1 Introduction

The Gieseker moduli space

![]() ${\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

of canonical models of surfaces of general type with

${\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

of canonical models of surfaces of general type with

![]() $K_X^2 =1$

and

$K_X^2 =1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

is a rational variety of dimension 28 and it was classically known that the surfaces it parametrises are hypersurfaces of degree 10 contained in the smooth locus of

$\chi (X) = 3$

is a rational variety of dimension 28 and it was classically known that the surfaces it parametrises are hypersurfaces of degree 10 contained in the smooth locus of

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

. More geometrically speaking, the bicanonical map realises these surfaces as double covers of the quadric cone in

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

. More geometrically speaking, the bicanonical map realises these surfaces as double covers of the quadric cone in

![]() ${\mathbb P}^3$

branched over the vertex and a sufficiently general quintic section.

${\mathbb P}^3$

branched over the vertex and a sufficiently general quintic section.

Nowadays, the Gieseker moduli space

![]() ${\mathfrak M}_{a,b}$

is known to admit a modular compactification

${\mathfrak M}_{a,b}$

is known to admit a modular compactification

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{a,b}$

, the moduli space of stable surfaces with

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{a,b}$

, the moduli space of stable surfaces with

![]() $K_X^2 =a$

and

$K_X^2 =a$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = b$

, sometimes called KSBA-moduli space after Kollár, Shepherd-Barron and Alexeev (compare [Reference KollárKol23]). For brevity we call the surfaces parametrised by

$\chi (X) = b$

, sometimes called KSBA-moduli space after Kollár, Shepherd-Barron and Alexeev (compare [Reference KollárKol23]). For brevity we call the surfaces parametrised by

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

stable I-surfaces (see Definition 2.2 for a precise definition).

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

stable I-surfaces (see Definition 2.2 for a precise definition).

Our detailed understanding of the Gieseker moduli space, or classical component, and the small values of the invariants make

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

into a fertile testing ground to explore stable surfaces and their moduli.

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

into a fertile testing ground to explore stable surfaces and their moduli.

So far a full picture seems out of reach, and the current approaches aim for classification under some extra conditions on the singularities. The first result in this direction was the extension of the classical description to Gorenstein stable I-surfaces [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR17], which was refined and explored further in [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR22] from a Hodge theoretic perspective. In [Reference Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeFPRR22, Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23] we explored surfaces with few T-singularities, finding several divisors and an additional component. Meanwhile in [Reference Gallardo, Pearlstein, Schaffler and ZhangGPSZ24] Gallardo, Pearlstein, Schaffler and Zhang found eight more divisors by considering the stable replacement of Gorenstein degenerations with an exceptional unimodal singularity; in [Reference Rollenske and TorresRT24] it was shown that there are not more divisors of this kind.

In the present paper we completely classify 2-Gorenstein stable I-surfaces, that is, those with

![]() $2K_X$

Cartier, dividing them into four types:

$2K_X$

Cartier, dividing them into four types:

Theorem 1.1. Let X be a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface. Then X is one of the following:

-

type A Semi-log-canonical hypersurfaces in

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

not passing through the point

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

not passing through the point

$(0:0:0:1)$

. This includes all Gorenstein stable I-surfaces and the divisor whose general element is a surface with one singularity of type

$(0:0:0:1)$

. This includes all Gorenstein stable I-surfaces and the divisor whose general element is a surface with one singularity of type

$\frac 14(1,1)$

.

$\frac 14(1,1)$

. -

type B These are reducible surfaces

$X = X_1 \cup X_2$

, where

$X = X_1 \cup X_2$

, where

$X_1$

is a singular Enriques surface and

$X_1$

is a singular Enriques surface and

$X_2$

is a singular K3 surface. They form a family of dimension

$X_2$

is a singular K3 surface. They form a family of dimension

$27$

in the closure of the Gieseker component, thus are smoothable, but no longer complete intersections.

$27$

in the closure of the Gieseker component, thus are smoothable, but no longer complete intersections. -

type DD These are reducible complete intersections of bidegree

$(2,10)$

in weighted projective space

$(2,10)$

in weighted projective space

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,2,5)$

and the bicanonical map realises them as double covers of the union of two planes. Each component is a singular K3 surface and they form a subset of codimension two in the closure of the Gieseker component.

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,2,5)$

and the bicanonical map realises them as double covers of the union of two planes. Each component is a singular K3 surface and they form a subset of codimension two in the closure of the Gieseker component. -

type DE These are reducible surfaces

$X = X_1 \cup X_2$

, where both

$X = X_1 \cup X_2$

, where both

$X_i$

are singular K3 surfaces of a special kind. They form a 30-dimensional family and none of them is smoothable, that is, they form a new irreducible component. Their canonical ring is quite complicated.

$X_i$

are singular K3 surfaces of a special kind. They form a 30-dimensional family and none of them is smoothable, that is, they form a new irreducible component. Their canonical ring is quite complicated.

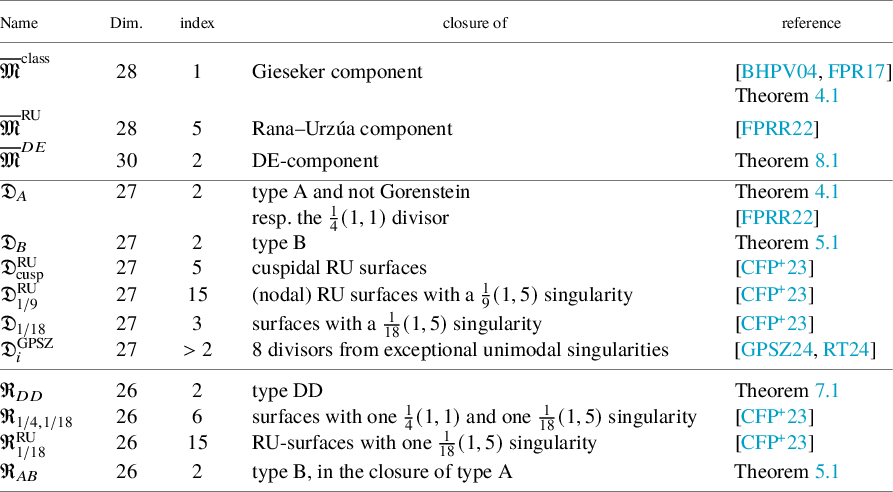

We give an overview of the known strata in

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

in Table 1, including dimension of the stratum, index of the general surface and a reference to precise information and proofs.

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

in Table 1, including dimension of the stratum, index of the general surface and a reference to precise information and proofs.

Table 1 Known irreducible strata in the moduli space

![]() $\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

of stable I-surfaces.

$\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

of stable I-surfaces.

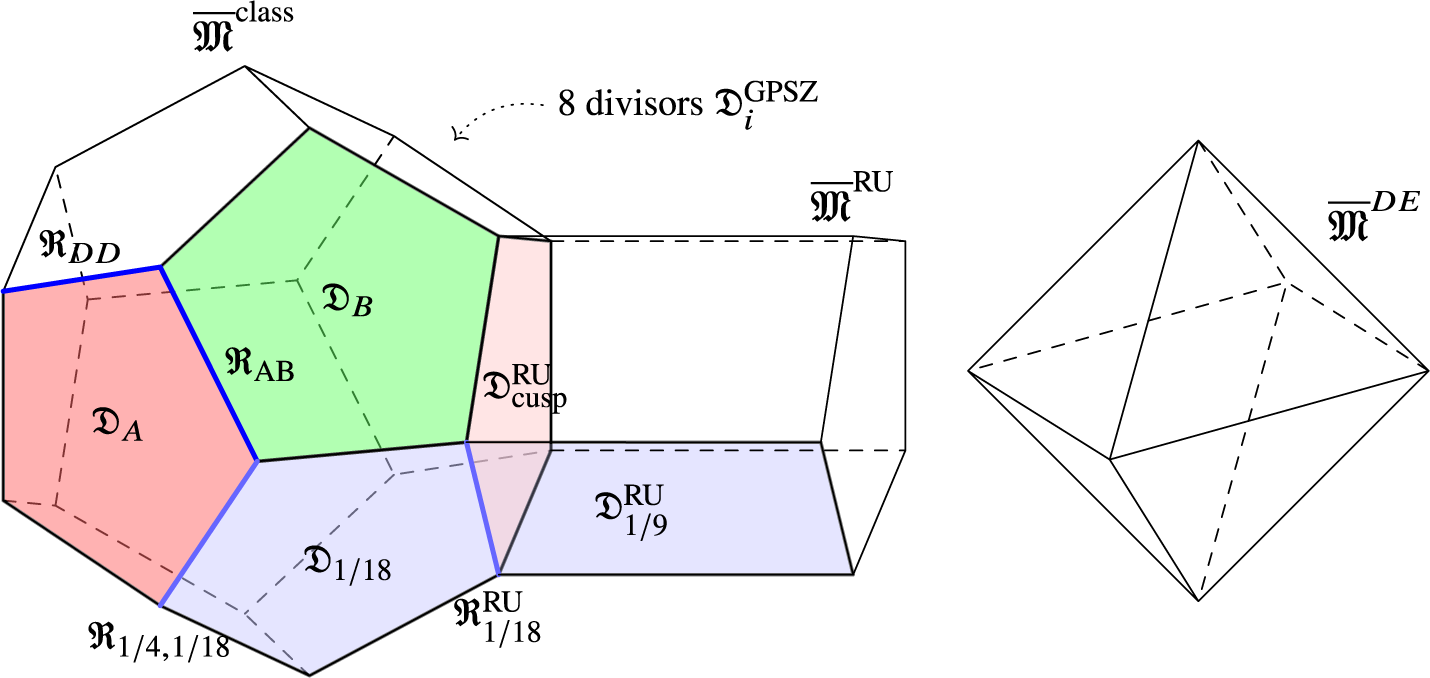

Our current knowledge of the locus of 2-Gorenstein stable I-surfaces in relation to the rest of

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

is shown in Figure 1. We have not studied possible degenerations of the surfaces in the previously unknown component

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

is shown in Figure 1. We have not studied possible degenerations of the surfaces in the previously unknown component

![]() ${\mathfrak M}^{DE}$

and we would not dare to speculate if it is a connected component without further evidence.

${\mathfrak M}^{DE}$

and we would not dare to speculate if it is a connected component without further evidence.

Figure 1 Known strata in

![]() $\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

(compare Table 1 for notation).

$\overline {{\mathfrak M}}_{1,3}$

(compare Table 1 for notation).

Outline of the paper and proof of Theorem 1.1

Let X be a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface as defined in Definition 2.2. Then we show in Proposition 3.3 that the general section of

![]() $\omega _X$

does not vanish on any component and thus defines a canonical curve C.

$\omega _X$

does not vanish on any component and thus defines a canonical curve C.

If C can be chosen reduced, then we use the hyperplane section principle [Reference ReidRei90] and our work on generalised Gorenstein spin structures on reduced curves of genus two [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23] (summarised in Theorem 3.8) to compute the canonical ring. This gives the surfaces of type A and type B, classified in Sections 4 and 5.

We were unable to argue along the same lines when the general canonical curve is nonreduced. However, in this case the surface is reducible and we succeed in giving a geometric description of the components and the possible glueings, resulting in two cases (Lemma 6.3).

Type DD is identified in Section 7 with a smoothable example already considered in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR17]. Type DE is shown to give a new irreducible component in Section 8; its canonical ring is computed a posteriori from the geometric description.

2 Notation and preliminary results

2.1 Set-up

We work with schemes of finite type over the complex numbers.

Given a sheaf

![]() ${\mathcal F}$

on a scheme X, we denote by

${\mathcal F}$

on a scheme X, we denote by ![]() its dual and by

its dual and by

![]() ${\mathcal F}^{[m]}$

the m-th reflexive power, i.e., the double dual of

${\mathcal F}^{[m]}$

the m-th reflexive power, i.e., the double dual of

![]() ${\mathcal F}^{\operatorname {\mathrm {\otimes }} m}$

.

${\mathcal F}^{\operatorname {\mathrm {\otimes }} m}$

.

A curve C is a Cohen–Macaulay projective scheme of pure dimension 1 (possibly nonreduced or reducible). It has a dualising sheaf

![]() $\omega _C$

and we denote by

$\omega _C$

and we denote by

![]() $p_a(C)$

the arithmetic genus of C, that is,

$p_a(C)$

the arithmetic genus of C, that is, ![]() . The curve C is Gorenstein if

. The curve C is Gorenstein if

![]() $\omega _C$

is invertible; if this is the case

$\omega _C$

is invertible; if this is the case

![]() $K_C$

denotes a canonical divisor such that

$K_C$

denotes a canonical divisor such that ![]() .

.

Our standard reference for stable surfaces is [Reference KollárKol13]. A stable surface X has semi-log-canonical singularities and ample canonical divisor. In particular, it is by definition Cohen–Macaulay and Gorenstein in codimension one, so the canonical sheaf

![]() $\omega _X$

exists and is reflexive. We call

$\omega _X$

exists and is reflexive. We call

![]() $X m$

-Gorenstein if the m-th reflexive power of the canonical sheaf

$X m$

-Gorenstein if the m-th reflexive power of the canonical sheaf

![]() $\omega _X^{[m]}$

is invertible. A canonical divisor is a Weil divisor

$\omega _X^{[m]}$

is invertible. A canonical divisor is a Weil divisor

![]() $K_X$

such that

$K_X$

such that ![]() . We use the notations

. We use the notations ![]() ,

,

![]() $p_g(X) = h^0(X, \omega _X)$

and

$p_g(X) = h^0(X, \omega _X)$

and ![]() .

.

If X is a non-normal stable surface, then we denote by

![]() $\pi \colon \bar X \to X$

the normalisation of X and by

$\pi \colon \bar X \to X$

the normalisation of X and by

![]() $D\subset X $

and

$D\subset X $

and

![]() $ \bar D\subset \bar X$

the curves defined by the conductor ideal

$ \bar D\subset \bar X$

the curves defined by the conductor ideal ![]() . The invariants are related by

. The invariants are related by

![]() $K_X^2 = (K_{\bar X}+\bar D)^2$

and

$K_X^2 = (K_{\bar X}+\bar D)^2$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = \chi ({\bar X})+\chi (D)-\chi ({\bar D})$

(see also [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR15, Prop. 3.3]).

$\chi (X) = \chi ({\bar X})+\chi (D)-\chi ({\bar D})$

(see also [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR15, Prop. 3.3]).

The map

![]() $\pi \colon \bar D \to D$

on the conductor divisors is generically a double cover and thus induces a rational involution on

$\pi \colon \bar D \to D$

on the conductor divisors is generically a double cover and thus induces a rational involution on

![]() $\bar D$

. Normalising the conductor loci we get an honest involution

$\bar D$

. Normalising the conductor loci we get an honest involution

![]() $\tau \colon \bar D^\nu \to \bar D^\nu $

such that

$\tau \colon \bar D^\nu \to \bar D^\nu $

such that

![]() $D^\nu = \bar D^\nu /\tau $

and such that the different

$D^\nu = \bar D^\nu /\tau $

and such that the different

![]() ${\mathsf {Diff}}_{\bar D^\nu }(0)$

is

${\mathsf {Diff}}_{\bar D^\nu }(0)$

is

![]() $\tau $

-invariant, which fits in the following pushout diagram:

$\tau $

-invariant, which fits in the following pushout diagram:

By Kollár’s glueing construction [Reference KollárKol13, Thm. 5.13], the surface X can be reconstructed uniquely from the triple

![]() $(\bar X, \bar D, \tau )$

.

$(\bar X, \bar D, \tau )$

.

2.2 I-surfaces

Our main interest stems from the Gieseker moduli space

![]() ${\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

and its closure in the moduli space of stable surfaces.

${\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

and its closure in the moduli space of stable surfaces.

For canonical or just Gorenstein stable surfaces X with fixed

![]() $K_X^2$

and

$K_X^2$

and

![]() $\chi (X)$

the Riemann–Roch formula and Kodaira vanishing determine all higher plurigenera as

$\chi (X)$

the Riemann–Roch formula and Kodaira vanishing determine all higher plurigenera as

![]() $P_m(X) = \chi (X) + \frac 12 m(m-1)K_X^2$

for

$P_m(X) = \chi (X) + \frac 12 m(m-1)K_X^2$

for

![]() $m\geq 2$

. Together with the geometric genus

$m\geq 2$

. Together with the geometric genus

![]() $p_g$

or equivalently the irregularity q this determines the Hilbert function of the canonical ring

$p_g$

or equivalently the irregularity q this determines the Hilbert function of the canonical ring

![]() $R(X, K_X)$

.

$R(X, K_X)$

.

By Noether’s inequality or [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR17] a Gorenstein stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2=1$

and

$K_X^2=1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

satisfies

$\chi (X) = 3$

satisfies

![]() $q(X) =0$

and thus has Hilbert seriesFootnote

1

$q(X) =0$

and thus has Hilbert seriesFootnote

1

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1-t^{10}}{(1-t)^2(1-t^2)(1-t^5)}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1-t^{10}}{(1-t)^2(1-t^2)(1-t^5)}. \end{align} $$

We will show below in Proposition 3.3 that this continues to hold if X is only

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein.

$2$

-Gorenstein.

If the Cartier index of X is larger, this is no longer true:

Example 2.1. Let

![]() $X=X_9\subset {\mathbb P}(1,1,3,3)$

a general hypersurface of degree

$X=X_9\subset {\mathbb P}(1,1,3,3)$

a general hypersurface of degree

![]() $9$

. Then X has three singularities of type

$9$

. Then X has three singularities of type

![]() $\frac 13 (1,1)$

and

$\frac 13 (1,1)$

and ![]() . Thus

. Thus

![]() $3K_X$

is Cartier and ample, so X is stable. The invariants are

$3K_X$

is Cartier and ample, so X is stable. The invariants are

![]() $K_X^2 = 1$

,

$K_X^2 = 1$

,

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

with

$\chi (X) = 3$

with

![]() $p_g(X) = 2$

. However,

$p_g(X) = 2$

. However, ![]() .

.

This example and more general instances of this phenomenon were considered in [Reference RollenskeRol23].

To exclude such pathological examples that are unrelated to the study of canonical surfaces, we specify the Hilbert series in our definition.

Definition 2.2. A stable I-surface is a stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2=1$

,

$K_X^2=1$

,

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

and Hilbert series of the canonical ring as in (2.2), in particular

$\chi (X) = 3$

and Hilbert series of the canonical ring as in (2.2), in particular

![]() $p_g(X) = 2$

and

$p_g(X) = 2$

and

![]() $q(X)=0$

.

$q(X)=0$

.

We denote the moduli space of stable I-surfaces by

![]() $\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

, the closure of the Gieseker component inside it by

$\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

, the closure of the Gieseker component inside it by

![]() $\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}^{\text {class}}$

.

$\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}^{\text {class}}$

.

3 Existence of canonical curves and consequences

If X is a stable surface, we say that X contains a canonical curve if there is a section

![]() $x_0\in H^0(X, \omega _X)$

which is nonzero at each generic point. In the irreducible case this just means that

$x_0\in H^0(X, \omega _X)$

which is nonzero at each generic point. In the irreducible case this just means that

![]() $x_0\neq 0$

, in general it can happen that a section vanishes identically on some but not every component.

$x_0\neq 0$

, in general it can happen that a section vanishes identically on some but not every component.

Example 3.1. Let C be a smooth plane quartic,

![]() $X_1=S^2C$

and

$X_1=S^2C$

and

![]() $D_1$

a coordinate curve. We have

$D_1$

a coordinate curve. We have

![]() $p_g(X_1) = q(X_1) = 3$

and

$p_g(X_1) = q(X_1) = 3$

and

![]() $K_{X_1}^2 = 6$

(see [Reference Hacon and PardiniHP02, Example 1]). Since

$K_{X_1}^2 = 6$

(see [Reference Hacon and PardiniHP02, Example 1]). Since

![]() $D_1$

is ample, the Riemann–Roch formula gives

$D_1$

is ample, the Riemann–Roch formula gives

![]() $h^0(K+D_1)=3=h^0(K)$

, so that

$h^0(K+D_1)=3=h^0(K)$

, so that

![]() $D_1$

is in the fixed part of

$D_1$

is in the fixed part of

![]() $|K+D_1|$

.

$|K+D_1|$

.

Now take

![]() $(X_2, D_2)=({\mathbb P}^2, C)$

and glue

$(X_2, D_2)=({\mathbb P}^2, C)$

and glue

![]() $D_1\cong C \cong D_2$

to get a stable surface X, which consists of the two components intersecting with normal crossings in the curve C. One can check that

$D_1\cong C \cong D_2$

to get a stable surface X, which consists of the two components intersecting with normal crossings in the curve C. One can check that

![]() $K_X^2 = 13$

,

$K_X^2 = 13$

,

![]() $p_g(X) = 3$

and

$p_g(X) = 3$

and

![]() $q(X) = 0$

.

$q(X) = 0$

.

By the above, all canonical sections vanish on the intersection curve, because their pullback to the normalisation vanishes on

![]() $D_1$

, thus they vanish identically on the component

$D_1$

, thus they vanish identically on the component

![]() $X_2$

and there is no canonical curve.

$X_2$

and there is no canonical curve.

3.1 Existence of canonical curves

In this section we prove the existence of canonical curves on any

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein stable I-surface. We start with slightly weaker hypotheses, which we then prove to imply that we have a stable I-surface.

$2$

-Gorenstein stable I-surface. We start with slightly weaker hypotheses, which we then prove to imply that we have a stable I-surface.

Lemma 3.2. Let X be a reducible 2-Gorenstein stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2 = 1$

and

$K_X^2 = 1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

. Then:

$\chi (X) = 3$

. Then:

-

1. the normalisation

$(\bar X,\bar D)$

of

$(\bar X,\bar D)$

of

$\bar X$

is equal to

$\bar X$

is equal to

$(\bar X_1, \bar D_1)\sqcup (\bar X_2, \bar D_2)$

, with

$(\bar X_1, \bar D_1)\sqcup (\bar X_2, \bar D_2)$

, with

$\bar X_i$

irreducible and

$\bar X_i$

irreducible and

$\bar D_i>0$

,

$\bar D_i>0$

,

$i=1,2$

;

$i=1,2$

; -

2. for

$i=1,2$

the divisor

$i=1,2$

the divisor

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i$

is 2-Cartier and ample with

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i$

is 2-Cartier and ample with

$(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i )^2=\frac 12$

.

$(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i )^2=\frac 12$

.

Proof. Let

![]() $\pi \colon \bar X = \bigsqcup _{i=1}^r\bar X_i \to X$

be the normalisation. Since

$\pi \colon \bar X = \bigsqcup _{i=1}^r\bar X_i \to X$

be the normalisation. Since

![]() $2K_X$

is an ample Cartier divisor, its pullback

$2K_X$

is an ample Cartier divisor, its pullback

![]() $\pi ^* 2K_X|_{\bar X_i} = 2( K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)$

is an ample Cartier divisor as well, and

$\pi ^* 2K_X|_{\bar X_i} = 2( K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)$

is an ample Cartier divisor as well, and

$$\begin{align*}2 = 2K_X^2 = \sum_{i=1}^r \left(2(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)\right)(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i) .\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}2 = 2K_X^2 = \sum_{i=1}^r \left(2(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)\right)(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i) .\end{align*}$$

Because the intersection of an ample Cartier divisor with a Weil divisor is a positive integer and because by assumption we have more than one component, we get

![]() $r = 2$

and

$r = 2$

and

![]() $(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)^2= \frac 12$

. The divisors

$(K_{\bar X_i} + \bar D_i)^2= \frac 12$

. The divisors

![]() $ \bar D_i$

cannot be zero, because they contain the preimage of the intersection of the two components, which is a curve because X is

$ \bar D_i$

cannot be zero, because they contain the preimage of the intersection of the two components, which is a curve because X is

![]() $S_2$

and connected.

$S_2$

and connected.

If X is a reducible 2-Gorenstein stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2 = 1$

and

$K_X^2 = 1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

and normalisation

$\chi (X) = 3$

and normalisation

![]() $(\bar X_1, \bar D_1)\sqcup (\bar X_2, \bar D_2)$

, we write

$(\bar X_1, \bar D_1)\sqcup (\bar X_2, \bar D_2)$

, we write

![]() $\bar D_i= \bar Z_i+ \bar \Gamma _i$

, where

$\bar D_i= \bar Z_i+ \bar \Gamma _i$

, where

![]() $\bar \Gamma _1$

is glued to

$\bar \Gamma _1$

is glued to

![]() $ \bar \Gamma _2$

by

$ \bar \Gamma _2$

by

![]() $\pi $

, while

$\pi $

, while

![]() $ \bar Z_i$

is glued to itself for

$ \bar Z_i$

is glued to itself for

![]() $i=1,2$

. Note that

$i=1,2$

. Note that

![]() $ \bar \Gamma _i>0$

since X is connected and

$ \bar \Gamma _i>0$

since X is connected and

![]() $S_2$

, while

$S_2$

, while

![]() $\bar Z_i$

may be zero.

$\bar Z_i$

may be zero.

With this notation in place we can state the main result of this section:

Proposition 3.3. Let X be a 2-Gorenstein stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2 = 1$

and

$K_X^2 = 1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

. Then:

$\chi (X) = 3$

. Then:

-

1. the zero locus of a general section of

$H^0(K_X)$

is one-dimensional;

$H^0(K_X)$

is one-dimensional; -

2.

$q(X)=0$

and X is a stable I-surface;

$q(X)=0$

and X is a stable I-surface; -

3. all canonical curves are nonreduced if and only if

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar Z_i=0$

for

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar Z_i=0$

for

$i=1,2$

. In this case, every canonical curve is supported on

$i=1,2$

. In this case, every canonical curve is supported on

$X_1\cap X_2$

.

$X_1\cap X_2$

.

Before proving Proposition 3.3 we give some auxiliary results.

Lemma 3.4. Let Y be a smooth projective surface and let M be a nef line bundle. If

![]() $M^2=2$

, then

$M^2=2$

, then

![]() $h^0(M)\le 4$

.

$h^0(M)\le 4$

.

Proof. We can of course assume that

![]() $r:=h^0(M)-1\ge 1$

, otherwise the statement is empty. Write

$r:=h^0(M)-1\ge 1$

, otherwise the statement is empty. Write

![]() $|M|=Z+|D|$

, where Z is the fixed part and D the moving part, denote by

$|M|=Z+|D|$

, where Z is the fixed part and D the moving part, denote by

![]() $h\colon X\to {\mathbb P}^r$

the map defined by

$h\colon X\to {\mathbb P}^r$

the map defined by

![]() $|D|$

and let d be the degree of the image

$|D|$

and let d be the degree of the image

![]() $\Sigma $

of h. Assume first that

$\Sigma $

of h. Assume first that

![]() $\Sigma $

is a surface: then since M and D are nef we have

$\Sigma $

is a surface: then since M and D are nef we have

![]() $2=M^2\ge MD\ge D^2\ge d\ge r-1$

, hence

$2=M^2\ge MD\ge D^2\ge d\ge r-1$

, hence

![]() $r\leq 3$

. If instead

$r\leq 3$

. If instead

![]() $\Sigma $

is a curve, then D is numerically equivalent to

$\Sigma $

is a curve, then D is numerically equivalent to

![]() $dG$

, where G is irreducible and

$dG$

, where G is irreducible and

![]() $2=M^2\ge MD=dMG\ge d\ge r$

, so

$2=M^2\ge MD=dMG\ge d\ge r$

, so

![]() $r\le 2$

in this case.

$r\le 2$

in this case.

If

![]() $X=X_1\cup X_2$

is a reducible stable 2-Gorenstein stable surface with

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is a reducible stable 2-Gorenstein stable surface with

![]() $K_X^2 = 1$

and

$K_X^2 = 1$

and

![]() $\chi (X) = 3$

, then we denote by

$\chi (X) = 3$

, then we denote by

the pullback map.

Lemma 3.5. In the above set-up and notation, assume that

![]() $\rho _1$

is not injective: then

$\rho _1$

is not injective: then

![]() $\dim \ker \rho _1=1$

and

$\dim \ker \rho _1=1$

and

![]() $K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2=0$

.

$K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2=0$

.

Proof. Set

![]() $L_i:=2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

for

$L_i:=2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

for

![]() $i=1,2$

. Recall that by assumption

$i=1,2$

. Recall that by assumption

![]() $L_i$

is an ample line bundle with

$L_i$

is an ample line bundle with

![]() $L_i ^2=2$

. Consider

$L_i ^2=2$

. Consider

![]() $0\ne \sigma \in \ker \rho _1$

: since

$0\ne \sigma \in \ker \rho _1$

: since

![]() $\rho $

is injective,

$\rho $

is injective,

![]() $\rho _2(\sigma )$

is a nonzero section of

$\rho _2(\sigma )$

is a nonzero section of

![]() $K_{\bar X_2}+\bar D_2$

that vanishes on

$K_{\bar X_2}+\bar D_2$

that vanishes on

![]() $\bar \Gamma _2$

, hence

$\bar \Gamma _2$

, hence

![]() $K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2\ge 0$

. Since

$K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2\ge 0$

. Since

![]() $L_2$

is ample,

$L_2$

is ample,

![]() $1=L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+\bar D_2)=L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2)+L _2 \bar \Gamma _2$

and

$1=L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+\bar D_2)=L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2)+L _2 \bar \Gamma _2$

and

![]() $\bar \Gamma _2>0$

give

$\bar \Gamma _2>0$

give

![]() $L_2 \bar \Gamma _2=1$

,

$L_2 \bar \Gamma _2=1$

,

![]() $L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2)=0$

, therefore

$L_2(K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2)=0$

, therefore

![]() $K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2=0$

and

$K_{\bar X_2}+ \bar Z_2=0$

and

![]() $ \bar \Gamma _2$

is irreducible. Note that

$ \bar \Gamma _2$

is irreducible. Note that

![]() $\bar \Gamma _2$

is the divisor of

$\bar \Gamma _2$

is the divisor of

![]() $\rho _2(\sigma )$

. If

$\rho _2(\sigma )$

. If

![]() $0\ne \tau $

is another element of

$0\ne \tau $

is another element of

![]() $\ker \rho _1$

, then the divisor of

$\ker \rho _1$

, then the divisor of

![]() $\rho _2(\tau )$

is also equal to

$\rho _2(\tau )$

is also equal to

![]() $\bar \Gamma _2$

and therefore,

$\bar \Gamma _2$

and therefore,

![]() $\rho _2(\tau )$

and

$\rho _2(\tau )$

and

![]() $\rho _2(\sigma )$

are linearly dependent. Since

$\rho _2(\sigma )$

are linearly dependent. Since

![]() $\rho $

is injective, it follows that

$\rho $

is injective, it follows that

![]() $\ker \rho _1$

has dimension 1.

$\ker \rho _1$

has dimension 1.

Proof of Proposition 3.3.

-

1. Assume for contradiction that all sections of

$K_X$

have a two-dimensional zero locus. Then

$K_X$

have a two-dimensional zero locus. Then

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and we may assume that all sections of

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and we may assume that all sections of

$K_X$

vanish on

$K_X$

vanish on

$X_1$

. By Lemma 3.5 we get

$X_1$

. By Lemma 3.5 we get

$p_g(X)\le 1$

, contradicting

$p_g(X)\le 1$

, contradicting

$\chi (X)=3$

.

$\chi (X)=3$

. -

2. Assume for contradiction

$q(X)>0$

, namely

$q(X)>0$

, namely

$p_g(X)\ge 3$

. If X is irreducible, then

$p_g(X)\ge 3$

. If X is irreducible, then

$4=K^2_X+\chi (X)=h^0(2K_X)$

by [Reference Liu and RollenskeLR14, Prop. 16], because

$4=K^2_X+\chi (X)=h^0(2K_X)$

by [Reference Liu and RollenskeLR14, Prop. 16], because

$2K_X$

is Cartier. On the other hand the Hopf lemma (see [Reference Arbarello, Cornalba, Griffiths and HarrisACGH85, p. 108]) gives

$2K_X$

is Cartier. On the other hand the Hopf lemma (see [Reference Arbarello, Cornalba, Griffiths and HarrisACGH85, p. 108]) gives

$h^0(2K_X)\ge 2p_g(X)-1\ge 5$

, a contradiction. So

$h^0(2K_X)\ge 2p_g(X)-1\ge 5$

, a contradiction. So

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible.

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible.If

$\rho _i$

is injective, then

$\rho _i$

is injective, then

$h^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)\ge 3$

. Then the Hopf lemma gives

$h^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)\ge 3$

. Then the Hopf lemma gives

$h^0(2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i))\ge 2h^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)-1\ge 5$

. Pulling back

$h^0(2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i))\ge 2h^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)-1\ge 5$

. Pulling back

$2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

to a line bundle M on a desingularisation Y of

$2(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

to a line bundle M on a desingularisation Y of

$\bar X_i$

we obtain a contradiction to Lemma 3.4. So

$\bar X_i$

we obtain a contradiction to Lemma 3.4. So

$\rho _1$

and

$\rho _1$

and

$\rho _2$

are not injective. Identifying

$\rho _2$

are not injective. Identifying

$H^0(K_X)$

with its image via

$H^0(K_X)$

with its image via

$\rho $

, we can find three independent sections of the form:

$\rho $

, we can find three independent sections of the form:

$(\sigma _1,0)$

,

$(\sigma _1,0)$

,

$(0,\tau _1)$

,

$(0,\tau _1)$

,

$(\sigma _2,\tau _2)$

. Note that

$(\sigma _2,\tau _2)$

. Note that

$\sigma _1$

and

$\sigma _1$

and

$\sigma _2$

are independent because

$\sigma _2$

are independent because

$\ker \rho _2$

is one-dimensional by Lemma 3.5 and by the same argument

$\ker \rho _2$

is one-dimensional by Lemma 3.5 and by the same argument

$\tau _1$

and

$\tau _1$

and

$\tau _2$

are also independent. Now the following correspond to linearly independent sections of

$\tau _2$

are also independent. Now the following correspond to linearly independent sections of

$2K_X$

: contradicting again

$2K_X$

: contradicting again $$ \begin{align*}(\sigma_1^2,0), \ (\sigma_1\sigma_2,0),\ (0,\tau_1^2),\ (0,\tau_1\tau_2), \ (\sigma_2^2, \tau_2^2),\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}(\sigma_1^2,0), \ (\sigma_1\sigma_2,0),\ (0,\tau_1^2),\ (0,\tau_1\tau_2), \ (\sigma_2^2, \tau_2^2),\end{align*} $$

$h^0(2K_X)=4$

. We have proved that

$h^0(2K_X)=4$

. We have proved that

$q(X) = 0$

.

$q(X) = 0$

.

It remains to control the plurigenera of X. Since even multiples of the canonical divisor are Cartier, the Riemann–Roch formula applies, so we only need to control the odd plurigenera.

Let C be a canonical curve defined by a section

$x_0$

. As explained in Proposition 3.6 below the reflexive restriction sequence (3.2) defines a torsion free sheaf of rank one

$x_0$

. As explained in Proposition 3.6 below the reflexive restriction sequence (3.2) defines a torsion free sheaf of rank one

${\mathcal L} = \omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

on C with

${\mathcal L} = \omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

on C with  . By definition we have

. By definition we have

$\deg {\mathcal L} = 1$

, see [Reference HartshorneHar86, Reference Catanese, Franciosi, Hulek and ReidCFHR99]. We now twist (3.2) with the line bundle

$\deg {\mathcal L} = 1$

, see [Reference HartshorneHar86, Reference Catanese, Franciosi, Hulek and ReidCFHR99]. We now twist (3.2) with the line bundle

$\omega _X^{[{2m}]}$

with

$\omega _X^{[{2m}]}$

with

$m\geq 1$

and compute using generalised Kodaira vanishing and the Riemann–Roch formula on singular curves This is the correct plurigenus for a stable I-surface.

$m\geq 1$

and compute using generalised Kodaira vanishing and the Riemann–Roch formula on singular curves This is the correct plurigenus for a stable I-surface. $$ \begin{align*} P_{2m+1} (X)& = \chi(\omega_X^{[{2m+1}]} ) = \chi(\omega_X^{[{2m}]}) + \chi({\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_X^{[2m]} |_C) \\ & = \chi (X) + m(2m-1) + \chi(C) + 2m+1 = \chi (X) + m(2m+1). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} P_{2m+1} (X)& = \chi(\omega_X^{[{2m+1}]} ) = \chi(\omega_X^{[{2m}]}) + \chi({\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_X^{[2m]} |_C) \\ & = \chi (X) + m(2m-1) + \chi(C) + 2m+1 = \chi (X) + m(2m+1). \end{align*} $$

-

3. If X is irreducible, then pulling back the canonical system to a desingularisation Y of X and considering its moving part we see that the general canonical curve C has at least a reduced component. Since

$2K_XC=2$

and

$2K_XC=2$

and

$2K_X$

is an ample line bundle, it follows that C is reduced. Therefore

$2K_X$

is an ample line bundle, it follows that C is reduced. Therefore

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

. Consider the pullback map

$X=X_1\cup X_2$

. Consider the pullback map

$\rho =\rho _1\oplus \rho _2$

: if, say,

$\rho =\rho _1\oplus \rho _2$

: if, say,

$\rho _1$

is injective, then a similar argument shows that the restriction to

$\rho _1$

is injective, then a similar argument shows that the restriction to

$X_1$

of a general

$X_1$

of a general

$C\in |K_X|$

is reduced and not contained in

$C\in |K_X|$

is reduced and not contained in

$\bar \Gamma _1$

, hence C is reduced. So it follows that

$\bar \Gamma _1$

, hence C is reduced. So it follows that

$\rho _1$

and

$\rho _1$

and

$\rho _2$

are not injective and, by Lemma 3.5

$\rho _2$

are not injective and, by Lemma 3.5

$K_{\bar X_i}+ \bar Z_i=0$

,

$K_{\bar X_i}+ \bar Z_i=0$

,

$i=1,2$

, and all canonical curves are supported on

$i=1,2$

, and all canonical curves are supported on

$X_1\cap X_2$

.

$X_1\cap X_2$

.Conversely, assume that

$X= X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and

$X= X_1\cup X_2$

is reducible and

$K_{\bar X_i}+ \bar Z_i=0$

. Then

$K_{\bar X_i}+ \bar Z_i=0$

. Then

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i= \bar \Gamma _i>0$

for

$K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i= \bar \Gamma _i>0$

for

$i=1,2$

. Take

$i=1,2$

. Take

$\sigma _i\in H^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

a nonzero section that vanishes on

$\sigma _i\in H^0(K_{\bar X_i}+\bar D_i)$

a nonzero section that vanishes on

$\bar \Gamma _i$

: then

$\bar \Gamma _i$

: then

$(\sigma _1,0)$

and

$(\sigma _1,0)$

and

$(0,\sigma _2)$

correspond to independent canonical sections. Since

$(0,\sigma _2)$

correspond to independent canonical sections. Since

$p_g(X)=2$

by 2., these sections generate

$p_g(X)=2$

by 2., these sections generate

$H^0(K_X)$

and therefore every canonical curve is supported on

$H^0(K_X)$

and therefore every canonical curve is supported on

$X_1\cap X_2$

and is not reduced.

$X_1\cap X_2$

and is not reduced.

3.2 Restriction of the canonical ring to a canonical curve

In order to apply Reid’s hyperplane section principle, we need to describe the restriction of the canonical ring to a canonical curve carefully. In the end, this will be useful only if the general canonical curve is reduced.

Let X be a stable I-surface and fix C a canonical curve on X defined by

![]() $x_0 \in H^0(X, \omega _X)$

. Noting that

$x_0 \in H^0(X, \omega _X)$

. Noting that ![]() is the canonical bundle we get three exact sequences

is the canonical bundle we get three exact sequences

Indeed, (3.3) arises by applying ![]() to the restriction sequence (3.1) to get the exact sequence

to the restriction sequence (3.1) to get the exact sequence ![]() . The third sheaf in this sequence may be identified with

. The third sheaf in this sequence may be identified with

![]() $\omega _C$

by definition of the dualising sheaf (see [Reference ReidRei94, Theorem 2.12]).

$\omega _C$

by definition of the dualising sheaf (see [Reference ReidRei94, Theorem 2.12]).

Proposition 3.6. Let X be a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface with canonical curve C defined by

![]() ${x_0 \in H^0(X, \omega _X)}$

. Let

${x_0 \in H^0(X, \omega _X)}$

. Let

![]() ${\mathcal L}$

be the sheaf on C defined by (3.2). Then

${\mathcal L}$

be the sheaf on C defined by (3.2). Then

-

1. The curve C is a Gorenstein curve of arithmetic genus

$2$

with ample canonical bundle

$2$

with ample canonical bundle

$\omega _C$

and

$\omega _C$

and  .

. -

2. The sheaf

${\mathcal L}\cong \omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

is a torsion-free sheaf with

${\mathcal L}\cong \omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

is a torsion-free sheaf with

$\chi ({\mathcal L}) = 0$

,

$\chi ({\mathcal L}) = 0$

,

$h^0({\mathcal L}) =1$

and the map

$h^0({\mathcal L}) =1$

and the map

$\mu $

defined by the diagram is an isomorphism in codimension zero.

$\mu $

defined by the diagram is an isomorphism in codimension zero.

-

3. The multiplication on global sections induced by

$\mu $

, namely makes the natural restriction map

$\mu $

, namely makes the natural restriction map $$\begin{align*}H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} m}) \times H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} n}) \to H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} {\mathcal L} \operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_{C}^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}}(m+n)}) \to H^0( \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}}(m+n+1)}), \end{align*}$$

into a surjective ring homomorphism with kernel generated by

$$\begin{align*}H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} m}) \times H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} n}) \to H^0( {\mathcal L}\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} {\mathcal L} \operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}} \omega_{C}^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}}(m+n)}) \to H^0( \omega_C^{\operatorname{\mathrm{\otimes}}(m+n+1)}), \end{align*}$$

into a surjective ring homomorphism with kernel generated by $$\begin{align*}\phi\colon R(X, K_X) \twoheadrightarrow \bigoplus_{n \geq 0} \left(H^0(C, \omega_C^{\otimes n}) \oplus H^0(C, {\mathcal L}\otimes \omega_C^{\otimes n})\right)=: R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\})\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\phi\colon R(X, K_X) \twoheadrightarrow \bigoplus_{n \geq 0} \left(H^0(C, \omega_C^{\otimes n}) \oplus H^0(C, {\mathcal L}\otimes \omega_C^{\otimes n})\right)=: R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\})\end{align*}$$

$x_0$

.

$x_0$

.

In the notation of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23] the pair

![]() $({\mathcal L}, \mu )$

is a ggs (generalised Gorenstein spin) structure on C and

$({\mathcal L}, \mu )$

is a ggs (generalised Gorenstein spin) structure on C and

![]() $R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

is the associated half-canonical ring.

$R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

is the associated half-canonical ring.

Proof. Several times we make use of the long exact cohomology sequences of (3.1), (3.2), (3.3), possibly twisted with

![]() $\omega _X^{[{2k}]}$

, the fact that

$\omega _X^{[{2k}]}$

, the fact that

![]() $q(X) = 0 $

by Proposition 3.3 and generalised Kodaira vanishing [Reference Liu and RollenskeLR14, Prop. 21])

$q(X) = 0 $

by Proposition 3.3 and generalised Kodaira vanishing [Reference Liu and RollenskeLR14, Prop. 21])

To prove the first point, note that by assumption

![]() $\omega _X^{[{2}]}$

is a line bundle and from (3.3) we get

$\omega _X^{[{2}]}$

is a line bundle and from (3.3) we get

-

•

$\omega _C$

is the restriction of an ample line bundle, thus ample and C is Gorenstein,

$\omega _C$

is the restriction of an ample line bundle, thus ample and C is Gorenstein, -

•

by the long exact cohomology sequence and Kodaira vanishing and duality on C,

by the long exact cohomology sequence and Kodaira vanishing and duality on C, -

•

$\deg \omega _C = C\cdot 2K_X = 2$

and thus the arithmetic genus

$\deg \omega _C = C\cdot 2K_X = 2$

and thus the arithmetic genus

$p_a(C) = 2$

.

$p_a(C) = 2$

.

We now prove the second point. By the depth-Lemma [Reference EisenbudEis95, Cor. 18.6] and the fact that

![]() $\omega _X^{[{m}]}$

is

$\omega _X^{[{m}]}$

is

![]() $S_2$

for every m, the sheaf

$S_2$

for every m, the sheaf

![]() ${\mathcal L}$

is the quotient of

${\mathcal L}$

is the quotient of ![]() by the torsion submodule,

by the torsion submodule,

![]() ${\mathcal L}$

is torsion-free on C and coincides with

${\mathcal L}$

is torsion-free on C and coincides with

![]() $\omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

(see [Reference HartshorneHar94, Proposition 1.6]). The values

$\omega _X|_C^{[{1}]}$

(see [Reference HartshorneHar94, Proposition 1.6]). The values

![]() $\chi ({\mathcal L}) = 0$

,

$\chi ({\mathcal L}) = 0$

,

![]() $h^0({\mathcal L}) =1$

follow from (3.2).

$h^0({\mathcal L}) =1$

follow from (3.2).

The map

![]() $\mu $

exists because every torsion sheaf maps to zero in the line bundle

$\mu $

exists because every torsion sheaf maps to zero in the line bundle

![]() $\omega _C$

. Outside the codimension two subset of X where

$\omega _C$

. Outside the codimension two subset of X where

![]() $\omega _X$

is not locally free, that is, outside a finite number of points, the map

$\omega _X$

is not locally free, that is, outside a finite number of points, the map

![]() $\mu $

is an isomorphism.

$\mu $

is an isomorphism.

For the last point, the existence of the ring structure on

![]() $R(C, \{{\mathcal L}, \omega _C\}) $

and the ring homomorphism

$R(C, \{{\mathcal L}, \omega _C\}) $

and the ring homomorphism

![]() $\phi $

is clear by construction. The surjectivity follows from twists of (3.2) in odd degrees and twists of (3.3) in even degrees.

$\phi $

is clear by construction. The surjectivity follows from twists of (3.2) in odd degrees and twists of (3.3) in even degrees.

Remark 3.7. It is only slightly more tedious to work out the nature of the restriction of a section ring of any

![]() ${\mathbb Q}$

-Cartier divisor to a curve in a similar fashion, but we don’t need this here.

${\mathbb Q}$

-Cartier divisor to a curve in a similar fashion, but we don’t need this here.

In the case where the canonical curve is reduced, we can use the results of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23] to describe the restricted canonical ring

![]() $R(C, \{{\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

.

$R(C, \{{\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

.

Theorem 3.8. Let

![]() $(C, {\mathcal L}, \mu )$

be as in Proposition 3.6, that is, C is a Gorenstein curve of arithmetic genus two with ample canonical bundle and

$(C, {\mathcal L}, \mu )$

be as in Proposition 3.6, that is, C is a Gorenstein curve of arithmetic genus two with ample canonical bundle and

![]() $({\mathcal L}, \mu )$

is a ggs structure on C with

$({\mathcal L}, \mu )$

is a ggs structure on C with

![]() $h^0(C, {\mathcal L}) = 1$

. If C is reduced, then the following two cases are possible

$h^0(C, {\mathcal L}) = 1$

. If C is reduced, then the following two cases are possible

-

type A The curve C is a flat double cover of

${\mathbb P}^1$

, so in particular it is either irreducible or the union of two smooth rational curves. The half-canonical ring is where

${\mathbb P}^1$

, so in particular it is either irreducible or the union of two smooth rational curves. The half-canonical ring is where $$\begin{align*}R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\}) = {\mathbb C}[x,y,z]/( z^2 - f_{10}(x,y)),\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\}) = {\mathbb C}[x,y,z]/( z^2 - f_{10}(x,y)),\end{align*}$$

$\deg (x,y,z) =(1,2,5)$

and

$\deg (x,y,z) =(1,2,5)$

and

$f_{10}\neq 0$

is weighted homogeneous of degree

$f_{10}\neq 0$

is weighted homogeneous of degree

$10$

.

$10$

.

-

type B The curve C is the union of two irreducible curves

$C_i$

with

$C_i$

with

$p_a(C_i)=1$

,

$p_a(C_i)=1$

,

$i=1,2$

, that meet transversely at a single point p that is smooth for both. The half-canonical ring is with

$i=1,2$

, that meet transversely at a single point p that is smooth for both. The half-canonical ring is with $$\begin{align*}R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\}) = {\mathbb C}[x,y,w,v,z,u] / I, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega_C\}) = {\mathbb C}[x,y,w,v,z,u] / I, \end{align*}$$

$\deg (x,y,w,v,z,u) =(1,2,3,4,5,6)$

and the ideal I is generated by the following equations where

$\deg (x,y,w,v,z,u) =(1,2,3,4,5,6)$

and the ideal I is generated by the following equations where $$\begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{rk}} \begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}\leq 1, \begin{array}{rcl} z^2 & = & yg_8(y,v) \\ zu & = & wg_8(y,v) \\ u^2 & = & vg_8(y,v) + x^4h_8(x,v) \end{array} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{rk}} \begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}\leq 1, \begin{array}{rcl} z^2 & = & yg_8(y,v) \\ zu & = & wg_8(y,v) \\ u^2 & = & vg_8(y,v) + x^4h_8(x,v) \end{array} \end{align*}$$

$g_8$

and

$g_8$

and

$h_8$

are weighted homogeneous of degree 8 and

$h_8$

are weighted homogeneous of degree 8 and

$v^2$

appears in

$v^2$

appears in

$g_8$

with nonzero coefficient.

$g_8$

with nonzero coefficient.

Proof. The distinction and description of the cases comes from Proposition 3.3 and Corollary 3.9 in [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23], while the half-canonical rings are the cases

![]() $A(1)$

and

$A(1)$

and

![]() $B(1)$

of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23, Theorem 5.2].

$B(1)$

of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeCFPR23, Theorem 5.2].

4 Surfaces with reduced canonical curve of type A

It turns out that these are well known to us.

Theorem 4.1. Let X be a

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein I-surface containing a reduced canonical curve C of type A and let

$2$

-Gorenstein I-surface containing a reduced canonical curve C of type A and let

$$\begin{align*}{\mathfrak D}_A = \overline{ \left\{ [X]\in \overline{\mathfrak M}_{1,3} \left| \, \begin{array}[c]{l} X\ \textit{is 2-Gorenstein but not Gorenstein with reduced}\\ \hbox{canonical curve of type A} \end{array} \right.\right\} }\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{\mathfrak D}_A = \overline{ \left\{ [X]\in \overline{\mathfrak M}_{1,3} \left| \, \begin{array}[c]{l} X\ \textit{is 2-Gorenstein but not Gorenstein with reduced}\\ \hbox{canonical curve of type A} \end{array} \right.\right\} }\end{align*}$$

where the closure is taken in

![]() $\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

.

$\overline {\mathfrak M}_{1,3}$

.

-

1. The surface X is canonically embedded as a hypersurface of degree

$10$

in

$10$

in

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

not passing through

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

not passing through

$(0:0:0:1)$

and X is

$(0:0:0:1)$

and X is

${\mathbb Q}$

-Gorenstein smoothable. It is Gorenstein if and only if X does not contain the point

${\mathbb Q}$

-Gorenstein smoothable. It is Gorenstein if and only if X does not contain the point

$(0:0:1:0)$

.

$(0:0:1:0)$

.Conversely, any such hypersurface with slc singularities is a stable I-surface.

-

2. The set

${\mathfrak D}_A$

is an irreducible divisor in the closure of the Gieseker component. It coincides with the closure of the divisor of surfaces with one singularity of type

${\mathfrak D}_A$

is an irreducible divisor in the closure of the Gieseker component. It coincides with the closure of the divisor of surfaces with one singularity of type

$\frac {1}{4}(1,1)$

considered in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeFPRR22, Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23].

$\frac {1}{4}(1,1)$

considered in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeFPRR22, Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23].

Proof.

-

1. The description as a hypersurface follows directly via the hyperplane section principle [Reference ReidRei90] from the description of the ring

$R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

given in Theorem 3.8, type A. The ‘converse’ statement follows by using adjunction for hypersurfaces in

$R(C, \{ {\mathcal L}, \omega _C\})$

given in Theorem 3.8, type A. The ‘converse’ statement follows by using adjunction for hypersurfaces in

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

, while the criterion for X being Gorenstein was proved in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR17, Theorem 3.3, Proposition 4.1] (see also [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23, Remark 3.2]).

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,5)$

, while the criterion for X being Gorenstein was proved in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini and RollenskeFPR17, Theorem 3.3, Proposition 4.1] (see also [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23, Remark 3.2]). -

2. The set

${\mathfrak D}_A$

is the closure of the image of an open subset of the linear system of hypersurfaces of degree

${\mathfrak D}_A$

is the closure of the image of an open subset of the linear system of hypersurfaces of degree

$10$

containing the point

$10$

containing the point

$(0:0:1:0)$

by 1. and as such it is an irreducible divisor. Its general element has a unique singular point of type

$(0:0:1:0)$

by 1. and as such it is an irreducible divisor. Its general element has a unique singular point of type

$\frac 14(1,1)$

by the discussion in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeFPRR22, Section 3.A].

$\frac 14(1,1)$

by the discussion in [Reference Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeFPRR22, Section 3.A].

Example 4.2. If we take X to be the hypersurface in

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1_{x_1},1_{x_2},2_y,5_z)$

defined by the equation

${\mathbb P}(1_{x_1},1_{x_2},2_y,5_z)$

defined by the equation

![]() ${z^2-x_1x_2f_4(x_1,x_2,y)^2=0}$

, with

${z^2-x_1x_2f_4(x_1,x_2,y)^2=0}$

, with

![]() $f_4$

a general polynomial of degree 4, then X is irreducible with normalisation

$f_4$

a general polynomial of degree 4, then X is irreducible with normalisation

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,4)$

, and the canonical system has only one base point, occurring above the vertex of the quadric cone. Nevertheless, all the canonical curves are reducible.

${\mathbb P}(1,1,4)$

, and the canonical system has only one base point, occurring above the vertex of the quadric cone. Nevertheless, all the canonical curves are reducible.

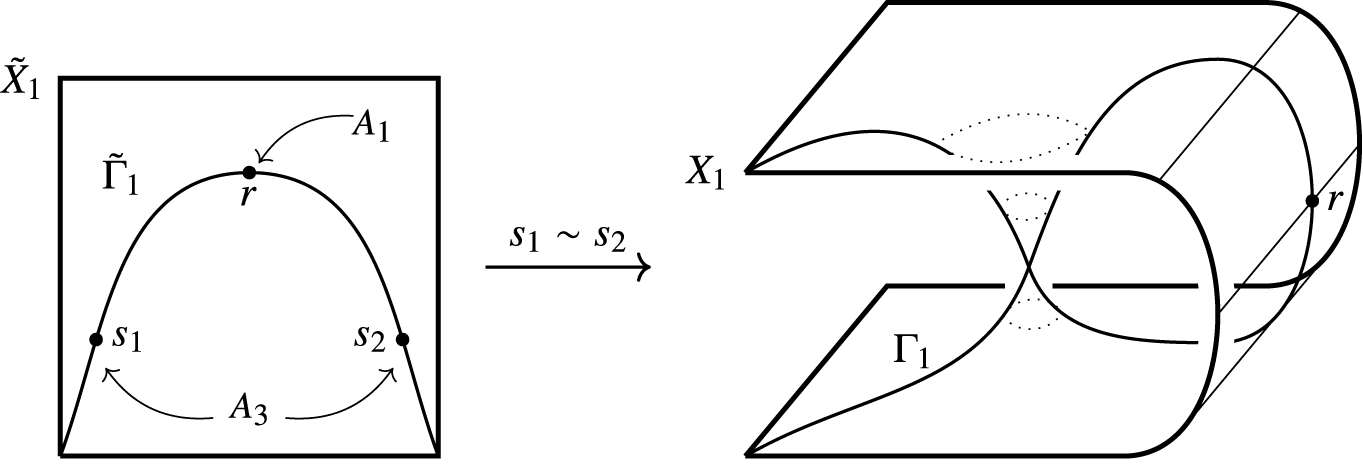

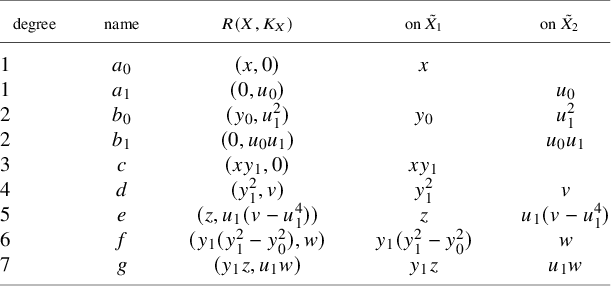

5 Surfaces with reduced canonical curve of type B

In this section we describe 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B (in the notation of Theorem 3.8).

Theorem 5.1. Let X be a

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein stable I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then the canonical ring of X is as in Proposition 5.6 and if X is general, it is glued from an Enriques surface and a K3 surface as in Proposition 5.4.

$2$

-Gorenstein stable I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then the canonical ring of X is as in Proposition 5.6 and if X is general, it is glued from an Enriques surface and a K3 surface as in Proposition 5.4.

The closure of the set of such surfaces,

is an irreducible divisor in the closure of the Gieseker moduli space.

The intersection of divisors

![]() ${\mathfrak D}_A \cap {\mathfrak D}_B$

contains the irreducible codimension two subset

${\mathfrak D}_A \cap {\mathfrak D}_B$

contains the irreducible codimension two subset

We will start with the geometric description, via which the surfaces were initially found, and then prove Theorem 5.1 in Proposition 5.6, Corollary 5.7 and Proposition 5.8.

5.1 A geometric construction

We will start with a geometric description of 2-Gorenstein stable surfaces with reduced canonical curve of type B. Let us fix some notation: we denote by

![]() ${\mathbb F}_n$

the Hirzebruch surface with negative section

${\mathbb F}_n$

the Hirzebruch surface with negative section

![]() $s_\infty $

of square

$s_\infty $

of square

![]() $s_\infty ^2 = -n$

. We call a section

$s_\infty ^2 = -n$

. We call a section

![]() $s_0$

disjoint from

$s_0$

disjoint from

![]() $s_\infty $

a positive section.

$s_\infty $

a positive section.

Construction 5.2. Let

![]() $Y_1$

be an Enriques surface containing a half-pencil

$Y_1$

be an Enriques surface containing a half-pencil

![]() $E_1$

, that is, an elliptic curve

$E_1$

, that is, an elliptic curve

![]() $E_1$

such that

$E_1$

such that

![]() $|2E_1|$

is an elliptic pencil. Assume further that

$|2E_1|$

is an elliptic pencil. Assume further that

![]() $Y_1$

contains a

$Y_1$

contains a

![]() $(-2)$

-curve which is a bisection

$(-2)$

-curve which is a bisection

![]() $\Lambda _1$

of

$\Lambda _1$

of

![]() $|2E_1|$

.

$|2E_1|$

.

Contracting

![]() $\Lambda _1$

to an

$\Lambda _1$

to an

![]() $A_1$

point p, we get a singular Enriques surface

$A_1$

point p, we get a singular Enriques surface

![]() $X_1$

containing an elliptic curve

$X_1$

containing an elliptic curve

![]() $E_1$

through the point p with

$E_1$

through the point p with

![]() $E_1^2 = \frac 12$

.

$E_1^2 = \frac 12$

.

The K3 cover

![]() $T_1 \to Y_1$

is an elliptic K3 surface and contains two disjoint

$T_1 \to Y_1$

is an elliptic K3 surface and contains two disjoint

![]() $(-2)$

-curves

$(-2)$

-curves

![]() $G_1, G_2$

, which realise

$G_1, G_2$

, which realise

![]() $T_1$

as a double cover of

$T_1$

as a double cover of

![]() ${\mathbb F}_2$

branched over a (symmetric) divisor

${\mathbb F}_2$

branched over a (symmetric) divisor

![]() $B_1\in |4s_0|$

and one can construct explicit examples in this way.

$B_1\in |4s_0|$

and one can construct explicit examples in this way.

Such Enriques surfaces have been studied in [Reference Cossec and DolgachevCD89, Ch.4, §7] where it is shown that the so-called superelliptic linear system

![]() $|4E_1+2\Lambda _1|$

on

$|4E_1+2\Lambda _1|$

on

![]() $Y_1$

realises

$Y_1$

realises

![]() $X_1$

as the double cover of a degenerate symmetric del Pezzo surface

$X_1$

as the double cover of a degenerate symmetric del Pezzo surface

![]() $W_1'$

of degree 4 in

$W_1'$

of degree 4 in

![]() ${\mathbb P}^4$

.

${\mathbb P}^4$

.

One can check that

![]() $W_1'\cong W_1 = \{ w^2-yv =0 \} \subset {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},2_y, 3_w,4_v)$

fitting in the following commutative diagram:

$W_1'\cong W_1 = \{ w^2-yv =0 \} \subset {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},2_y, 3_w,4_v)$

fitting in the following commutative diagram:

Finally, we count the number of moduli of this construction. The K3 cover

![]() $S_1$

of

$S_1$

of

![]() $X_1$

is a hypersurface of degree

$X_1$

is a hypersurface of degree

![]() $8$

in

$8$

in

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1_{a_0},1_{a_1},2_b,4_c)$

with equation

${\mathbb P}(1_{a_0},1_{a_1},2_b,4_c)$

with equation

![]() $c^2=g_8(a_0,a_1^2,a_1b,b^2)$

. In addition,

$c^2=g_8(a_0,a_1^2,a_1b,b^2)$

. In addition,

![]() $g_8$

is invariant under the involution

$g_8$

is invariant under the involution

![]() $\iota $

of

$\iota $

of

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,4)$

defined by

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,4)$

defined by

![]() $(a_0,a_1,b,c)\mapsto (a_0,-a_1,-b,-c)$

(cf. [Reference Barth, Hulek, Peters and de VenBHPV04, Thm. VIII.18.2]). An explicit computation shows that

$(a_0,a_1,b,c)\mapsto (a_0,-a_1,-b,-c)$

(cf. [Reference Barth, Hulek, Peters and de VenBHPV04, Thm. VIII.18.2]). An explicit computation shows that

![]() $g_8$

varies in a linear system of dimension 12. Since the subgroup of automorphisms of

$g_8$

varies in a linear system of dimension 12. Since the subgroup of automorphisms of

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,4)$

that commute with

${\mathbb P}(1,1,2,4)$

that commute with

![]() $\iota $

has dimension 3, we get

$\iota $

has dimension 3, we get

![]() $9$

parameters for

$9$

parameters for

![]() $(X_1, E_1)$

.

$(X_1, E_1)$

.

Construction 5.3. Let

![]() $B_2 \subset {\mathbb F}_4$

be a general divisor in

$B_2 \subset {\mathbb F}_4$

be a general divisor in

![]() $|s_\infty + 3s_0| = s_\infty + |3s_0|$

and let

$|s_\infty + 3s_0| = s_\infty + |3s_0|$

and let

![]() $Y_2$

be the double cover branched over

$Y_2$

be the double cover branched over

![]() $B_2$

. By the Hurwitz formula

$B_2$

. By the Hurwitz formula

![]() $Y_2$

is a smooth K3 surface with an elliptic fibration induced by the fibration on

$Y_2$

is a smooth K3 surface with an elliptic fibration induced by the fibration on

![]() ${\mathbb F}_4$

.

${\mathbb F}_4$

.

The preimage of

![]() $s_\infty $

is a

$s_\infty $

is a

![]() $(-2)$

-curve

$(-2)$

-curve

![]() $\Lambda _2\subset Y_2$

and contracting it we get a singular K3 surface

$\Lambda _2\subset Y_2$

and contracting it we get a singular K3 surface

![]() $X_2$

with one

$X_2$

with one

![]() $A_1$

singularity at a point p. It can be viewed as a double cover of

$A_1$

singularity at a point p. It can be viewed as a double cover of

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,4)$

or as a hypersurface of degree

${\mathbb P}(1,1,4)$

or as a hypersurface of degree

![]() $12$

in

$12$

in

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1,1,4,6)$

, resulting in a diagram

${\mathbb P}(1,1,4,6)$

, resulting in a diagram

The image of any fibre of the elliptic fibration is a curve

![]() $E_2$

of arithmetic genus one in

$E_2$

of arithmetic genus one in

![]() $X_2$

containing the point p and satisfying

$X_2$

containing the point p and satisfying

![]() $E_2^2 = \frac 12$

. Note that a general

$E_2^2 = \frac 12$

. Note that a general

![]() $Y_2$

is not isotrivial, so every isomorphism class of elliptic curves occurs a finite number of times as a fibre.

$Y_2$

is not isotrivial, so every isomorphism class of elliptic curves occurs a finite number of times as a fibre.

To count parameters for

![]() $Y_2$

, we observe that the linear system

$Y_2$

, we observe that the linear system

![]() $|\sigma _{\infty }+3\sigma _0|$

on

$|\sigma _{\infty }+3\sigma _0|$

on

![]() ${\mathbb F}_4$

has dimension 27, while the automorphism group of

${\mathbb F}_4$

has dimension 27, while the automorphism group of

![]() ${\mathbb F}_4$

has dimension

${\mathbb F}_4$

has dimension

![]() $9$

, so we get

$9$

, so we get

![]() $18$

parameters.

$18$

parameters.

Proposition 5.4. Let

![]() $(X_1, E_1)$

be as in Construction 5.2 and

$(X_1, E_1)$

be as in Construction 5.2 and

![]() $(X_2, E_2)$

be as in Construction 5.3 with

$(X_2, E_2)$

be as in Construction 5.3 with

![]() $E_1\cong E_2$

a smooth elliptic curve. Then the two pairs can be glued to a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface

$E_1\cong E_2$

a smooth elliptic curve. Then the two pairs can be glued to a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface

![]() $X = X_1\cup _{E_1\cong E_2}X_2$

such that the general canonical curve is of type B.

$X = X_1\cup _{E_1\cong E_2}X_2$

such that the general canonical curve is of type B.

The construction depends on

![]() $27$

parameters.

$27$

parameters.

Proof. Note that

![]() $(X_i, E_i)$

are stable pairs with volume

$(X_i, E_i)$

are stable pairs with volume

![]() $\frac 12$

. By Kollár’s glueing construction [Reference KollárKol13, Thm. 5.13], the two components can be glued to a stable surface if the glueing isomorphism

$\frac 12$

. By Kollár’s glueing construction [Reference KollárKol13, Thm. 5.13], the two components can be glued to a stable surface if the glueing isomorphism

![]() $E_1\cong E_2$

preserves the different, that is, if it preserves the point p.

$E_1\cong E_2$

preserves the different, that is, if it preserves the point p.

It is easy to check from the classification of slc singularities that X is

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein. The two components of a general canonical curve C are defined by sections in

$2$

-Gorenstein. The two components of a general canonical curve C are defined by sections in

![]() $H^0(X_i, K_{X_i}+E_i)$

and are thus two curves of arithmetic genus one, intersecting in the point p.

$H^0(X_i, K_{X_i}+E_i)$

and are thus two curves of arithmetic genus one, intersecting in the point p.

The pair

![]() $(X_1, E_1)$

depends on

$(X_1, E_1)$

depends on

![]() $9$

parameters (see Construction 5.2) and

$9$

parameters (see Construction 5.2) and

![]() $X_2$

depends on

$X_2$

depends on

![]() $18$

parameters (see Construction 5.3), which leaves us with finitely many choices of a fibre

$18$

parameters (see Construction 5.3), which leaves us with finitely many choices of a fibre

![]() $E_2$

of the elliptic fibration on

$E_2$

of the elliptic fibration on

![]() $Y_2$

which is isomorphic to

$Y_2$

which is isomorphic to

![]() $E_1$

.

$E_1$

.

Remark 5.5. The canonical system of a surface as in Proposition 5.4 has a fixed part: on the Enriques surface

![]() $X_1$

there is a unique section of

$X_1$

there is a unique section of

![]() $K_{X_1}+E_1$

, corresponding to the other half-pencil in the elliptic fibration on

$K_{X_1}+E_1$

, corresponding to the other half-pencil in the elliptic fibration on

![]() $Y_1$

.

$Y_1$

.

5.2 Classification via the canonical ring

To completely classify 2-Gorenstein stable I-surfaces with reduced canonical curve of type B, we again rely on a description of the canonical ring and show that this coincides with the geometric description given in Section 5.1.

Proposition 5.6. Let X be a

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then the surface X is canonically embedded in

$2$

-Gorenstein I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then the surface X is canonically embedded in

![]() ${\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},1_x,2_y,3_w,4_v,5_z,6_u)$

with weighted homogeneous equations:

${\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},1_x,2_y,3_w,4_v,5_z,6_u)$

with weighted homogeneous equations:

$$ \begin{align} \bigwedge^2\begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}=0,\ \ \begin{array}{rcl} z^2&=&y\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)\\ zu&=&w\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)\\ u^2&=&v\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)+x^2\tilde k_{10}(x_0,x,v) \end{array} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \bigwedge^2\begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}=0,\ \ \begin{array}{rcl} z^2&=&y\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)\\ zu&=&w\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)\\ u^2&=&v\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)+x^2\tilde k_{10}(x_0,x,v) \end{array} \end{align} $$

where

![]() $v^2$

appears in

$v^2$

appears in

![]() $\tilde g_8$

with nonzero coefficient, which we fix to be

$\tilde g_8$

with nonzero coefficient, which we fix to be

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

Conversely, if X is defined by general equations of this form, then ![]() and X is a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface.

and X is a 2-Gorenstein stable I-surface.

Proof. The equations from Theorem 3.8 which define the canonical curve of type B, can be expressed in the following format:

$$\begin{align*}\bigwedge^2\begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}=0,\ \ \begin{array}{rcl} z^2&=&yg_8(y,v)\\zu&=&wg_8(y,v)\\u^2&=&vg_8(y,v)+x^4h_8(x,v) \end{array} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\bigwedge^2\begin{pmatrix}0&y&w&z\\x&w&v&u\end{pmatrix}=0,\ \ \begin{array}{rcl} z^2&=&yg_8(y,v)\\zu&=&wg_8(y,v)\\u^2&=&vg_8(y,v)+x^4h_8(x,v) \end{array} \end{align*}$$

This format is useful for studying the equations of the surface X which contains C as canonical hyperplane section.

We reconstruct X from C by applying the hyperplane section principle [Reference ReidRei90]. The ideal of relations has 9 generators and 16 syzygies, so it is possible to work out the equations of X by hand après Reid [Reference ReidRei90]. We also used the computer package of Ilten [Reference IltenIlt12] which in turn follows an algorithm laid out by Stevens [Reference StevensSte01]. We highlight the two most important features of the result.

The

![]() $2\times 4$

matrix for C is weighted homogeneous with weights

$2\times 4$

matrix for C is weighted homogeneous with weights

![]() $\left (\begin {smallmatrix}0&2&3&5\\1&3&4&6\end {smallmatrix}\right )$

and generic entries, except that w appears twice. Thus (after relabelling the entries) the only possible change to the matrix for X would be to one of the w-entries. In fact, it is impossible to change one w-entry without violating some of the 16 syzygies yoking the relations together, hence the matrix for X is unchanged.

$\left (\begin {smallmatrix}0&2&3&5\\1&3&4&6\end {smallmatrix}\right )$

and generic entries, except that w appears twice. Thus (after relabelling the entries) the only possible change to the matrix for X would be to one of the w-entries. In fact, it is impossible to change one w-entry without violating some of the 16 syzygies yoking the relations together, hence the matrix for X is unchanged.

The last relation output by the algorithm has the unsatisfactory form

where

![]() $\tilde h_8(x_0,x,v)|_{x_0=0}=h_8$

and

$\tilde h_8(x_0,x,v)|_{x_0=0}=h_8$

and

![]() $a_8,b_8,c_8$

are general forms of degree

$a_8,b_8,c_8$

are general forms of degree

![]() $8$

in

$8$

in

![]() $(x_0,x,v)$

. We write

$(x_0,x,v)$

. We write

![]() ${\tilde k_{10}=x^2\tilde h_8+x_0x a_8+x_0^2b_8}$

and absorb those terms of

${\tilde k_{10}=x^2\tilde h_8+x_0x a_8+x_0^2b_8}$

and absorb those terms of

![]() $c_8$

that are divisible by x or v into

$c_8$

that are divisible by x or v into

![]() $x^2\tilde k_{10}$

or

$x^2\tilde k_{10}$

or

![]() $v\tilde g_8$

respectively. This leaves

$v\tilde g_8$

respectively. This leaves

where c is now a constant. Using the coordinate transformations

![]() $x\mapsto x+\alpha x_0$

and

$x\mapsto x+\alpha x_0$

and

![]() $v\mapsto v+\beta x_0^4$

for appropriate choices of parameters

$v\mapsto v+\beta x_0^4$

for appropriate choices of parameters

![]() $\alpha $

,

$\alpha $

,

![]() $\beta $

, we eliminate c to obtain the stated equation. Moreover, the new coordinates do not affect the original choice of curve section C. Note that

$\beta $

, we eliminate c to obtain the stated equation. Moreover, the new coordinates do not affect the original choice of curve section C. Note that

![]() $\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)|_{x_0=0}=g_8(y,v)$

because after utilising the relation

$\tilde g_8(x_0,y,w,v)|_{x_0=0}=g_8(y,v)$

because after utilising the relation

![]() $w^2=yv$

, all monomials of

$w^2=yv$

, all monomials of

![]() $\tilde g_8$

involving w also involve

$\tilde g_8$

involving w also involve

![]() $x_0$

, for degree reasons.

$x_0$

, for degree reasons.

To find

![]() $\omega _X$

, we follow the same procedure as in the proof of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23, Cor. 3.12]. That is, we use computer algebra to get the minimal free resolution of

$\omega _X$

, we follow the same procedure as in the proof of [Reference Coughlan, Franciosi, Pardini, Rana and RollenskeCFP+23, Cor. 3.12]. That is, we use computer algebra to get the minimal free resolution of ![]() as an

as an ![]() -module. This is a self-dual complex of length four because the homogeneous coordinate ring of X is Gorenstein, and the last term of the complex is

-module. This is a self-dual complex of length four because the homogeneous coordinate ring of X is Gorenstein, and the last term of the complex is ![]() . Since the complex is self-dual, and

. Since the complex is self-dual, and ![]() , when we apply

, when we apply

![]() $\mathcal {H}om(-,\omega _{\mathbb P})$

, we can read off

$\mathcal {H}om(-,\omega _{\mathbb P})$

, we can read off ![]() .

.

To show that

![]() $\omega _X^{[2]}$

is invertible, it suffices to show that X does not intersect the loci

$\omega _X^{[2]}$

is invertible, it suffices to show that X does not intersect the loci

![]() ${\mathbb P}(3_w,6_u)$

,

${\mathbb P}(3_w,6_u)$

,

![]() ${\mathbb P}(4_v)$

,

${\mathbb P}(4_v)$

,

![]() ${\mathbb P}(5_z)$

where

${\mathbb P}(5_z)$

where ![]() is not invertible. This can be deduced from the equations (5.2): the monomials

is not invertible. This can be deduced from the equations (5.2): the monomials

![]() $v^3$

and

$v^3$

and

![]() $z^2$

appear in some equation, so X is disjoint from

$z^2$

appear in some equation, so X is disjoint from

![]() ${\mathbb P}(4)$

and from

${\mathbb P}(4)$

and from

![]() ${\mathbb P}(5)$

, and since

${\mathbb P}(5)$

, and since

![]() $w^2$

and

$w^2$

and

![]() $u^2$

appear in separate equations, it follows that X is disjoint from

$u^2$

appear in separate equations, it follows that X is disjoint from

![]() ${\mathbb P}(3,6)$

as well. Hence

${\mathbb P}(3,6)$

as well. Hence ![]() is invertible and X is 2-Gorenstein.

is invertible and X is 2-Gorenstein.

Corollary 5.7. Let X be a

![]() $2$

-Gorenstein I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then

$2$

-Gorenstein I-surface with reduced canonical curve of type B. Then

![]() ${X = X_1\cup X_2}$

is reducible and fits in a diagram

${X = X_1\cup X_2}$

is reducible and fits in a diagram

where

![]() $W_1 = \{ w^2-yv =0 \} \subset {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},2_y,3_w,4_v)$

and

$W_1 = \{ w^2-yv =0 \} \subset {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0},2_y,3_w,4_v)$

and

![]() $W_2 = {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0}, 1_x,4_v) $

.

$W_2 = {\mathbb P}(1_{x_0}, 1_x,4_v) $

.

-

1. The intersection

is a curve of arithmetic genus one embedded via the section ring of

, where

, where

$p = (0:1_v: 1_u)$

.

$p = (0:1_v: 1_u)$

.

If the defining equations are sufficiently general, then:

-

2. The pair

$(X_1,E)$

is a singular Enriques surface as described in Construction 5.2.

$(X_1,E)$

is a singular Enriques surface as described in Construction 5.2. -

3. The pair

$(X_2, E)$

is a singular K3 surface as described in Construction 5.3.

$(X_2, E)$

is a singular K3 surface as described in Construction 5.3.

In particular, X arises as in Proposition 5.4.

Proof. The defining ideal of X contains the three reducible equations

![]() $xy=xw=xz=0$

cutting out the two (weighted) linear subspaces such that X is contained in their union. Since X cannot be contained in one of them,

$xy=xw=xz=0$

cutting out the two (weighted) linear subspaces such that X is contained in their union. Since X cannot be contained in one of them,

![]() $X = X_1 \cup X_2$

has two irreducible components; it cannot have more by Lemma 3.2.

$X = X_1 \cup X_2$

has two irreducible components; it cannot have more by Lemma 3.2.

The linear projection corresponds to the subring generated by

![]() $x_0, x, y, w, v$

and the three equations on the right hand side of (5.2) show that the map is of degree two on both components of X.

$x_0, x, y, w, v$

and the three equations on the right hand side of (5.2) show that the map is of degree two on both components of X.

We translate the equations into the geometric descriptions.

-