Buddhism emphasizes shunyata – emptiness or nothingness – wherein the self dissolves into the nullity of all things (Paper, Reference Paper2004). Among the most influential philosophical traditions is Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka (Middle Way), which profoundly shaped Buddhist thought and later became foundational for many tantric systems (Zimmer, Reference Zimmer1951). The earliest transmission of Indian Buddhism to Sri Lanka and later Southeast Asia gave rise to Theravada, a tradition that stresses mindfulness, monastic discipline, and ethical living as the basis for liberation (Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi1993). The foundational teachings of the Buddha, preserved in the Pali Canon, remain central to this tradition (Bhikkhu Bodhi, Reference Bodhi2005). Even earlier, in the Tibetan cultural sphere, the indigenous Zhangzhung Bön religion flourished, and while it later absorbed Buddhist elements, its mystical corpus exhibits less reliance on Hindu tantric influences than Vajrayana Buddhism (Norbu, Reference Norbu2013).

Buddhism entered China in the first century ce, where it encountered Daoism and Confucianism, giving rise to distinctive East Asian forms of Mahayana (Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi1999). Chinese Chan (later Zen in Japan) emphasized the immediacy of awakening and practical enlightenment integrated into daily life. This syncretic spirit extended into Korea, where Buddhism blended with indigenous shamanic beliefs, and into Japan, where Zen and Pure Land practices developed into highly distinct currents. A central feature of Zen is the seamless integration of spiritual realization and practical activity, embodied in the Japanese concept of satori (enlightenment). Satori represents a sudden, transformative experience of oneness and spontaneity, in which the duality between self and world dissolves. Zen masters often described this as the essence of spirituality itself: an uncompromising engagement with the immediacy of life. The Japanese term myo (Chinese: miao) conveys this ineffable quality, denoting “a mode of activity which comes directly out of one’s inmost self without being intercepted by the dichotomous intellect” (Suzuki, Reference Suzuki1959, p. 140).

Buddhism formally entered Tibet in the eighth century, where it developed into Vajrayana, the “Diamond Vehicle.” Vajrayana emphasizes the transformative power of tantra (tantra in Sanskrit meaning “thread” or “weaving”), while in Tibet the term gyud (continuum) reflects the recognition of an inherent Buddha-nature present in all beings (Blofeld, Reference Blofeld1970). Vajrayana is characterized by its elaborate system of nine vehicles (yanas), each providing progressive methods toward enlightenment (Dudjom Rinpoche, Reference Rinpoche and Dorje1991). Entry into tantric practice requires initiation by a qualified guru through ritual empowerments (dbang), and unwavering devotion to the teacher is considered indispensable. The guru is often perceived as an embodiment of enlightenment itself, capable of awakening the disciple through direct transmission, “like a lamp lighting another lamp.” A classical account of these foundations is found in The Words of My Perfect Teacher (Kunzang Lama, Reference Lama1993).

Tantric practice proceeds in two major stages. In the Generation Stage, practitioners cultivate deity visualization, transforming ordinary perception into awakened vision. By visualizing oneself as a deity (yidam) and inhabiting its enlightened qualities, the yogin integrates body, speech, and mind with the divine archetype, aided by mantras, mandalas, and ritual symbolism. The celebrated mantra Om Mani Padme Hum epitomizes this devotional and transformative practice (Govinda, Reference Govinda1969). In the Completion Stage, practitioners engage in subtle-body yogas, manipulating vital winds (tsa lung) and cultivating inner heat (tummo) to deepen realization and directly experience the nature of mind (Blofeld, Reference Blofeld1970).

As the pinnacle of the Nyingma school’s teachings, Dzogchen (“Great Perfection”) emphasizes direct recognition of the mind’s true nature (rigpa). Dudjom Lingpa’s visionary teachings describe awareness as inherently pure (kadag) and spontaneously present (lhun grub), transcending conceptual elaboration. Dzogchen practice involves meditative absorption, self-liberation from mental obscurations, and cultivating nondual awareness, revealing the natural state of primordial consciousness (Wallace, Reference Wallace2015).

In Vajrayana, mystical transmission often unfolds through esoteric revelation. Teachings may be concealed by enlightened beings and later rediscovered by visionary masters known as tertons (treasure revealers). These revealed texts, or terma, often appear in visions, dreams, or meditative states, ensuring the continuity of wisdom across generations (Gyatso, Reference Gyatso1998). Such transmissions are sometimes linked to subtle-body channels, resonating with Daoist internal alchemy and tantric physiology. In this way, Buddhist mysticism situates the individual within a vast temporal and cosmic continuum, in which liberation unfolds across lifetimes, mediated by direct transmissions of wisdom and the recognition of the luminous, nondual nature of reality.

3.3 Chinese: Daoist and Confucian Mysticism

3.3.1 Daoist Mysticism

Grounded in Chinese cosmology, which posits the oneness of the universe and its natural rhythms, the Daoist mystical endeavor seeks not only to restore cosmic harmony but also to attain realization – to “make heaven and earth his body” (Kohn, Reference Kohn and Katz2013). One of the core Daoist mystical ideals is tranquility and nonaction (wuwei). However, wuwei is not passive acceptance; rather, it arises through profound mystical cultivation, aligning an individual with the rhythms of the cosmos. Early Daoists – Laozi and Zhuangzi – through specific practices such as sitting in oblivion (zuowang), may have achieved a transformation in which the self dissolves into a unitive mystical experience of merging with the Way (Dao). Following this transcendence, when adepts return to worldly engagement, their consciousness is radically transformed, allowing them to “do nothing yet leave nothing undone” (wuwei er wubuwei). This suggests that original Daoism may have consisted of one or more master-disciple lineages centered on the contemplative practice of inner cultivation. This practice formed the distinctive techniques (shu) around which these lineages coalesced and from which they ultimately derived their identities (Roth, Reference Roth2021).

Beyond this deeply abstract ideal of unity with the Dao, Daoism’s unique spiritual insight lies in its equal emphasis on body and spirit as integral to spiritual transformation. Foundational to Daoist thought is the concept of qi – the vital energy that flows through the body’s meridians, akin to blood circulating through the veins. This focus on the body originated in early Daoist external alchemy, where practitioners sought physical immortality through elixirs composed of minerals and medicinal herbs. By the sixth century, the emphasis shifted inward, giving rise to internal alchemy (neidan), wherein the body itself became the locus of spiritual transformation. The cultivation of the three treasures – jing (essence), qi (vital energy), and shen (spirit) – became central to this practice. Zhang Boduan, founder of the Southern Neidan School, outlined a three-stage process in his Wuzhen Pian (“Awakening to Reality”; Pregadio, Reference Pregadio2009): refining jing into qi, refining qi into shen, and refining shen to return to primordial emptiness. This interplay between jing and qi sustains life (ming), while shen defines one’s spiritual nature (xing). Wang Chongyang, founder of the Northern Quanzhen School, articulated this dynamic in the 11th discourse of his Fifteen Discourses to Establish the Teachings: “Spiritual nature (xing) is spirit (shen); life (ming) is qi. Spirit and life intertwine, like a bird riding the wind.”

Given the essential role of bodily energies, Daoism emphasizes the joint cultivation of body and spirit – xing ming shuangxiu. Cultivating ming entails nurturing qi through breathing exercises, meditation, and a tranquil lifestyle, while cultivating xing involves aligning oneself with the Dao, fostering inner harmony, and refining the mind and spirit. The philosophy of xing ming shuangxiu rests on the equilibrium between these two aspects, as Daoists maintain that physical life (ming) and spiritual nature (xing) are interdependent. Practices that cultivate both spirit and body are indispensable for harmonizing with the Dao and, ultimately, for achieving immortality (Kohn, Reference Kohn1993).

3.3.2 Confucian Mysticism

Confucian ideals align closely with Daoist thought in their shared focus on xing (spiritual nature) and Dao (the Way). The Confucian canon, Zhongyong (“Doctrine of the Mean”), begins by stating: “What Heaven has conferred upon people is called spiritual nature; to follow this nature is called the Way; and aligning one’s nature with the Way is called self-cultivation.” This mystical process of self-cultivation (xiushen) fosters a deep connection with others, nature, and Heaven, as illustrated in Daxue (“The Greater Learning”): a cultivated self leads to the regulation of the family, which in turn enables the governance of the state and ultimately the harmonization of everything under Heaven.

The goal of self-cultivation is twofold. From a pragmatic perspective, it culminates in the ideal of the “inner sage, outer king” (neisheng waiwang), wherein the cultivation of personal virtue, wisdom, and moral character enables one to govern society and lead others effectively (Zhang, Reference Zhang2009). On a higher level, it aspires toward the “unity of Heaven and humanity” (tianren heyi), reflecting the profound interconnectedness between humans and the cosmos. This mystical ideal is realized through the alignment of human nature with the cosmic order, achieved via self-cultivation and moral virtuosity (Kohn, Reference Kohn and Katz2013).