Introduction

In recent years, several political parties have been destabilized by Members of Parliament (MPs) who decided to change their party affiliation. Just to mention few examples, the Austrian Freedom Party was repeatedly hit by defectionsFootnote 1 from the 1990s until the 2000s, while Syriza in Greece faced the same experience in the 2010s. In Italy, the Northern League and the left‐wing Communist Refoundation Party were weakened by defections twice in the 1990s, while Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia lost one‐third of voters after the waves of defections experienced between 2013 and 2018, when half of its representatives migrated to other parliamentary party groups (this party faced many switches in the 1990s too). Something similar occurred to the Socialist Party in France; affected by internal dissent and party switching, in the 2017 French legislative elections, its vote share dramatically shrunk. Analogously, the Progress Party in Denmark declined after episodes of defections at the turn of the 1990s. Similarly, in 2008, members of the Swiss People's Party (SVP) left the group to find the Conservative Democratic Party. In the following elections, in 2011, the SVP lost votes for the first time since 1987.

These examples highlight the potential damaging effect of parliamentary party defections. Intraparty quarrels that produce defections can hurt a party's reputation, triggering a reaction to restore the valence image damaged by the split or to profitably adjust and clarify the party's policy positions. Even in a country like the United Kingdom, which is only occasionally affected by parliamentary defections, switchers managed to grasp media attention, damaging the image of their former parties and affecting the course taken by them (this happened, for instance, in 1981 when splinters from the Labour Party formed the Social Democratic Party and, more recently, in 2019, when both Labour and the Conservatives were affected by several switches). Indeed, from an academic perspective, a number of studies highlight that party defections can be damaging for a party's strength and survival (Gherghina, Reference Gherghina2016; Grose & Yoshinaka, Reference Grose and Yoshinaka2003), while also endangering various elements of the Responsible Party Government model (Heller & Mershon, Reference Heller, Mershon, Heller and Mershon2009a), as when politicians change affiliation, voters’ ability to hold their representative accountable is hampered (Mershon, Reference Mershon, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014).

How do parties react to parliamentary defections and what strategies do they adopt in order to cope with such potential damage? The present paper tries to investigate this question through the idea that defections represent a valence damage for the value of a party's label. By analyzing the content of party manifestos, this paper sheds light on the electoral strategies that parties hit by parliamentary switching put in place to counteract the negative effects of defections.

So far, scholars proposed several theoretical models to investigate party competition in the presence of a valence advantage/disadvantage (Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001; Schofield & Sened, Reference Schofield and Sened2006; Serra, Reference Serra2010) showing that parties should shift their ideological position in reaction to relative changes in their valence reputation. In line with the centripetal valence effect theory (Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009), empirical analyses made by Somer‐Topcu (Reference Somer‐Topcu2007) and Clark (Reference Clark2014) suggest that parties moderate their position on the left‐right continuum when their valence attributes worsen.

Apart from the effects in terms of a policy shift along the left‐right scale, however, the existing literature does not investigate which other electoral strategies parties adopt to cope with a valence damage. The present paper aims to fill this gap. We focus on one specific case of valence damage; namely party switching in the parliamentary arena, which is related to the valence attribute of party unity (Clark, Reference Clark2014). Party switching can indeed be particularly damaging for the party in terms of valence reputation. Defections can be interpreted as a signal of weakness and lack of competence to keep the party united and to properly select loyal MPs, and they can also signal inconsistency and lack of credibility. Interestingly, higher levels of switching are associated also with stronger dis‐unity in parliamentary votes (O'Brien & Shomer, Reference O'Brien and Shomer2013), which is another signal of weak leadership and lacking cohesion.

Building on previous works and starting from the centripetal valence effect model (Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009; see also Serra, Reference Serra2010), we contribute to the existing literature by analyzing a variety of electoral strategies that parties can adopt after the reputation loss produced by defections, ranging from valence to policy and issue competition. We argue that parties affected by valence damage could adopt several campaign strategies to lower its negative consequences. Parties can try to restore their valence reputation by emphasizing their competence to govern. Additionally, parties might enhance the clarity of the party label by drafting manifestos that are less ambiguous in terms of policy proposals. Presenting a clear policy program can be a solution to restore their valence reputation. Finally, another possible solution is to accentuate the emphasis on a limited and selected set of issues, increasing the party's specialization and the salience of topics on which the party retains a policy‐based valence advantage.

In order to test our hypotheses, we rely on a unique dataset concerning 611 episodes of defection, involving 2,053 legislators, in 14 Western European democracies, from 1945 to 2015, and we combine it with information on party manifestos retrieved from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP, Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2017). Covering 70 years of data and 1,131 manifestos of 135 parties, this work represents the largest empirical study on both the effect of valence advantage/disadvantage on party competition (Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009; Clark, Reference Clark2014) and on the electoral consequences of intra‐party disunity and parliamentary switching (a topic that deserves more attention; see Heller & Mershon, Reference Heller, Mershon, Heller and Mershon2009b), in terms of electoral strategies that political parties could adopt after a valence loss.

The results of our statistical analysis provide support for the argument that parties hit by defections implement strategies aimed at restoring the value of the party's valence attributes. These findings have implications for a wide literature ranging from spatial models of policy competition to valence politics and “core vote” strategies, from issue salience, issue ownership and issue selection, to studies on obfuscation and ambiguity, from intraparty divisions to party switching and party splits.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Internal unity is a valuable asset for a party. First, unity is extremely important for parties’ ability to effectively carry out their policy pledges. Second, unity is also fundamental to ensure the correct functioning of the accountability process: when parties are not united, it becomes very difficult for voters to correctly assess politicians’ responsibilities and to sanction them (Carey, Reference Carey2008). Divisions can alter voters’ perceptions of parties’ competence (Greene & Haber, Reference Greene and Haber2015) and – as a consequence – result in electoral losses (Clark, Reference Clark2009). Disunity harms the value of party labels (Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993) as well: if parties are divided, then voters will be puzzled about future party policy and will not refer to labels as heuristic shortcuts to infer their position in the ideological space. In multiparty systems, the same effect applies not only to voters, but also to potential electoral allies or coalition partners during inter‐party bargaining. Reaching an agreement becomes harder when a party has proved to be internally divided (Ceron, Reference Ceron2016), and potential allies will not deem it trustworthy if it was affected by waves of party switching in the previous parliamentary term. This generates issues of credible commitment during negotiations and a party would need to restore its image in order to become appealing to coalition partners too. Based on these arguments, we assume that defections endanger a party's perceived competence and reputation and – as a consequence – the value of its valence attributes will deteriorate.Footnote 2

Electoral competition is a mix of positional and valence issues (Stokes, Reference Stokes and Kavanagh1992). Positional issues represent a set of alternatives on which voters have different preferences. Valence issues, instead, are topics on ‘which parties or leaders are differentiated not by what they advocate but by the degree to which they are linked in the public's mind with conditions or goals or symbols of which almost everyone approves or disapproves’ (Stokes, Reference Stokes and Kavanagh1992, p. 143). In other words, valence issues are consensual issues (Green, Reference Green2007, p. 629) on which all voters hold identical positions (Clark, Reference Clark2009) and this category also includes non‐policy‐related valence attributes, that is, desirable party characteristics such as honesty, trustworthiness, unity and competence (Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009; Clark & Leiter, Reference Clark and Leiter2014). In this regard, according to Clark (Reference Clark2014), unity is a valence issue because basically any voter would prefer a unified party to a divided one, as intra‐party conflict generates doubt concerning a party's ability to provide a stable and coherent leadership, especially once in government.

The literature on party competition has extensively shown that, apart from positional issues, valence issues are crucial in determining electoral outcomes (Abney et al., Reference Abney, Adams, Clark, Easton, Ezrow, Kosmidis and Neundorf2013). Given that a valence advantage can make the difference in terms of winning or losing an election, valence competition is becoming increasingly relevant nowadays and scholars have started to investigate the relationship between valence and policy strategies. Spatial models to explain party competition in the presence of a valence advantage or a valence loss have been developed (e.g., Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Adams & Merrill, Reference Adams and Merrill2009; Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001; Schofield & Sened, Reference Schofield and Sened2006; Serra, Reference Serra2010).

Starting from a Downsian perspective (Downs, Reference Downs1957), Adams and Merrill (Reference Adams and Merrill2009) investigated whether and how parties adjust and shift their ideological position in reaction to changes in their character‐based valence attributes. Their model relies on the assumption that voters’ evaluations of parties depend on their satisfaction with the parties’ policy positions plus a valence component. According to their model, Adams and Merrill (Reference Adams and Merrill2009) found a centripetal valence effect, suggesting that, as their character‐based valence attributes decline, parties tend to shift toward more moderate policy positions (for a similar conclusion: Serra, Reference Serra2010). Indeed, some empirical studies go in the same direction highlighting a party's incentive to moderate the position on the left‐right scale when its character‐based valence attributes worsen (Clark, Reference Clark2014; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2007).Footnote 3

Still, parties can adopt two different strategies to increase voter's utility and reduce the damage due to defections. On the one hand, parties can reshape their policy platform adopting vote‐maximizing strategies (Abou‐Chadi & Stoetzer, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Stoetzer2020; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Merrill and Grofman2005; Downs, Reference Downs1957), limiting other parties’ ability to drain votes. On the other hand, if valence is endogenous (Serra, Reference Serra2010), parties can work to enhance their reputation that has been damaged by internal splits.

In other words, while the (pre‐campaign) level of a party's valence is fixed, voters’ evaluation of each party's valence can be affected by party strategies taken during the election campaign and outlined in the party manifesto. Instead of hiding from valence competition, parties affected by a valence loss should campaign on valence issues and place greater emphasis on their valence attributes when drafting the party manifesto before the election. Rather than competing only ‘horizontally’ by shifting policy positions, parties can compete ‘vertically’ to restore their reputation. Indeed, Serra (Reference Serra2010) shows that the incentive to invest in valence grows when rival parties retain a comparatively higher level of valence (this is precisely what happens when a party's reputation has been damaged by a loss, becoming relatively lower compared to rival parties). What strategies can be adopted to increase voters’ perception of their valence? We argue that parties have three different opportunities to restore valence, when drafting their electoral manifesto.

To start with, we know that intraparty divisions deteriorate voters’ perceptions of the political authority and competence of a party (Plescia et al., Reference Plescia, Kritzinger and Eberl2021), reducing its electoral support (Greene & Haber, Reference Greene and Haber2015). This also applies to parliamentary defections, as they will impact on party unity and trustworthiness. Consequently, parties can try to restore their valence reputation by presenting themselves as credible and loyal representatives of the will of voters, which keep promises and respect agreements. For instance, after having lost almost one third of its MPs, in the 2015 election the Greek socialist party PASOK presented itself as a party that ‘with clear positions, a specific program and strategy, can meet the challenges, manage the problems and process solutions’.Footnote 4 Similarly, after the switch of 13 per cent of MPs in 2008, in the following election (2011) the Swiss People's Party claimed that the ‘SVP speaks plain text and steers a clear, reliable course. The elected representatives […] have in the past guaranteed that they will consistently deliver on their promises […]’, in addition the ‘SVP Group has called for the disclosure of voting behavior […] so that citizens see their representatives in action and truth: The SVP fights for more openness and transparency’.Footnote 5

This strategy can also represent a form of blame avoidance whenever parties campaign to attack switchers (and their new parties) on valence, blaming them for their lack of integrity and for having betrayed the voter's mandate by splitting away. Indeed, since 1994, Berlusconi repeatedly attacked switchers, calling them ‘traitors’ disloyal to Forza Italia voters. As such, we argue that in their electoral manifestos, parties affected by switches can counter‐attack, emphasizing their own competence to govern and/or the other party's lack of such competence.

HYPOTHESIS 1 (H1): The greater the extent of defections suffered by a party during the previous legislative term, the higher the emphasis on competence in its next electoral manifesto.

Defections might not only harm judgements around party competence but also the value of a party label (Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993), a concept that is extremely important for voters because it helps them to locate parties in the ideological space. When parties are not united, it becomes very hard for citizens to detect their actual positions on different issues. In other words, the party label is a resource from which parties can benefit as long as they are able to maintain unity (Tromborg, Reference Tromborg2021). Uncertainty due to intra‐party divisions and MPs dissent is costly to political parties (Cox & McCubbins, Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Kam, Reference Kam2009). As a consequence, parties hit by switching will also need to restore the value of their ‘brand’.

Parties can try to reach this goal by increasing the clarity of their program rather than presenting ambiguous platforms. It has been argued that, in multiparty systems, parties should take clear positions (Downs, Reference Downs1957, p. 126–127) and a number of studies suggested that ambiguity can be damaging (Alvarez, Reference Alvarez1998; Gill, Reference Gill2005; for a review: Rovny, 2012). Recent empirical analyses, though, highlight that ambiguity can be a rewarding electoral strategy as it allows parties to make broad appeals that convince different groups of voters (Bräuninger & Giger, Reference Bräuninger and Giger2018; Lo et al., Reference Lo, Proksch and Slapin2016; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2015; Rovny, 2012; Tomz & van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Houweling2009). However, the broad appeal strategy can be suitable only in some particular contexts (Han, Reference Han2020; Lehrer & Lin, Reference Lehrer and Lin2020; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2015, p. 844). In fact, it has been argued that intraparty cohesiveness is a necessary precondition for the broad appeal strategy to work, whereas parties can be punished for being ambiguous when they are internally divided (Lehrer & Lin, Reference Lehrer and Lin2020).

While ambiguity can be, overall, a meaningful choice, this is no longer the case for parties hit by out‐switching. These parties, in fact, are faced with problems of credible commitment with respect to both voters and potential allies. If they adopt a broad appeal strategy and make ambiguous policy statements, in the electoral arena they can be subject to attacks from media and rival parties, which will depict these parties as insincere, opportunistic or flip flopping (Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2015). This latter criticism will easily find fertile ground in light of the inconsistent behaviour showed by the party's MPs in the past. Defections of a party's MPs in the previous legislature, in fact, will have generated a reputational damage in terms of reliability (and also increased voters’ information costs: Desposato, Reference Desposato2006).

To overcome this damage, and to reduce the information costs of voters, parties should improve their image by clarifying their policy agenda. Conversely, a manifesto that expresses contradictory statements would be a further signal of indecision and lack of consistency.Footnote 6

HYPOTHESIS 2 (H2): The greater the extent of defections suffered by a party during the previous legislative term, the higher the clarity of its next electoral manifesto.

It has been argued that out‐switching parties might become ideologically more homogenous (Ceron & Volpi, Reference Ceron and Volpi2021; Heller & Mershon, Reference Heller, Mershon, Heller and Mershon2009b), and in turn this can wield effects on ideological clarity. It is worth mentioning, however, that the concepts of ambiguity and position blurring, considered as the misrepresentation of party positions on a number of issues, are distinct from intraparty heterogeneity (Rovny, 2012). According to the literature, in fact, clarity should not be taken as a proxy for party unity. Empirical studies found that, in the eyes of voters, party ambiguity and intraparty conflict are indeed two unrelated phenomena (Lehrer & Lin, Reference Lehrer and Lin2020). Nevertheless, to deal with this potential issue, we will evaluate the relationship between switches and clarity, net of ideological shifts that could have been linked with defections (Heller & Mershon, Reference Heller, Mershon, Heller and Mershon2009b; Levy, Reference Levy2004).Footnote 7

Another strategy that parties can adopt, which combines the policy content of their manifesto with valence‐based concerns, is related to the concept of issue ownership (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). Theories of issue competition suggest that parties selectively emphasize the issues they ‘own’, presenting them as crucial and devoting a large portion of their manifesto to such topics. Parties should boost the salience of issues that are particularly favourable to them because they retain an outstanding reputation and advantageous positions or because the party is viewed as competent on those issues and holds better credentials to address them (Rovny, 2012). Conversely, parties are expected to de‐emphasize issue dimensions that are detrimental, that is, issues on which they are disadvantaged or hold a poor reputation. Indeed, already Budge and Farlie (Reference Budge and Farlie1983) in their seminal paper on issue ownership underline how valence issues can be policy related and, as a consequence, valence and issue ownership are two deeply connected concepts.

Accordingly, the choice to emphasize one or another issue and to focus on a limited and selected number of issues rather than on a broader range of topics can be considered as an heresthetic move (Rovny, 2012); the aim is to direct attention to features on which the party retains a valence advantage due to positive reputation. In light of this, the strategy can be crucial for parties affected by a valence loss. Instead of adopting an issue diversification strategy (Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2015), they can be better off decreasing issue diversity and pursuing core vote strategies (Green, Reference Green2011) to reduce the negative electoral effects of a valence loss (by emphasizing ‘core issues’ on which they are seen as competent on; see also: Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014).

Summing up, we expect that parties hit by a valence damage will reduce their issue diversity (Greene, Reference Greene2016; van Heck, Reference Heck2018) and resort to a core issues strategy as an attempt to specialize on issues in which they retain a valence advantage, vis‐à‐vis their competitors. This will help parties to re‐establish their valence image.

HYPOTHESIS 3A (H3A): The greater the extent of defections suffered by a party during the previous legislative term, the lower the issue diversity in its next electoral manifesto.

HYPOTHESIS 3B (H3B): The greater the extent of defections suffered by a party during the previous legislative term, the higher the emphasis on the party's core issues in its next electoral manifesto.

Data and measurement

To test our hypotheses, we collected original information on party switching in Western Europe to create a new cross‐national database that sheds light on parliamentary defections over a 70‐year period (1945–2015)Footnote 8. We covered the following 14 countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Due to difficulties with data collection, a few Western European countries are excluded from the analysis.Footnote 9 We collected information on switchers from official parliamentary archives and transcripts of legislative sessions (see Supporting Information Table A2.1). In line with the literature (Heller & Mershon, Reference Heller, Mershon, Heller and Mershon2009a), we considered splits, mergersFootnote 10 and start‐ups, as well as all episodes in which legislators took a different label from the one under which they were elected. In these 70 years, in the 14 countries considered, there were 611 annual episodes of defections, involving 2,053 legislators overall. Defections occur more frequently in countries like France, Italy, Norway, Switzerland and Greece. Finland and Ireland have average values close to the mean, while switches are rather rare in Belgium and the Netherlands. At times, switches have been quite frequent also in other countries, namely in Austria (2006), Germany (1951) and Spain (1986, 1989). Across the 14 countries considered in the analysis, we notice that several important parties have been affected by huge levels of party switching, at least occasionally: among them, the Austrian Freedom Party (Austria), the New Flemish Alliance (Belgium), the Socialist Party (France), the Free Democratic Party (Germany), as well as Syriza (Greece), the Fianna Fáil (Ireland), the People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (Netherlands), the Progress Party (Norway), United Left (Spain), the Swiss People's Party (Switzerland) and the Labour Party (UK). Additional details on this database are available in the Supporting Information Appendix (Section 2). To summarize, out of 1,131 observations, in 317 cases, parties witnessed at least one out‐switcher in one legislative term (roughly 30 per cent of the time). Overall, 94 parties out of 135 (70 per cent) have been affected by out‐switching at least once in their lifespans. In this regard, focusing on party switching seems a suitable choice to study how parties react to frequent episodes of disunity.Footnote 11

This new database has been combined with data on party manifestos retrieved from the CMP (now MARPOR: Manifesto Research on Political Representation; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2017). The CMP represents the widest longitudinal and cross‐national study on the content of electoral manifestos drafted by political parties. It provides hand‐coded data on comprehensive and authoritative party statements concerning political positions, policy priorities and electoral strategies at the time of elections. This dataset has been widely used in a number of studies and CMP data has been previously used to test the effect of a valence loss in terms of policy shifts too (Clark, Reference Clark2014).

Our final dataset consists of 1,131 observations related to 135 political parties in 14 West European countries from 1945 to 2015. Each observation corresponds to a single party manifesto; therefore our unit of analysis is at the party‐election level. Our main independent variable, Switches, records the share of MPs that switched‐off from party i in legislature l, at time t – 1. To make sure that the drafting of manifestos was influenced only by defections that took place in the previous legislative term, and not by more long‐standing processes of internal division, we included the share of defections at time t – 2, as a control (the two variables are not correlated with each other).

Given the specific nature of our research design, we tested the impact of Switches on four different dependent variables related to party manifestos (notice that three of them have a similar theoretical range: 0–100). All these variables have been computed using CMP data (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2017) or taking advantage of the ManifestoR package. By doing that, we can map several electoral strategies available to political parties, ranging from valence to policy and issue competition. From our perspective, the content of party manifestos can represent a proxy for the whole strategy that parties will adopt during the electoral campaign to let their views be heard by voters.Footnote 12

We test H1 using Competence as a dependent variable. Competence refers to the share of quasi‐sentences falling into the coding category related to political authority, which contains ‘references to the manifesto party's competence to govern and/or other party's lack of such competence’.Footnote 13 Despite some limitations (Mikhaylov et al. Reference Mikhaylov, Laver and Benoit2012), this variable has been already employed as a proxy for valence issues (e.g., Stoll, Reference Stoll2010)Footnote 14; furthermore, it is particularly suitable in our study as it only refers to general statements on competence that are not related to any specific policy area (non‐policy based valence).Footnote 15Competence ranges from 0 to 57.1 (theoretical maximum: 100; mean: 3.3; SD: 6.4).

To test H2, our dependent variable is Clarity. This index captures the programmatic clarity (Giebler et al., Reference Giebler, Promise Lacewell, Regel, Werner, Merkel and Kneip2018) of party manifestos (rescaled from 0 to 100). The CMP coding scheme contains 13 pairs of antipodal policy (i.e., contains a positive and a negative category for the same policy area). These 13 pairs concern most of the core policy questions in Western European politics, such as, foreign special relationships, military, European Union, internationalism, constitutionalism, political centralization, economic protectionism, welfare state, national way of life, education, multiculturalism, morality and labour groups. Based on this, the index measures the ratio of the absolute difference between positive and negative statements divided by the overall proportion of positive and negative statements made by each party in 13 different policy areas, weighted by salience and party size. In our sample the index (mean: 88.2; sd: 10.8) ranges from 33.3 (little clarity) to 100 (complete clarity). It could be argued that, due to such operationalization, clarity can be lower for centrist parties; however, this index of programmatic clarity is only weakly correlated (r = 0.26) with the absolute value of parties on the left‐right scale. In fact, you can express moderate positions by making contradictory statements on the same topic, but also in many other ways, that is, by making more statements unrelated to left‐wing or right‐wing positions or by taking left‐wing positions on some issues and right‐wing positions on other different issues. To account for this, we test the impact of switches on the programmatic clarity of the party, net of its policy position and net of its potential shift in a more moderate direction. Furthermore, when including the quadratic term of the left‐right scale to discriminate between centrist and non‐centrist parties (Rovny, 2012; van Heck, Reference Heck2018; Zur, Reference Zur2021), all our results hold the same.

Finally, to test H3A and H3B we focus on two different dependent variables: Issue Diversity and Core Issues. Issue Diversity refers to the effective number of manifesto issues (Greene, Reference Greene2016). Higher values indicate that the party has devoted attention to multiple topics, lower values suggest that it has emphasized a limited number of issues. In our sample, this index varies from 2 to 31.5 (mean: 17.8 sd: 5.7). Core Issues (ranging from 0 to 74, theoretical maximum: 100; mean: 27.3 sd: 13.5) accounts for the share of manifesto sentences belonging to the categories associated with the central issues of each party (on which they are seen as competent on: Green, Reference Green2011). Taking our cue from recent studies on the related concept of issue ownership (Ceron & Carrara, Reference Ceron and Carrara2021; Schwarzbözl et al., Reference Schwarzbözl, Fatke and Hutter2020; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014), per each party we derived the list of its core issues based on the attributes of its party family; for the so‐called ‘Special Issue’ parties, we individually assigned to each party the core issues that seemed more crucial for it. Previous studies suggest that issue ownership is quite stable over time and across countries, being a general and long‐term rather than a local and short‐term phenomenon (Seeberg, Reference Seeberg2017). Accordingly, measuring issue ownership or a party's core issues based on the party family affiliation can be a reasonable choice.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, other scholars consider these strategies as more dynamic processes (Damore, Reference Damore2004; Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Nuytemans2009). In view of that, we adjusted the list of core issues related to the social‐democratic family to account for changes after the fall of Berlin's Wall, in an era of welfare state retrenchment; additionally, to account for the transformations of some agrarians parties, the Swiss People's Party in Switzerland and the True Finns in Finland have been considered as nationalist parties (adjusting the list of their core issues accordingly), respectively after 1990 and 1995, when their new leadership changed the nature of these parties pushing them toward right‐wing populist positions (for a similar argument, see Bischof, Reference Bischof2017). For details on the manifesto categories and the issues assigned to each party family see Section 5 in the Supporting Information Appendix. Notice that the average value of Core Issues (27 per cent) is very similar to the findings of previous studies, which indicate that parties devote around 20 per cent of their manifestos to issues they own (Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014).

All the dependent variables are expressed in first difference in the empirical analysis. For each dependent variable, we test the effect of Switches net of a set of control variables (equal for all the dependent variables): Left‐Right, which express the placement of the party on the RILE scale; Government, a dummy variable that takes value of 1 when a party was in government during the previous legislative term and 0 when it was in opposition; Party Size, equal to the share of seats retained by the party during the previous legislative termFootnote 17; Age, the years elapsed from the birth of the party, which is a proxy for party institutionalization; Volatility, which records the total volatility in the election as a proxy for party system institutionalization (Chiaramonte & Emanuele, Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2017); ENPP, the effective number of parliamentary parties (Laakso & Taagepera, Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), which allows us to control for the fragmentation of the party system (an element that is worth taking into account when dealing with party switching). In order to distinguish mainstream and niche parties we also control for Nicheness; for this purpose, we use an index proposed by Meyer and Miller (Reference Meyer and Miller2015) and Bischof (Reference Bischof2017), which measures differences in how parties emphasize niche segments of the policy agenda, compared to their competitors, focusing on a set of issues traditionally identified as core issues for niche parties (Bischof, Reference Bischof2017). Additionally, we control for potential policy shifts in party manifestos through the variables Moderation (which measures the difference between the absolute value of RILE at time t − 1 compared to t, so that positive values indicate more moderation) and Policy Shift, a variable that records the absolute shift on the well‐known RILE scale in the party manifesto at time t compared to its value at time t − 1.Footnote 18

Given that our observations (manifestos) are nested in parties, which are nested in countries, we fit a multilevel linear model to account for the hierarchical structure of the data.

Analysis and results

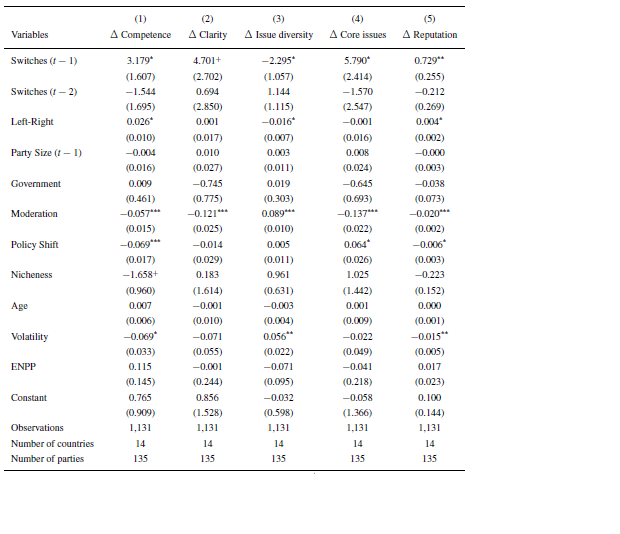

Table 1 displays the results of the statistical analysis. To start with, we find strong support for the link between Switches and competence. In line with H1, we notice that parties affected by switches react by emphasizing their political competence further. Parties suffering from switching will also improve the clarity of their agenda, as suggested by H2, though this coefficient is statistically significant only at the 90 per cent level of confidence. The results support H3A and H3B too. In order to strengthen their valence reputation, parties reduce more the effective number of issues addressed in their manifestos emphasizing a limited number of them; they specialize more in selected topics, sticking to their core issues on which they retain a valence advantage. Interestingly, this latter finding sides with previous studies showing that unpopular parties (which are disregarded by voters: a concept similar to our argument about ‘valence loss/disadvantage’) pursue issue ownership strategies to take advantage of the stronger (perceived) competence on their core issues (Green, Reference Green2011).

Table 1. Multilevel linear regression of Competence (H1), Clarity (H2), Issue Diversity (H3A), Core Issues (H3B) and Reputation, with each dependent variable expressed in difference (between its value at time ‘t’ and at time ‘t − 1’)

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses:

*** p < 0.001,

** p < 0.01,

p < 0.05,

+ p < 0.1.

All the findings point to the fact that parties hit by a valence loss try to remedy such damage by campaigning in a way that will foster their reputation and protect both their image and the value of their party brand. To provide a broader picture, describing the overall behaviour of parties, we add a fifth model in which we analyze the effect of switches on an additional latent dependent variable, Reputation, which is based on the first component of a principal component analysis and records to what extent parties resort to valence and streamline their manifesto (the variable ranges from −3 to 6; mean: −0.1; sd: 1.1). The investment in Reputation is higher for parties that focus more on competence, present a clear manifesto and specialize on a selected number of issues. Indeed, the results of this additional model confirm that an increase in Switches leads to a stronger investment in Reputation.Footnote 19 Summing up, the analysis of party manifestos provides clear support for the idea that parties react to a reputation loss caused by internal defections by campaigning to reinforce their valence attributes.Footnote 20

As we are dealing with observational data, concerns can arise about the risk of endogeneity. In particular, it could be argued that the relationship between party switching and the changes in the valence‐related strategies outlined in the manifestos runs in the opposite direction. In fact, the leadership's attempt to draft a manifesto more focused on valence (with more emphasis on competence, clear stances and a limited number of valence‐rewarding core issues) could trigger internal disagreement and defections. From a theoretical point of view, such reverse causation can be of concern especially with respect to clarity; differently, there are no straightforward theoretical reasons to believe that a focus on competence should produce defections; to the contrary, theoretical arguments have been developed and tested, supporting the idea that a narrow issue agenda (van Heck, Reference Heck2018) and a focus on owned core issues (Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014) should be strategies useful to preserve party unity and avoid defections; vice versa, when leaders are free from internal constraints (this could happen, for instance, after defections) they could invest in a broad agenda and focus on topics outside the set of a party's core issues (Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). These arguments run against the risk of endogeneity.

Nevertheless, in the Supporting Information Appendix (Section 3, Table A3.2) we explore any potential reverse causality proposing a model of defections to shed light on the determinants of party switching. The results suggest that this phenomenon is not explained by changes in the party manifestos linked with the valence‐related factors discussed in our theoretical framework and investigated in our analysis. Conversely, in line with previous studies, our results indicate that switching is explained by factors traditionally deemed relevant by the existing literature on party switching, such as party size, party institutionalization, electoral systems and the form of government (e.g., Mershon & Shvetsova, Reference Mershon and Shvetsova2013, O'Brien & Shomer, Reference O'Brien and Shomer2013). Our valence‐related variables, on the contrary, do not reach statistical significance, suggesting that it is not a turn towards more valence that leads MPs to leave their party. To definitely rule out concerns about endogeneity, Section 4 of the Supporting Information Appendix replicates our results using an instrumental variable approach. Based on our model of defections we estimated the predicted values of switches.Footnote 21 We used this new variable (Switches IV) as an instrument to replace the (potentially endogenous) original independent variable Switches (the correlation between the two is almost 0.7). We then re‐estimated the effect of defections on our four valence‐related outcome variables (see Table A4.1). Switches IV is always significant and in line with the expectations. The impact of defections is slightly more statistically significant when using this instrument. In fact, the effect of Switches IV on Clarity and Core Issues is significant at the 95 per cent level of confidence, while its impact on Competence and Issue Diversity is significant at the 99 per cent level. This further check enhances the robustness of our findings indicating that they are not driven by endogeneity.

Conclusion

We know that party unity impinges on parties’ ability to implement their programs, on their electoral success, and – even more importantly – on the accountability mechanism on which the responsible party government model hinges. As a consequence, disunity and party switching are two potential threats to democratic systems and two challenges to the normative theories of democracy (Desposato, Reference Desposato2006). When politicians change affiliation, voters’ ability to hold their representative accountable is hampered (Mershon, Reference Mershon, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014) and furthermore, party switching damages the meaning of party labels, raises voters’ information costs, and negatively affects party accountability.

From this perspective, the present paper considered party out‐switching as a valence loss for the party's reputation. Indeed, switches can undermine the party's image in many ways, signalling weakness and lack of competence, and an inability to keep the party together or properly select loyal MPs, while the inconsistency due to out‐switching can produce a lack of credibility, lowering the value of party labels.

Focusing on the content of party manifestos, we investigated what electoral strategies parties can adopt to reduce the negative consequences of such valence loss. We argued that parties should try to restore the value of their valence attributes by campaigning on those attributes to prove their competence, consistency, and positive reputation on core issues. We raised several hypotheses and tested them on a unique dataset, which combines CMP data with information on party switching concerning 1,131 manifestos, related to 135 parties in 14 Western European democracies, from 1945 to 2015. The results of statistical analyses suggest that, to restore a party's image that has been damaged by internal defections, parties mainly rely on valence‐related strategies.

Specifically, we observed that in their electoral manifesto, after a valence loss, parties place greater emphasis on their competence to govern the country, enhance the clarity of their policy message, and focus more their attention on a limited and selected number of issues on which they retain a valence advantage. Summing up, after the confusion generated by waves of out‐switching, parties seem to react by trying to defend their valence reputation and invest in that, producing a streamlined manifesto that presents clear positions on a limited number of (rewarding) issues to take advantage of their positive valence reputation in terms of competence, clarity and specialization. By doing that, they hope to restore a positive image of competence, integrity and trustworthiness, which has been weakened and damaged by internal divisions that led to MPs out‐switching.

These findings contribute to the literature on party competition and connect it with studies on electoral campaigns, suggesting that parties respond to a valence loss not only by adopting more rewarding moderate ideological positions (Clark, Reference Clark2014; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2007; notice that this would be unfeasible for centrist parties: Zur, Reference Zur2021), but rather by heavily campaigning on valence issues (this finding is also in line with the theoretical model proposed by Serra, Reference Serra2010). This can be taken as a further signal of the importance of valence competition in everyday politics, and it highlights a link between valence competition, accountability mechanisms and party switching, with implications for normative theories of democracy. Future research can connect these results with recent studies that investigate electoral competition in terms of issue selection (Aragonès et al., Reference Aragonès, Castanheira and Giani2015; De Sio & Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014; Greene, Reference Greene2016).

Our findings also point to a tension between ambiguity and valence competition. While it is true that policy ambiguity can be rewarding from an electoral point of view (Bräuninger & Giger, Reference Bräuninger and Giger2018; Lo et al., Reference Lo, Proksch and Slapin2016; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2015), this strategy might not be the best choice for all parties (e.g., for divided parties: Lehrer & Lin, Reference Lehrer and Lin2020; see also Han, Reference Han2020). In fact, ambiguity can also imply a lack of a clear policy line that could produce a lower perceived valence image among voters, if compared to parties that express clear‐cut positions.Footnote 22 This finding applies pretty well to the electoral campaign conducted by the British Labour Party in 2019. After experiencing the most serious breakaway in 40 years (in February 2019, eight MPs resigned from the Labour Party, in open opposition with the party leadership and in particular with Jeremy Corbyn's ambiguity regarding BrexitFootnote 23), the party did not clarify its position on Brexit and suffered a major electoral defeat in December 2019. To the contrary, Boris Johnson – leader of the Conservative Party – took a clear stance on Brexit (the manifesto started by repeating several times the same sentence, ‘Get Brexit done’, in order to send a clear message) and this turned out to be a winning strategy.Footnote 24 In this regard, the analysis of features that can potentially moderate the effectiveness of ambiguity is a topic that certainly deserves further attention.

Finally, this study can be extended to other contexts of valence loss, such as political scandals, political corruption or leadership failures, and to investigate a party's incentives to compete on the quality of individual candidates. Similarly, this approach can be useful to assess how mainstream parties and populist parties might campaign against each other, evaluating what might happen in case of a valence loss involving one of the two. Another potential avenue for future research would be to analyze the effects that harbouring defectors produces on in‐switching parties, evaluating the campaign strategies adopted by parties that receive switchers and assessing whether they become targets of negative campaigning after getting MPs from other parties. Looking at receiving parties might actually be a promising line of enquiry also to overcome some of the limitations of the data used in this work. It is worth mentioning some limits due to how we conceptualized and, hence, measured switching. In particular, we do not distinguish between different types of defections, and we do not look at where politicians switched to. It could be argued that losing MPs to another party (to its left or to its right) is more damaging than when legislators become independent. While this is a very interesting question to explore, our theoretical argument was about the damage provoked by the amount of switching, not by the direction of these changes. Moreover, with the type of data that we have, that is, aggregated at the party level, it is challenging to incorporate in the analysis the destination of switchers, especially for parties whose defectors joined different groups.

Future research could also investigate intraparty division more broadly, to test how parties react to growing levels of internal heterogeneity and to investigate what electoral strategies can be adopted to contain the negative effect of disunity or, analogously, the argument presented herein can be applied to shed light on electoral strategies after disagreements and defections between partners in coalition governments.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the ECPR General Conference 2018 in Hamburg, the Italian Political Science Association Conference 2018 in Turin, the Manifesto Project User Conference 2019 in Berlin, the Annual Meeting of the Party Congress Research Group (PCRG) 2019 in Glasgow and at the European University Institute in Florence. The authors wish to thank the discussants and all the participants for helpful comments, as well as the editors and the anonymous reviewers. The authors are especially grateful to Nathalie Giger, Roni Lehrer, Thomas Meyer, Carolina Plescia and Bernhard Weßels for their valuable inputs.

Open access funding provided by Universite de Geneve.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information