Introduction

Mega-events such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games (the Olympics) and FIFA World Cup involve large volunteer programmes in their delivery (Cuskelly et al., Reference Cuskelly, Fredline, Kim, Barry and Kappelides2021). Volunteers are always acknowledged as part of the success of these events, although the “unsung heroes” tag has become somewhat clichéd as event organisers and politicians widely praise the contributions of these visible voluntary workforces. To mark International Volunteer Day in 2019, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) called volunteers the “heartbeat” of Olympic legacy (IOC, 2019). This recognition of volunteers beyond event delivery reflects that these episodic volunteer programmes have increasingly been incorporated into the rhetoric around event legacies (Lockstone-Binney et al., Reference Lockstone-Binney, Holmes, Smith and Shipway2018). The IOC defines event legacies as the “tangible and intangible long-term benefits for people, cities/territories and the Olympic Movement” (2017, p. 13) and this definition is broadly followed by other mega-events.

Globally, in Western countries, volunteer rates have been steadily declining, signalling movement towards more individualistic and less socially cohesive communities (Guidi, Reference Guidi2022), yet mega-events continually attract large numbers of volunteers. For example, the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games received 204,000 applications for approximately 80,000 volunteer places (Cuskelly et al., Reference Cuskelly, Fredline, Kim, Barry and Kappelides2021), although concerns about Covid-19 led to a high attrition rate. Volunteers have become a cornerstone of the Olympics delivery landscape, the absence of whom would have adverse consequences to the budget and delivery of these and other mega-events. Hosting an Olympic Games may also impact on sustaining volunteering organisations and programmes post-event. Research has focused on volunteering legacy to chart whether volunteers continue to volunteer post-event (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Wolf, Lockstone-Binney, Smith, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Baum2014), with little evidence of changes in volunteering participation longer term. However, the structural benefits for the host city from training large numbers of volunteers remain unexplored, nor has there been deep exploration into the systems established that could benefit existing volunteer-involving organisations within host communities (Shipway et al., Reference Shipway, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Smith2020a).

The primary research question addressed here is the extent to which a post-event volunteering legacy is facilitated by event organising committees leveraging existing volunteering infrastructure in host communities. Volunteering infrastructure is defined as the organisations and programmes in place to promote, support and manage volunteers, including volunteering peak bodies, volunteer resource centres, national governing bodies of sport, community and third sector organisations, and government (Lockstone-Binney et al., Reference Lockstone-Binney, Holmes, Smith and Shipway2018). Currently, there is limited evidence as to the extent to which mega-event organising committees engage with key stakeholders to drive legacy outcomes (Leopkey & Parent, Reference Leopkey and Parent2017). This paper uses case studies of the Sydney 2000 and London 2012 Olympic Games (hereafter referred to as “Sydney 2000” and “London 2012” respectively) to explore host city specific nuances in legacy delivery. These case studies were selected because of their similarities and differences, enabling comparisons, and because of ready access to data.

Regulatory capitalism (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur and Drahos2017) is used as a critical lens to assess the efficacy of legacy generation efforts given its increasing applicability to mega-events delivered in Western democracies (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Nichols and Ralston2018). To understand the context of mega-event volunteering and its potential scope for realising a volunteering legacy, this is firstly situated in the preceding literature review on event and episodic volunteering.

Literature Review

Episodic Volunteering and Mega-events

Episodic volunteering refers to one-off or occasional volunteering assignments that offer a flexible relationship with an organisation (Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Meijs, Brudney, Hersberger-Langloh, Okada and Abu-Rumman2022). Most event volunteering opportunities, which by their very nature are short-term and infrequent, can be classed as episodic. Mega-event volunteering, such at the Olympics, is an extreme form of episodic volunteering given its “once-in-a-lifetime” nature (Koutrou et al., Reference Koutrou, Pappous and Johnson2016), driven by the global rotations of these mega-events.

Despite recognition of episodic volunteering as an emerging trend over 30 years ago, there remains a dearth of empirical studies examining the phenomenon (Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Meijs, Brudney, Hersberger-Langloh, Okada and Abu-Rumman2022; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Bax and Chambers2016) and a lack of appropriate models for managing episodic volunteers (Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Heist and Storti2017; Maas et al., Reference Maas, Meijs and Brudney2021). We concur with Cnaan et al. (Reference Cnaan, Heist and Storti2017) that extant knowledge on episodic volunteering is contained in two streams, which rarely consider each other: (1) volunteering and non-profit journals and (2) sport and leisure journals, to which we add the emerging event management field. We seek to merge learnings from both streams to underpin this paper and deliberately adopt the event-context language of “volunteering legacies” to capture what non-profit volunteering researchers might alternatively refer to as sustained or repeat volunteering.

Cnaan et al. (Reference Cnaan, Meijs, Brudney, Hersberger-Langloh, Okada and Abu-Rumman2022, p. 416) contend that episodic volunteering in the event context “lacks the sustainability to change society” and that episodic volunteers are more independent compared to traditional volunteers. The nature of episodic event volunteering means that the arrangements between the organisation and volunteer are more tenuous and timebound with limited scope to make on-site adjustments to management practices once the event is up and running (Maas et al., Reference Maas, Meijs and Brudney2021). Episodic volunteers may be less committed to the event organisation, particularly in the case of first-time volunteers (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Bax and Chambers2016). This queries the extent to which episodic volunteers may be committed to the vision for a broader legacy of increased volunteering participation as often espoused by mega-events. Despite this, the episodic volunteering literature has noted that repeat episodic volunteering is associated with good supervision and volunteer satisfaction with the experience (Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Heist and Storti2017; Compion et al., Reference Compion, Meijs, Cnaan, Krasnopolskaya, von Schnurbein and Abu-Rumman2022), and the extent of previous episodic volunteering experience as a predictor of repeat episodic volunteering has also been noted (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Bax and Chambers2016). Our attention now turns to mega-event volunteering and legacies.

Mega-event Volunteering and Legacies

The Olympic movement has focused greater attention on legacy than other mega-events to date. Since its codification into the Olympic Charter in 2003 (IOC, 2017), legacy has come to the forefront in Olympic bidding and dialogues (Frawley, Reference Frawley2015). The IOC has defined event legacies primarily in terms of sporting, social, environmental, urban and economic legacies (IOC, 2012). This fits with the distinction between “hard” economic legacies and “soft” social legacies noted in the legacy literature (Preuss, Reference Preuss2019). Hard legacies are new jobs created or new infrastructure such as transport links and event venues, whereas soft legacies include feelings of civic pride and increased sports participation (Downward & Ralston, Reference Downward and Ralston2006; Reis et al., Reference Reis, Frawley, Hodgetts, Thomson and Hughes2017; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Cuskelly, Toohey, Kennelly, Burton and Fredline2019). Early legacy discourse focused on economic benefits and physical changes to the host city’s infrastructure (Baade & Matheson, Reference Baade and Matheson2016) but more recently bid documents and candidature dialogues have emphasised the soft benefits of hosting in terms of skills development and increased volunteering participation post-event (Frawley & Toohey, Reference Frawley and Toohey2009; Girginov et al., Reference Girginov, Peshin and Belousov2017; Minnaert, Reference Minnaert2012; Nichols & Ralston, Reference Nichols and Ralston2011).

Due the large numbers involved and the IOC’s emphasis on legacy, Olympic volunteering programmes have received considerable attention from researchers who have examined the motivations and experiences of volunteers (e.g. Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Benson and Terwiel2014; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Nichols and Ralston2018). While these studies focus on mega-event delivery, they also reveal challenges for volunteering legacy development. The most common motivator for mega-event volunteers is the opportunity to be part of a “once in a lifetime experience” (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Benson and Terwiel2014, p. 1), which can be difficult to replicate in everyday volunteering activities (Shipway et al., Reference Shipway, Ritchie and Chien2020b). There is scant longitudinal evidence for Olympic volunteer participation positively impacting on longer-term volunteering (Shipway et al., Reference Shipway, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Smith2020a). Beyond the Olympics, only Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Wolf, Lockstone-Binney, Smith, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Baum2014) found evidence of increased volunteering after a mega-event and this was primarily in roles and activities that volunteers had already been involved in pre-event, suggesting that the event volunteer programme had not generated a meaningful volunteering participation legacy.

Regulatory Capitalism and the Power of Volunteers

The growing importance of legacy is due not only to the need to justify cities’ bids to host these events, but also to answer the call for greater accountability of public resources and host community sacrifice in garnering support for mega-event hosting (Preuss, Reference Preuss2019). Regulatory capitalism involves a form of governance that has arisen in response to neoliberalism, where regulatory processes condition the operation, manipulation and deployment of economic, political and social power (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur and Drahos2017, p. 289). Governance within a regulatory capitalist system focuses on governments regulating the service provision of public goods delivered on their behalf by business and civic society (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2008). This is opposed to governance in the welfare capitalism period (1940s–1970s) for which governments both regulated and delivered public services (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2005). The resulting intertwining of relationships amongst public, private and third sector bodies can be used to embed more socially just and inclusive forms of capitalism but is equally capable of eroding democratic concerns by depoliticising development (Raco, Reference Raco2012). Regulatory capitalism is an extension of the contracting out of public service delivery to the private sector adopted by Western governments under New Public Management since the 1980s (Elkomy et al., Reference Elkomy, Cookson and Jones2019).

Regulatory capitalism has typically involved the conversion of policy concerns to private and contractual programmes, allowing private concerns (largely profit-oriented) to override the rights and obligations traditionally overseen by the public sector (Talbot, Reference Talbot2021). This results in a prioritising of private concerns in practice within the regulatory framework set out by the public sector, devolving the latter’s “responsibility for implementation to public–private networks and contract writers” (Raco, Reference Raco2014, p. 177). This paper will explore the impact of this form of governance and its associated outcomes on the voluntary sector.

As the Olympics invites both private investment from the IOC and its sponsors, as well as public contributions from host cities, the Olympic Games have become emblematic of the regulatory capitalism that has proliferated globally in liberal democracies (Raco, Reference Raco2014). The sectioning of Olympics planning and delivery into a series of delivery contracts by the organising committee is for practical reasons, as the committee cannot be expected to independently deliver all components of the Games. However, this practice raises the question of whether entrusting the crucial stage of planning to the private sector necessarily means trading community legacy outcomes for short-term economic benefits for businesses (Chalip, Reference Chalip, Brittain, Bocarro, Byers and Swart2018). This is particularly the case when volunteering infrastructure is ignored during planning stages. Softer legacies such as those around volunteering have been observed to be slowly replaced by regulatory capitalism, led by the public sector that is meant to uphold their delivery (Talbot, Reference Talbot2021). Using the lens of regulatory capitalism, this paper examines how a post-event volunteering legacy is facilitated by event organising committees leveraging existing volunteering infrastructure in host communities in the mix of private and public investments in the Games. Typically, volunteers are seen to be resources (Brudney & Meijs, Reference Brudney and Meijs2009) called upon for the purpose of Games delivery. As individuals, volunteers are fragmented and hold little power in relation to the governments that fund the Olympics and the corporate sponsors that contribute large sums. However, the mechanisms and infrastructure that assist and/or hinder the effective delivery of a volunteering legacy remain largely unexplored (Lockstone-Binney et al., Reference Lockstone-Binney, Holmes, Smith and Shipway2018).

Method

To investigate the ways in which mega-event organising committees engage with the third sector in their host cities, the study adopted a case study research design (Yin, Reference Yin2018) focusing on the Olympic Games as a global mega-event with large volunteer programmes. Case studies enable in-depth study of a particular phenomenon from a range of perspectives and allow for a mixed methods data collection approach. The research design was developed within a pragmatist paradigm, which focuses on real-world problems involving multiple sources of data and data types (Kelly & Cordeiro, Reference Kelly and Cordeiro2020; Yin, Reference Yin2018). A pragmatic approach allowed us to focus on concrete, real-world issues associated with volunteering legacies and tangible mega-event organising committee’s processes, from the perspectives of a multitude of key stakeholders. In doing so, we were able to view these stakeholder beliefs and ideas as tools for problem solving, while also focusing on both useful knowledge acquired from the study participants and linking to their own real-world Olympic experiences (Shipway et al., Reference Shipway, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Smith2020a).

The two cases of Sydney 2000 and London 2012 were chosen as they enabled a comparative approach to be taken in investigating the research question. While it is acknowledged there is a Western bias in the two Olympic Games being investigated, case study research designs are not necessarily designed to generalise to the wider population (Shipway et al., Reference Shipway, Ritchie and Chien2020b). The two events shared similarities in that they both had large volunteer programmes to support the mega-event and took place in Western neo-liberal democracies, with long histories of volunteering (Musick & Wilson, Reference Musick and Wilson2007). These two events, however, were also staged at different times, in different geographic locations and during varying economic periods. Key factors in the selection of these two case studies were timing and access. Selecting one event, which took place a considerable time ago and a second held more recently, enabled both longer- and shorter-term impacts to be noted (Yin, Reference Yin2018). Access was crucial for the team to collect the detailed data from relevant stakeholders in order to answer the research question and the research team had contacts for the London Games to facilitate initial access. The twelve-year time gap between the two mega-events also allowed for a holistic overview of the emergence of volunteering legacies, and the subsequent challenges faced by mega-event stakeholders.

Each case study involved two phases of data collection, following the approach previously used in studies of mega-event legacies (Minnaert, Reference Minnaert2012). Phase one focused on collecting secondary data about the volunteer programme at each event and what plans were made for volunteering post-event to build a narrative account of how Olympic volunteering and engagement with the existent volunteering infrastructure evolved. Secondary sources included academic papers, media reports, official reports, blog posts and a thorough search through archives including the IOC archives in Lausanne.

Phase two involved primary data collection using in-depth semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders for each event. The interviews sought to identify the extent to which stakeholders were involved in the planning of the Olympic volunteer programme; how they were involved in the planning and delivery of the volunteering legacy; and whether any volunteering infrastructure legacy generated by the Olympics had contributed to volunteering participation since the event. The interview participants were identified as a result of the phase one analysis and through snowball sampling and recommendations from interviewees as the project progressed (Noy, Reference Noy2008). Snowball sampling yielded representatives from a wide range of stakeholders, and we achieved data saturation through this process so it was not considered necessary to conduct a wider call for participants.

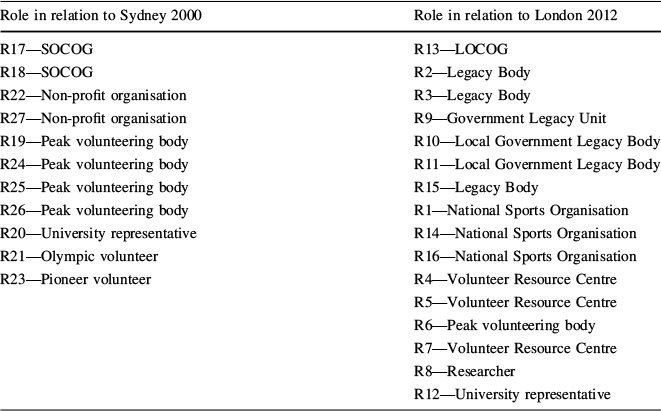

A total of 27 participants were interviewed for the study (Table 1). The longer time lag from Sydney 2000 meant that it was harder to source relevant interviewees and so fewer interviews (11) were completed for that case study compared to London 2012 (16). Interview participants were purposefully selected as representatives from the following stakeholder groups (see Table 1): Olympic Games Organising Committees (OCOGs); community and voluntary sector groups and sport governing bodies; key staff at the national and regional bodies for volunteering (known as “volunteering peak bodies” these are umbrella associations which represent voluntary organisations and disseminate pertinent sector-wide initiatives through their networks); policy makers and representatives from local and national government, including official legacy bodies; and both independent and university researchers. The interviews were conducted in English and lasted on average 72 min.

Table 1 Respondent profile

Role in relation to Sydney 2000 |

Role in relation to London 2012 |

|---|---|

R17—SOCOG |

R13—LOCOG |

R18—SOCOG |

R2—Legacy Body |

R22—Non-profit organisation |

R3—Legacy Body |

R27—Non-profit organisation |

R9—Government Legacy Unit |

R19—Peak volunteering body |

R10—Local Government Legacy Body |

R24—Peak volunteering body |

R11—Local Government Legacy Body |

R25—Peak volunteering body |

R15—Legacy Body |

R26—Peak volunteering body |

R1—National Sports Organisation |

R20—University representative |

R14—National Sports Organisation |

R21—Olympic volunteer |

R16—National Sports Organisation |

R23—Pioneer volunteer |

R4—Volunteer Resource Centre |

R5—Volunteer Resource Centre |

|

R6—Peak volunteering body |

|

R7—Volunteer Resource Centre |

|

R8—Researcher |

|

R12—University representative |

NB: the numbering refers to the order in which interviews were conducted

The interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis using qualitative template analysis, which combines deductive and inductive approaches (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012). An initial template was developed from the literature review (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012). The data from the transcripts were used to populate the initial template, but in addition, new themes were allowed to emerge from the data and were added to the template (King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012). The themes were clustered together into groups and positioned in an overall hierarchy of themes designed to answer the research question. Initially, the first five interview transcripts were used to populate the template, with this first stage completed by one researcher. This initial template was circulated within the research team to identify consistency and agreement in coding. Once agreement was reached, the rest of the interviews were coded to the template. For data that did not fit the existing themes, additional themes were created to enhance the richness of the analysis. New themes were created until the majority of data could be meaningfully coded against one or more themes in the hierarchical structure.

Case Study Background

To enable the volunteering legacy outcomes of the events to be understood within the context of their delivery, we first introduce the two case study events and their volunteer programmes, before analysing how the organising committee of each Games engaged with the existing volunteering infrastructure, including the challenges of these relationships. Sydney 2000 took place from 15 September to 1 October 2000 and the IOC (n.d.) stated that the Gamesforce 2000 volunteer programme involved 46,967 volunteers. London 2012 took place from 27 July to 12 August 2012 and London’s Games Maker volunteer programme recorded the participation of 70,000 volunteers (LOCOG, 2012).

The Sydney Olympic Games Organising Committee (SOCOG) used a staged pyramid approach to recruiting volunteers. Initially, a core group of 500 volunteers were recruited three years prior to the Olympics; these “Pioneer volunteers” assisted in some early test events and promoted the broader Olympic programme as part of the recruitment drive for Gamesforce 2000. The second stage involved recruiting skilled volunteers from the emergency services and sports federations, and the final stage was a call for generalist volunteers. Volunteer training was delivered by TAFE, a vocational education provider. SOCOG established a volunteer advisory committee in 1997, with stakeholders from community and volunteer-involving organisations.

In contrast, the London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games (LOCOG) used a programme management approach (Cuskelly et al., Reference Cuskelly, Fredline, Kim, Barry and Kappelides2021) to recruit volunteers in one phase from 2010, with recruitment continuing throughout the lead up to the event due to attrition. Selection and training of volunteers was delivered by LOCOG and sponsored by McDonald’s, an official IOC sponsor. There was no equivalent of the Sydney Volunteer Advisory Committee for London although the official Games report stated that the Olympics “engaged existing volunteer groups so that they could go on benefitting from this new enthusiasm” (LOCOG, 2013, p. 21).

Findings

The findings now examine the engagement strategies for each Olympic Games in turn, focusing on how they engaged with the existing volunteering infrastructure, their depth of engagement and challenges that emerged.

Sydney 2000

The requirement to articulate legacies was not introduced by the IOC until bids were sought for hosting the 2012 Olympic Games, so the Sydney 2000 bid team was ahead of its time in outlining a volunteering legacy. An aspect of SOCOG’s remit was to grow volunteering—the first time this was articulated as part of a successful Olympic Games bid. SOCOG sought to learn from the preceding Olympic Games, Atlanta 1996, where volunteers were seen as vital to the success of the Games, but training was neglected. Consequently, SOCOG took a prominent role in the training and recruitment of volunteers. SOCOG sought to engage with the third sector early on in establishing the Volunteer Advisory Committee in 1997. An array of third sector organisations were included in this committee, including representatives from Volunteering Australia (the national peak body for volunteering), Rotary, and the Rural Fire Service. A manager of volunteer recruitment was employed within SOCOG with the specific mission of working with volunteering peak bodies nationally and across the Australian States and Territories, suggesting that their perspective was valued in delivering the Sydney Games. Respondent 24, a peak volunteering body representative, recalled this engagement as providing recruitment opportunities for SOCOG through advertising volunteer vacancies through their networks. Respondent 18, a SOCOG representative, saw the peak bodies also contributing to maintaining a positive image for volunteering, as they proactively informed SOCOG of potentially negative publicity so that SOCOG could actively manage such situations.

Despite establishing these positive relationships during the planning stages for Sydney 2000, SOCOG was seen by some interviewees to take advantage of the third sector. While the Games were proactive in garnering input through the Voluntary Advisory Committee, SOCOG itself was seen to be unresponsive to requests from the third sector to share the training materials developed for the Gamesforce volunteers post-Games (R26, peak volunteering body). Despite providing volunteer recruitment and training, SOCOG was also seen as unwilling or unable to provide accreditation to its volunteer workforce. This represented a lost opportunity for volunteers, who had undergone significant training but due to the lack of accreditation could not provide proof of their proficiency to expedite recruitment for other volunteering roles.

The Australian third sector was therefore unable to benefit with knowledge transfer from the volunteer training and management tools that were developed using public sector funding for the Sydney Games. These tools were sold on to future Olympic Games organising committees rather than being shared within Australia’s third sector, who had been part of developing the resources (R24, peak volunteering body). For example, the “24 Hours in the Day of a Volunteer” training developed for Sydney 2000 was also used at the London Olympic Games but was not shared locally. This suggests that the voluntary sector and the potential to grow volunteering as a result of the Sydney Games were given less priority by SOCOG than other stakeholders’ needs.

Beyond the Games delivery, SOCOG was not involved in any form of legacy provision or programmes to leverage the spike of interest in volunteering as a result of the Olympics. However, stakeholder groups external to SOCOG did leverage the opportunities from hosting the Sydney Games to create grassroot legacies. These stakeholders were universities in New South Wales, the Centre for Volunteering NSW, Volunteering Australia, other state and territory peaks and volunteer resource centres. While the former sought legacies based on their work with the Olympic community and their students’ employment prospects, the latter promoted volunteering aggressively, linked to the United Nations International Year of the Volunteer (IYV) in 2001. Together, the Olympics and IYV brought unprecedented focus on volunteering, including the national peak, Volunteering Australia, which having been established in 1997 was still relatively new.

Volunteering peak bodies in Australia felt that Sydney 2000 significantly increased the profile of volunteering and directed more national government funding towards the sector (R24). However, the third sector also recognised there had been challenges. One barrier to legacy was the introduction of a new privacy law which meant that SOCOG could not share the volunteers’ contact details with other volunteer-involving organisations as initially planned. In addition, the relationships between SOCOG and the existing volunteering infrastructure had not always been harmonious, as peak volunteering body representative R26 reflected:

The volunteering sector across Australia felt quite excluded in the lead up to the Olympics, but there is a distinction between the lead up and the conduct of the Olympics itself. Because the conduct of the Olympics itself was so successful that the volunteering organisations could then build on the effect of that for themselves and for the development of volunteering across the country, but it would have been much more cohesive if they had been able to work together from the start.

It must be noted that both the newness of Volunteering Australia and the temporary nature of the SOCOG were challenges in establishing any long-term partnerships.

London 2012

LOCOG approached the Games Makers volunteer programme differently from Sydney. The bid process for the 2012 Games had, for the first time, included legacy (in general) as evaluation criteria. Volunteering England, the peak body for volunteering in the UK at the time of the London candidature (2005), was involved in the bidding process for the Games and LOCOG established a remit to create a volunteering legacy. LOCOG’s engagement with the volunteering infrastructure involved establishing a Volunteering Steering Committee of third sector representatives from across the UK to ensure that there was adequate representation geographically and included long-standing national leaders from the sector. Even though the host city was London, there was a desire to shape “a new culture of volunteering across the UK” (LOCOG, 2012, p. 34). The steering committee was considered a way to “learn from their deep experience but also to ensure the sector genuinely felt they were able to contribute” (R13, LOCOG representative). To seek to shape the volunteer strategy for the London Games, the steering group produced a document based on extensive consultation with stakeholders, which was presented to LOCOG:

…a sort of 100 page document on involving volunteers in the 2012 Games and it was a result of enormous amount of conversations with people in the sector and outside with business, with the public sector as well as the voluntary community sector. [R6, peak volunteering body representative]

LOCOG ignored this document. This was seen as symptomatic of a negative perception of the third sector generally within LOCOG, and they were keen to create a new volunteer programme untainted by the existing volunteering infrastructure (R3, legacy body representative). They sought to engage people new to volunteering, although while this was outlined in the London 2012 bid document (DCMS, 2012), Holmes et al. (Reference Holmes, Nichols and Ralston2018) noted that applicants for the volunteer programme with previous experience at other sports events were eventually preferentially selected.

Representatives from the third sector did not feel that their contributions were valued by LOCOG, as illustrated by R6, a peak volunteering body representative:

[LOCOG] didn’t really have that many roots into the sector themselves and so they were relying on intermediary bodies like Volunteering England and others to connect them to the community and the sector. And if I was to think about how much money we could’ve and perhaps should’ve charged LOCOG in terms of consultancy costs, I think they had a tremendously valuable resource from Volunteering England and many other sector organisations in helping them to develop their strategy and implement their strategy…

And that was a bit of a bugbear in that they were quite happy to go to some of the big accountancy firms and pay a lot of money for advice and consultancy on particular aspects of their programme, including some of the volunteering stuff.

This engagement strategy produced feelings of resentment towards LOCOG, as the third sector felt that LOCOG’s cherry-picking of their advice was inappropriate. However, respondents felt compelled to remain in advisory positions as it was their only way of staying involved in the volunteer management of London 2012 (R6, peak volunteering body representative). The resentment was further fuelled by perceptions that the third sector was taken for granted and that engagement with the sector’s workforce was “panicked engagement rather than genuinely value[ing] it” (R7, volunteer resource centre representative). This perception was reinforced by situations such as when the private company who was contracted to deliver training, failed to do so and the third sector was quickly ushered in to fill this training gap (R7). The continual award of contracts to private sector providers (for example, the volunteer programme was sponsored by McDonald’s) for volunteer programme delivery signalled an unwillingness by LOCOG to invest in the local volunteering infrastructure, defaulting to reliance on private sector service provision.

While some form of volunteering legacy had been planned since the bidding stage (LOCOG, 2012), specific legacy plans were only developed late in the planning stage, with one volunteer resource centre respondent commenting “there never seemed to be clear thoughts on what the legacy was for volunteering” (R5). LOCOG was not involved in the delivery of legacies post-London 2012; instead, a separate foundation—Join In—was tasked with planning and delivering a volunteering legacy for London. A challenge was identifying what activities would be appropriate for Olympic volunteers, noting that people who volunteer for such a prestigious episodic mega-event may be unlikely to follow this up with more traditional ongoing volunteer placements. Join In focused on encouraging volunteers into sport and recreation volunteering opportunities and sought to be distinctly different from the existing volunteering infrastructure, as articulated by R3, a representative of the legacy body:

…we created this organisation that was somewhat different from the other existing voluntary organisations. Our patrons aren’t… we communicate in quite a different way, we’re not… with respect, the clammy hand of the third sector.

It was apparent from the interviews that volunteering legacies that eventuated from London 2012 were largely driven by existing peak bodies, and sporting and volunteer-involving organisations such as Team London, Sport England, and England Hockey, rather than Join In.

Just as Sydney’s “24 Hours in the Day of a Volunteer” training had not been shared with the local third sector, after London 2012, knowledge transfer was primarily about sharing experiences with future Olympic Games organising committees, and representatives from LOCOG met with the Sochi and Rio de Janeiro committees. There is little evidence of knowledge transfer to the existing volunteering infrastructure in the UK.

Discussion: Delivering a Volunteering Legacy Under Regulatory Capitalism

At Sydney 2000, there was an effort to engage with the third sector during the planning stages before the event. However, in terms of legacy delivery, the benefits tended to accrue due to external forces such as the International Year of Volunteers, which continued to focus attention on volunteering and facilitated government investment in the sector. In addition, while the third sector hoped to benefit from the tools developed using public funds, these were on-sold as part of knowledge transfer to future Olympic Games. Looking back on Sydney 2000, many of the Gamesforce volunteers continued to keep in touch with each other and volunteer after the event, however, this was self-organised by the volunteers (Fairley et al., Reference Fairley, Gardiner and Filo2016).

In London, the third sector worked hard to be involved in the event planning process from the bidding phase onwards. The sector came together to produce a volunteer legacy strategy, which was rejected by LOCOG. While private sector organisations received numerous contracts for their services (Nichols & Ralston, Reference Nichols and Ralston2015), volunteer-involving organisations were expected to work without financial recompense, offering evidence of a regulatory capitalist preference for the private sector (Raco, Reference Raco2014). A legacy body was established following London 2012, though planning for this body was left until late in the planning stages. The legacy body sought to operate separately from the existing third sector volunteering infrastructure.

Both the Olympic Games organising committees engaged in partnerships with private industry to deliver the event through a series of contracts under regulatory capitalism (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2008). Both Olympic Games were funded primarily through public money, but there was little accountability for the private organisations (both the committees and the contractors) established to deliver these events (Nichols & Ralston, Reference Nichols and Ralston2015). The following discussion will outline the means by which regulatory capitalism is incompatible with mega-event legacy concerns.

Firstly, the long-term nature of legacy delivery is necessarily at odds with the short-term obligations of an event organising committee (Nichols & Ralston, Reference Nichols and Ralston2012), and this mismatch does not lend itself to easy identification of which party should deliver the legacy. The temporal limitation that prevents event delivery bodies from being effective stewards of a volunteering legacy also impacts legacy organisations such as London’s Join In, as there is an absence of perpetual funding. While local volunteer-involving organisations present an existing alternative that is embedded in host cities’ communities, the organising committees had varied willingness to engage with them. Admittedly in the case of Sydney, the peak body, Volunteering Australia, was a new organisation, which may have impacted its ability to engage on legacy planning.

Secondly, mechanisms to encourage continued volunteering must be built and transitioned into. While volunteers are seen as resources to be expended during Games periods, it should not be taken for granted that volunteers will be so buoyed by their Games volunteer experiences that they would seek out other volunteer opportunities. Extant research suggests that predominantly those who have prior volunteering experience will continue to volunteer after a mega-event (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Wolf, Lockstone-Binney, Smith, Lockstone-Binney, Holmes and Baum2014) and that this is partly due to the nature of episodic volunteering (Maas et al., Reference Maas, Meijs and Brudney2021) and the prestige of volunteering at large-scale once-off events. New volunteer initiatives such as Join In are likely to displace existing volunteer participation rather than encourage new activity, and further research is needed to investigate this opportunity cost.

Thirdly, the model of decision-making by the organising committees points to a private industry bias that was encouraged by the devolvement of public responsibility in this regulatory capitalism framework (Nichols & Ralston, Reference Nichols and Ralston2015). This assumed that private industry would be more accountable and effective at delivering volunteer programmes for the Olympic Games, while the local volunteering sector was irrelevant, at worst, and amateur, at best. This sentiment most prominently expressed by R3, a legacy committee member of LOCOG, who described Join In as superior to the current third sector’s offerings because “it’s got business focus and drive”, reflecting the bias in regulatory capitalism towards the private sector in delivering events (Raco, Reference Raco2014). This sentiment proved fallible when a private organisation failed to deliver on running the volunteer centre at London 2012, and a local third sector organisation was asked to fill the gap in what was described as “panicked engagement” (R7).

Fourthly, in pursuing a volunteering legacy, SOCOG sought local volunteer organisation representation, but LOCOG deliberately kept the local volunteering sector at arm’s length in deference to its stated goal of attracting non-volunteers that they hoped to convert into volunteers post-Games. This strategy exposed LOCOG’s unfamiliarity with volunteer recruitment, which meant LOCOG still ended up with a group of Games Makers primarily consisting of people who were already volunteering in other capacities, with one study reporting that only 20% were first-time volunteers (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Benson and Terwiel2014). One volunteer resource centre respondent commented that “it didn’t create a huge amount of extra capacity, it just displaced the capacity” (R7), and local volunteer organisations ended up with an unexpected cannibalisation of their volunteer workforce despite LOCOG’s resolute targeting of non-volunteers in recruitment. As a private entity, LOCOG was not obligated to understand the characteristics of volunteering and volunteers, but inadvertently sabotaged its legacy objectives by actively disengaging from those who understood volunteering, due to its bias towards the private sector in delivering contracts (Raco, Reference Raco2014).

The incompatibilities between regulatory capitalism and volunteering legacy delivery were therefore evident (Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite2008). There was clearly a perception at London 2012 that the private sector was “good” in that they could deliver, while the third sector was seen almost as amateur or irrelevant. It seems clear that within regulatory capitalism, money matters in terms of establishing power relations as stakeholders outside the commercial sector are disenfranchised (Raco, Reference Raco2014). This discussion raises several challenges for mega-event volunteering legacies and calls into question whether a mega-event volunteer programme delivered within regulatory capitalism can ever generate a volunteering legacy.

Conclusion

Governments and mega-event organisers make substantial claims about legacies to justify the cost and commitment for hosting such spectacles. Our paper sought to investigate how far organising committees engaged with existing volunteering infrastructure to deliver a volunteering legacy using the case studies of Sydney 2000 and London 2012. Given the episodic nature of the volunteering assignments and the temporal nature of these events and their organising committees, we question what kind of volunteering legacy is possible within the scope of these parameters if there is not effective engagement with local volunteering infrastructure?

The examples of both Sydney 2000 and London 2012 show how seeking to develop a legacy without engaging with the existing third sector and volunteering infrastructure is challenging. While in Sydney SOCOG tried to engage, there was no follow through for legacy planning. In London, in delivering the 2012 Games through regulatory capitalism, LOCOG took a deliberate path to ignore or bypass the existing third sector. Sadly, for the third sector, our findings show that for mega-events hosted by Western liberal democracies, it is not enough for the third sector to seek to engage with the event organising committee. The third sector will have to proactively, and forcefully, create strategies that are responsive to the contexts within which they are operating. Perhaps in the case of London 2012, the third sector collectively through a larger not-for-profit organisation or sector body could have bid for the contract to run the volunteer programme and this may be an option for future Olympic Games. It seems that it would have been beneficial for sector organisations to charge for their work at private rates to highlight its value to the organising committee.

In terms of practical implications, mega-event organising committees should work far closer with key volunteering stakeholders throughout the third sector and capitalise on their diverse wealth of experience and knowledge. Key stakeholder insights suggest that event organising committees have often failed to engage with the volunteering infrastructure in host cities, which has been a missed opportunity. The findings identify some practical opportunities to leverage more meaningful and open engagement between event organising committees and the third sector to ensure that sustainable volunteering legacies are realised. These include developing structured dialogue, mechanisms and partnerships between the event organising committee and the host location’s volunteering infrastructure, including peak volunteering bodies; value and renumerate the expertise of the third sector as having similar importance to that of commercial consultants; and establishing ownership and usage rights to data and resources (such as the volunteer database and training resources) as part of the knowledge transfer process.

Limitations and Further Research

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. Primarily, it is most applicable to mega-event volunteering legacies in Western democracies with formalised volunteering infrastructures. Future studies of mega-event legacy governance models in non-Western settings would be beneficial to compare and contrast the scope of the current findings. For example, retrospective studies of Beijing’s hosting of the Summer (2008) and/or Winter (2022) Olympic Games could be instructive on this point and address limited understanding of mega-event volunteering legacies relative to China’s collectivist culture (Chong, Reference Chong2011). We also note the challenges of recall and accessing participants when a substantial time period since the event has elapsed; while secondary data can provide contemporary accounts, the institutional knowledge from the period can be harder to access. Additionally, this study did not seek to follow-up with event volunteers themselves about their post-Games volunteer careers. Privacy legislation would have prevented this in the case of Sydney.

Further research could extend this research theme going forwards. Firstly, additional case studies could be added to the data pool to illustrate alternative contexts including both Olympic Games and other mega-events such as the FIFA World Cup. Secondly, our study evaluated legacies retrospectively, instead, the legacies could be tracked longitudinally over time from the bid phase to post-event to see how they emerge, develop and eventuate. Third, we primarily engaged with interviewees who had been involved in the Olympics and volunteering programmes or were part of the national or regional volunteering infrastructure; the perspectives of other stakeholder groups not extensively covered in this study could provide broader insights, for example, grassroots voluntary organisations.

The impact of external forces on volunteer legacy planning between the event announcement, delivery and legacy phase is a significant challenge. With the extension of the time lag between bid announcement and the event to 11 years for both Los Angeles 2028 and Brisbane 2032, even more is likely to be at stake for volunteering infrastructure bodies in engaging with future Olympic hosts to deliver sector-engaged volunteering legacies.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and data analysis were conducted by Leonie Lockstone-Binney, Kirsten Holmes, Richard Shipway and Karen Smith. The literature review and further data analysis were conducted by Faith Ong. Manuscript preparation was led by Kirsten Holmes and Karen Smith.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The research leading to these results received funding from the International Olympic Committee Advanced Research Grants Fund, 2015–2016 round.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

The data were collected with approval from the William Angliss Institute (Melbourne) Human Research Ethics Committee, where the lead investigator Leonie Lockstone-Binney was based at the time, and all interview participants provided formal informed consent through a signed consent form, having received a participant information sheet, following the guidelines of the (Australian) National Statement on Human Research Ethics, 2007, https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/national-statement-ethical-conduct-human-research-2007-updated-2018.