At the direction of the president, the U.S. military has initiated a coordinated campaign against alleged narcotics trafficking vessels in international waters in the southern Caribbean Sea and the eastern Pacific Ocean, targeting and destroying speedboats and submarines and killing nearly all of their crew.Footnote 1 The vessels, according to the administration, were affiliated with drug cartels that had been designated by the United States as foreign terrorist organizations.Footnote 2 In notices sent to Congress, the administration stated that the United States is engaged in an “non-international armed conflict” with unnamed cartels,Footnote 3 that the cartels are “non-state armed groups,”Footnote 4 that the alleged drug smugglers, also unnamed, are “unlawful combatants,”Footnote 5 that the cartels’ narcotics trafficking “constitute[s] an armed attack against the United States,”Footnote 6 that the United States is “conduct[ing] operations against [the cartels] pursuant to the law of armed conflict,”Footnote 7 and that the United States’ use of force against the cartels is in “self-defense.”Footnote 8 The administration has not released details regarding the strikes aside from cursory and unverified claims, made in social media posts that announced the attacks, concerning the persons targeted, their affiliations, and their activities, as well as short, edited aerial before-and-after videos showing the vessels’ destruction. Neither has it released the Office of Legal Counsel’s opinion authorizing the operations or explained in detail their legal basis, even in confidential congressional briefings.Footnote 9 The administration’s turning of the United States’ decades-old metaphorical war on drugs into actual military action modeled on the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) rests on the deliberate blurring of the lines between crime, terrorism, and armed conflict to expand the government’s authority to use lethal force against any groups or persons the president decides to label as terrorists, pushing well beyond the limits of even the most expansive prior readings of U.S. and international law. International lawyers unconnected with the administration have overwhelmingly concluded that the United States is not engaged in an armed conflict with the cartels, that there is no legal justification for killing those on board the targeted vessels, and thus that the president and the secretary of war have ordered members of the U.S. military to commit murder.Footnote 10

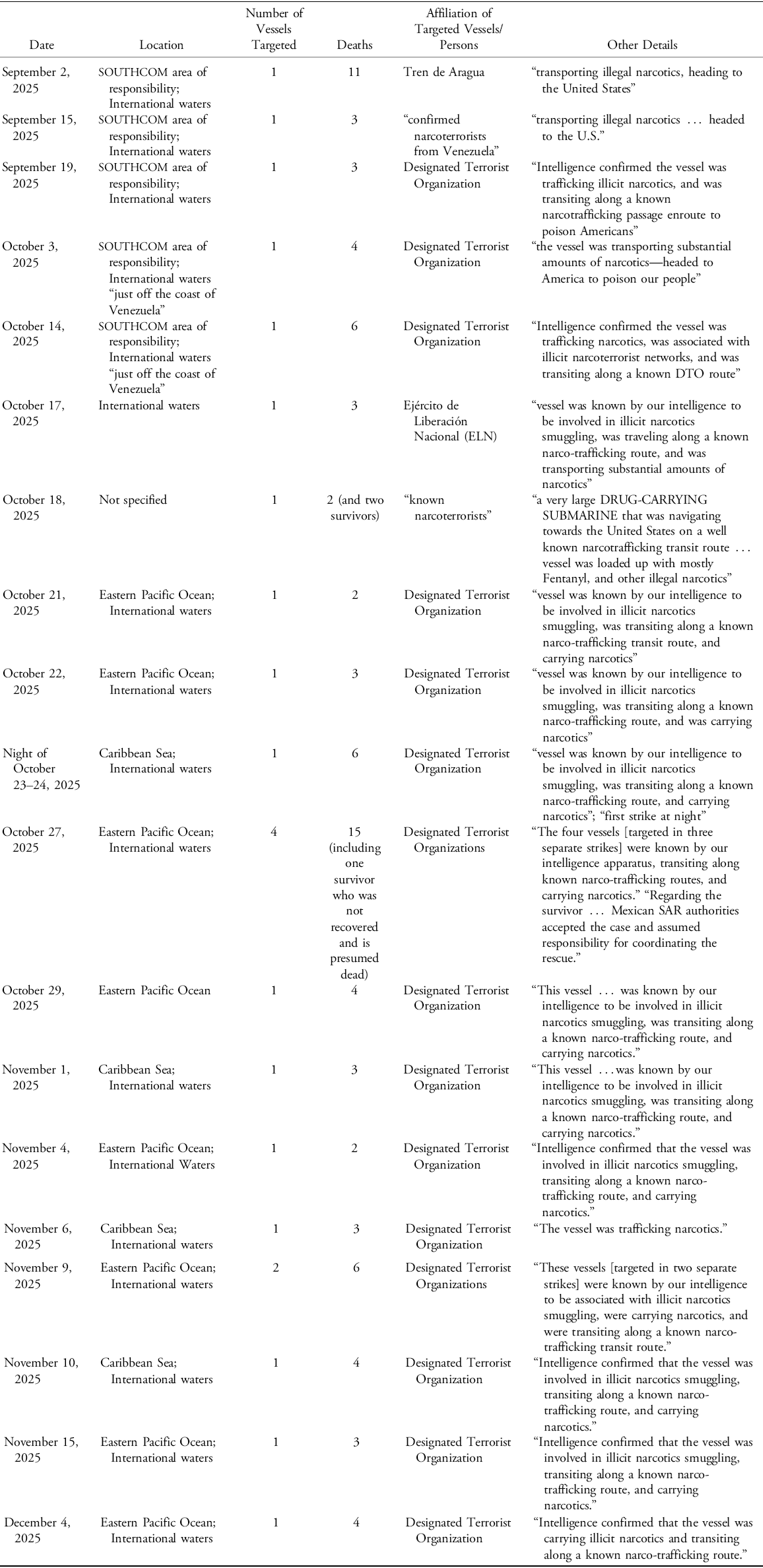

The campaign’s first strike took place on September 2, 2025, and twenty-one more have followed to date, destroying twenty-three vessels and killing eighty-seven (Table 1). Under the law enforcement model traditionally used to apprehend maritime narcotics traffickers, the Coast Guard has authority to “make inquiries, examinations, inspections, searches, seizures, and arrests upon the high seas” and U.S. waters.Footnote 11 It interdicts alleged narcotics trafficking vessels with the support of other U.S. government agencies, detaining those on board (for prosecution or repatriation) and seizing any illicit cargo, only using force, as necessary, under limited circumstances.Footnote 12 These operations continue, including in the Caribbean Sea; and the eastern Pacific Ocean; and indeed narcotics seizures this year are occurring at a record pace.Footnote 13 The law enforcement model was developed and utilized because narcotics traffickers, regardless of whether they are encountered domestically or internationally, are civilians, and thus subject to apprehension, legal process, and punishment under law like all other civilians accused of committing crimes.

TABLE 1: U.S. Military Attacks on “Narcoterrorists”.

Source: Social Media Posts of President Trump, Secretary of War Hegseth, and the U.S. Southern Command. See note 1 supra. Updated through December 4, 2025.

Over the summer, the president scrapped the law enforcement model for Latin American drug cartels designated as terrorists, secretly ordering the military to conduct lethal operations against them at sea and on land.Footnote 14 Killing is clearly the point. “I think we’re just going to kill people that are bringing drugs into our country. Okay?,” said the president.Footnote 15 “We’re going to kill them. You know? They’re going to be like, dead. Okay?”Footnote 16 “Killing cartel members who poison our fellow citizens,” Vice President JD Vance said, “is the highest and best use of our military.”Footnote 17 Secretary of State Marco Rubio explained that the move from the law enforcement paradigm to a military one was necessary because the existing method was ineffective: “The United States has long … established intelligence that allow us to interdict and stop drug boats, and we did that. And it doesn’t work…. What will stop them is when you blow them up, when you get rid of them…. [T]he President … is going to wage war on narcoterrorist organizations.”Footnote 18 The contention that lethality is a more effective method of preventing the influx of narcotics has been maintained by others in the administration as well.

Efficiency is not a justification for killing, however. The summary, extrajudicial killing of civilians, including alleged narcotics traffickers, by the U.S. military would constitute murder and possibly war crimes, as well as violate the right to life, under U.S. and/or international law.Footnote 19 While the administration has not disclosed its legal rationale in full, its application of the military model to drug cartels is clearly and conspicuously premised on the claim that the war against drugs is analogous to the GWOT. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth has made this clear: “These DTOs [designated terrorist organizations] are the ‘Al Qaeda’ of our hemisphere.”Footnote 20 Addressing drug cartel members, he warned: “we will treat you like we treat Al-Qaeda. Day or NIGHT, we will map your networks, track your people, hunt you down, and kill you.”Footnote 21 Other administration officials have drawn the same parallels. But the government’s designation of a group as a terrorist organization is not itself a justification for the use of force against that group under any applicable law, so there needs to be some other grounds for the asserted lawfulness of the targeted killings that the United States has undertaken.

The administration has premised the legality of its militarization of counternarcotics operations on the “unwilling or unable” doctrine that the United States developed to justify its use of force against terrorists engaged in an armed conflict against the United States who were located in other states. In his War Powers Resolution letter to Congress following the first strike, the president wrote that “[e]xtraordinarily violent drug trafficking cartels … have wrought devastating consequences on American communities for decades, causing the deaths of tens of thousands … and threatening our national security and foreign policy interests.”Footnote 22 Attempts, he said, have been made to combat the groups by “[f]riendly foreign nations,” but nonetheless the organizations “are now transnational and operate throughout the Western Hemisphere.”Footnote 23 Consequently, “[i]n the face of the inability or unwillingness of some states in the region to address the continuing threat to United States persons and interests emanating from their territories, we have now reached a critical point where we must meet this threat to our citizens and our most vital national interests with United States military force in self-defense.”Footnote 24 In a statement to the Security Council, the U.S. representative said that the operations against the cartels were “consistent with Article 51 of the UN Charter.”Footnote 25

Leaving aside whether self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter can be taken against non-state actors (or whether the cartels’ actions can be attributable to a state), that provision requires the existence of an “armed attack” by the cartels and that the acts of self-defense undertaken by the United States in response are necessary and proportionate. An “armed attack,” even under the low standard articulated by the United States, requires at least a “use of force,”Footnote 26 and a use of force “typically denote[s] physically coercive actions by military means.”Footnote 27 Despite the harms caused by the use of narcotics that are trafficked into the country, no cartel is engaged in such actions, imminent or actual, against the United States. That conclusion is even stronger for those that contend that there is a heightened threshold for an armed attack. The standard could not be met even if a cartel’s drug shipments could be aggregated. Neither is the U.S. military response necessary and proportionate. Less forcible measures could have been used to counter the targeted boats.

Beyond these hurdles to a theory of self-defense, the administration’s invocation of the “unwilling or unable” doctrine is simply not pertinent to the current operations, as the doctrine’s purpose is to justify the taking of military action in the territory of another state, not in areas, like international waters,Footnote 28 that are not controlled by a state.Footnote 29 The president’s letter to Congress refers to the inability or unwillingness of “some states in the region to address the continuing threat … emanating from their territories.”Footnote 30 But that assertion goes to the United States’ felt need to take action against narcotics traffickers and is not relevant to its legal justification for lethal strikes that take place outside the territory of those states, or indeed any state. Perhaps, though, the “unwilling or unable” line of argument in the president’s message is meant to provide support for contemplated future land-based actions in the territories of states, like Venezuela and Colombia, that are not, according to the United States, sufficiently combatting “narcoterrorists.” If so, that argument is a not-so-subtle warning and threat directed at those states, and it may portend possible future U.S. military action against them, as will be noted below.

To justify its lethal measures, the administration has claimed that the United States is involved in a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) with certain “designated terrorist organizations.”Footnote 31 The existence of an armed conflict would not establish the lawfulness of the resort to the use of force itself, but it would result in the applicability of the law of armed conflict to the hostilities and, thus, authorize the killing of combatants during the hostilities, within the bounds of that law.

The existence of a NIAC is highly contestable. The Department of Defense’s Law of War Manual notes that “[t]he intensity of the conflict and the organization of the parties are criteria that have been assessed to distinguish between non-international armed conflict and ‘internal disturbances and tensions.’”Footnote 32 According to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, a NIAC involves “protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups.”Footnote 33 Though the cartels may be organized in some respects, it is unclear whether they are, individually or collectively, an “organized armed group.” A declassified National Intelligence Council assessment from April stated that Tren de Aragua, one of the designated terrorist organizations, “operat[es] in loosely-organized cells of localized, individual criminal networks” and is “decentralized.”Footnote 34 It is also far from evident, and seems even less likely, that the intensity of the “armed conflict,” at present, is sufficient. The administration’s notification to Congress “base[d]” its conclusion that the United States is in a NIAC with “designated terrorist organizations” on “the cumulative effects of [their] hostile acts against the citizens and interests of [the] United States and friendly foreign nations.”Footnote 35 At the Security Council, the U.S. delegate stated that “[t]he cartels carrying out this assault against our citizens [referring to the ‘flooding of American streets with their product and killing Americans’] are armed, well organized, and violent. They have financial means, technical sophistication, and extensive paramilitary capabilities.”Footnote 36

Even if there is an armed conflict with “designated terrorist organizations,” lethal force could only be directed at the civilians operating the targeted speedboats while they were directly participating in hostilities or have effectively become members of the armed group by serving in a “continuous combat function.”Footnote 37 The idea that low-level drug traffickers (if that is who they are) are combatants involved in hostilities against the United States is far-fetched. In a congressional briefing, Pentagon officials said, incredibly, that “they needed to prove only that the targeted people were connected to designated terrorist organizations, even if the connection is ‘as much as three hops away from a known member” of a designated terrorist organization.’”Footnote 38 If there is no armed conflict, or if the traffickers are not combatants, then domestic law and international human rights law apply, which would preclude the use of lethal force except in circumstances of self-defense while engaging those persons.

Unlike the GWOT, Congress has not authorized the use of force against the drug cartels. The administration notified Congress that the “President directed these actions consistent with his responsibility to protect Americans and United States interests abroad and in furtherance of United States national security and foreign policy interests, pursuant to his constitutional authority as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive to conduct foreign relations.”Footnote 39 In the past, the executive branch has articulated a very expansive theory of the president’s inherent constitutional authority to “direct the use of force” without congressional authorization if “such use of force was in the national interest.”Footnote 40 The chief Pentagon spokesman said that the Defense Department was “successfully prosecuting this critical mission in compliance with both domestic and international law, and in accordance with the law of armed conflict.”Footnote 41 “The department has provided the required notifications to Congress,” he continued.Footnote 42 Though, following the first strike, the president provided a notice to Congress to “keep [it] fully informed, consistent with the War Powers Resolution,”Footnote 43 as the resolution’s sixty-day window for congressional authorization began to close, the administration told Congress that the resolution in fact did not apply because “the kinetic operations underway do not rise to the level of ‘hostilities.’”Footnote 44

Congress has conducted no hearings to date. Some Democratic members have criticized the administration for not disclosing the legal basis for the strikes.Footnote 45 And some have objected to the use of force.Footnote 46 Senator Jack Reed of Rhode Island decried the president’s assertion that he could wage “secret wars against anyone he calls an enemy.”Footnote 47 “Drug cartels are despicable,” he continued, but they “must be dealt with by law enforcement.”Footnote 48 On the Republican side, Senator Rand Paul was one of the very few who took exception to the strikes, calling them “extrajudicial killings.”Footnote 49 In early October, the Senate, by a partisan vote of 48–51, rejected a war powers resolution introduced by Senators Tim Kaine and Adam Schiff that would have terminated the administration’s military campaign.Footnote 50

There have been reports that questions have been raised in the Pentagon about the legal basis of the attacks. Admiral Alvin Holsey, head of the Southern Command, which conducts the operations, resigned in October only one year into his command, and anonymous former and current officials said that the admiral had “raised concerns about the mission and the attacks on the alleged drug boats.”Footnote 51 The chief Pentagon spokesperson denied this.Footnote 52 There is reason to doubt whether attorneys at the Pentagon and elsewhere in the government feel free to provide advice that does not align with the views of the president and his appointees. Those who did question the attacks’ legality were reportedly “steamrolled or sidestepped.”Footnote 53 A February executive order provided that the “President and the Attorney General’s opinions on questions of law are controlling on all employees in the conduct of their official duties.”Footnote 54 Thus, the president’s determinations that there has been “an armed attack against the United States” and that there is an “armed conflict” with the cartels are conclusive within the executive branch and serve as the basis for the administration’s legal justification.Footnote 55 Secretary Hegseth’s emphasis on “lethality,” his firing of the judge advocates general of the Army and the Air Force early in the administration, and his strong disdain for legal restrictions suggest that considerations of the law, as traditionally understood by Defense Department attorneys, both civilian and uniformed, are not being given priority.Footnote 56

The strikes have been widely condemned. Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, has called the strikes a “heinous crime” and “a military attack on civilians who were not at war and were not militarily threatening any country.”Footnote 57 During a Security Council meeting, the Venezuelan representative said: “This is not self-defence—these are extrajudicial killings.”Footnote 58 President Gustavo Petro of Colombia wrote on his social media account that “U.S. government officials have committed murder and violated our sovereignty in territorial waters.”Footnote 59 Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said that “[w]e do not agree with these attacks, with how they are carried out…. We want all international treaties to be complied with.”Footnote 60 At the Security Council, the Chinese representative “stressed that unilateral and excessive enforcement operations against other countries’ vessels ‘infringe on relevant personnel’s right to life and other basic human rights’ and ‘pose a threat to freedom and security of navigation.’”Footnote 61 UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk said that the U.S. actions violated international human rights law.Footnote 62 He called on the United States to “halt such attacks and take all measures necessary to prevent the extrajudicial killing of people aboard these boats, whatever the criminal conduct alleged against them.”Footnote 63 He continued: “countering the serious issue of illicit trafficking of drugs across international borders is—as has long been agreed among States—a law-enforcement matter, governed by the careful limits on lethal force set out in international human rights law…. Under international human rights law, the intentional use of lethal force is only permissible as a last resort against individuals who pose an imminent threat to life.”Footnote 64 French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot said that “[w]e have observed with concern the military operations in the Caribbean region, because they violate international law.”Footnote 65 Kaja Kallas, the European Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, commented that the strikes had no legal justification.Footnote 66 A number of states have suspended intelligence sharing with the United States in connection with the operations due to concerns regarding their legality.Footnote 67

Though the administration argues that its military campaign will deter narcotics trafficking, it will, in fact, have no material effect on curtailing the nation’s drug overdose problem, which the administration claims is the impetus for its actions. Fentanyl, the primary cause of narcotics-related deaths in the United States, principally enters the country from Mexico across the southern border, and its precursors are sourced in China.Footnote 68 The vessels targeted in the Caribbean mostly carry Colombian cocaine (transited through Venezuela) that is destined for Europe, not the United States; the main cocaine supply chain to the United States runs instead northward by sea from Colombia’s Pacific coast and into the country through Mexico.Footnote 69 Even if, as is now asserted by the administration, the military’s attacks on narcotics trafficking boats have successfully shut down these maritime routes, the cartels will find other ways to get their products to their U.S. customers.Footnote 70 This suggests that the campaign has other motivations.

The U.S. military’s significantly enhanced posture in the Caribbean,Footnote 71 together with the leaked presidential authorization of covert action against VenezuelaFootnote 72 and the shutting down of diplomacy,Footnote 73 indicate that toppling the regime of Nicolás Maduro, who was indicted in 2020 for narcotics trafficking and other crimesFootnote 74 and has long been an antagonist of the United States and particularly the president,Footnote 75 may be another, and perhaps the main, aim of the counternarcotics operations. On the administration’s logic, the “unwilling or unable” doctrine would justify military attacks on Venezuelan (and perhaps Colombian) territory and toppling the Venezuelan government. The president’s press secretary has called Maduro’s government “a narco-terror cartel.”Footnote 76 The president, in his invocation of the Alien Enemies Act, claimed that Maduro “leads the regime-sponsored enterprise Cártel de los Soles,” since sanctioned as a specially designated global terrorist organization and a foreign terrorist organization,Footnote 77 and described Venezuela as a “hybrid criminal state.”Footnote 78 Secretary Rubio has sought Maduro’s ouster for years.Footnote 79 The administration has doubled the reward for Maduro’s arrest to $50 million.Footnote 80 Regime change is openly advocated, and the president has acknowledged that land operations are under consideration.Footnote 81 Targets have reportedly been chosen.Footnote 82 At least for now, neither the threat of U.S. military action nor a reported offer for a peaceful retirement in a third country has induced Maduro to step aside.Footnote 83