1. Introduction

OpenAI’s ChatGPT and similar large language models (LLMs) have garnered attention for their ability to engage in realistic conversations with humans (Biever, Reference Biever2023), excel in scholastic ability tests (OpenAI, 2024a), and mimic liberal political viewpoints (Rozado, Reference Rozado2023). This new technology has sparked interest in their potential applications in understanding human decision making, and by extension to leveraging their potential in lieu of human respondents in behavioral experiments (Argyle et al., Reference Argyle, Busby, Fulda, Gubler, Rytting and Wingate2023; Bail, Reference Bail2024; Brookins & DeBacker, Reference Brookins and DeBacker2024; Hayes, Yax, Palminteri, Reference Hayes, Yax and Palminteri2024; Horton, Reference Horton2023).Footnote 1 This paper investigates the potential of ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo, ChatGPT-4.0, Gemini 1.0 Pro, and DeepSeek-R1 to simulate human behavior, in the context of the effects of changing stake size in the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) game. These LLMs differ in architecture, training data, and fine-tuning methods, which potentially contribute to variations in the answers they generate. As such, it is important to examine differences in how these models respond should they be used in lieu of humans in behavioral economics research.

The importance of the Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) game originates from its illustration of a situation where individuals acting in their own self-interest produce a suboptimal outcome compared to that arising when parties cooperate. In other words, the unique Nash equilibrium of the one-shot PD game (both individuals choosing to defect) is Pareto-dominated by the outcome where both individuals cooperate. Analyzing the behavior in this game helps researchers understand how individuals make decisions in situations such as those involving competition for depletable resources, shedding light on concepts like cooperation as motivated by other-regarding considerations such as trust and reciprocity, and the role of incentives to defect. Famously, the game has been used to model a number of real world applications from advertising and pricing decisions to international relations arms race models. As such, to date, a number of studies (Boone et al., Reference Boone, De Brabander and Van Witteloostuijn1999; Heuer & Orland, Reference Heuer and Orland2019; Jones, Reference Jones2008; Mengel, Reference Mengel2018) explore utilization of pure versus mixed strategies even in one-shot game play. However, unlike the theoretical prediction with self-interested decision makers, experiments on the one-shot version of PD with human participants yield noteworthy departures from the Nash equilibrium behavior of self-interested individuals, whereby a significant number of participants choose to cooperate, rather than defect, and thereby providing evidence for motivations beyond self-interest.

An important question is whether individuals cooperate less as the stakes get bigger. Larger stakes can motivate other-regarding individuals to defect, increasing the prevalence of suboptimal outcomes (for example, because the strategy of cooperation is perceived to be personally riskier). An early study by Aranoff and Tedeschi (Reference Aranoff and Tedeschi1968) involving 216 subjects found this to be the case: A larger number of defections were associated with larger stakes. Nevertheless, more generally, there is mixed evidence regarding stake size in a variety of games (e.g. Johansson-Stenman et al., Reference Johansson-Stenman, Mahmud and Martinsson2005; Kocher et al., Reference Kocher, Martinsson and Visser2008; Leibbrandt et al., Reference Leibbrandt, Maitra and Neelim2018). Given the costs of running high stakes laboratory experiments, other studies exploited quasi-experimental techniques. For example, List (Reference List2006) examined results from the television show ‘Friend or Foe?,’ a game similar to PD.Footnote 2 Although he found women, whites, and older participants cooperate more than others, stakes did ‘not have an important effect on play.’ This result differs from the findings of Darai and Grätz (Reference Darai and Grätz2010) and Van den Assem et al. (Reference Van den Assem, Van Dolder and Thaler2012) who found ‘a negative correlation between stake size and cooperation’ from the television show ‘Golden Balls,’ another game similar to PD.

There is now a burgeoning body of literature utilizing LLMs as subjects to play workhorse games such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the Dictator Game, or the Ultimatum Game (Aher et al., Reference Aher, Arriaga and Kalai2023; Añasco Flores et al., Reference F., Julio, Bryan, Pamela and Maria2023; Argyle et al., Reference Argyle, Busby, Fulda, Gubler, Rytting and Wingate2023; Brookins & DeBacker, Reference Brookins and DeBacker2024; Guo, Reference Guo2023; Horton, Reference Horton2023). However, we know of no studies utilizing LLMs to analyze the impact of stake size in the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Further, there are few studies that scrutinize the effect of framing on LLM behavior in workhorse games (Edossa et al., Reference Edossa, Gassen and Maas2024; Engel et al., Reference Engel, Grossmann and Ockenfels2024). This paper fills these gaps in the literature. By altering new parameters, we place LLMs under stronger ‘stress-tests,’ allowing us to gain fresh insights into an LLM’s morality and reasoning ability.

We test the impact of payoff stakes on cooperation rates of LLM agents by replicating a recent human study by Yamagishi et al. (Reference Yamagishi, Li, Matsumoto and Kiyonari2016) (‘Study 2’)Footnote 3 with modifications for our use with AI. In Yamagishi et al. (Reference Yamagishi, Li, Matsumoto and Kiyonari2016) ‘Study 2,’ each participant submits decisions for multiple one-shot simultaneous PD games without receiving any feedback on the outcome. Each game is characterized by a stakes parameter (with three different values) that changes the payoffs of both players. To control for whether the sequence of payoffs affects a player’s strategy (order effects), Yamagishi et al. randomize the order of payoff stakes in the games each participant plays. In the replication, we elicit LLMs’ choice of cooperation versus defection for three games that differ only in terms of the payoff stake size (low, medium, high) and analyze the sensitivity of responses to the ordering of the stakes. We find that for the most part stakes affect cooperation rates but none of the LLMs come close to replicating the human study, and further they show sensitivity to the sequence in which stakes are presented.

In addition, we present two separate but almost identical prompts describing the game, to examine if changes in framing alters each LLM’s responses. We find that for the more sophisticated models (ChatGPT-4.0, Gemini 1.0 Pro, and DeepSeek-R1) framing has a minor impact on results, but that ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo’s inconsistency may warrant caution when interpreting simulated behavioral experiments.

2. Replication methods

In ‘Study 2,’ Yamagishi et al. (Reference Yamagishi, Li, Matsumoto and Kiyonari2016) recruited 162 Japanese university students to participate in 30 anonymous, one-shot, simultaneous-decision PD games with stake sizes of JPY 100, 200, and 400 (10 games played per stake size). The authors employed an exchange format framingFootnote 4 of the PD in the instructions. To control for order effects (possible response biases caused by the order in which stakes were presented to the players), Yamagishi et al. randomized the order of three possible stake sizes in the 30 games played by each participant. They found a significant overall negative relationship between the probability of choosing the cooperative strategy and stake size.

We query 400 LLM ‘subjects’ using the same exchange format instructions, giving them the option either to keep their endowment or to send a doubled amount to the other player.Footnote 5 To be able to simulate a within-subjects design like the human study, we repeat the PD game three times within the same query where each game has a different stake size (JPY 100, 200, and 400).Footnote 6, Footnote 7 We collect responses to four queries that differ based on the order in which the three stakes are presented, simulating a between-subjects treatment on the sequence of PD game stakes: (i) increasing stakes; (ii) decreasing stakes; (iii) medium, large, small; and (iv) small, large, medium. We then compare the results to those of Yamagishi et al. For brevity, we present only the results from the increasing and decreasing stakes sequences in the main text and provide the results for the remaining two sequences in Appendix B.3.

Additionally, we investigate framing effects by using another prompt that explains the rules of the PD game in a more conventional wayFootnote 8 (see Appendix A for the full prompts used).Footnote 9 Both prompts detail the game and possible strategies of play. However, the prompts in the original replication are more direct while those in the second version are more abstract in that they refer to strategies A (cooperating by sending double one’s endowment to the other player) and B (keeping one’s endowment). Each prompt implies the same PD payoff matrix, but we explicitly provided the matrix to ensure that the LLM correctly ‘understood’ it.Footnote 10 This yielded an additional set of 400 observations for each LLM that allows us to test if responses are consistent to changes in framing.Footnote 11

3. Results

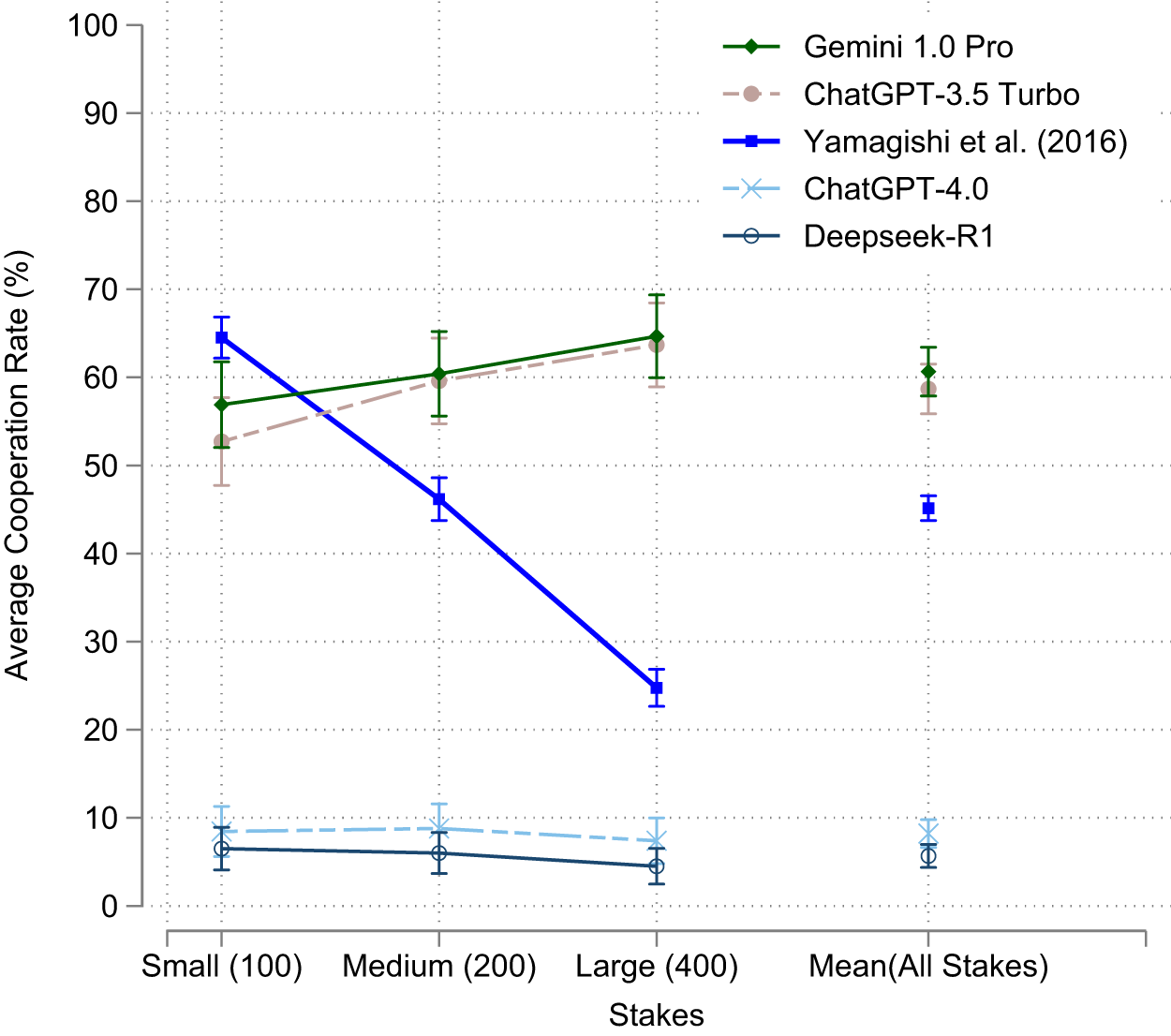

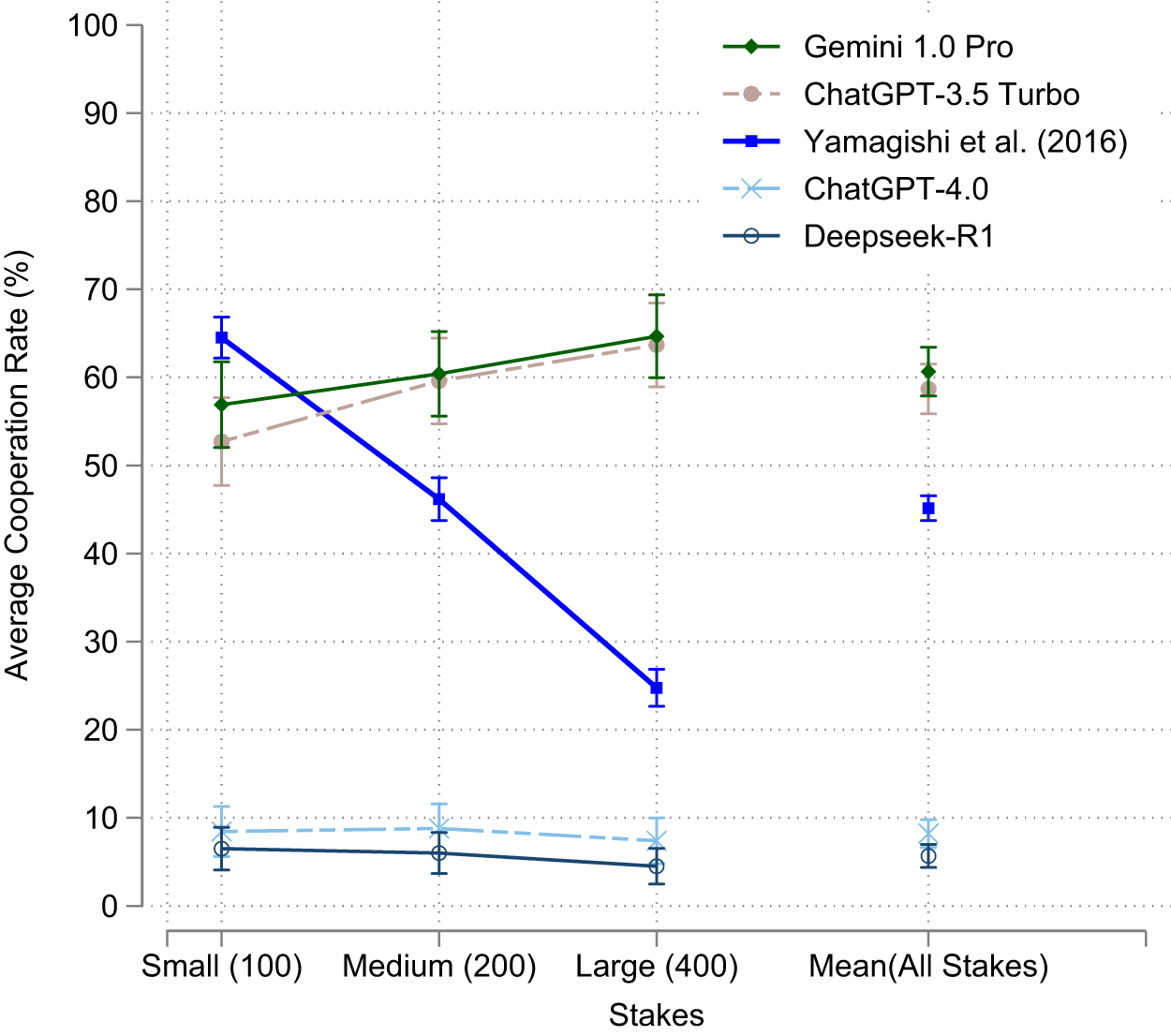

Using a Python script we interacted with the ChatGPT, Gemini, and DeepSeek APIs and compiled their respective outputs.Footnote 12 Both models were run with the default temperature setting. To streamline the analysis of a large number of responses, we instructed the LLMs to respond with a single letter indicating either ‘cooperate’ or ‘defect.’ Occasionally, the AI deviated from these instructions, resulting in a minor number of errors (the distribution of errors is presented in Appendix B.1). As a result, a relatively small number of the AI subjects were invalidated and excluded from our analysis. Fig. 1 provides a comparison of aggregate cooperation rates and 95% confidence intervals obtained from each LLM using the exchange frame prompt, alongside the results Yamagishi et al. obtained.Footnote 13

Fig. 1 LLM replications of Yamagishi et al. (Reference Yamagishi, Li, Matsumoto and Kiyonari2016): Study 2

We find that none of the LLMs produce a behavioral pattern across the different stakes that aligns with the human participants in Yamagishi et al. ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo and Gemini 1.0 Pro exhibit a similar cooperation rate for the smallest payoff stake (JPY 100), but yield a slightly positive relationship between stake size and cooperation rate, as indicated by the average cooperation rates in the Small Stake (JPY 100) and the Large Stake (JPY 400) in Fig. 1. Tests of equal proportions for Yamagishi et al. data indicate a strong negative relationship between stake size and cooperation rate (Small versus Large: z = 22.76, p = 0.000), but responses from ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo and Gemini 1.0 Pro (Small versus Large) produce a positive relationship (z = − 3.10, p = 0.0019 for ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo; z = − 2.25, p = 0.0246 for Gemini 1.0 Pro). Meanwhile, ChatGPT-4.0 and DeepSeek-R1 generate relatively constant cooperation rates across all stakes (Small versus Large: z = 0.54, p = 0.5922 for ChatGPT-4.0; z = 1.24, p = 0.2147 for DeepSeek-R1), but these rates are significantly lower than the rates obtained in the human study of Yamagishi et al. This latter pattern contrasts the ‘more generous’ overall behavior attributed to LLM ‘subjects’ in recent studies, such as Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Xie, Yuan and Jackson2024) and is inconsistent with moral bargain-hunting found by Yamagishi et al. Rather, in our dataset ChatGPT-4.0 and DeepSeek-R1 produce a pattern consistent with the Nash equilibrium, albeit, with some ‘errors’ towards cooperation.

Another striking finding is that LLMs exhibit order or sequence effects. First, regardless of the actual stake size, ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo, ChatGPT-4.0 and Gemini 1.0 Pro provide the highest cooperation rate in the first PD game, followed by the second and then the third. As illustrated in Fig. 2 panels (a)-(c), regardless of the stake size, cooperation is highest in the first PD game (denoted by (G1) in Fig. 2) and lowest in the third (i.e. last) PD game (denoted by (G3) in Fig. 2) This pattern clearly shows that the order in which a stake was presented (1, 2, or 3) in a query determines the cooperation rate instead of stake size for the three LLMs. This result means that combining different stake size sequences can lead to the observed positive (or at least non-negative) relationship between stake size and cooperation rates observed in Fig. 1, a pattern inconsistent with human behavior. Averaging ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo and Gemini 1.0 Pro cooperation rates over all stake sizes yield cooperation rates approximately equal to the JPY 100 stake size observed in human studies. Thus, by failing to control for order effects, researchers might be misled into believing that these LLMs mimic human behavior. On the other hand, DeepSeek-R1’s cooperation in the increasing stakes queries do not statistically differ from those in the decreasing stakes queries.Footnote 14 However, as shown in Appendix B.4, DeepSeek-R1 exhibits very slight sequence effects, meaning cooperation rates differ between queries where stakes are presented monotonically (either consistently increasing, i.e. small (S) in G1, medium (M) in G2, and large (L) in G3 or consistently decreasing, i.e. large in G1, medium in G2, and large in G3) or non-monotonically (either L, S, M or S, L, M in G1, G2, and G3).

Fig. 2 Results by stake order sequences

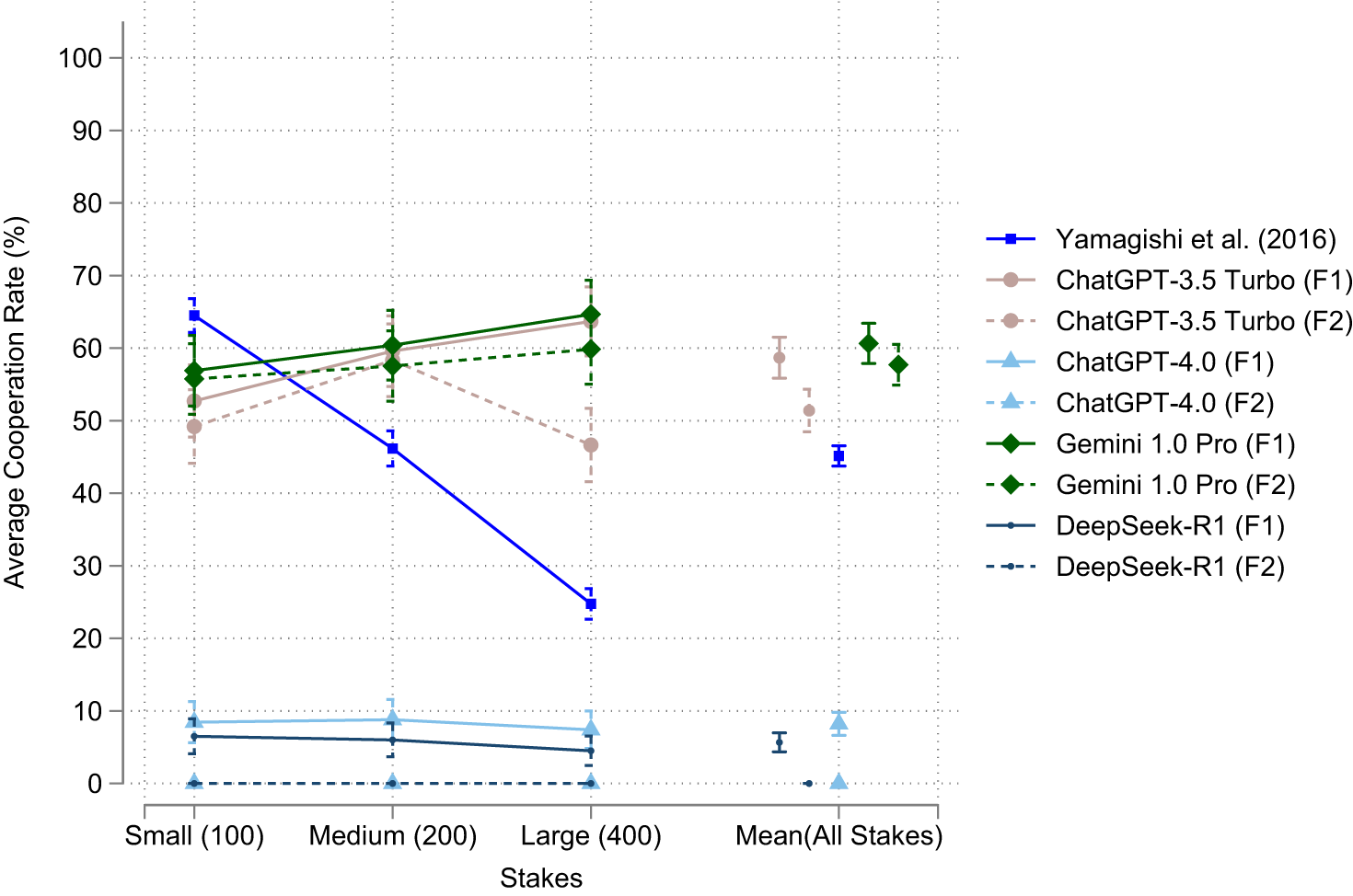

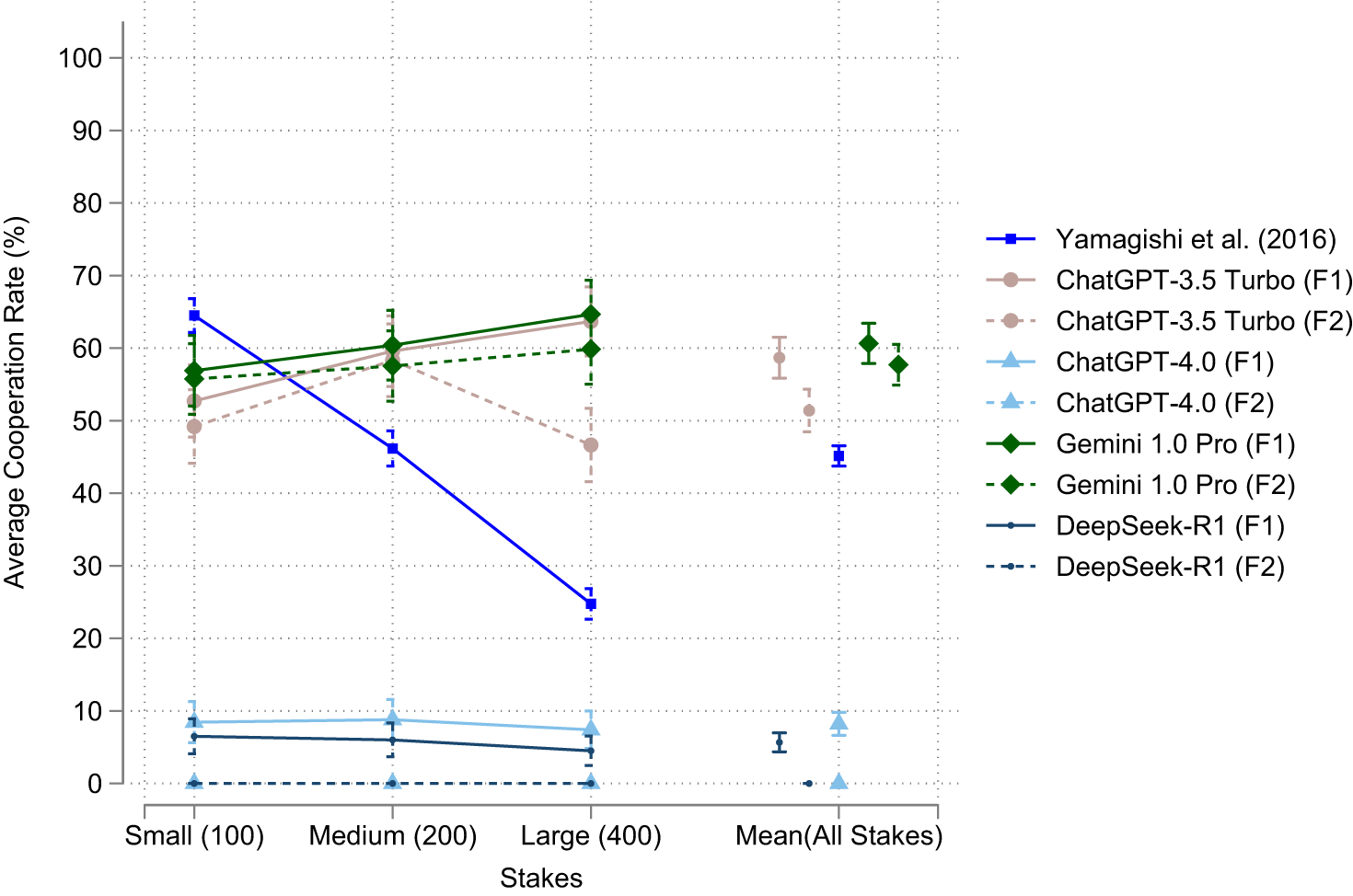

Finally, to test whether framing (i.e. the instructions given to the LLM) matters, we slightly alter the instructions given to the LLMs. This new prompt minimally amends the previous instructions. The exact differences between the two are spelled out in Appendix A. When doing so, we collected an additional 400 responses from each LLM using the modified PD instructions. Fig. 3 shows that for ChatGPT-4.0, DeepSeek-R1, and Gemini 1.0 Pro, the new instructions do not change the overall relationship between stake size and cooperation rate, but slightly decrease the average cooperation rates. On the other hand, ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo results are somewhat sensitive to framing, possibly due to being an older model trained on a smaller body of data. This finding is consistent with Lorè and Heydari (2024) who show that ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo is sensitive to context while ChatGPT-4.0 is more structure focused. It suggests the need for caution especially when using older models to simulate behavior (e.g. Brookins & DeBacker, Reference Brookins and DeBacker2024; Horton, Reference Horton2023; Argyle et al., Reference Argyle, Busby, Fulda, Gubler, Rytting and Wingate2023; Dillion et al., Reference Dillion, Tandon, Gu and Gray2023).

Fig. 3 Impacts of framing

4. Conclusion

We find that the current major LLMs (ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo, ChatGPT-4.0, Gemini 1.0 Pro, and DeepSeek-R1) do not understand the notion of payoff stakes in a way that is similar to humans. ChatGPT-4.0 and DeepSeek-R1 produce response patterns closest to the Nash equilibrium strategy of selfish rational decision makers across all stake sizes, replicating ‘homo economicus’ more than ‘homo sapiens.’ Gemini 1.0 Pro and ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo consistently produce high cooperation rates. Moreover, ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo, ChatGPT-4.0, and Gemini 1.0 Pro exhibit order effects as they are highly sensitive to which stake is presented first. second, and third. Further, DeepSeek-R1 exhibits slight sequence effects. Finally, ChatGPT-3.5 Turbo is sensitive to a minimal change in instructions (framing). These results raise questions about the LLMs reliability as simulators of humans in behavioral experiments. We anticipate that inconsistencies with both framing and order effects are present with AI experimentation with other games and not unique to the Prisoner’s Dilemma or stakes testing. As such, in their current stage of development, LLMs appear to be unreliable tools for simulating behavioral experiments with humans, and they must be used with caution.

Recent developments in LLMs should improve how they respond to queries given innovations in their underlying design. Current trends suggest future models are becoming more complex, with trillions of parameters. Efforts are also underway to enhance training efficiency, computational performance, and reasoning abilities. Hopefully, these changes will lead to LLMs that provide more accurate, context-aware, and consistent answers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/esa.2025.10023.

Author contributions

SWP, KR, and OT conceptualization and research design; KR and OT python programming; SWP, KR, and OT writing and editing.