1. Introduction

The combinatorial analysis of homotopy types dates back to the 1940s with Whitehead’s simple homotopy theory [Reference Whitehead35–Reference Whitehead38]. In an effort to describe homotopy equivalences through rigid transformations of combinatorial structures, Whitehead introduced collapses and expansions for finite simplicial complexes. These moves were inspired by Tietze transformations for group presentations. While Tietze’s theory provides a complete set of transformations between equivalent presentations, Whitehead’s simple homotopy theory is more restrictive and fails to capture all homotopy deformations. Nevertheless, it remains a powerful combinatorial framework, influencing classical problems [Reference Akbulut and Kirby1, Reference Milnor25]; such as Zeeman’s conjecture [Reference Zeeman39]; the Andrews–Curtis conjecture [Reference Andrews and Curtis2, Reference Hog-Angeloni and Metzler20]; and the Poincaré conjecture [Reference Poincaré30, Reference Zeeman40]; as well as modern computational approaches to analysing complexes and data [Reference Bauer and Edelsbrunner4, Reference Benedetti, Lai, Lofano and Lutz5, Reference Robins, Wood and Sheppard31].

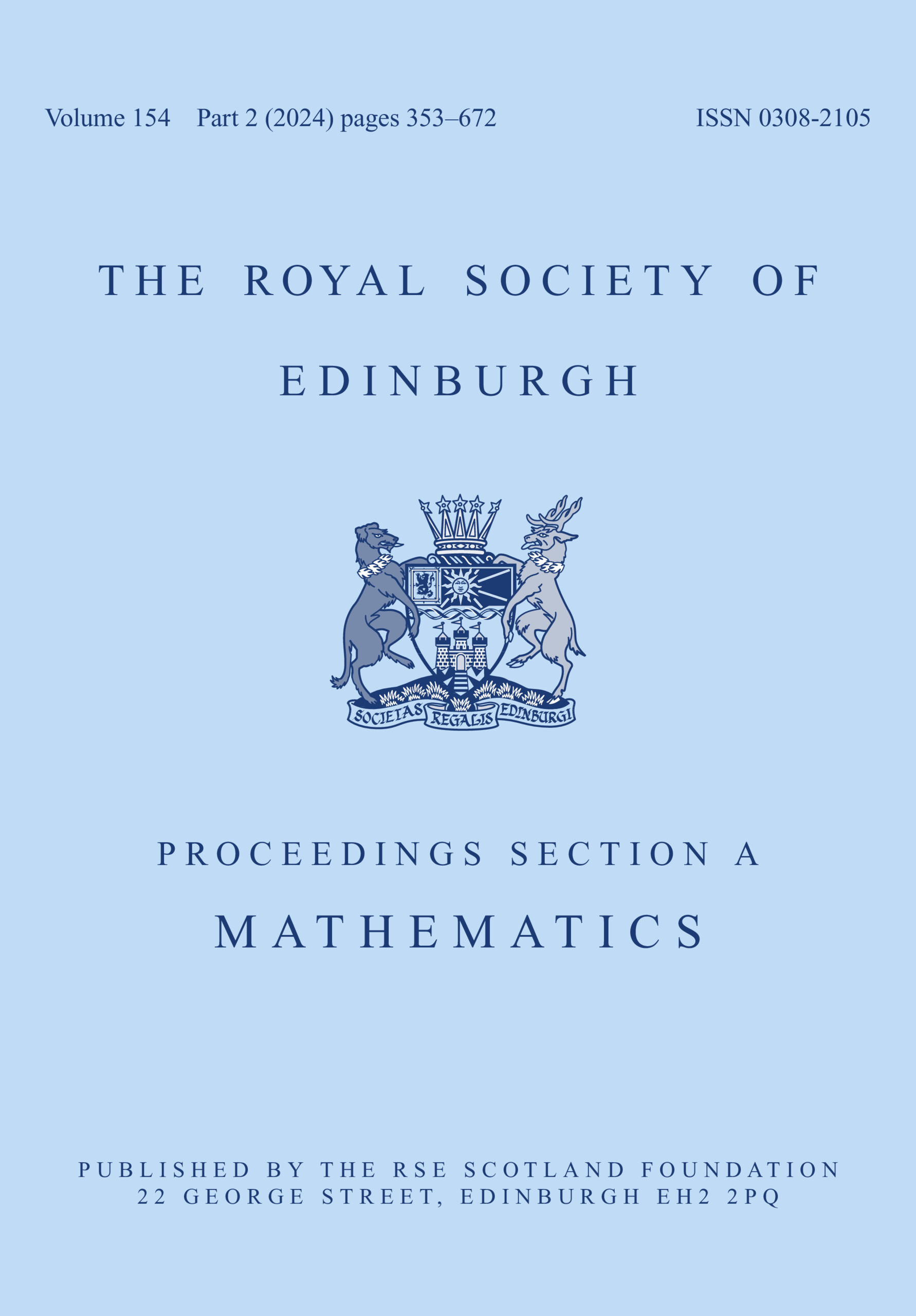

Whitehead’s elementary deformations are called collapses (and their reverse moves, expansions), which rely on the concept of a free face. If ![]() $\tau$ is the unique simplex of a simplicial complex

$\tau$ is the unique simplex of a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ properly containing

$K$ properly containing ![]() $\sigma$, then both

$\sigma$, then both ![]() $\sigma$ and

$\sigma$ and ![]() $\tau$ can be removed from

$\tau$ can be removed from ![]() $K$ while preserving its homotopy type and simplicial structure (see Figure 1, left). However, many simplicial complexes lack free faces (e.g., triangulations of closed manifolds). A more general concept is that of an internal free face, leading to an internal collapse [Reference Fernández16, Reference Kaczyński, Mrozek and Ślusarek21, Reference Kozlov23]. Here,

$K$ while preserving its homotopy type and simplicial structure (see Figure 1, left). However, many simplicial complexes lack free faces (e.g., triangulations of closed manifolds). A more general concept is that of an internal free face, leading to an internal collapse [Reference Fernández16, Reference Kaczyński, Mrozek and Ślusarek21, Reference Kozlov23]. Here, ![]() $\sigma$ becomes a free face of

$\sigma$ becomes a free face of ![]() $\tau$ in a subcomplex

$\tau$ in a subcomplex ![]() $L \subseteq K$. To preserve the homotopy type of

$L \subseteq K$. To preserve the homotopy type of ![]() $K$ after removing

$K$ after removing ![]() $\sigma$ and

$\sigma$ and ![]() $\tau$, the simplices in

$\tau$, the simplices in ![]() $K \smallsetminus L$ must be re-attached, often losing the simplicial structure (see Figure 1, right). In general, there is no explicit or computable method to determine such attachments in arbitrary dimensions.

$K \smallsetminus L$ must be re-attached, often losing the simplicial structure (see Figure 1, right). In general, there is no explicit or computable method to determine such attachments in arbitrary dimensions.

Figure 1. Collapse (left) vs internal collapse (right).

Discrete Morse theory [Reference Forman18, Reference Forman19, Reference Kozlov22], developed by Forman in the 1990s as a combinatorial analogue of smooth Morse theory for manifolds, is a tool for studying the homotopy type of simplicial complexes via real-valued functions defined on them. Concretely, given a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ and a discrete Morse function

$K$ and a discrete Morse function ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$, there exists a reduced CW-complex built from the critical simplices of

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$, there exists a reduced CW-complex built from the critical simplices of ![]() $f$, denoted by

$f$, denoted by ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$, which is homotopy equivalent to

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$, which is homotopy equivalent to ![]() $K$. Moreover, a recent result establishes a connection between discrete Morse theory and simple homotopy theory: if

$K$. Moreover, a recent result establishes a connection between discrete Morse theory and simple homotopy theory: if ![]() $K$ has dimension

$K$ has dimension ![]() $N$, then there exists a sequence of collapses and expansions from

$N$, then there exists a sequence of collapses and expansions from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ through intermediate complexes of dimension at most

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ through intermediate complexes of dimension at most ![]() $N+1$ (also called an

$N+1$ (also called an ![]() $(N+1)$-deformation and denoted by

$(N+1)$-deformation and denoted by  $K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} {\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$) [Reference Fernández16]. This result relies on the fact that discrete Morse functions are equivalent to well-ordered sequences of internal collapses, which encode the deformation from

$K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} {\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$) [Reference Fernández16]. This result relies on the fact that discrete Morse functions are equivalent to well-ordered sequences of internal collapses, which encode the deformation from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ [Reference Fernández16, Reference Kozlov23]. The construction of the reduced complex

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ [Reference Fernández16, Reference Kozlov23]. The construction of the reduced complex ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$, however, often sacrifices the original simplicial and combinatorial structure of

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$, however, often sacrifices the original simplicial and combinatorial structure of ![]() $K$. The resulting attaching maps tend to be more intricate and are not explicitly determined, transferring the topological complexity of the space from many simplices with simple attaching maps to fewer cells (corresponding to the critical simplices) whose attaching maps are more complex. This work focuses on a particular case of discrete Morse theory in which it is possible to provide an explicit and computable method for describing these attaching maps, even in higher dimensions.

$K$. The resulting attaching maps tend to be more intricate and are not explicitly determined, transferring the topological complexity of the space from many simplices with simple attaching maps to fewer cells (corresponding to the critical simplices) whose attaching maps are more complex. This work focuses on a particular case of discrete Morse theory in which it is possible to provide an explicit and computable method for describing these attaching maps, even in higher dimensions.

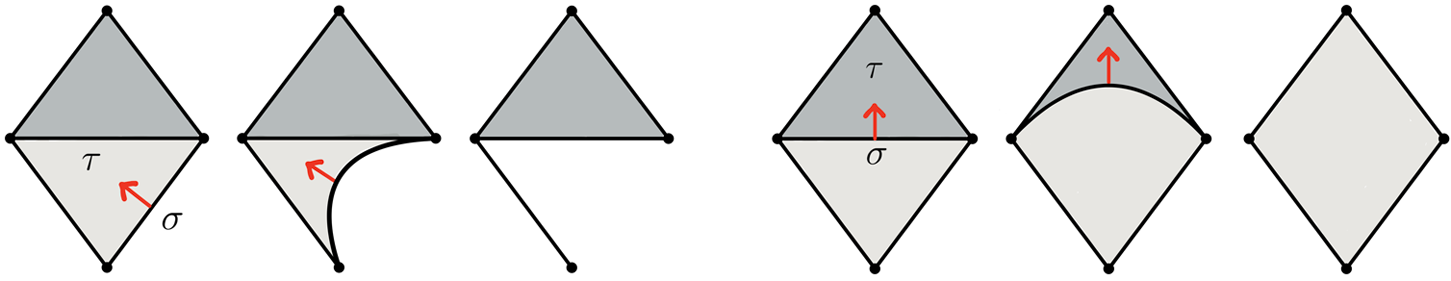

In 2012, a strong version of homotopy theory was developed by Barmak and Minian [Reference Barmak and Minian3]. This approach builds upon simple homotopy theory by introducing strong collapses of simplicial complexes. Inspired by vertex reductions on posets [Reference Stong33], strong collapses involve eliminating vertices ![]() $v$ (called dominated vertices) whose link is a simplicial cone. In general, removing (the open star of) vertices with a contractible link preserves the homotopy type, as a consequence of the Gluing Theorem [Reference Brown13]. Coned links, however, offer a systematic way to simple collapse

$v$ (called dominated vertices) whose link is a simplicial cone. In general, removing (the open star of) vertices with a contractible link preserves the homotopy type, as a consequence of the Gluing Theorem [Reference Brown13]. Coned links, however, offer a systematic way to simple collapse ![]() $K$ to the subcomplex

$K$ to the subcomplex ![]() $K \smallsetminus v$ (see Figure 2, left).

$K \smallsetminus v$ (see Figure 2, left).

Figure 2. Strong collapse (left) vs internal strong collapse (right).

Strong collapses, as collections of simultaneous collapses, are highly efficient. Unlike Whitehead’s collapses, strong collapses always yield the same minimal irreducible subcomplex — the strong core of ![]() $K$. However, the strong core of

$K$. However, the strong core of ![]() $K$ often coincides with

$K$ often coincides with ![]() $K$ itself, as many simplicial complexes lack dominated vertices. To overcome this limitation, one can consider performing strong collapses internally, where domination is restricted to a subcomplex of

$K$ itself, as many simplicial complexes lack dominated vertices. To overcome this limitation, one can consider performing strong collapses internally, where domination is restricted to a subcomplex of ![]() $K$ (see Figure 2, right). In such cases, a strategy must again be developed to recompute the attaching maps of the remaining cells, potentially compromising the simplicial structure of the reduced complex.

$K$ (see Figure 2, right). In such cases, a strategy must again be developed to recompute the attaching maps of the remaining cells, potentially compromising the simplicial structure of the reduced complex.

In this work, we establish a method for studying internal strong collapses and prove that the reduced CW-complex obtained from any sequence of such collapses is always regular (i.e., its attaching maps are homeomorphisms onto their images). As a consequence, the CW-structure of the reduced complex is fully combinatorially determined by the incidences of its cells. More broadly, we develop the theoretical foundations of strong Morse theory, a version of discrete Morse theory in which discrete Morse functions correspond to sequences of internal strong collapses. We propose an efficient algorithm for computing the reduced complex ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ for such discrete Morse functions

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ for such discrete Morse functions ![]() $f$. To demonstrate its applicability, we use this method to identify more efficient regular models of the simplicial complexes in the Library of Triangulations [Reference Benedetti, Lai, Lofano and Lutz5–Reference Benedetti and Lutz7] by Benedetti and Lutz.

$f$. To demonstrate its applicability, we use this method to identify more efficient regular models of the simplicial complexes in the Library of Triangulations [Reference Benedetti, Lai, Lofano and Lutz5–Reference Benedetti and Lutz7] by Benedetti and Lutz.

1.1. Motivation and related work

Classical discrete Morse theory does not provide an explicit description of the reduced homotopy equivalent CW-complex. A discrete Morse function on a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ induces a collection of critical simplices that correspond to the cells in the reduced CW-complex, along with information about their incidences, which is sufficient to determine the homology of the simplicial complex

$K$ induces a collection of critical simplices that correspond to the cells in the reduced CW-complex, along with information about their incidences, which is sufficient to determine the homology of the simplicial complex ![]() $K$. However, recovering the homotopy type of

$K$. However, recovering the homotopy type of ![]() $K$ from the reduced CW-complex requires a more refined understanding of the attaching maps. Hence, except in special cases—such as when the homotopy type is fully determined by the list of critical cells (e.g., wedges of spheres)—the algorithmic reconstruction of homotopy types from discrete Morse data remains an open problem.

$K$ from the reduced CW-complex requires a more refined understanding of the attaching maps. Hence, except in special cases—such as when the homotopy type is fully determined by the list of critical cells (e.g., wedges of spheres)—the algorithmic reconstruction of homotopy types from discrete Morse data remains an open problem.

Some progress has been made toward addressing this challenge. In [Reference Fernández16], the author develops a combinatorial framework to describe the attaching maps of the reduced CW-complex for 2-dimensional simplicial complexes equipped with a discrete Morse function with a single critical 0-simplex. The approach makes strong use of the correspondence between 2-complexes and group presentations. However, it does not extend to higher dimensions, as the homotopy types of ![]() $N$-dimensional complexes with

$N$-dimensional complexes with ![]() $N \gt 2$ generally cannot be fully captured combinatorially via group presentations. Rather than attempting to recover arbitrary attaching maps, the present work focuses on cases in which discrete Morse functions yield reduced complexes with particularly simple attaching maps—namely, homeomorphisms.

$N \gt 2$ generally cannot be fully captured combinatorially via group presentations. Rather than attempting to recover arbitrary attaching maps, the present work focuses on cases in which discrete Morse functions yield reduced complexes with particularly simple attaching maps—namely, homeomorphisms.

Our central goal is to develop a combinatorial and computable framework for a strong discrete Morse theory that allows for the explicit reconstruction of the reduced CW-complex. By restricting Morse functions to those induced by internal strong collapses, we prove that the resulting reduced complex is always a regular CW-complex, and hence its homotopy type can be entirely determined by the poset of incidence cells. Moreover, as strong Morse theory is a restricted version of classical discrete Morse theory, the reduced complex ![]() $(N+1)$-deforms to the original simplicial complex

$(N+1)$-deforms to the original simplicial complex ![]() $K$, where

$K$, where ![]() $N$ is the dimension of

$N$ is the dimension of ![]() $K$. Consequently, this theory also provides a computational method to perform

$K$. Consequently, this theory also provides a computational method to perform ![]() $(N+1)$-dimensional deformations.

$(N+1)$-dimensional deformations.

In [Reference Fernández-Ternero, Macías-Virgós, Scoville and Vilches17], the authors also establish connections between discrete Morse theory and strong collapses, focusing on general discrete Morse functions. Their work introduces a classification of internal collapses into critical and regular pairs, providing criteria to determine whether a sub-sequence of internal collapses is induced by a strong collapse. In contrast, our approach only focuses on the specific class of Morse functions derived from only internal strong collapses.

Our work builds on the main principles of Bestvina–Brady Morse theory [Reference Bestvina8, Reference Bestvina and Brady9]. In that framework, Morse functions are piecewise-linear (PL) functions defined on affine complexes, the critical points are the vertices, and changes in the topology of sublevel sets are studied through the descending links of vertices. Restricting to simplicial complexes and functions defined on their vertices, our theory refines this perspective by classifying vertices according to the structure of their descending links: either as descending dominated vertices (their descending links are simplicial cones, and induce internal strong collapses) or as strong critical vertices. While Bestvina–Brady Morse theory studies local changes in the homotopy type of sublevel sets, our approach also aims at the combinatorial and global reconstruction of a reduced complex induced by these local changes. In particular, instead of treating every vertex as critical, our theory identifies a potentially smaller subset of strong critical vertices that form the cells of the final reduced complex. The remaining descending dominated vertices are systematically collapsed, leading to a complete reconstruction of the homotopy type of the original complex.

A complementary perspective is presented in [Reference Nanda27, Reference Nanda, Tamaki and Tanaka28], where the authors encode the homotopy type of a simplicial complex endowed with a discrete Morse function into a combinatorially defined flow category. The classifying space of the flow category recovers the homotopy type of the original complex. However, these categories are often large and computationally challenging, limiting their application in algorithmic homotopy reconstruction. Indeed, while the computation of the nerve of a category can be exponential, the reconstruction of a regular CW-complex from its face poset is combinatorially direct.

1.2. Main results and outline

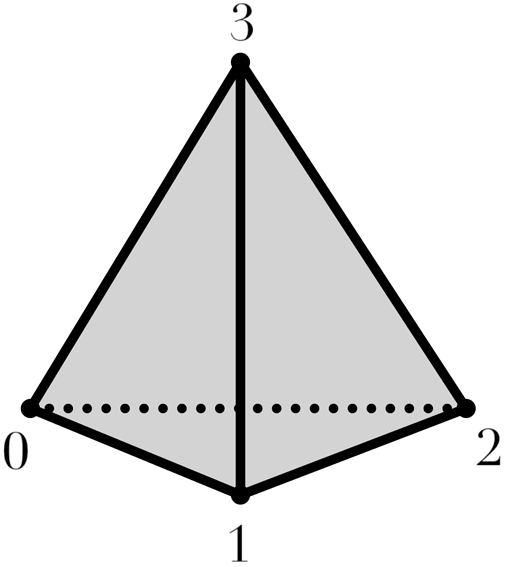

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on its set of vertices. The function

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on its set of vertices. The function ![]() $g$ induces a filtration of

$g$ induces a filtration of ![]() $K$ by subcomplexes, where each subcomplex consists of all simplices whose vertices lie below a given threshold in

$K$ by subcomplexes, where each subcomplex consists of all simplices whose vertices lie below a given threshold in ![]() $g$. For each vertex

$g$. For each vertex ![]() $v \in V(K)$, we consider the first subcomplex in the filtration that contains

$v \in V(K)$, we consider the first subcomplex in the filtration that contains ![]() $v$, and define its descending open star as the collection of simplices in that subcomplex that contain

$v$, and define its descending open star as the collection of simplices in that subcomplex that contain ![]() $v$. A vertex is called strong critical if, at the filtration step where it first appears, it is not dominated by any vertex from an earlier subcomplex.

$v$. A vertex is called strong critical if, at the filtration step where it first appears, it is not dominated by any vertex from an earlier subcomplex.

This filtration of ![]() $K$ leads to a strong homotopy analogue of the classical discrete Morse lemmas (Lemma 2.4). Intervals in the filtration without strong critical vertices correspond to strong collapses, while those with strong critical vertices introduce changes in the homotopy type, determined by the simplices in its descending open stars (Lemma 3.6). This reduction process produces a sequence of internal strong collapses, resulting in a reduced complex, called the strong internal core and denoted by

$K$ leads to a strong homotopy analogue of the classical discrete Morse lemmas (Lemma 2.4). Intervals in the filtration without strong critical vertices correspond to strong collapses, while those with strong critical vertices introduce changes in the homotopy type, determined by the simplices in its descending open stars (Lemma 3.6). This reduction process produces a sequence of internal strong collapses, resulting in a reduced complex, called the strong internal core and denoted by ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$. Notably, we prove that this reduced CW-complex is regular, that is, its attaching maps are homeomorphisms with its image.

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$. Notably, we prove that this reduced CW-complex is regular, that is, its attaching maps are homeomorphisms with its image.

Our main result in strong Morse theory is as follows.

Theorem (Strong Morse Theory)

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on the vertex set of

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on the vertex set of ![]() $K$. Then

$K$. Then ![]() $K$ is homotopy equivalent to a regular CW-complex

$K$ is homotopy equivalent to a regular CW-complex ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, whose cells are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in the descending open stars of the strong critical vertices of

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, whose cells are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in the descending open stars of the strong critical vertices of ![]() $g$. Moreover, if

$g$. Moreover, if ![]() $\dim(K) = N$, then

$\dim(K) = N$, then  $K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} {\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$.

$K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} {\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$.

We also show that this result is a particular case of classical discrete Morse theory (Theorem 3.9). More precisely, for every function ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$, there exists a discrete Morse function

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$, there exists a discrete Morse function ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ such that the critical simplices of

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ such that the critical simplices of ![]() $f$ are exactly the simplices in the descending open stars of the strong critical vertices of

$f$ are exactly the simplices in the descending open stars of the strong critical vertices of ![]() $g$. Moreover, the CW-complexes

$g$. Moreover, the CW-complexes ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ and

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ and ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ coincide. (By a slight abuse of notation, we denote both by

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ coincide. (By a slight abuse of notation, we denote both by ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}$ depending on the context:

${\mathrm{core}}$ depending on the context: ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ denotes the internal core obtained from a discrete Morse function

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ denotes the internal core obtained from a discrete Morse function ![]() $f$ on simplices, and

$f$ on simplices, and ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ denotes the strong internal core obtained from a function

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ denotes the strong internal core obtained from a function ![]() $g$ on vertices.)

$g$ on vertices.)

The combinatorial structure of the strong internal core admits a computational interpretation of internal strong collapses, which in turn leads to an efficient algorithm for their computation (Appendix A, Algorithms A1 and A2). An implementation is publicly available at https://github.com/ximenafernandez/Strong-Morse-Theory. To illustrate the effectiveness of this method, we apply it to examples from the Library of Triangulations [Reference Benedetti and Lutz7], a repository of challenging simplicial complexes frequently used in the study of homotopy types. The results of the reductions are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Comparison of reduction methods for simplicial complexes, averaged over 10 iterations. Bold values indicate cases where strong internal collapses yield the most significant size reduction. ![]() $Italicized$ values indicate cases where strong internal collapses also lead to a significant improvement in execution time compared to other methods

$Italicized$ values indicate cases where strong internal collapses also lead to a significant improvement in execution time compared to other methods

Table 2 Comparison of algorithmic reduction methods for simplicial complexes, averaged over 100 iterations. Bold values highlight cases where significant reduction is achieved via strong internal collapses (compared to other methods). ![]() $Italicized$ values indicate cases where significant reduction is only achieved through Whitehead collapses

$Italicized$ values indicate cases where significant reduction is only achieved through Whitehead collapses

Beyond its role in understanding homotopy types, the algorithmic reduction of simplicial complexes also has applications in topological data analysis, where the complexity of persistent homology computations increases rapidly with input size. For instance, computing degree-![]() $d$ persistent homology of the Vietoris–Rips filtration of a point cloud of size

$d$ persistent homology of the Vietoris–Rips filtration of a point cloud of size ![]() $N$ has worst-case complexity

$N$ has worst-case complexity ![]() $O(N^{3(d+2)})$ [Reference Otter, Porter, Tillmann, Grindrod and Harrington29]. The method introduced in [Reference Boissonnat, Pritam and Pareek12] uses strong collapses to simplify Vietoris–Rips filtrations prior to computing persistent homology. Since our results extend algorithmic simplification of complexes via internal strong collapses, they have potential applications in further optimising such filtration-based computations.

$O(N^{3(d+2)})$ [Reference Otter, Porter, Tillmann, Grindrod and Harrington29]. The method introduced in [Reference Boissonnat, Pritam and Pareek12] uses strong collapses to simplify Vietoris–Rips filtrations prior to computing persistent homology. Since our results extend algorithmic simplification of complexes via internal strong collapses, they have potential applications in further optimising such filtration-based computations.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 presents discrete Morse theory as a generalization of Whitehead’s collapses. In Section 3, we introduce a strong version of discrete Morse theory, based on strong collapses, which enables the recovery of a regular structure in the reduced CW-complex (the strong internal core). Section 4 provides a combinatorial construction of the strong internal core in terms of posets and acyclic matchings. Finally, Section 5 discusses algorithms for the simplification of simplicial complexes and presents experiments on the Library of Triangulations [Reference Benedetti and Lutz7]. The Appendix details algorithms for constructing the critical poset and a random strong internal core.

Notation. We use ![]() $\simeq$ for homotopy equivalences,

$\simeq$ for homotopy equivalences, ![]() $\cong$ for homeomorphisms, and

$\cong$ for homeomorphisms, and ![]() $|\cdot|$ for geometric realizations. The symbol

$|\cdot|$ for geometric realizations. The symbol ![]() $\sim$ is reserved for relations. The relation

$\sim$ is reserved for relations. The relation ![]() $\prec$ denotes the face relation between simplices of consecutive dimension.

$\prec$ denotes the face relation between simplices of consecutive dimension.

2. Discrete Morse theory as generalized collapses

In this section, we revisit discrete Morse theory, framing it as a combinatorial generalization of collapsibility of simplicial complexes, in the context of Whitehead’s simple homotopy theory. The classical foundations of simple homotopy theory can be found in Whitehead’s seminal works [Reference Whitehead35, Reference Whitehead36, Reference Whitehead38], Milnor’s influential article [Reference Milnor25], and Cohen’s textbook [Reference Cohen15]. Throughout this manuscript, we will restrict our attention to finite simplicial complexes.

Definition 2.1. Let ![]() $K$ and

$K$ and ![]() $L$ be simplicial complexes. There is an elementary collapse from

$L$ be simplicial complexes. There is an elementary collapse from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $L$ if there exist simplices

$L$ if there exist simplices ![]() $\sigma, \tau \in K$ such that

$\sigma, \tau \in K$ such that ![]() $L = K \smallsetminus \{\sigma, \tau\}$ and

$L = K \smallsetminus \{\sigma, \tau\}$ and ![]() $\tau$ is the unique simplex containing

$\tau$ is the unique simplex containing ![]() $\sigma$ properly in

$\sigma$ properly in ![]() $K$. In this case,

$K$. In this case, ![]() $\sigma$ is called a free face of

$\sigma$ is called a free face of ![]() $\tau$.

$\tau$.

A collapse, denoted ![]() $K {\searrow } L$, is a sequence

$K {\searrow } L$, is a sequence ![]() $K = K_n { \searrow^e } K_{n-1} { \searrow^e } \dots { \searrow^e } K_0 = L$ of elementary collapses from

$K = K_n { \searrow^e } K_{n-1} { \searrow^e } \dots { \searrow^e } K_0 = L$ of elementary collapses from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $L$. The inverse operation is called an expansion, denoted

$L$. The inverse operation is called an expansion, denoted ![]() $L {\nearrow } K$. If

$L {\nearrow } K$. If ![]() $K {\searrow } L$ we say that

$K {\searrow } L$ we say that ![]() $L$ is a weak core of

$L$ is a weak core of ![]() $K$, and if

$K$, and if ![]() $L$ has no free faces, we say it is minimal.

$L$ has no free faces, we say it is minimal.

There is an ![]() $N$-deformation, denoted

$N$-deformation, denoted  $K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N}} L$, between

$K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N}} L$, between ![]() $K$ and

$K$ and ![]() $L$ if there is a sequence

$L$ if there is a sequence ![]() $K = K_n, K_{n-1}, \dots, K_0 = L$ such that

$K = K_n, K_{n-1}, \dots, K_0 = L$ such that ![]() $K_i {\searrow } K_{i-1}$ or

$K_i {\searrow } K_{i-1}$ or ![]() $K_i {\nearrow } K_{i-1}$, and

$K_i {\nearrow } K_{i-1}$, and ![]() $\dim(K_i) \leq N$ for all

$\dim(K_i) \leq N$ for all ![]() $i$. If there exists an

$i$. If there exists an ![]() $N$-deformation for some

$N$-deformation for some ![]() $N \in \mathbb{N}$ between

$N \in \mathbb{N}$ between ![]() $K$ and

$K$ and ![]() $L$, it is said that they have the same simple homotopy type.

$L$, it is said that they have the same simple homotopy type.

Computing a minimal weak core of a simplicial complex provides a computational method for reducing its number of simplices while preserving its homotopy type. However, this approach is quite restrictive. For instance, many simplicial complexes lack free faces (e.g., triangulations of closed manifolds or famous examples such as the Dunce Hat [Reference Zeeman39] and Bing’s House [Reference Bing10]). Furthermore, a simplicial complex may have different (non-isomorphic) weak cores. For instance, if ![]() $D$ is any triangulation of the Dunce Hat, then

$D$ is any triangulation of the Dunce Hat, then ![]() $D \times I$ collapses to both

$D \times I$ collapses to both ![]() $D$ and the singleton

$D$ and the singleton ![]() $*$. Thus, the order of collapses matters. A more general approach is provided by

$*$. Thus, the order of collapses matters. A more general approach is provided by ![]() $N$-deformations (e.g., the above shows that

$N$-deformations (e.g., the above shows that ![]() $D \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^3 *$, even though its minimal weak core is

$D \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^3 *$, even though its minimal weak core is ![]() $D$ itself). Nonetheless, the existence of an

$D$ itself). Nonetheless, the existence of an ![]() $N$-deformation between two simplicial complexes not computable, as this would imply being able to algorithmically determine the contractibility of spaces.

$N$-deformation between two simplicial complexes not computable, as this would imply being able to algorithmically determine the contractibility of spaces.

Discrete Morse theory [Reference Forman18, Reference Forman19], inspired by its smooth counterpart [Reference Milnor, Spivak and Wells26], provides a more general combinatorial framework for simplifying the structure of a simplicial complex while preserving its homotopy type. Here, deformations are encoded in terms of discrete Morse functions.

Definition 2.2. Let ![]() $K$ be a simplicial complex. A function

$K$ be a simplicial complex. A function ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ defined on the simplices of

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ defined on the simplices of ![]() $K$ is called a discrete Morse function if, for every simplex

$K$ is called a discrete Morse function if, for every simplex ![]() $\sigma \in K$, the set

$\sigma \in K$, the set

contains at most one element. A simplex ![]() $\sigma \in K$ is said to be critical if

$\sigma \in K$ is said to be critical if ![]() $M(\sigma) = \varnothing$.

$M(\sigma) = \varnothing$.

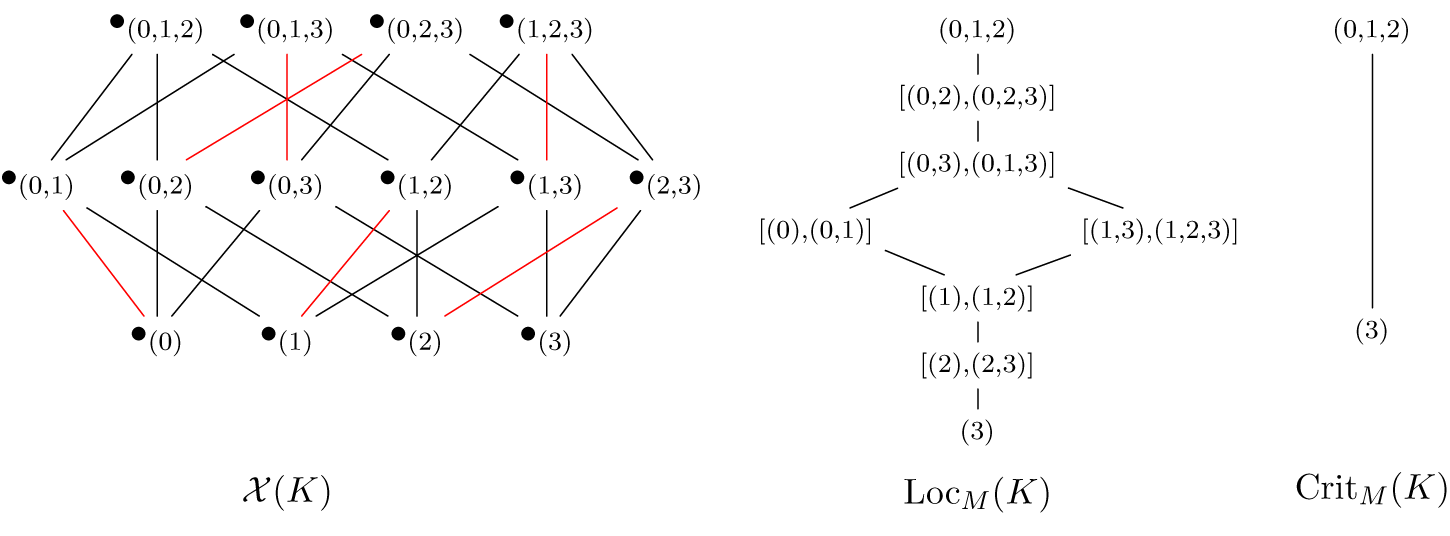

To every simplicial complex ![]() $K$, we associate its face poset

$K$, we associate its face poset ![]() ${\mathcal X}(K)$, which is the poset of simplices of

${\mathcal X}(K)$, which is the poset of simplices of ![]() $K$ ordered by the face relation. Each Morse function determines a pairing of simplices

$K$ ordered by the face relation. Each Morse function determines a pairing of simplices ![]() $M = \big\{\{\sigma, \tau\} \colon M(\sigma) = \{\tau\}\big\}$. It can be shown that

$M = \big\{\{\sigma, \tau\} \colon M(\sigma) = \{\tau\}\big\}$. It can be shown that ![]() $M$ is a matching on the set of simplices of

$M$ is a matching on the set of simplices of ![]() $K$. Moreover, the quotient of

$K$. Moreover, the quotient of ![]() ${\mathcal X}(K)$ obtained by identifying matched simplices inherits a poset structure (see Section 4 for more details). This matching is referred to as an acyclic matching Chari [Reference Chari14] proved that acyclic matchings are in correspondence with discrete Morse functions.

${\mathcal X}(K)$ obtained by identifying matched simplices inherits a poset structure (see Section 4 for more details). This matching is referred to as an acyclic matching Chari [Reference Chari14] proved that acyclic matchings are in correspondence with discrete Morse functions.

The main theorem in discrete Morse theory establishes the connection between critical simplices of discrete Morse functions and the homotopy type of the simplicial complex.

Theorem 2.3 (Forman [Reference Fernández16, Reference Forman18, Reference Forman19])

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex of dimension

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex of dimension ![]() $N$, and let

$N$, and let ![]() $f\colon K \to {\mathbb R}$ be a discrete Morse function. Then, there is an

$f\colon K \to {\mathbb R}$ be a discrete Morse function. Then, there is an ![]() $(N+1)$-deformation from

$(N+1)$-deformation from ![]() $K$ to a CW-complex with exactly one cell of dimension

$K$ to a CW-complex with exactly one cell of dimension ![]() $d$ for every critical

$d$ for every critical ![]() $d$-simplex of

$d$-simplex of ![]() $f$.

$f$.

We denote by ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ the CW-complex obtained from the critical simplices of

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ the CW-complex obtained from the critical simplices of ![]() $f$ in Theorem 2.3, and refer to it as the internal core of

$f$ in Theorem 2.3, and refer to it as the internal core of ![]() $K$ associated to

$K$ associated to ![]() $f$. It is important to note that Theorem 2.3 does not provide an explicit description of how the critical cells are attached along their boundaries in

$f$. It is important to note that Theorem 2.3 does not provide an explicit description of how the critical cells are attached along their boundaries in ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$. In [Reference Fernández16, Prop. 1.3, Thm. 1.6], the author offers a recursive construction of the attaching maps for the critical cells, based on the finiteness of

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$. In [Reference Fernández16, Prop. 1.3, Thm. 1.6], the author offers a recursive construction of the attaching maps for the critical cells, based on the finiteness of ![]() $K$; however, the construction is only made explicit for 2-dimensional cells.

$K$; however, the construction is only made explicit for 2-dimensional cells.

The deformation from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ is described locally by the Morse Lemma 2.4. Any discrete Morse function

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ is described locally by the Morse Lemma 2.4. Any discrete Morse function ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ induces a filtration of

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ induces a filtration of ![]() $K$ by sublevel subcomplexes: for each

$K$ by sublevel subcomplexes: for each ![]() $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$,

$\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$, ![]() $K_\alpha$ is the smallest subcomplex of

$K_\alpha$ is the smallest subcomplex of ![]() $K$ containing all simplices

$K$ containing all simplices ![]() $\sigma$ with

$\sigma$ with ![]() $f(\sigma) \leq \alpha$. The following result describes the evolution of the homotopy type complex along the filtration: intervals that do not contain critical simplices correspond to collapses, while those containing a single critical simplex account for homotopy changes.

$f(\sigma) \leq \alpha$. The following result describes the evolution of the homotopy type complex along the filtration: intervals that do not contain critical simplices correspond to collapses, while those containing a single critical simplex account for homotopy changes.

Lemma 2.4. (Thm. 3.3 and 3.4, [Reference Forman18])

Let ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ be a discrete Morse function.

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ be a discrete Morse function.

A. If

$f^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no critical simplices, then

$f^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no critical simplices, then  $K_\beta {\searrow } K_\alpha$.

$K_\beta {\searrow } K_\alpha$.B. If

$f^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains exactly one critical

$f^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains exactly one critical  $k$-simplex, then

$k$-simplex, then  $K_\beta \simeq K_\alpha \cup e^k$, where

$K_\beta \simeq K_\alpha \cup e^k$, where  $e^k$ is a

$e^k$ is a  $k$-dimensional cell.

$k$-dimensional cell.

From a combinatorial perspective, discrete Morse functions can be viewed as a totally ordered list of internal collapses.

Proposition 2.5. (Internal collapse [Reference Fernández16])

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex of dimension

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex of dimension ![]() $N$. If a subcomplex

$N$. If a subcomplex ![]() $K_0 \subseteq K$ collapses to a subcomplex

$K_0 \subseteq K$ collapses to a subcomplex ![]() $L_0$, then

$L_0$, then  $K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} L$, where

$K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} L$, where ![]() $L$ is a CW-complex obtained from

$L$ is a CW-complex obtained from ![]() $L_0$ by attaching one

$L_0$ by attaching one ![]() $k$-cell for each

$k$-cell for each ![]() $k$-simplex in

$k$-simplex in ![]() $K \smallsetminus K_0$.

$K \smallsetminus K_0$.

Proposition 2.5 also admits a formulation in terms of CW-complexes; see [Reference Fernández16, Proposition 1.3]. We refer to the deformation from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $L$ as an internal collapse. The collapse takes place within a subcomplex

$L$ as an internal collapse. The collapse takes place within a subcomplex ![]() $K_0 \subseteq K$, while the resulting deformation affects the entire complex through the reattachment of cells corresponding to the simplices in

$K_0 \subseteq K$, while the resulting deformation affects the entire complex through the reattachment of cells corresponding to the simplices in ![]() $K \smallsetminus K_0$.

$K \smallsetminus K_0$.

Internal collapses arise naturally in discrete Morse theory: for any discrete Morse function ![]() $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$, the transitions between sublevel complexes as described in the Morse Lemma (Lemma 2.4) correspond to internal collapses. Specifically, if the interval

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$, the transitions between sublevel complexes as described in the Morse Lemma (Lemma 2.4) correspond to internal collapses. Specifically, if the interval ![]() $(\alpha, \beta]$ contains no critical simplices, then

$(\alpha, \beta]$ contains no critical simplices, then ![]() $K_\beta \simeq K_\alpha$, and there is an internal collapse from

$K_\beta \simeq K_\alpha$, and there is an internal collapse from ![]() $K$ to a CW-complex obtained from

$K$ to a CW-complex obtained from ![]() $K_\alpha$ by attaching a

$K_\alpha$ by attaching a ![]() $k$-cell for each

$k$-cell for each ![]() $k$-simplex in

$k$-simplex in ![]() $K \smallsetminus K_\beta$. In general, the entire deformation from

$K \smallsetminus K_\beta$. In general, the entire deformation from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ can be interpreted as a well-ordered sequence of internal collapses.

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$ can be interpreted as a well-ordered sequence of internal collapses.

We summarize the viewpoint of discrete Morse theory as a generalization of classical collapses in the following statement.

Proposition 2.6. Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex.

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex.

(1) If

$K \searrow L$, then there exists a discrete Morse function

$K \searrow L$, then there exists a discrete Morse function  $f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ such that

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ such that  ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K) = L$.

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K) = L$.(2) If

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ is a discrete Morse function, then there exists a sequence of internal collapses from

$f \colon K \to \mathbb{R}$ is a discrete Morse function, then there exists a sequence of internal collapses from  $K$ to

$K$ to  ${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$.

${\mathrm{core}}_f(K)$.

3. Strong discrete Morse theory

Building on the strong homotopy theory for simplicial complexes introduced by Barmak and Minian [Reference Barmak and Minian3], we present a version of discrete Morse theory centred on the concept of internal strong collapses. We recall first the notion of strong collapses.

Given a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ and a vertex

$K$ and a vertex ![]() $v \in V(K)$, the open star of

$v \in V(K)$, the open star of ![]() $v$, denoted

$v$, denoted ![]() ${\mathrm{st}}(v, K)$, is the collection of simplices in

${\mathrm{st}}(v, K)$, is the collection of simplices in ![]() $K$ that contain

$K$ that contain ![]() $v$. The subcomplex of simplices disjoint from

$v$. The subcomplex of simplices disjoint from ![]() $v$ is denoted

$v$ is denoted ![]() $K \smallsetminus v$. The link of

$K \smallsetminus v$. The link of ![]() $v$ in

$v$ in ![]() $K$, denoted

$K$, denoted ![]() ${\mathrm{lk}}(v, K)$, is the subcomplex of

${\mathrm{lk}}(v, K)$, is the subcomplex of ![]() $K \smallsetminus v$ consisting of simplices

$K \smallsetminus v$ consisting of simplices ![]() $\sigma$ such that

$\sigma$ such that ![]() $\sigma \cup \{v\}$ is a simplex of

$\sigma \cup \{v\}$ is a simplex of ![]() $K$. A simplicial cone over

$K$. A simplicial cone over ![]() $K$ with apex

$K$ with apex ![]() $a$ (a vertex not in

$a$ (a vertex not in ![]() $K$) is the complex

$K$) is the complex ![]() $a*K$ consisting of all simplices of

$a*K$ consisting of all simplices of ![]() $K$, the vertex

$K$, the vertex ![]() $\{a\}$, and all simplices of the form

$\{a\}$, and all simplices of the form ![]() $\sigma \cup \{a\}$ with

$\sigma \cup \{a\}$ with ![]() $\sigma \in K$. The closed star of

$\sigma \in K$. The closed star of ![]() $v$, denoted

$v$, denoted ![]() $\overline{{\mathrm{st}}}(v, K)$, is the subcomplex

$\overline{{\mathrm{st}}}(v, K)$, is the subcomplex ![]() $v \ast {\mathrm{lk}}(v,K)$.

$v \ast {\mathrm{lk}}(v,K)$.

Definition 3.1. (Def. 2.1, [Reference Barmak and Minian3])

Let ![]() $K$ be a simplicial complex. A vertex

$K$ be a simplicial complex. A vertex ![]() $v$ of

$v$ of ![]() $K$ is dominated by a vertex

$K$ is dominated by a vertex ![]() $a$ if

$a$ if ![]() ${\mathrm{lk}}(v,K)$ is a simplicial cone

${\mathrm{lk}}(v,K)$ is a simplicial cone ![]() $a*K_0$, where

$a*K_0$, where ![]() $K_0$ is a subcomplex of

$K_0$ is a subcomplex of ![]() $K$. In that case, there is an elementary strong collapse from

$K$. In that case, there is an elementary strong collapse from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $K \smallsetminus v$, denoted

$K \smallsetminus v$, denoted ![]() $K \searrow K \smallsetminus v$. A strong collapse

$K \searrow K \smallsetminus v$. A strong collapse ![]() $K {\searrow \searrow} L$ from a simplicial complex

$K {\searrow \searrow} L$ from a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ to a subcomplex

$K$ to a subcomplex ![]() $L$ is a sequence of elementary strong collapses starting at

$L$ is a sequence of elementary strong collapses starting at ![]() $K$ and ending at

$K$ and ending at ![]() $L$. In that case, we say that

$L$. In that case, we say that ![]() $L$ is a strong core of

$L$ is a strong core of ![]() $K$. If

$K$. If ![]() $L$ has no dominated vertices, we say that

$L$ has no dominated vertices, we say that ![]() $L$ is a minimal strong core of

$L$ is a minimal strong core of ![]() $K$. (Note that he strong core is simply called a core in [Reference Barmak and Minian3]. We will use the term minimal strong core in this manuscript to avoid confusion with other core constructions. In [Reference Barmak and Minian3], it is proved that the mimimal strong core of a complex is unique modulo homeomorphisms.)

$K$. (Note that he strong core is simply called a core in [Reference Barmak and Minian3]. We will use the term minimal strong core in this manuscript to avoid confusion with other core constructions. In [Reference Barmak and Minian3], it is proved that the mimimal strong core of a complex is unique modulo homeomorphisms.)

If ![]() $v \in K$ is dominated by

$v \in K$ is dominated by ![]() $a$, then there is an explicit strong deformation retraction

$a$, then there is an explicit strong deformation retraction ![]() $|r_a|\colon |K| \to |K \smallsetminus v|$ induced by the simplicial map

$|r_a|\colon |K| \to |K \smallsetminus v|$ induced by the simplicial map

\begin{equation}

r_a(\sigma) =

\begin{cases}

\sigma & \text{if } v \notin \sigma, \\

\{a\} \cup \sigma \smallsetminus \{v\} & \text{if } v \in \sigma.

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

r_a(\sigma) =

\begin{cases}

\sigma & \text{if } v \notin \sigma, \\

\{a\} \cup \sigma \smallsetminus \{v\} & \text{if } v \in \sigma.

\end{cases}

\end{equation} More generally, if ![]() $K {\searrow\!\!\!\searrow} L$ via a sequence of elementary strong collapses

$K {\searrow\!\!\!\searrow} L$ via a sequence of elementary strong collapses

with ![]() $K_{i+1} = K_i \smallsetminus v_i$ and

$K_{i+1} = K_i \smallsetminus v_i$ and ![]() $v_i$ dominated by

$v_i$ dominated by ![]() $a_i \in K_i$, then there is a strong deformation retraction

$a_i \in K_i$, then there is a strong deformation retraction ![]() $|r|\colon |K| \to |L|$ induced by the composition

$|r|\colon |K| \to |L|$ induced by the composition

Moreover, if ![]() $K {\searrow \searrow} L$, then

$K {\searrow \searrow} L$, then ![]() $K {\searrow } L$ [Reference Barmak and Minian3, Rmk. 2.4]. That is, Whitehead’s notion of collapse is weaker than the notion of strong collapse.

$K {\searrow } L$ [Reference Barmak and Minian3, Rmk. 2.4]. That is, Whitehead’s notion of collapse is weaker than the notion of strong collapse.

Theorem (Thm. 2.11. [Reference Barmak and Minian3])

Any sequence of strong collapses from a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ to a subcomplex without dominated vertices yields a unique (up to isomorphism) subcomplex of

$K$ to a subcomplex without dominated vertices yields a unique (up to isomorphism) subcomplex of ![]() $K$. That is, the minimal strong core of a simplicial complex is unique up to isomorphism.

$K$. That is, the minimal strong core of a simplicial complex is unique up to isomorphism.

Recall that a CW-complex ![]() $K$ is regular if the attaching map

$K$ is regular if the attaching map ![]() $\varphi \colon S^{n-1} \to K^{(n-1)}$ of each open

$\varphi \colon S^{n-1} \to K^{(n-1)}$ of each open ![]() $n$-cell

$n$-cell ![]() $e^n$ is a homeomorphism onto its image

$e^n$ is a homeomorphism onto its image ![]() $\partial e^n$ in the

$\partial e^n$ in the ![]() $(n-1)$-skeleton. A regular CW-complex is said to be combinatorial if, for each cell

$(n-1)$-skeleton. A regular CW-complex is said to be combinatorial if, for each cell ![]() $e^n$, the attaching map — regarded as a cellular map from

$e^n$, the attaching map — regarded as a cellular map from ![]() $S^{n-1}$ endowed with a CW-structure — is a combinatorial map, meaning that it maps each open

$S^{n-1}$ endowed with a CW-structure — is a combinatorial map, meaning that it maps each open ![]() $k$-cell of

$k$-cell of ![]() $S^{n-1}$ homeomorphically onto an open

$S^{n-1}$ homeomorphically onto an open ![]() $k$-cell of

$k$-cell of ![]() $K$ (see [Reference Hog-Angeloni and Metzler20, Ch. II]). The geometric realization

$K$ (see [Reference Hog-Angeloni and Metzler20, Ch. II]). The geometric realization ![]() $|K|$ of any simplicial complex

$|K|$ of any simplicial complex ![]() $K$ is canonically a regular combinatorial CW-complex. Given a vertex

$K$ is canonically a regular combinatorial CW-complex. Given a vertex ![]() $v$ in a regular CW-complex

$v$ in a regular CW-complex ![]() $K$, we define the open star

$K$, we define the open star ![]() ${\mathrm{st}}(v,K)$ as the union of all open cells in

${\mathrm{st}}(v,K)$ as the union of all open cells in ![]() $K$ that contain

$K$ that contain ![]() $v$ as a face. We denote by

$v$ as a face. We denote by ![]() $\overline{e}$ the closure of a cell

$\overline{e}$ the closure of a cell ![]() $e \in K$, i.e., the smallest subcomplex of

$e \in K$, i.e., the smallest subcomplex of ![]() $K$ containing

$K$ containing ![]() $e$, which consists of

$e$, which consists of ![]() $e$ together with all its faces. Similarly, we denote by

$e$ together with all its faces. Similarly, we denote by ![]() $K \smallsetminus v$ the subcomplex of

$K \smallsetminus v$ the subcomplex of ![]() $K$ consisting of all cells

$K$ consisting of all cells ![]() $e$ such that

$e$ such that ![]() $v \notin \overline{e}$.

$v \notin \overline{e}$.

The following result formalizes the notion of an internal strong collapse, illustrated in Figure 2.

Theorem 3.3 Let ![]() $K$ be a regular combinatorial CW-complex, and let

$K$ be a regular combinatorial CW-complex, and let ![]() $w$ be a vertex of

$w$ be a vertex of ![]() $K$ such that the subcomplex

$K$ such that the subcomplex ![]() $K \smallsetminus w$ is a simplicial complex. Suppose there exists a subcomplex

$K \smallsetminus w$ is a simplicial complex. Suppose there exists a subcomplex ![]() $L \subseteq K \smallsetminus w$ such that

$L \subseteq K \smallsetminus w$ such that ![]() $K \smallsetminus w {\searrow \searrow} L$ via a sequence of strong collapses.

$K \smallsetminus w {\searrow \searrow} L$ via a sequence of strong collapses.

Then there exists a regular combinatorial CW-complex

\begin{equation*}

Z = L \cup \bigcup_{\ell} \tilde{e}_\ell,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

Z = L \cup \bigcup_{\ell} \tilde{e}_\ell,

\end{equation*} that is homotopy equivalent to ![]() $K$, where:

$K$, where:

•

$L$ is embedded as a subcomplex of

$L$ is embedded as a subcomplex of  $Z$,

$Z$,• for each cell

$e_\ell \in K$ such that

$e_\ell \in K$ such that  $w \in \overline{e_\ell}$, there is a corresponding

$w \in \overline{e_\ell}$, there is a corresponding  $\ell$-cell

$\ell$-cell  $\tilde{e}_\ell$ in

$\tilde{e}_\ell$ in  $Z$ not contained in

$Z$ not contained in  $L$, and

$L$, and• the attaching map of each

$\tilde{e}_\ell$ is induced from that of

$\tilde{e}_\ell$ is induced from that of  $e_\ell$ and the strong deformation retraction

$e_\ell$ and the strong deformation retraction  $|r| \colon |K \smallsetminus w| \to |L|$ determined by the strong collapse.

$|r| \colon |K \smallsetminus w| \to |L|$ determined by the strong collapse.

Moreover, if ![]() $\dim(K) = N$, then

$\dim(K) = N$, then  $K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} Z$.

$K \diagup\!\!\!\searrow^{^{N+1}} Z$.

Proof. Consider the pushout diagram

where ![]() $i$ is the inclusion map and

$i$ is the inclusion map and ![]() $|r| \colon |K \smallsetminus w| \to |L|$ is the strong deformation retraction induced by the strong collapse. Since

$|r| \colon |K \smallsetminus w| \to |L|$ is the strong deformation retraction induced by the strong collapse. Since ![]() $|r|$ is a homotopy equivalence and

$|r|$ is a homotopy equivalence and ![]() $i$ is a closed cofibration, the Gluing Theorem (see, e.g., [Reference Brown13, 7.5.7, Corollary 2]) implies that

$i$ is a closed cofibration, the Gluing Theorem (see, e.g., [Reference Brown13, 7.5.7, Corollary 2]) implies that ![]() $\bar{r}$ is also a homotopy equivalence.

$\bar{r}$ is also a homotopy equivalence.

We now define a regular combinatorial CW-structure on ![]() $Z$. Assume first that the collapse

$Z$. Assume first that the collapse ![]() $K \smallsetminus w {\searrow \searrow} L$ is elementary, i.e.,

$K \smallsetminus w {\searrow \searrow} L$ is elementary, i.e., ![]() $L = (K \smallsetminus w) \smallsetminus v$ for some vertex

$L = (K \smallsetminus w) \smallsetminus v$ for some vertex ![]() $v$ dominated by

$v$ dominated by ![]() $a \in K \smallsetminus w$.

$a \in K \smallsetminus w$.

The ![]() $0$-skeleton of

$0$-skeleton of ![]() $Z$ is defined as

$Z$ is defined as ![]() $Z^{(0)} = L^{(0)} \cup \{w\}$. We define a map

$Z^{(0)} = L^{(0)} \cup \{w\}$. We define a map ![]() $q \colon K^{(0)} \to Z^{(0)}$ by

$q \colon K^{(0)} \to Z^{(0)}$ by

\begin{equation*}

q(x) =

\begin{cases}

x & \text{if } x \in L^{(0)} \cup \{w\},\\

a & \text{if } x = v,

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

q(x) =

\begin{cases}

x & \text{if } x \in L^{(0)} \cup \{w\},\\

a & \text{if } x = v,

\end{cases}

\end{equation*} which agrees with the retraction ![]() $r$ on

$r$ on ![]() $K^{(0)} \smallsetminus \{w\}$.

$K^{(0)} \smallsetminus \{w\}$.

Inductively, suppose that a regular combinatorial CW-structure has been defined on ![]() $Z^{(\ell-1)}$, and that the map

$Z^{(\ell-1)}$, and that the map ![]() $q \colon K^{(\ell -1)} \to Z^{(\ell-1)}$ is combinatorial and coincides with the simplicial retraction

$q \colon K^{(\ell -1)} \to Z^{(\ell-1)}$ is combinatorial and coincides with the simplicial retraction ![]() $r$ on

$r$ on ![]() $(K \smallsetminus w)^{(\ell-1)}$. Let

$(K \smallsetminus w)^{(\ell-1)}$. Let ![]() $e$ be an

$e$ be an ![]() $\ell$-cell in

$\ell$-cell in ![]() $K$ with attaching map

$K$ with attaching map ![]() $\varphi\colon S^{\ell-1} \to K^{(\ell-1)}$.

$\varphi\colon S^{\ell-1} \to K^{(\ell-1)}$.

If ![]() $w \notin \overline{e}$, then

$w \notin \overline{e}$, then ![]() $e$ belongs entirely to the subcomplex

$e$ belongs entirely to the subcomplex ![]() $K \smallsetminus w$, and its image in

$K \smallsetminus w$, and its image in ![]() $Z$ is defined via

$Z$ is defined via ![]() $q = r$. Since

$q = r$. Since ![]() $r \colon K \smallsetminus w \to L$ is simplicial, and the attaching maps in

$r \colon K \smallsetminus w \to L$ is simplicial, and the attaching maps in ![]() $K\smallsetminus w$ are simplicial, it follows that

$K\smallsetminus w$ are simplicial, it follows that ![]() $q(e)$ inherits a regular combinatorial CW-structure. In particular, if

$q(e)$ inherits a regular combinatorial CW-structure. In particular, if ![]() $e \in L$, then

$e \in L$, then ![]() $q$ acts as the identity on

$q$ acts as the identity on ![]() $e$.

$e$.

If ![]() $w \in \overline{e}$, we distinguish three cases:

$w \in \overline{e}$, we distinguish three cases:

(1) If

$v \notin \overline{e}$, then

$v \notin \overline{e}$, then  $q$ acts as the identity on

$q$ acts as the identity on  $e$, and the attaching map of

$e$, and the attaching map of  $e$ remains unchanged in

$e$ remains unchanged in  $Z$, inheriting the regular combinatorial CW-structure from

$Z$, inheriting the regular combinatorial CW-structure from  $K$.

$K$.(2) If

$v \in \overline{e}$ but

$v \in \overline{e}$ but  $a \notin \overline{e}$, then

$a \notin \overline{e}$, then  $r$ sends

$r$ sends  $v$ to

$v$ to  $a$ in

$a$ in  $\partial e \cap (K\smallsetminus w)$, resulting in a relabelling, inducing a bijective identification on the boundary. The attaching map

$\partial e \cap (K\smallsetminus w)$, resulting in a relabelling, inducing a bijective identification on the boundary. The attaching map  $\tilde{\varphi} \colon S^{\ell - 1} \to Z^{(\ell - 1)}$ of

$\tilde{\varphi} \colon S^{\ell - 1} \to Z^{(\ell - 1)}$ of  $\tilde e\in Z$ is given by

$\tilde e\in Z$ is given by  $\tilde{\varphi} := r \circ \varphi$, and the image cell

$\tilde{\varphi} := r \circ \varphi$, and the image cell  $q(e)$ is obtained from

$q(e)$ is obtained from  $e$ via this relabelling.

$e$ via this relabelling.(3) If both

$v$ and

$v$ and  $a$ belong to

$a$ belong to  $\overline{e}$, then the retraction

$\overline{e}$, then the retraction  $r$ modifies the attaching map non-trivially. Since

$r$ modifies the attaching map non-trivially. Since  $K$ is regular and combinatorial, the boundary

$K$ is regular and combinatorial, the boundary  $\partial e$ is a PL

$\partial e$ is a PL  $(\ell -1)$-sphere. Let

$(\ell -1)$-sphere. Let

\begin{equation*}

A := |\overline{{\mathrm{st}}}(v, K \smallsetminus w)| \cap \partial e,\quad B := |{\mathrm{lk}}(v, K \smallsetminus w)| \cap \partial e.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

A := |\overline{{\mathrm{st}}}(v, K \smallsetminus w)| \cap \partial e,\quad B := |{\mathrm{lk}}(v, K \smallsetminus w)| \cap \partial e.

\end{equation*}Then

$A$ is a PL

$A$ is a PL  $(\ell -1)$-ball and

$(\ell -1)$-ball and  $B$ a PL

$B$ a PL  $(\ell-2)$-ball, and the strong collapse induces a retraction

$(\ell-2)$-ball, and the strong collapse induces a retraction  $r|_A \colon A \to B$. By [Reference Rourke and Sanderson32, Ch. 3], there exist regular neighbourhoods

$r|_A \colon A \to B$. By [Reference Rourke and Sanderson32, Ch. 3], there exist regular neighbourhoods  $U \supseteq A$ and

$U \supseteq A$ and  $V \supseteq B$ in

$V \supseteq B$ in  $\partial e$ and a map

$\partial e$ and a map  $f \colon \partial e \to \partial e$ such that

$f \colon \partial e \to \partial e$ such that  $ f|_A = r|_A $, and

$ f|_A = r|_A $, and  $ f|_{\partial e \setminus U} \colon \partial e \setminus U \to \partial e \setminus V $ is a PL homeomorphism. This induces a homeomorphism

$ f|_{\partial e \setminus U} \colon \partial e \setminus U \to \partial e \setminus V $ is a PL homeomorphism. This induces a homeomorphism

\begin{equation*}

\bar{f} \colon \partial e / \!\sim\ \longrightarrow \partial e, \quad x \sim r(x)\ \text{for } x \in A.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\bar{f} \colon \partial e / \!\sim\ \longrightarrow \partial e, \quad x \sim r(x)\ \text{for } x \in A.

\end{equation*}If

$ \varphi \colon S^{\ell -1} \to \partial e $ is the original attaching map of

$ \varphi \colon S^{\ell -1} \to \partial e $ is the original attaching map of  $e$, then the modified attaching map is given by

$e$, then the modified attaching map is given by

\begin{equation*}

\tilde \varphi := \bar f^{-1} \circ \varphi \colon S^{\ell-1} \longrightarrow \partial e / \sim \subseteq Z^{(\ell-1)}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\tilde \varphi := \bar f^{-1} \circ \varphi \colon S^{\ell-1} \longrightarrow \partial e / \sim \subseteq Z^{(\ell-1)}.

\end{equation*}Therefore, the cell

$ \tilde{e}$ is attached regularly, and inherits a combinatorial CW-structure. Define

$ \tilde{e}$ is attached regularly, and inherits a combinatorial CW-structure. Define  $q(e)= \tilde e$.

$q(e)= \tilde e$.

The general case follows by induction on the number of elementary strong collapses in the sequence

At each step, the same argument applies to the retraction ![]() $ K_i \to K_{i+1} $, ensuring that the regularity and combinatorial structure are preserved. Since

$ K_i \to K_{i+1} $, ensuring that the regularity and combinatorial structure are preserved. Since ![]() $w$ is not removed in the process, the identification maps never collapse an entire boundary sphere to a point.

$w$ is not removed in the process, the identification maps never collapse an entire boundary sphere to a point.

Thus, ![]() $Z$ is a regular combinatorial CW-complex homotopy equivalent to

$Z$ is a regular combinatorial CW-complex homotopy equivalent to ![]() $K$. The fact that this is an

$K$. The fact that this is an ![]() $(N+1)$-deformation follows from [Reference Fernández16, Prop. 1.3].

$(N+1)$-deformation follows from [Reference Fernández16, Prop. 1.3].

The previous result generalizes to the case where ![]() $K_0 {\searrow \searrow} L_0$ and

$K_0 {\searrow \searrow} L_0$ and ![]() $K_0$ is obtained from a simplicial complex

$K_0$ is obtained from a simplicial complex ![]() $K$ by successively removing vertices (together with their open stars). In this case,

$K$ by successively removing vertices (together with their open stars). In this case, ![]() $K_0$ is a full subcomplex of

$K_0$ is a full subcomplex of ![]() $K$, meaning that every simplex of

$K$, meaning that every simplex of ![]() $K$ whose vertices all belong to

$K$ whose vertices all belong to ![]() $V(K_0)$ is itself a simplex in

$V(K_0)$ is itself a simplex in ![]() $K_0$.

$K_0$.

Theorem 3.4 (Strong internal collapse)

Let ![]() $K$ be a simplicial complex of dimension

$K$ be a simplicial complex of dimension ![]() $N$, and let

$N$, and let ![]() $K_0 \subseteq K$ be a full subcomplex. Suppose

$K_0 \subseteq K$ be a full subcomplex. Suppose ![]() $K_0$ strong collapses to a subcomplex

$K_0$ strong collapses to a subcomplex ![]() $L_0$. Then

$L_0$. Then ![]() $K$ is

$K$ is ![]() $(N+1)$-homotopy equivalent to a combinatorial regular CW-complex

$(N+1)$-homotopy equivalent to a combinatorial regular CW-complex ![]() $L$ obtained from

$L$ obtained from ![]() $L_0$ by attaching one

$L_0$ by attaching one ![]() $k$-cell for each

$k$-cell for each ![]() $k$-simplex in

$k$-simplex in ![]() $K \smallsetminus K_0$.

$K \smallsetminus K_0$.

Proof. Follows by induction on the vertices in ![]() $V(K)\smallsetminus V(K_0)$, applying Theorem 3.3 at each step.

$V(K)\smallsetminus V(K_0)$, applying Theorem 3.3 at each step.

Under the assumptions of Theorem 3.4, we say that there is a strong internal collapse from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $L$.

$L$.

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on its vertex set. The function

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function on its vertex set. The function ![]() $g$ induces a filtration of

$g$ induces a filtration of ![]() $K$ by sublevel subcomplexes

$K$ by sublevel subcomplexes ![]() $\{K_\alpha\}_ {\alpha\in {\mathbb R}}$, where each

$\{K_\alpha\}_ {\alpha\in {\mathbb R}}$, where each ![]() $K_\alpha$ is the subcomplex spanned by the vertices in the sublevel set

$K_\alpha$ is the subcomplex spanned by the vertices in the sublevel set ![]() $g^{-1}\big((-\infty, \alpha]\big)$.

$g^{-1}\big((-\infty, \alpha]\big)$.

Definition 3.5. Let ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function, and let

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function, and let ![]() $v \in V(K)$ be a vertex. The descending open star of

$v \in V(K)$ be a vertex. The descending open star of ![]() $v$, denoted

$v$, denoted ![]() ${\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(v, K)$, is the open star of

${\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(v, K)$, is the open star of ![]() $v$ in the subcomplex

$v$ in the subcomplex ![]() $K_{g(v)}$. Similarly, the descending link of

$K_{g(v)}$. Similarly, the descending link of ![]() $v$, denoted

$v$, denoted  ${\mathrm{lk}}^\downarrow(v, K)$, is the link of

${\mathrm{lk}}^\downarrow(v, K)$, is the link of ![]() $v$ in

$v$ in ![]() $K_{g(v)}$. We say that

$K_{g(v)}$. We say that ![]() $v$ is descending dominated if it is dominated in

$v$ is descending dominated if it is dominated in ![]() $K_{g(v)}$ by a vertex

$K_{g(v)}$ by a vertex ![]() $a$ with

$a$ with ![]() $g(a) \lt g(v)$. Otherwise,

$g(a) \lt g(v)$. Otherwise, ![]() $v$ is called a strong critical vertex.

$v$ is called a strong critical vertex.

We have an analogous version of the classical discrete Morse Lemma 2.4 in this setting.

Lemma 3.6. Let ![]() $K$ be a simplicial complex and

$K$ be a simplicial complex and ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ a real-valued function.

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ a real-valued function.

A. If

$g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no strong critical vertices, then

$g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no strong critical vertices, then  $K_\beta {\searrow \searrow} K_\alpha$.

$K_\beta {\searrow \searrow} K_\alpha$.B. If

$g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains a single strong critical vertex

$g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains a single strong critical vertex  $w$, then

$w$, then  $K_\beta$ is homotopy equivalent to a CW-complex of the form

$K_\beta$ is homotopy equivalent to a CW-complex of the form

\begin{equation*}

K_\alpha \cup \bigcup_i e_i,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

K_\alpha \cup \bigcup_i e_i,

\end{equation*}where the cells

$e_i$ are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in

$e_i$ are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in  ${\mathrm{st}}^{\downarrow}(w, K)$. This correspondence preserves dimensions, and the attaching maps of the cells are determined as in Theorem 3.3, resulting in a regular CW-complex structure.

${\mathrm{st}}^{\downarrow}(w, K)$. This correspondence preserves dimensions, and the attaching maps of the cells are determined as in Theorem 3.3, resulting in a regular CW-complex structure.

Proof. The function ![]() $g$ induces a total order

$g$ induces a total order ![]() $\{v_1, v_2, \dots, v_n\}$ on

$\{v_1, v_2, \dots, v_n\}$ on ![]() $V(K)$ such that

$V(K)$ such that ![]() $g(v_i) \leq g(v_j)$ whenever

$g(v_i) \leq g(v_j)$ whenever ![]() $i \lt j$. For each

$i \lt j$. For each ![]() $i$, let

$i$, let ![]() $K_i$ be the subcomplex of

$K_i$ be the subcomplex of ![]() $K$ generated by all simplices whose vertices lie in

$K$ generated by all simplices whose vertices lie in ![]() $\{v_1, v_2, \dots, v_i\}$.

$\{v_1, v_2, \dots, v_i\}$.

For part A., assume that ![]() $g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no strong critical vertices. Then for each

$g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$ contains no strong critical vertices. Then for each ![]() $v_i \in g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$, the descending link

$v_i \in g^{-1}\big((\alpha, \beta]\big)$, the descending link  ${\mathrm{lk}}^{\downarrow}(v_i, K) = {\mathrm{lk}}(v_i, K_{g(v_i)})$ is a simplicial cone with apex

${\mathrm{lk}}^{\downarrow}(v_i, K) = {\mathrm{lk}}(v_i, K_{g(v_i)})$ is a simplicial cone with apex ![]() $a_i$, where

$a_i$, where ![]() $g(a_i) \lt g(v_i)$. Since

$g(a_i) \lt g(v_i)$. Since ![]() $K_i \subseteq K_{g(v_i)}$, we have

$K_i \subseteq K_{g(v_i)}$, we have

This subcomplex remains a cone with apex ![]() $a_i$. Therefore,

$a_i$. Therefore, ![]() $v_i$ is dominated in

$v_i$ is dominated in ![]() $K_i$ by

$K_i$ by ![]() $a_i$, and

$a_i$, and ![]() $K_i {\searrow\searrow^e } K_i \smallsetminus v_i = K_{i-1}$. Applying this inductively, we obtain a sequence of strong collapses from

$K_i {\searrow\searrow^e } K_i \smallsetminus v_i = K_{i-1}$. Applying this inductively, we obtain a sequence of strong collapses from ![]() $K_\beta$ to

$K_\beta$ to ![]() $K_\alpha$.

$K_\alpha$.

Part B. follows from part A. and Theorem 3.4.

Building on Theorem 3.4 and Lemma 3.6, we establish the following result, which formalize the relationship between internal strong collapses, regular CW-complexes, and discrete Morse theory.

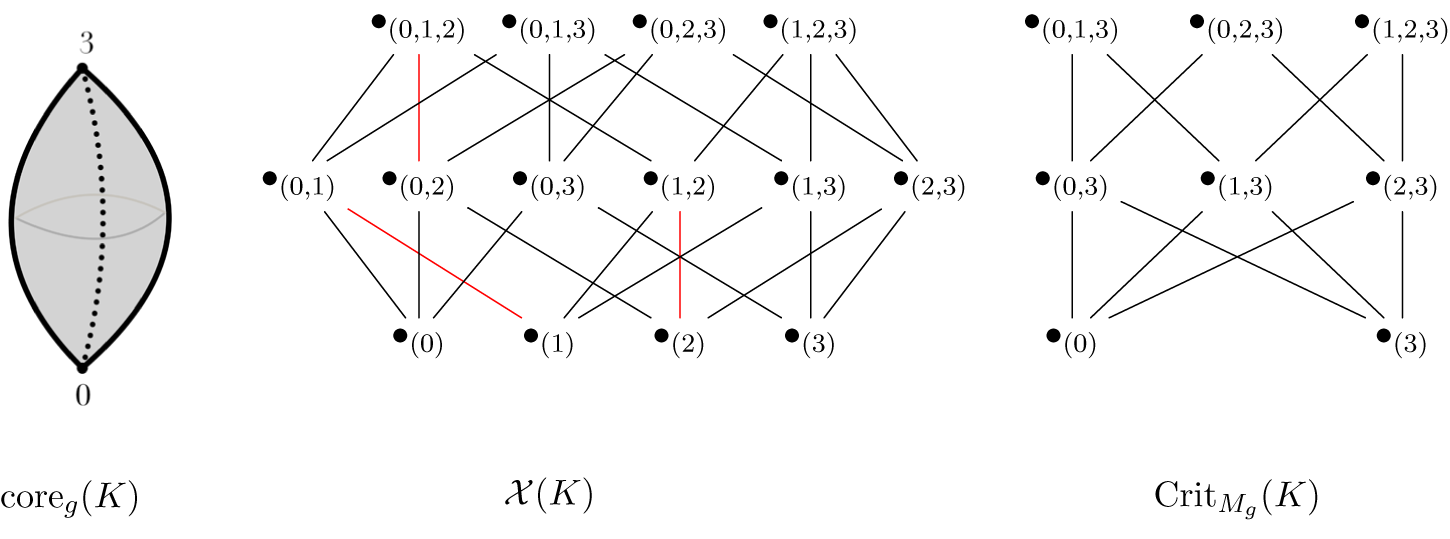

Theorem 3.7 (Strong discrete Morse theory)

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex, and let ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function. Then,

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ be a real-valued function. Then, ![]() $K$ is homotopy equivalent to a regular CW-complex

$K$ is homotopy equivalent to a regular CW-complex ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, whose cells are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in the descending open star of the strong critical vertices of

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, whose cells are in one-to-one correspondence with the simplices in the descending open star of the strong critical vertices of ![]() $g$.

$g$.

Proof. Subdivide the image of ![]() $g$ into subintervals, each satisfying the conditions of Lemma 3.6 A. or B., and iteratively apply the corresponding deformations to

$g$ into subintervals, each satisfying the conditions of Lemma 3.6 A. or B., and iteratively apply the corresponding deformations to ![]() $K$. The cells in the resulting CW-complex correspond to the simplices in

$K$. The cells in the resulting CW-complex correspond to the simplices in ![]() $\{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) \colon w \text{is a critical vertex in } K\}$.

$\{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) \colon w \text{is a critical vertex in } K\}$.

We denote by ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ the regular CW-complex obtained from the critical simplices of

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$ the regular CW-complex obtained from the critical simplices of ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ in Theorem 3.7, and refer to it as the strong internal core of

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ in Theorem 3.7, and refer to it as the strong internal core of ![]() $K$ associated to

$K$ associated to ![]() $g$. Notice that the strong internal core depends on a choice of dominating vertices for the strong internal collapses, but we omit this information unless necessary.

$g$. Notice that the strong internal core depends on a choice of dominating vertices for the strong internal collapses, but we omit this information unless necessary.

Proposition 3.8. (Connection to strong collapses)

If ![]() $K {\searrow \searrow} L$, then there exists a function

$K {\searrow \searrow} L$, then there exists a function ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ such that

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ such that ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K) = L$.

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K) = L$.

Proof. Let ![]() $v_1, v_2, \dots, v_n \in V(K)$ be the sequence of dominated vertices corresponding to a strong collapse from

$v_1, v_2, \dots, v_n \in V(K)$ be the sequence of dominated vertices corresponding to a strong collapse from ![]() $K$ to

$K$ to ![]() $L$, i.e., define

$L$, i.e., define ![]() $K_n = K$ and

$K_n = K$ and ![]() $K_{i-1} = K_i \smallsetminus v_i$, with each

$K_{i-1} = K_i \smallsetminus v_i$, with each ![]() $K_i {\searrow\searrow^e } K_{i-1}$ and

$K_i {\searrow\searrow^e } K_{i-1}$ and ![]() $K_0 = L$. Define a function

$K_0 = L$. Define a function ![]() $g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ by

$g \colon V(K) \to \mathbb{R}$ by

\begin{equation*}

g(v) =

\begin{cases}

i & \text{if } v = v_i, \\

0 & \text{if } v \in V(L).

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

g(v) =

\begin{cases}

i & \text{if } v = v_i, \\

0 & \text{if } v \in V(L).

\end{cases}

\end{equation*} We claim that the strong internal core, ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, coincides with

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, coincides with ![]() $L$. By construction, each

$L$. By construction, each ![]() $v_i$ is dominated in

$v_i$ is dominated in ![]() $K_i$ by some vertex

$K_i$ by some vertex ![]() $a_i \in K_i$. Since

$a_i \in K_i$. Since ![]() $v_i$ is removed at stage

$v_i$ is removed at stage ![]() $i$, and

$i$, and ![]() $a_i \in K_j$ for some

$a_i \in K_j$ for some ![]() $j \lt i$, it follows that

$j \lt i$, it follows that ![]() $g(a_i) \lt g(v_i)$. Therefore,

$g(a_i) \lt g(v_i)$. Therefore, ![]() $v_i$ is descending dominated. On the other hand, any vertex

$v_i$ is descending dominated. On the other hand, any vertex ![]() $v \in V(L)$ satisfies

$v \in V(L)$ satisfies ![]() $g(v) = 0$, and hence

$g(v) = 0$, and hence ![]() $g^{-1}((-\infty, g(v))) = \varnothing$. Thus,

$g^{-1}((-\infty, g(v))) = \varnothing$. Thus, ![]() $v$ cannot be descending dominated and is a strong critical vertex.

$v$ cannot be descending dominated and is a strong critical vertex.

Hence, the only strong critical vertices of ![]() $g$ are those in

$g$ are those in ![]() $L$, and the strong internal core,

$L$, and the strong internal core, ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, coincides with

${\mathrm{core}}_g(K)$, coincides with ![]() $L$.

$L$.

Theorem 3.9 (Connection to discrete Morse theory)

Let ![]() $K$ be a finite simplicial complex and let

$K$ be a finite simplicial complex and let ![]() $g\colon V(K) \to {\mathbb R}$ be a real-valued map. Then, there exists a discrete Morse function

$g\colon V(K) \to {\mathbb R}$ be a real-valued map. Then, there exists a discrete Morse function ![]() $f\colon K\to {\mathbb R}$ on

$f\colon K\to {\mathbb R}$ on ![]() $K$ such that its critical simplices are the simplices in

$K$ such that its critical simplices are the simplices in ![]() $\{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) : w \text{is a strong critical vertex of } g\}$. Moreover,

$\{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) : w \text{is a strong critical vertex of } g\}$. Moreover, ![]() ${\mathrm{core}}_{g}(K)\cong {\mathrm{core}}_{f}(K)$, that is the strong internal core associated to

${\mathrm{core}}_{g}(K)\cong {\mathrm{core}}_{f}(K)$, that is the strong internal core associated to ![]() $g$ is precisely the internal core associated to

$g$ is precisely the internal core associated to ![]() $f$.

$f$.

Proof. Let ![]() $C = \{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) : w \text{is a strong critical vertex of } g\}\subseteq K$. Given the correspondence between discrete Morse functions and acyclic matchings [Reference Chari14], we will construct an acyclic matching

$C = \{{\mathrm{st}}^\downarrow(w, K) : w \text{is a strong critical vertex of } g\}\subseteq K$. Given the correspondence between discrete Morse functions and acyclic matchings [Reference Chari14], we will construct an acyclic matching ![]() $M$ with critical simplices

$M$ with critical simplices ![]() $C$ as follows. For each simplex

$C$ as follows. For each simplex ![]() $\sigma \in K$ containing descending dominated vertices, let

$\sigma \in K$ containing descending dominated vertices, let

and let ![]() $a_\sigma$ denote the vertex dominating

$a_\sigma$ denote the vertex dominating ![]() $v_\sigma$. The pairing

$v_\sigma$. The pairing ![]() $M$ is then defined as follows: if

$M$ is then defined as follows: if ![]() $a_\sigma \in \sigma$, we include the pair

$a_\sigma \in \sigma$, we include the pair ![]() $(\sigma \setminus \{a_\sigma\}, \sigma)$ in

$(\sigma \setminus \{a_\sigma\}, \sigma)$ in ![]() $M$; otherwise, we include the pair

$M$; otherwise, we include the pair ![]() $(\sigma, \sigma \cup \{a_\sigma\})$ in

$(\sigma, \sigma \cup \{a_\sigma\})$ in ![]() $M$.

$M$.

To verify that ![]() $M$ is a matching, assume for contradiction that a simplex in

$M$ is a matching, assume for contradiction that a simplex in ![]() $K$ is matched to more than one simplex. Without loss of generality, suppose

$K$ is matched to more than one simplex. Without loss of generality, suppose ![]() $(\sigma, \{a\}\cup \sigma) \in M$ with

$(\sigma, \{a\}\cup \sigma) \in M$ with ![]() $v_\sigma$ the associated descending dominated vertex. If there exists another pair

$v_\sigma$ the associated descending dominated vertex. If there exists another pair ![]() $(\{a\}\cup\sigma, \{a',a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$, then

$(\{a\}\cup\sigma, \{a',a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$, then ![]() $a'$ dominates a vertex

$a'$ dominates a vertex ![]() $v' \in \sigma$. Since

$v' \in \sigma$. Since ![]() $v'$ must also satisfy

$v'$ must also satisfy ![]() $v' = \arg\max\{g(v) \colon v \in \sigma$ is descending dominated

$v' = \arg\max\{g(v) \colon v \in \sigma$ is descending dominated![]() $\}$ this contradicts the uniqueness of

$\}$ this contradicts the uniqueness of ![]() $v_\sigma$. Alternatively, if there exists a pair

$v_\sigma$. Alternatively, if there exists a pair ![]() $(\sigma', \{a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$, then

$(\sigma', \{a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$, then ![]() $a\sigma = \{a'\}\cup\sigma'$ implies

$a\sigma = \{a'\}\cup\sigma'$ implies ![]() $\sigma = \{a'\}\cup\tau$ and

$\sigma = \{a'\}\cup\tau$ and ![]() $\sigma' = \{a\}\cup\tau$ for some simplex

$\sigma' = \{a\}\cup\tau$ for some simplex ![]() $\tau$. This forces

$\tau$. This forces ![]() $\tau$ to contain two distinct dominated vertices,

$\tau$ to contain two distinct dominated vertices, ![]() $v_\sigma$ and

$v_\sigma$ and ![]() $v'$, each maximizing

$v'$, each maximizing ![]() $g(v)$, which is again a contradiction. Therefore,

$g(v)$, which is again a contradiction. Therefore, ![]() $M$ is a valid matching.

$M$ is a valid matching.

To establish that ![]() $M$ is acyclic, consider any pair

$M$ is acyclic, consider any pair ![]() $(\sigma, \{a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$. For any

$(\sigma, \{a\}\cup\sigma) \in M$. For any ![]() $\tau \succ \sigma$, we claim that

$\tau \succ \sigma$, we claim that ![]() $(\tau \smallsetminus \{a'\}, \tau) \notin M$ for any

$(\tau \smallsetminus \{a'\}, \tau) \notin M$ for any ![]() $a' \neq a$. Since

$a' \neq a$. Since ![]() $\tau \succ \sigma$, the simplex

$\tau \succ \sigma$, the simplex ![]() $\tau$ contains

$\tau$ contains ![]() $v_\sigma$. If

$v_\sigma$. If ![]() $v_\sigma$ also satisfies

$v_\sigma$ also satisfies ![]() $v_\sigma = \arg \max\{g(v) \colon v \in \tau \text{is a descending dominated vertex}\}$, then

$v_\sigma = \arg \max\{g(v) \colon v \in \tau \text{is a descending dominated vertex}\}$, then ![]() $(\tau, \{a\}\cup\tau) \in M$, as