Introduction

Communication is extending beyond human interactions. Computers have long contributed to content generation and message exchange (Sundar & Lee, Reference Sundar and Lee2022); yet they have previously been constrained by limitations in world knowledge (Broussard, Reference Broussard2018) and linguistic competence (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Wilkes, Elder and Murray1988; Yngve, Reference Yngve1967), which have hindered the potential of human–computer interaction (HCI). The advent of large language models (LLMs) represents a pivotal shift, allowing for authentic, natural language conversations with artificial intelligence (AI; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Choi, Park, Oh and Park2024; Ni & Li, Reference Ni and Li2024). The popularity of interactions with LLMs is on the rise, with these models increasingly integrated into communicative agents such as virtual assistants (Hoy, Reference Hoy2018), companion robots (Irfan et al., Reference Irfan, Kuoppamäki and Skantze2023; Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Hsu, Amon, Chakilam, Chen, Kaufman and Sabanović2023), language teachers (Schmidt & Strassner, Reference Schmidt and Strassner2022), and therapists (Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Henningsen and Buyx2019). This shift highlights the importance of understanding how people perceive and interact with LLMs. While research has shown that people react differently to images and voices generated by LLMs versus those generated by humans (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Segedin and Zellou2019; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Foo, Mewton and Dawel2023; Nightingale & Farid, Reference Nightingale and Farid2022; Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Cohn and Ferenc Segedin2021), whether they also differentially comprehend language from LLMs versus humans remains under-investigated.

Long before the rise of LLMs, the Computers Are Social Actors framework postulates that people increasingly recognized computers as “social actors” (Nass & Moon, Reference Nass and Moon2000). In HCI, people treat computers similarly to their human peers by applying expectations, such as demographic stereotypes (Nass et al., Reference Nass, Moon and Green1997, Reference Nass, Isbister and Lee2000), and social norms including politeness (Kopp et al., Reference Kopp, Gesellensetter, Krämer and Wachsmuth2005; Nass et al., Reference Nass, Moon and Carney1999), reciprocity (Fogg & Nass, Reference Fogg and Nass1997; Moon, Reference Moon2000), and cooperation (Krämer, Reference Krämer2005; Parise et al., Reference Parise, Kiesler, Sproull and Waters1999). Although computers are understood to not to be human, these machines can still elicit in their human interlocutors communicative behaviors and emotional responses typically observed in human–human interaction. The reasons for these seemingly irrational responses—treating inanimate machines as if they possess gender, personality, feelings, and intentions—remain unclear. One explanation is mindlessness (Lee, Reference Lee2008, Reference Lee2010; Nass & Moon, Reference Nass and Moon2000; Sundar & Nass, Reference Sundar and Nass2000): in the context of HCI, people often do not engage in deep, effortful processing regarding the computer’s nonhuman nature and instead fall back on automatic social reactions learned from human–human interaction.

While the literature on human language comprehension demonstrates that listeners attend to the source of a message, using speaker identity and context to inform their expectations and pragmatic inferences (e.g., Noveck, Reference Noveck2018; Rueschemeyer et al., Reference Rueschemeyer, Gardner and Stoner2015; van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008), the mindlessness default in HCI suggests that people may not pay attention to the nonhuman source of language unless they have a specific reason to do so, particularly when a message somewhat contradicts their expectations (Lee, Reference Lee2024). This contradiction leads to a reassessment of the source, influenced by their beliefs (also known as machine heuristics) about what machines are like and how they perform (Molina & Sundar, Reference Molina and Sundar2022; Sundar & Kim, Reference Sundar and Kim2019). Previous research in HCI has shown that these beliefs affect how people respond to machine agents compared to human counterparts (Lee, Reference Lee2024; Liu & Wei, Reference Liu and Wei2018; Sundar & Kim, Reference Sundar and Kim2019; Wang, Reference Wang2021). To maximize the potential for machine heuristics to modulate language comprehension, we utilized semantic and syntactic anomalies. This approach is grounded in two theoretical lines: first, in human studies, anomalies elicit robust event-related potential (ERP) components for comparison; and second, in HCI theory, anomalies serve as the expectation violation predicted to shift participants from the default “mindless” state to an effortful use of source-specific beliefs.

How do people process computer-attributed language versus human language?

Research observed differences between HCI and human–human interaction, particularly regarding linguistic features and the complexity of interactions. People use shorter sentences with less diverse lexical expressions when addressing computers than human peers (Amalberti et al., Reference Amalberti, Carbonell and Falzon1993; Hara & Iqbal, Reference Hara and Iqbal2015; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Wilkes, Elder and Murray1988; Shechtman & Horowitz, Reference Shechtman and Horowitz2003). Such differences suggest that people might perceive computers as linguistically less competent than humans, thus favoring clarity and simplicity over richness and complexity (e.g., Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011). Additionally, people exhibited less politeness toward robots (Kanda et al., Reference Kanda, Miyashita, Osada, Haikawa and Ishiguro2008) and reported feeling less social stress in the presence of computers (Vollmer et al., Reference Vollmer, Read, Trippas and Belpaeme2018).

Studies have further shown that, in HCI, people adapt their language use in light of their beliefs about computer systems. People are more likely to re-use their interlocutor’s prior lexical expressions when addressing computer interlocutors than human interlocutors (Bergmann et al., Reference Bergmann, Branigan and Kopp2015; Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean, Nass and Hu2004, Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011; Shen & Wang, Reference Shen and Wang2023). They also more often re-use a computer’s lexical expressions when communicating with a more basic than more advanced computer, presumably because doing so can help to maximize the likelihood of being understood by a linguistically limited computer (Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Hu, Branigan, Pickering and Nass2006). It is worth noting that people’s tendency to mimic computer-attributed sentence structures has decreased over time. Earlier studies found that people sometimes repeat the sentence structures used by computers more often than those by humans (Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Nass2003). However, more recent research has revealed no such differences (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Branigan, Obregón, Bugis and Beale2015) and even suggested a reversal of this trend (Heyselaar et al., Reference Heyselaar, Hagoort and Segaert2017). These findings indicate a possible decline in aligning syntactic structures with computers as technology has advanced, perhaps reflecting a growing perception of computers as more competent than in the past. The findings that people use their knowledge about their interlocutor to adapt their language production is consistent with the theory that language communication is goal-oriented, with interlocutors comprehending and producing language in a way to maximize communicative success (e.g., Cai et al., Reference Cai, Gilbert, Davis, Gaskell, Farrar, Adler and Rodd2017; Goodman & Frank, Reference Goodman and Frank2016). For example, people construct a model of important demographics of their interlocutor and use such a model to adjust their language output (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Sun and Zhao2021) and constrain their language understanding (Cai, Reference Cai2022; Wu, Duan, & Cai, Reference Wu, Duan and Cai2024), a process known as interlocutor modeling. Extended to HCI, this account suggests that, when interacting with computers, people may modify their language based on their beliefs about computers; in particular, they may accordingly adjust language comprehension and production if they believe that computers tend to be more limited in their linguistic capabilities. Whether and how people also consider the properties of LLMs in human–AI interaction remains an open question.

Do people treat LLMs differently from their human peers?

Previously, computers were regarded as distinct from humans, resulting in people treating them differently while still broadly recognizing them as social actors. Recent developments in generative AI have resulted in AI agents that are “more intimate, proximate, embodied, and humanlike” (Jones-Jang & Park, Reference Jones-Jang and Park2023, p. 1). It is thus interesting to see whether people still distinguish between LLMs and humans.

Research on face science revealed that AI-synthesized faces are indistinguishable from real faces and more trustworthy (Nightingale & Farid, Reference Nightingale and Farid2022). Cabrero-Daniel and Sanagustín Cabrero (Reference Cabrero-Daniel and Sanagustín Cabrero2023) showed that, while most participants acknowledged that LLM-attributed text exhibits gender bias, half of them argued that these AI systems perform as well as or even better than humans in mitigating gender bias. In addition, there is also research showing that LLM-generated narratives could reduce hostile media bias by engaging the machine heuristic, a mental shortcut that causes people to perceive machines as more impartial, systematic, and accurate than humans (Cloudy et al., Reference Cloudy, Banks and Bowman2023). People also have stereotypical expectations regarding LLMs’ consistent performance (i.e., AI systems will perform tasks accurately and reliably every time), leading to frustration when these expectations are unmet. For instance, people often exhibit heightened sensitivity to LLMs’ inconsistencies, resulting in more punitive evaluations of the fairness of their decisions (Jones-Jang & Park, Reference Jones-Jang and Park2023). Additionally, people are still skeptical about LLMs’ ability to fully understand human language and to align with human values, especially on complex social issues (Wu, Xu, et al., Reference Wu, Xu, Xiao, Xiao, Li, Wang and Yang2024).

Beyond general attitudes, emotional responses to LLMs differ from those to humans. Yin et al. (Reference Yin, Jia and Wakslak2024) showed that, after expressing their feelings, participants reported being heard more often if they received responses generated by LLMs than by humans (with response source unknown to participants); however, when the source of response was known, participants reported being heard more often with human responses than LLM-generated responses. These findings suggest that people may perceive LLMs emotionally differently from human interlocutors, even when LLMs can generate well-written responses. Nevertheless, most relevant studies rely on qualitative data, such as ratings, with few directly comparing the real-time mechanisms underlying human–human interaction and human–AI interaction from a neurocognitive perspective. Furthermore, research often overlooks the role of language in human–AI interaction, limiting our understanding of how people comprehend LLM-attributed compared to human-attributed language.

Neural responses to semantic and syntactic anomalies in LLM-attributed text

In this study, we examined people’s brain responses to language attributed to an LLM versus to a human peer, especially when the message or the syntax of the language deviates from people’s expectation (i.e., when sentences contain semantic and syntactic anomalies). This represents a novel area of investigation with limited prior research to guide specific predictions about how people’s neural responses might differ when processing LLM-attributed versus human-attributed anomalies.

Extensive research has employed ERPs to investigate how people respond to semantic and syntactic anomalies in human language. In particular, a semantic anomaly evokes an N400 effect in comprehenders, a negative component peaking around 400 ms after encountering the problematic word. For instance, at reading a sentence such as The Dutch trains are yellow/sour and very crowded, comprehenders show an N400 effect with the word sour (which results in a semantic anomaly) compared to yellow, indicating more cognitive efforts in integrating the meaning of sour into the context (Federmeier & Kutas, Reference Federmeier and Kutas1999; Hagoort et al., Reference Hagoort, Hald, Bastiaansen and Petersson2004; Kutas & Hillyard, Reference Kutas and Hillyard1980; van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Hagoort and Brown1999). A syntactic anomaly, in contrast, evokes a P600 effect, a positive shift starting at around 600 ms after presentation of a syntax-violating word (Hagoort & Brown, Reference Hagoort and Brown2000; Molinaro et al., Reference Molinaro, Barber and Carreiras2011). For instance, in reading The spoilt child throws/throw the toys on the floor, there is a P600 effect at throw compared to throws, indicating more cognitive efforts in re-analyzing or repairing the sentence’s syntactic structure (Hagoort & Brown, Reference Hagoort and Brown2000).

Importantly, these core neural signatures of language processing are modulated by the comprehender’s mental model of their interlocutor. This model encompasses beliefs and expectations regarding the interlocutor’s sociodemographic attributes (van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008), lexical choices (Ryskin et al., Reference Ryskin, Ng, Mimnaugh, Brown-Schmidt and Federmeier2020), syntactic preferences (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Abdel Rahman and Sommer2022), communicative styles (Regel et al., Reference Regel, Coulson and Gunter2010), social connections (Barr et al., Reference Barr, Jackson and Phillips2014), and reliability (Brothers et al., Reference Brothers, Dave, Hoversten, Traxler and Swaab2019). Such modulation results from the integration of linguistic and interlocutor context, which collectively shapes language expectations and interpretation (Hanulíková & Carreiras, Reference Hanulíková and Carreiras2015; van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008; Wu & Cai, Reference Wu and Cai2024, Reference Wu and Cai2025; Wu, Duan, & Cai, Reference Wu, Duan and Cai2024; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Rao and Cai2025). For instance, van Berkum et al. (Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008) showed that comprehenders use their demographic knowledge of the speaker (such as gender, age, and socioeconomic backgrounds) to interpret their sentences; they showed an N400 effect at hearing the sentence If only I looked like Britney Spears spoken in a male voice relative to a female voice. Wu, Duan & Cai (Reference Wu, Duan and Cai2024) further showed that the perceived linguistic capacity of the speaker modulates listeners’ neural signatures in speech comprehension. They found an N400 effect in response to label switching (i.e., when a speaker deviates from an earlier linguistic label in referring to the same thing); more interestingly, they showed that the label switching effect, reflected as N400, was larger when the speaker was a child than an adult, suggesting that people expect children to be linguistically less flexible than adults, thus feeling more “surprised” at label switching by children. Collectively, these findings show that lexical-semantic processing, indexed by the N400, is modulated by the interlocutor context (see also Bornkessel-Schlesewsky et al., Reference Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, Krauspenhaar and Schlesewsky2013; Brothers et al., Reference Brothers, Dave, Hoversten, Traxler and Swaab2019; Foucart et al., Reference Foucart, Santamaría-García and Hartsuiker2019; Foucart & Hartsuiker, Reference Foucart and Hartsuiker2021; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Brisson-McKenna and Phillips2021). While the N400 may reflect low-level processes like semantic retrieval or integration (Baggio & Hagoort, Reference Baggio and Hagoort2011; Kutas & Federmeier, Reference Kutas and Federmeier2011), extensive research has established that this component is sensitive not just to local word-level features (like frequency or association) but also to global contextual constraints. Higher-level information, like the interlocutor context, often overrides the low-level processes (Federmeier & Kutas, Reference Federmeier and Kutas1999; Kutas & Federmeier, Reference Kutas and Federmeier2011; Kutas & Hillyard, Reference Kutas and Hillyard1980). The interlocutor context is also known to modulate the P600 effect associated with both syntactic reanalysis (Caffarra et al., Reference Caffarra, Wolpert, Scarinci and Mancini2020; Hanulíková et al., Reference Hanulíková, Van Alphen, Van Goch and Weber2012; Hanulíková & Carreiras, Reference Hanulíková and Carreiras2015; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Garnsey and Christianson2019) and composition/integration processes (Foucart et al., Reference Foucart, Santamaría-García and Hartsuiker2019; Regel et al., Reference Regel, Coulson and Gunter2010). When the interlocutor is an LLM, we assume that people’s heuristic expectations of LLMs also modulate these neural signatures.

The present study

The present study aims to use ERPs (mainly N400 and P600) to investigate whether people differentially comprehend semantic and syntactic anomalies in text attributed to an LLM versus a human. We report two experiments in Mandarin Chinese examining these questions. In Experiment 1, we examined whether participants exhibited different N400 effects when reading semantically anomalous sentences (relative to semantically coherent counterparts) as LLM-attributed versus human-attributed. In Experiment 2, we examined whether perceived LLM- and human-attributed syntactic anomalies result in different P600 effects. Previous studies have demonstrated that people’s beliefs about machine agents’ properties can modulate how people respond to them (Lee, Reference Lee2024; Liu & Wei, Reference Liu and Wei2018; Sundar & Kim, Reference Sundar and Kim2019; Wang, Reference Wang2021). Based on this, we predicted that people would show different ERP responses to language anomalies when attributed to LLMs versus humans. However, the specific direction of these differences remains exploratory, given the novel context of LLM-attributed language processing. Additionally, previous research has shown that the way people use language with a computer is influenced by the perceived level of “knowledge” the computer possesses (e.g., participants more often lexically aligned with a basic computer than with an advanced computer; Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011). Hence, in both experiments, we also measured participants’ beliefs about the extent to which LLMs possess humanlike knowledge and explored whether these beliefs modulate neural responses to LLM-attributed anomalies.

Experiment 1

We adopted a factorial design of 2 (Anomaly: anomalous vs. control, manipulated within participants and within items) × 2 (Attribution: LLM vs. human, manipulated between participants and within items). Participants read Chinese sentences, one phrase at a time at a rate of 300 ms, that were either semantically anomalous or their control versions (see Table 1); they then decided whether a sentence was sensible or not. In addition, we further attributed sentences to either an LLM or a human being by telling participants, at the start of the experiment, that the sentences they were to read had been produced by either an LLM or a human being.

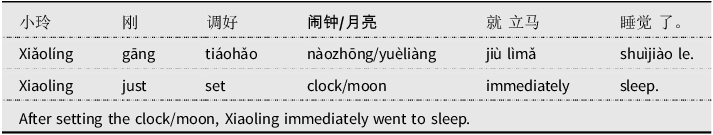

Table 1. An example of the Chinese sentences used in Experiment 1, with glossary and translation. The bolded phrases were the critical region. The spaces in the Chinese text indicate the segmentation of phrases that were presented one at a time during the experiment

Method

Participants

Sixty-four neurologically healthy native speakers of Mandarin Chinese (32 males, mean age = 23 years; SD = 1.98) took part in the experiment. Six of them were later excluded from data analyses (see below), leaving 58 participants. All participants gave their written consent before participating in the experiment. The research methodology and procedures were approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Materials

We created 80 target sentences in Mandarin Chinese, each with a semantically coherent version and a semantically anomalous version (see Table 1), supplemented by 80 fillers (40 containing semantic anomalies and 40 without). The anomalous version was created by replacing the verb-following noun phrase with another noun phrase that is semantically incompatible with the verb (e.g., changing set the clock into set the moon; see Table 1). Both the verb and the critical noun phrases always consisted of two characters. As the anomaly-causing critical noun phrase normally appeared around the middle of the sentence, to avoid attracting participants’ attention to this error location, following Zhu et al. (Reference Zhu, Hagoort, Zhang, Feng, Chen, Bastiaansen and Wang2012), we also included 40 filler sentences with semantic anomalies caused by a word located in various other positions within the sentences. Also, in filler sentences, there were other types of semantic anomalies (e.g., in the prepositional phrase, the adverbial phrase, the adjective phrase) to prevent participants from developing reading strategies. We created two lists of stimuli, each containing 40 semantically coherent sentences, 40 semantically anomalous sentences, and 80 fillers, according to Latin Square Design, such that each experimental sentence only appeared once in a list.

Procedure

Participants were seated in a soundproof booth specially built for EEG experiments. After giving their written consent, half of the participants were assigned to the LLM condition and the other half to the human condition. In the LLM condition, participants were told that they were to read sentences that had been produced by an LLM. To enhance their belief that they would be reading LLM-attributed text, prior to the experiment, participants were asked to first have an interaction in Mandarin Chinese via typing for about three minutes with the LLM (GPT-4). The live interaction was conducted in an in-house interface connected to the API of GPT-4. We prompted the LLM to produce short sentences (without any type of errors) during the interaction to resemble the experimental materials that we used. Participants in the human condition were told that they would be reading sentences that other participants had previously produced for a corpus of human language that we were building. The experiment was implemented using E-Prime 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). A trial began with a visual fixation mark for 500 ms, followed by a sentence presented phrase by phrase. Each phrase remained at the center of the screen for 300 ms, followed by a blank screen for 300 ms. All participants were asked to read the sentence carefully and decide whether the sentence was semantically sensible by pressing a key (F or J on the keyboard) within three seconds. The pairing between the two keys and participant responses (semantically sensible or not) was counterbalanced across participants. The next sentence was presented after a response was made or after the time window expired. As earlier studies have shown that people would adjust their language use depending on their perceived knowledge of computer systems (e.g., Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011), at the end of the experiment, we asked participants to rate the extent to which they perceived LLMs to resemble humans in their knowledge on a 5-point scale (1 = “not similar at all,” 5 = “very similar”).

Data recording and preprocessing

Six participants were excluded from the data analyses either due to an excessively high error rate (over 30%) or more than 30% of the trials being artifact-contaminated, leaving 58 participants for subsequent data analyses (with 29 participants in the LLM and human condition, respectively). The EEG signals were recorded using 128 active sintered Ag/AgCl electrodes positioned according to an extended 10–20 system. All electrodes were referred online to the left earlobe. Signals were recorded using a g.HIamp amplifier and digitalized at a sampling rate of 1200 Hz. All electrodes were kept below the impedance of 30 kΩ throughout the task. The EEG data were preprocessed offline using customized scripts and the FieldTrip toolbox (Oostenveld et al., Reference Oostenveld, Fries, Maris and Schoffelen2011) in MATLAB. The raw data were bandpass-filtered between 0.1 and 30 Hz (Luck, Reference Luck2014; Tanner et al., Reference Tanner, Morgan-Short and Luck2015) and then re-referenced to the left and right earlobes (A1 and A2). For our high-density EEG data, Principal Component Analysis was first applied to the 1–30 Hz filtered continuous data (Luck, Reference Luck2022) to reduce dimensionality to 30 components. Subsequently, Independent Component Analysis was used to identify and remove ocular artifacts. This two-stage approach is common practice for high-density data and artifact correction (Ghandeharion & Erfanian, Reference Ghandeharion and Erfanian2010; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Haufe and Tangermann2011; Wu & Cai; Reference Wu and Cai2025). Then, the data were epoched from 200 ms before the stimulus onset to 1000 ms after the onset. Trials with inaccurate behavioral responses were excluded (4.07%). The epochs containing amplitudes exceeding ±150 μV were excluded as artifacts (3.88%). Finally, the remaining epochs were baseline-corrected by subtracting the mean amplitude from 200 ms to 0 ms prior to the critical word onset. Seventy-five electrodes in the central-parietal region (FCC3h, PPO1h, PPO2h, P1, P2, PPO3h, PPO4h, CPz, Pz, Cz, CCP1h, CCP2h, CPP1h, CPP2h, C1, C2, CP2, CP1, CCP3h, CCP4h, CPP3h, CPP4h, CP3, CP4, T7, C5, C3, C4, C6, T8, TP7, CP5, CP6, TP8, P7, P5, P3, P4, P6, P8, PO7, PO3, POz, PO4, PO8, O1, Oz, O2, FTT7h, FCC5h, FCC1h, FCC2h, FCC4h, FCC6h, FTT8h, TTP7h, CCP5h, CCP6h, TTP8h, TPP7h, CPP5h, CPP6h, TPP8h, PPO7h, PPO5h, PPO6h, PPO8h, POO5, POO1, POO2, POO6, POO9h, OI1h, OI2h, POO10h) were selected for statistical analysis, covering central and parietal scalp regions related to the observation of the N400 component in previous studies (Hahne & Friederici, Reference Hahne and Friederici2002; Kutas & Van Petten, Reference Kutas, Van and Gemsbacher1994). We preserved the data of each channel (instead of collapsing the mean amplitudes within the ROI) for each trial to conduct channel-level analyses. This allowed us to include Channel as a random effect in the subsequent linear mixed-effects (LME) models, following the methodology of recent studies (Lenzoni et al., Reference Lenzoni, Sumich and Mograbi2024; Ryskin et al., Reference Ryskin, Stearns, Bergen, Eddy, Fedorenko and Gibson2021; Volpert-Esmond et al., Reference Volpert-Esmond, Merkle, Levsen, Ito and Bartholow2018; Wu & Cai, Reference Wu and Cai2025).

Results and discussion

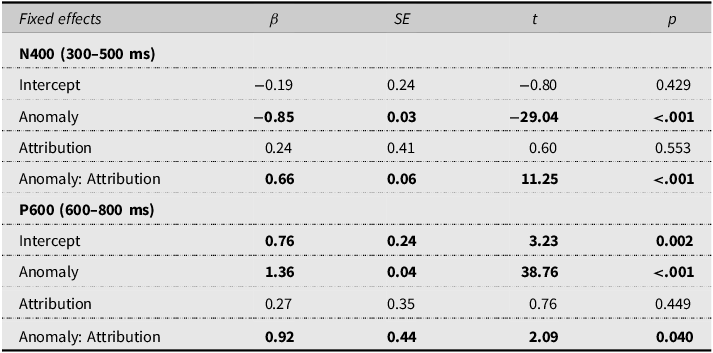

We focused on the classic time window of the N400 effect, namely, 300–500 ms (see also van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Brown, Zwitserlood, Kooijman and Hagoort2005). We fit LME model to the mean amplitudes extracted over the target time windows for each channel of each trial, with Anomaly (control = −0.5, anomalous = 0.5), Attribution (human = −0.5, LLM = 0.5), and the interaction between them as fixed effects. We included Participant, Item, and Channel as random effects (See Table 2 for the full model structure). For all LME analyses, we used the maximal random-effect structure justified by the data and determined through forward model comparison (α = 0.2; Matuschek et al., Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017).

Table 2. LME models for by-trial amplitude analysis across the centro-parietal sites

Notes: The model for N400 analysis: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Attribution + (1|Participant) + (1|Item) + (Attribution + 1|Channel); the model for P600 analysis: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Attribution + (1|Participant) + (Anomaly : Attribution +1|Item) + (Anomaly : Attribution + Attribution + 1|Channel). Significant and marginally significant results are marked bold.

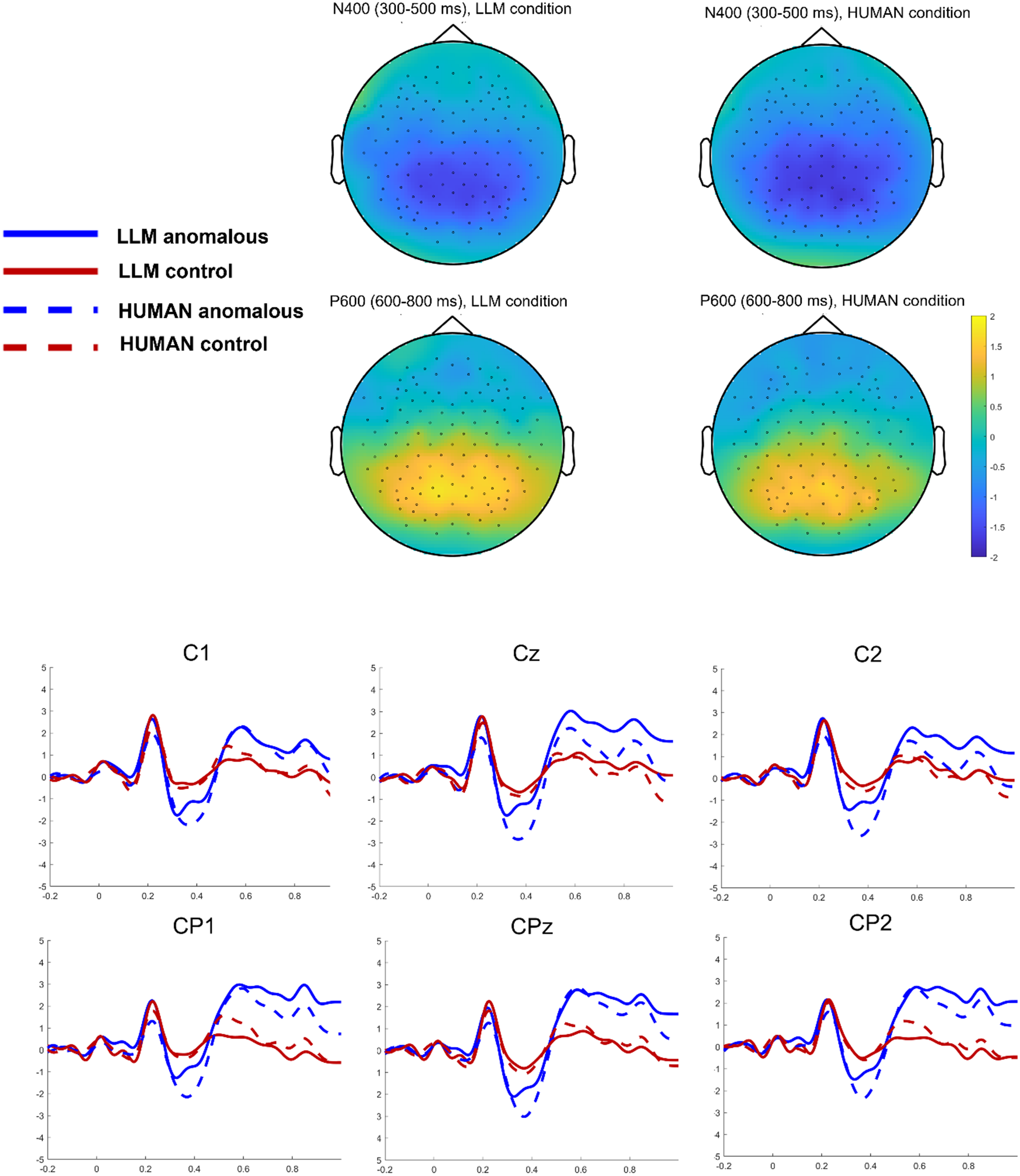

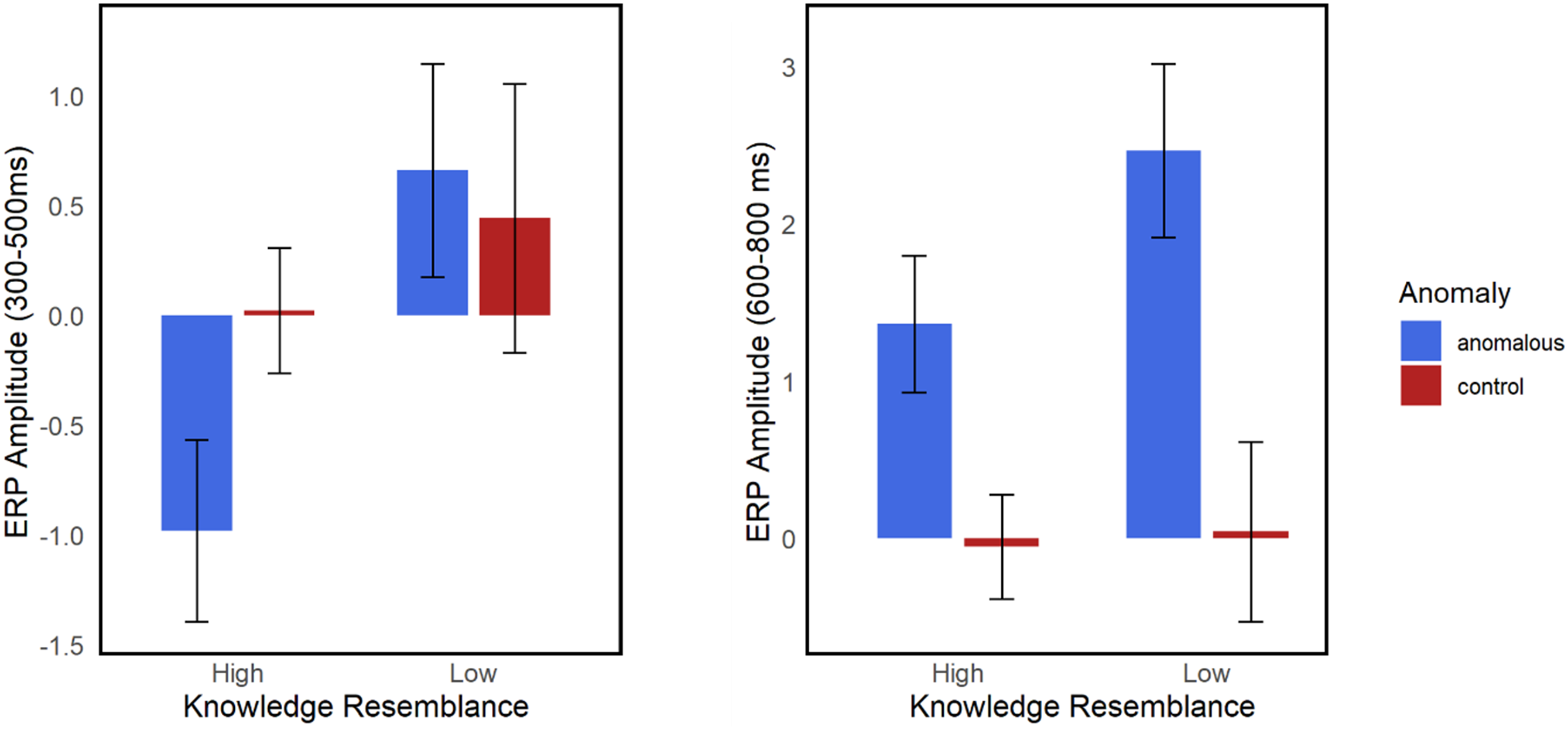

Table 2 presents the LME results for by-trial amplitude analysis in the time window of 300–500 ms. There was a significant main effect of Anomaly, with more negative amplitudes in the semantically anomalous condition (M = −0.63 µV) compared to the semantically coherent condition (M = 0.23 µV) during the time window of 300–500 ms (see also Figure 1). The interaction between Anomaly and Attribution was significant. Simple-effect analysis showed that in the LLM condition, the amplitudes were significantly more negative for semantically anomalous sentences (M = −0.35 µV) than for semantically coherent sentences (M = 0.22 µV, β = −0.49, t = −11.73, p < .001). In the human condition, the amplitudes were significantly more negative for semantically anomalous sentences (M = −0.90 µV) than for semantically coherent sentences (M = 0.23 µV, β = −1.16, t = −28.77, p < .001). These results suggest that the N400 effect was weaker in the LLM condition (−0.57 µV) than in the human condition (−1.13 µV).

Figure 1. Grand average ERPs elicited by the semantically anomalous sentences and the semantically coherent sentences in the LLM and human conditions. Waveforms are illustrated with six centro-parietal sites C1, Cz, C2, CP1, CPz, and CP2.

Additionally, our analysis revealed an unexpected pattern in the 600–800 ms time window. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, there was a significant main effect of Anomaly, with more positive deflections in the semantically anomalous condition (M = 1.43 µV) than in the semantically coherent condition (M = 0.09 µV), suggesting the presence of a P600 component in response to semantic anomalies. The interaction between Anomaly and Attribution was significant. Simple-effect analysis showed that in the LLM condition, the amplitudes were significantly more positive for semantically anomalous sentences (M = 1.77 µV) than for semantically coherent sentences (M = 0.02 µV, β = 1.82, t = 35.91, p < .001). In the human condition, the amplitudes were significantly more positive for semantically anomalous sentences (M = 1.09 µV) than for semantically coherent sentences (M = 0.15 µV, β = 0.91, t = 18.55, p < .001). These results indicate that the P600 effect was larger in the LLM condition (1.75 µV) than in the human condition (0.94 µV).

As previous research has shown that the way people use language with a computer is influenced by the perceived level of “knowledge” the computer possesses (e.g., Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011), we fit LME models on data from the LLM condition with Anomaly and Knowledge Resemblance as interacting fixed effects (see Table 3 for model structures) to investigate whether the perceived resemblance in knowledge between LLMs and humans could predict the N400 effect and the P600 effect in the LLM condition. During 300–500 ms, the results revealed a significant interaction between Anomaly and Knowledge Resemblance, such that higher perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans predicted a larger N400 effect when people believed they were reading semantic anomalies from an LLM (see Figure 2). Additionally, during 600–800 ms, the interaction between Anomaly and Knowledge Resemblance was significant, such that higher perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans predicted a smaller P600 effect when people believed they were reading semantic anomalies from an LLM (see Figure 2).

Table 3. LME models for by-trial amplitude analysis of knowledge resemblance in the LLM condition

Notes: The model for N400 analysis in the LLM condition: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Knowledge Resemblance + (1|Participant) + (1|Item) + (1|Channel); the model for P600 analysis: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Knowledge Resemblance + (1|Participant) + (1|Item) + (1|Channel). Significant and marginally significant results are marked bold.

Figure 2. Mean ERP Amplitude in the LLM condition for high versus low knowledge resemblance across semantically anomalous and control conditions.

Experiment 1 showed that semantically anomalous sentences, relative to semantically coherent ones, elicited an N400 effect. Notably, the N400 effect was reduced when the semantic anomaly was believed to be produced by an LLM compared to by a human being, which suggests that participants seemed to be more accommodating with LLM-attributed semantic anomalies than with human-attributed ones. The difference in the N400 effects largely reflects the modulation of participants’ expectations about the attributed interlocutor (LLM vs. human). While our stimuli used strong semantic incoherence, which differs from prototypical LLM hallucinations (i.e., coherent but factually false propositions), we interpret the reduced N400 amplitude as stemming from a broader expectation about the source rather than a direct expectation of this specific type of failure. This modulation may be driven by two related factors. First, the widely publicized factual unreliability of LLMs, of which hallucination is a prime example (Maynez et al., Reference Maynez, Narayan, Bohnet and McDonald2020; Rawte et al., Reference Rawte, Sheth and Das2023), may prepare people to anticipate a wider range of unpredictable semantic outputs. Second, participants are likely to have some understanding that LLMs, unlike humans, do not possess genuine world knowledge. This general awareness, gained through media coverage or personal experience with AI limitations, could lead them to view any semantic failure, including the strong incoherence in our materials, as a more predictable outcome of the system. Consequently, LLM-attributed semantic anomalies become more predictable and are thus better tolerated. This is further supported by the observation that the N400 effect to LLM-attributed semantic anomalies increased as a function of the extent of perceived humanlike knowledge of LLMs. This suggests that LLM-attributed semantic anomalies are less predictable or worse tolerated by participants if they believed to a greater extent that LLMs have humanlike knowledge.

Moreover, semantically anomalous sentences elicited a follow-up P600, compared to semantically coherent ones. Nevertheless, the P600 effect to LLM-attributed semantic anomalies was larger compared to that to human-attributed anomalies. Recent research has linked the P600 effect to composition or integration processes (Brouwer et al., Reference Brouwer, Fitz and Hoeks2012; Baggio, Reference Baggio2018, Reference Baggio2021; Fritz & Baggio, Reference Fritz and Baggio2020, Reference Fritz and Baggio2022). Baggio (Reference Baggio2018) proposes that the P600 reflects formal operations at the syntax–semantics interface, which can be driven by two distinct mechanisms. First, it can represent a top-down influence where a compelling semantic interpretation affects the perception of syntactic form. Alternatively, it can index bottom-up, syntax-driven meaning composition when a rich semantic context is absent, thus forcing the system to engage in resource-intensive structural computation. Therefore, this framework predicts that the amplitude of the P600 component will be modulated by the difficulty of composition/integration. Our results thus indicate that LLM-attributed semantic anomalies were harder to compose or integrate compared to human-attributed anomalies. Moreover, our results showed the P600 effect to LLM-attributed semantic anomalies decreased as a function of the extent of humanlike knowledge participants attributed to LLMs. This suggests that LLM-attributed semantic anomalies are easier to compose or integrate if participants believed to a greater extent that LLMs have humanlike knowledge. The complementary pattern of larger N400 and smaller P600 effects in participants with stronger beliefs in LLM humanlike knowledge demonstrates that people attributing more humanlike knowledge to LLMs employ cognitive mechanisms more similar to human–human communication when processing LLM semantic anomalies.

Experiment 2

We switched to syntactic anomalies, with a similar design as in Experiment 1: 2 (Anomaly: anomalous vs. control, manipulated within participants and within items) × 2 (Attribution: LLM vs. human, manipulated between participants and within items). In particular, we manipulated whether a sentence is syntactically anomalous or well-formed (in the control condition).

Method

Participants

Another 64 neurologically healthy native speakers of Mandarin Chinese (27 males, mean age = 24 years; SD = 2.50), who had not taken part in Experiment 1, participated in the experiment. Eight of them were later excluded from data analyses (see below), leaving 56 participants. Participants gave their written consent before participating in the experiment.

Materials

We created 80 target sentences in Mandarin Chinese, each with a syntactically well-formed version and a syntactically anomalous version (see Table 4), following the previous research (Hao et al., Reference Hao, Duan, Zha and Xu2024; Qiu & Zhou, Reference Qiu and Zhou2012). Mandarin Chinese has a limited range of grammatical inflections compared to Indo-European languages, lacking grammatical morphology that denotes syntactic categories or features (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yu and Boland2010). Nevertheless, people can determine grammatical relations among sentence constituents through nuanced interactions of lexical semantics, grammatical particles, and discourse principles. In terms of tense, Chinese verbs are not morphologically marked but can be paired with temporal adverbs and a few aspectual particles to convey temporal references (Dai, Reference Dai1997). We made use of the syntactic agreement between the temporal phrase and the aspectual particle guo (indicating a discontinued prior experience). In simplex sentences (e.g., Table 4), guo typically indicates completed past events, functioning similarly to a past tense marker (Lin, Reference Lin2003). When an event (indicated by the temporal phrase) occurs in the past, then one can use the verb with the aspectual particle guo (e.g., zuótiān, xiǎomíng chī-guò hànbǎo le, jīntiān jiù bù le, meaning “Yesterday, Xiaoming ate a hamburger and he will not eat one today”), but if the event is yet to occur, then the aspectual particle cannot be used with the verb (e.g., míngtiān, xiǎomíng chī-guò hànbǎo le, jīntiān jiù bù le, meaning “Tomorrow, Xiaoming ate a hamburger and he will not eat one today”). The P600 effect observed by Qiu and Zhou (Reference Qiu and Zhou2012) and Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Duan, Zha and Xu2024) using this paradigm confirms that this temporal disagreement constitutes a syntactic violation. To ensure economical and incremental parsing (Frazier & Fodor, Reference Frazier and Fodor1978; Konieczny, Reference Konieczny2000), our sentences followed a high-frequency sequence: temporal phrase + subject + verb-particle structure. This word order allows immediate resolution to a simplex main clause upon encountering the subject and verb, minimizing sustained local ambiguity and isolating processing costs to the temporal agreement violation. We created 80 syntactically well-formed sentences expressing an event in the past (as indicated by the use of temporal phrases such as zuótiān, meaning “yesterday”); then, we modified these sentences into syntactically anomalous ones by changing the temporal phrase into a future one (e.g., míngtiān meaning “tomorrow”). To prevent participants from relying on the initial temporal phrase as a deterministic cue for the guo violation, we implemented a balanced filler design similar to Liang et al. (Reference Liang, Chondrogianni and Chen2022). Specifically, we included 80 filler sentences (40 syntactically well-formed, 40 with different nontemporal syntactic anomalies such as improper word order, missing components, or incorrect demonstratives). No fillers contained the target temporal agreement violation. Crucially, to decouple the initial temporal phrase from the target syntactic violation, these 80 fillers were balanced to begin with future-tense, present-tense, and past-tense temporal phrases. This balanced filler design ensured that a future-tense phrase had no statistical relationship to the subsequent guo violation, thereby requiring participants to process the full sentence structure for grammaticality. We created two lists of stimuli, each containing 40 syntactically well-formed sentences, 40 syntactically anomalous sentences, and 80 fillers, according to Latin Square Design, such that each experimental sentence only appeared once in a list. The presentation of stimuli was the same as Experiment 1.

Table 4. An example of the Chinese sentences used in Experiment 2, with glossary and translation. The bolded phrase was the critical region. The spaces in the Chinese text indicate the segmentation of phrases that were presented one at a time during the experiment

Procedure

Participants were asked to read the sentence carefully and decide whether the sentence was syntactically well-formed within three seconds. Other procedures were the same as Experiment 1.

Data recording and preprocessing

Eight participants were excluded from the data analyses either due to an excessively high error rate (over 37.5%) or more than 30 trials being artifact-contaminated, comprising approximately 37.5% of the total trials, leaving 56 participants for subsequent data analyses (with 29 in the LLM condition and 27 in the human condition). Data recording and preprocessing were the same as Experiment 1. Trials with inaccurate behavioral responses were excluded (9.55%). The epochs containing amplitudes exceeding ±150 μV were excluded as artifacts (6.06%). We selected 75 electrodes in the central-parietal region, consistent with Experiment 1, for statistical analysis, covering central and parietal scalp regions related to the observation of the P600 component in previous studies (e.g., Hagoort & Brown, Reference Hagoort and Brown2000; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Duan, Zha and Xu2024; Hinojosa et al., Reference Hinojosa, Martín-Loeches, Casado, Munoz and Rubia2003; Qiu & Zhou, Reference Qiu and Zhou2012).

Results and discussion

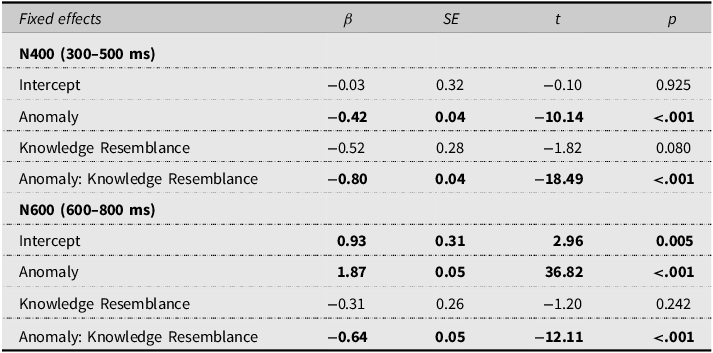

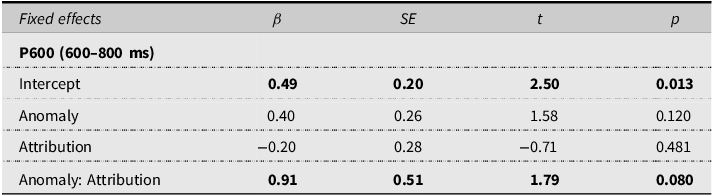

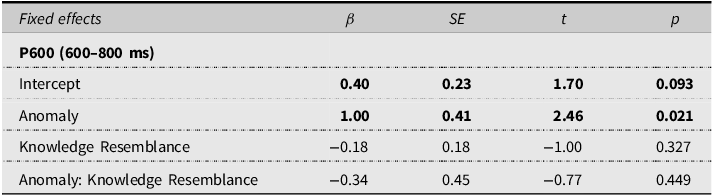

We focused on the classic time window of the P600 effect, namely, 600–800 ms (see also Nevins et al., Reference Nevins, Dillon, Malhotra and Phillips2007; Vissers et al., Reference Vissers, Virgillito, Fitzgerald, Speckens, Tendolkar, van Oostrom and Chwilla2010). We fit LME models to the mean amplitudes extracted over the target time windows for each channel of each trial, with Anomaly (control = −0.5, anomalous = 0.5), Attribution (human = −0.5, LLM = 0.5), and the interaction between them as fixed effects. We included Participant, Item, and Channel as random effects (see Table 5 for the full model structures).

Table 5. LME models for amplitude analysis across the centro-parietal sites

Notes: The model for P600 analysis: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Attribution + (Anomaly + 1|Participant) + (1|Item) + (Attribution + 1|Channel). Significant and marginally significant results are marked bold.

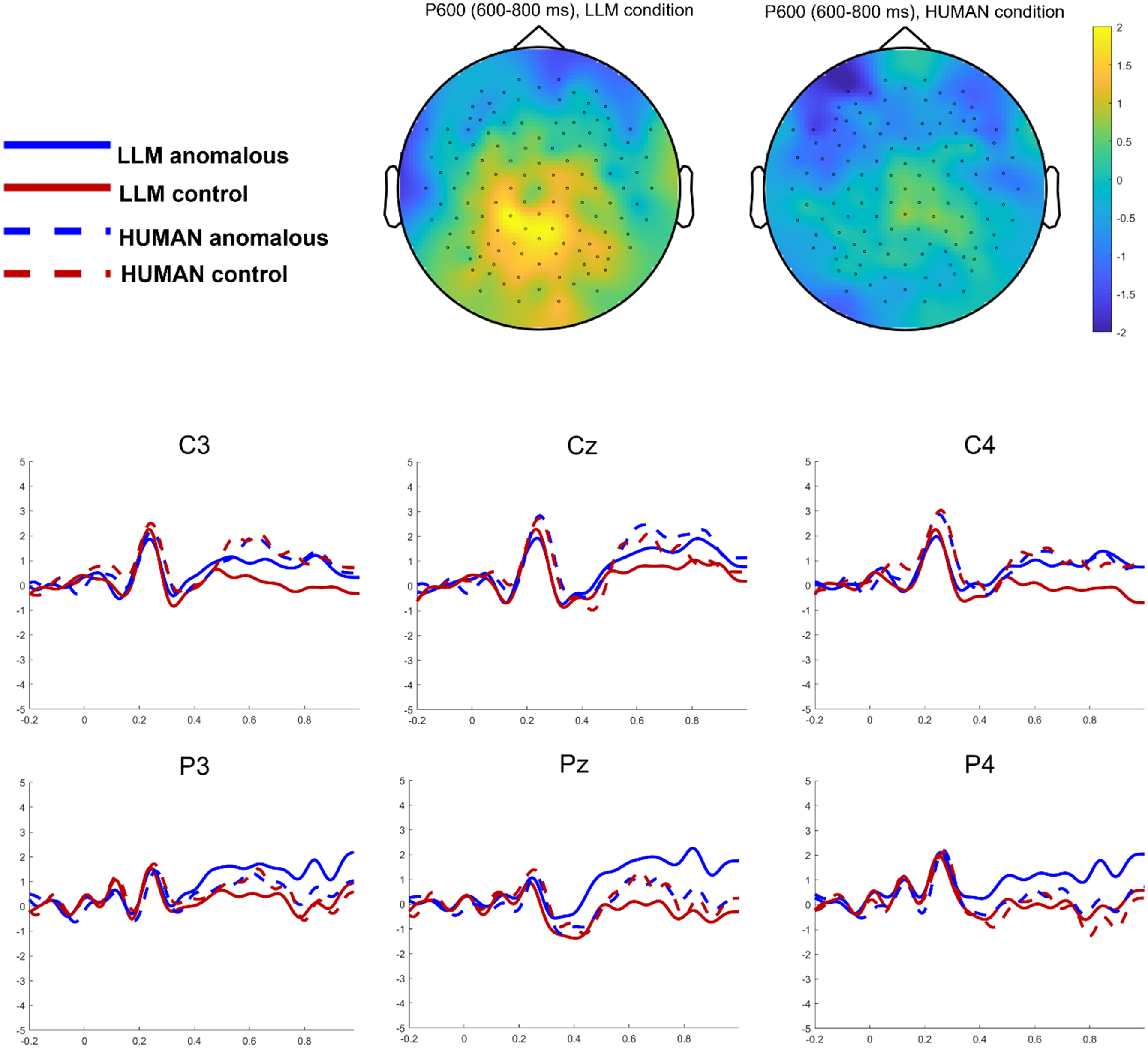

Table 5 presents the LME models for by-trial amplitude analysis during 600–800 ms. There was a marginally significant interaction between Anomaly and Attribution (see also Figure 3). Simple-effect analysis showed that in the LLM condition, the amplitudes were significantly more positive for syntactically anomalous sentences (M = 0.88 µV) than for syntactically well-formed sentences (M = 0.01 µV, β = 0.97, t = 2.41, p = .023). In the human condition, the amplitudes were comparable (β = −0.08, t = −0.15, p = .884) for syntactically anomalous sentences (M = 0.61 µV) and syntactically well-formed sentences (M = 0.57 µV).

Figure 3. Grand average ERPs elicited by the syntactically anomalous sentences and syntactically well-formed sentences in the LLM and human conditions. Waveforms are illustrated with six centro-parietal sites C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4.

Moreover, to investigate whether perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans modulates the P600 effect to LLM-attributed syntactic anomalies, we fit LME models on data from the LLM condition with Anomaly and Knowledge Resemblance as interacting fixed effects (see Table 6 for model structures). The results showed the interaction between Anomaly and Knowledge Resemblance did not reach significance, indicating that perceived knowledge resemblance does not modulate the P600 effect to syntactic anomalies from LLMs.

Table 6. LME models for by-trial amplitude analysis of knowledge resemblance in the LLM condition

Notes: The model for P600 analysis in the LLM condition: Amplitude ∼ Anomaly * Knowledge Resemblance + (Anomaly + 1|Participant) + (1|Item) + (1|Channel). Significant and marginally significant results are marked bold.

The results of Experiment 2 demonstrate that syntactic anomalies in LLM-attributed text elicited a robust P600 effect, whereas those in human-attributed text did not. The P600 effect is an ERP component associated with increased cognitive efforts in detecting syntactic errors and performing syntactic integration (Hagoort & Brown, Reference Hagoort and Brown2000; Molinaro et al., Reference Molinaro, Barber and Carreiras2011). This indicates that participants exerted more cognitive efforts when processing syntactic anomalies in language attributed to LLMs, likely due to an expectation that LLMs should have high syntactic capabilities. In contrast, when they realized that those syntactic anomalies were attributed to humans, they processed them more effortlessly, as they did not hold the same high syntactic expectations for humans.

More recent research suggests that the P600 effect reflects domain-general composition or integration difficulty at the syntax–semantics interface (Baggio, Reference Baggio2018, Reference Baggio2021; Brouwer et al., Reference Brouwer, Fitz and Hoeks2012; Fritz & Baggio, Reference Fritz and Baggio2020, Reference Fritz and Baggio2022). Accordingly, there is another interpretation of this result. Experiment 2 reveals that integration processes are modulated by the interlocutor context. The enhanced P600 for LLM-attributed syntactic anomalies reflects additional efforts to assign an interpretation to syntactically anomalous sentences when participants believed that these were generated by an LLM. Critically, the consistent P600 enhancement for LLM-attributed anomalies across both experiments suggests a unified account: participants may engage additional composition or integration efforts when assigning an interpretation to LLM-attributed sentences, regardless of anomaly type, as evidenced by the P600 effects observed in both studies.

The P600 effect to syntactic anomalies from LLMs was not predicted by perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans, which contrasts with our findings on the N400 and P600 effects to semantic anomalies from LLMs. This suggests that the “knowledge” in question is part of world knowledge or factual reliability, irrelevant to syntactic capabilities. Cognitive efforts in processing syntactic anomalies appear to be influenced by specific expectations about LLMs’ syntactic capabilities rather than their general knowledge. Further investigation is necessary to clarify this issue.

General discussion

The present study provides an interdisciplinary investigation integrating linguistic, psychological, and neuroscientific perspectives within HCI research. In two experiments, we investigated the brain responses when people encounter semantic and syntactic anomalies believed to be produced by an LLM versus by a human being. For semantic anomalies, we observed a smaller N400 effect and a larger P600 effect for LLM-attributed anomalies compared to human-attributed ones. This finding indicates that LLM-attributed semantic anomalies were better predictable and more tolerant, but still harder to compose or integrate. Moreover, we observed a larger P600 effect for LLM-attributed syntactically anomalous sentences than human-attributed ones. This indicates that LLM syntactic anomalies were worse predictable or harder to compose or integrate. The consistently enhanced P600 to LLM anomalies across two experiments suggests a unified interpretation: participants may engage additional composition or integration processes when assigning an interpretation to LLM-attributed sentences, regardless of anomaly type. Notably, individual differences in perceived LLM humanlike knowledge selectively modulated semantic but not syntactic processing. Participants with stronger beliefs in LLM humanlike capabilities showed larger N400 and smaller P600 effects for semantic anomalies, indicating they employed cognitive mechanisms more similar to human–human communication when processing LLM semantic anomalies. The absence of knowledge resemblance effects on syntactic processing indicates that perceived “knowledge” reflects world knowledge or factual reliability rather than syntactic capabilities, with syntactic processing influenced by distinct expectations about LLMs’ syntactic capabilities. These findings illuminate differences in the cognitive mechanisms deployed when comprehending LLM-attributed versus human-attributed language.

It should be noted that we observed only a nonsignificant trend toward a P600 effect when participants read syntactically anomalous sentences relative to well-form ones in the human condition, a finding that is in contrast with that in Qiu and Zhou (Reference Qiu and Zhou2012) and Hao et al. (Reference Hao, Duan, Zha and Xu2024) on the violation of the same syntactic agreement in Chinese. It is possible that as we explicitly emphasized to participants in the human condition that they were to read sentences previously produced by another person, participants might have expected “human errors” in these sentences, leading to increased tolerance with syntactic anomalies. Nevertheless, we must also acknowledge that participants might have developed strategies to predict upcoming syntactic violations through the initial temporal phrase. While our design included fillers with balanced initial temporal phrases to reduce this predictability, following a similar filler design to Liang et al. (Reference Liang, Chondrogianni and Chen2022) and representing an approach not employed in previous guo violation studies (e.g., Hao et al., Reference Hao, Duan, Zha and Xu2024; Qiu & Zhou, Reference Qiu and Zhou2012), we recognize that this may not have completely eliminated the potential for strategic processing. Although our filler distribution was not extensive, it provided more control over this predictability issue than previous studies and was sufficient for drawing our main conclusions. This represents a limitation inherent to this experimental paradigm that future research could address by incorporating additional balanced fillers or developing experimental designs.

Mental model construction of LLM properties during language processing

In general, the findings from the current study align with earlier research demonstrating that people take into account various attributes of their interlocutors (e.g., language background, gender, and socioeconomic status) during language comprehension and use such information to interpret speech and adjust expectations about the content and form of the interlocutor’s utterances (e.g., Cai, Reference Cai2022; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Gilbert, Davis, Gaskell, Farrar, Adler and Rodd2017, Reference Cai, Sun and Zhao2021; Corps et al., Reference Corps, Brooke and Pickering2022). For instance, people use their speaker’s accent to infer their dialectic background and understand cross-dialectally ambiguous words (Cai, Reference Cai2022; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Gilbert, Davis, Gaskell, Farrar, Adler and Rodd2017) and predict the likelihood of specific words or phrases based on the speaker’s language background (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Garcia, Potter, Melinger and Costa2016). People also consider the speaker’s gender, anticipating male and female speakers to discuss stereotypically masculine and feminine topics, respectively (Corps et al., Reference Corps, Brooke and Pickering2022). This gender-based expectation has been demonstrated in ERP studies, where comprehenders experience processing difficulties (reflected as enhanced N400 effects) when the message of a sentence does not align with the stereotypical expectations associated with the speaker’s age or gender (van Berkum et al., Reference Van Berkum, Van den Brink, Tesink, Kos and Hagoort2008; Wu, Duan, & Cai., Reference Wu, Duan and Cai2024; Wu & Cai, Reference Wu and Cai2025).

Our findings suggest that people can still apply interlocutor modeling when comprehending LLM-attributed language. That is, people seem to take into account an LLM’s factual unreliability and lack of genuine world knowledge, as well as its relatively high linguistic competence. This leads to the seemingly contradictory pattern: people are less “surprised” with semantic anomalies but are more “surprised” with syntactic anomalies in LLM language comprehension than human language comprehension. These findings are thus consistent with earlier findings that people treat AI systems with certain human traits. For instance, people perceive AI systems as having certain gender, age, and language competence. They assign gender to robots based on their appearance or voice (Eyssel & Kuchenbrandt, Reference Eyssel and Kuchenbrandt2012) and make assumptions about their knowledge based on stereotypical gender roles (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Kramer, Lim, Kuo, Lee and Kiesler2005; Powers & Kiesler, Reference Powers and Kiesler2006). People also interact differently with robots depending on their perceived age, being more likely to follow requests from baby-faced robots than adult-faced ones (Powers & Kiesler, Reference Powers and Kiesler2006) and perceiving child-voice robots as more acceptable for home companions and adult-voice robots as more suitable for educational tutors (Dou et al., Reference Dou, Wu, Lin, Gan and Tseng2021). Furthermore, people are sensitive to a computer’s language background and adjust their interaction accordingly. When collaborating with a computer speaking in an Irish or American accent, people tend to produce dialect-appropriate lexical expressions (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Doyle, Edwards and Clark2019). They also adapt their interaction based on the perceived language competence of a computer, aligning more with a computer than with a human (Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011; Shen & Wang, Reference Shen and Wang2023) and more with a basic computer than a more advanced one (Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Pickering, Pearson, McLean and Brown2011; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Hu, Branigan, Pickering and Nass2006). Our findings are thus in line with these previous findings, showing that people treat LLMs as having certain humanlike knowledge bases and adjust their language accordingly.

The conclusion that people construct a mental model of an LLM is further substantiated by the modulation of ERP components by the perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans. For semantic anomalies, attributing higher humanlike knowledge to LLMs predicted a larger N400 effect and a smaller P600 effect (Experiment 1). This indicates that as the perceived gap between human and LLM knowledge narrows, the cognitive mechanisms underlying semantic processing of LLM language is more humanlike. Nevertheless, no such modulation was observed for syntactic processing, revealing a dissociation that suggests people’s mental models distinguish between LLMs’ semantic and syntactic capabilities. In other words, people calibrate their expectations of LLMs across different linguistic domains. Further research is necessary to fully explore how domain-specific perceptions of LLM capabilities affect human–LLM interaction dynamics.

Theoretical insights into the divergent responses to anomalies in HCI

Overall, our results suggest that people do indeed treat LLMs similarly to their human peers by applying expectations, particularly in their language behaviors, in line with the Computers Are Social Actors paradigm (Nass & Moon, Reference Nass and Moon2000). However, these behaviors at times are not identical; people exhibit varying neural responses toward LLMs in certain contexts due to differing expectations. Our findings can also be interpreted within the framework of machine heuristics (Lee, Reference Lee2024). This framework posits that people attend to the source of information (machines vs. humans) primarily when linguistic output contradicts their expectations, and people’s prior beliefs about machines modulate their reaction to the unexpected performance of machines. Specifically, people with positive perceptions of machines may exhibit heightened negativity toward their underperformance due to unmet expectations, while those with negative beliefs may demonstrate greater tolerance for such shortcomings. Our results indicate that semantic anomalies elicited a reduced N400 response in LLM condition, consistent with the idea that people with negative beliefs about LLMs are more tolerant of their underperformance. As these negative beliefs decrease, tolerance also diminishes, as evidenced by a more pronounced N400 effect in LLM-attributed text among participants who held stronger convictions regarding the humanlike knowledge of LLMs. Additionally, the observation that syntactic anomalies perceived to be LLM-attributed elicited a larger P600, likely due to people’s belief in LLMs’ high syntactic capabilities, aligns with the account as well. Collectively, these findings highlight the significant moderating effect of task-relevant beliefs regarding LLMs’ specific properties on the neurocognitive processes involved in understanding LLM-attributed language.

Implications for advancing AI systems

Our findings have practical implications for designing systems that align with human cognitive needs. Our study demonstrates that core language comprehension processes—semantic and syntactic processing—can be influenced by people’s beliefs about LLMs. These beliefs may induce cognitive biases: people who believe that LLMs are flawless might overlook mistakes in their responses, while those who are skeptical may disengage or distrust the outputs, even if the information is accurate. Given the growing integration of LLMs into educational settings (Shahzad et al., Reference Shahzad, Mazhar, Tariq, Ahmad, Ouahada and Hamam2025), addressing cognitive biases and subconscious influences is urgent.

One approach is to improve explainable AI frameworks, which focus on making the decision-making processes of AI systems transparent and easily understandable for users (Shamsuddin et al., Reference Shamsuddin, Tabrizi and Gottimukkula2025). By designing systems that actively counteract subconscious biases through transparency, training, and human–AI collaboration, it is possible to foster environments where LLMs enhance rather than hinder the quality of interaction. This may also enhance user trust and engagement with AI technologies. Furthermore, understanding how cognitive biases vary across different contexts, such as education, healthcare, and entertainment, is an important direction for future research.

Conclusion

Our research reveals that people’s brains respond differently to LLM-attributed language compared to human-attributed language. In two experiments measuring brain activity, we found that people show more expectation for LLM-attributed semantic anomalies (a smaller N400 effect) yet still require more efforts to compose or integrate them (a larger P600 effect). In contrast, people show less expectation or have more integration difficulty when processing LLM syntactically anomalous sentences compared to human ones (a larger P600 effect). These findings suggest people develop expectations about LLMs, anticipating potential factual unreliability or semantic errors while expecting high syntactic capabilities. Notably, perceived humanlike knowledge of LLMs selectively modulated semantic processing: as perceived humanlike knowledge of LLMs increased, participants showed enhanced sensitivity to semantic anomalies from an LLM (larger N400) and reduced composition or integration efforts (smaller P600), resembling humanlike cognitive mechanisms. Nevertheless, perceived knowledge resemblance between LLMs and humans did not influence the syntactic processing of LLM language, indicating that people’s mental models distinguish between LLMs’ factual reliability and syntactic capabilities. As LLMs continue to evolve into more sophisticated communication partners, understanding these cognitive adaptations becomes increasingly important for designing effective human–AI interaction. Our study provides the first neuroscientific evidence that people’s perceptions of language source (human vs. LLMs) alter how their brains process information, highlighting the unique cognitive dynamics at play in the emerging landscape of human–AI communication.

Replication package

All experimental stimuli, data preprocessing scripts, analytic scripts, and raw data have been made publicly available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/kfmzu, with supplementary raw data available at https://osf.io/7y9ht and https://osf.io/jr2ys.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a General Research Fund (14600220) from University Grants Committee, Hong Kong.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.