– How can one die in Sarajevo?

– You can be killed in many ways. You can be killed physically, in your body, which is the main way. But I think that many more people have been killed in their minds, in their souls.

Bure, singer of the rock band Sikter, 1994Footnote 1

Introduction

Armed conflicts not only kill bodies, but also kill minds, as claimed by Bure, singer of the rock band Sikter, which remained active during the Siege of Sarajevo (1992–96). During war, individuals often live in constant fear of being injured or dying and may witness the deaths of their loved ones. They can be forced to leave their homes and find themselves deprived of the means to sustain their livelihoods, and access to basic necessities such as food and water may be severely disrupted. Given these circumstances, it is unsurprising that one in five people living in situations of armed conflict suffers from a mental health condition,Footnote 2 and that more broadly, elevated levels of psychological distress are common among populations affected by armed conflict.Footnote 3 Furthermore, the detrimental effects of war on mental health can extend across generations, a phenomenon known as intergenerational trauma.Footnote 4

In recent years, a small but growing number of legal experts have begun to engage with the often-overlooked issue of mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings. Notable contributors to this emerging field include Solomon,Footnote 5 LieblichFootnote 6 and Lubell,Footnote 7 and the previous work of the present author can also be added to this list.Footnote 8 However, most existing studies address this subject primarily through the lenses of international humanitarian law (IHL) or international criminal law – for instance, some scholars have examined incidental mental harm within the framework of the IHL principle of proportionality,Footnote 9 while others have investigated how international criminal courts evaluate the psychological effects of armed conflict.Footnote 10 By contrast, perspectives grounded in international human rights law (IHRL) remain largely under-explored.Footnote 11

In particular, scant attention has been devoted to the role that human rights supervisory bodies play in shaping States’ obligations towards the mental health of the population in conflict and post-conflict contexts. Since it is now widely recognized that IHRL is applicable in situations of armed conflict, and since several human rights instruments protect the right to health (including mental health), it is crucial to examine how these supervisory bodies engage with the issue of mental health during and after hostilities.

Building on this premise, the present paper seeks to answer the following research question: how do United Nations (UN) human rights treaty bodies address mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings in their Concluding Observations? UN human rights treaty bodies (hereinafter referred to simply as treaty bodies) are committees of independent experts responsible for overseeing the implementation of the core international human rights treaties. Concluding Observations are documents through which these bodies articulate their recommendations following the review of States’ periodic reports.

Our analysis shows that most recommendations concerning mental health in conflict contained in the Concluding Observations call for particular attention to the mental health of children, especially child combatants, and women, particularly those who are victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Regarding the thematic issues addressed, the recommendations emphasize the need to ensure the availability and accessibility of mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS). The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC Committee, the treaty body for the Convention on the Rights of the Child, CRC) is the treaty body that has adopted the largest number of recommendations, followed by the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee, the treaty body for the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, CEDAW) and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR, the treaty body for the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, ICESCR), which have adopted the same number as each other. Overall, recommendations concerning the mental health of persons affected by conflict accounted for less than 0.1% of the total recommendations issued by treaty bodies present in the Universal Human Rights Index (UHRI) database.

This study is based on a textual analysis of the Concluding Observations conducted through the UHRI database, which was chosen for its advanced filtering capabilities.Footnote 12 The research combines elements of content and thematic analysis. Content analysis was employed to identify the most relevant recommendations contained in the Concluding Observations, followed by a thematic analysis to identify target groups and thematic issues. The analysis was carried out using Excel software and manual coding; this was possible because of the limited number of recommendations found (105). As observed by Lyons, studies examining Concluding Observations often lack methodological rigourFootnote 13 – to counter this tendency, the present study provides a detailed explanation of the methodology adopted.

After a brief preliminary section on definitions and terminology, this paper is structured in two main parts: theoretical and practical. The theoretical part examines the legal basis and core components of the right to mental health, the application of this right in situations of armed conflict and the role of treaty bodies’ Concluding Observations in guiding States in the implementation of human rights conventions. The practical part investigates how mental health is addressed in the Concluding Observations – it outlines the study’s methodology and limitations, presents the results and discusses them. The paper concludes with a summary of the findings, recommendations for future action, and a few final reflections.

Definitions and terminology

Before delving further into the topic, a few notes on concepts and terminology are necessary. While treaty bodies do not generally provide definitions of the mental health-related terms they use, we find it useful to provide the most common definitions of the key terms employed by this paper and adopted by the committees, such as “mental health”, “mental disorder” and “psychosocial support”. Given that the definitions provided below come from institutional sources within the UN system (such as the World Health Organization (WHO)) or closely connected to it (such as the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement), it is likely that treaty bodies had these definitions in mind when drafting their Concluding Observations.

“Mental health” is defined by WHO as “a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community”.Footnote 14 WHO further explains that mental health is “an integral component of health and well-being and is more than the absence of mental disorders”.Footnote 15 Although other definitions of mental health have been proposed in the literature,Footnote 16 WHO’s formulation remains the most widely used and authoritative in the international legal arena, given the Organization’s institutional leadership on global health issues.

A “mental disorder” is defined by WHO as a syndrome “characterized by a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour”, which “is usually associated with distress or impairment in important areas of functioning”.Footnote 17 The expression “mental health condition” is often used as a synonym for “mental disorder”, and is sometimes preferred over the latter because it is perceived as less paternalistic.Footnote 18 Mental disorders/mental health conditions include depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders and eating disorders. Within the human rights sphere, persons with mental health conditions are frequently referred to as “persons with psychosocial disabilities”, an expression that emphasizes the barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society.Footnote 19

To explain the terms “psychosocial support”, “psychological support” and “specialized mental health care”, it is possible to rely on the MHPSS framework of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.Footnote 20 “Psychosocial support” concerns the promotion of mental health, resilience and social interaction within communities. It is generally directed at the wider population, but it may also target individuals and groups at risk. “Psychological support” encompasses prevention and treatment for persons experiencing more complex psychological distress, and includes activities such as counselling and psychotherapy. “Specialized mental health care” consists of clinical care and treatment for persons with mental health conditions and is commonly also referred to as “psychiatric care”.Footnote 21

The theory: The right to mental health, armed conflict, and Concluding Observations

The right to mental health

The first global recognition of health as a human right appeared in the WHO Constitution, the preamble of which declares that “[t]he enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition”.Footnote 22 Subsequently, the right to health was codified in several human rights instruments. The most relevant provision on this right is commonly considered to be Article 12 of the ICESCR.Footnote 23 Other international human rights conventions that safeguard the right to health include the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD, with its corresponding treaty body, the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, CERD),Footnote 24 the CEDAW,Footnote 25 the CRCFootnote 26 and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, with its corresponding treaty body, the CRPD Committee).Footnote 27 At the regional level, the right to health is recognized across all principal regional human rights systems – namely, the European, African and inter-American ones.Footnote 28

The right to health encompasses both physical and mental health. While some instruments do not explicitly mention mental health in their provisions on the right to health, this right has constantly been interpreted to include the mental dimension. This interpretation likely stems from the fact that the ICESCR, which provides the most authoritative articulation of the right to health, expressly refers to mental health as an integral component of the right: this treaty recognizes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”.Footnote 29 Similarly, the WHO Constitution offers a definition of health that includes mental health.Footnote 30

The main features of the right to mental health, which can be derived from the CESCR’s General Comment 14 on the right to health, are as follows.Footnote 31

• Access to mental health care and underlying determinants. The right to mental health encompasses both the right to mental health care and the right to the underlying determinants of health. Therefore, it not only contains the right to receive treatment, but also extends to the determinants of health, such as “food and nutrition, housing, access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, safe and healthy working conditions, and a healthy environment”.Footnote 32

• AAAQ framework. Mental health services, goods and facilities must be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality (the “AAAQ framework”).Footnote 33 Availability requires that health facilities, goods and services for mental health exist in sufficient quantity within the State. Accessibility encompasses several sub-dimensions: non-discrimination, physical accessibility and economic accessibility. Non-discrimination implies that mental health facilities, goods and services are accessible to all without discrimination, physical accessibility requires that persons with disabilities are able to access mental health facilities, and economic accessibility entails that mental health services are affordable. Acceptability requires that services, goods and facilities for mental health adhere to medical ethics and are culturally appropriate. Quality entails that mental health services, goods and facilities meet medical and scientific standards and are of good quality – for instance, by guaranteeing that mental health professionals are properly trained.

• The principle of progressive realization. Like other socio-economic rights, the right to mental health is subject to the principle of progressive realization.Footnote 34 Under this principle, States are required to take measures, to the maximum of their available resources, to progressively achieve the full realization of the right. Nevertheless, States are bound by certain core minimum obligations, meaning that minimum essential levels of the right to mental health must always be upheld. These core obligations include, for example, ensuring non-discriminatory access to mental health care and the provision of essential drugs.

• Participation and accountability. The realization of the right to mental health requires the participation of the population in decision-making related to mental health.Footnote 35 Participation can take different forms, such as democratic elections or public consultations on the development of mental health policies. In addition, States must be held accountable for their (in)action on the right to mental health.Footnote 36 Accountability may be administrative, political or judicial: administrative accountability includes mechanisms such as reviews of how public funds are spent, political accountability is obtained through democratic elections, and judicial accountability involves the adjudication of violations of the right to mental health in courts.

Along with General Comment 14, a range of other documents must be taken into account to fully grasp the scope and content of the right to mental health. These include several recent Human Rights Council resolutions,Footnote 37 reports from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights,Footnote 38 and the seminal guidance Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation,Footnote 39 developed in 2023 by WHO and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN Human Rights). Collectively, these documents underscore that a modern understanding of mental health and human rights law entails a paradigm shift away from biomedical and coercive models and towards human rights-based, person-centred and community-anchored approaches. They also highlight the need to address the social and economic factors that impact mental health and the importance of realizing cross-sectoral interventions.

Finally, the right to mental health must be considered in connection with other human rights. First and foremost, this right is closely linked with other socio-economic rights such as the right to safe food and nutrition, the right to access safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, and the right to healthy occupational and environmental conditions, as noted above. In addition, the paradigm shift outlined in the previous paragraph emphasizes the necessary interaction between the right to mental health and several civil and political rights, including the rights to liberty and security of person, freedom from torture and ill-treatment, and freedom from discrimination. In this sense, the right to mental health is inextricably connected with the CRPD, which also protects persons with psychosocial disabilities.

The right to mental health in situations of armed conflict

For a long time, the application of IHRL (and thus, the right to mental health) to conflict settings was contested. It was commonly held that IHRL was the law applicable in times of peace, while IHL was the law applicable during conflict.Footnote 40 IHL, also known as the law of armed conflict, is the branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of hostilities; it “protects persons who are no longer directly participating in the hostilities and restricts the means and methods of warfare”.Footnote 41 IHL is codified in various treaties, primarily the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols of 1977.Footnote 42

However, it is now widely recognized that IHRL continues to apply in situations of armed conflict – in other words, IHRL remains applicable at all times, both in peace and in war. This position has been definitively confirmed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its 1996 Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Nuclear Weapons Advisory Opinion), its 2004 Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (Wall Advisory Opinion), and the 2005 Case Concerning Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo, in which the Court notably affirmed the applicability of human rights treaties, including those protecting socio-economic rights, in conflict settings.Footnote 43 Human rights treaty bodies, as well as regional and domestic courts, have also reached this conclusion.Footnote 44 Even before these Advisory Opinions, several scholars had already argued in favour of the applicability of human rights during armed conflict.Footnote 45 As a result, situations of hostilities are governed by two main branches of international law: IHL and IHRL.Footnote 46

The continued applicability of IHRL in situations of armed conflict entails that the right to health, including the right to mental health, also applies in such situations.Footnote 47 Nonetheless, a State engaged in a conflict may encounter significant challenges in fulfilling its obligations related to the right to mental health. IHRL generally recognizes that States may face difficulties in fully implementing human rights in certain situations and allows them to derogate from or limit human rights under specific circumstances. While the ICESCR (which, as seen above, is the reference treaty for the protection of the right to health) does not contain a derogation clause, its Article 4 permits the State to subject the rights enshrined in the Covenant to limitations.Footnote 48 In situations of hostilities, such limitations could be justified, for example, on grounds of national security.Footnote 49 For a limitation to be lawful, it must respect certain criteria: it must be determined by law, pursue the legitimate aim of promoting “the general welfare in a democratic society”,Footnote 50 and be necessary and proportionate to reach this aim.Footnote 51 Thus, during armed conflict, States can limit the right to mental health.

Be that as it may, the principle of progressive realization remains a continuous obligation of the State even during hostilities. This principle “does not dilute certain immediate obligations of States, including taking concrete steps towards the full realization of the right to health”, which encompasses measures to progressively provide mental health services.Footnote 52 Moreover, any retrogressive measure “would require the most careful consideration and would need to be fully justified by reference to the totality of the rights provided for in the Covenant and in the context of the full use of the maximum available resources”.Footnote 53 Retrogressive measures are those that, directly or indirectly, result in a decline in the enjoyment of human rights protected under the ICESCR. The mere existence of an armed conflict does not, by itself, justify the adoption of retrogressive measures.Footnote 54 Accordingly, even in situations of armed conflict, States must take deliberate and concrete steps toward the realization of the right to mental health.

Concluding Observations of UN treaty bodies

To better understand State obligations under the right to mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings, this paper examines how UN treaty bodies have addressed this right in their Concluding Observations. At the international level, the implementation of UN human rights treaties (including those protecting the right to health) is monitored by the UN treaty bodies. These bodies are composed of independent experts, who act in their individual capacity and not as representatives of the States of which they are nationals. Currently, there are ten UN human rights treaty bodies.Footnote 55 They perform several key functions, including issuing General Comments, reviewing State reports on treaty implementation, and publishing Concluding Observations. Most treaty bodies are allowed to consider individual complaints and to conduct inquiries.

This article focuses on Concluding Observations, which are documents in which a treaty body expresses its concerns, observations and recommendations in response to a State’s periodic report on the implementation of the treaty. Human rights treaties typically require States Parties to submit such reports every four to five years, outlining the measures they have undertaken to fulfil their treaty obligations. Treaty bodies often also receive information on how the State is implementing the treaty from other sources, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academic establishments and UN entities.Footnote 56 Taking all available information into account and engaging in a constructive dialogue with the State Party delegation, the treaty body reviews the report and subsequently issues its Concluding Observations. Concluding Observations are not legally binding and the entire process is non-adversarial and non-adjudicative in nature.Footnote 57

Concluding Observations were chosen as the subject of this analysis for two main reasons. First, they contribute to defining human rights obligations. O’Flaherty notes that they are key instruments to interpreting international human rights conventions,Footnote 58 and similarly, Myer argues that they have helped elucidate the content of human rights.Footnote 59 Concluding Observations are particularly valuable due to their practical orientation – by highlighting specific concerns and requiring action in particular areas, they outline concrete measures that States should implement. One common criticism of IHRL is its abstraction and vagueness, and Concluding Observations help to address this by offering more tangible guidance, thereby substantiating States’ obligations under human rights treaties.Footnote 60

Second, Concluding Observations are widely regarded as authoritative, despite being non-binding. They are statements coming from independent experts appointed expressly to review treaty implementation. In addition, although Concluding Observations are not binding, they are based on legally binding treaty obligations. Zhang observes that their interpretation is typically deemed to be “of great value”,Footnote 61 while Meier and Kim argue that Concluding Observations possess the “legal authority” to clarify treaty provisions.Footnote 62 The relevance of these documents is evident even in the international legal jurisprudence. The ICJ took into account Concluding Observations issued by the Committee on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR, also known as the Human Rights Committee) and the CESCR when interpreting Israel’s obligations in the 2004 Wall Advisory Opinion.Footnote 63 This authority also extends to the domestic level: the majority of States seem to “take the reporting procedure seriously”,Footnote 64 and national courts have also relied on Concluding Observations in their judgments.Footnote 65 For instance, in 2012, the Supreme Court of Argentina considered the Concluding Observations of the CCPR and the CRC Committee in the landmark F., A. L. s/ Medida Autosatisfactiva case on legal abortion.Footnote 66

For all these reasons, Concluding Observations constitute a good subject of analysis. At the same time, it should be recognized that focusing on these documents also presents certain shortcomings – for instance, treaty bodies rarely address complex matters, such as mental health, with conceptual sophistication. In addition, because Concluding Observations emerge from a process of constructive dialogue with the State, they may be shaped by political considerations and thus avoid being overly severe or overly specific on certain issues. Lastly, there might be a degree of inconsistency among the Concluding Observations issued by different treaty bodies.

The practice: Mental health in the Concluding Observations of UN treaty bodies

Methodology and limitations

This research is based on a textual analysis of Concluding Observations conducted through the UHRI database. The database allows the examination of the various paragraphs of the Concluding Observations that express concerns or observations, or require the State to take action. Throughout this paper, the general term “recommendations” is used to refer to all such paragraphs.Footnote 67 The database organizes recommendations according to treaty body, country, human rights theme, and the persons or groups concerned. In addition, it includes a “text search” function that enables the retrieval of specific words or expressions. The UHRI database was chosen for its advanced filtering capabilities, which facilitate targeted searches.

The research aimed to identify recommendations regarding the protection of the mental health of persons affected by armed conflict within the sphere of the right to health, and to answer the following two questions:

1. Which target groups were most frequently addressed in the recommendations?

2. Which thematic issues were most frequently identified as areas of concern or as requiring action?

The data collected also made it possible to answer additional questions that help to better contextualize the analysis:

3. Which treaty bodies issued the greatest number of recommendations?

4. Which countries received the highest number of recommendations?

5. In which years were the largest numbers of recommendations issued?

The following UHRI filters were applied: Country: all countries; Mechanism: treaty bodies; Human rights themes: the right to health; and Concerned persons: persons affected by armed conflict. In the “text search” bar, the following keywords were entered: “mental health” (which also retrieved expressions such as “mental health condition(s)”); “mental healthcare”; “mental illness” (including the plural “mental illnesses”); “mental disorder” (including the plural “mental disorders”); “psychiatry”; “psychiatric”; “psychology”; “psychological”; “psychosocial”; and “intellectual” (which allowed us to look for expressions such as “psychosocial and intellectual disabilities”). It must be noted that the use of the preset UHRI filter “persons affected by armed conflict” also captured recommendations directed at countries where there is no armed conflict, but that are the destination of people fleeing war. Although these recommendations do not concern conflict or post-conflict settings, they were retained in the study because they still address the nexus between mental health and war and may be of great interest to receiving countries.

The recommendations resulting from the application of these filters underwent a preliminary screening, during which all recommendations deemed irrelevant to the analysis were excluded. The recommendations eliminated at this stage were: (a) those in which mental health-related terms were not explicitly connected to conflict/post-conflict situations; (b) those that mentioned persons with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities yet did not refer to their mental health but rather referred to other rights, such as their right to education; (c) those that welcomed State policies without expressing concern or requesting States to take action; and (d) those that referred to previous paragraphs of the Concluding Observation without adding any substantive measures.

To answer the first two questions listed above, a set of classification labels was developed following an initial reading of the material (the full list of the labels can be found in the footnotes). These labels included, for instance, “women”, “children” and “prisoners” for question 1 on target groups,Footnote 68 and “availability and accessibility of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS)”, “quality of MHPSS” and “acceptability of MHPSS” for question 2 on thematic issues.Footnote 69 Under question 1, a series of sub-classification labels was created for the two most frequently recurring target groups, namely women and children. The label “children” included sub-labels such as “child soldiers” and “children with disabilities”,Footnote 70 while “women” included “women victims of SGBV”, “pregnant women” etc.Footnote 71 A single recommendation could be associated with multiple labels.Footnote 72 To answer questions 3, 4 and 5 listed above, classification labels were not required, as the relevant data (countries concerned, recommending bodies and year of publication) came directly from the database and only needed to be analyzed.

The methodology adopted for this study presents some limitations. First, the UHRI database only includes Concluding Observations issued from 2007 onwards;Footnote 73 moreover, recommendations made by human rights mechanisms typically appear in the database six to twelve months after publication, and consequently, the analysis might not cover the most recent documents. Nonetheless, this study covers recommendations from 2008 to 2025, representing a broad temporal scope for examining such materials. Second, only recommendations employing expressions related to the semantic field of mental health were identified, and as a result, some recommendations concerning mental health, but not employing this terminology, have been omitted. To reduce this limitation, not only “mental health” but a range of related expressions were used, such as “psychological” and “psychosocial”, as described above. Third, since this study incorporates elements of thematic analysis, it inherently entails a degree of subjectivity. The process of identifying themes (i.e., the “classification labels”) and linking them to the recommendations was inevitably influenced by the researcher’s perspective.

Results

A total of 105 recommendations were identified through the application of the UHRI database filters described above. Following the exclusion of recommendations deemed not relevant, the final dataset comprised eighty-four recommendations. As of 7 November 2025, the total number of recommendations coming from treaty bodies present in the database amounted to 116,633. This indicates that the recommendations referring to mental health in relation to persons affected by armed conflict represented less than 0.1% of the total.

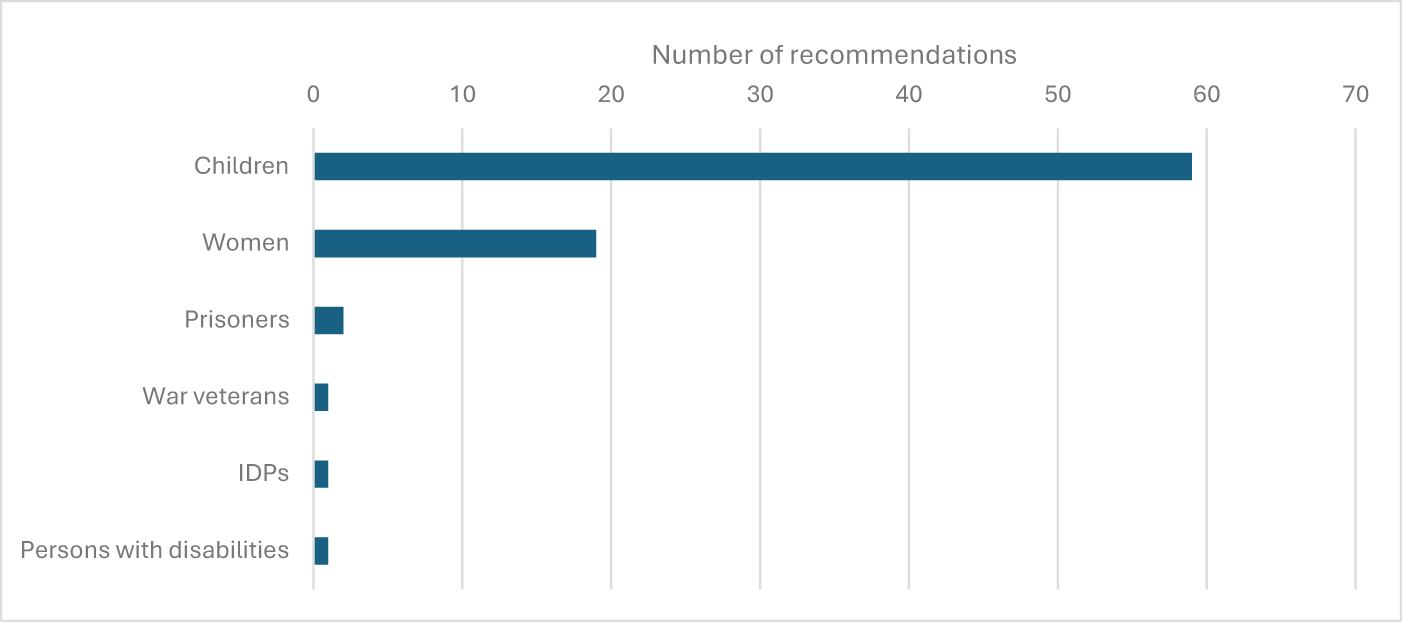

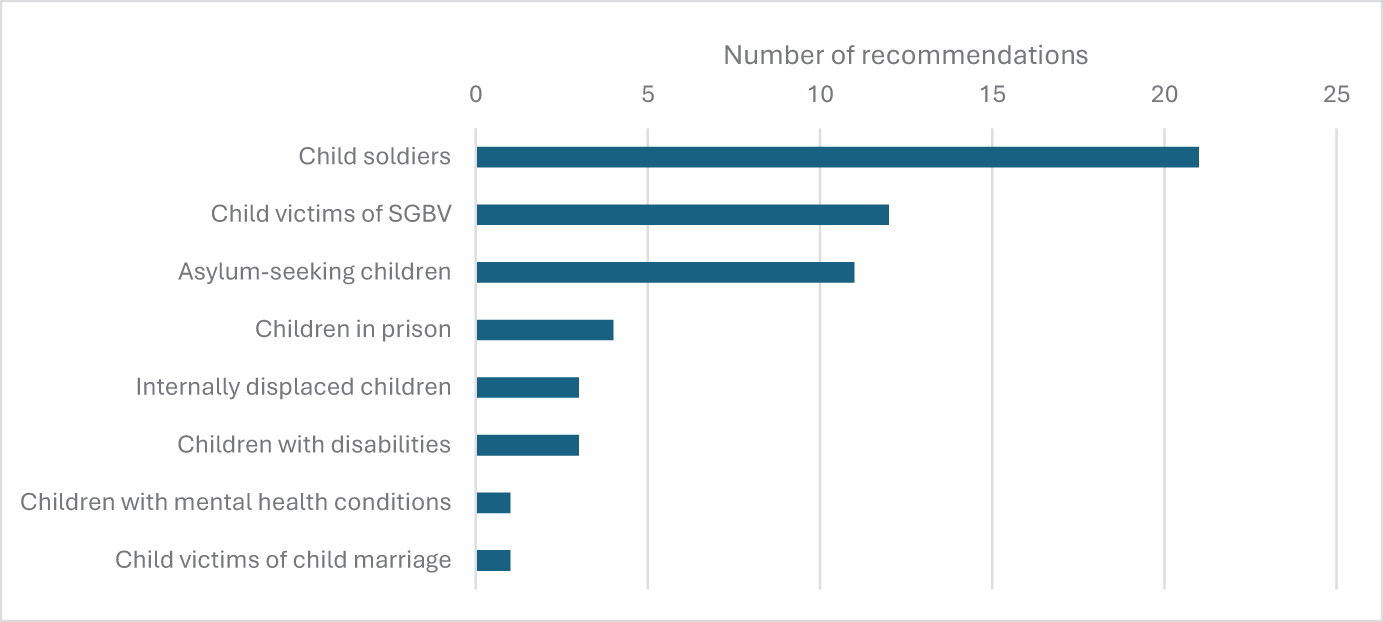

The most frequently mentioned target group was children, with nearly 70% of all recommendations (fifty-nine recommendations) dedicated to them (see Figure 1).Footnote 74 Many of these recommendations regarding children referred to specific subgroups of children in particularly vulnerable conditions (see Figure 2). Approximately one third of the recommendations concerning children mentioned child soldiers (twenty-one recommendations),Footnote 75 while other frequently cited subgroups were child victims of SGBV (twelve recommendations)Footnote 76 and asylum-seeking children (eleven recommendations).Footnote 77 The second most frequently mentioned target group was women, appearing in 22% of the recommendations (nineteen recommendations).Footnote 78 Within this group, the most common subgroup cited was women victims of SGBV (twelve recommendations).Footnote 79 Other groups, such as prisoners and war veterans, were rarely mentioned.

Figure 1. Target groups.

Figure 2. Target subgroups: Children.

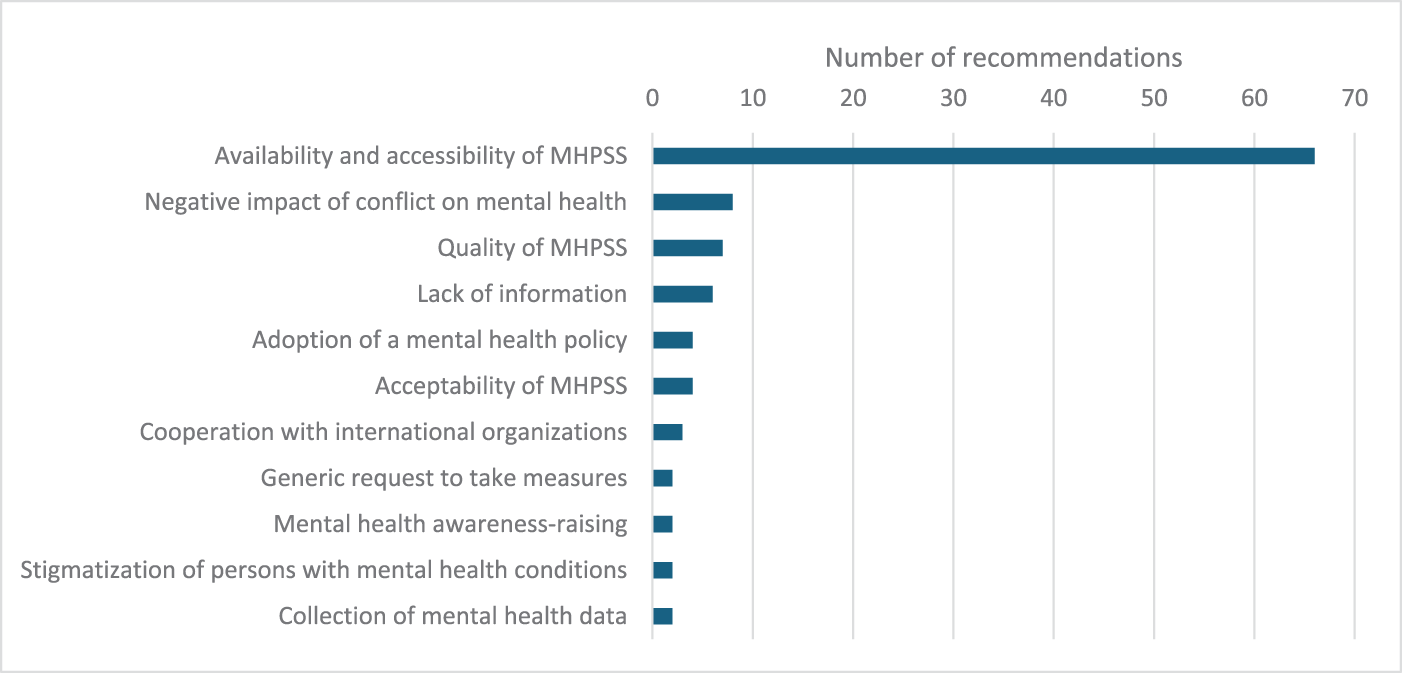

Regarding thematic issues, the most recurrent area of concern or required action was the availability and accessibility of MHPSS, which featured in almost 80% of the recommendations (sixty-six recommendations) (see Figure 3).Footnote 80 Other issues were mentioned with considerably lower frequency; among these, the most common were the recognition by treaty bodies of the negative impact of conflict on mental health (eight recommendations)Footnote 81 and the quality of mental health services (seven recommendations).Footnote 82 Additional issues raised included complaints about the lack of information on mental health provided to the treaty body,Footnote 83 the need to adopt a mental health policy,Footnote 84 and the acceptability of MHPSS.Footnote 85

Figure 3. Thematic issues.

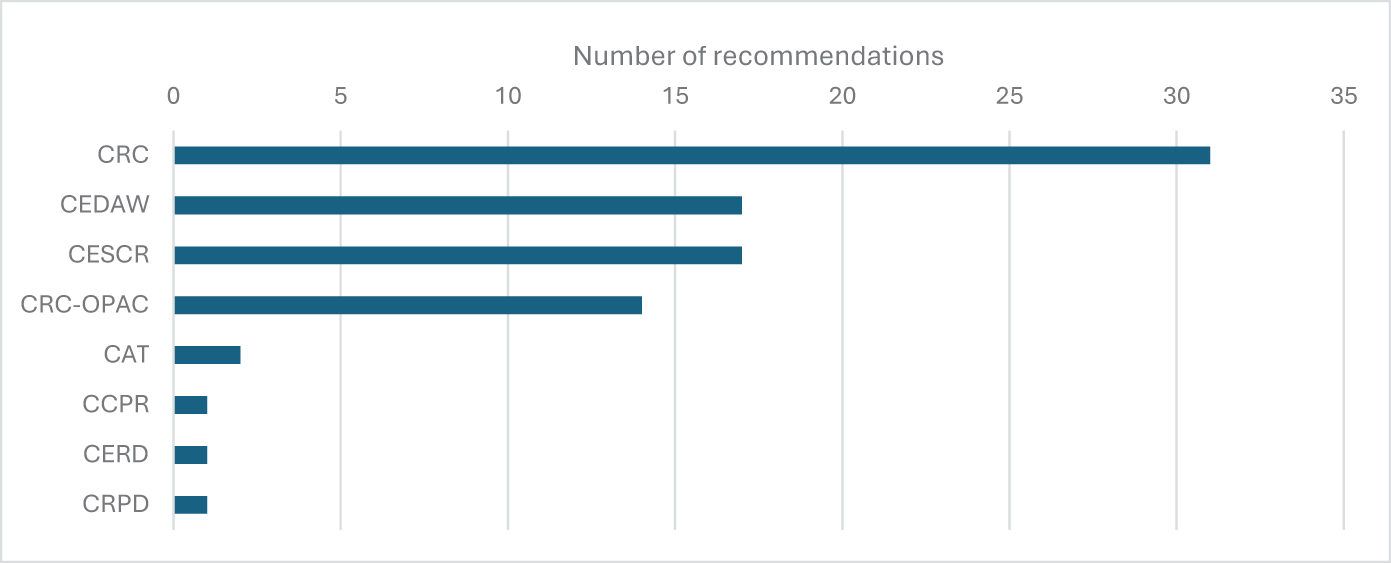

More than 50% of the recommendations were issued by the CRC Committee, which produced thirty-one recommendations under the CRC and fourteen under the Optional Protocol to the CRC on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (OPAC) (see Figure 4).Footnote 86 The CEDAW Committee and the CESCR followed, each issuing 20% of the total recommendations (seventeen recommendations each). Other committees that made occasional references to mental health in this context included the Committee against Torture (CAT, the treaty body for the Convention against Torture) (two recommendations) and the CCPR (one recommendation).

Figure 4. Recommending bodies.

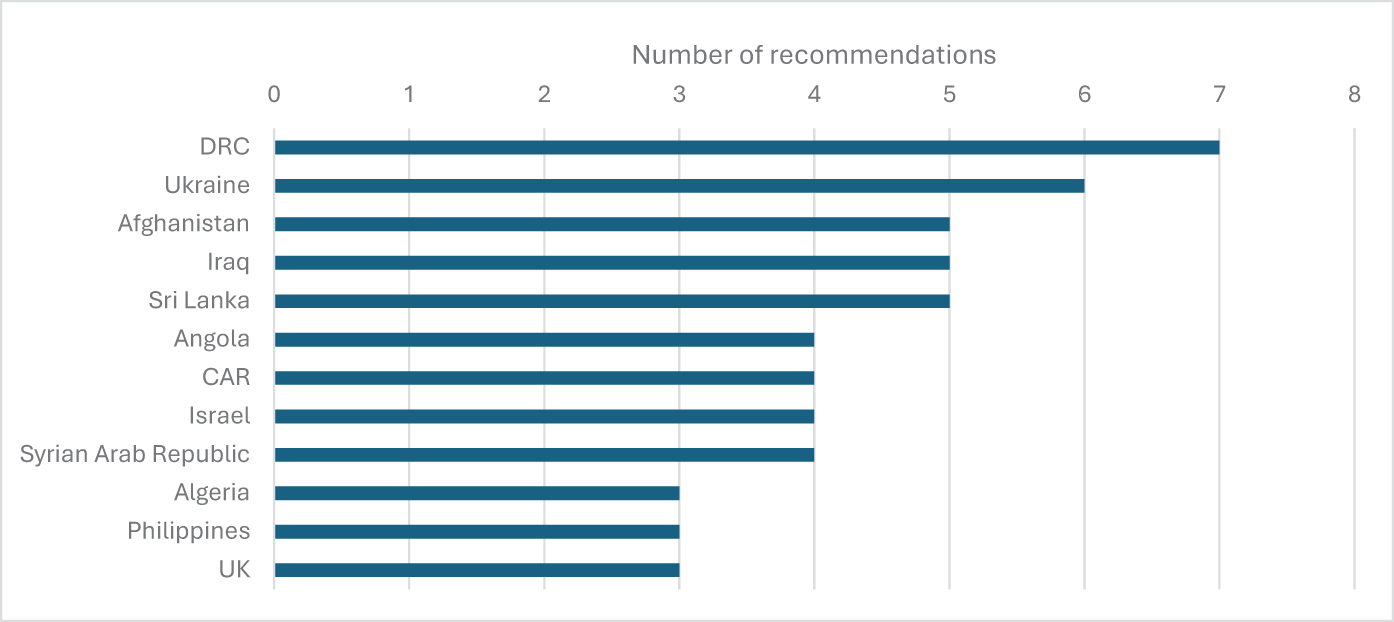

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) received the highest number of recommendations related to mental health (seven recommendations),Footnote 87 followed by Ukraine (six),Footnote 88 Afghanistan (five),Footnote 89 Iraq (five),Footnote 90 Sri Lanka (five),Footnote 91 Angola (four),Footnote 92 the Central African Republic (CAR) (four)Footnote 93 and Israel (four) (see Figure 5).Footnote 94 Several other countries received recommendations in smaller numbers, including Algeria (three),Footnote 95 the Philippines (three),Footnote 96 the United Kingdom (three),Footnote 97 Armenia (two),Footnote 98 Colombia (two),Footnote 99 Cote d’Ivoire (two),Footnote 100 Ethiopia (two),Footnote 101 Georgia (two)Footnote 102 and Nepal (two).Footnote 103 Overall, the eighty-four recommendations were addressed to thirty-four countries, covering all continents.

Figure 5. Countries concerned (first 12 out of 34).

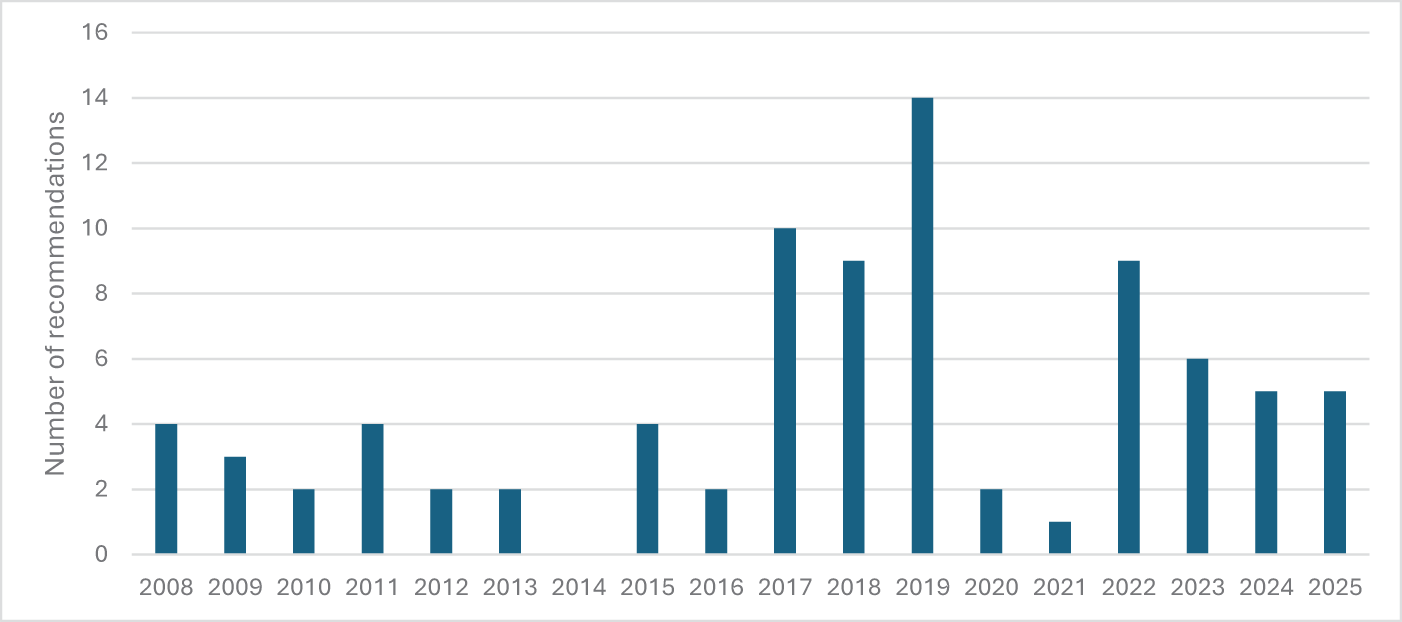

In terms of publication date, four periods can be distinguished in order to better identify trends: (a) 2008–16, (b) 2017–19, (c) 2020–21 and (d) 2022–25. The first period (2008–16) is the one with the fewest recommendations, representing 27% of the total, with an average of 2.5 recommendations per year (see Figure 6). The highest number of recommendations was issued during the second period (2017–19), accounting for 39% of the total in just three years. The number of recommendations dropped sharply in 2020–21 (to 4% of the total), before increasing again between 2022 and 2025, when almost 30% of all recommendations were issued.

Figure 6. Recommendation publication year.

Discussion

The data presented above reveal a clear predominance of recommendations dedicated to the mental health of children and women affected by conflict. These results are unsurprising and in line with studies suggesting that children and women are categories that have received “colossal attention” from treaty bodies.Footnote 104 IHRL’s attention to children is particularly well established, and the CRC remains one of the most widely ratified treaties, with 196 States Parties. Moreover, the protection of children during hostilities has been the subject of numerous international instruments and initiatives over the past three decades. Among these, it is worth recalling the creation of the mandate of the Special Representative for Children in Armed Conflict by the UN General Assembly in 1997;Footnote 105 Security Council Resolution 1261 of 1999, which identified six grave violations affecting children the most during the hostilities and requested the Secretary-General to report on them;Footnote 106 and the OPAC, adopted in 2000 and entered into force in 2002, which currently has 172 States Parties.Footnote 107

More specifically, several recommendations emphasized the need to provide MHPSS to child soldiers. The conscription and use of minors remain widespread in various conflict settings, and the consequences for their mental health are well documented.Footnote 108 Child soldiers are exposed to violence, death and sexual abuse and are coerced into perpetrating violence themselves. Similar considerations apply to child victims of SGBV, the other most prominent subgroup identified: SGBV continues to be used as a “strategic weapon of war” in several conflicts, taking a heavy toll on mental health.Footnote 109 It is also noteworthy that the recruitment and use of children as soldiers and sexual violence against children constitute two of the six grave violations identified by Security Council Resolution 1261. It can thus be argued that the “six violations” framework established by that resolution has significantly influenced the treaty bodies’ work.

Another point emerging from the analysis is the presence of recommendations concerning asylum-seeking children. These recommendations seem to reflect States’ obligations not only under Article 24 of the CRC (right to health), but also under its Article 39, which requires States Parties to take all appropriate measures to promote the physical and psychological recovery of child victims of armed conflict. As observed by Tobin and Marshall, this obligation “arises irrespective of whether a state is responsible for, involved with, or contributed to the harmful treatment experienced by a child”.Footnote 110 The presence of asylum-seeking children as a target group is particularly interesting, as the States concerned are typically the so-called “countries of destination” rather than those where the conflict occurs. This shows that States’ obligations to protect the mental health of children affected by armed conflict extend beyond the countries directly impacted by the hostilities.

The second-most frequently cited group was women, especially those who are victims of SGBV. This focus likewise reflects a significant number of international initiatives addressing sexual violence in conflict over the past thirty years. Among these, the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action makes references to the phenomenon of sexual abuse during hostilities,Footnote 111 and Security Council Resolution 1888 of 2009 establishes the Office of the Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict.Footnote 112 Since then, a report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence has been issued every year, further institutionalizing attention to this matter. Overall, the emphasis on women and children as groups whose mental health requires special protection corresponds to a high interest in the impact of conflict on these populations in the global policy agenda.

Regarding thematic issues, most recommendations concerned the availability and accessibility of MHPSS for persons affected by conflict. This focus demonstrates a strong recognition by treaty bodies of the acute need for MHPSS in conflict and post-conflict contexts. By contrast, comparatively less attention was paid to the two other elements of the AAAQ framework – that is, acceptability and quality of mental health services and facilities. The treaty bodies seem to take a pragmatic approach in this regard: they prioritize the provision of MHPSS services while giving less prominence to considerations such as their cultural appropriateness (acceptability) or the need to have properly trained staff (quality). In conflict settings, typically characterized by severe resource constraints, this emphasis on access over other elements may be understandable. Nevertheless, the cultural acceptability of MHPSS interventions should not be underestimated: the risk, especially if NGOs or international organizations provide such services, is often that a Western conception of mental health will be imposed, which could undermine the effectiveness of the interventions.

Another issue that deserves attention is that although some recommendations refer to mental health-care services or psychiatric care,Footnote 113 several others adopt a broader approach by referring to psychological and/or psychosocial support.Footnote 114 In many instances, the recommendations mention mental health and psychological/psychosocial support services together.Footnote 115 This linguistic choice reflects the awareness of treaty bodies that conflict affects the mental health of the entire population, and not only that of those who have or develop mental health conditions. Consequently, the services that the State should put in place during and after hostilities encompass not only clinical interventions aimed at treating mental health conditions (psychiatric care) but also measures to alleviate mental distress that does not necessarily reach this threshold (psychosocial and psychological support). In sum, these recommendations highlight the need for a multi-layered approach to mental health, including psychosocial support, psychological support and specialized mental health care. This finding suggests that the right to mental health entails State obligations not only in relation to treatment but also in relation to mental health prevention and promotion.

The other thematic issues identified in the recommendations also warrant discussion. In conflict settings, the shortage of financial and human resources often constitutes one of the main obstacles to implementing human rights, including the right to (mental) health. The principle of progressive realization does not, in itself, resolve the question of how to allocate resources, and for this reason, even the less frequently cited issues in the recommendations may serve as useful indicators of areas for prioritization. These issues include the quality of MHPSS services; the adoption of a mental health policy; the acceptability of MHPSS services; cooperation with international organizations providing such services; mental health awareness-raising; the fight against the stigmatization of persons with mental health conditions; and the collection of mental health data.

It is noteworthy that the recommendations did not address one essential feature of the right to (mental) health: participation. This absence was not unexpected, as participation remains one of the most neglected components of the right to health.Footnote 116 In the context of armed conflict, the operationalization of participatory processes is even more challenging. Nevertheless, designing mental health policies that respond to people’s needs, rather than adopting a top-down approach, would not only constitute respect for one key dimension of the right to health, but would also likely enhance the success of the measures. In practical terms, treaty bodies could recommend following the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, which provide useful guidance on participatory approaches.Footnote 117 For example, the Guidelines emphasize that “[t]he affected population should … be involved in defining well-being and distress”.Footnote 118 The element of accountability was likewise largely absent from the recommendations, though this omission is perhaps more understandable given that administrative, political and judicial mechanisms are often severely disrupted during conflict.

The finding that the most active treaty body was the CRC Committee is consistent with the parallel finding that the majority of the recommendations focused on children. Similar reasoning applies to the CEDAW Committee, which ranked second, as women were the second-most frequently cited target group. The finding that the CESCR issued several recommendations (it shared the second position with the CEDAW Committee) is coherent with previous work by Schmid, who has underlined that mental health has become one of the key substantive areas of attention in the CESCR’s consideration of conflict-related issues.Footnote 119 In contrast, treaty bodies associated with the civil and political rights sphere, such as the CCPR, have rarely issued recommendations on mental health. This finding demonstrates that mental health continues (understandably) to be conceptualized predominantly within the framework of socio-economic rights.

The analysis of countries addressed by the recommendations shows, as expected, that the highest numbers of recommendations were directed to States involved in situations of international or non-international armed conflict, such as the DRC, Ukraine, Afghanistan and Iraq. However, more than thirty different countries in total were addressed by the recommendations, showing that an interest in the protection of the mental health of persons affected by conflict is not limited to certain geographical regions or particular conflicts. Moreover, as anticipated above, not all countries receiving the recommendations were countries impacted by conflict – some were countries of destination, where persons affected by hostilities seek asylum.

Finally, the temporal distribution of the recommendations reveals a net increase in attention to the topic between 2015 and 2019. One possible explanation is that during this period, the UN Special Rapporteur for the Right to Health was Dainius Pūras (2014–20), a professor of child psychiatry and public mental health who dedicated significant consideration to the protection of the right to mental health. Pūras advocated against overmedicalization and gave prominence to mental health prevention and promotion,Footnote 120 and it is plausible that his reports informed and inspired the treaty bodies’ work.

Conversely, the sharp decline in recommendations between 2020 and 2021 may be linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. During those years, the mental health needs of persons affected by conflict may have been overshadowed by other right-to-health concerns, such as access to vaccines. In addition, fewer Concluding Observations were issued in that period due to the deferral of sessions and the holding of sessions online. It is also worth mentioning that, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, UN Human Rights is undergoing a significant financial crisis that is impacting the work of the treaty bodies.Footnote 121 By way of illustration, in 2025, six treaty bodies had to cancel one of their annual sessions, leading to the postponement of several State Party reviews and related Concluding Observations.Footnote 122

Conclusions

I went onstage to check how things were going and was stunned to see how many young people managed to come even though they had to evade mortar and sniper fire coming from the surrounding hills. The hunger for a normal life prevailed. So many people were ready to risk their lives for two hours of any music whatsoever.Footnote 123

With these words, Nebojša Šerić Šoba, another member of the rock band Sikter, described one of the band’s concerts in besieged Sarajevo. His reflection reminds us that our minds need nourishment and protection just as much as our bodies do.

IHRL recognizes the importance of mental health through the corresponding human right: the right to mental health. The main features of this right include the requirements that mental health services, goods and facilities be available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality; its subjection to the principle of progressive realization; and the participation of the population in the development of mental health policies. Since IHRL continues to apply in situations of armed conflict, the right to mental health remains relevant even in such contexts. Although this right cannot be implemented during hostilities in the same way as in peacetime, IHRL nonetheless requires States to take concrete steps towards its realization even in conflict settings.

To better understand State obligations under the right to mental health in situations of armed conflict, this paper has examined how UN treaty bodies have addressed this right in their Concluding Observations. The findings reveal that the vast majority of the recommendations concerned children, especially child soldiers, and women, especially those who are victims of SGBV. These results reflect the strong focus on the impact of conflict on these two groups in the broader global policy framework. Relevant initiatives in this context include the establishment of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children in Armed Conflict and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Notably, various recommendations also addressed child victims of armed conflict seeking asylum, demonstrating that even countries of destination bear obligations to promote the psychological recovery of these children.

In terms of thematic issues, treaty bodies concentrated primarily on the need to provide MHPSS to persons affected by conflict. Recommendations commonly referred to both psychiatric care and psychological/psychosocial support, revealing an awareness of the importance of addressing mental health at multiple levels. Other issues mentioned included the quality and acceptability of MHPSS, the adoption of a national mental health policy and the collection of mental health data. One aspect that might have warranted greater attention is participation; in conflict settings, developing mental health policies through bottom-up approaches not only constitutes respect for the right to mental health but also likely enhances the effectiveness of interventions.

Directions for future action flowing from this study’s findings include the following:

• For States: States should continue submitting reports to treaty bodies, as Concluding Observations have proven to be a valuable tool for clarifying human rights obligations and identifying areas of concern. Adequate funding for treaty bodies is also essential, given that current budgetary constraints are significantly affecting their work. As far as the right to mental health is concerned, States should be aware that they should take concrete steps towards its realization even in situations of armed conflict. While implementing this right during hostilities can be particularly challenging, some measures do not require substantial resources, such as collaborating with international organizations that provide MHPSS services.

• For treaty bodies: Treaty bodies should keep addressing the mental health of persons affected by armed conflict in their Concluding Observations, given the growing societal and political importance of mental health and the well-documented adverse effects of hostilities on the mental health of populations. They should be as specific as possible in their recommendations and avoid generic requests to “take measures”. With respect to thematic issues, they could pay more attention to the importance of participatory models in developing mental health policies. Furthermore, the CRC Committee, CEDAW Committee and CESCR – the treaty bodies that issued the majority of recommendations on mental health issues – could coordinate to develop a common approach on mental health. Providing States with consistent feedback on priority areas could enhance the overall impact of the recommendations.

Through its empirical analysis, this paper hopes to support States in implementing their obligations towards the mental health of persons affected by armed conflict, demonstrating how an abstract human right can be translated into more practical and concrete steps. This study may also serve as a useful resource for treaty bodies, increasing awareness of how they have addressed mental health in situations of armed conflict to date and identifying areas for potential improvement. The insights provided by this paper may inform the drafting not only of future Concluding Observations but also of future General Comments. For instance, this analysis could provide valuable input for the drafting process of the CESCR’s new General Comment on the application of the ICESCR in situations of armed conflict.Footnote 124

The issues explored in this study are particularly relevant today and will likely remain so in the years to come, as modern warfare tactics, like cyber-attacks and psychological warfare, and potential future military developments, such as the use of neurotechnologies, continue to have a profound effect on mental healthFootnote 125 – indeed, it has unsurprisingly been claimed that “[t]he human brain is the battlefield of the 21st century”.Footnote 126 Future research could examine whether, and to what extent, the Concluding Observations analyzed in this study have had a tangible impact on the countries concerned. It could also explore what participatory approaches have proven particularly effective in situations of armed conflict.

All of this being said, the importance of providing MHPSS in conflict and post-conflict contexts should not obscure the social and political factors that give rise to mental distress in the first place. For instance, it has been observed that there is “a tendency to depict all Palestinians as traumatized and suffering from mental health issues while simultaneously disregarding the context that creates these mental health issues”.Footnote 127 For this reason, it remains of the utmost importance not to decontextualize mental distress, and above all, to ask those affected by armed conflict what their needs are.