Introduction

Mycobacterium mucogenicum, like other nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), is ubiquitous in the environment as well as household and hospital potable water, largely due to its relative resistance to chlorine. Reference Covert, Rodgers, Reyes and Stelma1,Reference Wallace, Brown and Griffith2 Contamination of central lines by tap water has been linked to healthcare-associated M. mucogenicum bacteremia. Reference Kline, Cameron and Streifel3–Reference Ashraf, Swinker and Augustino5 More commonly reported, however, are pseudo-outbreaks of M. mucogenicum and other rapid-growing mycobacteria due to ice and tap water contamination of clinical respiratory cultures. Many of these have been associated with bronchoscopy and linked to inadequate disinfection of bronchoscopes. Reference Wallace, Brown and Griffith2,Reference Bardossy, Novosad, Perkins, Moulton-Meissner, Arduino and Benowitz6,Reference Chroneou, Zimmerman and Cook7 More recently, bronchoscopy-related pseudo-outbreaks of Mycobacterium mucogenicum and Mycobacterium chelonae have been linked to the use of non-sterile ice during bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Reference Bringhurst, Weber and Miller8,Reference Engers, Swarup and Morrin9 The clinical and financial impact, however, has not previously been reported.

Our health system, which includes two academic medical centers in Los Angeles, CA (Hospital A and Hospital B), experienced a large pseudo-outbreak of M. mucogenicum from patients undergoing bronchoscopy beginning in 2020. Despite an initial infection prevention (IP) investigation in 2020, the pseudo-outbreak lasted until 2024 when a second IP investigation identified the source of specimen contamination. We describe our IP investigation and mitigation plan and an analysis of the clinical and operational impact of the pseudo-outbreak on our health system.

Methods

Retrospective review of cases

We reviewed the electronic medical records (EMR) of all patients growing M. mucogenicum from BAL cultures obtained in the operating room (OR) of Hospital A during the 15 months prior to our investigation (1/1/2023 to 3/31/2024). For patients with more than one positive BAL culture during this period, only the first case was included in our review. Data regarding patient sex, age, immunocompromised status, Infectious Diseases (ID) referral, diagnostic workup, receipt of antimicrobials, and clinical outcome were abstracted from the EMR. Patients were considered immunocompromised if they had any of the following conditions at the time of bronchoscopy: primary immunodeficiency, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV, with or without antiretroviral therapy), solid organ or bone marrow transplant, hematologic malignancy, active cancer with receipt of chemotherapy within the past 3 months, receipt of corticosteroids (any dose) for>14 days, or receipt of any other immunosuppressive medication at the time of bronchoscopy.

Environmental testing

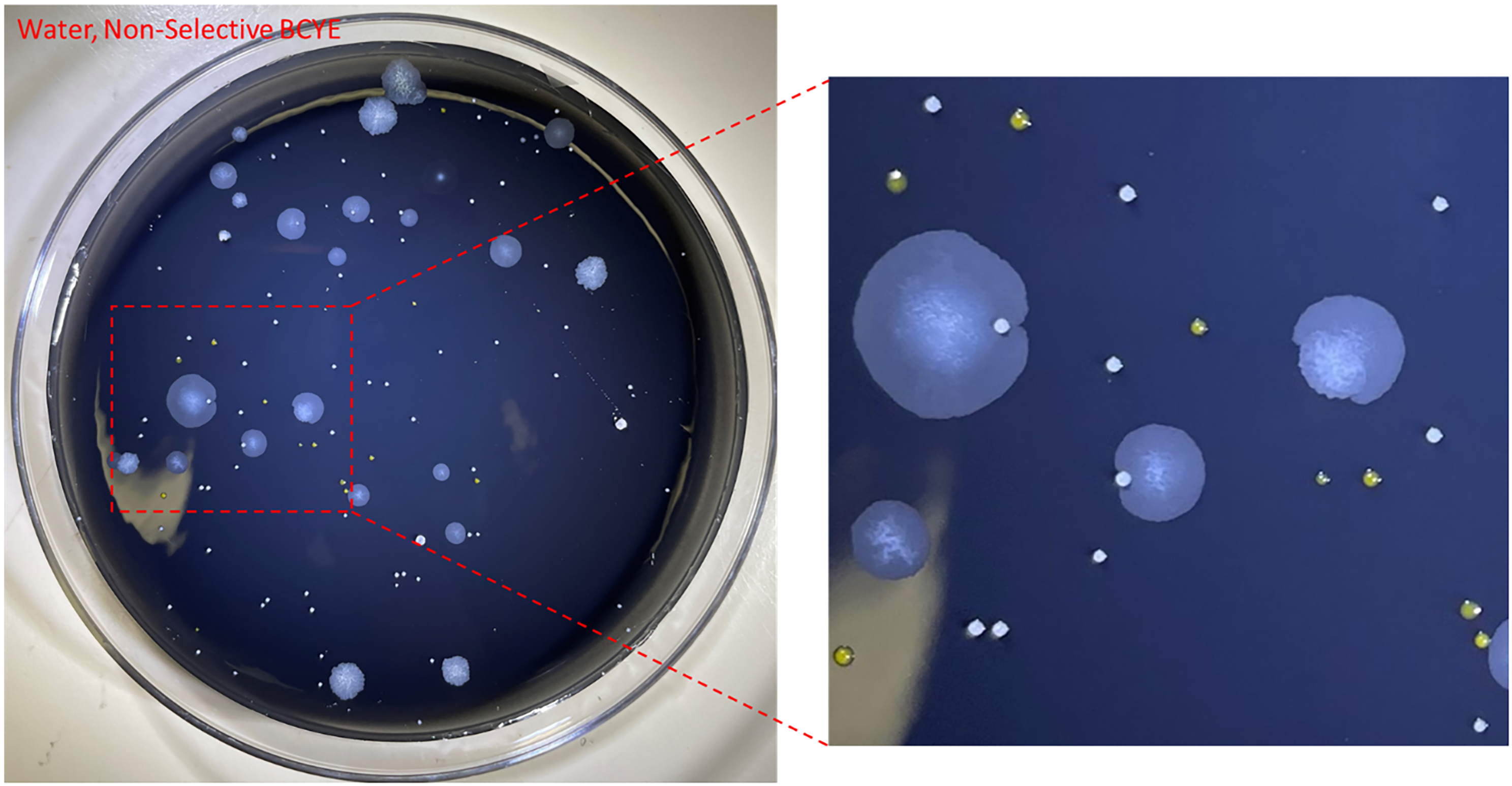

Environmental swabs were collected from both dispenser chutes and drip tray, along with 50 mL water samples from the machine’s input line and melted ice. E-swabs of surfaces and water samples in screw-cap containers were spun in a vortex mixer for 30 s, and 100 µL of each was plated on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) and BCYE select agar—a method adapted from Nocardia culture protocols, as most clinical isolates in this study grew in Nocardia cultures. Standard mycobacterial culture and identification techniques were employed.

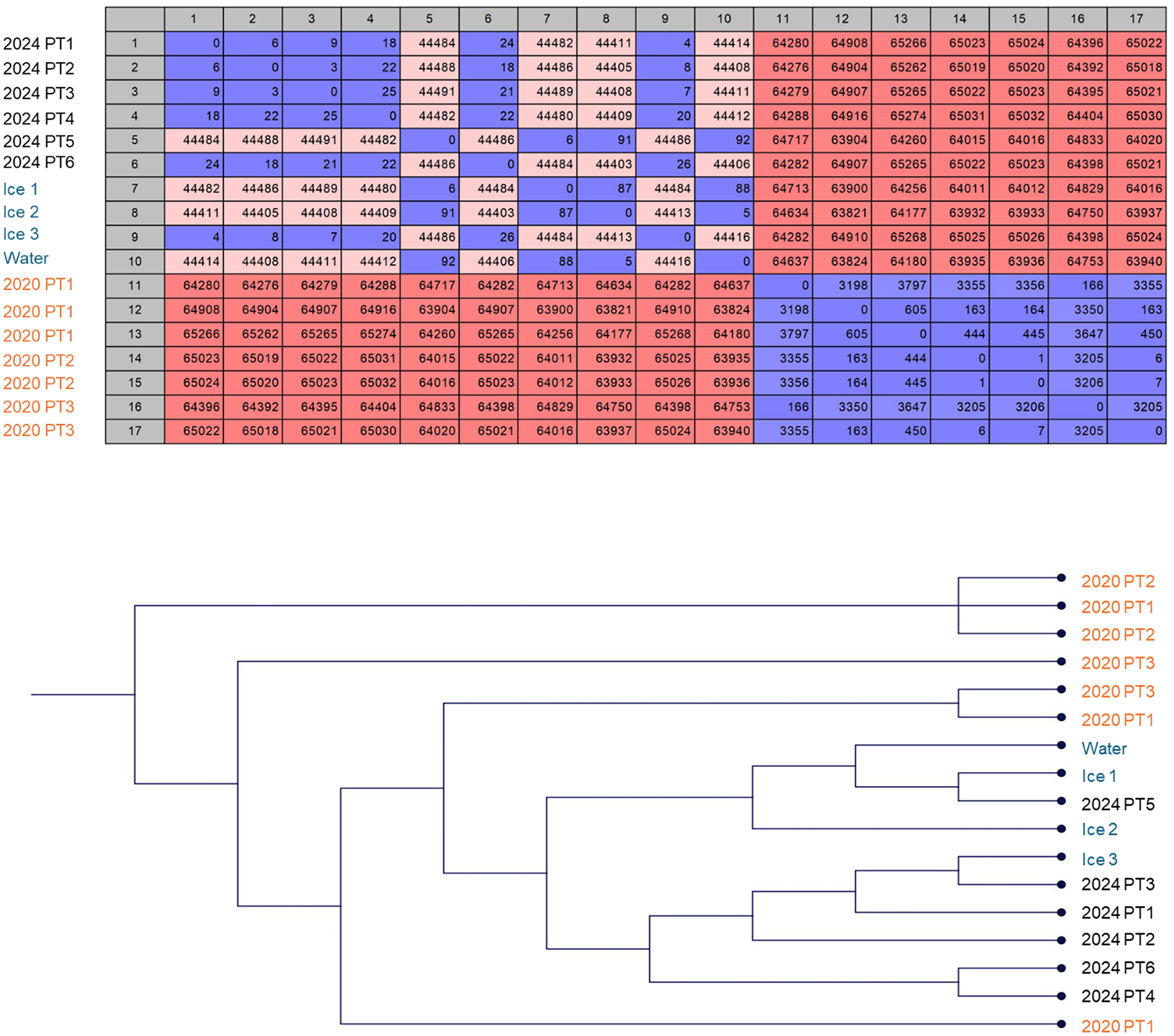

Genetic relatedness analysis of clinical and environmental isolates

Three representative environmental isolates from the ice and one from water culture were analyzed for genetic relatedness to three representative patient isolates from BAL collected on Aug 12, 2020 (at the start of the pseudo-outbreak) and to six clinical isolates collected in April 2024 (at the time of IP investigation) using Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS). Frozen 2020 isolates were revived on BCYE agar and all morphotypes present were sequenced (3, 2, 2 morphotypes respectively) for the completeness of the study. Organism identification was confirmed by MALDI-TOF as well as WGS. The mycobacteria WGS identification workflow on Illumina MiSeq was described previously. Reference Chawla, Shaw and von Bredow10 The whole genome sequences were mapped to the reference genome Mycobacterium mucogenicum ssp. phocaicum NZ_AP022616. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed using CLC Genomic workbench’ s SNP analysis workflow (Qiagen, USA).

Analysis of laboratory and institutional costs

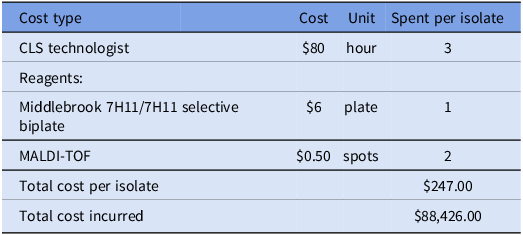

The laboratory cost per isolate was calculated by combining the average hourly wage of a Clinical Laboratory Scientist (CLS) technologist ($80) in Los Angeles and the microbiological reagent cost. Infection prevention effort was calculated by reviewing emails and schedules from the two pseudo-outbreak investigation periods (2020, 2024). The following activities were considered related to the investigation: chart review of reported patients, observations of bronchoscopy procedures, education to perioperative staff, and meetings with the IP, hospital leadership, environmental services, and facilities teams.

Results

Infection prevention investigation and mitigation plan

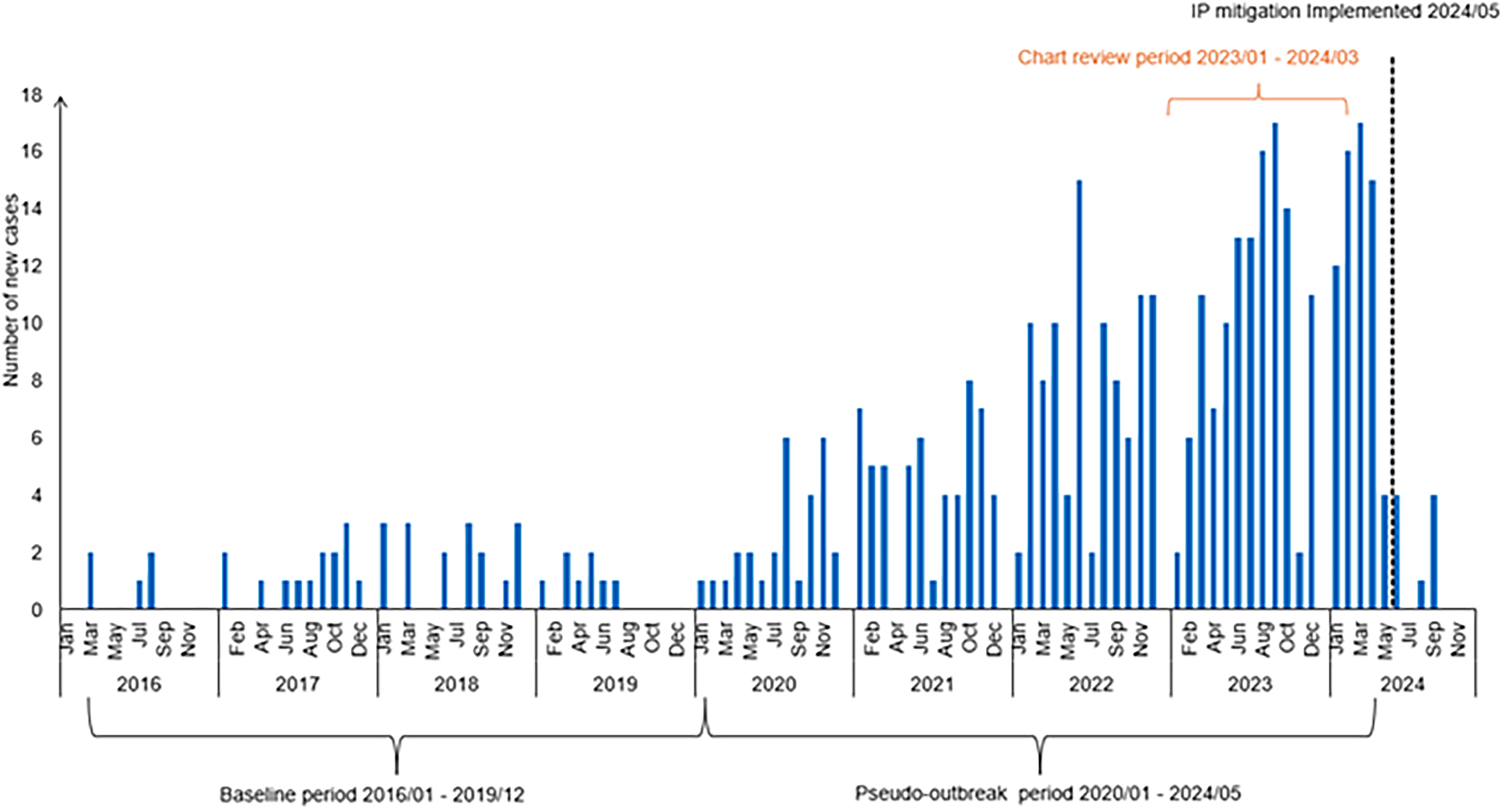

In 2020, the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory notified the IP team about a cluster of M. mucogenicum cases from patients undergoing bronchoscopy in the Hospital A OR. The number of BAL cultures growing M. mucogenicum had increased from five in 2016 to 29 in 2020 (Figure 1). An IP investigation at that time revealed that there were no deficiencies in endoscope reprocessing and that the isolates were not genetically related. Pulmonologists who were interviewed denied the use of non-sterile ice or water during the procedure. Given that the proportion of positive BAL cultures was unchanged between 2016 and 2020 (5.4% vs 6.1%), we concluded that the increase in cases was likely due to an increase in procedure volume and recommended avoiding non-sterile ice or water during BAL.

Figure 1. Epidemic curve of Mycobacterium mucogenicum cases identified in hospital a between 2016 and 2024.

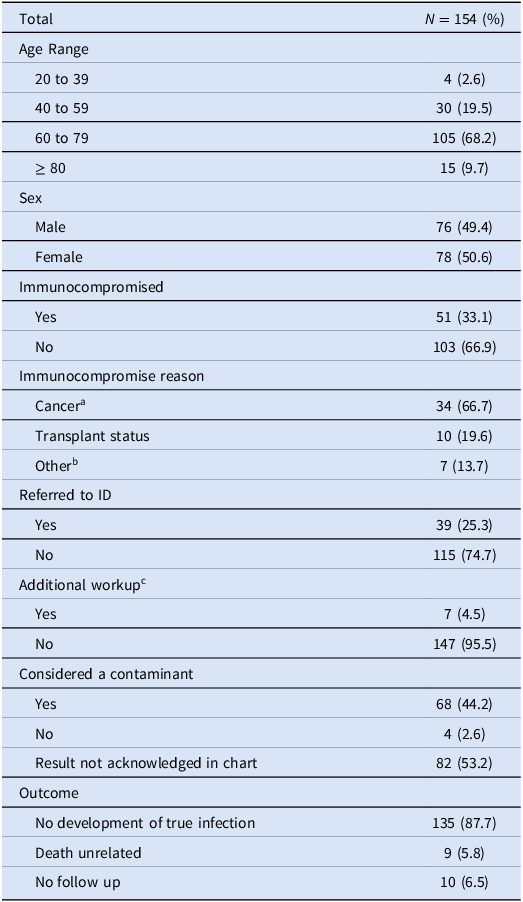

In April 2024, a veteran pulmonologist at Hospital B who recently began performing bronchoscopies at Hospital A notified IP about a high proportion of M. mucogenicum growth from BAL cultures obtained at Hospital A compared to Hospital B. Further investigation revealed a steady increase in M. mucogenicum-positive clinical cultures at our institution from 2016 to 2024, with nearly all cultures being sent from the perioperative area of Hospital A (Figure 1), and a significant difference in the rate of positive perioperative cultures between Hospital A and Hospital B in 2024 (18.6% vs 1.3%). IP observation of bronchoscopies performed in the OR of Hospital A revealed that sterile saline syringes were uncapped and placed in a tub of non-sterile ice for bleeding control during BAL (Figure 2). During BAL, a significant amount of non-sterile ice had melted and mixed with the sterile saline which was then flushed into the patient’s lungs and suctioned back for collection into a sterile cup for culture. The ice used during the procedure came from a single perioperative area ice machine (Scotsman HID540A). A 0.5 µm point-of-use filter was in place between the water inlet pipe and the ice machine. The hospital’s water disinfectant residual levels, pH and temperature were closely monitored during this time and were within goal. Review of cleaning logs revealed no significant gaps in quarterly ice machine disinfection or filter exchange. Visual examination of the ice machine revealed significant corrosion on the ice dispenser chute.

Figure 2. Uncapped sterile saline syringes left in a tub of non-sterile ice for use during bronchoalveolar lavage.

In May 2024, IP met with perioperative leadership to immediately discontinue the practice of placing uncapped sterile saline syringes in a non-sterile ice bath. Hospital A adopted Hospital B’s practice of placing a bottle of sterile saline in a non-sterile ice bath and pouring the chilled sterile saline into a sterile basin to be drawn up with a single-use syringe as needed during BAL. The perioperative ice machine was removed from use and replaced with a new ice machine, new point-of-use filter, and new tubing between the filter and the machine. Routine M. mucogenicum surveillance from BAL cultures was initiated. In the postintervention period from June to December 2024, the proportion of BAL cultures growing M. mucogenicum had decreased to 2% (Figure 1).

Retrospective review of cases

From Jan 2020 to March 2024, 358 BAL cultures obtained from 313 patients in Hospital A’s OR grew M. mucogenicum. Twenty-one patients grew M. mucogenicum twice, five patients grew M. mucogenicum three times each, and two patients grew M. mucogenicum in several cultures (nine and seven, respectively). Most of these patients with two or more positive cultures (20/28) grew M. mucogenicum in different bronchoscopy procedures.

During the 15-month period prior to the outbreak investigation, 154 patients grew M. mucogenicum 160 times from their BAL cultures (Table 1). Notably, nearly all (157/160) of these clinical specimens initially grew M. mucogenicum in nocardia cultures which were then reflexed to acid-fast bacilli cultures. The median age was 69 years (range 21 to 91 years). Immunocompromised patients (33.1%) were more likely to receive an ID referral [OR 2.13, 95% CI (1.008 to 4.5)] (P = .045) but were not significantly more likely to receive additional workup [OR 1.54, 95% CI (0.33 to 7.19)] (P = .58) for their positive culture. The seven (4.5%) patients who received additional workup had repeat CT imaging (5/7), additional AFB cultures sent (2/7) or cell free metagenomic sequencing sent (1/7). One patient was started on antibiotics for M. mucogenicum infection, which were discontinued after a rash developed due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. This patient was later seen by ID and felt to have culture contamination. No patients subsequently developed true infection due to M. mucogenicum.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical data for retrospective case review

a Cancer defined as hematologic malignancy or receipt of chemotherapy within past 3 months.

b Other includes HIV, immunosuppressive medication or on steroids>14 days.

c Additional workup included further imaging, repeat sputum or blood cultures, and Karius testing.

Environmental surveillance and genetic relatedness analysis

From the environmental surveillance, M. mucogenicum was isolated from ice and water supplied to the ice machine but not from the surfaces of the ice dispensing chutes or the drip tray (Figure 3). The environmental and patient isolates were confirmed as M. mucogenicum ssp. phocaicum using WGS. SNP analysis revealed that the environmental isolates were closely related to patient isolates collected in April 2024 (4 to 92 SNPs apart) but not genetically related to the patient isolates from 2020 (>63,000 SNPs apart) (Figure 4). Even among the 2024 samples, two distinctive clusters were noticeable, with the isolates from PT5 closely related to isolates from Ice 1 and 2 and the water sample (6–92 SNPs) while the other cluster comprised isolates from PT1-4 and 6 and Ice 3 (4–26 SNPs). These two clusters were over 44,000 SNPs apart, suggesting a multi-strain reservoir of M. mucogenicum colonizing the ice machine.

Figure 3. Mycobacterium mucogenicum isolated from a perioperative ice machine water source at hospital A. Environmental culture on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) non-selective agar shows M. mucogenicum colonies (large, slightly wrinkled, off-white) alongside other environmental flora (small, yellow or white, convex mucoid colonies).

Figure 4. Genetic relatedness of clinical and environmental isolates. Clinical isolates from 2024, but not 2020, were closely related to environmental isolates collected during the same time in 2024, as demonstrated by whole genome Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) analysis. 2020 patient cultures grew multiple genotypes of M. mucugenicum from a single BAL procedure. A) SNP matrix showing the number of SNP differences between isolates. B) Phylogenetic tree based on the SNP matrix showing the clustering of genetically related isolates.

Analysis of laboratory and institutional costs

We estimated that the cost to the microbiology laboratory for workup of each isolate was $247 and that the total cost during the pseudo-outbreak was $88,426 (Table 2). The cost of replacing the ice machine was $10,086. In addition, approximately 100 hours of infection preventionist time was devoted to the pseudo-outbreak investigation and mitigation.

Table 2. Laboratory cost analysis

Discussion

Bronchoscopy-related pseudo-outbreaks of NTM, including M. mucogenicum, linked to contaminated ice machine ice and water have been previously described; Reference Bringhurst, Weber and Miller8,Reference Engers, Swarup and Morrin9 however, the clinical and financial impacts have not previously been studied. Similar to prior reports, we found that discontinuing the practice of using non-sterile ice and water during these procedures was highly effective at curtailing the pseudo-outbreak. Reference Bringhurst, Weber and Miller8,Reference Engers, Swarup and Morrin9 We also showed that clinical isolates were genetically related to environmental isolates from the ice machine. Our study was much larger than previously reported pseudo-outbreaks, lasting over four years, and involving 313 patients.

Although our institution replaced the entire ice machine, tubing, and point-of-use filter, we suspect that stopping the use of all non-sterile ice or water was the primary intervention responsible for ending the pseudo-outbreak, as NTM is ubiquitous in hospital potable water and difficult to eradicate from ice machines. Reference Covert, Rodgers, Reyes and Stelma1,Reference Cooksey, Jhung and Yakrus11,Reference Hoy, Rolston and Hopfer12 Studies have shown that 61–91% of hospital water and ice are contaminated by NTM, Reference Covert, Rodgers, Reyes and Stelma1,Reference Prabaker, Muthiah and Hayden13 and that concentrations of NTM are significantly higher in ice and water collected from ice machines compared to water in faucets. Reference Cazals, Bédard, Soucy, Savard and Prévost14 The internal water reservoir of an ice machine can promote growth of non-thermophilic NTM given its low temperature and water stagnation. In our study, the WGS of clinical M. mucogenicum isolates from 2020 were unrelated to clinical or environmental isolates from 2024, suggesting that the ice machine was a reservoir for multiple strains of M. mucogenicum. Adherence to standard cleaning and disinfection and point-of-use filter may be insufficient to prevent growth of NTM in ice machine water and ice. In previously reported pseudo-outbreaks, enhanced cleaning of the ice machine alone was unsuccessful in eliminating growth of NTM. Reference Hoy, Rolston and Hopfer12,Reference Gebo, Srinivasan, Perl, Ross, Groth and Merz15 Point-of-use filters with ≤0.2 µm pore size have been recommended to prevent entry of NTM, Reference Norton, Williams, Falkinham and Honda16 but the size of the prefilter between the water inlet pipe and the ice machine at our institution was 0.5 µm. Cazals et al showed that the largest amplification of NTM occurred within the tubing connecting the outlet of the prefilters to the ice machine. Reference Cazals, Bédard, Soucy, Savard and Prévost14 It is interesting that we did not isolate other NTM species in our environmental or BAL cultures, and we hypothesize that this may be due to M. mucogenicum’s ability to grow in cold and in distilled water, as well as its relative resistance to chlorine. Reference Wallace, Brown and Griffith2 Unlike other studies, we did not find a link to contaminated bronchoscopes through inadequate disinfection, Reference Wallace, Brown and Griffith2,Reference Bardossy, Novosad, Perkins, Moulton-Meissner, Arduino and Benowitz6,Reference Chroneou, Zimmerman and Cook7 and our pseudo-outbreak ended without requiring sterilization or removal of bronchoscopes from circulation. We also did not find the ice machine drip tray to be a source of environmental contamination, unlike other studies. Reference Kanwar, Cadnum, Xu, Jencson and Donskey17

Our retrospective review of M. mucogenicum revealed surprisingly few clinical adverse consequences of our pseudo-outbreak, even among a highly immunocompromised population. Only 25.3% of cases were referred to ID for consultation (more likely for immunocompromised hosts), 4.5% had further workup performed, and only one patient was treated unnecessarily with antimicrobials. We believe that this was because the four pulmonologists at Hospital A who commonly perform outpatient bronchoscopy procedures became accustomed to the growth of M. mucogenicum and disregarded these results, either documenting them to be contaminants (44.2%) or not acknowledging the abnormal result (53.2%) in the EMR. Clinical outcomes of other pseudo-outbreaks due to NTM have resulted in unnecessary antibiotic use, complications from antibiotic use, unnecessary respiratory isolation, and prolonged hospital stays. Reference Prabaker, Muthiah and Hayden13,Reference Gebo, Srinivasan, Perl, Ross, Groth and Merz15

The largest impact to our institution from the pseudo-outbreak was on our microbiology laboratory and IP team, given that it cost nearly $90,000 in microbiologist time and supplies, and nearly 100 hours of IP time, which may have diverted resources away from more clinically significant laboratory and quality improvement work. Additional institutional impacts included the $10,000 cost of replacing the ice machine, cost and radiation from repeat imaging, patient anxiety regarding abnormal results, time spent by pulmonologist explaining abnormal results, and unnecessary ID consultations.

It is notable that in nearly all cases, growth of M. mucogenicum was initially seen on nocardia cultures, despite most bronchoscopies being performed for non-infectious workup such as cancer evaluation. Growth of rapidly growing NTM in BYCE medium and not in AFB cultures has been described in prior outbreak investigation of environmental sources of contamination. Reference Chroneou, Zimmerman and Cook7 BYCE is less selective and contains more growth factors compared with conventional AFB media, which likely promoted growth of M. mucogenicum in our pseudo-outbreak. One study showed that a selective rapidly growing mycobacteria medium, which does not require decontamination of clinical specimens, isolated 100% of M. mucogenicum specimens compared with only 6.3% isolated by conventional AFB cultures. Reference Rotcheewaphan, Odusanya and Henderson18 Diagnostic stewardship of nocardia and AFB cultures may have limited the pseudo-outbreak. Recent national guidelines have focused on diagnostic stewardship and recommend against routinely sending respiratory cultures when clinical suspicion for infection is low. Reference Fabre, Davis and Diekema19

The importance of NTM surveillance, in-person IP observations, and leadership engagement must be emphasized because our outbreak continued for four years after the initial investigation and recommendations against using non-sterile ice and water in 2020. We found that pulmonologists performing bronchoscopy at our institution were not aware of sterile saline syringes being placed in non-sterile ice tubs and denied this practice when interviewed in 2020 and in 2024. Current Centers for Disease Control guidelines do not recommend routine NTM surveillance, and only two states (Tennessee and Oregon) require hospital reporting of NTM infections. 20,Reference Bancroft, Shih and Cassidy21 This lack of standardized monitoring may allow similar pseudo-outbreaks and true outbreaks to remain undetected. Some researchers have advocated for routine NTM surveillance as part of a water management program at healthcare facilities. Reference Wallace, Brown and Griffith2,Reference Cazals, Bédard, Soucy, Savard and Prévost14,Reference Klompas, Akusobi and Boyer22

Limitations of our study include its retrospective design and reliance on EMR data which may have resulted in incomplete capture of patient outcomes. We could not account for potential additional workup and treatment for M. mucogenicum that patients may have received at outside institutions. We were also unable to estimate the pseudo-outbreak’s effect on teams outside of Infection Prevention and Microbiology and therefore likely under-estimated the event’s true institutional impact.

This large, four-year pseudo-outbreak of M. mucogenicum highlights several critical points for infection prevention and diagnostic stewardship. In line with other studies, our study underscores the risk of using non-sterile water and ice during bronchoscopy and shows that ice machines can serve as persistent reservoirs of NTM. Although such pseudo-outbreaks may have limited clinical impact, they impose substantial financial and operational burden on the healthcare system. Our findings also emphasize the need for robust surveillance and vigilance in infection control practices. Combining infection prevention interventions through staff education and ongoing surveillance of environmental mycobacterial species recovery on routine culture is essential for preventing similar pseudo-outbreaks.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the UCLA Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Infection Prevention and the UCLA Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, and Molecular Microbiology and Pathogen Genomics (MMPG) Laboratory for their assistance with data collection, genomic analysis, and outbreak investigation.

Financial support

None reported.

Competing of interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.