1 Introduction

1.1 Definition of the groups

We denote by

![]() $\Sigma _{g,1}$

the orientable surface of genus g with one boundary component, and by

$\Sigma _{g,1}$

the orientable surface of genus g with one boundary component, and by

![]() $\Gamma _{g,1}=\pi _0(\operatorname {Diff}_{\partial }(\Sigma _{g,1}))$

its mapping class group, defined to be the group of isotopy classes of diffeomorphisms of

$\Gamma _{g,1}=\pi _0(\operatorname {Diff}_{\partial }(\Sigma _{g,1}))$

its mapping class group, defined to be the group of isotopy classes of diffeomorphisms of

![]() $\Sigma _{g,1}$

fixing pointwise a neighbourhood of its boundary. We will define the spin mapping class groups using the approach of [Reference Harer8], which is based on the notion of quadratic refinements.

$\Sigma _{g,1}$

fixing pointwise a neighbourhood of its boundary. We will define the spin mapping class groups using the approach of [Reference Harer8], which is based on the notion of quadratic refinements.

Given an integer-valued skew-symmetric bilinear form

![]() $(M,\lambda )$

on a finitely generated free

$(M,\lambda )$

on a finitely generated free

![]() $\mathbb {Z}$

-module, a quadratic refinement is a function

$\mathbb {Z}$

-module, a quadratic refinement is a function

![]() $q: M \rightarrow \mathbb {Z}/2$

such that

$q: M \rightarrow \mathbb {Z}/2$

such that

![]() $q(x+y) \equiv q(x)+q(y)+ \lambda (x,y) (\mod 2)$

for all

$q(x+y) \equiv q(x)+q(y)+ \lambda (x,y) (\mod 2)$

for all

![]() $x,y \in M$

. There are

$x,y \in M$

. There are

![]() $2^{\operatorname {rk}(M)}$

quadratic refinements since a quadratic refinement is uniquely determined by its values on a basis of M, and any set of values is possible.

$2^{\operatorname {rk}(M)}$

quadratic refinements since a quadratic refinement is uniquely determined by its values on a basis of M, and any set of values is possible.

The set of quadratic refinements of

![]() $(H_1(\Sigma _{g,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot )$

has a right

$(H_1(\Sigma _{g,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot )$

has a right

![]() $\Gamma _{g,1}$

-action by precomposition. By [Reference Johnson9, Corollary 2] this action has precisely two orbits for

$\Gamma _{g,1}$

-action by precomposition. By [Reference Johnson9, Corollary 2] this action has precisely two orbits for

![]() $g \geq 1$

, distinguished by the Arf invariant, which is a

$g \geq 1$

, distinguished by the Arf invariant, which is a

![]() $\mathbb {Z}/2$

-valued function on the set of quadratic refinements, see Definition 6.1. For

$\mathbb {Z}/2$

-valued function on the set of quadratic refinements, see Definition 6.1. For

![]() $\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we will denote by

$\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we will denote by

![]() $\Gamma _{g,1}^{1/2}[\epsilon ]:= \operatorname {Stab}_{\Gamma _{g,1}}(q)$

where q is a choice of quadratic refinement of Arf invariant

$\Gamma _{g,1}^{1/2}[\epsilon ]:= \operatorname {Stab}_{\Gamma _{g,1}}(q)$

where q is a choice of quadratic refinement of Arf invariant

![]() $\epsilon $

, and call this the spin mapping class group in genus g and Arf invariant

$\epsilon $

, and call this the spin mapping class group in genus g and Arf invariant

![]() $\epsilon $

. These groups are of importance as their classifying spaces are the moduli spaces of spin surfaces with one boundary component by [Reference Randal-Williams17, Section 2] defined in geometric terms using tangential structures. In particular, the study of their (co)homology is the study of characteristic classes of the corresponding type of bundles. (As an aside note let us mention that notation

$\epsilon $

. These groups are of importance as their classifying spaces are the moduli spaces of spin surfaces with one boundary component by [Reference Randal-Williams17, Section 2] defined in geometric terms using tangential structures. In particular, the study of their (co)homology is the study of characteristic classes of the corresponding type of bundles. (As an aside note let us mention that notation

![]() $\Gamma ^{1/2}$

to denote spin mapping class groups comes from the geometric idea that a spin tangential structure is essentially a choice of a square root for the tangent bundle.)

$\Gamma ^{1/2}$

to denote spin mapping class groups comes from the geometric idea that a spin tangential structure is essentially a choice of a square root for the tangent bundle.)

Similarly, for

![]() $g \geq 1$

the group

$g \geq 1$

the group

![]() $Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})$

acts on the set of quadratic refinements of the standard symplectic form

$Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})$

acts on the set of quadratic refinements of the standard symplectic form

![]() $(\mathbb {Z}^{2g},\Omega _g)$

with precisely two orbits, also distinguished by the Arf invariant. Thus, for

$(\mathbb {Z}^{2g},\Omega _g)$

with precisely two orbits, also distinguished by the Arf invariant. Thus, for

![]() $\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we can define the quadratic symplectic group in genus g and Arf invariant

$\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we can define the quadratic symplectic group in genus g and Arf invariant

![]() $\epsilon $

to be

$\epsilon $

to be

![]() $Sp_{2g}^{\epsilon }(\mathbb {Z}):= \operatorname {Stab}_{Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})}(q)$

for a fixed quadratic refinement q of Arf invariant

$Sp_{2g}^{\epsilon }(\mathbb {Z}):= \operatorname {Stab}_{Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})}(q)$

for a fixed quadratic refinement q of Arf invariant

![]() $\epsilon $

. The groups

$\epsilon $

. The groups

![]() $Sp_{2g}^{0}(\mathbb {Z})$

have appeared in the literature under the name of theta subgroups of the symplectic groups, and sometimes are denoted by

$Sp_{2g}^{0}(\mathbb {Z})$

have appeared in the literature under the name of theta subgroups of the symplectic groups, and sometimes are denoted by

![]() $Sp_{2g}^{q}(\mathbb {Z})$

, and they are of importance in number theory, see [Reference Lu15] for example. These groups are also relevant in the study of manifolds, as in [Reference Kupers and Randal-Williams14, Section 4], since they represent automorphisms of homology groups of manifolds that can be realized by automorphisms of the manifolds. The groups

$Sp_{2g}^{q}(\mathbb {Z})$

, and they are of importance in number theory, see [Reference Lu15] for example. These groups are also relevant in the study of manifolds, as in [Reference Kupers and Randal-Williams14, Section 4], since they represent automorphisms of homology groups of manifolds that can be realized by automorphisms of the manifolds. The groups

![]() $Sp_{2g}^{1}(\mathbb {Z})$

are less common but have appeared recently in the study of manifolds in [Reference Kupers and Randal-Williams14, Section 4], where they are denoted by

$Sp_{2g}^{1}(\mathbb {Z})$

are less common but have appeared recently in the study of manifolds in [Reference Kupers and Randal-Williams14, Section 4], where they are denoted by

![]() $Sp_{2g}^{a}(\mathbb {Z})$

. However, as we will see in Section 5.1, one of the novelties of this paper is the idea that even if one is only interested in studying the groups

$Sp_{2g}^{a}(\mathbb {Z})$

. However, as we will see in Section 5.1, one of the novelties of this paper is the idea that even if one is only interested in studying the groups

![]() $Sp_{2g}^0(\mathbb {Z})$

one should also introduce the other family,

$Sp_{2g}^0(\mathbb {Z})$

one should also introduce the other family,

![]() $Sp_{2g}^1(\mathbb {Z})$

, and study both simultaneously.

$Sp_{2g}^1(\mathbb {Z})$

, and study both simultaneously.

1.2 Statement of results

Before stating the results let us recall what stabilization maps mean in this context. We begin by fixing quadratic refinements

![]() $q_0,q_1$

of

$q_0,q_1$

of

![]() $(H_1(\Sigma _{1,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^2,\Omega _1)$

of Arf invariants

$(H_1(\Sigma _{1,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^2,\Omega _1)$

of Arf invariants

![]() $0,1$

respectively. Then, given any quadratic refinement q of

$0,1$

respectively. Then, given any quadratic refinement q of

![]() $(H_1(\Sigma _{g-1,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^{2(g-1)},\Omega _{g-1})$

, we get a quadratic refinement

$(H_1(\Sigma _{g-1,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^{2(g-1)},\Omega _{g-1})$

, we get a quadratic refinement

![]() $q \oplus q_{\epsilon }$

of

$q \oplus q_{\epsilon }$

of

![]() $(H_1(\Sigma _{g,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^{2g},\Omega _{g})$

. Moreover, the Arf invariant is additive, see Definition 6.1, so

$(H_1(\Sigma _{g,1};\mathbb {Z}),\cdot ) \cong (\mathbb {Z}^{2g},\Omega _{g})$

. Moreover, the Arf invariant is additive, see Definition 6.1, so

![]() $\operatorname {Arf}(q\oplus q_{\epsilon })=\operatorname {Arf}(q)+\epsilon $

.

$\operatorname {Arf}(q\oplus q_{\epsilon })=\operatorname {Arf}(q)+\epsilon $

.

Thus, using the inclusions

![]() $\Gamma _{g-1,1} \subset \Gamma _{g,1}$

and

$\Gamma _{g-1,1} \subset \Gamma _{g,1}$

and

![]() $Sp_{2(g-1)}(\mathbb {Z}) \subset Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})$

we get stabilization maps

$Sp_{2(g-1)}(\mathbb {Z}) \subset Sp_{2g}(\mathbb {Z})$

we get stabilization maps

and

The goal of this paper is to study homological stability with respect to these stabilization maps. Before moving to the results observe that additivity of the Arf invariant under direct (pointwise) sum of quadratic refinements also allows us to define products

and

which contain the stabilization maps as particular cases.

It is known since [Reference Harer8, Theorem 3.1] that spin mapping class groups satisfy homological stability in the range

![]() $d \lesssim g/4$

, that is, of the form

$d \lesssim g/4$

, that is, of the form

![]() $d \le g/4-C$

for some constant C, and their stable homology can be understood by [Reference Galatius4, Section 1]. Thus, improvements in the stability range are important as they lead to new homology computations, hence to new characteristic classes. In this direction, the previously known best bounds can be found in [Reference Randal-Williams17, Theorem 2.14], where a range of the form

$d \le g/4-C$

for some constant C, and their stable homology can be understood by [Reference Galatius4, Section 1]. Thus, improvements in the stability range are important as they lead to new homology computations, hence to new characteristic classes. In this direction, the previously known best bounds can be found in [Reference Randal-Williams17, Theorem 2.14], where a range of the form

![]() $d \lesssim 2g/5$

was shown. The first main result of this paper improves the known stability range.

$d \lesssim 2g/5$

was shown. The first main result of this paper improves the known stability range.

Theorem A. Consider the stabilization map

then:

-

(i) If

it is surjective for

it is surjective for

$2d \leq g-2$

and an isomorphism for

$2d \leq g-2$

and an isomorphism for

$2d \leq g-4$

.

$2d \leq g-4$

. -

(ii) If

it is surjective for

it is surjective for

$3d \leq 2g-4$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-4$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-7$

.

$3d \leq 2g-7$

.

Moreover, there is a homology class

![]() $\theta \in H_2(\Gamma _{4,1}^{1/2}[0];\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2})$

such that

$\theta \in H_2(\Gamma _{4,1}^{1/2}[0];\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2})$

such that

is surjective for

![]() $3d \leq 2g-5$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-5$

and an isomorphism for

![]() $3d \leq 2g-8$

.

$3d \leq 2g-8$

.

Moreover, the result with

![]() $\mathbb {Z}[1/2]$

-coefficients is optimal (up to possibly a better constant term) by Lemma 7.2, and in particular the ‘slope

$\mathbb {Z}[1/2]$

-coefficients is optimal (up to possibly a better constant term) by Lemma 7.2, and in particular the ‘slope

![]() $2/3$

’ cannot be improved as in the case of the usual mapping class groups, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6]. The last part of the theorem is an example of secondary homological stability, which means that it gives a range in which the defects of homological stability are themselves stable. By Corollary 4.4, a consequence is that the

$2/3$

’ cannot be improved as in the case of the usual mapping class groups, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6]. The last part of the theorem is an example of secondary homological stability, which means that it gives a range in which the defects of homological stability are themselves stable. By Corollary 4.4, a consequence is that the

![]() $\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology satisfies a

$\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology satisfies a

![]() $2/3$

slope stability if and only if

$2/3$

slope stability if and only if

![]() $\theta ^3$

destabilizes by

$\theta ^3$

destabilizes by

![]() $\sigma _{\epsilon }$

; and otherwise the slope

$\sigma _{\epsilon }$

; and otherwise the slope

![]() $1/2$

of part (i) would be optimal with

$1/2$

of part (i) would be optimal with

![]() $\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-coefficients, and hence integrally. We do not know which of these two alternatives holds. Finally we remark that the class

$\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-coefficients, and hence integrally. We do not know which of these two alternatives holds. Finally we remark that the class

![]() $\theta $

is not uniquely defined, see Remarks 4.3 and 4.5, but its indeterminacy is small and the statement above holds for any such choice of

$\theta $

is not uniquely defined, see Remarks 4.3 and 4.5, but its indeterminacy is small and the statement above holds for any such choice of

![]() $\theta $

.

$\theta $

.

The second main result is about homological stability of quadratic symplectic groups.

Theorem B. Consider the stabilization map

then:

-

(i) If

it is surjective for

it is surjective for

$2d \leq g-2$

and an isomorphism for

$2d \leq g-2$

and an isomorphism for

$2d \leq g-4$

.

$2d \leq g-4$

. -

(ii) If

it is surjective for

it is surjective for

$3d \leq 2g-4$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-4$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-7$

.

$3d \leq 2g-7$

.

Moreover, there is a homology class

![]() $\theta \in H_2(Sp_8^0(\mathbb {Z});\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2})$

such that

$\theta \in H_2(Sp_8^0(\mathbb {Z});\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2})$

such that

is surjective for

![]() $3d \leq 2g-5$

and an isomorphism for

$3d \leq 2g-5$

and an isomorphism for

![]() $3d \leq 2g-8$

.

$3d \leq 2g-8$

.

Some results were previously known about homological stability of quadratic symplectic groups. In particular, [Reference Friedrich3, Theorem 5.2] and [Reference Charney2] already gave a stability result of the form

![]() $d \lesssim g/2$

following different techniques. However, the improvement to

$d \lesssim g/2$

following different techniques. However, the improvement to

![]() $d \lesssim 2g/3$

in part (ii) of the above theorem is new. As before, the last part is a secondary stability result which implies that either the

$d \lesssim 2g/3$

in part (ii) of the above theorem is new. As before, the last part is a secondary stability result which implies that either the

![]() $\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology also has slope

$\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology also has slope

![]() $2/3$

stability (if

$2/3$

stability (if

![]() $\theta ^3$

destabilizes) or the optimal slope of the

$\theta ^3$

destabilizes) or the optimal slope of the

![]() $\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology is

$\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}$

-homology is

![]() $1/2$

(otherwise). The class

$1/2$

(otherwise). The class

![]() $\theta $

is again not well-defined but its indeterminacy is understood by Remarks 4.3 and 4.5.

$\theta $

is again not well-defined but its indeterminacy is understood by Remarks 4.3 and 4.5.

We will prove Theorems A and B using the technique of cellular

![]() $E_k$

-algebras developed in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5], and in particular we will follow the overall strategy of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6] where this approach is applied to homological stability of mapping class groups of surfaces. However, as we will comment below some interesting novelties appear in our case.

$E_k$

-algebras developed in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5], and in particular we will follow the overall strategy of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6] where this approach is applied to homological stability of mapping class groups of surfaces. However, as we will comment below some interesting novelties appear in our case.

The basic idea is to define

![]() $E_2$

-algebra structures on both

$E_2$

-algebra structures on both

![]() $\bigsqcup _{g,\epsilon } B \Gamma _{g,1}^{1/2}[\epsilon ]$

and

$\bigsqcup _{g,\epsilon } B \Gamma _{g,1}^{1/2}[\epsilon ]$

and

![]() $\bigsqcup _{g,\epsilon } B Sp_{2g}^{\epsilon }(\mathbb {Z})$

which are ‘induced by the products’

$\bigsqcup _{g,\epsilon } B Sp_{2g}^{\epsilon }(\mathbb {Z})$

which are ‘induced by the products’

and

respectively. These structures contain the stabilization maps but also capture more information, which will be used to prove the above stability ranges and to properly define the class

![]() $\theta $

and the secondary stabilization.

$\theta $

and the secondary stabilization.

The main novelty of this paper is the way we deal with the Arf invariants

![]() $0$

and

$0$

and

![]() $1$

simultaneously using cellular

$1$

simultaneously using cellular

![]() $E_2$

-algebras. Some previous homological stability arguments study the ‘Arf invariant

$E_2$

-algebras. Some previous homological stability arguments study the ‘Arf invariant

![]() $0$

family’ and ‘Arf invariant

$0$

family’ and ‘Arf invariant

![]() $1$

family’ separately using the formalism of [Reference Randal-Williams and Wahl18], as, for example, in [Reference Friedrich3], but they require to prove that a certain simplicial complex is highly connected, and this is usually quite challenging. However, other previous results such as [Reference Harer8] or [Reference Randal-Williams17], are based on the idea of using a different simplicial complex whose connectivity is easier to prove, at the expense of complicating some spectral sequence arguments. The main insight of this paper is to apply the previous philosophy in the land of cellular

$1$

family’ separately using the formalism of [Reference Randal-Williams and Wahl18], as, for example, in [Reference Friedrich3], but they require to prove that a certain simplicial complex is highly connected, and this is usually quite challenging. However, other previous results such as [Reference Harer8] or [Reference Randal-Williams17], are based on the idea of using a different simplicial complex whose connectivity is easier to prove, at the expense of complicating some spectral sequence arguments. The main insight of this paper is to apply the previous philosophy in the land of cellular

![]() $E_2$

-algebras, which means that we prefer to have a more complicated

$E_2$

-algebras, which means that we prefer to have a more complicated

![]() $E_2$

-algebra if we get a simpler connectivity estimate. As we will see in Section 5.1, combining both families into one single

$E_2$

-algebra if we get a simpler connectivity estimate. As we will see in Section 5.1, combining both families into one single

![]() $E_2$

-algebra leads to much easier connectivity arguments, at the (small) price of having more technical cellular

$E_2$

-algebra leads to much easier connectivity arguments, at the (small) price of having more technical cellular

![]() $E_2$

-algebras that one needs to study. However, as we will see in Sections 3 and 4 one can deal with these extra difficulties by carefully analyzing some spectral sequences. This new point of view has many potential applications, such as in [Reference Sierra19] to study improved homological stability of diffeomorphisms of certain manifolds.

$E_2$

-algebras that one needs to study. However, as we will see in Sections 3 and 4 one can deal with these extra difficulties by carefully analyzing some spectral sequences. This new point of view has many potential applications, such as in [Reference Sierra19] to study improved homological stability of diffeomorphisms of certain manifolds.

1.3 Organization of the paper

Section 2 presents an overview of the machinery of Cellular

![]() $E_k$

-algebras developed in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5], which will play a central role in this paper. In Section 3 we will state generic stability results for

$E_k$

-algebras developed in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5], which will play a central role in this paper. In Section 3 we will state generic stability results for

![]() $E_2$

-algebras, which will be proven in Section 4 and then used to show our main results, Theorems A and B.

$E_2$

-algebras, which will be proven in Section 4 and then used to show our main results, Theorems A and B.

In Section 5 we will define the notion of ‘quadratic datum” and explain how it produces a ‘quadratic

![]() $E_2$

-algebra’. This construction generalizes the way that spin mapping class groups and quadratic symplectic groups are defined from the mapping class groups and symplectic groups respectively. One of the main insights of this paper is contained in Theorem 5.4 and Corollary 5.5, which give ways to access information about the

$E_2$

-algebra’. This construction generalizes the way that spin mapping class groups and quadratic symplectic groups are defined from the mapping class groups and symplectic groups respectively. One of the main insights of this paper is contained in Theorem 5.4 and Corollary 5.5, which give ways to access information about the

![]() $E_2$

-cells of the quadratic

$E_2$

-cells of the quadratic

![]() $E_2$

-algebra from knowledge about the underlying nonquadratic algebra. In particular, this will give us a way to directly use previous results in the literature to deduce all our connectivity estimates.

$E_2$

-algebra from knowledge about the underlying nonquadratic algebra. In particular, this will give us a way to directly use previous results in the literature to deduce all our connectivity estimates.

Section 6 is devoted to the proof of Theorem B, which is an application of the results of the previous sections. In the proof of the last two parts of the theorem we will also need some information about the first homology groups of quadratic symplectic groups, which can be found in Section 8.

Section 7 contains the proof of Theorem A, which follows similar steps to the previous section.

Finally, Section 8 contains detailed computations of the first homology groups of spin mapping class groups and quadratic symplectic groups. Let us remark that a full description of all first homology groups and stabilization maps is included for completeness, even if not everything there is used to prove Theorems A and B. The main idea behind the computations is to start with known presentations of the mapping class groups and symplectic groups and then to find presentations for the (finite index subgroups) spin mapping class groups and quadratic symplectic groups using GAP, [7]. This is shown to be a quite effective method for computing first homology and homology operations of families of groups when one has some available presentations.

2 Overview of cellular

$E_2$

-algebras

$E_2$

-algebras

The purpose of this section is to explain the methods from [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5] used in this paper: we aim for an informal discussion and refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5] for details.

2.1 Cellular

$E_2$

-algebras and their indecomposables

$E_2$

-algebras and their indecomposables

In the parts of this paper relying on cellular

![]() $E_2$

-algebras, mainly Sections 3 and 4, we will work in the underlying category

$E_2$

-algebras, mainly Sections 3 and 4, we will work in the underlying category ![]() of

of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial

$\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial ![]() -modules, for

-modules, for ![]() a commutative ring and

a commutative ring and

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

a discrete symmetric monoid (i.e., abelian monoid). Formally,

$\mathsf {G}$

a discrete symmetric monoid (i.e., abelian monoid). Formally, ![]() denotes the category of functors from

denotes the category of functors from

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

, viewed as a category with objects the elements of

$\mathsf {G}$

, viewed as a category with objects the elements of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

and only identity morphisms, to

$\mathsf {G}$

and only identity morphisms, to ![]() . This means that each object M consists of a simplicial

. This means that each object M consists of a simplicial ![]() -module

-module

![]() $M_{\bullet }(x)$

for each

$M_{\bullet }(x)$

for each

![]() $x \in \mathsf {G}$

. There is a symmetric monoidal structure

$x \in \mathsf {G}$

. There is a symmetric monoidal structure

![]() $\otimes $

in this category given by Day convolution applied to the usual tensor product of simplicial modules, that is,

$\otimes $

in this category given by Day convolution applied to the usual tensor product of simplicial modules, that is,

where

![]() $\oplus $

denotes the symmetric monoidal structure of

$\oplus $

denotes the symmetric monoidal structure of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

. In a similar way one can define the category of

$\mathsf {G}$

. In a similar way one can define the category of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

-graded spaces, denoted by

$\mathsf {G}$

-graded spaces, denoted by

![]() $\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}}$

and endow it with a symmetric monoidal structure by Day convolution using the cartesian product of spaces in place of the tensor product of simplicial

$\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}}$

and endow it with a symmetric monoidal structure by Day convolution using the cartesian product of spaces in place of the tensor product of simplicial ![]() -modules.

-modules.

The reason why these two underlying categories will be the relevant ones for us is the following: In this paper we will study homological properties of certain

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in

$E_2$

-algebras in

![]() ${\mathsf {Top}}^{\mathsf {G}}$

, but the category of

${\mathsf {Top}}^{\mathsf {G}}$

, but the category of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in

$E_2$

-algebras in

![]() ${\mathsf {Top}}^{\mathsf {G}}$

is not well-behaved for some of the proofs of sections 3, 4. As we will explain below, we will fix this issue by using the lax symmetric monoidal functor

${\mathsf {Top}}^{\mathsf {G}}$

is not well-behaved for some of the proofs of sections 3, 4. As we will explain below, we will fix this issue by using the lax symmetric monoidal functor

given by the free ![]() -module on the singular simplicial set of a space, and then make all the proofs in

-module on the singular simplicial set of a space, and then make all the proofs in

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial modules instead, following [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6].

$\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial modules instead, following [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6].

Let us now define precisely what we will mean by

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in the above underlying categories: the little 2-cubes operad in

$E_2$

-algebras in the above underlying categories: the little 2-cubes operad in

![]() $\mathsf {Top}$

has n-ary operations given by rectilinear embeddings

$\mathsf {Top}$

has n-ary operations given by rectilinear embeddings

![]() $I^2 \times \{1,\cdots ,n\} \hookrightarrow I^2$

such that the interiors of the images of the

$I^2 \times \{1,\cdots ,n\} \hookrightarrow I^2$

such that the interiors of the images of the

![]() $2$

-cubes are disjoint, and operadic composition induced by composition of embeddings. (The space of 0-ary operations is empty.) We define the little

$2$

-cubes are disjoint, and operadic composition induced by composition of embeddings. (The space of 0-ary operations is empty.) We define the little

![]() $2$

-cubes operad in

$2$

-cubes operad in ![]() by applying the lax symmetric monoidal functor

by applying the lax symmetric monoidal functor ![]() described above. Similarly,

described above. Similarly, ![]() can be promoted to a lax symmetric monoidal functor

can be promoted to a lax symmetric monoidal functor ![]() between the graded categories, and we define the little

between the graded categories, and we define the little

![]() $2$

-cubes operad in these by concentrating it in grading

$2$

-cubes operad in these by concentrating it in grading

![]() $0$

, where

$0$

, where

![]() $0 \in \mathsf {G}$

denotes the identity of the monoid. We shall denote this operad by

$0 \in \mathsf {G}$

denotes the identity of the monoid. We shall denote this operad by

![]() $\mathcal {C}_2$

in all the categories

$\mathcal {C}_2$

in all the categories ![]() which we use, and define a (nonunital)

which we use, and define a (nonunital)

![]() $E_2$

-algebra to mean an algebra over this operad. (The precise statement here is that we use

$E_2$

-algebra to mean an algebra over this operad. (The precise statement here is that we use

![]() $\mathcal {C}_2$

as our fixed model for the

$\mathcal {C}_2$

as our fixed model for the

![]() $E_2$

-operad.) We will use the notation

$E_2$

-operad.) We will use the notation

![]() $\operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {C})$

to denote the category of (nonunital)

$\operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {C})$

to denote the category of (nonunital)

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in

$E_2$

-algebras in

![]() $\mathsf {C}$

, where

$\mathsf {C}$

, where

![]() $\mathsf {C}$

is any of the categories that we use.

$\mathsf {C}$

is any of the categories that we use.

The

![]() $E_2$

-indecomposables

$E_2$

-indecomposables

![]() $Q^{E_2}(\textbf {R})$

of an

$Q^{E_2}(\textbf {R})$

of an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra

$E_2$

-algebra

![]() $\textbf {R}$

in

$\textbf {R}$

in ![]() are defined by the exact sequence of

are defined by the exact sequence of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial

$\mathsf {G}$

-graded simplicial ![]() -modules

-modules

where we will usually suppress the forgetful functor ![]() unless there is a risk of confusion.

unless there is a risk of confusion.

The functor ![]() does not preserve weak equivalences (see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5] for details on the model structures used) but has a derived functor

does not preserve weak equivalences (see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5] for details on the model structures used) but has a derived functor

![]() $Q_{\mathbb {L}}^{E_2}(-)$

which does. See [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 8.2.3, Section 13] for details and how to define it in more general categories such as

$Q_{\mathbb {L}}^{E_2}(-)$

which does. See [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 8.2.3, Section 13] for details and how to define it in more general categories such as

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in

$E_2$

-algebras in

![]() $\mathsf {Top}$

or

$\mathsf {Top}$

or

![]() $\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}}$

. The

$\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}}$

. The

![]() $E_2$

-homology groups of

$E_2$

-homology groups of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

are defined to be

$\textbf {R}$

are defined to be

for

![]() $x \in \mathsf {G}$

and

$x \in \mathsf {G}$

and

![]() $d \in \mathbb {N}$

. One formal property of the derived indecomposables, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Lemma 18.2], is that it commutes with

$d \in \mathbb {N}$

. One formal property of the derived indecomposables, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Lemma 18.2], is that it commutes with ![]() , so for

, so for

![]() $\textbf {R} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}})$

its

$\textbf {R} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {Top}^{\mathsf {G}})$

its

![]() $E_2$

-homology with

$E_2$

-homology with ![]() coefficients is the same as the

coefficients is the same as the

![]() $E_2$

-homology of

$E_2$

-homology of ![]() . Also, by definition, the homology of

. Also, by definition, the homology of

![]() $\mathbf {R}$

with

$\mathbf {R}$

with ![]() -coefficients is precisely the homology of

-coefficients is precisely the homology of ![]() .

.

Thus, in order to study homological properties of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

with different coefficients we can work with the

$\textbf {R}$

with different coefficients we can work with the

![]() $E_2$

-algebras

$E_2$

-algebras ![]() instead, which enjoy better properties as they are cofibrant and the category of graded simplicial

instead, which enjoy better properties as they are cofibrant and the category of graded simplicial ![]() -modules offers some technical advantages as explained in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 11]. However, at the same time, we can do computations in

-modules offers some technical advantages as explained in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 11]. However, at the same time, we can do computations in

![]() $\mathsf {Top}$

of the homology or

$\mathsf {Top}$

of the homology or

![]() $E_2$

-homology of

$E_2$

-homology of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

and then transfer them to

$\textbf {R}$

and then transfer them to ![]() .

.

2.2 CW

$E_2$

-algebras

$E_2$

-algebras

In this section we will give an overview of the notions of cell attachments in

![]() $E_2$

-algebras and of CW

$E_2$

-algebras and of CW

![]() $E_2$

-algebras, and refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6] for all the details and proofs.

$E_2$

-algebras, and refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6] for all the details and proofs.

Let us begin by introducing some useful notation. Let

![]() $\Delta ^{x,d} \in \mathsf {sSet}^{\mathsf {G}}$

be the standard d-simplex placed in grading x and let

$\Delta ^{x,d} \in \mathsf {sSet}^{\mathsf {G}}$

be the standard d-simplex placed in grading x and let

![]() $\partial \Delta ^{x,d} \in \mathsf {sSet}^{\mathsf {G}}$

be its boundary. By applying the free

$\partial \Delta ^{x,d} \in \mathsf {sSet}^{\mathsf {G}}$

be its boundary. By applying the free ![]() -module functor we get objects

-module functor we get objects ![]() .

.

In ![]() , the data for a cell attachment to an

, the data for a cell attachment to an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra

$E_2$

-algebra

![]() $\textbf {R}$

is an attaching map

$\textbf {R}$

is an attaching map ![]() in

in ![]() , which is the same as a map

, which is the same as a map ![]() of simplicial

of simplicial ![]() -modules. To attach the cell we form the pushout in

-modules. To attach the cell we form the pushout in ![]()

where

![]() $\mathbf {E_2}(-)$

denotes the free

$\mathbf {E_2}(-)$

denotes the free

![]() $E_2$

-algebra functor. Informally, this is attaching a usual cell along e together with the result of formally applying

$E_2$

-algebra functor. Informally, this is attaching a usual cell along e together with the result of formally applying

![]() $E_2$

-operations to elements of

$E_2$

-operations to elements of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

and the new cell.

$\textbf {R}$

and the new cell.

Before moving on let us make a technical remark about cell attachments that will be used repeatedly without mention in Sections 1.2 and 4.

Remark 2.1. To attach an

![]() $(x,d)$

-cell we need an attaching map

$(x,d)$

-cell we need an attaching map ![]() in

in ![]() , but in this paper we will normally want to attach cells along maps

, but in this paper we will normally want to attach cells along maps ![]() instead, where the

instead, where the

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

-graded spheres in

$\mathsf {G}$

-graded spheres in ![]() are defined via

are defined via ![]() , where the quotient denotes the cofibre of the inclusion of the boundary into the simplex.

, where the quotient denotes the cofibre of the inclusion of the boundary into the simplex.

The precise construction is as follows: there is a canonical map ![]() which extends to the graded categories, hence allowing to make sense of cell attachments along maps defined on spheres.

which extends to the graded categories, hence allowing to make sense of cell attachments along maps defined on spheres.

We will (informally) define a CW

![]() $E_2$

-algebra to be an

$E_2$

-algebra to be an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra built by successive cell attachments in increasing order of dimension, and we refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Definitions 6.12, 6.13] for all the technical details. One important property we will need in this paper is the fact that any

$E_2$

-algebra built by successive cell attachments in increasing order of dimension, and we refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Definitions 6.12, 6.13] for all the technical details. One important property we will need in this paper is the fact that any

![]() $E_2$

-algebra built by starting with a free

$E_2$

-algebra built by starting with a free

![]() $E_2$

-algebra on some wedge of spheres and then attaching

$E_2$

-algebra on some wedge of spheres and then attaching

![]() $E_2$

-cells of higher dimension is a CW algebra, which follows from the precise definitions in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6].

$E_2$

-cells of higher dimension is a CW algebra, which follows from the precise definitions in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6].

Since the functor

![]() $Q_{\mathbb {L}}^{E_2}(-)$

is a (derived) left adjoint, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 3], then it sends CW

$Q_{\mathbb {L}}^{E_2}(-)$

is a (derived) left adjoint, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 3], then it sends CW

![]() $E_2$

-algebras to

$E_2$

-algebras to

![]() $CW$

-objects in the underlying category (since CW algebras are cofibrant), in a way that it can be explicitly evaluated, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.1.3] for details. The effect of these

$CW$

-objects in the underlying category (since CW algebras are cofibrant), in a way that it can be explicitly evaluated, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.1.3] for details. The effect of these

![]() $E_2$

-cell attachments in homology is harder to compute, but one can do so by using the ‘cell attachment filtration’ of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.2.1], which informally speaking ‘puts

$E_2$

-cell attachments in homology is harder to compute, but one can do so by using the ‘cell attachment filtration’ of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.2.1], which informally speaking ‘puts

![]() $\mathbf {R}$

in filtration

$\mathbf {R}$

in filtration

![]() $0$

and the new cell we attach in filtration

$0$

and the new cell we attach in filtration

![]() $1$

’. Informally, higher filtration steps are produced by applying

$1$

’. Informally, higher filtration steps are produced by applying

![]() $E_2$

-operations to lower steps: for example, a product of k copies of the new cell will have filtration k. We will make repeated use of this filtration and the corresponding spectral sequence in Section 4 to compute the effect of

$E_2$

-operations to lower steps: for example, a product of k copies of the new cell will have filtration k. We will make repeated use of this filtration and the corresponding spectral sequence in Section 4 to compute the effect of

![]() $E_2$

-cell attachments in homology.

$E_2$

-cell attachments in homology.

A weak equivalence

![]() $\textbf {C} \xrightarrow {\sim } \textbf {R}$

from a CW

$\textbf {C} \xrightarrow {\sim } \textbf {R}$

from a CW

![]() $E_2$

-algebra is called a CW-approximation to

$E_2$

-algebra is called a CW-approximation to

![]() $\textbf {R}$

, and a key result, [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 11.21], is that if

$\textbf {R}$

, and a key result, [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 11.21], is that if

![]() $\textbf {R}(0) \simeq 0$

then

$\textbf {R}(0) \simeq 0$

then

![]() $\textbf {R}$

admits a CW-approximation provided that the grading monoid and the underlying category satisfy some technical assumptions. (These extra assumptions will be automatic for

$\textbf {R}$

admits a CW-approximation provided that the grading monoid and the underlying category satisfy some technical assumptions. (These extra assumptions will be automatic for ![]() and the monoids considered in this paper.) Moreover, whenever

and the monoids considered in this paper.) Moreover, whenever ![]() is a field, we can construct a CW-approximation in which the number of

is a field, we can construct a CW-approximation in which the number of

![]() $(x,d)$

-cells needed is precisely the dimension of

$(x,d)$

-cells needed is precisely the dimension of

![]() $H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {R})$

. By “giving the d-cells filtration d”, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6] for a more precise discussion of what this means, one gets a skeletal filtration of this

$H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {R})$

. By “giving the d-cells filtration d”, see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6] for a more precise discussion of what this means, one gets a skeletal filtration of this

![]() $E_2$

-algebra and a spectral sequence computing the homology of

$E_2$

-algebra and a spectral sequence computing the homology of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

.

$\textbf {R}$

.

We have mentioned in this section that cell attachments and CW algebras give ‘filtrations of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras’. Let us remark that following [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 5], a ‘filtered

$E_2$

-algebras’. Let us remark that following [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 5], a ‘filtered

![]() $E_2$

-algebra’ will always mean in this paper an

$E_2$

-algebra’ will always mean in this paper an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra in the associated category of filtered objects, which is the category of functors from

$E_2$

-algebra in the associated category of filtered objects, which is the category of functors from

![]() $\mathbb {Z}_\le $

(viewed as a poset) to the underlying category. For us, the underlying category will always be

$\mathbb {Z}_\le $

(viewed as a poset) to the underlying category. For us, the underlying category will always be ![]() so the category of filtered objects is denoted

so the category of filtered objects is denoted ![]() , and hence filtered

, and hence filtered

![]() $E_2$

-algebras will mean objects in

$E_2$

-algebras will mean objects in

![]() $ \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}((\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {G}})^{\mathbb {Z}_{\leq }})$

. While we refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 5] for all the technical details in filtrations of

$ \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}((\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {G}})^{\mathbb {Z}_{\leq }})$

. While we refer to [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 5] for all the technical details in filtrations of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras let us mention that the definition is so that the associated graded is naturally an

$E_2$

-algebras let us mention that the definition is so that the associated graded is naturally an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra and one gets a spectral sequence of

$E_2$

-algebra and one gets a spectral sequence of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras converging to the homology of the colimit, which is thought as the

$E_2$

-algebras converging to the homology of the colimit, which is thought as the

![]() $E_2$

-algebra that we are filtering. We will see working examples of filtrations and the corresponding spectral sequences in Section 4.

$E_2$

-algebra that we are filtering. We will see working examples of filtrations and the corresponding spectral sequences in Section 4.

2.3 Homological stability for

$E_2$

-algebras

$E_2$

-algebras

In order to discuss homological stability of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras we will need some preparation. For the rest of this section let

$E_2$

-algebras we will need some preparation. For the rest of this section let ![]() , where

, where

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

is equipped with a symmetric monoidal functor

$\mathsf {G}$

is equipped with a symmetric monoidal functor

![]() $\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {G} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

, where

$\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {G} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

, where

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

is viewed as a discrete abelian monoid under addition. More concretely, this amounts to a function from the objects of

$\mathbb {N}$

is viewed as a discrete abelian monoid under addition. More concretely, this amounts to a function from the objects of

![]() $\mathsf {G}$

to

$\mathsf {G}$

to

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

such that

$\mathbb {N}$

such that

![]() $\operatorname {rk}(g_1\oplus g_2)=\operatorname {rk}(g_1)+\operatorname {rk}(g_2)$

. Suppose in addition that we are given a homology class

$\operatorname {rk}(g_1\oplus g_2)=\operatorname {rk}(g_1)+\operatorname {rk}(g_2)$

. Suppose in addition that we are given a homology class

![]() $\sigma \in H_{x,0}(\textbf {R})$

with

$\sigma \in H_{x,0}(\textbf {R})$

with

![]() $\operatorname {rk}(x)=1$

. By definition

$\operatorname {rk}(x)=1$

. By definition

![]() $\sigma $

is a homotopy class of maps

$\sigma $

is a homotopy class of maps ![]() .

.

Following [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2], there is a strictly associative algebra

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

which is equivalent to the unitalization

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

which is equivalent to the unitalization ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the monoidal unit in simplicial modules. The introduction of

is the monoidal unit in simplicial modules. The introduction of

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

at this point is to have a unit available and to have strict associativity to make some technical constructions as explained in the previous reference. Then,

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

at this point is to have a unit available and to have strict associativity to make some technical constructions as explained in the previous reference. Then,

![]() $\sigma $

gives a map

$\sigma $

gives a map ![]() by using the associative product of

by using the associative product of

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

. We then define

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

. We then define

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

to be the cofibre of this map. Observe that a priori

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

to be the cofibre of this map. Observe that a priori

![]() $\sigma \cdot -$

is not a (left)

$\sigma \cdot -$

is not a (left)

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module map, so the cofibre

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module map, so the cofibre

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

is not a (left)

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

is not a (left)

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module. However, by the ‘adapters construction’ in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2] and its applications in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2.3], there is a way of lifting the cofibration sequence

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module. However, by the ‘adapters construction’ in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2] and its applications in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2.3], there is a way of lifting the cofibration sequence

![]() $S^{x,0} \otimes \mathbf {\overline {R}} \xrightarrow {\sigma \cdot - } \mathbf {\overline {R}} \rightarrow \mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

to the category

$S^{x,0} \otimes \mathbf {\overline {R}} \xrightarrow {\sigma \cdot - } \mathbf {\overline {R}} \rightarrow \mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

to the category ![]() in such a way that forgetting the left

in such a way that forgetting the left

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module structure recovers the previous construction; we will make use of this fact in some of the proofs of Section 4.

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}$

-module structure recovers the previous construction; we will make use of this fact in some of the proofs of Section 4.

By construction

![]() $\sigma \cdot -$

induces maps

$\sigma \cdot -$

induces maps

![]() $\textbf {R}(y) \rightarrow \textbf {R}(x+y)$

between the different graded components of

$\textbf {R}(y) \rightarrow \textbf {R}(x+y)$

between the different graded components of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

and the homology of the object

$\textbf {R}$

and the homology of the object

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

captures the relative homology of these due to the long exact sequence

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

captures the relative homology of these due to the long exact sequence

Thus, homological stability results of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

using

$\textbf {R}$

using

![]() $\sigma $

to stabilize can be reformulated as vanishing ranges for

$\sigma $

to stabilize can be reformulated as vanishing ranges for

![]() $H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma )$

; the advantage of doing so is that using filtrations for CW approximations of

$H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma )$

; the advantage of doing so is that using filtrations for CW approximations of

![]() $\textbf {R}$

one also gets filtrations of

$\textbf {R}$

one also gets filtrations of

![]() $\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

and hence spectral sequences capable of detecting vanishing ranges.

$\mathbf {\overline {R}}/\sigma $

and hence spectral sequences capable of detecting vanishing ranges.

The secondary stability result can be written in terms of

![]() $E_2$

-algebras in a similar way: this time we will have a class

$E_2$

-algebras in a similar way: this time we will have a class

![]() $\sigma $

as above and another class

$\sigma $

as above and another class

![]() $\theta $

, and we will prove a vanishing in the homology of the iterated cofibre construction

$\theta $

, and we will prove a vanishing in the homology of the iterated cofibre construction

![]() $\mathbf {R}/(\sigma ,\theta ):=(\mathbf {R}/\sigma )/\theta $

, in the sense of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2.3].

$\mathbf {R}/(\sigma ,\theta ):=(\mathbf {R}/\sigma )/\theta $

, in the sense of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 12.2.3].

3 Generic homological stability results

In this section we will state three homological stability results for

![]() $E_2$

-algebras, Theorems 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3, that will later apply to quadratic symplectic groups and spin mapping class groups in Sections 6 and 7. The first two of these are inspired by the generic homological stability theorem [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 18.3], in the sense that they input a vanishing line on the

$E_2$

-algebras, Theorems 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3, that will later apply to quadratic symplectic groups and spin mapping class groups in Sections 6 and 7. The first two of these are inspired by the generic homological stability theorem [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 18.3], in the sense that they input a vanishing line on the

![]() $E_2$

-homology of an

$E_2$

-homology of an

![]() $E_2$

-algebra along with some information about the homology in small bidegrees, and they output homological stability results for the algebra. More precisely, Theorem 3.1 is the direct generalization of the generic homological stability theorem [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 18.3] to the context where the grading is a certain monoid

$E_2$

-algebra along with some information about the homology in small bidegrees, and they output homological stability results for the algebra. More precisely, Theorem 3.1 is the direct generalization of the generic homological stability theorem [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 18.3] to the context where the grading is a certain monoid

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

introduced below instead of the usual

$\mathsf {H}$

introduced below instead of the usual

![]() $\mathbb {N}$

. While the result of stability itself is to be expected, the fact that one also gets a

$\mathbb {N}$

. While the result of stability itself is to be expected, the fact that one also gets a

![]() $1/2$

-slope result is surprising. Moreover, the change of monoid will require us to study the homological stability of a certain nonfree

$1/2$

-slope result is surprising. Moreover, the change of monoid will require us to study the homological stability of a certain nonfree

![]() $E_2$

-algebra

$E_2$

-algebra

![]() $\mathbf {A}$

by directly computing its homology from its

$\mathbf {A}$

by directly computing its homology from its

![]() $E_2$

-cell structure. Secondly, Theorem 3.2 improves the stability bound under more technical assumptions about the homology in small bidegrees, and while the main idea of the proof is unchanged, the technical work to improve the bound is significantly harder.

$E_2$

-cell structure. Secondly, Theorem 3.2 improves the stability bound under more technical assumptions about the homology in small bidegrees, and while the main idea of the proof is unchanged, the technical work to improve the bound is significantly harder.

The third result is a secondary stability result, inspired by [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6, Lemma 5.6, Theorem 5.12]. The main novelty here is the construction of the relevant secondary-stability class

![]() $\theta $

, which arises from a spectral sequence computation analyzing the

$\theta $

, which arises from a spectral sequence computation analyzing the

![]() $\mathbb {F}_2$

-homology of the nonfree

$\mathbb {F}_2$

-homology of the nonfree

![]() $E_2$

-algebra

$E_2$

-algebra

![]() $\mathbf {A}$

. In order to prove the secondary stability result itself, we will also need to check that the class

$\mathbf {A}$

. In order to prove the secondary stability result itself, we will also need to check that the class

![]() $\theta $

lifts to a ‘filtered class’.

$\theta $

lifts to a ‘filtered class’.

In addition, we have Corollary 4.4, which says that

![]() $E_2$

-algebras satisfying the assumptions of Theorem 3.3 have homological stability of slope either exactly

$E_2$

-algebras satisfying the assumptions of Theorem 3.3 have homological stability of slope either exactly

![]() $1/2$

or at least

$1/2$

or at least

![]() $2/3$

depending on the value of a certain homology class. However, the precise statement of this corollary is delayed to the next section until we have properly defined the secondary stabilization map.

$2/3$

depending on the value of a certain homology class. However, the precise statement of this corollary is delayed to the next section until we have properly defined the secondary stabilization map.

Before stating the results let us define the grading category that will be relevant: from now on let

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

be the discrete monoid

$\mathsf {H}$

be the discrete monoid

![]() $\{0\} \cup (\mathbb {N}_{>0} \times \mathbb {Z}/2)$

, where the monoidal structure

$\{0\} \cup (\mathbb {N}_{>0} \times \mathbb {Z}/2)$

, where the monoidal structure

![]() $+$

is given by addition in both coordinates. We denote by

$+$

is given by addition in both coordinates. We denote by

![]() $\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {H} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

the monoidal functor given by projection to the first coordinate. (The reason why we take

$\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {H} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

the monoidal functor given by projection to the first coordinate. (The reason why we take

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

instead of

$\mathsf {H}$

instead of

![]() $\mathbb {N} \times \mathbb {Z}/2$

is because as we will see in Lemma 6.2,

$\mathbb {N} \times \mathbb {Z}/2$

is because as we will see in Lemma 6.2,

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

is chosen to agree with the monoid of path-components of the

$\mathsf {H}$

is chosen to agree with the monoid of path-components of the

![]() $E_2$

-algebras of quadratic symplectic groups and spin mapping class groups.) Left Kan extension along the canonical rank functor

$E_2$

-algebras of quadratic symplectic groups and spin mapping class groups.) Left Kan extension along the canonical rank functor

![]() $\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {H} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

defines a map

$\operatorname {rk}: \mathsf {H} \rightarrow \mathbb {N}$

defines a map ![]() , which on underlying objects is given by

, which on underlying objects is given by

![]() $\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})(n)= \mathbf {R}((n,0)) \oplus \mathbf {R}((n,1))$

for

$\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})(n)= \mathbf {R}((n,0)) \oplus \mathbf {R}((n,1))$

for

![]() $n \ge 1$

and

$n \ge 1$

and

![]() $\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})(0)=\mathbf {R}(0)$

. We will normally abuse notation in this paper and denote

$\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})(0)=\mathbf {R}(0)$

. We will normally abuse notation in this paper and denote

![]() $\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})$

by

$\operatorname {rk}_*(\mathbf {R})$

by

![]() $\mathbf {R}$

too, but where we give its components a different grading.

$\mathbf {R}$

too, but where we give its components a different grading.

Also, let us recall that on ![]() there is a homology operation

there is a homology operation ![]() defined in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Page 200]. This operation satisfies that

defined in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Page 200]. This operation satisfies that ![]() , where

, where

![]() $[-,-]$

is the Browder bracket; and is constructed by base-change

$[-,-]$

is the Browder bracket; and is constructed by base-change ![]() from the case

from the case ![]() , where

, where

![]() $Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(-)$

is defined by constructing it in the universal example

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(-)$

is defined by constructing it in the universal example

![]() $\mathbf {R}=\mathbf {E_2}(S_{\mathbb {Z}}^{x,0}) \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathbb {N}})$

for

$\mathbf {R}=\mathbf {E_2}(S_{\mathbb {Z}}^{x,0}) \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathbb {N}})$

for

![]() $x \in \mathbb {N}$

. If one starts instead with the universal example

$x \in \mathbb {N}$

. If one starts instead with the universal example

![]() $\mathbf {R}=\mathbf {E_2}(S_{\mathbb {Z}}^{x,0}) \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {H}})$

for

$\mathbf {R}=\mathbf {E_2}(S_{\mathbb {Z}}^{x,0}) \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {H}})$

for

![]() $x \in \mathsf {H}$

then the exact same proof yields a homology operation

$x \in \mathsf {H}$

then the exact same proof yields a homology operation ![]() in

in ![]() such that

such that ![]() , and which is compatible with

, and which is compatible with

![]() $\operatorname {rk}_*$

in the obvious way. We will make extensive use of this operation in the rest of this and the next sections.

$\operatorname {rk}_*$

in the obvious way. We will make extensive use of this operation in the rest of this and the next sections.

Theorem 3.1. Let ![]() be a commutative ring and let

be a commutative ring and let ![]() be such that

be such that

![]() $H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

$H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

![]() $H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\mathbf {X})=0$

for

$H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\mathbf {X})=0$

for

![]() $d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and

$d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and ![]() as a ring (where

as a ring (where

![]() $\overline {\mathbf {X}}$

denotes the unitalization of

$\overline {\mathbf {X}}$

denotes the unitalization of

![]() $\mathbf {X}$

), for some classes

$\mathbf {X}$

), for some classes

![]() $\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\mathbf {X})$

. Then, for any

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\mathbf {X})$

. Then, for any

![]() $\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

and any

$\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

and any

![]() $x \in \mathsf {H}$

we have

$x \in \mathsf {H}$

we have

![]() $H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/\sigma _{\epsilon })=0$

for

$H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/\sigma _{\epsilon })=0$

for

![]() $2d \leq \operatorname {rk}(x)-2$

.

$2d \leq \operatorname {rk}(x)-2$

.

Theorem 3.2. Let ![]() be a commutative

be a commutative

![]() $\mathbb {Z}[1/2]$

-algebra, let

$\mathbb {Z}[1/2]$

-algebra, let ![]() be such that

be such that

![]() $H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

$H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

![]() $H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {X})=0$

for

$H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {X})=0$

for

![]() $d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and

$d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and ![]() as a ring, for some classes

as a ring, for some classes

![]() $\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\textbf {X})$

. Suppose in addition that for some

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\textbf {X})$

. Suppose in addition that for some

![]() $\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we have:

$\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we have:

-

(i)

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot - : H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,1),1}(\textbf {X})$

is surjective.

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot - : H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,1),1}(\textbf {X})$

is surjective. -

(ii)

$\operatorname {coker}(\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot -: H_{(1,\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,0),1}(\textbf {X}))$

is generated by

$\operatorname {coker}(\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot -: H_{(1,\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,0),1}(\textbf {X}))$

is generated by  as a

as a

$\mathbb {Z}$

-module.

$\mathbb {Z}$

-module. -

(iii)

lies in the image of

lies in the image of

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

.

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

.

Then

![]() $H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/\sigma _{\epsilon })=0$

for

$H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/\sigma _{\epsilon })=0$

for

![]() $3d \leq 2 \operatorname {rk}(x)-4$

.

$3d \leq 2 \operatorname {rk}(x)-4$

.

Theorem 3.3. Let

![]() $\textbf {X} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {sMod}_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^{\mathsf {H}})$

be such that

$\textbf {X} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}(\mathsf {sMod}_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^{\mathsf {H}})$

be such that

![]() $H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

$H_{0,0}(\mathbf {X})=0$

,

![]() $H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {X})=0$

for

$H_{x,d}^{E_2}(\textbf {X})=0$

for

![]() $d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and

$d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

, and

![]() $H_{*,0}(\mathbf {\overline {X}})=\frac {\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}[\sigma _0,\sigma _1]}{(\sigma _1^2-\sigma _0^2)}$

as a ring, for some classes

$H_{*,0}(\mathbf {\overline {X}})=\frac {\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}[\sigma _0,\sigma _1]}{(\sigma _1^2-\sigma _0^2)}$

as a ring, for some classes

![]() $\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\textbf {X})$

. Suppose in addition that for some

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \in H_{(1,\epsilon ),0}(\textbf {X})$

. Suppose in addition that for some

![]() $\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we have:

$\epsilon \in \{0,1\}$

we have:

-

(i)

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot - : H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,1),1}(\textbf {X})$

is surjective.

$\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot - : H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,1),1}(\textbf {X})$

is surjective. -

(ii)

$\operatorname {coker}(\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot -: H_{(1,\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,0),1}(\textbf {X}))$

is generated by

$\operatorname {coker}(\sigma _{\epsilon } \cdot -: H_{(1,\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(2,0),1}(\textbf {X}))$

is generated by

$Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0)$

.

$Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0)$

. -

(iii)

$\sigma _{1-\epsilon } \cdot Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0) \in H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

lies in the image of

$\sigma _{1-\epsilon } \cdot Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0) \in H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

lies in the image of

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

.

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,1-\epsilon ),1}(\textbf {X})$

. -

(iv)

$\sigma _0 \cdot Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0) \in H_{(3,0),1}(\textbf {X})$

lies in the image of

$\sigma _0 \cdot Q_{\operatorname {\mathbb {F}_2}}^1(\sigma _0) \in H_{(3,0),1}(\textbf {X})$

lies in the image of

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,0),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,0),1}(\textbf {X})$

.

$\sigma _{\epsilon }^2 \cdot -:H_{(1,0),1}(\textbf {X}) \rightarrow H_{(3,0),1}(\textbf {X})$

.

Then there is a class

![]() $\theta \in H_{(4,0),2}(\mathbf {X})$

such that

$\theta \in H_{(4,0),2}(\mathbf {X})$

such that

![]() $H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/(\sigma _{\epsilon },\theta ))=0$

for

$H_{x,d}(\mathbf {\overline {X}}/(\sigma _{\epsilon },\theta ))=0$

for

![]() $3d \leq 2 \operatorname {rk}(x)-5$

.

$3d \leq 2 \operatorname {rk}(x)-5$

.

4 Proving Theorems 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3

In this section we will prove the previous results. These proofs are based on the ones of [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorem 18.3] and [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams6, Lemma 5.6, Theorem 5.12]. However, some new technical problems will arise from the fact that the ‘simple

![]() $E_2$

-algebra model’ that will be relevant to analyze

$E_2$

-algebra model’ that will be relevant to analyze

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

-graded

$\mathsf {H}$

-graded

![]() $E_2$

-algebras is not free. We will begin by now introducing this new

$E_2$

-algebras is not free. We will begin by now introducing this new

![]() $E_2$

-algebra, whose properties will play a very important role for the rest of this section.

$E_2$

-algebra, whose properties will play a very important role for the rest of this section.

For ![]() a commutative ring we define

a commutative ring we define

This should be thought of as a ‘universal example’ in a sense that will be clear in Sections 4.1 and 4.3.

Proposition 4.1. The

![]() $E_2$

-algebra

$E_2$

-algebra ![]() satisfies the assumptions of Theorem 3.1, that is,

satisfies the assumptions of Theorem 3.1, that is, ![]() ,

, ![]() for

for

![]() $d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

and

$d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

and ![]() as a ring.

as a ring.

Proof. Since ![]() is built using cells then its derived indecomposables can be explicitly evaluated as said in Section 2.2 (see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Sections 6.1.3 and 8.2] for details):

is built using cells then its derived indecomposables can be explicitly evaluated as said in Section 2.2 (see [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Sections 6.1.3 and 8.2] for details): ![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() for

for

![]() $d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

.

$d<\operatorname {rk}(x)-1$

.

For the homology computations it suffices to consider the case ![]() by the following argument:

by the following argument:

Let us write ![]() for the base-change functor and for the corresponding functor between

for the base-change functor and for the corresponding functor between

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

-graded categories. Base-change is symmetric monoidal, preserves colimits and satisfies

$\mathsf {H}$

-graded categories. Base-change is symmetric monoidal, preserves colimits and satisfies ![]() ,

, ![]() , and hence we recognize

, and hence we recognize ![]() since the attaching map of

since the attaching map of ![]() is obtained by base-change from the attaching map of

is obtained by base-change from the attaching map of

![]() $\operatorname {\mathbf {A_{\mathbb {Z}}}}$

. Thus, the universal coefficients theorem in homological degree

$\operatorname {\mathbf {A_{\mathbb {Z}}}}$

. Thus, the universal coefficients theorem in homological degree

![]() $0$

gives that

$0$

gives that ![]() , implying the claimed reduction.

, implying the claimed reduction.

To simplify notation we will not write

![]() $_{\mathbb {Z}}$

for the rest of this proof since we will only treat the case

$_{\mathbb {Z}}$

for the rest of this proof since we will only treat the case ![]() . Consider the cell-attachment filtration introduced in Section 2.2,

. Consider the cell-attachment filtration introduced in Section 2.2,

![]() $\mathbf {fA} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}((\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {H}})^{\mathbb {Z}_{\leq }})$

, which by [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.2.1] is given by

$\mathbf {fA} \in \operatorname {Alg}_{E_2}((\operatorname {\mathsf {sMod}}_{\mathbb {Z}}^{\mathsf {H}})^{\mathbb {Z}_{\leq }})$

, which by [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Section 6.2.1] is given by

where we will always use the convention that the last grading represents the filtration stage. For example,

![]() $\sigma _\epsilon $

has

$\sigma _\epsilon $

has

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

-grading

$\mathsf {H}$

-grading

![]() $(1,\epsilon ) \in \mathsf {H}$

, has homological degree

$(1,\epsilon ) \in \mathsf {H}$

, has homological degree

![]() $0$

and filtration degree

$0$

and filtration degree

![]() $0$

, and

$0$

, and

![]() $\rho $

has

$\rho $

has

![]() $\mathsf {H}$

-grading

$\mathsf {H}$

-grading

![]() $(2,0)$

, homological degree

$(2,0)$

, homological degree

![]() $1$

and is in filtration degree

$1$

and is in filtration degree

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

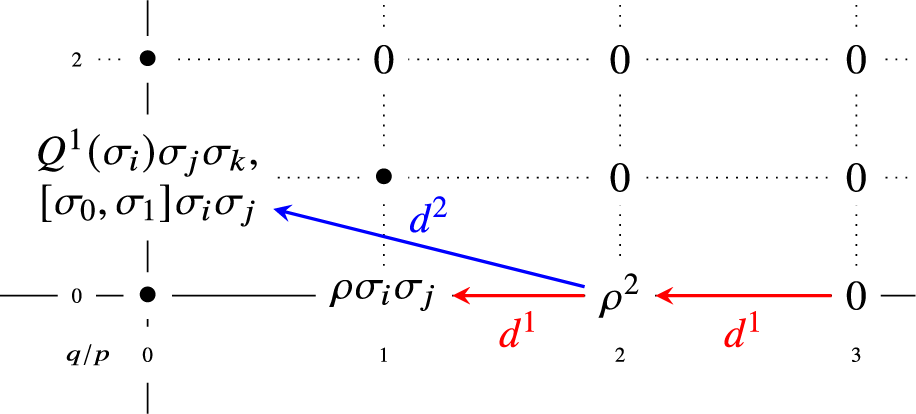

By [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Corollary 10.17] there is a spectral sequence

The first page of this spectral sequence can be accessed by [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Theorems 16.4, 16.7] and the description of the homology operation

![]() $Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(-)$

in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Page 200]. In homological degrees

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(-)$

in [Reference Galatius, Kupers and Randal-Williams5, Page 200]. In homological degrees

![]() $p+q \leq 1$

the full answer is given by

$p+q \leq 1$

the full answer is given by

-

•

$E^1_{x,p,-p}$

vanishes for

$E^1_{x,p,-p}$

vanishes for

$p \neq 0$

, and

$p \neq 0$

, and

$\bigoplus _{x \in \mathsf {H}}{E^1_{x,0,0}}$

is the free

$\bigoplus _{x \in \mathsf {H}}{E^1_{x,0,0}}$

is the free

$\mathbb {Z}$

-module on the set of generators

$\mathbb {Z}$

-module on the set of generators

$\{\sigma _0^a \cdot \sigma _1^b: \; a+b \geq 0\}$

, where

$\{\sigma _0^a \cdot \sigma _1^b: \; a+b \geq 0\}$

, where

$\sigma _0^0=\sigma _1^0=1$

.

$\sigma _0^0=\sigma _1^0=1$

. -

• The only elements in homological degree

$p+q=1$

are stabilizations by powers of

$p+q=1$

are stabilizations by powers of

$\sigma _0$

and

$\sigma _0$

and

$\sigma _1$

of one of the classes

$\sigma _1$

of one of the classes

$\rho $

,

$\rho $

,

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(\sigma _0)$

,

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(\sigma _0)$

,

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(\sigma _1)$

, or

$Q_{\mathbb {Z}}^1(\sigma _1)$

, or

$[\sigma _0,\sigma _1]$